1. Introduction

In 2012, the German commission for hospital hygiene and infection prevention (German abbreviation KRINKO) and the federal institute for drugs and medical devices (German abbreviation BfArM) published guidelines on the cleaning of medical devices, including ultrasound (US) probes [

1]. Over the last years, automated reprocessing has become more and more popular due to the comprehensive validation capabilities of the entire process [

1,

2]. However, other alternatives for cleaning US probes have been established as well, which do not require the expensive purchase of separate hardware: immersion disinfection and wipe disinfection. The Robert Koch Institute's (RKI) Epidemiological Bulletin No. 44/2021 highlights the lack of validation of final disinfection of semi-critical medical devices by wipe disinfection, especially for US probes with mucosal contact [

3].

The use of high-level disinfection wipes with alcohol or chlorine dioxide for surface disinfection of non-critical and semi-critical medical devices like US probes is an essential component of infection control in healthcare settings worldwide [

4]. Chlorine dioxide has many advantages as a disinfectant and has the potential to effectively reduce the risk of infection transmission from contaminated US probes and endoscopes [

5,

6]. Disposable chlorine dioxide wipes provide high-level disinfection in laboratory and clinical settings. They offer a rapid, safe, and cost-effective method for disinfecting semi-critical devices such as endoscopes or US probes [

7]. Studies have shown that pH changes can affect chlorine-containing disinfectants, highlighting the importance of optimizing disinfectant properties for maximum efficacy. This may be relevant to chlorine dioxide wipes as well [

8]

Systematic reviews have shown that certain disinfectants, such as chlorhexidine and chlorine dioxide, are effective in reducing bacterial contamination during stethoscope disinfection. This suggests that these disinfectants may also be effective for US probe disinfection [

9]. The use of high-level disinfection wipes with chlorine dioxide for surface disinfection of semi-critical US probes is an effective strategy for minimizing the risk of infection transmission. The evidence supports the potential of these wipes to offer a feasible disinfection solution in healthcare settings, thereby enhancing patient safety and infection control practices.

Among other wipes for disinfection, the Tristel Trio Wipes System (Tristel, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom) is described as meeting the stringent requirements for the reprocessing of semi-critical medical devices, including compliance with manufacturer's specifications and the easy use of validated procedures to ensure safety and traceability [

6,

10]. However, there is a notable omission in the discussion. Specifically, there is a lack of detailed analysis concerning the system's ability to provide consistent wetting across all surfaces during the application process. This detail is critical, as uneven wetting can lead to areas of insufficient disinfection, potentially compromising the safety and efficacy of the reprocessing. To fully meet the criteria of being suitable, validated and safe, it is essential that there is clear empirical evidence of the system's ability to maintain consistent wetting, thereby ensuring uniform disinfection and compliance with the highest standards of hygiene. Without this evidence, there remains a gap in the validation process, calling into question the system's overall reliability in meeting the stated hygiene requirements.

US probes utilized in semi-critical applications, such as for example endocavitary probes, necessitate meticulous reprocessing post-use to mitigate the risk of cross-contamination and infections [

11]. However, in the case of ultrasound-guided puncture or biopsy, for example of the breast, or - as it is common in nuclear medicine - screening and treatment of thyroid nodules suspected of being malignant , hygienic reprocessing also plays a key role [

4,

12]. Immediately following patient examination, probes should be cleansed of any visible contaminants using a manufacturer-recommended wipe suitable for the purpose. Users can only identify faulty applications or cleaning gaps if they are made aware of existing wetting gaps during the training process through visible means, as demonstrated in a previous study on hand hygiene training [

13]. Subsequently, a high-efficacy disinfection process is imperative. This often involves achieving a sporicidal effect, which can be accomplished through wipe disinfection or with the aid of automated disinfection systems, such as a Trophon device. The probes must be handled in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines and prevailing infection control standards, paying close attention to the contact time of the disinfectant and its compatibility with the probe material. Following disinfection, it is crucial to dry the probe and store it in a clean and dry environment to prevent recontamination. Documentation of the entire reprocessing procedure is vital to ensure traceability and adherence to hygiene regulations.

In fact, it is necessary to understand where problem areas for manually wipe disinfection exist, which this work tried to investigate. Within the study, the thoroughness of the cleaning process by wipes should be visualized using a colored set.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Two participants were chosen for the study, each with a period of experience between two and five years using Tristel Trio Wipes to clean US probes after guided biopsy procedures. They proved to be highly proficient and compliant to the stringent disinfection protocols required in medical facilities. According to the manufacturers of disinfectant wipes, their knowledge not only ensures a high level of hygiene and patient safety, but also ensures that the decontamination process is rationalized and the turnaround time between procedures is shortened. They know the importance of chronological use of the wipes, including cleaning, high-level disinfection and rinsing. Participants will also have knowledge of the importance of following manufacturer and hospital guidelines to maintain equipment integrity and ensure patient safety. This is evidenced by a detailed, paper-based protocol booklet for all applications. The results of each color application were not shown to the participants.

2.2. Probes

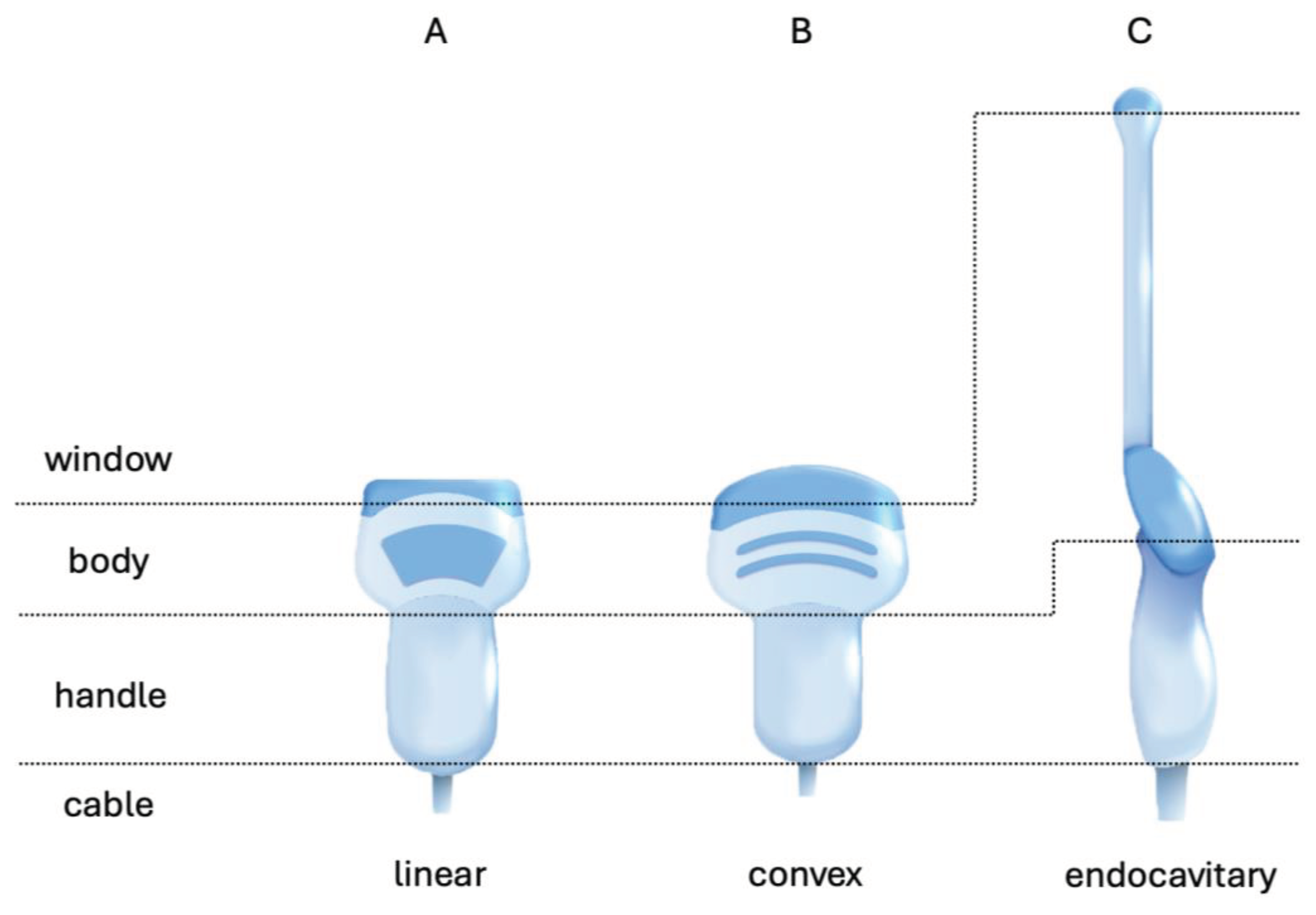

US probes are mostly composed of a window-area, a body, a handle and cable (

Figure 1). The cable extends from the handle to a plug that connects to the US device. Even if only the window area, particularly of linear and convex probes, has direct contact with the patient's skin during routine work, all parts of the probe may come into contact with the patient depending on the procedure. When using endocavitary probes for gynaecological purposes, there is always contact with the mucous membranes of the window area and probe body.

Most ultrasonic probes have an orientation marker (indicator) on the side of the window or the body, which allows the user to quickly locate the left side of the image on the monitor for all standard applications. Depending on the model and manufacturer, the clip-on for the reusable bracket and the disposable snap-on are located on the opposite side (if applicable).

Four probes of three different types were used in this study. These probes play a different but complementary role in diagnostic US imaging and fulfil different clinical requirements for medical specialties. They were selected for this first series of tests as decommissioned devices, which are no longer used on patients. Two linear probes were chosen, the VF10-5 (Siemens Healthineers AG, Forchheim, Germany) and the X6-16L (Vinno Technology Co., Jiangsu Province) which primarily utilized for high-resolution imaging of superficial structures and small parts of the body, such as the thyroid, and can used with additional brackets for image guided biopsy for example thyroid nodules (see

Figure 1 A) [

14]. One convex probe was selected, the CH5-2 probe (Siemens Healthineers AG, Forchheim, Germany) is designed for abdominal imaging (see

Figure 1 B). This probe also has attachment points for customizable multi-purpose needle guided systems. Its curved shape allows for deeper penetration into the body, making it suitable for visualizing organs like the liver, or special fusion imaging possibilities of the kidneys [

15]. At last one endocavitary probe was applied, the E8CS (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA) for abdominal or even gynaecological applications. The E8CS also has molds for sterilisable reusable biopsy needle guide clips for transrectal and transvaginal procedures with different types of needles.

2.3. Wipes

The instrument disinfection system (EQUINOS, Heyfair GmbH, Jena, Germany) is a novel manual instrument reprocessing kit for US probes or other non-critical and semi-critical medical devices. It facilitates indicators to validate the complete and effective cleaning and disinfection. The kit includes two individually packed wipes (20 x 20 cm). The first wipe is used to clean the surface. It is embedded with a blue dye, which reveals the extent of wetted areas on the US head. This dye indicates whether the wipe was successfully applied, and thus the probe properly cleaned. The next step involves a disinfection wipe, which contains in-situ generated chlorine dioxide. The active ingredient immediately discolors the blue indicator, and thus shows proper and complete disinfection.

2.4. Study Cleaning Procedure

For the sake of this study, both steps were performed while wearing blue filter glasses, which blinded the participants for the color and therefore obstructed the immediate visibility of wetting gaps. This study setting a scenario comparable to common, uncolored wipes.

The participants were instructed to wear blue filter glasses before putting on gloves. In the initial stage, the study assistant distributed the first pack of blue dye wipes. The blue dye wipe was applied by the user without any time limit until they declared the pre-cleaning process as complete. The study assistant documented all four sides of the US probe by taking pictures of the front, back, left, and right sides. Meanwhile, the participants continued to wear the blue filter goggles. The study did not document or analyze the second step, which involved using another pack containing a chlorine dioxide wipe for disinfection. This step was necessary to completely remove the dye film from the US probe.

2.5. Statistics

The Fisher exact test was performed on the nominal values. Value '1' indicates a wetting gap at that transducer site (front, back, left and right) location (regardless of the absolute area size) and '0' indicates no wetting gap at that transducer location. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

All measurements and implementations were technically successful (

Figure 2). Through photo documentation, it was possible to conduct a retrospective examination of all wetting gaps. This allowed a relative and qualitative analysis, revealing areas that were not fully covered by cleaning. The visual evidence provided by the photographs served as a critical tool in assessing the thoroughness of the steps of the disinfection process, highlighting the effectiveness of using EQUINOS wipes for identifying and addressing incomplete disinfection of US probes.

In all procedures, regardless of the type of US probe, the moulds and clip-on areas were not sufficiently stained blue. This indicates that they could not have been disinfected in the second step in a verifiable or valid manner.

4. Discussion

The use of disinfectant wipes on US probes, particularly in the context of wetting gaps at the junctions with snap-lock brackets for needle-guided biopsy, necessitates a thorough examination of the effectiveness of disinfection methods and the challenges arising from the complexity of device shapes. As shown on

Figure 2 and

Table 1 the areas inside the moulds in the most cases have not been colored blue and therefore are not properly cleaned. It can be assumed, that the chlorine dioxide wipe (in the second, undocumented step) cannot achieve a sufficient disinfection in this area (p value .001).

Former studies, such as that by Rutala et al., have already shown that especially in US examinations with biopsy holders, these must be removed during cleaning in order to achieve a sufficient reduction in bacterial load [

16]. The results of this work showed that, even without brackets attached, these areas around the clip-on were difficult to completely wet, i.e. clean, by wipes using standard disinfection processes.

Figure 2 also shows for one model, it is also difficult to achieve complete wetting of the groove connecting between the two halves of the housing (

Figure 2 A right).

Manual disinfection methods were considered difficult to validate objectively. Although Tristel Trio Wipes, as one commercially available product, promises that complete cleaning with wipe disinfection can be validated at moderate cost, the initial test results of this work indicate that this is not fully possible for the user without dye. Only when the wipe disinfectant contacts all areas it is possible to eliminate bacterial contamination or pathogenic germs significantly. A study by other authors compared manual disinfection methods with UV-C light. Both techniques could effectively eliminate pathogenic germs, including Enterococcus faecalis and Klebsiella pneumoniae. However, manual disinfection with disinfectant wipes showed a higher contamination rate regarding all bacteria, indicating the limits of manual disinfection on complex surface structures and highly curved housing shapes [

17].

The persistence of microbial contamination on covered transvaginal US probes despite low-level disinfection procedures highlights the need for a thorough re-evaluation of disinfection methods. One study demonstrated that significant microbial persistence was observed on disinfected probes despite the use of wipes impregnated with a quaternary ammonium compound and chlorhexidine [

18].

These findings suggest that the application of disinfectant wipes on US probes, particularly those with complex shapes and hard-to-reach areas such as snap-lock junctions, may not be sufficient to ensure complete cleaning, limiting the possibility for disinfection. Research emphasizes the importance of carefully selecting disinfection procedures and considering potentially complementary methods to effectively reduce microbial contamination and minimize the risk of cross-contamination.

5. Conclusions

This first work showed that also experienced users of manual wipe disinfection do not achieve complete surface wetting. Colored wipes almost perfectly wet larger and smooth surfaces during wipe disinfection. However, in all applications, clip-on areas, and moulds for clamps / holders for biopsy aids are not cleaned properly.

The use of colored wipes underscores the RKI's statement of 2020 indicating that the validity of normal wipe disinfection of semi-critical medical devices is currently uncertain. Further investigation with a larger sample of US probes and a simultaneous determination of the absolute and relative non-wetted surface areas is required. This investigation should be performed by users with varying levels of experience to identify probe-specific problem areas. It is important to quantitatively evaluate the learning effect after understanding these problem areas. Furthermore, a comprehensive assessment of both steps, cleaning with colored wipes and disinfection with chlorine dioxide, should be taken into account in a broader investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and F.G.; methodology, C.K. and F.G.; software, C.K.; validation, C.K. formal analysis, C.K.; investigation, C.K.; resources, C.K. and F.G.; data curation, C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K. and F.G.; writing—review and editing, C.K. and F.G.; visualization, C.K.; supervision, C.K. and F.G.; project administration, C.K. and F.G.; funding acquisition, C.K. C.K. works as a medical physics expert as well as a medical devices representative and F.G. is a senior physician for nuclear medicine as well as a hygiene representative in the clinic for nuclear medicine at the University Hospital Jena.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Maria Zechel from the Institute for Infection Medicine and Hospital Hygiene at Jena University Hospital. As a specialist in hygiene and environmental medicine, she always had an open ear and supported the project with information on wipe disinfection. We would like to thank Max-Richard Pohl from Medical and device technology department at Jena University Hospital for providing old US probes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Commission for Hospital, H.; Infection, P.; Federal Institute for, D.; Medical, D. [Hygiene requirements for the reprocessing of medical devices. Recommendation of the Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Prevention (KRINKO) at the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) and the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2012, 55, 1244–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhsen, C.M.; Humphreys, H.; Koerner, R.J.; Grenier, N.; Brady, A.; Sidhu, P.; Nicolau, C.; Mostbeck, G.; D'Onofrio, M.; Gangi, A.; et al. Infection prevention and control in ultrasound - best practice recommendations from the European Society of Radiology Ultrasound Working Group. Insights Imaging 2017, 8, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Die für Medizinprodukte zuständigen Obersten Landes behörden (AGMP), das Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM) und das Robert Koch-Institut (RKI): Validierung der abschließenden Desinfektion von semikritischen Medizinprodukten mittels Wischdesinfektion. Epid Bull 2021, 13–15. [CrossRef]

- Westerway, S.C.; Basseal, J.M.; Abramowicz, J.S. Medical Ultrasound Disinfection and Hygiene Practices: WFUMB Global Survey Results. Ultrasound Med Biol 2019, 45, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, D. An evaluation of the use of chlorine dioxide (Tristel One-Shot) in an automated washer/disinfector (Medivator) fitted with a chlorine dioxide generator for decontamination of flexible endoscopes. J Hosp Infect 2001, 48, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Vossebein, L.; Zille, A. Efficacy of disinfectant-impregnated wipes used for surface disinfection in hospitals: a review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofanelli, M.; Capriotti, V.; Saraniti, C.; Marcuzzo, A.V.; Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; Tirelli, G. Disposable chlorine dioxide wipes for high-level disinfection in the ENT department: A systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol 2020, 41, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi-Fedele, G.; Guastalli, A.R.; Dogramaci, E.J.; Steier, L.; De Figueiredo, J.A. Influence of pH changes on chlorine-containing endodontic irrigating solutions. Int Endod J 2011, 44, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitani, M.; Bezzini, D.; Moirano, F.; Bedogni, C.; Messina, G. Methods of Disinfecting Stethoscopes: Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitchcock, B.; Moynan, S.; Frampton, C.; Reuther, R.; Gilling, P.; Rowe, F. A randomised, single-blind comparison of high-level disinfectants for flexible nasendoscopes. J Laryngol Otol 2016, 130, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeg, P.; Gauer, J. Automatische, validierte, nicht-toxische High-level-Desinfektion (HLD) von Ultraschallsonden. Krankenhaus-Hygiene + Infektionsverhütung 2014, 36, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, J.; Hug, S.; Martiny, H.; Golatta, M.; Feisst, M.; Madjar, H.; Bader, W.; Hahn, M. Standards of hygiene for ultrasound-guided core cut biopsies of the breast. Ultraschall Med 2018, 39, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnel, C.; Salomo, S.; Pagiatakis, H.; Hubner, J.; Seifert, P.; Freesmeyer, M.; Guhne, F. Medical Students' and Radiology Technician Trainees' eHealth Literacy and Hygiene Awareness-Asynchronous and Synchronous Digital Hand Hygiene Training in a Single-Center Trial. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freesmeyer, M.; Kuhnel, C.; Guhne, F.; Seifert, P. Standard Needle Magnetization for Ultrasound Needle Guidance: First Clinical Experiences in Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology of Thyroid Nodules. J Ultrasound Med 2019, 38, 3311–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guhne, F.; Weigel, F.; Kuhnel, C.; Seifert, P.; Freesmeyer, M. DMSA-camSPECT/US fusion imaging of children's kidneys - Proof of feasibility. Nuklearmedizin 2020, 59, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutala, W.A.; Gergen, M.F.; Weber, D.J. Disinfection of a probe used in ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007, 28, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, J.; Kossow, A.; Oelmeier de Murcia, K.; Heese, S.; Braun, J.; Mollmann, U.; Schmitz, R.; Mollers, M. Disinfection of Transvaginal Ultrasound Probes by Ultraviolet C - A clinical Evaluation of Automated and Manual Reprocessing Methods. Ultraschall Med 2020, 41, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M'Zali, F.; Bounizra, C.; Leroy, S.; Mekki, Y.; Quentin-Noury, C.; Kann, M. Persistence of microbial contamination on transvaginal ultrasound probes despite low-level disinfection procedure. PLoS One 2014, 9, e93368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).