Submitted:

12 April 2024

Posted:

12 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

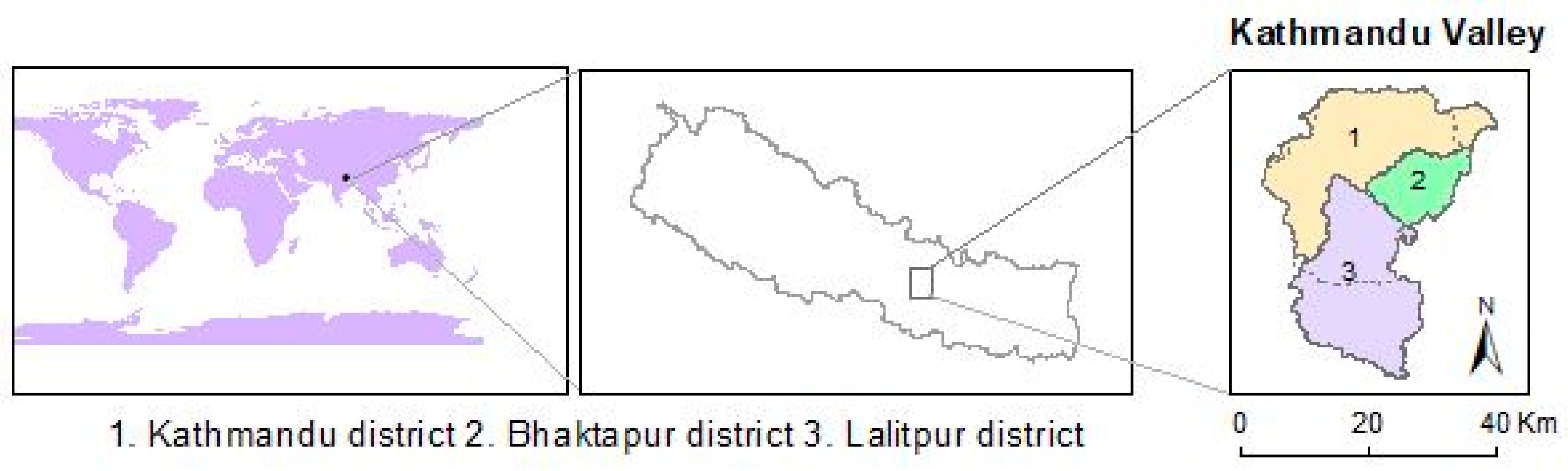

2.1. Nepalese Land Use Situation

2.2. Land Market - Land Use Relationship in Nepal

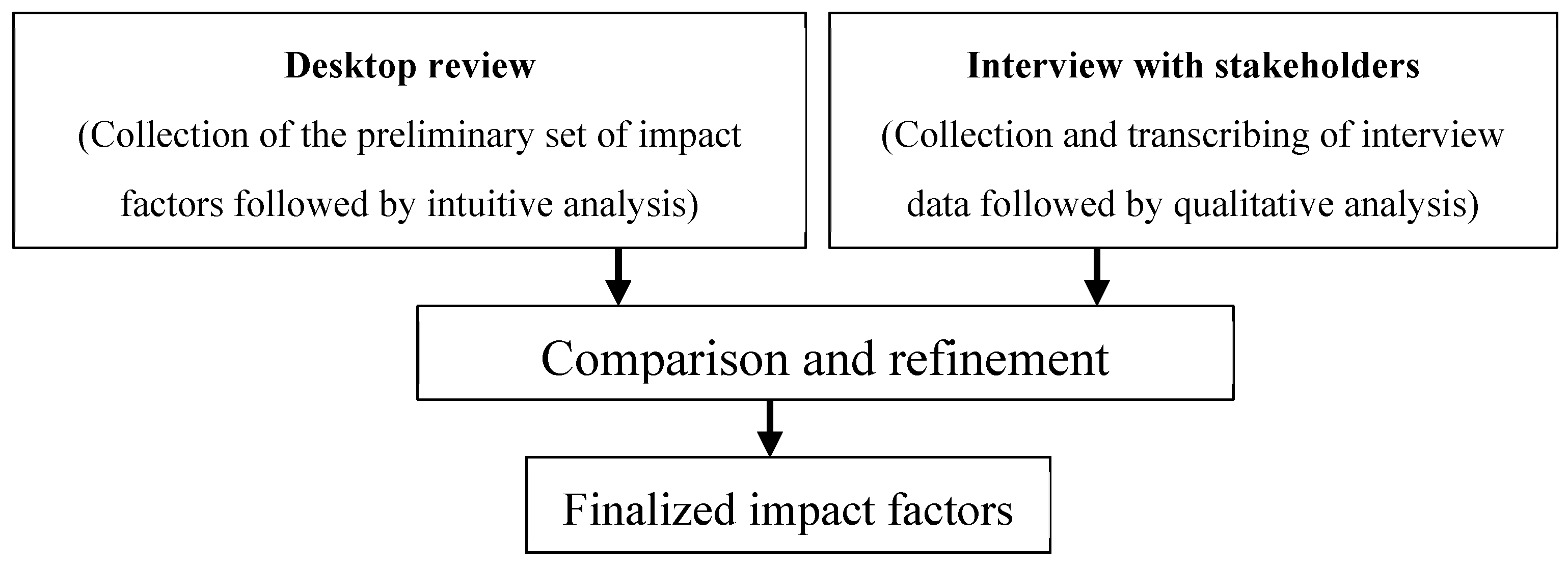

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Research Approach

3.2. Desktop review

3.3. Interview Data Collection in Nepal

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

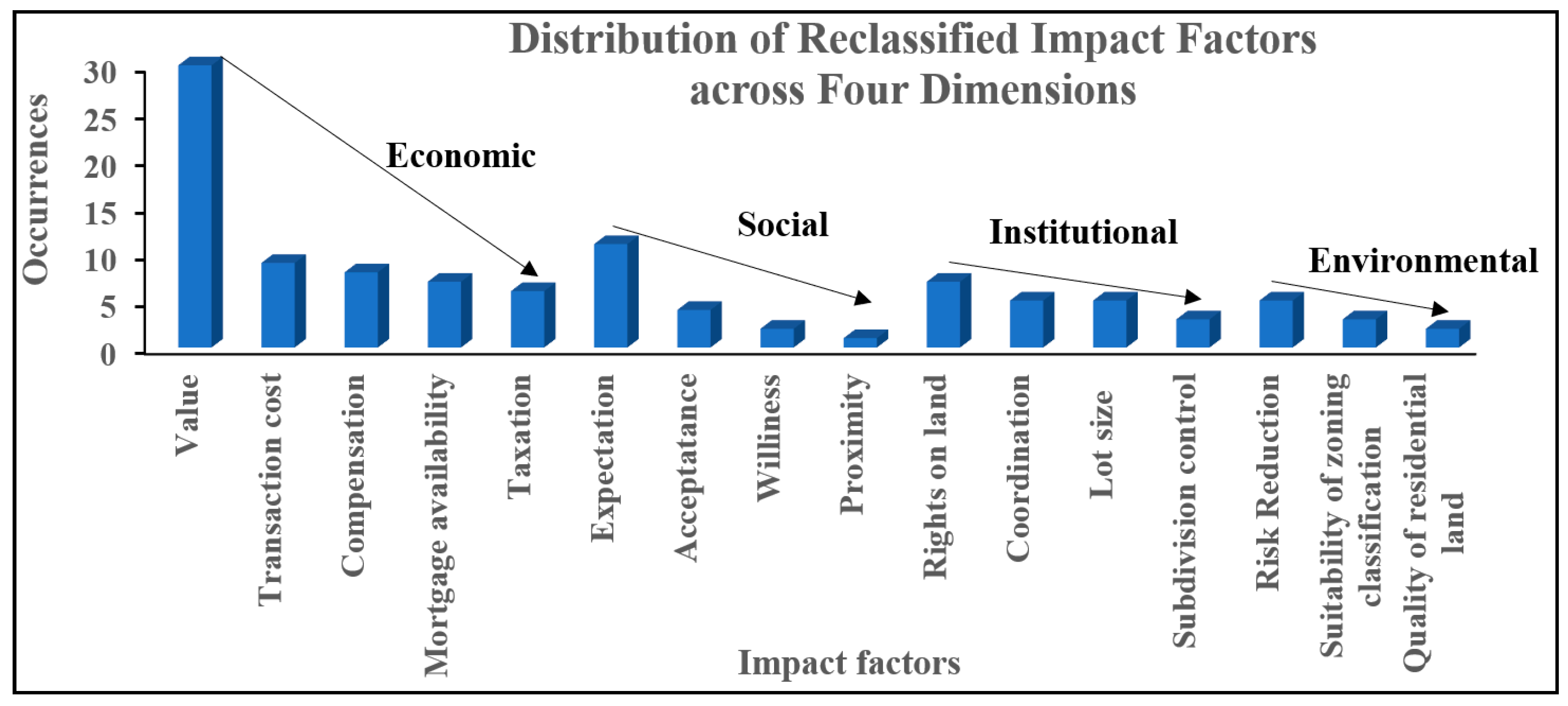

4.1. Identification of Land Market Impact Factors through Desktop Review

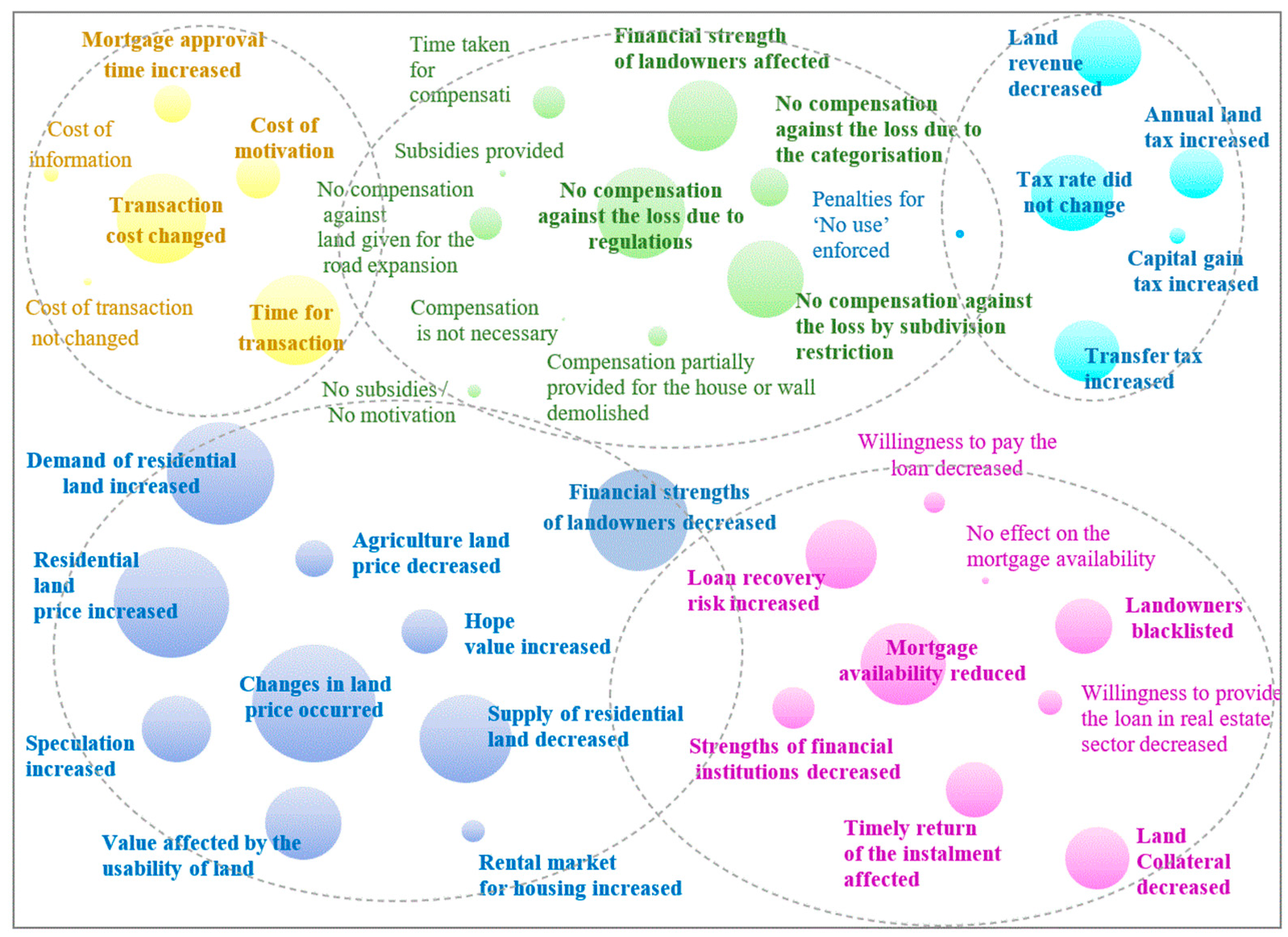

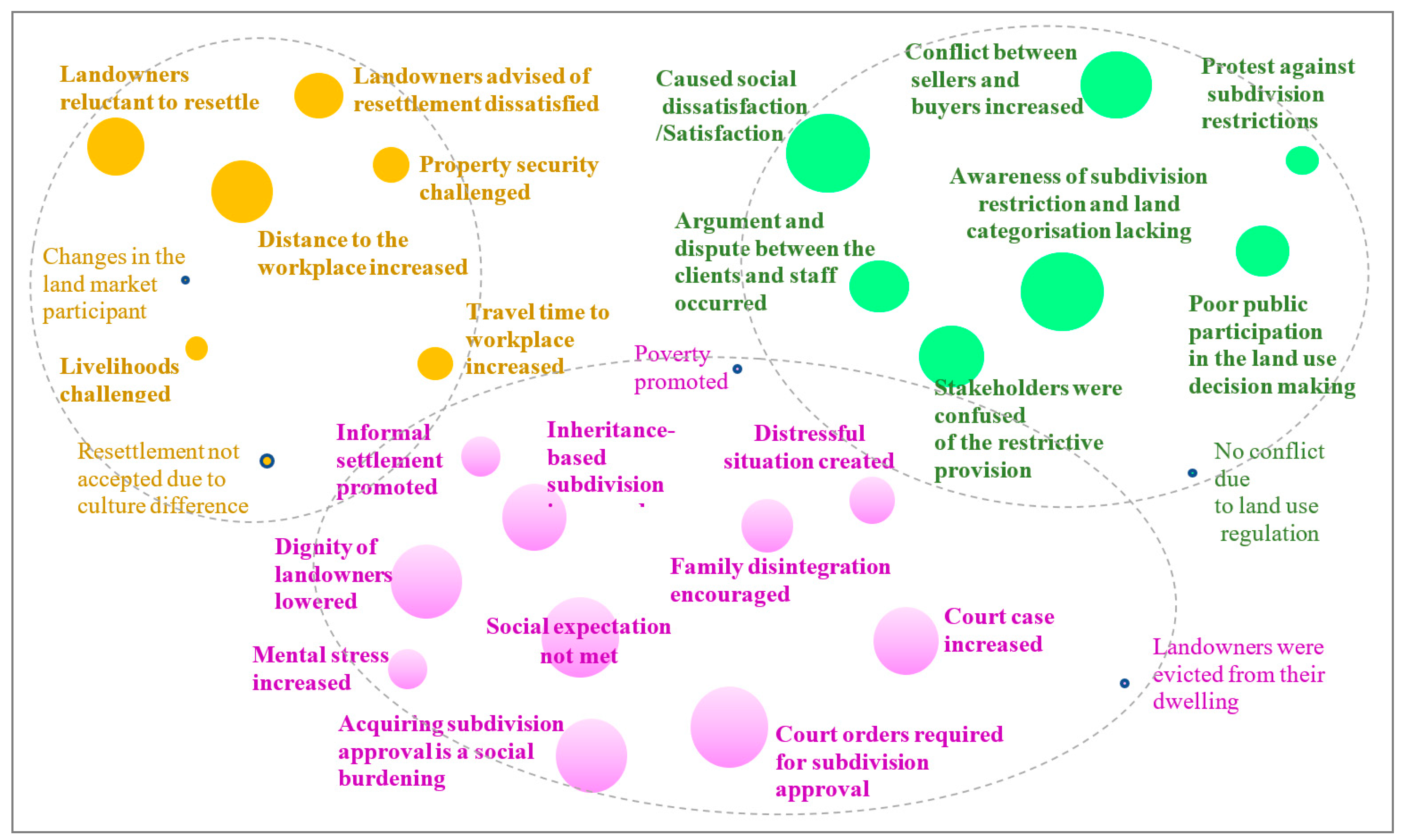

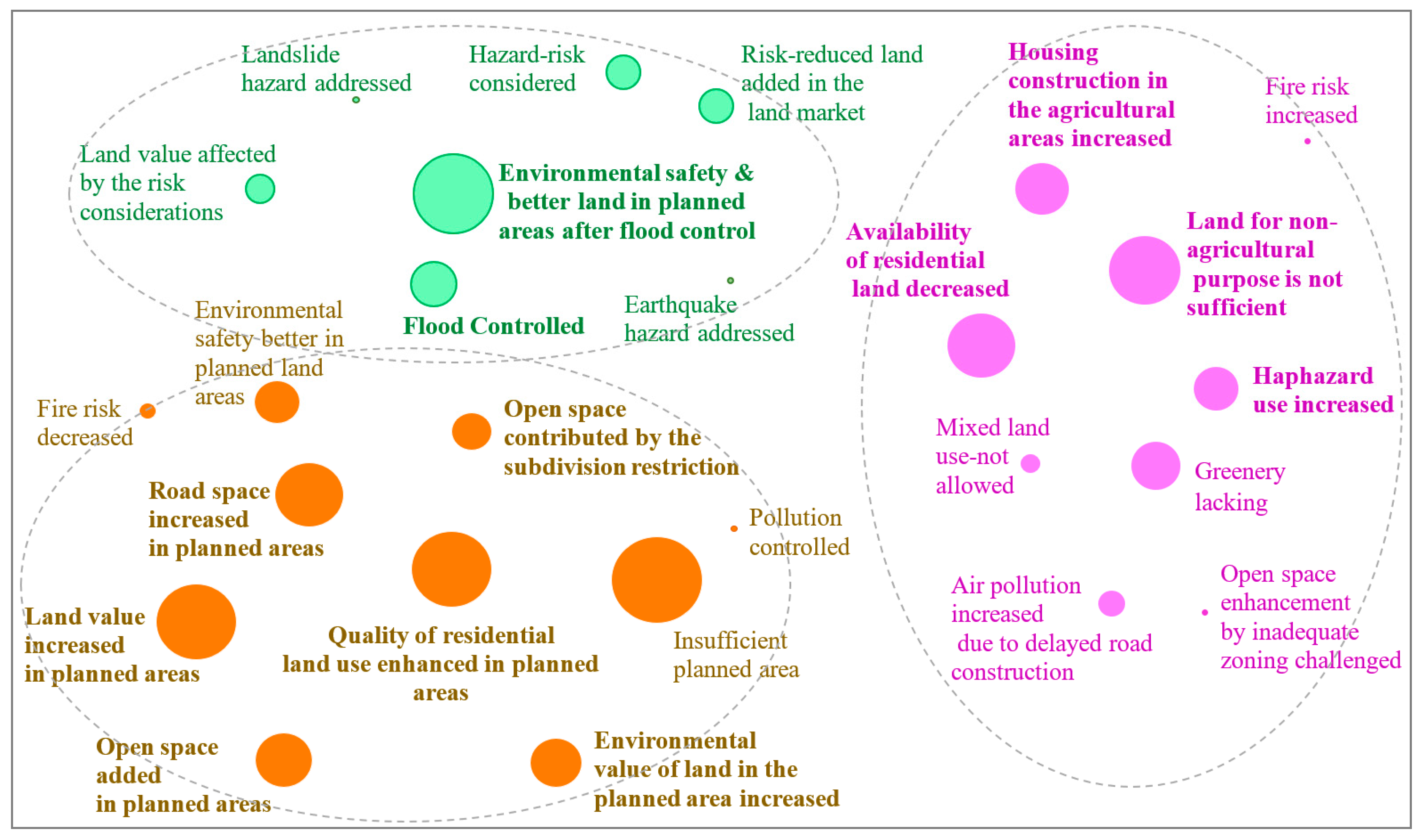

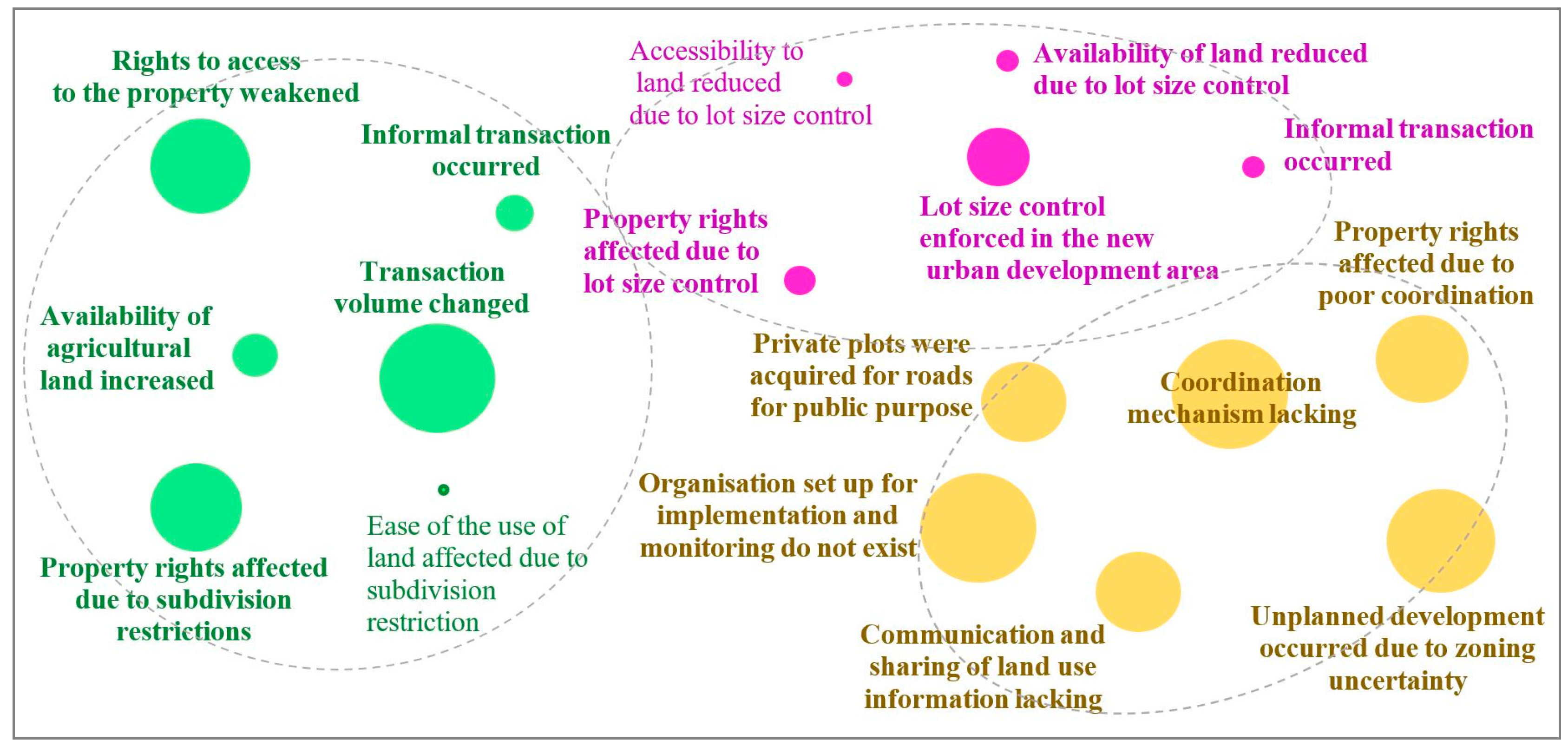

4.2. Impact Factors Based on Stakeholder’s Perspective

4.3. Refinement of Land Market Impact Factors

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enemark, S. Building Land Information Policies. In Proceedings of the UN, FIG, PC IDEA Inter-regional Special Forum on The Building of Land Information Policies in the Americas; Aguascalientes, Mexico, 26–27 October 2004; pp. 1-20. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/2004/mexico/papers_eng/ts2_enemark_eng.pdf (Accessed on 02/08/2023).

- Enemark, S. The Land Management Paradigm for Institutional Development. In Proceedings of the Expert Group Meeting on Incorporating Sustainable Development Objectives into ICT Enabled Land Administration Systems; Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land Administration, University of Melbourne, Australia, 2005, pp. 1-14. https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/2935555/SE_Melbourne_2005.pdf (Accessed on 06/12/2023).

- Enemark, S. Sustainable Land Administration Infrastructures to Support Natural Disaster Prevention and Management. In Proceedings of the 9th United Nations Regional Cartographic Conference for the Americas; New York, 10-14 August 2009; pp. 1-16. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/geoinfo/RCC/docs/rcca9/ip/9th_UNRCCA_econf.99_IP6.pdf (Accessed on 17/02/2024).

- Jaeger, W.K. The Effects of Land-Use Regulations on Property Values. Environmental Law 2006, 36(1), 105-130.

- Needham, B.; Segeren, A.; Buitelaar, E. Institutions in Theories of Land Markets: Illustrated by the Dutch Market for Agricultural Land. Urban Studies Journal 2011 48(1), 161–176. [CrossRef]

- Dowall, E.D. Benefits of Minimal Land-Use Regulations in Developing Countries. Carto Journal 1992, 12(2), 413-423.

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R. The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices. Journal of Urban Economics 2007, 61(3), 420-435. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development; ESRI Press: California, USA, 2010.

- Lees, K. Quantifying the Costs of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from New Zealand. New Zealand Economic Papers 2018, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Jalali, D.; MacDonald, H.; Fini, A.A.F.; Shi, S. Effects of Planning Regulations on Housing and Land Markets: A System Dynamics Modeling Approach. Cities 2022, 126, 103670. [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, D.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Toska, E. Urbanisation and Land Use Planning for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Case Study of Greece. Urban Science 2023, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K. Dynamics and Resource Use Efficiency of Agricultural Land Sales and Rental Market in India. Land Use Policy 2009, 26(3), 736-743. [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P.; Hilber, C. Land Use Planning: The Impact on Retail Productivity. CenterPiece, The Centre for Economic Performance June 2011, pp. 25-28. Online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239806106_Land_use_planning_the_impact_on_retail_productivity (Accessed on 07/02/2024).

- Cheshire, P. Broken Market or Broken Policy? The Unintended Consequences of Restrictive Planning. . JEL R9-R19 2018, 245 (1), R9-R19 ISSN 0027-9501. [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.C.d.A.; Silveira Neto, R.d.M. Zoning Ordinances and the Housing Market in Developing Countries: Evidence from Brazilian Municipalities. Journal of Housing Economics 2019, 46, 101653. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Takano, K. Estimating the Effect of Land Use Regulation on Land Price: At the Kink Point of Building Height Limits in Fukuoka. Regional Science and Urban Economics 2023, 103, 103955. [CrossRef]

- Government of Nepal. Ministerial Decree on the Subdivison of Agricultural Land, Ministry of Land Reform and Management, Government of Nepal, 2017.

- Himalyan New Service. Decision to Restrict Plotting of Arable Land Rescinded by SC. The Himalayan Times, Himalayn News Service 25/08/2017 2017, pp. 1-16. Online: https://thehimalayantimes.com/business/decision-to-restrict-plotting-of-arable-land-rescinded-by-supreme-court/ (Accessed on 15/01/2024).

- Rimal, P. Apex Court Upholds MoLRM’s Decision, Says Prevention of Disintegration of Arable Land in Conformity With Law. The Himalayan Times 18/05/2018 2018, pp. 1-20. Online: https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/supreme-court-verdict-to-escalate-cost-of-road-expansion-projects (Accessed on 18/01/2024).

- Dowall, D.E. The Land Market Assessment: A New Tool for Urban Management. In Proceedings of the Urban Management Programme Discussion Paper UMPP no. 4 Washington, D.C., 1995; p. 68. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/296941468764366469/The-land-market-assessment-a-new-tool-for-urban-management (Accessed on 24/01/2024).

- Dale, P.; Mahoney, R.; McLaren, R. Land Markets and the Modern Economy, Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, 2006, pp. 1-27.

- Cheshire, P.; Sheppard, S. The Welfare Economics of Land Use Planning. Journal of Urban Economics 2002, 52(2), 242-269. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B. Land Tenure and Land Registration in Nepal. In Proceedings of the Integrating Generations; Stockholm, Sweden, 2008, FIG Working Week 2008, pp. 1-13. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2008/papers/ts07b/ts07b_02_acharya_2747.pdf (Accessed on 27/01/2024).

- Tuladhar, A.M. Parcel-Based Geo-Information Systems: Concepts and Guidelines. Thesis, International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, ITC, Dissertation Series No. 115, the Netherlands, 2004.

- Government of Nepal. National Land Use Policy 2012, Ministry of Land Reform and Management, Government of Nepal, 2012.

- Government of Nepal. Land Use Policy 2015, Government of Nepal, 2015.

- Dahal, T.P.; Shrestha, R.; Nepai, P.N. Land Use Policies in Nepal: Implications for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Development; Roma, Italy, 2020, ICSD 2020. (Accessed on.

- Government of Nepal. Land Use Act 2019, Government of Nepal, 2019.

- Government of Nepal. Land Use Regulations 2022, Government of Nepal, 2022.

- Upreti, B.R.; Breu, T.; Ghale, Y. New Challenges in Land Use in Nepal: Reflections on the Booming Real-estate Sector in Chitwan and Kathmandu Valley. Scottish Geographical Journal, 133:1, 69-82, 2017, 133(1), 69-82. [CrossRef]

- KC, B.; Wang, T.; Gentle, P. Internal Migration and Land Use and Land Cover Changes in the Middle Mountains of Nepal. Mountain Research and Development 2017, 37(4), 446-455. [CrossRef]

- His Majesty’s Government of Nepal. National Urban Policy 2007, Government of Nepal, 2007.

- Stein, D.; Suykens, B. Land Disputes and Settlement Mechanisms in Nepal’s Terai. 2014, 12a; Justice and Security Research Programme (JSRP), The Asia Foundation; UK, pp. 1-21 Online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/56348/1/JSRP_Paper12a_Land_disputes_and_settlement_mechanisms_Suykens_and_Stein_2014.pdf (Accessed on 25/02/2024).

- Paudel, B.; Pandit, J.; Reed, B. Fragmentation and Conversion of Agriculture Land in Nepal and Land Use Policy 2012. 2013, Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Paper No.58880; Munich, Germany, pp. 1-13 Online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/58880 (Accessed on 28/01/2024).

- Dahal, T.P.; Shrestha, R.; Nepai, P.N. Analyzing the Linkages between Land Use Zoning and Food Availability in Nepalese Context. In Proceedings of the Volunteering for the Future - Geospatial Excellence for a Better Living; Warsaw, Poland, 2022, FIG Congress. http://eco.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2022/papers/ts03c/TS03C_dahal_shrestha_et_al_11581_abs.pdf (Accessed on 17/02/2024).

- Dale, P.; Baldwin, R. Lessons from the Emerging Land Markets in Central and Eastern Europe. In Proceedings of the Quo Vadis: International Conference Proceedings, FIG Working Week; Prague, Chez Republic, 2000, FIG, pp. 1-36. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/2000/prague-final-papers/baldwin-dale.htm (Accessed on 25/11/2023).

- Dale, P.F.; McLaughlin, J.D. Land Administration; Oxford University Press: 1999.

- Nepal, H.; Marasini, A. Status of Land Tenure Security in Nepal. Nepalese Journal on Geoinformatics 2018, 17(1), 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Tuladhar, A.; Sharma, S.R. Land Valuation and Management Issues in Nepal. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Strengthening Opportunity for Professional Development & Spatial Data Infrastructure Development; Kathmandu, Nepal, 2015, FIG – ISPRS workshop 2015, pp. 1-10. https://fig.net/resources/proceedings/2015/2015_11_nepal/T.S.6.5.pdf (Accessed on 18/01/2024).

- Nepal Rastra Bank. Optimal Number of Banks and Financial Institutions in Nepal, Nepal Rastra Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2022, pp. 1-58.

- His Majesty’s Government of Nepal. Land Revenue Act 1978, His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, 1978.

- Nepal Rastra Bank. A Report on Real Estate Financing in Nepal: A Case Study of Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Rastra Bank, Economic Analysis Division, Research Department, Nepal, 2011.

- His Majesty’s Government of Nepal. Land Act 1964, His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, 1964.

- His Majesty’s Government of Nepal. Land Survey and Measurement Act 1963, His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, 1963.

- El-Barmelgy, M.M.; Shalaby, A.M.; Nassar, U.A.; Ali, S.M. Economic Land Use Theory and Land Value in Value Model. International Journal of Economics and Statistics 2014, 2(1), 91-98.

- Howard, J.A.; Sheth, J.N. The Theory of Buyer Behavior. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1969, 467-487. [CrossRef]

- Courant, P.N. On the Effect of Fiscal Zoning on Land and Housing Values. Journal of Urban Economics 1976, 3, 88-94. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J. Land Use Changes: Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts. 2008, 4; Agricultural & Applied Economics Association; Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Oregon State University, pp. 6-10 Online: http://www.choicesmagazine.org/UserFiles/file/article_49.pdf (Accessed on 02/03/2024).

- Ciaian, P.; Kancs, d.A.; Swinnen, J.; Van Herck, K.; Vranken, L. Institutional Factors Affecting Agricultural Land Markets. 2012, No. 16; Factor Markets, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS); Brussels, Belgium, pp. 1-19 Online: https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/institutional-factors-affecting-agricultural-land-markets/ (Accessed on 13/02/2024).

- Monkkonen, P.; Ronconi, L. Land Use Regulations, Compliance and Land Markets in Argentina. Urban Studies 2013, 50(10), 1951-1969. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.R. Land-property Markets and Planning: A Special Case. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 533-540. [CrossRef]

- Luca, L. Romanian Land Market Regulatory Framework: The Legislative Corrections in 2014. Agricultural Economics and Rural Development 2014, 11(2), 203-212.

- Woestenburg, A. The Issue of Value and Price in Land Market Research. In Proceedings of the FIG Congress 2014 Engaging the Challenges – Enhancing the Relevance Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 16-21 June 2014 2014; pp. 1-9. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2014/papers/ts04f/TS04F_woestenburg_7255.pdf (Accessed on 06/02/2024).

- Dirgasova, K.; Bandlerova, A.; Lazikova, J. Factors Affecting the Price of Agricultural Land in Slovakia. Journal of Central European Agriculture 2017, 18(2), 291-304. [CrossRef]

- Ohls, J.C.; Weibserg, R.C.; White, M.J. The Effect of Zoning on Land Value. Journal of Urban Economics 1974, 1(4), 428-444. [CrossRef]

- Muller, A. Valuation of Land and Building for the Recurrent Property Tax and for Other Taxes. 2002, World Bank, USA, pp. 123-130 Online: http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/tax/valuation.htm (Accessed on 17/05/2019).

- Mangioni, V. Modernising Compensation Principles for the Regeneration of Land Uses in Highly Urbanised Locations. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, FIG Congress 2014, p. 15. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2014/papers/ts01f/TS01F_mangioni_6844.pdf (Accessed on 18/01/2024).

- Deininger, K. Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction, The World Bank, Washington, D. C., 2003, p. 239.

- Deininger, K.; Augustinus, C.; Enemark, S.; Munro-Faure, P. Innovations in Land Rights Recognition, Administration and Governance, The World Bank, Washington, D. C., 2010.

- Tuladhar, A.M.; van der Molen, P. Customer Satisfaction Model and Organisation Strategies for Registration and Cadastral Systems. In Proceedings of the 2nd Cadastral Congress; Kraków, Poland, 2003, 2nd Cadastral Congress, pp. 43-52. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228811025_Customer_satisfaction_model_and_organizational_strategies_for_land_registration_and_cadastral_systems (Accessed on 29/12/2023).

- Mayer, C.J.; Somerville, C.T. Land Use Regulation and New Construction. Regional Science and Urban Economics 2000, 30(6), 639-662. [CrossRef]

- National Land Use Project. Bhu-Upayog Nirdeshika (Land Use Program Implementation Directive), National Land Use Project, Government of Nepal, 2013.

- Kathmandu Valley Development Authority. Support to Develop Risk Sensitive Land Use Plan (RSLUP) and Building Bye-Laws of Kathmandu Valley, Kathmandu Valley Development Authority, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2015, p. 108.

- Schirmer, J. Socio-Economic Impacts of Land Use Change to Plantation Forestry: A Review of Current Knowledge and Case Studies of Australian Experience. 2014, pp. 1-11 Online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242294421_SocioEconomic_Impacts_of_Land_Use_Change_to_Plantation_Forestry_A_Review_of_Current_Knowledge_and_Case_Studies_of_Australian_Experience (Accessed on 25/01/2024).

- Loxton, E.A.; Schirmer, J.; Kanowski, P. Exploring the Social Dimensions and Complexity of Cumulative Impacts: A Case Study of Forest Policy Changes in Western Australia. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2013, 31(1), 52-63. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A. Traffic Police Division Announces Plan to Intensify ‘no horn’ Campaign. The Himalayan Times 30/05/2019 2019, pp. 1-3. Online: https://kathmandupost.com/valley/2019/05/30/traffic-police-division-announces-plan-to-intensify-no-horn-campaign (Accessed on 12/03/2024).

- Karki, T.K. Implementation Experiences of Land Pooling Projects in Kathmandu Valley. Habitat International 2004, 28(1), 67-88. [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J.; Dalton, L.C. Plans Can Matter! The Role of Land Use Plans and State Planning Mandates in Limiting the Development of Hazardous Areas. Public Administration Review 1994, 54(3), 229-238. [CrossRef]

- National Planning Commission. A Study Report for the Feasability of Integrated Settlement Planning in Bajura District, National Planning Commission, Kathmandu, 2015, pp. 1-35.

- Singh, P. Integrated Plan Ready for Bajura Development The Himalayan Times 05/08/2015 2015, p. 1. Online: https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/integrated-plan-ready-for-bajura-development/ (Accessed on 19/02/2024).

- Potsiou, C.A. Land Markets and e-Society, International Trends and the Situation in Greece. In Proceedings of the eGovernance, Knowledge Management and eLearning; Budapest, Hungary, 2006, FIG Workshop 2006, pp. 1-18. https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/2006/budapest_2006_comm2/papers/ts05_04_potsiou.pdf (Accessed on 13/03/2024).

- Godschalk, D.R. Land Use Planning Challenges: Coping with Conflicts in Visions of Sustainable Development and Livable Communities. Journal of the American Planning Association 2004, 70(1), 5-13. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, H.M. Social Conflict Over Property Rights: The End, a New Beginning, or a Continuing Debate? Housing Policy Debate 2010, 20(3), 329-349. [CrossRef]

- Kamat, R.K. Govt Can’t Acquire Private Land Without Compensation: SC The Himalayan Times 27/09/2018 2019, pp. 1-24. Online: https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/government-cant-acquire-private-land-without-compensation-sc (Accessed on 14/02/2024).

- Khanal, P.; Gurung, A.; Chand, P.B. Road Expansion and Urban Highways: Consequences Outweigh Benefits in Kathmandu. Himalaya, The Journal of Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 2017, 37(1), 107-116.

- Lodin, M.; Sonila, J.; Onsrud, H. Key Factors for Success in Land Administration Projects – Lessons Learned from Projects in South-East Europe. In Proceedings of the Linking Land Tenure and Use for Shared Prosperity; Washington, D. C., 23-27 March 2015; pp. 1-8. https://www.kartverket.no/globalassets/om-kartverket/centre-for-property-rights/wb-2015-paper-684-onsrud.pdf (Accessed on 06/07/2019).

- Koirala, P.K. Urbanisation in Kathmandu Valley, Legal Situation and Way Forward. In Commitment: Reflections and Revelations, KVDA, Ed.; Kathmandu Valley Development Authroity: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2015; pp. 88-94.

- Lees, K. Quantifying the Impact of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from New Zealand, ISBN 978-0-947489-94-6; Sense Partners, Report for Superu, Ministerial Social Sector Research Fund., 2017, pp. 1-8.

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. Journal of Business Research 2019, 104, 333-339. [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 2003, 14(3), 207-222. [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. National Census 2021: A Summary, Office of the Prime Minister, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal, p. 198.

- Ministry of Land Reform and Management. A Brief Introduction to the Ministry of Land Reform and Management and its Umbrella Organisations: Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2011/2012, 2012.

- Nepal Rastra Bank. Quarterly Bulletin. 2019.

- Nepal Rastra Bank. The Share of Kathmandu Valley in the National Economy, Nepal Rastra Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2012, pp. 1-19.

- Lillis, A.M. A Framework for the Analysis of Interview Data from Multiple Field Research Sites. Accounting & Finance 1999, 39(1), 79-105. [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd. ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: 1994.

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th Edition ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC., 2009; Volume 5.

- Reps, J.W.; Smith, J.L. Control of Urban Land Subdivision. Syracuse Law Review 1962, 14(3), 405-425.

- Shultz, M.M.; Groy, J.B. The Failure of Subdivision Control in the Western United States: A Blueprint for Local Government Action. Utah Law Review 1988, 569(1988), 571-674.

- Bertaud, A.; Malpezzi, S. Measuring the Costs and Benefits of Urban Land Use Regulation: A Simple Model with an Application to Malaysia. Journal of Housing Economics 2001, 10, 393–418. [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Land Administration in the UNECE Region-Development Trends and Main Principles; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: New York and Geneva, 2005.

- Wallace, J.; Williamson, I. Building Land Markets. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P.; Vermeulen, W. Land Markets and Their Regulation: The Welfare Economics of Planning. In International Handbook of Urban Policy, Geyer, H., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK. ISBN 9781847204592, 2009; Volume Vol. II : Issues in the Developed World, pp. 151-193.

- Glaeser, E.L.; Ward, B.A. The Cause and Consequences of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from Greater Boston. Journal of Urban Economics 2009, 65(2), 265-278. [CrossRef]

- Copenheaver, C.A.; Kidd, K.R.; Shockey, D.M.; Stephens, B.A. Environmental and Social Factors Influencing the Price of Land in Southwestern Virginia, USA, 1786–1830. Mountain Research and Development 2014, 34(4), 386-395. [CrossRef]

- Faust, A.; Castro-Wooldridge, V.; Chitrakar, B.; Pradhan, P. Land Pooling in Nepal. 2020, 72; Asian Development Bank; Manila, the Philippines, p. 62 Online: https://www.adb.org/publications/land-pooling-nepal (Accessed on 21/02/2024).

- Wen, L.; Yang, S.; Qi, M.; Zhang, A. How does China’s Rural Collective Commercialised Land Market Run? New Evidence from 26 Pilot Areas, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 136, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, W.S.A.; Kilvington, M. Innovative Land Use Planning for Natural Hazard Risk Reduction: A Consequence-Driven Approach from New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2016, 18, 244-255. [CrossRef]

| SN | Articles | Initially collected | Dropped | Selected articles for in-depth study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Journal based | 70 | 46 | 24 |

| 2 | Conference proceedings/ Conference paper | 27 | 21 | 6 |

| 3 | Report and guidelines from government authorities and global financial and welfare organizations | 17 | 12 | 5 |

| 4 | Books /book section | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| 5 | Others (Magazine articles, guidelines, thesis, unpublished articles | 17 | 12 | 5 |

| Total | 139 | 96 | 43 |

| Authors | Impact factors/Indicators |

|---|---|

| Reps and Smith [88] | Subdivision control, supply |

| Ohls, Weibserg and White [55] | Price, value |

| Courant [47] | Land price |

| Shultz and Groy [89] | Subdivision control, supply |

| Dowall [6] | Supply, price, affordability, sub-division standard, consideration of future requirements (adequacy or suitability of zoning), procedural delays |

| Burby and Dalton [68] | Hazard, risk, land availability |

| Dale and McLaughlin [37] | Laws and institutions, financial instruments and services, land recording and valuation agencies, land rights and records, participants |

| Dale and Baldwin [36] | Credit accessibility, demand, supply, cultural acceptance, transparency, social, environmental and economic sustainability, value for money, tax, transaction cost, openness, accessibility, incentives, clarity, compensation |

| Mayer and Somerville [61] | Delay, red tape, transaction cost |

| Bertaud and Malpezzi [90] | Demand, supply, imposition of higher taxation on consumer |

| Tuladhar and van der Molen [60] | Transaction cost, coordination, customer satisfaction |

| Deininger [58] | Credit accessibility, transparency, productivity, desirability, subsidies, transaction cost |

| Karki [67] | Quality of residential land, supply, open space |

| UNECE [91] | Taxation, valuation, informal settlement, tenure security, conflict, satisfaction, information availability, transaction cost, transparency, affordability, environmental sustainability |

| Potsiou [71] | Availability of land information, access to mortgage and credit, security, content, information quality and availability, tax |

| Jaeger [4] | Value, compensation |

| Wallace and Williamson [92] | Mortgage, lease, land information, securities, information management and availability, credit facility, ownership, cognitive capacity, land rights, coordination |

| Dale, Mahoney and McLaren [21] | Credit accessibility, demand, supply, cultural acceptance, transparency, social, environmental and economic sustainability, value, transaction cost, openness, accessibility, incentives, clarity, compensation |

| Ihlanfeldt [7] | Competitiveness, land price, land value, self-interest, lot size, restriction |

| Wu [48] | Erosion, desertification, land degradation, conflict, affordability, productivity, pollution, fragmentation, incentives |

| Cheshire and Vermeulen [93] | Price, cost, benefit |

| Glaeser and Ward [94] | Demand, supply, price |

| Williamson, Enemark, Wallace and Rajabifard [8] | Mortgage, lease, land information, securities, information management, credit facility, ownership, expectations, land rights, coordination, information availability, taxation, compensation |

| Needham, Segeren and Buitelaar [5] | Transaction cost, expectations, prevalence laws, hope value |

| Ciaian, Kancs, Swinnen, Van Herck and Vranken [49] | Land price, value |

| Monkkonen and Ronconi [50] | Land price |

| Loxton, Schirmer and Kanowski [65] | Distrust, injustice, stress, dissatisfaction |

| Woestenburg [53] | Land value |

| Alexander [51] | Land price |

| Luca [52] | Land price, transaction volume |

| El-Barmelgy, Shalaby, Nassar and Ali [45] | Proximity, social acceptance, price, demand, supply, land values, public interest, hazards |

| Copenheaver, et al. [95] | Land price, value |

| Mangioni [57] | Compensation |

| Schirmer [64] | Employment, identity, land availability |

| Lodin, Sonila and Onsrud [76] | Coordination, local ownership, information technology |

| Government of Nepal [26] | Value, tax, subsidies, compensation, conflict, coordination, fragmentation, disaster, risk, lot size |

| Dirgasova, Bandlerova and Lazikova [54] | Land price, lot size |

| Lees [78] | Housing prices, affordability, supply, demand |

| Cheshire [14] | Value, housing price, transaction delay |

| Faust, et al. [96] | Quality plots, open space, relocation of informal settlements, value, price, inadequate planning, affordability, data sharing, compensation, ad-hoc planning decisions |

| Jalali, MacDonald, Fini and Shi [10] | Price, lot size, building density, urban growth boundary |

| Nakajima and Takano [16] | Price, building heights |

| Wen, et al. [97] | Price, supply, demand |

| Dimension | Preliminary impact factors from desk review | Key theme from the interview | Refined Impact Factor | Impact indicators relevant to the Nepalese land market based on the interview responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Transaction cost | Changes in the transaction cost occurred | Transaction cost | Changes in the cost of the transaction |

| Changes in the time of transaction | ||||

| Valuation | Changes in land value or price occurred differently | Valuation | Changes in the price of residential land | |

| Changes in the price of agricultural land | ||||

| Price speculation due to land categorization or subdivision restriction | ||||

| Mortgage availability | Mortgage availability reduced by the land use regulation | Mortgage availability | Accessibility of land property as collateral | |

| Number of blacklisted landowners | ||||

| Changes in the financial strength of the financial institutions | ||||

| Number of landowners who received loans from financial institutions | ||||

| Taxation | Changes in taxation occurred | Taxation | Changes in land tax | |

| Penalties for no use of the land | ||||

| Compensation | There was inadequate compensation to landowners for the loss due to land use regulation | Compensation | Sufficiency of the compensation paid for loss due to subdivision restriction | |

| Sufficiency of compensation for loss due to road expansion | ||||

| Time required for the payment of compensation | ||||

| Social | Willingness & Acceptance | Low level of awareness of land use regulation created conflict between stakeholders | Awareness | Conflict between sellers and buyers due to lack of awareness of land use regulation |

| Dispute between clients and staff over the failure of parcel subdivision | ||||

| Expectation | Social expectations not met, as revealed by the court cases for subdivision approval | Expectation | Ease of the subdivision approval process | |

| Number of court order cases for subdivision approval | ||||

| Proximity | Landowners dissatisfied with the allocation of resettlement | Proximity | Satisfaction of landowners due to distance to the workplace | |

| Satisfaction of landowners due to travel time to the workplace | ||||

| Changes in the number of landowners/buyers in the land market | ||||

| Environmental | Risk reduction | Risk considerations in land use planning changed supply and value in the land market | Risk reduction | Changes in the area at risk of flooding in the Kathmandu Valley |

| Changes in the supply of flood-safe plots in the Kathmandu Valley | ||||

| Quality of residential land | Changes in the quality of residential land made a difference in the land market by changing the value and supply of such land | Quality of residential land | Supply of residential land with added open space in land pooling areas | |

| Change in the supply of residential land with added enhanced road and utility infrastructure | ||||

| Change in the land value of quality residential plots compared to surrounding unplanned areas | ||||

| Suitability of zoning classification | Inadequate classification did not address the land requirement and promoted haphazard use | Suitability of zoning classification | Sufficiency of land allocated for non-agricultural purpose | |

| Changes in the amount of housing construction in agricultural land of the Kathmandu Valley | ||||

| Institutional | Lot size | Lot size affected the availability of land and accessibility to land rights | Lot size | Number of available parcels qualified for the market transaction |

| Changes in the number of transactions of parcels bigger than the threshold size | ||||

| Changes in the accessibility to land rights | ||||

| Rights on land / Subdivision restrictions | Subdivision restriction affected the availability of land and accessibility to land rights | Subdivision restrictions | Changes in the amount (count) of parcels subdivided | |

| Access to the adjoining parcel to use for road purposes (ease of the use of land) | ||||

| Number of informal transactions | ||||

| Coordination | Poor coordination mechanism affected property rights | Coordination | Number of private lots taken partly by the road expansion | |

| Number of court cases registered against the KVDA to secure property rights |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).