1. Intorduction

The Upper Hunter Valley is a major coal mining area in the State of New South Wales (NSW), Australia (ABARES, 2023). PM10 (air-borne particle with an aerodynamic diameter less than 10 micrometres) pollution has become a major air quality concern in local communities, primarily due to the ongoing increase of open-cut coal mining activities and the impact of climate variability and change on regional environments (Jiang et al., 2024). In partnership with the Upper Hunter coal and power industries, the NSW Government has commissioned the Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network (UHAQMN; first established during 2010-2012) to provide local communities, industries and the Government with reliable and up-to-date information on air quality within the valley (

Figure 1; Riley et al., 2020; POEO Regulation, 2021; OEH, 2017). The present study was initiated to quantitatively examine the spatial and temporal variability of PM10 pollution in the region, based on the long-term (2012-2022) multi-site air quality measurements from the UHAQMN and by applying advanced data visualisation and machine learning techniques. Recently Jiang et al. (2024) reported the major findings from an investigation on the spatial and temporal variability modes of PM10 pollution in the valley. This companion text will be focused on visualising the linkages between the elevated PM10 pollution in valley subregions and the dominant local- and synoptic-scale meteorological conditions influencing the study region.

On a broad scale, the Upper Hunter Valley is oriented northwest-southeast (NW-SE), approximately 30 km wide and with the terrain elevation estimated in the range of 300-380 m from the bottom (Singleton South) to the top (Merriwa) [

Figure 1; further details in Jiang et al. (2024)). On average, PM10 pollution in the region is relatively higher than most other regions in the State (DPE, 2022). The main sources of PM10 emissions are local open-cut coal mining activities and (wind-blown) surface soil erosion (NSWEPA, 2019). Coal-fired electricity generation, agriculture, bushfires, prescribed hazard reduction burnings (HRBs) and state-wide dust storms also contribute to PM10 pollution in the valley. The prevailing surface winds tend to follow the NW-SE orientation of the valley (DPE, 2022; Holmes, 2008). The most frequent winds are north-westerlies in winter and south-easterlies in summer, with wind directions less defined in autumn and spring. Nocturnal and early morning down-valley drainage flows, and daytime up-valley slope winds or sea breezes are observed due to factors such as terrain effects and changes in land/atmospheric heating conditions (Jiang, 2017). The precipitation in the region is low compared to coastal areas to the east, and varies significantly across years, with higher rainfall in summer and early autumn and lower rainfall in winter and early spring (DPE, 2022; OEH, 2017).

Physical and thermal-dynamic properties of the atmosphere play important roles in determining the level of air pollution over a region, through processes such as pollutant generation/emission, transformation, transport, dispersion and/or deposition/removal (Oaks, 2002). Globally numerous studies examined the linkages between meteorological conditions and air quality in urban environments. Most of these highlighted that poor air quality is associated with calm/stable conditions under anticyclonic situations, and good air quality (often) occurs under unstable/cyclonic conditions (e.g., Lai et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; Salvador et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2017a, b; Pierce et al., 2011). In addition, a few studies also showed that the passage of low pressure or frontal systems can result in higher particle pollution due to increased soil erosion by wind or transport of pollutants or their precursors (e.g., Pardo et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2017a; Jiang et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2009; Dayan and Levy, 2005; Jiang et al., 2005). In contrast, there are relatively few studies on how meteorological conditions affect the variability of PM10 pollution in rural valley environments. Of those few studies, most researchers relied on the use of correlation analysis and (often short-term) data from selected sites (e.g., Quimbayo-Duarte, 2021; Fortelli et al., 2016; Reisen et al., 2017; Czernecki et al., 2017; Giri et al., 2008). In summary, elevated PM10 pollution in those valleys were associated with (prolonged) dry conditions (low rainfall and humidity), low winds, thermal inversions (low mixing heights), and/or under the influence of high-pressure systems.

Locally a small number of studies examined the PM10-meteorolgoy relationships in the Upper Hunter Valley. Of these, early investigations were based on short-term campaign monitoring data for selected locations (Jiang et al., 2024). For example, Hyde et al. (1981) suggested that local PM10 emissions in the valley can impact air quality in areas away from sources - that is, north-westerlies can transport dust generated in the upper end of the valley to areas near the bottom of the valley or further down over the metropolitan areas of Newcastle. SPCC (1982) reported the research findings from a few projects, which concluded that dust pollution from open-cut coal mining activities continued to be an issue of concern, and that there was unlikely to be serious region-wide pollution cumulations resulting from dust emissions from mines. Holmes and Associates (1996) suggested that the increase in dust levels in the valley over 1984-1994 were due to the increase in coal production and the severe drought conditions affecting much of east Australia, and that the land affected by cumulative effects appears to be primarily that owned by the coal mine companies. Later, based on data in 2012-2015 for 14 stations in the UHAQMN, Jiang (2017) explored the relationship between a dust (as PM10) risk metric and local meteorological variables using a lagged correlation analysis and the categorisation and regression tree (CART) method. It was found that the correlations between PM10 pollution and individual meteorological variables are complex and non-linear, varying with time and location. Drawing upon this finding, the author recommended that more sophisticated machine learning (ML) techniques such as the Kohonen self-organising map (SOM) method (Kohonen, 2001) can be useful for assessing the impact of weather and climatic conditions on local air quality in the region. The SOM method can be applied for both data classification (structure discovery) and data visualisation (interpretation of results), as was demonstrated for other regions by Jiang et al. (2016), Jiang et al. (2017a) and Jiang et al. (2013).

Till now, to the best of our knowledge there is little or no research in the literature on the topic of quantitatively examining how local and synoptic meteorological configurations combine to modulate the PM10 pollution in a valley environment, such as the Upper Hunter Valley. Jiang et al. (2024) identified the persistent existence of two distinct air quality clusters/subregions in the valley and further examined the temporal variability modes of PM10 pollution in these subregions. They found that higher pollution tended to occur in cooler months (late winter to spring) in the southeast (SE) subregion, but in warmer months (especially summer) in the west-northwest (WNW) subregion (also see

Section 2.1). The present paper extends Jiang et al. (2024), to report on a quantitative analysis of how elevated PM10 pollution in spring and summer (September to February) of 2012-2022 were associated with typical local and synoptic meteorological configurations over the valley. The analysis is featured with the visualisation and interpretation of complex results on the SOM planes, in a holistic and self-organised manner. The investigation is unique in at least four aspects: 1) a catalogue of 12 synoptic circulation types has been established for the study region for summer and spring seasons, when PM10 levels are generally higher; 2) for the first time a set of six typical local meteorological patterns has been quantitatively derived for the region for the same seasons; 3) the connections between independently derived local meteorological patterns and typical synoptic circulation types are established and analysed; and 4) the typical synoptic types and local meteorological pattens most conducive to elevated PM10 pollution are holistically identified for two largest population centres, Muswellbrook and Singleton, respectively representing the WNW and SE air quality subregions in the valley. The methodology and results can be used in air quality research for other locations in NSW, or similar regions elsewhere.

2. Data

2.1. Air Quality Data

Air quality data are available for 14 monitoring stations in the UHAQMN (Jiang et al., 2024). Based on daily PM10 measurements from these stations, previous studies have identified two distinct air quality subregions in the valley (network), one in the WNW part, the other in the SE part (Figure 2Figure

Figure 2; Jiang et al., 2024; Jiang, 2017). Hence, it is possible to characterise (summarise) the air quality

variability in the valley with PM10 pollution time series from a subset of (representative) monitoring stations in the subregions (Jiang et al., 2024). For easy interpretation of results, we chose to focus the present analysis on daily PM10 pollution at stations located at two largest population centres, Muswellbrook (population ~ 16,357) and Singleton (population ~ 24,577), respectively representing the WNW and SE air quality subregions in the valley.

Air quality data for the Singleton and Muswellbrook stations were obtained from the NSW Air Quality Data System (AQDS) for spring and summer of 2012-2022 (

Table 1). These included: 1) daily (24-hr) average PM10 concentrations (μg/m

3) for each monitoring station; and 2) information on whether and when PM10 measurements at any of the 14 stations in the UHAQMN were significantly impacted by exceptional events (definition in

Section 2.4) such as HRBs, bushfires or widespread dust storms. The PM10 data were confirmed of high quality, with a small missing data rate (1.6% or less) for spring and summer seasons at both stations.

2.2. Local Meteorological Data

Three sets of local meteorological data were obtained for this study (

Table 1). One main dataset was obtained from the NSW AQDS for the Singleton and Muswellbrook stations, including hourly measurements for 10 m horizontal wind, i.e., wind speed (m/s), wind direction (polar degree) and standard deviation of wind direction (SD1; in polar degree), and 4 m air temperature (ºC) and relative humidity (%) for 7:00, 13:00 and 19:00 AEST of each day in spring and summer of 2012-2022. The choice of three-time daily measurements for two stations was to capture (represent) the common diurnal variability in local meteorological conditions across the valley (Jiang, 2017). Wind speed and direction data were used to derive the west–east (u) and south–north (v) wind components, while SD1 records, as indicator of flow direction variability or disturbance, were converted into radians to facilitate the subsequent computations.

The other two datasets included measurements of daily rainfall totals (mm) at two town centres for the same seasons. The 24-hr rainfall records (previous day 9:00 am to current day 9:00 am AEST) were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) for 2012-2018 at Singleton (station number 061397; 32.59° S, 151.17° E), and for 2012-2022 at Muswellbrook (station number 061374; 32.22° S, 50.92° E) (

Table 1). There were large missing data gaps for the 2019-2022 period, especially at the Singleton station due to site decommissioning. Hence, we also extracted rainfall data from the NSW AQDS for the Singleton and Muswellbrook air quality stations, where rainfall monitoring commenced during late 2016 and early 2017, respectively. For stations located in the same town, there are high correlations between the BOM and AQDS rainfall data for the common period (2016-2018). Hence, the AQDS rainfall data were used to fill in the missing data gaps in the BOM rainfall time series for each site. The improved rainfall dataset was then used to form daily time series for two new variables, indicating soil moisture status and pollution wet deposition process in the valley. The 24-hr rainfall record from the previously day 9 am to the current day 9 am AEST was used as proxy variable indicating the soil moisture status in the previous day, since observational soil moisture data were not available at the time of this study. The 24-hr rainfall record from the current day 9 am to the following day 9 am AEST was used as weather variable indicating the change in soil moisture (hence potential for dust emissions) and wet deposition process during the current day. This treatment was applied to each site separately, and the resulting dataset for the new variables was combined with the three-time daily meteorological measurements for two air quality stations, to form the final local meteorological dataset. The final dataset was used in the SOM classification procedure to quantitatively derive a catalogue of typical local meteorological patterns prevailing in spring and summer (

Section 3.1), when PM10 pollution are found to be relatively high.

2.3. Gridded NCEP/NCAR Geopotential Height Data

The data used for the SOM-based synoptic type classification consist of daily 0000 UTC (10:00 AEST) NCEP/NCAR 1000 hPa geopotential height reanalysis for November–February (spring-summer) in 2012–2022 (Kalnay et al., 1996). The study domain covers latitudes 15–50oS and longitudes 130–170oE at a 2.5o × 2.5o resolution, being the same as those used in the previous classifications by Jiang et al. (2015) and Jiang et al. (2017a, b). It is considered sufficient to capture the major synoptic features influencing east Australia.

2.4. Exclusion of Exceptional Events and Definition of Elevated Pollution Days

Jiang et al. (2024) defined exceptional event days as those when air quality in the Upper Hunter Valley was significantly impacted by air emissions from bushfire, planned hazard reduction burning (HRB) and/or continental-scale dust storm, with daily PM10 levels above the 24-hr average national benchmark level of 50 µg/m3 (NEPC, 2021) at one or more stations in the UHAQMN. We continue to use the definition in this text, so that of the total 1994 days for spring-summer in 2012-2022, there were 111 exceptional events days identified (5.6%). The exceptional event days were excluded from the daily PM10 dataset for further analysis, so that the investigation was focused on PM10-meteorology relationships on non-exceptional event days, i.e., normal days which were impacted mainly by local emissions sources such as coal mining activities and wind driven soil erosion (as is of most concern in local communities).

The present study was intended to focus on analysing the linkage of meteorological configurations with elevated PM10 pollution in the study region. A day was marked as elevated pollution day if PM10 concentration on that day was above 33.5 µg/m3, i.e., over 67% of the national standard (50 µg/m3) for daily average PM10 levels. This definition led to a derived dataset with elevated PM10 pollution days only, respectively for the Singleton (total: 178 days) and Muswellbrook (total: 210 days) air quality stations. The use of data for elevated PM10 pollution days, rather than that for poor air quality (exceedance) days defined in Jiang et al. (2024), was to ensure that the sample sizes are sufficiently large to produce meaningful results from the present analysis. The terms “PM10 pollution” and “air pollution” are used in an exchangeable manner in this text.

3. Methodology

The investigation was conducted in three steps, focusing on the linkage between the occurrence of PM10 pollution on normal days (i.e., non-exceptional event days) with the local- and synoptic-scale meteorological conditions in spring and summer. As noted in

Section 2.4, the exceptional event days were excluded from the daily PM10 dataset in the analysis, so that the investigation was focused on understanding the PM10-meteorology relationships on

normal days, which were impacted mainly by local emissions sources such as coal mining activities and wind driven soil erosion (which are of most concern in local communities).

In the first step (

Section 3.1), we determined the prevailing synoptic and local meteorological features by applying the SOM method to the NCEP/NCAR 1000 hPa geopotential height reanalysis (

Section 2.3) and the daily local meteorological dataset (

Section 2.2), respectively. In the second step, we examined the connections between synoptic circulation types and local meteorological patterns, based on the classifications resulting from the previous step. The output facilitates the interpretation of results in the third step. The third step was to identify which typical synoptic types and/or local meteorological patterns were most conducive to mean and elevated PM

10 pollution in the valley (

Section 3.2). For easy interpretation, as noted earlier, the analysis was conducted for two larger population centre stations, Singleton and Muswellbrook, each representing one of the air quality subregions (Figure 2Figure

Figure 2; Jiang et al., 2024). The relationships between mean and elevated PM10 pollution and meteorological configurations were holistically visualised and examined on the SOM planes.

3.1. Application of the SOM Technique

There are many classification methods available in the literature (Huth et al., 2008; Philipp et al., 2016). Kohonen’s self-organising map, often referred to as SOM in the literature, is one of the most popular neural network methods for unsupervised, non-linear data classification and visualisation (Jiang et al., 2015). SOM maps the high-dimensional data points (e.g., weather maps) from the input data space onto the nodes (representative patterns, e.g., synoptic types) of a low-dimensional (typically 2-D) grid. In general, SOM mapping can often be conducted two different ways, through sequential (incremental) or batch training. The two training methods essentially produce the same or similar results, with the batch training converging significantly faster than the sequential training (Kohonen, 2001). The batch training method is relatively simple to apply (with no learning rates involved), and less sensitive or insensitive to the order of data presentation and map initialisation (Vesanto et al., 2000; Jiang, 2010).

The utility of a two-phase batch SOM procedure (CP2) for classification of circulation types over east Australia was demonstrated in a few early studies (e.g., Jiang, 2010; Jiang et al., 2012; Crawford et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2015). General details on the implementation of CP2 can be found in Jiang et al. (2012) or Jiang et al. (2015). In brief, the first phase is to capture a rough estimation of the global structure in the data, and the second phase fine-tunes the mapping to achieve balanced local vs global optima and thus obtain the final data groupings. CP2 can be run in either data clustering or projection mode - in this study we applied CP2 in clustering mode, aiming to identify distinctive local and synoptic features influencing the study region. Further details on the CP2 application in this study are given in the following sections.

3.1.1. Classification of Synoptic Types

CP2 was applied to the daily NCEP/NCAR 1000 hPa geopotential height reanalysis for September to February, 2012-2022 (

Section 2.3) to classify the dominant synoptic circulation types influencing east Australia (including the Upper Hunter Valley). A map size (i.e., total number of nodes/types on the SOM grid) needs to be assigned in the SOM mapping process. We chose to train a 4x3 SOM mapping (i.e., 12 synoptic types) from the present dataset, following Jiang et al. (2017a, b). A geopotential height map was assigned to a SOM node (synoptic type) from which it has the smallest squared Euclidean distance. A synoptic catalogue was then constructed by allocating each 1000 hPa geopotential height map to one of the 12 types on the SOM obtained.

3.1.2. Classification of Local Meteorological Patterns

Similarly, CP2 was applied to the local meteorological dataset (

Section 2.2) to identify the representative local meteorological patterns prevailing in the Upper Hunter Valley during spring and summer. CP2 was implemented on standardised time series, since individual variables were measured in different units (then with de-standardisation applied the final nodes afterwards to obtain the final classification). Several SOM map sizes were considered for the present dataset. Balancing the need for parsimony and variety, the 3x2 SOM mapping (i.e., 6 patterns) was found sufficient to reproduce the main meteorological configurations identified in local meteorological experience (e.g., Jiang, 2017; Holmes, 2008). Hence, for the first time a catalogue of six local meteorological patterns was quantitively derived for the study region, with each being interpreted in terms of the combination of individual meteorological variables.

3.1.3. Ordered Visualisation of Complex Results on the SOM Plane

An important property of the SOM mapping is related to the topologically ordered display of the input data in the output space – that is, similar data items from the input space are projected onto the nearby SOM nodes and dissimilar data items onto the SOM nodes further apart. Consequently, the resulting synoptic types (or local meteorological patterns) from the SOM classification are expected to be self-organised/structured on the SOM planes (details in

Section 4.1 and 4.2). This property facilitates the visualisation and interpretation of the complex meteorology-air quality pollution relationships on the SOM planes in a structured/clustered manner, as was also demonstrated in studies for other regions by Jiang et al. (2017a), Jiang et al. (2016) and Jiang et al. (2013).

3.2. Air Pollution Tendency Measures

The tendency for PM10 pollution was examined in terms of mean PM10 concentrations and the frequency and propensity for elevated pollution days at the Singleton and Muswellbrook stations, under the occurrence of individual synoptic types, local meteorological patterns, or their combinations.

Mean PM10 levels were calculated as average loadings on each synoptic type or local meteorological pattern. Larger mean values indicate higher overall tendency/potential of the related synoptic type or local pattern for leading to high PM10 pollution in the valley subregions, and vice versa.

Frequency of occurrence for elevated PM10 pollution days was also calculated to reveal how often elevated PM10 pollution events could occur, conditional to the occurrence of individual synoptic types, local meteorological patterns, or the pattern-type combinations. This frequency was expressed as the percentage of days when a local pattern (synoptic type, or pattern-type combination) occurred over the total number of elevated pollution days for the examined station.

Propensity ratio was used to indicate pollution conduciveness of individual synoptic types, local meteorological patterns, or the pattern-type combinations. Following Green et al. (1999), the propensity ratio was expressed as a ratio of the percentage of elevated pollution days for each local pattern (synoptic type, or pattern-type combination) to the overall (climatological) percentage of occurrence of that pattern (synoptic type, or pattern-type combination) in the whole normal-day dataset for spring and summer of 2012-2022. A ratio value greater than one indicates that the local meteorological pattern (synoptic type, or pattern-type combination) is more likely to be present on days of elevated pollution levels than expected. The values of propensity ratios are presented together with frequencies to provide insights into the conduciveness of specific meteorological configurations for leading to elevated PM10 pollution in the valley.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Dominant Synoptic Types in Spring and Summer

The CP2 (batch SOM procedure) determined a set of 12 synoptic (circulation) types (T1~T12), with similar types close to each other and distinct types further away on the SOM grid/plane, approximating the full spectrum of synoptic states influencing east Australia in spring and summer (

Figure 3a). As expected, the classification captures well the interactions among three major synoptic features, i.e., subtropical/continental high, easterly trough/thermal low and westerly trough/frontal system (Sturman and Tapper, 2008).

On a broad scale, synoptic types near the top-left corner and top edge of the SOM are more frequent in spring (

Figure 3a,b), featured with a high system centred over the southern continent near the Australian Bight or a ridge extending northwest from central/northern Tasman Sea towards southern Queensland, as well as the influence of passing westerly troughs (frontal systems) in the further south. In contrast, the situations near the bottom-right corner of the SOM grid show greater prominence in summer (

Figure 3a,c), characterised by the influence of a southern high pressure system (centred over the southern ocean or southern Tasman Sea) and a thermal low/easterly trough system extending southward from northern Queensland. Also of note is that the westerly trough type(s) near the bottom-left corner and the southern high type(s) on the top-right corner of the SOM could occur in both spring and summer (

Figure 3b,c). These results are consistent with previous synoptic catalogues for the same region, e.g., by Jiang et al. (2012), Jiang et al. (2015) and Jiang et al. (2016) for earlier years.

4.2. Prevailing Local Meteorological Patterns in the Upper Hunter Valley

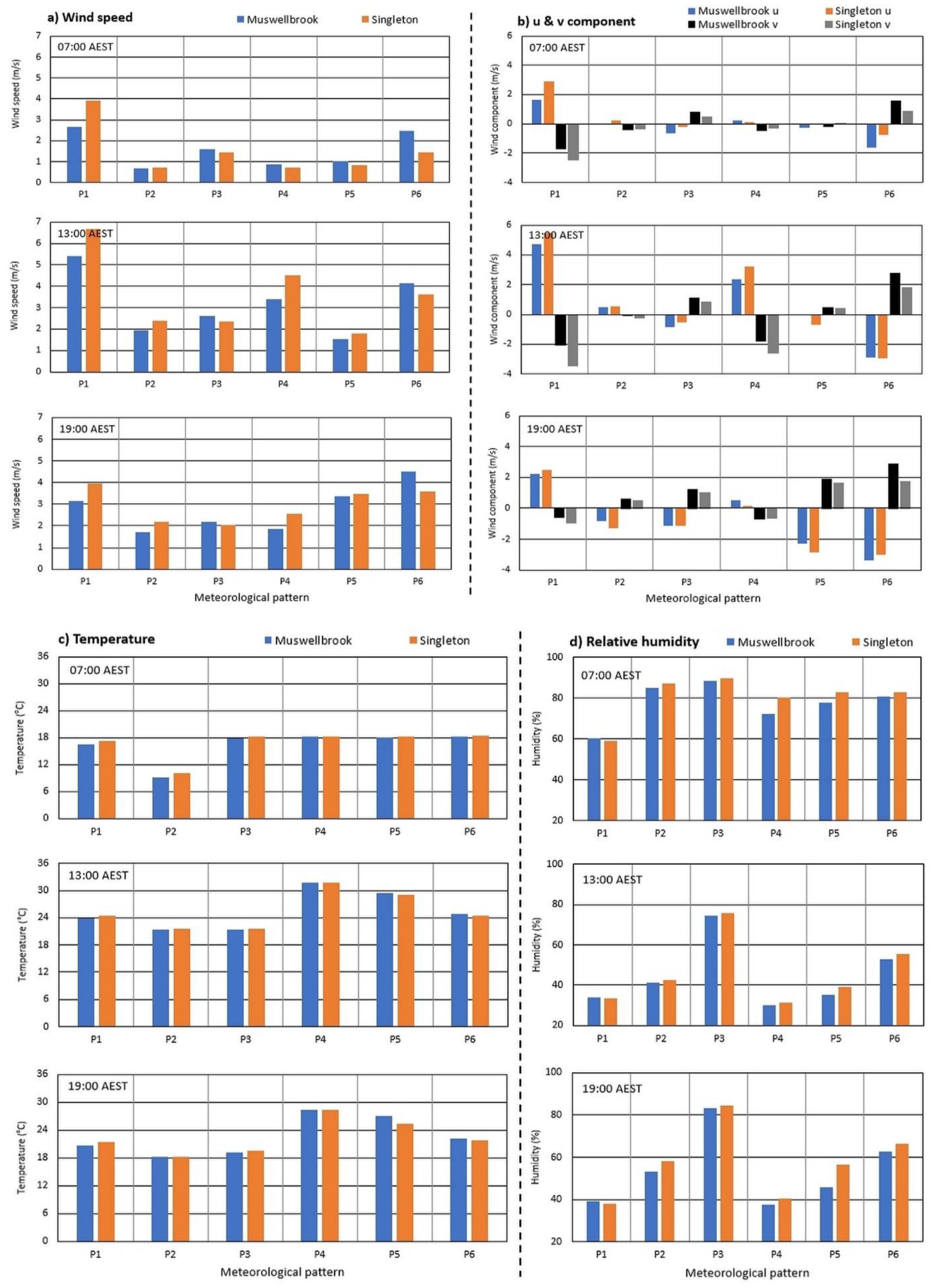

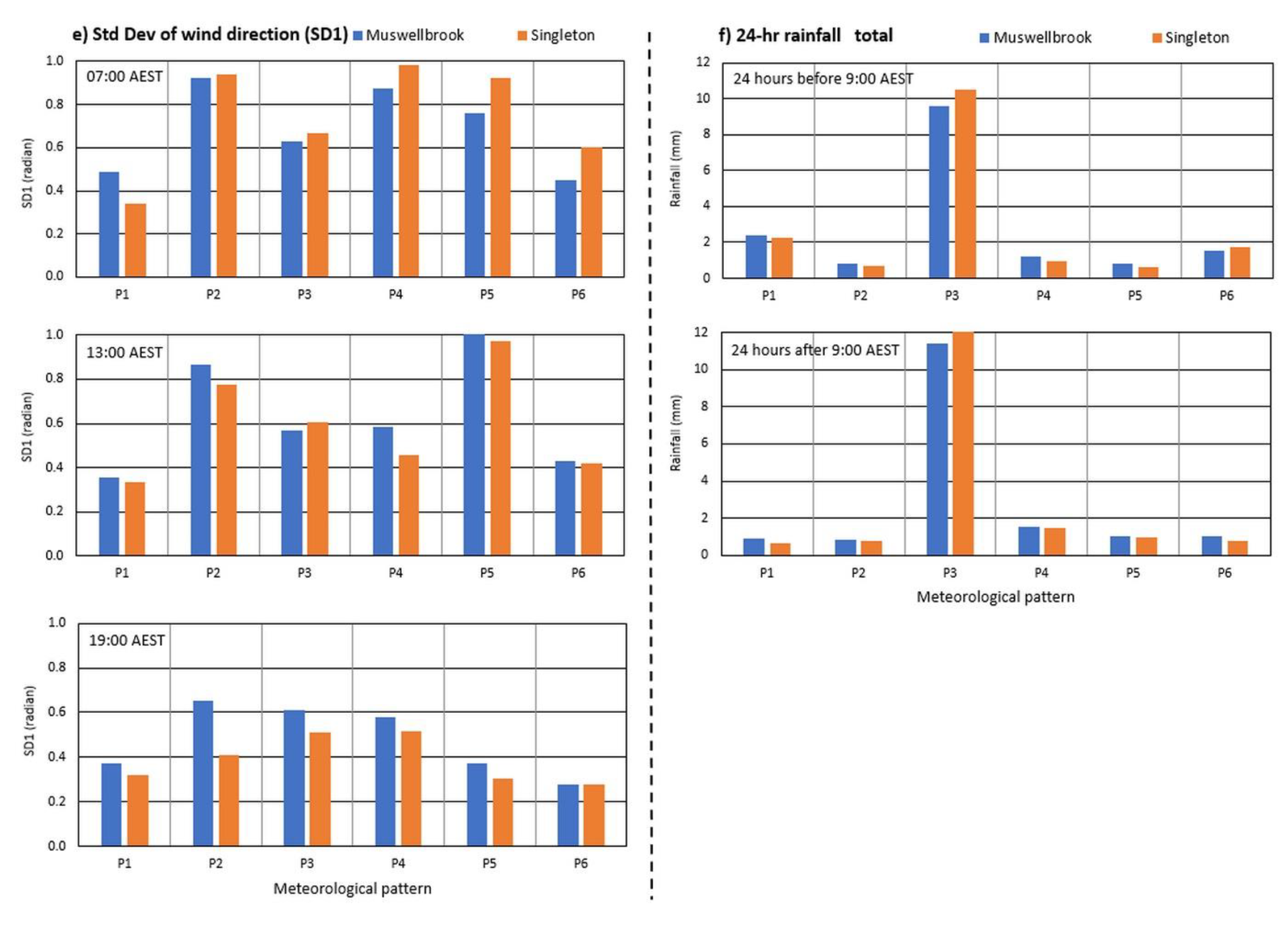

For the first time, a classification of typical local meteorological patterns has been quantitatively derived for the Upper Hunter Valley using the SOM method and based on the long-term data for multiple meteorological variables from the UHAQMN. The classification identified six local meteorological patterns (P1~P6) for the valley, with the mean meteorological conditions for individual patterns being illustrated in

Figure 4 and further summarised/visualsised on the 3x2 SOM grid/plane in

Figure 5. Notably P1~P6 are also topologically ordered on the SOM plane, with distinct patterns located on the opposite corners and more similar ones in the middle section.

The most frequent patterns are P5 (23.6%) and P6 (25.8%), being more prevalent in summer (

Figure 4c) and charactered by hot-dry-calm conditions (P5) or humid weather with strong southeasterly (SE) winds (P6). The second most frequent patterns are P2 (16.4%) and P4 (17.6%), with P2 predominantly occurring in spring and P4 equally prevalent in both seasons (

Figure 4b,c). These patterns are characterised by: (1) cold-dry-calm conditions with potential for night-time or early morning inversion and down-valley drainage flows (P2); or (2) hot and dry weather with prevalence of northwesterly (NW) winds potentially of continental origin (P4). The least frequent patterns are P1 (8.1%) and P3 (8.6%) respectively on the top-left and bottom-left corners of the SOM grid, typical of dry (and cool) conditions associated with prevalence of strong NW winds (P1) or very humid and wet weather associated with moderate SE flows (P3). P1 was more frequent in spring, while P3 was equally prevalent in both seasons.

In summary, all local patterns could occur in spring, with P2 (cold-dry-calm) most prevalent, while P5 (hot-dry-calm) and P6 (humid-strong SE wind) were more often observed in summer. This seasonal difference is somewhat expected due to the seasonal changes in prevailing synoptic circulations described in

Section 4.1 and the potential for increased activities of local or meso-scale circulations (such as sea breezes) from spring to summer, as will be further discussed in

Section 4.3. Overall, these quantitatively identified local meteorological patterns reflect well the typical meteorological configurations experienced in the study region, for example, those described in Bridgman and Chambers (1981) and Hyde et al. (1981) based on short-term campaign (monitoring) projects, and in Jiang (2017) on the data in 2012-2015 for selected stations from the UHAQMN.

4.3. Relation of Local Meteorological Patterns to Synoptic Circulation Types

Early meteorological studies for the Upper Hunter Valley provided

qualitative descriptions on how local meteorological variables were related to synoptic situations based on short-term campaign monitoring data (e.g., Hyde et al., 1981). Here, the connections between local meteorological patterns and synoptic circulation types (described in

Section 4.1 and 4.2 respectively) can be quantitatively visualised in a holistic framework, by taking advantage of the topologically ordered display of the mapping nodes (i.e., patterns and types) on the SOM planes.

Figure 5 shows the relative frequency of occurrence for individual synoptic types, conditional to the occurrence of each local meteorological pattern. The main findings are summarised below:

P1 (dry-strong NW wind) are mostly related to the occurrence of synoptic types T2~T4 and secondarily T1 (i.e., anticyclonic/westerly trough types, indicated by relatively high frequencies clustered on the left edge of the 4x3 SOM grid), often in spring and commonly featured with the influence of eastward migrating continental high and westerly trough systems, which are often accompanied by the passage of frontal systems over the southern part of the continent (Sturman and Tapper, 2008). To a much lesser degree, this meteorological pattern is also associated with synoptic types T6~T8, characterised by a high-pressure ridge extending northwest from the central or northern Tasman Sea towards coastal northern NSW or southern Queensland. All these synoptic types tend to provide southwesterly to northwesterly synoptic flows (i.e., flows with westerly component) over the study region, facilitating the prevalence of strong northwestely winds in the valley.

P2 (cold-dry-calm) corresponds more often to synoptic types T1, T5 and T6, and secondarily T2 and T9 (i.e., anticyclonic types, indicated by high frequencies clustered near the top-left edge in the 4x3 SOM grid), predominantly in spring and commonly characterised by the influence of a strong anticyclonic system over the southern part of the continent, the central/northern Tasman Sea or over Tasmania, with the potential for providing synoptic-scale light wind or calm conditions over the study region. These types can lead to anticyclonic atmospheric descending and night-time radiative cooling, thus resulting in the occurrence of night-time or early morning planetary boundary layer inversion, down-valley (NW) drainage flows and/or low early morning ambient temperatures in the region.

P3 (very humid-wet-SE wind) corresponds mostly to the occurrence of T9, T11 and T12 and secondarily T6~T8 and T10 (i.e., thermal low/southern high types, indicated by high frequencies clustered near the bottom-right corner and right edge of the 4x3 SOM grid), relatively more often in summer and commonly associated with the influence of a thermal low/easterly trough in the northwest and a high pressure system centred in the south of the domain. These situations can provide synoptic flows with easterly components, broadly facilitating the occurrence of easterly to northeasterly sea breezes over coastal NSW and thus bringing abundant moisture or rainfall over the study region.

P4 (hot-dry-NW wind) corresponds mostly to the situations T7 and T3, and secondarily T2, T6 and T6 (i.e., northwest ridge types, indicated by high frequencies clustered on the middle to bottom-left sections of the 4x3 SOM grid). These synoptic types could occur in both seasons, commonly characterised by a ridge extending towards coastal northern NSW or southern Queensland from the central/northern Taman Sea, a westerly trough in the further south and potentially a thermal trough extending southward from northern Queensland. These situations can facilitate westerly to northwesterly synoptic flows of continental origin, which transport hot and dry air from inland (central) Australia over the study region, with a potential for causing the local occurrence of heat waves.

P5 (hot-dry-calm) corresponds mostly to T7, T10 and secondarily T2, T6, T8, T9, T11 and T12 (i.e., thermal low/southern high/northwest ridge types, indicated by high frequencies clustered near the bottom-right corner of the 4x3 SOM grid), most often in summer and commonly characterised by the influence of a thermal low trough extending over NSW from northern Queensland and a high-pressure system centred further south over the (southern) Tasman Sea or near the Australian Bight. These situations tend to provide calm conditions or light northerly to easterly synoptic flows over the coastal regions, resulting in hot, dry and calm conditions in the valley.

P6 (humid-strong SE wind) corresponds mostly to T11 and secondarily T8~T10 and T12 (i.e., thermal low/southern high types, indicated by high frequencies clustered near the bottom-right corner and the right edge of the 4x3 SOM grid), more often in summer and commonly featured with a thermal/easterly trough in the northwest and a high-pressure system located in south that often manifests ridging effects over the east coast. These situations often provide synoptic flows with easterly components and to some degree favour the occurrence of easterly sea breezes over coastal NSW, thus leading to the prevalence of strong SE winds in the study region.

Figure 6.

Linking local meteorological patterns with synoptic types on the SOM planes: relative frequency (%) of 12 synoptic types (T1~T12) on the 4x3 SOM grid as in

Figure 3, under the occurrence of each local meteorological pattern (P1~P6) in September- February displayed on the 3x2 SOM grid. Colour scale: green - low value; yellow - medium value; red - high value.

Figure 6.

Linking local meteorological patterns with synoptic types on the SOM planes: relative frequency (%) of 12 synoptic types (T1~T12) on the 4x3 SOM grid as in

Figure 3, under the occurrence of each local meteorological pattern (P1~P6) in September- February displayed on the 3x2 SOM grid. Colour scale: green - low value; yellow - medium value; red - high value.

Overall, the type-pattern relationships are generally consistent with general meteorological principles for valley environments (Sturman and Tapper, 2008). In summer, the prevalent patterns P5 (hot-dry-calm) and P6 (humid-strong SE wind) are more frequently associated with the occurrence of synoptic states featured with activities of southern highs and/or thermal low/easterly troughs, which facilitate anticyclonic low-wind (calm) conditions or the prevalence of easterly synoptic flows over the study region. In spring, the most prevalent pattern P2 (col-dry-calm) corresponds frequently to the occurrence of anticyclonic situations characterised by the influence of high-pressure systems centred over the southern continent or the Tasman Sea. All other pattern-type combinations are also observed, to a lesser and varying degree in this season. It is notable that each local pattern corresponds to a subset of synoptic types which are somehow similar and clustered together (close to each other) on the SOM plane, and vice versa. Essentially, this non-unique pattern-type correspondence reflects the complexity and subtleness in the interactions between local terrains and atmospheric circulations, which are constantly evolving, rather than exist in a form of discrete clusters. This finding highlights the significant role of local topographical factors in determining the prevailing meteorological conditions in the valley.

4.4. Relation of Synoptic Circulation Types and Local Meteorological Patterns to PM10 Pollution

We now examine the linkages between elevated PM10 pollution and the local meteorological patterns and synoptic types identified for spring and summer. Jiang et al. (2024) suggested that it is possible to characterise the air quality

variability in the Upper Hunter airshed with PM10 time series from a subset of (representative) monitoring stations in the air quality subregions (

Figure 2;

Section 2.1). Here we chose to analyse the pollution tendency and conduciveness of meteorological configurations in terms of mean PM10 levels and the occurrence of elevated PM10 pollution days at two larger population centre sites, Singleton and Muswellbrook, respectively representing the SE and WNW subregions in the valley.

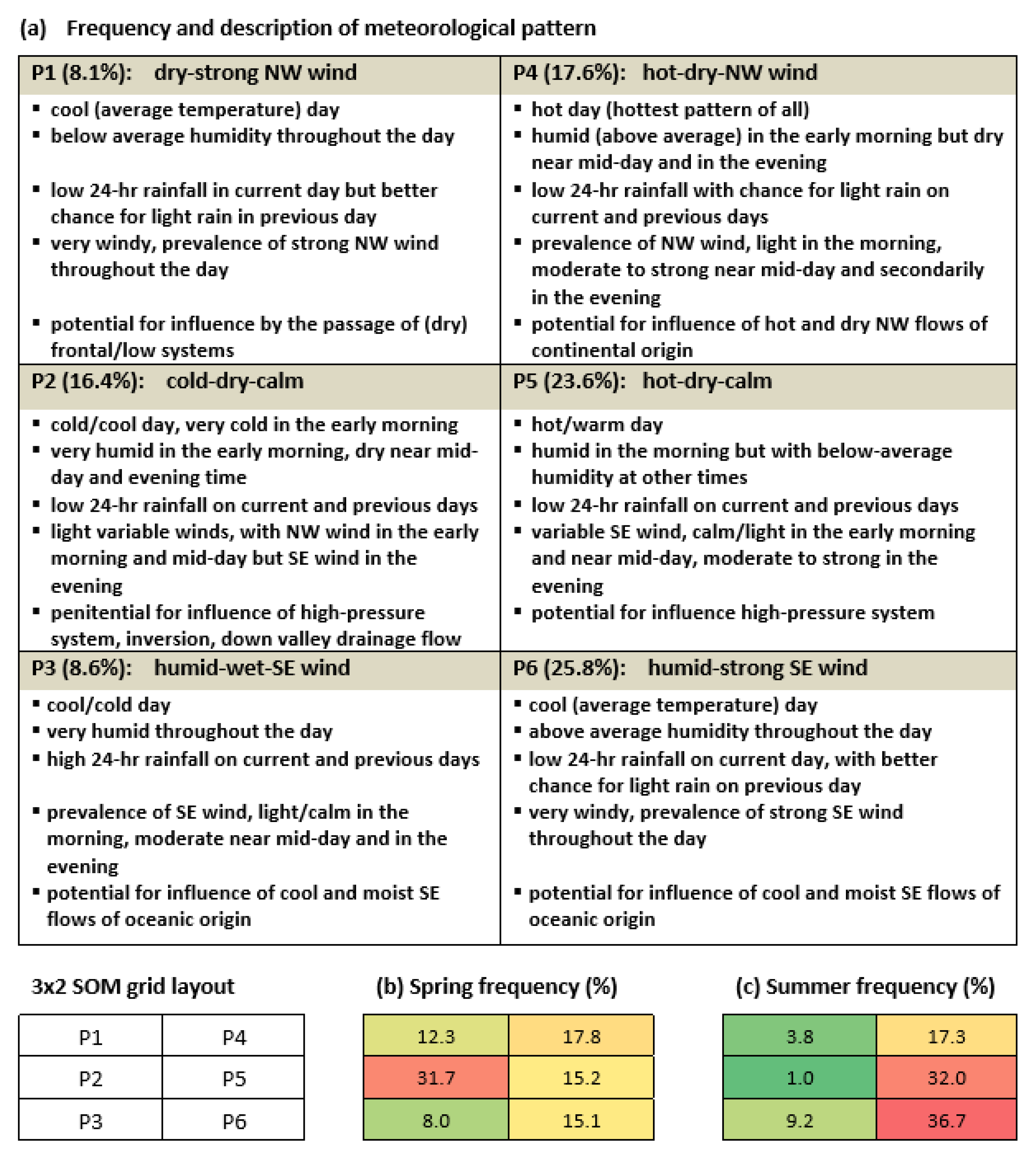

4.4.1. Mean PM10 Pollution Levels under Each Local Meteorological Pattern or Synoptic Type

Mean PM10 concentrations are shown in

Figure 7, illustrating the overall tendency of individual synoptic types or local meteorological patterns for contributing to PM10 pollution in the SE and WNW subregions, as represented by the Singleton and Muswellbrook stations, respectively. The clustered patterns of the PM10-meteorology relationships are readily identifiable on the SOM planes. Overall, these relationships are consistent with local air quality experience, for example, those reported in Jiang (2017), Holmes (2008) and Holmes and Associates (1996) for the Upper Hunter Valley, and in Jiang et al. (2017a) and Leighton and Spark (1997) for Sydney.

Of the six local meteorological patterns, P1 (dry-strong NW wind) and secondarily P4 (hot-dry-NW wind) correspond to much higher mean PM10 levels at both stations (

Figure 7a). Local experience suggests that dry NW winds contribute to increased dust generation and down-valley transport of air pollutants, and hence elevated mean PM10 concentrations at the lower part of the valley (Jiang, 2017). Moderately high PM10 levels are observed under P2 (cold-dry-calm) at Muswellbrook and to a lesser degree at Singleton, probably associated with the effect of reduced dust generation (due to suppressed NW wind conditions) confounded by the impact of pollutant accumulation due to low valley ventilations that limit pollutant transport and dispersion. In contrast, P6 (humid-strong SE wind) correspond to the lowest mean PM10 pollution at Singleton and Muswellbrook, since the SE local winds tend to transport pollutants up-slope while also suppressing PM10 accumulation due to high wind speeds (good ventilation).

However, P3 (humid-wet-SE wind) and P5 (hot-dry-calm) tend to play different roles in determining pollution levels at the two stations (subregions). P3 corresponds to relatively low mean PM10 pollution at Singleton but high mean PM10 levels at Muswellbrook, since the prevailing SE local winds tend to transport pollutants up-slope (away from Singleton, i.e., the SE subregion of the valley), leading to PM10 accumulating near the Muswellbrook area (i.e., in the WNW subregion in the upper part of the valley). P5 is associated with relatively high mean PM10 levels at Singleton, but low mean PM10 levels at Muswellbrook, resulting from the effects of reduced dust generation (under suppressed wind conditions) and lack of up-slope pollutant transport (towards the upper end in the WNW subregion), confounded by the impact of pollutant accumulation due to low ventilation conditions. These between-site (subregion) variations in the PM10-local meteorology relationships essentially reflect the significant role of local meteorological conditions in determining the two distinct air quality conditions in two subregions described in Jiang et al. (2024).

The mean PM10-synoptic type relationships tend to be similar for Singleton (the SE subregion) and Muswellbrook (the WNW subregion) (

Figure 7b). Synoptic types associated with higher mean PM10 levels include T2~T4 and T6 and T7 (highest mean PM10 levels on T4), i.e., those clustered near the bottom-left conner on the 4x3 SOM grids and characterised by the influence of a high system centred over the continent near the Australian Bight, a westerly trough in the south, and/or a ridge extending northwest towards coastal northern NSW or southeastern Queensland from the Tasman Sea. These situations are known to provide relatively strong southwesterly to northwesterly synoptic flows over eastern NSW (Jiang et al., 2016), thus facilitating the occurrence of local NW winds in the valley (

Section 4.3). The local NW winds can enhance dust generation (through soil erosion) and down-valley pollutant transport, hence contributing to elevated mean PM10 pollution across the valley. These relationships are somewhat consistent with Jiang et al. (2017a), who showed that the passage of low pressure or frontal systems, and the presence of a high-pressure cell over the Tasman Sea with a ridge extending north-west across NSW or southern Queensland are commonly associated with elevated PM10 pollution levels and high chance for exceedance days during warm seasons (November to March) in Sydney.

In contrast, the synoptic states featured with the activity of southern high-pressure systems (T9~T12 on the right edge of the SOM) are related to generally lower mean PM10 concentrations at both stations. This is because these systems often provide mild, moist easterly synoptic flows of oceanic origin, locally in favour of the occurrence of wet weather and hence (potentially) resulting in suppressed local PM10 emissions. However, of note are T10 and T11, under which mean PM10 concentrations at Muswellbrook are significantly higher compared to that at Singleton. This is expected, since these southern high/easterly trough types facilitate the occurrence of easterly to southeasterly flows in the study reason (

Section 4.3), thus in favour of transporting air pollutants from the bottom end (SE subregion) to the upper end (WNW subregion) of the valley. The between-site variations in the PM10-synoptic type relationships indicate the combined influence of synoptic circulations and local meteorological conditions in discriminating mean air quality conditions in two subregions of the Upper Hunter Valley. This aspect will be further discussed in the next two subsections.

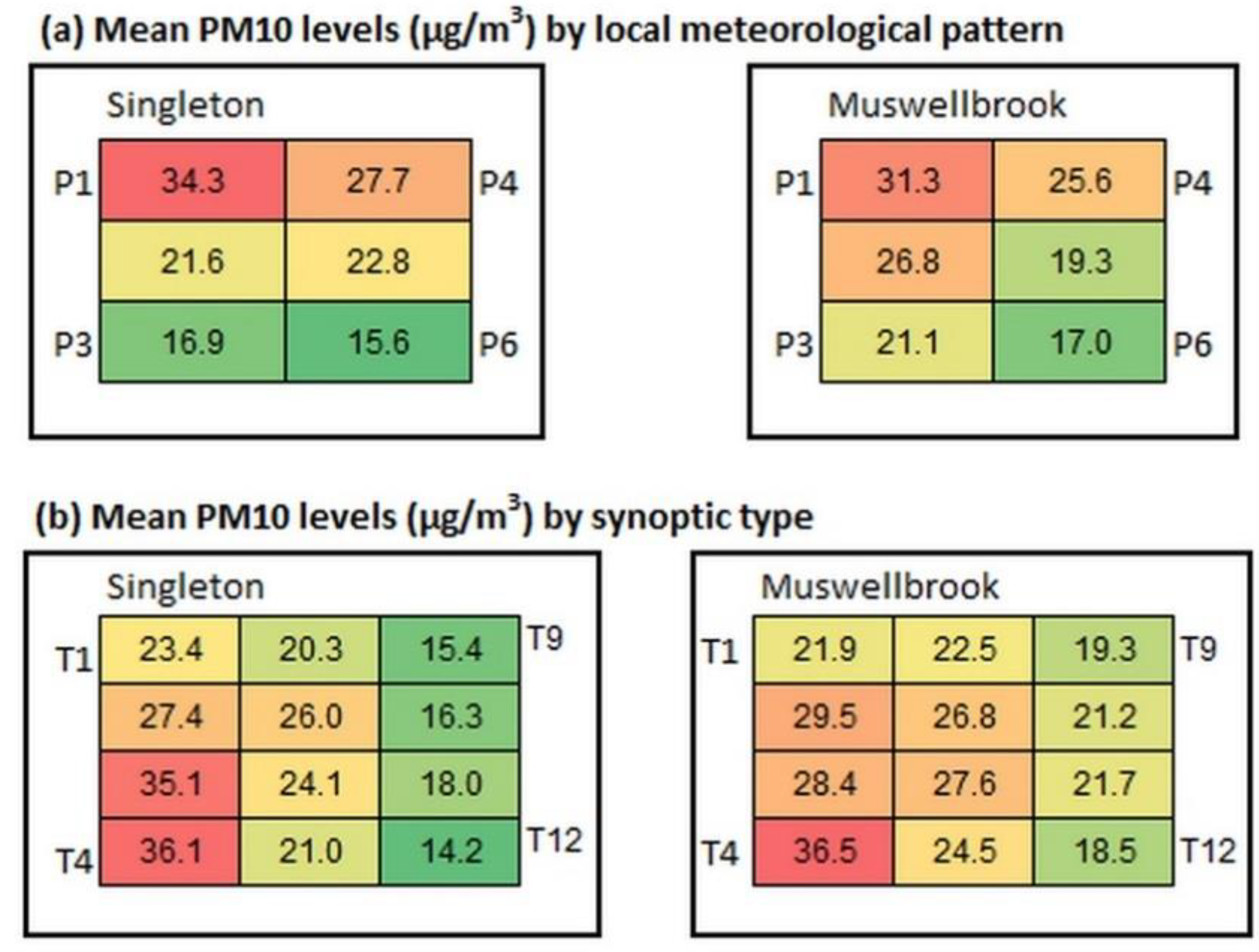

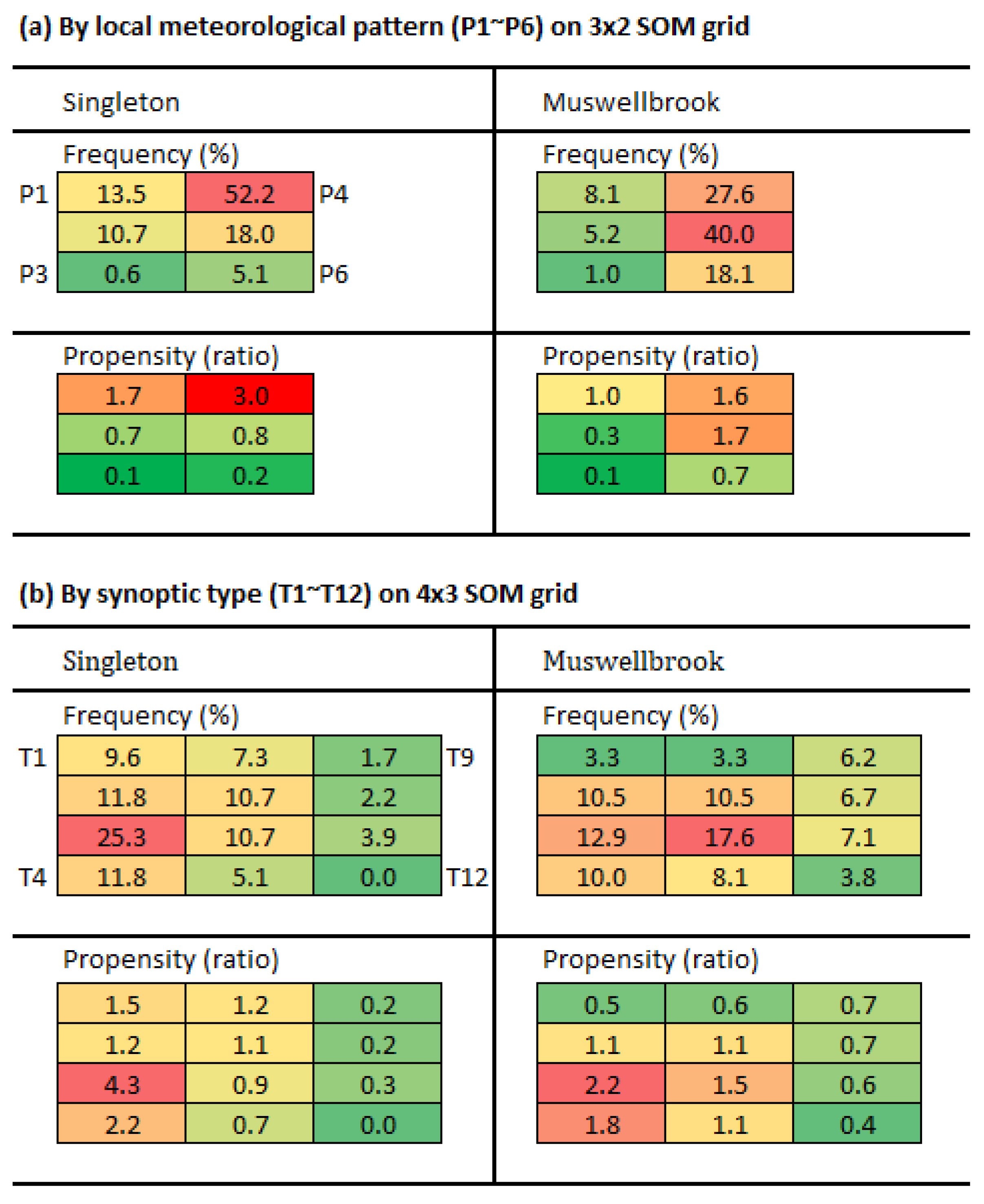

4.4.2. Linking the Occurrence of Elevated Pollution Days to Local Meteorological Patterns or Synoptic Types

It is high pollution days that are of most concern in air quality management. In this section, we examine the tendency of individual local meteorological patterns (P1~P6) or synoptic types (T1~T12) for leading to elevated pollution days at Singleton and Muswellbrook. The frequency and propensity ratio values are given on the SOM planes in

Figure 8 for P1~P6 and T1~T12, respectively. As noted in

Section 3.2, a higher frequency (%) value indicates higher probability for a local pattern (or synoptic type) being observed on an elevated pollution day at the examined station, and vice versa. A propensity ratio greater than

one indicates that the relevant local pattern (or synoptic type) is more likely to be present on elevated PM10 pollution days than climatologically expected.

Of the six local meteorological patterns (

Figure 8aa), P4 (hot-dry-NW wind conditions) and P5 (hot-dry-calm conditions) show the highest frequencies (probabilities) for leading to elevated PM10 pollution, accounting for 70.2% and 67.6% of the total elevated pollution days at Singleton and Muswellbrook, respectively. Patterns with moderate probabilities are P6 (humid-strong SE wind; 18.1%) for Muswellbrook and P1 (dry-strong NW wind; 13.5%) for Singleton. In comparison, the propensity ratios illustrate somehow different distribution patterns on the SOM grid. The most pollution conducive patterns are P4 and P1 for Singleton, and P4 and P5 for Muswellbrook, together highlighting the high tendency of the hot-dry-NW wind conditions (P4) for leading to elevated PM10 pollution events in both subregions (in the valley). As expected, P3 (humid-wet-SE wind) has the lowest propensity ratio values and is thus least conducive to elevated PM10 pollution events among all patterns. The between-site variations in relationships further highlight the different roles of local meteorological conditions in modulating elevated PM10 pollution across two air quality subregions. The distribution patterns in frequencies and propensity ratios somehow differ from those for mean PM10 concentrations shown in

Section 4.4.1. This is an important finding, as it implies that local meteorological configurations tend to play different roles in determining the mean PM10 levels vs the occurrence of elevated pollution episodes in two subregions.

As shown in

Figure 8b, the synoptic types on the centre to left section of the SOM plane are most probably related to the occurrence of elevated PM10 pollution days, with T2~T4 and T6~T7 accounting for a total of 79.8% and 64.8% of elevated pollution days at Singleton and Muswellbrook, respectively. Of these, T3 and T4 have the highest propensity ratios for both sites, hence commonly most pollution conducive in two subregions. In addition, relatively high propensity ratios also occur to T1 at Singleton and to T7 at Muswellbrook. These pollution-conducive synoptic types are characterised by the influence of a strong high-pressure system centred near the Australian Bight (T1 and T2), or the passage of a westerly trough or frontal system and a ridge extending northwest towards northern NSW or southeast Queensland from a high centred over the Tasman Sea (T3, T4, T6, T7) (

Section 4.1). In contrast, synoptic types T9~T12, characterised by a high-pressure system centred to the south or southeast of the continent with a potential for facilitating easterly synoptic flows over the study region, appear least conducive to elevated pollution days in the valley. In other words, these situations were often associated with relatively better air quality in the valley, more so at Singleton (the SE subregion) than Muswellbrook (the WNW subregion). Overall, synoptic types show similar relationships with the occurrence of elevated PM10 pollution days to that with mean PM10 concentrations discussed in

Section 4.4.1.

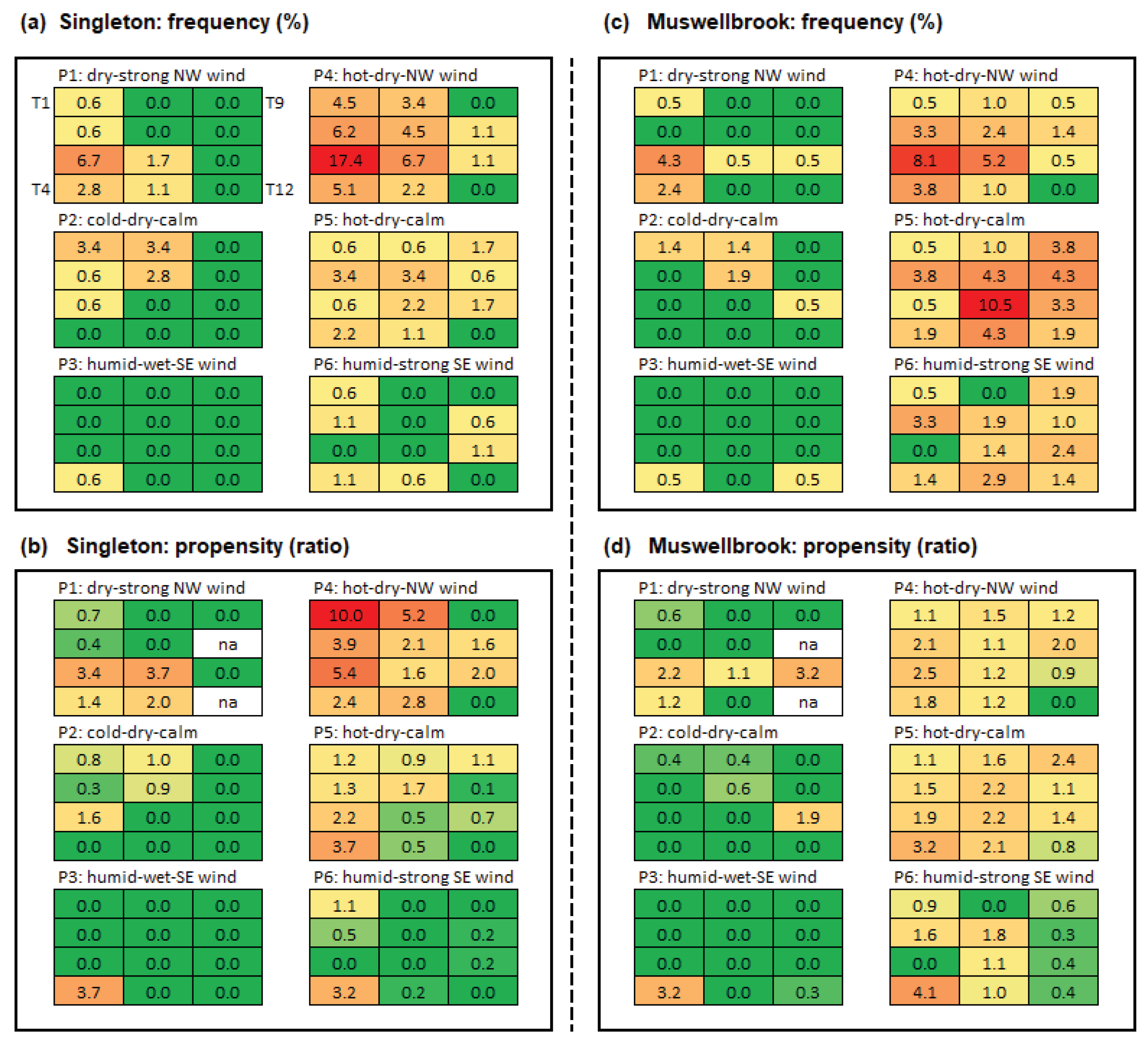

4.4.3. Linking the Occurrence of Elevated Pollution Days to the Local Pattern-Synoptic Type Combinations

The tendency of meteorological configurations for leading to elevated PM10 pollution days is further illustrated in nested SOM grids, as shown in

Figure 9 in terms of frequency and propensity ratio for the local meteorological pattern-synoptic type combinations. In this case, a higher frequency (%) value indicates higher (conditional) probability for a pattern-type combination occurring on elevated pollution days at the examined station, and vice versa (

Section 3.2). A propensity ratio greater than

one indicates that the combination is more likely than climatologically expected to be present on days with elevated PM10 pollution.

In general, the P4 (local hot-dry-NW wind conditions) combinations with T1~ T8 on the middle and left sections of the 4x3 SOM grid, i.e., westerly trough/anticyclonic types or northwest ridge types (

Section 4.3), tend to be more pollution conducive. As noted earlier, T1~T8 are characterised by the activity of eastward migrating (continental) high pressure systems (T1, T2, T5), westerly troughs (often associated with the passage of frontal systems) or a high-pressure ridge extending towards northern NSW or southeastern Queensland from the Tasman Sea (T3, T4, T6~T8), with a potential for providing southwesterly to northwesterly synoptic flows over the study region. These pattern-type combinations have higher frequencies at the Singleton (total: 50.0%) and secondarily Muswellbrook (total: 25.2%) stations (

Figure 9a,c). P4 is most pollution conducive at Singleton for its combination with one of T1~T8, but to a lesser degree at Muswellbrook for its combination with one of T2~ T5, as is indicated by the relatively high propensity ratios (

Figure 9b,d).

The combinations of P5 (local hot-dry-calm conditions) with synoptic types including T1~T8 also correspond to relatively high occurrence of elevated pollution days on the SOM plane, accounting for over 18% and 40% of the total number of elevated pollution days respectively at Singleton and Muswellbrook (

Figure 9a,c). Of these combinations, P5-T4 has the highest propensity ratio and thus most conducive to elevated pollution days. However, there exist considerable between-site variations, where P5 combinations with T2~T9 appear most pollution conducive at Muswellbrook but P5 combinations with T1~T4 most pollution conducive at Singleton (

Figure 9b,d).

The P1 (local dry-strong NW wind conditions) combinations with T3 and T4 also has high propensity ratios (thus pollution conducive) at Singleton but to a lesser degree at Muswellbrook. These synoptic situations are characterised by the passage of westerly troughs or frontal systems, resulting in southerly to southwesterly changes over the study region, leading to strong northwesterlies and hence increased dust generations in the valley. The combinations of P6 (local humid-strong-SE wind conditions) with a few synoptic types such as T6~T12 have relatively high frequencies at Muswellbrook. P6 combinations with T2 and T6 have relatively high propensity ratios (so more pollution conducive) at Muswellbrook (in the WNW subregion), while its combination with T4 shows high propensity values (hence pollution conducive) at both stations (subregions). It is interesting that P3 (humid-wet-SE wind) combined with T4 also shows high propensity ratios at two stations, probably being rare events due to the very low frequencies of this combination (<0.6%).

In summary, the combinations of P4~P5 with T1~T8 appear mostly related to elevated PM10 pollution in the Upper Hunter Valley, with variations observed between two stations (two subregion). The combinations of P1~P3 with synoptic states T9~T10 and secondarily T5~T8 appear least conducive to elevated pollution days. These findings are to some degree consistent with overseas studies of PM10 pollution in valley environments, for example, by Mohd Shafie et al. (2022), Quimbayo-Duarte (2021), Giri et al. (2008) and Reisen et al. (2017). Those studies suggested that elevated PM10 pollution are associated with dry conditions, low winds, thermal inversions and/or under the influence of high-pressure systems. In addition, the present study also shows that the passage of westerly roughs or frontal systems, combined with hot and dry local meteorological conditions (i.e., P4 and P5) tend to have high tendency for leading to high mean PM10 levels as well as elevated pollution events in the Upper Hunter Valley. These findings are broadly consistent with the previous studies on the relationship between local and synoptic meteorology and air quality conditions identified for urban environments in NSW. For instance, Jiang et al., (2017a) noted that two synoptic situations, characterised by the presence of a high-pressure cell over the Tasman Sea with a ridge extending north-west across NSW or southern Queensland, are commonly associated with elevated pollution levels and high chance for PM10 exceedance days in the Sydney basin during November-March. As noted earlier, some overseas studies also showed that the passage of low pressure or frontal systems can result in higher particle pollution due to increased wind erosion (e.g., Dayan and Levy, 2005; Huang et al., 2009).

5. Summary and Conclusion

The present study has examined the spatial-temporal variability of PM10 pollution in the Upper Hunter Valley based on the long-term (2012-2022), multi-site air quality and meteorological data. Jiang et al. (2024) reported the findings of the spatial and temporal variation modes by applying rotated principal component analysis and wavelet analysis. This text describes the classification of local meteorological patterns and synoptic circulation types in spring and summer and their relation to mean and elevated PM10 pollution at Singleton and Muswellbrook, respectively representing the SE and WNW air quality subregions in the valley (Jiang et al., 2024). The present analysis is featured with the use of the SOM method for the visualisation and interpretation of complex results on the SOM planes, in a holistic and structured manner. The main findings are summarised below:

- (1)

A catalogue of 12 synoptic circulation types has been established for summer and spring, when PM10 levels are generally higher in the Upper Hunter Valley. The most frequent synoptic types in spring are featured with a high-pressure system centred over the southern continent near the Australian Bight, the influence of westerly troughs/frontal systems in the further south, or a ridge extending northwest towards eastern NSW or southeastern Queensland from a high system centred over the Tasman Sea. In contrast, the more prevalent synoptic situations in summer are characterised by an anticyclonic system located in the south and a thermal low/easterly trough in the north of the domain.

- (2)

A classification of six local meteorological patterns has been quantitatively derived for the study region for the first time. The classification captures the meteorological configurations commonly experienced in the valley. The two most frequent patterns are: (1) hot-dry-calm conditions and (2) humid weather with strong southeasterly winds, which occur more in summer. In contrast, the cold-dry-calm condition is more prevalent in spring (rarely occur in summer). This classification is an important addition to the literature, as most previous studies of the local meteorology-air quality relationships for the region were qualitative, or based on correlation analysis of short-term PM10 data and individual meteorological variables.

- (3)

The connections between local meteorological patterns and synoptic circulation types are quantitatively visualised on the SOM planes from the two independently derived classifications. Each local pattern corresponds to a subset of synoptic types that are relatively similar and clustered together in the SOM grids. In other words, individual local meteorological patterns can have multiple synoptic type counterparts, and vice versa. To some degree, this multiplet correspondence may reflect the uncertainty in classifying the continuous, constantly evolving atmospheric states into discrete clusters. However, more importantly, this finding highlights the significant role of the interactions between local terrains and atmospheric circulations in determining local meteorological conditions and consequently air quality in the valley.

- (4)

Local meteorological pattens and synoptic circulation types associated with elevated PM10 pollution have been identified for two larger population centre sites (Singleton and Muswellbrook), broadly representing the WNW and SE subregions. On the synoptic scale, higher mean daily PM10 pollution are associated with situations that provide relatively strong southwesterly to northwesterly synoptic flows over eastern NSW. Synoptic types typical of easterly waves with a high-pressure system centred in the south correspond to generally low mean PM10 levels in the valley. Accordingly, two local meteorological patterns, the dry-strong NW wind conditions and the hot-dry-NW wind conditions, correspond to higher mean PM10 levels at both stations (subregions). In comparison, the local pattern featured with cool and humid weather with strong SE winds is related to low mean PM10 pollution in the valley.

- (5)

There are two groups of local meteorology-synoptic type configurations most conducive to elevated PM10 pollution days. One group is featured by the combinations of locally prevailing hot-dry-northwesterly wind conditions in the valley with synoptic situations characterised by: (a) the passage of eastward migrating high-pressure systems and easterly troughs (typical of frontal activities) over southeast part of the continent (anticyclonic/westerly trough types); or (b) a ridge extending northwest towards coastal northern NSW or southeastern Queensland from the Tasman Sea and a thermal trough extending from the northwest (northwest ridge types). These combinations provide a high chance for leading to elevated PM10 pollution at Singleton (broadly in the SE subregion) and secondarily Muswellbrook (broadly in the WNW subregion). The other group includes the combinations of locally prevailing hot-dry-calm conditions but with the anticyclonic/westerly trough types or northwest ridge types. These combinations have a high chance for elevated PM10 pollution events to occur at Muswellbrook (broadly in the WNW subregion) and to a lesser degree at Singleton (broadly in the SE subregion).

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated a holistic, quantitative approach for identifying the pollution conducive meteorological configurations for the Upper Hunter Valley. The SOM method has facilitated the classification of both synoptic and local meteorological conditions, and as well offered the convenience for summarisation and interpretation of the complex results in a structured/clustered manner. The findings have provided further insights into how local- and synoptic-scale meteorological configurations combine to determining the air quality properties in two subregions of the Upper Hunter Valley, as is identified in Jiang et al. (2024).

Our future work may point to a few directions. For example, the findings can be directly applicable for improving air quality data reporting and air forecasting (Jiang, 2017). Jiang et al. (2024) identified the variability modes at times scales of 30-90 days and 120 days in PM10 pollution. Previous studies showed that both local-, synoptic- and large-scale climatic conditions can affect local air quality in a region (e.g., Jiang et al., 2014). Hence, one may speculate whether the PM10 variability modes could be related to the influence of broad-scale climate drivers such as the Madden and Julian oscillation (MJO), El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Southern Annular Mode (SAM), which are known to modulate the weather and climate in Australia - this aspect deserves further attention in future work. In addition, although this study was focused on the air quality-meteorology relationships, it is acknowledged that a detailed analysis on the variability properties of PM10 emissions, when data become available, can also be useful for a more complete understanding of PM10 pollution in the study region. Finally, in echo to Jiang et al. (2016), this study has further demonstrated the utility of machine learning techniques for summarising and visualising the air quality data from the NSW air quality monitoring network. The methodology and results from this study can be useful for air quality research at other locations in NSW, or similar regions elsewhere.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: N Jiang; methodology, data curation and analysis: N Jiang; writing - original draft preparation: N Jiang; writing - review and editing: N Jiang, M Riley, M Azzi, G Di Virgilio, H Duc, P Puppala. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted/published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Upper Hunter Monitoring Network is funded by local power generation and mining industries in the Upper Hunter Valley and maintained by Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), New South Wales Government.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- ABARES. 2023. About my region – Hunter Valley (excluding Newcastle) New South Wales. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES): Canberra, Australia. Retrieved 27 September 2023, from: http://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/aboutmyregion.

- ABS. 2023. Search Census data by geography - Census 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2023, at: https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/search-by-area. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS): Canberra, Australia.

- Bridgman HA, Chambers AJ, 1981. Air Quality in the middle Hunter: the extensive study periods. A report to the New South Wales State Pollution Control Commission. University of Newcastle: Newcastle, Australia.

- Crawford J, Griffiths A, Cohen DD, Jiang N, Stelcer E. 2016. Particulate pollution in the Sydney region: source diagnostics and synoptic controls. Aerosol and Air Quality Research 16: 1055-1066. [CrossRef]

- Czernecki B, Półrolniczak M, Kolendowicz L, Marosz M, Kendzierski S, Pilguj N. 2017. Influence of the atmospheric conditions on PM10 concentrations in Poznań, Poland. Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry 74: 115–139.

- Dayan U, Levy I. 2005. The Influence of Meteorological Conditions and Atmospheric Circulation Types on PM10 and Visibility in Tel Aviv. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 44: 606-619. [CrossRef]

- DPE. 2020. Air quality special statement spring-summer 2019–20. Department of Planning and Environment. Retrieved 1 October 2023 from: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/air/nsw-air-quality-statements/air-quality-special-statement-spring-summer-2019-20.

- DPE. 2022. Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network. 5-year review 2022. State of NSW Department of Planning and Environment. Retrieved 25 March 2023, from https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/research-and-publications/publications-search/upper-hunter-air-quality-monitoring-network-5-year-review-2022.

- Fortelli A, Scafetta N, Mazzarella A. 2016. Influence of synoptic and local atmospheric patterns on PM10 air pollution levels: a model application to Naples (Italy). Atmospheric Environment 143: 218-228. [CrossRef]

- Giri D, Murthy K, Adhikary PR. 2008. The Influence of Meteorological Conditions on PM10 Concentrations in Kathmandu Valley. International Journal of Environmental Research 2(1): 49-60.

- Greene JS, Kalkstein LS, Ye H, Smoyer K. 1999. Relationships between synoptic climatology and atmospheric pollution at 4 US cities. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 62: 163-174.

- Hart M, de Dear R, Hyde R. 2006. A synoptic climatology of tropospheric ozone episodes in Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Climatology 26: 1635–1649. [CrossRef]

- Holmes 2008, Upper Hunter Valley Monitoring Network Design, 15th February 2008, prepared for NSW Department of Environment and Climate Change, Sydney.

- Holmes and Associates. 1996. Air quality study: cumulative effects due to atmospheric emissions in the Upper Hunter Valley, NSW. New South Wales Department of Urban Affairs and Planning: Sydney, Australia.

- Huang R, Ning H, He T, Bian G, Hu J, Xu G. 2018. Impact of PM10 and meteorological factors on the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease in female children in Ningbo, China: a spatiotemporal and time-series study. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International: 2018. [CrossRef]

- Huth R, Beck C, Philipp A, Demuzere M, Ustrnul Z, Cahynova M, et al. 2008. Classifications of atmospheric circulation patterns. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1146: 105–152. [CrossRef]

- Hyde R, Malfroy H, Watt GN, Maynard J. 1981. The Hunter Valley meteorological study: Interim Report to the New South Wales State Pollution Control Commission on Mesoscale Meteorology in the Hunter Valley. Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia.

- Jiang, N. 2008. Quality of the Auckland Airshed, A New Zealand Case Study. VDM Verlag Dr. Mueller: Germany.

- Jiang, N. 2010. Application of Two Different Weather Typing Procedures, An Australian Case Study. VDM Verlag Dr. Mueller: Germany.

- Jiang, N. 2017. Upper Hunter Dust Risk Forecasting Scheme Development. Final report to the NSW Environment Protection Authority. ISBN 978-1-76039-995-5. NSW Office and Environment and Heritage: Sydney, Australia.

- Jiang N, Betts A, Riley M. 2016. Summarising climate and air quality (ozone) data on self-organising maps: a Sydney case study. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 188: 103. [CrossRef]

- Jiang N, Cheung K, Luo K, Beggs PJ, Zhou W. 2012. On two different objective procedures for classifying synoptic weather types over east Australia. International Journal of Climatology 32: 1475–1494. [CrossRef]

- Jiang N, Dirks KN, Luo K. 2013. Classification of synoptic weather types using the self-organising map and its application to climate and air quality data visualisation. Weather and Climate 33: 52-75.

- Jiang N, Dirks KN, Luo K. 2014. Effects of local, synoptic and large-scale climate conditions on daily nitrogen dioxide concentrations in Auckland, New Zealand. International Journal of Climatology 34: 1883–1897. [CrossRef]

- Jiang N, Cheung K, Luo K, Beggs PJ, Zhou W. 2012. On two different objective procedures for classifying synoptic weather types over east Australia. International Journal of Climatology 32: 1475-1494. [CrossRef]

- Jiang N, Hay JE, Fisher GW. 2005. Synoptic weather patterns and morning rush hour nitrogen oxides concentrations during Auckland winters. Weather and Climate 25: 43-69.

- Jiang N, Luo K, Beggs PJ, Cheung K, Scorgie Y. 2015. Insights into the implementation of synoptic weather-type classification using self-organizing maps: an Australian case study. International Journal of Climatology 35: 3471-3485.

- Jiang N, Riley ML, Azzi M, Puppala P, Duc HN, Di Virgilio G. 2024. Visualising Daily PM10 Pollution Data in an Open-Cut Mining Valley of New South Wales, Australia—Part I: Identification of Spatial and Temporal Variation Patterns. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Jiang N, Scorgie Y, Hart M, Riley ML, Crawford J, Beggs PJ, Edwards GC, Chang L, Salter D, Di Virgilio G. 2017a. Visualising the relationships between synoptic circulation type and air quality in Sydney, a subtropical coastal-basin environment. International Journal of Climatology 37: 1211-1228. [CrossRef]

- Jiang N, Scorgie Y, Hart M, Riley ML, Crawford J, Beggs PJ, Edwards GC, Chang L, Salter D, Virgilio GD. 2017b. Visualising the relationships between synoptic circulation type and air quality in Sydney, a subtropical coastal-basin environment. Supporting information. International Journal of Climatology. [CrossRef]

- Kalnay E, Kanamitsu M, Kistler R, Collins W, Deaven D, Gandin L, Iredell M, Saha S, White G, Woollen J, Zhu Y, Chelliah M, Ebisuzaki W, Higgins W, Janowiak J, Mo KC, Ropelewski C, Wang J, Leetmaa A, Reynolds R, Jenne R, Joseph D. 1996. The NCEP/NCAR 40-Year Reanalysis Project. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 77: 437-472. [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. 2001. Self-Organizing Maps, 3rd edn. Springer-Verlag: Berlin.

- Lai H-C, Dai Y-T, Mkasimongwa SW, Hsiao M-C, Lai L-W. 2023. The Impact of Atmospheric Synoptic Weather Condition and Long-Range Transportation of Air Mass on Extreme PM10 Concentration Events. Atmosphere: 14: 406. [CrossRef]

- Lee D, Kim HC, Jeong J-H, Kim B-M, Lee D, Choi J-Y, et al. 2022. Relationship between synoptic weather pattern and surface particulate matter (PM) concentration during winter and spring seasons over South Korea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 127: e2022JD037517. [CrossRef]

- Leighton, R. M, Spark, E. 1997. Relationship between synoptic climatology and pollution events in Sydney. International Journal of Biometeorology 41: 76–89.

- Mohd Shafie, S.H. , Mahmud, M., Mohamad, S. et al. Influence of urban air pollution on the population in the Klang Valley, Malaysia: a spatial approach. Ecological Process 11: 3 (2022). [CrossRef]

- NEPC. 2021. National Environment Protection (Ambient Air Quality) Measure, Compilation No. 3. Australian National Environment Protection Council Retrieved June 22nd, 2022, from https:// www. legislation. gov. au/ Details/ F2021C00475.

- NPS. 2023. National Park Service, department of the Interior, USA. Retrieved 25 September 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/nature/airquality.htm.

- NSWEPA. 2019. 2013 Calendar Year Air Emissions Inventory for the Greater Metropolitan Region in NSW. NSW Environment Protection Authority Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 11 October 2023 from: https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/your-environment/air/air-emissions-inventory/air-emissions-inventory-2013.

- OEH 2012, Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network – 2012 Annual Report, NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/air/air-publications.

- OEH, 2017. Better evidence, stronger networks, health communities. Five-year review of the Upper Hunter Air Quality Monitoring Network. ISBN 978-1-76039-979-5. Office of Environment and Heritage: Sydney, Australia Authors.

- OEH. 2019. Annual Air Quality Statement 2018. State of New South Wales, Office of the Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 10 May 2023, from: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/research-and-publications/publications-search/nsw-annual-air-quality-statement-2018.

- Oke TR 2002, Boundary Layer Climates, 2nd edition. Taylor & Francis: UK.

- Pardo N, Sainz-Villegas S, Calvo AI, Blanco-Alegre C, Fraile R. 2023. Connection between Weather Types and Air Pollution Levels: A 19-Year Study in Nine EMEP Stations in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(4):2977. [CrossRef]

- Pearce JL, Beringer J, Nicholls N, Hyndman RJ, Uotila P, Tapper NJ. 2011. Investigating the influence of synoptic-scale meteorology on air quality using self-organizing maps and generalized additive modelling. Atmospheric Environment 45: 128-136. [CrossRef]

- Philipp A, Beck C, Huth R, Jacobeit, J. 2016. Development and comparison of circulation type classifications using the COST 733 dataset and software. International Journal of Climatology 36: 2673–2691. [CrossRef]

- Physick WL, Noonan JA, Manins PC. 1991. Air quality modelling study of the Hunter Valley. Phase 1: Emitters in the Upper Hunter. Electricity Commission of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia.

- POEO Regulation, 2021. Protection of the Environment Operations (General) Regulation 2021. New South Wales Government: Sydney. Retrieved 11 October 2023 from: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/current/sl-2021-0486.

- Quimbayo-Duarte J, Charles Chemel, Chantal Staquet, Florence Troude, Gabriele Arduini, 2021. Drivers of severe air pollution events in a deep valley during wintertime: A case study from the Arve river valley, France. Atmospheric Environment 247: 118030. [CrossRef]

- Reisen F, Gillett R, Choi J, Fisher G, Torre P. 2017. Characteristics of an open-cut coal mine fire pollution event, Atmospheric Environment 151: 140-51. [CrossRef]

- Riley M, Kirkwood J, Jiang N, Ross G and Scorgie Y. 2020. Air quality monitoring in NSW: From long term trend monitoring to integrated urban services. Air Quality & Climate Change 54(1): 44-51.

- Salvador P, Barreiro M, Gómez-Moreno FJ, Alonso-Blanco E, Artínaño B. 2021. Synoptic classification of meteorological patterns and their impact on air pollution episodes and new particle formation processes in a south European air basin. Atmospheric Environment 245: 1352-2310. [CrossRef]

- Schofield R, Utembe S, Gionfriddo C, Tate M, Krabbenhoft D, Adeloju S, Keywood M, Dargaville R, Sandiford M. 2021. Atmospheric mercury in the Latrobe Valley, Australia: Case study June 2013. Elemental Science of the Anthropocene 9: 1. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, SC. 2002. The redevelopment of a weather-type classification scheme for North America. International Journal of Climatology 22: 51–68. [CrossRef]

- SPCC. 1982. Air pollution dispersion in the Hunter Valley. ISBN 0 7240 5856 7. New South Wales State Pollution Control Commission.

- Sturman AP, Tapper NJ. 2008. The Weather and Climate of Australia and New Zealand. Oxford University Press: Cary, NC.

- Vesanto J, Himberg J, Alhoniemi E, Parhankangas J. 2000. SOM Toolbox for Matlab 5. Helsinki University of Technology: Espoo, Finland. Accessed 10 December 2023 at: http://www.cis.hut.fi/projects/somtoolbox/package/papers/techrep.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).