1. Introduction

The leguminous plants are highly prevalent and one of the important food crops in the world. However, long-term monoculture of leguminous plants could lead to depleted soil nitrogen (N) and be restrict with plants growth and development due to less N absorption in the soil system [

1]. To address this challenge, various methods and technologies have been employed.

One approach involves the application of synthetic N, which offers immediate results. Nevertheless, the use of synthetic N disrupts the biogeochemical cycle of nitrogen, giving rise to downstream environmental issues like air and water pollution, as well as climate change [

2]. In certain regions, gramineae-legume polycultures, such as rotation of wheat /corns and soybean cropping, is the primary agricultural production method to promote microbial metabolic efficiency and foster the development of multifunctional microbial communities [

3]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that intercropping with legumes could reduce the dependency on chemical fertilizers, increase crop yield, and enrich soil fertility [

4].

Artificial nitrogen fixation for legumes is another effective approach to replenish N in the soil with green environmental protection and energy conservation [

5]. By inoculating rhizobia before and during the sowing process, nodule formation on the roots of leguminous plants can be suitably and efficiently promoted [

6]. This practice significantly impacts the survival and subsequent effectiveness of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) capacity, plant survival and biomass development [

7,

8,

9]. It affects greatly on reducing nitrogen fertilizers and enhancing the crop yields [

10,

11].

The inoculation of rhizobia has been proven to achieve significant economic and ecological benefits through extensive application in the United States and Brazil [

12,

13]. As our investigation, there are two traditional inoculation manners employed in China: seed dressing with rhizobia and dispersing rhizobia into soil prior to seeding[

14]. In the first manner, the rhizobia are manually diluted and evenly stirred to the surface of seeds. To ensure the survival rate of rhizobia after dressing, the seeds must be promptly dried and sown into the soil [

15]. However, if the seed coats are damaged during dressing, it can lead to cause rot and seeding loss. The other manner is generally used at the stage of soil preparation. When the sunlight is dim, the rhizobia is evenly scattered into the soil and thoroughly mixed. Similarly, seeding operation also must be carried out in a short time to enhance the survival of rhizobia. These two traditional inoculation manners, lacking automatic control, required extensive preparation time, by resulting in time-consuming and laborious in the whole seeding process and reducing the survival rate of rhizobial inoculation under adverse environmental conditions. Consequently, the widespread application of these traditional inoculation techniques for cultivating leguminous plants with rhizobial strains has been limited. Therefore, applying rhizobia and its spraying control system is crucial to significantly increase the yield of leguminous plants and enhance working efficiency.

Nowadays, precision agriculture (PA) is defined as a complication of operations and tools to assess farming needs and apply them precisely in the optimal location at the most opportune time[

16,

17]. This approach involves more precise seeding, fertilizer, irrigation, and pesticide input in order to optimize crop production for the purpose of increasing grower revenue and protecting the environment[

18]. The advent of electric-driven control systems has significantly expanded the scope for integrating technological advancements in automation into various PA applications [

19,

20]. Due to the high requirements of agricultural machine and agronomy, the research on variable rate technology (VRT) has been attracting growing attention[

21].

Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) control technology as an important technical technology in VR control is applied in diverse agricultural fields[

22]. A PID controller serves as a standard loop feedback mechanism within a control loop, aiming to rectify and discrepancies between a measured value and a desired value. An optimal control system demands minimal rise time, settling time, peak time and maximum overshoot percentage. There are a large number of PID control researches of VR solid and liquid fertilizer/insecticide control within agricultural machine. Jicheng Zhang presented an increment PID control algorithm in precision fertilization control system for solid fertilizers, the application accuracy of urea, diammonium phosphate and potassium chloride were respectively more than 97.22%, 98.60% and 97.73% based on a soil prescription map. This significantly met the requirements of a precision fertilization system [

23]. Additionally, Wenfeng Sun developed a neural network PID variable application system to improve the efficiency of the existing variable spray control system and solve the delay associated with fuzzy decision-making [

24]. In this research, spray rates ranging from 18-36 L min

-1 were controlled to achieve minimal steady-state error and shortened response time. Chaofan Qiao proposed a control plan for timely-started active hydro-pneumatic suspension, incorporating a fuzzy PID control system optimized through genetic optimization. This approach demonstrated the active suspension had a significantly better damping effect than the passive suspension in the effectiveness of the active damping scheme [

25]. Similar technologies include particle swarm optimization (IPSO) algorithm, which optimized the coefficients of the PID controller for trajectory tracking accuracy problems. It demonstrated that the IPSO-PID method can achieve the highest tracking accuracy improving the tracking accuracy by 37.14% and 50.32%, respectively [

26]. Varshney presented a detailed study on the performance of a Brushless DC (BLDC) motors supplying different types of loads by an advance Fuzzy PID and the commonly used PID controller [

27].

Meanwhile, pulse-width modulation valve (PWM) is another VR technology to control rate by duty cycle. Three kinds of experiments of Manual-PWM, Laser-PWM and Disable PWM were used to control nozzle flow rates for precision spray applications, in which sprayer equipped with PWM solenoid valves would have great potentials to improve pesticide application efficiency with significant reductions in pesticide consumption and off-target drift loss to the environment [

28]. Jonathan Fabula also used PWM in agricultural sprayers to deliver the expected flow rate maintaining the target pressure and provide the desired droplet size. So, both PID and PWM are important method and technology to realize VR spraying in precision agriculture.

However, during leguminous plants production, only a small amount of rhizobium needs to be sprayed. Typically, the application rate for soybean in China is generally from 50 to 60 L/hm2 after suitable proportional dilution with water. In contrast, the input amount of liquid insecticide is usually between 120 to 150 L/hm2. So, the VR control system designed for liquid insecticide could not be directly applied to the small volume of liquid rhizobia. As we have known, there are few studies and reports on seeding and liquid rhizobial inoculation simultaneously by precision control technology for the leguminous plants. This lack of research has had a significant impact on rhizobial survival rates and inoculation efficiency.

In the view of this situation, a new rhizobium inoculation manner with a precision and efficient electric-driven control system combining with PID and PWM was developed in this paper. It seamlessly integrates four processes: ditching, seeding, spraying liquid rhizobia, and mulching, into a cohesive operating cycle. This approach ensures that the seeds and rhizobia are thoroughly mixed, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of rhizobial inoculation and bacterial survival. The objectives of this study are as follows: (i) to devise a precision spraying control system tailored for the small amounts of rhizobial inoculation; (ii) to integrate the developed system into a seeder; (iii) to assess and evaluate the accuracy of the system; and (iv) to compare the growth status of plants with rhizobial to those grown using traditional seeding methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Structure and Process Design

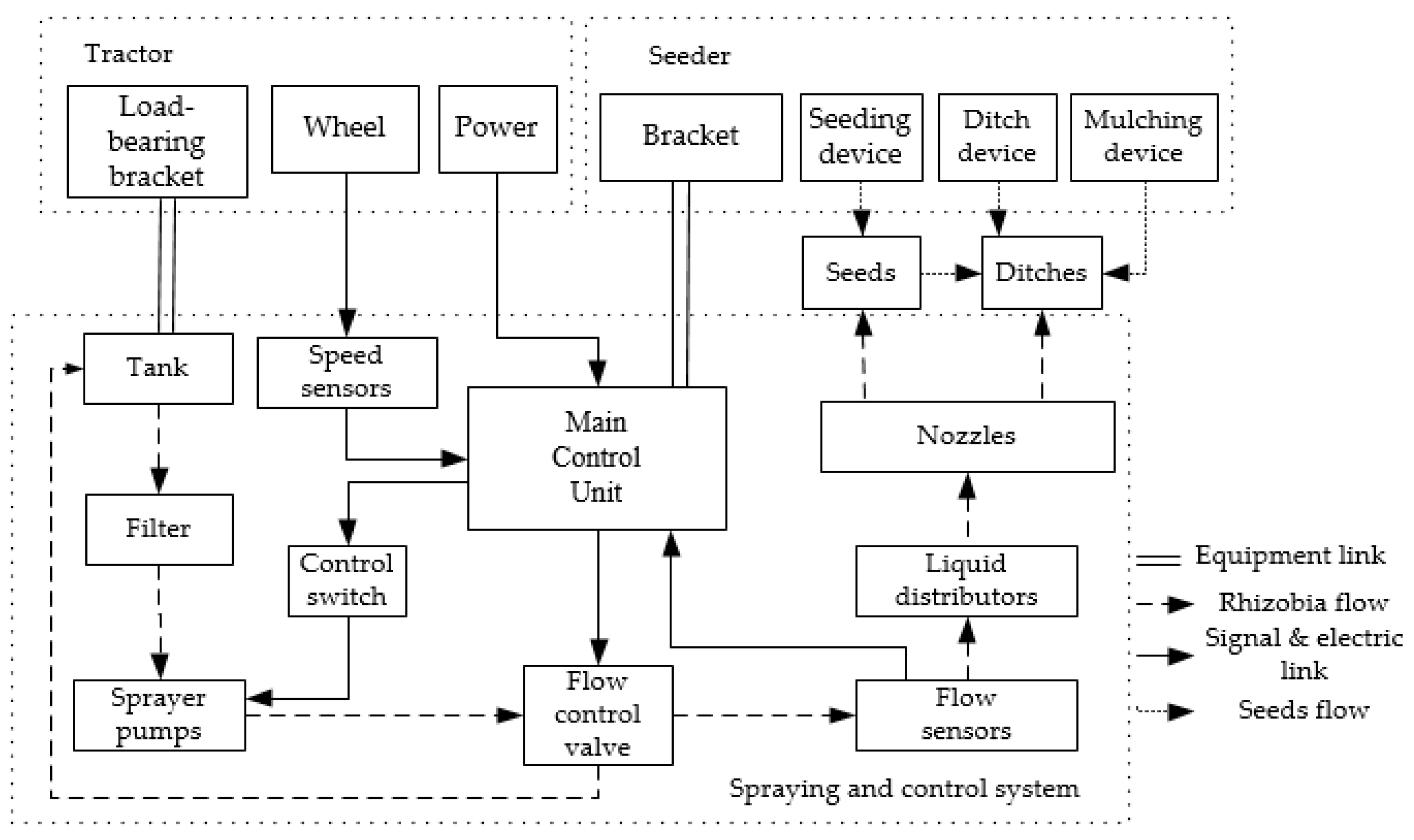

The schematic structure of spraying and control system designed for liquid rhizobial inoculation is presented in

Figure 1. Prior to the sowing process, rhizobia must be diluted based on the specific crop and soil characteristics. The tank of liquid rhizobia is mounted on the load-bearing bracket in front of the tractor. The controller of the spraying and control system for liquid rhizobia is installed on the bracket of the seeder. The nozzles of liquid rhizobia are located between seeding and mulching devices, facing with the seeding ditches. The outlet of the rhizobia tank is equipped with a filter and linked to the inlet of the spraying pumps via a hose. The outlet of a spraying pump is connected in sequence to the flow controller, flow sensor, liquid distributor and nozzles. Any rhizobia that exit the flow controller are redirected back to the liquid rhizobia tank. The main control unit (MCU) is interconnected with speed sensors, flow sensors, flow controllers, spraying pumps and the on-board battery, ensuring seamless operation of the entire system.

During the sowing process, the MCU precisely regulates the flow rate of liquid rhizobia according to the desired spraying rate, tractor speed and user instructions. This ensures that the rhizobia are sprayed and drizzled onto the seeds at the exact desired rate. Both the seeds and rhizobia are buried in the soil at the same time by using mulching device, so that the rhizobia remain concentrated around the seeds, thereby enhancing the efficiency of rhizobia inoculation.

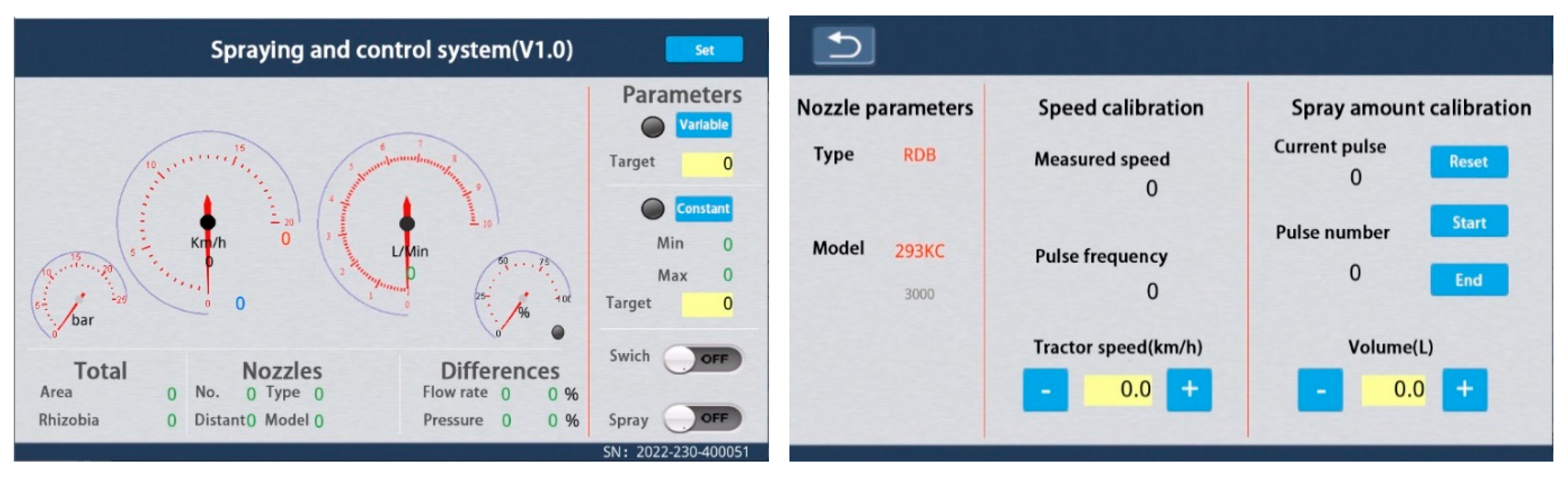

Moreover, the Control System App, connected to the MCU via a Bluetooth module, receives and sends messages for human-machine interaction (HMI). Prior to sowing, liquid rhizobial concentration, desired spraying rate, seeding area and etc. are set up on App terminals. During the sowing operation, the working state of spraying device will be real-time displayed on control system App, ensuring transparent and efficient operation.

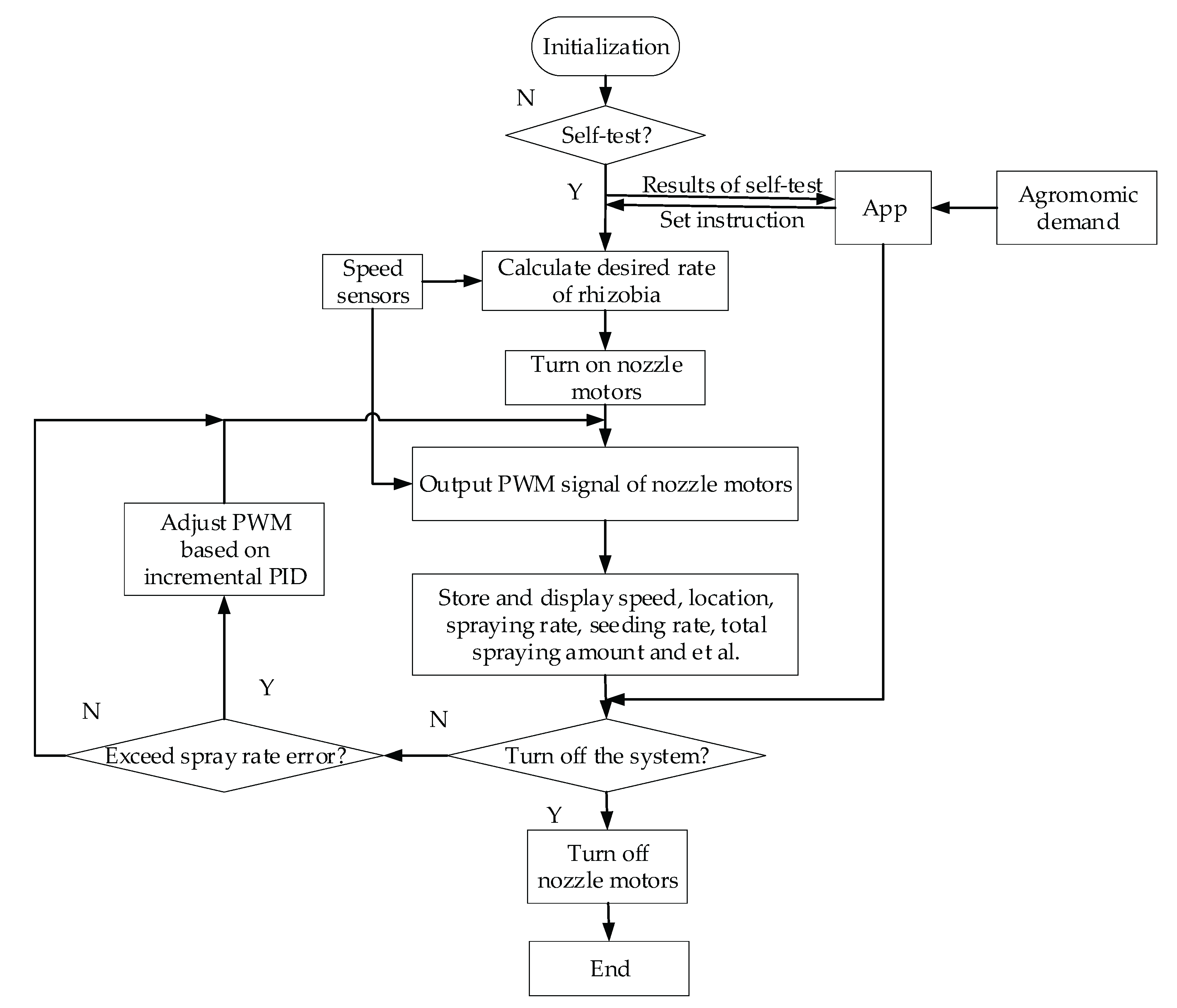

The operation flow of the control system is shown in

Figure 2. Upon initialization, the spraying and control system performs a self-diagnostic check. If any fault is detected during this self-test, the system will be shut down to prevent malfunctions. Otherwise, it proceeds to await the input of operational instructions. Subsequently, the flow controller is activated until it reaches a full reflux state, followed by the activation of the spray pump.

The controller receives real-time signals from various sources, including speed sensor, flow sensor, operation adjustment instruction from App, and abnormal system status. Embedded with incremental PID control algorithm, the controller realizes accurate spraying of rhizobia by pulse width modulation(PWM) technology[

29]. This ensures optimal performance and efficiency in rhizobial inoculation. Once the spraying task is completed, the control system is gracefully shut down, ensuring a seamless operational cycle [

30].

2.2. Hardware Design

The spraying and control system centers on the STM32F407 controller, leveraging the CAN bus communication protocol for communication. It interfaces with the App via a Bluetooth module (ATK-HC05-V13), ensuring a robust wireless connection. The encoders (E38S6G5-100B-G24N) installed on the slave drive wheel of the seeder are used to accurately calculate the tractor speed. Flow controller, specifically a small steering engine that regulates the pressure valve assembly, is employed to adjust the internal pressure of spraying device, so as to adjust the flow of liquid rhizobia.

In certain typical cases, a large planter with 3 ridges spanning 1.3 meters is operated at the speed of 8 km/h, while a small planter with a single ridge across 0.65 meters is operated at the speed of 5 km/h. Through calculation of the spraying rates of these two seeders, Licheng VP11002 (with a flow rate range of 0.65-1.04 L/min was selected as the optimal choice for precise, small-volume spraying.

The additional hardware components of this system comprised the following: (a) mini high-precision liquid hall flow sensor (Yihai MH-S650); (b) diaphragm pump (Dafengda 5G-210); (c) three-way water distributor (Shuangding); (d) pressure sensor (HK 12-P145B); (e) a pressure gauge from Hongsheng Instrument Factory (model N710) with a range of 0 to 0.25 MPa.

2.3. Speed Measuring Module

In order to ensure the uniform spraying of rhizobia, the control system needs to adjust the spraying rate in real time mainly according to the speed of seeder. Hall sensor has strong anti-interference, reliable accuracy, stable working performance, and is less affected by field operating environment factors[

31,

32]. During sowing process, the main controller system computes the moving speed of the tractor according to the pulse signal generated by Hall sensor. Consequently, the equation of tractor speed is derived as follows:

Where, is the moving speed of tractor (m/s), is the velocity measurement period (s), is the number of pulse signals rotated around the Hall sensor, is the number of pulses in the velocimetry period, is the diameter of the ground wheel (m), and σ is the slip coefficient in the range of 0.05-0.12.

2.4. Incremental PID Closed-Loop Control Algorithm

In order to improve the control precision of the spraying system of rhizobia, the incremental PID closed-loop control algorithm was applied to realize the control of spraying device [

33,

34]. The control deviation between the desired spraying rate at a certain moment

and the actual spraying rate

is

:

Where, is the input of PID controller.

is the output of PID controller and the input signal of the controlled object. The control law of the analog PID controller is as follows:

Where, is the proportionality coefficient, is the integral constant, is the differential constant, is the control constant, is the integral coefficient and the differential coefficient.

Incremental PID control algorithm needs to calculate the increment of control. The output value of sample time

kth and

k-1th determined with the following expression:

The incremental PID control algorithm can be obtained by subtracting Equations(4) and (5) as follows:

It can be seen from Equation (6) that if the control system employs a constant sampling period

, once the coefficient

,

are determined, the control increment can be obtained by using the deviation of the last three measured values[

23,

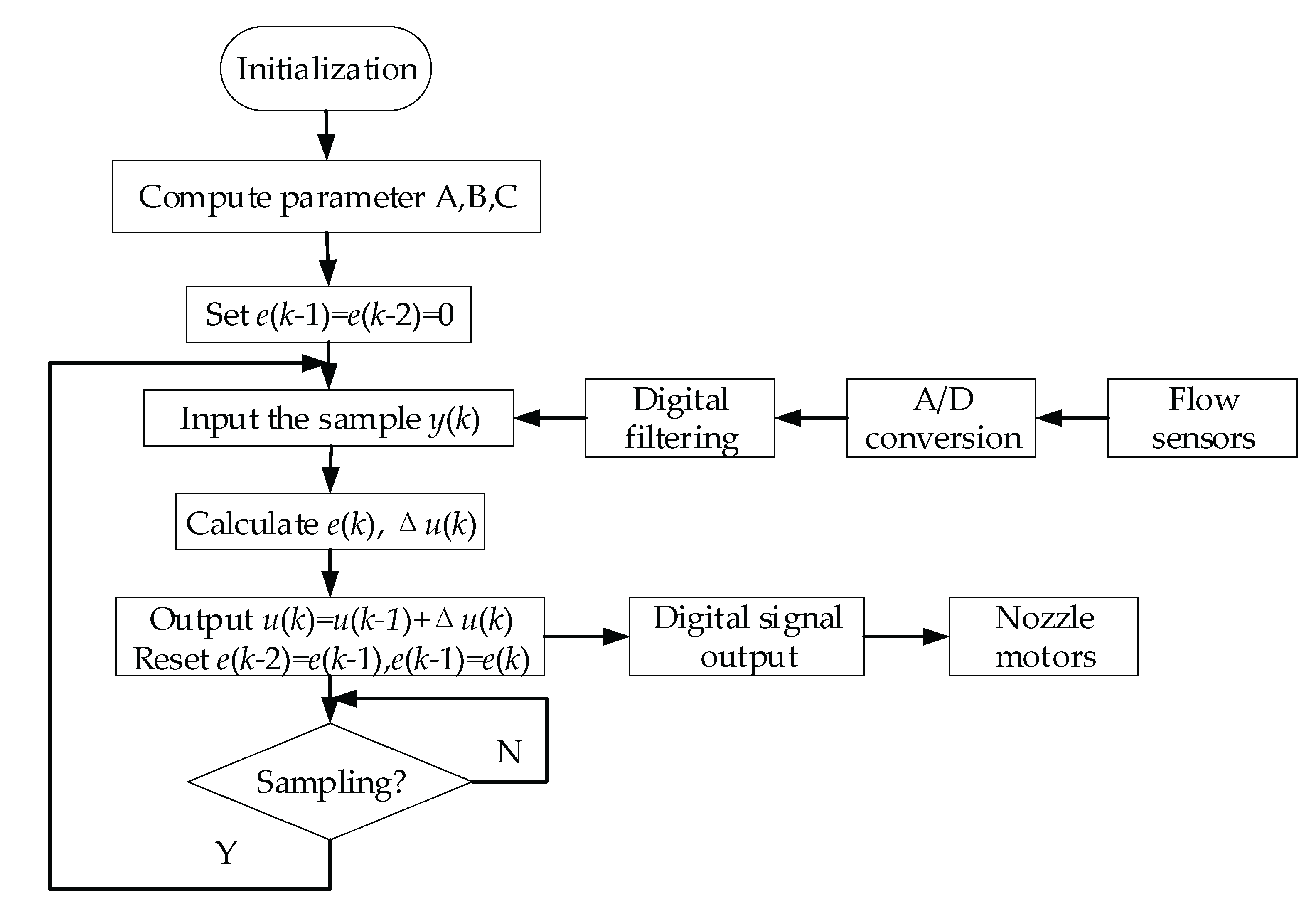

35]. The flow of incremental PID is shown in

Figure 3.

The output of incremental PID relies on the error of the current state and the preceding two states, requiring minimal computation, and only the increment is controlled. If there is a fault in the system, the impact of misoperation is small. Furthermore, the actuator possesses a memory function, allowing for resets without significantly disrupting the system's operation.

2.5. Spray Rate Measurement and Coefficient of Variation

The spraying rate of nozzles under a given working pressure are measured with no less than three tests in each group[

36]. They are calculated by Equation (7), and the standard deviation (STD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of spraying rate are calculated by Equations (8) and (9), respectively.

Where, qi is spraying rate of nozzle ith (L/min), n is the number of nozzles, is the average spraying rate (L/min), STD is standard deviation (L/min), CV is the coefficient of variation of spraying (%).

3. Results

3.1. Laboratorytest

3.1.1. Variability Test of Spraying Rate

The evaluation of spraying rate variability was conducted at the Engineering Training Center of Northeast Agricultural University, situated in Heilongjiang Province of China. The test platform was constructed with a double diaphragm plane, a three-way water distributor, three nozzles, a pressure sensor, a pressure gauge and various hoses.

The pressure sensor and pressure gauge worked in tandem to monitor the nozzles' real-time pressure, providing a solid foundation for reliable quality control within the control system. The internal pressure of the spraying device was manually adjusted using a pressure regulating valve located on the water distributor.

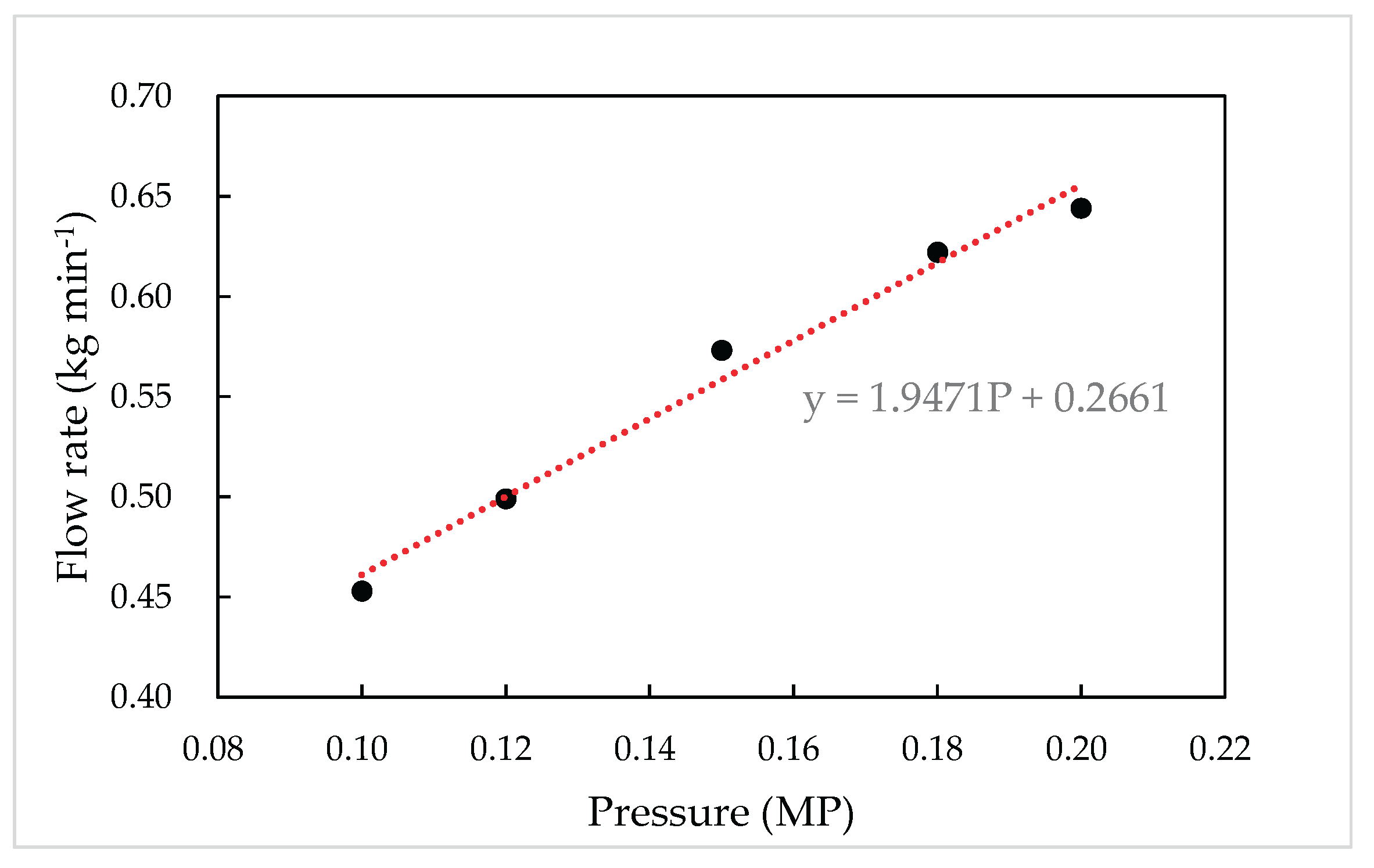

The spraying rate of three nozzles under the pressure of 0.10MP, 0.12 MP, 0.15MP, 0.18 MP and 0.20MP were measured respectively. Each group of tests was repeated for 3 times, and the mean value, STD and CV of spraying rate were subsequently calculated, as shown in

Table 1. It can be seen that CV of spraying rate was relatively low, indicating that these nozzles exhibited excellent performance in spraying liquid during laboratory testing.

According to

Figure 4, when the range of pressure was from 0.10 MP to 0.20 MP, the linear model of spraying rate was established as follow:

Where, P was the pressure, MP; SR was spraying rate, kg·min-1. Average coefficient of determination of this model was 0.9842.

This model can provide a solid operational foundation for spraying operation. Once the theoretical spraying rate is established, the necessary working pressure could be derived using Equation (10).

3.1.2. Precision Spraying Test of Control System

The incremental PID closed-loop control algorithm [

35,

37] was applied in this study, and pressure sensor data was used as control feedback to dynamically adjust the internal pressure of the rhizobia spraying device through the electric pressure regulating device, so as to ensure that the spraying rate of liquid rhizobia could be accurately controlled at different speeds of tractor[

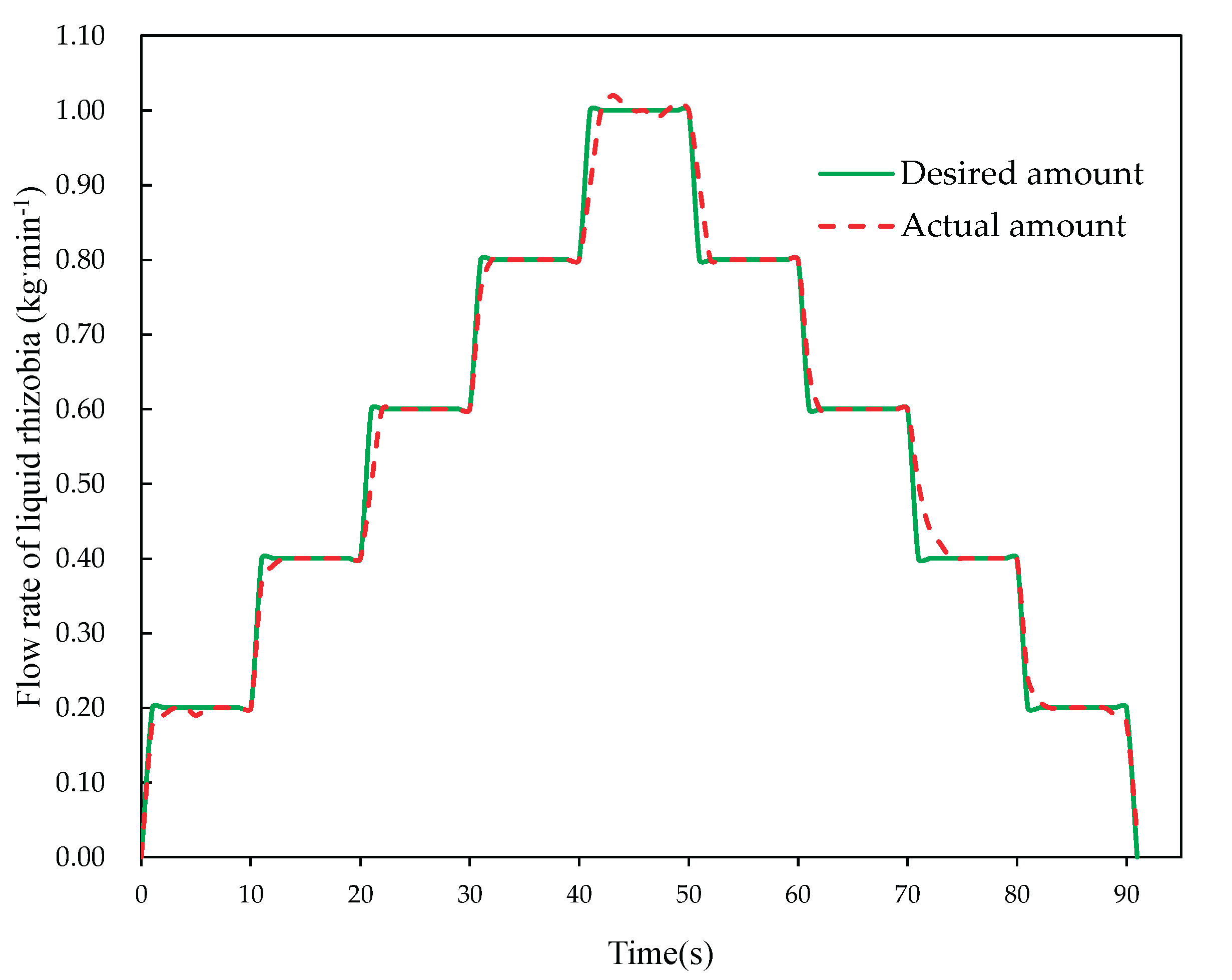

38]. In the laboratory, the experiment was carried out at an increasing rate of 0.20 kg/min within the range of 0~1.00 kg/min, documenting the spraying rate at each stage.

The experimental outcomes revealed that, under identical conditions, the maximum and average response times for the classical PID were 2.33 s and 1.96 s respectively. However, with the incremental PID, the maximum response time was reduced to 1.93 s, and the average response time to 1.62 s, representing a decrease of 17.2% and 17.3% compared to the classical PID.

Figure 5 illustrates how the incremental PID effectively controlled the actual amounts of liquid rhizobium agent with the desired amount.

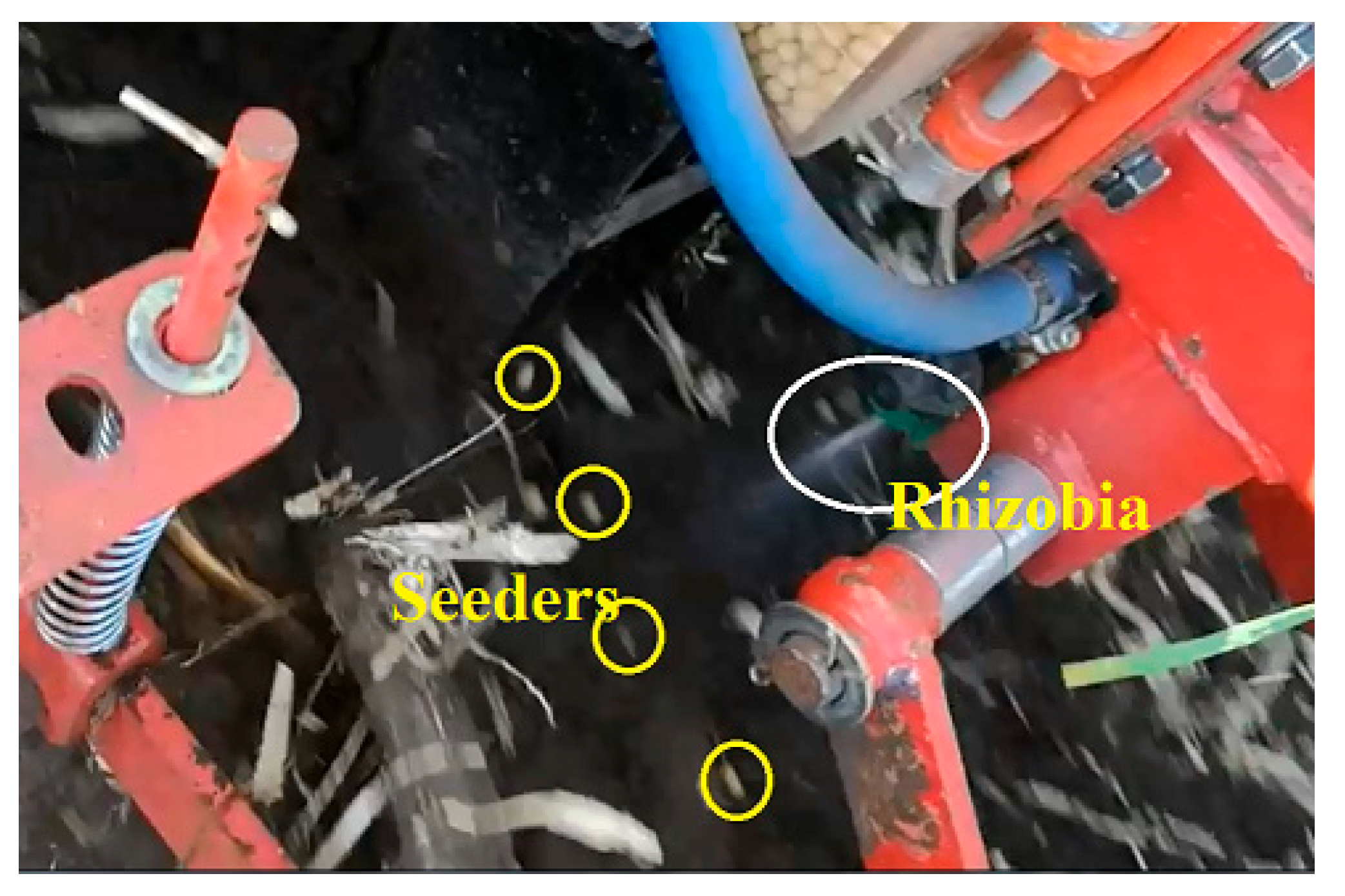

3.2. Field trial

The spraying and control system of rhizobial inoculants were respectively equipped on a 2-row soybean no-till seeders and 9-row soybean seeders in Heilongjiang province, on 6-row soybean no-till seeders in Shandong province and Anhui province from 2019 to 2023. Field trials were conducted on different types of soybean seeders, with a total of more than 3200 hours operation, covering an area of more than 2,000 hm

2 in different provinces and cities. The test machine was shown in

Figure 6, and the picture of seeding and spraying process was shown in

Figure 7. The establishment of operational parameters and the exhibition of operational status can be accomplished via the interactive screen integrated on the onboard system (

Figure 8).

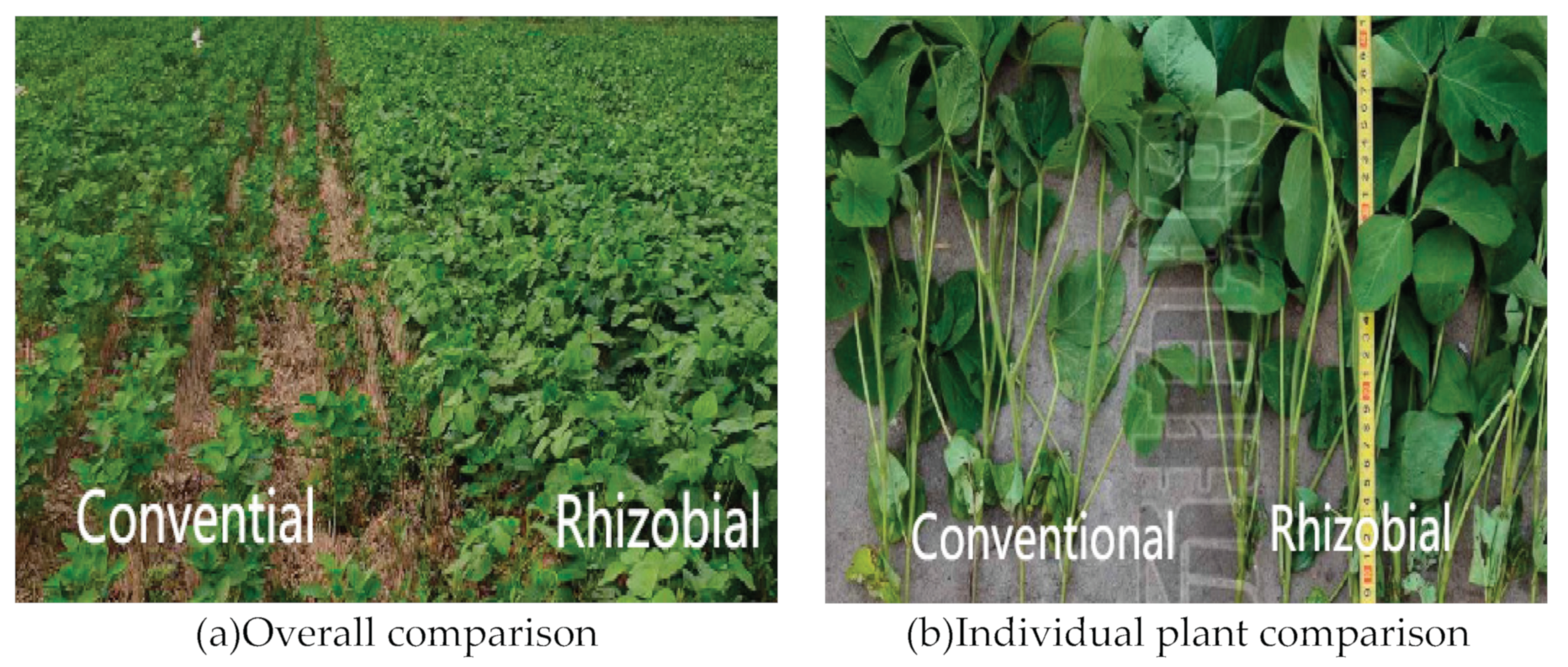

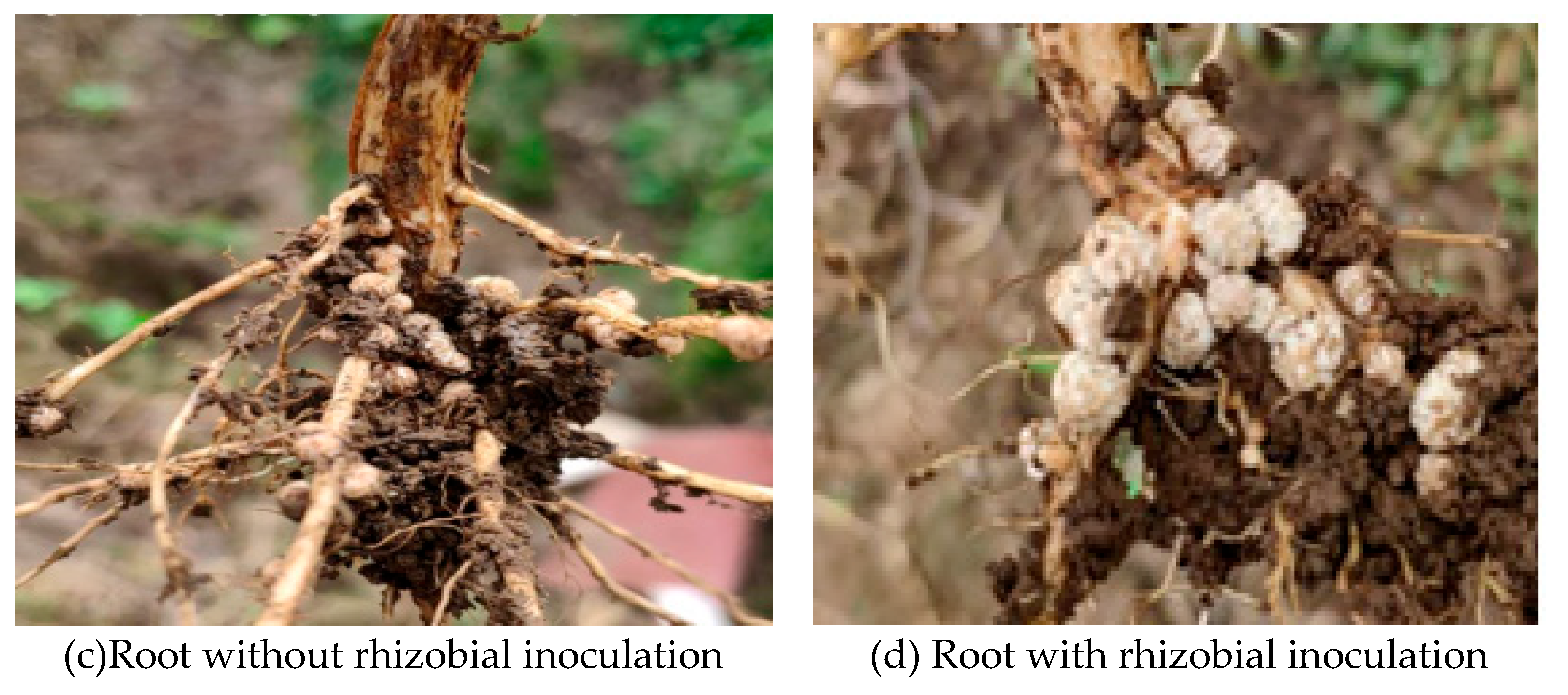

It can be seen from the comparative experiment at Xidian Farm in Shandong province that the soybean growth, the size and number of nodules with rhizobial inoculation were significantly better than the conventional seeding without using rhizobia (Figure9). Main root morphology of rhizobia was relatively robust with large and plump nodules, which the fibrous roots were dense and long with small and dense nodules.

The field experiment of spraying and control system for rhizobia was conducted at Heilongjiang Agricultural Xianghe Farm in 2022.Test variety used was Heihe 43. The base fertilizers consisted of 46% Urea, 18-46% Diammonium phosphate, and 50% potassium sulfate, formulated based on soil fertility as detailed in

Table 2. The test soybean rhizobium bacterial agent contained more than 2 billion effective live bacteria per milliliter.

Comparative experiment on rhizobial inoculation and nitrogen reduction were designed shown as in

Table 3. Each seeding manner was applied on a 3.5 hm2 plot. The "Doulebao" liquid rhizobia from China Agricultural University was selected and diluted from a concentrated solution of 450 ml/hm2 to a weak solution of approximately 53.45 L/hm2. The tractor speed was maintained within the range of 8-12 km/h.

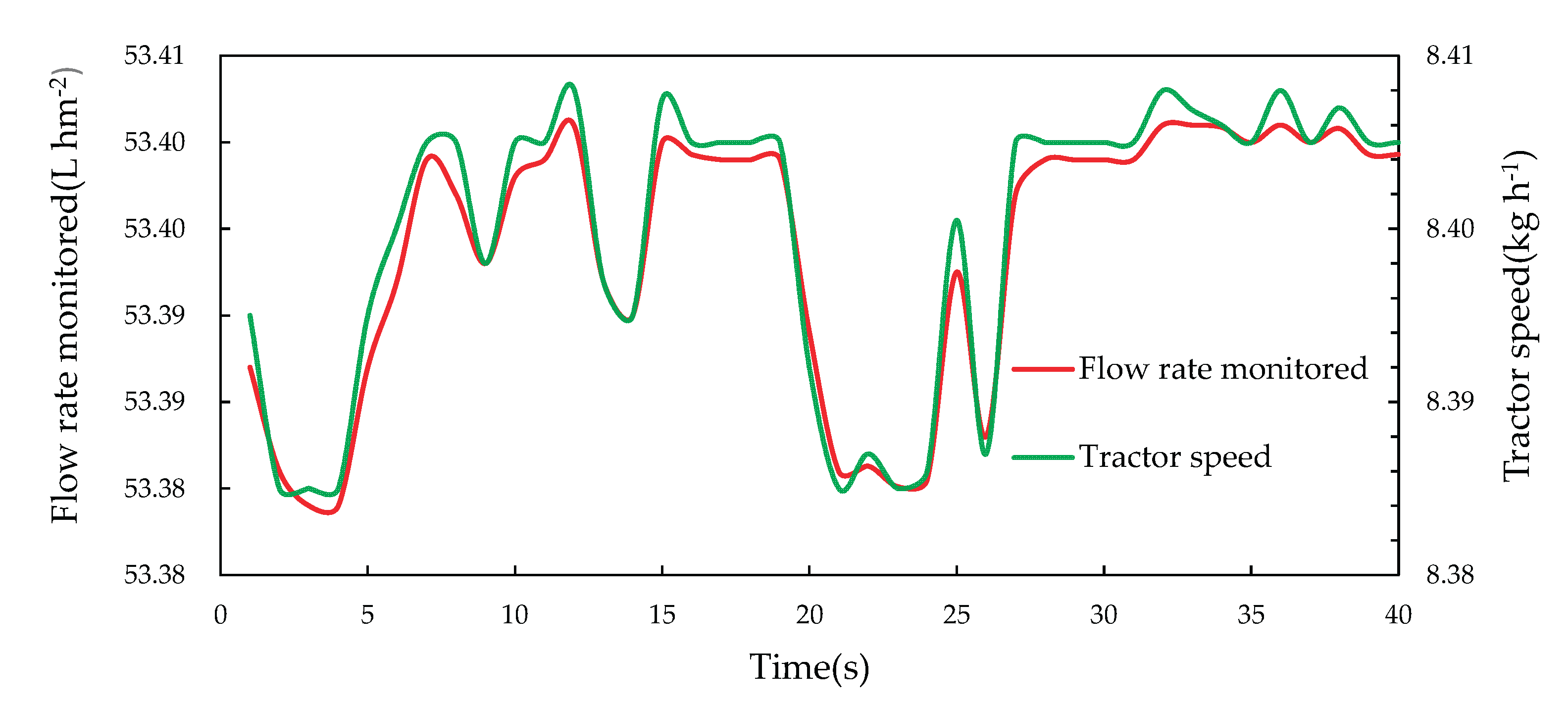

Figure 10 was the part of the records of liquid rhizobia flow rate monitored along with the fluctuate of tractor move. Due to control system, the variable-rate flow control of liquid rhizobia accurately followed the trend of tractor speed, which could avoid the waste with constant-rate fertilization.

At the mature stage of soybean, a diagonal sampling method was adopted in field trial. Three 2-m

2 sampling points were randomly selected, and the soybean plants in the sampling points were taken back to the laboratory for seed examination and yield measurement. According to the field investigation results of soybean growth period, the application of rhizobia agents in various treatments showed relatively similar growth processes, indicating that the application of rhizobia and nitrogen reduction did not affect the growth process of soybean (

Table 4).

There was no significant difference in plant height. The average height of the bottom pod was 1.46 centimeters shorter than the control group. Number of pods and seeds per plant were about 2.75 more, and the weight of 100 seeds was about 0.275 g heavier. The average number of root nodules was about 24 more with inoculation (

Table 5).

Overall, the yield of inoculated rhizobia was higher than that of the control group. Seeding treatment No. 2 got the highest yield of all (

Table 6). If the price of soybean was 5.8 yuan/kg in 2022 in China, the output value and benefit can be calculated shown as

Table 6.

4. Discussion

1) Our results showed a positive effect of rhizobial inoculation of on the growth and yield of soybean in field trials. Growth status of pods number, grains number, hundred-grain weight and nodules number with rhizobial inoculation were better than the control group (

Figure 9), supporting previous results in which inoculation with rhizobia had a promoting effect on crop growth[

6,

39,

40].

2) Rhizobia is a good type of biological fertilizer. When it propagates around the roots of leguminous plants, it fixes free nitrogen in the air. Therefore, plants generally do not need to use nitrogen fertilizer in this situation. So, if nitrogen fertilizer is applied, it can prevent nitrogen fixing bacteria or rhizobia in food from fixing nitrogen, forming an inhibitory effect.

In this experiment, the rhizobia are applied, and a great amount of nitrogen fertilizers should not be used in the test. According to the soil test values of the previous year, the first 4 treatments with suitable nitrogen fertilizer did not show any phenomenon of fertilizer removal. Both the soybean canopy and roots were not affected by nitrogen fertilizer input in this experiment. In

Table 5, the nodules number of No.3 was most in these five treatments. This is helpful to develop fertilization plan.

3) The growth cycles of these 5 treatments were relatively consistent (

Table 4). The growth period were about 115 days. Although rhizobia can fix nitrogen in the atmosphere, they cannot directly affect the growth cycle of soybeans. The study also indicates that the growth cycle of soybeans depends primarily on genetic traits and environmental factors, rather than the presence or absence of rhizobia.

Table 4 indicated that the application of rhizobia and nitrogen reduction can improve soybean growth condition and no impact on the growing period.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a spraying and control system for rhizobial inoculation based on incremental PID was developed. The following conclusion can be drawn from the laboratory test and field trial:

(1) In order to realize an automatic inoculation manner of rhizobia, this study developed a spraying and control system for rhizobia, which improved the inoculation efficiency of rhizobia. It will overcome the time-consuming and laboring problem of manual rhizobia inoculation, and provide important technical support for the large-scale application and popularization of rhizobia technology.

(2) In the laboratory test of precise flow control, variation coefficient of spraying nozzle from 0.10 MP to 0.20 MP pressure were no more than 1.2%. There was a linear relationship between spraying rate and pressure, and it was useful to spraying rate control.

(3) Based on incremental PID closed-loop control algorithm, the laboratory experiment was conducted at an increasing rate of 0.20 kg/min in the range of 0~1.00 kg/min, the maximum response time of the system was 1.93 s, and the average response time was 1.62 s.

(4) In the field experiment of Heilongjiang Agricultural Xianghe Farm, nodule number, pod number, 100-grain weight and nodules number were superior to those without rhizobia. The average yield of the group of spraying liquid rhizobia agent with base fertilizer increased by 232.5 kg/hm2, with a range of 7.4 %. The net income increased by 1288.5 yuan/hm2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and Z.J.; software, Y.S. and H.S.; formal analysis, Z.J.; data curation, Z.J.; writing-original draft preparation, Z.P and H.Y..; writing—review and editing, Z.P.; project administration and funding acquisition, J.W and Z.J.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD2300100), the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-04), and the new round of Heilongjiang Province's "double first-class" discipline collaborative innovation achievement project (LJGXCG2023-038).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barbieri, P.; Starck, T.; Voisin, A.-S.; Nesme, T. Biological nitrogen fixation of legumes crops under organic farming as driven by cropping management: A review. Agricultural Systems 2023, 205, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cao, W.; Zhai, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Adl, S.; Gao, Y. Leguminous green manure enhances the soil organic nitrogen pool of cropland via disproportionate increase of nitrogen in particulate organic matter fractions. CATENA 2021, 207, 105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, N.; Dobies, T.; Cesarz, S.; Reich, P.B. Plant diversity effects on soil food webs are stronger than those of elevated CO2 and N deposition in a long-term grassland experiment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 6889–6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X. , ChaochunYu, YangShen, Jianbovan der Werf, WopkeZhang, Fusuo %J Plant; Soil. Intercropping legumes and cereals increases phosphorus use efficiency; a meta-analysis. 2021, 460. [Google Scholar]

- Paravar, A.; Piri, R.; Balouchi, H.; Ma, Y. Microbial seed coating: An attractive tool for sustainable agriculture. Biotechnology Reports 2023, 37, e00781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Júnior, E.B.; Favero, V.O.; Xavier, G.R.; Boddey, R.M.; Zilli, J.E. Rhizobium inoculation of cowpea in Brazilian Cerrado increases yields and Nitrogen fixation. Agron J 2018, 110, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, M.D.; Pearce, D.J.; Peoples, M.B. Nitrogen contributions from faba bean (Vicia faba L.) reliant on soil rhizobia or inoculation. Plant Soil 2013, 365, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Nogueira, M.A.; Araujo, R.S. Co-inoculation of soybeans and common beans with rhizobia and azospirilla: strategies to improve sustainability. Biol Fertility Soils 2013, 49, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qiang, P.; Chen, F.; Yan, X.; Liao, H. Effects of co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia on soybean growth as related to root architecture and availability of N and P. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Nogueira, M.A.; Campos, L.J.M.; Menna, P.; Brandi, F.; Ramos, Y.G. Seed pre-inoculation with Bradyrhizobium as time-optimizing option for large-scale soybean cropping systems. Agron J 2020, 112, 5222–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro La Menza, N.; Monzon, J.P.; Lindquist, J.L.; Arkebauer, T.J.; Knops, J.M.H.; Unkovich, M.; Specht, J.E.; Grassini, P. Insufficient nitrogen supply from symbiotic fixation reduces seasonal crop growth and nitrogen mobilization to seed in highly productive soybean crops. Plant, Cell and Environment 2020, 43, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, J.Z.; Hungria, M.; Sena, J.V.d.S.; Poggere, G.; dos Reis, A.R.; Corrêa, R.S. Meta-analysis reveals benefits of co-inoculation of soybean with Azospirillum brasilense and Bradyrhizobium spp. in Brazil. Appl Soil Ecol 2021, 163, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, N.J.; Katherine, J.W.; Stephanie, S.P.; Maren, L.F. Rhizobia protect their legume hosts against soil-borne microbial antagonists in a host-genotype-dependent manner. Rhizosphere 2019, 9, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.N.; Sun, Y.M.; Wang, E.T.; Yang, J.S.; Yuan, H.L.; Scow, K.M. Effects of intercropping and Rhizobial inoculation on the ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in rhizospheres of maize and faba bean plants. Appl Soil Ecol 2015, 85, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomska, A.; Klama, J. Pesticide side effect on the symbiotic efficiency and nitrogenase activity of Rhizobiaceae bacteria family. Polish J Microbiol 2005, 54, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, J.B.; Xia, J.F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S. Design and experimental study of the control system for precision seed-metering device. Int J Agric Biol Eng 2014, 7, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, J.F.; Esquivel, W.; Cifuentes, D.; Ortega, R.J.C. Field testing of an automatic control system for variable rate fertilizer application. Comput Electron Agric 2015, 113, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambouris, A.N.; Messiga, A.J.; Ziadi, N.; Perron, I.; Morel, C. Decimetric-scale two-dimensional distribution of soil phosphorus after 20 year of tillage management and maintenance phosphorus fertilization. Soil Sci Soc Am J 2017, 81, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Jack, D.; Hesterman, D.C.; Guzzomi, A.L. Precision metering of Santalum spicatum (Australian Sandalwood) seeds. Biosys Eng 2013, 115, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.J.; Llewellyn, R.S.; Mandel, R.; Lawes, R.; Bramley, R.; Swift, L.; Metz, N.; O'Callaghan, C. Adoption of variable rate fertiliser application in the Australian grains industry: status, issues and prospects. Precision Agriculture 2012, 13, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Song, S.; Li, Z.; Hong, T.; Huang, H. Variable rate liquid fertilizer applicator for deep-fertilization in precision farming based on ZigBee technology. IFAC PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.S.; Man, K.F.; Chen, G.; Kwong, S. An optimal fuzzy PID controller. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2001, 48, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Yan, S.C.; Ji, W.Y.; Zhu, B.G.; Zheng, P. Precision fertilization control system research for solid fertilizers based on incremental PID control algoriths. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2021, 52, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Fu, T.; Lv, J.; Wang, F. Design and experiment of PID control variable application system based on neural network tuning. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2020, 51, 55–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, C.; Wen, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, G. Damping Control and Experiment on Active Hydro-Pneumatic Suspension of Sprayer Based on Genetic Algorithm Optimization. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2021, 15, 707390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Ma, W.; Yin, C.B.; Cao, D.H. Trajectory control of electro-hydraulic position servo system using improved PSO-PID controlle. Automat Constr 2021, 127, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, A.; Gupta, D.; Dwivedi, B. Speed response of brushless DC motor using fuzzy PID controller under varying load condition. Journal of Electrical Systems and Inf Technol 2017, 4, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, R.; Zhu, H.; Ozkan, E.; Falchieri, D.; Wei, Z. Reducing ground and airborne drift losses in young apple orchards with PWM-controlled spray systems. Comput Electron Agric 2021, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzynadlowski, A.M.; Kirlin, R.L. Space vector PWM technique with minimum switching losses and a variable pulse rate [for VSI]. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 1997, 44, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, M.; Mallarino, A.P. Impacts of variable-rate phosphorus fertilization based on dense grid soil sampling on soil-test phosphorus and grain yield of corn and soybean. Agron J 2007, 99, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellet, D.S.; du Plessis, M.D. A novel CMOS Hall effect sensor. Sensor Actuat A-phys 2014, 211, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjevic, M.; Furrer, B.; Blagojevic, M.; Popovic, R.S. High-speed CMOS magnetic angle sensor based on miniaturized circular vertical Hall devices. Sensor Actuat A-phys 2012, 178, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.F.; Xue, X.Y.; Ding, S.M.; Le, F.X. Development of a DSP-based electronic control system for the active spray boom suspension. Comput Electron Agric 2019, 166, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cui, T.; Zhang, D.; Wei, J.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yan, B.; Zhao, D.; Yang, L.J.C.; Agriculture, E.i. Development of an electric-driven control system for a precision planter based on a closed-loop PID algorithm. Comput Electron Agric 2017, 136, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.D.; Qin, G.H.; Xu, B.; Hu, H.S.; Chen, Z.X. Study on automotive air conditioner control system based on incremental-PID. Advanced Materials Research 2010, 129-131, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-D.; Lee, H.-S.; Hwang, S.-J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Nam, J.-S.; Shin, B.-S. Analysis of spray characteristics of tractor-mounted boom sprayer for precise spraying. J. of Biosystems Eng. 2017, 42, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L. Design of a hybrid fuzzy logic proportional plus conventional integral-derivative controller. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 1998, 6, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, W.; Edgar, T.F.J.I.e.c.r. Simple Analytic PID Controller Tuning Rules Revisited. J Process Contr 2015, 53, 5038–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, R.d.A.; Martins, L.C.; Ferreira, L.V.d.S.F.; Barbosa, E.S.; Alves, B.J.R.; Zilli, J.E.; Araújo, A.P.; Jesus, E.d.C. Co-inoculation of Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium promotes growth and yield of common beans. Appl Soil Ecol 2022, 172, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebika, T.; Nongmaithem, N. Effect of rhizobium inoculation on yield and nodule formation of cowpea. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2019, 8, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).