1. Introduction

High-elastic yarns are a key raw material for the production of compression garments that can provide stability, compression, and support to the human body [

1]. Such compression garments have been widely used in the medical, sports, and aerospace fields in the form of compression stockings, orthopedic supports, and functional sportswear [

2,

3,

4], which is safe and has no side effects compared to surgery and drug therapy [

5]. In particular, compression garments are worn to apply pressure to the skin and deep soft tissues, thereby narrowing the width of veins and promoting the reabsorption of lymphatic fluid [

6,

7]. As the key component of high-performance compression garments, elastic yarns with good extensibility and elastic recovery allow garments to become effective stretching elements acting on the curved body, exerting desired pressure on the surface of the needed body zone [

8].

Spandex elastic yarns usually have an elongation of 400%-800%, but their elastic modulus is only 0.2-1.1 cN/tex [

9], making it difficult to control tension during knitting, frequently resulting in fabric horizontal strips, uneven elasticity, and yarn breakage [

10]. Therefore, Spandex is usually combined with other types of fibers to make composite yarns before weaving. Core-spun yarn and wrapped yarn are the most commonly used elastic composite yarns [

11]. Notably, high-force fibers can increase the tenacity of elastic fibers by more than 10 times,[

12] which improves the yarn processability [

13]. For example, Nylon/Spandex [

14] and cotton/Spandex [

15]core-spun yarns usually have a force of 588.12 cN and 1005.25 cN, respectively, which can provide sufficiently high pressure. However, their elongation was in the range of 10%-30%, which could not accommodate the wide range of body sizes and would restrict body movement.

Wrapped yarns have an untwisted core with a distinct core-to-sheath relationship, so the wrapped and core material cannot restrict each other's elongation. Wrapping materials are usually selected from high-force filaments such as polyester [

16] and nylon [

17]. For example, the tensile elongation of nylon/Spandex-wrapped yarns can be up to 605%, but the tensile force is only 239 cN [

17]. Therefore, the force needs to be improved for use in high-compression garments, which require to generate pressures above 20 mmHg [

8]. In addition, compression garments need to be used more than 50 times and are susceptible to pressure mismatch and relaxation fatigue [

18,

19,

20]. For example, plating rib knitted fabric with Spandex and cotton has a pressure reduction of more than 3.2% when stretched five times [

21]. Even worse, the elastic recovery of single-knitted fabrics prepared from core-spun yarn was only 60.06% at 50% stretch [

22]. To this end, it remains a challenge to fabricate anti-fatigue yarns with high mechanical force and long elongation for generating compression garments with prolonged wear.

In this study, we report the development of anti-fatigue double-wrapped yarns with excellent mechanical properties by wrapping high-denier Spandex with nylon filaments in opposite twists. By systematically optimizing manufacturing parameters including inner wrapping density, outer wrapping density, taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio, we obtained double-wrapped yarn with excellent tensile force (952.00 ± 24.03 cN) and elongation (357.28% ± 9.10%). Notably, the stress decay rate of optimized yarns was only 12.0% ± 2.2%. In addition, the optimized yarn was used as the weft-lining yarn for generating weft-lined fabrics, the elastic recovery rate of the obtained fabric was only 2.6% after cyclic stretching, much lower than the control fabric. We believe that the anti-fatigue double-wrapped yarns could be widely used for fabricating high-performance compression garments.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Design of Double-Wrapped Yarns and Weft-Lined Knitted Fabric

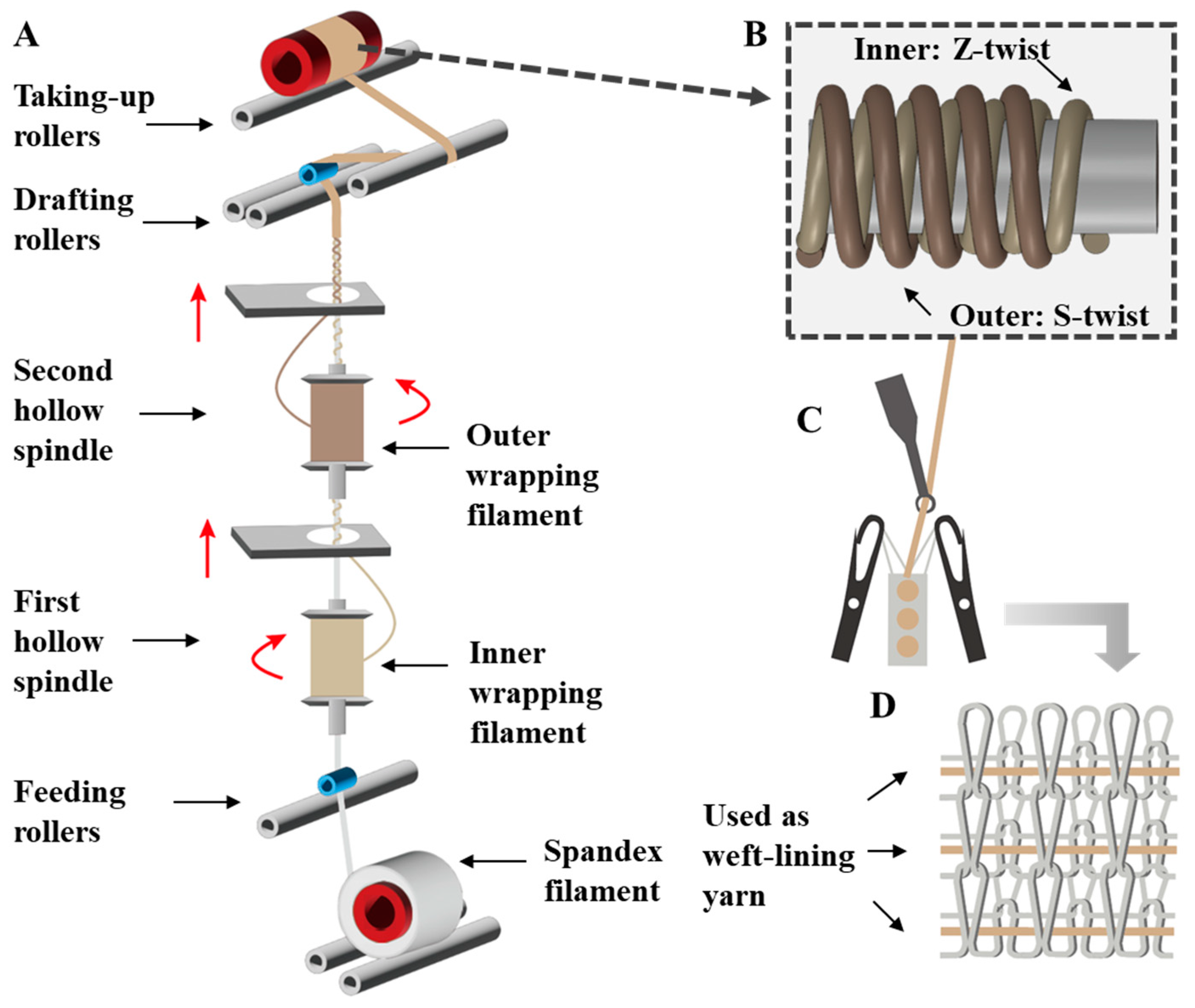

We designed double-wrapped yarns with an untwisted core of Spandex and double-wrapped nylon filaments in opposite twists for generating compression fabrics (

Figure 1). In particular, 560D high-denier Spandex as the core was untwisted which can maximumly reduce the interaction between the core and wrapping filaments, enabling high elongation of the double-wrapped yarns. In addition, we chose 70D nylon filaments with a tensile force of 387.40 ± 8.82 cN as the wrapping materials to provide sufficient force for double-wrapped yarns. Notably, opposite twists were induced for the inner and outer wrapping filaments to achieve a balanced stable yarn structure. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the interfaces formed by the core filament, inner wrapping filaments, and outer wrapping filaments would synergistically affect yarn mechanical properties. Specifically, we believed that there would be an appropriate wrapping angle (the angle between the wrapping filament and the axis of the yarn) and wrapping density to enable double-wrapped yarns with high mechanical force and large elongation simultaneously. In particular, the yarn structure is determined by a combination of manufacturing parameters such as inner wrapping density, outer wrapping density, taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio.

During the fabrication, the Spandex filament was placed at the bottom of the machine and sequentially passed through the feeding rollers, the holes of the first and the second hollow spindles. Specifically, a Z-twist was generated for the inner-wrapped nylon filaments by the first clockwise rotating hollow spindle, while an S-twist was generated for the outer-wrapped nylon filaments by the second anti-clockwise rotating hollow spindle. Finally, the double-wrapped yarns were formed after passing through the drafting rollers and winded by the taking-up rollers (

Figure 1A,B). It should be noted that the drafting ratio was controlled by the speed ratio of drafting rollers and feeding rollers, while the taking-up ratio was controlled by the speed ratio of taking-up rollers and drafting rollers. To obtain double-wrapped yarns with excellent mechanical properties, we systematically explored the influence of inner wrapping density, outer wrapping density, taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio on the structure and mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns, we also further investigated the performance of double-wrapped yarns as weft-lining yarns for generating compression fabrics using computerized flat knitting machines (

Figure 1C,D).

2.2. Effect of the Inner and Outer Wrapping Density on the Mechanical Properties of Double-Wrapped Yarns

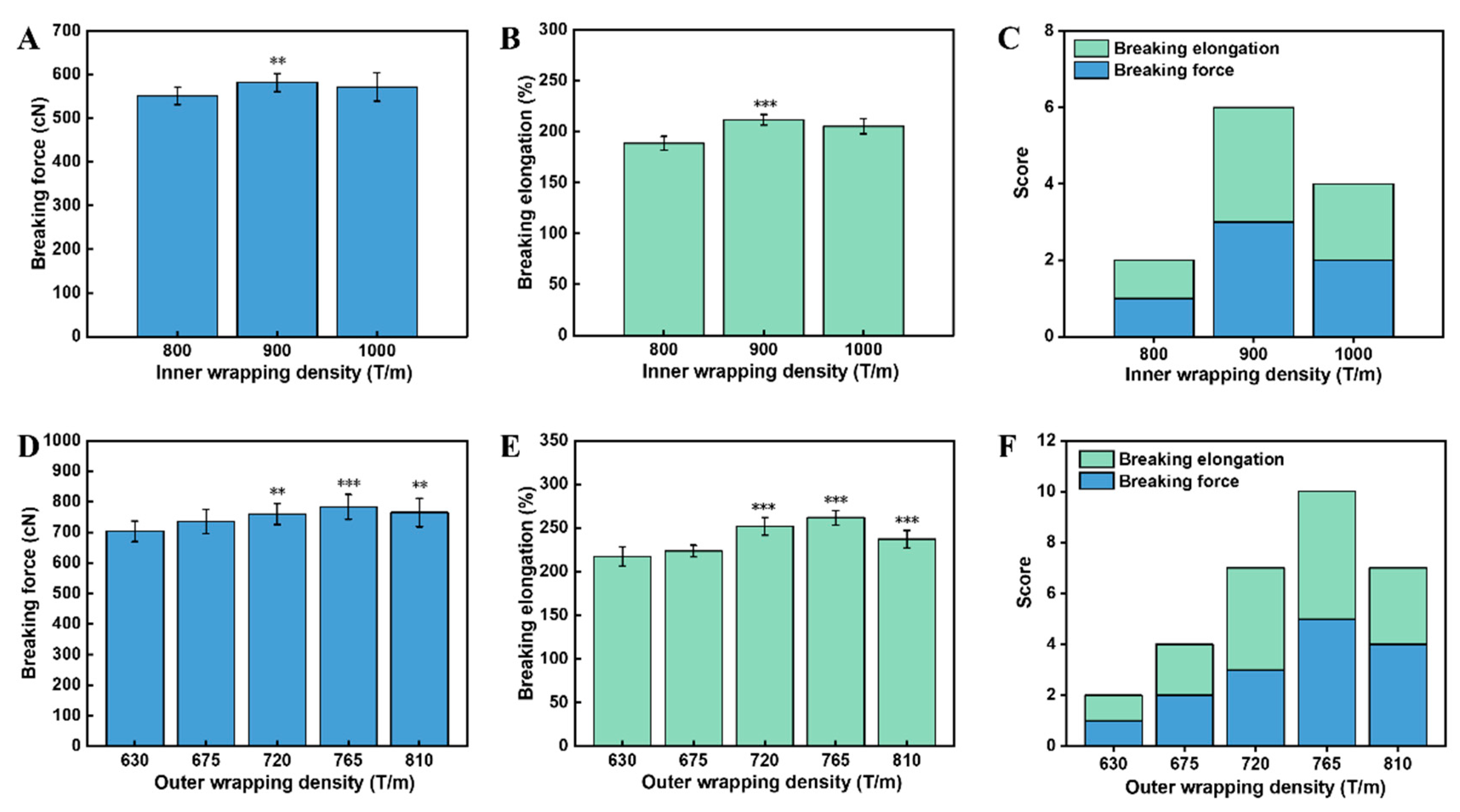

Initially, we investigate the effect of the inner wrapping density on the mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns. Specifically, the inner wrapping density was varied from 800 T/m to 1000 T/m. While the outer wrapping density, taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio were fixed at 675 T/m, 0.5, and 3.2, respectively. As the mechanical properties of yarns determine the ability of garments to resist damage from external forces, the breaking force and elongation of yarns were quantified according to stress-strain curves. Notably, the inner wrapping density had a significant effect on the breaking force (F=3.479, P=0.047). It can be seen that there is no significant difference in yarn force between 900 T/m and 1000 T/m, but both are higher than 800 T/m (

Figure 2A). We believe that the tensile strength is simultaneously determined by the tensile strength of the Spandex core, the friction along the axis of double-wrapped yarns, and the component force of wrapped filaments along the double-wrapped yarn axis. When the inner wrapping density was increased, the wrapping angle was elevated, resulting in less component force of wrapped filaments along the double-wrapped yarn axis. In contrast, higher inner wrapping density also led to large pressure between the Spandex core and wrapped filaments, generating larger frictions along the axis of double-wrapped yarns together due to the increased number of inner wrapping filaments per length of double-wrapped yarns [

14]. Therefore, the maximum yarn force obtained at 900 T/m inner wrapping density should be attributed to the synergetic effect of frictions and component force of wrapped filaments along the double-wrapped yarn axis.

Notably, the inner wrapping density also had a significant effect on the elongation (F=29.249, P<0.001). Specifically, the elongation was 211.57% ± 5.16% and 205.40% ± 7.56% when the inner wrapping density was 900 T/m and 1000 T/m, respectively, both higher than 800 T/m (

Figure 2B). The larger elongation under higher inner wrapping density should be attributed to the enhanced wrapping angle, making wrapped filaments easier to deform along the axis of double-wrapped yarns [

23]. However, two large frictions between the Spandex core and wrapped filaments generated under high wrapping density may also prevent the double-wrapped yarns from deformation. To obtain optimized conditions, we further chose the queueing scoring rule to evaluate the overall performance. Specifically, high tensile force and larger elongation were targeted for each parameter combination score. As a result, we found that 900 T/m was the best processing parameter for achieving the highest score of 6 points (

Figure 2C).

In the exploration of the outer wrapped filaments, the outer wrapping density ranged from 630 T/m to 810 T/m, while the inner wrapping density, taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio were fixed at 900 T/m, 0.7, and 4.8, respectively. Similarly, the outer wrapping density also had a significant effect on the breaking force (F=5.516, p=0.001). Specifically, the highest breaking force (783.56 ± 40.78 cN) was obtained when the outer wrapping density was 765 T/m (

Figure 2D). The outer wrapping density had a significant effect on the elongation (F=3.515, p=0.015). Maximum elongation of 261.81% ± 8.26% was obtained when the outer wrapping density was 765 T/m (

Figure 2E). Notably, the elongation of yarns obtained at 765 T/m was more than 20% higher than that of 675 T/m. In addition, the queueing scoring rule showed that 765 T/m at 10 points was the best combination of process parameters (

Figure 2F). It should be noted that the highest breaking force and elongation obtained 765 T/m outer wrapping density could be explained by the same principles as inner wrapping density.

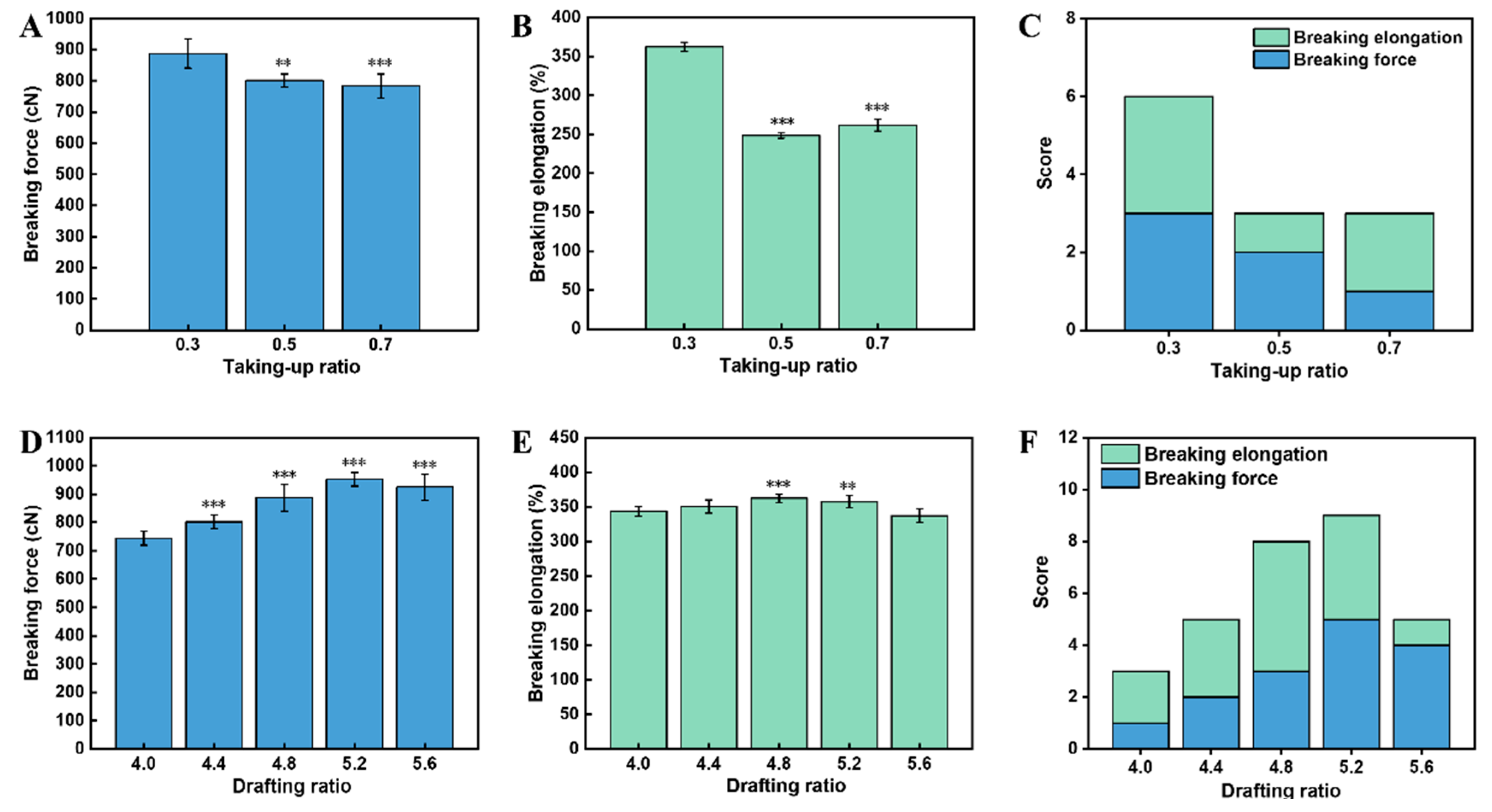

2.3. Effect of the Taking-Up and Drafting Ratios on Mechanical Properties of Double-Wrapped Yarns

The taking-up ratio affects the storage tension of the yarn, which is usually wound with slack. We, therefore, explored the effect of the taking-up ratio ranging from 0.3 to 0.7 on the mechanical properties of the yarns, while maintaining the drafting ratio, inner and outer wrapping density constant at 4.8, 900 T/m, and 765 T/m. After statistically evaluating the mechanical properties, we found that the taking-up ratio had a significant effect on the breaking force (F=14.502, P<0.001), and elongation (F=611.143, P<0.001). Specifically, the breaking force was the highest (887.44 ± 46.43 cN) when the taking-up ratio was 0.3 (

Figure 3A). In addition, the elongation of yarns obtained at 0.3 taking-up ratio was 45.8% and 38.3% higher than that of 0.5 (P<0.001) and 0.7 (P<0.001) (

Figure 3B). The queueing scoring rule indicated that 0.3 was the best combination of process parameters (

Figure 3C). We believe that a larger taking-up ratio resulted in non-recoverable plastic deformation of the Spandex core after storage in the slack, which would weaken the mechanical properties of the Spandex core [

24]. Due to plastic deformation, the double-wrapped yarns would become less extensible, thus resulting in less elongation.

We next investigated the influence of the drafting ratio on the mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns. Specifically, the drafting ratio ranged from 4.0 to 5.6, while inner and outer wrapping density, and taking-up ratio were kept constant at 900 T/m, 765 T/m, and 0.3. Results indicated that the drafting ratio also had a significant effect on the breaking force (F=38.405, P<0.001) and elongation (F=12.827, P<0.001). The highest breaking force up to 952.00 ± 24.03 cN was obtained when the drafting ratio was 5.2, while the elongation was 357.28% ± 9.10% (

Figure 3D). Meanwhile, the highest elongation was 362.14% ± 5.93% when the drafting ratio was 4.8 (

Figure 3E), while the breaking force was 887.44 ± 46.43 cN. The queueing scoring rule showed that 5.2 was the best combination of process parameters (

Figure 3F). Notably, a higher drafting ratio would lead to a larger retraction of double-wrapped yarns, indirectly elevating the wrapping density for both inner and outer wrapping filaments, therefore generating yarns with better mechanical properties at a relatively higher drafting ratio. The decreased tensile strength and elongation at the highest drafting ratio of 5.6 should be also ascribed to the synergetic effect of frictions and component force of wrapped filaments along the double-wrapped yarn axis.

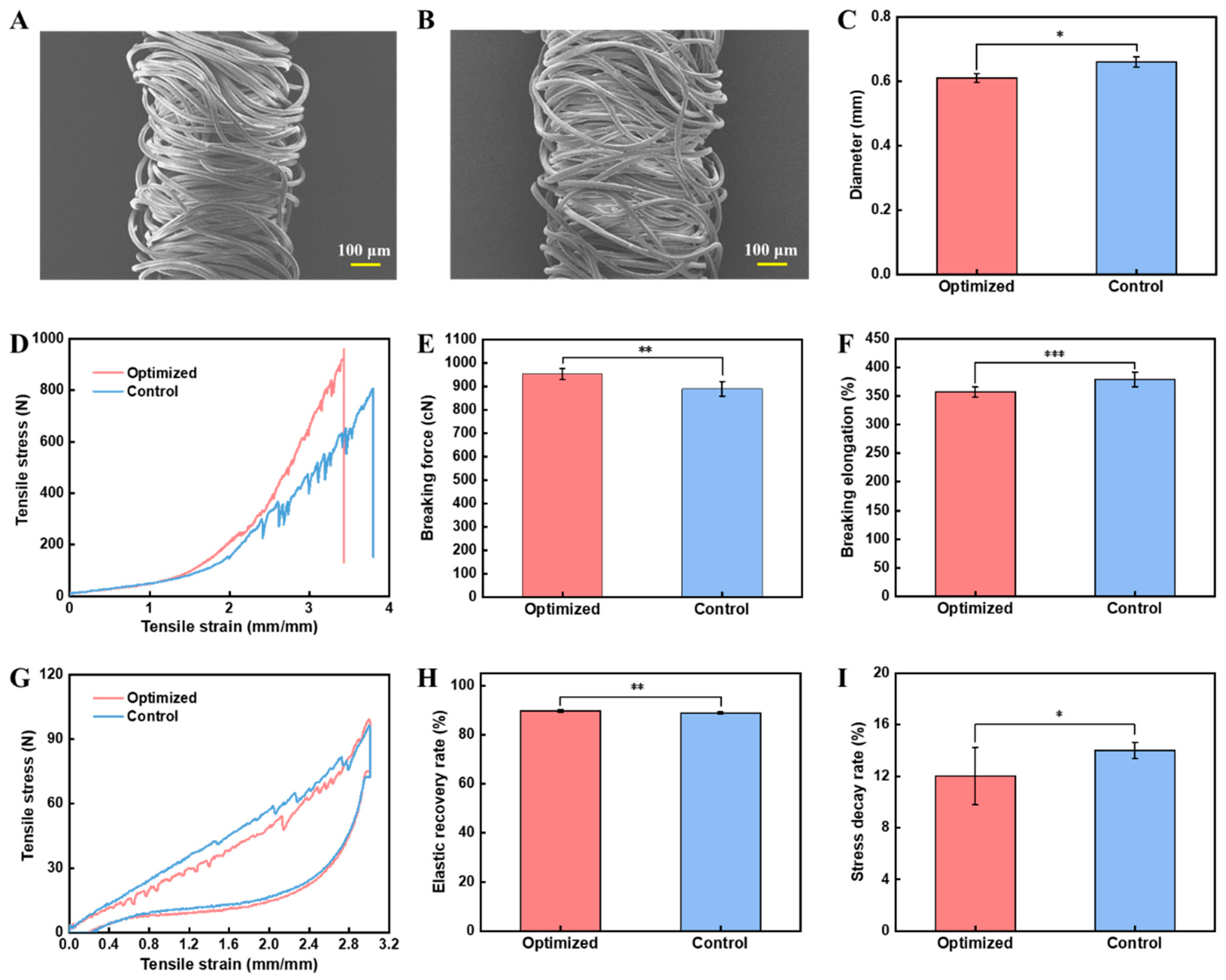

2.4. Comparison of Yarn Mechanical Properties and Knitted Fabrics

To further evaluate the performance of the optimized double-wrapped yarn obtained at inner and outer wrapping density, the taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio of 900 T/m, 765 T/m, 0.3, and 5.2, respectively, a commercially available wrapped yarn with a similar diameter was employed as a control for comparison (

Figure 4A–C). Notably, the wrapping density of the control yarn is relatively low as we can see part of the Spandex core. In contrast, the optimized yarn has a uniform distribution of wrapping filaments and the yarn structure is in excellent equilibrium, which is particularly suitable for use as the weft-lining yarn of weft-lined knitted fabrics.

To compare their mechanical properties, we evaluated the tensile force, elongation, elastic recovery rate, and stress decay rate. Specifically, the optimized yarns exhibited higher tensile force (P<0.001) and a bit smaller elongation (P<0.001) (

Figure 4D–F). Notably, the tensile force of the optimized yarn was 62 cN higher than the control yarn, which should be due to a more homogeneous and dense structure of the wrapping shealth. Importantly, the optimized yarns exhibited a higher elastic recovery rate (p<0.01) and a much lower stress decay rate (p<0.05) (

Figure 4G–I). Specifically, the stress decay rate of optimized yarns was 12.0% ± 2.2%, while the stress decay rate of control yarn was 14.0% ± 0.6%, indicating that the optimized yarn has a more stable structure that can be used for generating compression fabrics to generate consecutive force.

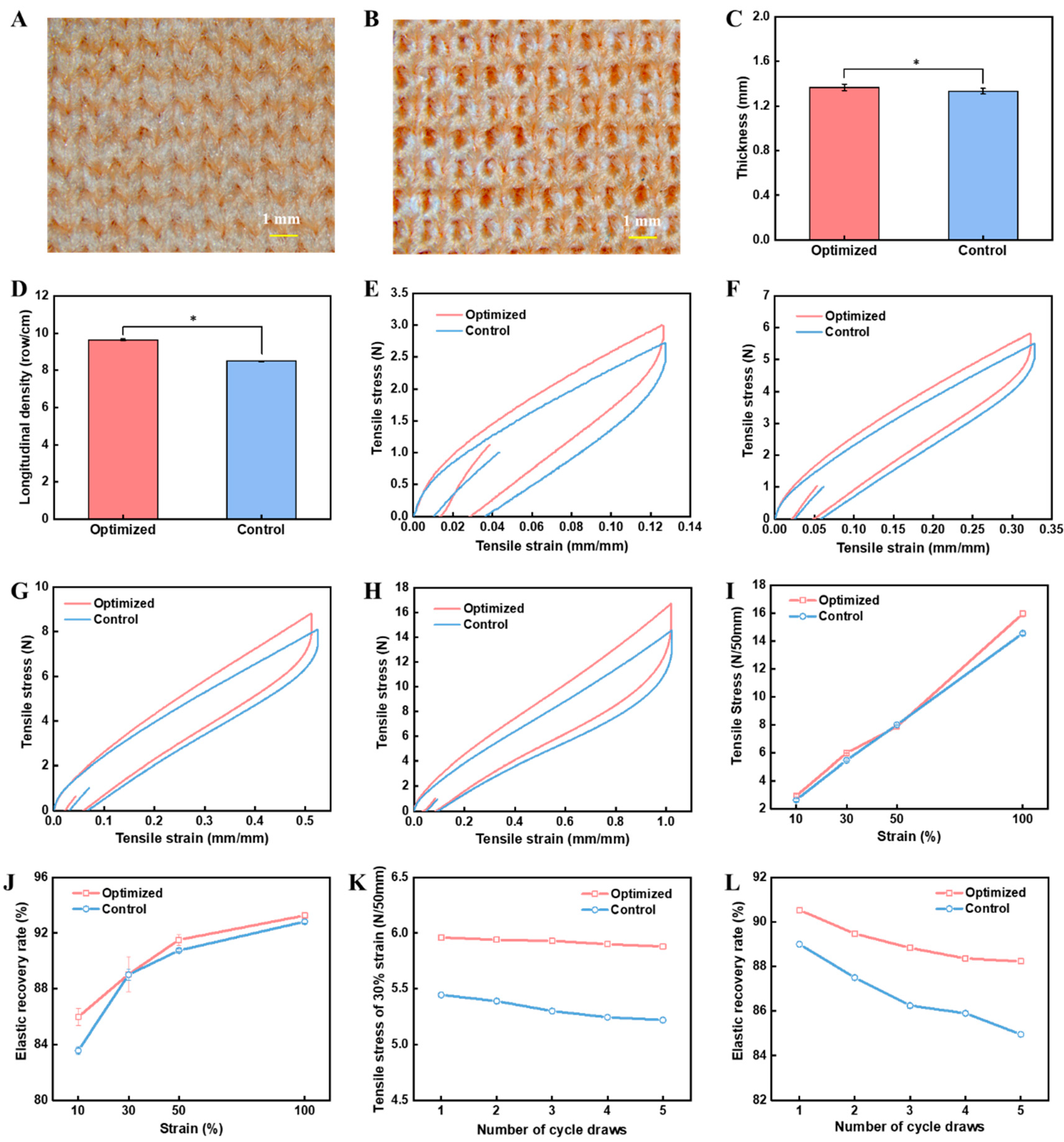

To verify the performance of compression fabrics fabricated with the optimized yarn, both optimized and control yarns were used as the weft-lining yarn for generating weft-lined fabrics using computerized flat knitting machines. Notably, both fabrics have good flatness with similar thicknesses (

Figure 5A–C). In addition, the weft-lining yarns can be completely hidden. Notably, the optimized yarn resulted in a knitted fabric with a higher longitudinal density than those made from control yarn (

Figure 5D). Specifically, Knitted fabrics made from optimized had an average of 1.15 more transverse rows per centimeter than those made from control yarns. It should be noted that the weft-lining yarns were under the same tension during the knitting process, therefore, the optimized weft-lining yarn would have less deformation according to the stress-strain cure and lead to less shrinkage in the weft direction (

Figure 4D).

Furthermore, the tensile force and elastic recovery rate of knitted fabrics along the weft direction were compared. Specifically, different strains ranging from 10% to 100% were investigated (

Figure 5E–H). In general, the optimized yarns maintained higher tensile force and elastic recovery at different strains investigated (

Figure 5I,J). To simulate practical conditions, we explored the changes in mechanical properties of fabrics under 30% cyclic stretching (

Figure 5K,L). After 5 cyclic stretching, the force and elastic recovery rate of the control fabric decreased by 4.1% and 4.5%, respectively, while the optimized fabric only decreased by 1.3% and 2.6%, suggesting that the optimized double-wrapped yarn could be used to fabricate weft-lined fabrics with improved anti-fatigue properties.

3. Conclusions

In this paper, anti-fatigue double-wrapped yarns with an untwisted core of Spandex and double-wrapped nylon filaments in opposite twists were developed to generate compression fabrics with excellent anti-fatigue performance. Results showed that tensile force and elongation were significantly dependent on the processing parameters of inner and outer wrapping density, taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio. Yarns with tensile force (952.00 ± 24.03 cN) and elongation (357.28% ± 9.10%) were obtained when inner and outer wrapping density, the taking-up ratio, and drafting ratio of 900 T/m, 765 T/m, 0.3, and 5.2, respectively. Notably, the stress decay rate of optimized yarns was only 12.0% ± 2.2%. Furthermore, the optimized yarn was used as the weft-lining yarn for generating weft-lined fabrics, the elastic recovery rate of the obtained fabric was only 2.6% after cyclic stretching, much lower than the control fabric. Our design of double-wrapped yarns could inspire fabricating compression garments with excellent anti-fatigue properties.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Spandex filament was purchased from Haining Kaiwei Textile Co. Nylon filament was purchased from Huizhou Xinrongchang Yarn Co. Their characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

4.2. Fabrication of Double-Wrapped Yarns

The HKV141A(Ⅱ) wrapped yarn machinery (Zhejiang Jinggong Co., Ltd., China) was used to fabricate double-wrapped yarns (

Figure 1A). The wrapping process could be divided into three parts: yarn core feeding, stretch wrapping, and loose winding. During the fabrication process, the Spandex filament was threaded into the cores of the two hollow spindles through the feeding rollers. The Z-twist and S-twist of nylon filaments were generated by the first and second hollow spindles, forming the inner and outer wrapping materials. Finally, the yarn was wound by taking-up rollers. It should be noted that the wrapping density was controlled by the rotating speed of hollow spindles and the speed of drafting rollers, the drafting ratio was controlled by the speed ratio of drafting rollers and feeding rollers, while the taking-up ratio was controlled by the speed ratio of taking-up rollers and drafting rollers. It was wrapped twice at a certain drafting ratio and output from the top drafting rollers. Each manufacturing parameter is defined below:

4.3. Fabrication of Weft-Lined Knitted Fabrics

Both optimized and control yarns were used as the weft-lining yarn for generating weft-lined fabrics using computerized flat knitting machines (Stoll ADF 530-32W). 140D nylon untwisted filaments (48f) and double-wrapped yarn were used as the face yarn and plating yarn. The double-wrapped yarn was made from 40D Spandex as the core and 70D nylon filaments (48f) as the double-wrapping materials to ensure that the ground fabric is elastic. A row of flat stitches was also added to the back of the fabric to improve the tightness. During the knitting process, the feed tension of the wrapped yarns was set to 8 cN.

4.4. Characterizations

To acquire accurate testing results, all the warp yarn and fabric samples were conditioned for 24 hours at 20℃ ± 2℃ and 65% ± 4% relative humidity following the ISO 139 standard. The yarn and fabric structures were examined with a DXS-10ACKT scanning electron microscope (Tianjin Electron Optics, China). Following the standards of FZ/T 50006-2013 and GB/T 3916-2013, the tensile properties of yarns were measured using the YG061F Electronic Single Yarn Force Tester (Laizhou Electron Instrument, China), the breaking force and breaking elongation was quantified according to obtained stress-strain curves. Each yarn sample was tested under a gauge length of 100 mm and a prestressing value of 10 cN with a speed of 500 mm/min. Each group was tested 10 times.

The elastic recovery rate and stress decay rate of double-wrapped yarns were measured using the YG061FQ Electronic Tensile Tester (Laizhou Electron Instrument, China) through a constant elongation test following the FZ/T 50007-2012 standard. Each yarn sample was stretched to 150 mm under a gauge length of 50 mm and a prestressing value of 30 cN with a speed of 500 mm/min. During the test, each sample was paused at 300% elongation and starting position for 10 s. Each group was tested 10 times.

The force and elastic recovery rate of knitted fabrics were tested using YG(B) 026G-500 Multi-functional Force Tester (Wenzhou Darong Textile Instrument Co., Ltd., China) following the FZ/T 70006-2004 standard. The sample was trimmed to a size of 200 mm × 50 mm and tested under a gauge length of 100 mm and a prestressing value of 1 cN with a stretching speed of 100 mm/min and recovering speed of 10 mm/min. During the test, each sample was paused at the designed elongation (i.e., 10%, 30%, 50%, 100%) and starting position for 30 s, this process was repeated 5 times. Each group was tested 10 times.

4.5. Queueing Scoring Rule

The score range for each mechanical property is determined by the number of parameter levels. For example, the score range of inner wrapping density and taking-up ratio is 1-3 points, and the score range of outer wrapping density and drafting ratio is 1-5 points. Each level is assigned a score according to the value of mechanical properties, such as tensile force and breaking elongation. Finally, the sum of the scores for each level is calculated and the level with the highest score is taken as the optimal parameter.

4.6. Statistical Evaluation

The statistical evaluation of the experimental results was performed on SPSS 26.0 statistical software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to investigate the differences between the levels of parameters. Multiple-comparison least significant difference (LSD) tests were used to compare the means of performance based on the significance level (Sig.). The difference in performance between the optimized yarns and the commercial yarns was analyzed using a paired t-test. All the analyses were performed at the significance level of α = 0.05.

4.7. Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32271422, 32311530766), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. 23J21901400), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Graduate Student Innovation Fund of Donghua University (grant number: CUSF-DH-T-2023011), Program for Innovative Research Team (in Science and Technology) in University of Henan Province (IRTSTHN, No. 24IRTSTHN020), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No.20DZ2254900).

References

- Pérez-Soriano, P.; García-Roig, Á.; Sanchis-Sanchis, R.; Aparicio, I. Influence of compression sportswear on recovery and performance: A systematic review. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2018, 48, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockson, S.G.; Keeley, V.; Kilbreath, S.; Szuba, A.; Towers, A. Cancer-associated secondary lymphoedema. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2019, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attias, J.; Philip, A.T.C.; Waldie, J.; Russomano, T.; Simon, N.E.; David, A.G. The Gravity-Loading countermeasure Skinsuit (GLCS) and its effect upon aerobic exercise performance. Acta Astronautica 2017, 132, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, F.; Gissane, C.; Howatson, G.; van Someren, K.; Pedlar, C.; Hill, J. Compression Garments and Recovery from Exercise: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine 2017, 47, 2245–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankariya, N. Material, structure, and design of textile-based compression devices for managing chronic edema. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2022, 52, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; Broatch, J.; O’Riordan, S.; Morrison, M.; Maniar, N.; Halson, S.L. Putting the Squeeze on Compression Garments: Current Evidence and Recommendations for Future Research: A Systematic Scoping Review. Sports Medicine 2022, 52, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Liu, R.; Ying, M.T.C.; Liang, F.; Shi, Y. Characterizing the biomechanical transmission effects of elastic compression stockings on lower limb tissues by using 3D finite element modelling. Materials & Design 2023, 232, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tao, X. Compression Garments for Medical Therapy and Sports. Polymers 2018, 10, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lu, J.; Zhu, Y. New Developments in Elastic Fibers. Polymer Reviews 2008, 48, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Jin, J.; Yan, Y.; Tao, J. Study on the tensile modulus of seamless fabric and tight compression finite element modeling. Textile Research Journal 2019, 90, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Maity, S.; Sinha, S.K. Elastic Recovery and Performance of Denim Fabric Prepared by Cotton/Lycra Core Spun Yarns. Journal of Natural Fibers 2020, 17, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhouib, A.B.; El-Ghezal, S.; Cheikhrouhou, M. A study of the impact of elastane ratio on mechanical properties of cotton wrapped elastane-core spun yarns. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2006, 97, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.; Chand, S.; Yakopson, S. Thermal properties of elastic fibers. Thermochimica Acta 2001, 367-368, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-H.; Chang, C.-W.; Lou, C.-W.; Hsing, W.-H. Mechanical Properties of Highly Elastic Complex Yarns with Spandex Made by a Novel Rotor Twister. Textile Research Journal 2004, 74, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helali, H.; Babay, A.D.; Msahli, S. Effect of elastane draft on the rheological modelling of elastane core spun yarn. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2012, 103, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.W.; Hu, J.-J.; Lu, P.C.; Lin, J.-H. Effect of twist coefficient and thermal treatment temperature on elasticity and tensile strength of wrapped yarns. Textile Research Journal 2015, 86, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.M.; Ou, Y.; Xu, N.; Yan, Y.X. Pressure Analysis on Medical Compression Hosiery and Property Research of Lycra/Nylon Double Wrapped Yarn. Advanced Materials Research 2013, 821-822, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L.; Miller, C.; McGuiness, W. Approaches to the application and removal of compression therapy: A literature review. British Journal of Community Nursing 2017, 22, S6–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hageman, D.J.; Wu, S.; Kilbreath, S.; Rockson, S.G.; Wang, C.; Knothe Tate, M.L. Biotechnologies toward Mitigating, Curing, and Ultimately Preventing Edema through Compression Therapy. Trends in Biotechnology 2018, 36, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, N.; Copley, J.; Aplin, T.; Strong, J. How to improve compression garment wear after burns: Patient and therapist perspectives. Burns 2019, 45, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y. Experimental investigation the dynamic pressure attenuation of elastic fabric for compression garment. Textile Research Journal 2013, 84, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, M.; Anbumani, N. Dynamics of Elastic Knitted Fabrics for Sports Wear. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2010, 41, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-H.; He, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Lou, C.-W. Functional Elastic Knits Made of Bamboo Charcoal and Quick-Dry Yarns: Manufacturing Techniques and Property Evaluations. Applied Sciences 2017, 7, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkner, A.H. Bar Design for Length Compensation in Textile Winding. Textile Research Journal 1994, 64, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The design of double-wrapped yarns and weft-lined knitted fabric. A) A schematic diagram showing the spinning of double-wrapped yarns; B) Structure of the double-wrapped yarn; C) A schematic diagram showing the weft-lined fabric knitting process; D) A schematic diagram showing the structure of the weft-lined knitted fabric.

Figure 1.

The design of double-wrapped yarns and weft-lined knitted fabric. A) A schematic diagram showing the spinning of double-wrapped yarns; B) Structure of the double-wrapped yarn; C) A schematic diagram showing the weft-lined fabric knitting process; D) A schematic diagram showing the structure of the weft-lined knitted fabric.

Figure 2.

Effect of the inner and outer wrapping density on the mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns. A-C) Effect of inner wrapping density, A) Breaking force, B) Breaking elongation, and C) Queueing scoring; D-F) Effect of outer wrapping density, D) Breaking force, E) Breaking elongation, and F) Queueing scoring. Symbols on the bar graphs represent comparisons with the first bar (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 2.

Effect of the inner and outer wrapping density on the mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns. A-C) Effect of inner wrapping density, A) Breaking force, B) Breaking elongation, and C) Queueing scoring; D-F) Effect of outer wrapping density, D) Breaking force, E) Breaking elongation, and F) Queueing scoring. Symbols on the bar graphs represent comparisons with the first bar (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 3.

Effect of the taking-up and drafting ratios on mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns. A-C) Effect of taking-up ratio, A) Breaking force, B) Breaking elongation, and C) Queueing scoring; D-F) Effect of drafting ratio, D) Breaking force, E) Breaking elongation, and F) Queueing scoring. Symbols on the bar graphs represent comparisons with the first bar (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 3.

Effect of the taking-up and drafting ratios on mechanical properties of double-wrapped yarns. A-C) Effect of taking-up ratio, A) Breaking force, B) Breaking elongation, and C) Queueing scoring; D-F) Effect of drafting ratio, D) Breaking force, E) Breaking elongation, and F) Queueing scoring. Symbols on the bar graphs represent comparisons with the first bar (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 4.

Comparison of mechanical properties of the optimized yarn with a commercially available wrapped yarn. A, B) SEM images of A) the commercially available yarn and B) the optimized yarn; C) Comparison of yarn diameter; D) Stress-strain curves; E) Breaking force; F) Breaking elongation; G) Elastic recovery curves; H) Elastic recovery rate; I) Stress decay rate (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 4.

Comparison of mechanical properties of the optimized yarn with a commercially available wrapped yarn. A, B) SEM images of A) the commercially available yarn and B) the optimized yarn; C) Comparison of yarn diameter; D) Stress-strain curves; E) Breaking force; F) Breaking elongation; G) Elastic recovery curves; H) Elastic recovery rate; I) Stress decay rate (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the performance of knitted fabrics. A, B) Images of the fabric generated using the optimized double-wrapped yarn, A) front side, B) back side; C) Thickness of knitted fabrics; D) longitudinal density of knitted fabrics; E-H) Elastic recovery curves of knitted fabrics at different strains, E) 10%, F) 30%, G) 50%, H) 100%; I, J) Quantification of knitted fabrics at different strains, I) force, J) elastic recovery rate; K, l) Quantification of knitted fabrics for 5 cyclic stretching, K) force, L) elastic recovery rate (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the performance of knitted fabrics. A, B) Images of the fabric generated using the optimized double-wrapped yarn, A) front side, B) back side; C) Thickness of knitted fabrics; D) longitudinal density of knitted fabrics; E-H) Elastic recovery curves of knitted fabrics at different strains, E) 10%, F) 30%, G) 50%, H) 100%; I, J) Quantification of knitted fabrics at different strains, I) force, J) elastic recovery rate; K, l) Quantification of knitted fabrics for 5 cyclic stretching, K) force, L) elastic recovery rate (*: sig<0.05; **: sig<0.01; ***: sig<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Spandex and nylon filament.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Spandex and nylon filament.

| Materials |

Linear density (denier) |

Force

(cN) |

Elongation

|

Elastic recovery rate |

Stress decay rate |

Role |

| Spandex filament |

560 |

83.89 ± 2.57 cN

(300%) |

—— |

87.5% ± 3.2% |

10.0% ± 1.3% |

Core |

| Nylon filament |

70D/24f |

387.40 ± 8.82 cN (Break) |

34.46% ± 2.30% |

21.8% ± 10.2% |

15.7% ± 1.4% |

Sheath |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).