Submitted:

03 April 2024

Posted:

04 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

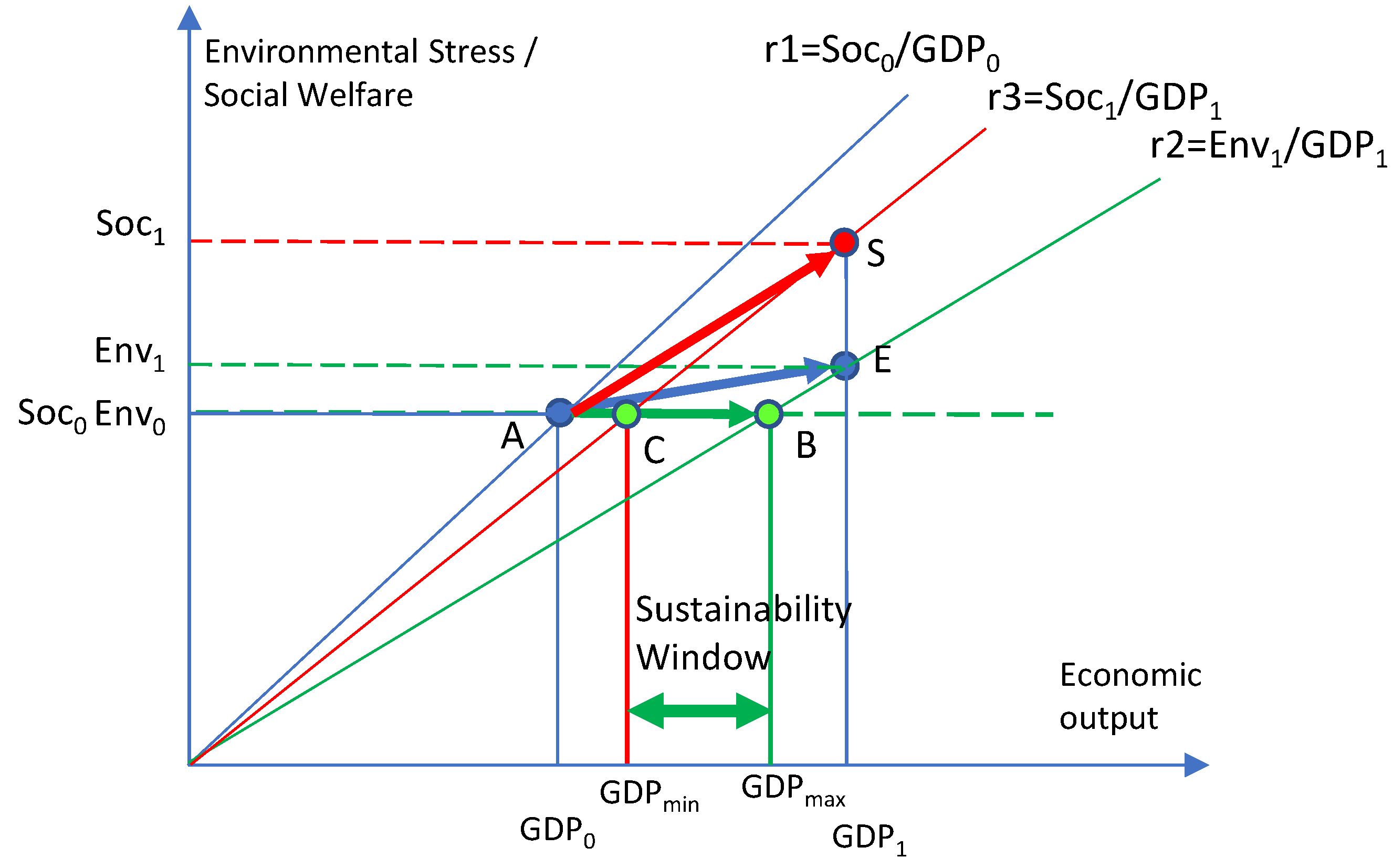

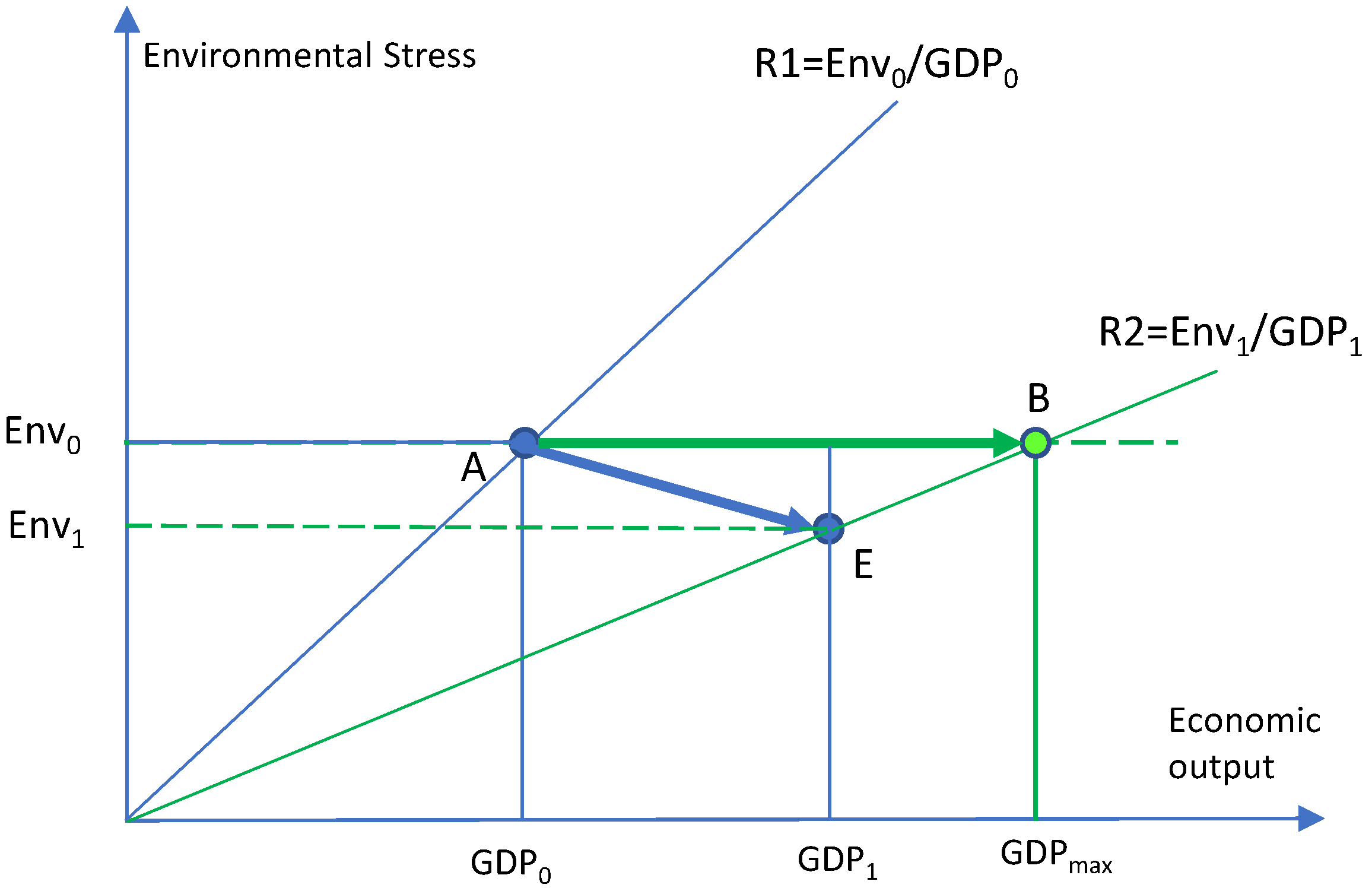

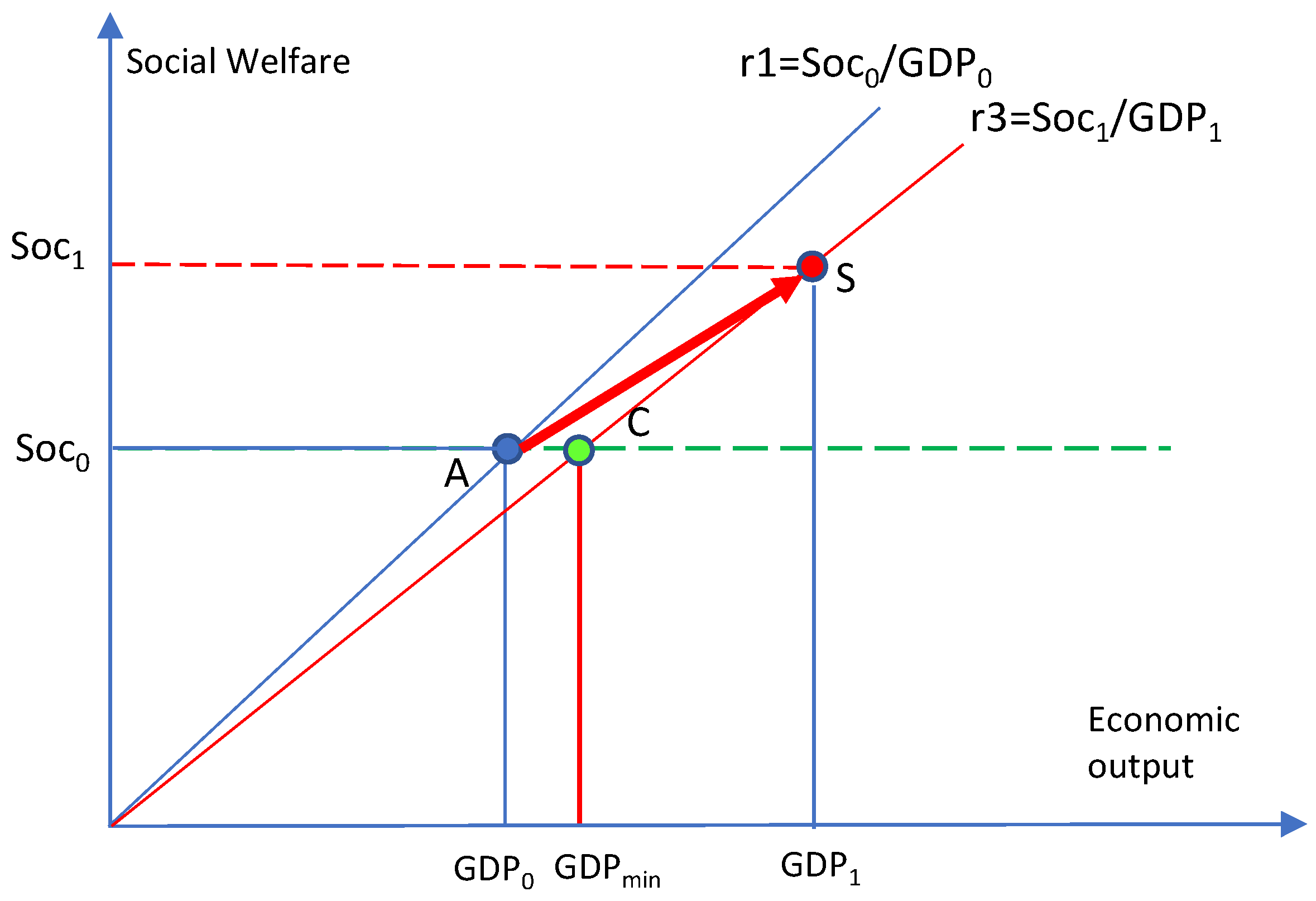

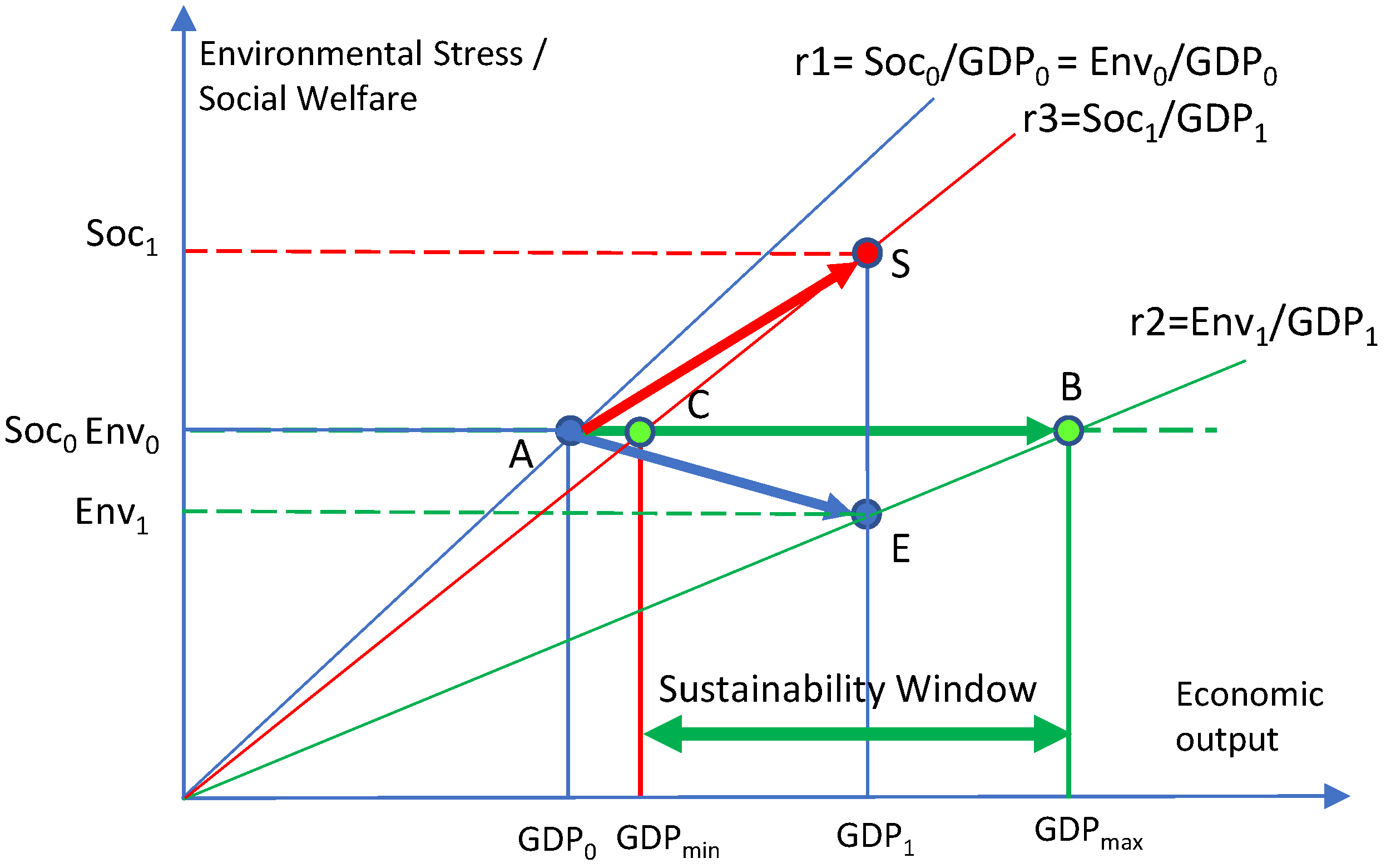

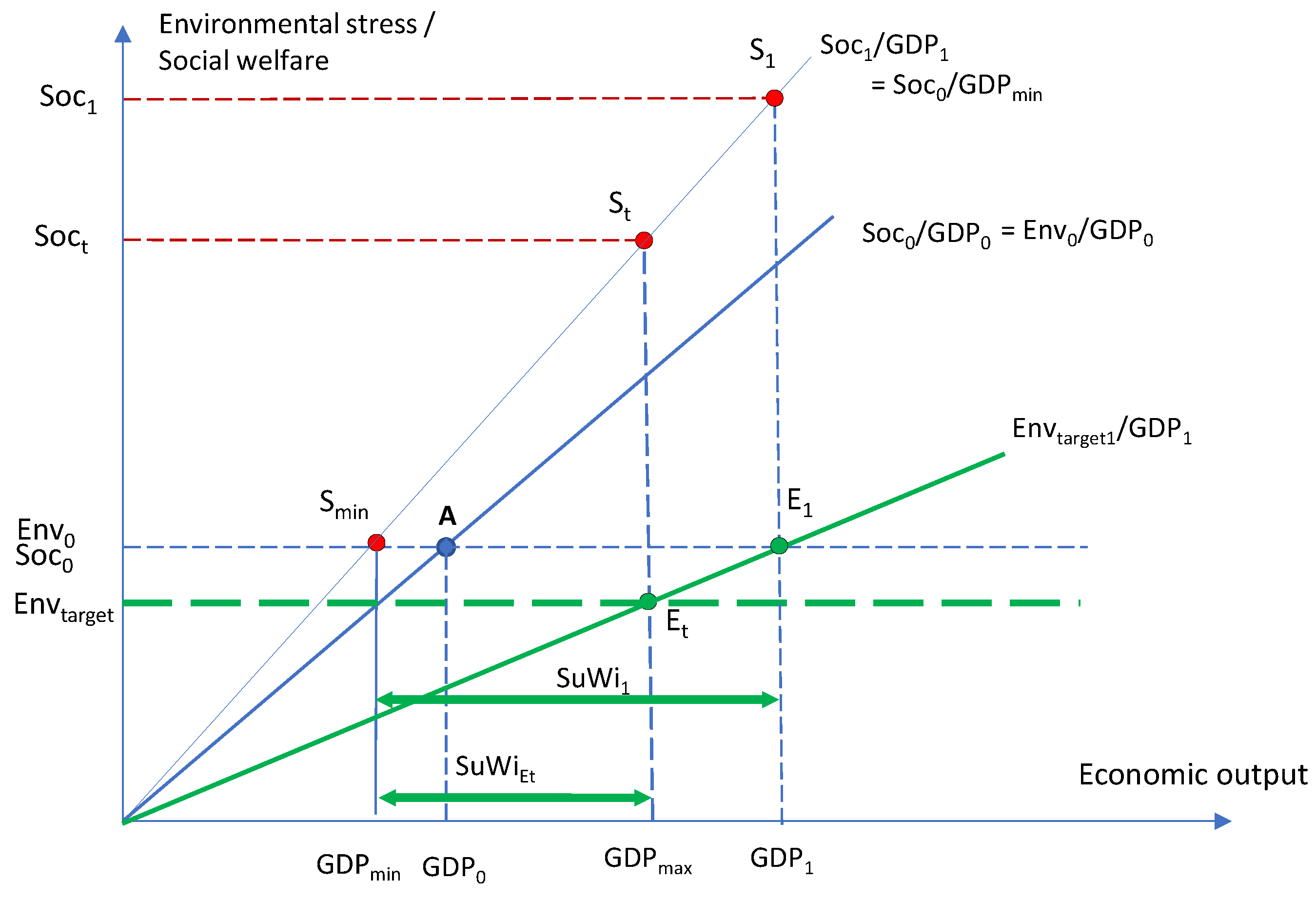

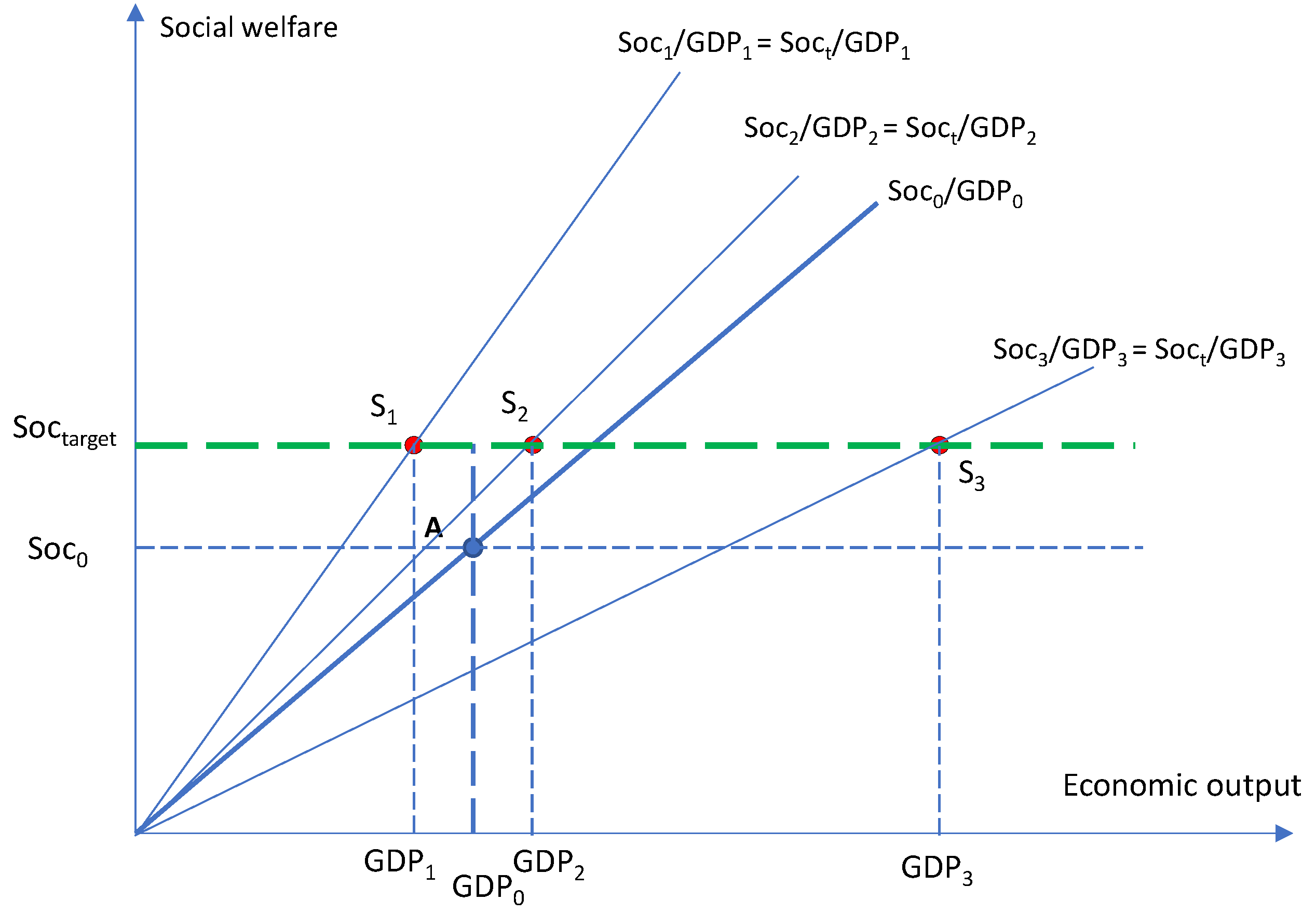

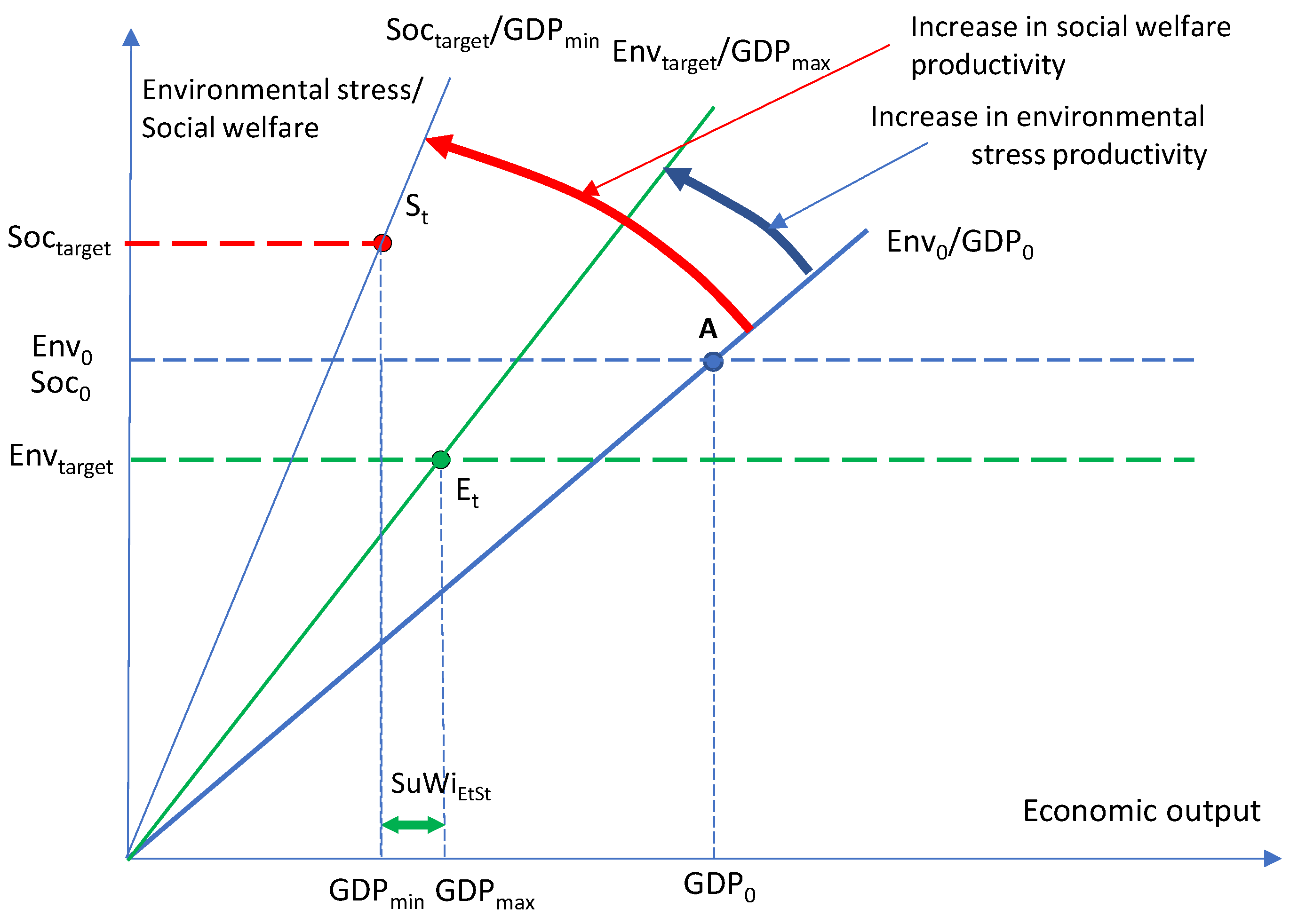

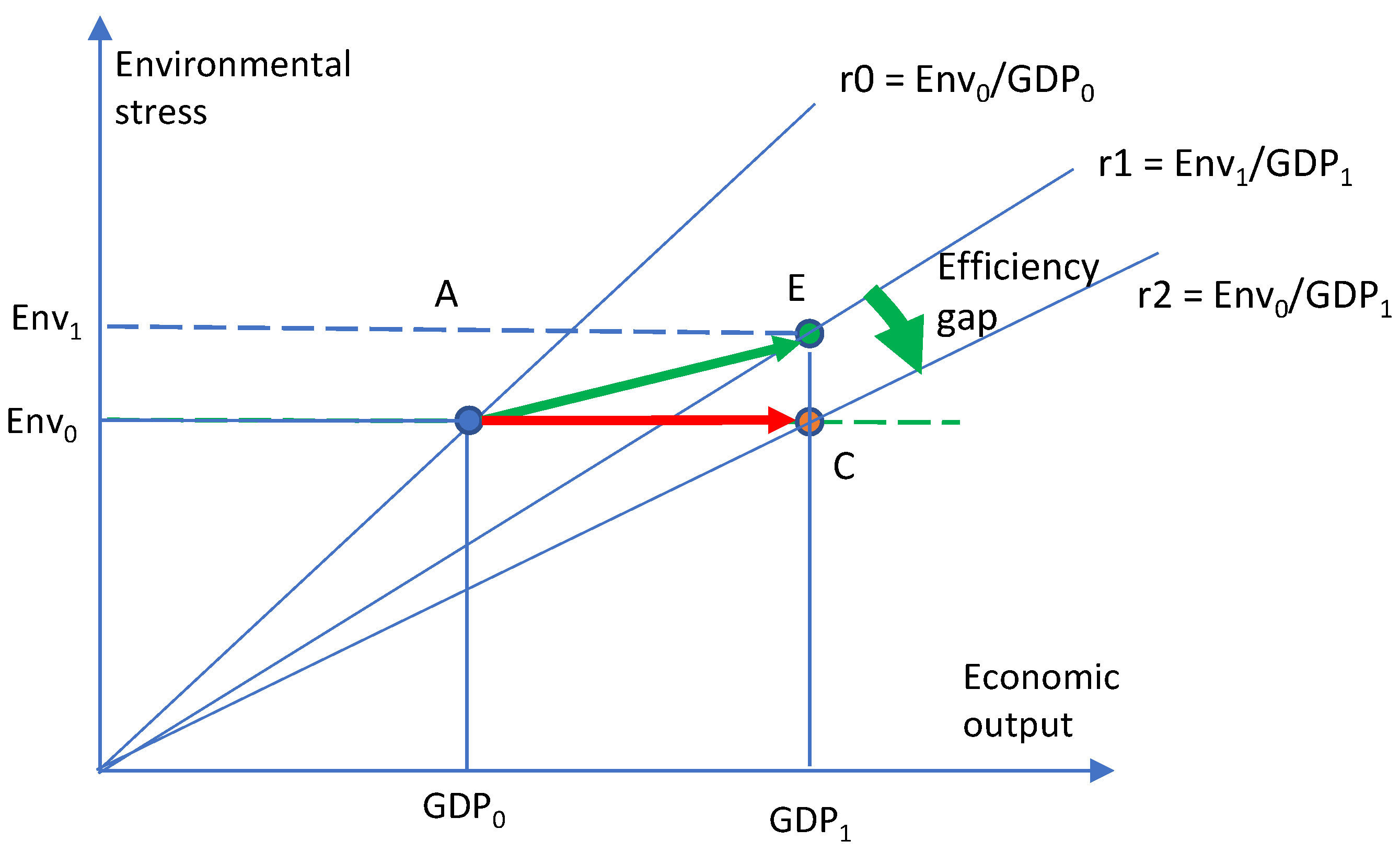

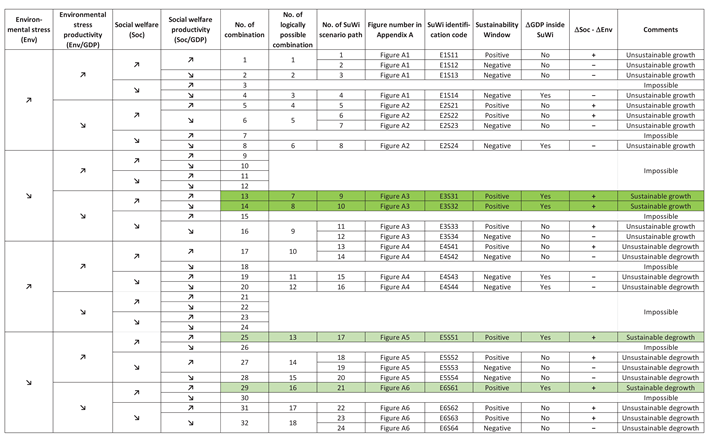

3.1. Possible Economic Growth Paths and Related Sustainability Outcomes

3.2. Analysis of Sustainability Windows with Absolute Targets

4. Discussion

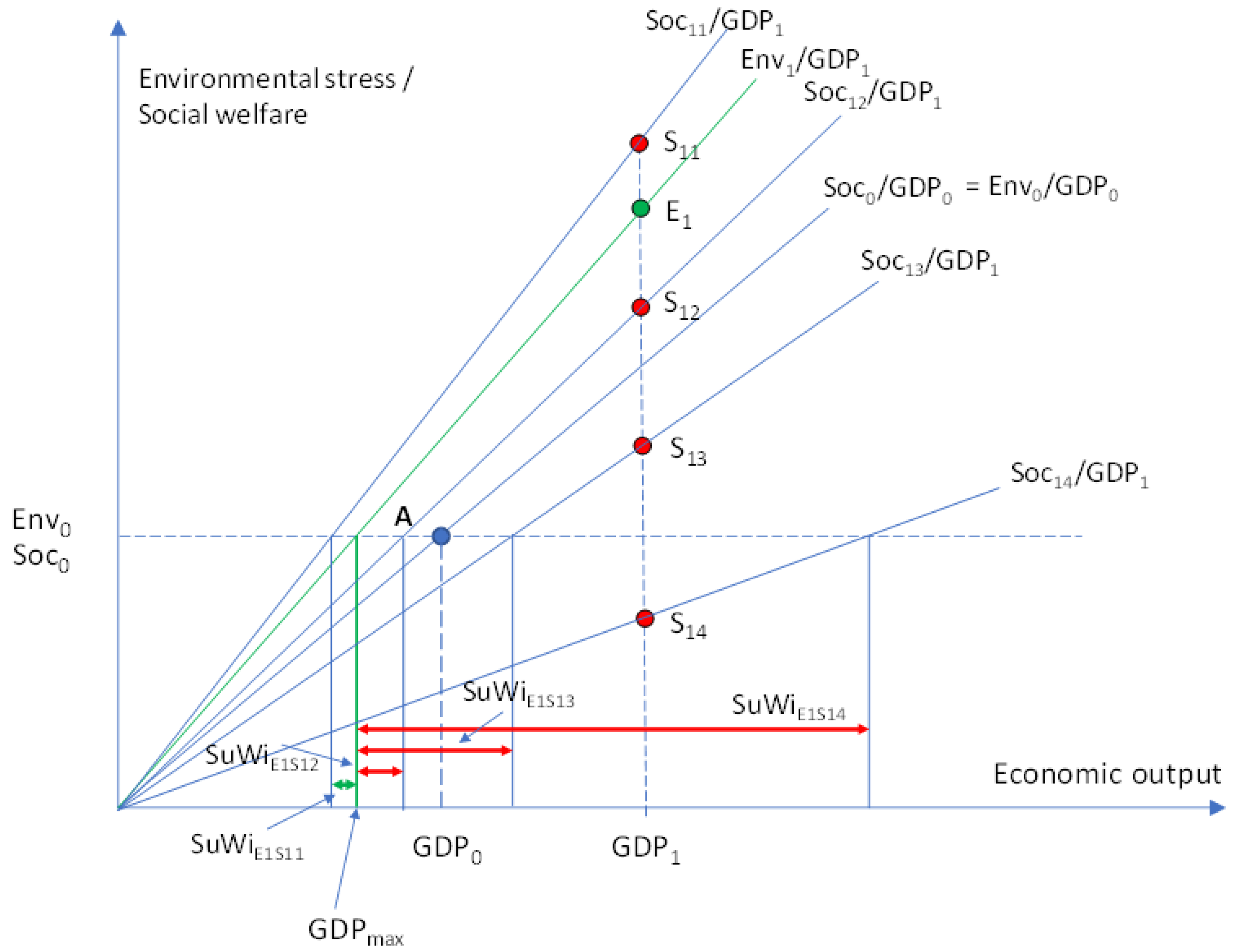

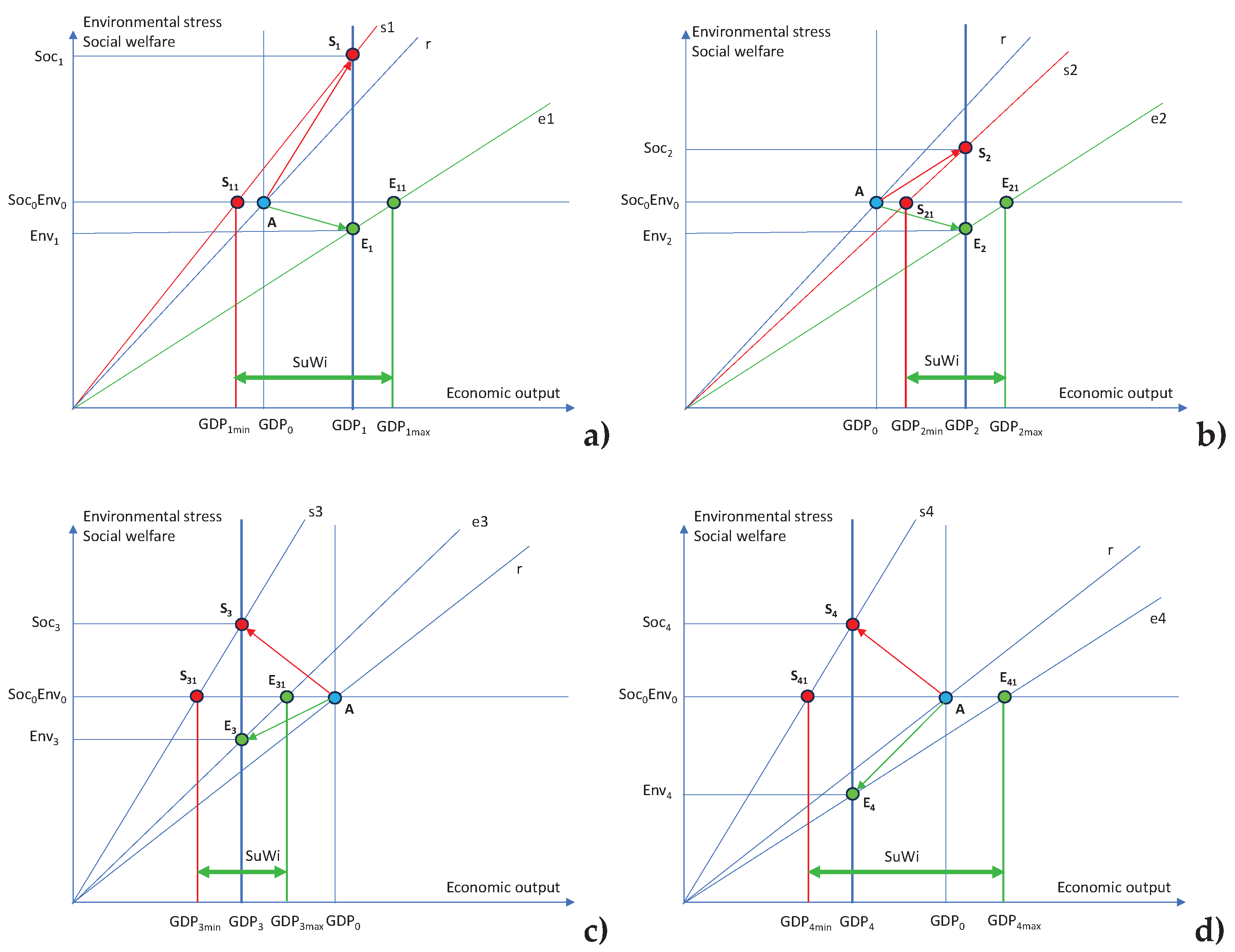

Group 1 (Figure A1).

-

Soc11 > Soc0 and Soc11 > Env1 and Soc11/GDP1 > Env1/GDP1 and Soc11/GDP1 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE1S11) is positive but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP1 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc12 > Soc0 and Soc12 < Env1 and Soc12/GDP1 < Env1/GDP1, and Soc12/GDP1 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE1S12) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP1 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc13 > Soc0 and Soc13 < Env1 and Soc13/GDP1 < Env1/GDP1, and Soc13/GDP1 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE1S13) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP1 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc14 < Soc0 and Soc14 < Env1 and Soc14/GDP1 < Env1/GDP1, and Soc14/GDP1 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE1S14) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) even though the actual GDP growth is inside the negative SuWi (GDPmax < GDP1 < GDPmin), This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

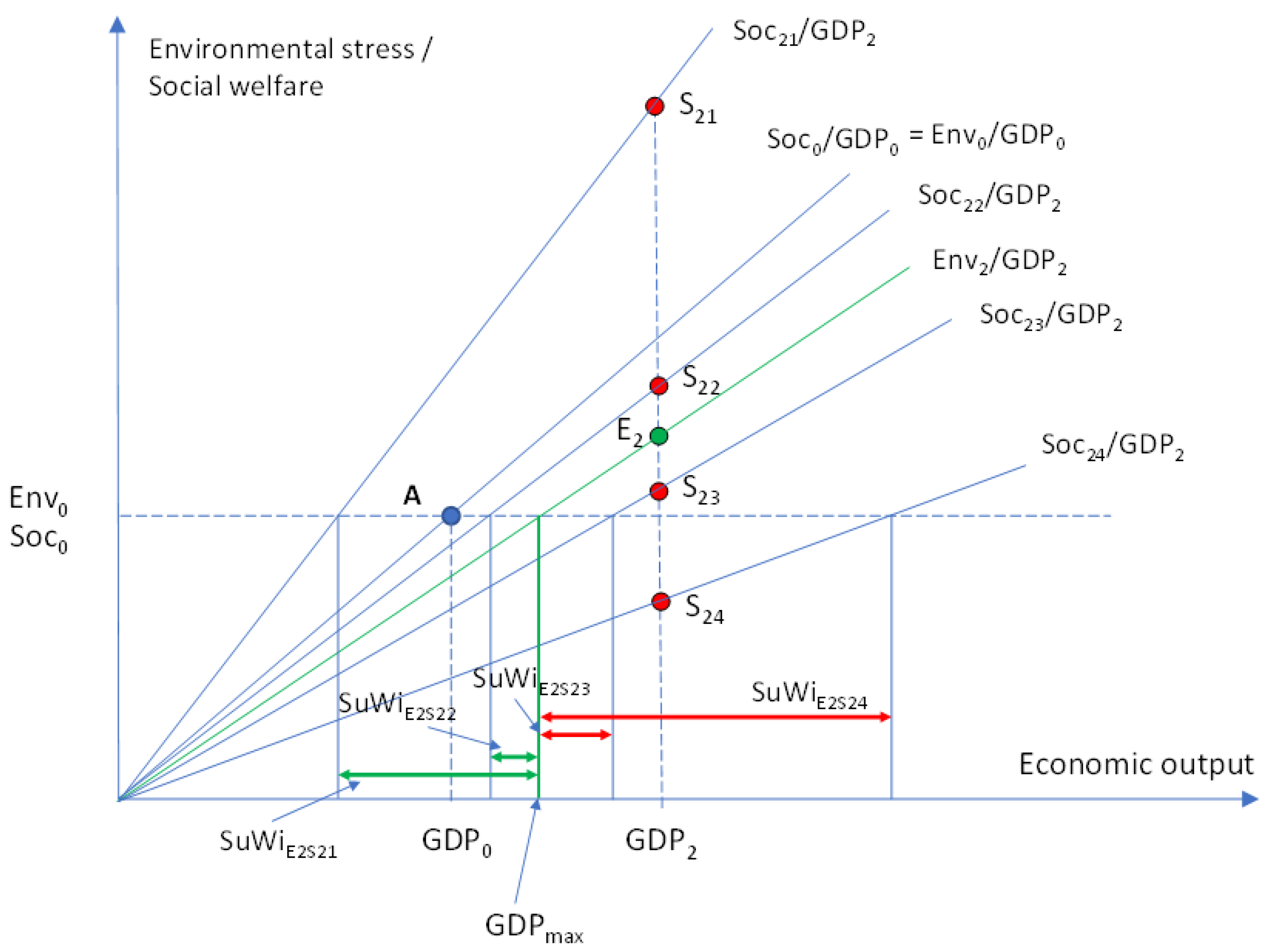

Group 2 (Figure A2).

-

Soc21 > Soc0 and Soc21 > Env2 and Soc21/GDP2 > Env2/GDP1 and Soc21/GDP2 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE2S21) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP2 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc22 > Soc0 and Soc22 > Env2 and Soc22/GDP2 > Env2/GDP2, and Soc22/GDP2 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE2S22) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP2 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc23 < Soc0 and Soc23 < Env2 and Soc23/GDP2 < Env2/GDP2, and Soc23/GDP2 < Soc0/GDP0In this case Sustainability Window (SuWiE2S23) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP2 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc24 < Soc0 and Soc24 < Env2 and Soc24/GDP2 < Env2/GDP2, and Soc24/GDP2 < Soc0/GDP0In this case Sustainability Window (SuWiE2S24) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) even though the actual GDP growth is inside the negative SuWi (GDPmax < GDP2 < GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

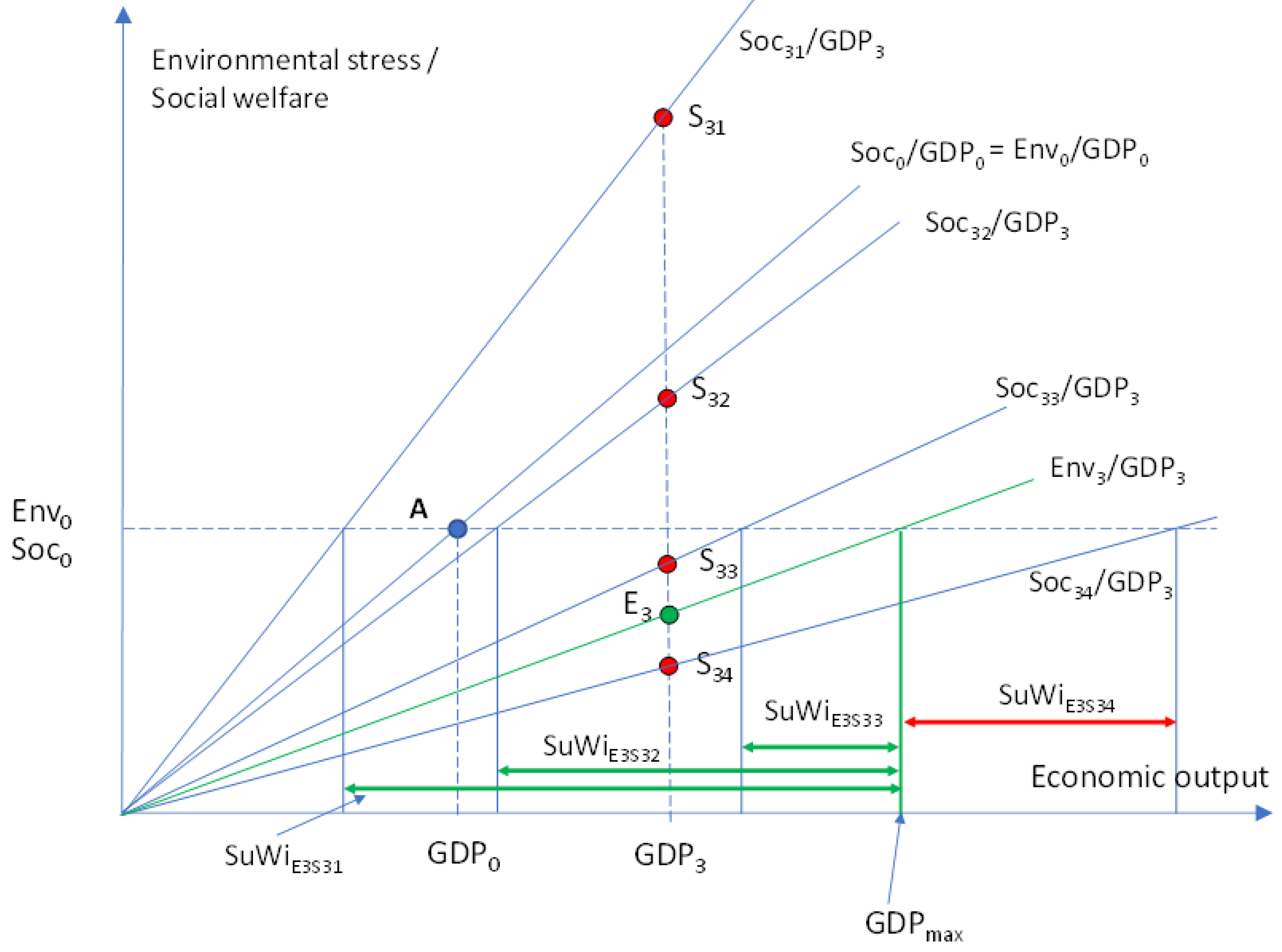

Group 3 (Figure A3).

-

Soc31 > Soc0 and Soc31 > Env3 and Soc31/GDP3 > Env3/GDP3 and Soc31/GDP3 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE3S31) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is inside SuWi (GDPmin < GDP3 < GDPmax). This case fulfills the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc32 > Soc0 and Soc32 > Env3 and Soc32/GDP3 > Env3/GDP3, and Soc32/GDP3 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE3S32) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is inside SuWi (GDPmin < GDP3 < GDPmax). This case fulfills the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc33 < Soc0 and Soc33 > Env3 and Soc33/GDP3 > Env3/GDP3, and Soc33/GDP3 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE3S33) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP3 > GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc34 < Soc0 and Soc34 < Env3 and Soc34/GDP3 < Env3/GDP3, and Soc34/GDP3 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE3S24) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside the negative SuWi (GDP3 < GDPmax < GDPmin), This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

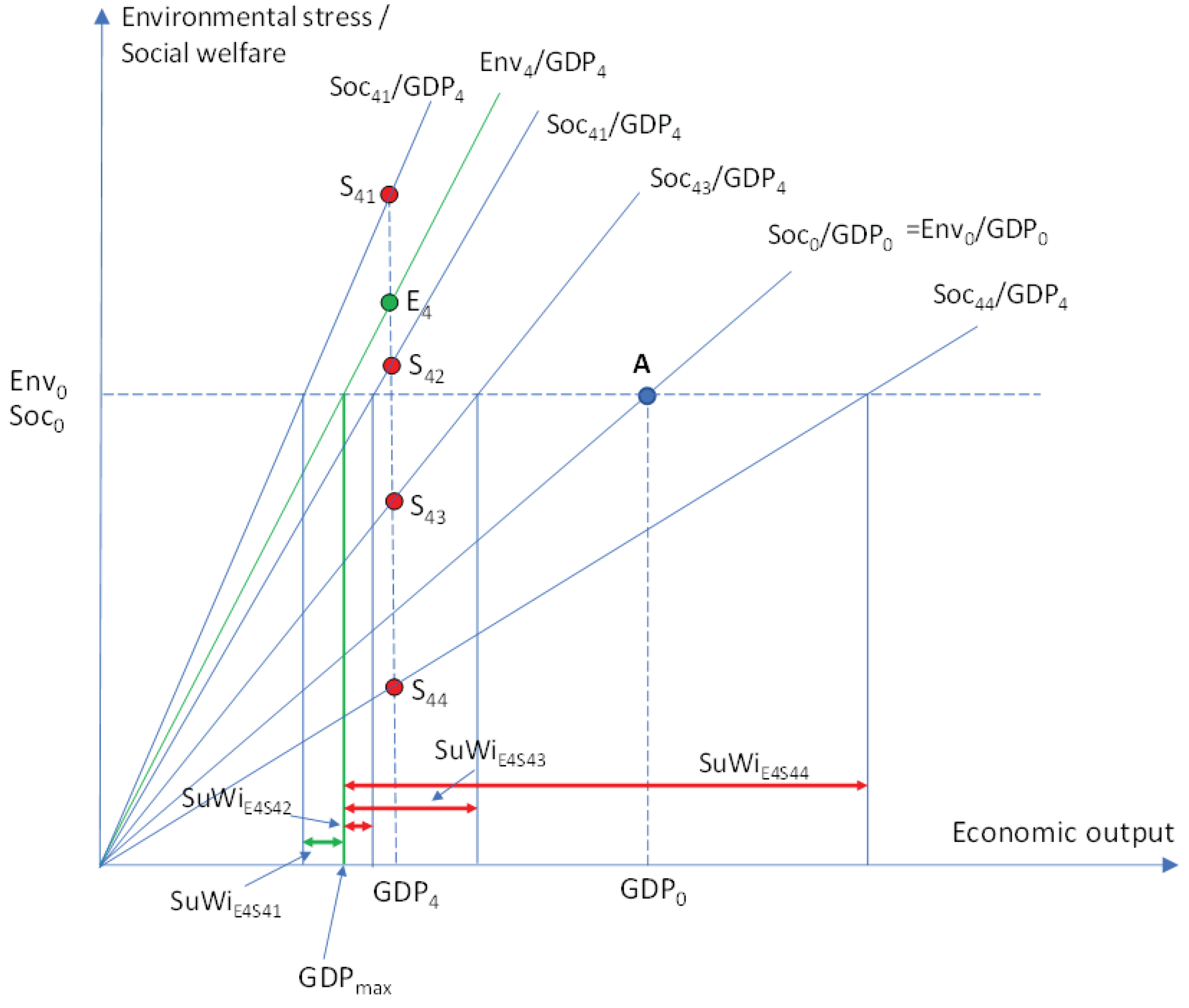

Group 4 (Figure A4)

-

Soc41 > Soc0 and Soc41 > Env4 and Soc41/GDP4 > Env4/GDP4 and Soc41/GDP4 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE4S41) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDPmin < GDP4 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc42 > Soc0 and Soc42 < Env4 and Soc42/GDP4 < Env4/GDP4, and Soc42/GDP4 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE4S42) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDPmin < GDP4 > GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc43 < Soc0 and Soc43 < Env4 and Soc43/GDP4 < Env4/GDP4, and Soc43/GDP4 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE4S43) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) even though the actual GDP growth is inside the negative SuWi (GDP4 > GDPmax < GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc44 < Soc0 and Soc44 < Env4 and Soc44/GDP4 < Env4/GDP4, and Soc44/GDP4 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE4S44) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside the negative SuWi (GDP4 < GDPmax < GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

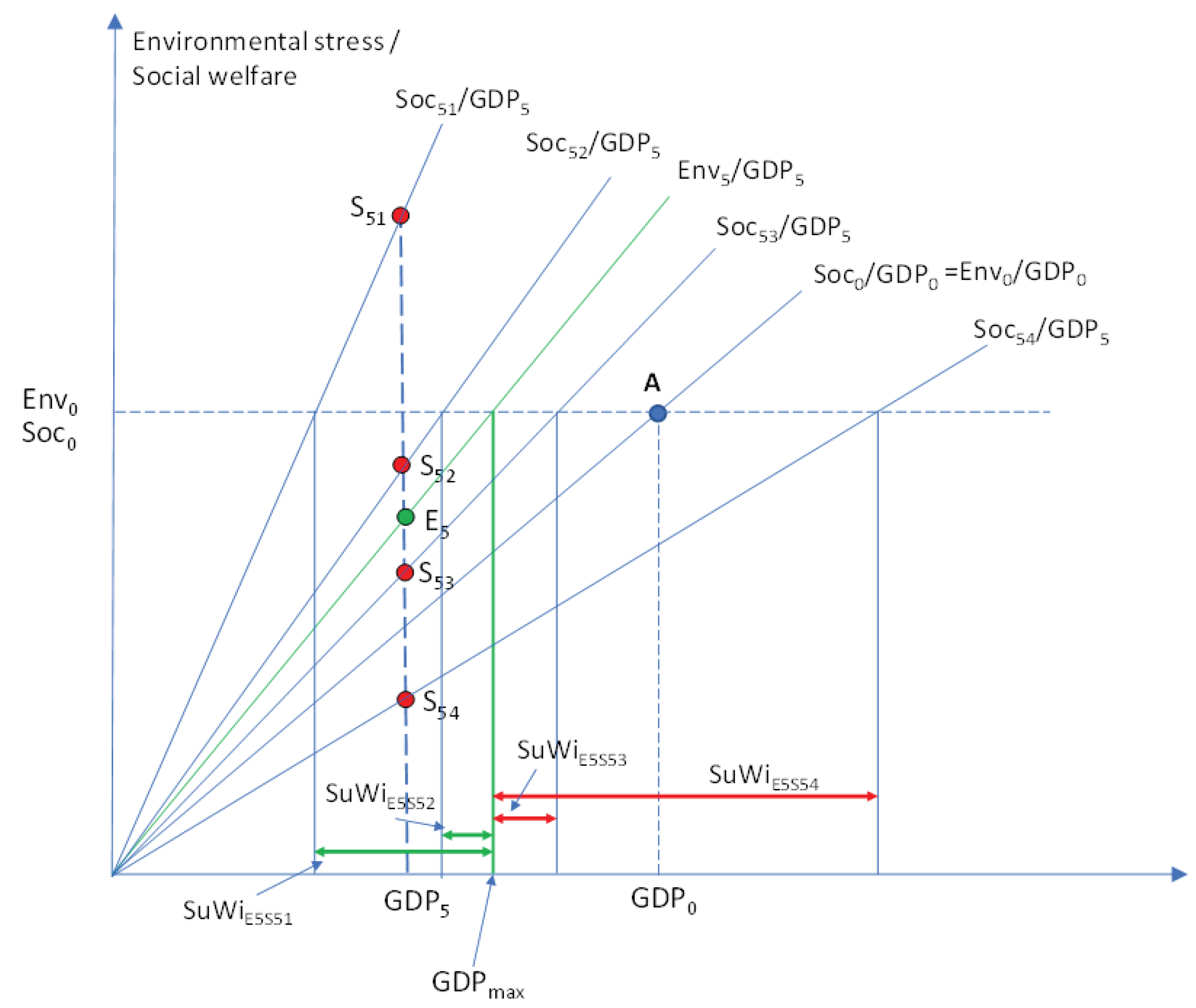

Group 5 (Figure A5)

-

Soc51 > Soc0 and Soc51 > Env5 and Soc51/GDP5 > Env5/GDP5 and Soc51/GDP5 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE5S51) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is inside SuWi (GDPmin < GDP5 < GDPmax). This case fulfills the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc52 < Soc0 and Soc52 > Env5 and Soc52/GDP5 > Env5/GDP5, and Soc52/GDP5 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE5S52) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP5 < GDPmin < GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc53 < Soc0 and Soc53 < Env5 and Soc53/GDP5 < Env5/GDP5, and Soc53/GDP5 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE5S53) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside the negative SuWi (GDP5 < GDPmax < GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc54 < Soc0 and Soc54 < Env5 and Soc54/GDP5 < Env5/GDP5, and Soc54/GDP5 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE5S54) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside the negative SuWi (GDP5 < GDPmax < GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

Group 6 (Figure A6)

-

Soc61 > Soc0 and Soc61 > Env6 and Soc61/GDP6 > Env6/GDP6 and Soc61/GDP6 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE6S61) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is inside SuWi (GDPmin < GDP6 < GDPmax). This case fulfills the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc62 < Soc0 and Soc62 > Env6 and Soc62/GDP6 > Env6/GDP6, and Soc62/GDP6 > Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE6S62) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside SuWi (GDP6 < GDPmin < GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc63 < Soc0 and Soc63 > Env6 and Soc63/GDP6 > Env6/GDP6, and Soc63/GDP6 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE6S63) is positive (GDPmin < GDPmax) but the actual GDP growth is outside the SuWi (GDP6 < GDPmin < GDPmax). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

-

Soc64 < Soc0 and Soc64 < Env6 and Soc64/GDP6 < Env6/GDP6, and Soc64/GDP6 < Soc0/GDP0In this case, Sustainability Window (SuWiE6S64) is negative (GDPmin > GDPmax) and the actual GDP growth is outside the negative SuWi (GDP6 < GDPmax < GDPmin). This case does not fulfill the sustainability criteria.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

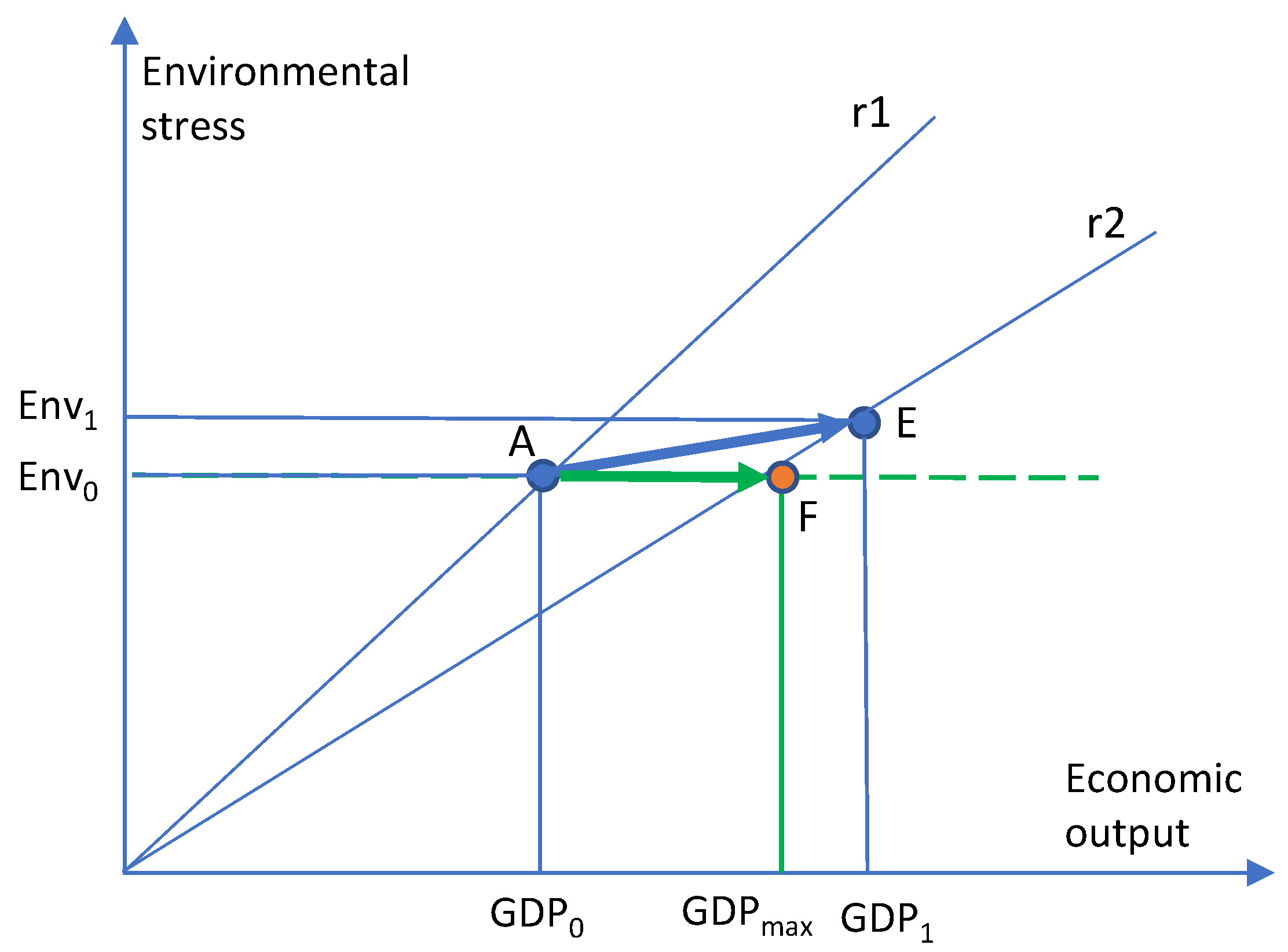

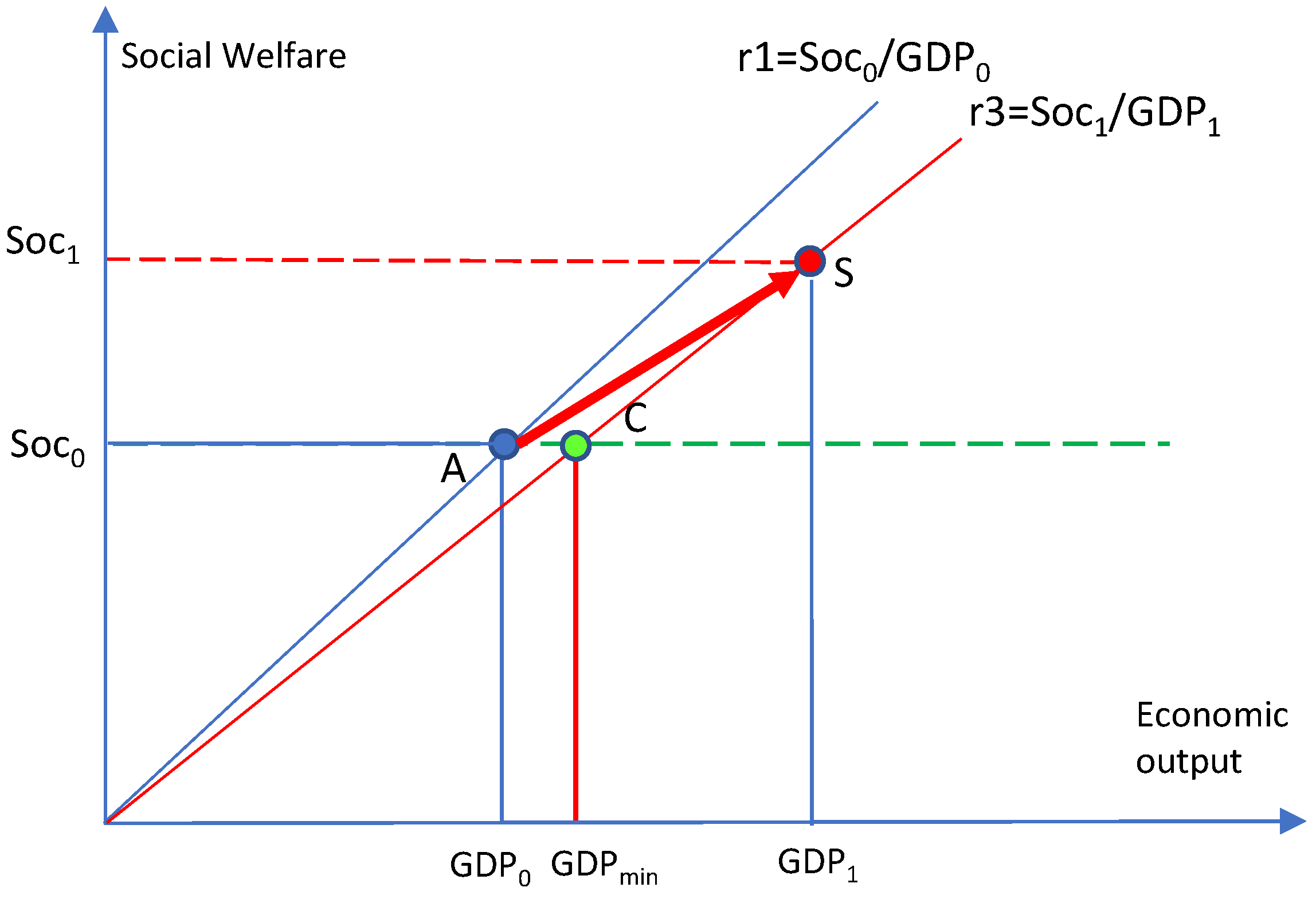

- The original values of all variables are marked with subscript 0 (GDP0, Env0, Soc0, Env0/GDP0)

- The new GDP, Env, and Env/GDP values have a subscript referring to the number of the group (GDP1–GDP6, Env1–Env6, Env1/GDP1–Env6/GDP6

- The new social welfare values have a subscript referring to the number of the group and the number of the four cases case (Soc11–Soc64), and the related social welfare productivities have corresponding subscripts (Soc11/GDP1–Soc64/GDP6)

- The sustainability Windows are marked with a subscript E referring to the environmental stress of the group (Env1–Env6) and with a subscript S referring to the social welfare case inside each group (Soc11–Soc64), i.e. SuWiE1S11–SuWiE6S64.

References

- Meadows, D.H., Randers, J., and Meadows, D.L. (2004). The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co.

- Kaivo-oja, J., Vehmas, J. and Luukkanen, J. (2014a). A note: De-growth debate and new scientific analysis of economic growth. Journal of Environmental Protection 5(15). [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, T. (2022). Toward sustainable wellbeing: Advances in contemporary concepts. Frontiers in Sustainability 3, 807984. [CrossRef]

- Krausmann, F., Gingrich, S., Eisenmenger, N., Erb, K. H., Haberl, H., and Fischer-Kowalski, M. (2009). Growth in global materials use, GDP and population during the 20th century. Ecological Economics 68(10), 2696–270. [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Ed. by Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield.

- IPBES (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), eds E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo. Bonn: IPBES secretariat.

- Piketty, T., (2014a). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

- Piketty, T. (2014b). About Capital in the 21st Century. American Economic Review 105 (5), 48–53. S2CID 14772228. [CrossRef]

- IPSP (2018). Rethinking Society for the 21st Century: Report of the International Panel on Social Progress (IPSP). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Leach, M., Reyers, B., Bai, X., Brondizio, E.S., Cook, C., Díaz, S., Espindola, G., Scobie, M., Stafford-Smith, M., and Subramanian, S.M. (2018). Equity and sustainability in the Anthropocene: A social–ecological systems perspective on their intertwined futures. Global Sustainability 1, E13. [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A., (2015). Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: a preliminary conversation. Sustainability Science 10(3), 451–462. [CrossRef]

- Grubb, M., Okereke, C., Arima, J-, Bosetti, V., Chen, Y., Edmonds, J., Gupta, S., Köberle, A., Kverndokk, S., Malik, A. and Sulistiawati, L. (2022). Introduction and Framing. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P., (2002). Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability: The Prospects for Green Growth. Routledge. London and New York.

- Collste, D., Cornell, S., Randers, J., Rockström, J., and Stoknes, P. (2021). Human well-being in the Anthropocene: Limits to growth. Global Sustainability 4, E30. [CrossRef]

- Isham, A., Mair, S., and Jackson, T. (2021). Wellbeing and productivity in advanced economies: Re-examining the link. Ecological Economics 184, 106989. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G., Dubourg, R., Hamilton, K., Munasinghe, M., Pearce, D. and Young, C. (1997). Measuring Sustainable Development: Macroeconomics and the Environment, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

- Boskin, M.J. (2000). Economic measurement: Progress and challenges. American Economic Review 90/2), 247-252. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. and Mäler, K.-C. (2000). Net national product, wealth and social well-being, Environment and Development Economics, 5(1-2), 69-93. [CrossRef]

- Kaivo-oja, J., Luukkanen, J. and Malaska, P. (2001). Sustainability evaluation frameworks and alternative analytical scenarios of national economies. Population and Environment. A Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 23(2), 193–215. [CrossRef]

- Brock, W.A., Taylor, M.S., Aghion, P. and Durlauf, S.N. (2005), Chapter 28 - Economic Growth and the Environment: A Review of Theory and Empirics. Handbook of Economic Growth. Elsevier, 1749-1821. [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, D.W. and Schreyer, P. (2017). Measuring individual economic well-being and social welfare within the framework of the system of national accounts. Review of Income and Wealth, 63(2), 460-477. [CrossRef]

- Hueting, R. (1980). New Scarcity and Economic Growth. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

- Desai, M. (1994). The measurement problem in economics. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 41(1), 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Hoffrén, J. (2001). Measuring the Eco-efficiency of Welfare Generation in a National Economy. The Case of Finland. Statistics Finland, Research reports 233. Helsinki.

- Fabozzi, F.J., Focardi, S., Ponta, L., Rivoire, M. and Mazza, D. (2022). The economic theory of qualitative green growth. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 61, 242-254. [CrossRef]

- Max-Neef, M. (1995). Economic growth and quality of life: A threshold hypothesis. Ecological Economics 15, 115-118. [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K., Bolin, B., Costanza, R., Dasgupta, P., Folkee, C., Holling, C.S., Jansson, B.-O., Levin, S., Mäler, K.-G., Perring, C., and Pimentel, D. (1995). Economic growth, carrying capacity, and the environment. Ecological Economics 15(2), 91–95. [CrossRef]

- Bergh, van den, J. (2010). The GDP paradox. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30. 117-135. [CrossRef]

- WCED (1987). Our Common Future. World Commission on Environment and Development. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Jamieson, D. (1998). Sustainability and beyond. Ecological Economics 24, 183–192. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, A. and Láng, I. (2005). The Literature Aftermath Of The Brundtland Report ‘Our Common Future’. A Scientometric Study Based On Citations In Science And Social Science Journals. Environment, Development and Sustainability 7, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Olawumi, T. and Chan, D.W.M. (2018). A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production. Journal of Cleaner Production 183, 231–250. [CrossRef]

- De Toledo, R.F., Miranda Junior, H.L., Farias Filho, J.R. and Gomes Costa, H. (2019). A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and project management dataset. Data in Brief 25(3), 104312. [CrossRef]

- Hajan, M. and Kashani, S.J. (2021). Evolution of the concept of sustainability. From Brundtland Report to sustainable development goals. In Hussain, C.M. and Velasco-Muñoz, J.F. (eds), Sustainable Resource Management, Modern Approaches and Contexts. 1–24. Elsevier, Amsterdam/Oxford/ Cambridge, Ma. [CrossRef]

- Holden, E., Linnerud, K. and Banister, D. (2014). Sustainable development: Our Common Future revisited. Global Environmental Change 26, 130–139. [CrossRef]

- Gibbes, C., Hopkins, A.L., Díaz, A.I. and Jimenez-Osornio, J. (2018). Defining and measuring sustainability: a systematic review of studies in rural Latin America and the Caribbean. Environment, Development and Sustainability 22, 447–468. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J. (2023). Quantifying the levels, nature, and dynamics of sustainability for the UK 2000–2018 from a Brundtland perspective. Environment, Development and Sustainability, online. [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y. and Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science 14, 681–695. [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, J.A. (2006). Sustainable development—historical roots of the concept. Environmental Science 3, 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L., Randers, J.; and Behrens III, W.W. (1972). The Limits to Growth; A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N., (1986). The entropy law and the economic process in retrospect. Eastern Economic Journal 12(1), pp.3–25.

- Daly, H.E. (1990). Toward some operational principles of sustainable development. Ecological Economics 2, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, C.J. and Ruth, M. (1997). When, where, and by how much do biophysical limits constrain the economic process? A survey of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen´s contribution to ecological economics? Ecological Economics 22, 203–223. [CrossRef]

- Kaivo-oja, J. (1999). Alternative scenarios of social development: Is analytical sustainability policy analysis possible? How? Sustainable Development 7(3), 140–150. [CrossRef]

- Kaivo-oja, J. (2002). Social and ecological destruction in the first class: A plausible social development scenario. Sustainable Development 10(1), 63–66. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. (2007). The Idea of Sustainable Development. Sustainability Science 2, 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Bander, J.A. (2007). Viewpoint: Sustainability: Malthus revisited. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique 40(1), 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Luukkanen, J. Kaivo-oja, J., and Vehmas, J. (2022). Comparative analysis of ASEAN countries using Sustainability Window and Doughnut Economy models. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development 15(1), 39–56.

- Solow, R.M. (1973). Is the end of the world at hand? Challenge 16 (1): 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. (1974). Growth with exhaustible natural resources: Efficient and optimal growth paths. The Review of Economic Studies 41: 123–137.

- Barbier, E.B. and Markandya, A. (1990). The conditions for achieving environmentally sustainable development. European Economic Review 34(2-3), 659–669. [CrossRef]

- Peretto, P.F. (2021). Thought scarcity to prosperity: Toward a theory of sustainable growth. Journal of Monetary Economics 117, 243–257. [CrossRef]

- Victor, P.A. (1991). Indicators of sustainable development. Some lessons from capital theory. Ecological Economics 4, 191–213. [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R. and Daly, H.E. (1992). Natural capital and sustainable development. Conservation Biology 6, 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. (1993). Introduction to essays toward a steady-state economy. In H.E. Daly, K.N. Townsend. Valuing the Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 267-274.

- Daly, H.E. (1996). Beyond Growth. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Daly, H.E. (1997). Georgescu-Roegen versus Solow/Stiglitz. Ecological Economics 22, 261–266. [CrossRef]

- Trainer, T. (2020). De-growth: Some suggestions from the simpler way perspective. Ecological Economics 167, 106436. [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, C.J. and Ruth, M. (1997). When, where, and by how much do biophysical limits constrain the economic process? A survey of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen´s contribution to ecological economics? Ecological Economics 22, 203–223. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, J. (2009). Socially sustainable economic de-growth. Development and Change 40(6), 1099–1119. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, J., Pascual, U., Vivien, F-D., and Zaccai, E. (2010). Sustainable de-growth: Mapping the context, criticism and future prospects of an emergent paradigm. Ecological Economics 69(9), 1741–1747. [CrossRef]

- Luukkanen et al., 2014.

- Kaivo-oja, J., Panula-Ontto, J., Vehmas, J., and Luukkanen, J. (2014b). Relationships of the dimensions of sustainability as measured by the sustainable society index framework. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 21(1), 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Latouche, S. (2004). Degrowth economics. Why less should be so much more. Le Monde Diplomatique November 2004.

- Fournier, V. (2008). Escaping from the economy: the politics of degrowth. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 28(11/12), 528–545.

- Georgescu- Roegen, N. (1975). Energy and economic myth. Southern Economic Journal 41(3), 347–381. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G. M., and Krueger, A. B. (1991). Environmental impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 3914, NBER, Cambridge MA.

- Stern, D.I., (2004). The rise and fall of the Environmental Kuznets curve, World Development 32(8), 1419–1439. [CrossRef]

- Commoner, B., 1972. A bulletin dialogue on ‘the closing circle’: response. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 28, 42–56.

- Ehrlich, P.R., Holdren, J.P., (1972). A bulletin dialogue on the ‘closing circle’: critique one-dimensional ecology. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 28, 16–27.

- Chertow, M.R. (2001). The IPAT Equation and Its Variants. Changing Views of Technology and Environmental Impact. Journal of Industrial Ecology 4(4), 13–29. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y., (1990). Impact of carbon dioxide emission control on GNP growth: interpretation of proposed scenarios. In: Paper presented to the IPCC Energy and Industry Subgroup, Response Strategies Working Group. Paris (mimeo).

- Wang, H., Ang, B.W. and Su, B., (2017). Assessing drivers of economy-wide energy use and emissions: IDA versus SDA. Energy Policy 107, 585–599. [CrossRef]

- Luukkanen, J., Kaivo-oja, J., Vähäkari, N., O’Mahony, T., Korkeakoski, M., Panula-Ontto, J.1, Phonhalath, K., Nanthavong, K., Reincke, K., Vehmas, J, and Hogarth, N.J. (2019) Green economic development in Lao PDR: a Sustainability Window analysis of Green Growth Productivity and the Efficiency Gap. Journal of Cleaner Production 211, 818–829. [CrossRef]

- Waas, T., Hugé, J., Block, T., Wright, T., Benitez-Capistros, F. and Verbruggen, A. (2014). Sustainability Assessment and Indicators: Tools in a Decision-Making Strategy for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 6(9), 5512–5534. [CrossRef]

- Luukkanen, J., Kaivo-oja, J., Vehmas, J., Panula-Ontto, J., and Häyhä, L., (2015). Dynamic sustainability. Sustainability window analysis of Chinese poverty-environment nexus development. Sustainability 7(11), 14488–14500. [CrossRef]

- Hueting, R. (1990). The Brundtland Report: A matter of conflicting goals. Ecological Economics 2, 109–117. [CrossRef]

- Lélé, S. (1991). Sustainable development: A critical review. World Development, 19(6), 607–621. [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I., Morioka, S.N. and Sznelwar, L.-I. (2014). When sustainable development risks losing its meaning. Delimiting the concept with a comprehensive literature review and a conceptual model. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 83, 7-20. [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I., Morioka, S.N. and Sznelwar, L.-I. (2017). Are we making decisions in a sustainable way? A comprehensive literature review about rationalities for sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production. Vol. 145, 310-322. [CrossRef]

- Gusmão Caiado, R.G., Leal Filho, W. and Ávila, Lucas Veigas (2018). A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. Journal of Cleaner Production. Vol. 198, 1276-1288. [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. (2019). Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. (2019). The contradiction of the Sustainable Development Goals: Growth versus ecology on a finite planet. Sustainable Development 27(5), 873–884. [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., and Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

- Fleurbaey, M., (2009). Beyond GDP: the quest for a measure of social welfare. Journal of Economic Literature 47(4), 1029–1075. [CrossRef]

- Sathaye, J., A. Najam, C. Cocklin, T. Heller, F. Lecocq, J. Llanes-Regueiro, J. Pan, G. Petschel-Held , S. Rayner, J. Robinson, R. Schaeffer, Y. Sokona, R. Swart, H. Winkler (2007). Sustainable Development and Mitigation. In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- Sabin, P., (2013). The Bet: Paul Ehrlich, Julian Simon: Our Gamble over Earth’s Future. Yale University Press. New Haven and London.

- Neumayer, E. (2010). Weak versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK; Northhampton, MA, 272. [CrossRef]

- uukkanen, J., Vehmas, J., Kaivo-oja, J., (2021). Quantification of doughnut economy with the sustainability window method: Analysis of development in Thailand, Sustainability 13(2), 847. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A. and Luukkanen, J. (2022). Sustainable development in Cuba assessed with sustainability window and doughnut economy approaches. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 29(2), 176–186. [CrossRef]

- Vehmas, J., Kaivo-oja, J. and Luukkanen, J. (2016). Sustainability cycles in China, India, and the world? Eastern European Business and Economics Journal 2(2), 139–164.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).