Submitted:

05 April 2024

Posted:

05 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

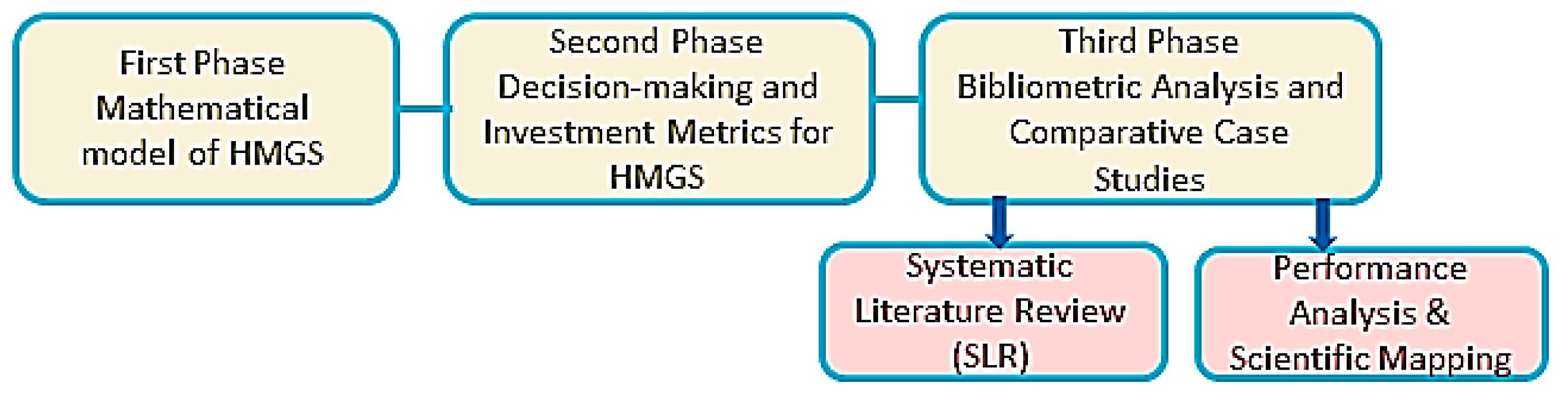

2. Methodological Framework

2.1. First phase: Mathematical model of HMGSs

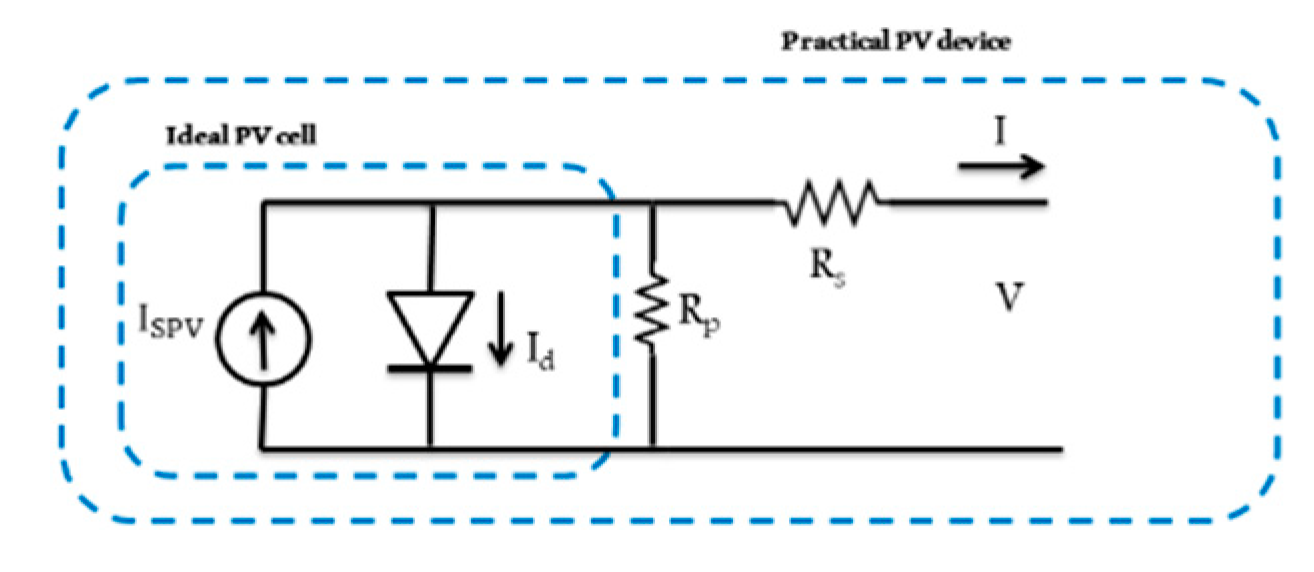

2.1.1. SPV system

- SPV: A solar cell, or photovoltaic (PV) cell, is a device that transforms light into electricity through the photovoltaic effect. The behavior of both an ideal SPV cell and a practical SPV device are typically represented in diagrams, such as those depicted in Figure 4.

- Charge controller: A charge controller, also known as a charge regulator or battery regulator, moderates the flow of electric current to and from the batteries. This control prevents excessive charging and voltage spikes, which can damage the battery, reduce its efficiency, or pose safety concerns. In SPV systems, solar charge controllers adjust the power or DC voltage coming from the solar panels before it is directed to the batteries.

- Inverter: Various inverter models exist, each tailored to the specific requirements of the load. The selection depends on the load's waveform needs and the inverter's efficiency. The choice is also influenced by whether the inverter is standalone or grid-connected. Inverter failure is a leading cause of malfunctions in SPV systems, presenting opportunities for engineers to improve inverter designs. The efficiency of an inverter is typically represented by the ratio of the output power to the input power, mathematically expressed as:

-

Battery: A battery bank within HMGSs serves dual purposes: as a power source and for energy storage, balancing power needs over time. Surplus energy from RESs is stored in the batteries, which then provide energy during low RESs output due to adverse weather. Battery size, determined by the autonomy days () and the difference between load demand () and power from RESs (), is calculated using:Where denotes the battery's efficiency and signifies the efficiency of the inverter, with referring to the depth of discharge [17].

2.1.2. Wind energy

2.1.3. Diesel generator

2.2. Second phase: Decision-making Tools and Investment Metrics for HMGSs

2.2.1. Decision-making Tools (LCOE, LCC, NPC, LPSP ,RF)

- Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE): LCOE represents the average cost per unit of energy produced by a system throughout its lifecycle, incorporating all lifecycle costs. It can be calculated as follows [20]:

- 2.

- Life Cycle Cost (LCC): LCC encompasses the total cost of ownership of the HMGS during its lifespan, including installation, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning costs but excluding system depreciation [21]. The LCC is calculated using the equation:

- 3.

- Net Present Cost (NPC): NPC calculates the present value of all costs and profits associated with the HMGS, offering a net-cost perspective over the system's lifecycle [22].

- 4.

- Loss of Power Supply Pprobability (LPSP): LPSP, defined as the ratio of the total time the system cannot meet the demanded load to the total observation period (often a year), indicates the likelihood of power outages. It may be computed using the generic formula:

- 5.

- Renewable Fraction (RF): RF quantifies the fraction of total energy provided by RESs in the HMGS, a key metric for assessing system sustainability [23].

2.2.2. Investment Metrics (NPV, EPBT, PBP, ROI)

- Net present value (NPV): calculates the profitability of a project by discounting future cash flows to the present.

- 2.

- Energy Payback Time (EPBT): determines how long a RE system takes to generate energy equal to its energy input over its lifespan. The EPBT formula is as follows:

- 3.

- Payback Period (PBP) assesses the time it takes for an investment to recoup its value through savings.

- 4.

- Return on Investment (ROI) measures profitability from an investor's perspective.

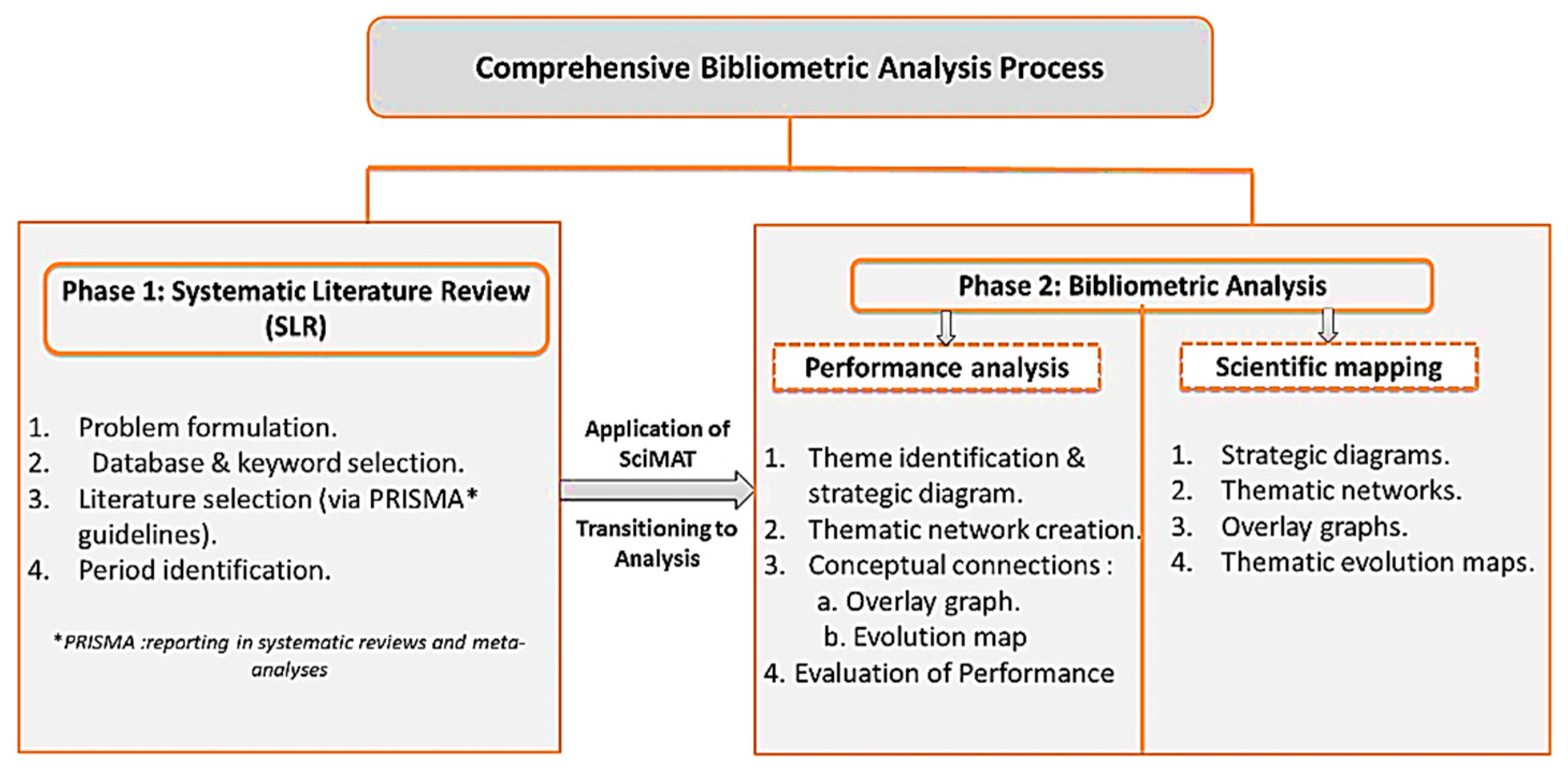

2.3. Third phase: Bibliometric Analysis and Comparative Case Studies

2.3.1. Bibliometric analysis

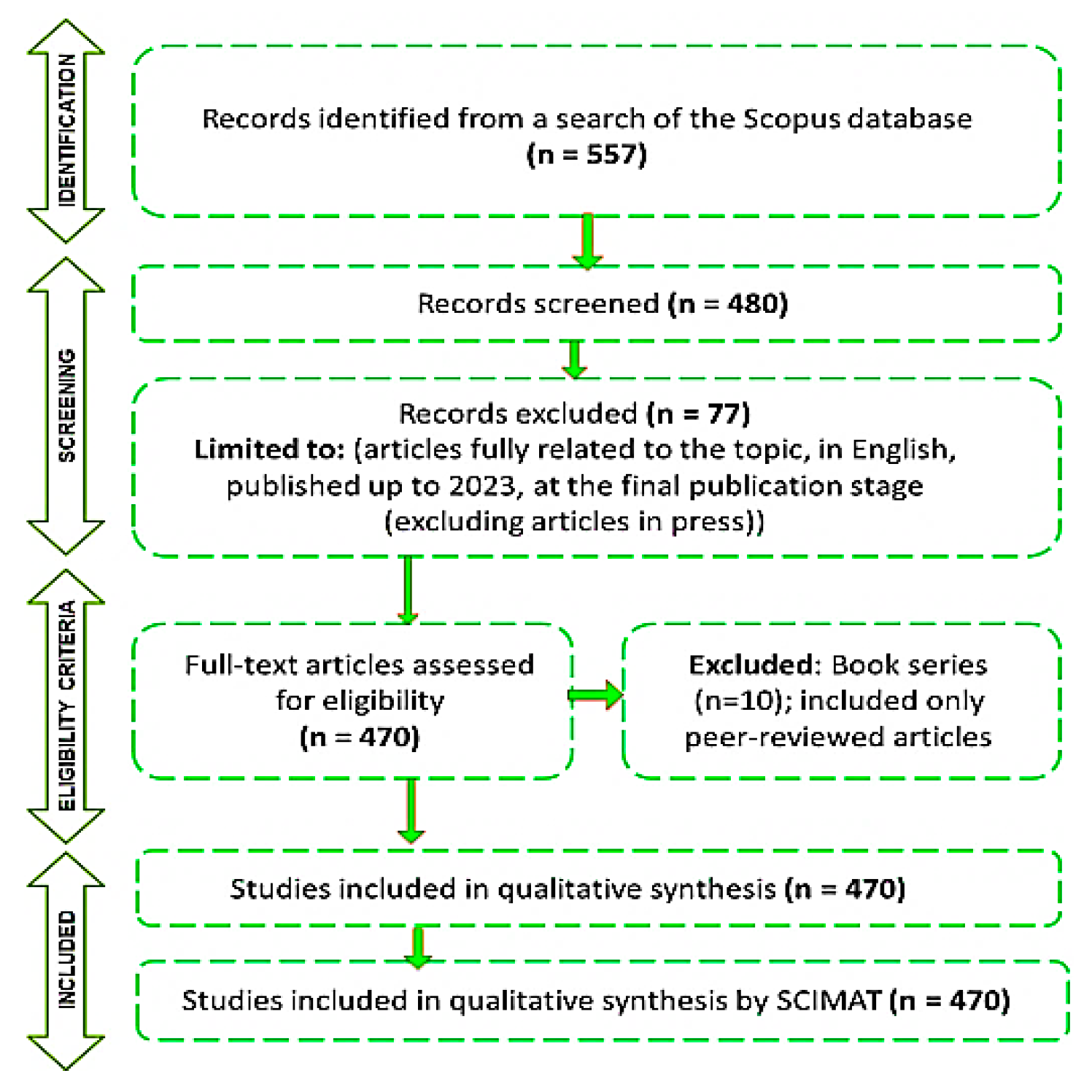

- Problem planning and formulation: This initial step establishes the foundation for the study, involving the framing of research questions, deciding on relevant literature criteria, methods for filtering unrelated findings, and outlining possible conclusions.

- Database(s), keywords, and search string determination: A range of databases was chosen, and a set of important terms identified for searching. Selecting appropriate terms is crucial to encompass varied research while remaining focused on relevant articles.

- Literature selection: At this stage, adherence to the PRISMA guidelines, which pertain to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, ensures the selected articles align with the study's direction [34]. Insights from these articles were systematically extracted.

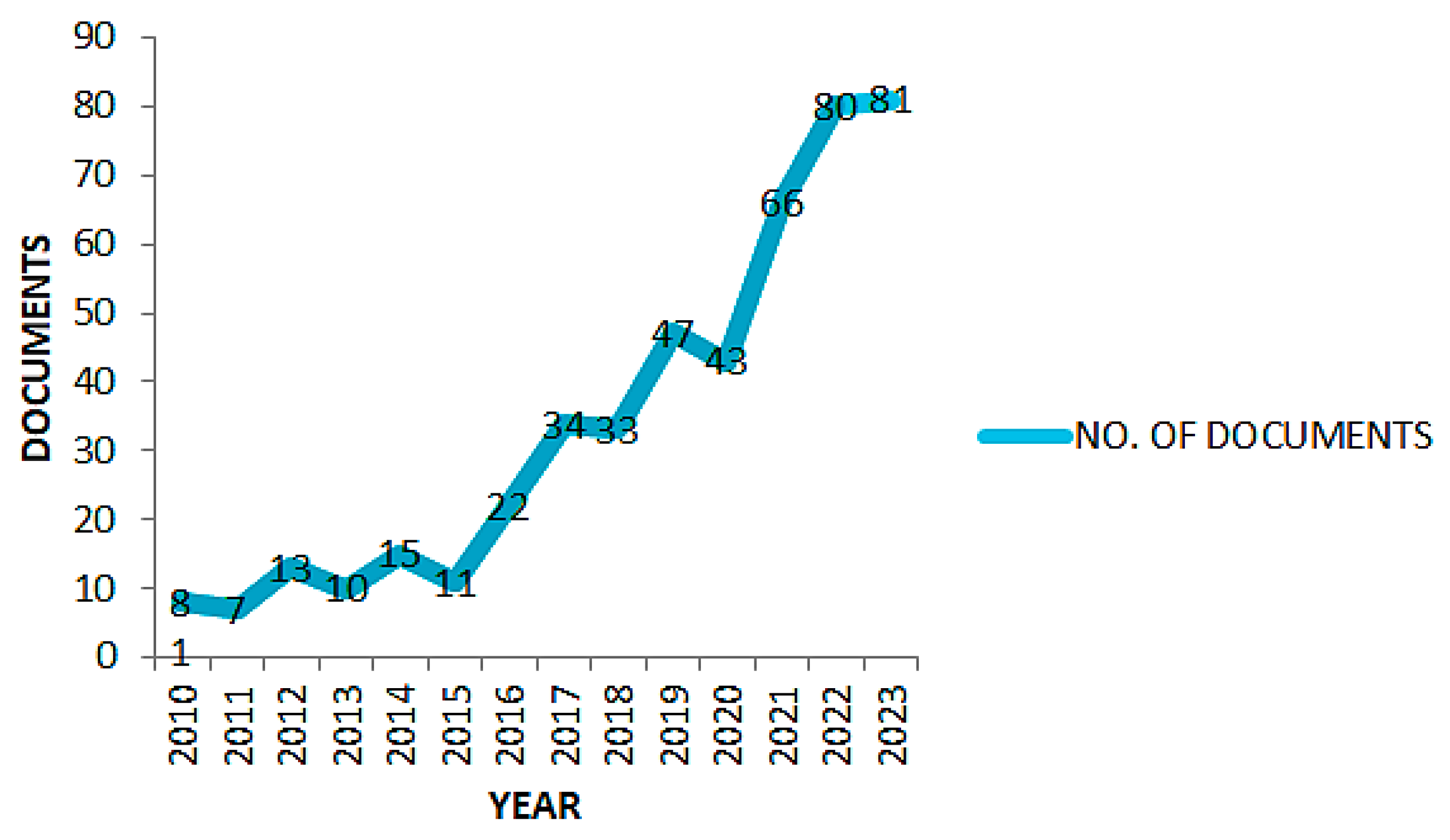

- Period identification: This step involves considering elements like the topic's depth, existing literature, and its evolution over time.

-

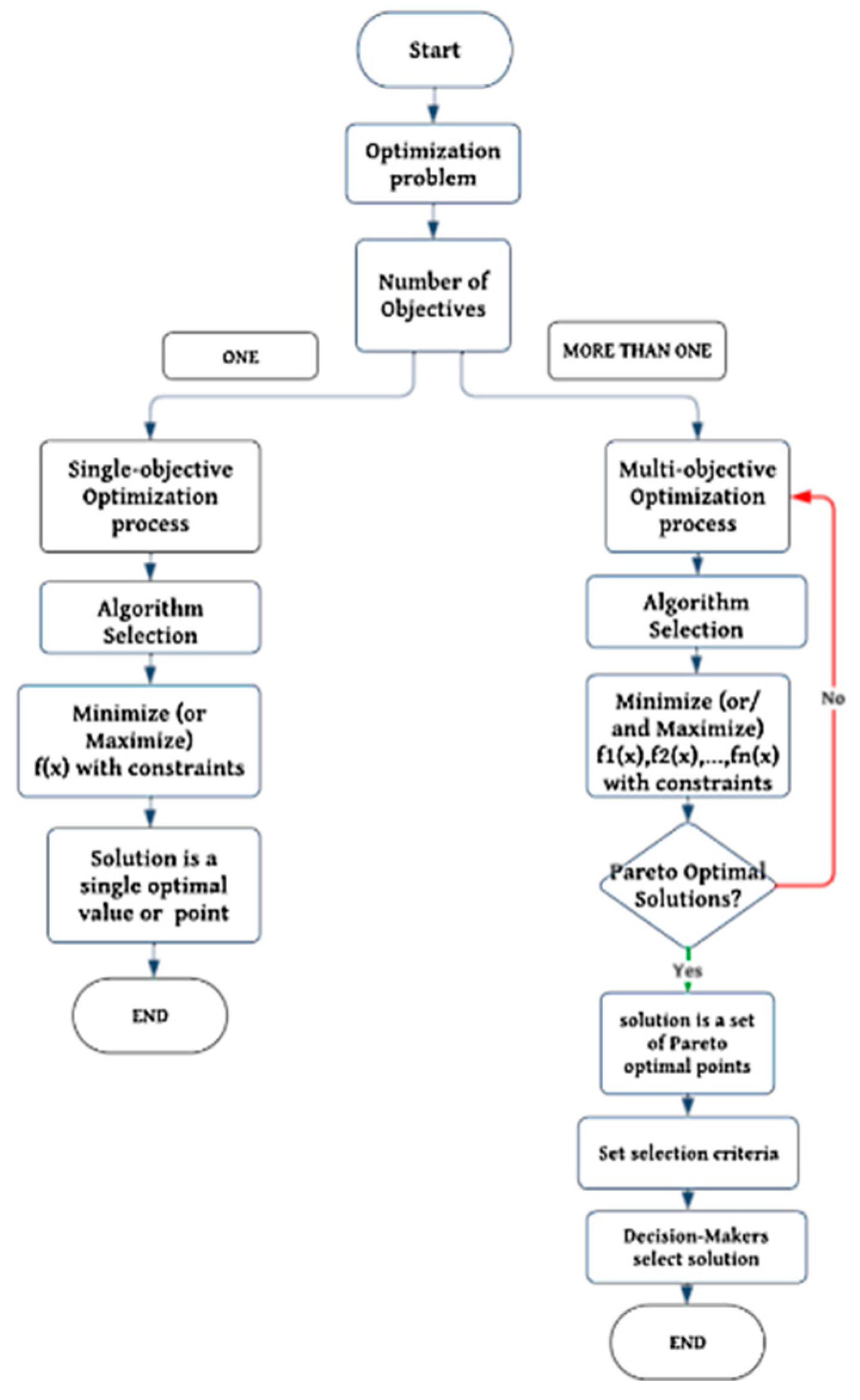

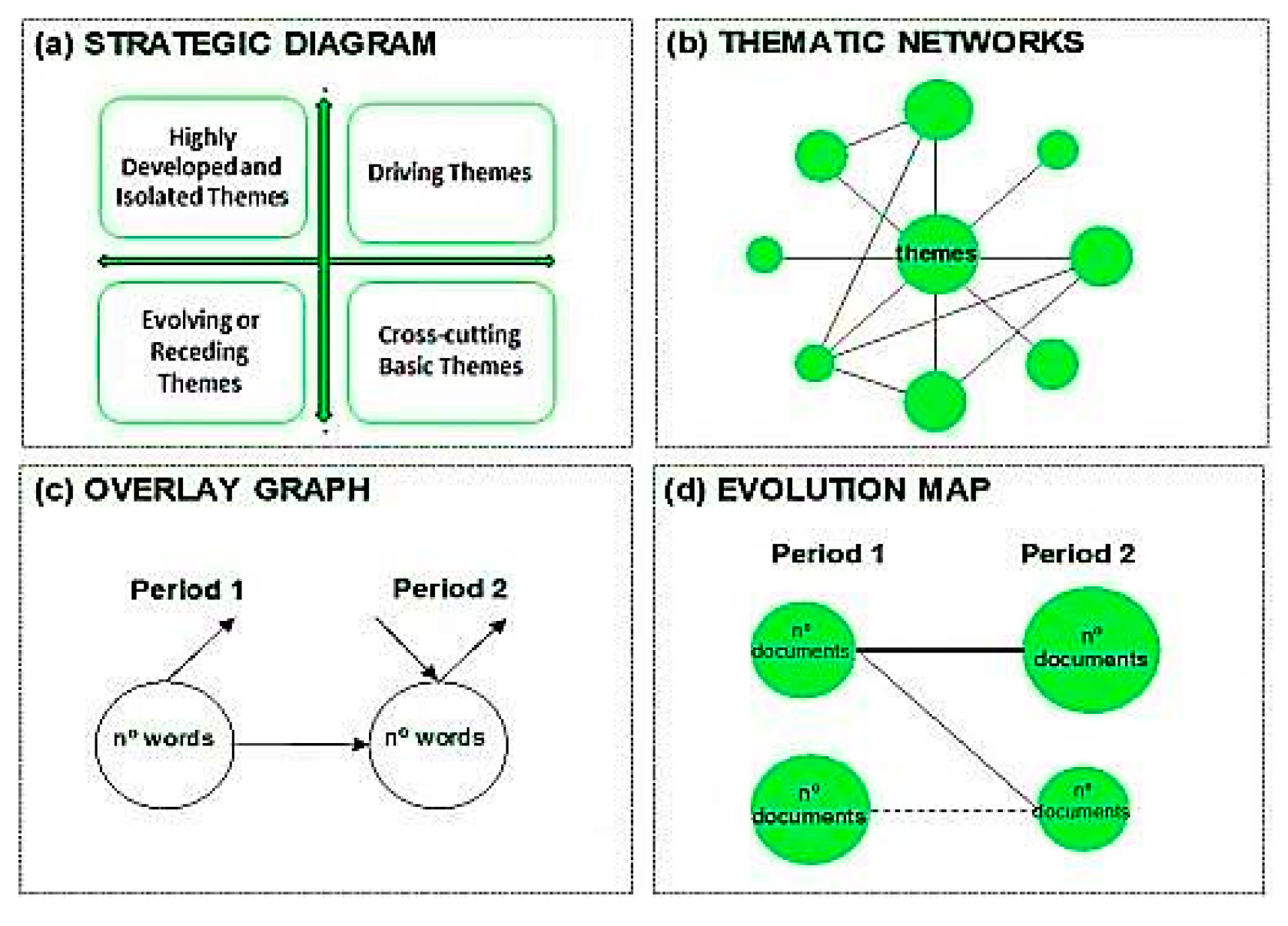

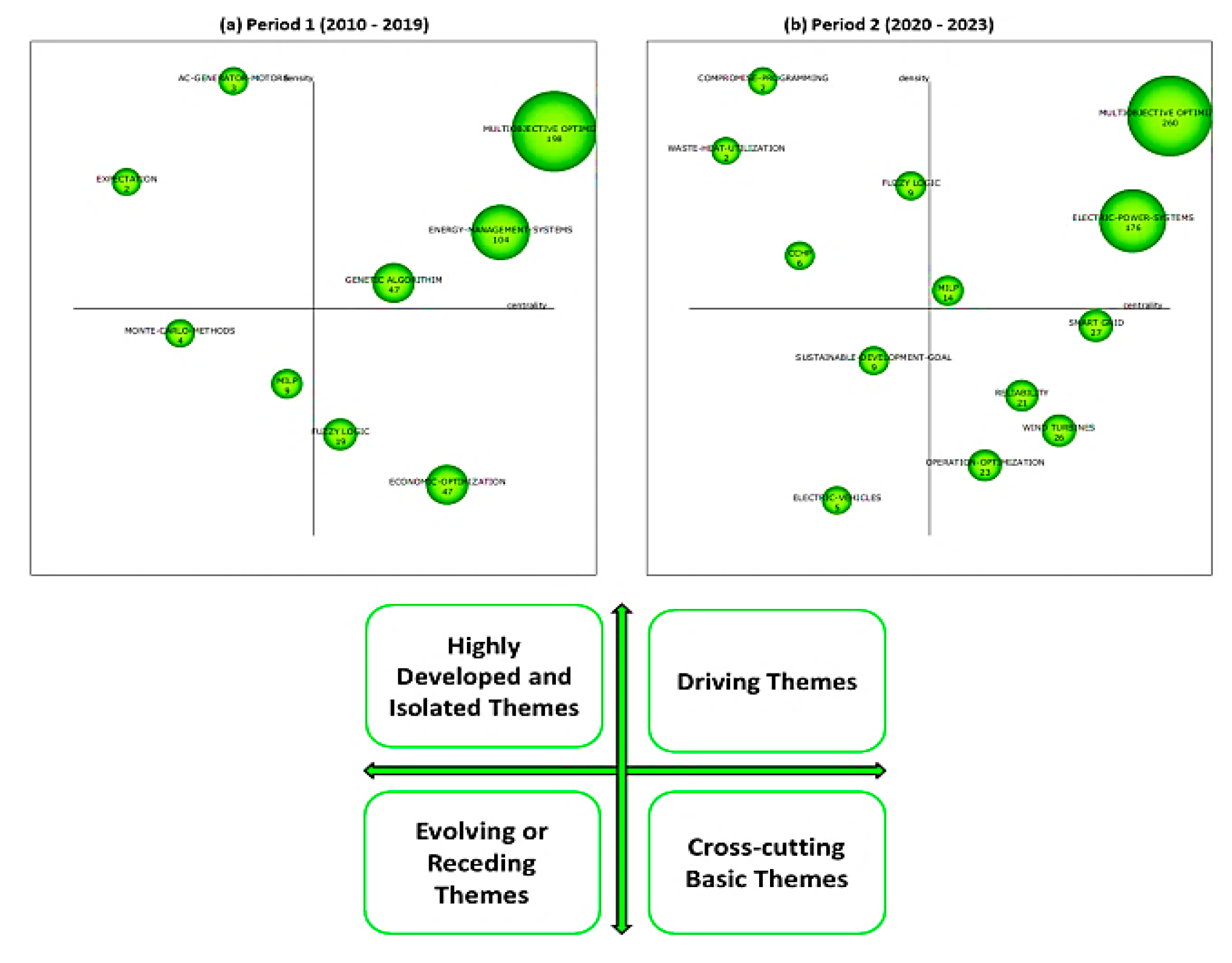

Theme identification and strategic diagram: Initially, the software sets up the equivalency index. It then employs a specific methodology to identify the most relevant topics. Subsequently, using the concepts of centrality and density, it strategizes for every theme, illustrating how the core research and related subjects are interconnected. Centrality refers to the degree of influence a theme has over others in the network. Themes with high centrality are vital and positioned on the right side of the diagram. Density analyzes the relationships between terms within a theme to determine its development level. Themes with high density are considered well-developed and placed toward the top of the diagram [35,36,37]. The diagrams, divided into four sections as shown in Figure 9, illustrate the various research topic categories:

- Driving themes: Important and well-understood subjects in the top right, essential for research growth.

- Highly developed and isolated themes: Topics that stand alone and are well-understood, found in the top left, specialized but separate from the main research.

- Evolving or receding themes: Topics in the bottom left that are not fully developed or currently significant. Their importance may increase or decrease in the future.

- Cross-cutting basic themes: Fundamental subjects important to the research but not yet fully developed, occupying the lower right section of the quadrant.

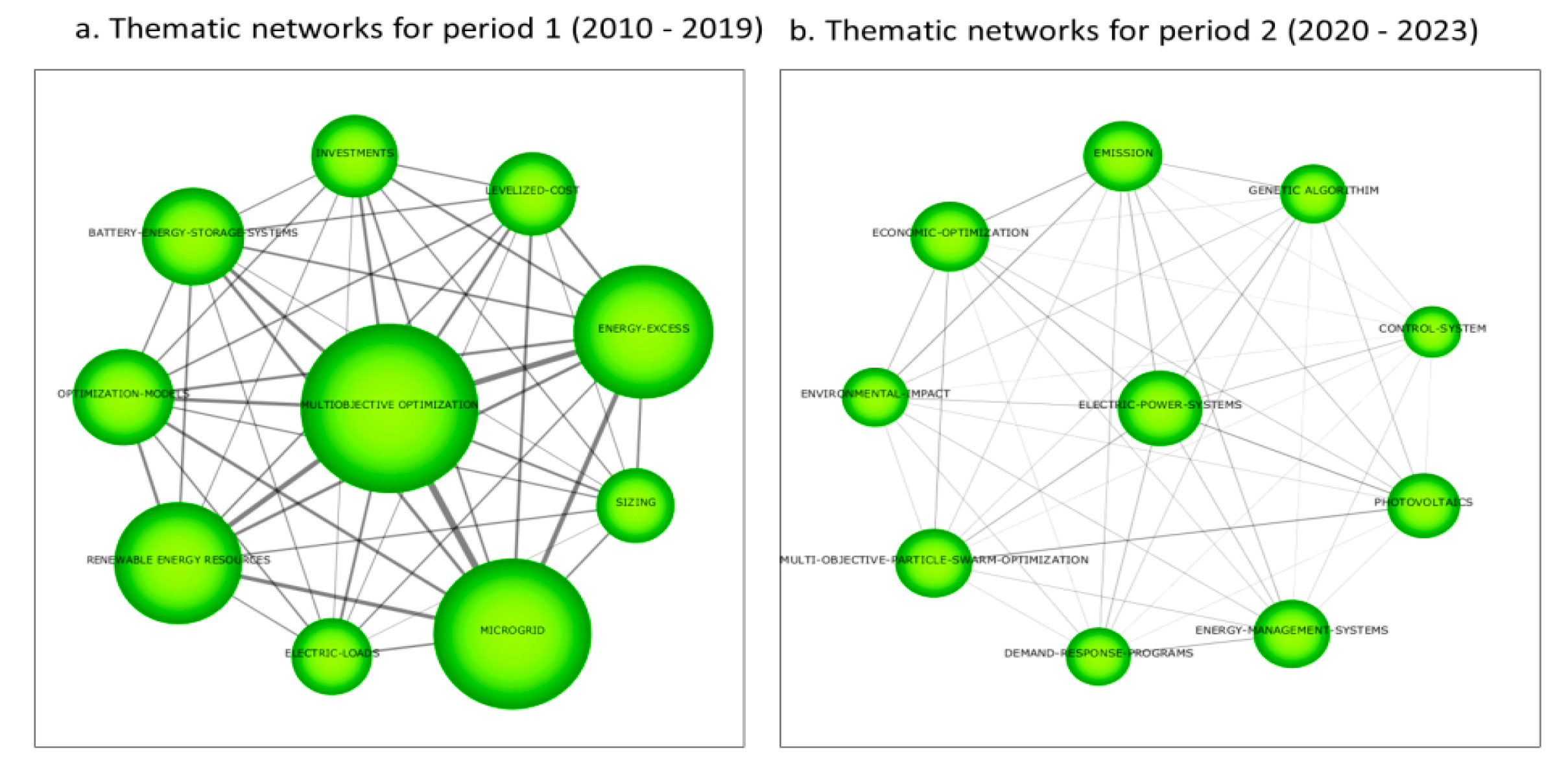

- Thematic Network Creation: This explores relationships between keywords and subjects to refine strategic diagrams. Each network depicted in Figure 9 is named after its principal keyword. The size of the circles indicates the number of associated papers, while the thickness of the links is determined by the equivalence index.

-

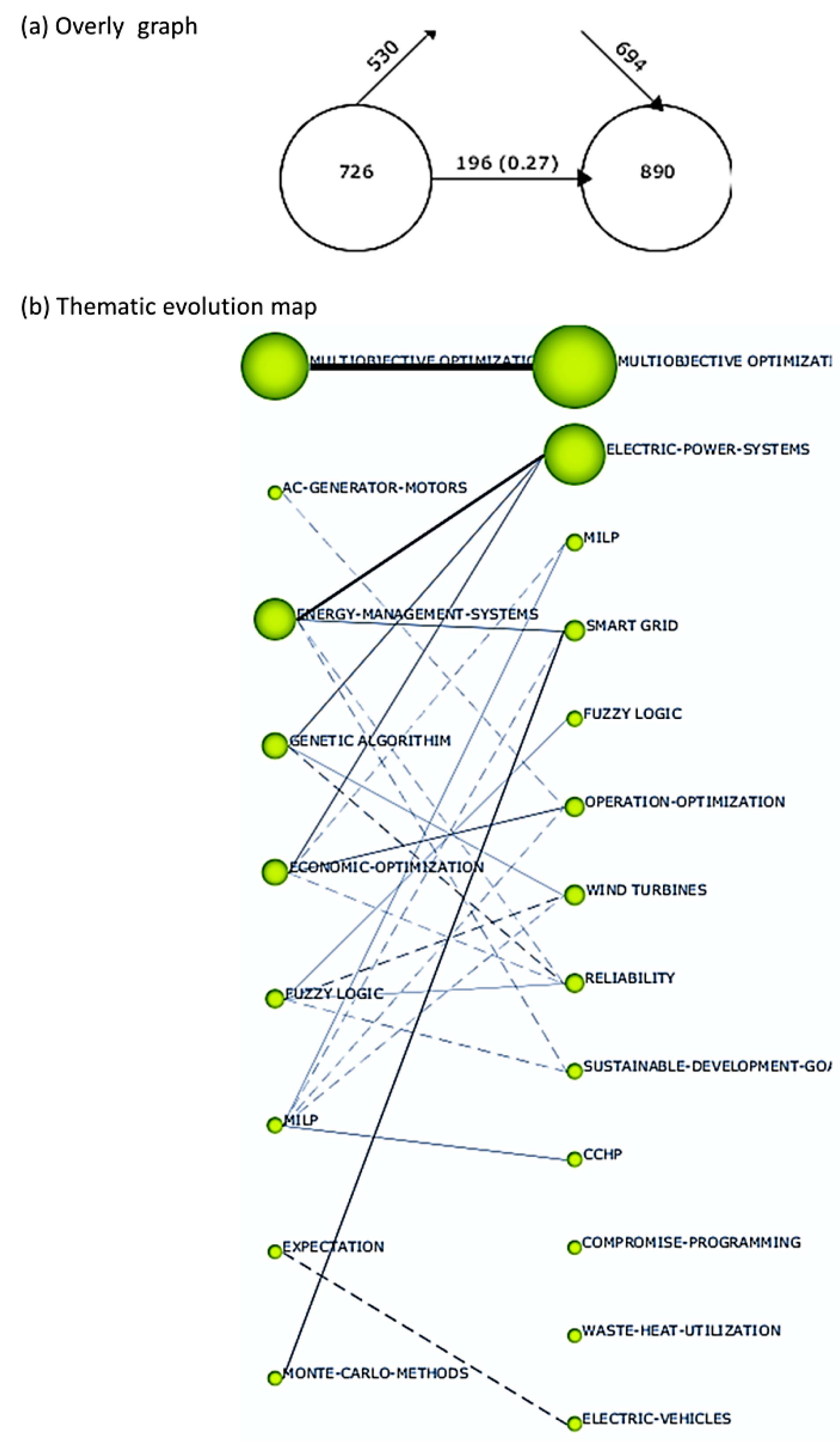

Conceptual Connections: The inclusion index [38] illustrates how themes are interconnected over time:

- Overlay Graph: Shows prevalent terms alongside keywords that have been added or removed over time.

- Thematic Evolution Map: Dotted lines represent sub-elements, and solid lines indicate connections to the primary theme. The size of circles and the thickness of lines signify the number of documents and the inclusion index, respectively.

- Evaluation of Performance: Evaluates research contributions using various metrics. It identifies leading subfields based on indicators such as the number of articles, citation counts, and variations in the h-index.

3. Findings and Analysis

3.1. SLR on the application of MOO for HMGSs

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis: Insights from Science Mapping and Performance Metrics

3.2.1. Strategic diagrams

3.2.2. Thematic networks

3.2.3. Graphical overlay and the evolution of theme mapping

3.2.4. Evaluation of Performance

4. Comparative Analysis of MOO in HMGs: Evaluating Techniques and Algorithms for Enhanced Performance and Sustainability

5. Conclusion

Funding

References

- I. Renewable Energy Agency and G. Renewables Alliance, “Global Renewables Alliance TRIPLING RENEWABLE POWER AND DOUBLING ENERGY EFFICIENCY BY 2030 CRUCIAL STEPS TOWARDS 1.5°C 3 2 0 0,” Accessed: Nov. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: www.globalrenewablesalliance.org/.

- Z. Z. Stanković et al., “The Volatility Dynamics of Prices in the European Power Markets during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period,” Sustain. 2024, Vol. 16, Page 2426, vol. 16, no. 6, p. 2426, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- I. - International Energy Agency, “World Energy Outlook 2023,” 2023, Accessed: Nov. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: www.iea.org/terms.

- P. Paliwal, N. P. Patidar, and R. K. Nema, “Planning of grid integrated distributed generators: A review of technology, objectives and techniques,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 40, pp. 557–570, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Deshmukh and S. S. Deshmukh, “Modeling of hybrid renewable energy systems,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 12, pp. 235–249, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Shivarama Krishna and K. Sathish Kumar, “A review on hybrid renewable energy systems,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 52, pp. 907–916, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Hemmati and H. Saboori, “Emergence of hybrid energy storage systems in renewable energy and transport applications – A review,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 65, pp. 11–23, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Ton and M. A. Smith, “The U.S. Department of Energy’s Microgrid Initiative,” Electr. J., vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 84–94, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Zia, E. Elbouchikhi, and M. Benbouzid, “Microgrids energy management systems: A critical review on methods, solutions, and prospects,” Appl. Energy, vol. 222, pp. 1033–1055, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Jha, N. Sharma, V. K. Jadoun, A. Agarwal, and A. Tomar, “Optimal scheduling of a microgrid using AI techniques,” Control Standalone Microgrid, pp. 297–336, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Arar Tahir, M. Zamorano, and J. Ordóñez García, “Scientific mapping of optimisation applied to microgrids integrated with renewable energy systems,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 145, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Kaabeche, M. Belhamel, and R. Ibtiouen, “Sizing optimization of grid-independent hybrid photovoltaic/wind power generation system,” Energy, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 1214–1222, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Li, D. W. Yue, H. X. Liu, and Y. F. Liu, “Wind-solar complementary power inverter based on intelligent control,” 2009 4th IEEE Conf. Ind. Electron. Appl. ICIEA 2009, pp. 3635–3638, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Cagnano, E. De Tuglie, and P. Mancarella, “Microgrids: Overview and guidelines for practical implementations and operation,” Appl. Energy, vol. 258, p. 114039, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Fusheng, L. Ruisheng, and Z. Fengquan, “Microgrid technology and engineering application,” Microgrid Technol. Eng. Appl., pp. 1–198, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Sumathi, L. Ashok Kumar, P.Surekha, “Solar Photovoltaic & Wind Energy Conversion Systems.” p. 807, 2015, [Online]. Available: internal-pdf://0380800788/Solar PV & Wind E Conversion Systems 2015.pdf.

- M. Azaza and F. Wallin, “Multi objective particle swarm optimization of hybrid micro-grid system: A case study in Sweden,” Energy, vol. 123, pp. 108–118, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang and C. Singh, “PSO-based multi-criteria optimum design of a grid-connected hybrid power system with multiple renewable sources of energy,” Proc. 2007 IEEE Swarm Intell. Symp. SIS 2007, pp. 250–257, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Ashari and C. V Nayar, “AN OPTIMUM DISPATCH STRATEGY USING SET POINTS FOR A PHOTOVOLTAIC (PV)-DIESEL-BATTERY HYBRID POWER SYSTEM †,” vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 1999, Accessed: Mar. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: www.elsevier.com/locate/solener.

- M. Bruck and P. Sandborn, “Pricing bundled renewable energy credits using a modified LCOE for power purchase agreements,” Renew. Energy, vol. 170, pp. 224–235, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Ma, H. Yang, and L. Lu, “Study on stand-alone power supply options for an isolated community,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 65, pp. 1–11, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Tsai, T. M. Beza, E. M. Molla, and C. C. Kuo, “Analysis and Sizing of Mini-Grid Hybrid Renewable Energy System for Islands,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 70013–70029, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Hiendro, I. Yusuf, F. Trias, P. Wigyarianto, H. Kho, and J. Khwee, “Optimum Renewable Fraction for Grid-connected Photovoltaic in Office Building Energy Systems in Indonesia,” Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst., vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1866–1874, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Murphy and C. A. S. Hall, “Year in review-EROI or energy return on (energy) invested,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., vol. 1185, pp. 102–118, 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. A. S. Hall, J. G. Lambert, and S. B. Balogh, “EROI of different fuels and the implications for society,” Energy Policy, vol. 64, pp. 141–152, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “Payback - Energy Education.” https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Payback (accessed Feb. 19, 2024).

- K. Deb, “Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms: An Introduction,” 2011, Accessed: Oct. 29, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.iitk.ac.in/kangal/deb.htm.

- H. Y. Alhammadi and J. A. Romagnoli, “Process design and operation: Incorporating environmental, profitability, heat integration and controllability considerations,” Comput. Aided Chem. Eng., vol. 17, no. C, pp. 264–305, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Z. N. Pintarič and Z. Kravanja, “Suitable Process Modelling for Proper Multi-Objective Optimization of Process Flow Sheets,” Comput. Aided Chem. Eng., vol. 33, pp. 1387–1392, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. A. M. Ramli, H. R. E. H. Bouchekara, and A. S. Alghamdi, “Optimal sizing of PV/wind/diesel hybrid microgrid system using multi-objective self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm,” Renew. Energy, vol. 121, pp. 400–411, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Niknam, R. Azizipanah-Abarghooee, and M. R. Narimani, “An efficient scenario-based stochastic programming framework for multi-objective optimal micro-grid operation,” Appl. Energy, vol. 99, pp. 455–470, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Chaouachi, R. M. Kamel, R. Andoulsi, and K. Nagasaka, “Multiobjective Intelligent Energy Management for a Microgrid,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 60, no. 4, 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Donthu, S. Kumar, D. Mukherjee, N. Pandey, and W. M. Lim, “How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 133, pp. 285–296, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Liberati et al., “The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration,” BMJ, vol. 339, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Martínez, M. J. Cobo, M. Herrera, and E. Herrera-Viedma, “Analyzing the Scientific Evolution of Social Work Using Science Mapping:”. vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 257–277, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Cobo, A. G. López-Herrera, E. Herrera-Viedma, and F. Herrera, “An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field,” J. Informetr., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 146–166, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Callon, J. P. Courtial, and F. Laville, “Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemsitry,” Sci. 1991 221, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 155–205, Sep. 1991. [CrossRef]

- C. Díaz-López, M. Carpio, M. Martín-Morales, and M. Zamorano, “Analysis of the scientific evolution of sustainable building assessment methods,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 49, p. 101610, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “SDG Indicators — SDG Indicators.” https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/ (accessed Mar. 14, 2024).

- E. Naderi, A. Dejamkhooy, S. J. Seyedshenava, and H. Shayeghi, “MILP based Optimal Design of Hybrid Microgrid by Considering Statistical Wind Estimation and Demand Response,” J. Oper. Autom. Power Eng., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 54–65, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Karimi and S. Jadid, “Optimal energy management for multi-microgrid considering demand response programs: A stochastic multi-objective framework,” Energy, vol. 195, p. 116992, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Vivas et al., “Multi-Objective Fuzzy Logic-Based Energy Management System for Microgrids with Battery and Hydrogen Energy Storage System,” Electron. 2020, Vol. 9, Page 1074, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 1074, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Shadmand and R. S. Balog, “Multi-objective optimization and design of photovoltaic-wind hybrid system for community smart DC microgrid,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 2635–2643, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Sanseverino, M. L. Di Silvestre, M. G. Ippolito, A. De Paola, and G. Lo Re, “An execution, monitoring and replanning approach for optimal energy management in microgrids,” Energy, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 3429–3436, 11. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- R. Ghasemi, M. Wosnik, D. L. Foster, and W. Mo, “Multi-Objective Decision-Making for an Island Microgrid in the Gulf of Maine,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 18, p. 13900, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Lokeshgupta and S. Sivasubramani, “Optimal operation of a residential microgrid with demand side management,” Proc. 2019 IEEE PES Innov. Smart Grid Technol. Eur. ISGT-Europe 2019, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Haddadian and R. Noroozian, “Multi-Microgrid-Based Operation of Active Distribution Networks Considering Demand Response Programs,” IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1804–1812, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. V. N. M. Krishna and P. C. Sekhar, “Area Constrained Optimal Planning Model of Renewable-Rich Hybrid Microgrid,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 70873–70883, 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2023 – Analysis - IEA.” https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023 (accessed Feb. 15, 2024).

- Z. Mu, F. Zhao, F. Bai, Z. Liu, and H. Hao, “Evaluating Fuel Cell vs. Battery Electric Trucks: Economic Perspectives in Alignment with China’s Carbon Neutrality Target,” Sustain. 2024, Vol. 16, Page 2427, vol. 16, no. 6, p. 2427, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Momen, J. Nikoukar, and M. Gandomkar, “Multi-objective Optimization of Energy Consumption in Microgrids Considering CHPs and Renewables Using Improved Shuffled Frog Leaping Algorithm,” J. Electr. Eng. Technol., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1539–1555, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, J. Huang, Y. Liu, H. Wang, Y. Wang, and X. Ai, “A Multicriteria Optimal Operation Framework for a Data Center Microgrid Considering Renewable Energy and Waste Heat Recovery: Use of Balanced Decision Making,” IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag., vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 23–38, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Heat Pumps - Energy System - IEA.” https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings/heat-pumps#tracking (accessed Feb. 15, 2024).

- P. Martínez Fernández, I. Villalba Sanchís, V. Yepes, and R. Insa Franco, “A review of modelling and optimisation methods applied to railways energy consumption,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 222, pp. 153–162, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Aghajani, H. A. Shayanfar, and H. Shayeghi, “Presenting a multi-objective generation scheduling model for pricing demand response rate in micro-grid energy management,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 106, pp. 308–321, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. K. Zand, K. Mazlumi, A. Bagheri, and H. Hashemi-Dezaki, “Optimal Protection Scheme for Enhancing AC Microgrids Stability against Cascading Outages by Utilizing Events Scale Reduction Technique and Fuzzy Zero-Violation Clustering Algorithm,” Sustain. 2023, Vol. 15, Page 15550, vol. 15, no. 21, p. 15550, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. L. V. Eriksson and E. M. A. Gray, “Optimization and integration of hybrid renewable energy hydrogen fuel cell energy systems – A critical review,” Appl. Energy, vol. 202, pp. 348–364, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Moghaddam, A. Seifi, T. Niknam, and M. R. Alizadeh Pahlavani, “Multi-objective operation management of a renewable MG (micro-grid) with back-up micro-turbine/fuel cell/battery hybrid power source,” Energy, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 6490–6507, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, W. Cao, D. Wang, and M. Ding, “A Multi-Objective Optimization Dispatch Method for Microgrid Energy Management Considering the Power Loss of Converters,” Energies 2019, Vol. 12, Page 2160, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 2160, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Salehi, H. Martinez-Garcia, G. Velasco-Quesada, and J. M. Guerrero, “A Comprehensive Review of Control Strategies and Optimization Methods for Individual and Community Microgrids,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 15935–15955, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Moradi, M. Abedini, S. M. R. Tousi, and S. M. Hosseinian, “Optimal siting and sizing of renewable energy sources and charging stations simultaneously based on Differential Evolution algorithm,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 73, pp. 1015–1024, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Mansouri, A. Ahmarinejad, E. Nematbakhsh, M. S. Javadi, A. R. Jordehi, and J. P. S. Catalão, “Energy management in microgrids including smart homes: A multi-objective approach,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 69, p. 102852, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Motevasel and A. R. Seifi, “Expert energy management of a micro-grid considering wind energy uncertainty,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 83, pp. 58–72, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Rezvani, M. Gandomkar, M. Izadbakhsh, and A. Ahmadi, “Environmental/economic scheduling of a micro-grid with renewable energy resources,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 216–226, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. S. Gazijahani and J. Salehi, “Stochastic multi-objective framework for optimal dynamic planning of interconnected microgrids,” IET Renew. Power Gener., vol. 11, no. 14, pp. 1749–1759, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Das et al., “Multi-objective techno-economic-environmental optimisation of electric vehicle for energy services,” Appl. Energy, vol. 257, p. 113965, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Fang, Y. Xu, Z. Li, T. Zhao, and H. Wang, “Two-Step Multi-Objective Management of Hybrid Energy Storage System in All-Electric Ship Microgrids,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 3361–3373, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Hemeida et al., “Multi-objective multi-verse optimization of renewable energy sources-based micro-grid system: Real case,” Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 101543, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. De, G. Das, and K. K. Mandal, “An effective energy flow management in grid-connected solar–wind-microgrid system incorporating economic and environmental generation scheduling using a meta-dynamic approach-based multiobjective flower pollination algorithm,” Energy Reports, vol. 7, pp. 2711–2726, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Flexible Scheduling of Microgrid with Uncertainties Considering Expectation and Robustness,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 3009–3018, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Xie, Z. Cai, P. Liu, X. Li, Y. Zhang, and D. Xu, “Microgrid System Energy Storage Capacity Optimization Considering Multiple Time Scale Uncertainty Coupling,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 5234–5245, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiong, P. Li, Z. Wang, and J. Wang, “Multi-agent based multi objective renewable energy management for diversified community power consumers,” Appl. Energy, vol. 259, p. 114140, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Graditi, M. L. Di Silvestre, R. Gallea, and E. R. Sanseverino, “Heuristic-based shiftable loads optimal management in smart micro-grids,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 271–280, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Yan et al., “A Novel, Stable, and Economic Power Sharing Scheme for an Autonomous Microgrid in the Energy Internet,” Energies 2015, Vol. 8, Pages 12741-12764, vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 12741–12764, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Chaouachi, R. M. Kamel, R. Andoulsi, and K. Nagasaka, “Multiobjective intelligent energy management for a microgrid,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 1688–1699, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Aghajani and N. Ghadimi, “Multi-objective energy management in a micro-grid,” Energy Reports, vol. 4, pp. 218–225, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Borhanazad, S. Mekhilef, V. Gounder Ganapathy, M. Modiri-Delshad, and A. Mirtaheri, “Optimization of micro-grid system using MOPSO,” Renew. Energy, vol. 71, pp. 295–306, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Basu, A. Bhattacharya, S. Chowdhury, and S. P. Chowdhury, “Planned scheduling for economic power sharing in a CHP-based micro-grid,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 30–38, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Nazari-Heris, S. Abapour, and B. Mohammadi-Ivatloo, “Optimal economic dispatch of FC-CHP based heat and power micro-grids,” Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 114, pp. 756–769, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, Q. Li, R. Ding, M. Sun, and G. Wang, “Integrated scheduling of energy supply and demand in microgrids under uncertainty: A robust multi-objective optimization approach,” Energy, vol. 130, pp. 1–14, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Jahangir, A. Ahmadian, and M. A. Golkar, “Multi-objective sizing of grid-connected micro-grid using Pareto front solutions,” Proc. 2015 IEEE Innov. Smart Grid Technol. - Asia, ISGT ASIA 2015, pp. 1–6, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Borhanazad, S. Mekhilef, V. Gounder Ganapathy, M. Modiri-Delshad, and A. Mirtaheri, “Optimization of micro-grid system using MOPSO,” Renew. Energy, vol. 71, pp. 295–306, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Motevasel, A. R. Seifi, and T. Niknam, “Multi-objective energy management of CHP (combined heat and power)-based micro-grid,” Energy, vol. 51, pp. 123–136, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Kanchev, D. Lu, B. Francois, and V. Lazarov, “Smart monitoring of a microgrid including gas turbines and a dispatched PV-based active generator for energy management and emissions reduction,” IEEE PES Innov. Smart Grid Technol. Conf. Eur. ISGT Eur., 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Roldán-Blay, G. Escrivá-Escrivá, C. Roldán-Porta, and D. Dasí-Crespo, “Optimal sizing and design of renewable power plants in rural microgrids using multi-objective particle swarm optimization and branch and bound methods,” Energy, vol. 284, p. 129318, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Belboul et al., “Multiobjective Optimization of a Hybrid PV/Wind/Battery/Diesel Generator System Integrated in Microgrid: A Case Study in Djelfa, Algeria,” Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 3579, vol. 15, no. 10, p. 3579, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Shan and R. X. Lu, “Multi-objective economic optimization scheduling of CCHP micro-grid based on improved bee colony algorithm considering the selection of hybrid energy storage system,” Energy Reports, vol. 7, pp. 326–341, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Ding, W. Sun, G. P. Harrison, X. Lv, and Y. Weng, “Multi-objective optimization for an integrated renewable, power-to-gas and solid oxide fuel cell/gas turbine hybrid system in microgrid,” Energy, vol. 213, p. 118804, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, Z. Qi, F. Yang, and X. Li, “The Multi-Objective Optimal Configuration of Wind-PV-Battery Microgrid,” Proc. - 2020 Chinese Autom. Congr. CAC 2020, pp. 5585–5590, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Renewable energy systems (RESs) | Hybrid energy systems (HRESs) |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Weather dependent, it can be less reliable. | More consistent power supplies reduce reliance on a single source. |

| Economic | Higher initial cost, lower long-term operational costs. | More cost-effective long-term due to optimized resource use |

| Security | Reduces reliance on imported fuels, but sensitive to environmental changes. | Enhanced security through diversified energy sources. |

| Environment | Minimal emissions, low environmental impact. | Potentially lower impact through optimized energy mix. |

| Maintenance Requirements | Regular maintenance needed, varies by technology. | Potentially more complex maintenance due to multiple systems but can be optimized for efficiency. |

| Stability | Can be unstable due to reliance on single energy source. | Generally more stable due to diversified energy sources. |

| Technological Advancement | Dependent on specific technology advancements. | Benefits from advancements in multiple technologies. |

| Geographical Suitability | Depends on local resource availability. | Better adaptability to various geographical conditions. |

| Energy Storage and Distribution | Storage solutions required for inconsistent supply. | More efficient storage and distribution with steady supply. |

| Period 1 (2010-2019) | |||||

| Name of Clusters | Documents count | h- index | Citations count | Centrality | Density |

| Multiobjective optimization | 198 | 51 | 9,630 | 373.74 | 131.48 |

| Ac-generator-motors | 3 | 3 | 16 | 59.44 | 242.5 |

| Energy-management-systems | 104 | 43 | 7,351 | 226.49 | 24.94 |

| Genetic algorithm | 47 | 19 | 2,956 | 126.1 | 19.49 |

| Economic-optimization | 47 | 20 | 2,630 | 134.23 | 8.16 |

| Fuzzy logic | 19 | 11 | 1,839 | 89.02 | 9.76 |

| MILP | 9 | 7 | 472 | 70.22 | 10.63 |

| Expectation | 2 | 1 | 13 | 6.49 | 44.44 |

| Monte-Carlo-methods | 4 | 4 | 177 | 8.82 | 16.67 |

| Period 2 (2020-2023) | |||||

| Name of Clusters | Documents count | h- index | Citations count | Centrality | Density |

| Multiobjective optimization | 260 | 30 | 3,347 | 363.59 | 135.68 |

| Electric-power-systems | 176 | 29 | 2,795 | 245.16 | 25.61 |

| MILP | 14 | 9 | 436 | 46.55 | 9.67 |

| Smart grid | 27 | 14 | 686 | 65.42 | 8.09 |

| Fuzzy logic | 9 | 5 | 193 | 39.26 | 47.41 |

| Operation-optimization | 23 | 9 | 324 | 48.7 | 4.23 |

| Wind turbines | 26 | 9 | 381 | 61.39 | 4.34 |

| Reliability | 21 | 12 | 365 | 54.4 | 4.84 |

| Sustainable-development-goal | 9 | 5 | 116 | 24.09 | 6.92 |

| CCHP | 6 | 4 | 101 | 16.65 | 19.67 |

| Compromise-programming | 2 | 1 | 6 | 5.73 | 150 |

| Waste-heat-utilization | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2.81 | 77.78 |

| Electric-vehicles | 5 | 3 | 121 | 17.9 | 3.45 |

| Name of the journal | Documents count | Total citations | Most cited document | Citations count |

| Energy | 26 | 2391 | [58] | 490 |

| Energies | 24 | 264 | [59] | 29 |

| IEEE Access | 22 | 265 | [60] | 41 |

| Applied Energy | 17 | 1449 | [31] | 357 |

| International Journal Of Electrical Power And Energy Systems | 15 | 443 | [61] | 121 |

| Renewable Energy | 10 | 905 | [30] | 360 |

| Sustainable Cities And Society | 10 | 386 | [62] | 121 |

| Energy Conversion And Management | 10 | 609 | [63] | 200 |

| journal of cleaner production | 9 | 338 | [64] | 164 |

| IET Renewable Power Generation | 8 | 271 | [65] | 96 |

| Authors’ names | Documents count | Total citations | h-index | Most cited document | Citations count |

| Yue Wang | 8 | 186 | 12 | [66] | 128 |

| Hongdong Wang | 8 | 130 | 12 | [67] | 102 |

| Josep M. Guerrero | 8 | 131 | 130 | [60] | 41 |

| Tomnobu Senjyu | 6 | 57 | 9 | [68] | 33 |

| Meenakshi De | 6 | 57 | 5 | [69] | 20 |

| Yuanzheng Li | 6 | 25 | 31 | [70] | 12 |

| Yongjun Zhang | 6 | 71 | 30 | [71] | 34 |

| Ziqiang Wang | 6 | 101 | 14 | [72] | 52 |

| Maria Luisa Di Silvestre | 6 | 445 | 22 | [73] | 147 |

| Hesen Liu | 6 | 53 | 9 | [74] | 27 |

| Authors’ names | Year | Citation counts | Most cited document |

| Chaouachi, A., Kamel, R.M. Andoulsi, R, Nagasaka, K. |

2013 | 545 | [75] |

| Niknam, T., Moghaddam, A.A., Seifi, A., Alizadeh Pahlavani, M.R. | 2011 | 490 | [58] |

| Ramli, M.A.M., Bouchekara, H.R.E.H., Alghamdi, A.S. | 2018 | 360 | [30] |

| Niknam, T., Azizipanah Abarghooee, R, Narimani, M.R. | 2012 | 357 | [31] |

| Aghajani, G., Ghadimi, N. | 2018 | 347 | [76] |

| Borhanazad, H., Gounder Ganapathy, V., Mekhilef, S., Mirtaheri, A., Modiri-Delshad, M. | 2014 | 342 | [77] |

| Eriksson, E.L.V., Gray, E. | 2017 | 264 | [57] |

| Basu, A.K., Bhattacharya, A. Chowdhury, S., Chowdhury, S.P. |

2012 | 250 | [78] |

| Balog, R.S., Shadmand, M.B. | 2014 | 217 | [43] |

| Abapour, S., Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B., Nazari-Heris, M. | 2017 | 212 | [79] |

| First period (2010-2019) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. | System components | Objective of optimization | Technique Used | Study findings | Comments on Algorithms | Year of study | |

| [30] | PV, WT, DG, BT. | Optimizing the size of HMGS components for cost and reliability | MOSaDE | Optimization of PV/WT/DG HMGS in Yanbu, Saudi Arabia, showing application in optimizing the system and practical implications. The study demonstrates the application of the MOSaDE algorithm in optimizing the sizing of hybrid microgrid system components. The results confirm its effectiveness in achieving optimal economic system operation. The paper discusses the impact of design variables on the COE and evaluates the performance of the HERS under different scenarios, indicating the practicality and adaptability of the proposed approach in real-world settings. | The research shows that the MOSaDE algorithm is very effective in improving the HMGS for Yanbu, Saudi Arabia. It demonstrates exceptional abilities in effectively dealing with multiple objectives including as cost, reliability, and integration of RESs. The algorithm's capacity to generate a Pareto front of solutions provides versatility in design options. The adaptability of this technology is shown via its use in improving many components of the HMS, including as PV, WT, and DGs. | 2018 | |

| [80] | PV, CCHP, GSHP, BT | LCOE, Reducing CO2 Emissions, Alleviate disturbances from uncertainties | MOCE | The integrated scheduling approach for MGs addresses uncertainties caused by intermittent RESs and random loads. Load shifting is introduced as an acceptable demand response program for industrial customers. A MOCE minimizes costs and emissions under worst-case scenarios of uncertainties. The robust sets with budgets of uncertainty capture these uncertainties. The strong duality based model transformation method deals with coupling and nonlinearity in the formulation. Comparative experiments confirm the approach's effectiveness in attenuating disturbances and achieving optimal economic and environmental benefits, outperforming single-objective robust optimization and deterministic multi-objective optimization approaches. | The MOCE algorithm is chosen for its high accuracy and directness in solving the proposed formulation. It treats the optimization problem as an estimation problem, using importance sampling techniques to estimate parameters of probability density functions. This approach is effective in multi-objective problems, optimizing all objectives simultaneously and providing a robust solution to the MG scheduling problem under uncertainty. | 2017 | |

| [81] | PV, WT, BT, DG | LCOE, Reducing CO2 Emissions, LPSP | GA | The author employs Pareto front solutions to address a MOO problem, focusing on three critical dimensions: investment costs, emission pollution, and power loss. The optimization process utilizes a GA, adeptly navigating both technical and economic constraints. This methodology proves effective in both grid-connected and standalone HMGs operation modes. Notably, the study excels in balancing the intricate interplay of cost, environmental, and efficiency objectives, presenting a comprehensive and balanced approach to MG planning and resource optimization. | The GA is used for its effectiveness in solving complex optimization problems. It is particularly suitable for problems like DERs planning where technical and economic constraints are involved. GA works well in finding optimal solutions in multi-dimensional objective spaces, as demonstrated by its application to the microgrid in various operation modes. | 2016 | |

| [55] | WT, PV, BT, MT, FC | Minimize cost and emissions with/without responsive loads | MOPSO, Fuzzy-based mechanism, Non-linear sorting system | The study utilized MOPSO, along with a fuzzy-based mechanism and a non-linear sorting system, to optimize microgrid operations, aiming to reduce operating costs and pollutant emissions. It was found that including responsive loads significantly decreased power generation by WT and PV during peak hours, and the implementation of DR programs led to a 24% reduction in operating costs and a 16% decrease in emissions. | MOPSO was effective in balancing the dual objectives of cost reduction and emission control, showing significant improvements in operational efficiency and environmental impact. | 2015 | |

| [82] | WT, PV, BT, DG | LCOE, LPSP, ensuring a system based mainly on RESs. | MOPSO | The study focused on selecting optimal components for a HMGS using MOPSO. It aimed at finding a reliable and cost-effective system configuration. The results indicated that MOPSO effectively provided optimal WT, PV, and BT ratings for the system. | MOPSO was successful in optimizing the system for cost-effectiveness and reliability, demonstrating its utility in managing complex energy systems with a focus on renewable resources. | 2014 | |

| [83] | WT, PV, MT, FC, CHP, electrical and thermal storage | Minimize total operation cost and net emission of a CHP-based MG | MBFO, Interactive Fuzzy Satisfying Method | The study proposed an IEMS for a CHP-based MG, using MBFO and an interactive fuzzy satisfying method to minimize operation cost and emissions. The system smartly covered total electrical and thermal load demands, effectively balancing economic and environmental criteria. | Based on the study outcomes, MBFO, complemented by the fuzzy satisfying method, effectively managed the trade-off between cost and emission, demonstrating its efficiency in optimizing the MG’s performance. | 2013 | |

| [78] | MT, DG, DERs | Optimal economic scheduling of DERs in a CHP-based micro-grid, focusing on multi-objective optimization between fuel cost and emission | PSO, DE | The study aimed at economically deploying DERs in a CHP-based MG, using PSO for optimal sizing and DE for bi-objective optimization between fuel cost and emission. It evaluated different DER mixes, including MTs and DGs, to economically share electrical demand and satisfy various heat demands. The results affirmed the effectiveness of using a mix of DERs for catering to different electrical and heat demands with a balanced compromise between fuel cost and emission. | The results showed that the combination of PSO and DE was effective for bi-objective optimization, demonstrating the ability to balance fuel costs and emissions while ensuring economic and efficient operation of the MG. | 2012 | |

| [58] | PV, WT, BT, FC, MT | Minimize total operating cost and net emission in a renewable MG | AMPSO, CLS, FSA | This study presented an AMPSO algorithm for optimal operation of an MG with RESs and a back-up system comprising a MT, FC, and BT. The goal was to minimize both the operating cost and emissions. It included PV and WT among various DG sources. The AMPSO, enhanced by CLS and FSA, was used to handle the nonlinear MOO problem, focusing on balancing power mismatches and energy storage needs. | Based on the given results, the integration of AMPSO with CLS and FSA provided an effective solution for MOO, showing the capability to balance economic and environmental objectives in the operation of a renewable energy-based MG. | 2011 | |

| [84] | Gas turbine, PV | Minimize emissions (CO2, CO, NOx) and fuel consumption in an MG | MOO (MATLAB function “fgoalattain” | The study focused on a microgrid comprising gas turbines and a PV-based active generator. It implemented multi-objective optimization to minimize emissions from gas turbines and prioritize the use of the non-polluting PV-based active generator. The optimization achieved a 9.17% reduction in equivalent CO2 emissions, with the active generator contributing 11% of the total energy to the system. | In this study, the MOO (MATLAB function “fgoalattain” was effectively balanced environmental goals with energy management, demonstrating efficiency in reducing emissions and fuel consumption while utilizing RESs. | 2010 | |

| Second period (2020-2023) | |||||||

| [85] | PV, WT, Hydraulic Plant, biogas plant | Minimize total annualized cost of electricity supply and minimize energy import from the network | MOPSO | The article presents a novel optimization technique for MG production in a Spanish town with inconsistent grid connections. Employing a MOPSO technique, the primary purpose is to minimize expenses and decrease the reliance onthe grid. The methodology yields a pragmatic and viable resolution, with a 20-year Internal Rate of Return of 8.33%. This is accomplished by using a combination of PV, WT, hydropower, biomass, and turbine-based power production. This approach not only improves the ability to produce enough energy for one's own needs but also establishes a model for the possibility of separating from Spain's national power network. | In this study, the MOPSO algorithm effectively minimized the objective function, balancing the cost and energy imported from the network. The results showed that higher installed power led to less energy imported from the network. | 2023 | |

| [86] | PV, WT, DG, BT, MT, FC | LCOE, LPSP, RF | MOSSA | This study proposes an optimization design for a stand-alone microgrid system in Djelfa, Algeria, aimed at serving a remote off-grid community. The system is powered by hybrid sources (PV, WT, BT, DG) and optimizes the minimum cost of electricity (COE) and minimum potential for electrical loss (LPSP) using the multiobjective salp swarm algorithm (MOSSA). The results show MOSSA’s superiority over algorithms like MODA, MOGOA, and MOALO, achieving better RF, COE, and LPSP. The study emphasizes the use of RESs and proposes future enhancements including diverse renewable sources and advanced AI algorithms. | The use of MOSSA in optimizing a stand-alone microgrid system highlights its efficiency in handling complex energy systems. The focus on renewable energy integration and cost-effective operation demonstrates the potential of advanced algorithms in future microgrid designs, balancing sustainability with practicality. | 2022 | |

| [87] | MT, WT, PV, Bromide Refrigerator, AC, FC, HESS | Minimizing Power Generation and Environmental Treatment Costs | (BAS-ABC) Improved ABC | This study presents an economically optimized multi-objective dispatching model for a CCHP micro-grid, using an improved Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm, enhanced with Beetle Antennae Search Algorithm (BAS-ABC). The model aims to minimize both the daily power generation dispatching cost and environmental pollutant treatment cost. Analysis of a grid-connected CCHP micro-grid in Shanghai during summer demonstrates that the BAS-ABC algorithm achieves faster convergence and lower minimum costs compared to traditional ABC. It also highlights the inherent conflict in optimizing for the lowest power generation cost and environmental cost simultaneously, suggesting a comprehensive balance between economic efficiency and environmental friendliness. | The integration of the BAS-ABC algorithm into the CCHP microgrid model signifies advancement over traditional ABC, especially in terms of convergence speed and cost-efficiency. However, the study also underscores the trade-offs between economic and environmental objectives, a crucial consideration for sustainable energy management. | 2021 | |

| [88] | WT, P2G, SOFC/GT, H2 Storage, Electrolyzer | Minimizing System Cost and Wind Curtailment Rate | MOGA | This research integrates a micro-energy system (MES) with wind power, P2G, H2 storage, and a SOFC/GT hybrid. Employing a MOO approach using a GA, it focuses on minimizing system costs and wind curtailment rate while addressing wind power and load variability. The results showcase a low wind curtailment rate of 0.63%, high renewable energy penetration at 90.1%, and an optimized life cycle cost of £2,468,093. The SOFC/GT system maintains maximum electrical efficiency at 67.1%, adhering to safety constraints, and a power management strategy is developed for efficient operation amidst fluctuating demands. | This study shows how MOGA can effectively balance competing goals such as cost-efficiency and renewable energy integration, ensuring an optimized and sustainable microgrid operation. | 2020 | |

| [89] | PV, WT, BT | Minimizing Annual Comprehensive Cost and Grid Dependency | MOCS, TOPSIS | This study establishes a MOO function for a grid-connected MG, focusing on minimizing the annual comprehensive cost and grid dependency. It utilizes the k-medoids method to handle uncertainties of RESs and load demand. The MOCS algorithm is used to solve the model, and the TOPSIS method is employed to find the optimal compromise solution | The combination of the MOCS algorithm and the TOPSIS method in this study indicates a robust approach to microgrid configuration under uncertain conditions. It highlights the importance of considering multiple objectives and uncertainties in renewable energy systems for achieving both economic and grid reliability targets. | 2020 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).