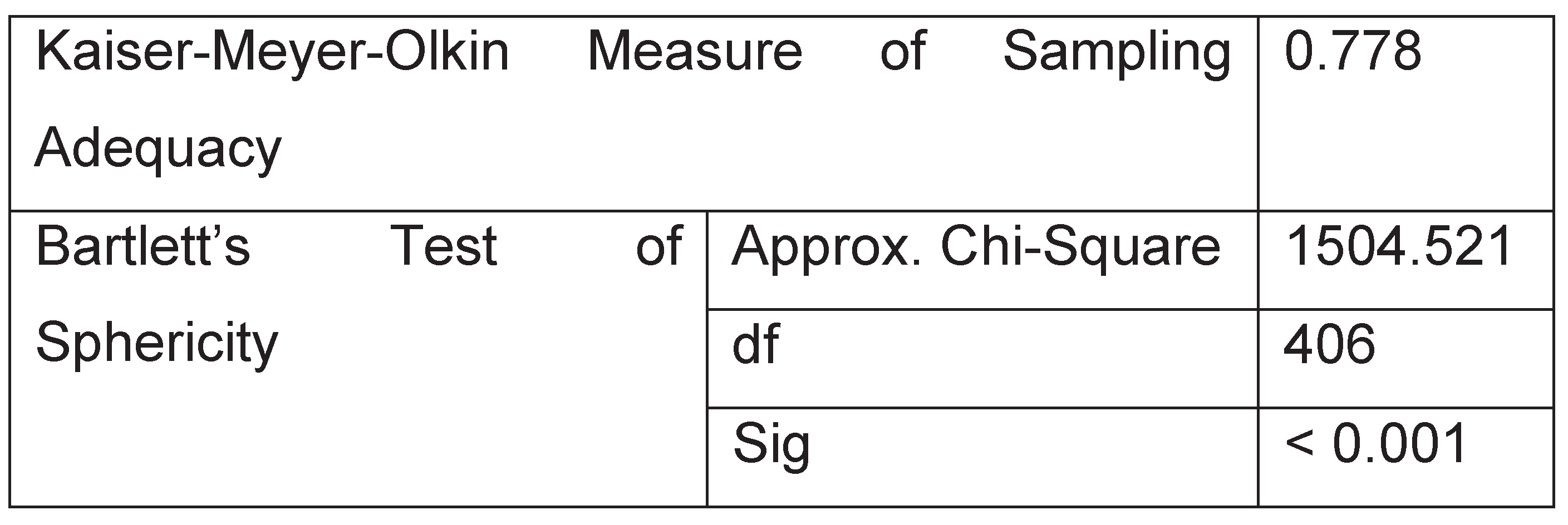

KMO Measure and Bartlett’s Test

Results shown in

Table 2, the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.778, suggesting that the data was satisfactorily appropriate for factor analysis. In addition, a highly significant result (χ

2 (406) = 1504.521, p < 0.001) from Bartlett’s test of sphericity supported the applicability of factor analysis on the dataset by showing that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix.

The eigenvalues showed that the first factor explained 23.9% of the variance, the second factor 11.2% of the variance, a third factor 7.5% while the fourth factor explained 5.9% of the variance. The fifth until the eight factor had eigenvalues greater than 1 but less than 2. Overall, the eight extracted factors accounted for a cumulative variance of 65.5%.

Table 3 below lists the factors and factor loadings as well as the item communalities.

Note: Factor loadings are in boldface. Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax Rotation.

Communalities ranged from .458 to .810 (see

Table 3). For easy of interpretation, factor loadings displayed in

Table 3 are from the rotated pattern matrix. Eigenvalues of ≥1 were used to interpret the number of factors in the data set.

Factor 1 comprises of 8 items as shown in

Table 4. A follow-up reliability analysis found factor 1 to have good internal consistency (α = .868). The frequency and percentage (in brackets) distribution of responses to eight item statements is shown in

Table 4.

Table 3 shows that just above 65% of the respondents agreed with the statement “My lecturers make me see that I am good at my work” most or all of the time. On the other hand, approximately 58% indicated that they did not have a lecturer they could talk to. Slightly over 75% of the respondents indicated that the lecturer explained concepts most or all of the time. Almost 90% of the respondents stated that the lecturer worked hard to make them to understand concepts. Furthermore, 78% of the respondents stated that the lecturer gave extra examples in class. Approximately 70% and 75% of the respondents indicated that lecturers supported them to aim high as well as think of their bright future respectively while almost 65% stated that they had at least one lecturer who encouraged them to do their best. There was association between the campus and whether respondent had a lecturer they could talk to (

= 18.501, p < 0.001). There was also an association between campus and whether respondent had at least one lecturer who encourages them to do their best (

= 11.343, p < 0.05).

Factor 2 consists of 6 items as shown in

Table 5 above, which appeared to measure what does it mean to students to achieve in class. A follow-up reliability analysis found factor 2 to have acceptable internal consistency (α = .712).

Table 5 shows that most (97.6%) of the respondents were of the view that the future and success depended on their hard work. Approximately 96% believed they could do better while 94% stated that they did all assignments most or all the time. Just below 98% of the respondents indicated that doing well at school was important to them. With respect to being in control of what happened to them, 78% of the respondents indicated that they were in control most or all the time. Almost all (98.4%) of the respondents stated that their future was in their hands. There was association between “future and success depend on my hard work” and campus (

= 7.998, p < 0.05), age group (

= 25.052, p < 0.001) and gender (

= 9.204, p < 0.05). There was also an association between the respondents’ belief to do better and campus (

= 8.070, p < 0.05). The importance of doing well at school was associated with the campus (

= 8.671, p < 0.05) and age group (

= 16.808, p < 0.01). Whether a respondent was in control of what happens to them was associated with the campus (

= 16.283, p < 0.001).

Factor 3 consists of 3 items as shown in

Table 6 above, which appeared to measure the influence of support from peers or mentors in relation to students’ resilience. A follow-up reliability analysis found factor 3 to have acceptable internal consistency (α = .742).

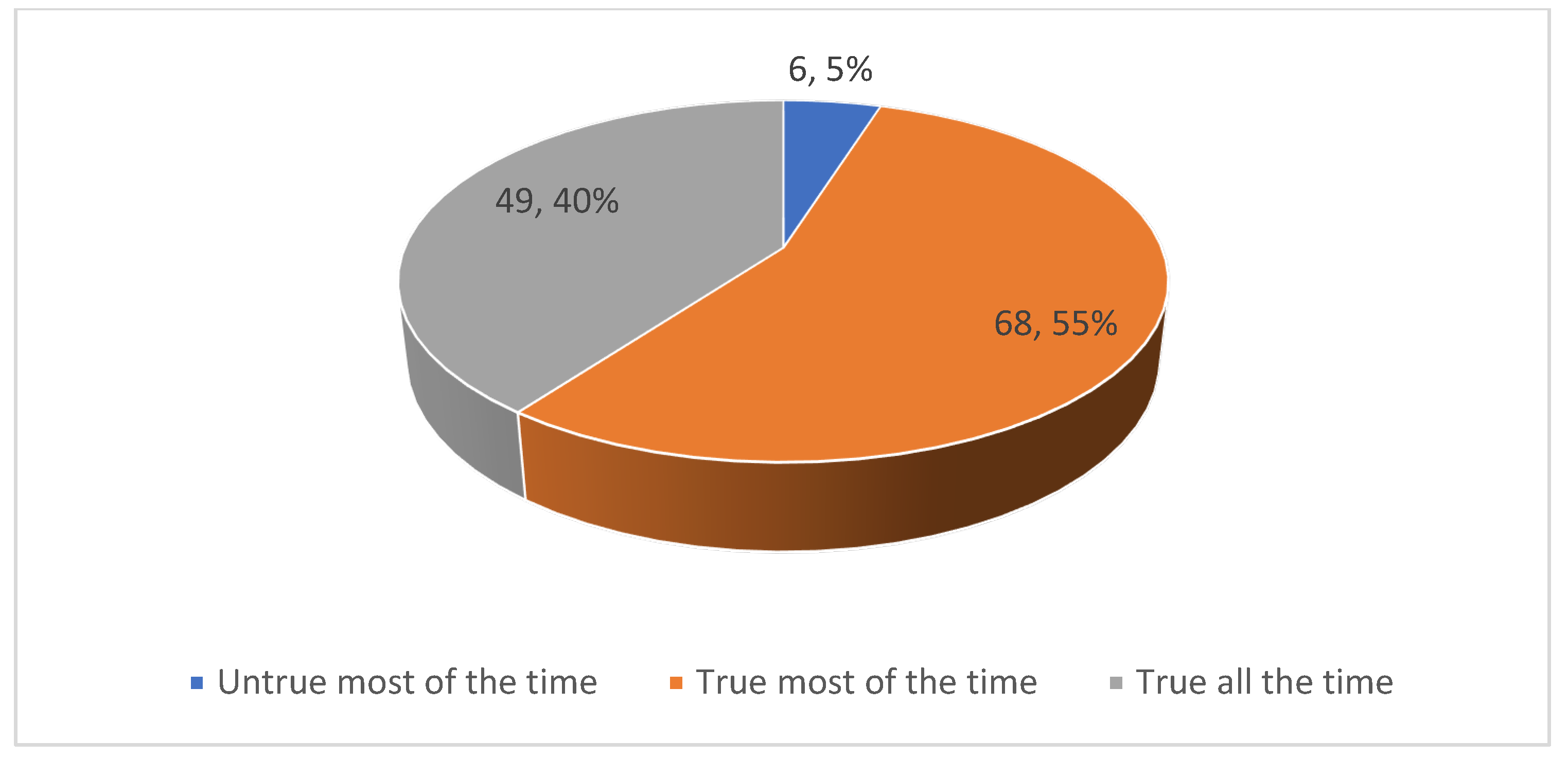

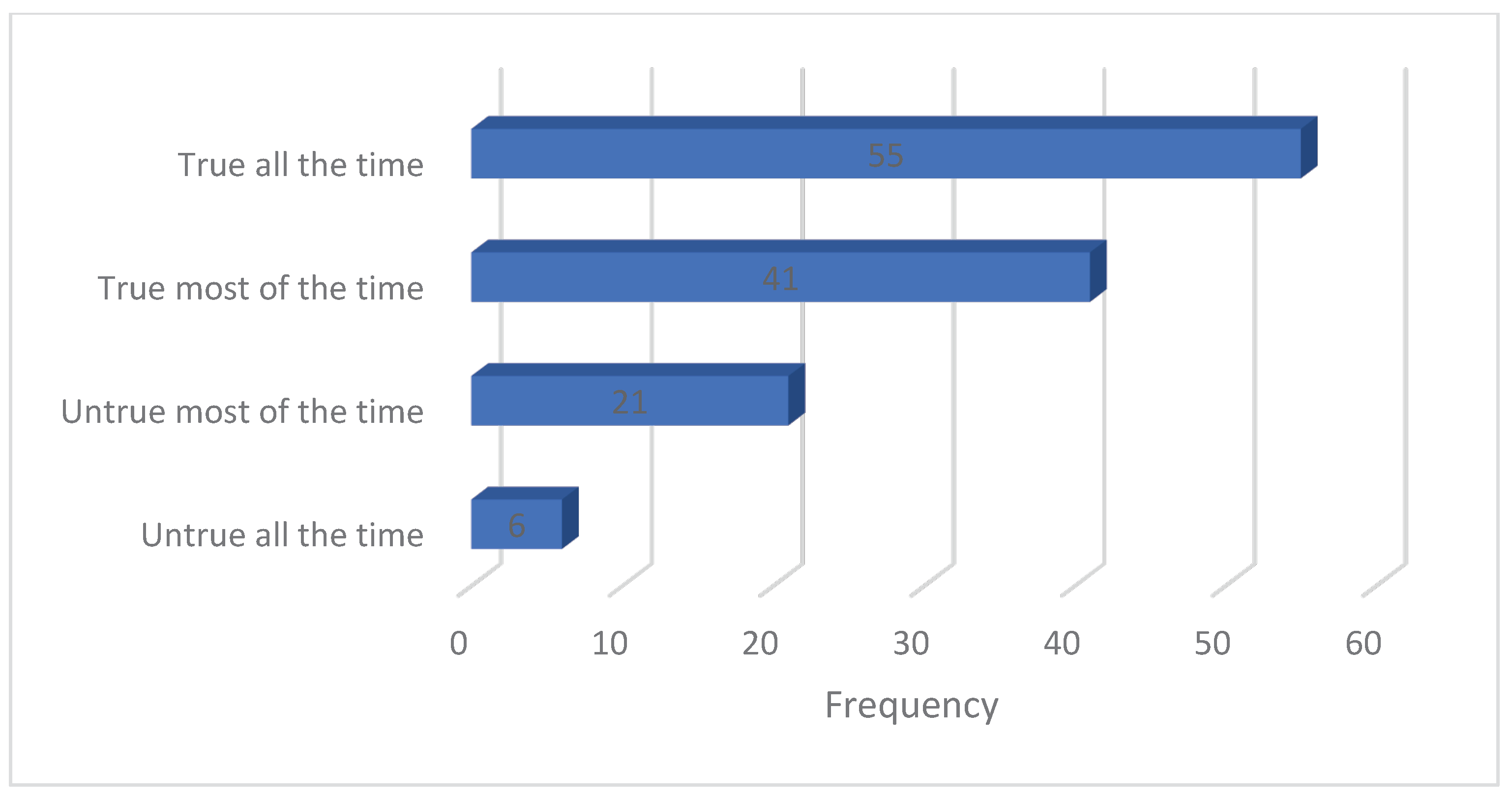

For the statement, "I know someone at the university who cares about me," in

Table 5, most respondents (44.7%) said it was true most of the time, with almost 27% believing it was true all of the time. Similarly, for the statement "I know someone at the university I can talk to," the majority (40.7%) said it was true most of the time, with approximately 28% saying it was true all of the time. These findings indicate that a sizeable proportion of respondents believe they have helpful ties that are approachable within the campus community. Furthermore, when it came to the statement, "I have good talents," a sizeable majority (52%) said it was true most of the time, with 30% believing it was true all of the time. There was an association between the respondents’ assertion to having good talents and age group (

= 13.030, p < 0.05). This demonstrates that respondents are confident in their abilities or strengths, reflecting a favourable self-perception in the academic setting. Overall, the findings show that students in the university setting have a generally favourable attitude on interpersonal connections, support networks, and self-esteem.

Factor 4 comprises of 4 items as shown in

Table 7 above, which appeared to measure students’ determination to achieve their goals. A follow-up reliability analysis found factor 4 to have acceptable internal consistency (α = .736).

The information in the

Table 7 provides a convincing peek into people's attitudes and beliefs about resilience, problem-solving, and optimism. Notably, most responders indicated strong positive feelings about perseverance and optimism. For example, when it comes to believing in a brighter future, an overwhelming 75.6% said they feel things would eventually improve for them, with another 22.8% saying they thought this most of the time. This largely positive view shows that the individuals had a resilient mindset. There was an association between the respondents’ belief in a brighter future one day and campus (

= 8.654, p < 0.05). Similarly, when it comes to problem-solving tactics, 61.8% reported adopting a variety of methods to solve difficult problems most of the time, emphasizing adaptation and flexibility in handling challenges. Furthermore, nearly half of the respondents (48.8%) stated that they do not allow people to obstruct their efforts, while 44.7% stated that they do so most of the time. There was also an association between the respondents’ assertion that they do not allow people to stop them from trying to do their best and gender (

= 7.948, p < 0.05). In terms of perseverance, an encouraging 49.6% said they never give up, with a further 42.3% saying they persevere most of the time. Overall, these findings indicate a prevalent attitude of resilience, determination, and a constructive view among those surveyed, emphasizing their tendency to persevere in the face of adversity while maintaining an optimistic outlook on their future possibilities.

Factor 5 comprises of 3 items as shown in

Table 8 above, which appeared to measure the support students receives from an adult Figure. A follow-up reliability analysis found factor 5 to have acceptable internal consistency (α = .778).

Table 8 shows that 83% of respondents had an adult to talk to most of the time or all of the time, compared to 17% who said they did not have an adult to talk to. Having an adult to talk to, had no association to campus, gender, nor age group. Furthermore, the majority (86%) of respondents answered that they have an adult who listens most or all of the time. In comparison, 3% and about 11% did not have such an adult all of the time or most of the time, respectively. There was no association found between having an adult who listens and being on a certain campus, age group nor gender. In terms of feeling safe and loved at home, nearly 95% of respondents said they felt so most or all of the time. Less than 1% and 4%, respectively, did not feel safe or loved at home all or most of the time. Gender was associated with feelings of safety and being loved at home (

= 8.973, p < 0.05).

Factor 6 consists of 3 items as shown in

Table 9 above, which appeared to measure students’ level of self-determination to achieve and inspiration from others. A follow-up reliability analysis found factor 6 to have poor internal consistency (α = .596).

Table 9 shows that a considerable proportion of participants showed a favourable inclination for emulation and inspiration, with 46.3% stating that they know a good person whose behaviour serves as an example to them, and a further 38.2% stating that they do so most of the time. Furthermore, when it comes to class attendance and dedication, a substantial majority (54.5%) expressed a strong preference for not being absent from class, with 38.2% indicating this preference most of the time. This reflects a general sense of dedication and importance placed on regular attendance among respondents. Furthermore, the data reveals a strong feeling of determination and persistence, with 47.2% of people saying they never give up trying, and another 42.3% saying they do so most of the time. Overall, the data indicate a favourable trend toward role model recognition, attendance commitment, and a resilient attitude among those surveyed, indicating a proactive and motivated approach to personal improvement and goal attainment.

Two questions items, namely right answer to a question and the believe whether students regard themselves as tough persons, were not grouped with any other following factor loadings. However, their response distribution is described next.