This research was conducted using the framework of the PHE concept as a scientific foundation, governing the selection of the data sources as well as data synthesis, analysis, and interpretation. In plain language, the data analysis had been performed based on hydrogen’s elementary physical and chemical properties.

2.1. Paleotectonic, Geodynamic and Structural Setting

Deep-reaching structural features such as faults, strike-slips and thrust faults, are suggested as probable natural hydrogen degassing conduits (V. Vidavskiy, R. Rezaee, 2022). In this regard, the area of interest was studied through the prism of the modern tectonic activity related to the major structural elements. Several areas corresponding to the potential structures a.k.a. “chimneys” conducting hydrogen to the near-surface, were preliminarily identified as being likely to be prospective.

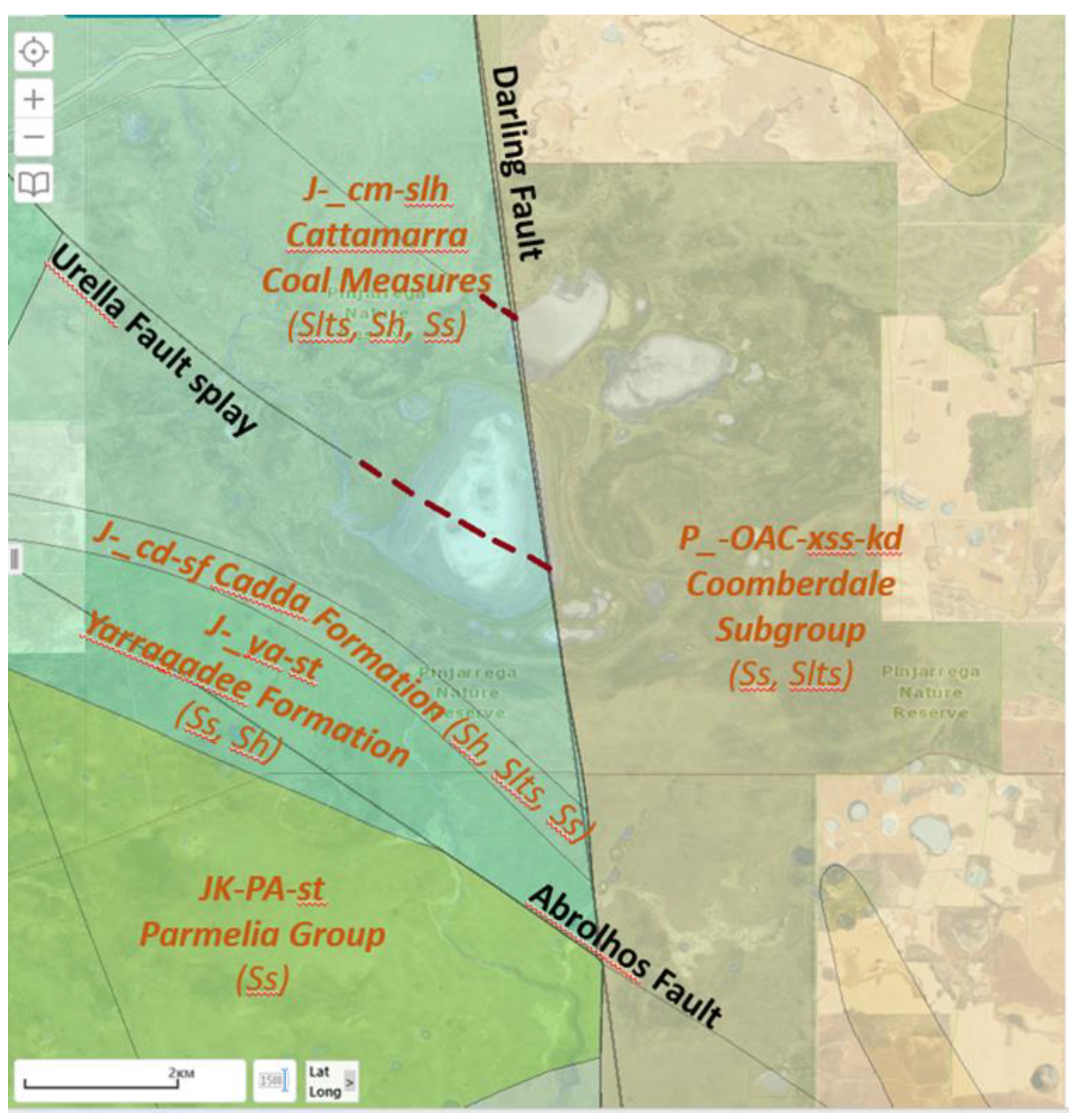

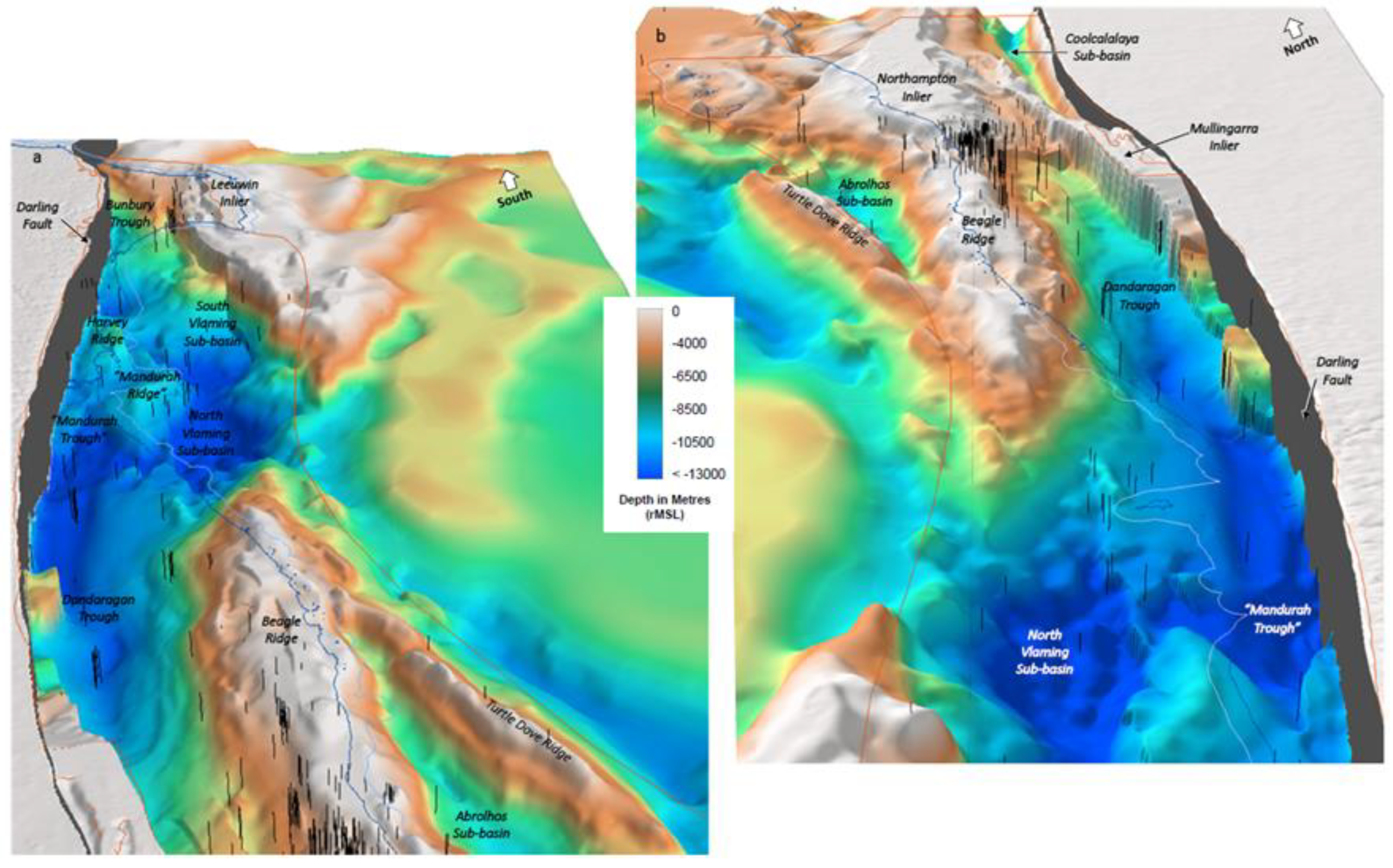

The AOI is located in Western Australia, along the Darling Fault N-NE Perth, covering the western flank of the Northern Perth Basin and the east-most margin of the Yilgarn Craton (

Figure 2).

The local geology appears to have been studied in much detail by several generations of researchers. From the petrology and lithology viewpoints, formations to the east of the Darling Fault are represented by a series of granitoids and greenstone belts of the Yilgarn Craton (

Figure 3), while the western flank is formed by sedimentary sequences of the Perth Basin, of the Permian through Cretaceous ages.

In terms of tectonic setting, this area is represented by a typical cratonic margin environment, transiting to a sedimentary basin through a series of asymmetric NW-SE striking normal faults, with quite steep dips and deep throws (

Figure 4), indicating that the major faults forming the structural network may detach at greater depths within the basement (A. J. Mory & Iasky, 1996). In the area of research, these faults dip in the W – NW – SW direction.

The Darling Fault is the dominating structural element, extending in the general N-S direction for over 1,100 km and separating the Yilgarn Craton from the Perth Basin. Darling Fault is traced to the deep layers of the crust, possibly extending through the Moho into the top lithospheric mantle, approximately at depths about 38-40 km within the area of research. At a depth of about 6km to 7km below the surface, the Proto-Darling Fault structure was identified, being characterized by a zone of poor to no seismic reflection (M. Middleton, Wilde, Evans, Long, & Dentith, 1993).

On the Perth Basin flank to the west of the Darling fault, the Urella (N Moora) and the Muchea (S Moora) oblique faults (effectively half-grabens) form the Irwin and the Barberton terraces, correspondingly. The Dandaragan Trough is located to the west of Moora, contacting with the Moora Group to the east, on the Eastern (craton) flank of the Darling fault, with the latter forming a volcanic–clastic-carbonate shelf-platform sequence (Wilde, Nelson, Australia, & Resources, 2001).

The development history of the Perth Basin comprises at least three extension events, followed by the post-rifting sedimentation cycles (Song & Cawood, 2000). The earliest rifting event took place in the Early Permian (ca. 290Ma) and finally resulted in the early Cretaceous (132-140Ma) Gondwana breakup (Arthur Mory, Haig, Mcloughlin, & Hocking, 2005) followed by the Greater India sub-continent departure from the WAC - Western Australian cratonic agglomerate.

The comprehensive Perth Basin tectonic structures development synthesis was presented by Harris (Harris, 1994). According to this research, the system experienced a series of extensional and compressional cycles, alternated by both dextral and sinistral transpressional and transtensional events of a complex geometry.

Some researchers (Newport, 2020) believe that the rifting processes are still ongoing in the area (M. C. Dentith, Bruner, Long, Middleton, & Scott, 1993), while others directly compare the Darling Fault – Perth Basin structure with the San Andreas fault in California, the USA (M Dentith, Long, Scott, & Bruner, 1994; Hoskin, Regenauer-Lieb, & Jones, 2015; Rezaee, 2020)(Rezaee, 2021).

In summary, the Darling Fault (paleo)tectonic situation and structural setup allow making several assumptions:

The Darling Fault runs very deep into the lower crust and is likely to communicate directly with the top of the lithospheric mantle;

The Darling Fault's rifting history accounts for several re-activation cycles, one of which eventually resulted in the Greater India breakup and departure;

There might be evidence that nowadays, the Darling Fault is not entirely quiescent, experiencing certain structural activity of strike-slip nature along its extent.

In regards to the driving forces behind this tectonic activity, there are a number of opinions among the research groups. We tend to support the views expressed by (Hoskin, Regenauer-lieb, et al., 2015) (

Figure 5 and

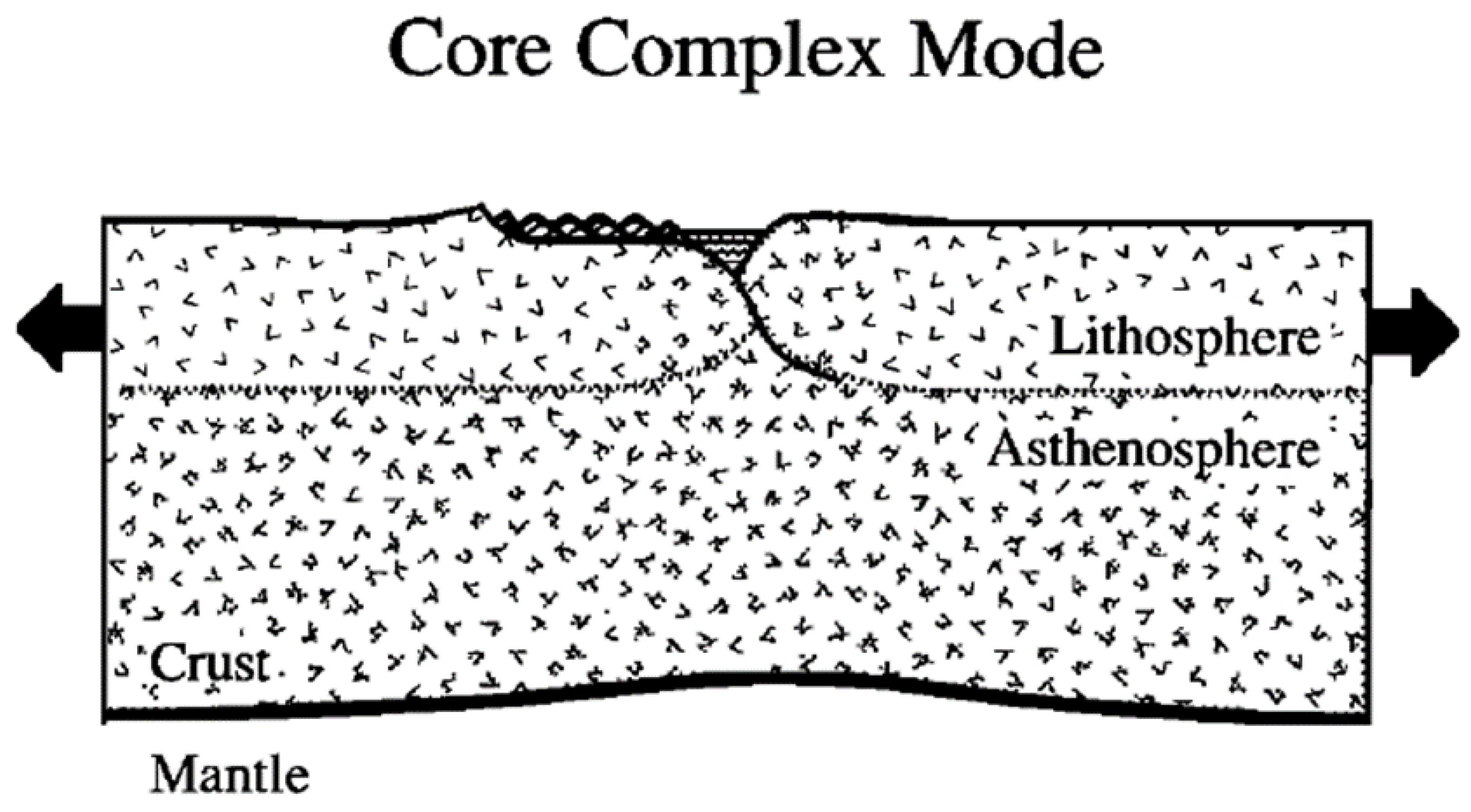

Figure 7) stipulating that the development model for the Darling Fault zone, or DFZ, is best explained by the asymmetric graben structure, a.k.a. “

core complex” (

Figure 6) according to W. R. Buck (Buck, 1991). Interestingly, the latter researcher formalized the conditions necessary for such structure development as resulting “from extension at high strain state over a narrow [<100km wide] region”.

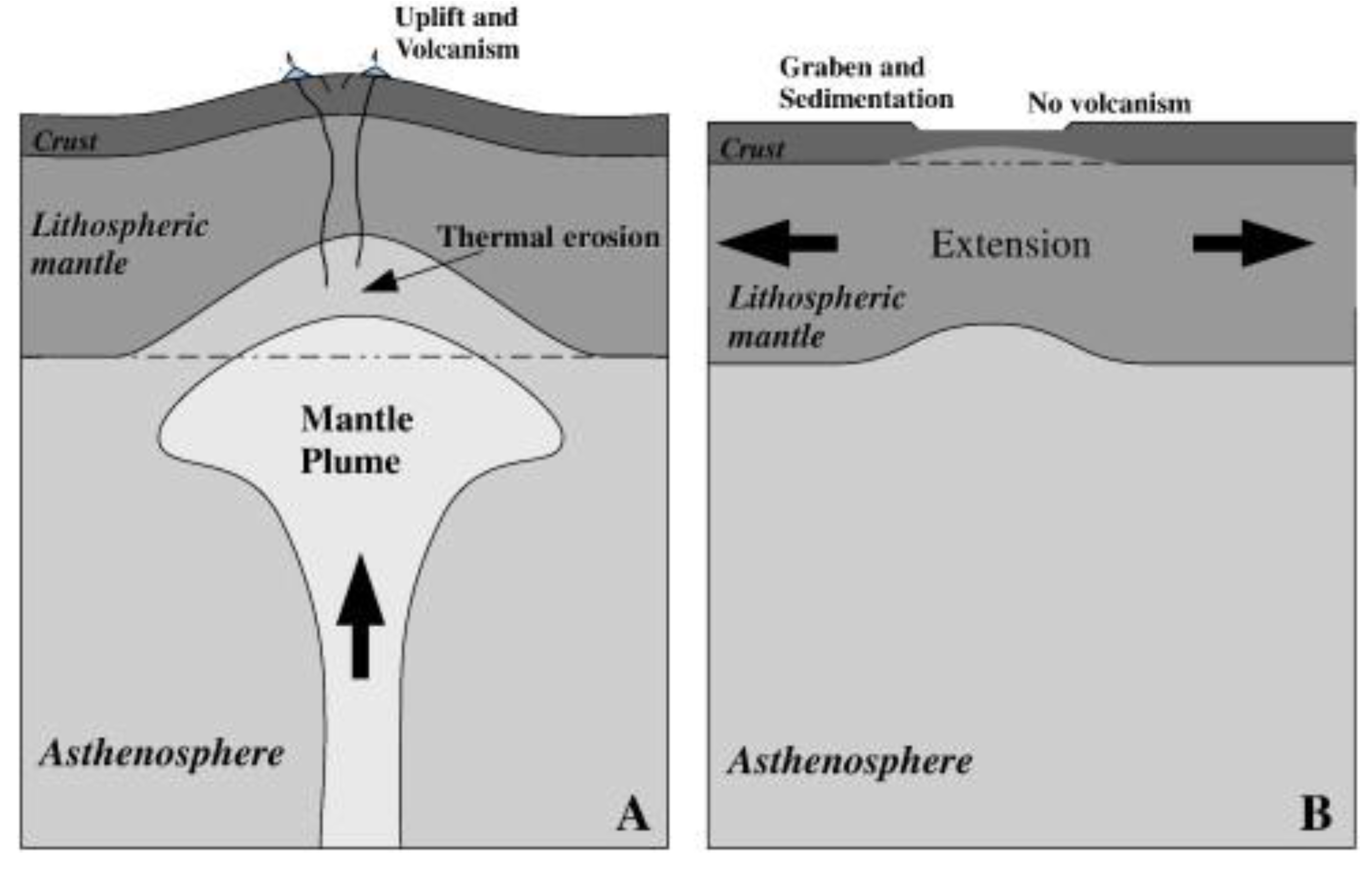

This crustal structure development mode also corresponds to the “passive” rifting classification (

Figure 7) by Merle (Merle, 2011), who attributed the lithospheric structures’ extension to the regional stresses located within the lithosphere, i.e., not involving any mantle “plume” upwelling – as opposed to the “active” rifting requiring such deep activity. Such a “passive” rifting process was dubbed as “lithosphere-activated” by Condie (Condie, 1982).

However, neither of the researchers cited above seems to be able to come up with an explanation of a mechanism that could possibly drive such powerful pulling forces behind the lithosphere extension – which, in our opinion, could be described well by the planet Earth expansion model, according to V. Larin (2005).

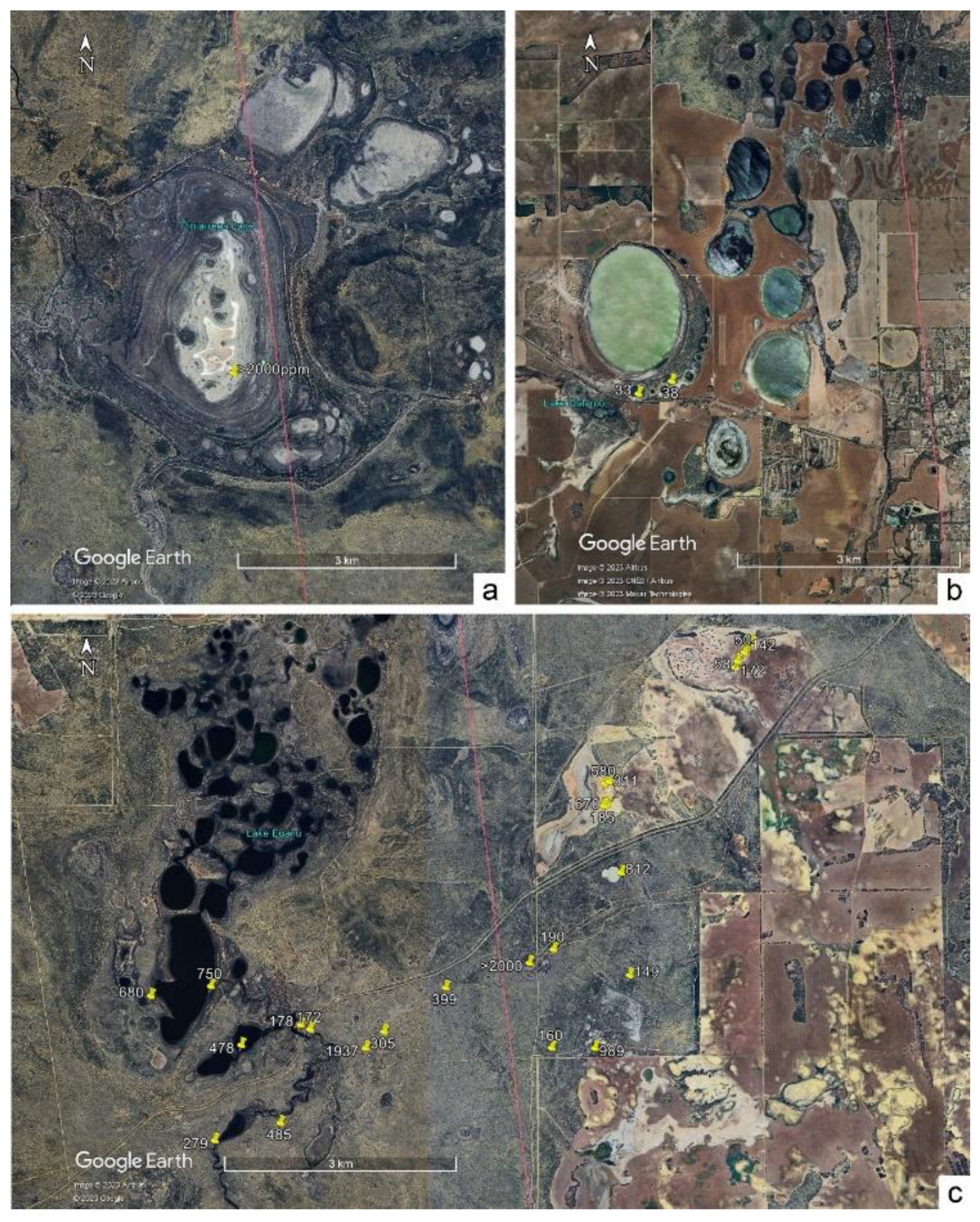

One of the potentially productive structures is located within the northern section of the AOI, forming the landscape around the Pinjarrega Lake (

Figure 9). Two major faults, Darling to the east and Urella to the west, are intersecting in – or, more accurately, beneath - the Pinjarrega Lake area, forming a unique cluster of tectono-structural elements, which relationship is depicted in

Figure 4, section F (A. J. Mory and R. P. Iasky, 1996). The Urella Fault splay sprouting to the east-south-east runs parallel to the Abrolhos Transfer Zone (ATZ) approximately 3km to 4km to the south. On the eastern flank of the Darling Fault, on the Yilgarn Craton, the NW-SE Yandanooka – Cape Riche Lineament marking the 20-40 mGal step change in gravity roughly aligns with the ATZ on the Perth Basin flank (

Figure 9).

The Urella fault throw is described to be maximal in the area between 29°40' and 30°05’S latitude (A. J. Mory and R. P. Iasky, 1996). According to Hoskin (2017), the basin subsidence in the Northern part of the Perth Basin was predominantly controlled by the Urella Fault, allowing to suggest the latter’s primary role in tectonic processes, as opposed to the Darling Fault. Both the Darling and the Urella faults are believed to be quiescent since the Early Cretaceous; however, their nowadays re-activation is quite possible, resulting in natural hydrogen degassing activity along the mantle-reaching conduits associated with them.

2.2. Datasets Used

It is very important to properly select the appropriate datasets for the desktop analysis to be performed for an AOI in order to suggest its natural hydrogen potential and, in the best case, to preliminarily identify potential targets for further research, represented by structures conducting natural hydrogen to the surface.

2.2.1. Deep Seismic, ANT, MOHO Depth

MOHO depth research data may provide valuable information on the top of the mantle proximity to the surface, since the proximity depth of the Mohorovičić boundary, often referred to as the Moho, may well become one of the parameters, potentially indicative of the natural hydrogen degassing activity.

The first extensive deep seismic study across the Darling Fault took place in 1992, the very comprehensive interpretation of which was performed by Middleton (M. Middleton et al., 1993). One of the most interesting observations was made in relation to the deeper structural extension of the Darling Fault named the Proto-Darling Fault, which was interpreted as a zone lacking any seismic response. The reasoning for the Proto-Darling Fault’s lack of seismic response was offered based on the current geophysical science views, suggesting either a high degree of structural deformation or the “fault shadow” effect. The extension depth of this structure could not be determined, which allows us to assume that its roots expand deep into the lower crust and/or into the top lithospheric mantle.

Another set of data applicable and quite useful for the natural hydrogen early exploration is provided by the CSIRO (Molloy, 2023) in their research of the Earth crust by means of the Ambient Noise Tomography (ANT), involving passive seismic imaging. However, it is crucial to point out that this geophysical method shall be utilized by a provider possessing substantial experience with natural degassing systems, very consciously, and with a number of factors taken into account since the interpretation results greatly depend on tectonic and lithology/petrology context, petrophysical anisotropy, fluidal phases’ contrast etc.

The analogies from other regions, such as wells Mt Kitty-1, Dukas-1 and especially Magee-1 wells in the Amadeus Basin (NT), allow us to suggest that along with the Moho proximity itself, the “gradient” of the Moho “hill slope” is quite important, too, see

Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Line diagram of major reflectors from the New Norcia deep seismic traverse: (1) Perth Basin; (2) Western Gneiss Terrane; (3) an intermediate crustal zone within the Yilgarn Craton; (4) a zone of strong reflections within zone 3; (5) a deep crustal zone that contains several easterly dipping reflection events; (6) the Moho Zone; and (7) the "Proto-Darling Fault". From M.F. Middleton, 1995 (M. F. Middleton et al., 1995).

Figure 10.

Line diagram of major reflectors from the New Norcia deep seismic traverse: (1) Perth Basin; (2) Western Gneiss Terrane; (3) an intermediate crustal zone within the Yilgarn Craton; (4) a zone of strong reflections within zone 3; (5) a deep crustal zone that contains several easterly dipping reflection events; (6) the Moho Zone; and (7) the "Proto-Darling Fault". From M.F. Middleton, 1995 (M. F. Middleton et al., 1995).

Figure 11.

Moho depth E Amadeus Basin, NT. Mt Kitty-1, Dukas-1 and Magee-1 wells indicated in red diamonds. Modified from (Debacker et al., 2021).

Figure 11.

Moho depth E Amadeus Basin, NT. Mt Kitty-1, Dukas-1 and Magee-1 wells indicated in red diamonds. Modified from (Debacker et al., 2021).

In this regard, it seemed worthwhile to include the Moho structure data into account when studying natural hydrogen potential in the AOI, at least at the general consideration level. However, the accuracy of the current Moho mapping provided by the GeoVIEW program does not allow turning this parameter into a significant contributor to the decision-making process.

2.2.2. Remote Sensing - Satellite Imagery

This dataset improves the identification of potential “hotspots” at the early stages of exploration.

H

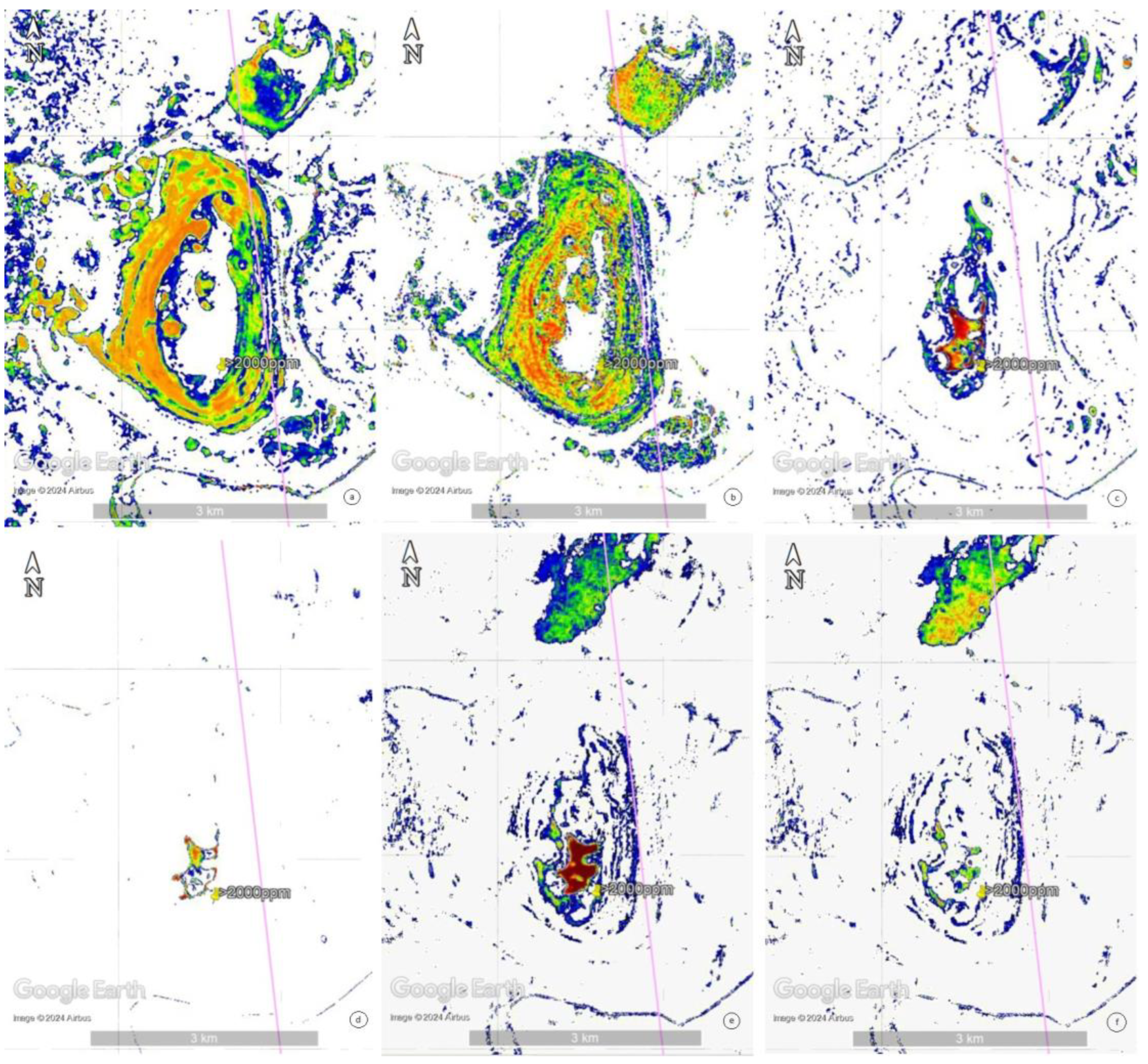

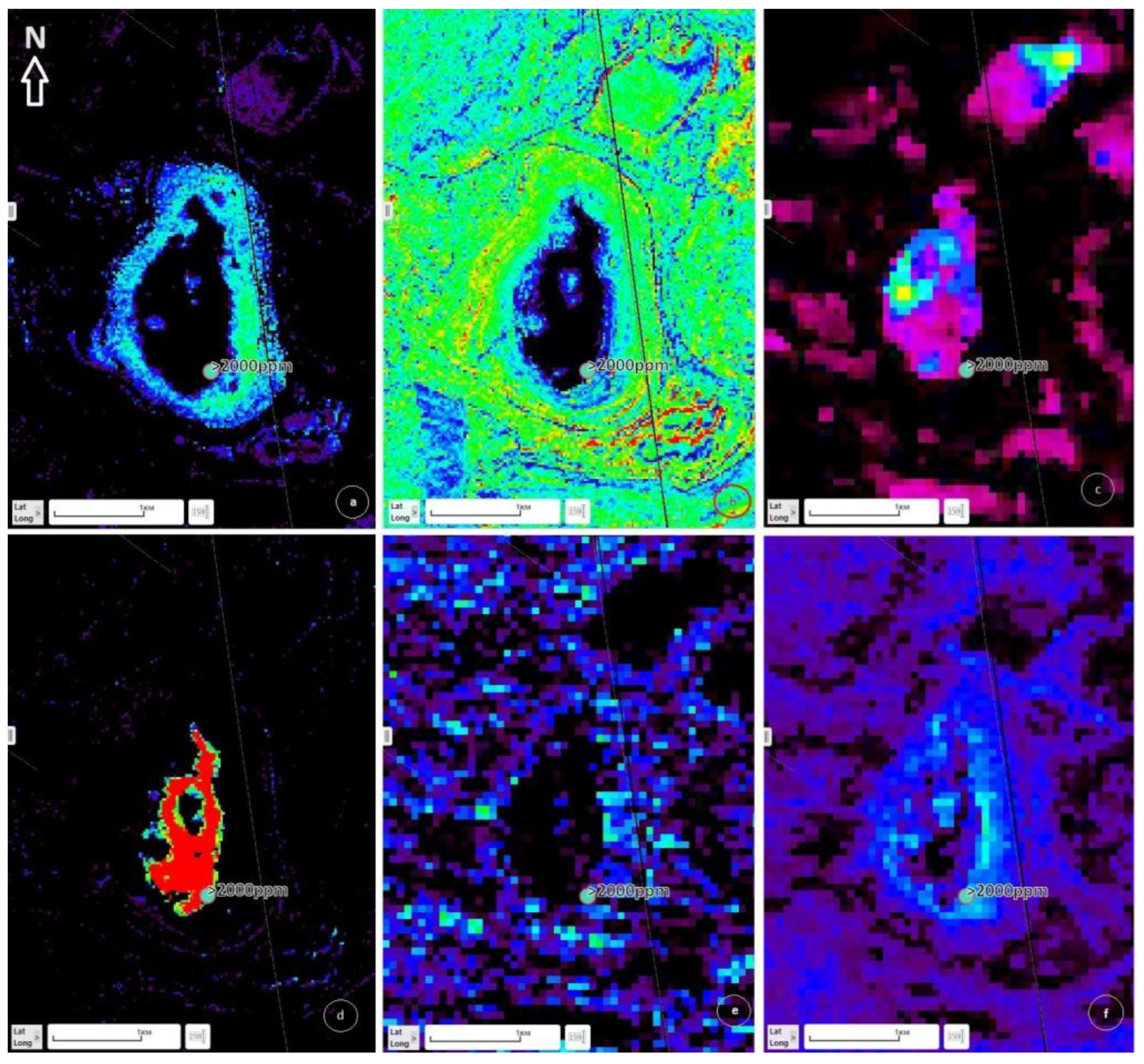

2 layers are produced by various complementary algorithms provided by Manatee Ltd. The results of these algorithms’ interpretation are demonstrated in

Figure 12a, b, c, d.

Along with the hydrogen projections, other gases’ emanation maps appear to be extremely helpful in assessing their degassing activity and the “first choice” areas for initial (preferred) approaching the potentially promising locations campaignError! Reference source not found.:

Helium He: this gas very frequently accompanies the latter in its surface manifestations, also sharing its de-gassing paths on the way through the top silicate crust to the surface;

Ozone O3 Deficiency: According to the researchers (Syvorotkin, 2013), hydrogen turns ozone O3 molecules into oxygen O2 by reacting with a single oxygen atom having a relatively loose bind with the main O2 pair of atoms, with water produced as a by-product;

Methane CH4 (

Figure 12e): From the product supplier statistics, methane manifestations statistically coincide with hydrogen degassing spectra in ~83% of cases.

2.2.3. Remote Sensing – ASTER

This dataset assists with the identification of mineral associations (

Figure 13) and RedOx balances. ASTER set of layers is supported by a number of platforms. In Western Australia, it is included in the GeoVIEW geoscience platform. ASTER layers offer several types of geochemical and mineralogical data on the Project Area, examples below (Cudahy, 2012):

Ferrous Iron Index reflects the Fe2+ relative abundancy, which under certain conditions may indicate the degree of chemical reduction possibly due to hydrogen presence, demonstrating the RedOx balance shift;

Opaque Index, which is a combination of the following: (1) magnetite-bearing rocks (e.g., BIF); (2) maghemite gravels; (3) manganese oxides; (4) graphitic shales. (1) and (4) above can be evidence for “reduced” rocks when interpreting REDOX gradients;

Ferric Oxide Content: (1) Mapping transported materials (including palaeochannels) characterised by hematite (relative to goethite); and (2) hematite-rich areas in “drier” conditions (e.g., above the water table) whereas goethite-rich in “wetter” conditions (e.g., at/below the water or areas recently exposed);

Quartz Index: Use in combination with the Silica index to more accurately map, for example, quartz rather than poorly ordered silica like opal or other silicates like feldspars and (compacted) clays;

Silica Index: Broadly equates to the silica SiO2 content though the intensity (depth) of this feature is also affected by particle size <250 microns.

2.2.4. Geomorphology

This dataset is aimed at the identification of certain terrain features revealing potential hydrogen manifestations and its activity impressions in landscapes: circular depressions, (paleo)drainage patterns, sand blows/boils a.k.a. injectites (Hurst, Scott, & Vigorito, 2011), etc.

Geomorphology features are considered to be very important for natural hydrogen degassing structures research and exploration. However, this criterion depends on a number of factors, such as:

Soil substrate: RedOx (pH) balances, regolith thickness and, in some cases, agricultural activity level;

Surface and bedrock geology context, e.g., cratons vs. basins;

Tectonic and structural development history;

Structural features;

Geochemical parameters;

Petrology (alterations) and mineralogy (associations) aspects.

Sometimes, the certain geomorphology features such as circular depressions first noted by V. Larin (V. Larin & Larin, 2007), sometimes wrongfully referred to as “fairy circles” by some researchers, may provide the leads to potentially active hydrogen conducting structures. (The “fairy circle” term was originally introduced for the certain flora phenomena described in botanic disciplines. We consider the use of this term for the description of natural hydrogen geomorphological manifestations on terrain surfaces as scientifically inappropriate.) However, we would like to warn the researchers from relying too much on this feature alone because of two reasons:

Natural hydrogen is quite often found at locations having no circular depressions (V. Vidavskiy, R. Rezaee, 2022), and

Our field soil gas detection results confirmed that several very distinctive circular depressions earlier described by the other scholars (Frery, Langhi, Mainson, & Moretti, 2021) do not yield any significant levels of hydrogen concentrations (

Figure 14b).

Within the area of research, there are several clusters of circular depressions studied in the course of the subject research, with the following H

2 concentrations in the top soil layer (<1m) – see

Figure 14:

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

Namban lake system

- 7.

Coonderoo lake

- 8.

Nameless circular structures across the AOI acreage

Interestingly, several of the local land users note that in some cases, a circular depression emergence could be watched “in real time”, when the same landuser owns the land for long enough. The process is described in the following way:

First, the gentle hill appears;

Then, the top of the hill develops the “sand blow”, with inevitable soil fertility loss and its consequent erosion;

Later, the top of the hill starts caving in forming the “crater”, with further subsidence;

Finally, this “crater” gets filled with fresh water coming up from the deep.

Initially, the water is fresh, so “the sheep would drink from it”, then, within several years or decades, it turns salty.

This process is described pretty much the same way along the entire strike of the northern part of the Darling Fault within the AOI, allowing to suggest the geomorphologic activity in the area, apparently being related to the natural hydrogen degassing processes along this regional tectonic structure.

All the examples above demonstrated the significant levels of hydrogen readings from several hundred ppm to the excess of 2,000ppm (the MX6 unit detection range limit for H2), except for the Dalaroo Lake, where the H2 concentrations did not exceed 40ppm, of the same order of magnitude with the results achieved by E. Frery of CSIRO in 2021.

Other geomorphology features bearing significant meaning in the process of the early exploration for natural hydrogen are represented by gentle hills with sand “blow-outs” and other expressions of collapse on their summits or very close to them. These structures are associated with hydrogen degassing processes causing water interaction with swelling clay beds immediately close to the surface.

Circular sand dunes named “sand boils” in Arkansas, the USA (

Figure 15), are closely related to seismicity causing liquefaction processes. In the scientific literature, these specific near-surface micro-tectonical and geomorphological features are dubbed as “

injectites” (Hurst et al., 2011), a.k.a. “sand dikes”. These structures were tested in the process of conducting this research as well, yielding somewhat significant H

2 readings within several dozen ppm – up to 1,000ppm from the shallow (<1m deep) holes. However, due to the extremely high mobility of H

2, it would be unrealistic to expect high readings through the unconsolidated soils e.g., loose dry sands and loams.

The list of geomorphology structures mentioned above studied within this research is not exhaustive; however, the scope of this paper does not allow expanding on this subject.

2.2.5. SEEBASE

The importance of this comprehensive source of geological and geophysical data provided by Geognostics (

https://www.geognostics.com/) offering a wealth of information about deep layers and structures cannot be overestimated. In 2022, the company issued a new, updated and more detailed Geognostics report (Geognostics Australia Pty Ltd, 2022) on the Perth Basin structural geology, as well as on its development history. Interestingly, the latter comprises mostly extensional events, supporting the vision of the Perth Basin posing as a mostly rifting structure.

The meticulously detailed 3D image of the Perth Basin is shown in

Figure 16, allowing us to see the relationships between the major tectonic units.

2.2.6. Conductivity Data

This dataset provides knowledge (Hoskin, Regenauer-lieb, et al., 2015) about deep structures potentially associated with hydrogen activity.

Electric resistivity/conductivity data plays an important role in natural hydrogen studies (V. N. Larin, 2005). Structurally speaking, conductive protrusions identified by magnetotellurics (MT) electrical resistivity data acquisition may be interpreted as pre-cursors for the early reconnaissance of the natural hydrogen potential. Therefore, positive conductivity anomalies could possibly become the indicators of hydrogen degassing activity and/or of its reactive products’ presence.

In the specialized literature, there is no shortage of attempts to explain the prominence and the existence of highly conductive structures discovered in impressive quantities around the world, with early systematic attempts dating back to the early 1990s (Jones, 1992). Several mechanisms are proposed to explain this phenomenon, every each of them being questioned and eventually rejected, for the following reasons:

Graphite films binding rock grains: large grain size in the lower crust supporting resistivity (A. Jones, 1992); low mobility of carbon (A. Jones, 1992); lack of possibility to stay interconnected for hundreds of km due to the limited stability of grain-boundary films (A. Jones, 1992; K. Selway, 2014); thermal stability of graphite, especially in regards to its irreversible dehydration processes (K. Selway, 2014); tectonic stresses permanently breaking the graphite connection pathways (K. Selway, 2014); higher interfacial energy and larger dihedral angle between graphite and olivine (Zhang & Yoshino, 2017).

Mylonite petrology: low frequency of occurrence within the Darling Fault region (T. Hoskin et al., 2015).

Fluids in porous zones: this model requires an unrealistically high percentage of pores, over 10% (A. Jones, 1992) or even between 10% and 30%, based on the gravity model estimates (T. Hoskin et al., 2015); depth constraints posed by the requirement to have permeability pathways, which contradicts the seismic quiescence of the Darling fault estimates (T. Hoskin et al., 2015).

Partial melt: temperature, [shallow] depth and mineralogy constraints (A. Jones, 1992; K. Selway, 2014).

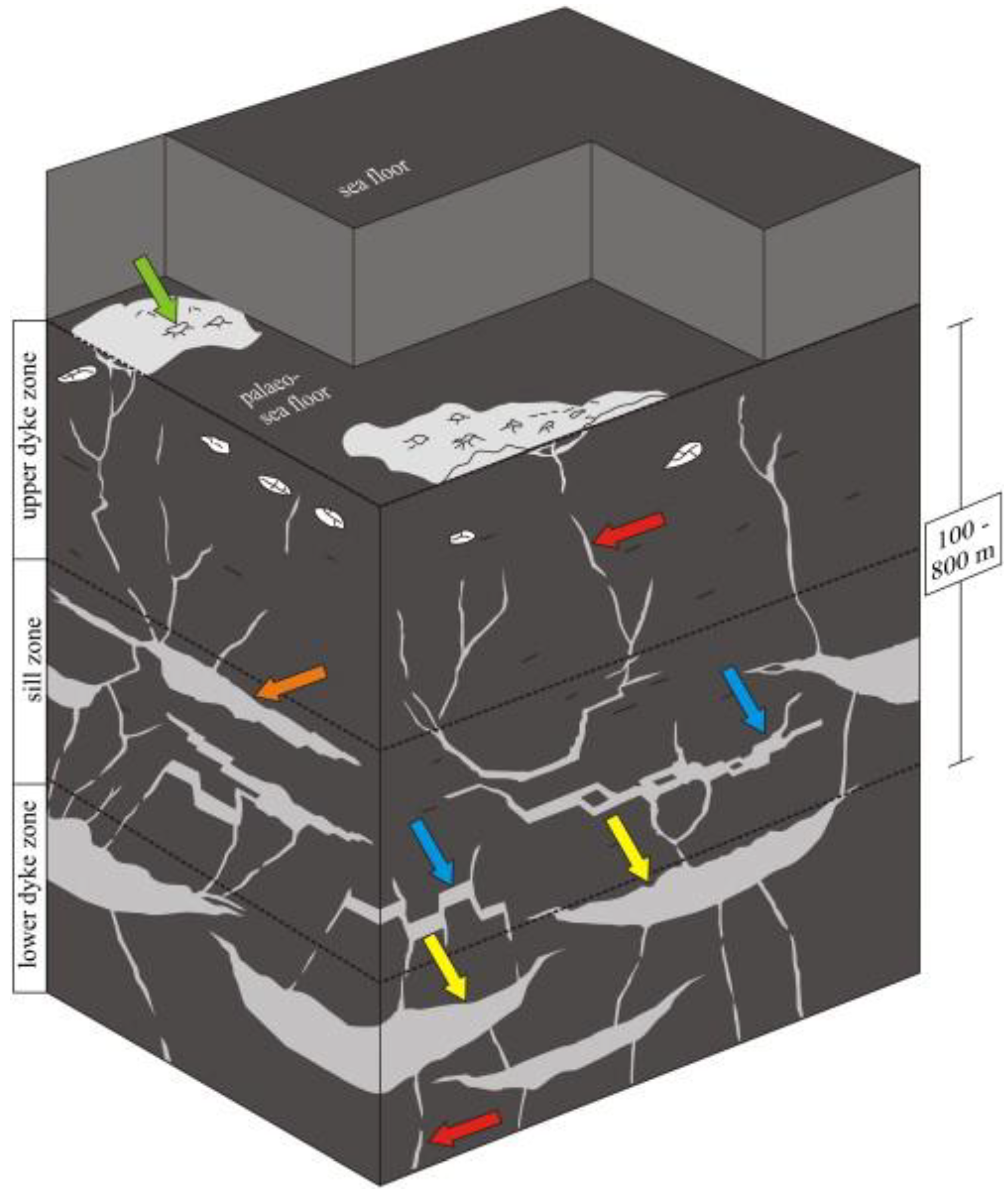

According to the PHE concept, the mantle is composed of inter-metallic substance (V. N. Larin, 1993). In certain tectono-structural environments, this substance may protrude closer to the surface, resulting in a number of geophysical, geochemical and geomorphological consequences (V. N. Larin, 2005).

These wedge-looking structures formed by “intermetallic silicides” (

Figure 17) shall come up on resistivity cross-sections as strong conductors. During the past couple of decades, with the massive arrival of fundamental research data, this model of planet structure and composition was confirmed by a number of independent researchers (Rohrbach et al., 2011).

Other researchers (Mike Dentith et al., 2013; Selway, 2014) admit that the presence of hydrogen is likely to increase formations’ conductivity, e.g., through the ionic to proton diffusion transit mechanism in Fe, Mg silicates with depth (K. Selway, 2014). The latter perfectly correlates with the PHE concept conclusions in regard to the transit of covalent and ionic bonds between hydrogen and various metals under pressure (V. Larin, 2005).

There are two known deep MT transects available for the areas adjacent to the Project Area:

C.II.6.i. New Norcia (NN) MT Transect (Hoskin, Regenauer-lieb, et al., 2015), which was run along the earlier deep seismic transect along the same profile. It was acquired in 2011, running W - E crossing the Darling Fault south of New Norcia. This transect offers a very comprehensive set of data regarding regional structural lineaments, some of them extending into the Project Area.

Later, this transect was re-interpreted by T. Hoskin for his PhD Thesis (Hoskin, 2017). Remarkably, the conductive bodies associated with the main tectono-structural features are still very much recognizable in this latest interpretation.

The conductive zones in the western section of the transect seem to be closely related to the Muchea (UF) and the Darling (DFZ) Faults (stations NN05 and NN06, correspondingly), apparently running upwards from the deeper geospheres, while the latter possibly communicate with the mantle below the Moho. This explains the role of the Darling Fault serving as a conduit for deep-seated hydrogen, conveying it to the surface.

C.II.6.ii. Coorow – Green Head (CGH) MT Transect, which was shot between 2011 and 2014. Data interpretation was performed immediately upon this project's completion and revealed several conductive structures associated with the deep faults crossed by this transect. Same as for the NN MT transect, the CGH originally interpreted in 2015 was also re-interpreted by Hoskin in 2017 for his PhD Thesis.

It is well seen that on the craton flank (central-eastern part of the transect), deep faults apparently communicating with the lower crust and, most likely, the upper mantle, quite often demonstrate their affinity with conductive structures extending to great depths, possibly beyond the Moho. Quite contrary, the very pronounced conductivity anomalies in the Perth Basin (the central-western part of the transect) seem to be relatively shallow, not expanding too deep.

2.2.7. Tectonic Stresses

In-situ tectonic stress analysis is essential for understanding the current extension/compression regime/s (Reynolds, Coblentz, & Hillis, 2002). It may assist with the task of assessing both regional and local forces acting in the crust, potentially either promoting or inhibiting natural hydrogen and other gases’ degassing processes.

For the certain reasons, in-situ tectonic stresses in general are mostly studied for the purpose of assessing regional seismicity risks and predicting earthquakes (Lambeck, MCQUEEN, Stephenson, & Denham, 1984). Therefore, such research is concentrated on the orientation (azimuth) vector as well as on its absolute force and/or its magnitude - but not on the compression/tension regimes, which is quite understandable, with consideration of the main purpose of such studies.

The majority (53%) of reliable data for in-situ tectonic stresses are provided by means of analyzing physical defects occurring in the process of drilling wells in the AOI: break-outs (43%), DITF - drilling-induced tensile fractures (8%), and over-coring processes (2%) (Hillis & Reynolds, 2000). However, it is important to bear in mind that these analyses start bearing sensible meaning below the certain depths – for the wells where such measurements are taken, not being the case for the majority of shallow mining and geotechnical operations. Therefore, the number of analyzed boreholes is limited to deeper (petroleum) wells, where a contractor is under contractual obligation of taking such readings in the process of drilling the well.

At any rate, the study we conduct on tectonic stresses potentially affecting hydrogen degassing paths through deeper geospheres requires data from much greater depths, currently inaccessible by means of conventional drilling.

The commonly accepted viewpoint (Rajabi, Tingay, Heidbach, Hillis, & Reynolds, 2017) suggests mostly compressional stresses for the SW of the Australian continent.

Other researchers (Lee, Mikula, Mollison, & Litterbach, 2008) who base their conclusions on the practical work results, however, disagree with this mainstream viewpoint, proposing mostly extensional mode for the majority of Australian megastructures. Noticeably, the stipulated stress magnitudes suggest the maximal value of 90 MPa for the Yilgarn Craton, as well as the complete lack of (significant) compression zones for the entire continent.

This latter view agrees with the PHE Concept, according to which the majority of global tectonic stress modes is represented by extension not compression, primarily due to the acknowledgement of the expanding planet model (V. N. Larin, 2005).

The vision of extension tectonic stresses prevailing in the AOI is supported by the earlier researchers (K. Lambeck et al., 1984), at least in its western part – see the Perth Basin (western) flank in

Figure 18.

2.2.8. Geology, Tectonics, Geodynamics Structural Analysis

This dataset assists with the identification of potential hydrogen degassing pathways from deeper geospheres towards the surface along the petrophysically weakened irregularities and anisotropy vectors – See Paleotectonic, Geodynamic and Structural Setting above.

2.2.9. Petrology, Intrusive Bodies

Same as above, intrusive bodies’ contact zones represented by altered mineralogy associations offer a great opportunity for forming natural hydrogen conduits.

2.2.10. Seismicity

Studying earthquakes epi- and hypocenters allows to assess their relationship with structural features and, potentially, with deep hydrogen-producing magmatic bodies. For the AOI, the majority of the known earthquakes are concentrated to the east across the Darling Fault (Calingiri, Cardoix) -SE (Meckering), within the Yilgarn Craton terranes. Within the Perth Basin, the seismicity is insignificant, which may be attributed to the crystalline basement rock depths up to 14,000m; the sedimentary basin formations do not transfer the shocks that easily, effectively muffling them to hardly noticeable magnitudes.

2.2.11. Radiometry

The results of the recent work done by a group of European researchers (Prinzhofer, Rigolett, Berthelot, & Francolin, 2022) preliminarily suggest a correlation between the natural hydrogen degassing manifestations on the surface and Th and U concentrations in the top soil layers. According to this research, high concentrations of Th and low U/Th ratios correlate with high H2 concentration anomalies.

The GA website (

https://portal.ga.gov.au/) offers the maps of Th concentrations and U/Th ratio (

Figure 19a and

Figure 19b, correspondingly). For some locations where H

2 presence was detected, these maps demonstrate the significant level of radiometry data correlation with soil gas measurements for the bulk of the structure, whilst for others there is little or no correlation, at all.

Overall, in our opinion, this technique may benefit from more practical research performed in-situ, with comparisons to be made between the desktop studies and the results of the soil gas detection in the field.

2.2.12. Soils

This parameter may be used for determining the RedOx balances and forecasting the field conditions while planning soil gas sampling campaigns.

For Western Australia, we were unable to find this data layer readily available in GeoVIEW or any other system supported by the state, compared to how it is quite comprehensively done in South Australia, being offered through the SARIG platform (

https://map.sarig.sa.gov.au/).

Based on data available from the GA platform (

https://portal.ga.gov.au/), the structures emitting H

2 confirmed by the surface gas surveys, are characterized by the elevated pH values, thus demonstrating higher chemical reduction potential, see

Figure 20.

From

Figure 20, it is also apparent that the pH values drop towards the surface, which most likely correlates with the view of H

2 chemical reduction activity dropping with depth decrease, due to the system being influenced by atmospheric oxygen.

Another phenomenon of natural hydrogen’s interaction with soils is related to humus degradation and subsequent fertility loss. Being the aggressive chemical reduction agent, hydrogen tears long soil organic acid molecules apart, which results in forming shorter molecular chains. This effectively causes soils’ depletion/dilution, with erosion expanding rather quickly due to the decreased fertility of humus substrate and consequent vegetation replacement by less demanding species, and/ or its further complete disappearance. On the geochemical side, this process correlates with the iron chemical reduction from immobile Fe3+ to very mobile Fe2+, (see 2.2.2 Remote Sensing – ASTER) with the latter being evacuated by surface water flows.

These processes were described in detail by Sukhanova with colleagues (Sukhanova, Larin, & Kiryushin, 2014), explaining chemical relationships between natural hydrogen degassing and soils’ fertility degradation. Our discussions with the local land users describing the sequence of events in a rather similar way confirm this conceptual view.

In the AOI, these processes resulted in poor soil qualities and fast erosion of fertile layers, which in turn may lead to the formation of sand blows (see 2.2.4 Geomorphology).

2.2.13. Mineral Associations and Alterations

This dataset can prove to be useful for the identification of hydrogen flows’ interaction with host rocks, as well as for determining the most probable degassing paths. However, mineral associations related to hydrogen metasomatism are still poorly understood.

The desk-top study of the mineral associations across the AOI was based on data available from the open sources. GeoVIEW.WA provides quite a comprehensive data set on this subject. Another set of petrology and lithology data is provided by the WAROX platform, also available through GeoVIEW.WA.

Several mineralogy aspects were taken into consideration:

We would like to review the process of mineral phases’ formation with nSiO2⋅mH2O, K, Na, and Ca. It is suggested that excessive chemical elements, such as Si, Ca, Na, and K, vacate the reaction zone of hosting rocks, being assisted by the natural hydrogen degassing streams.

Additionally, iron Fe and magnesium Mg are expelled from the system. This applies primarily to pyroxenes, amphiboles, micas, etc.

Potassium K and sodium Na vacate the reaction zone in the form of soluble compounds, or alkalis (KOH and NaOH). This is why hydrogen is often associated with hyperalkaline water sources (pH > 10) (Miller et al., 2016). Ultimately, alkali metals end up as halite (NaCl) and sylvite (KCl) salt deposits in water streams and circular depressions a.k.a. “fairy circles” along the river valleys, which quite often are tracked down as permeable zones.

The AOI presents a substantial number of examples of streams and concentric depressions, sometimes referred to as playa lakes, demonstrating the abundance of halite NaCl both in the water and, when dried for, in the surface deposits. According to the local farmers, in some of the originally fresh lakes, the water turns salty within several years to several decades, as mentioned above (see 2.2.4 Geomorphology).

Calcium Ca, vacating the reaction zone most likely in the form of hydroxide Ca(OH)2, terminates its migration path nearby, depositing in the form of calcite (CaCO3) or gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O). The distribution of the latter is covered quite well on the GeoVIEW.WA ASTER layer.

Within the area of research, there are several occurrences of limestone CaCO

3, bentonite (Na,Ca)

0.33(Al,Mg)

2Si

4O

10(OH)

2·nH

2O and saponite Ca

0.25(Mg,Fe)

3((Si,Al)

4O

10)(OH)

2·n(H

2O), actively mined in the area. The example presented in

Figure 21 demonstrates the abundance of these minerals in the Pinjarrega area. Notably, according to the Watheroo Minerals PTY LTD geochemical assays data (Watheroo Minerals Pty Ltd, 2010), soil samples demonstrate levels of pH in the alkaline range between 8.2 and 9.4.

It is important to emphasize that stratigraphically, the carbonate deposits mined by Watheroo Minerals PTY LTD are located on the craton flank of the Darling Fault, therefore it would be rather difficult to link their origin to the sediments’ lithification processes such as diagenesis etc. Apparently, other formation mechanisms shall be suggested for these deposits.

As for Silicon Si, it may migrate from the reaction zone, as we believe, in the form of polysilicic acids of the nSiO2⋅mH2O composition, which decompose with forming an aqueous SiO2 gel, the further fate of which may vary from case to case. Thus, depending on the conditions, the setting gel may turn into opals, as in Coober Pedy Opal Fields, where they are closely associated with kaolinite (Dutkiewicz, Landgrebe, & Rey, 2015).

In other conditions, hydrous silica gel forms layers, concretions and nodules of chert, often observed at the contact of Cretaceous and Paleogene rocks, e.g., in the Negev Desert in Israel or on the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. The appearance of cherts at the turn of geological epochs becomes understandable if we take into account the catastrophic nature of the planet's structure reshaping, which occurred with the active participation of hydrogen, tied with these events’ timelines.

In some cases, Si-gel vacating the hydrogen metasomatism zone crystallizes in the form of small quartz (SiO2) crystals. Sometimes the product sand consists of perfect crystals shaped as semi-rounded transparent or translucent grains of similar sizes, observed in the sand deposits.

In the area of research, Quartz and Silica layers in ASTER demonstrate abundant occurrences of these minerals, for examples see

Figures 13e and 13f, correspondingly (see

2.2.3 Remote Sensing – ASTER). Not surprisingly, there is a significant number of mining companies exploring and developing these mineral resources. One of them, the Moora Mine operated by Simcoa (

Figure 22), produces silicone aggregates of the highest purity.

We are still a long way from understanding the reasons why silica-gel forms quartz in some settings and chalcedony, opal or chert in others.

2.2.14. Heat Flow Studies

Outside the geothermal energy domain, the heat flow subject is not broadly discussed by the academia and the industry. In our opinion, however, it is closely related to the natural hydrogen degassing process when viewed through the prism of the PHE concept (V.N. Larin, 2005). According to this concept, intermetallic/silicide wedges protruding into the crust through deep faults and rifting zones (

Figure 17) are

colder than suggested by the existing mainstream model. In this regard, the unconventionally low values of geothermal parameters for Barberton-1 well may be explained by its proximity to the Darling fault with the latter providing the cooling effect due to the presence of intermetallic silicides approaching the surface through the Proto-Darling paleo-tectonic structure. A similar effect is observed in other parts of the world. For instance, the Baikal continental rifting system is famous for its extremely low heat flow values, resulting in the permafrost zone expansion to the south for substantial distances (Poort & Klerkx, 2004). Another, a very well known, example of the (relatively) low heat flow is set by Eureka Low (Williams & Sass, 2006) area in Nevada, USA, where a <60 mW m

-2 to <45 mW m

-2 area is sitting right in the middle of the Great Basin province demonstrating the average values between 90 mW m

-2 and >100 mW m

-2.

Overall, data available for the bulk of the Australian continent is not too convincing (Haynes, 2021) in terms of the mainstream model applicability.

A very comprehensive research of the Perth Basin geothermal potential done by Hot Dry Rocks (Hot Dry Rocks Pty Ltd, 2008) in 2008 demonstrated that the subject modeling performed through the prism of existing mainstream concept is not confirmed by the practical values received from the wells drilled in the area. Specifically, Barberton-1 well drilled the closest, some 3.5km W of the Darling Fault, is supposed to show the highest geothermal parameters i.e., heat flow and thermal gradient among the majority of wells in the Perth Basin. Instead, the well demonstrated “low geothermal gradient for the area, 1.95°C/100m. <…> The geothermal gradient for the Barberton structure compares with approximately 2.41°C/100m for Cypress Hill No.1, 2.06°C/100m for Gingin No.1, 2.37°/100m for Walyering No.l, 2.20°C/100m for Warro No.l, and 2.47°C/100m for Yallallie No.1.” (WAPIMS, 1990).

According to Mory and Iasky (A Mory & Iasky, 1996), the thermal gradient for Barberton-1 well is even lower: 1.8°C/100m.

Barberton-1 well geothermal parameters’ comparison with other wells drilled in the Perth Basin are shown in

Figure 23.

The geothermal chart for Barberton-1 well demonstrates the extreme deviation of the actual heat flow value of 64mW/m

2 from the modelled ones, see

Figure 24. The significant number of geothermal parameter deviations from the model for the area resulted in dubbing this misfit data as “low quality” and therefore disregarding it, see p. 28 of the

Hot Dry Rocks Report.

Apparently, this list of discrepancies calls for a new approach. In this regard, the PHE Concept explains the majority of dilemmas and paradoxes accumulated by fundamental geoscience, which otherwise appear to remain unresolved by means of the existing mainstream model.

2.2.15. Existing Oil/Gas/Geothermal/Mineral Wells and Mineral Boreholes Analysis

In the course of the research, the comprehensive study of borehole data available for the WA state territory from the open sources was performed with the purpose of obtaining in-depth lithological, petrological and geochemical data. Several interesting observations were made, although some of these were related to the areas outside the AOI boundaries. This dataset provided extremely valuable information on the local formation relationships and contact depths, mineralogy alteration systems location and degree, as well as exact fault positions and directions. These datasets analysis allowed us to preliminarily identify and prioritize the potentially productive hydrogen degassing subsurface structures.