Submitted:

08 April 2024

Posted:

09 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- ### KESKEN. TÄRKEÄÄ: 7.4.2024 all Figureures, tables and Vignettes sijoitetaan omille paikoilleen. Mitään ei säilytetä lopussa. ###

3. Results

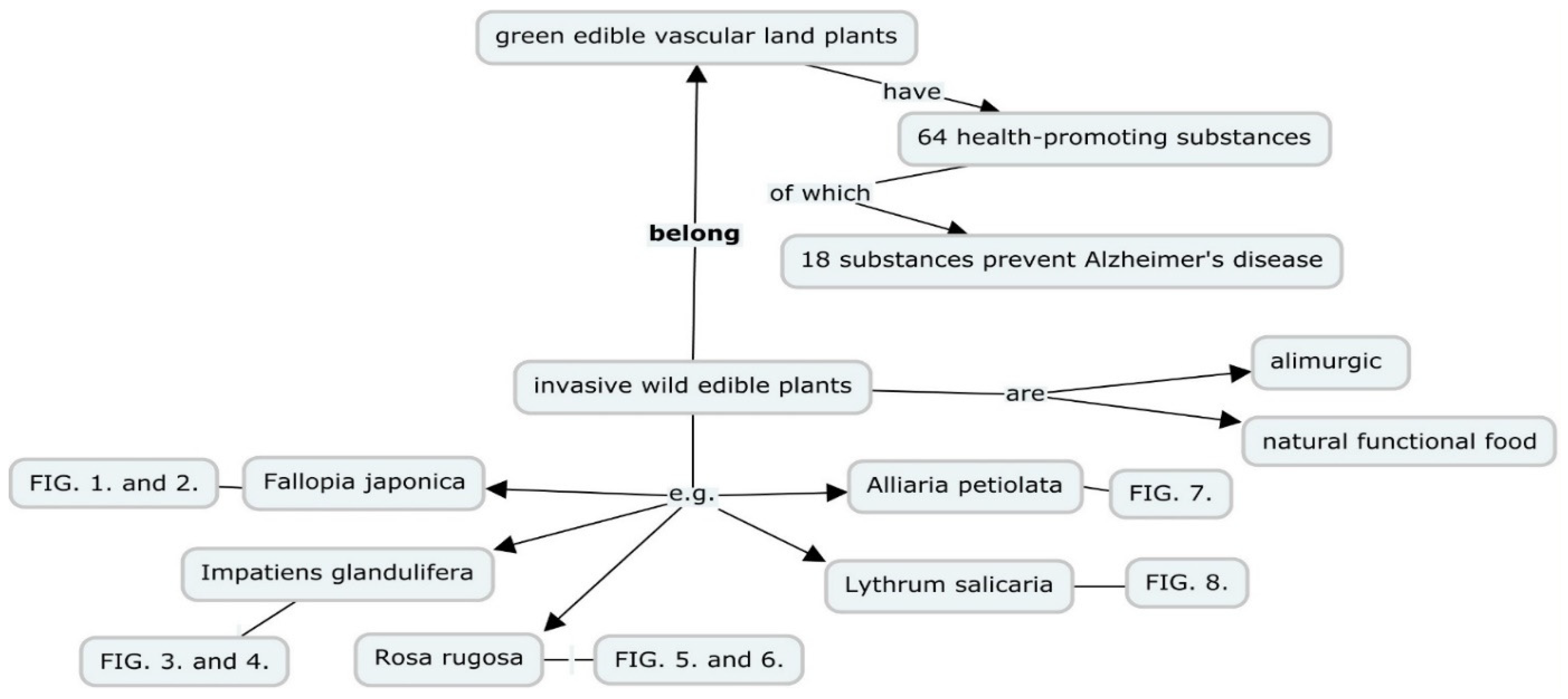

3.1. Answers to Research Questions (1) How did I find 64 Health-Promoting Substances in all Green Vascular WEPs? (2) According to Experimental Research, How Many of These Substances Prevent Alzheimer's Disease?

| galactolipids | FOR HUMANS: According to Kuan & al. (2022), Cheng & al. (2016), and Winther & al. (2016), galactolipids have the following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidants, 2) reduce oxidative stress in cells, 3) anti-inflammatory, 3) improve skin wrinkles, moisture, and elasticity in healthy subjects, and 4) antitumor. IN PLANTS: According to Suh & al. (2022), Zhu & al. (2022), and Kim (2020), galactolipids: 1) are a component of the chloroplast membrane, 2) take part in photosynthesis, 3) prevent lack of phosphorus (P): “the plastid membranes mainly consist of glycolipids, while extraplastidic membranes mainly consist of phospholipids. Under P-deficiency conditions, phospholipids can be degraded to release the phosphate group; then the non-phosphorus galactolipids are compensatively synthesized to replace the phospholipid”. Cheng, B. & al. 2016. The genus Rosa and arthritis: Overview on pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacological Research 114, 219-234. Kim, H. 2020. Lipid metabolism in plants. Plants 9, 871. Kuan, C. & al. 2022. Ameliorating effect of Crassocephalum rabens (Asteraceae) extract on skin aging: A randomized, parallel, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Nutrients 14, 2655. Suh, MC. & al. 2022. Plant lipids: trends and beyond. Journal of Experimental Botany 73(9), 2715–2720. Winther K. & al. 2016. Bioactive ingredients of rose hips (Rosa canina L) with special reference to antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties: in vitro studies. Botanics: Targets and Therapy 6, 11—23. Zhu, S. & al. 2022. Advances in plant lipid metabolism responses to phosphate scarcity. Plants 11, 2238. |

| oxylipins | FOR HUMANS: According to Shinto & al. (2022) and Caligiuri (2017), oxylipins have the following health-promoting properties: 1) antiaging, 2) prevent cardiovascular disease;3) prevent heart disease, 4) take part in immunity, 5) prevent inflammation, 6) prevent blood coagulation, and 7) take part in vascular tone regulation, 7) may prevent Alzheimer's disease. IN PLANTS: According to Sugimoto (2022), oxylipins 1) take part in plant growth, 2) take part in development, 3) take part in interactions with biotic and abiotic stressors, 4) take part in plant-environment interactions, 5) take part in plant-pathogen interactions, 6) take part in plant-plant interactions, 7) act as defense phytohormones, 8) take part in the activation of secondary metabolite accumulation, such as alkaloids and terpenoids, which act as toxic compounds to pathogens and pests. Caligiuri, S. 2017. Dietary modulation of oxylipins in cardiovascular disease and aging. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 313(5), H903–H918. Shinto L. & al. 2022. A Review of oxylipins in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD): potential therapeutic targets for the modulation of vascular tone and inflammation. Metabolites 12, 826. Sugimoto K. & al. 2022. Editorial: Oxylipins: The front line of plant interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science 13, 878765. |

| phenylpropanoids | FOR HUMANS: According to Jaye & al. (2022), Navarre & al. (2022), Neelam & al. (2020), and Kolaj & al. (2018), phenylpropanoids have the following health-promoting properties:1) antioxidant, 2) anti-inflammatory, 3) antimicrobial, 4) antidiabetic, 5) anticancer, 6) renoprotective, 7) hepatoprotective, 8) cardioprotective, 8) protect mitochondria, 9) neuroprotective, and 10) may prevent Alzheimer’s disease. IN PLANTS: According to Ramaroson & al. (2022), Dong & Lin (2020, and Deng & Lu (2017), phenylpropanoids: 1) are a large class of plant secondary metabolites derived from aromatic amino acids, mostly phenylalanine; 2) mainly include flavonoids, lignin, lignans, monolignols, hydroxycinnamic acid, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and coumarins; 3) are widely distributed in the plant kingdom; 4) take part in plant development; 5) are essential components of cell walls; 6) take part in plant defense against biotic or abiotic stresses; 7) protect against high light and UV radiation; 8) phytoalexins against herbivores and pathogens, and 9) act as floral pigments to mediate plant-pollinator interactions. Deng, Y. & Lu, S. 2017. Biosynthesis and regulation of phenylpropanoids in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 36(4), 257-290. Dong, N. & Lin, G. 2020. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 63(1), 180–209. Epifano, F. & al. 2023. Protection of mitochondrial potential and activity by oxyprenylated phenylpropanoids. Antioxidants 12(2), 259. Jaye, K. & al. 2022. The role of crucial gut microbial metabolites in the development and treatment of cancer. Gut Microbes 14(1), e2038865, 1-29. Kolaj, I. & al. 2018. Phenylpropanoids and Alzheimer's disease: A potential therapeutic platform. Neurochemistry International 120, 99-111. Navarre, D. & al. 2022. Plant antioxidants affect human and gut health, and their biosynthesis is influenced by environment and reactive oxygen species. Oxygen 2(3), 348-370. Neelam, A. & al. 2020. Phenylpropanoids and their derivatives: biological activities and its role in food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 60(16), 2655-2675 Ramaroson, M. & al. 2022. Role of phenylpropanoids and flavonoids in plant resistance to pests and diseases. Molecules 27(23), 8371. |

| phospholipids |

FOR HUMANS: According to Chang & al. (2022) and Küllenberg & al. (2012), phospholipids promote health in the following ways: 1) anti-inflammatory, 2) anticancer, 3) prevent coronary heart disease, 4) reduce cholesterol levels, 5) prevent platelet aggregation, 6) prevent hypertension, 7) reduce risk of arteriosclerosis, 8) promote the intestinal absorption of cholesterol and other lipids, 9) promote brain health by carrying essential polyunsaturated fats to the brain, 10) improve memory, 11) improve cognition, 12) improve immunological functions, and 13) prevent liver diseases. IN PLANTS: According to Khosa (2022), Shu & al. (2022), and Wang & al. (2022), phospholipids: 1) are components of cell membranes, 2) phospholipids take part in the coordination of fundamental life processes at the cellular level, 3) take part in cell signaling, and 4) regulate flowering. Chang, W. & al. 2022. Phospholipids in small extracellular vesicles: emerging regulators of neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Cytotherapy 24(2), 93-100 Khosa, J. 2022. Phospholipids and flowering regulation. Trends in Plant Science 27(7), 621-623. Küllenberg, D. & al. 2012. Health effects of dietary phospholipids. Lipids in Health and Disease 11, 3, 1 -16. Suh, MC. & al. 2022. Plant lipids: trends and beyond. Journal of Experimental Botany 73(9), 2715–2720. Wang, P & al. 2022. Keep in contact: multiple roles of endoplasmic reticulum-membrane contact sites and the organelle interaction network in plants. New Phytologist. Accepted author manuscript. |

| plant fatty acids |

FOR HUMANS: 1) According to Cai & al. (2022), Casillas-Vargas & al. (2021), Trautwein & McKay (2020), and Marsiñach & Cuenca (2019), plant fatty acids have the following health-promoting properties: 1) take part in several metabolic and structural functions, 2) are components of the cell membranes, 3) take part in the transport of vitamins, 4) regulate the concentration of lipids in plasma; 5) produce precursors of eicosanoids, decosanoids, steroid hormones, and biliary acid, which are fundamental for the adequate functioning of the metabolism; 6) the most crucial energetic nutrient. Researchers recommend that at least 20% of the total energy intake should derive from lipids; 7) reduce the risk of cancers; 8) positively influence dyslipidemia; 9) lower the risk of cardiovascular diseases; and 10) antibacterial. IN PLANTS: According to Kalinger & al. (2020): 1) Plants use fatty acids to synthesize acyl lipids for many different cellular, physiological, and defensive roles, such as 2) the synthesis of the essential membrane, 3) storage, 4) surface lipids, 5) the production of various fatty acid-derived metabolites used for signaling, and 6) the production of various fatty acid-derived metabolites used for defense. Cai, H. & al. 2022. Low-carbohydrate diet and risk of cancer incidence: The Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Cancer Science 113, 744–755. Casillas-Vargas, G. & al. 2021. Antibacterial fatty acids: An update of possible mechanisms of action and implications in developing the next generation of antibacterial agents. Progress in Lipid Research 82, 101093. Kalinger, R. & al. 2020. Fatty acyl synthetases and thioesterases in plant lipid metabolism: diverse functions and biotechnological applications. Lipids 55(5), 435-455. Marsiñach, M. & Cuenca, A. 2019. The impact of sea buckthorn oil fatty acids on human health. Lipids in Health and Disease 18:145. Trautwein, E. & McKay, S. 2020. The role of specific components of a plant-based diet in the management of dyslipidemia and the impact on cardiovascular risk. Nutrients 12, 2671; doi:10.3390/nu12092671 |

| plant lipids |

FOR HUMANS: According to Amadi & al. (2022), Lim & al. (2022), and Yin (2022), lipids: 1) are crucial to several functional processes in the body, 2) are crucial to the storage of energy, 3) are crucial to the regulation of hormones, 4) are crucial to the transportation of nutrients, and 5) regulate adaptive immunity (T cells), 6) a moderate amount of unsatisfied omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammations, 7) The brain has the highest lipids content after the adipose tissue. A part of its unsatisfied fatty acids usually comes from plants. IN PLANTS: According to Suh & al. (2022), Kim (2020), and Macabuhay & al. (2022), lipids: 1) are one of the primary biological molecules in plants, 2) have a wide variety of functions in plant cells, both as structural components and as bioactive substances, 4) are essential for the integrity of cells and organelles by acting as a hydrophobic barrier for the membrane, 5) are involved in cell signaling, 6) are component of the chloroplast membrane, take part in photosynthesis, 8) store energy for seed germination, 9) contribute to defense against diseases, 10) contribute to defense against pests, and 11) take part plant root–microbe interactions. Amadi, P. & al. 2022. Lipid metabolism and human diseases. Frontiers in Physiology 13, 1072903. Kim, H. 2020. Lipid metabolism in plants. Plants 9, 871. Lim, S. & al. 2022. Lipid metabolism in T cell signaling and function. Nature Chemical Biology 18, 470–481. Macabuhay, A. & al. 2022. Modulators or facilitators? Roles of lipids in plant root–microbe interactions. Trends in Plant Science 27(2), 180 – 190. Suh, M. & al. 2022. Plant lipids: trends and beyond. Journal of Experimental Botany 73(9), 2715–2720. Yin, F. 2022. Lipid metabolism and Alzheimer's disease: clinical evidence, mechanistic link and therapeutic promise. The FEBS Journal, the online version before press: 07 January 2022. |

| salicylic acid |

FOR HUMANS: According to Ding & al. (2023), Thrash-Williams & al. (2016), Randjelovic & al. (2015), and Baxter & al. (2001), salicylic acid has the following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidant, 2) anti-inflammatory, 3) cardioprotective,4) antidiabetic and 5) neuroprotective. IN PLANTS: According to Ding & al. (2023), Jia & al. (2023), Mishra & Baek (2021), and Yang & al. (2023), both bacteria and land plants produce salicylic acid. One of the most essential phytohormones is salicylic acid. Plants use salicylic acid: 1) signaling in heat production (thermogenesis), 2) as a signaling molecule during pathogen infection; 3) The increased levels of salicylic acid are associated with the induction of defense genes and systemic acquired resistance (plant immunity); 4) Salicylic acid is the critical signal molecule in regulating the activation of local and systemic defense responses against infections by pathogens; 5) Salicylic acid has a regulatory role in abiotic stresses, like heat stress and drought, and biotic stresses, such as the systemic acquired resistance-mediated defense response against pathogen infection; 6) Salicylic acid regulates plant growth and development processes, such as photosynthesis, respiration, vegetative growth, seed germination, flowering, senescence, etc. Baxter, G. & al. 2001. Salicylic acid in soups prepared from organically and non-organically grown vegetables. European Journal of Nutrition 40, 289–292 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s394-001-8358-x Ding, Y. & al. 2023. Shared and related molecular targets and actions of salicylic acid in plants and humans. Cells 12(2), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12020219 Jia, X. & al. 2023. The origin and evolution of salicylic acid signaling and biosynthesis in plants. Molecular Plant 16(1), 245-259.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2022.12.002 Mishra, A.K.& Baek, K. 2021. Salicylic acid biosynthesis and metabolism: A divergent pathway for plants and bacteria. Biomolecules 11, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11050705 Randjelovic, P. & al. 2015. The beneficial biological properties of salicylic acid. Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis 32(4):259-265. Thrash-Williams, B. & al. 2016. Methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic toxicity is prevented owing to the neuroprotective effects of salicylic acid. Life Sciences 154, 24-29. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0024320516301229 Vizzari, G. & al. 2019. Circulating salicylic acid and metabolic profile after 1-year nutritional–behavioral intervention in children with obesity. Nutrients 11, 1091. doi:10.3390/nu11051091 Yang. W. & al. 2023. Emerging roles of salicylic acid in plant saline stress tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24(4), 3388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043388 |

|

FOR HUMANS: According to Sugawara (2022), Yamashita & al. (2021), and Norris & Blesso (2017), sphingolipids have the following health-promoting properties: 1) anti-inflammatory, 2) prevent dyslipidemia, 3) prevent nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, 4) improve skin barrier function, 5) prevent diseases, 6) prevent cancer, 7) prevent metabolic syndrome, 8) improve lipid absorption, 9) improve metabolism, IN PLANTS: According to Haslam & Feussner (2022), Suh & al. (2022), and Zeng & Yao (2022), Sphingolipids are essential metabolites found in all plant species. Sphingolipids: 1) take part in maintaining plasma membrane integrity. They are components of cell membranes; 2) take part in responses to biotic and abiotic stresses; 3) participate in intracellular signaling; 4) are essential for controlling cellular homeostasis; and 5) regulate plant immunity. Haslam, T & Feussner, T. 2022. Diversity in sphingolipid metabolism across land plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 73(9), 2785–2798, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab558 Norris, G. & Blesso, C. 2017. Dietary sphingolipids: potential for management of dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrition Reviews 75(4), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nux004 Sugawara, T. 2022. Sphingolipids as functional food components: benefits in skin improvement and disease prevention. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 70(31), 9597–9609. Suh, M. & al. 2022. Plant lipids: trends and beyond. Journal of Experimental Botany 73(9), 2715–2720. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erac125 Yamashita, S. & al. 2021. Dietary sphingolipids contribute to health via intestinal maintenance. /International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, 7052, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22137052 Zeng, H. & Yao, N. 2022. Sphingolipids in plant immunity. Phytopathology Research 4,20, 1-19. |

3.2. Answers to Research Questions: (3) How many Species-Specific Health-Promoting Substances do Five Selected Invasive WEPs Contain? (4) How many Alzheimer’s Disease-Preventing, Species-Specific Health-Promoting Substances do these Five selected Plants Have?

3.2.1. Three Invasive Alien WEPs in Europe

Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica)

| According to Alesci & al. (2022), Wu & al. (2022), Zhu & al. (2022), Alauddin & al. (2021), Grinan-Ferre & al. (2021), Xiong & al. (2021), Kumar & al. (2020), Matsuno & al. (2020), Martínez & al. (2019) and Singh, A. & al (2019a) resveratrol has following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidant, 2) anti-inflammatory, 3) anticancer, 4) antiviral, 5) antidiabetic, 6) anti-obesity, 7) anti-metabolic syndrome, 8) cardiovascular protective, 9) antiplatelet, 10) anti-hypertension, 11) antiaging, 12) protects against neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, 13) anti-stroke, 14) nephroprotective, 15) hepatoprotective, 16) delays the progression of osteoarthritis, and 17) maintains genome stability, promoting a longer and healthier life. According to Zhua & al. (2019), resveratrol has protective effects on stress-induced depression and anxiety. They present a molecular biological mechanism for it. According to Grinan-Ferre & al. (2021), resveratrol is a powerful antioxidant and "possesses pleiotropic actions, exerting its activity through various molecular pathways." Kumar & al. (2020) state that resveratrol can cross the blood-brain barrier. Neuroinflammation is a part of Alzheimer's disease. Resveratrol prevents neuroinflammation. Alauddin, M. & al. 2021. Potential of nutraceutical in preventing the risk of cancer and metabolic syndrome: from the perspective of nutritional genomics. Cancer Plus 3(2) 1 - 18. Alesci, A. & al. 2022. Resveratrol and immune cells: A link to improve human health. Molecules 2022 27(2), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27020424 Grinan-Ferre, A. & al. 2021. The pleiotropic neuroprotective effects of resveratrol in cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease pathology: From antioxidant to epigenetic therapy. Aging Research Reviews, volume 67, article 101271, 1 – 24. Kumar, S. & al. 2020. Resveratrol, a molecule with anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities: natural product to chemical synthesis. Current Medicinal Chemistry 27, 1 – 14. Matsuno, Y. & al. 2020. Resveratrol and its related polyphenols contribute to the maintenance of genome stability. Scientific Reports, volume 10, article 5388, 1 – 10. Wu, S. & al. 2022. Effects and mechanisms of resveratrol for prevention and management of cancers: An updated review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2101428 Xiong, G. & al. 2021. Effect of resveratrol on abnormal bone remodeling and angiogenesis of subchondral bone in osteoarthritis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 14(4) 417 – 425. Zhu, H. & al. 2022. Resveratrol protects against chronic alcohol-induced liver disease in a rat model. STEMedicine 3(3), e133. https://doi.org/10.37175/stemedicine.v3i3.133 |

Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)

| phenolic acids |

For humans: According to Caruso al.& (2022), Rashmi & Negi (2020), Kumar & Goel (2019, Călinoiut & Vodnar (2018), and Szwajgier & al. (2018, phenolic acids have the following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidants, 2) anti-inflammatory, 3) antimicrobial, 4) anticancer, 5) anti-allergic, 6) antidiabetic, 7) immunoregulatory, 8) anti-thrombotic, 9) anti-atherogenic, 10) cardioprotective, 11) neuroprotective, and 12) prevent Alzheimer’s disease. In plants: According to Marchiosi & al. (2020) and Kumar & Goel (2019), phenolic acids are among plants' most widely distributed phenolic compounds. They are ubiquitous in both wild and cultured edible plants. Phenolic acids have critical biological roles. Many participate in the biosynthesis of structural components of the cell wall. Others are crucial for defence responses to pathogens and herbivores. Marchiosi & al. (2020, 893) divides simple phenolic acids into three groups: Group 1: benzoic acid and benzoic acid derivates, e.g., 1.1) benzoic acid, 1.2) gallic acid, 1.3) protocatechuic acid, 1.4) p-hydroxybenzoic acid, 1.5) salicylic acid, Group 2: cinnamic acid and cinnamic acid derivatives, e.g., 2.1) cinnamic acid, 2.2) p-coumaric acid, 2.3) caffeic acid, 2.4) ferulic acid and 2.5) sinapic acid, and Group 3: others, e.g., 3.1) catechol, 3.2) pyrogallol, and 3.3) chlorogenic acid. Caruso, G. & al. 2022. Phenolic acids and prevention of cognitive decline: polyphenols with a neuroprotective role in cognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 14, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040819 Kumar, N. & Goel, N. 2019. Phenolic acids: Natural, versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnology Reports, volume 24, article e00370, 1 – 10. Marchiosi, R. & al. 2020. Biosynthesis and metabolic actions of simple phenolic acids in plants. Phytochemistry Reviews 19, 865 –890. Rashmi, H. & Negi, P. 2020. Phenolic acids from vegetables: A review on processing stability and health benefits. Food Research International, volume 136, article 109298, 1 – 14. Szwajgier, D. & al. 2018. Phenolic acids exert anticholinesterase and cognition-improving effects. Current Alzheimer Research 15(6) 531 – 543. |

Rugosa Rose (Rosa rugosa)

Petals

Hips

| ellagitannins | According to Chen & al. (2022), García-Villalba & al. (2022), Gopalsamy & al. (2022), Al-Harbi & al. (2021), D'Amico & al. (2021), Hoseinynejad & al. (2021), Miloševic & al. (2021), Yüksel & al. (2021), Dreger & al. (2020), Li & al. (2020), Luca (2019, 17), Yoshida & al. (2018), Muthukumaran & al. (2017, 240 - 241), and Sangiovanni & al. (2013), ellagitannins have the following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidant, 2) anti-inflammatory, 3) antimicrobial, 4) antiglycative, 4) hepato-protective, 5) beneficial effects on kidney diseases, 4) anti-virus, 5) cardioprotective, 6) neuroprotective, 7) prebiotic, 8) chronic disease prevention, 7) anticancer, 8) antidiabetic, 9) beneficial effects on chronic tissue inflammation, 10) beneficial effects on metabolic syndrome) 11) beneficial effects on obesity-mediated metabolic complications, 12) beneficial effects on gastrointestinal diseases, 13) beneficial effects on eye diseases, 14) beneficial effects on depression, 15) muscle mass protective effects, and 16) beneficial effects on Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Schink & al. (2018) describe how ellagitannins prevent inflammations using molecular biology. Al-Harbi, S.& al. 2021.Urolithins: The gut-based polyphenol metabolites of ellagitannins in cancer prevention, a review. Frontiers in Nutrition, Volume 8, article 647582, 1 – 15. Chen P. & al. 2022. Recent advances and perspectives on the health benefits of urolithin b, a bioactive natural product derived from ellagitannins. Frontiers in Pharmacology 13:917266 D’Amico, D. & al. 2021. Impact of the Natural Compound Urolithin A on Health, Disease, and Aging. Trends in Molecular Medicine 27(7), 687 – 699. Dreger, M. & al. 2020. Pharmacological properties of fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium L.) and bioavailability of ellagitannins. A review. Herba Polonica 66(1), 52 – 64. García-Villalba, R. & al. 2022. Ellagitannins, urolithins, and neuroprotection: Human evidence and the possible link to the gut microbiota. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. Available online 5 August 2022, 101109. In Press, Corrected Proof. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2022.101109 Gopalsamy, R. & al. 2022. Health functions and related molecular mechanisms of ellagitannin-derived urolithins, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2106179 Li, Q. & al. 2020. Anti-renal fibrosis and anti-inflammation effect of urolithin B, ellagitannin-gut microbial-derived metabolites in unilateral ureteral obstruction rats. Journal of Functional Foods, Volume 65, article 103748, 1 – 13. Miloševic M. & al. 2021. Memorable food: Figurehting age-related neurodegeneration by precision nutrition. Frontiers in Nutrition, Volume 8, article 688086, 1 – 13. Sangiovanni, E. & al. 2013. Ellagitannins from Rubus berries for the control of gastric inflammation: in vitro and in vivo studies. PLoS ONE, Volume 8(8), article e71762, 1 – 12. Yüksel, A. & al. 2021. Phytochemical, phenolic profile, antioxidant, anticholinergic, and antibacterial properties of Epilobium angustifolium (Onagraceae). Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization. Published online 12. 7. 2021, 1 – 10. Yoshida, T & al. 2018. The chemical and biological significance of oenothein B and related ellagitannin oligomers with macrocyclic structure. Molecules, Volume 23, article 552, 1–21. |

3.2.2. Invasive Alien Species in North America

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

| isothiocyanates |

According to Ahmad & al. (2022), Kamal & al. (2022), Li & al. (2022), Kim (2021), Favela-González & al. (2020), Amron & Konsue (2018, 69), Giacoppo & al. (2015), and Agneta & al. (2013, 1935 - 1939), isothiocyanates have the following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidants, 2) antimicrobial, 3) antifungal, 4) antiviral, 5) anticancer, anticarcinogenic, 6) anti-obesity, and 7) protect against neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. According to Martelli & al. (2020, 110), isothiocyanates emerge from the enzymatic hydrolysis of glucosinolates. This enzymatic reaction happens when these plants are crunched or cut. It means that their cell walls break. The enzyme myrosinase and glucosinolates are usually in separated plant cells. After the cell walls break, myrosinase and glucosinolates come into contact. Their reaction leads to the rapid formation of isothiocyanates. Agneta, R. & al. 2013. Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), a neglected medical and condiment species with a relevant glucosinolate profile: a review. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 60(7), 1923 – 1943. Ahmad, H. & al. 2022. Derived Isothiocyanates on cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 27, 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27030624 Amron, N. & Konsue, N. 2018. Antioxidant capacity and nitrosation inhibition of cruciferous vegetable extracts. International Food Research Journal 25(1), 65 – 73. Favela-González, K. & al. 2020. The value of bioactive compounds of cruciferous vegetables (Brassica) as antimicrobials and antioxidants: A review. Journal of Food Biochemistry 44, e13414. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13414 Giacoppo, S. & al. 2015. An overview of neuroprotective effects of isothiocyanates for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Fitoterapia 106, 12-21. Kamal, R. & al. 2022. Beneficial health effects of glucosinolates-derived isothiocyanates on cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 27(3), 624; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27030624 Kim, J. 2021. Pre-Clinical Neuroprotective Evidences and Plausible Mechanisms of Sulforaphane in Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, 2929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22062929 Li, X.& al. 2022. The structure basis of phytochemicals as metabolic signals for combating obesity. Frontiers in Nutrition 9, 913883. Martelli, A. & al. 2020. Organic isothiocyanates as hydrogen sulfide donors. Antioxidants&Redox Signaling 32(2), 110 – 144. |

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

| polyphenols | According to Gasmi & al. (2022), Mitra&al. (2022), Rajha & al. (2022), Cassidy & al. (2020), Redd & al. (2020), Reed & de Frietas (2020), Srećković & al. (2020), Durazzo, & al. (2019) Gorzynik-Debicka & al. (2018) Qu&al. (2018) and Ignat & al. (2010) polyphenols have the following health-promoting properties: 1) antioxidant, 2) anti-inflammatory, 3) neuroprotective, 4) prevent Alzheimer’s disease, 5) anticancer, 6) protect the cardiovascular system, prevention of cardiovascular diseases, 7) reduce the risk of diabetes, 8) lower hypertension, 9) prevent metabolic abnormalities that may include hypertension, central obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and imbalance of lipids in the blood, 10) reduce weight in overweight and obese individuals, 11) antitumor, via anti-initiating, anti-promoting, anti-progression, and anti-angiogenesis actions, as well as by 12) modulating the immune system, participate in the immunological defense, 13) protect against oxidative damage on DNA, 14) antiallergic, 15) antimicrobial, and 16) antiviral. The biological activity of polyphenols is strongly related to their antioxidant properties. They tend to reduce the pool of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neutralize these potentially carcinogenic metabolites. Leri (2020) describes the biomolecular mechanisms of how polyphenols promote health. Mitra & al. (2022) present experimental evidence on how polyphenols synergistically promote health. According to Coman & Vodnar (2020, 483), over 8000 plant polyphenols are known in plants. According to Šamec & al. (2021), Singhet & al. (2021), and Marranzano & al. (2018), all higher land plants have polyphenols 1) against abiotic stressors, extreme temperatures, drought, flood, light, UV radiation, salt, and heavy metals. Some polyphenols protect plants against biotic stressors, e.g., 2) against herbivores (plant-eating insects and other animals. 3) against micro-organisms. Polyphenolic compounds against abiotic and biotic stressors include phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenoids, and lignans. Some polyphenols participate in 4) plant growth and 5) plant development. According to Åhlberg (2021), all wild edible plants have polyphenols. Cassidy, L. & al. 2020. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: a review on emergent natural polyphenolic therapeutics. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, volume 49, article 102294, 1 – 11. Gasmi, A. & al. 2022. Polyphenols in metabolic diseases. Molecules 27(19), 6280; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196280 Leri, M. 2020. Beneficial effects of plant polyphenols: molecular mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, volume 21, article 1250, 1 – 40. Marranzano, M.& al. 2018. Polyphenols: plant sources and food industry applications. Current Pharmaceutical Design 24, 4125 – 4130. Mitra, S. & al. 2022. Polyphenols: A first evidence in the synergism and bioactivities. Food Reviews International. Published online: 24 Jan 2022. DOI: 10.1080/87559129.2022.2026376 Redd, P. & al. 2020. Polyphenols are present in Alzheimer’s disease and the gut–brain axis. Microorganisms 8, 19. Reed, J. & de Freitas, V. 2020. Polyphenol chemistry: implications for nutrition, health, and the environment. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 68(10), 2833–2835. Rajha, H. & al. 2022. Recent advances in research on polyphenols: effects on microbiota, metabolism, and health. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 66, 210067. Šamec, D. & al. 2021. The role of polyphenols in abiotic stress response: The influence of molecular structure. Plants, volume 10, article 118, 1 - 24. Singh, S. & al. 2021. The multifunctional roles of polyphenols in plant-herbivore interactions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, volume 22, article 1442, 1 – 20. Srećković, N. & al. 2020. Lythrum salicaria L. (Lythraceae) as a promising source of phenolic compounds in the modulation of oxidative stress: Comparison between aerial parts and root extracts. Industrial Crops and Products 155, 112781. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Åhlberg, M. K. (2019). Totuus syötävistä luonnonkasveista eli miksi uskallan syödä lähiluonnon kasveista kestävästi keräämääni ruokaa: OSA I: Tieteellisiä perusteita käytännönläheisesti. (Translated title of the contribution: The truth about wild edible plants - why I am not afraid of eating food that I have made about plants from the local nature that I have foraged sustainably.) Helsinki: Eepinen Oy.

- Åhlberg, M. K. (2020a). Local Wild Edible Plants (WEP). Practical conclusions from the latest research: Healthy food from local nature. Helsinki: Oy Wild Edibles Ab. International distribution: Amazon.com.

- Åhlberg, M. K. (2020b). Field guide to local Wild Edible Plants (WEP): Practical conclusions from the latest research: Healthy food from local nature. Helsinki: Oy Wild Edibles Ab. International distribution: Amazon.com.

- Åhlberg, M. K. (2021). A profound explanation of why eating green (wild) edible plants promotes health and longevity. Food Frontiers, 2(3), 240– 267. [CrossRef]

- Åhlberg, M. K. (2022a). Terveyttä lähiluonnosta [Health from local nature]. Helsinki: Readme.fi. (The book presents 75 common WEPs with scientific names. Their health-promoting substances are in English.).

- Åhlberg, M. K. (2022b). An update of Åhlberg (2021a): A profound explanation of why eating green (wild) edible plants promotes health and longevity. Food Frontiers 3(3), 366-379. [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A. (2019). Chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Lythrum salicaria- A Review. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy 9(6), 51-59.

- Al-Yafeai, A., & al. (2018). Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of Rosa rugosa depend on the degree of ripeness. Antioxidants 7, 134. [CrossRef]

- Anžlovar, S., & al. 2020. The effect of extracts and essential oil from invasive Solidago spp. and Fallopia japonica on crop-borne fungi and wheat germination. Food Technology and Biotechnology 58(3), 273 – 283. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Rico, J. & al. (2020). Study of Edible Plants: Effects of Boiling on Nutritional, Antioxidant, and Physicochemical Properties. Foods 9(5), 599. [CrossRef]

- Arrington, A. (2021). Urban foraging of five non-native plants in NYC: Balancing ecosystem services and invasive species management. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 58(1), 126896. [CrossRef]

- Arrozi, A., & al. (2022). Alpha- and gamma-tocopherol modulates the amyloidogenic pathway of amyloid precursor protein in vitro model of Alzheimer’s Disease: A transcriptional study. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 16, 846459. [CrossRef]

- Becker, H., & al. (2015). Bioactivity guided isolation of antimicrobial compounds from Lythrum salicaria. Fitoterapia 76(6), 580-584. [CrossRef]

- Bencsik, T., & al. (2011). Variability of total flavonoid, polyphenol and tannin contents in some Lythrum salicaria populations. Natural Product Communications 6(10), 1417 – 1420. Vol. 6 No. 10 1417 – 1420. [CrossRef]

- Blaevi, I., & Masteli, J. (2008). Free and bound volatiles of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Croatica Chemica Acta 81(4), 607-613.

- Blazevic, I., & Mastelic, J. (2008). Free and bound volatiles of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Croatica Chemica Acta 81 (4) 607-613.

- Blossey, B., & al. (2001). Developing biological control of Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara and Grande (garlic mustard). Natural Areas Journal 21(4), 357-367.

- Cámara, M., & al. (2016). Wild edible plants as sources of carotenoids, fibre, phenolics, and other non-nutrient bioactive compounds. In de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M., & Tardío, J. (Eds.) Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. ethnobotany and Food Composition Tables. New York: Springer, 187 – 205.

- Capurso, A. (2024) The Mediterranean diet: A historical perspective. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 36:78. [CrossRef]

- Cavers, P., & al. (1979). The biology of Canadian weeds 35. Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara and Grande. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 59, 217-229. [CrossRef]

- Cendrowski, A., & al. (2017). Profile of the phenolic compounds of Rosa rugosa petals. Journal of Food Quality 2017, 7941347. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., & al. (2022). Fallopia Japonica and Prunella vulgaris inhibit myopia progression by suppressing AKT and NFκB mediated inflammatory reactions. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 22, 5. [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E., & al. (2023). Natural functional foods as a part of the Mediterranean lifestyle and their association with psychological resilience and other health-related parameters. Applied Sciences, 13(7), 4076. [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A., & al. (2016). Glanduliferins A and B, two new glucosylated steroids from Impatiens glandulifera, with in vitro growth inhibitory activity in human cancer cells. Fitoterapia 109, 138-145. [CrossRef]

- Coakley, S., & Petti, C. (2021). Impacts of the invasive Impatiens glandulifera: Lessons learned from one of Europe’s top invasive species. Biology 10, 619. [CrossRef]

- Cucu, A., & al. (2021). New approaches on Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) bioactive compounds and their potential of pharmacological and beekeeping activities: Challenges and future directions. Plants 10, 2621. [CrossRef]

- Cunja, V., & al. (2016). Fresh from the ornamental garden: Hips of selected rose cultivars rich in phytonutrients. Journal of Food Science 81(2), C369-C379. [CrossRef]

- Dashbaldan, S., & al. (2021). Distribution of triterpenoids and steroids in developing rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb.) accessory fruit. Molecules 26, 5158. [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, E., & al. (2023). Membrane lipid remodeling modulates γ-secretase processivity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 299(4), 103027. [CrossRef]

- de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M., & Tardío, J. (Eds.) (2016) Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. ethnobotany and Food Composition Tables. New York: Springer.

- DeRango-Adem, E. & Blay, J. 2021. Does oral apigenin have real potential for a therapeutic effect in the context of human gastrointestinal and other cancers? Frontiers in Pharmacology 12, 681477. [CrossRef]

- Dinică, R., & al. (2010). Quantitative determination of polyphenol compounds from raw extracts of Allium, Alliaria, and Urtica genus. A comparative study. Journal of Faculty of Food Engineering, Ştefan cel Mare University – Suceava 9(4), 85 – 89.

- Dobreva, A., & Nedeltcheva-Antonova, D. (2023). Comparative chemical profiling and citronellol enantiomers distribution of industrial type rose oils produced in China. Molecules 28, 1281. [CrossRef]

- Dobson, H, & al. (1990). Differences in fragrance chemistry between flower parts of Rosa rugosa Thunb. (Rosaceae). Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 39(1-2), 143-156.

- Dong, N., & Lin, H. (2021). Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 63(1), 180-209. [CrossRef]

- Dourado, N, & al. (2020). Neuroimmunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects of the flavonoid apigenin in vitro models of neuroinflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 12, 119. [CrossRef]

- Egebjerg, M. & al. 2018. Are wild and cultivated flowers served in restaurants or sold by local producers in Denmark safe for the consumer? Food and Chemical Toxicology 120, 129-142. [CrossRef]

- EU CONTAM (2017). Scientific opinion: Erucic acid in feed and food. EFSA Journal 2016;14(11):4593. The scientific opinion was adopted: On 21.9.2016, and the amended version was readopted on 5.4.2017.

- European Commission (2022a). Invasive alien species. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/invasivealien/list/index_en.htm.

- European Commission (2022b). Annex. List of invasive alien species of Union concern. Retrieved 10.2.2023, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02016R1141-20220802etfrom=EN.

- Feng, L, & al. (2014). Flowery odor formation revealed by differential expression of monoterpene biosynthetic genes and monoterpene accumulation in rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb.). Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 75, 80-88. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M., & al. (1958). Edible wild plants of eastern North America. New York: Harper & Row.

- Frisch, T., & al. (2015). Diversified glucosinolate metabolism: Biosynthesis of hydrogen cyanide and the hydroxynitrile glucoside alliarinoside in relation to sinigrin metabolism in Alliaria petiolata. Frontiers in Plant Science, 31. [CrossRef]

- Galanty, A., & al. (2023). Erucic acid—Both sides of the story: A concise review on its beneficial and toxic properties. Molecules 28(4), 1924. [CrossRef]

- GBIF (2023). The distribution map of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is based on museum data and observations (538,402 occurrences). Retrieved 26.5.2023 from https://www.gbif.org/species/3188736.

- Girardi, J., & al. (2022). Nitrification inhibition by polyphenols from invasive Fallopia japonica under copper stress. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 185, 923–934. [CrossRef]

- Goya, A., & al. (2023). Erucic acid: A possible therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative diseases. Current Molecular Medicine published online 9.5.2023. [CrossRef]

- Grieve, M. (1959). A modern herbal. Volume 2. New York: Hafner Publishing.

- Guo, Y., & al. (2023). Recent advances in the medical applications of hemostatic materials. Theranostics 13(1): 161-196. [CrossRef]

- Haribal, M., & Renwick, J. (2001). Seasonal and population variation in flavonoid and alliarinoside content of Alliaria petiolata. Journal of Chemical Ecology 27, 1585–1594. [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.,&al. (2022). Effects of intraspecific density and plant size on garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) sinigrin concentration. Biological Invasions 24, 3785–3797. [CrossRef]

- Hoover, A., & Wijesinha, G. (1945). Influence of pH and salts on the solubility of calcium oxalate. Nature 155, 638. [CrossRef]

- Iancu, I., & al. (2021). Phytochemical evaluation and cytotoxicity assay of Lythri herba extracts. Farmacia 69(1), 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T., & al. (2023). Catching the green - diversity of ruderal spring plants traditionally consumed in Bulgaria and their potential benefit for human health. Diversity 15, 435. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B., & al. (2015). Chemical constituents from Lythrum salicaria L. Journal of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences 50(14), 1190-119.

- Jordan, D. (2023). Eat the weeds: A forager’s guide to identifying and harvesting 274 wild foods. Cambridge, MN: Adventure Publications.

- Kalemba-Drożdż, M., & Ciernia, A. (2018). Antioxidant and genoprotective properties of extracts from edible flowers. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 58(1), 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Kallas, J., (2023). Wild edible plants. Wild foods from foraging to feasting. Layton: Gibbs Smith.

- Kanmaz, O., & al. (2023). A modeling framework to frame a biological invasion: Impatiens glandulifera in North America. Plants 12(7), 1433. [CrossRef]

- National list of harmful invasive alien species. (2023). Retrieved June 20, 2023, from Invasive Alien Species – Invasive Alien Species Portal (vieraslajit.fi).

- Katekar, V., & al. 2022. Review of the rose essential oil extraction by hydrodistillation: An investigation for the optimum operating condition for maximum yield. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 29, 100783. [CrossRef]

- Kayahan, S., & al. (2022). Functional compounds and antioxidant activity of Rosa species grown in Turkey. Erwerbs-Obstbau, published online June 14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ke, J., & al. (2023). Advances for pharmacological activities of Polygonum cuspidatum - A review. Pharmaceutical Biology 61(1), 177-188. [CrossRef]

- Kelager, A., & al. (2013). Multiple introductions and no loss of genetic diversity: Invasion history of Japanese Rose, Rosa rugosa, in Europe. Biological Invasions 15, 1125–1141. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., & al. (2016). The memory-enhancing effect of erucic acid on scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 142, 85-90. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., & al. (2022). Variations in the antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties of different Rosa rugosa organ extracts. Agronomy 12, 238. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. (2020). Metabolism in plants. Plants 9(7), 871, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & al. (2022). Analysis of components in the different parts of Lythrum salicaria L.

- Journal of the Korean Herbal Medicine Society 37(5), 89-96.

- Kim, M., & al. (2019). The natural plant flavonoid apigenin is a strong antioxidant that effectively delays peripheral neurodegenerative processes. Anatomical Science International 94, 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & al. (2020). Allyl isothiocyanate protects acetaminophen-induced liver injury via NRF2 activation by decreasing spontaneous degradation in hepatocyte. Nutrients 12, 3585. [CrossRef]

- Klewicka, E., & al. (2022). Antagonistic activity of lactic acid bacteria and Rosa rugosa Thunb. pseudo-fruit extracts against Staphylococcus spp. strains. Applied Science 12, 4005. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, D., & Chen, G. (2021). The invasive species Alliaria petiolata threatens forest understories as it alters soil nutrients and microbial composition, thereby changing the local plant community. Journal of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science (2020) 94(1-2): 73–90. [CrossRef]

- Kurita, D., & al. (2016). Identification of neochlorogenic acid as the predominant antioxidant in Polygonum cuspidatum leaves. Italian Journal of Food Science 28, 25 – 31. [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, S., & al. (2019). UPLC-PDA-Q/TOF-MS identification of bioactive compounds and on-line UPLC-ABTS assay in Fallopia japonica Houtt and Fallopia sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) leaves and rhizomes grown in Poland. European Food Research and Technology 245, 691–706. [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, S., & Oszmiański, J. (2019). Profile of bioactive compounds in the morphological parts of wild Fallopia japonica (Houtt) and Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) and their antioxidative activity. Molecules 24(7), 1436. [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, S., & Oszmiański, J. (2019). Profile of bioactive compounds in the morphological parts of wild Fallopia japonica (Houtt) and Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) and their antioxidative activity. Molecules 24(7), 1436. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. & Wang, C. (2018). Medicinal components and pharmacological effects of Rosa rugosa. Records of Natural Products 12(6), 535-543. [CrossRef]

- Lupoae, M., & al. (2010). Quantification of carotenoids and chlorophyll leaf pigments from autochthones dietary. Food and Environment Safety - Journal of Faculty of Food Engineering, Ştefan cel Mare University – Suceava 9(4), 42 – 47.

- Maciąg, A., & Kalemba, D. 2015. Composition of rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb.) hydrolate according to the time of distillation. Phytochemistry Letters 11, 373-377. [CrossRef]

- Manjiro K., & al. 2008. Effects of Rosa rugosa petals on intestinal bacteria. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 72(3), 773-777. [CrossRef]

- Manayi, A., & al. (2013). Cytotoxic effect of the main compounds of Lythrum salicaria L. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 68(9-10), 367-375.

- Manayi, A., & al. (2014). Comparative study of the essential oil and hydrolate composition of Lythrum salicaria L. obtained by hydro-distillation and microwave distillation methods. Research Journal of Pharmacognosy 1(2), 33-38.

- Marrelli, A., & al. (2020). A review of biologically active natural products from Mediterranean wild edible plants: Benefits in the treatment of obesity and its related disorders. Molecules 25(3), 649. [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. & Touaibia, M. 2020. Improvement of testicular steroidogenesis using flavonoids and isoflavonoids for prevention of late-onset male hypogonadism. Antioxidants, volume 9, article 237, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Medveckienė, B.,&al. (2022). Effect of harvesting in different ripening stages on the content of the mineral elements of rosehip (Rosa spp.) fruit flesh. Horticulturae 8(6), 467. [CrossRef]

- Medveckienė, B.,&al. (2023). Changes in pomological and physical parameters in rosehips during ripening. Plants 12(6), 1314. [CrossRef]

- Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.,&al. (2022). HPLC-DAD-MS identification and quantification of phenolic components in Japanese knotweed and American pokeweed extracts and their phytotoxic effect on seed germination. Plants 2022, 11, 3053. [CrossRef]

- Milala, J.,&al. (2021). Rosa spp. extracts as a factor that limits the growth of Staphylococcus spp. bacteria, a food contaminant. Molecules 26, 4590. [CrossRef]

- Milanović, M.,&al. (2020). Linking traits of invasive plants with ecosystem services and disservices. Ecosystem Services 42, 101072. [CrossRef]

- Mira, S., & al. (2019). Lipid thermal fingerprints of long-term stored seeds of Brassicaceae. Plants 8, 414. [CrossRef]

- Molgaar, P. (1986). Food plant preferences by slugs and snails: A simple method to evaluate the relative palatability of the food plants. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 14(1), 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Monari, S., & al. (2021). Phytochemical characterization of raw and cooked traditionally consumed alimurgic plants. PLoS ONE 16(8): e0256703. [CrossRef]

- Motti, R., & al. (2022). Edible flowers used in some countries of the Mediterranean basin: An ethnobotanical overview. Plants (Basel) 11(23), 3272. [CrossRef]

- Nattagh-Eshtivani, E., & al. (2022). Biological and pharmacological effects and nutritional impact of phytosterols: A comprehensive review. Phytotherapy Research, 36, 299–322. [CrossRef]

- Ng, T., & al. (2005) Rose (Rosa rugosa) - flower extract increases the activities of antioxidant enzymes and their gene expression and reduces lipid peroxidation. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 83(1), 78-85. [CrossRef]

- Nijat, D., & al. (2021) Spectrum-effect relationship between UPLC fingerprints and antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of Rosa rugosa. Journal of Chromatography B 1179, 122843. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R. (2005) Chemical composition of hips essential oils of some Rosa L. species. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 60(5-6), 369-378. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R. (2006) Determination of ellagic acid in pseudofruits of some species of roses. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica - Drug Research 63(4),289-292.

- Nowak, R., & al. 2014. Cytotoxic, antioxidant, antimicrobial properties and chemical composition of rose petals. The Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 94(3), 560-567. [CrossRef]

- Olech, M., & al. (2017). Multidirectional characterisation of chemical composition and health-promoting potential of Rosa rugosa hips. Natural Product Research, 31(6), 667–671. [CrossRef]

- Olech, M., & al. (2019). Polysaccharide-rich fractions from Rosa rugosa Thunb. —Composition and chemopreventive potential. Molecules, 24(7), 1354. [CrossRef]

- Olech, M., & al. (2023). Novel polysaccharide and polysaccharide-peptide conjugate from Rosa rugosa Thunb. pseudofruit – Structural characterisation and nutraceutical potential. Food Chemistry, 409, 135264. [CrossRef]

- Orzelska-Górka, J., & al. (2019). Monoaminergic system is implicated in the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside and protocatechuic acid isolated from Impatiens glandulifera Royle in mice. Neurochemistry International 128, 206-214. [CrossRef]

- Paura, B., & Marzio, P. (2022). Making a virtue of necessity: The use of wild edible plant species (also toxic) in bread making in times of famine according to Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1766). Biology, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Pirvu, L., & al. (2014). Comparative studies on analytical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of a series of vegetal extracts prepared from eight plant species growing in Romania. Journal of Planar Chromatography 27(5), 346–356. [CrossRef]

- Piwowarski, J., & al. (2015). Lythrum salicaria L.—Underestimated medicinal plant from European traditional medicine. A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 170, 226-250. [CrossRef]

- Prdun, S., & al. (2022). Characterization of rare Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera Royle) honey from Croatia. Foods, 11(19), 3025. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., & al. (2018). Brassicaceae mustards: Traditional and agronomic uses in Australia and New Zealand. Molecules, 23(1), 231. [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M., & al. (2022). Rosa davurica Pall., Rosa rugosa Thumb., and Rosa acicularis Lindl. Originating from Far Eastern Russia: Screening of 146 Chemical Constituents in Three Species of the Genus Rosa. Applied Sciences, 12, 9401. h.

- Repsold, B., & al. (2018). Multi-targeted directed ligands for Alzheimer’s disease: Design of novel lead coumarin conjugates. SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research 29(3), 231-255. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, V., & al. (2022). Where Is garlic mustard? Understanding the ecological context for invasions of Alliaria petiolate. BioScience, 72(6), 521–537. [CrossRef]

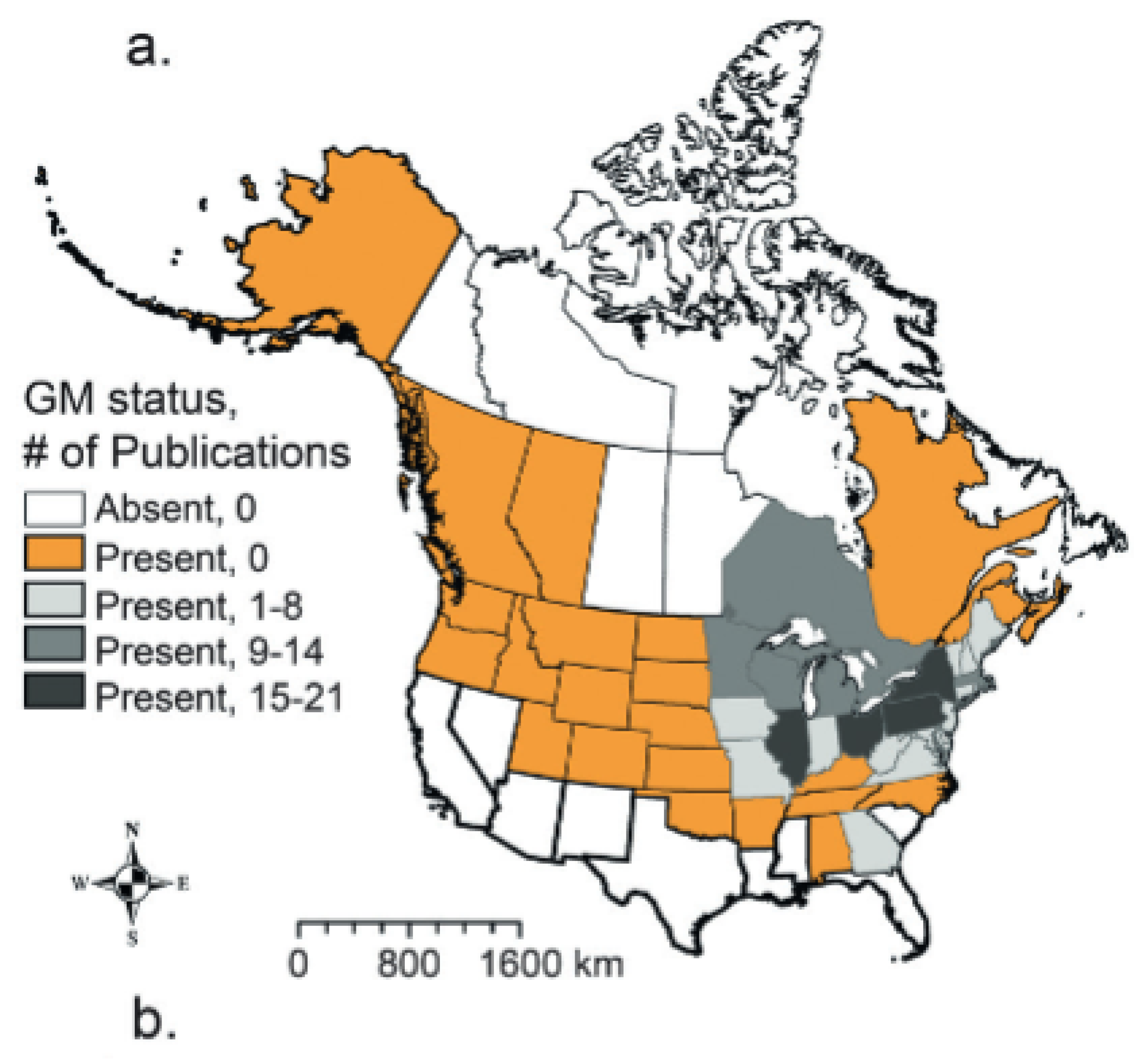

- Rogers, J., & al. (2022). Mapping the purple menace: Spatiotemporal distribution of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) along roadsides in northern New York State. Scientific Reports, 12, 5270. [CrossRef]

- Sajna, N. 2017. Habitat preference within its native range and allelopathy of garlic mustard Alliaria petiolata. Polish Journal of Ecology, 65(1), 46-56. [CrossRef]

- Salo, M., & al. (2023). Diagnosing wild species harvest - resource use and conservation. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Seal, T. & al. (2023). Effect of cooking methods on total phenolics and antioxidant activity of selected wild edible plants. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 15(7), 20 -26. [CrossRef]

- Sergio, L. & al. (2020). Bioactive phenolics and antioxidant capacity of some wild edible greens as affected by different cooking treatments. Foods 9(9), 1320. [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y. & al. (2022). An in-silico approach to studying a very rare neurodegenerative disease using a disease with higher prevalence with shared pathways and genes: Cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 15, 99669. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K., & Gairola, S. (2023). Nutritional potential of wild edible rose hips in India for food security. In A. Kumar & al. (Eds.), Agriculture, Plant Life and Environment Dynamics (pp. 163–179). Springer, Singapore.

- Sirše, M. (2022). Effect of dietary polyphenols on osteoarthritis—Molecular mechanisms. Life, 12, 436. [CrossRef]

- Skrypnik, L., &al. (2019). Evaluation of the rose hips of Rosa canina L. and Rosa rugosa Thunb. as a valuable source of biological active compounds and antioxidants on the Baltic Sea coast. Polish Journal of Natural Sciences, 34(3), 395–413.

- Srećković, N., & al. (2020). Lythrum salicaria L. (Lythraceae) as a promising source of phenolic compounds in the modulation of oxidative stress: Comparison between aerial parts and root extracts. Industrial Crops & Products 155, 112781. [CrossRef]

- Stuper-Szablewska, K., & al. (2023). Antimicrobial activities evaluation and phytochemical screening of some selected plant materials used in traditional medicine. Molecules, 28(1), 244. [CrossRef]

- Sulborska, A., & al. 2012. Micromorphology of Rosa rugosa Thunb. petal epidermis secreting fragrant substances. Acta Agrobotanica 65 (4), 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Šutovská, M. & al. (2012). Antitussive and bronchodilatory effects of Lythrum salicaria polysaccharide-polyphenolic conjugate. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 51(5), 794-799. [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K., & al. (2016). Comparison of the essential oil composition of selected Impatiens species and its antioxidant activities. Molecules, 21(9), 1162. [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K., & Olech, M. (2017). Optimization of extraction method for LC–MS based determination of phenolic acid profiles in different Impatiens species. Phytochemistry Letters, 20, 322–330. [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K., & al. (2018). Lipophilic components and evaluation of the cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of Impatiens glandulifera Royle and Impatiens noli – tangere L. (Balsaminaceae). Grasas y Aceites, 69(3). [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk. K., & al. (2019a). Comparison of the essential oil composition of selected Impatiens species and its antioxidant activities. Molecules 21,1162. [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K., & al. (2019b). SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL: Phenolic constituents of the aerial parts of Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae) and their antioxidant activities. Natural Product Research, 33(19). [CrossRef]

- Şöhretoğlu, D., & al. (2018). Recent advances in chemistry, therapeutic properties and sources of polydatin. Phytochemistry Reviews, 17, 973–1005. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A., & al. (2021). Erucic acid-rich yellow mustard oil improves insulin resistance in KK-Ay mice. Molecules 26(3), 546. [CrossRef]

- Tallberg, S., & al. 2023. The forager’s cookbook Flora. Helsinki: Superluonnollinen Oy.

- Thakur, M., & al. (2020). Phytochemicals: Extraction process, safety assessment, toxicological evaluations, and regulatory issues. In B. Prakash (Ed.), Functional and Preservative properties of Phytochemicals (pp. 341-361). Academic Press.

- The Local Food-Nutraceuticals Consortium. (2005). Understanding local Mediterranean diets: A multidisciplinary pharmacological and ethnobotanical approach. Pharmacological Research 52 (2005) 353–366. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X., & al. (2019). Effects of antibiotics on nitrogen uptake of four wetland plant species grown under hydroponic culture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 10621–10630. [CrossRef]

- Tunalier, Z., & al. (2007). Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive activities and composition of Lythrum salicaria L. extracts. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 110(3-4), 539-547. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M., & al. (2006). Flavonoids from the flowers of Impatiens glandulifera Royle isolated by high-performance countercurrent chromatography. Phytochemical Analysis, 27(2), 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & al. (2022). Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of medicinal plants from Rosa genus. Chinese Herbal Medicines, 14(2), 187-209. [CrossRef]

- Wens, A. & Geuens, J. 2022. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of plant extracts against common phytopathogenic fungi. Journal of Bioscience and Biotechnology 11(1), 15-21.

- WFO (2023): World Flora Online. Published on the Internet; http://www.worldfloraonline.org. Accessed on: 27 May 2023.

- Wu, X., & al. (2009). Are isothiocyanates potential anti-cancer drugs? Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 30, 501–512. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., & Colautti, R. (2022). Evidence for continent-wide convergent evolution and stasis throughout 150 y of a biological invasion. Proceedi¬ngs of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(18), e2107584119. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.,&al. (2022). Chemical compounds, anti-aging and antibacterial properties of Rosa rugosa purple branch. Industrial Crops & Products, 181, 114814. [CrossRef]

- Zennie, T., & Ogzewalla, D. (1977). Ascorbic acid and vitamin A content of edible wild plants of Ohio and Kentucky. Economic Botany 36, 78-79. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., & al. (2019). Purification, characterization, antioxidant and moisture-preserving activities of polysaccharides from Rosa rugosa petals. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 124, 938-945. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & al. (2022). Novel functional food from an invasive species Polygonum cuspidatum: Safety evaluation, chemical composition, and hepatoprotective effects. Food Quality and Safety, 6, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., & al. (2023). Road to a bite of rosehip: A comprehensive review of bioactive compounds, biological activities, and industrial applications of fruits. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 136, 76-91. [CrossRef]

| WEP species, aerial parts | Total number of health-promoting substances |

| Rosa rugosa petals | 194 |

| Rosa rugosa hips | 164 |

| Lythrum salicaria | 161 |

| Fallopia japonica | 141 |

| Impatiens glandulifera | 136 |

| Alliaria petiolata | 100 |

| WEP species | the number of substances in the aerial parts preventing Alzheimer’s disease |

| Fallopia japonica | 57 |

| Impatiens glandulifera | 46 |

| Lythrum salicaria | 41 |

| Rosa rugosa hips | 39 |

| Rosa rugosa petals | 35 |

| Alliaria petiolata | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).