Submitted:

09 April 2024

Posted:

10 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

2.1. AD: Modifiable Risk Factors

2.2. AD: Management & Care

2.3. AD: Neurosurgical Management

2.3.1. Deep Brain Stimulation DBS

2.3.2. Encapsulated Cell Biodelivery (ECB)

2.3.3. Brain Computer Interface (BCI)

3. Parkinson’s Disease

3.1. PD: Modifiable Risk Factors

3.2. PD: Management & Care

3.3. PD: Neursurgical Intervention

3.3.1. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

3.3.2. Focused Ultrasound (FUS)

3.3.3. Radiofrequency & Radiosurgery

3.3.4. Brain Computer Interface (BCI)

4. Lewy Body Dementia (LBD)

4.1. LBD: Modifiable Risk Factors

4.2. LBD: Management & Care

4.3. LBD: Neursurgical Intervention

4.3.1. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

4.3.2. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

4.3.3. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

4.3.4. Electroconvulsive Therapy

5. Vascular Dementia (VD)

5.1. VD: Modifiable Risk Factors

5.2. VD: Management & Care

5.3. VD: Neursurgical Intervention

5.3.1. Brain Computer Interface (BCI)

6. Modifiable Risk Factors and Care of Non-Surgically Managed Forms of Cognitive Impairment

6.1. Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

6.1.1. MCI: Modifiable Risk Factors

6.1.2. MCI: Management & Care

6.2. Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)

6.2.1. FTD: Modifiable Risk Factors

6.2.2. FTD: Management & Care

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U. Nations, World Population Ageing 2020, 2020.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, J.; Song, H.; Ji, X. Treatable causes of adult-onset rapid cognitive impairment. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2019, 187, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chertkow, H. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: Introduction. Introducing a series based on the Third Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2007, 178, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, K. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Definitions, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014, 29, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, D.; Loewenstein, R.J.; Lewis-Fernández, R.; Sar, V.; Simeon, D.; Vermetten, E.; Cardeña, E.; Dell, P.F. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Depression Anxiety 2011, 28, 824–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, A.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia: a challenge to current thinking. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 189, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferencz, B.; Gerritsen, L. Genetics and Underlying Pathology of Dementia. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2015, 25, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarsland, D. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Dementia-Related Psychosis. 2020, 81. 81. [CrossRef]

- Dening, T.; Sandilyan, M.B. Dementia: definitions and types. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, V.N. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, J.H.; Lee, J.-H. Recent Updates on Subcortical Ischemic Vascular Dementia. J. Stroke 2014, 16, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Rodriguez, I.; Smailagic, N.; Roqué-Figuls, M.; Ciapponi, A.; Sanchez-Perez, E.; Giannakou, A.; Pedraza, O.L.; Cosp, X.B.; Cullum, S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Emergencias 2021, 2021, CD010783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, Y.; Yamaguchi, H. Early detection of dementia in the community under a community-based integrated care system. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgeta, V.; Mukadam, N.; Sommerlad, A.; Livingston, G. The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care: a call for action. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 36, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carotenuto, A.; Traini, E.; Fasanaro, A.M.; Battineni, G.; Amenta, F. Tele-Neuropsychological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

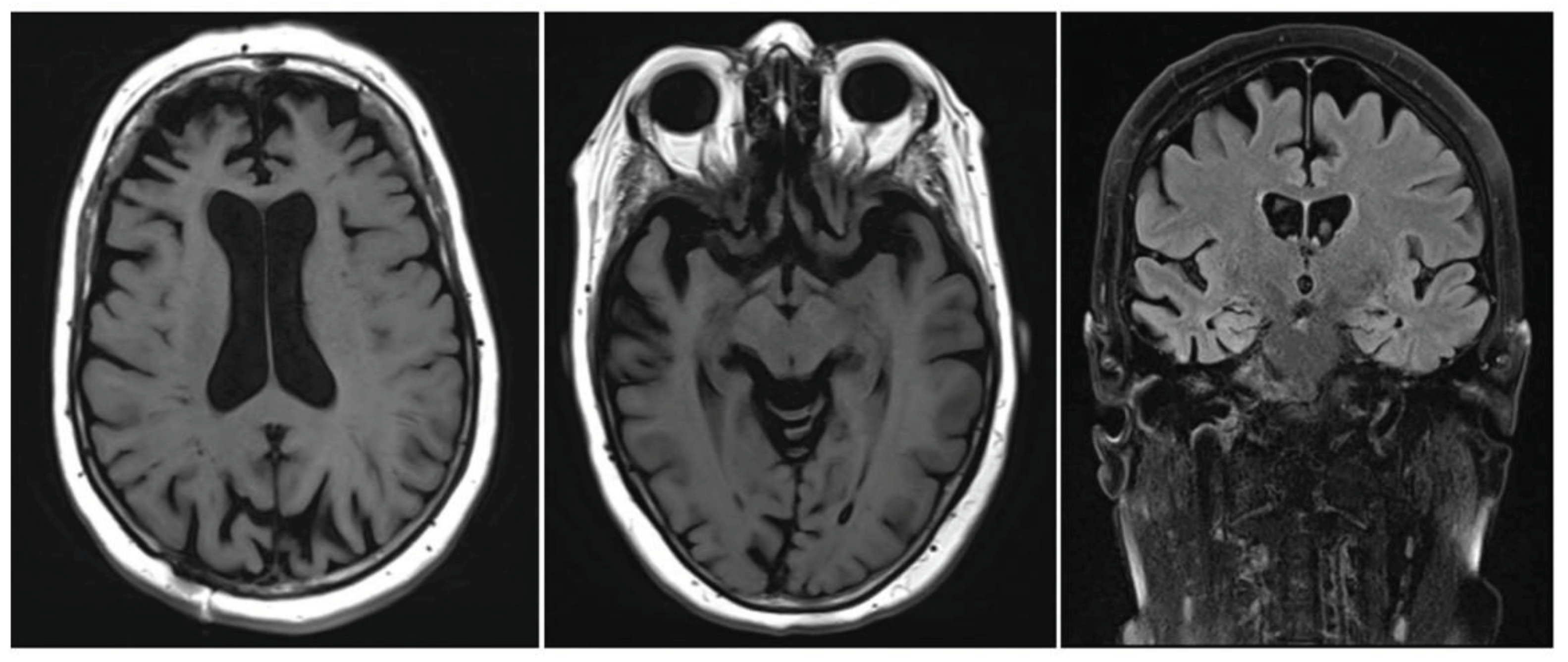

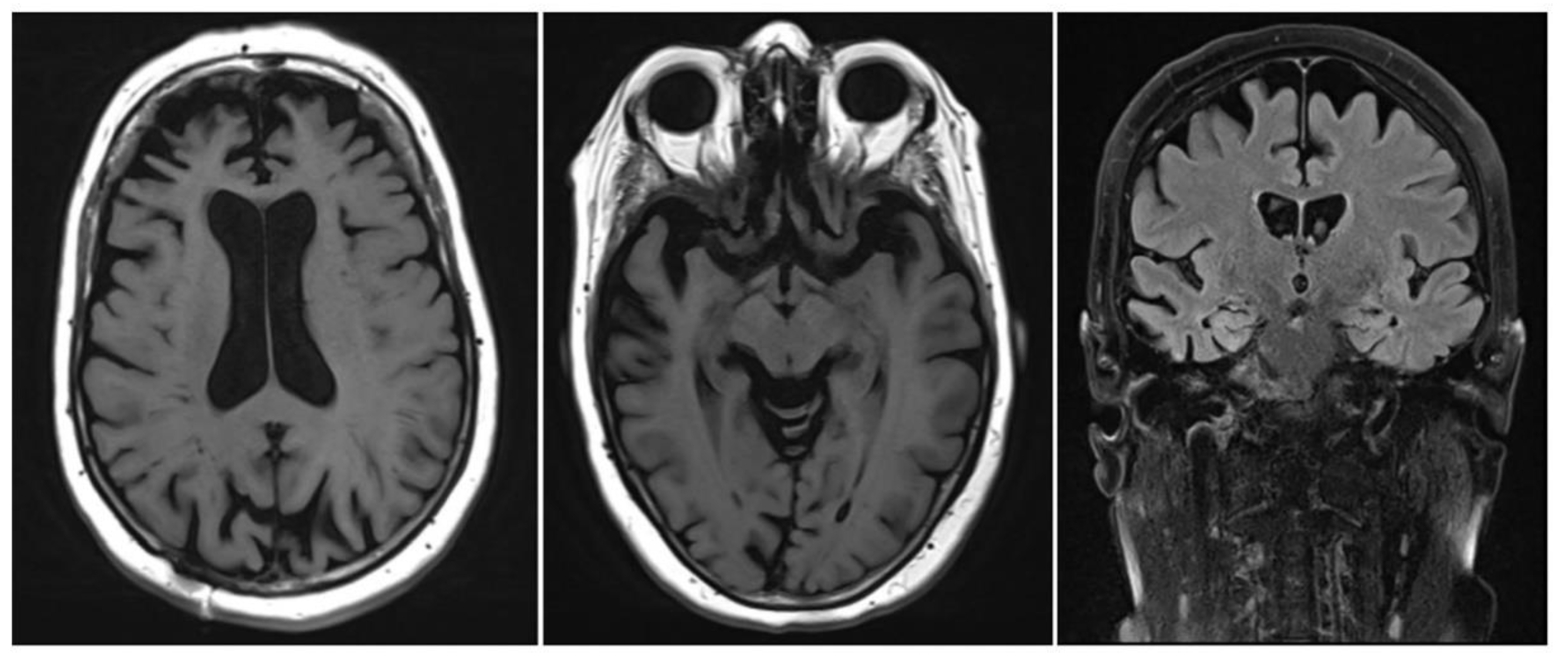

- Battineni, G.; Hossain, M.A.; Chintalapudi, N.; Traini, E.; Dhulipalla, V.R.; Ramasamy, M.; Amenta, F. Improved Alzheimer’s Disease Detection by MRI Using Multimodal Machine Learning Algorithms. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C.R. Jack Jr, D.A. C.R. Jack Jr, D.A. Bennett, K. Blennow, M.C. Carrillo, B. Dunn, S. Budd Haeberlein, D.M. Holtzman, W. Jagust, F. Jessen, J. Karlawish, E. Liu, J. Luis Molinuevo, T. Montine, C. Phelps, K.P. Rankin, C.C. Rowe, P. Scheltens, E. Siemers, H.M. Snyder, R. Sperling, A. Dement Author manuscript, NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease HHS Public Access Author manuscript, Alzheimers Dement 14 (2018).

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. J. Alzheimers Assoc. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, U.P.S.T.; Owens, D.K.; Davidson, K.W.; Krist, A.H.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W.; Kubik, M.; et al. Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. JAMA 2020, 323, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Joseph, J. G. Joseph, J. Bryan, J. Tricia, S. Ken, W. Jennifer, Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, Alzheimer’s & Dimentia 12 (2016).

- Kumar, J. Sidhu, A. Goyal, J.W. Tsao, Alzheimer Disease, 2023.

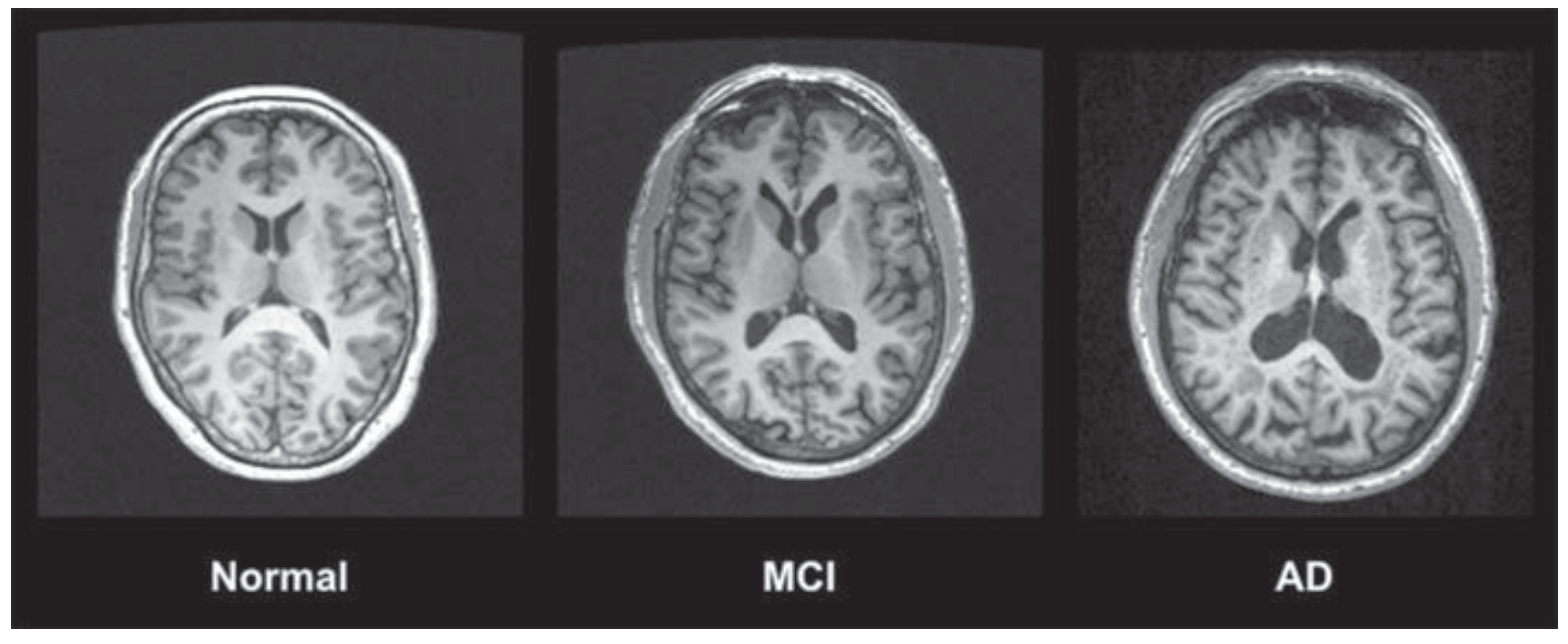

- Chandra, A.; Dervenoulas, G.; Politis, M. Magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, G.A.; Gamez, N., Jr.; Escobedo, G.; Calderon, O.; Moreno-Gonzalez, I. Modifiable Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litke, R.; Garcharna, L.C.; Jiwani, S.; Neugroschl, J. Modifiable Risk Factors in Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias: A Review. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winblad, B.; Wimo, A.; Wetterholm, A.-L.; Haglund, A.; Engedal, K.; Soininen, H.; Verhey, F.; Waldemar, G.; Zhang, R.; Burger, L.; et al. 4.044 Long-term efficacy of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: Results from a one-year placebo-controlled study and two-year follow-up study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003, 13, S404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winblad, B.; Engedal, K.; Soininen, H.; Verhey, F.; Waldemar, G.; Wimo, A.; Wetterholm, A.-L.; Zhang, R.; Haglund, A.; Subbiah, P.; et al. A 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology 2001, 57, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winblad, B.; Brodaty, H.; Gauthier, S.; Morris, J.C.; Orgogozo, J.; Rockwood, K.; Schneider, L.; Takeda, M.; Tariot, P.; Wilkinson, D. Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's disease: is there a need to redefine treatment success? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2001, 16, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.; Perdomo, C.; Pratt, R.D.; Birks, J.; Wilcock, G.K.; Evans, J.G. Donepezil for the symptomatic treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 19, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farlow, M.; Anand, R.; Jr, J.M.; Hartman, R.; Veach, J. A 52-Week Study of the Efficacy of Rivastigmine in Patients with Mild to Moderately Severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. Neurol. 2000, 44, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, S.; Kishi, T.; Nomura, I.; Sakuma, K.; Okuya, M.; Ikuta, T.; Iwata, N. The efficacy and safety of memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, B.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wan, Q.; Yu, F. Comparative efficacy of various exercise interventions on cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Sport Heal. Sci. 2021, 11, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.W. Alzheimer's disease: early diagnosis and treatment. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012, 18, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamani, C.; McAndrews, M.P.; Cohn, M.; Oh, M.; Zumsteg, D.; Shapiro, C.M.; Wennberg, R.A.; Lozano, A.M. Memory enhancement induced by hypothalamic/fornix deep brain stimulation. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittlinger, M.; Müller, S. Opening the debate on deep brain stimulation for Alzheimer disease – a critical evaluation of rationale, shortcomings, and ethical justification. BMC Med Ethic- 2018, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, I.; McGeer, P.; Beattie, L.; Calne, D.; Pate, B. Stimulation of the Basal Nucleus of Meynert in Senile Dementia of Alzheimer’s Type. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 1985, 48, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxton, A.W.; Lozano, A.M. Deep Brain Stimulation for the Treatment of Alzheimer Disease and Dementias. World Neurosurg. 2013, 80, S28–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Laxton, A.W.; Tang-Wai, D.F.; McAndrews, M.P.; Diaconescu, A.O.; Workman, C.I.; Lozano, A.M. Increased Cerebral Metabolism After 1 Year of Deep Brain Stimulation in Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyketsos, C.G.; Holroyd, K.B.; Fosdick, L.; Smith, G.S.; Leoutsakos, J.-M.; Munro, C.; Oh, E.S.; Drake, K.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Anderson, W.S.; et al. Deep brain stimulation targeting the fornix for mild Alzheimer dementia: design of the ADvance randomized controlled trial. Open Access J. Clin. Trials 2015, 7, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Tang, B.; Wu, Z.; Ure, K.; Sun, Y.; Tao, H.; Gao, Y.; Patel, A.J.; Curry, D.J.; Samaco, R.C.; et al. Forniceal deep brain stimulation rescues hippocampal memory in Rett syndrome mice. Nature 2015, 526, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirsaeedi-Farahani, K.; Halpern, C.H.; Baltuch, G.H.; Wolk, D.A.; Stein, S.C. Deep brain stimulation for Alzheimer disease: a decision and cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laxton, A.W.; Tang-Wai, D.F.; McAndrews, M.P.; Zumsteg, D.; Wennberg, R.; Keren, R.; Wherrett, J.; Naglie, G.; Hamani, C.; Smith, G.S.; et al. A phase I trial of deep brain stimulation of memory circuits in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.M.; Fosdick, L.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Leoutsakos, J.-M.; Munro, C.; Oh, E.; Drake, K.E.; Lyman, C.H.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Anderson, W.S.; et al. A Phase II Study of Fornix Deep Brain Stimulation in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2016, 54, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuello, A.C.; Bruno, M.A.; Allard, S.; Leon, W.; Iulita, M.F. Cholinergic Involvement in Alzheimer’s Disease. A Link with NGF Maturation and Degradation. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2009, 40, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.A.; Crutcher, K.A. Nerve Growth Factor and Alzheimer's Disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 1994, 5, 179–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyjolfsdottir, H.; Eriksdotter, M.; Linderoth, B.; Lind, G.; Juliusson, B.; Kusk, P.; Almkvist, O.; Andreasen, N.; Blennow, K.; Ferreira, D.; et al. Targeted delivery of nerve growth factor to the cholinergic basal forebrain of Alzheimer’s disease patients: application of a second-generation encapsulated cell biodelivery device. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2016, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksdotter-Jönhagen, M.; Linderoth, B.; Lind, G.; Aladellie, L.; Almkvist, O.; Andreasen, N.; Blennow, K.; Bogdanovic, N.; Jelic, V.; Kadir, A.; et al. Encapsulated Cell Biodelivery of Nerve Growth Factor to the Basal Forebrain in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2012, 33, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, J.J.; Krusienski, D.J.; Wolpaw, J.R. Brain-Computer Interfaces in Medicine. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, G.; da Rocha, J.L.D.; van der Heiden, L.; Raffone, A.; Birbaumer, N.; Belardinelli, M.O.; Sitaram, R. Toward a Brain-Computer Interface for Alzheimer's Disease Patients by Combining Classical Conditioning and Brain State Classification. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2012, 31, S211–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Zafar, S.S. S. Zafar, S.S. Yaddanapudi, Parkinson Disease, 2023.

- Alexoudi, A.; Alexoudi, I.; Gatzonis, S. Parkinson's disease pathogenesis, evolution and alternative pathways: A review. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 174, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Aich, S.; Kim, H.-C. Detection of Parkinson’s Disease from 3T T1 Weighted MRI Scans Using 3D Convolutional Neural Network. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belvisi, D.; Pellicciari, R.; Fabbrini, G.; Tinazzi, M.; Berardelli, A.; Defazio, G. Modifiable risk and protective factors in disease development, progression and clinical subtypes of Parkinson's disease: What do prospective studies suggest? Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 134, 104671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, S.L.; McKeage, K. Carbidopa/Levodopa ER Capsules (Rytary®, Numient™): A Review in Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Drugs 2015, 30, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, R. Parkinson’s Disease: From Pathogenesis to Pharmacogenomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, M.; Miyazaki, I.; Tanaka, K.-I.; Kabuto, H.; Iwata-Ichikawa, E.; Ogawa, N. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated antioxidant and neuroprotective effects of ropinirole, a dopamine agonist. Brain Res. 1999, 838, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheller, D.; Stichel-Gunkel, C.; Lübbert, H.; Porras, G.; Ravenscroft, P.; Hill, M.; Bezard, E. Neuroprotective effects of rotigotine in the acute MPTP-lesioned mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 432, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Guo, Y.; Xie, W.; Li, X.; Janokovic, J.; Le, W. Neuroprotection of Pramipexole in UPS Impairment Induced Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olanow, C.W.; Hauser, R.A.; Jankovic, J.; Langston, W.; Lang, A.; Poewe, W.; Tolosa, E.; Stocchi, F.; Melamed, E.; Eyal, E.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, delayed start study to assess rasagiline as a disease modifying therapy in Parkinson's disease (the ADAGIO study): Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2194–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Bi, Z.; Liu, J.; Si, W.; Shi, Q.; Xue, L.; Bai, J. Adverse effects produced by different drugs used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: A mixed treatment comparison. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.L. Adverse Events from the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease. Neurol. Clin. 2008, 26, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murman, D.L. Early Treatment of Parkinson's Disease: Opportunities for Managed Care. 2012, 18, S183–S188.

- Dayal, V.; Limousin, P.; Foltynie, T. Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease: The Effect of Varying Stimulation Parameters. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariz, M.; Blomstedt, P. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 292, 764–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamani, C.; Florence, G.; Heinsen, H.; Plantinga, B.R.; Temel, Y.; Uludag, K.; Alho, E.; Teixeira, M.J.; Amaro, E.; Fonoff, E.T. Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation: Basic Concepts and Novel Perspectives. eneuro 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, N. Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's Disease. Neurol. India 2019, 67, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.Y.; Tolleson, C. The role of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: an overview and update on new developments. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, ume 13, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschl, G.; Follett, K.A.; Luo, P.; Rau, J.; Weaver, F.M.; Paschen, S.; Steigerwald, F.; Tonder, L.; Stoker, V.; Reda, D.J. Comparing two randomized deep brain stimulation trials for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 132, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, J.; Caire, F.; Damon-Perrière, N.; Guehl, D.; Branchard, O.; Auzou, N.; Tison, F.; Meissner, W.G.; Krim, E.; Bannier, S.; et al. A Phase 2 Randomized Trial of Asleep versus Awake Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 2020, 99, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, H. The Study of Subthalamic Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson Disease-Associated Camptocormia. Med Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e919682–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetropoulos, S. A Randomized Trial of Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease. Yearb. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2008, 2008, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, N.C.; de Hemptinne, C.; Thompson, M.C.; Miocinovic, S.; Miller, A.M.; Gilron, R.; Ostrem, J.L.; Chizeck, H.J.; A Starr, P. Adaptive deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease using motor cortex sensing. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 046006–046006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beudel, M.; Brown, P. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 22, S123–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, W.; Gilron, R.; Little, S.; Tinkhauser, G. Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation: From Experimental Evidence Toward Practical Implementation. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habets, J.G.; Heijmans, M.; Kuijf, M.L.; Janssen, M.L.; Temel, Y.; Kubben, P.L. An update on adaptive deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1834–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Candamil, S.; Ferleger, B.I.; Haddock, A.; Cooper, S.S.; Herron, J.; Ko, A.; Chizeck, H.J.; Tangermann, M. A Pilot Study on Data-Driven Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation in Chronically Implanted Essential Tremor Patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Clennell, B.; Steward, T.G.J.; Gialeli, A.; Cordero-Llana, O.; Whitcomb, D.J. Focused Ultrasound Stimulation as a Neuromodulatory Tool for Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Park, C.K.; Kim, M.; Lee, P.H.; Sohn, Y.H.; Chang, J.W. The efficacy and limits of magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound pallidotomy for Parkinson’s disease: a Phase I clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 130, 1853–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, H.M.; Krishna, V.; Elias, W.J.; Cosgrove, G.R.; Gandhi, D.; Aldrich, C.E.; Fishman, P.S. MR-guided focused ultrasound pallidotomy for Parkinson’s disease: safety and feasibility. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 135, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, R.; Máñez-Miró, J.U.; Rodríguez-Rojas, R.; del Álamo, M.; Shah, B.B.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; Pineda-Pardo, J.A.; Monje, M.H.; Fernández-Rodríguez, B.; Sperling, S.A.; et al. Randomized Trial of Focused Ultrasound Subthalamotomy for Parkinson’s Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2501–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, S.; Martínez-Fernández, R.; Elias, W.J.; del Alamo, M.; Eisenberg, H.M.; Fishman, P.S. The role of high-intensity focused ultrasound as a symptomatic treatment for Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.M.; Villalba, E.N.; Rodriguez-Rojas, R.; del Álamo, M.; A Pineda-Pardo, J.; Obeso, I.; Mata-Marín, D.; Guida, P.; Jimenez-Castellanos, T.; Pérez-Bueno, D.; et al. Unilateral focused ultrasound subthalamotomy in early Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 95, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, R.; Rodríguez-Rojas, R.; del Álamo, M.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; A Pineda-Pardo, J.; Dileone, M.; Alonso-Frech, F.; Foffani, G.; Obeso, I.; Gasca-Salas, C.; et al. Focused ultrasound subthalamotomy in patients with asymmetric Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foffani, G.; Trigo-Damas, I.; Pineda-Pardo, J.A.; Blesa, J.; Rodríguez-Rojas, R.; Martínez-Fernández, R.; Obeso, J.A. Focused ultrasound in Parkinson's disease: A twofold path toward disease modification. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horisawa, S.; Taira, T. [Radiofrequency Lesioning Surgery for Movement Disorders]. 2021, 49, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Serizawa, T. Gamma knife radiosurgery in movement disorders: Indications and limitations. Mov. Disord. 2016, 32, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzini, A.; Moosa, S.; Servello, D.; Small, I.; DiMeco, F.; Xu, Z.; Elias, W.J.; Franzini, A.; Prada, F. Ablative brain surgery: an overview. Int. J. Hyperth. 2019, 36, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, S.S.; Niranjan, A.; Iii, E.A.M.; Flickinger, J.C.; Lunsford, L.D. Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Intractable Tremor-Dominant Parkinson Disease: A Retrospective Analysis. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 2017, 95, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinel, Y.; Alkhalfan, F.; Qiao, N.; Velimirovic, M. Outcomes in Lesion Surgery versus Deep Brain Stimulation in Patients with Tremor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018, 123, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, V.K.; Parker, J.J.; Hornbeck, T.S.; Santini, V.E.; Pauly, K.B.; Wintermark, M.; Ghanouni, P.; Stein, S.C.; Halpern, C.H. Cost-effectiveness of focused ultrasound, radiosurgery, and DBS for essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.; Pogosyan, A.; Neal, S.; Zavala, B.; Zrinzo, L.; Hariz, M.; Foltynie, T.; Limousin, P.; Ashkan, K.; FitzGerald, J.; et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.M. Turconi, S. M.M. Turconi, S. Mezzarobba, G. Franco, P. Busan, E. Fornasa, J. Jarmolowska, A. Accardo, P.P. Battaglini, BCI-Based Neuro-Rehabilitation Treatment for Parkinson ’ s Disease : Cases Report, in: TSPC2014 - November, 28th - T11, 2014: pp. 63–65.

- Chin, K.S.; Teodorczuk, A.; Watson, R. Dementia with Lewy bodies: Challenges in the diagnosis and management. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2019, 53, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouliaras, L.; O’brien, J.T. The use of neuroimaging techniques in the early and differential diagnosis of dementia. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4084–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, B.P.; Orr, C.F.; Ahlskog, J.E.; Ferman, T.J.; Roberts, R.; Pankratz, V.S.; Dickson, D.W.; Parisi, J.; Aakre, J.A.; Geda, Y.E.; et al. Risk factors for dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2013, 81, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.R. Tampi, J.J. R.R. Tampi, J.J. Young, D. Tampi, Behavioral symptomatology and psychopharmacology of Lewy body dementia, in: 2019: pp. 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.-P.; McKeith, I.G.; Burn, D.J.; Boeve, B.F.; Weintraub, D.; Bamford, C.; Allan, L.M.; Thomas, A.J.; O'Brien, J.T. New evidence on the management of Lewy body dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 19, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, S.; McKeith, I.G.; O’brien, J.T.; Burn, D.J. The role of levodopa in the management of dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, K.E.; Storr, N.J.; Barr, P.G.; Rajkumar, A.P. Systematic review of pharmacological interventions for people with Lewy body dementia. Aging Ment. Heal. 2022, 27, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaute, H.; Persoons, P. [Early use of memantine in the treatment of Lewy body dementia]. . 2016, 58, 814–817. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, E.; Ikeda, M.; Kosaka, K. ; on behalf of the Donepezil-DLB Study Investigators Donepezil for dementia with Lewy bodies: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeith, I.; Del Ser, T.; Spano, P.; Emre, M.; Wesnes, K.; Anand, R.; Cicin-Sain, A.; Ferrara, R.; Spiegel, R. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet 2000, 356, 2031–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varanese, S.; Perfetti, B.; Gilbert-Wolf, R.; Thomas, A.; Onofrj, M.; Di Rocco, A. Modafinil and armodafinil improve attention and global mental status in Lewy bodies disorders: preliminary evidence. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 1095–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratwicke, J.; Zrinzo, L.; Kahan, J.; Peters, A.; Brechany, U.; McNichol, A.; Beigi, M.; Akram, H.; Hyam, J.; Oswal, A.; et al. Bilateral nucleus basalis of Meynert deep brain stimulation for dementia with Lewy bodies: A randomised clinical trial. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrin, H.; Fang, T.; Servant, D.; Aarsland, D.; Rajkumar, A.P. Systematic review of the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions in people with Lewy body dementia. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2017, 30, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, G.J.; Firbank, M.J.; Kumar, H.; Chatterjee, P.; Chakraborty, T.; Dutt, A.; Taylor, J.-P. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation upon attention and visuoperceptual function in Lewy body dementia: a preliminary study. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2015, 28, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, G.J.; Colloby, S.J.; Firbank, M.J.; McKeith, I.G.; Taylor, J.-P. Consecutive sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation do not remediate visual hallucinations in Lewy body dementia: a randomised controlled trial. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.-M.; Cheng, K.-S.; Tang, C.-H.; Hou, N.-T.; Chien, P.-F.; Huang, Y.-C. 419 - Effect of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2021, 33, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, L.; Evangelisti, S.; Siniscalco, A.; Lodi, R.; Tonon, C.; Mitolo, M. Non-Pharmacological Treatments in Lewy Body Disease: A Systematic Review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2023, 52, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Liu, K.; Guo, L. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): A possible novel therapeutic approach to dementia with Lewy bodies. Med Hypotheses 2010, 74, 877–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antczak, J.; Rusin, G.; Słowik, A. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as a Diagnostic and Therapeutic Tool in Various Types of Dementia. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.-P.; Firbank, M.; Barnett, N.; Pearce, S.; Livingstone, A.; Mosimann, U.; Eyre, J.; McKeith, I.G.; O'Brien, J.T. Visual hallucinations in dementia with Lewy bodies: transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirov, G.; Jauhar, S.; Sienaert, P.; Kellner, C.H.; McLoughlin, D.M. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression: 80 years of progress. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 219, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukatsu, T.; Kanemoto, K. Electroconvulsive therapy improves psychotic symptoms in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria, C.; Libuy, J.; Alarcón, J.; Rodriguez, J. ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY FOR AGITATION IN LEWY BODIES DEMENTIA. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S1020–S1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.E. Clinical presentations and epidemiology of vascular dementia. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Freudenberger, P.; Seiler, S.; Schmidt, R. Genetics of subcortical vascular dementia. Exp. Gerontol. 2012, 47, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B. Risk Factors for Vascular Dementia and Alzheimer Disease. Stroke 2004, 35, 2620–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lee, W.T.; Park, K.A.; Lee, J.E. Association between Risk Factors for Vascular Dementia and Adiponectin. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.T.; Thomas, A. Vascular dementia. Lancet 2015, 386, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcock, G.; Möbius, H.; Stöffler, A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study of memantine in mild to moderate vascular dementia (MMM500). Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 17, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgogozo, J.-M.; Rigaud, A.-S.; Stöffler, A.; Möbius, H.-J.; Forette, F. Efficacy and Safety of Memantine in Patients With Mild to Moderate Vascular Dementia. Stroke 2002, 33, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; Yin, H.; Jiang, X.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Yang, T. Poststroke Cognitive Impairment Research Progress on Application of Brain-Computer Interface. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyukmanov, R.K.; Aziatskaya, G.A.; Mokienko, O.A.; Varako, N.A.; Kovyazina, M.S.; Suponeva, N.A.; Chernikova, L.A.; Frolov, A.A.; Piradov, M.A. Post-stroke rehabilitation training with a brain-computer interface: a clinical and neuropsychological study. Zhurnal Nevrol. i psikhiatrii im. S.S. Korsakova 2018, 118, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, S.Y.; Lee, T.-S.; Goh, S.J.A.; Phillips, R.; Guan, C.; Cheung, Y.B.; Feng, L.; Wang, C.C.; Chin, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.H.; et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial using EEG-based brain–computer interface training for a Chinese-speaking group of healthy elderly. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, P.B.; Scuteri, A.; Black, S.E.; DeCarli, C.; Greenberg, S.M.; Iadecola, C.; Launer, L.J.; Laurent, S.; Lopez, O.L.; Nyenhuis, D.; et al. Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Stroke 2011, 42, 2672–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeith, I.G.; Ferman, T.J.; Thomas, A.J.; Blanc, F.; Boeve, B.F.; Fujishiro, H.; Kantarci, K.; Muscio, C.; O'Brien, J.T.; Postuma, R.B.; et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2020, 94, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvan, I.; Goldman, J.G.; Tröster, A.I.; Schmand, B.A.; Weintraub, D.; Petersen, R.C.; Mollenhauer, B.; Adler, C.H.; Marder, K.; Williams-Gray, C.H.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.L.; Unverzagt, F.; LaMantia, M.A.; Khan, B.A.; Boustani, M.A. Risk Factors for the Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, A.M. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 33, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguli, M.; Fu, B.; Snitz, B.E.; Hughes, T.F.; Chang, C.-C.H. Mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2013, 80, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschetti, R.; Albanese, E.; Vanacore, N.; Maggini, M. Cholinesterase Inhibitors in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review of Randomised Trials. PLOS Med. 2007, 4, e338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belleville, S.; Clément, F.; Mellah, S.; Gilbert, B.; Fontaine, F.; Gauthier, S. Training-related brain plasticity in subjects at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2011, 134, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Tian, J.-Z.; Zhu, A.-H.; Yang, C.-Z. [Clinical study on a randomized, double-blind control of Shenwu gelatin capsule in treatment of mild cognitive impairment]. . 2007, 32, 1800–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gates, N.J.; Sachdev, P.S.; Singh, M.A.F.; Valenzuela, M. Cognitive and memory training in adults at risk of dementia: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Li, N.; Li, B.; Wang, P.; Zhou, T. Cognitive intervention for persons with mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Su, W.; Dang, H.; Han, K.; Lu, H.; Yue, S.; Zhang, H. Exercise Training for Mild Cognitive Impairment Adults Older Than 60: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2022, 88, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhuang, S. Current Perspective of Brain-Computer Interface Technology on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 36, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppala, G.K.; Gorthi, S.P.; Chandran, V.; Gundabolu, G. Frontotemporal Dementia - Current Concepts. 2021, 69, 1144–1152. [CrossRef]

- Eid, H.R.; Rosness, T.A.; Bosnes, O.; Salvesen. ; Knutli, M.; Stordal, E. Smoking and Obesity as Risk Factors in Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: The HUNT Study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, R.M.; Boxer, A.L. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2014, 16, 319–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liepelt, I.; Gaenslen, A.; Godau, J.; Di Santo, A.; Schweitzer, K.J.; Gasser, T.; Berg, D. Rivastigmine for the treatment of dementia in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy: Clinical observations as a basis for power calculations and safety analysis. Alzheimer's Dement. 2010, 6, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvan, I.; Phipps, M.; Pharr, V.L.; Hallett, M.; Grafman, J.; Salazar, A. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology 2001, 57, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbrini, G.; Barbanti, P.; Bonifati, V.; Colosimo, C.; Gasparini, M.; Vanacore, N.; Meco, G. Donepezil in the treatment of progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2001, 103, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litvan, I.; Med, C.G.; Atack, J.R.; Gillespie, M.; Kask, A.M.; Mouradian, M.M.; Chase, T.N. Physostigmine treatment of progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann. Neurol. 1989, 26, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Takamatsu, J. Pilot study of pharmacological treatment for frontotemporal dementia: Risk of donepezil treatment for behavioral and psychological symptoms. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, M.F.; Shapira, J.S.; McMurtray, A.; Licht, E. Preliminary Findings: Behavioral Worsening on Donepezil in Patients With Frontotemporal Dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertesz, A.; Morlog, D.; Light, M.; Blair, M.; Davidson, W.; Jesso, S.; Brashear, R. Galantamine in Frontotemporal Dementia and Primary Progressive Aphasia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008, 25, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, R.; Torre, P.; Antonello, R.M.; Cattaruzza, T.; Cazzato, G.; Bava, A. Rivastigmine in Frontotemporal Dementia. Drugs Aging 2004, 21, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebert, F.; Stekke, W.; Hasenbroekx, C.; Pasquier, F. Frontotemporal Dementia: A Randomised, Controlled Trial with Trazodone. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2004, 17, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmal, L.; Flegar, S.J.; Wang, J.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Komossa, K.; Leucht, S. Quetiapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Emergencias 2013, CD006625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.F.; Shapira, J.S.; McMurtray, A.; Licht, E. Preliminary Findings: Behavioral Worsening on Donepezil in Patients With Frontotemporal Dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxer, A.L.; Knopman, D.S.; I Kaufer, D.; Grossman, M.; Onyike, C.; Graf-Radford, N.; Mendez, M.; Kerwin, D.; Lerner, A.; Wu, C.-K.; et al. Memantine in patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).