Submitted:

10 April 2024

Posted:

11 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

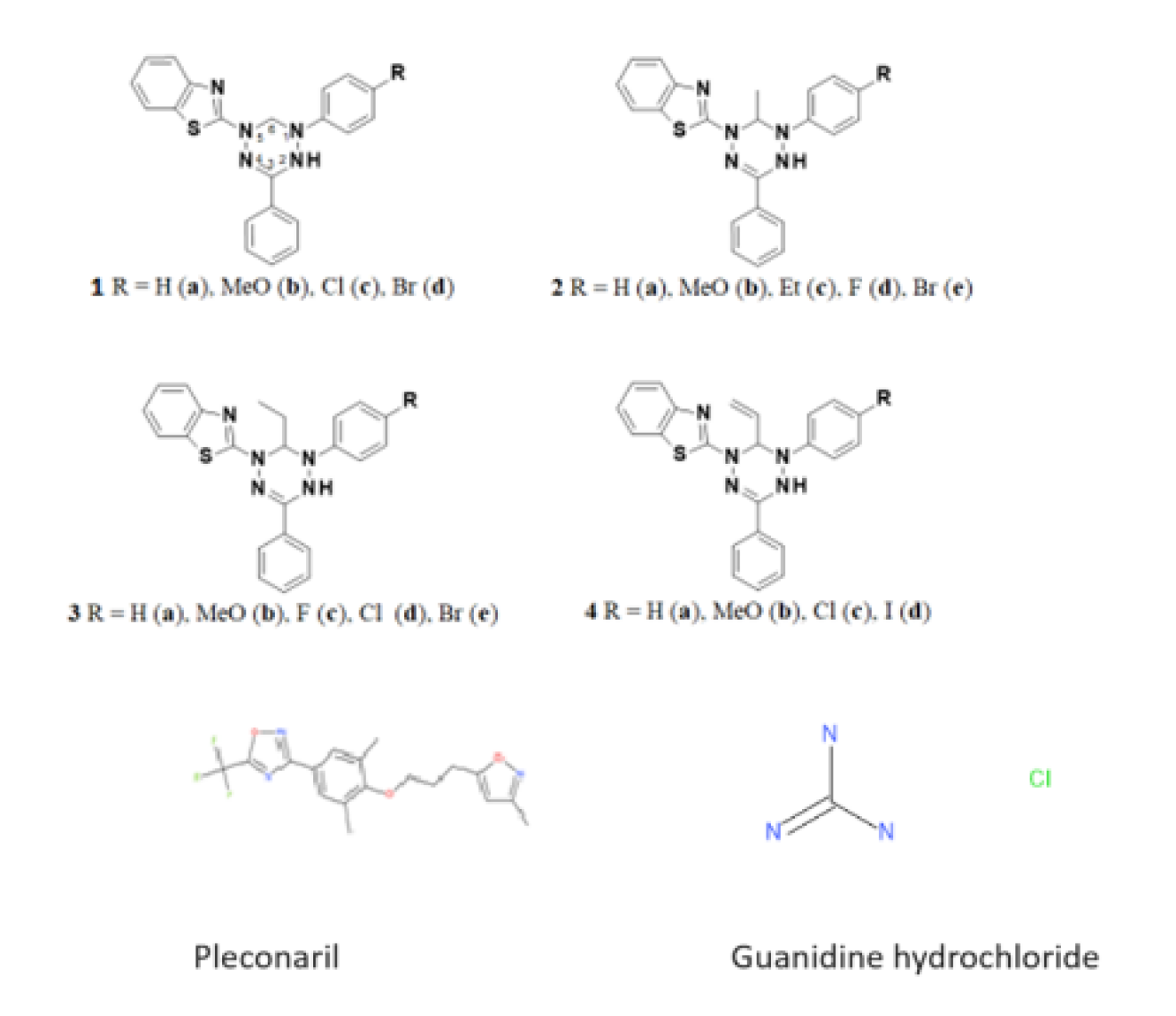

2.1. Compounds

2.2. Viruses and Cell Lines

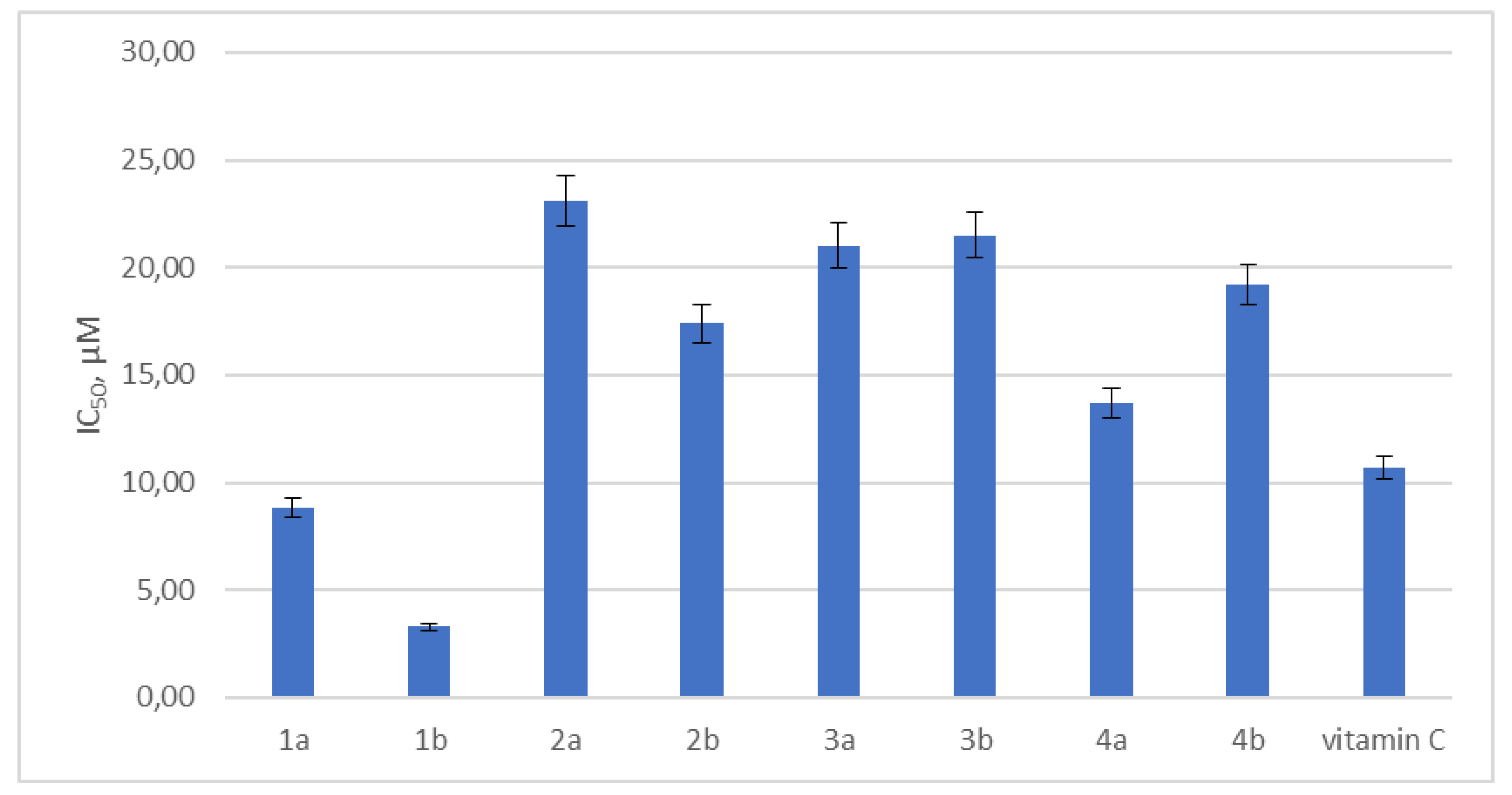

2.3. Antioxidant Activity Testing

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.5. Antiviral Activity Determination

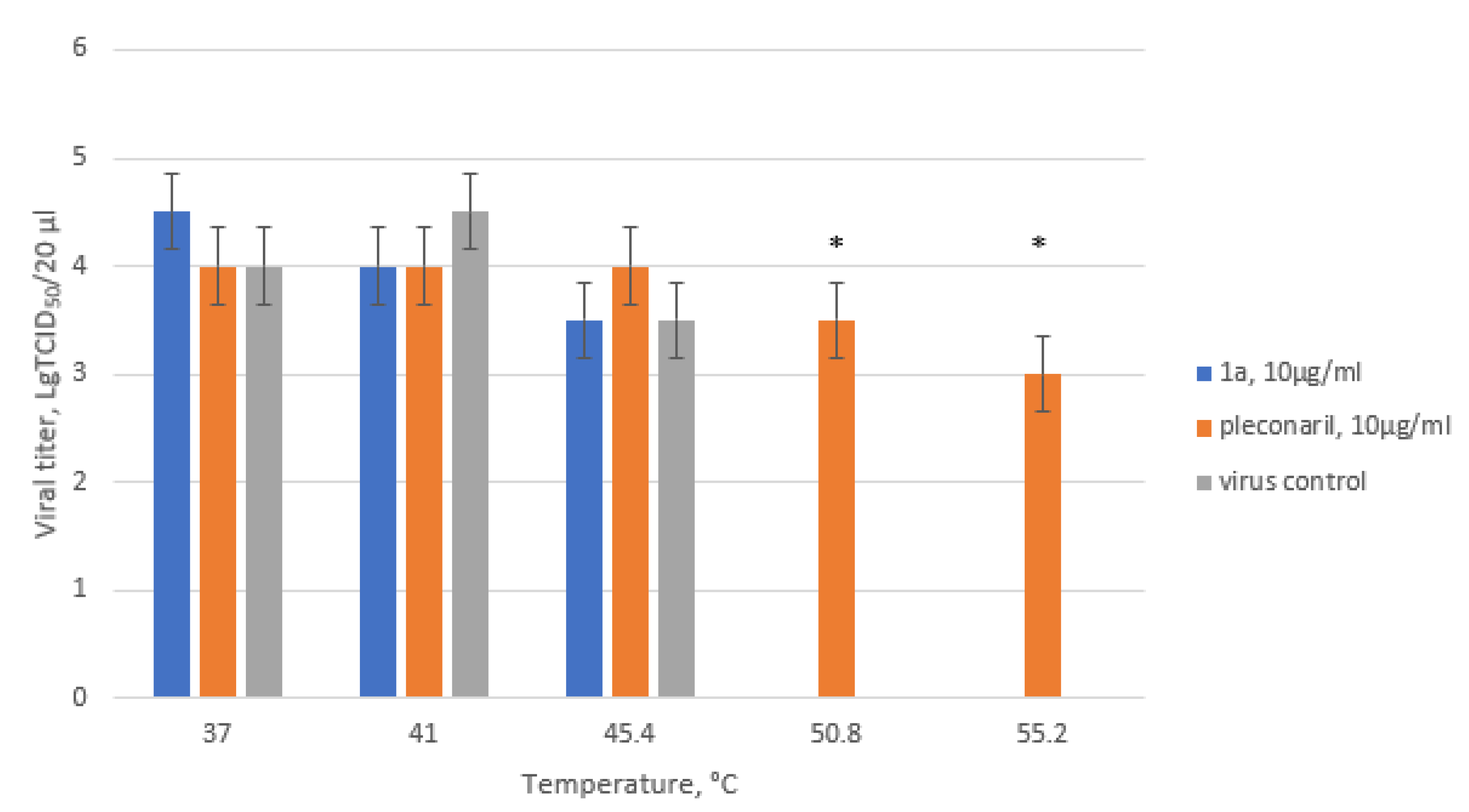

2.6. Thermostability Assay

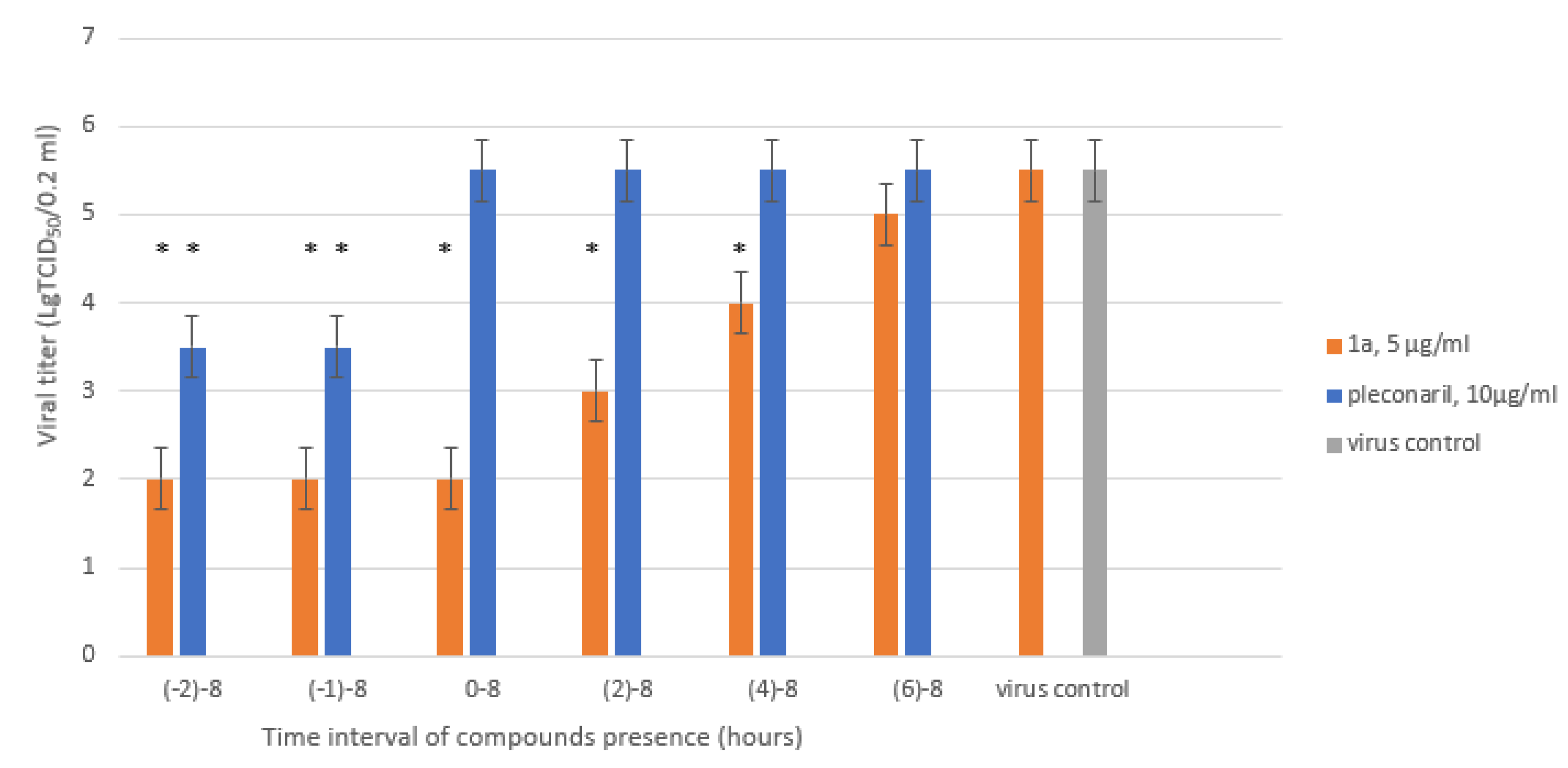

2.7. Time-of-Addition Assay

2.8. Selection and Analysis of the Drug-Resistant Strain

2.9. Growth Kinetics

2.10. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.11. Computer Modeling

2.12. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Leucoverdazyls Are Potent Inhibitors of EVs at Low Micromolar Concentrations

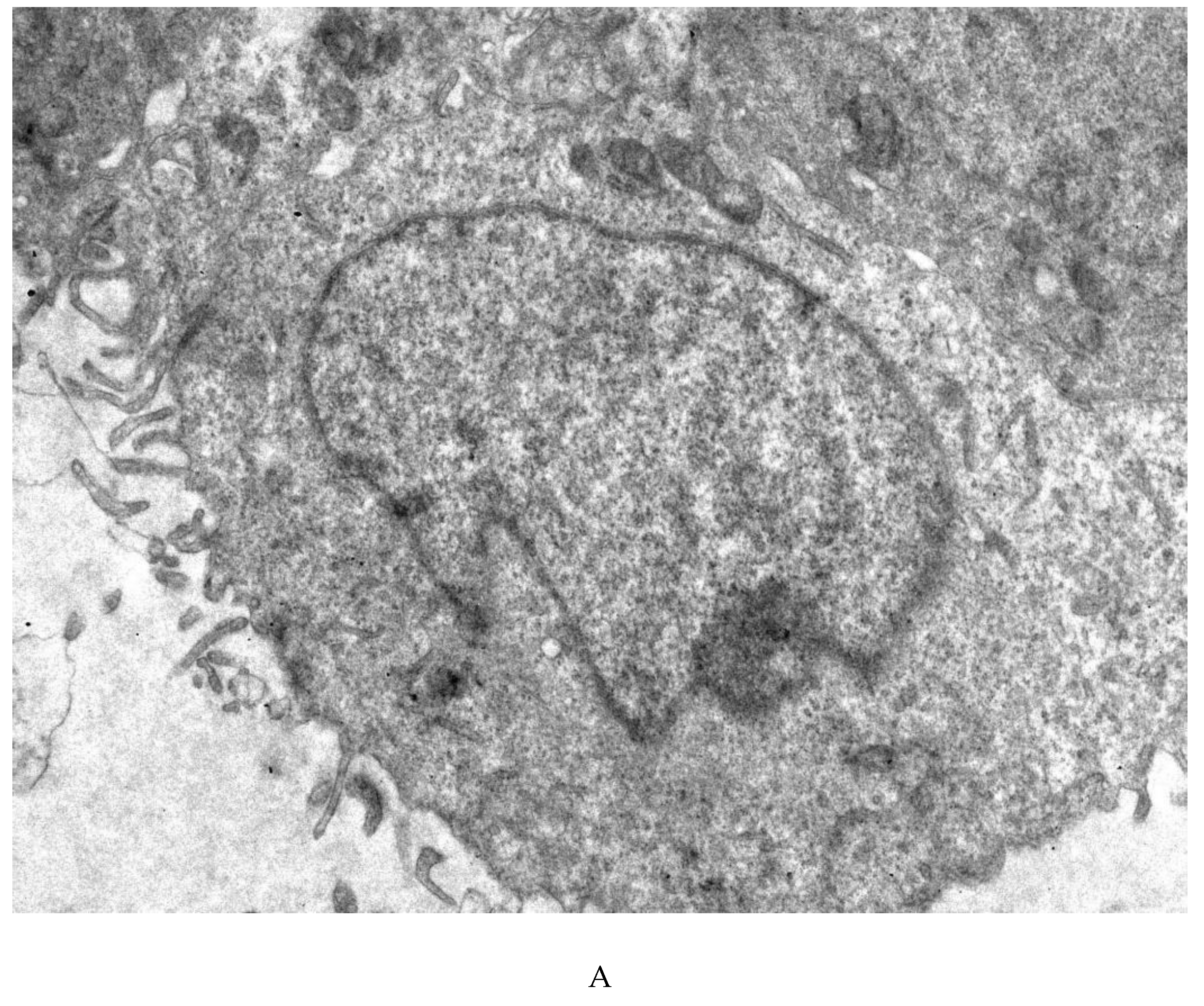

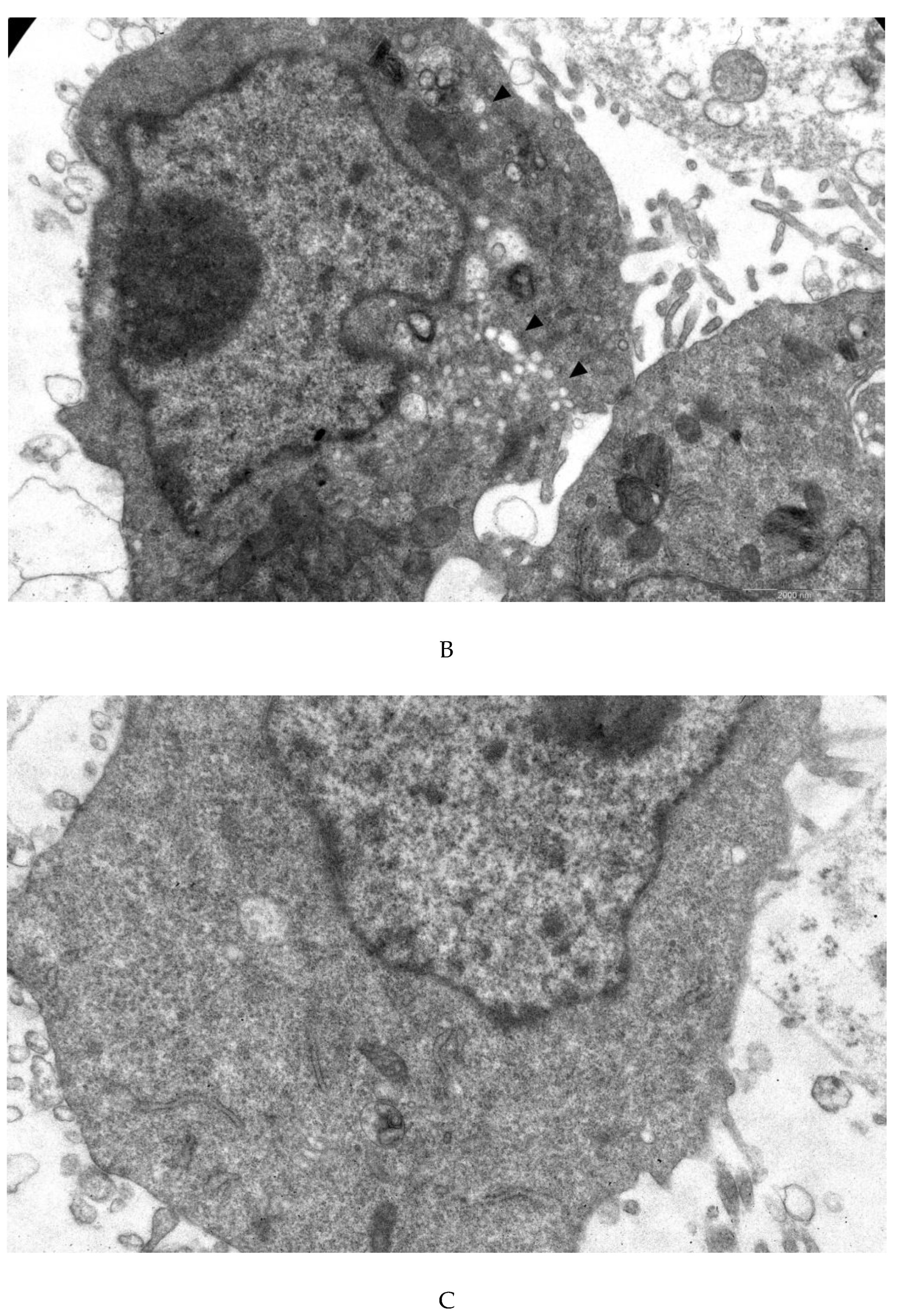

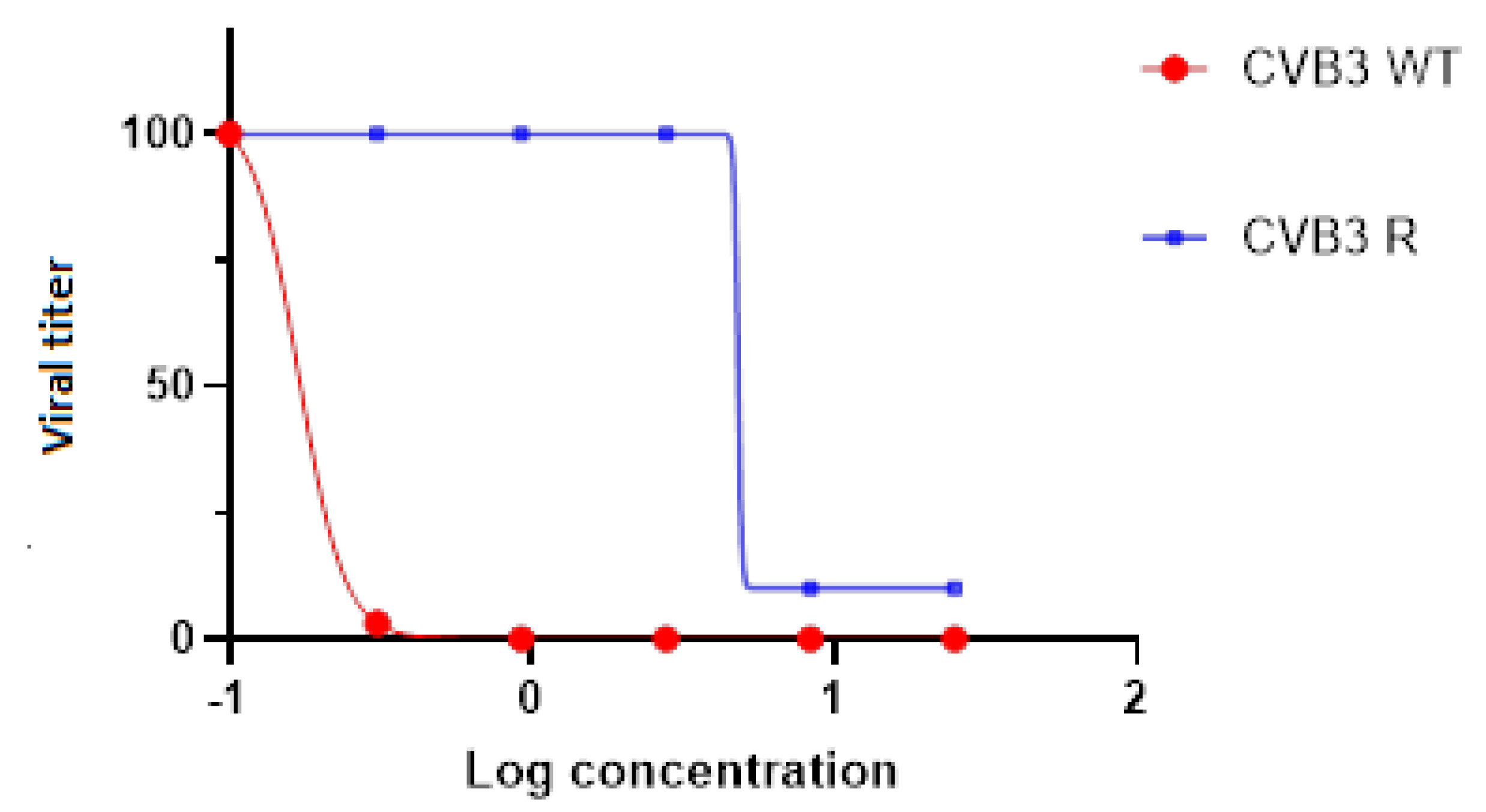

3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy

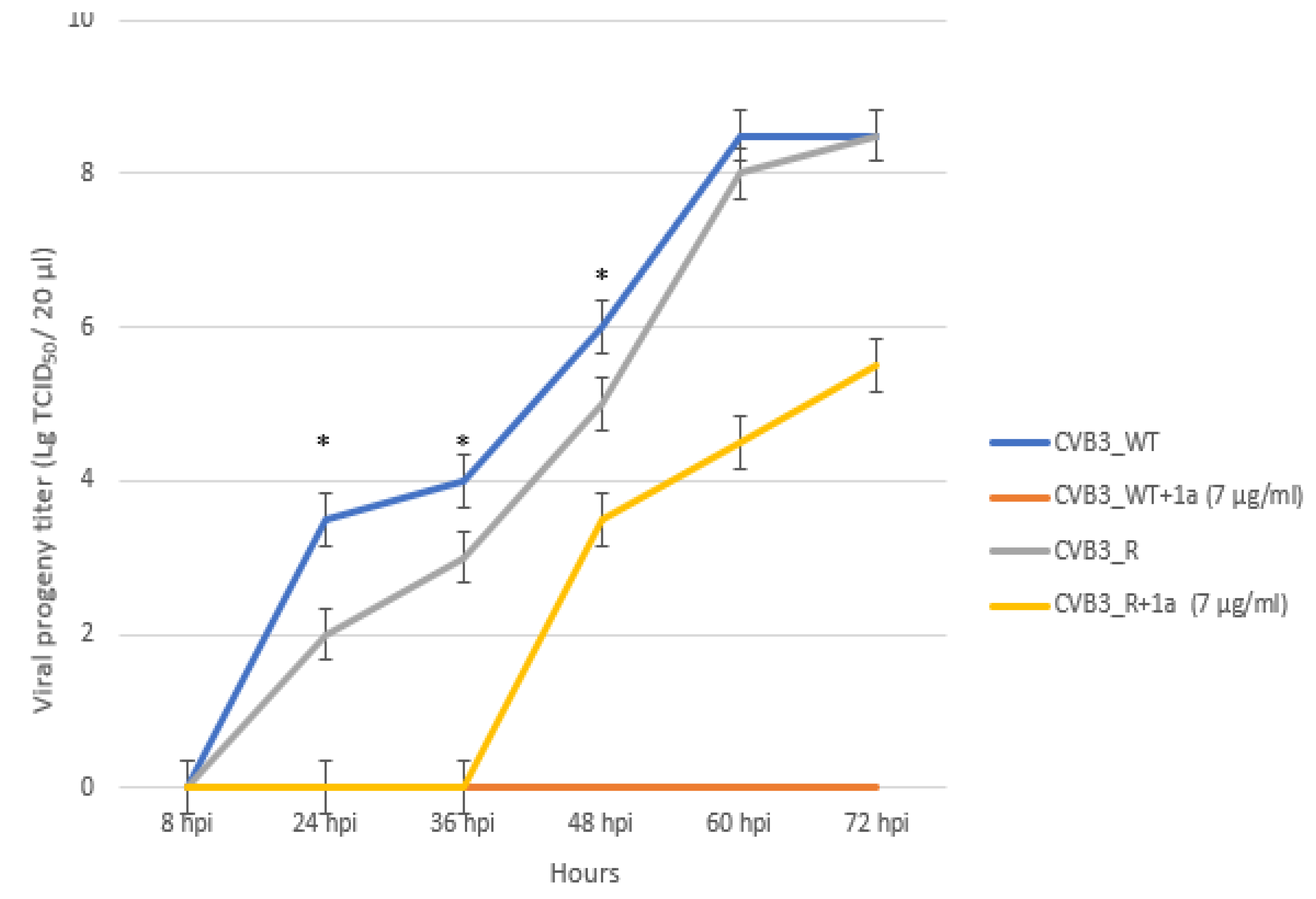

3.5. 1a-Resistant Strain Selection and Its Genomic and Phenotypic Characteristics

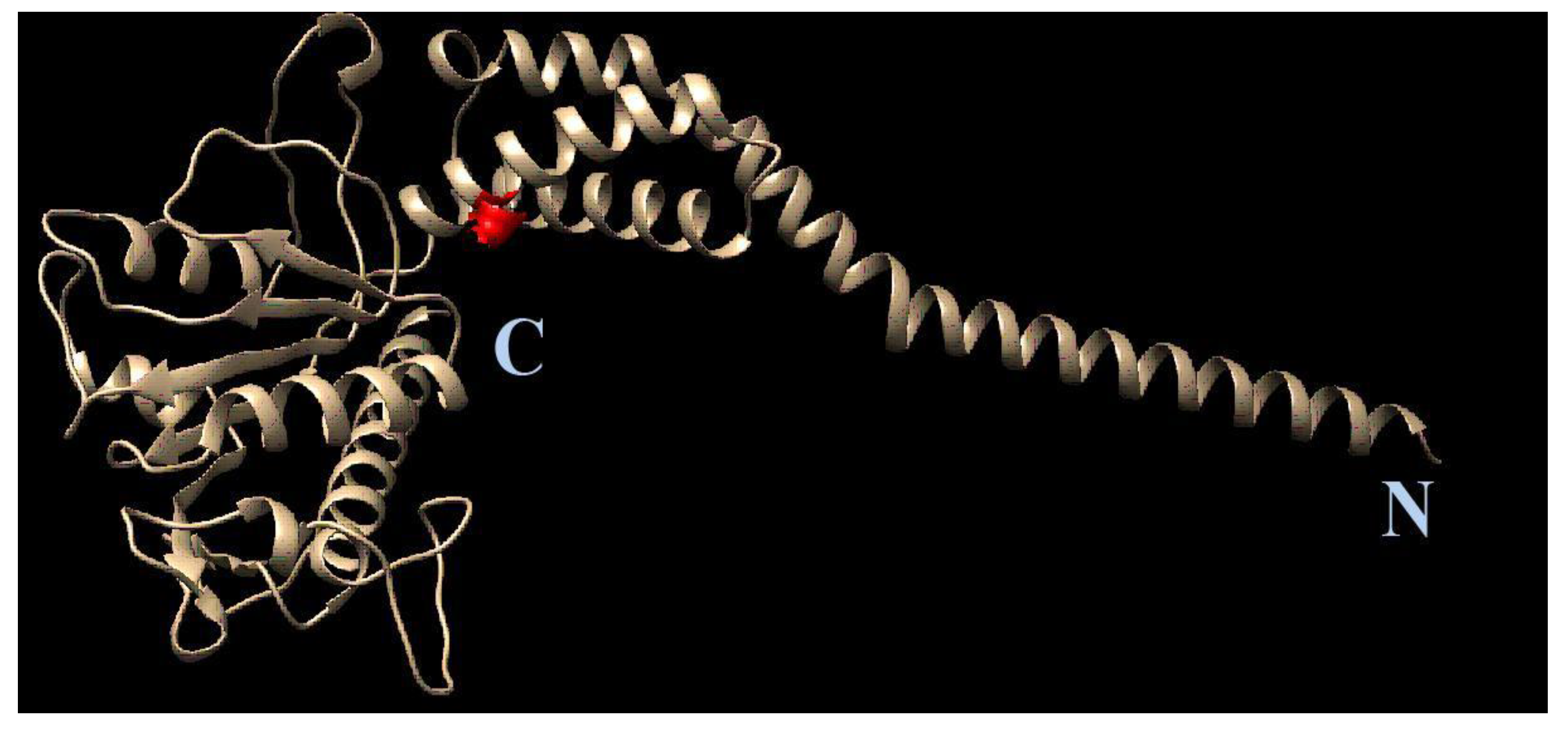

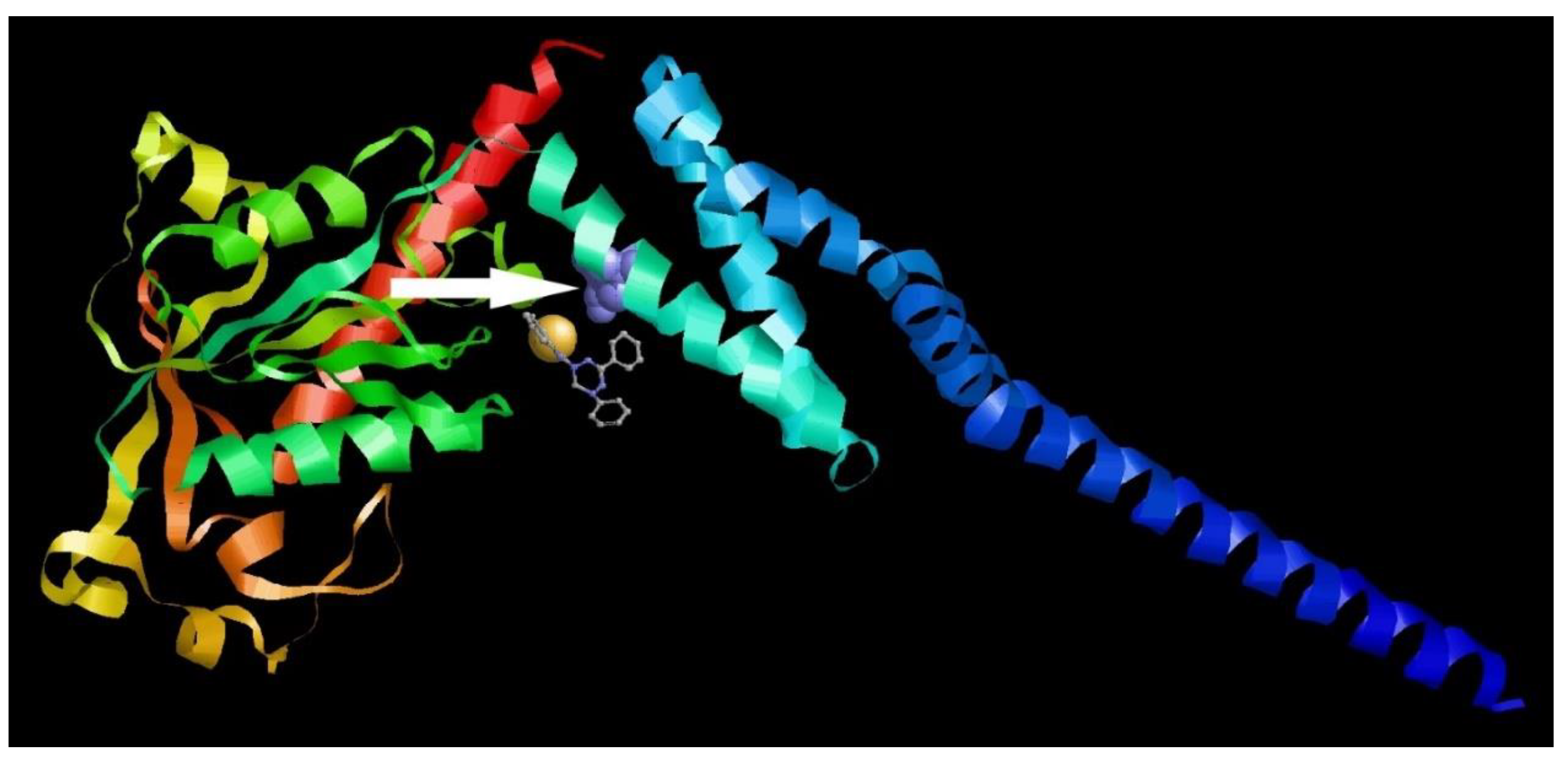

3.6. Molecular Modeling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simmonds, P. , Gorbalenya, A.E., Harvala, H., Hovi, T., Knowles, N.J., Lindberg, A.M., Oberste, M.S., Palmenberg, A.C., Reuter, G., Skern, T., Tapparel, C., Wolthers, K.C., Woo, P.C.Y., Zell, R., 2020. Recommendations for the nomenclature of enteroviruses and rhinoviruses. Arch Virol. 2020 Mar;165(3):793-797. Erratum in: Arch Virol. Jun;165(6):1515. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lugo, D. , Krogstad, P., 2016. Enteroviruses in the early 21st century: new manifestations and challenges. Curr Opin Pediatr. Feb;28(1):107-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Genoni, A. , Canducci, F., Rossi, A., Broccolo, F., Chumakov, K., Bono, G., Salerno-Uriarte, J., Salvatoni, A., Pugliese, A., Toniolo, A., 2017. Revealing enterovirus infection in chronic human disorders: An integrated diagnostic approach. Sci Rep. Jul 10;7(1):5013. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nekoua, M.P. , Alidjinou, E.K., Hober, D., 2022. Persistent coxsackievirus B infection and pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 18, 503–516. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, N.M., 2022. Persistent Enterovirus Infection: Little Deletions, Long Infections. Vaccines (Basel). May 12;10(5):770. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Légeret, C. , Furlano, R., 2021. Oral ulcers in children—A clinical narrative overview. Ital J Pediatr 47, 144. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, X. , Zhang, Y., Li, H., Liu, L, 2023. Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease-Associated Enterovirus and the Development of Multivalent HFMD Vaccines. Int J Mol Sci 24, 169. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frydenberg, A. , Starr, M., 2003. Hand, foot and mouth disease. Aust Fam Physician 32, 594–595. [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, A.; Nekoua, M.P.; Mercier, A.; Vergez, I.; Sane, F.; Alidjinou, E.K.; Hober, D. Combating coxsackievirus B infections. Rev Med Virol e 2406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.S. , Garon J., Seib K., Orenstein, W.A., 2015. Polio vaccination: past, present and future. Future Microbiol. 10(5):791-808. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumakov, K. , Ehrenfeld, E., Agol, V.I, Wimmer, E., 2021. Polio eradication at the crossroads. Lancet Glob Health. Aug;9(8):e1172-e1175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.L. , Shih, S.R., Tolbert, B.S., Brewer, G., 2021. Enterovirus A71 Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). Feb 27;9(3):199. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baggen, J. , Thibaut, H.J., Strating, J.R.P.M., van Kuppeveld, F.J.M, 2018. The life cycle of non-polio enteroviruses and how to target it. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018 Jun;16(6):368-381. . Erratum in: Nat Rev Microbiol. May 3;:. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X. , Sun, D., Guo, J., Elgner, F., Wang, M., Hildt, E., Cheng, A., 2019. Multifunctionality of structural proteins in the enterovirus life cycle. Future Microbiol. Sep;14:1147-1157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, L. , Lyoo, H., van der Schaar, H.M., Strating, J.R., van Kuppeveld F.J., 2017. Direct-acting antivirals and host-targeting strategies to combat enterovirus infections. Curr Opin Virol. Jun;24:1-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laajala, M. , Reshamwala, D., Marjomäki, V., 2020. Therapeutic targets for enterovirus infections. Expert Opin Ther Targets. Aug;24(8):745-757. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammaro, C.; Guida, M.; Appetecchia, F.; Biava, M.; Consalvi, S.; Poce, G. , 2023. Direct-Acting Antivirals and Host-Targeting Approaches against Enterovirus B Infections: Recent Advances. Pharmaceuticals, 16, 203. [CrossRef]

- Tao, L. , Lemoff, A., Wang, G., Zarek, C., Lowe, A., Yan, N., Reese, T.A., 2020. Reactive oxygen species oxidize STING and suppress interferon production. Elife. Sep 4;9:e57837. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, L. , Cao, Z., Wang, Z., Guo, J., Wen, J., 2022. Reactive oxygen species associated immunoregulation post influenza virus infection. Front Immunol. Jul 29;13:927593. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, M. L, Weng, S.F., Kuo, C.H., Ho, H.Y., 2014. Enterovirus 71 induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation that is required for efficient replication. PLoS One. Nov 17;9(11):e113234. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, M.L. , Wu, C.H., Chien, K.Y., Lai, C.H., Li, G.J., Liu, Y.Y., Lin, G., Ho, H.Y., 2022. Enteroviral 2B Interacts with VDAC3 to Regulate Reactive Oxygen Species Generation That Is Essential to Viral Replication. Viruses. Aug 4;14(8):1717. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sander, W.J. , Fourie, C., Sabiu, S., O‘Neill, F.H., Pohl, C.H., O‘Neill, H.G., 2022. Reactive oxygen species as potential antiviral targets. Rev Med Virol.; 32(1):e2240. [CrossRef]

- Filardo, S. , Di Pietro, M., Mastromarino, P., Sessa, R., 2020. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol against emerging respiratory viral infections. Pharmacol Ther. Oct;214:107613. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Petrillo, A. , Orrù, G., Fais, A., Fantini, M.C., 2022. Quercetin and its derivates as antiviral potentials: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. Jan;36(1):266-278. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y. , Zhao, S., Chen, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, T., Wo, X., Dong, Y., Zhang, J., Xu, W., Qu, C., Feng, X., Wu, X., Wang, Y., Zhong, Z., Zhao, W., 2019. N-Acetyl cysteine effectively alleviates Coxsackievirus B-Induced myocarditis through suppressing viral replication and inflammatory response. Antiviral Res. 2020 Jul;179:104699. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volobueva, A.S. , Zarubaev, V.V., Fedorchenko, T.G., Lipunova, G.N., Tungusov V.N., Chupakhin,O.N., 2023. Antiviral properties of verdazyls and leucoverdazyls and their activity against group B enteroviruses. Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity, Vol. 13. - N. 1. - P. 107-118. [CrossRef]

- Fedorchenko, T.G. , Lipunova, G.N., Shchepochkin, A.V., Valova, M.S., Tsmokalyuk, A.N., Slepukhin, P.A., Chupakhin, O. N., 2020. Synthesis and Spectral, Electrochemical, and Antioxidant Properties of 2-(5-Aryl-6-R-3-phenyl-5,6-dihydro-4H-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-1-yl)-1,3-benzothiazole. Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 38–48.].

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. Manual for the virological investigation of polio, 4th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-112.

- Nix, W.A.; Oberste, M.S.; Pallansch, M.A. , 2006. Sensitive, Seminested PCR Amplification of VP1 Sequences for Direct Identification of All Enterovirus Serotypes from Original Clinical Specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol., 44, 2698–2704.

- Mosmann, T. , 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 65(1-2), 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Shetnev, A.A. , Volobueva, A.S., Panova, V.A., Zarubaev, V.V., Baykov, S.V., 2022. Design of 4-Substituted Sulfonamidobenzoic Acid De-rivatives Targeting Coxsackievirus B3. Life. 12, 1832. [CrossRef]

- Daelemans, D. , Pauwels, R., De Clercq, E., Pannecouque, C., 2011. A time-of-drug addition approach to target identification of antiviral compounds. Nat Protoc. Jun;6(6):925-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, B. , Li, Z., Xiang, F., Li, F., Zheng, Y., Wang, G., 2014. The whole genome sequence of coxsackievirus B3 MKP strain leading to myocarditis and its molecular phylogenetic analysis. Virol J. Feb 21;11:33. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okonechnikov, K. , Golosova, O., Fursov, M., 2012. UGENE team. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics. Apr 15;28(8):1166-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://web.expasy.org/translate/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Available online: http://hexserver.loria.fr/(accessed on).

- Schmidtke, M. , Hammerschmidt, E., Schüler, S., Zell, R., Birch-Hirschfeld, E., Makarov, V.A., Riabova, O.B., Wutzler, P., 2005. Susceptibility of coxsackievirus B3 laboratory strains and clinical isolates to the capsid function inhibitor pleconaril: antiviral studies with virus chimeras demonstrate the crucial role of amino acid 1092 in treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. Oct;56(4):648-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X. , Wan, Z., Li, Y. et al. National Epidemiology and Evolutionary History of Four Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease-Related Enteroviruses in China from 2008 to 2016. Virol. Sin. 35, 21–33 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhuang ZC, Kou ZQ, Bai YJ, Cong X, Wang LH, Li C, Zhao L, Yu XJ, Wang ZY, Wen HL. Epidemiological Research on Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in Mainland China. Viruses. 2015 Dec 7;7(12):6400-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andreoni AR, Colton AS. Coxsackievirus B5 associated with hand-foot-mouth disease in a healthy adult. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Mar 27;3(2):165-168. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barton DJ, Flanegan JB. Synchronous replication of poliovirus RNA: initiation of negative-strand RNA synthesis requires the guanidine-inhibited activity of protein 2C. J Virol. 1997 Nov;71(11):8482-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salmikangas, S. ., Laiho, J.E., Kalander, K., Laajala, M., Honkimaa, A., Shanina, I., Oikarinen, S., Horwitz, M.S., Hyöty, H., Marjomäki, V., 2020. Detection of Viral-RNA and +RNA strands in Enterovirus-infected cells and tissues. Microorganisms, vol. 8, no. 12: 1928. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Wang, M., Cheng, A., Wen, X., Ou, X., Mao, S., Gao, Q., Sun, D., Jia, R., Yang, Q., Wu, Y., Zhu, D., Zhao, X., Chen, S., Liu, M., Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, L., Tian, B., Pan, L., Chen, X., 2020. Enterovirus Replication Organelles and Inhibitors of Their Formation. Front Microbiol. Aug 20;11:1817. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Domanska, A. , Guryanov, S., Butcher, S.J., 2021. A comparative analysis of parechovirus protein structures with other picornaviruses. Open Biol. Jul;11(7):210008. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C. , Chathuranga, K., Lee, J.S., 2019. Intracellular sensing of viral genomes and viral evasion. Exp Mol Med. Dec 11;51(12):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Belov, G.A. , 2016. Dynamic lipid landscape of picornavirus replication organelles. Curr Opin Virol. Aug;19:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, G. , Melia, C.E., Snijder, E.J., Bárcena, M., 2020. Double-Membrane Vesicles as Platforms for Viral Replication. Trends Microbiol. Dec;28(12):1022-1033. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. , De Carli, A., Filipponi, C., Iacono, E., La Rocca, V., Lottini, G., Piazza, C.R., Quaranta, P., Sidoti, M., Pistello, M., Freer, G., 2022. Lipid balance remodelling by human positive-strand RNA viruses and the contribution of lysosomes. Antiviral Res. Oct;206:105398. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Wang, M., Cheng, A., Wen, X., Ou, X., Mao, S., Gao, Q., Sun, D., Jia, R., Yang, Q., Wu, Y., Zhu, D., Zhao, X., Chen, S., Liu, M., Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, L., Tian, B., Pan, L., Chen, X., 2020. Enterovirus Replication Organelles and Inhibitors of Their Formation. Front Microbiol. Aug 20;11:1817. [CrossRef]

- Kadare, G. , Haenni, A.L., 1997 Virus-encoded RNA helicases. J. Virol. 71, 2583–2590. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H. , Wang, K., Zhao, K., Hua, S.C., Du, J., 2020. The Structure, Function, and Mechanisms of Action of Enterovirus Non-structural Protein 2C. Front Microbiol. Dec 14;11:615965. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singleton, M.R. , Dillingham, M.S., Wigley, D.B. 2007. Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 23–50. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H. , Wang, P., Wang, G.C., Yang, J., Sun, X., Wu, W., Qiu, Y., Shu, T., Zhao, X., Yin, L., Qin, C.F., Hu, Y., Zhou, X., 2015. Human Enterovirus Nonstructural Protein 2CATPase Functions as Both an RNA Helicase and ATP-Independent RNA Chaperone. PLoS Pathog. Jul 28;11(7):e1005067. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. , Li, Z., Cui, S., 2021. Picornaviral 2C proteins: A unique ATPase family critical in virus replication. Enzymes.;49:235-264. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. , Wojdyla, J.A., Colasanti, O., Li, Z., Qin, B., Wang, M., Lohmann, V., Cui, S., 2022. Biochemical and structural characterization of hepatitis A virus 2C reveals an unusual ribonuclease activity on single-stranded RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. Sep 9;50(16):9470-9489. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. , Zheng, Z., Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Liu, Q., Meng, J., Ke, X., Hu, Q., Wang, H., 2016. 2C Proteins of Enteroviruses Suppress IKKβ Phosphorylation by Recruiting Protein Phosphatase 1. J Virol. Apr 29;90(10):5141-5151. [CrossRef]

- Du, H. , Yin, P., Yang, X., Zhang, L., Jin, Q., Zhu, G., 2015. Enterovirus 71 2c Protein Inhibits NF-KappaB Activation by Binding to RelA(P65). Sci Rep 5:14302. [CrossRef]

- Li, L. , Fan, H., Song, Z., Liu, X., Bai, J., Jiang, P., 2019. Encephalomyocarditis Virus 2C Protein Antagonizes Interferon-Beta Signaling Pathway Through InteractionWithMDA5. Antiviral Res 161:70–84. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. , Ning, S., Su, X., Liu, X., Wang, H., Liu, Y., Zheng, W., Zheng, B., Yu, X.F., Zhang, W., 2018. Enterovirus 71 antagonizes the inhibition of the host intrinsic antiviral factor A3G. Nucleic Acids Res. Nov 30;46(21):11514-11527. [CrossRef]

- Guan, H. , Tian, J., Qin, B., Wojdyla, J.A., Wang, B., Zhao, Z., Wang, M., Cui, S., 2017. Crystal structure of 2C helicase from enterovirus 71. Sci Adv. Apr 28;3(4):e1602573. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guan, H. , Tian, J., Zhang, C., Qin, B., Cui, S., 2018. Crystal structure of a soluble fragment of poliovirus 2CATPase. PLoS Pathog. Sep 19;14(9):e1007304. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hurdiss, D.L. , El Kazzi, P., Bauer, L., Papageorgiou, N., Ferron, F.P., Donselaar, T., van Vliet, A.L.W., Shamorkina, T.M., Snijder, J., Canard, B., Decroly, E., Brancale, A., Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, T., Förster, F., van Kuppeveld, F.J.M., Coutard, B., 2022. Fluoxetine targets an allosteric site in the enterovirus 2C AAA+ ATPase and stabilizes a ring-shaped hexameric complex. Sci Adv. Jan 7;8(1):eabj7615. [CrossRef]

- Adams, P. , Kandiah, E., Effantin, G., Steven, A.C., Ehrenfeld, E., 2009. Poliovirus 2C protein forms homo-oligomeric structures required for ATPase activity. J Biol Chem. Aug 14;284(33):22012-22021. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sweeney, T.R. , Cisnetto, V., Bose, D., Bailey, M., Wilson, J.R., Zhang, X., Belsham, G.J., Curry, S., 2010. Foot-and-mouth disease virus 2C is a hexameric AAA+ protein with a coordinated ATP hydrolysis mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 6;285(32):24347-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Papageorgiou, N. , Coutard, B., Lantez, V., Gautron, E., Chauvet, O., Baronti, C., Norder, H., de Lamballerie, X., Heresanu, V., Ferté, N., Veesler, S., Gorbalenya, A.E., Canard, B., 2010. The 2C putative helicase of echovirus 30 adopts a hexameric ring-shaped structure. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010 Oct;66(Pt 10):1116-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, M. , Hadaschik, D., Zimmermann, H., Eggers, H.J., Nelsen-Salz, B., 2000. The picornavirus replication inhibitors HBB and guanidine in the echovirus-9 system: the significance of viral protein 2C. J Gen Virol.Apr;81(Pt 4):895-901. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, A.M. , Heggermont, W., Lanke, K., Coutard, B., Bergmann, M., Monforte, A.M., Canard, B., De Clercq, E., Chimirri, A., Pürstinger, G., Rohayem, J., van Kuppeveld, F., Neyts, J., 2008. The thiazolobenzimidazole TBZE-029 inhibits enterovirus replication by targeting a short region immediately downstream from motif C in the nonstructural protein 2C. J Virol. May;82(10):4720-30. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H. , Agoh, M., Agoh, Y., Yoshida, H., Yoshii, K., Yoneyama, T., Hagiwara, A., Miyamura, T., 2000. Mutations in the 2C region of poliovirus responsible for altered sensitivity to benzimidazole derivatives. J Virol. May;74(9):4146-54. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.K. , Panda, S., Sahu, B.P., Sarangi, R., 2022. Activation of Host Cellular Signaling and Mechanism of Enterovirus 71 Viral Proteins Associated with Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease. Viruses. Oct 4;14(10):2190. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.F. , Yang, S.Y., Wu, B.W., Jheng, J.R., Chen, Y.L., Shih, C.H., Lin, K.H., Lai, H.C., Tang, P., Horng, J.T., 2007. Reticulon 3 binds the 2C protein of enterovirus 71 and is required for viral replication. J Biol Chem. Feb 23;282(8):5888-98. [CrossRef]

- Laufman, O. , Perrino, J., Andino, R., 2019. Viral Generated Inter-Organelle Contacts Redirect Lipid Flux for Genome Replication. Cell. Jul 11;178(2):275-289.e16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Compound number | CC50, µM a | IC50 µM b | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1а | 619.9±52.7 | 1.8±0.3 | >230 |

| 1b | >1347 | 5.4±1.1 | >250 |

| 1c | 320.9±28.2 | 7.4±2.2 | 43 |

| 1d | 886.4±90.4 | 6.2±1.9 | 142 |

| 2a | >324.7 | 6.49±0.8 | >50 |

| 2b | 2048.2±198.5 | 24.1±3.2 | 85 |

| 2c | >302.7 | >121.1 | >2 |

| 2d | 49.6±3.7 | >49.6 | <1 |

| 2e | 69.1±5.9 | >69.1 | <1 |

| 2f | >301.2 | 12.1±1.9 | >25 |

| 3a | >313.3 | >125.3 | >2 |

| 3b | 2331.1±25.3 | 60.1±7.2 | >38 |

| 3c | 359.7±41.7 | 71.9±6.4 | 5 |

| 3d | 2309.5±19.7 | >231.0 | >10 |

| 3e | 945.5±89.6 | >209.6 | >4 |

| 4a | >314.8 | >125.9 | >2 |

| 4b | >292.7 | >117.1 | >2 |

| 4c | >290.7 | 27.9±3.3 | 10 |

| 4d | 1529.6±17.2 | 51.6±6.4 | 29 |

| Virus | CC50, µM a | IC50 µM b | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 1a | |||

| CVA16 | 673.3±60.1 | 0.8±0.2 | 841 |

| CVB5 | 619.9±52.7 | 1.5±0.3 | 413 |

| ECHO30 | 673.3±60.1 | 1.6±0.4 | 420 |

| CVA24 | 673.3±60.1 | 0.9±0.3 | 747 |

| CVB4 (strain Powers) | 619.9±52.7 | 1.7 ±0.5 | 364 |

| Guanidine hydrochloride | |||

| CVA16 | >10471.2 | 336.8±28.3 | >31 |

| CVB5 | >5235.6 | 473.7±33.4 | >10 |

| ECHO30 | >10471.2 | 125.6±18.2 | >83 |

| CVA24 | >10471.2 | 314.2±20.1 | >33 |

| CVB4 (strain Powers) | >5235.6 | 495.7±26.5 | >10 |

| Virus | CC50, µM a | IC50 µM b | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 | 850.2±78.3 | 38.7±2.9 | 22 |

| Influenza B/Florida/04/0 6 | 850.2±78.1 | 40.5±5.1 | 21 |

| HSV1 | 450.7±51.2 | 46.3±4.4 | 10 |

| Ad5 | 500.6±45.7 | 43.1±3.8 | 12 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 656.3±70.4 | 4.5±1.2 | 146 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).