1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Structural Optimization in the Construction Industry

The reliable optimization of complex engineering problems has gained considerable traction with the advent and enhancement of digital technologies and tools, enabling the efficient utilization of artificial intelligence (AI) optimization algorithms at a fraction of the computation cost. This has also allowed the idea of structural optimization to rise since obtaining the optimal performance from a structure with minimum weight is one of the main objectives in the architecture, engineering, construction, and operations (AECO) sector [

1], particularly to reduce the environmental impact of construction material [

2]. In this study, structural optimization is defined as finding the structure with minimum weight while satisfying all code-specific constraints on displacement, and strength. This structural design optimization problem is commonly divided into three sub-categories, namely, shape, size, and topology optimization. In shape optimization theory, the outer boundary of the structure or, in other words, the surface node coordinates of the structure are the design decision variables [

3,

4]. An example of shape optimization was given in [

5], where the authors improved the mechanical performance of free-form grid structures only by finding the optimal grid placement for the nodes. Sizing optimization, on the other hand, also referred to as cross-sectional optimization, is another structural optimization branch that concentrates on finding the best cross-section for the structural elements [

3] to fulfill the required design performance and objectives [

6]. As such, the design decision variable is the cross-section type, area, and shape. In fact, considerable improvements have been observed and reported on benchmark truss problems by considering constraints such as structural modal frequencies [

7]. Topology optimization encompasses the decision variables of both shape and sizing optimization [

3] within the structural optimization problem. However, the structures obtained by this method usually come with higher manufacturing costs due to the flexibility in layout, size, and shape of the structure, generating often complex geometries. To this end, additional constraints may be added to limit the complexity of the final structure, by utilizing a select set of modules for the layout of the structure [

8].

Overall, since the relationship between the objective function and the decision variables contains multiple intermediary steps, such as Finite Element Modeling (FEM), it cannot be represented in closed form [

2,

9]. As such, AI-based metaheuristic algorithms are commonly utilized to find a near-optimal solution to the structural optimization problem [

10]. Among metaheuristic algorithms, genetic algorithm (GA), a deep-rooted method that mimics evolutionary theory, is one of the most widely used among researchers to optimize structures [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Other metaheuristic algorithms were also employed, such as ant colony optimization (ACO), which mimics the behavior of ants [

16]; particle swarm optimization (PSO), a strong metaheuristic algorithm that mimics swarm behavior [

17]; and Bonobo optimization, which mimics the behavior of primates [

18]. It is reported that the Bonobo algorithm performs better or is competitive with other techniques according to the tests conducted on some truss examples. Further information about metaheuristic algorithms and their implementation can be found in the review article [

19].

1.2. Available Tools for AI-Based Structural Optimization in BIM Projects

Although these studies demonstrate the implementation of metaheuristic algorithms in the structural optimization process, scholars tend to use their own programs for the optimization, structural analysis, or structure generation processes. This is since software platforms such as MATLAB and Python have many built-in libraries to support the implementation of the optimization algorithms. In the recent studies on structural optimization with metaheuristic algorithms reviewed for this section, the referenced manuscripts [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] either employed proprietary programs or did not specify the software used for optimization. On the other hand, using MATLAB for structural optimization purposes is common among researchers [

2,

7,

18,

28]; however, MATLAB is not open sourced and generally not the preferred choice for FEM in the AECO industry for structural optimization. Python is generally more preferred since it is open-sourced [

27,

29]; however, due to the considerable numerical computational power offered by existing commercially available FEM software, the integration of the optimization software together with commercial structural analysis software provides a more efficient solution.

In [

30], SAP2000 [

31] was employed, instead of coding FEM from scratch, to conduct structural analysis during the optimization of large steel frame structures, particularly to reduce cost and weight of oil and gas modules. The shape and size optimization of large barrel vault frames was carried out in [

32] by employing SAP2000 via an open application programming interface (OAPI). An integration between MATLAB and SAP2000 using OAPI to optimize steel truss bridges with the aim of minimizing weight was investigated in [

33]. An integration between MATLAB and ANSYS was proposed in [

34], where the efficiency of different GA operators to perform topology optimization on a benchmark truss structure problem was evaluated. Another pertinent example is integration of visual programming (VP) software to support the parametric design of the structure. In reference [

35], Rhino-Grasshopper, a BIM-based VP tool, was utilized together with Karamba, a plug-in to Rhino for structural analysis, to perform optimization by employing GA operators. Along the same lines, the manuscript [

36] utilized Grasshopper to create geometry and developed a tool in C# to transfer the structure to SAP2000 to perform topology optimization. Grasshopper together with Peregrine plug-in were employed to perform layout and geometry optimization methods in sequence for optimum designs in [

37]. Furthermore, a framework that utilizes Dynamo for Visual Programming and OpenSees for measuring structural performance by using the FEM of the created models was proposed in [

38]. Another study [

39] developed a PSO algorithm for Dynamo by using both MATLAB and C# programming languages, where optimization of simple mathematical functions were tested.

While much research in the field was carried out, a stand-alone and interoperable framework that utilizes VP, FEM software, and AI-based optimization in BIM projects still requires further investigation. As such, this study examined the application of combining interoperable Autodesk platforms, including VP software, Dynamo; BIM tool, Revit; and FEM software, Robot Structural Analysis (RSA); together with a Python-based GA algorithm, developed as a function directly within Dynamo. The hypothesis was that this approach, due to the inherent interoperability between the Autodesk software platforms, might reduce possible computational overhead and/or loss of information between different information modeling platforms. In other words, the design is parameterized once in Dynamo, optimized using GA and RSA, and directly transferred into Revit (with no additional tools) for further simulations and engineering analysis, such as life cycle analysis (LCA), quantity surveying, and cost estimation. Furthermore, the Autodesk software platforms are well-established within the AECO industry and the free educational access for students and educators enables its possible widespread use for teaching, training, and industry transfer. Thus, this study focused on creating a workflow that integrates Revit-Dynamo with RSA to create a robust, efficient, and user-friendly environment to use structural optimization methods. The results were tested in available benchmark problems, such as 2D 10-bar, 3D 36-bar, and 3D 120-bar dome trusses and compared with the results reported in open literature to demonstrate the applicability of the proposed framework. Moreover, the interaction with Revit has also been established for further analysis of the optimized structures, particularly in LCA and cost estimation. Integration with parametric modeling tools, FEM analysis software, and BIM for optimization purposes enables the seamless transfer of knowledge between different platforms and with other team members through a common data environment (CDE).

1.3. Scope, and Objective of the Study

This study focuses on creating a workflow for AECO industry to create sustainable, affordable, and nature-friendly designs. By using optimization, less weighed and more functional designs can be constructed, which have a vital role for countries that have limited sources, resulting in reduced expenses and embodied CO

2 [

40]. It is necessary to mention that the objective of the study is not to develop the best genetic algorithm and the most efficient code or improve the existing optimization algorithms. Although better algorithms and codes can be developed and readily implemented into the proposed script, these issues are beyond the scope of the present research. Numerical examples are presented to only show the adaptability of the proposed workflow.

Furthermore, the scope of this research is limited to the problem of size optimization for truss structures and the aim of numerical examples is to select appropriate sections from a list of available sections to minimize the weight of the truss while satisfying constraints (e.g., stress, displacement, buckling). In this aspect, the sizing optimization problem investigated here resembles the combinatorial Knapsack Problem [

41]. Since GA has shown to effectively provide fast and heuristic solution the Knapsack problem, it was used here to provide a solution to the sizing optimization problem.

2. Methodology

2.1. Preliminaries

2.1.1. Genetic Algorithm

English naturalist Charles Darwin transformed our understanding of life through his exploration and concept of natural selection in his famous book, “On the Origin of Species”. He introduced natural selection as a metric for resilience of species/organisms to adapt to changes in their environment and evolve accordingly [

42]. In evolutionary theory, traits are established by chromosomes, which consist of groups of units called genes. The genes can pass on these traits to their offspring through a process referred to as crossover [

43]. The algorithms that use these logics and mimic similar evolutionary processes are called as Evolutionary Algorithms (EA). GA, which is a type of EA, starts by introducing an initial set of gene populations; identifying their objective fitness values; selecting the best genes, performing cross over and mutation; and generating a new population for the next generation [

12]. In trivial terms, the process aims at keeping the genes with the best fitness values and creating new combinations from these best genes to generate even better solutions in the successive generations.

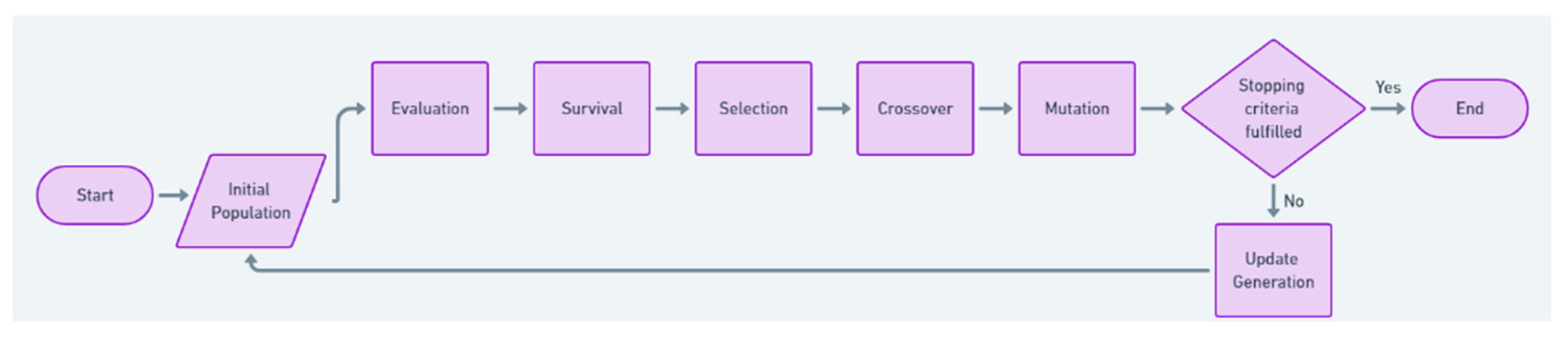

Figure 1 demonstrates the basic tenants of a simple GA.

In this study, the evaluation of numerical examples to validate the proposed workflow was performed using the PyMoo library [

44]. The type of GA operators was selected according to the default PyMoo settings. As the GA is just a tool for validating the workflow but not the goal, the focus was not on finding optimum parameters for the GA operators. That suggests that better results can be achieved by fine-tuning the parameter settings, or by employing other algorithms, such as PSO, ACO, or more recent Jaya optimization.

2.1.2. Formulation of the Truss Optimization Problem

As aforementioned above the goal of the proposed design is to optimize (minimize the weight of the structure (W) under multiple constraints) problems of truss structure with the proposed workflow. Consequently, the weight of truss structures is chosen as an objective function. The problem under consideration in this study can be defined mathematically as follows:

where

is the density of the material, A is cross-sectional area of the member, and

is length of the member. As can be seen above-mentioned formulation, the weight of the overall structure is taken as the objective. Because GA is ideal for unconstrained optimization problems, it is necessary to convert the problem into an unconstrained one before starting the optimization process [

45]. The transformation is performed by calculating the violation made on the constraints. These violations are penalized by the penalty term, which affects the objective function, that directs the search for workable solutions [

12]. Rajeev and Krishnamoorthy [

12] proposed a formulation based on the violations of normalized constraints in the referenced paper and it was found to work very well among scholars [

20]. Therefore, in this thesis same methods have been used to calculate objective function. In Eq. (2), the basic formulation of the proposed methodology is presented:

in the formula,

is the objective function and

K is a coefficient that is determined by the type of problem. For this study, a value of 10 for

K was chosen based on the findings in the referenced manuscript [

12] as it is found to work well for truss optimization problems. In situations where the design fully satisfies the constraints, the coefficient is set to a higher value, and heavier penalty values are assigned to solutions that have only a slight infringement on the constraints. This approach ensures that the constraints are not violated while the search for solutions continues. In engineering designs, minor deviations from the constraints are often acceptable [

12]. In such cases, when the main objective is to minimize the weight of the design, a smaller coefficient can be used. This allows for the exploration of solutions with lower weight, without including individuals that have extreme levels of constraint violation [

12]. This approach helps strike a balance between not violating the constraints and achieving a lighter design. C is the violation coefficient which is calculated based on the violation of constraints. The constraints are formulated in normalized form as demonstrated by the following formulas [

12]:

here

is the stress value on the element and

is the allowable stress. Similarly,

is the displacement on the nodes and

is the allowable displacement. The violation coefficient C is determined in the upcoming way: if

gi(x) > 0, then c

i =

gi(x); or if

gi(x) ≤ 0, then

ci = 0 [

12].

where m = the number of constraints. After making all the calculations the problem turns into an unconstrained optimization problem and the new objective function becomes ∅(x) [

12].

2.2. Proposed Framework

The overall methodology consists of the following steps:

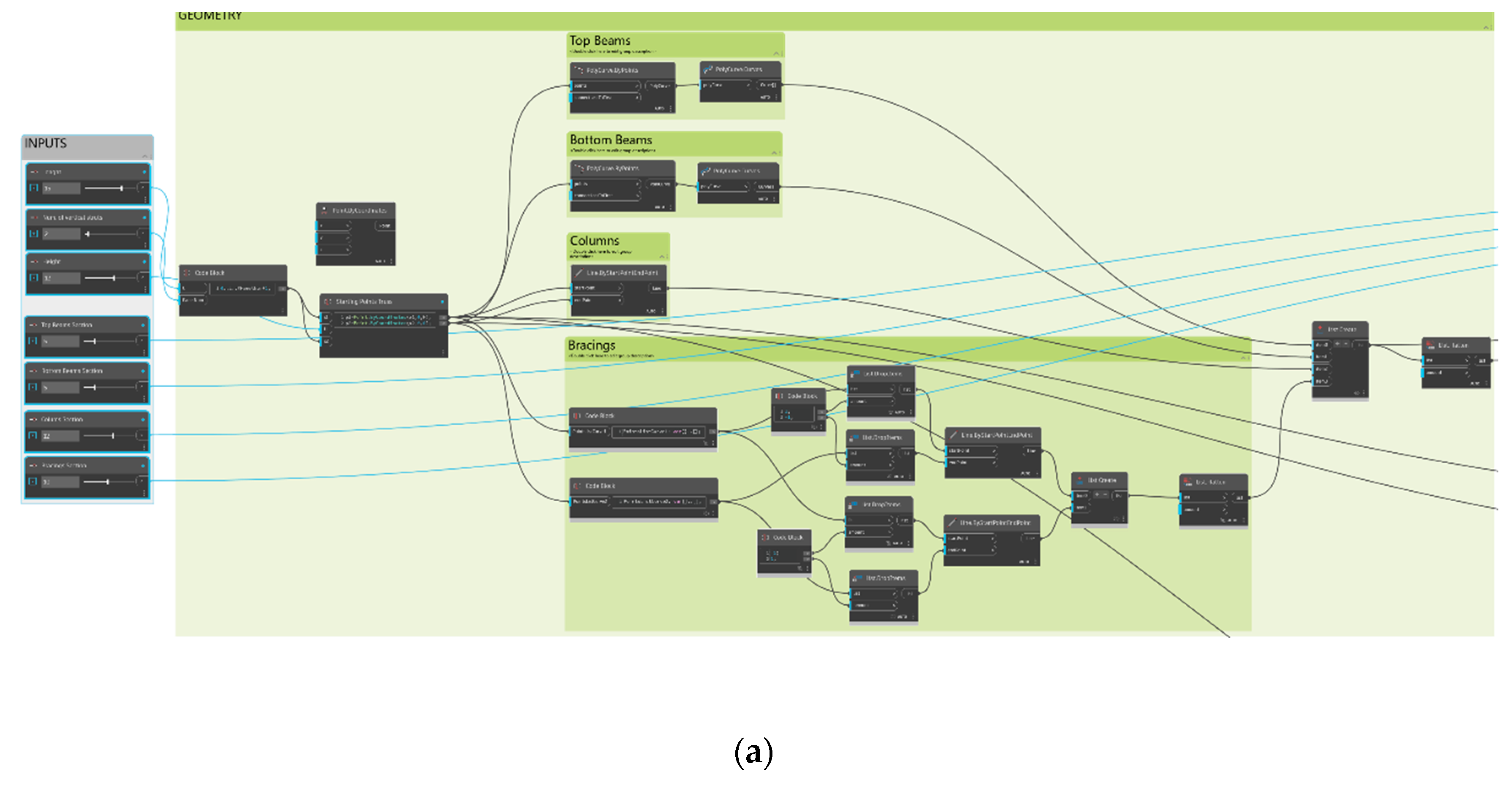

Create parametric trusses by using visual programming (

Figure 2a);

Perform structural analysis on RSA and retrieve the results through Dynamo (

Figure 2b);

Perform the first two steps in a loop along with GA operators to reach optimum design (

Figure 2c);

Import the optimized model on Revit to perform further enhancements such as LCA, cost analysis, etc. (

Figure 2d).

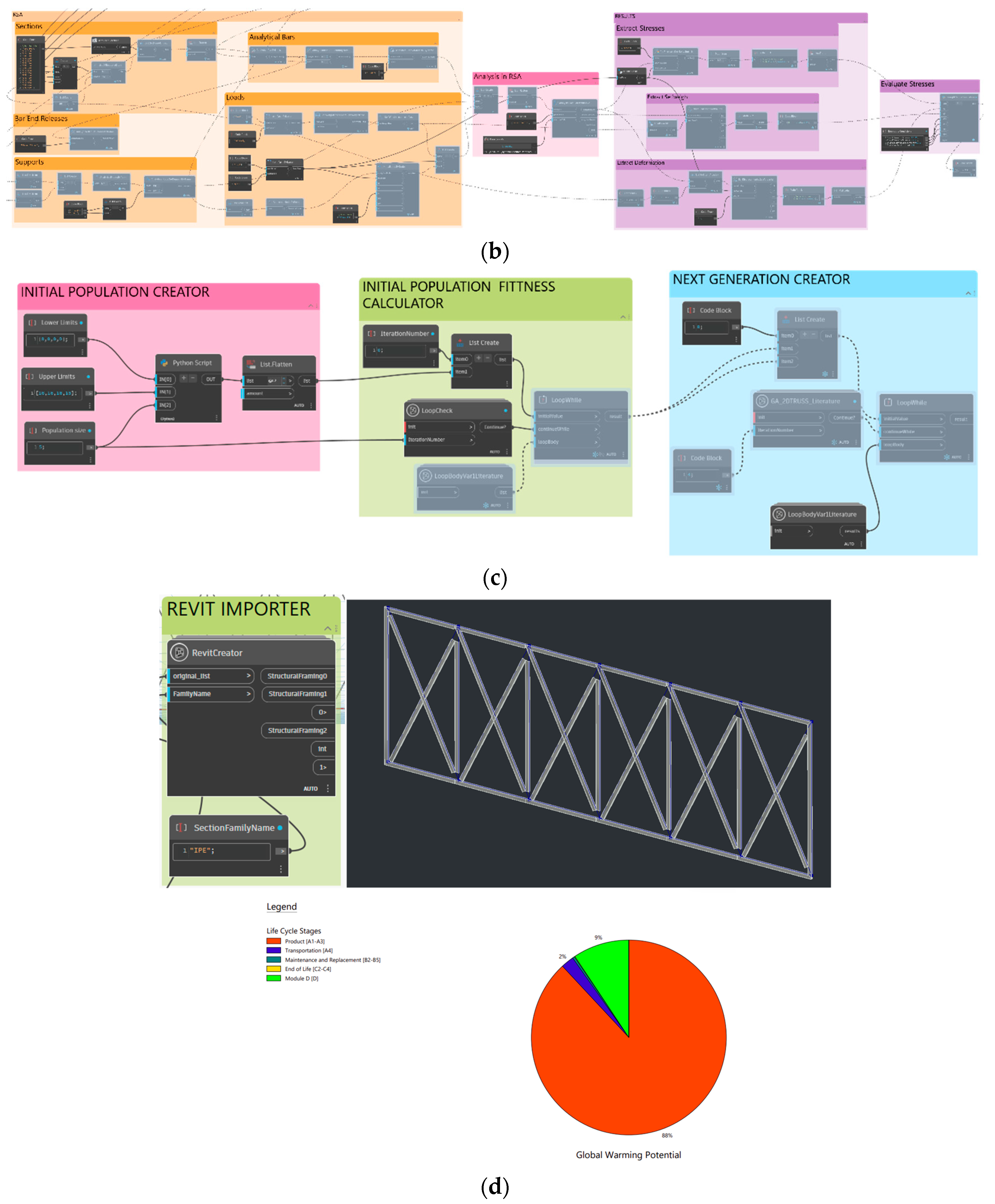

Moreover, the overview of the proposed workflow in this study is presented as a flowchart in simplified form in

Figure 3.

2.3. Parametric Model Creation

There are two common techniques to write computer programs, namely, VP and textual programming. The one in which graphical elements and visual syntax such as blocks, nodes, or diagrams are used to create program logic and flow is called visual programming. Since it requires no significant syntactic knowledge, it can be quite user-friendly and suitable for beginners. Consequently, VP has been used in this study for modeling through Dynamo.

Figure 2a illustrates the use of a number-integer slider, or code block nodes to specify various parameters such as truss height, truss length, the number of vertical struts, section indexes, the truss type, etc. These values are all expressed in millimeters (mm), aligning with the Project Unit setting in RSA, and can be determined as design variables. For this study, only sections are considered as design variables. To create a truss structure, the analytical nodes need to be defined. This can be achieved by either entering the code text “Point.ByCoordinates(0,0,0)” in the code block or utilizing the “Point.ByCoordinates” node. These points were then connected using the “PolyCurve.ByPoints” node, forming the elements of the truss structure. This section must be updated whenever different trusses want to be optimized.

2.4. Calculation and Retrieval of Results

Performing structural analysis is an essential step for structural optimization workflow. Although it is not reliable, many scholars use their own program or third-party libraries for this step as explained in the introduction section. In this study, an interaction has been established between Dynamo and RSA through the Structural Analysis for Dynamo package, which enables the creation of geometry and the assignment of simulation criteria, such as supports, loads, and sections, based on the geometrical input on Dynamo. To create the analytical members, the lines created in the previous section need to relate to the "AnalyticalBar.ByLines" node from the mentioned Dynamo package. Once the bars are created, sections and materials must be assigned on the created bars. Thereafter, supports, bar end releases, and loads must be defined as illustrated in

Figure 2b.

Dynamo drives the analysis process in RSA by using the “Analysis.CalculateWithSave” node. The information (analytical model, support and releases, load cases) that has been created in the previous section has to be connected to this node. This node performs the analysis and saves the model at a specified location (

Figure 2b). Subsequently, stresses, weight of structure, and displacements are needed for the calculation of the penalized objective function. To get the maximal stress for each bar, the “BarStress.GetMaxValuesList” node is utilized. For maximal values of displacement on the joints, the “BarDisplacement.GetMaxValuesList” node is utilized. The last necessary parameter for the weight score is to get the “selfweight” value of the structure. This can be achieved by using the “NodeReactions.GetValues” node and extracting the “FZ” results for the load case labeled as “Selfweight”. Evaluating the penalized objective function of each design option is crucial to rank the fitness of designs in structural optimization. That’s why the last part of the script o evaluates penalized objective functions by considering constraints as detailly explained in the background section. This process is implemented in the VP environment with the help of Python script as presented in

Figure 4.

2.5. Structural Optimization

To perform size optimization, section indexes can be set as a design parameter. That’s how the algorithm will try to find the best parameters for those inputs. The feature that allows users to do that is parametric modelling because as soon as an input is updated new model is automatically created and FEA can be performed for the new model. Optimization is working by running the steps explained in the previous section in a loop. To do that Custom node and the “LoopWhile” node have been used. By creating a custom node, all the nodes from

Figure 2a and

Figure 2b are consolidated into a single core node. This core node is central to all analyses. It takes the parameter to be optimized through its import port and, in turn, outputs the penalized objective function results. This process occurs repeatedly, ensuring continuous optimization. Henceforth, an initial population is needed for optimization. Thus, a Python script has been prepared to create a random initial population by defining lower-upper limits of solution sets, population size, and chromosome length. After creating initial populations, the outputs are connected to the “LoopWhile” node to process the steps explained above.

Figure 2c illustrates the nodes necessary for this operation. There are two custom nodes in the figure which are “LoopCheck” and “LoopBodyVar1”. The "LoopCheck" node allows defining the stopping criteria by taking the iteration number and comparing it with the input number. Once the iteration number exceeds the input number, it sends a stop signal to the "LoopWhile" node, and the loop ends. Subsequently, every individual in the initial population list must be sorted based on their penalized objective function results.

The parents that will create the succeeding generation of the population by GA operators are selected by using the obtained penalized objective function results from the initial population and binary tournament selection. Individuals with smaller objective function values are selected as the parents while the other individuals are not selected, and their genes are eliminated. This process is repeated by the next generation creator node group shown in

Figure 2c until a goal is met or a certain number of generations have been produced. The “LoopBodyVar1Literature” custom node contains two Python scripts and the same nodes from the initial population fitness calculator node group as illustrated in

Figure 5. First Python code uses GA operators such as selection, crossover, mutation, etc. to create new populations. Second Python code on the other hand performs like another selection operator of GA and chooses the best combinations from parents and children.

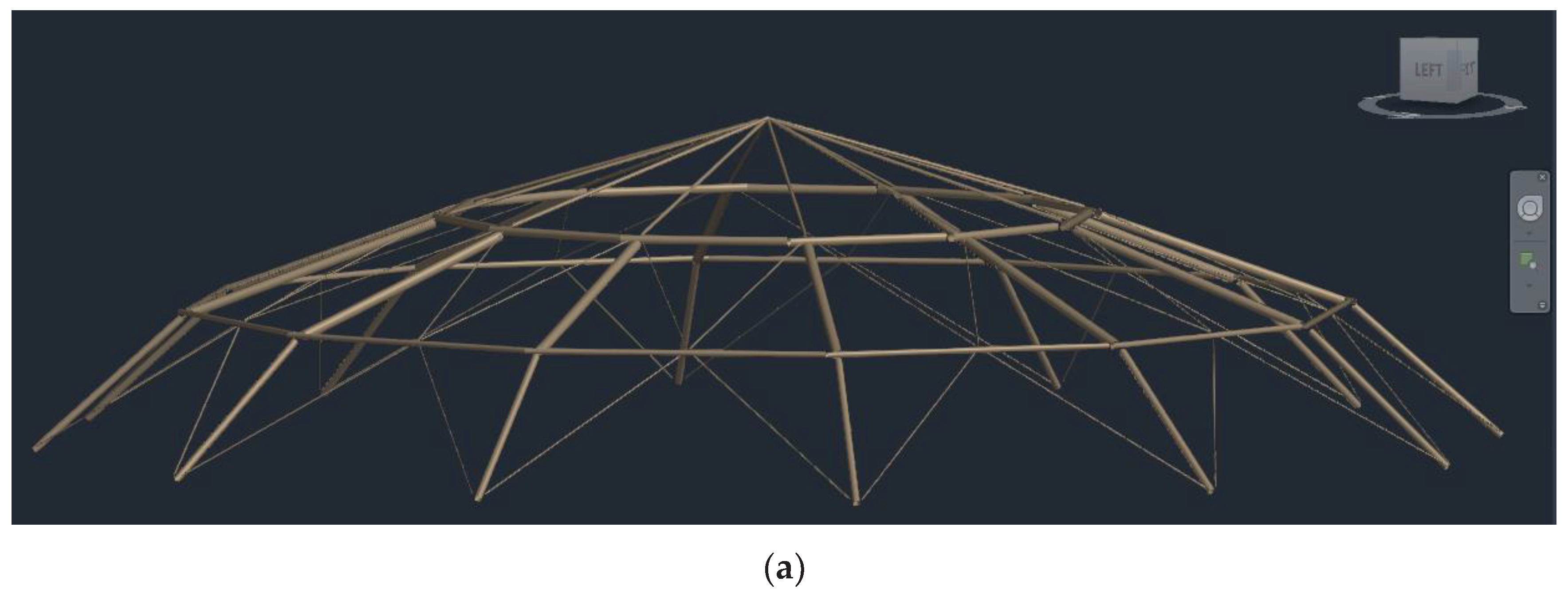

2.6. BIM Integration

In this section, some advantages of using the BIM environment in the optimization process are given with some examples. Revit’s features can be utilized by exporting the optimized model to Revit by employing the Dynamo script and the “RevitCreator” custom node (

Figure 2d). The structure after importing the truss model into Revit is shown in

Figure 6a. Prior to creating the model on Revit, cost and LCA analysis can be performed along with arranging connection details. Revit allows users to design connections and prepare more detailed models. This can be done in two ways. One, choosing the connection points manually on Revit, under the “structure tab”, on the “assembling steel connections” menu. Another way is doing all these steps parametrically with the help of Dynamo. In this study, to show the capabilities of BIM and Dynamo, this process is performed parametrically on Dynamo by employing the script presented in

Figure 6b.

Furthermore, Revit allows the user to utilize add-ins such as “Tally” which employs contribution assessments to illustrate the environmental impact of products or components in construction, considering factors such as ozone depletion, acidification, and global warming potential by performing LCA analysis which gives an opportunity to the AEC specialist who wishes to build an environment-friendly and sustainable design by performing a study on the project and providing a detailed report about the materials. Additionally, it provides focused views of global warming potential and embodied energy through graphics and charts, aiding designers in comparing specific assemblies and components. Examples are provided in the upcoming Results section.

3. Results

This section presents the numerical outcomes for several test problems. A comparison is made between the solution obtained from this study and solutions derived from various studies found in the open literature. These problems are solved with the proposed framework using a computer with Intel(R) Core i7-6700HQ CPU and 16,0 GB Installed RAM. Unlike literature studies, sections that exist in real-world applications have been considered as design variables to increase the adaptability of the proposed workflow for real-world examples. The average time spent on 100 analyses is approximately 2 hours. It is assumed that this time will be reduced with a computer having better hardware properties. All scripts and corresponding python code, along with instructions can be found on the respective dedicated GitHub repository for this study [

46].

3.1. Experimental Setup

Three different benchmark problems have been examined for validation of this study. The first one is the 10-bar truss example is a standardized test case in the field of structural optimization for those who want to evaluate and validate the effectiveness of proposed optimization techniques, and it is frequently used as a benchmark problem by researchers [

12,

14,

47,

48]. The geometry, support requirements, material properties, and boundary conditions for this 2D hanging truss presented in

Figure 7a have been adopted from the referenced study [

12]. The constraints are, stresses on member, which is limited to 172.25 MPa, and displacements on nodes which is limited to 50.8 mm. A discrete list that contains 41 cross-sectional areas has been sourced from the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC) and imported to RSA from the AISC database (AISC Edition 15.0 American hot rolled shapes). The HSRO (Hollow Structural Round Sections) family was used during the optimization. Detailed information about importing databases and using different section properties can be found on the referenced website [

49]. Population size and generation number has been determined as 20 through the execution of 10 distinct run cycle for this example.

The 36-bar truss problem, which is considerably difficult with 21 design variables, has emerged as another benchmark problem used among scholars [

14,

50,

51]. The configuration, dimensions, support requirements, material properties, and loading condition of this three-dimensional truss, presented in

Figure 7b, are sourced from the cited article [

50]. The constraints are stresses on member which is limited to 172.25 MPa and displacements are limited to 50.8 mm for node 4 in both negative z and y direction. A discrete list that contains 25 cross-sectional areas, which have been acquired from the AISC and imported to RSA from the AISC database (AISC Edition 15.0 American hot rolled shapes), has been prepared for this example. RB (Round Bars) family was used during the optimization. Population size and generation number has been determined as 40 through the execution of 2 distinct run cycle for this example.

The 120-bar dome truss was first solved by M.P. Saka in 1991 [

52]. Thereafter, other researchers employed this structure to test their algorithm [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. The configuration, dimensions, support requirements, material properties, loading, and boundary condition of this dome illustrated in

Figure 7c, are sourced from the referenced article [

52]. The constraints are stresses on the members which are limited to 240 MPa and displacements are limited to 10 mm for every node in the structure in the negative z direction. The elasticity module is taken as 210000 MPa and material density is taken as 7860 kg/m

3. 27 CHS (Circular Hollow Section) sections that comply with the provided limits were chosen from the BS EN 10219-2:2006 standard. Moreover, the buckling effect for elements under compression has been also taken into consideration. To calculate the critic load for buckling, a Python code was created with the formulations taken from AISC [

58] regulation. Population size and generation number has been determined as 20 through the execution of 10 distinct run cycle for this example.

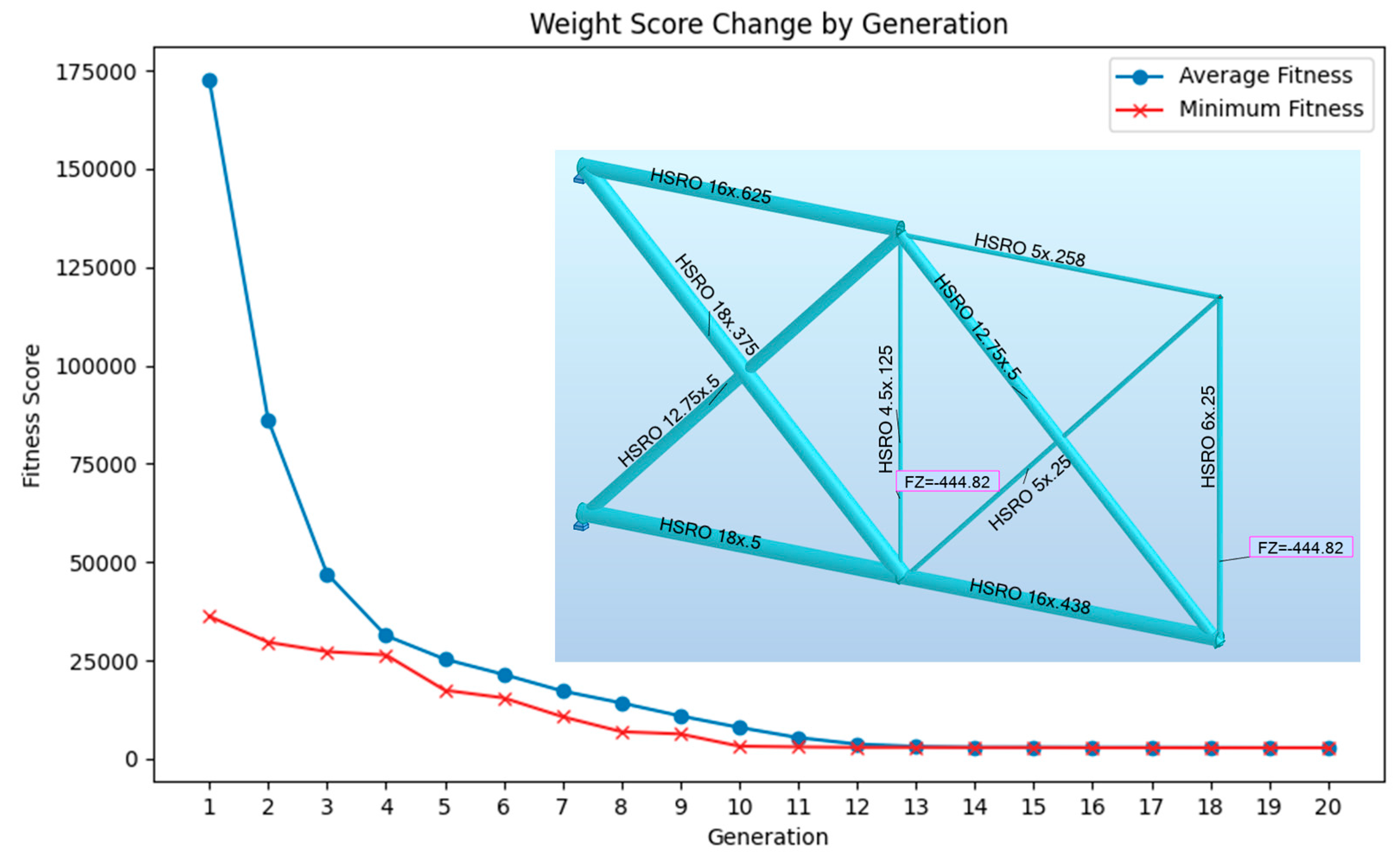

3.2. 10-Bar 2D Truss

The results found for the 10-bar truss are shown and compared with the studies taken from the literature in

Table 1. The table reveals that the weight obtained after optimization is higher than the solutions obtained from previous studies. However, since the aim of the study is to demonstrate the usability of the proposed methodology, the solution obtained is acceptable because the study conducted by Camp et al. required an average of approximately 10,000 truss analyses with 24 separate run cycle [

47] to converge the solution, exhibiting a magnification of 62.5 times in comparison with analysis number that has been performed for this study. On the other hand, Jafari et all. [

23] needed 113.25 times more analysis to obtain the result presented in

Table 1. In addition to the table, the weight score change chart and the final version of optimized structure with sections found have been presented in

Figure 8.

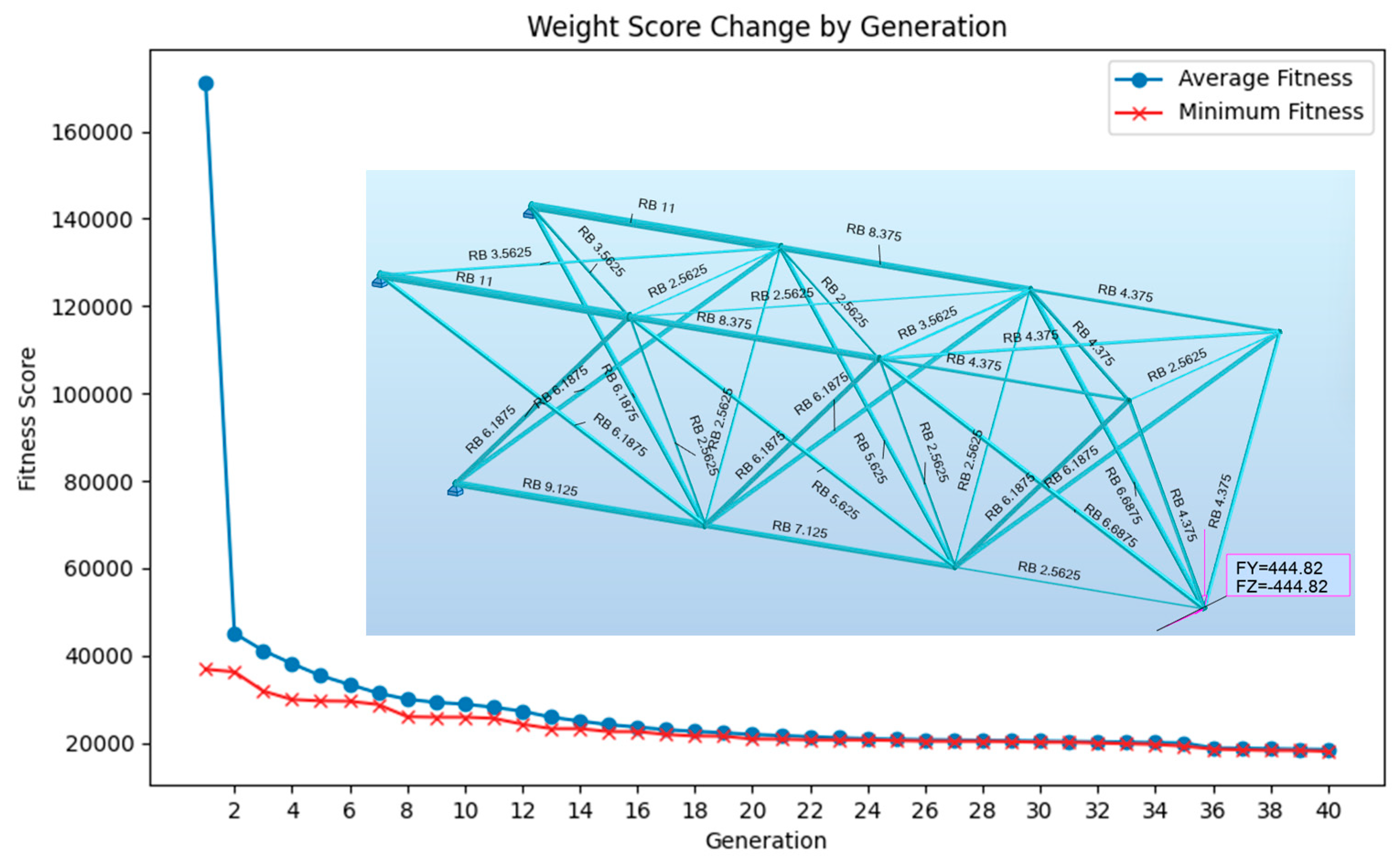

3.3. 36-Bar 3D Truss

The comparison of the results, the number of analyses performed to obtain that truss in a single run cycle, and separate runs performed during the study for 36-bar truss are depicted in

Table 2. The main drawback of proposed framework is increasing calculation times for structures with more elements. This downside limited the number of separate runs performed for this problem. Also results show that utilized GA performs poor with current parameter settings for the problems that have considerably more variables as this example. Additionally,

Figure 9 presents the weight score and final version of the optimized structure.

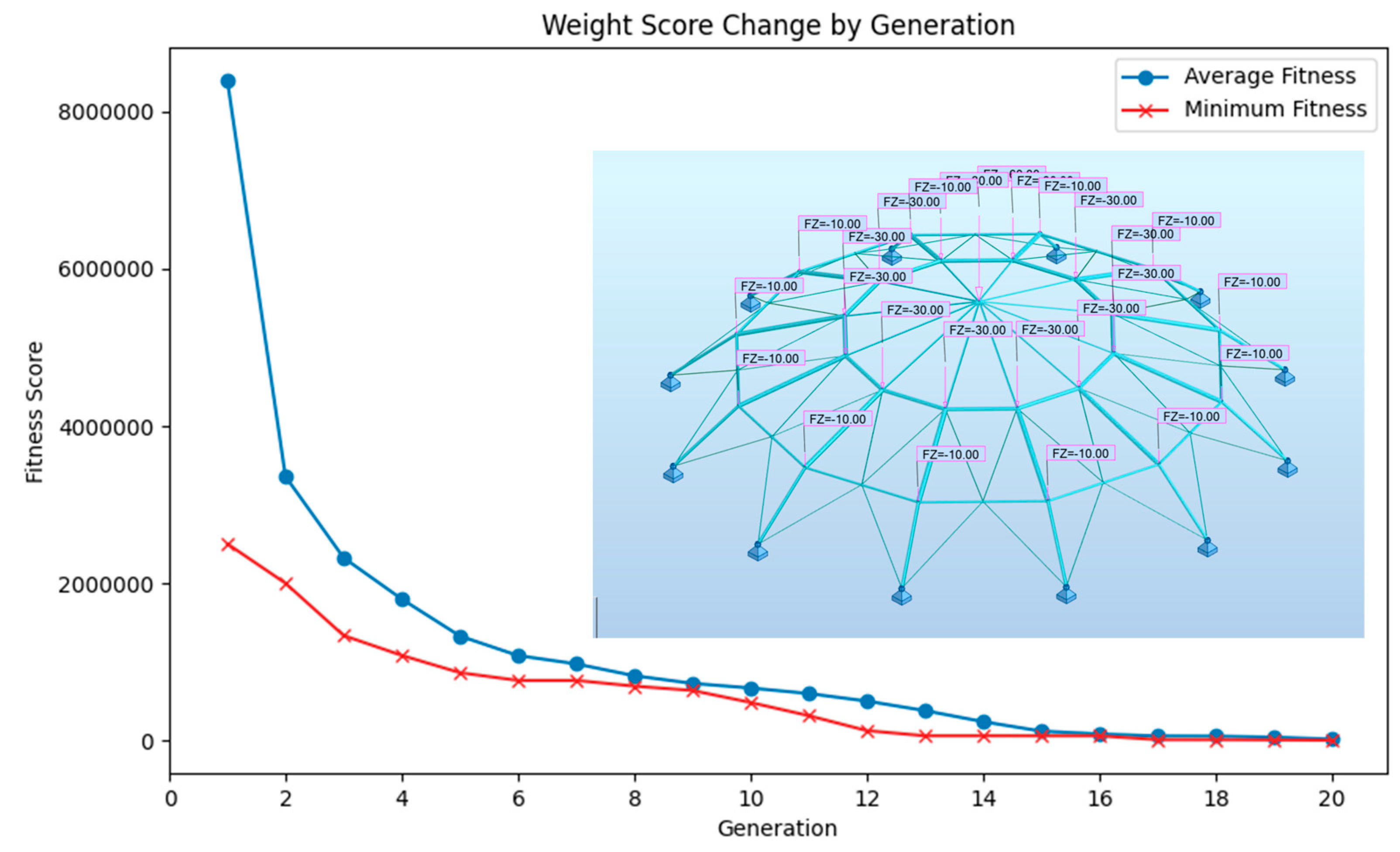

3.4. 120-Bar Dome Truss

The example aims to find suitable sections that give minimum weight while satisfying given constraints for 120 elements that are divided into 7 groups from the list that contains 27 different cross-sectional areas. Results for 120-bar dome truss are presented in

Table 3 along with their comparison to literature results. It is worth noting that conducting additional runs and increasing the number of analyses for the same study is expected to yield better weights since the study [

57] needed 84000 overall analyses and study [

54] 100 separate run cycle to find the results depicted in

Table 3. It is also important to mention that in this study [

57] the displacement constraints are taken as ±5 mm different than referenced study [

52] resulted higher structure weight. Also. the referenced studies all used continues design variables while discrete sets were utilized in this manuscript. The reason for choosing this problem for the result section is to demonstrate that the proposed algorithm is effective and performs well as the number of elements increases. The results indicate that the proposed methodology can be applied to complex structures in future studies. Nevertheless, it should be noted that conducting one analysis for a problem of this scale took about 50 seconds. Lastly,

Figure 10 presents the optimized structure along with the weight score change by generation chart.

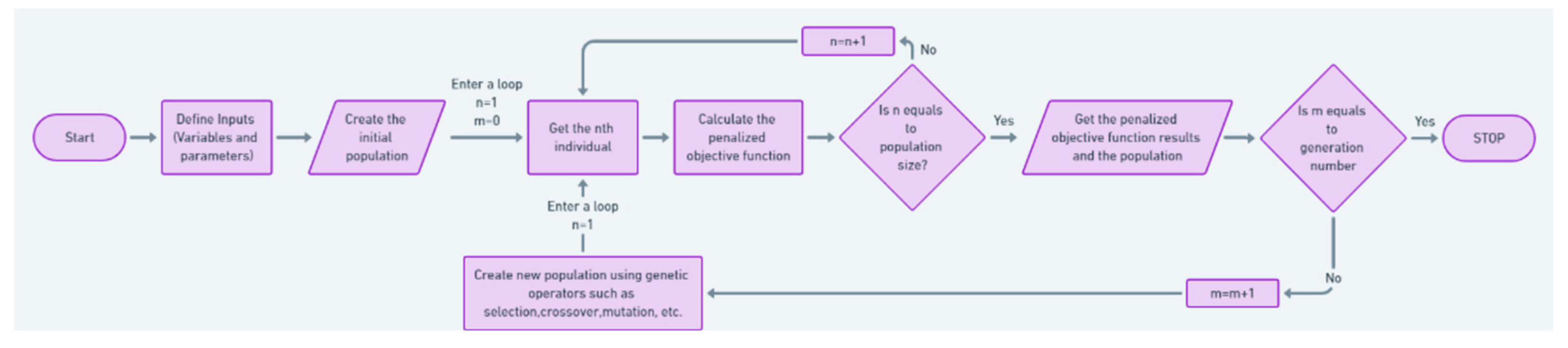

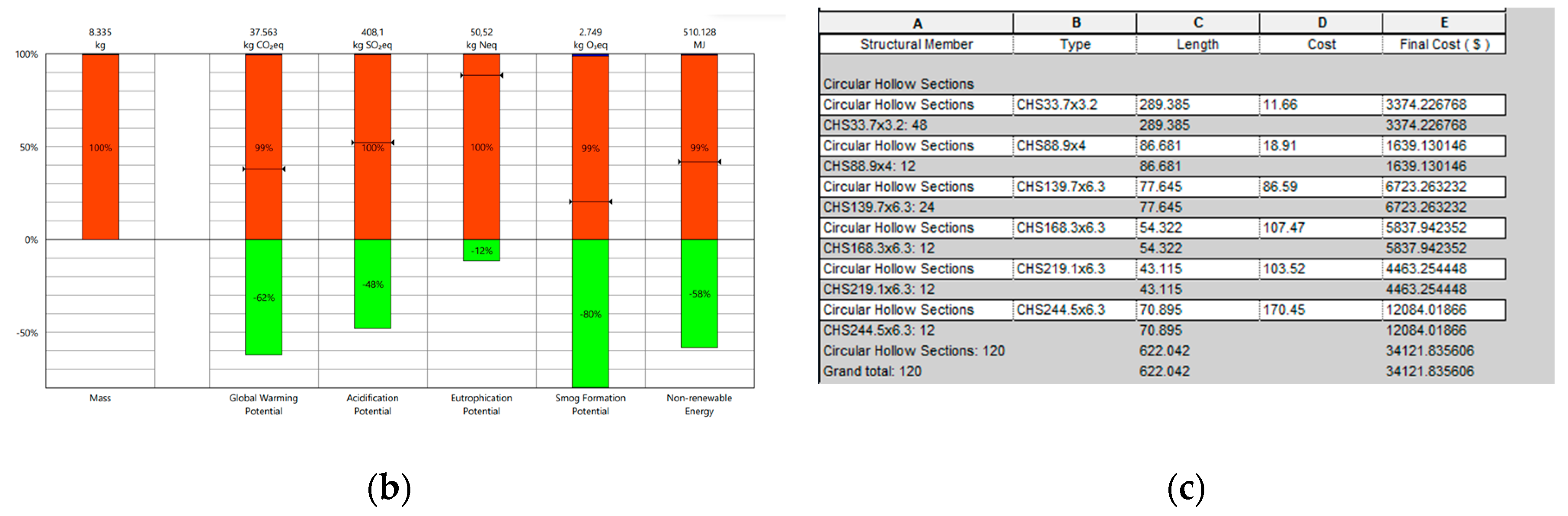

3.4.1. LCA and Cost Analysis for 120-Bar Truss

This section of the study provides LCA and cost analysis results of the optimized 120-bar dome truss obtained using the explained methodology. As the first step, the best model after optimization has been imported into Revit from Dynamo using the “Revit importer” custom node. Once the model is ready in Revit, as shown in

Figure 11a, LCA analysis can be performed by using “Tally”. After the analysis, a detailed report is generated, which includes information on factors such as global warming potential, acidification, and smog formation potential, as some part of it demonstrated in

Figure 11b. For cost analysis, a bill of quantity table has been created on Revit, as shown in

Figure 11c. Fields in this table can be adjusted by specific needs. To give an example, unit prices have been obtained from the referenced website [

59], and the total cost of the structure has been calculated automatically within the table.

4. Discussion

In this section, a transparent comment has been made about what aspects of this study could have been improved or were not fully addressed along with a brief discussion about the results found in this study, and future deployment.

Firstly, the proposed workflow can be enhanced by employing RSA-API instead of employing the Dynamo package for interaction, which will give broad control over the analysis part of the workflow. The package restricts the optimization process and the ability to use the full performance of RSA because any changes inside this package are not possible. If there is a problem during the optimization caused by this package, it is challenging to detect and solve that problem. That’s why using API to perform FEM analysis on RSA is looking better option for future studies. Also, it is assumed that utilizing API would decrease the calculation time which helps the designer to reach the optimum solutions with less time and the scholar to perform more analysis and present more competitive results with literature.

Lastly, the definitions of the initial population size, mutation rate, and elite rate significantly affect the results of the examples. Additionally, the number of design variables and the size of the list containing these variables have a substantial influence on finding optimal results. While having a large list of design parameters allows for the evaluation of various options, it also comes at a significant time cost. The primary challenge of the proposed method is the time required for certain tasks, particularly when importing the model into RSA, assigning boundary conditions, and conducting the analysis. These processes consume a significant amount of time compared to methods where all operators and programs are coded within a single software using one programming language where the generation number does not impose a limitation on the study. However, in this study, as the generation number increases, the waiting time also rises due to issues like RAM leaks. Improving the interaction between RSA and Dynamo might reduce the model creation time in RSA which could help address this problem. Due to these reasons, the separate run number and analysis number were kept low and as soon as a solution close to the literature results was found, the optimization process was terminated. Despite the reasons explained so far, the solutions obtained by using the model proposed in this thesis are meaningful from the viewpoint of engineering manner and computational efforts. Overall, the results obtained are approximately 10% higher than those in the literature. This difference is considered acceptable given that the focus of this thesis is to establish a workflow for structural optimization using visual programming, parametric modeling, and other BIM tools, rather than coding a metaheuristic algorithm that works best among the ones created in the literature.

5. Conclusions

Even though structural optimization with meta-heuristic algorithms is a well-known subject, its application and utilization in real-world problems are not common because of unfriendly software interfaces and the vast amount of programming expertise demand. This gap in the literature is approached utilizing technological advancements like Parametric design, VP, BIM, etc. through software like Dynamo, Revit, and RSA during the optimization process. The aim of this manuscript is to create a structural optimization methodology that integrates the VP, parametric modeling, and the BIM tools to obtain a robust optimization framework. This methodology was then validated by comparing the results of several 2D and 3D benchmark problems from the open literature. Concurrently, to show the advantages of using BIM during the optimization process, LCA and Cost analysis have been added to the proposed methodology and results sections. Dynamo’s ability to become a bridge between RSA and Revit made this study possible. In summary, this study has laid a solid foundation for further research and innovation in the field of structural optimization. The combination of BIM, metaheuristic algorithms, and advanced technologies opens new possibilities for creating more sustainable, cost-effective, and efficient structures in the years to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and F.Y.; methodology, R.M., F.Y., and V.T.; software, F.Y.; validation, F.Y.; formal analysis, F.Y.; investigation, R.M. and F.Y.; resources, R.M.; data curation, F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.Y.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and V.T.; visualization, F.Y.; supervision, R.M. and V.T.; project administration, R.M. and V.T.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the research funds of the Endowed Professorship in Digital Engineering and Construction (DEC) at the Institute of Technology and Management in Construction (TMB) of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). The author wishes to acknowledge the support provided by the KIT Publication Fund of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in supplying the APC.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data for the configurations used in this study are available through in the following references: 10-bar truss [

12], 36-bar truss [

50], and 120-bar dome [

52].

Computer Code and Software: The generated computer code along with animations, and instructions are conveniently provided in the respective GitHub repository dedicated for this project [

46].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gordon, J.E. Structures: Or Why Things Don’t Fall down (Appendix 4) 1978.

- Maalek, R.; Maalek, S. Repurposing Existing Skeletal Spatial Structure (SkS) System Designs Using the Field Information Modeling (FIM) Framework for Generative Decision-Support in Future Construction Projects. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 19591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, L.; Wang, Q. Structural Optimization in Civil Engineering: A Literature Review. Buildings 2021, 11, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiary, N.; Allinger, P.; Friedrich, M.; Mulfinger, F.; Sauter, J.; Puchinger, M. A New Approach for Sizing, Shape and Topology Optimization. Journal Of Materials & Manufacturing 1996, 105, 745–761. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Fan, F.; Sun, Y. Shape Optimization of Free-Form Grid Structures Based on the Sensitivity Hybrid Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 44, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P.W.; Klarbring, A. An Introduction to Structural Optimization; Springer Science & Business Media, 2008; Vol. 153; ISBN 1402086660.

- Baykasoğlu, A.; Baykasoğlu, C. Weighted Superposition Attraction-Repulsion (WSAR) Algorithm for Truss Optimization with Multiple Frequency Constraints. Structures 2021, 30, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, H.; Ye, J.; Zhao, Y.; Min Xie, Y. Layout Optimization of Truss Structures with Modular Constraints. Structures 2023, 55, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolpe, M.; Stolpe matst, M. Truss Optimization with Discrete Design Variables: A Critical Review. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2015 53:2 2015, 53, 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xia, Y. A Hybrid Intelligent Genetic Algorithm for Truss Optimization Based on Deep Neutral Network. Swarm Evol Comput 2022, 73, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; Charkaoui, A.; Hassan, N.M.; Bahroun, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Yao, Q.; et al. You May Also like Nonlinear Stress Analysis of Key Joints of Steel Truss Bridge Enhancing Mechanical Properties of Cellular Core Sandwich Panels: A Review of Topological Parameters and Design Improvements Research on Parametric Finite Element Analysis Method of Escalator Truss Truss Optimization Using Genetic Algorithm and FEA. J Phys Conf Ser 1965, 12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, S.; Krishnamoorthy, C.S. Discrete Optimization of Structures Using Genetic Algorithms. Journal of Structural Engineering 1992, 118, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, K.M. GADO: A Genetic Algorithm for Continuous Design Optimization; Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies, 1998; ISBN 0591759950.

- Groenwold, A.A.; Stander, N.; Snyman, J.A. A Regional Genetic Algorithm for the Discrete Optimal Design of Truss Structures. Int J Numer Methods Eng 1999, 44, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toǧan, V.; Daloǧlu, A.T. An Improved Genetic Algorithm with Initial Population Strategy and Self-Adaptive Member Grouping. Comput Struct 2008, 86, 1204–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Birattari, M.; Stutzle, T. Ant Colony Optimization. IEEE Comput Intell Mag 2006, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks 4, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzimehr, V.; Topal, U.; Das, A.K.; Vo-Duy, T. Bonobo Optimizer Algorithm for Optimum Design of Truss Structures with Static Constraints. Structures 2023, 50, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, T.; Kripka, M.; Togan, V.; Yepes, V.; Rao, R.V. Usage of Optimization Techniques in Civil Engineering During the Last Two Decades. 2019.

- Aydın, Z. Size, Layout and Tendon Profile Optimization of Prestressed Steel Trusses Using Jaya Algorithm. Structures 2022, 40, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kottath, R.; Tejani, G.G. Ameliorated Follow The Leader: Algorithm and Application to Truss Design Problem. Structures 2022, 42, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, F.K.J.; Ozturk, C.; Dansheng, W.; Mahmood, M.; Al-Azzawi, O.; Al-Jemely, A. Sizing and Layout Optimization of Truss Structures with Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. Structures 2021, 30, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Salajegheh, E.; Salajegheh, J. Optimal Design of Truss Structures Using a Hybrid Method Based on Particle Swarm Optimizer and Cultural Algorithm. Structures 2021, 32, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xia, Y. A Hybrid Intelligent Genetic Algorithm for Truss Optimization Based on Deep Neutral Network. Swarm Evol Comput 2022, 73, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu-Huu, T.; Pham-Van, S.; Pham, Q.H.; Cuong-Le, T. An Improved Bat Algorithms for Optimization Design of Truss Structures. Structures 2023, 47, 2240–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biabani, F.; Shojaee, S.; Hamzehei-Javaran, S. A New Insight into Metaheuristic Optimization Method Using a Hybrid of PSO, GSA, and GWO. Structures 2022, 44, 1168–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; Charkaoui, A.; Hassan, N.M.; Bahroun, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Yao, Q.; et al. Truss Optimization Using Genetic Algorithm and FEA. J Phys Conf Ser 2021, 1965, 012134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalek, S.; Maalek, R.; Maalek, B. Intrinsic Properties of Composite Double Layer Grid Superstructures. Infrastructures (Basel) 2023, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.T.; Lieu, Q.X.; Kang, J.; Lee, J. A Novel Deep Unsupervised Learning-Based Framework for Optimization of Truss Structures. Eng Comput 2023, 39, 2585–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicconi, P.; Germani, M.; Bondi, S.; Zuliani, A.; Cagnacci, E. A Design Methodology to Support the Optimization of Steel Structures. Procedia CIRP 2016, 50, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computers & Structures Inc Sap 2000. Sap 2000 2019.

- Kaveh, A.; Mirzaei, B.; Jafarvand, A. Shape-Size Optimization of Single-Layer Barrel Vaults Using Improved Magnetic Charged System Search. International Journal of Civil Engineering 2014, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Artar, M.; Carbas, S. Discrete Sizing Design of Steel Truss Bridges through Teaching-Learning-Based and Biogeography-Based Optimization Algorithms Involving Dynamic Constraints. Structures 2021, 34, 3533–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasani, A.; Patel, R.; Savsani, V.; Savsani, P. Parametric Analysis of Genetic Algorithm Toolbox for Truss Problem Optimization. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering 2020, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirniazmandan, S.; Alaghmandan, M.; Barazande, F.; Rahimianzarif, E. Mutual Effect of Geometric Modifications and Diagrid Structure on Structural Optimization of Tall Buildings. Architectural science review 2018, 61, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, S.; Lagaros, N.D. Topology Optimization of Framed Structures Using SAP2000. Procedia Manuf 2020, 44, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, Q.; Gilbert, M.; Shepherd, P.; Rankine, C.; Pritchard, T.; Reale, V. Optimization-Driven Conceptual Design of Truss Structures in a Parametric Modelling Environment. Structures 2022, 37, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-R.; Zhang, Y.; Kong SAR, H.; Xiao, J. A Framework to Automate Reliability-Based Structural Optimization Based on Visual Programming and OpenSees. 8th International Conference on Construction Engineering and Project Management, Hong Kong, China, 8 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Ning, C.; Wei, Y. MOPSO for BIM: A Multi-Objective Optimization Tool Using Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm on a BIMbased Visual Programming Platform. Hello Culture 2019, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Daloğlu, A.; Armutçu, M. Optimal Design of Plane Steel Frames with Genetic Algorithm (in Turkish). Teknik Dergi 1998, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, F. do P.; Arenales, M.N. The Constrained Compartmentalised Knapsack Problem. Comput Oper Res 2007, 34, 2109–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species: A Facsimile of the First Edition; Harvard University Press, 1964; ISBN 0674637526.

- Coello Coello, C.A. Theoretical and Numerical Constraint-Handling Techniques Used with Evolutionary Algorithms: A Survey of the State of the Art. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2002, 191, 1245–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, J.; Deb, K. Pymoo: Multi-Objective Optimization in Python. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 89497–89509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniay, Ö. Penalty Function Methods for Constrained Optimization with Genetic Algorithms. Mathematical and Computational Applications 2005, 10, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurfeyzullah/Structural-Optimization-with-VP. Available online: https://github.com/ugurfeyzullah/Structural-optimization-with-VP (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Camp, C. V.; Bichon, B.J. Design of Space Trusses Using Ant Colony Optimization. Journal of Structural Engineering 2004, 130, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Qian, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, H. Enhanced Particle Swarm Optimization for Size and Shape Optimization of Truss Structures. Engineering Optimization 2017, 49, 1939–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URL-23 Robot Structural Analysis 2018 Help | Section Database | Autodesk. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/RSAPRO/2018/ENU/?guid=GUID-727CAC1A-7ABE-4986-B7A5-4E31ADF1A6AA (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Ringertz, U.T. ON METHODS FOR DISCRETE STRUCTURAL OPTIMIZATION. Engineering Optimization 1988, 13, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, J.F.; Groenwold, A.A. Sizing Design of Truss Structures Using Particle Swarms. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2003, 25, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, M.P.; Ulker, M. Optimum Design of Geometrically Nonlinear Space Trusses. Comput Struct 1991, 41, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriles, P.V.S.Z.; Fonseca, L.G.; Barbosa, H.J.C.; Lemonge, A.C.C. Rank-Based Ant Colony Algorithms for Truss Weight Minimization with Discrete Variables. Commun Numer Methods Eng 2006, 23, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenau, C.; Rottschäfer, J.; Thierauf, G. An Advanced Evolutionary Strategy with an Adaptive Penalty Function for Mixed-Discrete Structural Optimisation. Advances in Engineering Software 2005, 36, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejani, G.G.; Savsani, V.J.; Patel, V.K. Modified Sub-Population Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization for Design of Truss Structures with Natural Frequency Constraints. Mechanics Based Design of Structures and Machines 2016, 44, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Aickelin, U.; Khorshidi, H.A.; Shishehgarkhaneh, M.B. Shape and Size Optimization of Truss Structures by Chaos Game Optimization Considering Frequency Constraints. J Adv Res 2022, 41, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooshkbaghi, M.; Kaveh, A. Sizing Optimization of Truss Structures with Continuous Variables by Artificial Coronary Circulation System Algorithm. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology - Transactions of Civil Engineering 2020, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AISC Specification for the Design, Fabrication & Erection of Structural Steel for Buildings 1961.

- URL-23 ParkerSteel - UK Steel Stockholders. Available online: https://www.parkersteel.co.uk/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).