Submitted:

30 March 2024

Posted:

01 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

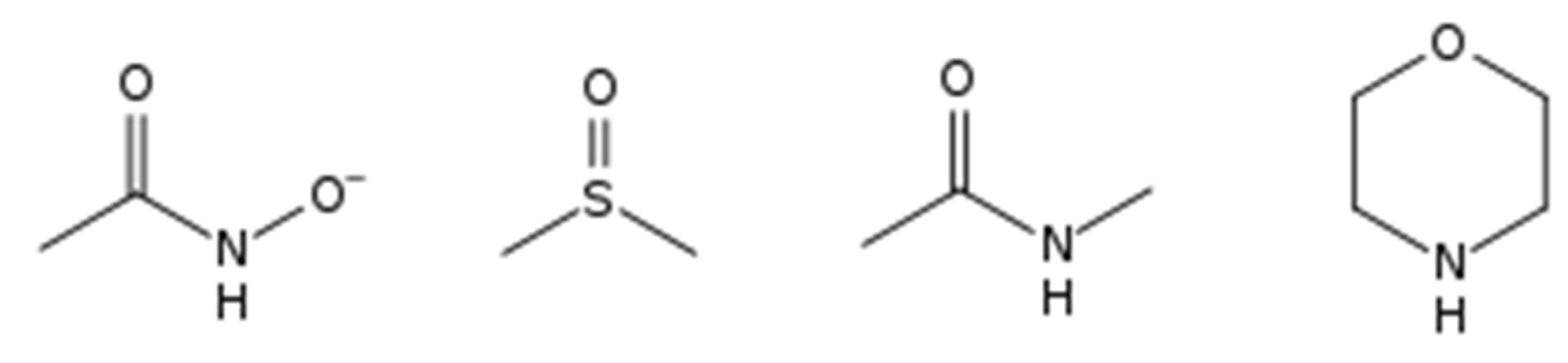

2.1. De Novo Design of Putative Auxins and Molecular Decoys

2.2. Machine Learning

2.3. Molecular Modelling of Auxins

2.3.1. Mixed Solvent Molecular Dynamics

2.3.2. Assessment of Pocket Solvation and Its Role in Auxin Recognition

2.3.3. Molecular Dynamics

2.3.4. Coarse Metadynamics

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. De novo Design of Putative Auxins and Decoys

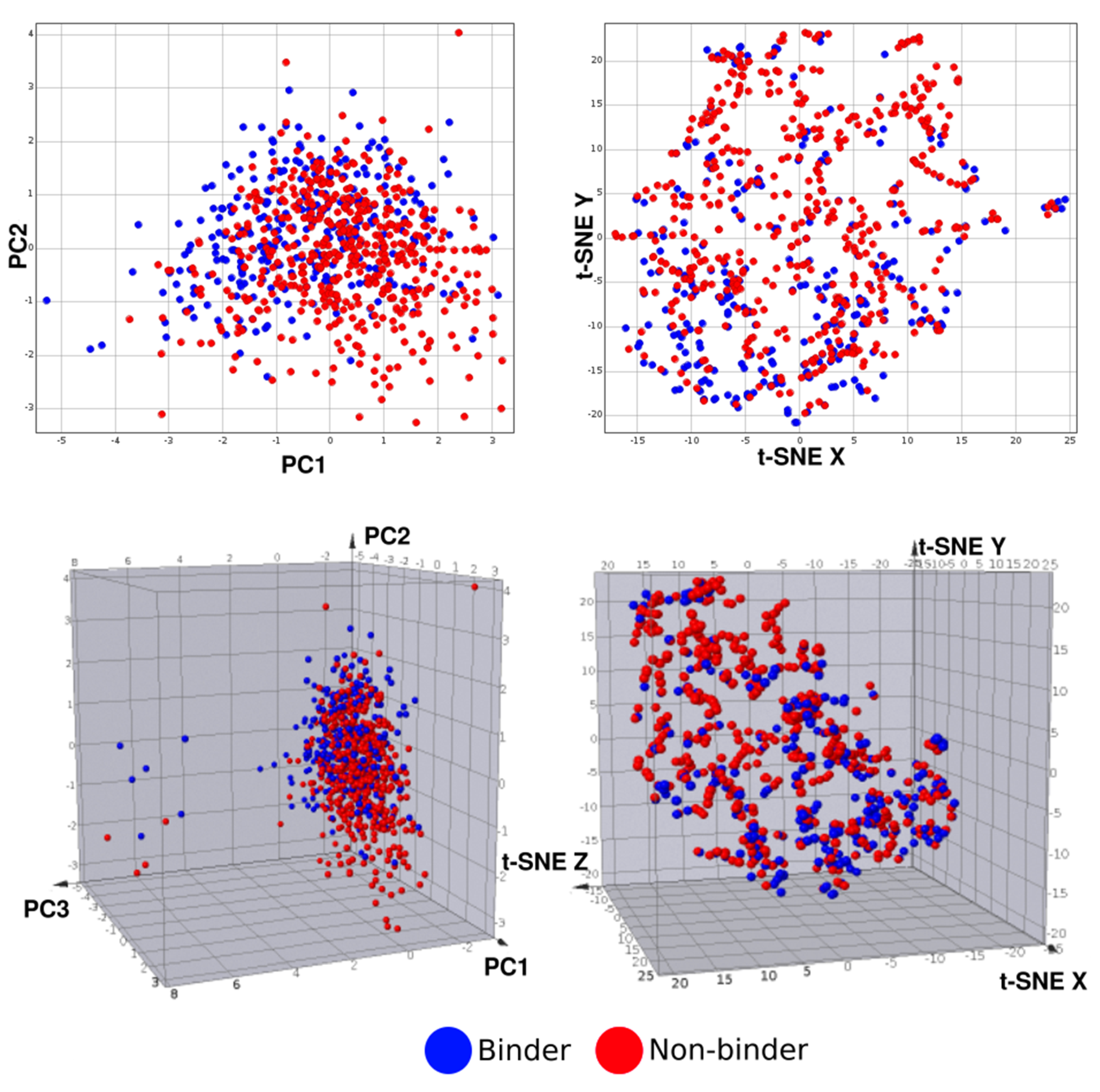

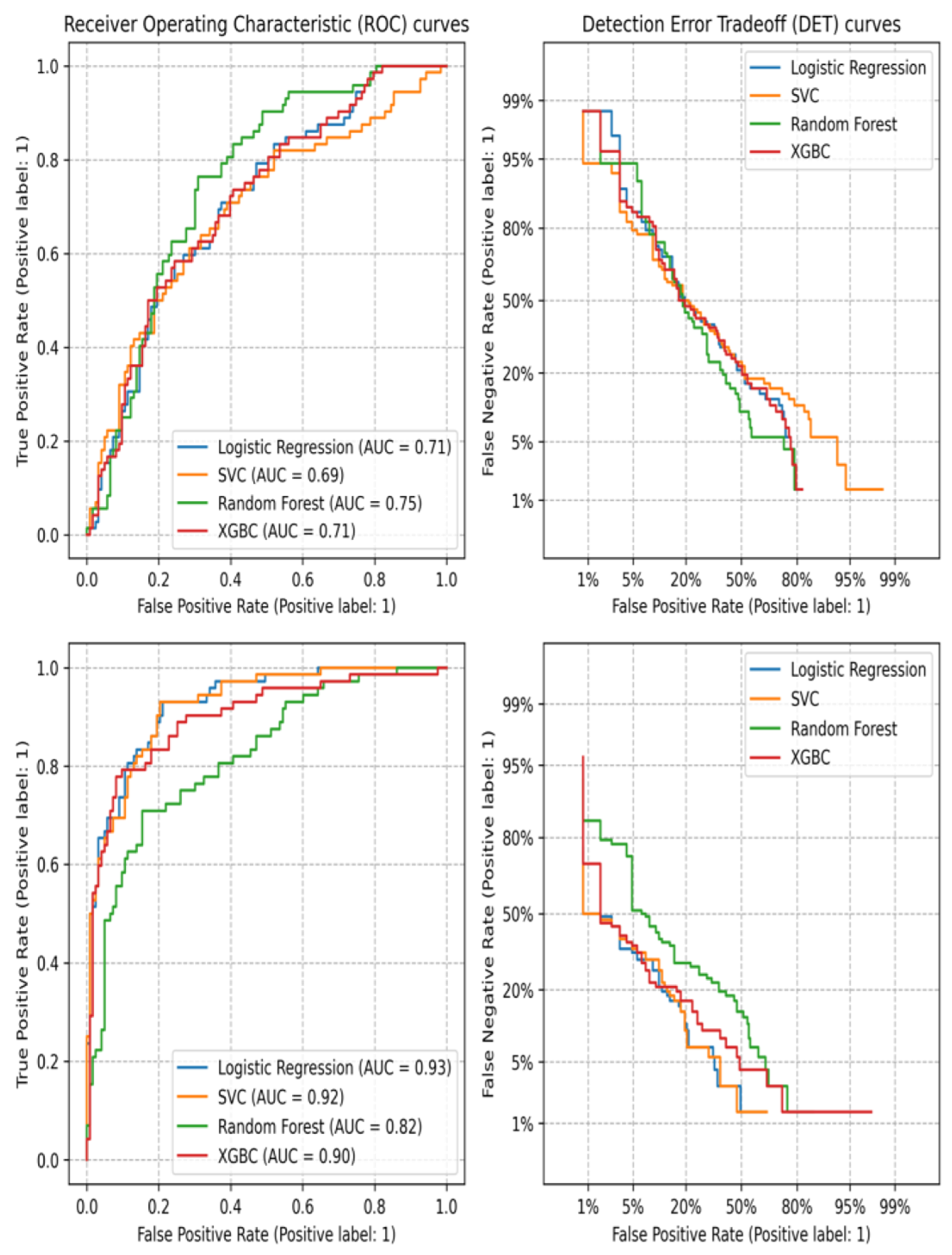

3.2. Machine Learning

3.3. Molecular Modelling of Auxins

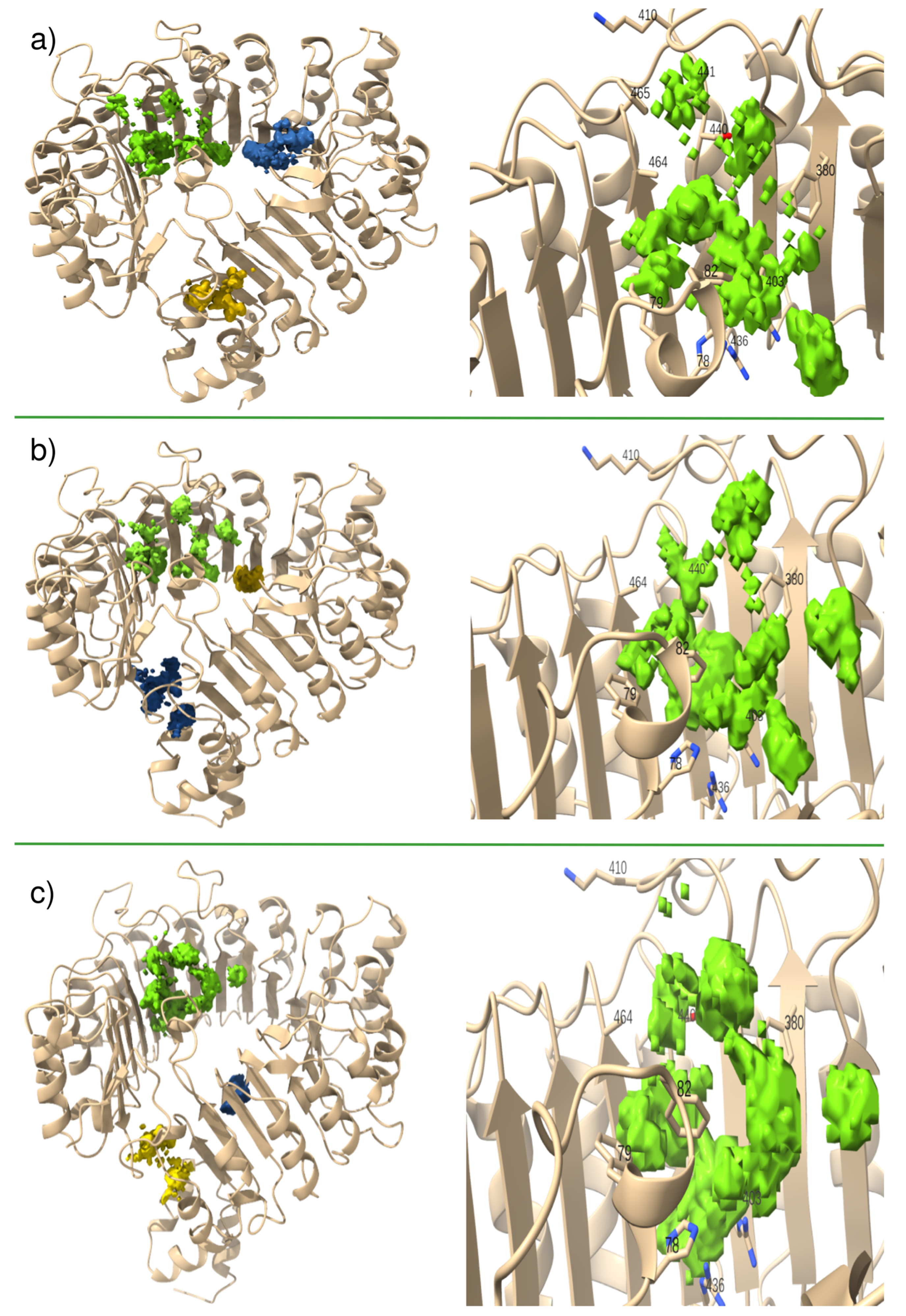

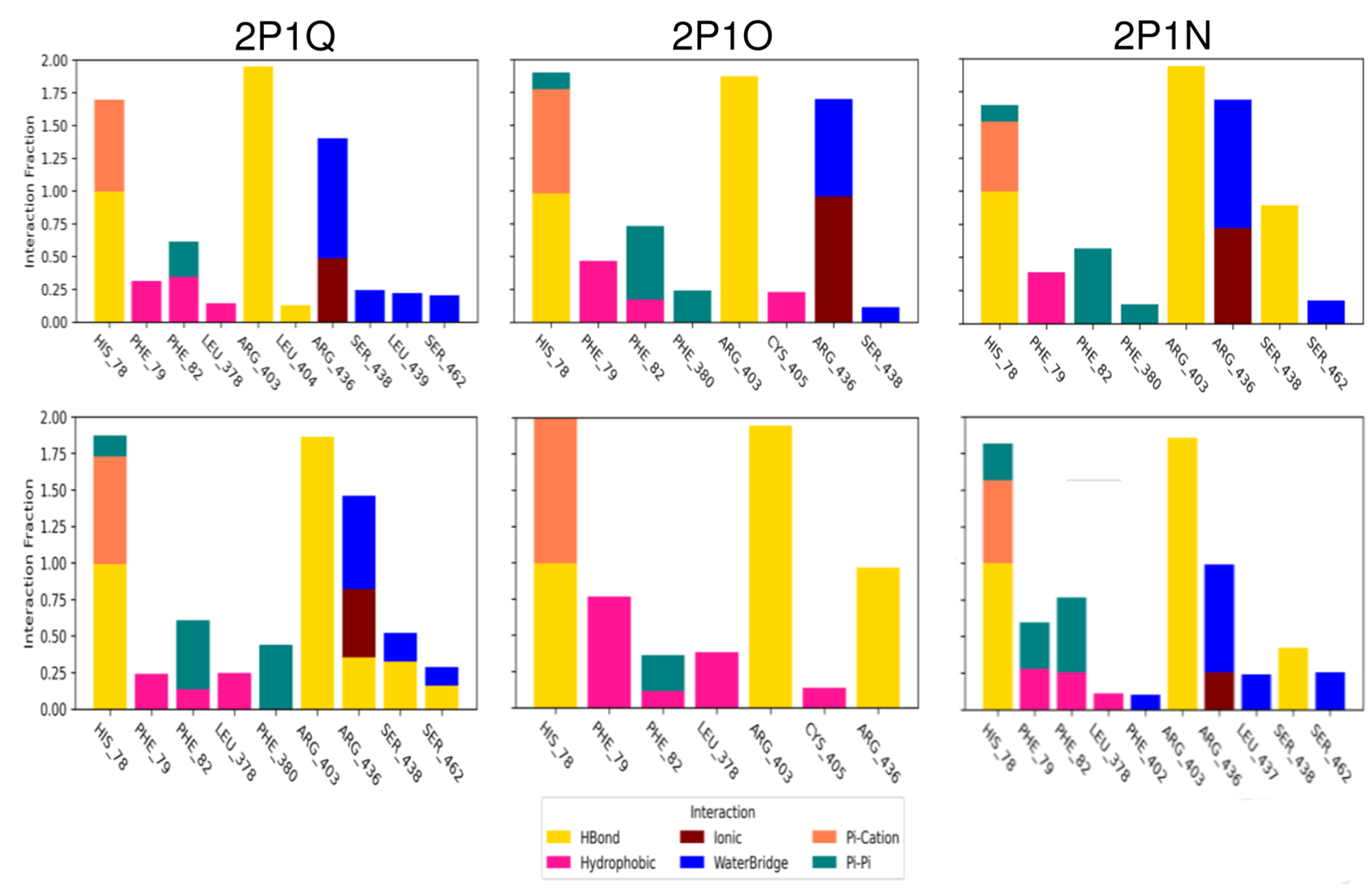

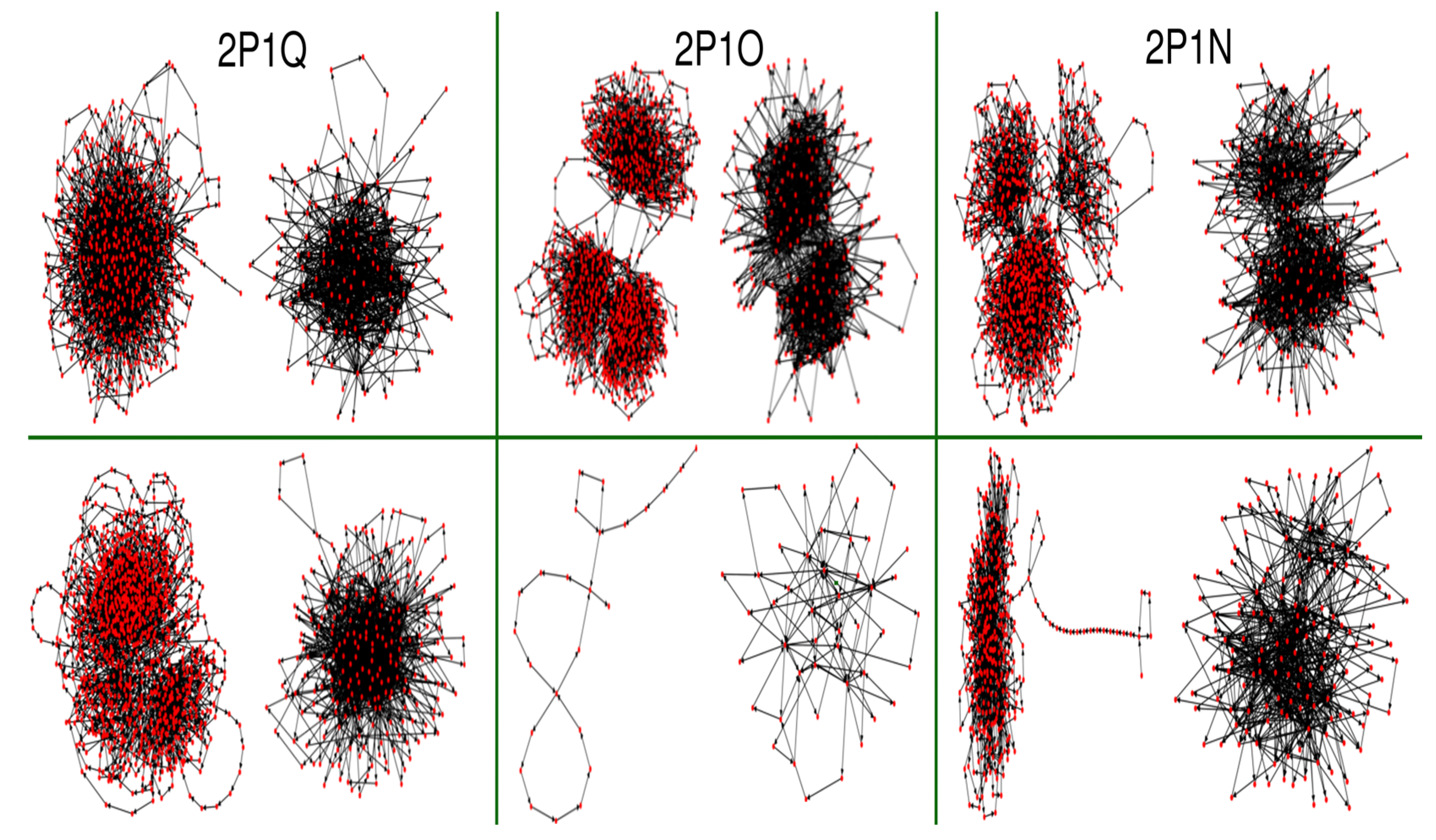

3.3.1. Mixed Solvents Molecular Dynamics

3.3.2. Assessment of Pocket Solvation and Its Role in Auxin Recognition

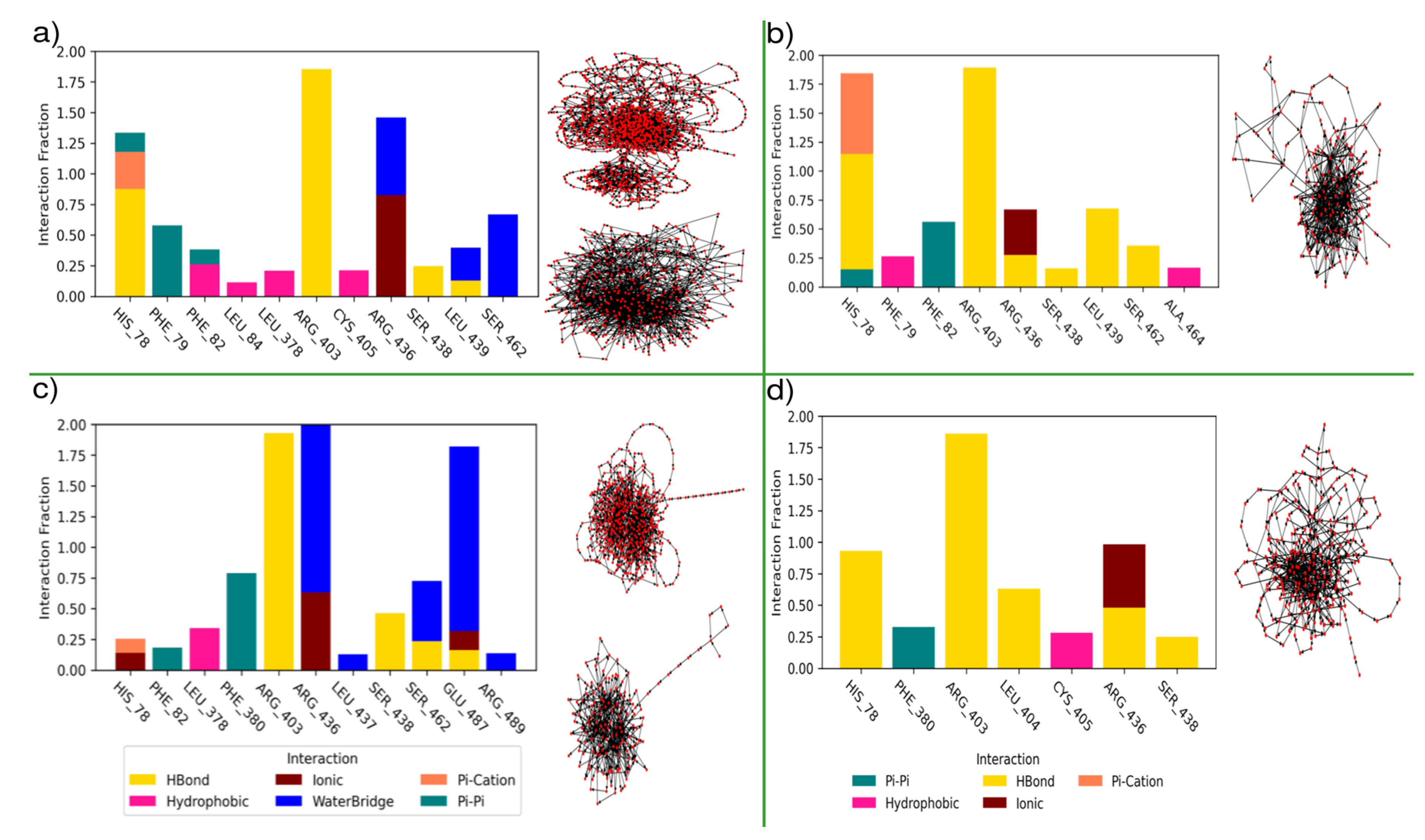

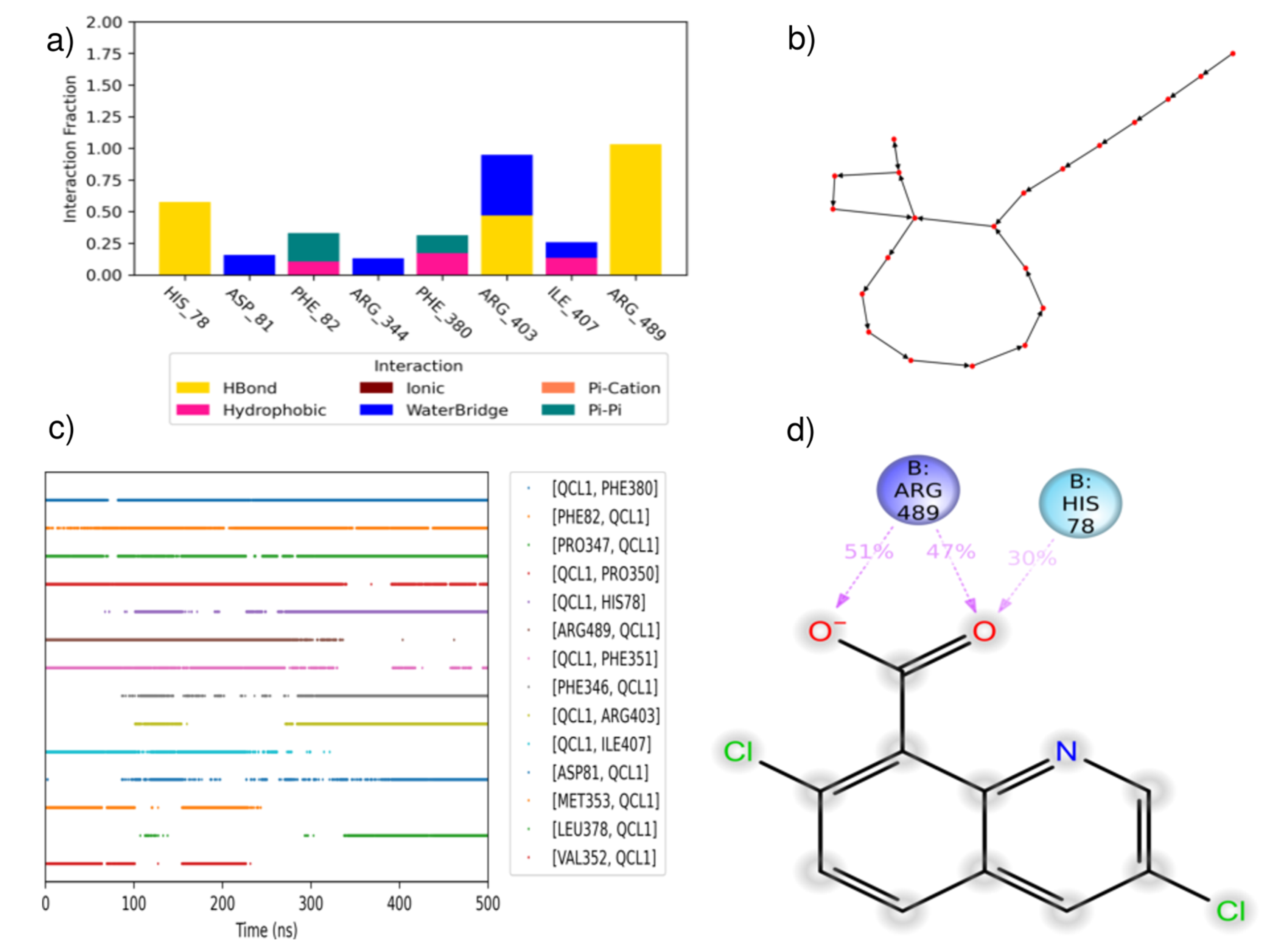

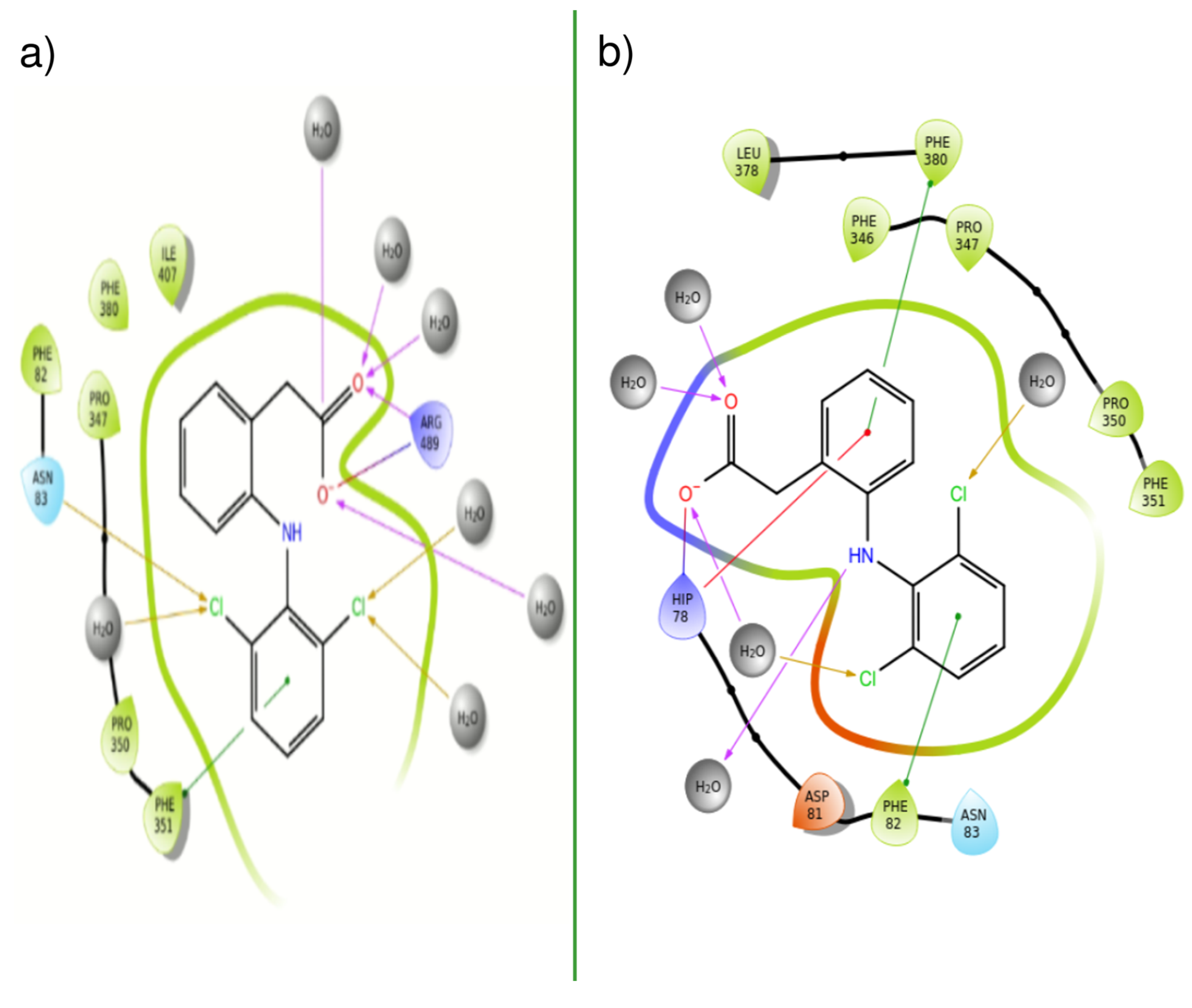

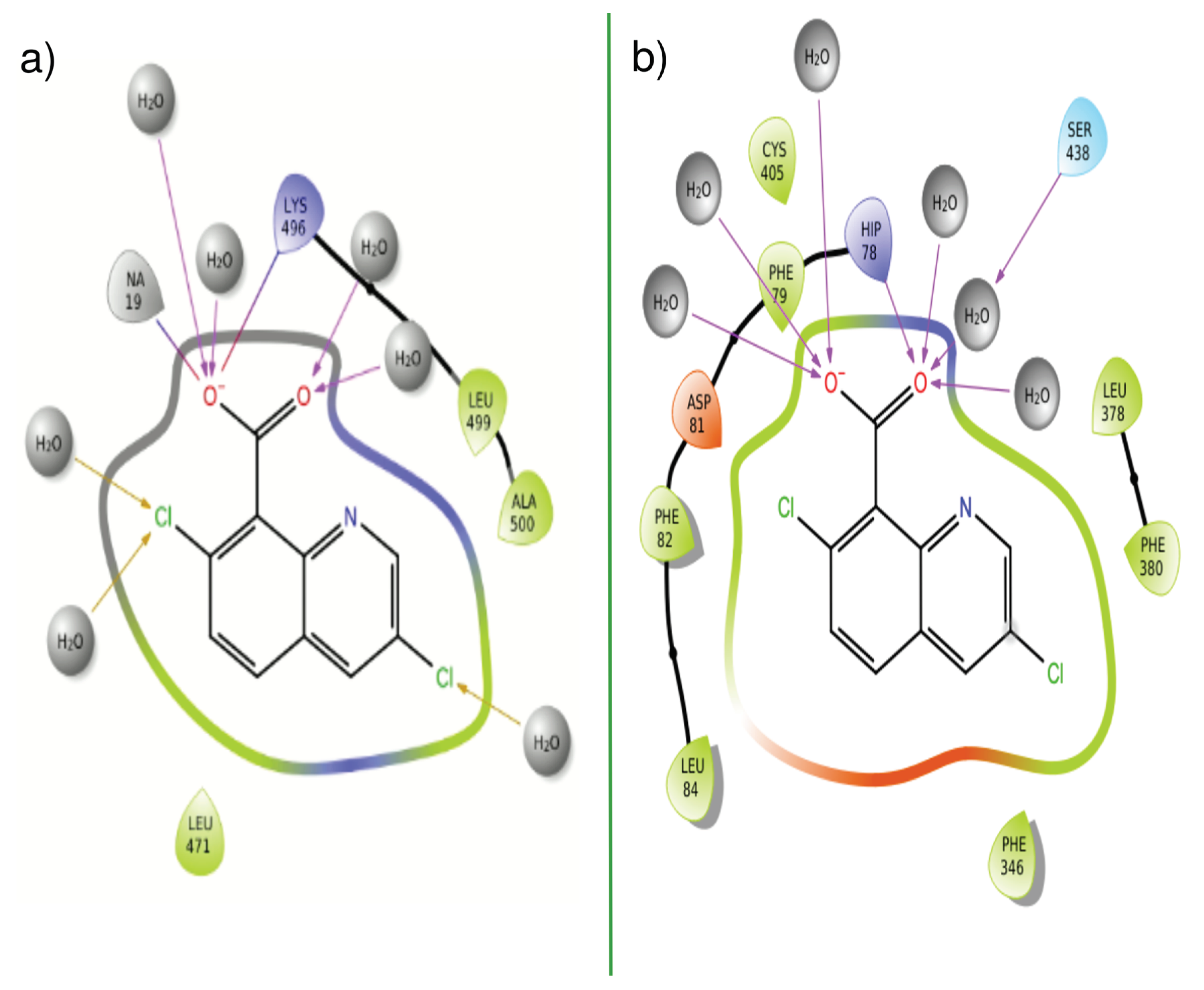

3.3.3. Molecular Dynamics

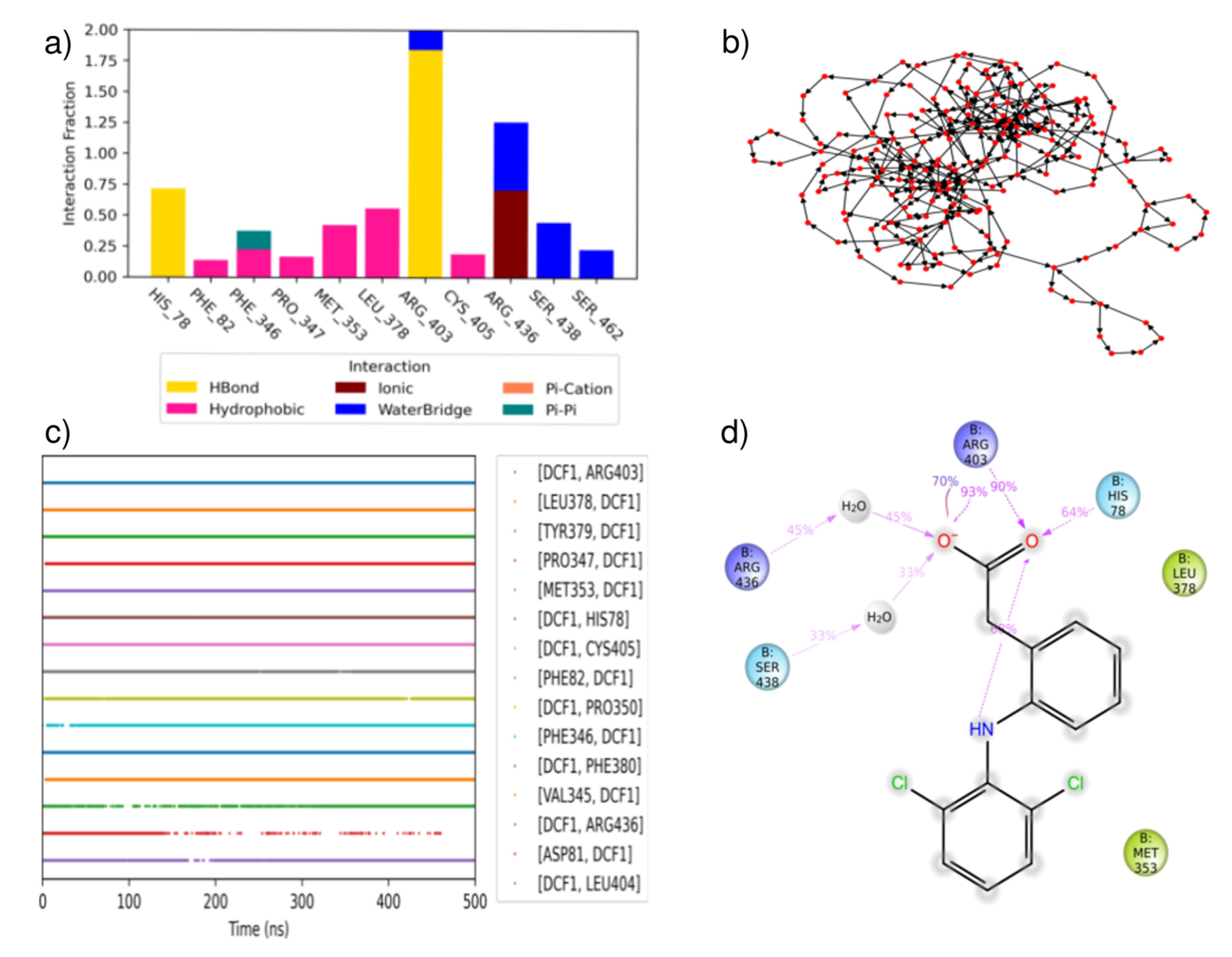

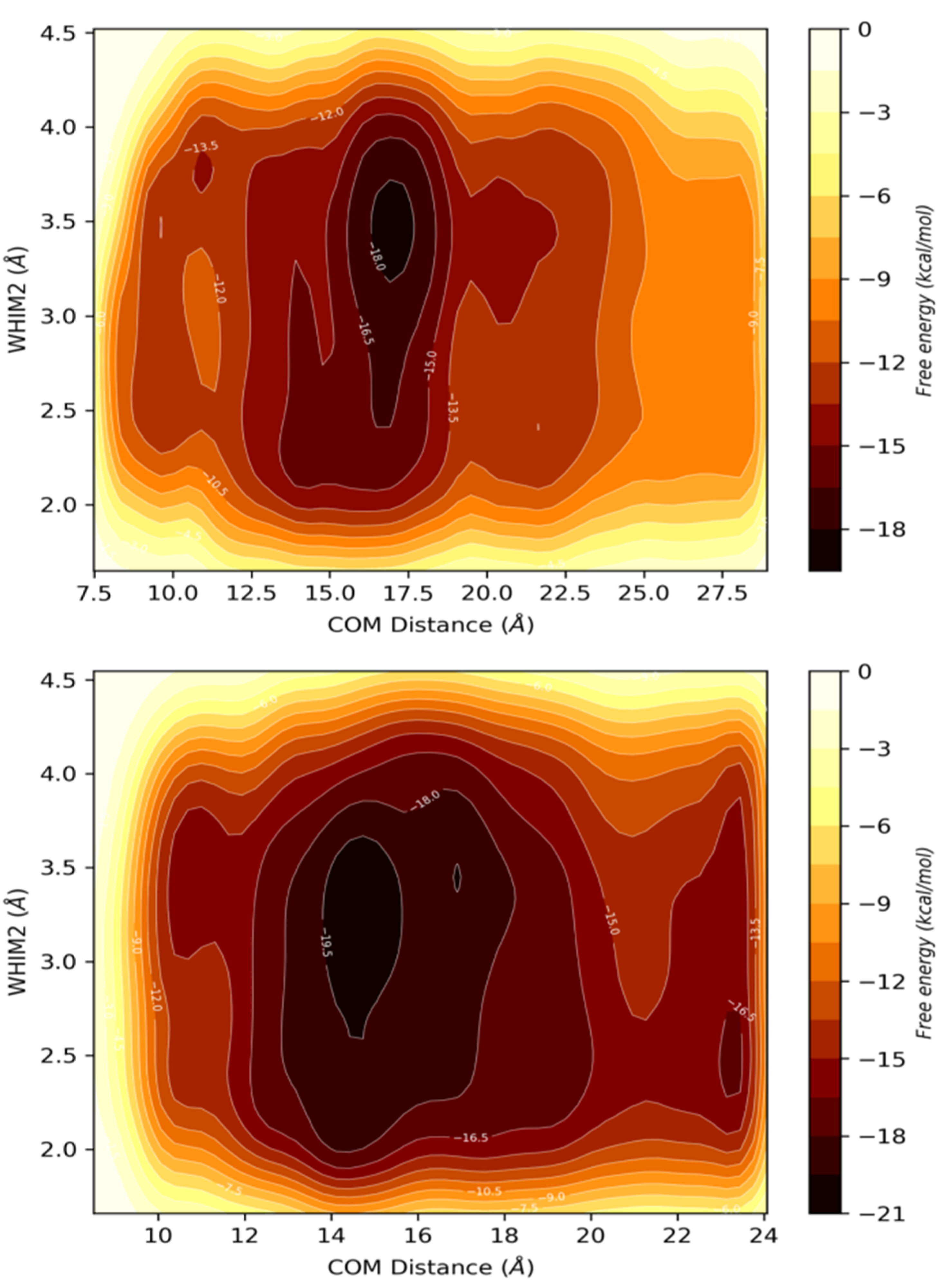

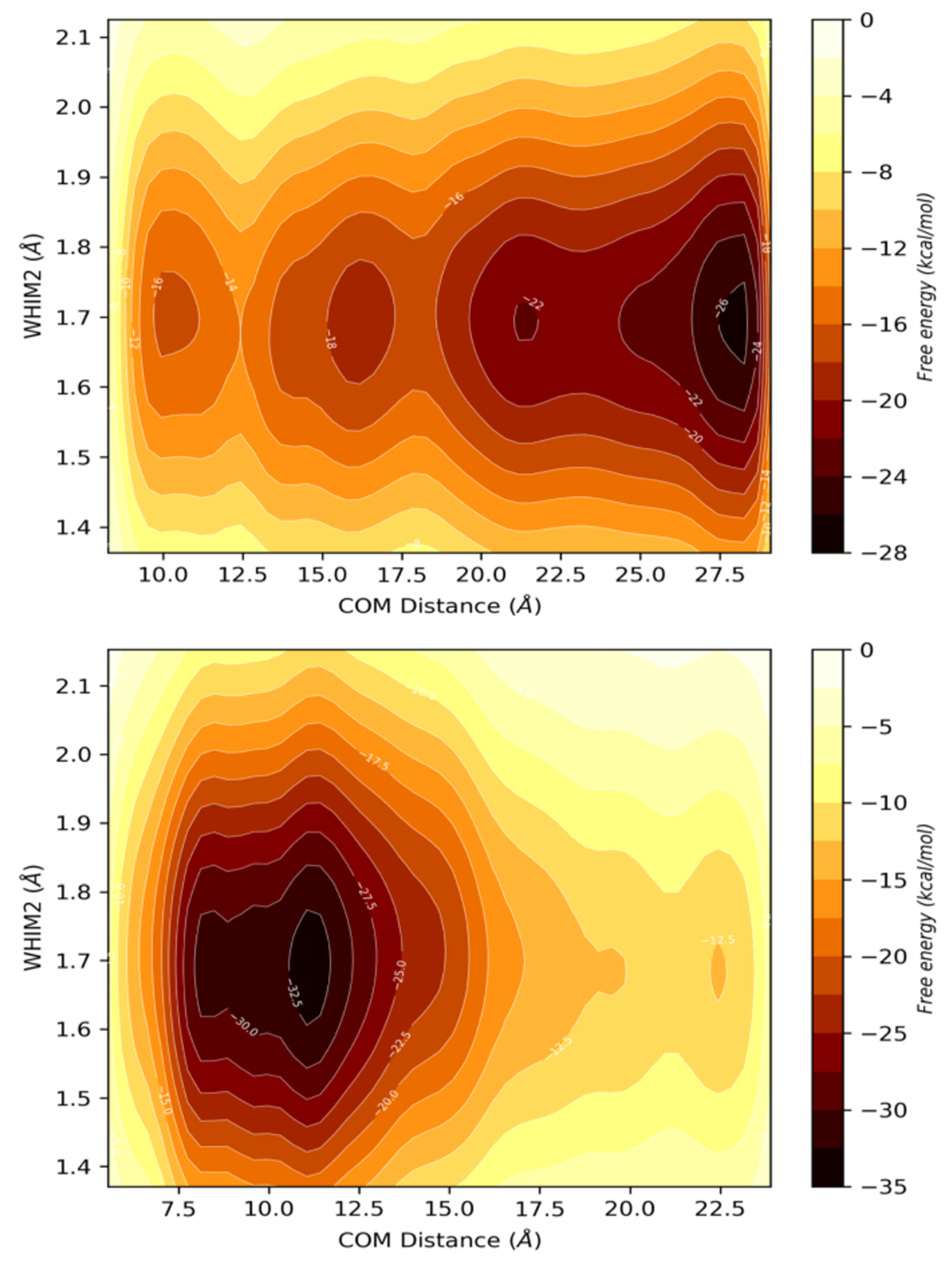

3.3.4. Coarse Metadynamics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, and M. Roser, “Agricultural Production,” Our World in Data, Jan. 2023, Accessed: Mar. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-production.

- “2.1 Food security indicators – latest updates and progress towards ending hunger and ensuring food security.” Accessed: Mar. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/online/sofi-2022/food-security-nutrition-indicators.html.

- P. Carvalho-Moore, G. Rangani, J. Heiser, D. Findley, S.J. Bowe, and N. Roma-Burgos, “PPO2 Mutations in Amaranthus palmeri: Implications on Cross-Resistance,” Agriculture, vol. 11, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Shaner, “Lessons Learned From the History of Herbicide Resistance,” Weed Science, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 427–431, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Heap, The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. Accessed: Feb. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.weedscience.com/Home.aspx.

- P. K. Gupta, “Chapter 37 - Herbicides and Fungicides,” in Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology (Second Edition), R.C. Gupta, Ed., Academic Press, 2017, pp. 657–679. [CrossRef]

- D. Panchal, J. D. Panchal, J. Mistry, and D. Amin, “Auxin,” in Practical Handbook on Agricultural Microbiology, N. Amaresan, P. Patel, and D. Amin, Eds., New York, NY: Springer US, 2022, pp. 251–255. [CrossRef]

- W. D. Teale, I.A. W. D. Teale, I.A. Paponov, and K. Palme, “Auxin in action: signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development,” Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 847–859, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. Hayashi et al., “Rational Design of an Auxin Antagonist of the SCFTIR1 Auxin Receptor Complex,” ACS Chem. Biol., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 590–598, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Grossmann, “Mediation of Herbicide Effects by Hormone Interactions,” J Plant Growth Regul, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 109–122, Mar. 2003. [CrossRef]

- N. Dharmasiri, “Auxin signaling and regulated protein degradation,” Trends in Plant Science, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 302–308, Jun. 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang and M. Estelle, “Diversity and specificity: auxin perception and signaling through the TIR1/AFB pathway,” Current Opinion in Plant Biology, vol. 21, pp. 51–58, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Todd et al., “Synthetic auxin herbicides: finding the lock and key to weed resistance,” Plant Science, vol. 300, p. 110631, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Ma, P. Q. Ma, P. Grones, and S. Robert, “Auxin signaling: a big question to be addressed by small molecules,” Journal of Experimental Botany, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 313–328, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Chéron, N. N. Chéron, N. Jasty, and E. I. Shakhnovich, “OpenGrowth: An Automated and Rational Algorithm for Finding New Protein Ligands,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 4171–4188, 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Imrie, A.R. F. Imrie, A.R. Bradley, and C. M. Deane, “Generating property-matched decoy molecules using deep learning,” Bioinformatics, vol. 37, no. 15, pp. 2134–2141, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Moriwaki, Y.-S. H. Moriwaki, Y.-S. Tian, N. Kawashita, and T. Takagi, “Mordred: a molecular descriptor calculator,” Journal of Cheminformatics, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 4, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Kursa and W. R. Rudnicki, “Feature selection with the Boruta package,” Journal of statistical software, vol. 36, pp. 1–13, 2010.

- T. Sander, J. T. Sander, J. Freyss, M. von Korff, and C. Rufener, “DataWarrior: An Open-Source Program For Chemistry Aware Data Visualization And Analysis,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 460–473, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Pedregosa et al., “Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python,” Journal of machine learning research, vol. 12, no. Oct, pp. 2825–2830, 2011.

- T. Chen and C. Guestrin, “XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, in KDD ’16. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2016, pp. 785–794. [CrossRef]

- F. D. Prieto-Martínez, E. F. D. Prieto-Martínez, E. Fernández-de Gortari, J.L. Medina-Franco, and L. M. Espinoza-Fonseca, “An in silico pipeline for the discovery of multitarget ligands: A case study for epi-polypharmacology based on DNMT1/HDAC2 inhibition,” Artif Intell Life Sci, vol. 1, p. 100008, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Landrum et al., “rdkit/rdkit: 2024_03_1 (Q1 2024) Release Beta.” Zenodo, Mar. 19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Feng, Y. Zhang, P.H. Bos, J.M. Chambers, M.M. Dupont, and B. R. Stockwell, “K-RasG12D Has a Potential Allosteric Small Molecule Binding Site,” Biochemistry, vol. 58, no. 21, pp. 2542–2554, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghanakota and H. A. Carlson, “Driving Structure-Based Drug Discovery through Cosolvent Molecular Dynamics: Miniperspective,” J. Med. Chem., vol. 59, no. 23, pp. 10383–10399, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Barrera-Téllez, F.D. Prieto-Martínez, A. Hernández-Campos, K. Martínez-Mayorga, and R. Castillo-Bocanegra, “In Silico Exploration of the Trypanothione Reductase (TryR) of L. mexicana,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 22, Art. no. 22, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Ladbury, “Just add water! The effect of water on the specificity of protein-ligand binding sites and its potential application to drug design,” Chemistry & Biology, vol. 3, no. 12, pp. 973–980, 1996. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Shadrick et al., “Exploiting a water network to achieve enthalpy-driven, bromodomain-selective BET inhibitors,” Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 25–36, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ge, D.C. Wych, M.L. Samways, M.E. Wall, J.W. Essex, and D. L. Mobley, “Enhancing Sampling of Water Rehydration on Ligand Binding: A Comparison of Techniques,” J. Chem. Theory Comput., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1359–1381, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Lukauskis, M.L. Samways, S. Aureli, B.P. Cossins, R.D. Taylor, and F. L. Gervasio, “Open Binding Pose Metadynamics: An Effective Approach for the Ranking of Protein–Ligand Binding Poses,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 62, no. 23, pp. 6209–6216, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Bowers et al., “Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters,” in ACM/IEEE SC 2006 Conference (SC’06), 2006. [CrossRef]

- C. Predescu, M. Bergdorf, and D. E. Shaw, “Midtown splines: An optimal charge assignment for electrostatics calculations,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 153, no. 22, p. 224117, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Aldeghi, G.A. Ross, M.J. Bodkin, J.W. Essex, S. Knapp, and P. C. Biggin, “Large-scale analysis of water stability in bromodomain binding pockets with grand canonical Monte Carlo,” Communications Chemistry, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 19, 2018. [CrossRef]

- De Ruiter and, C. Oostenbrink, “Free energy calculations of protein-ligand interactions,” Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 547–552, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Samways, H.E. Bruce Macdonald, and J. W. Essex, “grand: A Python Module for Grand Canonical Water Sampling in OpenMM,” Journal of chemical information and modeling, vol. 60, no. 10, pp. 4436–4441, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Nittinger, F. Flachsenberg, S. Bietz, G. Lange, R. Klein, and M. Rarey, “Placement of Water Molecules in Protein Structures: From Large-Scale Evaluations to Single-Case Examples,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, vol. 58, no. 8, pp. 1625–1637, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. El Khoury et al., “Comparison of affinity ranking using AutoDock-GPU and MM-GBSA scores for BACE-1 inhibitors in the D3R Grand Challenge 4,” J Comput Aided Mol Des, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 1011–1020, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee et al., “Defining Binding Efficiency and Specificity of Auxins for SCFTIR1/AFB-Aux/IAA Co-receptor Complex Formation,” ACS Chem. Biol., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 673–682, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Cho and K. Kim, “Diclofenac modified the root system architecture of Arabidopsis via interfering with the hormonal activities of auxin,” Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 413, p. 125402, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Korb, S. Bowden, T. Olsson, D. Frenkel, J. Liebeschuetz, and J. Cole, “Ensemble docking revisited,” Journal of Cheminformatics, vol. 2, no. Suppl 1, p. P25, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Korb, T. Stützle, and T. E. Exner, “Empirical scoring functions for advanced Protein-Ligand docking with PLANTS,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 84–96, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- X. Ren et al., “Novel Consensus Docking Strategy to Improve Ligand Pose Prediction,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 58, no. 8, pp. 1662–1668, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Kurkinen, S. Lätti, O.T. Pentikäinen, and P. A. Postila, “Getting Docking into Shape Using Negative Image-Based Rescoring,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 59, no. 8, pp. 3584–3599, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. ten Brink and T. E. Exner, “Influence of Protonation, Tautomeric, and Stereoisomeric States on Protein−Ligand Docking Results,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 1535–1546, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. T. McGibbon et al., “mdtraj/mdtraj: MDTraj 1.9.” Zenodo, Sep. 04, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. W. H. Swenson, S. Roet, and N. Faruk, “dwhswenson/contact_map: contact_map 0.7.0.” Zenodo, Oct. 28, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Bussi and A. Laio, “Using metadynamics to explore complex free-energy landscapes,” Nat Rev Phys, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 200–212, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Masetti, A. Cavalli, M. Recanatini, and F. L. Gervasio, “Exploring Complex Protein−Ligand Recognition Mechanisms with Coarse Metadynamics,” J. Phys. Chem. B, vol. 113, no. 14, pp. 4807–4816, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Provasi, “Ligand-Binding Calculations with Metadynamics,” in Biomolecular Simulations: Methods and Protocols, M. Bonomi and C. Camilloni, Eds., New York, NY: Springer, 2019, pp. 233–253. [CrossRef]

- S. Raniolo and V. Limongelli, “Ligand binding free-energy calculations with funnel metadynamics,” Nat Protoc, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 2837–2866, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, A. Ishchenko, W. Zhang, A. Razavi, and D. Langley, “A highly accurate metadynamics-based Dissociation Free Energy method to calculate protein–protein and protein–ligand binding potencies,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 2024, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. V. Uzunova, M. Quareshy, C.I. del Genio, and R. M. Napier, “Tomographic docking suggests the mechanism of auxin receptor TIR1 selectivity,” Open Biology, vol. 6, no. 10, p. 160139, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Leeson, “Molecular inflation, attrition and the rule of five,” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, vol. 101, pp. 22–33, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Hopkins, G.M. Keserü, P.D. Leeson, D.C. Rees, and C. H. Reynolds, “The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 105–121, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Maggiora, “On Outliers and Activity CliffsWhy QSAR Often Disappoints,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 1535–1535, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. Stumpfe, H. Hu, and J. Bajorath, “Evolving Concept of Activity Cliffs,” ACS Omega, vol. 4, no. 11, pp. 14360–14368, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Stumpfe, H. Hu, and J. Bajorath, “Advances in exploring activity cliffs,” J Comput Aided Mol Des, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 929–942, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Lipinski, F. Lombardo, B.W. Dominy, and P. J. Feeney, “Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings1,” Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 3–26, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Shultz, “Two Decades under the Influence of the Rule of Five and the Changing Properties of Approved Oral Drugs,” J. Med. Chem., vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 1701–1714, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Giblin, S.J. Hughes, H. Boyd, P. Hansson, and A. Bender, “Prospectively Validated Proteochemometric Models for the Prediction of Small-Molecule Binding to Bromodomain Proteins,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 58, no. 9, pp. 1870–1888, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Skyner, J.L. McDonagh, C.R. Groom, T. van Mourik, and J. B. O. Mitchell, “A review of methods for the calculation of solution free energies and the modelling of systems in solution,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 6174–6191, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Deshpande, M. Kuramochi, and G. Karypis, “Data Mining Algorithms for Virtual Screening of Bioactive Compounds,” in Data Mining in Biomedicine, P.M. Pardalos, V.L. Boginski, and A. Vazacopoulos, Eds., Boston, MA: Springer US, 2007, pp. 59–90. [CrossRef]

- N. Lima, E.A. Philot, G.H.G. Trossini, L.P.B. Scott, V.G. Maltarollo, and K. M. Honorio, “Use of machine learning approaches for novel drug discovery,” Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 225–239, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Patlewicz, J.F. Wambaugh, S.P. Felter, T.W. Simon, and R. A. Becker, “Utilizing Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) with high throughput exposure predictions (HTE) as a risk-based prioritization approach for thousands of chemicals,” Computational Toxicology, vol. 7, pp. 58–67, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Vogel, M.R. Bauer, and F. M. Boeckler, “DEKOIS: Demanding Evaluation Kits for Objective in Silico Screening — A Versatile Tool for Benchmarking Docking Programs and Scoring Functions,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 2650–2665, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Stein et al., “Property-Unmatched Decoys in Docking Benchmarks,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 699–714, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G.-B. Li, L.-L. Yang, W.-J. Wang, L.-L. Li, and S.-Y. Yang, “ID-Score: A New Empirical Scoring Function Based on a Comprehensive Set of Descriptors Related to Protein–Ligand Interactions,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 592–600, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Lu, X. Hou, C. Wang, and Y. Zhang, “Incorporating Explicit Water Molecules and Ligand Conformation Stability in Machine-Learning Scoring Functions,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 59, no. 11, pp. 4540–4549, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Mobley and K. A. Dill, “Binding of Small-Molecule Ligands to Proteins: ‘What You See’ Is Not Always ‘What You Get,’” Structure, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 489–498, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. Liu and H. Kokubo, “Exploring the Stability of Ligand Binding Modes to Proteins by Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Cross-docking Study,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, vol. 57, no. 10, pp. 2514–2522, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Brenke et al., “Fragment-based identification of druggable ‘hot spots’ of proteins using Fourier domain correlation techniques,” Bioinformatics, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 621–627, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Ghanakota, H. Van Vlijmen, W. Sherman, and T. Beuming, “Large-Scale Validation of Mixed-Solvent Simulations to Assess Hotspots at Protein–Protein Interaction Interfaces,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 784–793, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Tan et al., “Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase,” Nature, vol. 446, no. 7136, pp. 640–645, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Swinburne and D. J. Wales, “Defining, Calculating, and Converging Observables of a Kinetic Transition Network,” J. Chem. Theory Comput., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 2661–2679, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Mockaitis and M. Estelle, “Auxin receptors and plant development: a new signaling paradigm,” Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, vol. 24, pp. 55–80, 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Ross, G.M. Morris, and P. C. Biggin, “One Size Does Not Fit All: The Limits of Structure-Based Models in Drug Discovery,” J Chem Theory Comput, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 4266–4274, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Anighoro and, J. Bajorath, “Three-Dimensional Similarity in Molecular Docking: Prioritizing Ligand Poses on the Basis of Experimental Binding Modes,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 580–587, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Quareshy, J. Prusinska, J. Li, and R. Napier, “A cheminformatics review of auxins as herbicides,” J Exp Bot, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 265–275, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Epp et al., “The discovery of ArylexTM active and RinskorTM active: Two novel auxin herbicides,” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 362–371, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Prusinska, V. Uzunova, P. Schmitzer, M. Weimer, J. Bell, and R. M. Napier, “The differential binding and biological efficacy of auxin herbicides,” Pest Management Science, vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 1305–1315, 2023. [CrossRef]

| PDBID | 2P1M | 2P1P | 2P1Q | 2P1O | 2P1N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2P1M | (RMSD 0.16 Å) H78 - 0.32 F79 - 0.18 D81 - 0.31 F82 - 0.19 C405 - 0.27 S438 - 0.19 L439 - 0.22 S440 - 0.19 S462 - 0.18 |

(RMSD 0.22 Å) H78 - 0.3 F79 - 0.3 D81 - 0.58 F82 - 0.45 C405 - 0.27 R435 - 0.23 S438 - 0.23 L439 - 0.3 R489 - 0.22 |

(RMSD 0.27 Å) H78 - 0.36 D81 - 0.59 F82 - 0.52 C405 - 0.29 L439 - 0.87 |

(RMSD 0.33 Å) H78 - 0.41 F79 - 0.38 D81 - 0.55 F82 - 0.35 C405 - 0.54 L439 - 0.85 V463 - 0.49 A464 - 0.58 R489 - 0.33 |

|

| 2P1P | (RMSD 0.16 Å) F79 - 0.18 D81 - 0.28 F82 - 0.52 L439 - 0.2 A464 - 0.2 R484 - 0.22 |

(RMSD 0.22 Å) D81 - 0.29 F82 - 0.6 A464 - 0.22 |

(RMSD 0.26 Å) F79 - 0.26 D81 - 0.29 F82 - 0.45 C405 - 0.37 R435 - 0.27 L439 - 0.66 V463 - 0.37 A464 - 0.54 |

||

| 2P1Q | (RMSD 0.14 Å) F49 - 0.15 L439 - 0.62 S440 - 0.16 |

(RMSD 0.22 Å) H78 - 0.28 C405 - 0.29 R435 - 0.35 L439 - 0.62 V463 - 0.42 A464 - 0.4 |

|||

| 2P1O | (RMSD 0.19 Å) H78 - 0.3 F82 - 0.22 C405 - 0.31 R435 - 0.28 V463 - 0.43 A464 - 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).