Submitted:

30 March 2024

Posted:

01 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

Inclusion Criteria

- The review included randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, in vitro studies, and observational studies.

- Studies comparing at least two groups.

- In vitro studies investigating the effect of tooth bleaching agents on the demineralization of enamel analyzed with a confocal laser scanning microscope and/or measured with enamel surface roughness and studies measuring the concentration of cariogenic and periodontal microflora in the surrounding tissues, as well as by the presence of initial or advanced forms of caries.

- Studies assess the effect of bleaching on bacterial adherence to enamel.

- Studies are examining the aesthetic effect of bleaching on white or brown spots of enamel and the mechanical effects of bleaching on early caries lesions.

- Studies investigating any effect of bleaching agents on the prevalence of caries (primary or secondary).

Exclusion Criteria

- Animal studies, case reports, and case series.

- Studies without at least one control and one test group, studies without a comprehensive protocol,

- Studies with ineligible results for this review.

- Lack of access to the full text of a study after attempting to contact the author also resulted in study exclusion.

Data Extraction

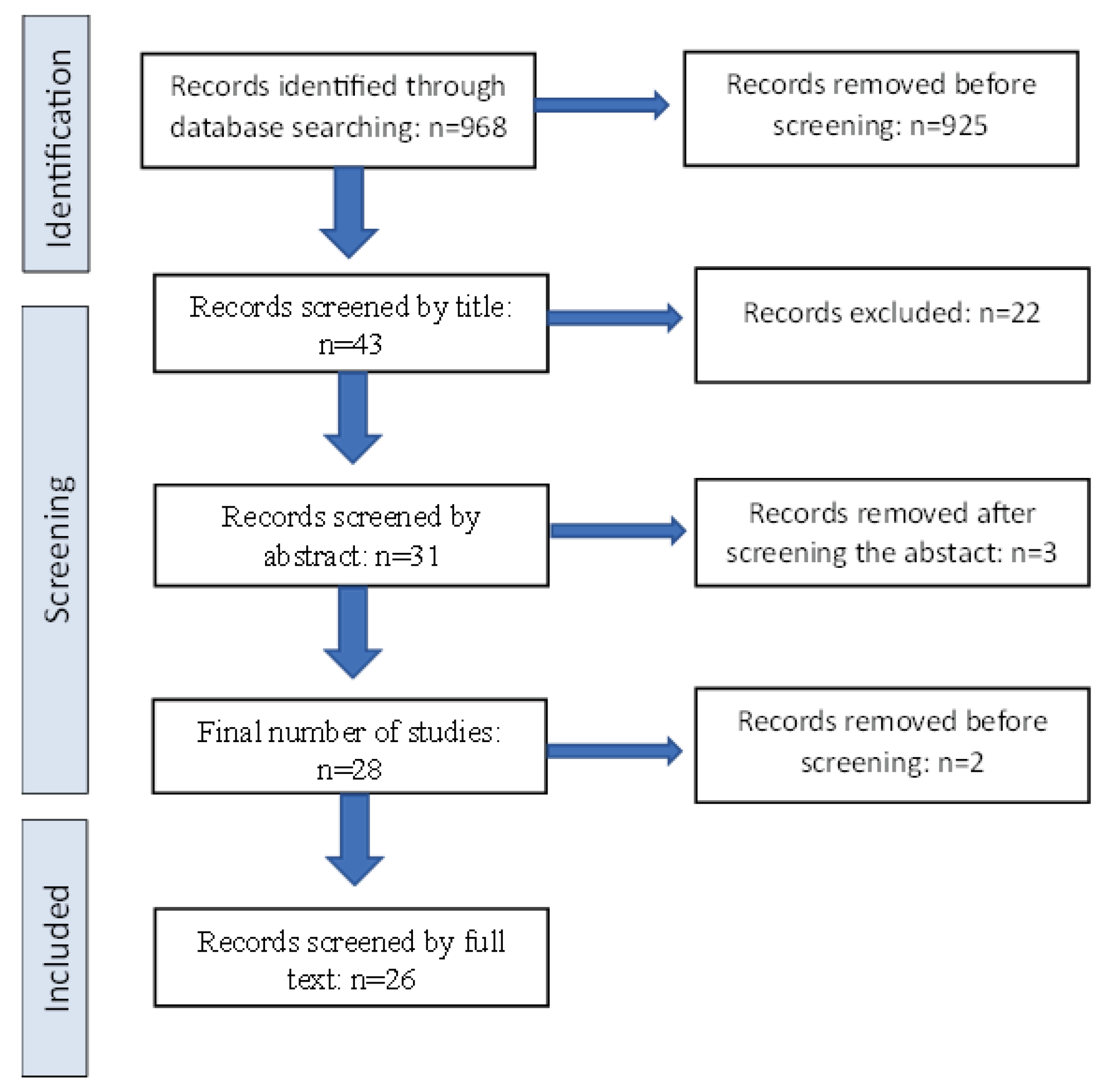

Screening and Eligibility Check

Risk of Bias Assessment (RoB)

3. Results

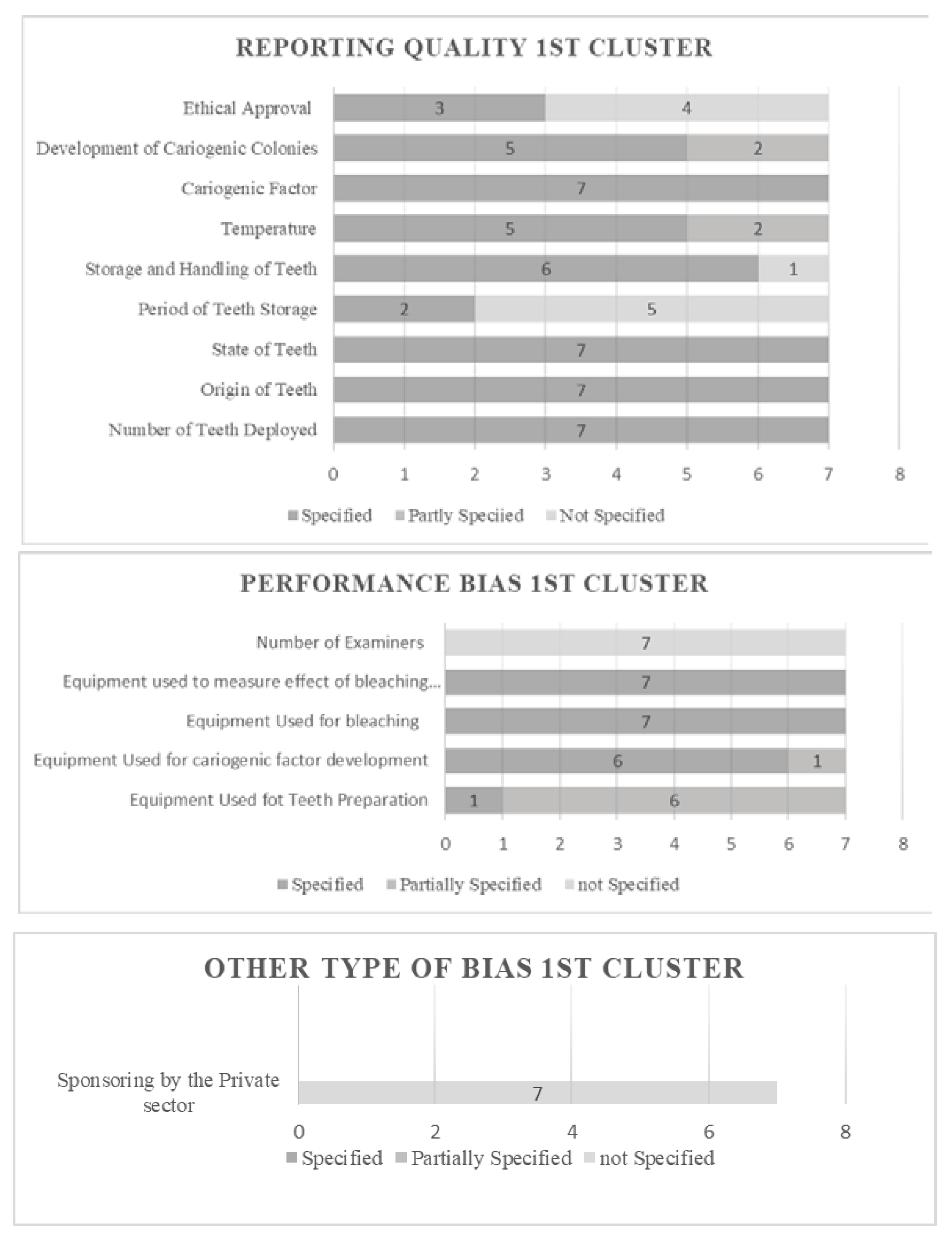

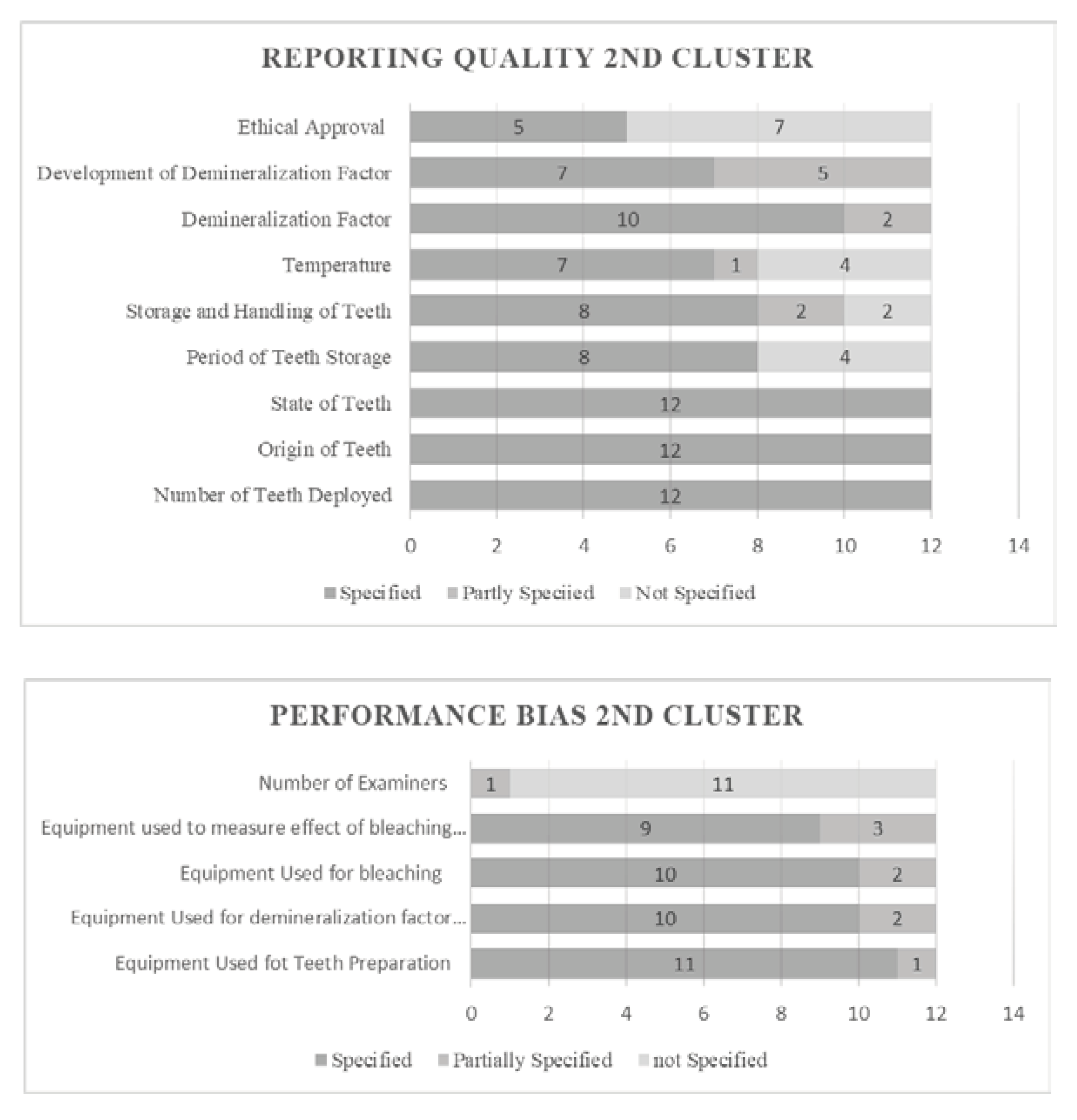

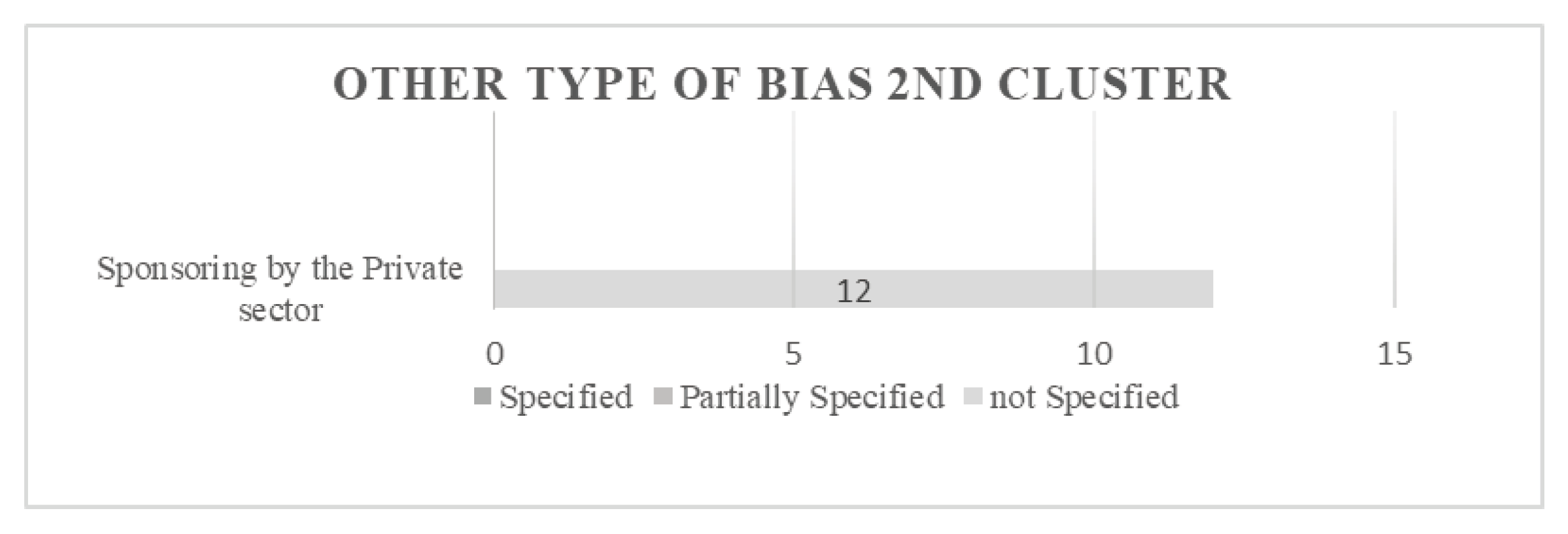

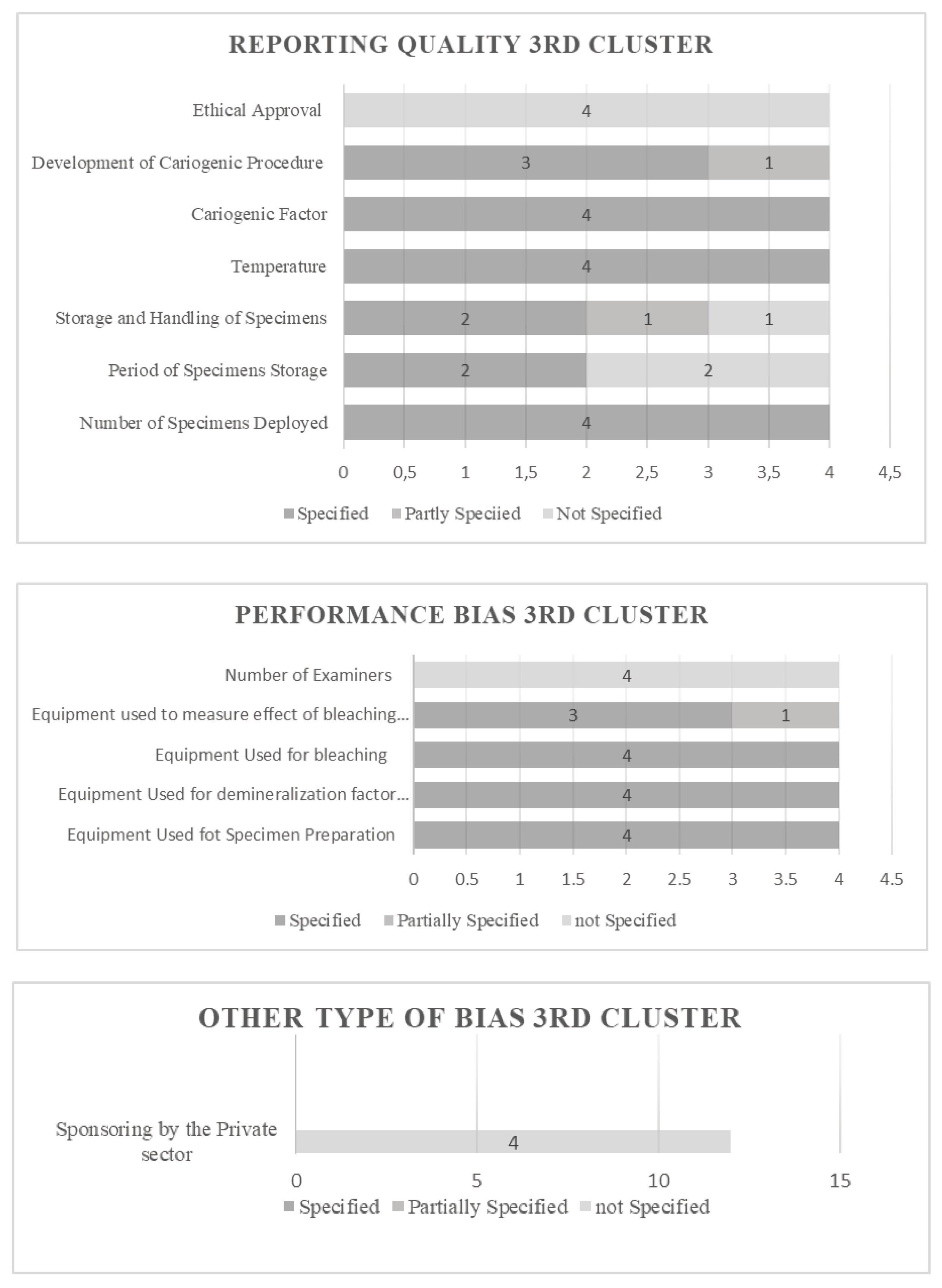

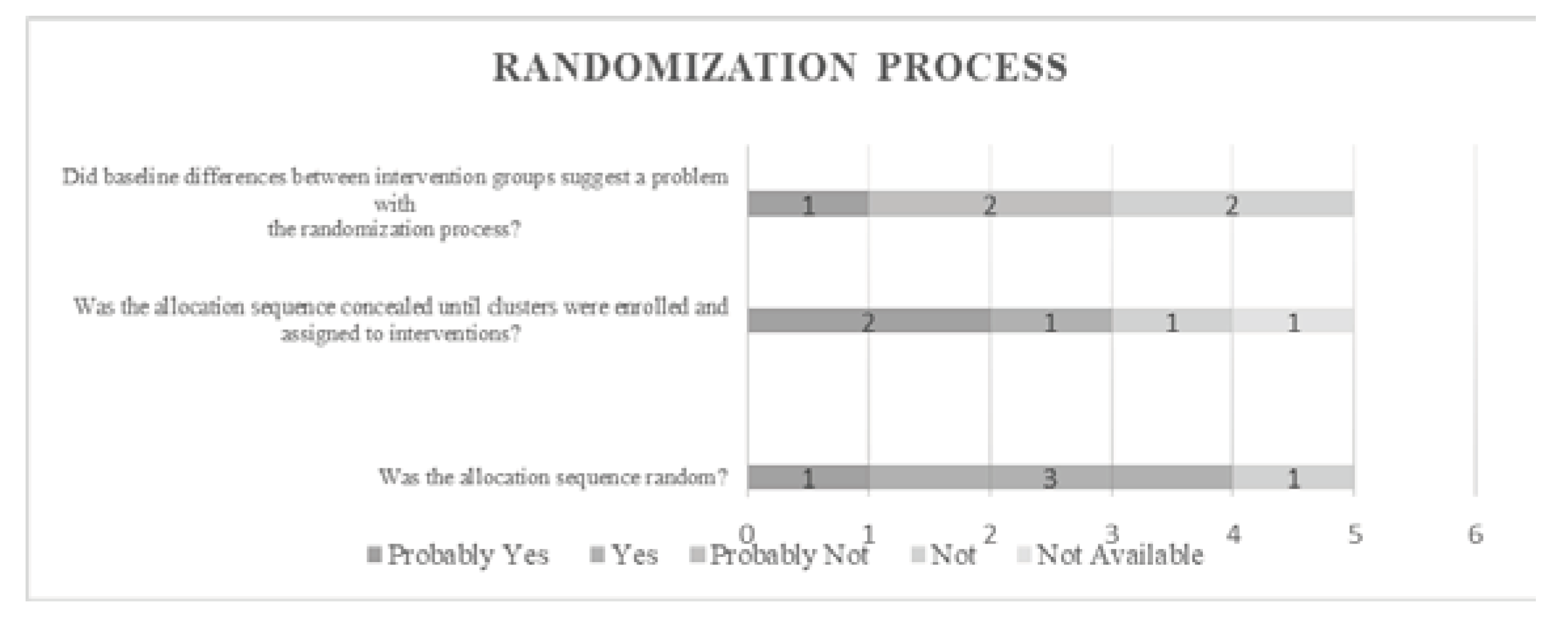

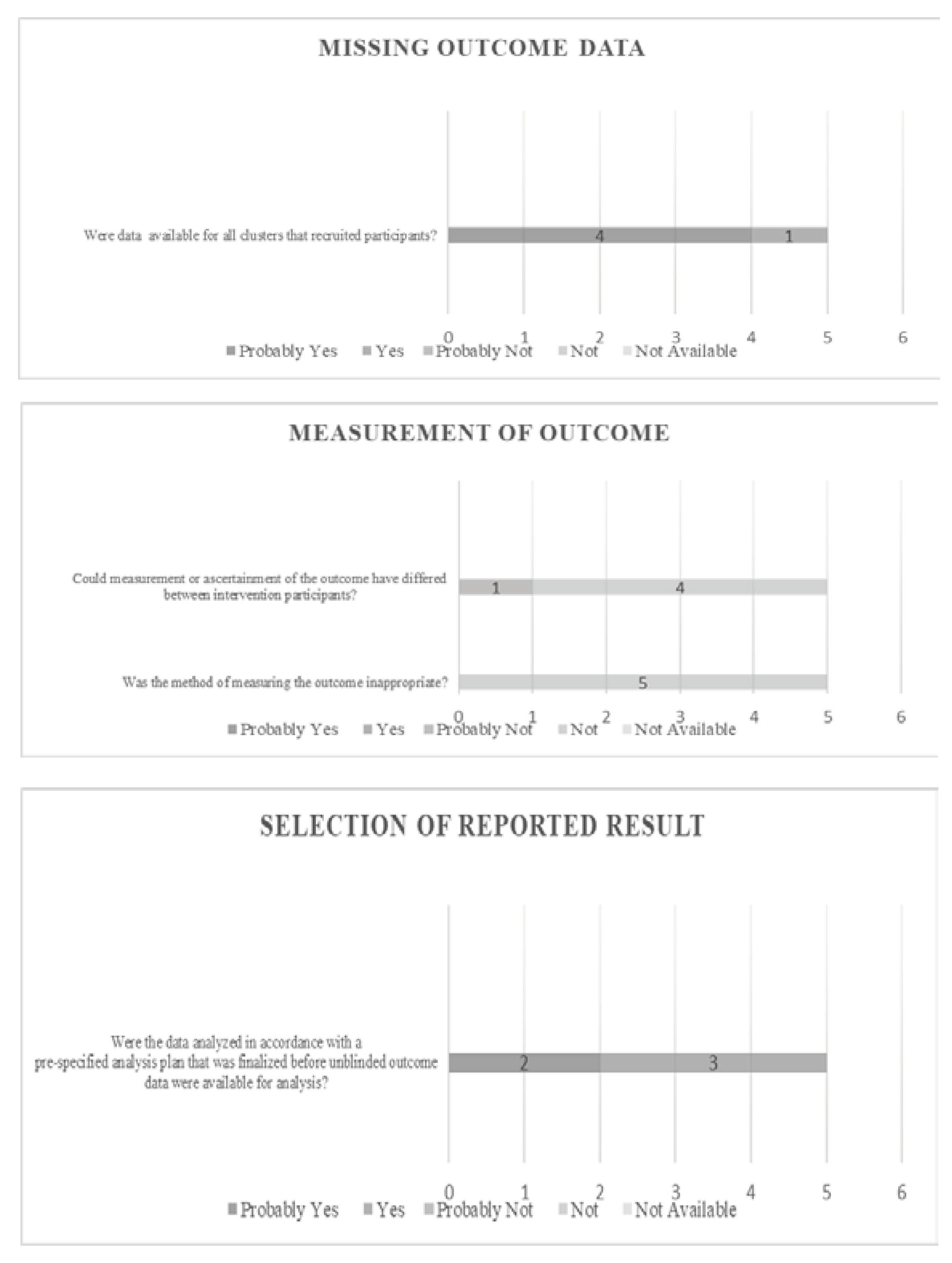

3.1. Results of Risk of Bias Assessment

3.2. Metanalysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kothari, S. , Gray, A.R., Lyons, K., Tan, X.W., Brunton, P.A. Vital bleaching and oral-health-related quality of life in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2019, 84, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zarea, B.K. Satisfaction with appearance and the desired treatment to improve aesthetics. Int J Dent 2013, 2013, ID912368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, E., Bersezio, C., Bottner, J., Avalos, F., Godoy, I., Inda, D., Vildósola, P., Saad, J., Oliveira, O.B. Jr, Martín, J. Longevity, esthetic perception, and psychosocial impact of teeth bleaching by low (6%) hydrogen peroxide concentration for in-office treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Oper Dent 2017, 42, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geus, J.L., de Lara, M.B., Hanzen, T.A, Fernández E, Loguercio, A.D., Kossatz, S., Reis, A. One-year follow-up of at-home bleaching in smokers before and after dental prophylaxis. J Dent 2015, 43, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, G., Sepúlveda, D., Elphick, K., Contente, M., Estay, J., Bahamondes, V., Fernandez, E., Oliveira, O.B., Martin, J. Effects of light activation, agent concentration, and tooth thickness on dental sensitivity after bleaching. Oper Dent 2013, 38, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, L.Y., Kose, C., Loguercio, A.D., Reis, A. Assessing the effect of a desensitizing agent used before in-office tooth bleaching. J Am Dent Assoc 2009, 140, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kina, J.F., Huck, C., Riehl, H., Martinez, T.C., Sacono, N.T., Ribeiro, A.P., Costa, C.A. Response of human pulps after professionally applied vital tooth bleaching. Int Endod J 2010, 43, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, D.G., Basso, F.G., Hebling, J., de Souza, Costa, C.A. Concentrations of and application protocols for hydrogen peroxide bleaching gels: effects on pulp cell viability and whitening efficacy. J Dent 2014, 42, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, D.G., Basso, F.G., Pontes, E.C., Garcia Lda, F., Hebling, J., de Souza Costa, C.A. Effective tooth-bleaching protocols capable of reducing H2O2 diffusion through enamel and dentine. J Dent 2014, 42, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, E.A., Kossatz, S., Fernandes, D., Loguercio, A.D., Reis, A. Administration of ascorbic acid to prevent bleaching-induced tooth sensitivity: a randomized triple-blind clinical trial. Oper Dent 2014, 39, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, M., Loguercio, A.D., Kossatz, S., Reis, A. Predictive factors on the efficacy and risk /intensity of tooth sensitivity of dental bleaching: a multi regression and logistic analysis. J Dent 2016, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Geus, J.L. , Wambier, L.M., Kossatz, S., Loguercio, A.D., Reis, A. At-home vs In-office Bleaching: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Oper Dent 2016, 41(4), 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, B.M. , Burey, A., de Paris Matos, T., Loguercio, A.D., Reis, A. In-office dental bleaching with light vs. without light: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2018, 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, B.M. , Matos, T.P., de Castro, A.D.S., Vochikovski, L., Amadori, A.L., Loguercio, A.D., Reis, A., Berger, S.B. In-office bleaching with low/medium vs. high concentrate hydrogen peroxide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2020, 103, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luque-Martinez, I., Reis, A., Schroeder, M., Muñoz, M.A., Loguercio, A.D., Masterson, D., Maia, L.C. Comparison of efficacy of tray-delivered carbamide and hydrogen peroxide for at-home bleaching: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2016, 20, 1419–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanolla, J., Marques, A., da Costa, D.C., de Souza, A.S,. Coutinho, M. Influence of tooth bleaching on dental enamel microhardness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Dent J 2017, 62, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höchli, D., Hersberger-Zurfluh, M., Papageorgiou, S.N., Eliades, T. Interventions for orthodontically induced white spot lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 2017, 39, 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bourouni, S., Dritsas, K., Kloukos, D., Wierichs, R.J. Efficacy of resin infiltration to mask post-orthodontic or non-post-orthodontic white spot lesions or fluorosis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2021, 25, 4711–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M., Momoi, Y., Fujitani, M., Fukushima, M., Imazato, S., Kitasako, Y., Kubo, S., Nakashima, S., Nikaido, T., Shimizu, A., Sugai, K., Takahashi, R., Unemori, M., Yamaki, C. Evidence-based consensus for treating incipient enamel caries in adults by non-invasive methods: recommendations by GRADE guideline. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2020, 56, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attin, T. , Schmidlin, P.R., Wegehaupt, F., Wiegand, A. Influence of study design on the impact of bleaching agents on dental enamel microhardness. A Review. Dental Materials 2009, 25(2), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, B.C., Borges, J.S., de Melo, C.D., Pinheiro, I.V., Santos, A.J., Braz, R., Montes, M.A. Efficacy of a nivel at-home bleaching technique with carbamide peroxides modified by CPP-ACP and its effect on the microhardness of bleached enamel. Operative dentistry 2011, 65, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- de Vasconcelos, A.A., Cunha, A.G., Borges, B.C., Vitoriano, Jde O., Alves-Júnior ,C., Machado, C.T., dos Santos, A.J. Enamel properties after tooth bleaching with hydrogen carbamide peroxides in association with a CPP-ACP paste. Acta Odontolgoica Scandinavica 2012, 70, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Sánchez, I., Oteo-Calatayud, J., Serrano, J., Martín, C., Herrera, D. Changes in plaque and gingivitis levels after tooth bleaching: A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg 2019, 17, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4.1 Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C., Savović, J., Page, M.J., Elbers, R.G., Blencowe, N.S., Boutron, I., Cates, C.J., Cheng, H.Y., Corbett, M.S., Eldridge, S.M., Emberson, J.R., Hernán, M.A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D.R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J.J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B.C., Shepperd, S., Shrier, I., Stewart, L.A., Tilling, K., White, I.R., Whiting, P.F., Higgins, J.P.T. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C., Hernán, M.A., Reeves, B.C., Savović, J., Berkman, N.D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D.G., Ansari, M.T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J.R., Chan, A.W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J.J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y.K., Pigott, T.D., Ramsay, C.R., Regidor, D., Rothstein, H.R., Sandhu, L., Santaguida, P.L., Schünemann, H.J., Shea, B., Shrier, I., Tugwell, P., Turner, L., Valentine, J.C., Waddington, H., Waters, E., Wells, G.A., Whiting, P.F., Higgins, J.P. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H., Oxman, A.D., Vist, G.E., Kunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., Schünemann, H.J.; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 26;336(7650), 924–926. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 29, 372:n71. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C., Savović, J., Page, M.J., Elbers, R.G., Blencowe, N.S., Boutron, I., Cates, C.J., Cheng, H.Y., Corbett, M.S., Eldridge, S.M., Emberson, J.R., Hernán, M.A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D.R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J.J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B.C., Shepperd, S., Shrier, I., Stewart, L.A., Tilling, K., White, I.R., Whiting, P.F., Higgins, J.P.T. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 28, 366:l4898. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya, N., Honda, K., Iino, F., Arai, T. Changes in enamel surface roughness and adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to enamel after vital bleaching. J Dent 2003, 31(8), 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Huo, S., Liu, S., Zou, L., Cheng, L., Zhou, X., Li, M. Effects of Cold-Light Bleaching on Enamel Surface and Adhesion of Streptococcus mutans. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 3766641. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X., Yuan, K., Huang, Z., Ma, R. Effects of Bleaching Associated with Er:YAG and Nd:YAG Laser on Enamel Structure and Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Scanning, 2021; 20, 6400605. [Google Scholar]

- Voina, C.; Delean, A.; Muresan, A.; Valeanu, M.; Mazilu Moldovan, A.; Popescu, V.; Petean, I.; Ene, R.; Moldovan, M.; Pandrea, S. Antimicrobial Activity and the Effect of Green Tea Experimental Gels on Teeth Surfaces. Coatings 2020, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittatirut, S., Matangkasombut, O., Thanyasrisung, P. In-office bleaching gel with 35% hydrogen peroxide enhanced biofilm formation of early colonizing streptococci on human enamel. J Dent 2014, 42, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qunaian, T.A. The effect of whitening agents on caries susceptibility of human enamel. Oper Dent 2005, 30(2), 265–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nam, S.H., Ok, S.M., Kim, G.C. Tooth bleaching with low-temperature plasma lowers surface roughness and Streptococcus mutans adhesion. Int Endod J 2018, 51, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y., Son, H.H., Yi, K., Ahn, J.S., Chang, J. Bleaching Effects on Color, Chemical, and Mechanical Properties of White Spot Lesions. Oper Dent 2016, 41, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Angari, S.S., Lippert, F., Platt, J.A., Eckert, G.J., González-Cabezas, C., Li, Y., Hara, A.T. Bleaching of simulated stained-remineralized caries lesions in vitro. Clin Oral Investig 2019, 23, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briso, A., Silva, Ú., Souza, M., Rahal, V., Jardim Júnior, E. G., Cintra, L. A clinical, randomized study on the influence of dental whitening on Streptococcus mutans population. Aust Dent J 2018, 63, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, E.E., Meyer-Lueckel, H., Esteves-Oliveira, M., Wierichs, R.J. Do bleaching gels affect the stability of the masking and caries-arresting effects of caries infiltration-in vitro. Clin Oral Investig 2021, 25, 4011–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.F., Paes Leme, A.F., Cavalli, V., Giannini, M. Effect of 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching on sound and artificial enamel carious lesions. Braz Dent J 2009, 20, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S. B. , Pavan, S., Dos Santos, P. H., Giannini, M., Bedran-Russo, A. K. Effect of bleaching on sound enamel and with early artificial caries lesions using confocal laser microscopy. Brazilian dental journal 2012, 23(2), 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, K., Tanaka, R., Shibata, Y., Miyazaki, T., Hisamitsu, H. In vitro demineralization of tooth enamel subjected to two whitening regimens. J Am Dent Assoc 2013, 144, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. , Okoye, L. O., Lima, P. P., Gakunga, P. T., Amaechi, B. T. Investigation of the esthetic outcomes of white spot lesion treatments. Niger J Clin Pract 2020, 23(9), 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Angari, S. S., Lippert, F., Platt, J. A., Eckert, G. J., González-Cabezas, C., Li, Y., Hara, A. T. Dental bleaching efficacy and impact on demineralization susceptibility of simulated stained-remineralized caries lesions. J Dent 2019, 81, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, E.A. , Alves, F.K., Campos Ede, J., Mathias, P. Susceptibility to carieslike lesions after dental bleaching with different techniques. Quintessence Int 2007, 38(7), e404–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Shahrani, A. A., Levon, J. A., Hara, A. T., Tang, Q., Lippert, F. The ability of dual whitening anti-caries mouthrinses to remove extrinsic staining and enhance caries lesion remineralization - An in vitro study. J Dent 2020, 103S, 100022. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, I.A. , Edgar, W.M., Higham, S.M. The effect of bleaching on enamel susceptibility to acid erosion and demineralisation. Br Dent J, 2005, 12;198(5), 285-90.

- Mor, C. , Steinberg, D., Dogan, H., Rotstein, I. Bacterial adherence to bleached surfaces of composite resin in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998, 86(5), 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, D., Mor, C., Dogan, H., Zacks, B., Rotstein, I. Effect of salivary biofilm on the adherence of oral bacteria to bleached and non-bleached restorative material. Dent Mater 1999, 15, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpraparatana, I., Matangkasombut, O., Thanyasrisung, P., Panich, M. Effect of Vital Tooth Bleaching on Surface Roughness and Streptococcal Biofilm Formation on Direct Tooth-Colored Restorative Materials. Oper Dent 2018, 43, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgan, S., Bolay, S., Alaçam, R. Antibacterial activity of 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching agents. J Endod 1996, 22, 356–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.Y., Pan, J., Wang, L., Zhang, C.F. Effects of hydrogen peroxide-containing bleaching on cariogenic bacteria and plaque accumulation. Chin J Dent Res 2011, 14, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Briso, A. L. , Gonçalves, R. S., Costa, F. B., Gallinari, M.deO., Cintra, L. T., Santos, P. H. Demineralization and hydrogen peroxide penetration in teeth with incipient lesions. Braz Dent J 2015, 26(2), 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkmin, Y.T. , Sartorelli, R., Flório, F.M., Basting, R.T. Comparative study of the effects of two bleaching agents on oral microbiota. Oper Dent 2005, 30(4), 417–423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knösel, M., Attin, R., Becker, K., Attin T. External bleaching effect on the color and luminosity of inactive white-spot lesions after fixed orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod 2007, 77, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz-Montan, M., Ramacciato, J. C., Rodrigues, J. A., Marchi, G. M., Rosalen, P. L., Groppo, F. C. The effect of combined bleaching techniques on oral microbiota. Indian J Dent Res 2009, 20, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In Vitro | 23 |

| Clinical | 5 |

| Total number of studies | 28 |

| Cluster 1 | 7 |

| Cluster 2 | 12 |

| Cluster 3 | 4 |

| Total Number of studies | 23 |

| Study | Aim | Design | Sample size & basic features | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Changes in enamel surface roughness and adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to enamel after vital bleaching” Hosoya et al. 2003 [31] | In vitro study aiming at observing the influence of vital bleaching on changes to the enamel surface and adhesion of S.mutans to tooth enamel | In vitro | 70 fresh human impacted third molars - 50 ml of pre-cultivated S. mutans (109 CFU/ml) |

Teeth displayed increased adhesion of S. mutans colonies. |

| 2. | “Effects of Cold-Light Bleaching on Enamel Surface and Adhesion of Streptococcus mutans” Zhang et al. 2021 [32] |

Investigation of how cold-light bleaching would change enamel roughness and adhesion of S. mutans. |

In vitro | Twenty-four maxillary premolars extracted for orthodontic purpose |

The roughness of enamel surfaces was Increased after bleaching -The adhesion of S. mutans was decreased on bleached enamel in turbidity test - The thickness of biofilms was decreased on bleached enamel - S. mutans were less inclined to adhere on bleached enamel from analysis of CLSM (Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy) |

| 3. | “Effects of Bleaching Associated with Er:YAG and Nd:YAG Laser on Enamel Structure and Bacterial Biofilm Formation” Hou et al. 2021 [33] | To compare the effects of bleaching associated with Er:YAG and Nd:YAG laser on enamel structure and mixed biofilm formation on teeth surfaces | In vitro | Sixty-eight enamel samples were prepared from sound permanent thirdmolars | The enamel surface structure significantly changed after bleaching with or without laser treatment |

| 4. | “Antimicrobial Activity and the Effect of Green Tea Experimental Gels on Teeth Surfaces” Voina et al. 2020 [34] |

To evaluate an experimental green tea extract and an experimental green tea gel for enamel restoring treatment after bleaching. We also tested the antibacterial and antifungal effect of the experimental extract against specific endodontic and cariogenic microorganisms | In vitro | Twenty-eight healthy third molars, extracted for orthodontic purposes | The green tea extract solution exerts an important antibacterial effect on P. anaerobius and S. mutans strains / The natural extract based on Camellia sinensis has antimicrobial activity / The experimental extract has no antifungal action on the C. albicans strain |

| 5. | “In-office bleaching gel with 35% hydrogen peroxide enhanced biofilm formation of early colonizing streptococci on human enamel” Ittatirut et al. 2014 [35] | To compare the effects of 25% and 35% hydrogen peroxide in-office bleaching systems on surface roughness and streptococcal biofilm formation on human enamel |

In vitro | 162 enamel specimens were prepared from sound permanent anterior and premolar teeth | Bleaching with both 25% and 35% H2O2 systems significantly decreased the enamel surface roughness comparing to the control - S. sanguis biofilm formation on enamel bleached with 35% H2O2 was markedly higher - no significant difference in S. mutans |

| 6. | “The Effect of Whitening Agents on Caries Susceptibility of Human Enamel” Al-Qunaian et al. 2005 [36] |

This in vitro study evaluated whether the treatment of human enamel with whitening agents containing different concentrations of carbamide or hydrogen peroxide changes the susceptibility of enamel to caries |

In vitro | 24 sound human incisors were selected – 3 groups were created | Application of bleaching agents does not increase caries susceptibility of human enamel. A bleaching agent-containing fluoride reduced caries susceptibility |

| 7. | “Tooth bleaching with low temperature plasma lowers surface roughness and Streptococcus mutans adhesion” Nam et al. 2017 [37] | To evaluate the structural-morphological changes in enamel surface roughness and Streptococcus mutans adhesion after tooth bleaching using plasma in combination with a low concentration of 15% carbamide peroxide (CP) | In vitro | 60 single-rooted human premolars with intact crowns extracted for orthodontic reasons | The application of plasma did not cause structural and morphological changes in enamel. Combination bleaching methods using plasma and low concentrations of 15% CP are less destructive, especially with respect to tooth surface protection |

| Study | Aim | Design | Sample size & basic features | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Bleaching Effects on Color, Chemical, and Mechanical Properties of White Spot Lesions” Kim et al. 2016 [38] | The purpose of the study was to evaluate the effect of bleaching on teeth with white spot lesions | In vitro | Twenty human upper premolars extracted during dental treatments were used | 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching of enamel with white spot lesions decreased color disparities without deteriorating mineral composition or microhardness. The application of CPP-ACP paste promoted mineral gain in the subsurface body lesion |

| 2. | “Bleaching of simulated stained-remineralized caries lesions in vitro” Angari et al. 2018 [39] | This study aimed to develop laboratory models to create stained-remineralized caries-like lesions (s-RCLs) and to test the efficacy of bleaching on their esthetic treatment | In vitro | Enamel and dentin slabs (4 × 4 × 2 mm) were sectioned from the buccal and lingual area of human molars | The laboratory models developed in this investigation are able to create stained-remineralized caries-like lesions in both enamel and dentin. Non-metallic stains are lighter in color and more responsive to bleaching treatment compared to metallic stains |

| 3. | “Demineralization and Hydrogen Peroxide Penetration in Teeth with Incipient Lesions” Briso et al. 2015 [40] | The aim of this study was to evaluate the demineralization and hydrogen peroxide penetration in teeth with incipient lesions submitted to bleaching treatment | In vitro | One hundred sound permanent bovine incisors obtained from steers aged between 24 and 30 months were selected | Application of bleaching agents in previously demineralized enamel favors HP penetration through the tooth structure and the bleaching treatment can increase the demineralization depth of incipient lesions |

| 4. | “Do bleaching gels affect the stability of the masking and caries-arresting effects of caries infiltration—in vitro” Jansen et al. 2020 [41] | The aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of different bleaching gels on the masking and caries-arresting effects of infiltrated and non-infiltrated stained artificial enamel caries lesions | In vitro | Bovine incisors were extracted from freshly slaughtered cattle (negative BSE test), cleaned, and preserved in 0.08% thymol. The teeth were separated in 400 enamel blocks | Under the pH-cycling conditions chosen, the tested bleaching agents could successfully recover the visual appearance of infiltrated and non-infiltrated stained caries-like enamel lesions. The masking and the caries-arresting effects of infiltrated lesions remained stable after bleaching and pH-cycling |

| 5. | “Effect of 10% Carbamide Peroxide Bleaching on Sound and Artificial Enamel Carious Lesions” Pinto et al. 2009 [42] | This study evaluated the effect of 10% carbamide peroxide (CP) bleaching on Knoop surface microhardness (KHN) and morphology of sound enamel and enamel with early artificial caries lesions (CL) after pH-cycling model (pHcm) | In vitro | 40 blocks with known surface microhardness were selected made of extracted human third molars that had been erupted | Carbamide peroxide bleaching promoted mineral loss of sound enamel. Although, the bleaching procedure did not exacerbate mineral loss of the carious enamel, it should be indicated with caution on enamel with caries activity |

| 6. | “Effect of Bleaching on Sound Enamel and with Early Artificial Caries Lesions Using Confocal Laser Microscopy” Berger et al. 2012 [43] | The aim of this study was to evaluate effect of bleaching agents on sound enamel (SE) and enamel with early artificial caries lesions (CL) using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) | In vitro | Twenty extracted sound bovine incisors stored in 0.1% thymol solution were used within 1 month of extraction - Eighty blocks (4 x 5 x 5 mm) of enamel were formed | The bleaching treatments promoted increased sound enamel demineralization, while the addition of Ca ions or ACP did not prevent/reverse the effects caused by the bleaching treatment in both conditions of the enamel - Early artificial caries induced by pH cycling model were not affected by the bleaching treatment |

| 7. | “In vitro demineralization of tooth enamel subjected to two whitening regimens” Ogura et al. 2013 [44] | To examine the level of in vitro demineralization of human tooth enamel after bleaching by using two common bleaching regimens: home bleaching (HB) and office bleaching (OB) with photoirradiation | In vitro | 30 human premolars without stain or defect that had been extracted for orthodontic indications | OB is preferable to HB on the basis of the surface integrity of treated enamel during in vitro demineralization |

| 8. | “Investigation of the Esthetic Outcomes of White Spot Lesion Treatments” Lee 2022 [45] | To compare the ability of bleaching, resin infiltration and microabrasion to restore the appearance of existing white spot lesions (WSL) | In vitro | Extracted human maxillary incisor teeth – Only teeth with WSLs were selected | Among the three investigated treatment modalities, resin infiltration was able to mask WSLs the most |

| 9. | “Dental bleaching efficacy and impact on demineralization susceptibility of simulated stained-remineralized caries lesions” Al-Angari et al. 2018 [46] | To evaluate the efficacy of different bleaching systems on artificially created stained-remineralized caries lesions; and to assess the susceptibility of the bleached lesions to further demineralization | In vitro | Human enamel slabs embedded in acrylic blocks and polished (n=21 per treatment group) | At-home bleaching (15% CP) leads to greater color improvement of remineralized-stained lesions than in-office bleaching (40% HP) |

| 10. | “Susceptibility to caries like lesions after dental bleaching with different techniques” Alves et al. 2007 [47] | To assess the influence of dental bleaching on the susceptibility of developing carieslike lesions | In vitro | 30 unerupted human third molars | In office dental bleaching 37% CP (halogen light) – 35% HP (LED light) does not influence caries like lesions development /home bleaching 10% and 16% CP with 0.2% sodium fluoride reduces susceptibility |

| 11. | “The ability of dual whitening anti-caries 444 to remove extrinsic staining and enhance caries lesion remineralization – An in vitro study” Al-Shahrani et al. 2020 [48] | To investigate the ability of dual whitening anti-caries mouthrinses to remove extrinsic staining from artificially stained caries lesions and to enhance their remineralization and fluoridation | In vitro | Bovine enamel specimens / Teeth crowns were cut into 4x4 mm2 / A total of 250 specimens were prepared | Artificially stained enamel caries lesions shows reduced susceptibility tofluoride remineralization and whitening effects of commercial whitening and anti-caries mouthrinses |

| 12. | “The effect of bleaching on enamel susceptibility to acid erosion and demineralization “Pretty et al. 2005 [49] | To determine if enamel that had been bleached by carbamide (urea) peroxide gel (CPG) was at increased risk of either acid erosion or demineralisation (early caries) than un-bleached enamel | In vitro | 24 human incisors selected with specified criteria | Tooth bleaching with carbamide (urea) peroxide (using commercially available concentrations) does not increase the susceptibility of enamel to acid erosion or caries |

| Study | Aim | Design | Sample size & basic features | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Bacterial adherence to bleached surfaces of composite resin in vitro” Mor et al. 1998 [50] | To examine the effect of bleaching agents on bacterial adherence to polished surfaces of composite resin restorations | In vitro | 162 samples of Polofil Supra light-curing resin-based composite (Voco, Cuxhaven, Germany) were used | The results of this study indicate that both carbamide peroxide and hydrogen peroxide can change the adherence characteristics of several microorganisms with regard to polished surfaces of composite resin |

| 2. | “Effect of salivary biofilm on the adherence of oral bacteria to bleached and non-bleached restorative material” Steinberg et al. 1999 [51] | The objective of this work was to examine the effect of in vitro salivary biofilm on the adherence of oral bacteria to bleached and non-bleached restorative material | In vitro | 162 samples of Charisma Supra-light-curing resin-based composite | Salivary biofilm on Charisma pre-treated with bleaching agents, altered the adhesion of S. mutans, S. sobrinus and A. viscosus |

| 3. | “Effect of Vital Tooth Bleaching on Surface Roughness and Streptococcal Biofilm Formation on Direct Tooth-Colored Restorative Materials” Wongpraparatana et al. 2017 [52] | To compare the effect of simulated bleaching with a 10% carbamide peroxide (CP) or a 40% hydrogen peroxide (HP) system on surface roughness of resin composite and resin-modified glass ionomer cement (RMGI) and streptococcal biofilm formation on these surfaces |

In vitro | 2 restorative materials were used: a nanofilled resin composite material and an RMGI. 108 specimens of each material in shade A2 were fabricated into disks of 5 mm in diameter and 2mm thick | The bleaching systems used, 10% CP or 40% HP, significantly increased both the surface roughness and the streptococcal biofilm formation on resin composite and resin-modified glass ionomer cement |

| 4. | “Antibacterial Activity of 10% Carbamide Peroxide Bleaching Agents” Gurgan et al. 1996 [53] | To examine the antibacterial activity of three commercial 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching agents (Nite White, Karisma, and Opalescence) on S. mutans, S. mitis, S. sanguis, Lactobacillus casei, and Lactobacillus acidophilus | In vitro | S. mutans (type A, 10919), S. mitis (type A, 4a), S. sanguis (type A, 6b), Lactobacillus casei (type 319), and Lactobacillus acidophilus (type A, 161) | All three bleaching materials demonstrated higher antibacterial effect than the 0.2% chlorhexidine solution |

| Study | Aim | Design | Sample size & basic features | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide – containing Bleaching on Cariogenic Bacteria and Plaque Accumulation” Zheng et al. 2011 [54] | To evaluate the effects of a commercial bleaching agent containing 36% hydrogen peroxide on the clinical plaque index and S. mutans and Lactobacilli counts in dental plaque and saliva | In vivo / clinical | 20 medically fit adult volunteers | The S. mutans counts in plaque and saliva 4 weeks after bleaching were significantly decreased compared to that before bleaching |

| 2. | “A clinical, randomized study on the influence of dental whitening on Streptococcus mutans population” Briso et al. 2017 [55] | To evaluate the influence of at-home whitening treatment on Streptococcus mutans in saliva, buccal mucosa, and subgingival and supragingival plaque | Clinical – in vivo | 30 individuals were selected, meeting the criteria for inclusion | No change was observed when whitening was performed with carbamide peroxide. Similarly, no change was found in the bacterial population in saliva and buccal mucosa during the whitening treatment with any products |

| 3. | “Comparative Study of the Effects of Two Bleaching Agents on Oral Microbiota” Alkmin et al. 2005 [56] | This study evaluated the in vivo effects of bleaching agents containing 10% carbamide peroxide (Platinum/Colgate) or 7.5% hydrogen peroxide (Day White 2Z/Discus Dental) on S. mutans during dental bleaching | In vivo | 30 volunteers who needed dental bleaching | No alterations were found in the s.mutans group count during bleaching treatment with bleaching agents containing 10% carbamide peroxide or 7.5% hydrogen peroxide |

| 4. | “External Bleaching Effect on the Color and Luminosity of Inactive White-Spot Lesions after Fixed Orthodontic Appliances” Knosel et al. 2007 [57] | To evaluate the effect of external bleaching on the color and luminosity of inactive white-spot lesions (WSLs) present after fixed orthodontic appliance treatment | In vivo/ clinical | Ten patients with inactive WSLs after therapy with fixed orthodontic appliances | External bleaching is able to satisfactorily camouflage WSLs visible after therapy with fixed orthodontic appliances |

| 5. | “The effect of combined bleaching techniques on oral Microbiota” Franz-Montan et al. 2009 [58] | To evaluate the antimicrobial activity of 10% and 37% carbamide peroxide during dentalbleaching in 3 different modes | In vivo | 32 volunteers assigned to 4 groups (n = 8). | In conclusion, the carbamide peroxide when used at 37%, 10%, or in combination, did not affect human salivary microorganisms tested |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).