Submitted:

04 April 2024

Posted:

05 April 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

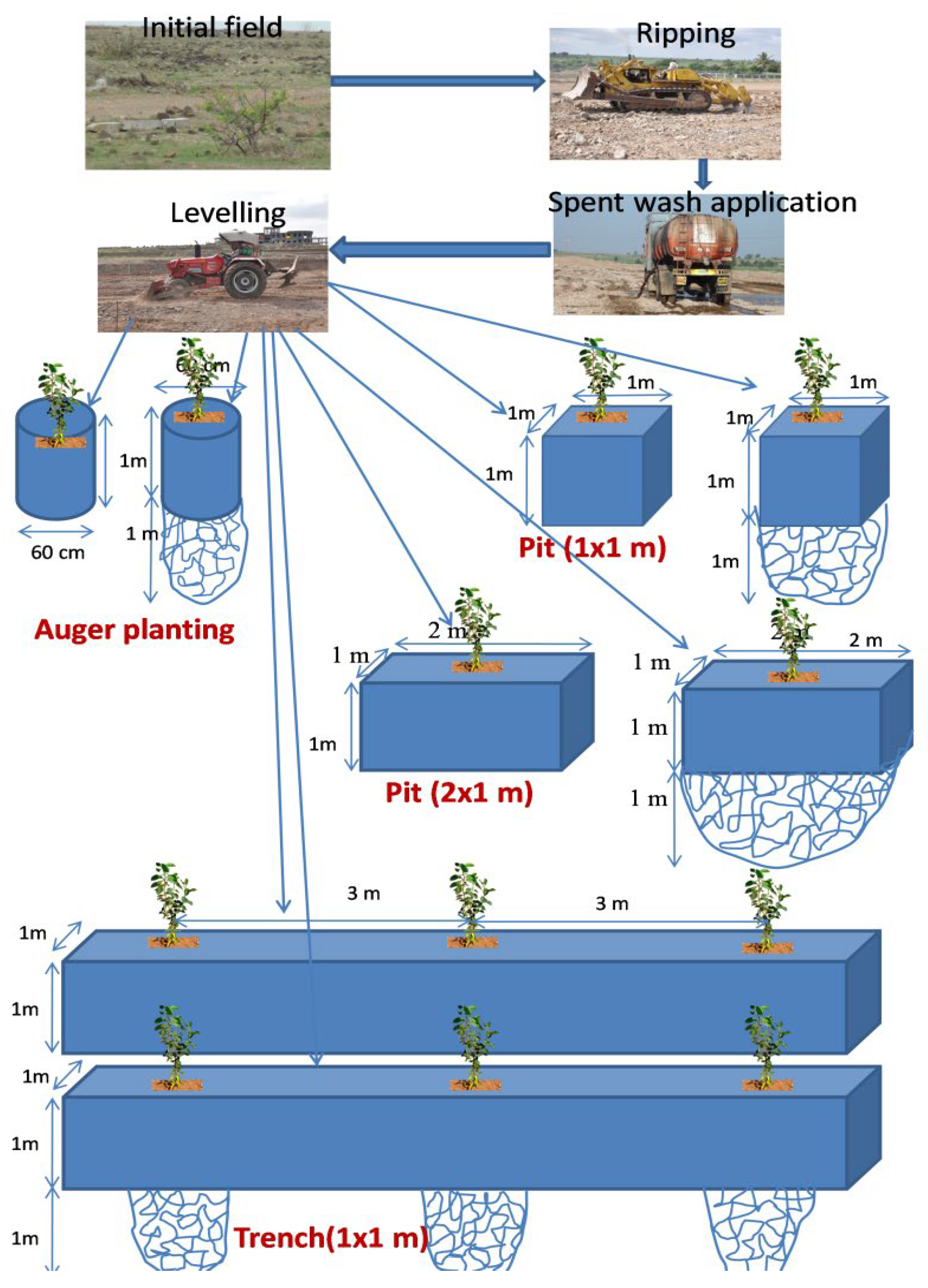

2.2. Establishment of the Pomegranate Orchard

2.3. Planting Techniques

2.4. Crop Husbandry

2.5. Collection, Processing and Analysis of Samples

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Properties of Soil Types Used for Pomegranate Plantings in the Shallow and Gravelly Barren Land

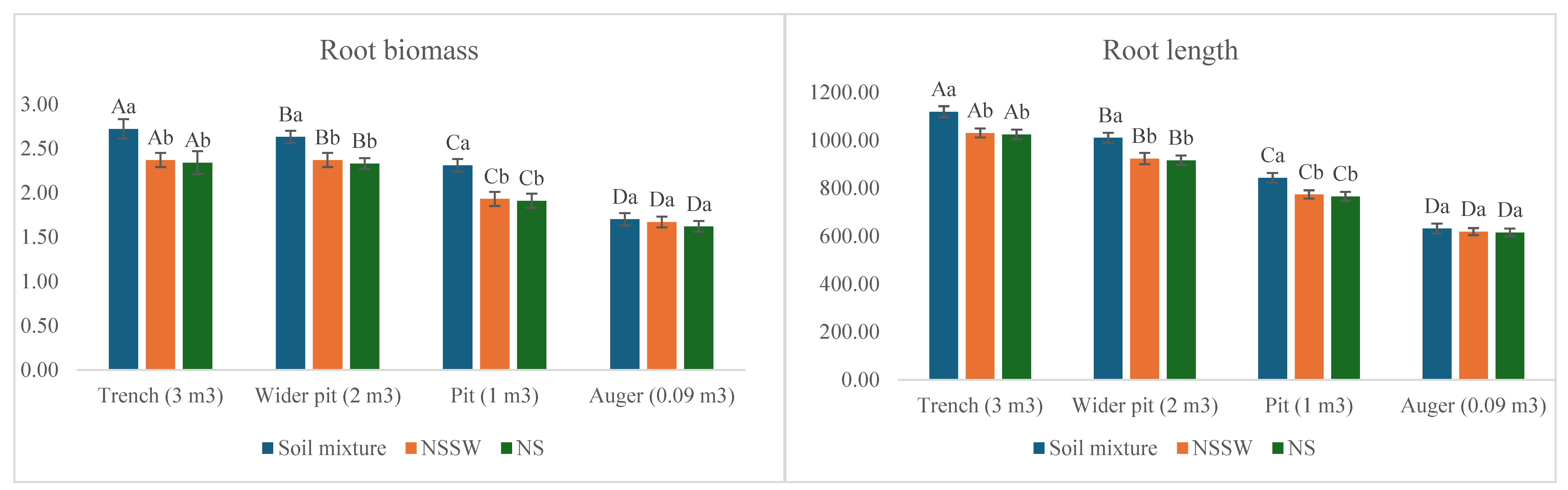

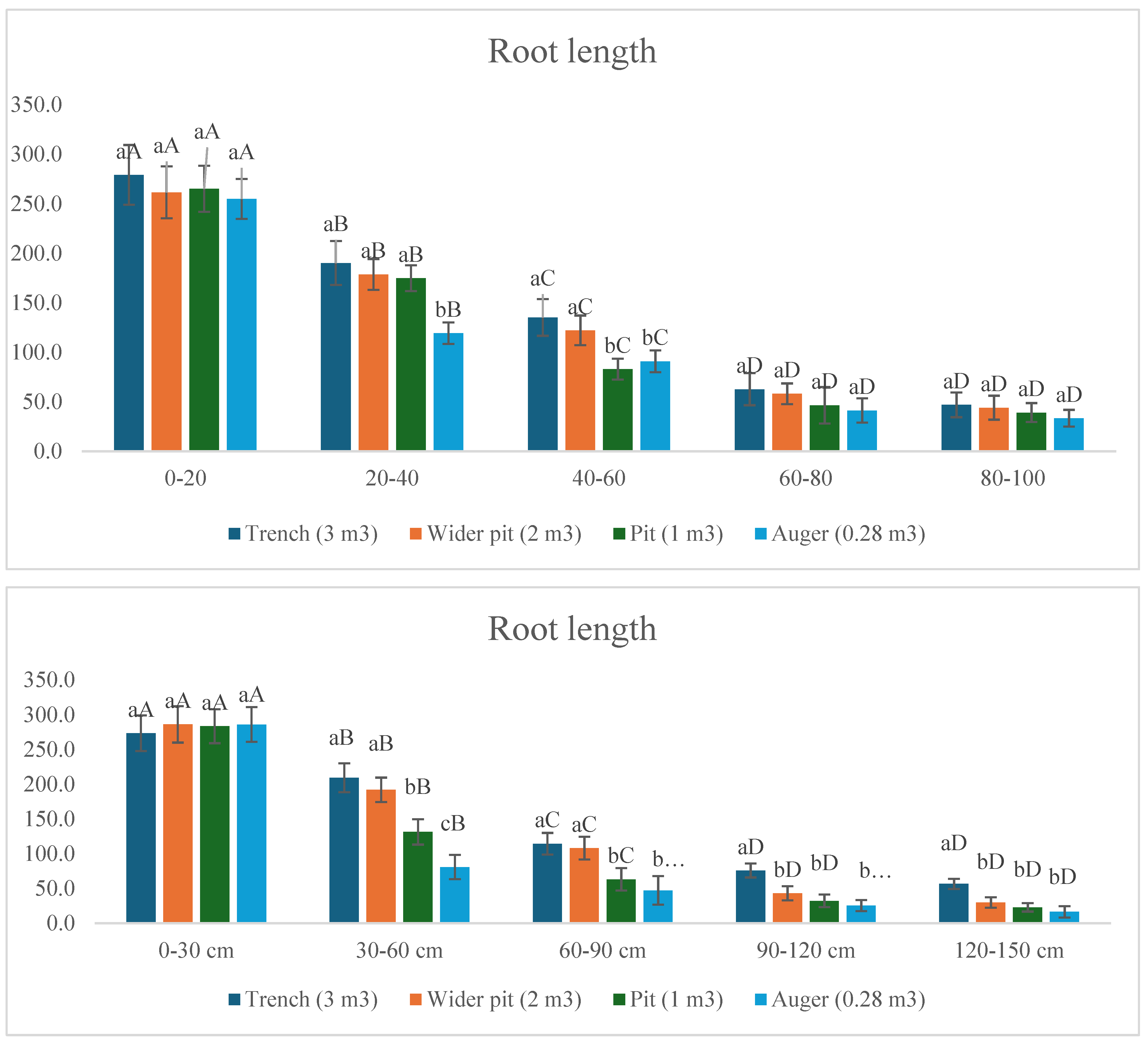

3.2. Effect of Planting Techniques on Growth Parameters of Pomegranate Trees

3.3. Effect of Planting Techniques on Nutrients Content of Leaves of Pomegranate Trees

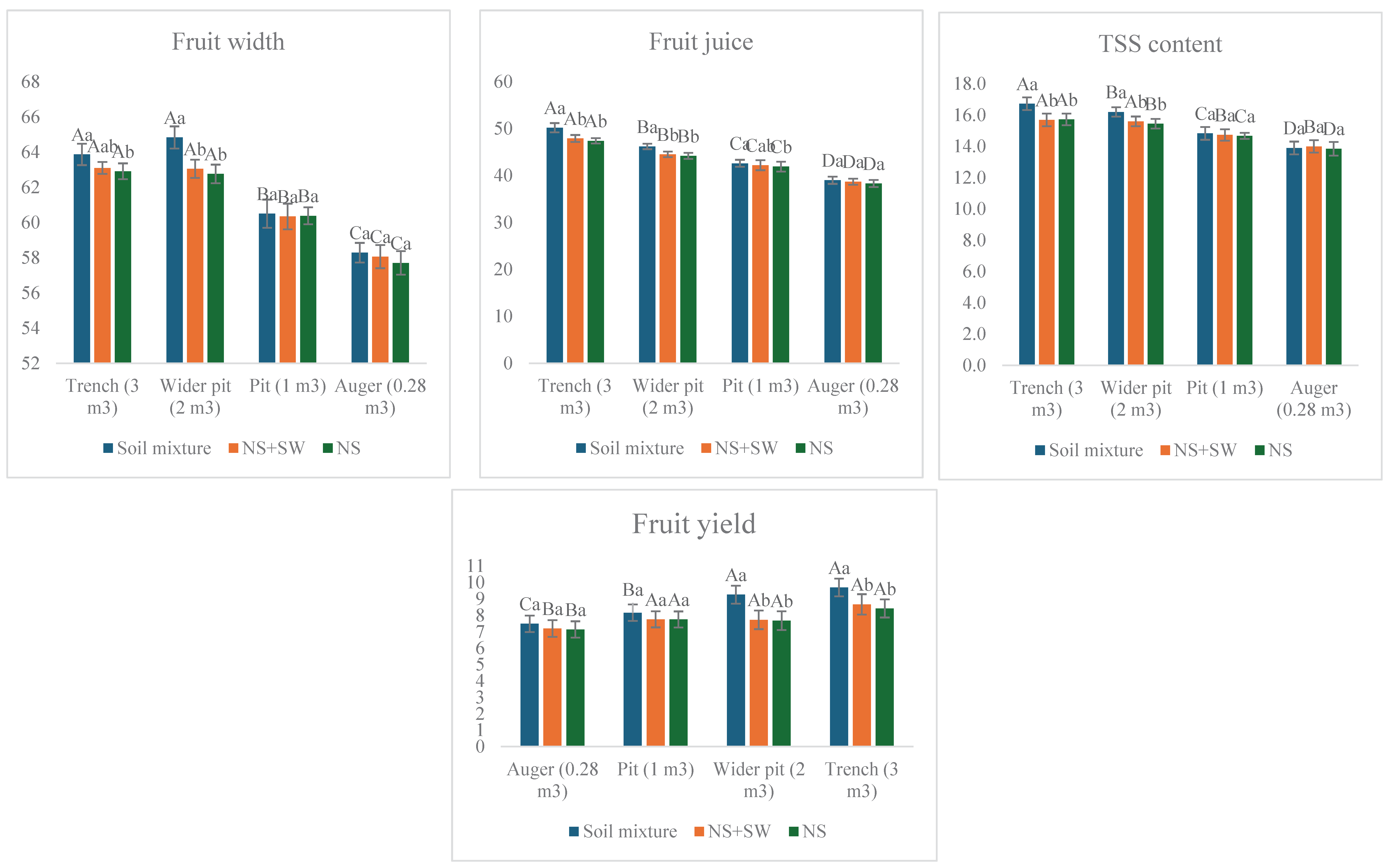

3.4. Effect of Planting Techniques on Fruit Quality Parameters of Pomegranate

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Planting Techniques on Growth and Development of Pomegranate Trees

4.2. Influence of Planting Approaches on Leaf Nutrients Concentrations, Yield, and Fruit Quality

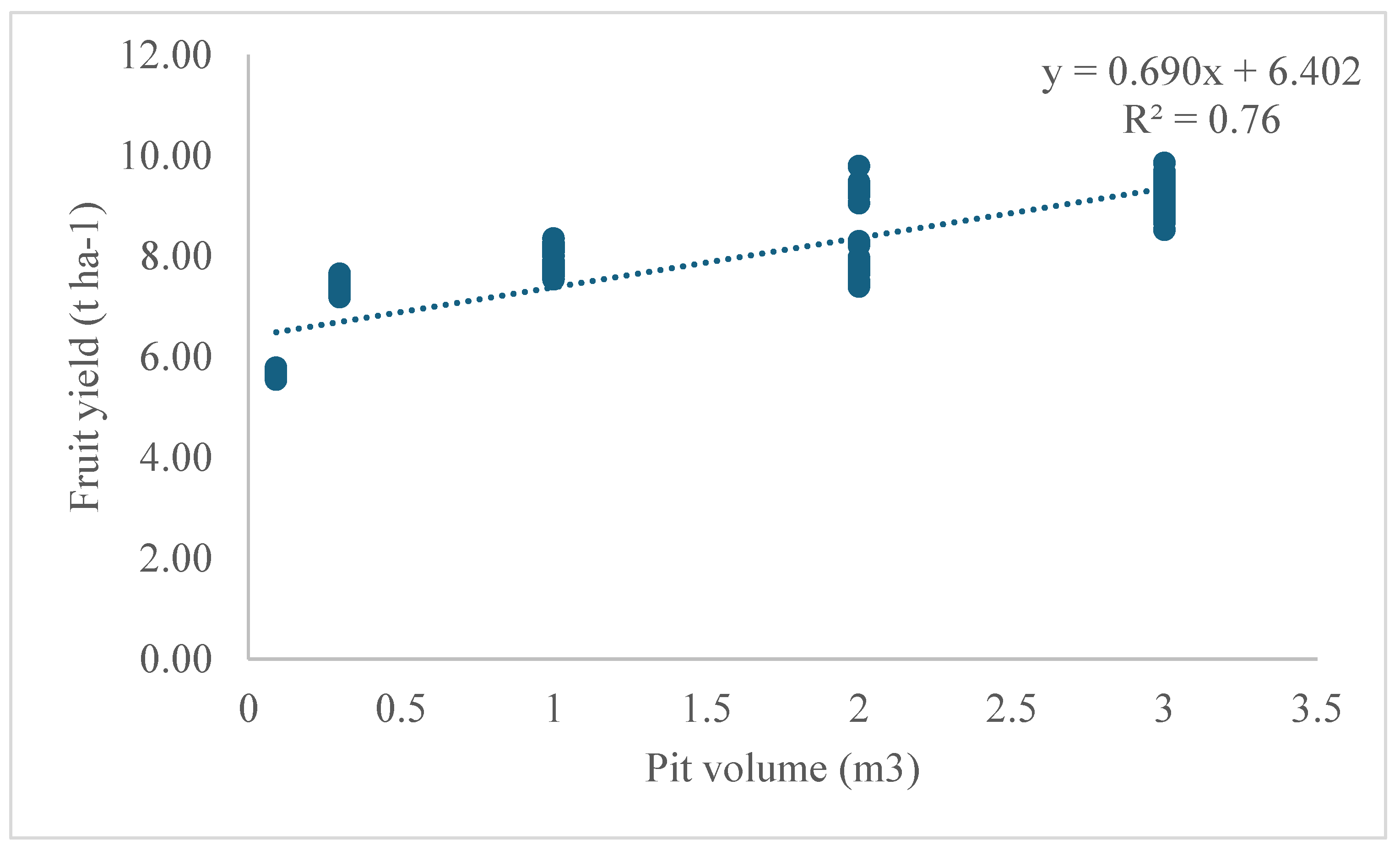

4.3. Impact of Pit Volume and Spent Wash Application on Fruit Production

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saroj PL, Kumar R. Recent advances in pomegranate production in India-a review. Annals of Horticulture. 2019;12. [CrossRef]

- Narayan P, Chand S. Explaining status and scope of pomegranate production in India: An economic analysis. INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS. 2020;11. [CrossRef]

- Marathe RA, Sharma J, Dhinesh Babu K. Identification of suitable soils for cultivation of pomegranate (Punica granatum) cv Ganesh. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2016;86. [CrossRef]

- Loh FCW, Grabosky JC, Bassuk NL. Growth response of Ficus benjamina to limited soil volume and soil dilution in a skeletal soil container study. Urban For Urban Green. 2003;2. [CrossRef]

- Kheoruenromne I, Suddhiprakarn A, Watana S. Properties and Agricultural Potential of Skeletal Soils in Southern Thailand. Kasetsart Journal Natural Sciences. 2000;34.

- Devin SR, Prudencio ÁS, Mahdavi SME, Rubio M, Martínez-García PJ, Martínez-Gómez P. Orchard Management and Incorporation of Biochemical and Molecular Strategies for Improving Drought Tolerance in Fruit Tree Crops. Plants. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fulkey G, Nooman HJ. EFFECTS OF SOIL VOLUME ON ROOT GROWTH AND NUTRIENT UPTAKE. Developemnts in Agricultural and Managed Forest Ecology. 1991;24: 446–448.

- Ojasvi PR, Goyal RK, Gupta JP. The micro-catchment water harvesting technique for the plantation of jujube (Zizyphus mauritiana) in an agroforestry system under arid conditions. Agric Water Manag. 1999;41. [CrossRef]

- Mauki D, Kilonzo M. Planting pit size determines successful tree seedling establishment in arid and semi-arid region of Tanzania. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators. 2022;15. [CrossRef]

- Celma S, Katrina B, Dagnija L, Karlis D, Santa N, Toms A S, et al. Effect of soil preparation method on root development of P. sylvestris and P. abies saplings in commercial forest stands. New For (Dordr). 2019;50: 283–290.

- Von Carlowitz PG, Wolf G V. Open-pit sunken planting: a tree establishment technique for dry environments. Agroforestry Systems. 1991;15. [CrossRef]

- Jo HK, Park HM. Effects of pit plantings on tree growth in semi-arid environments. Forest Sci Technol. 2017;13. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad N, Rajkumar M, Singh K, Nain NPS, Singh S, Rao GR, et al. Spacing, PIT size and irrigation influence early growth performances of forest tree species. Journal of Tropical Forest Science. 2021;33. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso FCG, Marques R, Botosso PC, Marques MCM. Stem growth and phenology of two tropical trees in contrasting soil conditions. Plant Soil. 2012;354. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Huang X, Chen T, Zhou P, Huang X, Jin W, et al. Fruit quality prediction based on soil mineral element content in peach orchard. Food Sci Nutr. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar G, Sharma DD, Kuchay MA, Kumar R, Singh G, Kaushal B. Effect of Foliar Application of Nutrients on Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Cv. Bhagwa. Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Marathe RA, Sharma J, Murkute AA. Innovative soil management for sustainable pomegranate cultivation on skeletal soils. Soil Use Manag. 2018;34. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem Shah M, Wright DL, Hussain S, Koutroubas SD, Seepaul R, George S, et al. Organic fertilizer sources improve the yield and quality attributes of maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids by improving soil properties and nutrient uptake under drought stress. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2023;35. [CrossRef]

- Singh R, Potekar S, Chaudhary A, Das D, Rane J, Pathak H. Climatic Trends in Western Maharashtra, India. Pune; 2020.

- Bouyoucos GJ. Hydrometer Method Improved for Making Particle Size Analyses of Soils 1 . Agron J. 1962;54. [CrossRef]

- Vincent KR, Chadwick OA. Synthesizing Bulk Density for Soils with Abundant Rock Fragments. Soil Science Society of American Journal. 1994;58: 455–464. Available. [CrossRef]

- Reichert JM, Albuquerque JA, Kaiser DR, Reinert DJ, Urach FL, Carlesso R. Estimation of water retention and availability in soils of Rio Grande do Sul. Rev Bras Cienc Solo. 2009;33. [CrossRef]

- Corey RB. A Textbook of Soil Chemical Analysis. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 1973;37. [CrossRef]

- Walkley AJ, Black IA. Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934;37.

- Hussain F, Malik KA. Evaluation of alkaline permanganate method and its modification as an index of soil nitrogen availability. Plant Soil. 1985;84. [CrossRef]

- Olsen SR, Cole CV,, Watanabe FS. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office; 1954.

- Williams CH, Steinbergs A. Soil sulphur fractions as chemical indices of available sulphur in some australian soils. Aust J Agric Res. 1959;10. [CrossRef]

- McHale MR, Burke IC, Lefsky MA, Peper PJ, McPherson EG. Urban forest biomass estimates: Is it important to use allometric relationships developed specifically for urban trees? Urban Ecosyst. 2009;12. [CrossRef]

- Marini RP, Barden JA, Sowers D. Growth and Fruiting Responses of `Redchief Delicious’ Apple Trees to Heading Cuts and Scaffold Limb Removal. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 2019;118. [CrossRef]

- Habib R. Total root length as estimated from small sub-samples. Plant Soil. 1988;108. [CrossRef]

- Pierret A, Moran CJ, Mclachlan CB, Kirby JM. Measurement of root length density in intact samples using X-radiography and image analysis. Image Analysis and Stereology. 2000;19. [CrossRef]

- Tandon HLS. Methods of analysis of soils, plants, waters, fertilisers & organic manures. Methods of analysis of soils, plants, waters, fertilisers & organic manures. 2005.

- Fawole OA, Opara UL. Effects of maturity status on biochemical content, polyphenol composition and antioxidant capacity of pomegranate fruit arils (cv. ’Bhagwa’). South African Journal of Botany. 2013;85. [CrossRef]

- Boland AM, Mitchell PD, Goodwin I, Jerie PH. The effect of soil volume on young peach tree growth and water use. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1994;119. [CrossRef]

- Naseri M, Joshi DC, Iden SC, Durner W. Rock fragments influence the water retention and hydraulic conductivity of soils. Vadose Zone Journal. 2023;22. [CrossRef]

- Ewetola EA, Oyeyiola YB, Owoade FM, Farotimi MF. Influence of soil texture and compost on the early growth and nutrient uptake of Moringa oleifera Lam. Acta Fytotechnica et Zootechnica. 2019;22. [CrossRef]

- Marathe RA, Babu KD, Shinde YR. Soil and leaf nutritional constraints in major pomegranate growing states of India. Agricultural Science Digest - A Research Journal. 2016;35. [CrossRef]

- Doussan C, Pagès L, Pierret A. Soil exploration and resource acquisition by plant roots: An architectural and modelling point of view. Sustainable Agriculture. 2009. [CrossRef]

- . Isaac ME, Borden KA. Nutrient acquisition strategies in agroforestry systems. Plant and Soil. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Proebsting L, Jerie PH, Irvine J. Water Deficits and Rooting Volume Modify Peach Tree Growth and Water Relations. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 2022;114. [CrossRef]

- Loh FCW, Grabosky JC, Bassuk NL. Growth response of Ficus benjamina to limited soil volume and soil dilution in a skeletal soil container study. Urban For Urban Green. 2003;2. [CrossRef]

- Newman EI, Andrews RE. Uptake of phosphorus and potassium in relation to root growth and root density. Plant Soil. 1973;38. [CrossRef]

- Li X, He N, Xu L, Li S, Li M. Spatial variation in leaf potassium concentrations and its role in plant adaptation strategies. Ecol Indic. 2021;130. [CrossRef]

- Quaggio JA, Mattos D, Cantarella H. Fruit yield and quality of sweet oranges affected by nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium fertilization in tropical soils. Fruits. 2006;61. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Shao G, Gao Y, Zhang K, Wei Q, Cheng J. Effects of water deficit combined with soil texture, soil bulk density and tomato variety on tomato fruit quality: A meta-analysis. Agric Water Manag. 2021;243. [CrossRef]

- de Luna Souto AG, de Melo EN, Cavalcante LF, do Nascimento APP, Cavalcante ÍHL, Geovani Soares, et al. Water-Retaining Polymer and Planting Pit Size on Chlorophyll Index, Gas Exchange and Yield of Sour Passion Fruit with Deficit Irrigation. Plants. 2024;13: 235.

- Rajagopal V, Paramjit SM, Suresh KP, Yogeswar S, Nageshwar RDVK, Avinash N. Significance of vinasses waste management in agriculture and environmental quality- Review. Afr J Agric Res. 2014;9. [CrossRef]

- Hassan MU, Aamer M, Chattha MU, Haiying T, Khan I, Seleiman MF, et al. Sugarcane distillery spent wash (Dsw) as a bio-nutrient supplement: A win-win option for sustainable crop production. Agronomy. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hiwale SS, More TA, Bagle BG. Root distribution pattern in pomegranate “Ganesh” (Punica granatum L.). Acta Hortic. 2011;890.

| Treat No | Pits | Soil Types | CF (%) | Sand (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) | SSV (m3 Mg-1) | PAW (%) | pH (1:2) | EC (1:2)(dS m-1) | OC (%) | N (kg ha-1) | P (kg ha-1) | K (kg ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Trench | NSBS | 15.6 | 42.5 | 25.2 | 32.3 | 0.73 | 17.5 | 7.4 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 154.5 | 8.5 | 225.2 |

| T2 | Trench | NSSW | 20.5 | 62.5 | 19.6 | 17.9 | 0.63 | 11.5 | 4.6 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 135.5 | 3.8 | 223.2 |

| T3 | Trench | NS | 21.2 | 64.1 | 19.2 | 16.7 | 0.65 | 12.3 | 6.7 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 132.5 | 3.5 | 216.2 |

| T4 | Trench with ED | NSBS | 15.2 | 38.3 | 26.5 | 35.2 | 0.68 | 18.2 | 7.2 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 156.0 | 8.2 | 220.5 |

| T5 | Trench with ED | NSSW | 19.8 | 70.6 | 15.1 | 14.3 | 0.65 | 12.6 | 4.7 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 137.5 | 4.0 | 217.3 |

| T6 | Trench with ED | NS | 20.2 | 71.2 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 0.64 | 11.8 | 6.6 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 135.2 | 3.7 | 218.5 |

| T7 | Wider pit | NSBS | 15.1 | 40.6 | 26.0 | 33.4 | 0.69 | 17.5 | 7.3 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 158.0 | 8.0 | 219.3 |

| T8 | Wider pit | NSSW | 21.8 | 63.1 | 19.0 | 17.9 | 0.66 | 12.5 | 5.2 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 132.5 | 4.1 | 217.6 |

| T9 | Wider pit | NS | 20.8 | 63.8 | 17.8 | 18.4 | 0.65 | 11.8 | 6.7 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 134.1 | 3.9 | 217.2 |

| T10 | Wider Pit with ED | NSBS | 21.2 | 38.5 | 25.5 | 36.0 | 0.70 | 17.3 | 7.5 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 155.0 | 8.3 | 223.2 |

| T11 | Wider Pit with ED | NSSW | 20.5 | 65.2 | 18.5 | 16.3 | 0.65 | 11.8 | 4.7 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 136.2 | 4.2 | 220.2 |

| T12 | Wider Pit with ED | NS | 21 | 66.0 | 17.2 | 16.8 | 0.64 | 12.4 | 6.9 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 135.4 | 3.8 | 218.2 |

| T13 | Pit | NSBS | 14.8 | 34.2 | 30.2 | 35.6 | 0.71 | 18.5 | 7.5 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 153.0 | 8.1 | 223.5 |

| T14 | Pit | NSSW | 21.3 | 64.0 | 18.2 | 17.8 | 0.64 | 11.5 | 4.8 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 134.5 | 4.3 | 223.2 |

| 15 | Pit | NS | 20.7 | 70.2 | 14.5 | 15.3 | 0.66 | 12.6 | 7.0 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 133.5 | 3.7 | 221.5 |

| T16 | Pit with ED | NSBS | 15.9 | 39.2 | 25.8 | 34.7 | 0.69 | 18.2 | 7.3 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 155.0 | 8.4 | 220.5 |

| T17 | Pit with ED | NSSW | 20.2 | 65.0 | 18.6 | 16.4 | 0.65 | 12.3 | 4.3 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 136.5 | 4.0 | 215.6 |

| T18 | Pit with ED | NS | 20.8 | 65.4 | 18.8 | 15.8 | 0.64 | 11.7 | 6.9 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 132.5 | 3.6 | 214.5 |

| T19 | Auger | NSBS | 16.3 | 37.2 | 26.0 | 36.8 | 0.70 | 17.8 | 7.4 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 157.0 | 8.3 | 221.5 |

| T20 | Auger | NSSW | 19.8 | 64.5 | 19.5 | 16.0 | 0.63 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 135.2 | 4.1 | 219.2 |

| T21 | Auger | NS | 21.2 | 65.0 | 19.1 | 15.9 | 0.64 | 12.2 | 6.9 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 132.2 | 3.9 | 218.6 |

| T22 | Auger with ED | NSBS | 15.5 | 40.0 | 25.7 | 34.3 | 0.67 | 17.6 | 7.7 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 156.0 | 8.6 | 223.5 |

| T23 | Auger with ED | NSSW | 20.5 | 66.2 | 17.8 | 16.0 | 0.63 | 12.0 | 3.8 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 137.5 | 3.5 | 220.1 |

| T24 | Auger with ED | NS | 21 | 65.1 | 18.5 | 15.4 | 0.65 | 11.8 | 6.9 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 134.6 | 3.7 | 219.6 |

| T25 | Farmer Practice I | NLSW | 72.5 | 75.2 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 0.63 | 11.0 | 7.5 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 131.0 | 3.3 | 192.5 |

| T26 | Farmer Practice II | NL | 74.3 | 76.3 | 13.8 | 9.9 | 0.65 | 10.9 | 7.7 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 130.0 | 3.1 | 193.6 |

| Source | Pits | Soil | Depth | Pits X Soil | Pits X Depth | Soil X Depth | Pits X Soil X Depth | Adj R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGB (t ha-1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.58 | 0.83 |

| Crown spread (m2) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.77 |

| Root biomass (t tree-1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.000 | 0.41 | 0.98 | 0.30 | 0.76 |

| Root length (m) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.000 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.00 | 0.83 |

| RLD (m3 m-3) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.650 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.74 |

| Nitrogen (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.360 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 1.00 | 0.84 |

| Phosphorous (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.68 | 0.680 | 0.97 | 0.19 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

| Potassium (%) | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.67 | 0.741 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.90 |

| Fruit yield (t ha-1) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.080 | 0.000 | 0.552 | 0.311 | 0.922 | 0.82 |

| Fruit length (mm) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.810 | 0.920 | 1.000 | 0.550 | 0.920 | 0.95 |

| Fruit width (mm) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.038 | 0.800 | 0.933 | 0.924 | 0.84 |

| Juice content (%) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.200 | 0.000 | 0.129 | 0.411 | 0.662 | 0.96 |

| Total soluble solids (o) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.452 | 0.000 | 0.633 | 0.345 | 0.281 | 0.86 |

| Treatments | Growth parameters | Nutrients content of leaf | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGB (t tree-1) | Crown spread (m2) | Root biomass (t tree-1) | Root length (m) | RLD (m m-3) | N (%) | P (%) | K (%) | |

| Pits | ||||||||

| 1.Trench | 7.06±0.28a | 3.31±0.47a | 2.48±0.24a | 1057.7±48.2a | 0.28±0.08a | 1.58±0.07a | 0.28±0.05a | 1.78±0.08a |

| 2.Wider pit | 7.03±0.31a | 3.30±0.40a | 2.44±0.15a | 949.9±47.9b | 0.28±0.09a | 1.56±0.06a | 0.22±0.04b | 1.55±0.07b |

| 3.Pit | 6.57±0.26b | 2.27±0.33b | 2.05±0.20b | 793.2±39.3c | 0.44±0.07b | 1.39±0.06b | 0.16±0.03c | 1.30±0.06c |

| 4. Auger | 6.21±0.25c | 2.19±0.29b | 1.66±0.10c | 620.7±20.5d | 0.57±0.05c | 1.24±0.05c | 0.12±0.03d | 1.29±0.06d |

| Soil types | ||||||||

| 1.Soil mixture | 7.03±0.48a | 2.91±0.67a | 2.36±0.45a | 898.9±185.9a | 0.36±0.15a | 1.48±0.17a | 0.21±0.08a | 1.49±0.23a |

| 2.Native soil saturated with liquid vinasse | 6.69±0.47b | 2.71±0.64b | 2.10±0.31b | 834.6±157.3b | 0.41±0.13b | 1.43±0.16b | 0.19±0.06b | 1.47±0.20a |

| 3.Native soil | 6.60±0.43c | 2.69±0.62b | 2.05±0.32b | 828.2±156.1b | 0.41±0.14b | 1.44±0.15b | 0.19±0.05b | 1.48±0.19a |

| Farmers method-I | 3.80±0.20 | 1.50±0.21 | 1.40±0.20 | 590.5±30.6 | 0.70±0.07 | 1.16±0.10 | 0.18±0.03 | 1.20±0.07 |

| Farmers method-II | 3.75±0.23 | 1.70±0.23 | 1.30±0.23 | 585.5±41.4 | 0.72±0.06 | 1.15±0.09 | 0.17±0.03 | 1.23±0.09 |

| Treatments | Yield (t ha-1) | Fruit length (mm) | Fruit width (mm) | Fruit Juice content (%) | TSS (° Brix) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pits | |||||

| 1.Trench | 9.16±0.30a | 65.0±0.97a | 63.52±1.21a | 48.5±1.46a | 16.05±0.62a |

| 2.Wider pit | 8.31±0.46b | 64.9±1.04a | 63.39±1.35a | 45.0±1.07b | 15.70±0.45b |

| 3.Pit | 7.88±0.22c | 59.6±0.91b | 60.41±0.77b | 42.2±0.75c | 14.70±0.33c |

| 4. Auger | 7.40±0.12d | 56.0±0.70b | 50.01±0.75b | 38.7±0.76d | 13.90±0.41d |

| Soil types | |||||

| 1.Soil mixture | 8.62±0.85a | 61.7±3.90a | 61.76±2.71a | 44.5±4.25a | 15.4±1.18a |

| 2.Native soil saturated with liquid vinasse | 8.01±0.65b | 61.3±3.94b | 61.26±2.43b | 43.3±3.42b | 15.0±0.78b |

| 3.Native soil | 7.94±0.60c | 61.1±3.93b | 60.98±2.36b | 42.9±3.43c | 14.9±0.81b |

| *Farmers method-I | 5.70±0.27 | 53.5±0.62 | 54.2±1.05 | 35.0±1.1 | 12.9±0.20 |

| *Farmers method-II | 5.65±0.32 | 53.8±0.70 | 53.7±1.02 | 34.4±1.0 | 12.7±0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).