1. Introduction

As a whole, Earth and the people who reside on it require energy to continue sustaining life, especially with a growing population. As technology advances, it has been shown that, as a society, humans are slowly phasing out nonrenewable energy sources such as fossil fuels and moving to more abundant and renewable sources. However, the majority of energy produced in the world still derives from fossil fuels, as of 2019, an immense 84% of the primary total energy produced originates from fossil fuels (Ritchie, et al. 2020). While the global society makes this transition over to a cleaner, renewable energy source, it is critical to use the infrastructure that has already been set up in the form of oil and gas. Certain technological advances have been made to be as efficient and clean as humanly possible (Kamali, et al. 2020). Wastewater treatment is becoming a larger issue (Radelyuk, et al. 2019). This large amount of wastewater is a consequence of modern-day drilling techniques and can be separated into two categories, flow back and produced water (Kondash, et al. 2016). Put simply, flow back is the fluid that returns to the surface of the well after drilling. Well stimulation treatments are then completed after the well is drilled and before recovered oil and gas. These processes, such as hydraulic fracturing or acidizing, add even more fluid and internal water to the well that will later be removed and placed in the second wastewater category. Produced water consists mainly of existing fluids that are already found in geological formations and is known as formation fluid. Unfortunate as it is, wastewater is an integrated part of oil and gas. When crude oil is separated, there is a large amount of water left over (Veil, et al. 2004). This water is toxic and full of heavy minerals such as lead. Due to the nature of the wastewater and drilling techniques, this produced water must be treated (Utvik, et al. 2000).

Produced water is a partially challenging issue because this form of wastewater can have a dangerous compound known as hydrogen sulfide (), which is well known to have the smell of rotten eggs. Hydrogen sulfide is also poisonous, corrosive, and flammable (Airgas SDS), making this compound especially hard to handle and dispose of. Hydrogen sulfide is especially dangerous to humans having a threshold limit value short-term exposure limit (TLV/STEL) of only five parts per million (ppm) (Perry, et al. 2014). Companies use evaporation pounds to treat this wastewater, but oftentimes there is still a need for further purification. Additionally, the evaporation pound can easily pollute both the soil and air.

Thus there is a natural need to reduce the amount of wastewater and treat the produced water more effectively. As technology has quickly become more advanced, it has been shown that Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be used in the treatment of produced water. New developing AIs and machine learning (ML) models could be the future for such an intimidating task as produced water treatment (Koroteev, et al. 2020). Moving forward, the industry is looking to implement computers and robotics to keep humans out of harm’s way in such a risky but necessary industry. Placing these new technologies out in the field will allow humans to understand the normally unseen better. If disaster strikes, a new form of technology could be the reason for mitigation instead of a person put into harm’s way. In the oil and gas industry, there are seasons everywhere in every step of the process that frequently record real-time data (Shah, J. M. et al., 2024). Oftentimes such a large amount of data cannot be processed and iterated by a human. For a computer, however, this is completely possible. ML algorithms have been made the same way a human’s brain works with neural networks. These neural networks can take several inputs and produce a number of outputs. As the number of inputs increases, the size and complexity of the neural network do as well. ML can take inputs, analyze, weigh factors, and then produce an output that is optimum extremely fast (Verma, N. et al., 2024). This allows the operating system to be monitored and changed to be in the most optimum conditions for a longer time. ML allows for a cleaner, more effective process, which saves the industry money and reduces the amount of pollution released into the environment. Therefore, the development of AI and ML would allow for a much faster response and more optimum monitoring of potential risks while keeping humans safer. These new technologies in development would allow for a much cleaner and safer future in a hazardous world.

2. Basis of Machine Learning

A basic machine learning system can be used to recognize or classify certain types of patterns known as a model. A model can be used to answer a question and classify similar things (Aamir, M. et al., 2024). For example, if a model was made to classify whisky from wine. A model could be made given the color and the alcohol content known as features. Using just these two features a model could be made to place the drink into a category. A model is made by a process known as training. In ML the goal of training is to develop an accurate model that can answer the question correctly a majority of the time. To train a model a large amount of data must be given to the system to learn from. The first step of ML is obtaining data; this step is exceptionally vital to developing a superior model. The quality and quantity of the data will directly influence the accuracy of the predictive model (Wang, Z. et al., 2024).

A large number of quality data points will produce a more accurate model than a small number of inferior data points. The next step is data preparation occurs when data is logged into the system and prepared or initialized for use in training. Data is assembled then the order is disbursed randomly to ensure the order does not affect how the model learns. The data is then examined to ensure there are no data imbalances (Astsauri, T. et al., 2024). If more data was collected for whisky than wine, the model could have a large bias toward classifying a drink as a whisky. Data is then split where a majority is used for training, and a smaller amount is used for evaluation. Different data is used in evaluation to prevent the model from remembering the question. It is at this time the model is picked and training can begin. In this simple case, a linear equation can be used, y=m*x+b. Where y is the output, x is the input, m is the slope of the dividing line between whisky and wine, and b is the y-intercept. The only values that can be adjusted or trained are just m and b, because the only true variables that can change the position of the line x, the input, and y, the output, cannot be adjusted (Riquelme-Dominguez, J. M et al., 2024).

In ML, many values form can be formed into a matrix that is often denoted as w for weights. In the same way, a basis matrix can be formed for the b value. The training process starts by initializing random values for the weight matrix and the basis matrix, then attempting to predict the output with the given values; this is known as a generation or training step. In most cases, the first generation does very poorly. To improve upon the first generation, the model prediction is compared with the output that should have been produced and the values in w and b to gain more accuracy in predictions. The process is repeated several times before the model is evaluated. Finally, is parameter tuning to further improve training in any way (Massidda, L. et al., 2024). There are a few values that are assumed to gain a starting point, these parameters are known as hyper-parameters (Zhao, Y. et al., 2024).

One such hyper-parameter is the learning rate; this parameter adjusts the amount line is shifted during each generation based on the information from the previous one. This can massively affect how long it takes to train a model and how accrue the model can be.

3. Wastewater Treatment in Oil and Gas

To produce the massive amounts of energy the current world needs by refining crude oil, it is at the cost of producing by-products, one of which is wastewater (Pichtel, et al. 2016). The raw petroleum from the ground is a mixture of crude oil, formation water (can be brine or freshwater), and undissolved solids such as hydrocarbons (along with other unwanted compounds/heavy metals) (Varjani et al., 2019). However, most of the composition of raw petroleum is water. When raw petroleum is processed, the separated water from petroleum is commonly referred to as produced water.

Produced water is classified as wastewater because it is difficult to treat/dispose of properly. Discharging produced water into the surroundings as a means of disposal presents environmental challenges. It is wastewater because it has been separated from crude oil to produce a finer quality refined oil. The leftover water typically cannot be used for human consumption/use. There is no exact definition for wastewater because wastewater has a complex composition (Pichtel, et al. 2016). However, one can briefly classify wastewater as organic or inorganic.

There are many classifications for wastewater in the oil industry; some examples include refinery wastewater, petroleum refinery wastewater, produced water, petrochemical wastewater (Fadali & Farrag, et al., 2017), and oil refinery waste effluent (Abdelwahab et al., 2009), etc. A few more commonly produced waters in the petroleum industry are described in greater detail.

3.1. Types of Wastewater in the Oil and Gas Industry

3.1.1. Sour Wastewater

In the gas production sector, the water that is commonly encountered is sour wastewater. This kind of wastewater is high in sulfur and acidity concentrations. The acidity comes from the trapped CO2 and H2S gases trapped in the natural gas reservoirs (Olajire, et al. 2020). Sour wastewater is usually dangerous to handle/dispose of because of the elevated levels of H2S which can be dangerous or fatal if inhaled in large quantities. One of the simplest forms of process control safety in the gas industry would be the implementation of the H2S meter.

The meter protects the worker from high concentrations of H2S through the feedback control system in the meter; the meter alerts the worker with an alarm that automatically detects when the concentration of H2S is too high. In addition to increased safety risk, sour wastewater is corrosive to iron pipes, causes equipment failure and high fluid velocity can cause stripping of the iron sulfide layer to expose fresh iron and increase corrosion, leading to high-stress fractures in sections of the pipeline (Hatcher et al., 2014). Although all acidic water comes from produced water, not all produced water is sour. The main contaminants are the increased levels of sulfur and acid in the sour wastewater.

3.1.2. Oily Wastewater

This is produced water that contains high levels of complex organic compounds (especially oily sludge wastewater). Distinct types of groups for organic compounds consist of aliphatic, nitrogen sulfur oxygen (NSO), aromatics, and asphaltene-containing organic compounds. These are usually complex hydrocarbons with these groups that increase the amount of dissolved oxygen. Therefore, discharging oily wastewater to the environment increases oxygen consumption by microorganisms. However, the normal aquatic life that depends on these microorganisms can perish if not enough oxygen is available in the water (Padaki et al., 2015).

The biggest risk for environmental contamination would be heavy molecular weight hydrocarbons. It is especially difficult to treat these undissolved and dissolved organic hydrocarbon chains that have been trapped in reservoirs for millions of years. Because their high molecular weight causes a decrease in their solubility (Neff et al., 1992), discharging treated produced water will always leave behind a small amount of these hydrocarbons dissolved in water, increasing the toxicity to wildlife in proximity. Agricultural soil contamination by oily wastewater decreases plant nutrient production, and the germination of seeds is reduced, leading to less food production in farms near oil wells or wastewater treatment regions (Padaki et al., 2015). Because these organic compounds have a high molecular weight, water absorption is highly limited in oily wastewater-contaminated soil (R. R. Sulemanov et al., 2005).

3.1.3. Produced Water (PW)

Produced water is the formation of water from gas or petroleum reservoirs. This wastewater is typically high in the amount of salt concentration (although, in some cases, the formation water is freshwater). Some samples of offshore-produced water contained over 300% of the normal sodium chloride concentration found in seawater. Produced water from offshore wells can have just as high or higher salt concentration compared to the produced water gathered from petroleum wells on land. In addition to increased salt concentration, produced water, like sour and oily wastewater, can contain the contaminants in these types of wastewater, but with ranging concentrations (Neff et al., 1992).

Offshore well-produced water can also contain large organic carbon concentrations from the hydrocarbons trapped in the oil reservoirs. More contaminants present in the hydrocarbon chains are functional groups from organic acids/aromatic ring structures. Metals, too, are present in the extraction of raw petroleum, but depending on geographical age and location will determine what type of chemical species will be in the produced water (Hur et al., 2018).

3.2. Petroleum Wastewater Treatment Methods

After the raw petroleum is processed into refined oil (which can then be converted into other oil products, like gasoline, plastics, lubricants, etc.), most of what remains is water leftover from petroleum processing and can be further treated for recycled use. The composition of crude oil depends on the geographical location where the oil was extracted (Hur et al., 2018). Oil companies typically want water composition in refined oil to be less than 1%. The process of treating wastewater is quite complicated, but if the entire treatment is separated into sections, it becomes simpler to understand. Heavy water treatment is needed to safely reuse the water produced from the oil wells and refineries (Varjani et al., 2019).

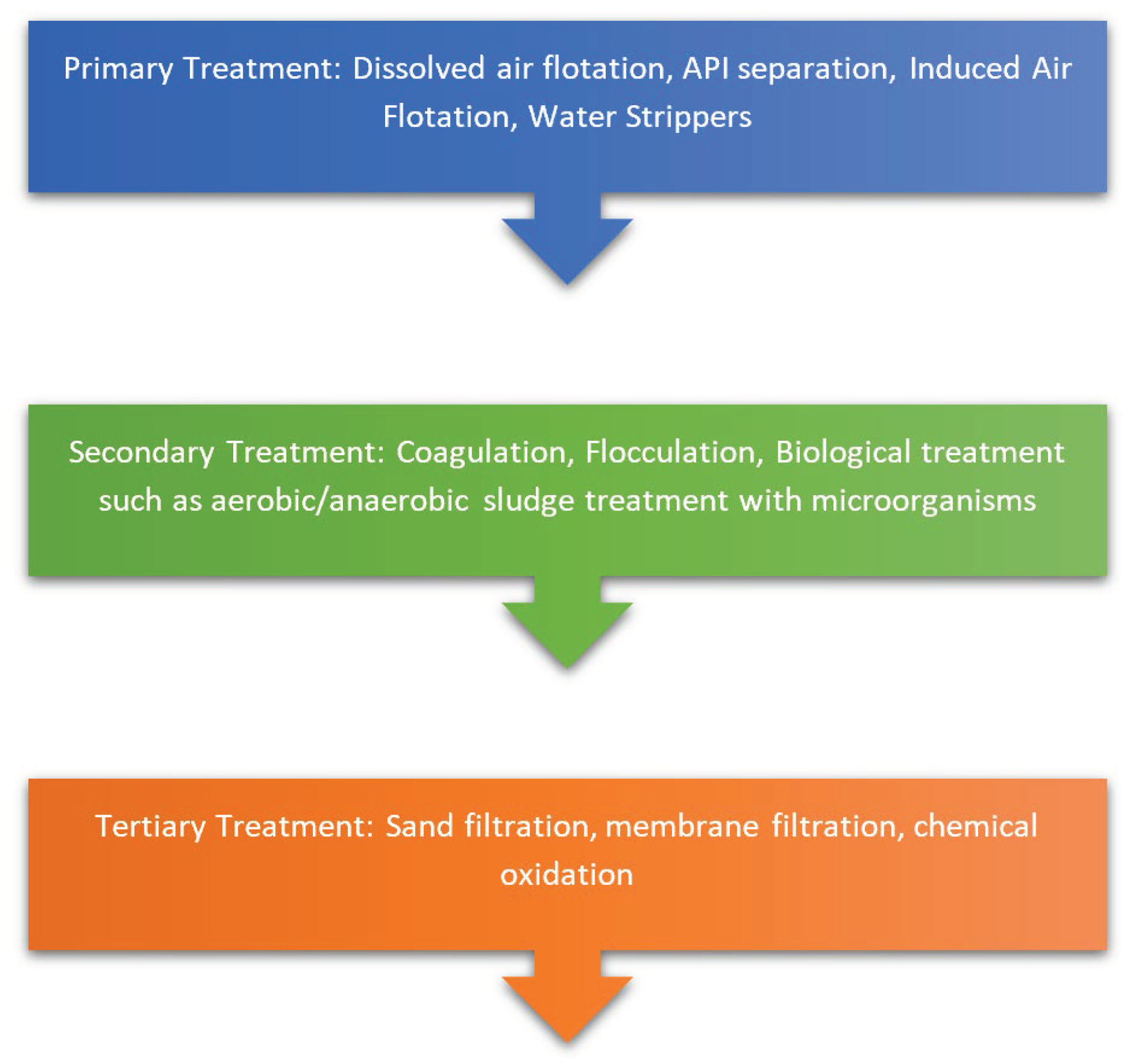

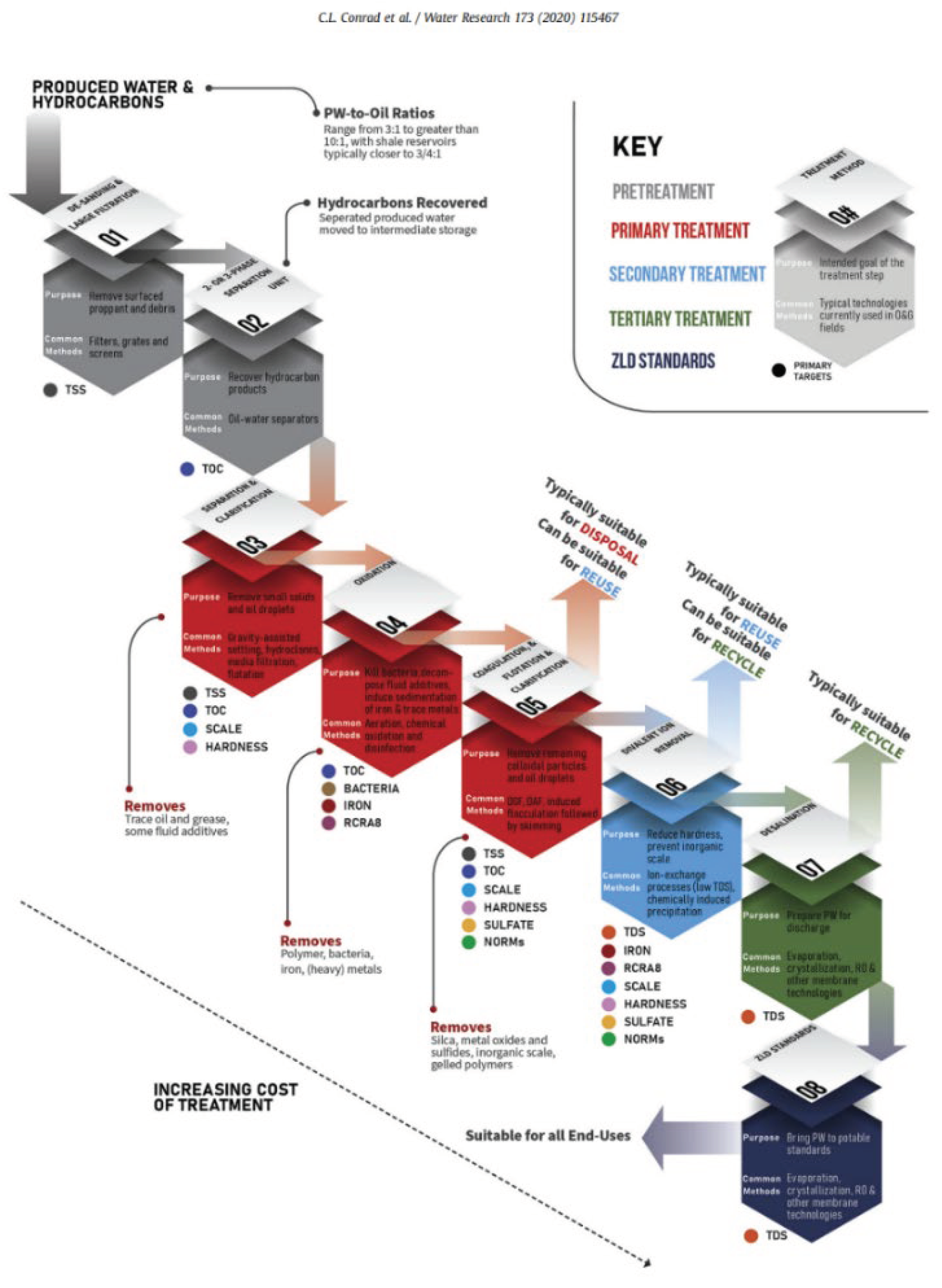

A general flowchart for treating petroleum wastewater is shown in

Figure 1:

On a review of wastewater treatment processes,

Table 1 shows different physicochemical wastewater types and their respective treatments and brief results from several researchers. A few processes were chosen to see if A.I./Machine Learning could be used to improve gas/oil production for this study.

3.3. Wastewater Treatment Methods

3.3.1. Evaporation Ponds

Depending on the type of wastewater, it is common practice as a form of wastewater treatment to store petroleum wastewater in large ponds, commonly referred to as evaporation ponds. The water can either be evaporated without any other intervention, or the addition of bacteria can further purify the water to a certain acceptable extent. However, this treated water can still be possibly toxic with brine and other unwanted compounds (Ahmed et al., 2000), but after controlled treatment can be reused for other treatments such as crop irrigation (Pichtel, et al. 2016).

Evaporation ponds are typically developed in arid regions where evaporation rates are substantially greater. However, evaporation ponds are one of the cheapest methods for treating heavy brine-produced water compared to desalination plants (Ahmed et al., 2000). Companies need to be cautious as the water from these ponds can be hazardous to health and pollute the soil in the event that the pond collapses/overflows. In an event where an evaporation pond fails (for example, a thunderstorm causing an overflow), the accumulated water that has spilled over contaminates the soil (Pichtel, 2016).

3.3.2. Removal of Naphthenic Acids and Aromatic Naphthenic Acids

In a wastewater treatment plant in North China, a study was done to analyze the effectiveness of physicochemical treatments in petroleum wastewater by removing naphthenic acids (N.A.s) and aromatic N.A.s. The removal of N.A.s was done by treating the water by processes of gravity setting through a designated chamber, a coagulating chamber, filtration through walnut shells, flotation, and aerobic/anaerobic. The composition of N.A.s in the wastewater varied from 2.1-8.8%. An interesting finding is that the removal efficiencies for total N.A.s and aromatic N.A.s were much better in the summer than in the winter after biodegradation, with removal efficiency of 73% and 53%, respectively (Wang et al., 2015).

Unfortunately, there is no mention of A.I./M.L. in this wastewater treatment plant. However, they could have had an A.I./M.L. system that could have contributed to the separation of N.A.s, such as a fuzzy neural network or a different A.I./M.L. process control system.

3.3.3. Membrane Technology

One of the most effective wastewater treatment methods is the implementation of membrane-separation technology. Membrane technology can vary from filtering water to filtering the very blood from one’s body through dialysis. From the point of petroleum wastewater treatment, the wastewater membrane separation processes rely on absorption, sieving, and electrostatic phenomena. Membrane separation technology is especially effective at treating oily wastewater through microfiltration, and nanofiltration, but the most effective method is ultrafiltration (Padaki et al., 2015). Several types of membrane separation materials include organic and inorganic materials such as polymer and ceramic membranes, respectively. The advantage of using membrane technology is that it works without additional chemicals to aid in separation.

4. A.I and Machine Learning Wastewater Treatment

4.1. Implementing the AI and ML to the Wastewater Treatment

According to the USGS.gov, the Earth is made of 71 percent water. We need water for drinking, eating, and transportation. Furthermore, water is the home of about 1.4 to 1.6 million species making it a priority to keep it clean. In water treatment, pollutants such as dyes, heavy metals, and organic compounds can be removed AI’s implementation. AI technologies (Zhiping, Xin, Jining, and Jaide, 2018). In addition to wastewater treatment, different AI technologies have been implemented to control the disposal of wastewater. Technologies like the Radial Basic function network, Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network, Scalable Vector Graphic, Genetic Algorithm, and Feedforward Neural Network have been implemented for wastewater treatment (Zhiping, Xin, Jining, and Jaide, 2018).

The efficiency of these machine languages and AI have been tested through numerous experiments. The removal of dyes has been experimentally tested using the Artificial neural network coupled with a genetic algorithm known as GA-ANN. Some setbacks like time-wasting during computations using GA-ANN. However, GA-ANN is highly fast and accurate when giving results. AI and machine learning have also been implemented to remove heavy metals. One of the most famous experiments done was the use of MLPNN and ANFIS for the adsorption of copper (Nag, Mondal, Roy, Bar, and Das, 2018). MLPNN and ANFIS are accurate and are exceptionally good for value estimation. The only issue with these two AI is that they are error-prone, which is not good for results that need to be precise and accurate.

4.2. AI and Machine Languages Implemented

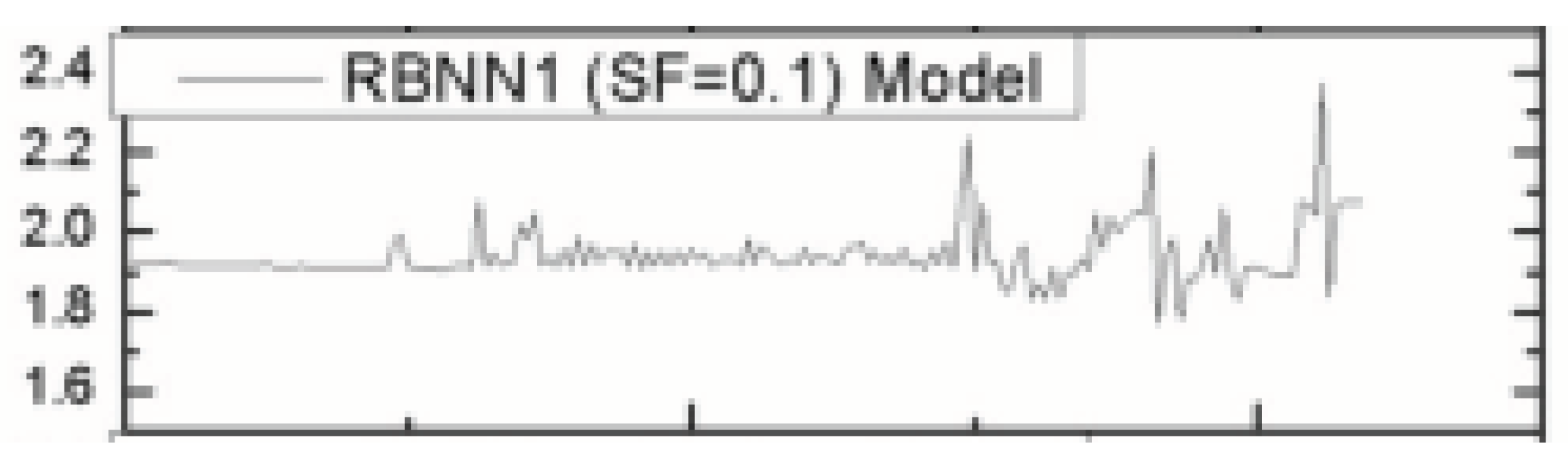

4.2.1. Radial Basis Function Neural (RBFNN)

RBFNN is an algorithm language with three main layers: input, hidden, and output. In the case of water treatment, we use RBFNN for heavy metals. The RBFNN detects the metals by making accurate predictions for each metal (

Nag, Mondal, Roy, Bar, and Das, 2018). Also, RBFNN has been implemented in the modeling of coagulants in water treatment. The RBFNN was used to measure the dosage of coagulants. The coagulant dosage rate is non-linear due to conductivity, turbidity, and pH. The conductivity, turbidity, and pH of the coagulant make the coagulation process difficult to control. That is why the RBFNN is implemented in this process to measure the coagulation and the coagulant dosage.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 below show the observed and predicted chlorine dosage as the number of samples increases (

Nag, A. et al. 2018).

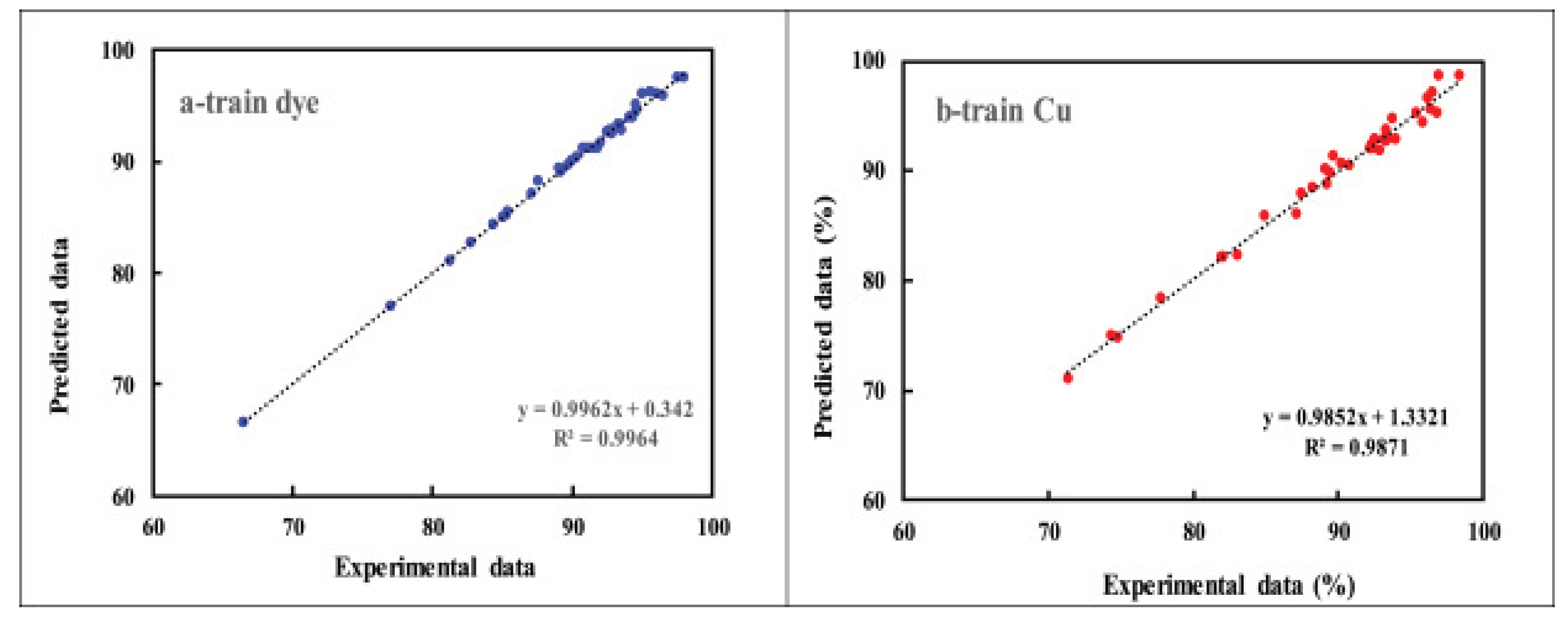

4.2.2. Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN)

The Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network is a very efficient algorithm with a fully accurate estimation and forecasting technique. This algorithm is mostly used in weather forecasting, but it can also be applied in water treatment for making coagulants that can be put in water making it drinkable. The Basic Read 46(BR46) and Cu adsorption from an aqueous solution experiment is a good application of this (Nasiri, S., et al., 2017).

This investigation was based on removing copper, which is a heavy metal, through adsorption by combining it with a scale reactor. The input parameters were pH, concentration, time of contact, adsorbent dosage, and Initial BR46 (Basic Read 46) and Copper (II). The neural networks applied were MLPNN and ANFIS. The parameters used were dye, Copper (II), contact time, pH, and adsorbent dosage. By using sawdust from Melia Azedarach Wood, the MLPNN ANFIS model was used to give an accurate prediction model of dye and copper (II). The training dataset, validation datasets, testing datasets, and

R2 values were respectively 38, 6, 6, and 0.99 (

Figure 4)(

Nasiri, S., et al., 2017).

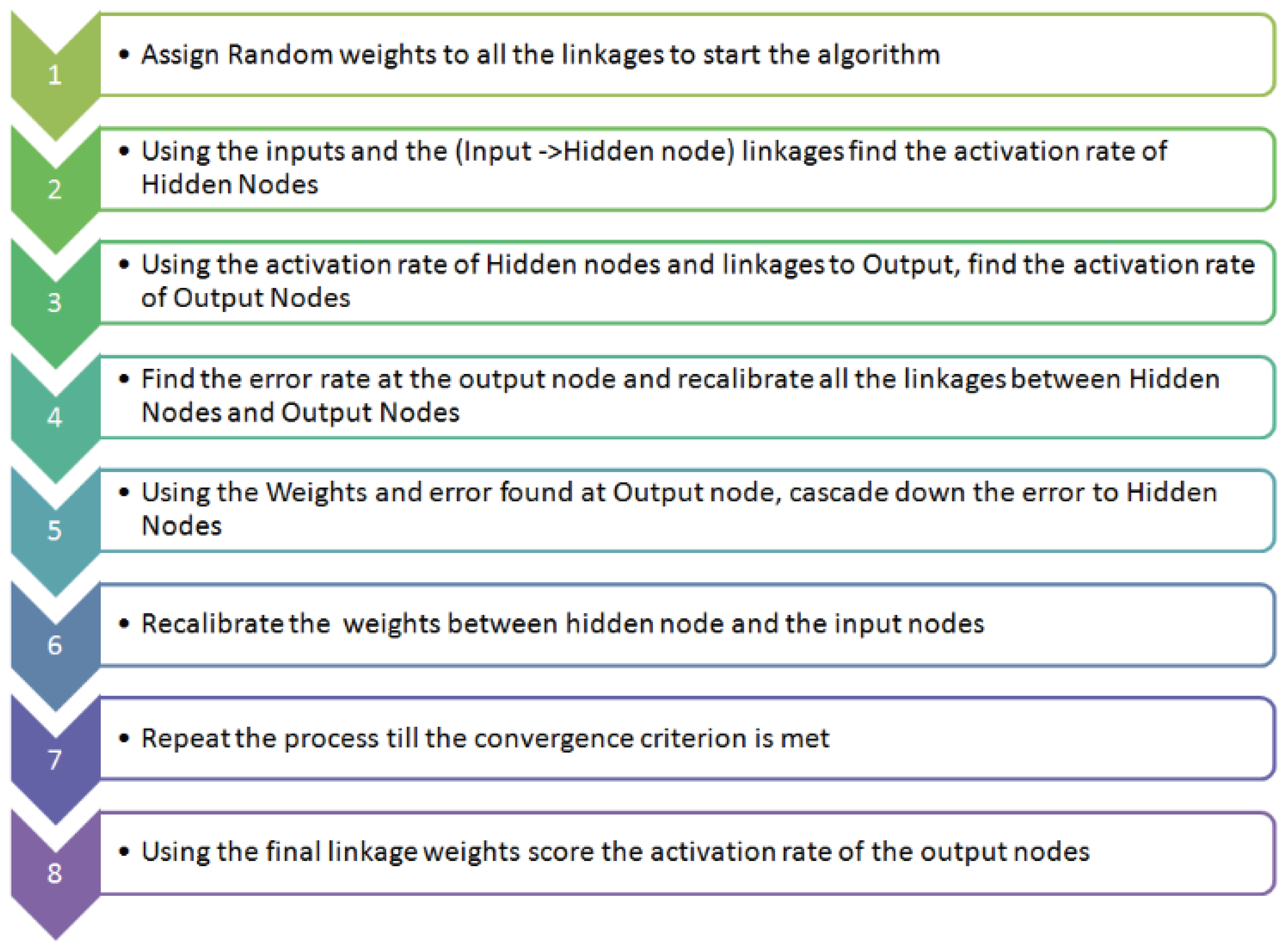

5. Artificial Neural Network Coupled with Genetic Algorithm (GA-ANN)

This neural network is very promising because its high speed and accurate prediction can be used in various applications. ANN network helps us to understand datasets in both ascending and descending order. Furthermore, the ANN network can help us identify the model which has the best fit and it changes based on the environment it is put into(Tavish, 2014). Figure 5 indicates the various stages the ANN neural network goes through in processing data.

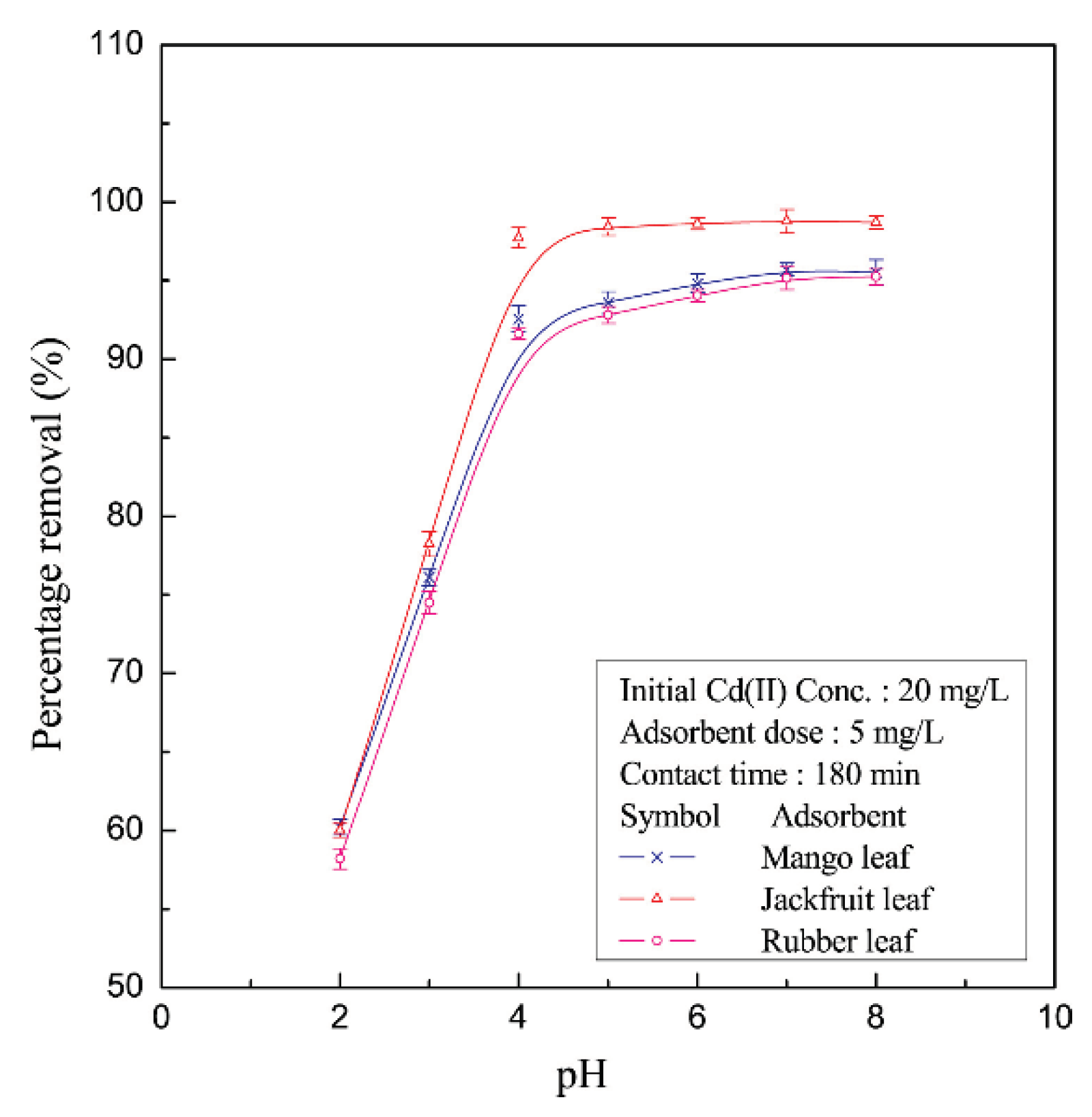

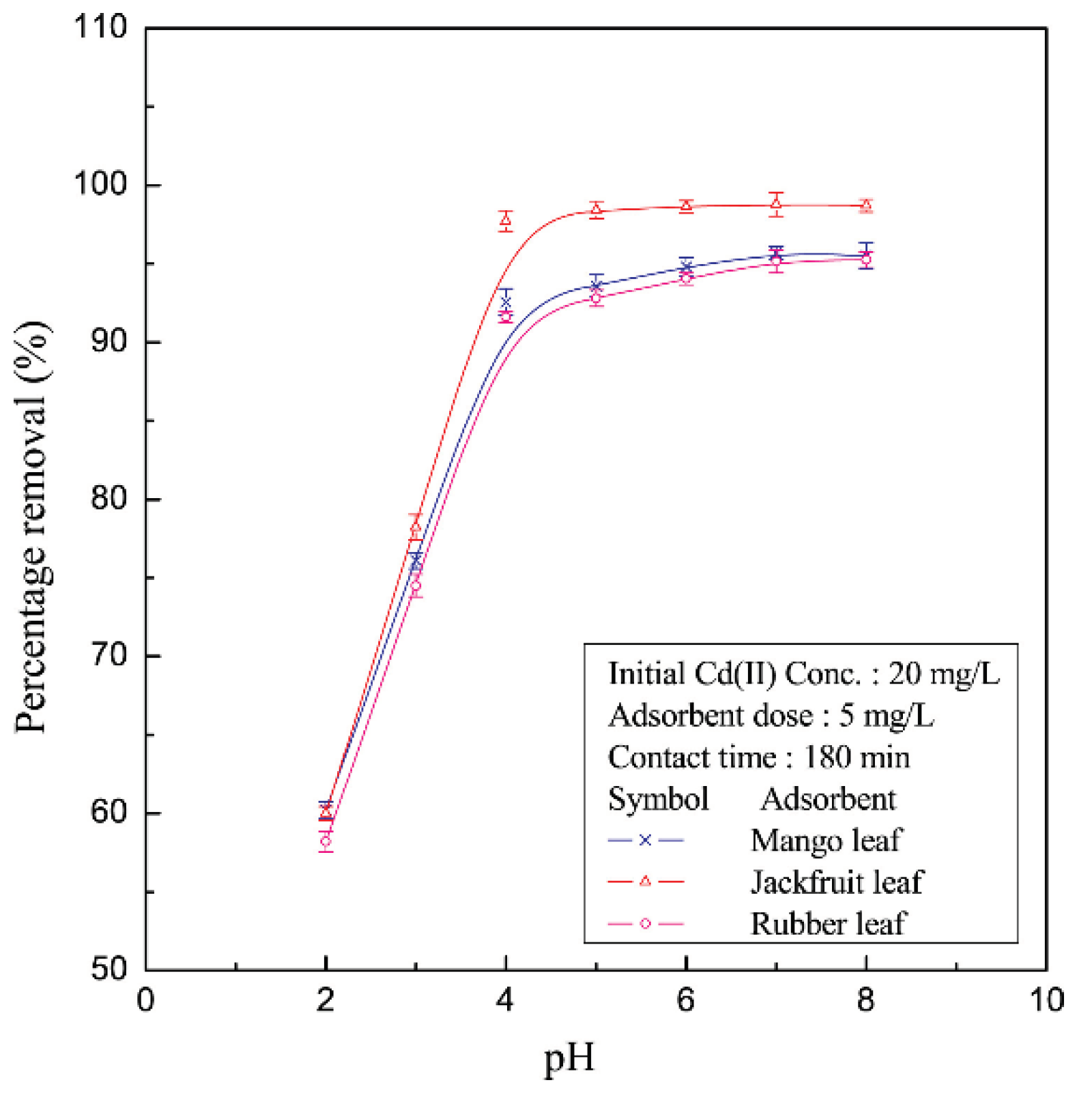

For example, in an experiment involving the Bioremediation of Cadmium (II) from an aqueous solution using waste materials, the GA-ANN was used to model a complex sorption process which was used to predict the efficiency of the metal ion removal (

Nag, et al., 2018). The training dataset, validation datasets, testing datasets, and

values were respectively 65, 19, 9, and 0.94. The

R2 values obtained showed how efficient the GA-ANN is in predicting heavy metals (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7)(

Nag, et al., 2018).

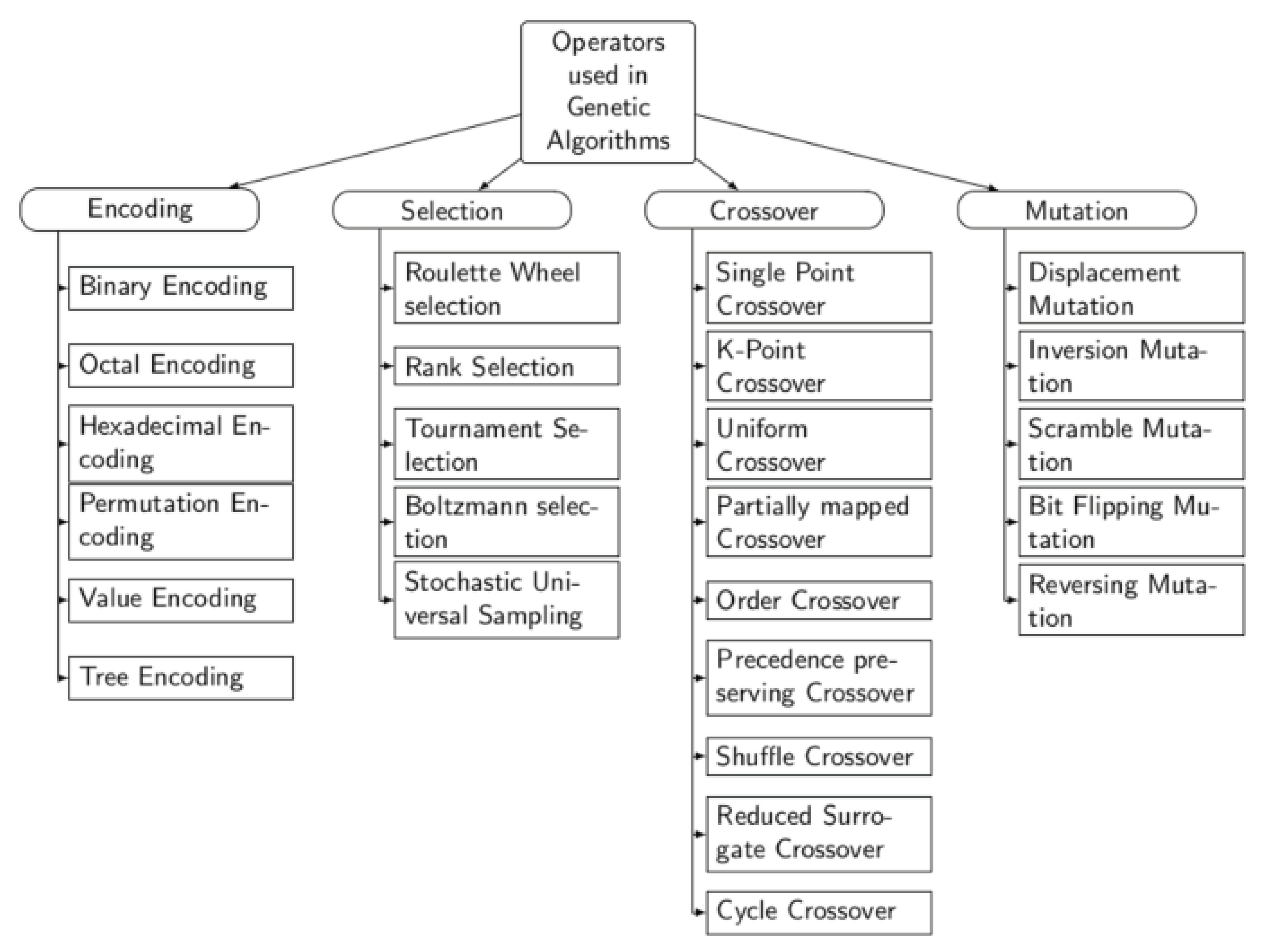

6. Genetic Algorithm (GA)

A genetic algorithm is one of the first built algorithms for counting the population, it applies the principle of Genetics and Natural section for searching (Mirjalil, et al., 2019). The evolutionary biology technique improves the parameters which gives it an extremely high estimation power and can be used to optimize (Mirjalil, 2019). The genetic algorithm is made up of various operators which are encoding, crossover, selection, and mutation. All these operators have various subunits that help in algorithm processing as can be seen in Figure 8 (Katoch, et al., 2021)

.

6.1. Al Currently in the OGI

Entering a new era of technologies, the implementation of AI is critical for the oil and gas industry to continue to advance. The Internet of Things (IoT) describes a physical object with sensors that collect data and exchange that data with other software and systems (Wanasinghe et al., 2020). IoT applications include wearable watches, smart helmets, and smart glasses to be worn by oil field engineering for safety purposes, communication, and assistance in the oil and gas industry. Drones and robots are used to inspect potential hazardous leakages in pipelines, flare emissions, offshore drilling, inspections, and disaster control to improve efficiency and personnel safety (Ivanov et al., 2018). Smart pipelines are utilized for detecting damages and notifying the control room immediately. Micro and nanotechnologies are commonly implemented to give more accurate and in-depth data. As part of IoT, wireless sensors monitor and oversee operations such as pipeline leakage, rust, and instrumentation in real time (Rahmati et al., 2017).

Radiofrequency identification (RFID) technology is applied to the oil and gas industry for asset and oil rig management, inspections, safety, and security. However, the large amount of data that the sensors collect is often too difficult for human interpretation, so the data is filtered through intelligent systems (Aldhaeebi et al., 2014). Machine learning (ML) in the oil and gas industry aims to analyze and interpret the data to make predictions. ML is useful for drilling objectives, identifying, overseeing, and forecasting so optimization can be determined in real-time at a low cost.

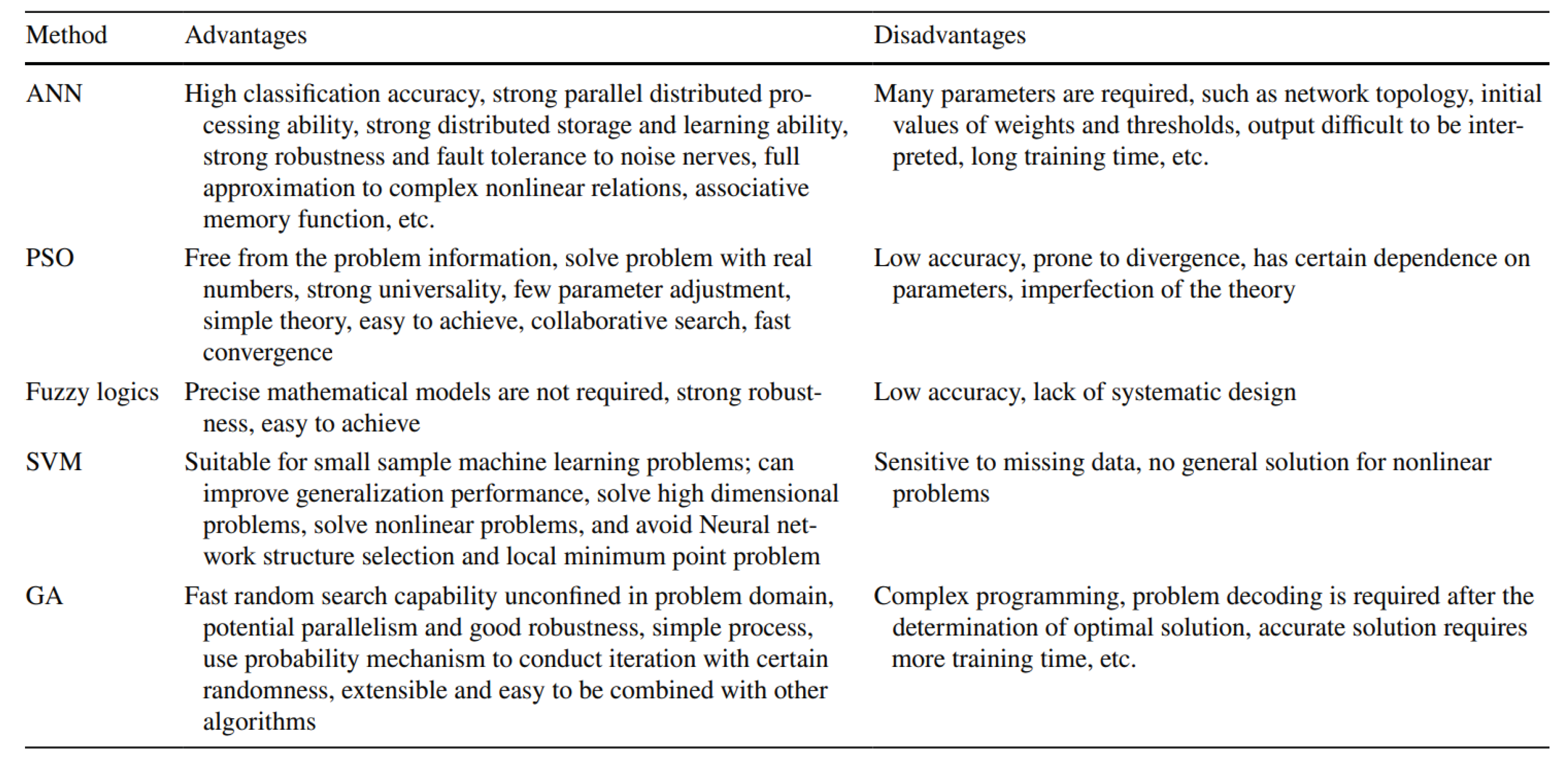

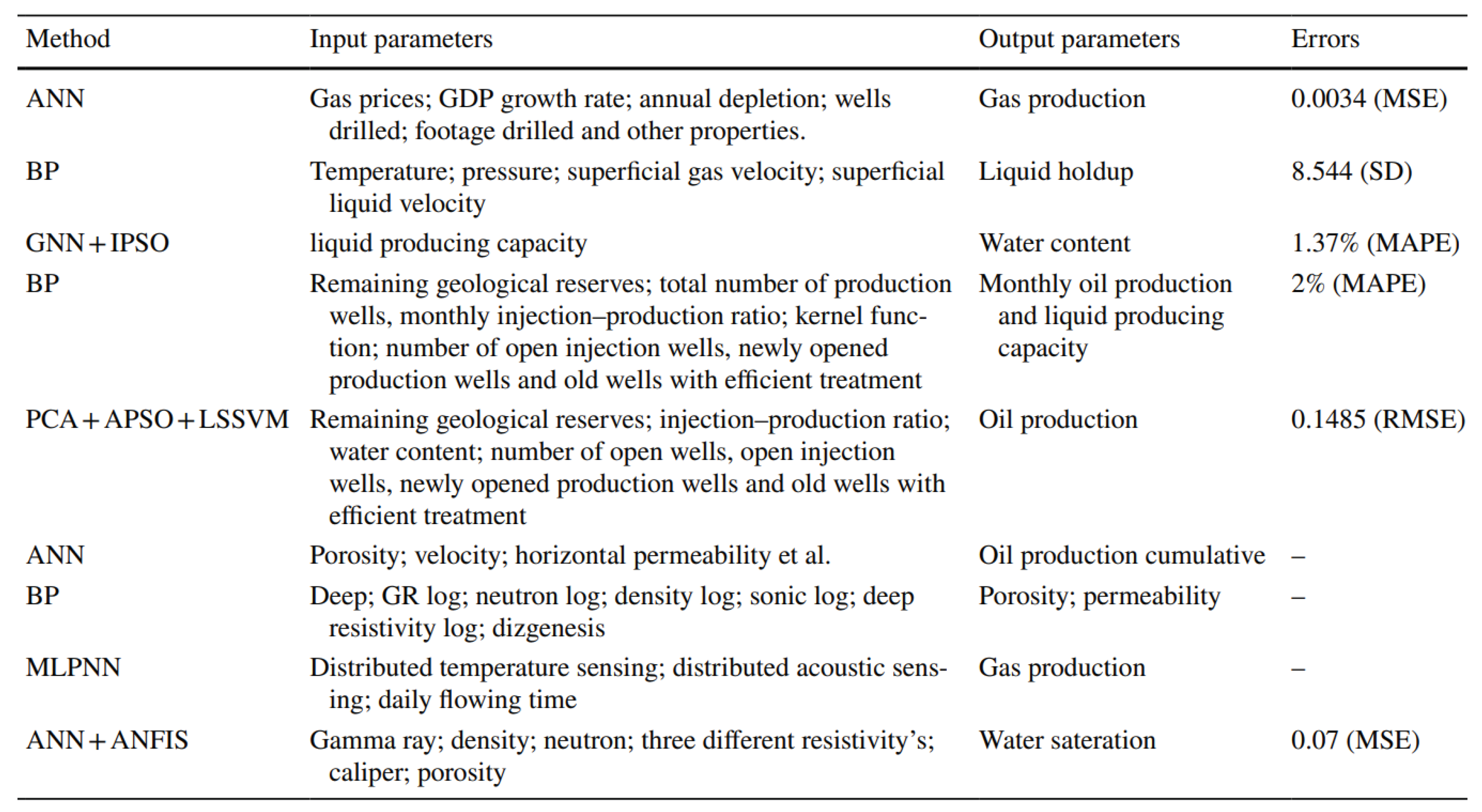

The most common and simplest algorithm used is Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) which has high input parameter requirements in order to operate (

Table 2) (

El-Abbasy et al. 2014). Supper Vector Machine (SVM) is useful for small-scale instruction and not very suitable for real data (

Anifowose et a. 2012). Particle swarm operation (PSO) can disregard the problem information, but the accuracy is low. Fuzzy logic does not need a specific mathematical model but is not very accurate. Deep learning (DL) and Genetic Algorithms (GA) are often combined to improve the accuracy of other ML algorithms; however, GA is complex and requires more programming (

Romero et al. 2000). BP neural networks are the most frequent and utilized AI in the oil and gas industry. Overall, choosing a suitable algorithm combination according to the advantages and disadvantages is important. If correctly implemented, the oil and gas industry can perform better at higher speeds (

Windarto et al., 2017).

Al can be employed in the oil and gas industry for dynamic production predictions, development plan optimization, identification of oilfield development, fracture detection, oilfield diagnosis, and enhanced oilfield recovery (Li et al., 2021).

Predictions using AI are some of the fundamental necessities in reservoir engineering and oilfield development. Dynamic predictions are often used to give optimum predictions. The most common method is to combine neural networks with fuzzy logic to obtain optimal accuracy of the production data (Anifowose et al., 2011).

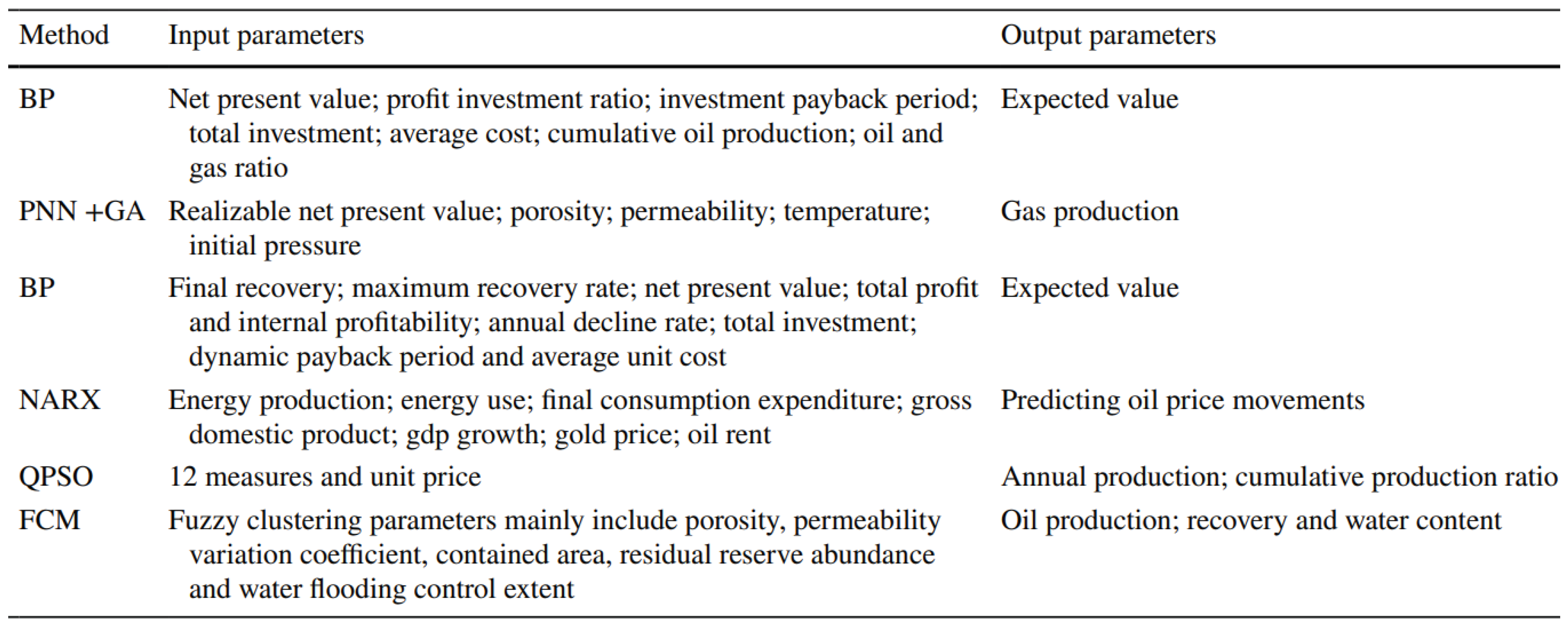

In

Table 3, the AI applied to the oilfield development is primarily focused on fluids and water content rather than oil processing speed. However, the combination of AI algorithms has the potential to make dynamic predictions based on the desired result, and there may be a need to perform with many algorithms at once (

Li et al., 2021).

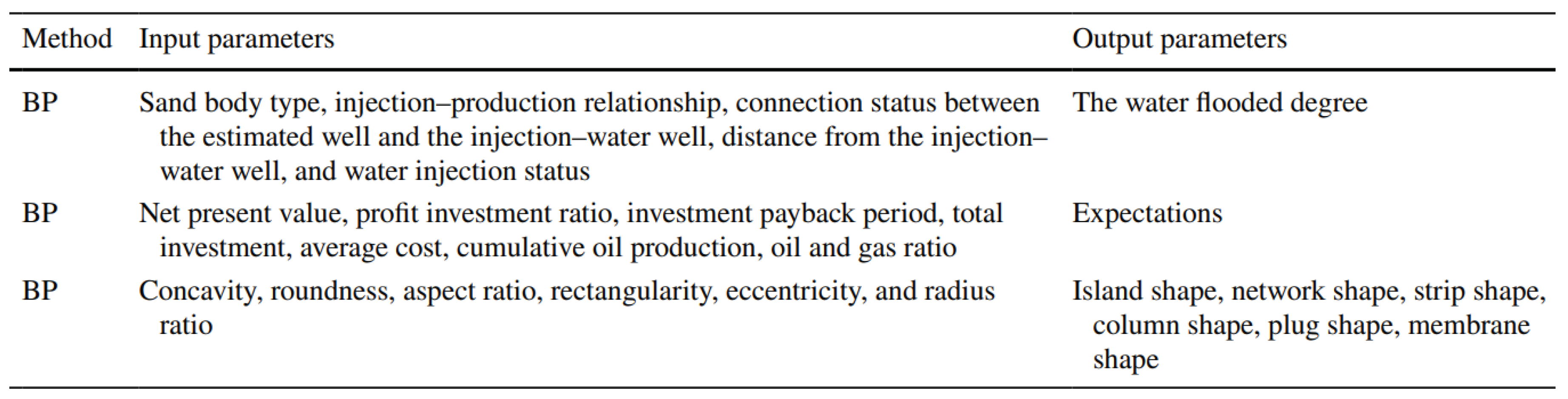

A developing plan for the oilfield development is critical due to the complications involved with the processing. Optimization using AI is mainly applied to improve production considering economic components. The input parameters often widely vary, so adaptable algorithms are used to compensate (Aung et al., 2020).

Below in

Table 4, plan optimization using different AI algorithms is shown. The most customary algorithms used are ANN and GA A standard AI system should be utilized for a multi-dimensional study in oilfield development planning.

Identifying residual oil is a principal matter in oil and gas development. However, before applying the recommended methods in

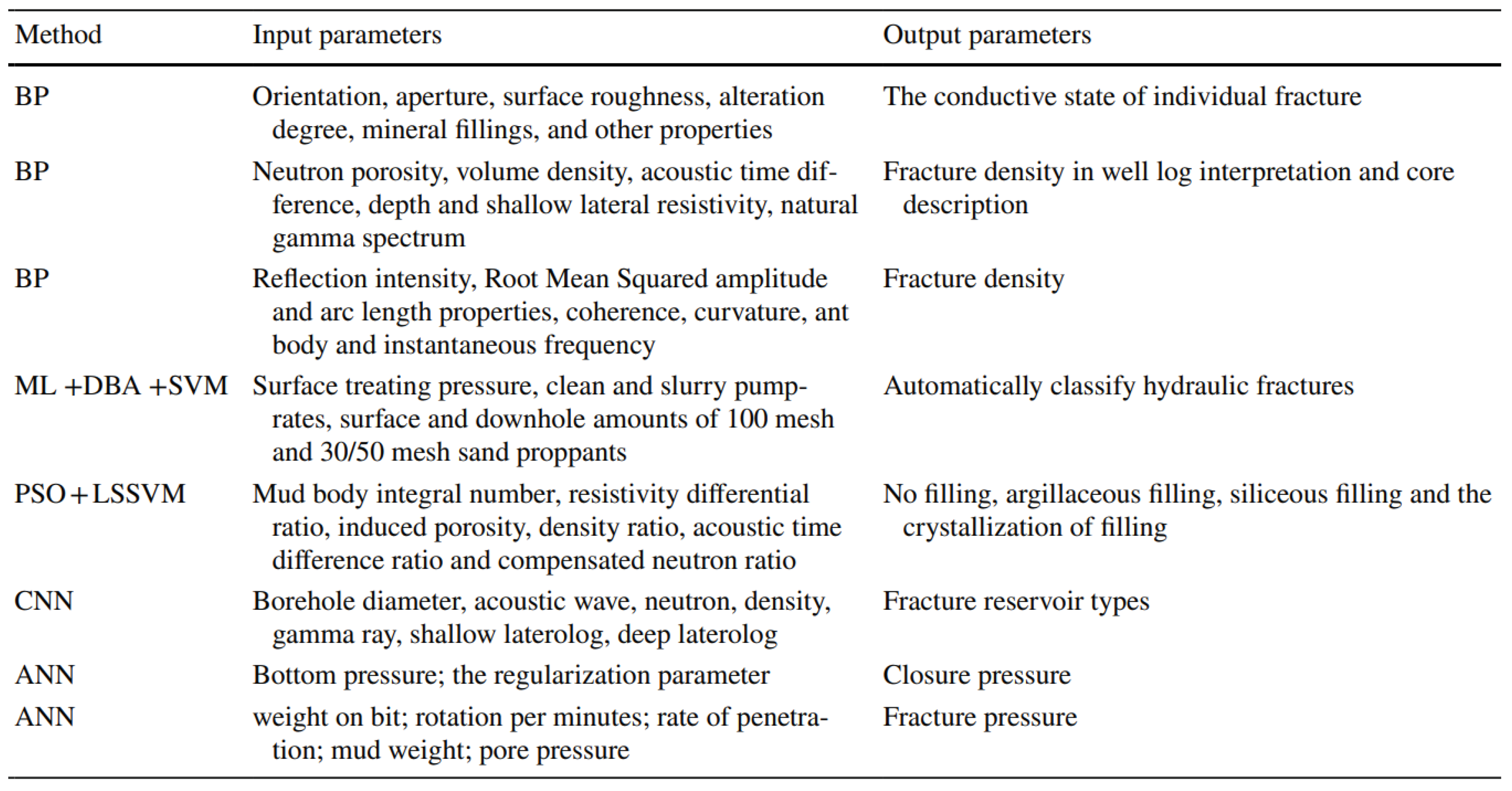

Table 5, more research should be conducted considering the possible applications of other methods applied in other fields, such as rapid identification.

Surface structure, property features, and the categorization of fracture are often studied to detect fractures in the oil and gas industry. It is often a complicated process, and implementing AI is a reliable and easy method. In

Table 6, some recommendations for AI are used for fracture detection. The identification accuracy may increase by combining the seismic and logging data and the AI algorithm to attain dynamic identification.

7. How AI/ML Can Be Used to Treat Oil and Gas Wastewater/Produced Water

AI is a tool with expanding uses in many industries to help solve and optimize problems using human-like capabilities. Water is a precious resource on Earth. While abundant most of it is unusable without treatment. AI, specifically artificial neural networks (ANN), can be used as a regression model, and genetic algorithms (GA) as a global optimization technique, have been implemented in multi-purpose applications for the desalinization and treatment of water (Aani, Bonny, Hasan, Hilal 2019). AI has proven to be a reliable tool in handling complex and difficult problems, especially when it comes to optimization modeling. ANN is considered a black box model because of its ability to model any given process without the need for extensive knowledge (Aani, Bonny, Hasan, Hilal 2019).

Essentially numerical equations and detailed information assuming characteristics that help describe the fundamental engineering principles at play are not required for ANN to successfully model the process accurately (Aani, Bonny, Hasan, Hilal 2019). GA essentially evaluates all possible solutions for the given engineering or science-based problem by developing a Pareto set that gives the optimum global point and all possible solutions. This technique compares favorably for water desalination to traditional approaches that seek to guess a solution than search for a direction based on the pre-determined transitional rule (Aani, Bonny, Hasan, Hilal). Feedforward ANN has been applied extensively to membrane processes to overcome the flux drop that occurs in these processes with tremendous success compared to traditional modeling methods such as pore blocking and modeling water permeability for reverse osmosis systems. ANN’s overall have shown an ability to predict consistently and accurately model different desalination technologies compared to traditional approaches. GA has been applied to optimizing desalination processes to increase the production rate with great success (Aani, et al., 2019).

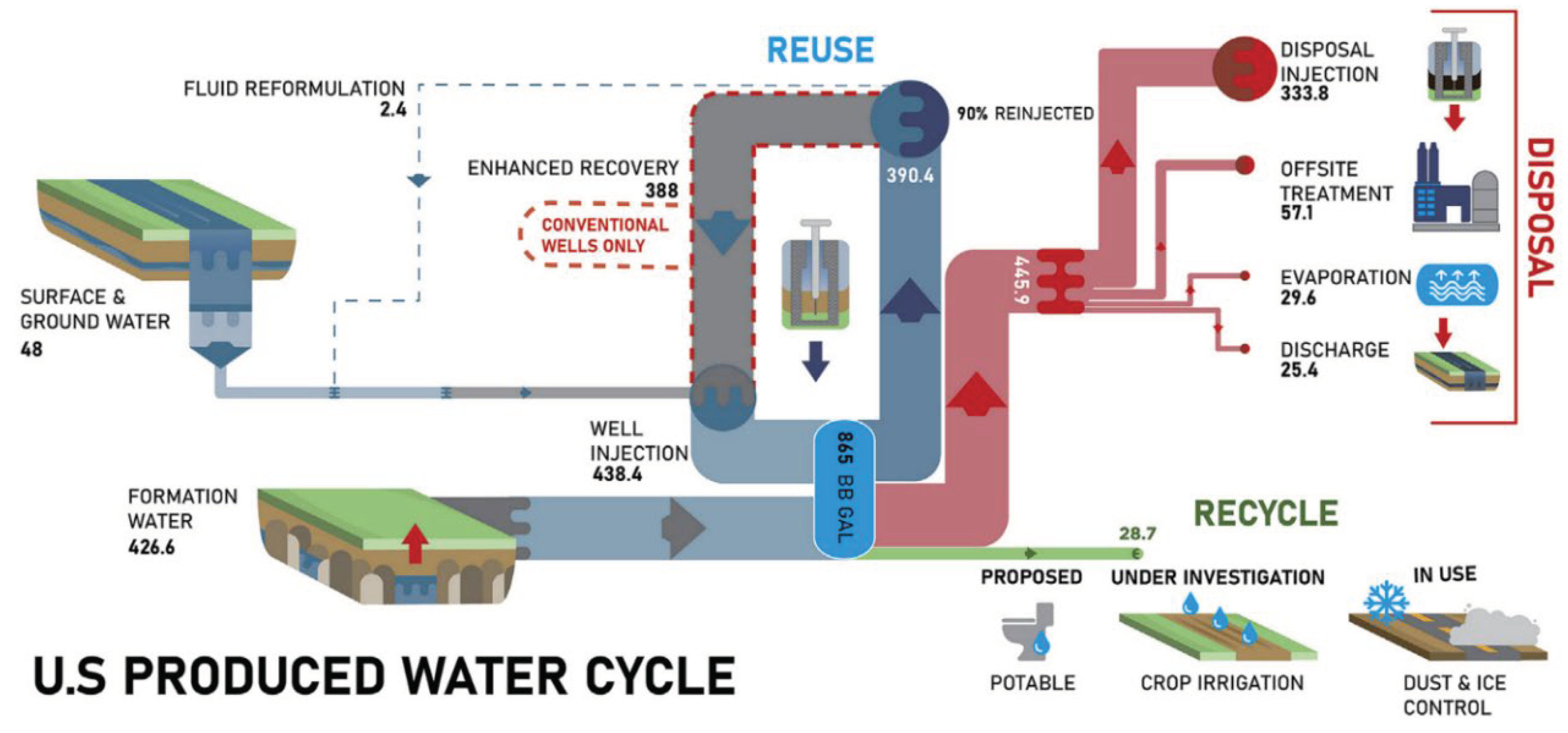

The Oil and Gas industry is heavily reliant on water throughout many of its processes and could greatly benefit from the growing use of AI/ML. Hydraulic Fracturing (HF), commonly referred to as fracking, is currently the biggest contributor to the shale gas boom. HF requires 4-6 million gallons of water per well (15,000-23,000 m

3/well) pumped below the surface to free trapped hydrocarbons from shale formations (Conrad, Yin, Hanna 2020). The size and scope of this water usage and subsequent wastewater/processed water (PW) treatment would suggest favorable outcomes from the use of AI optimization. The amount of water treatment needed from the wastewater associated with HF depends on many factors, such as the starting point of the water and the intended use of the treated water. There is no shortage of water from reuse/recycling in HF, such as agricultural uses like water for non-consumption plants and even human consumption.

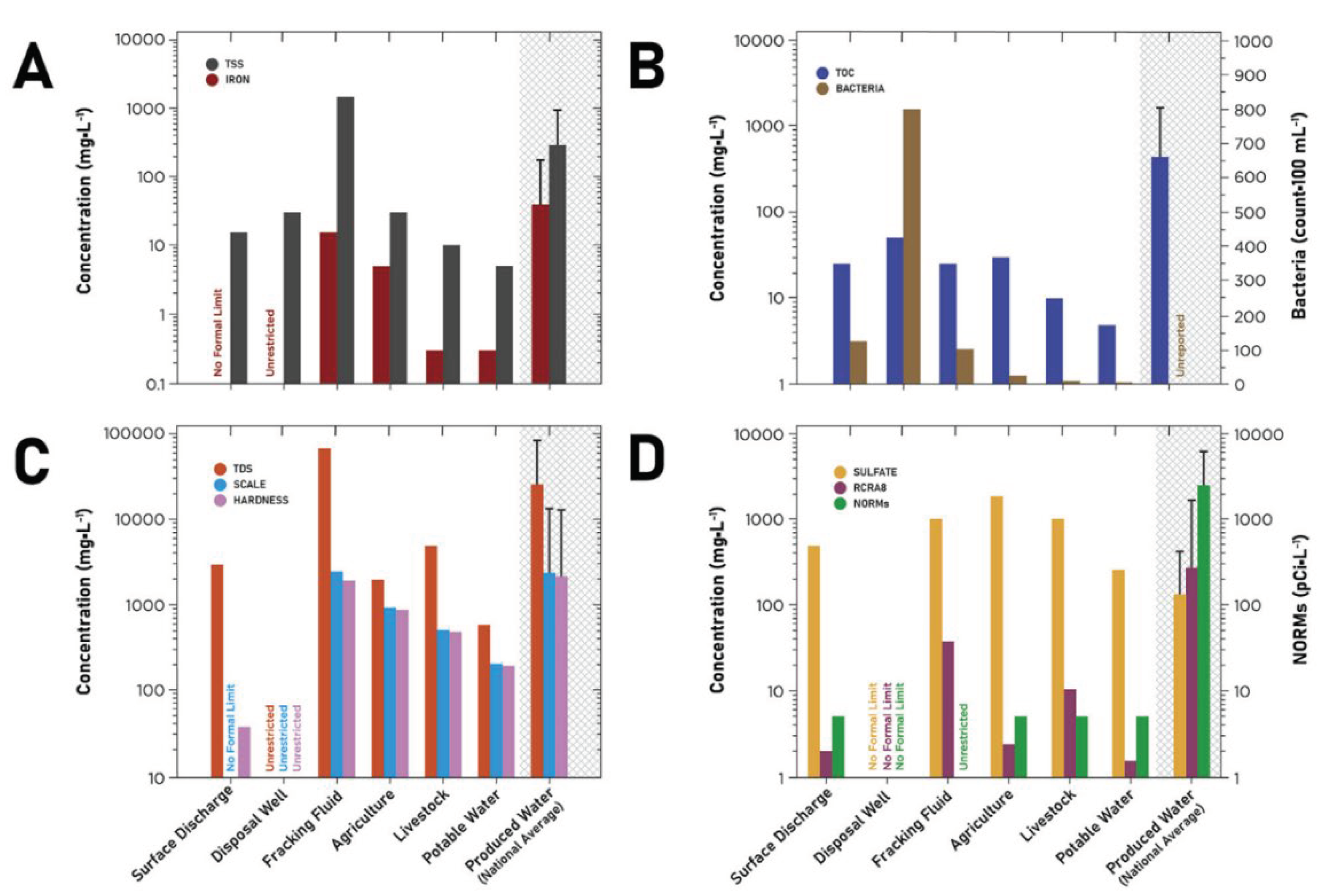

Figure 9 illustrates a simple overview of US-produced water (Conrad, et al., 2020).

Regulatory and environmental factors play a big role in treating wastewater and PW, but ultimately, cost efficiency dictates which treatments are possible. Ideally, the wastewater is treated to the exact point that is needed for its intended use and not overtreated. Any additional treatment past that point would be an unnecessary waste of money and resources; water treated too much (to the point of distilled) would be detrimental to water non-consumption plants. Currently, the cost to take the wastewater from HF and treat it until it is safe for human consumption on such a massive scale is not cost-efficient or feasible for various reasons. However, non-consumption agricultural applications represent a big opportunity, with the cost of treating the water still being the biggest hurdle. HF water process contains five stages: acquisition, fluid mixing, injection, Incidental release of produced water from HF (U-PW) handling, and end-use application.

Figure 10 represents the various stages and subsequent water quality after each treatment stage.

Figure 11 contains a graphical representation of the contaminants found after water treatment (Conrad, et al. 2020).

When treating HF wastewater or PW the total dissolved solids and salinity are key factors in determining which treatments are viable and how many treatments are required. When reuse is the wastewater’s intended goal, the treatment focuses on reducing solids, residual oil and grease, iron, and certain chemical additives; repurposing desalination is usually the focus (Conrad, et al. 2020). The current technologies used for treatment are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary treatment (Conrad, et al. 2020).

Primary treatment removes solids, residual oil/grease, iron, HF fluid, and bacteria. Secondary treatment removes ions that can negatively affect the HF process when the wastewater or produced water is reused. Tertiary treatment is the process of removing salts using desalination. Desalination costs are the biggest hurdle limiting the options for wastewater use. Currently, it is more attractive to dispose of wastewater or reuse it to avoid additional treatment and the costs associated with desalination (Conrad, et al. 2020).

Wastewater exceeding 100,000 mg/L TDS is especially difficult to treat cost-effectively, with membrane technology being cited as the best option. However, hurdles such as membrane fouling and membrane degradation limit this as a viable option (Conrad et al. 2018). The recent advances in AI/ML could potentially bridge the technological gap between these processes. AI, such as ANN and GA, has improved and optimized desalination in water treatment. ANN specifically continues to see a huge improvement and uses in the membrane water treatment sector. Using predictive feedforward ANN or GA to optimize the process control of wastewater/P.W. treatment for reuse or ideally repurposing could reduce the cost of the process to the point that is not just environmentally appealing but economically the best route for a company (Conrad, et al. 2018, Zhang, et al. 2019).

There is always a demand for processed water, and as AI continues to develop, water treatment should become more economically attractive. As AI technology becomes more mainstream, the number of applications for AI technology is expected to increase and become more cost-effective. There is then the opportunity to shift the narrative of the wastewater/P.W. industry. AI is expected to continue advancing in its ability to optimize and cost-effectively manage the process controls of wastewater/P.W. and the opportunity to expand into the oil and gas industry, specifically in the field of HF is enormous. (Grace, et al. 2018 Conrad, et al. 2020).

8. Conclusions and Future Works

This review paper looked at wastewater in the oil and gas industry and AI/ML applications in water treatment and their applications in the oil and gas industry. With increasing environmental constraints in the oil and gas industry, recycling water for reuse plays a major role in the future. However, the biggest hurdle for reusing wastewater is the cost of treatment. With recent advancements in AI/ML, especially in water treatment, these costs could be reduced through AI/ML optimization. Wastewater in oil and gas has no exact definition because the nature of the wastewater varies greatly due to many factors such as location; because of this, accurately treating wastewater to the exact desired point for the intended use can be costly and difficult. Certain AI process controls like feedforward ANN have been proven to treat water successfully and efficiently and, therefore, could have direct applications in treating oil and gas wastewater. Millions of gallons of water are used for HF and pulled from the ground in oil and gas, presenting a great opportunity to find ways for this water to be useful and cost-effective on a large scale. AI/ML is used in the oil and gas field to help with optimization for things like production and predictive patterns. There is an opportunity to expand the use of AI/ML into the wastewater treatment sector of oil and gas as the cost and efficiency of this technology improve and the need to reuse wastewater necessitates a shift in how wastewater is handled. The overall goal of expanding AI/ML in produced water/PW treatment is to make the reuse of produced water through treatment cost-effective.

Determining the costs associated with each viable AI/ML process for treating wastewater would be needed to determine which process and strategies to implement for the given wastewater. This initial investment could then be compared to the current methods/costs, analyzed based on the expected improvement of the AI/ML process, and used to determine expected cost efficiency between the current methods versus optimization using AI/ML. Additionally, a study showing the quality and efficiency of each AI/ML process with varying wastewater would allow the industries to determine which AI/ML process they should invest in based on the expected wastewater/PW makeup. With both studies, a critical analysis could and a general conclusion can be drawn on the strengths and weaknesses of the various AI/ML water treatment options. A determination on which AI/ML process would be best suited for the given wastewater/PW based on the intended use of the treated water could be made, and then used to estimate how much better optimized the process of treating the wastewater/PW would be. This information would allow companies to determine if and when these AI/ML implementations would be worth the initial cost of implementation.

References

- Abdelwahab, O.; Amin, N.K.; El-Ashtoukhy, E.Z. Electrochemical removal of phenol from oil refinery wastewater. Journal of hazardous materials 2009, 163, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.A.; Bahadori, A. A simple approach for screening enhanced oil recovery methods: application of artificial intelligence. Petroleum Science and Technology 2016, 34, 1887–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Shayya, W.H.; Hoey, D.; Mahendran, A.; Morris, R.; Al-Handaly, J. Use of evaporation ponds for brine disposal in desalination plants. Desalination 2000, 130, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aani, S.; Bonny, T.; Hasan, S.W.; Hilal, N. Can machine language and artificial intelligence revolutionize process automation for water treatment and desalination? . Desalination 2019, 458, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuboury DA, D.A.; Palaniandy, P.; Abdul Aziz, H.B.; Feroz SA, D.A. Treatment of petroleum wastewater by conventional and new technologies-A review. Glob. Nest J 2017, 19, 439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Aamir, M.; Iqbal, M. W.; Nosheen, M.; Ashraf, M. U.; Shaf, A.; Almarhabi, K. A.; Bahaddad, A. A. AMDDLmodel: Android smartphones malware detection using deep learning model. Plos one 2024, 19, e0296722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheghmoalla, M.; Mehrvar, M. Integrated and Hybrid Processes for the Treatment of Actual Wastewaters Containing Micropollutants: A Review on Recent Advances. Processes 2024, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhaeebi, M.; Jamil, K.; Sebak, A. R. Ultra-wideband antenna for RFID underground oil industry application. In 2014 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Modelling and Simulation; IEEE, 2014; pp. 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Anifowose, F.; Abdulraheem, A. Fuzzy logic-driven and SVM-driven hybrid computational intelligence models applied to oil and gas reservoir characterization. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2011, 3, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anifowose, F.; Ewenla, A.; Eludiora, S. Prediction of oil and gas reservoir properties using support vector machines. In IPTC 2012: International Petroleum Technology Conference; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2012; p. cp-280. [Google Scholar]

- Astsauri, T.; Habiburrahman, M.; Ibrahim, A.F.; Wang, Y. Utilizing machine learning for flow zone indicators prediction and hydraulic flow unit classification. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, Z.; Mikhaylov, I. S.; Aung, Y. T. Artificial intelligence methods application in oil industry. In 2020 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (EIConRus); IEEE, 2020; pp. 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, O.; Holzmann, J.; Yaqoob, T.; Teodoriu, C. Application of artificial intelligence methods in drilling system design and operations: a review of the state of the art. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing Research 2015, 5, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.L.; Yin, Y.B.; Hanna, T.; Atkinson, A.J.; Alvarez, P.J.; Tekavec, T.N.; Wong, M.S. Fit-for-purpose treatment goals for produced waters in shale oil and gas fields. Water Research 2020, 173, 115467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, H. Unleashing industry 4.0 opportunities: Big data analytics in the midstream oil & gas sector. In International Petroleum Technology Conference; IPTC, 2020; p. D033S076R002. [Google Scholar]

- El-Abbasy, M.S.; Senouci, A.; Zayed, T.; Mirahadi, F.; Parvizsedghy, L. Artificial neural network models for predicting condition of offshore oil and gas pipelines. Automation in Construction 2014, 45, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzwayie, A.; El-Shafie, A.; Yaseen, Z. M.; Afan, H. A.; Allawi, M. F. RBFNN-based model for heavy metal prediction for different climatic and pollution conditions. Neural Computing and Applications 2017, 28, 1991–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadali, O.A.; Farrag, T.E.; Ibrahim, E.I.; Abdelbasier, A.M. Fixed bed electrochemical reactors for removal of methomyl from wastewater. International Water Technology Journal, IWTJ, 2017, 7.

- G, Y. (2017, September 7). The 7 steps of machine learning. Medium. Retrieved April 17, 2022, from https://towardsdatascience.com/the-7-steps-of-machine-learning-2877d7e5548e P.

- Gharbi, R.B.; Mansoori, G.A. An introduction to artificial intelligence applications in petroleum exploration and production. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2005, 49(3-4), 93-96.

- Grace, K.; Salvatier, J.; Dafoe, A.; Zhang, B.; Evans, O. When will AI exceed human performance? Evidence from AI experts. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2018, 62, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, N.A.; Jones, C.E.; Weiland, G.S.; Weiland, R.H. Predicting corrosion rates in amine and sour water systems. Gas 2014, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Heddam, S.; Bermad, A.; Dechemi, N. Applications of radial-basis function and generalized regression neural networks for modeling of coagulant dosage in a drinking water-treatment plant: comparative study. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2011, 137, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.; Ware, R.L.; Park, J.; McKenna, A.M.; Rodgers, R.P.; Nikolau, B.J.; Marshall, A.G. Statistically significant differences in composition of petroleum crude oils revealed by volcano plots generated from ultrahigh resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectra. Energy & fuels 2018, 32, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, D.; Korovin, I.; Shabanov, V. Oil fields monitoring by groups of mobile micro-robots using distributed neural networks. In 2018 Joint 7th International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV) and 2018 2nd International Conference on Imaging, Vision & Pattern Recognition (icIVPR); IEEE, 2018; pp. 588–593. [Google Scholar]

- Kamali, M.; Appels, L.; Yu, X.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Dewil, R. Artificial intelligence as a sustainable tool in wastewater treatment using membrane bioreactors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 417, 128070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamehchi, E.; Kivi, I.R.; Akbari, M. A novel approach to sand production prediction using artificial intelligence. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2014, 123, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondash, A.J.; Albright, E.; Vengosh, A. Quantity of flowback and produced waters from unconventional oil and gas exploration. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 574, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroteev, D.; Tekic, Z. Artificial intelligence in oil and gas upstream: Trends, challenges, and scenarios for the future. Energy and AI, 2021, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, H.; Cao, N.; Tian, H.; Cheng, S. Applications of artificial intelligence in oil and gas development. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massidda, L.; Bettio, F.; Marrocu, M. Probabilistic day-ahead prediction of PV generation. A comparative analysis of forecasting methodologies and of the factors influencing accuracy. Solar Energy 2024, 271, 112422. [Google Scholar]

- Mawlad, A. A., Mohand, R., Agnihotri, P., Pamungkas, S., Omobude, O., Mustapha, H., ... & Razouki, A. Embracing the digital and artificial intelligence revolution for reservoir management-Intelligent integrated subsurface modelling IISM. In Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference; SPE, 2019; p. D011S004R004.

- Mirjalili, S. Evolutionary algorithms and neural networks. Studies in computational intelligence 2019, 780. [Google Scholar]

- Mohaghegh, S.D. Reservoir simulation and modeling based on artificial intelligence and data mining (AI&DM). Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2011, 3, 697–705. [Google Scholar]

- Mohaghegh, S. D. Subsurface analytics: Contribution of artificial intelligence and machine learning to reservoir engineering, reservoir modeling, and reservoir management. 2020.

- Nag, S.; Mondal, A.; Roy, D. N.; Bar, N.; Das, S. K. Sustainable bioremediation of Cd (II) from aqueous solution using natural waste materials: kinetics, equilibrium, thermodynamics, toxicity studies and GA-ANN hybrid modelling. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2018, 11, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri, S.; Khosravani, M.R.; Weinberg, K. Fracture mechanics and mechanical fault detection by artificial intelligence methods: A review. Engineering Failure Analysis 2017, 81, 270–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, J. M.; Sauer, T. C., Jr.; Maciolek, N. Composition, fate and effects of produced water discharges to nearshore marine waters. In Produced Water: Technological/Environmental Issues and Solutions; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1992; pp. 371–385. [Google Scholar]

- Olajire, A.A. Recent advances on the treatment technology of oil and gas produced water for sustainable energy industry-mechanistic aspects and process chemistry perspectives. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2020, 4, 100049. [Google Scholar]

- Padaki, M.; Murali, R.S.; Abdullah, M.S.; Misdan, N.; Moslehyani, A.; Kassim, M.A.; Ismail, A.F. Membrane technology enhancement in oil–water separation. A review. Desalination 2015, 357, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, H.; Prajapati, D.; Mahida, D.; Shah, M. Transforming petroleum downstream sector through big data: a holistic review. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology 2020, 10, 2601–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, F. H. The Impact of the Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) TLV/STEL Reduction of 2010. In ASSE Professional Development Conference and Exposition; ASSE, 2014; p. ASSE-14. [Google Scholar]

- Pichtel, J. Oil and gas production wastewater: Soil contamination and pollution prevention. Applied and environmental soil science 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priakanth, S. Gopikrihnan. “Chapter 67 Machine Learning Techniques for Internet of Things”, IGI Global, 2021.

- Riquelme-Dominguez, J.M.; Carranza-García, M.; Lara-Benítez, P.; González-Longatt, F.M. A machine learning-based methodology for short-term kinetic energy forecasting with real-time application: Nordic Power System case. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2024, 156, 109730. [Google Scholar]

- Radelyuk, I.; Tussupova, K.; Zhapargazinova, K.; Yelubay, M.; Persson, M. Pitfalls of wastewater treatment in oil refinery enterprises in Kazakhstan—a system Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M., Yazdizadeh, H., & Yazdizadeh, A. (2017, July). Leakage detection in a gas pipeline using artificial neural networks based on wireless sensor network and Internet of Things. In 2017 IEEE 15th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN) (pp. 659-664). IEEE.

- Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “Fossil Fuels.” Our World in Data, 28 Nov. 2020, https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels#:~:text=Globally%2C%20fossil%20fuels%20accou nt%20for,summed%20together.

- Romero, C. E., Carter, J. N., Gringarten, A. C., & Zimmerman, R. W. (2000, November). A modified genetic algorithm for reservoir characterisation. In SPE International Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition in China (pp. SPE-64765). SPE.

- Sattari, F.; Macciotta, R.; Kurian, D.; Lefsrud, L. Application of Bayesian network and artificial intelligence to reduce accident/incident rates in oil & gas companies. Safety Science 2021, 133, 104981. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J. M., Sansudin, S., Fadhil, M. I. M., Gazali, I. M., Zakeria, A. F., & Husni, H. (2024, February). Real Time Petrophysics via Artificial Intelligence in Brown Field Development. In International Petroleum Technology Conference (p. D011S026R004). IPTC.

- Suleĭmanov, R.R.; Gabbasova, I.M.; Sitdikov, R.N. Changes in the properties of oily gray forest soil during biological reclamation. Izvestiia Akademii nauk. Seriia biologicheskaia 2005, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utvik TI, R. Chemical characterisation of produced water from four offshore oil production platforms in the North Sea. Chemosphere 1999, 39, 2593–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjani, S.; Joshi, R.; Srivastava, V.K.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Treatment of wastewater from petroleum industry: current practices and perspectives. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 27172–27180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veil, J. A., Puder, M. G., & Elcock, D. (2004). A white paper describing produced water from production of crude oil, natural gas, and coal bed methane (No. ANL/EA/RP-112631). Argonne National Lab., IL (US).

- Verma, N.; Maurya, S.P.; Singh, K.H.; Singh, R.; Singh, A.P.; Hema, G.; Singh, R. Comparison of neural networks techniques to predict subsurface parameters based on seismic inversion: a machine learning approach. Earth Science Informatics 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo Thanh, H.; Sugai, Y.; Sasaki, K. Application of artificial neural network for predicting the performance of CO2 enhanced oil recovery and storage in residual oil zones. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H. T. T.; Gomez, F.; Cherelle, P.; Lefeber, D.; Nowé, A.; Vanderborght, B. ED-FNN: A new deep learning algorithm to detect percentage of the gait cycle for powered prostheses. Sensors 2018, 18, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, T.R.; Gosine, R.G.; James, L.A.; Mann, G.K.; De Silva, O.; Warrian, P.J. The internet of things in the oil and gas industry: a systematic review. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 8654–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, G.; Yang, M.; Wu, S.; Hu, J. Occurrences and behaviors of naphthenic acids in a petroleum refinery wastewater treatment plant. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49, 5796–5804. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wu, T. A deep learning interpretable model for river dissolved oxygen multi-step and interval prediction based on multi-source data fusion. Journal of Hydrology 2024, 629, 130637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., Zhang, S., Han, Y., & Wolfe, F. A. (2019). Treatment of petrochemical wastewater and produced water from oil and gas. In Water Environment Research (Vol. 91, Issue 10, pp. 1025–1033). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Windarto, A. P., Dewi, L. S., & Hartama, D. (2017). Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Predicting the Value of Indonesian Oil and Gas Exports With BP Algorithm.

- Yasin, Y., Ahmad, F. B. H., Ghaffari-Moghaddam, M., & Khajeh, M. (2014). Application of a hybrid artificial neural network–genetic algorithm approach to optimize the lead ions removal from aqueous solutions using intercalated tartrate-Mg–Al layered double hydroxides. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management, 1, 2-7.

- Yuan, R.; Li, Z.; Guan, X.; Xu, L. An SVM-based machine learning method for accurate internet traffic classification. Information Systems Frontiers 2010, 12, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhong, N.; Tu, X.; Jia, J.; Wang, J. Tackling environmental challenges in pollution controls using artificial intelligence: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 699, 134279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X. Grid search with a weighted error function: Hyper-parameter optimization for financial time series forecasting. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 111362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Petroleum wastewater treatment flowchart (Varjani et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Petroleum wastewater treatment flowchart (Varjani et al., 2019).

Figure 2.

Trial 1 for the observed and predicted chlorine dosage as the number of samples increases (Nag, A. et al. 2018).

Figure 2.

Trial 1 for the observed and predicted chlorine dosage as the number of samples increases (Nag, A. et al. 2018).

Figure 3.

Trial 2 for the observed and predicted chlorine dosage as the number of samples increases (Nag, A. et al. 2018).

Figure 3.

Trial 2 for the observed and predicted chlorine dosage as the number of samples increases (Nag, A. et al. 2018).

Figure 4.

Predicted data for a-train dye and b-train due vs experimental data (Nasiri, S., et al., 2017).

Figure 4.

Predicted data for a-train dye and b-train due vs experimental data (Nasiri, S., et al., 2017).

Figure 5.

Steps of ANN neural network processing (Tavish, et al., 2014).

Figure 5.

Steps of ANN neural network processing (Tavish, et al., 2014).

Figure 6.

The graph of Ph effect on (Nag, et al., 2018).

Figure 6.

The graph of Ph effect on (Nag, et al., 2018).

Figure 7.

Adsorbent dose effect in Cd (II) (Nag, et al., 2018).

Figure 7.

Adsorbent dose effect in Cd (II) (Nag, et al., 2018).

Figure 8.

Different operators used in Genetic algorithms (Katoch, et al., 2021).

Figure 8.

Different operators used in Genetic algorithms (Katoch, et al., 2021).

Figure 9.

Produced water cycle (Conrad, et al. 2020).

Figure 9.

Produced water cycle (Conrad, et al. 2020).

Figure 10.

Block diagram of produced water treatments (Conrad, Yin, Hanna 2020).

Figure 10.

Block diagram of produced water treatments (Conrad, Yin, Hanna 2020).

Figure 11.

Final treatment goals for disposal, reuse, and recycling of wastewater/P.W. based on ten contamination metrics (Conrad, et al. 2020).

Figure 11.

Final treatment goals for disposal, reuse, and recycling of wastewater/P.W. based on ten contamination metrics (Conrad, et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Examples of various wastewater treatment methods (Al Deen Atallah Aljuboury et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Examples of various wastewater treatment methods (Al Deen Atallah Aljuboury et al., 2017).

| Method Applied |

Wastewater Type |

Removed Pollutants |

Maximum Removal Efficiency (%) |

Reference |

| The physicochemical processes |

A refinery wastewater |

Total naphthenic acids (NAs)

Aromatic naphthenic acids |

16

24 |

Wang et al. (2015) |

| An immersed membrane process |

Petroleum refinery wastewater |

Wastewater oil content |

69 |

Al-Malack (2016) |

| Membrane bioreactor (MBR) |

Petrochemical wastewater |

Heavy Metals

Iron |

70

75 |

Malamis et al., (2015) |

| Nanocomposite membrane with the multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) incorporated in Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) matrix |

Refinery wastewater |

Oil |

|

Moslehyani et al., (2006) |

| A crossflow membrane bioreactor (CF-MBR) |

Petroleum Wastewater |

COD |

93 |

Rahman and Al-Malack (2006) |

| The hollow-fiber membrane bioreactor (HF-MBR) |

Real petroleum refinery wastewater |

COD

BODS

TSS

VSS

Turbidity |

82

89

98

99

98 |

Razavi and Miri (2015) |

| Membrane sequencing batch reactor |

A synthetic petroleum wastewater |

Hydrocarbon pollutants |

97 |

Shariati et al., (2011) |

| Ultra-filtration (UF) membranes |

Refinery wastewater |

COD |

44 |

Asatekin and Mayes (2009) |

| Poly-aluminum chloride and ferric chloride for coagulation treatment |

Petroleum wastewater |

COD |

58 |

Farajnezhad & Gharrbani (2012) |

| Poly-zinc silicate (PZSS) and anion polyacrylamide (A-PAM) for coagulation/flocculation treatment |

Heavy oil wastewater |

Oil |

99 |

Zeng et al. (2007) |

| Subsequent coagulation/H2O2 |

Petroleum refinery wastewater |

COD

BODS

|

58

78 |

Wagner and Nicell (2001) |

| Coagulation by alumCoagulation by ferric chloride (FeCl3) |

Petrochemical wastewater |

COD

COD |

61

52 |

Altaher et al., (2011) |

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of using common AI algorithms (Li et al. 2021).

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of using common AI algorithms (Li et al. 2021).

Table 3.

Dynamic predictions using AI in oilfield development (Li et al. 2021).

Table 3.

Dynamic predictions using AI in oilfield development (Li et al. 2021).

Table 4.

Plan optimization using AI algorithms in the oil and gas industry (Li et al. 2021).

Table 4.

Plan optimization using AI algorithms in the oil and gas industry (Li et al. 2021).

Table 5.

Identification of residual oil using AI algorithm methods (Li et al. 2021).

Table 5.

Identification of residual oil using AI algorithm methods (Li et al. 2021).

Table 6.

Fracture detection using AI (Li et al. 2021).

Table 6.

Fracture detection using AI (Li et al. 2021).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).