Submitted:

03 April 2024

Posted:

03 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

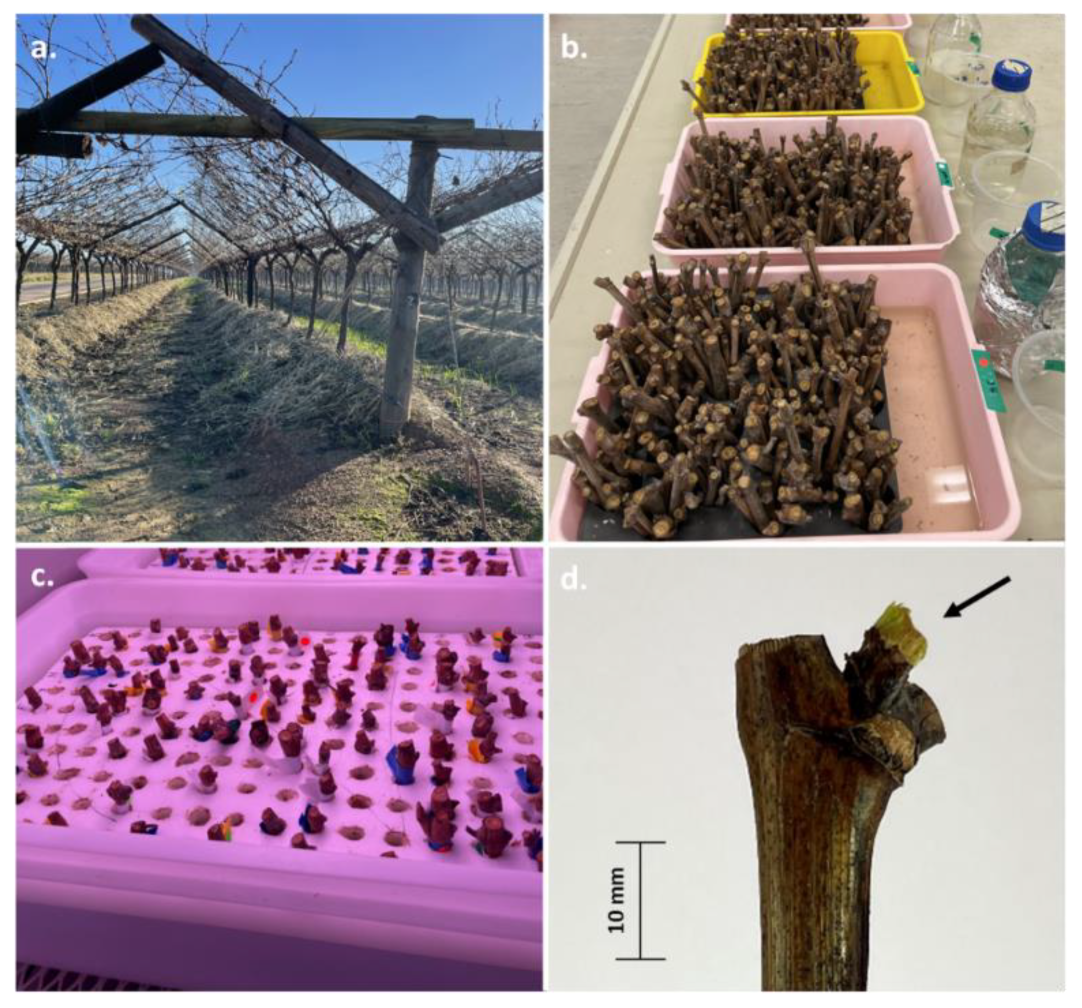

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Chill Unit Recordings

2.3. Forced Bud-Break Assays

2.3.1. Preparation of Plant Material, Experimental Design & Data Collection

2.4. Small-Scale Field Trial Dormancy-Release Assay

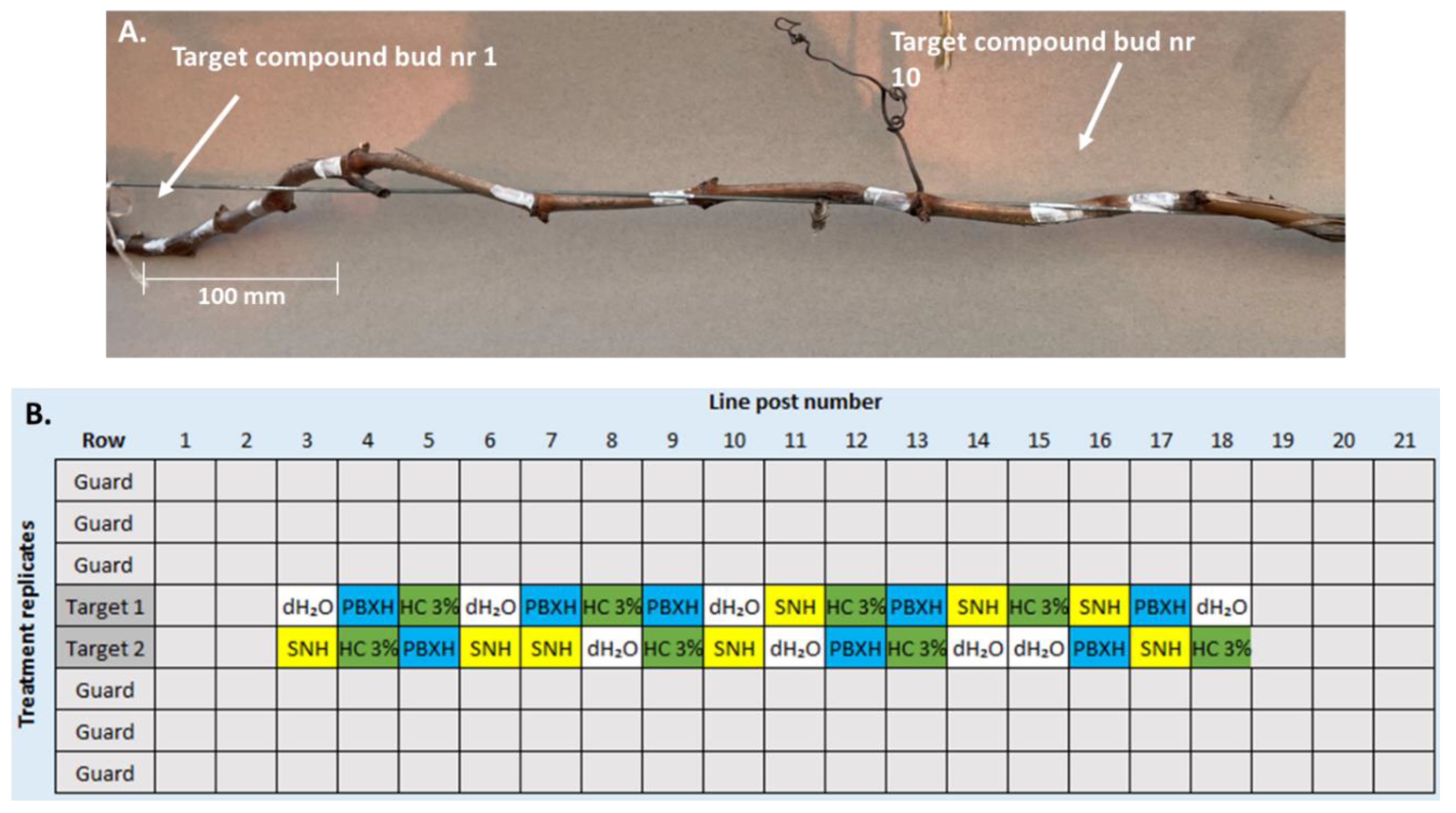

2.4.1. Experimental Site and Design

2.4.2. Treatments Evaluated and Dosage Concentrations

2.5. Data Handling

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- Onset: The number of days until the bud-break date was reached. Larger positive values indicate delayed time until onset was reached.

- Bud-break rate: The slope between 0 % bud-break and final bud-break % indicates bud-break rate between the first and last buds that have broken. The slope parameter (or more generally termed “hillslope”) indicates the steepness of decrease. Thus, the larger the slope value, the steeper the decrease. For an increasing function (such as in the current study), the opposite is true: the larger the negative slope is, the steeper the increase, and the faster the bud-break rate.

- Half maximal effective concentration (EC50): Number of days to reach 50 % bud-break after treatment. This is also a parameter indicating speed. Larger positive values indicate delayed time until EC50 was reached.

- Final bud-break percentage: The upper value of the cumulative bud-break percentage growth curve (plateau). Larger positive values indicate a higher final bud-break percentage.

3. Results

3.1. Chill Units in the VINEYARD

3.2. Forced bud-Break Assays

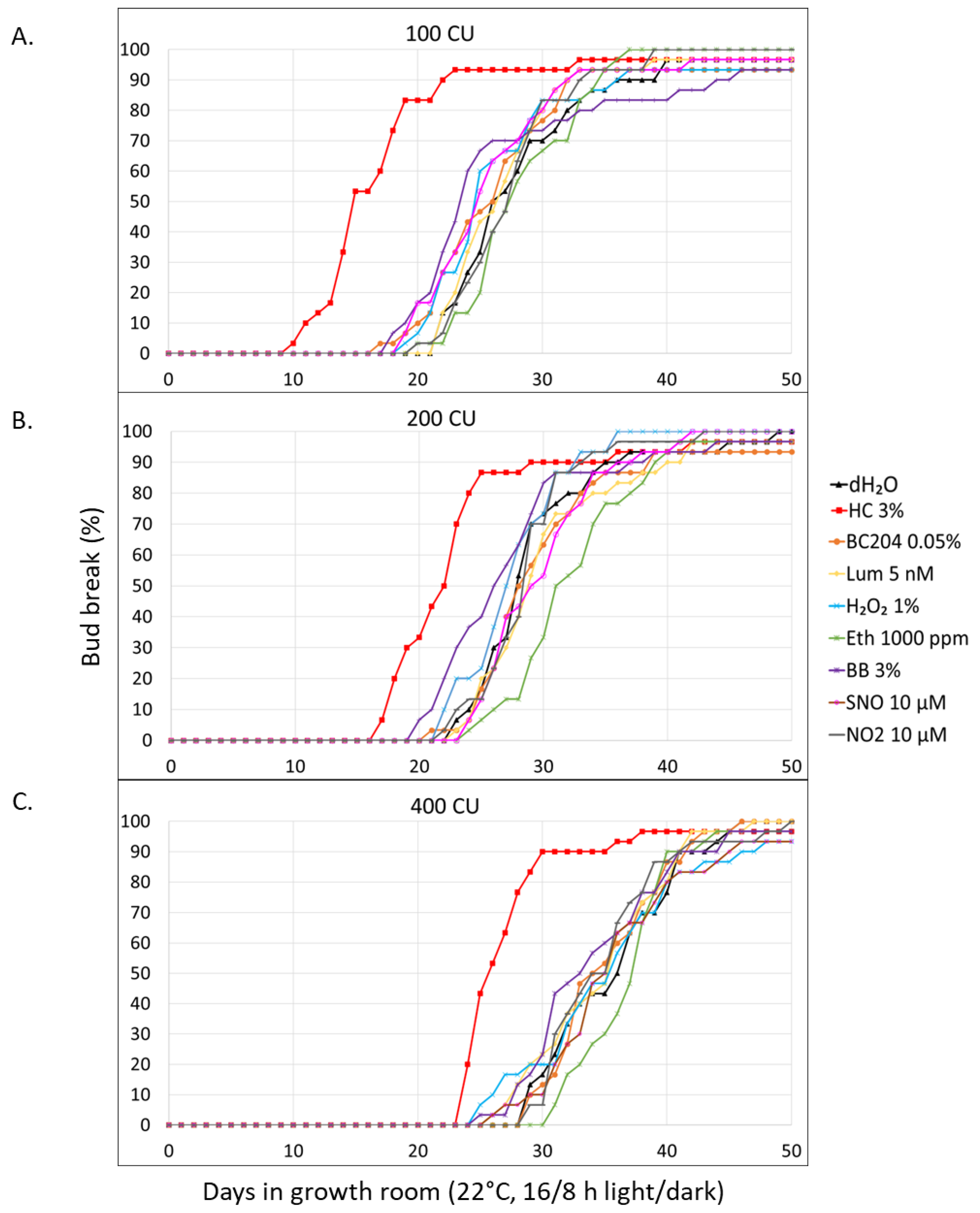

3.2.1. Evaluation of Plant Biostimulants (BC204 and Lumichrome), and Individual Biochemical Agents

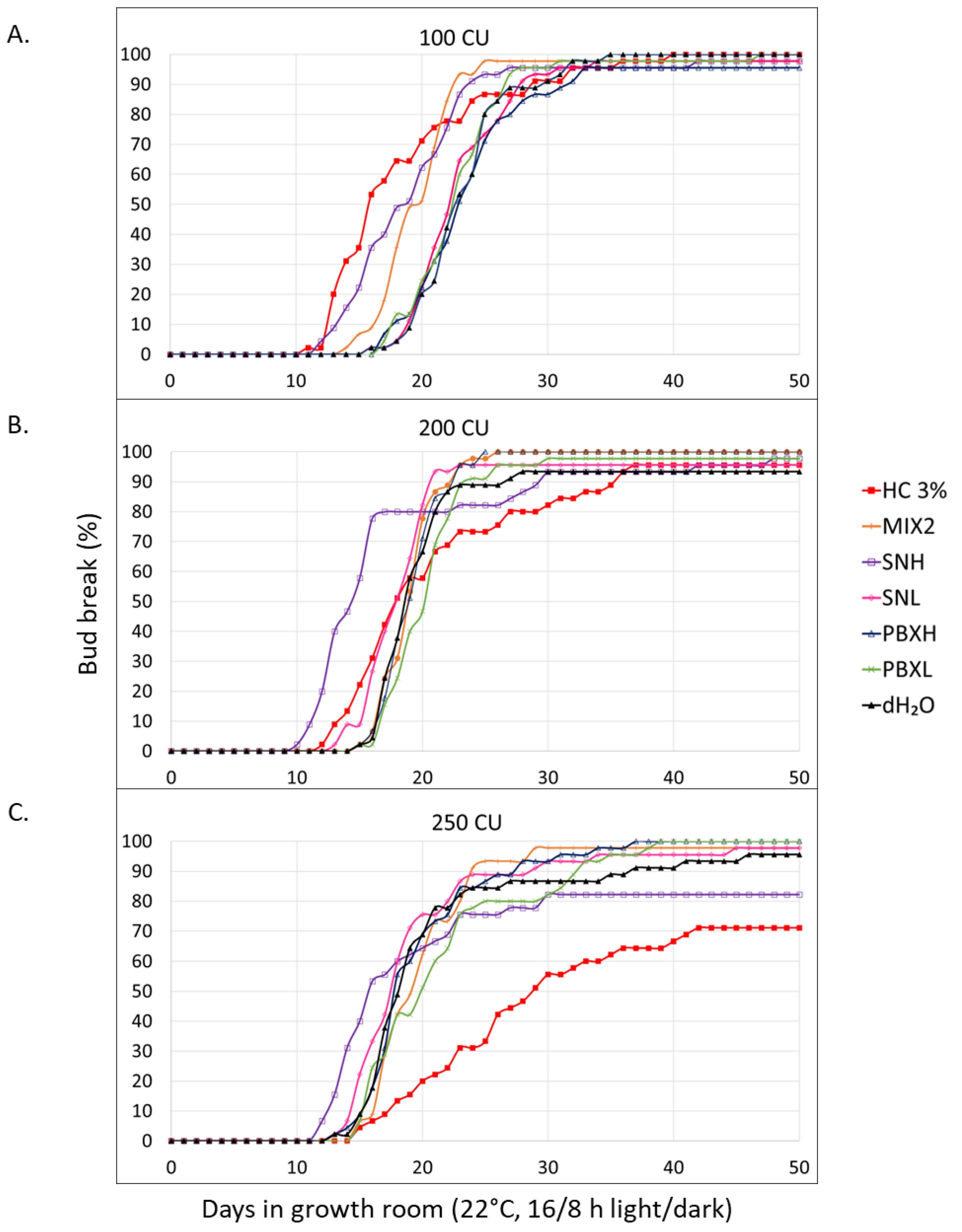

3.2.2. Evaluation of Plant Biostimulants SN and PBX, as Well as Biochemical Agents Combined with Lumichrome and BC204

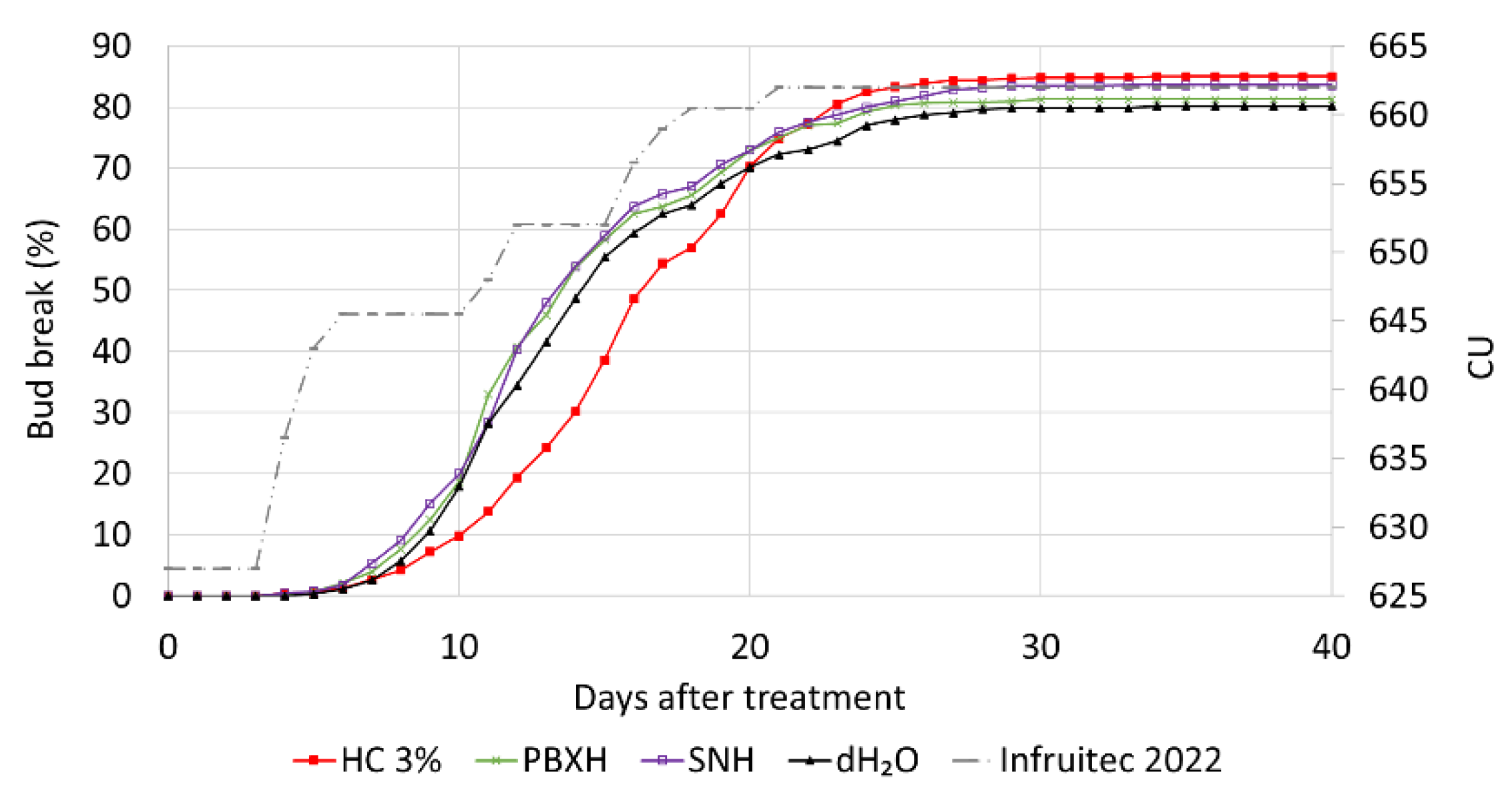

3.3.3. Small-Scale Field Trial: Evaluation of Plant Biostimulants SN and PBX

4. Discussion

4.1. Forced Bud-Break Assays

4.1.1. Evaluation of Plant Biostimulants BC204, Lumichrome, and Candidate Biochemical Agents

4.1.2. Evaluation of Plant Biostimulants SN and PBX, as Well as Biochemical Agents Combined with Lumichrome and BC204

4.2. Small-Scale Field Trial: Evaluation of Plant Biostimulants SN and PBX

4.3. On the Development of Novel Treatments: Summary Model of Key Components

- A source of hypoxia, such as an oil-based adjuvant or mineral/vegetable oil

- Inclusion of additional supplementation of nitrites and/or nitrates such as potassium nitrite (KNO2) or KNO3

- Amino acids

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Or, E.; Vilozny, I.; Eyal, Y.; Ogrodovitch, A. The Transduction of the Signal for Grape Bud Dormancy Breaking Induced by Hydrogen Cyanamide May Involve the SNF-like Protein Kinase GDBRPK. Plant Mol Biol 2000, 43, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Forney, C.F.; Bondada, B. Renewal of Vascular Connections between Grapevine Buds and Canes during Bud Break. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 233, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoozlian, N.K. Chilling Temperature and Duration Interact on the Budbreak of `Perlette’ Grapevine Cuttings. HortScience 1999, 34, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avenant, E.; Avenant, J.H. Chill Unit Accumulation and Necessity of Rest Breaking Agents in South African Table Grape Production Regions. BIO Web of Conferences 2014, 3, 01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.A.; Seeley, S.D.; Walker, D.R. A Model for Estimating the Completion of Rest for ‘Redhaven’ and ‘Elberta’ Peach Trees1. HortScience 1974, 9, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, S.; Erez, A.; Couvillon, G.A. The Temperature Dependence of Dormancy Breaking in Plants: Computer Simulation of Processes Studied under Controlled Temperatures. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1987, 126, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, S.; Erez, A.; Couvillon, G.A. The Temperature Dependence of Dormancy Breaking in Plants: Mathematical Analysis of a Two-Step Model Involving a Cooperative Transition. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1987, 124, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundeji, A.A.; Jordaan, H. A Simulation Study on the Effect of Climate Change on Crop Water Use and Chill Unit Accumulation. South African Journal of Science 2017, 113, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Taylor, C. The Dynamic Model Provides the Best Description of the Chill Process on ‘Sirora’ Pistachio Trees in Australia. HortScience 2011, 46, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SATI Production Overview Statistical Booklet; South African Table Grape Industry, 2018;

- Tharaga, P.C. Impacts of Climate Change on Accumulated Chill Units at Selected Fruit Production Sites in South Africa. 2014.

- Sheshadri, S.H.; Sudhir, U.; Kumar, S.; Kempegowda, P. DORMEX®-Hydrogen Cyanamide Poisoning. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 2011, 4, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SATI Statistics of Table Grapes in South Africa; South African Table Grape Industry, 2022;

- Nir, G.; Shulman, Y.; Fanberstein, L.; Lavee, S. Changes in the Activity of Catalase (EC 1.11.1.6) in Relation to the Dormancy of Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Buds 1 2. Plant Physiology 1986, 81, 1140–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, J.L.; Stuker, H. Effect of Mineral Oil and Hydrogen Cyanamide Concentrations on Apple Dormancy, Cv. Gala. Acta Hortic. 1995, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, F.J.; Lira, W. Possible Role of Catalase in Post-Dormancy Bud Break in Grapevines. Journal of Plant Physiology 2005, 3, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ophir, R.; Pang, X.; Halaly, T.; Venkateswari, J.; Lavee, S.; Galbraith, D.; Or, E. Gene-Expression Profiling of Grape Bud Response to Two Alternative Dormancy-Release Stimuli Expose Possible Links between Impaired Mitochondrial Activity, Hypoxia, Ethylene-ABA Interplay and Cell Enlargement. Plant Mol Biol 2009, 71, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, F.J.; Vergara, R.; Or, E. On the Mechanism of Dormancy Release in Grapevine Buds: A Comparative Study between Hydrogen Cyanamide and Sodium Azide. Plant Growth Regul 2009, 59, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, J.L.; Berenhauser Leite, G.; Putti, G.L. Apple Tree Budbreak Promoters in Mild Winter Conditions. Acta Hortic. 2008, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, F.J.; Kühn, N.; Vergara, R. Expression Analysis of Phytochromes A, B and Floral Integrator Genes during the Entry and Exit of Grapevine-Buds from Endodormancy. Journal of Plant Physiology 2011, 168, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, R.; Rubio, S.; Pérez, F.J. Hypoxia and Hydrogen Cyanamide Induce Bud-Break and up-Regulate Hypoxic Responsive Genes (HRG) and VvFT in Grapevine-Buds. Plant Mol Biol 2012, 79, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, R.; Parada, F.; Rubio, S.; Pérez, F.J. Hypoxia Induces H2O2 Production and Activates Antioxidant Defence System in Grapevine Buds through Mediation of H2O2 and Ethylene. J Exp Bot 2012, 63, 4123–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, J.L.; Leite, G.B.; Couto, M.; Gabardo, G.C.; Haverroth, F.J. Chemical Induction of Budbreak: New Generation Products to Replace Hydrogen Cyanamide. Acta Hortic. 2014, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudawan, B.; Chang, C.-S.; Chao, H.; Ku, M.S.B.; Yen, Y. Hydrogen Cyanamide Breaks Grapevine Bud Dormancy in the Summer through Transient Activation of Gene Expression and Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species. BMC Plant Biology 2016, 16, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Huang, X.; Shen, Y.; Shen, T.; Zhang, H.; Lin, L.; Wang, J.; Deng, Q.; Lyu, X.; Xia, H. Hydrogen Cyanamide Induces Grape Bud Endodormancy Release through Carbohydrate Metabolism and Plant Hormone Signaling. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauvieux, R.; Wenden, B.; Dirlewanger, E. Bud Dormancy in Perennial Fruit Tree Species: A Pivotal Role for Oxidative Cues. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, A.; Yablowitz, Z.; Aronovitz, A.; Hadar, A. Dormancy Breaking Chemicals; Efficiency with Reduced Phytotoxicity. Acta Hortic. 2008, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segantini, D.M.; Leonel, S.; Ripardo, A.K. da S.; Tecchio, M.A.; Souza, M.E. de Breaking Dormancy of “Tupy” Blackberry in Subtropical Conditions. American Journal of Plant Sciences 2015, 6, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, J.L.; Leite, G.B.; Couto, M.; Francescatto, P. A New Product to Induce Apple Bud Break and Flowering – Syncron ®. Acta Hortic. 2016, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allderman, L.; Steyn, W.J.; Louw, E.D. Alternative Rest Breaking Agents and Vigour Enhancers Tested on “Fuji” Apple Shoots under Mild Conditions. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, September 30 2022; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ardiles, M.; Ayala, M. An Alternative Dormancy-Breaking Agent to Hydrogen Cyanamide for Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) under Low Chilling Accumulation Conditions in the Central Valley of Chile. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium, June 1 2017; pp. 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, D.F.; Rodrigues, S.I.A.; Oliveira, C.M.M.S. Biostimulants to Promote Budbreak in Kiwifruit (Actinidia Chinensis Var. Deliciosa ‘Hayward’). Acta Hortic. 2018, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.G.; Margoti, G.; Biasi, L.A. Sprouting, Phenology, and Maturation of the Italian Grapevine ‘Fiano’ in Campo Largo, PR, Brazil. Semina: Ciências Agrárias 2020, 41, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.B.; Leonel, S.; Souza, J.M.A.; Silva, M. de S.; Ferraz, R.A.; Martins, R.C.; Silva, M.S.C. da Peaches Phenology and Production Submitted to Foliar Nitrogen Fertilizer and Calcium Nitrate. Bioscience Journal 2019, 35, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, J.G.; Dicenta, F.; Sánchez-Pérez, R. Advancing Endodormancy Release in Temperate Fruit Trees Using Agrochemical Treatments. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Calcium in Plants. Annals of Botany 2003, 92, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, J.; Demidchik, V.; Bothwell, J.H.F.; Mylona, P.; Miedema, H.; Torres, M.A.; Linstead, P.; Costa, S.; Brownlee, C.; Jones, J.D.G.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Produced by NADPH Oxidase Regulate Plant Cell Growth. Nature 2003, 422, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendehenne, D.; Hancock, J.T. New Frontiers in Nitric Oxide Biology in Plant. Plant Science 2011, 181, 507–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šírová, J.; Sedlářová, M.; Piterková, J.; Luhová, L.; Petřivalský, M. The Role of Nitric Oxide in the Germination of Plant Seeds and Pollen. Plant Science 2011, 181, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Li, B.; Liao, W.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Jin, X.; Xu, Q. Effect of Nitric Oxide on Dormancy Release in Bulbs of Oriental Lily (Lilium Orientalis) ‘Siberia. ’ The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2015, 90, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.C. Reversible Binding and Inhibition of Catalase by Nitric Oxide. European Journal of Biochemistry 1995, 232, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.C.; Borutaite, V. Nitric Oxide Inhibition of Mitochondrial Respiration and Its Role in Cell Death. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2002, 33, 1440–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asada, K. Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Chloroplasts and Their Functions. Plant Physiology 2006, 141, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savchenko, T.; Tikhonov, K. Oxidative Stress-Induced Alteration of Plant Central Metabolism. Life 2021, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Or, E.; Vilozny, I.; Fennell, A.; Eyal, Y.; Ogrodovitch, A. Dormancy in Grape Buds: Isolation and Characterization of Catalase cDNA and Analysis of Its Expression Following Chemical Induction of Bud Dormancy Release. Plant Science 2002, 162, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dry, P.R.; Coombe, B.G.; Anderson, C.J. Viticulture. Volume 1, Resources; 2nd ed., repr. with alterations.; Winetitles: Ashford, S. Aust., 2005; ISBN 978-0-9756850-0-6.

- Botelho, R.V.; Sato, A.J.; Maia, A.J.; Marchi, T.; Oliari, I.C.R.; Rombolà, A.D. Mineral and Vegetable Oils as Effective Dormancy Release Agents for Sustainable Viticulture in a Sub-Tropical Region. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2016, 91, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbichi, I.; Keyster, M.; Ludidi, N. Effect of Exogenous Application of Nitric Oxide on Salt Stress Responses of Soybean. South African Journal of Botany 2014, 90, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pholo, M.; Coetzee, B.; Maree, H.J.; Young, P.R.; Lloyd, J.R.; Kossmann, J.; Hills, P.N. Cell Division and Turgor Mediate Enhanced Plant Growth in Arabidopsis Plants Treated with the Bacterial Signalling Molecule Lumichrome. Planta 2018, 248, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loubser, J.; Hills, P.N. Analysis of the Molecular and Physiological Effects Following Treatment with BC204 in Arabidopsis Thaliana and Solanum Lycopersicum. PhD thesis, Stellenbosch University: South Africa, 2020.

- Sagredo, K.X.; Theron, K.I.; Cook, N.C. Effect of Mineral Oil and Hydrogen Cyanamide Concentration on Dormancy Breaking in ‘Golden Delicious’ Apple Trees. South African Journal of Plant and Soil 2005, 22, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, J.-M.; Ouanounou, G.; Rouzaire-Dubois, B. The Boltzmann Equation in Molecular Biology. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2009, 99, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, T.R.; Mascha, E.J. Unadjusted Bivariate Two-Group Comparisons: When Simpler Is Better. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018, 126, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoozlian, N.K.; Williams, L.E.; Neja, R.A. Chilling Exposure and Hydrogen Cyanamide Interact in Breaking Dormancy of Grape Buds. HortScience 1995, 30, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoozlian, N.K. Quantifying the Chilling Status of Grapevines and the Response to Dormancy-Breaking Chemicals in the Coachella Valley of California.; HortScience, 1998; Vol. 33, p. 510.

- Hernández, G.; Craig, R.L. Effects of Alternatives to Hydrogen Cyanamide on Commercial Kiwifruit Production. Acta Hortic. 2011, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.; Oliveira, C.M.; Mota, M.; Sousa, R.M. Evaluation of Five Dormancy Breaking Agents to Induce Synchronized Flowering in “Rocha” Pear. Acta Hortic. 2011, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif El-Yazal, M.A.; Seif El-Yazal, S.A.; Rady, M.M. Exogenous Dormancy-Breaking Substances Positively Change Endogenous Phytohormones and Amino Acids during Dormancy Release in ‘Anna’ Apple Trees. Plant Growth Regul 2014, 72, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarem, M.M.; Taha, N.M.; Shakweer, N.H. Studies the Effect of Alternative Dormancy Breaking Agents on “Le-Cont” Pear Cultivar. Journal of Plant Production 2016, 7, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, R.V.; Biasi, L.A.; Maia, A.J.; Nedilha, L.C.B.M.; Viencz, T. Dormancy Release in Asian ‘Hosui’ Pear Trees with the Use of Vegetable and Mineral Oils. Acta Hortic. 2021, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, F.J.; Noriega, X.; Rubio, S. Hydrogen Peroxide Increases during Endodormancy and Decreases during Budbreak in Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Buds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, H.; Sugiura, T.; Sugiura, H. Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide on Breaking Endodormancy in Flower Buds of Japanese Pear (Pyrus Pyrifolia Nakai). Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science 2005, 74, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, F.J.; Vergara, R.; Rubio, S. H2O2 Is Involved in the Dormancy-Breaking Effect of Hydrogen Cyanamide in Grapevine Buds. Plant Growth Regul 2008, 55, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, J.; Sadeghipour, H.R.; Abdolzadeh, A.; Hemmati, K.; Hassani, D.; Vahdati, K. Redox Rather than Carbohydrate Metabolism Differentiates Endodormant Lateral Buds in Walnut Cultivars with Contrasting Chilling Requirements. Scientia Horticulturae 2017, 225, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, K. Effects of Bud Scale Removal, Calcium Cyanamide, GA3, and Ethephon on Bud Break of ‘Muscat of Alexandria’ Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.). Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science 1980, 48, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, E.; Nir, G.; Vilozny, I. Timing of Hydrogen Cyanamide Application to Grapevine Buds. VITIS - Journal of Grapevine Research 1999, 38, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawerroth, F.J.; Petri, J.L.; Leite, G.B. Erger and Calcium Nitrate Concentration for Budbreak Induction in Apple Trees. Acta Hortic. 2010, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, J.; Espada, J.L.; Bernad, D.; Martin, E.; Herrero, M. Effects of Syncron ® and Nitroactive ® on Flowering and Ripening in Sweet Cherry. Acta Hortic. 2017, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Razzaq, A.; Mehmood, S.S.; Zou, X.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.; Xu, J. Impact of Climate Change on Crops Adaptation and Strategies to Tackle Its Outcome: A Review. Plants 2019, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Pérez-López, D.; Sánchez, E.; Centeno, A.; Gómara, I.; Dosio, A.; Ruiz-Ramos, M. Chilling Accumulation in Fruit Trees in Spain under Climate Change. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2019, 19, 1087–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, H.; Hunter, J.J. Mitigation and Adaptation Practices to the Impact of Climate Change on Wine Grape Production, with Special Reference to the South African Context. South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2022, 43, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Craig, R.L. Effects of Alternatives to Hydrogen Cyanamide on Commercial ‘Hayward’ Kiwifruit Production. Acta Hortic. 2016, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Relevance to dormancy-release molecular models | Application concentration |

Treatment code name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dormex® | Positive control | 3% v/v [47] | HC 3% |

| Distilled water | Negative control | NA | dH2O |

| H2O2 | ROS | 1% v/v [22] | H2O2 1% |

| S-Nitrosoglutathione | NO donor | 10 μM [48] | SNO 10 μM |

| Diethylamine NONOate sodium salt hydrate | NO donor | 10 μM [48] | NO2 10 μM |

| Lumichrome | Riboflavin derivative | 5 nM [49] | Lum 5 nM |

| BC204 (Commercial PB) | Citrus-based plant extract | 0.05% v/v [50] | BC204 0.05% |

| BUDBREAK® mineral oil | Hypoxia | 3% v/v [51] | BB 3% |

| Ethephon | Ethylene supplement | 0.206% v/v [22] |

| Treatment | Relevance to dormancy-release molecular models |

Application concentration | Treatment code name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dormex® | Positive control | 3% v/v | HC 3% |

| Distilled water | Negative control | NA | dH2O |

| SN (Commercial PB) | Amino acids formulations (SBB-01), synergistic effect provided by a calcium supplement (NDY-01) | 2% v/v SBB-01 and 20% v/v NDY-01 (recommended by manufacturer) | SNH |

| SN | 0.2% v/v SBB-01 and 2% v/v NDY-01 | SNL | |

| PBX (Commercial PB) | Amino acid formulations which alter metabolism in plants | 1.5% v/v (recommended by manufacturer) | PBXH |

| PBX | 0.15% v/v | PBXL | |

| Combination of selected biochemical agents (refer to Table 1) | Refer to Table 1 | 1% v/v hydrogen peroxide, 10 μM S-nitrosoglutathione, 10 μM diethylamine NONOate sodium salt hydrate, 5nM lumichrome, 0.05% v/v BC204 and 3% v/v BUDBREAK® mineral oil | MIX2 |

| Coefficient estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bud-break parameter: definition | Treatment | 100 | 200 | 400 |

| Onset: Number of days to first bud-break | HC 3% | 9.86f | 16.12f | 25.41abcd |

| dH2O | 20.07a | 22.17b | 27.08b | |

| BC204 0.05% | 18.08c | 22.49bc | 27.58b | |

| Lum 5 nM | 20.47ab | 22.34bc | 25.91c | |

| H2O2 1% | 18.80d | 21.07d | 24.48d | |

| Eth 1000 ppm | 20.93b | 24.49a | 30.81a | |

| BB 3% | 16.48e | 19.16e | 25.17cd | |

| SNO 10 μM | 17.81c | 22.74bc | 27.36b | |

| NO2 10 μM | 20.83b | 22.86c | 27.85b | |

| Rate: Slope between onset and final bud-break % | HC 3% | -0.48a | -0.48ab | -0.71a |

| dH2O | -0.37b | -0.46ac | -0.31bc | |

| BC204 0.05% | -0.34b | -0.42dc | -0.36de | |

| Lum 5 nM | -0.45a | -0.39d | -0.30bc | |

| H2O2 1% | -0.42a | -0.45ac | -0.25f | |

| Eth 1000 ppm | -0.37b | -0.38d | -0.49g | |

| BB 3% | -0.34b | -0.38d | -0.30b | |

| SNO 10 μM | -0.36b | -0.38d | -0.33dc | |

| NO2 10 μM | -0.43a | -0.54b | -0.39e | |

| EC50: Number of days to 50 % of final bud-break %. | HC 3% | 15.51g | 21.32h | 25.86f |

| dH2O | 26.82b | 27.99e | 35.39b | |

| BC204 0.05% | 25.43d | 28.37c | 34.80c | |

| Lum 5 nM | 26.07c | 28.82d | 34.60c | |

| H2O2 1% | 24.77e | 27.16f | 34.92c | |

| Eth 1000 ppm | 28.03a | 31.71a | 36.50a | |

| BB 3% | 23.79f | 25.82g | 33.52e | |

| SNO 10 μM | 24.98e | 29.25b | 34.93c | |

| NO2 10 μM | 26.96b | 28.16ce | 34.26d | |

| Final percentage: Upper limit of cumulative bud-break % curve | HC 3% | 95.95c | 96.40bc | 95.65e |

| dH2O | 95.81c | 97.48b | 100a | |

| BC204 0.05% | 96.85bc | 94.23e | 99.99ab | |

| Lum 5 nM | 96.35c | 95.27ec | 100a | |

| H2O2 1% | 92.61d | 99.94a | 98.19cd | |

| Eth 1000 ppm | 100a | 96.69bd | 97.10d | |

| BB 3% | 91.87d | 95.43ecd | 98.14cd | |

| SNO 10 μM | 97.77b | 99.38a | 95.55e | |

| NO2 10 μM | 99.34a | 99.27a | 98.72cb | |

| Coefficient estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bud-break parameter: definition | Treatment | 100 | 200 | 250 |

| Onset: Number of days to first bud-break | HC 3% | 9.69f | 10.35c | 13.72ab |

| dH2O | 18.20a | 15.48a | 13.77ac | |

| MIX2 | 15.32d | 15.47a | 14.14a | |

| SNH | 11.67e | 9.81c | 10.14e | |

| SNL | 17.33b | 13.86b | 12.60bd | |

| PBXH | 16.76c | 15.50a | 13.20bc | |

| PBXL | 17.32b | 15.88a | 12.34d | |

| Rate: Slope between onset and final bud-break % | HC 3% | -0.32a | -0.29a | -0.23a |

| dH2O | -0.52d | -0.79b | -0.59c | |

| MIX2 | -0.62b | -0.83b | -0.52bc | |

| SNH | -0.39c | -0.57c | -0.44b | |

| SNL | -0.50d | -0.72bd | -0.52bc | |

| PBXH | -0.44e | -0.77b | -0.47b | |

| PBXL | -0.52d | -0.65cd | -0.31d | |

| EC50: Number of days to 50 % of final bud-break %. | HC 3% | 17.02e | 18.71bc | 24.96a |

| dH2O | 22.88b | 18.57c | 17.99f | |

| MIX2 | 19.31c | 18.77bc | 19.09c | |

| SNH | 18.29d | 14.05e | 15.67g | |

| SNL | 22.35a | 17.64d | 17.46e | |

| PBXH | 22.83b | 18.89b | 18.57d | |

| PBXL | 22.40a | 19.81a | 20.18b | |

| Final percentage: Upper limit of cumulative bud-break % curve | HC 3% | 98.15b | 93.25d | 70.71e |

| dH2O | 99.46a | 92.90d | 91.57c | |

| MIX2 | 97.95b | 99.85a | 97.42a | |

| SNH | 97.29b | 92.65d | 81.03d | |

| SNL | 97.43b | 95.76c | 95.24b | |

| PBXH | 95.31c | 99.89a | 98.11a | |

| PBXL | 99.18a | 97.56b | 97.66a | |

| Bud-break parameter: definition | Treatment | Coefficient estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Onset: Number of days to first bud-break | HC 3% | 8.38a |

| dH2O | 6.53b | |

| PBXH | 6.07bc | |

| SNH | 5.70c | |

| Rate: Slope between onset and final bud-break % | HC 3% | -0.36a |

| dH2O | -0.38a | |

| PBXH | -0.39a | |

| SNH | -0.38a | |

| EC50: Number of days to 50 % of final bud-break %. | HC 3% | 15.61a |

| dH2O | 13.09b | |

| PBXH | 12.62c | |

| SNH | 12.74c | |

| Final percentage: Upper limit of cumulative bud-break % curve | HC 3% | 85.26a |

| dH2O | 78.69d | |

| PBXH | 80.20c | |

| SNH | 82.28b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).