Submitted:

29 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

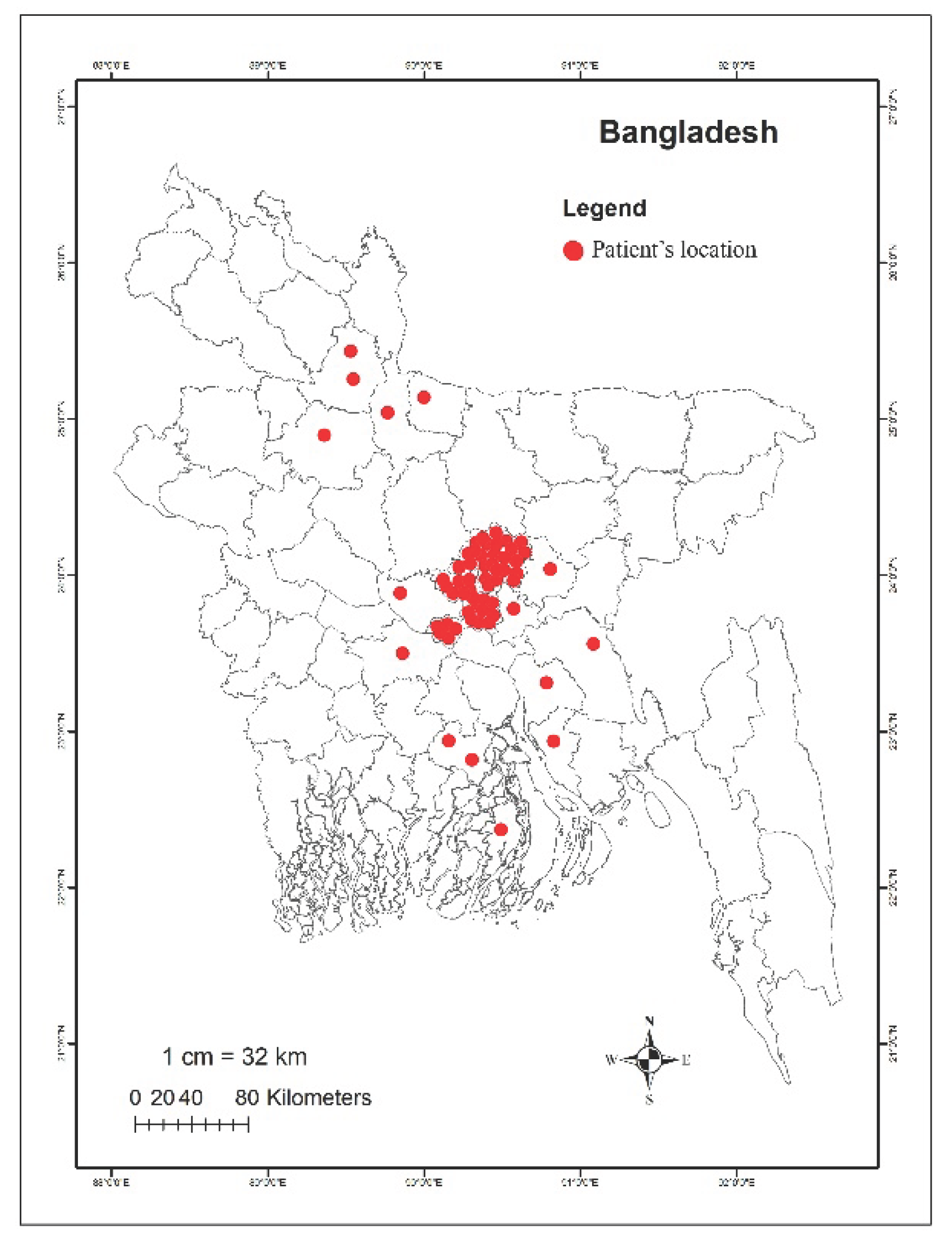

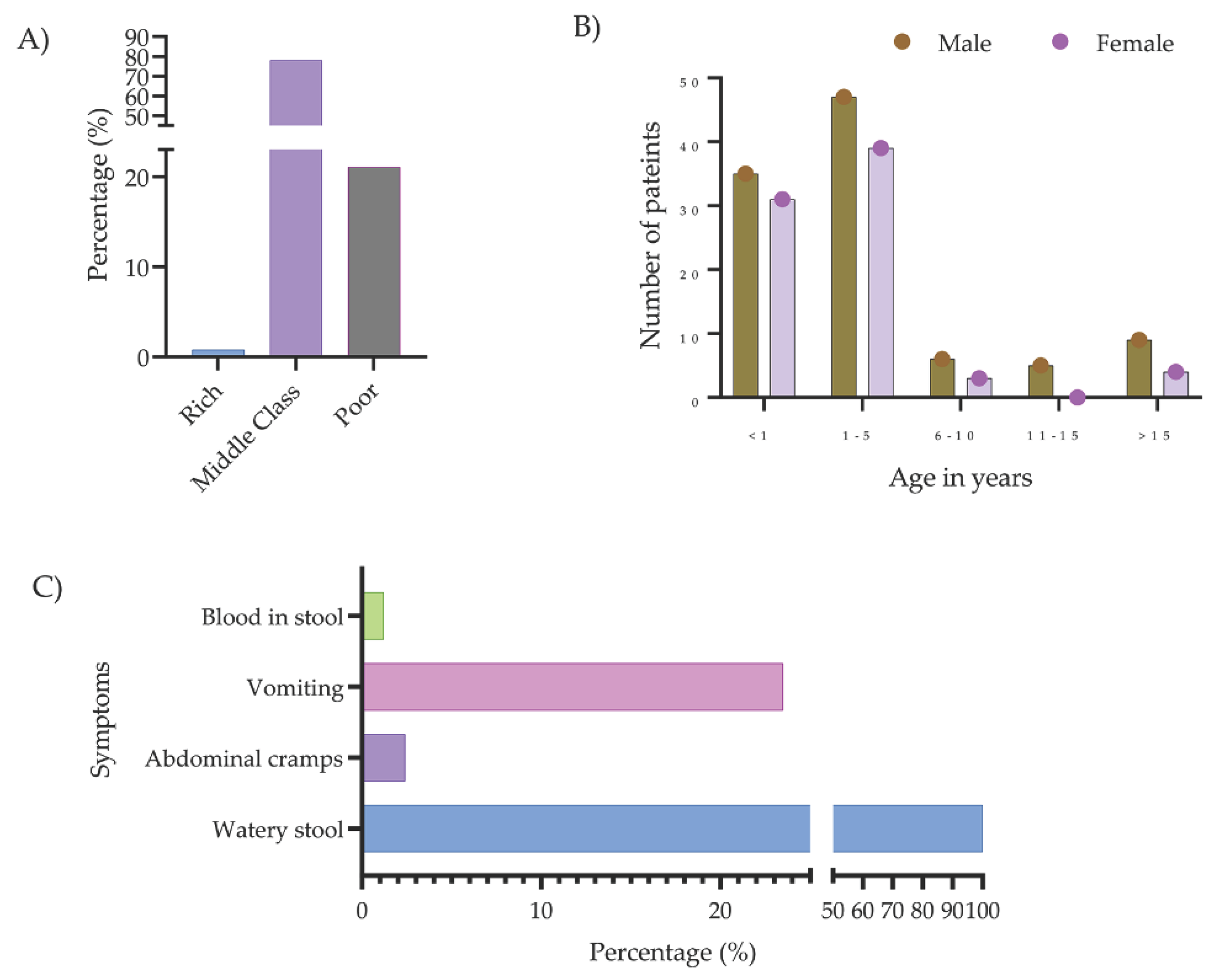

2.1. Study Patients

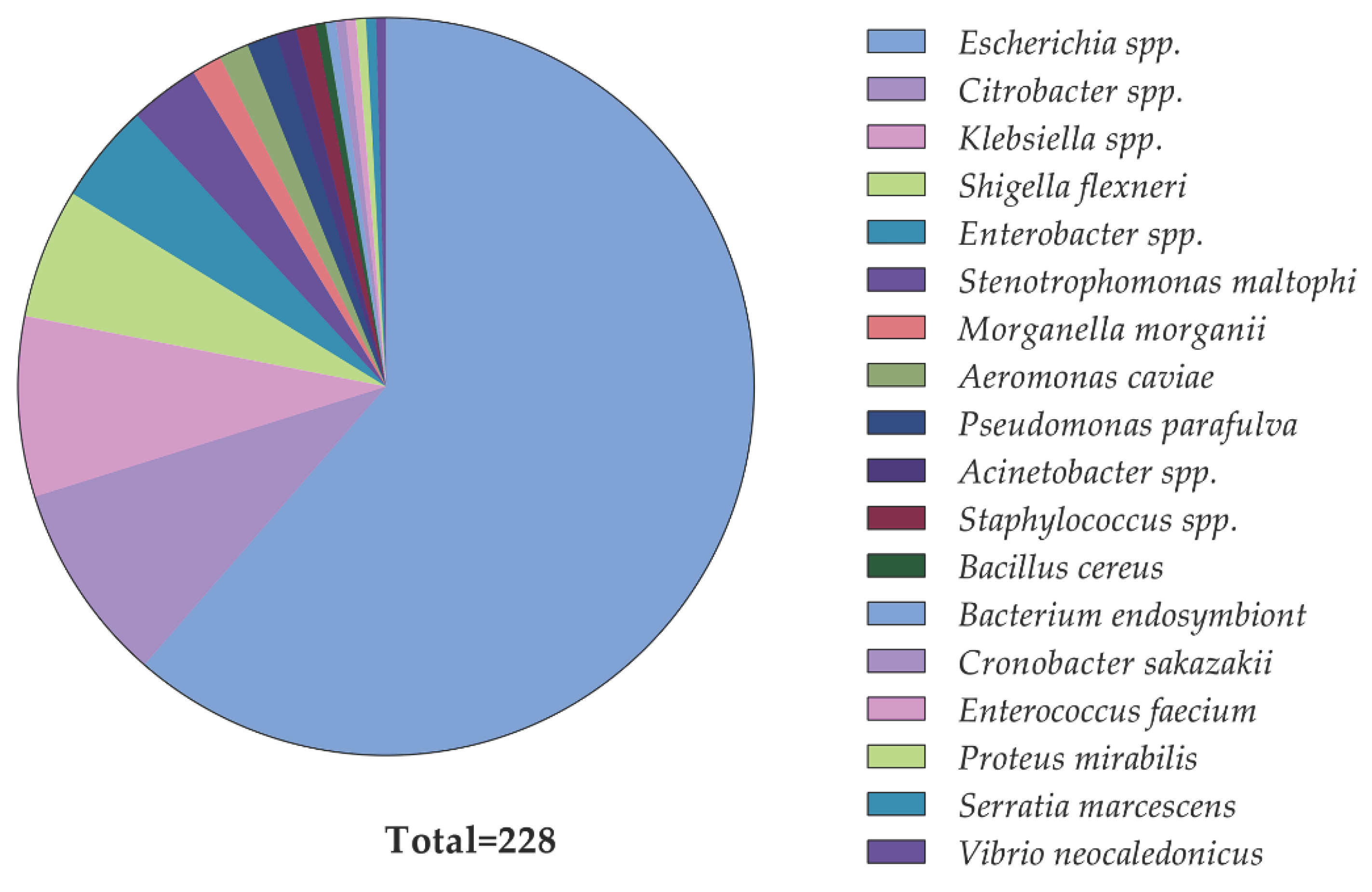

2.2. Identification of Diarrheal Pathogens and Their Phenotypic Colistin Susceptibility

2.3. Prevalence of mcr Genes in Diarrheal Isolates

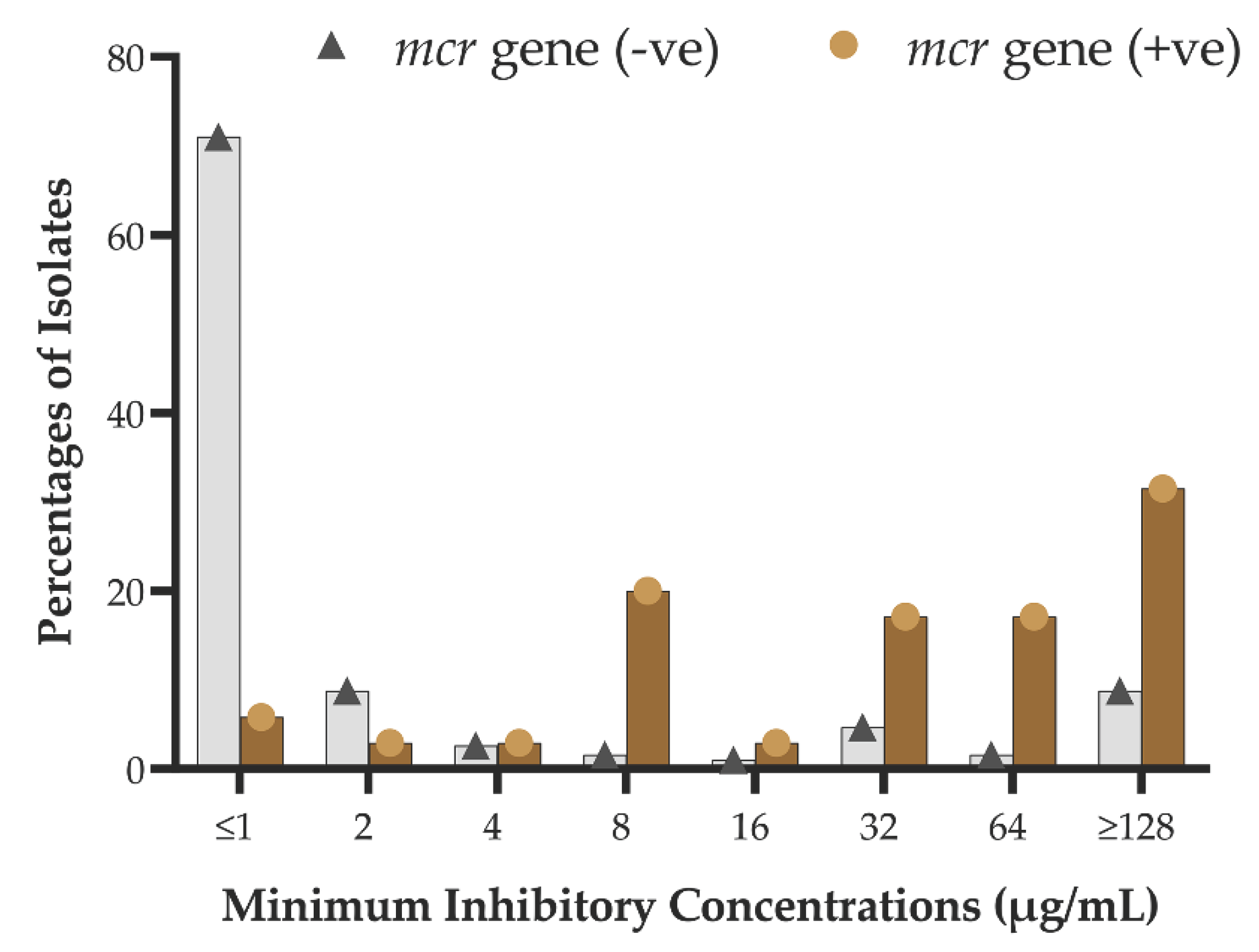

2.4. Phenotypic-Genotypic Association

2.5. Multi-Drug Resistance and mcr-Carriage

2.6. Demographic Factors Associated with the mcr-Carriage

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Sampling

4.2. Isolation and Identification of Bacteria

4.3. Phenotypic Colistin Susceptibility Testing

4.4. Detection of the Colistin Resistance mcr Genes

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.6. Ethics Statements

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. GLOBAL ACTION PLAN ON ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE. 2015. Available online: (accessed on https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/193736/9789241509763_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO European region in 2019: a cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e897–e913. [CrossRef]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, U. The cost of antimicrobial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Group. Pulling Together to Beat Superbugs Knowledge and Implementation Gaps in Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance. 2019. . Available online: (accessed on.

- Gautam, A. Antimicrobial Resistance: The Next Probable Pandemic. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2022, 60, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Jabin, N.; Ahmmed, F.; Sultana, A.; Abdur Rahman, S.; Islam, M.R. Irrational use of antibiotics and factors associated with antibiotic resistance: findings from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. Health science reports 2023, 6, e1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, F.; Imtiaz, M.; ul Haq, I. Emergent crisis of antibiotic resistance: A silent pandemic threat to 21st century. Microbial Pathogenesis 2023, 174, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014, 5, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.T.H.; Yidana, Z.; Smooker, P.M.; Coloe, P.J. Antibiotic use in food animals worldwide, with a focus on Africa: Pluses and minuses. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2020, 20, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Gandra, S. Antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2022, 20, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, K.; Molinier, L.; Hallit, S.; Sartelli, M.; Hardcastle, T.C.; Haque, M.; Lugova, H.; Dhingra, S.; Sharma, P.; Islam, S.; et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries: a scattered picture. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, P.; Athukorala, P.C.; Senanayake, S.; Khan, F. Antimicrobial resistance: the major contribution of poor governance and corruption to this growing problem. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0116746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayukekbong, J.A.; Ntemgwa, M.; Atabe, A.N. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.R.; Ignacio, A.; Rodrigues, V.A.; Groppo, F.C.; Cardoso, A.L.; Avila-Campos, M.J.; Nakano, V. Alterations of Intestinal Microbiome by Antibiotic Therapy in Hospitalized Children. Microb Drug Resist 2017, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouy, E.; Haenni, M.; Le Devendec, L.; Le Roux, A.; Chatre, P.; Madec, J.Y.; Kempf, I. Improvement in routine detection of colistin resistance in E. coli isolated in veterinary diagnostic laboratories. Journal of microbiological methods 2017, 132, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, A.Q.; Verma, M.; Hsu, L.Y.; Legido-Quigley, H. An analysis of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance in Southeast Asia using a governance framework approach. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021, 7, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemsen, A.; Reid, S.; Assefa, Y. A review of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance: strengths and weaknesses. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godman, B.; Egwuenu, A.; Wesangula, E.; Schellack, N.; Kalungia, A.C.; Tiroyakgosi, C.; Kgatlwane, J.; Mwita, J.C.; Patrick, O.; Niba, L.L.; et al. Tackling antimicrobial resistance across sub-Saharan Africa: current challenges and implications for the future. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2022, 21, 1089–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Pulcini, C.; Harbarth, S.; Zeng, M.; Gandra, S.; Mathur, S.; Magrini, N. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO Essential Medicines List for optimal use-be AWaRe. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Gandra, S.; Huttner, B.; Moja, L.; Pulcini, C.; Zeng, M.; Mendelson, M.; Cappello, B.; Cooke, G.; Magrini, N. Encouraging AWaRe-ness and discouraging inappropriate antibiotic use-the new 2019 Essential Medicines List becomes a global antibiotic stewardship tool. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, 1278–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.Y.; Milkowska-Shibata, M.; Tseng, K.K.; Sharland, M.; Gandra, S.; Pulcini, C.; Laxminarayan, R. Assessment of WHO antibiotic consumption and access targets in 76 countries, 2000-15: an analysis of pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharland, M.; Zanichelli, V.; Ombajo, L.A.; Bazira, J.; Cappello, B.; Chitatanga, R.; Chuki, P.; Gandra, S.; Getahun, H.; Harbarth, S.; et al. The WHO essential medicines list AWaRe book: from a list to a quality improvement system. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022, 28, 1533–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, Y.; Lee, B.R.; Versporten, A.; Yang, Y.; Bielicki, J.; Jackson, C.; Newland, J.; Goossens, H.; Magrini, N.; Sharland, M. Use of the WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve classification to define patterns of hospital antibiotic use (AWaRe): an analysis of paediatric survey data from 56 countries. Lancet Glob Health 2019, 7, e861–e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Katukoori, S.; Bollam, N.; George, I.; Yaeger, L.H.; Chavez, M.A.; Tetteh, E.; Yarrabelli, S.; Pulcini, C.; et al. Exposure to World Health Organization’s AWaRe antibiotics and isolation of multidrug resistant bacteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022, 28, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanichelli, V.; Sharland, M.; Cappello, B.; Moja, L.; Getahun, H.; Pessoa-Silva, C.; Sati, H.; van Weezenbeek, C.; Balkhy, H.; Simão, M.; et al. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book and prevention of antimicrobial resistance. Bull World Health Organ 2023, 101, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Li, G.-H.; Qu, Q.; Zhu, H.-H.; Luo, Y.; Yan, H.; Yuan, H.-Y.; Qu, J. Clinical efficacy of polymyxin B in patients infected with carbapenem-resistant organisms. Infection and drug resistance 2021, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Gandra, S.; Ashok, A.; Caudron, Q.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. The Lancet infectious diseases 2014, 14, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Abbas, M.; Rehman, M.U.; Wang, M.; Jia, R.; Chen, S.; Liu, M.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Q.; et al. Updates on the global dissemination of colistin-resistant Escherichia coli: An emerging threat to public health. Sci Total Environ 2021, 799, 149280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M.; Hassan, B.; Farzana, R.; Ali, Q.; Sands, K.; Mathias, J.; Afegbua, S.; Haque, M.N.; Walsh, T.R.; Mohsin, M. International manufacturing and trade in colistin, its implications in colistin resistance and One Health global policies: a microbiological, economic, and anthropological study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e264–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, N.V.; Kiet, B.T.; Hien, V.B.; Truong, B.D.; Phu, D.H.; Thwaites, G.; Choisy, M.; Carrique-Mas, J. Antimicrobial use through consumption of medicated feeds in chicken flocks in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam: A three-year study before a ban on antimicrobial growth promoters. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0250082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.F.; Silva, D.; Rodrigues, A.; Pina-Vaz, C. Colistin Update on Its Mechanism of Action and Resistance, Present and Future Challenges. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine. 6th Revision 2018. Ranking of medically important antimicrobials for risk management of antimicrobial resistance due to non-human use. Available online: (accessed on.

- EMA. Categorisation of antibiotics used in animals promotes responsible use to protect public and animal health. 2020. Available online: (accessed on.

- Talat, A.; Miranda, C.; Poeta, P.; Khan, A.U. Farm to table: colistin resistance hitchhiking through food. Arch Microbiol 2023, 205, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Schwarz, S.; Wu, C.; Shen, J.; Walsh, T.R.; Wang, Y. Farm animals and aquaculture: significant reservoirs of mobile colistin resistance genes. Environmental Microbiology 2020, 22, 2469–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Saleem, S.; Zafar, A.; Ghafoor, A.; Shahzad, A.B.; Ejaz, H.; Junaid, K.; Jahan, S. Emergence of plasmid-mediated mcr genes from Gram-negative bacteria at the human-animal interface. Gut Pathogens 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wang, G.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J.; Li, R. Emergence and Transmission of Plasmid-Mediated Mobile Colistin Resistance Gene mcr-10 in Humans and Companion Animals. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e02097–02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M.; Brink, A.; Gouws, J.; Mbelle, N.; Naidoo, V.; Pople, T.; Schellack, N.; van Vuuren, M.; Rees, H. The One Health stewardship of colistin as an antibiotic of last resort for human health in South Africa. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2018, 18, e288–e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Mourão, J.; Novais, Â.; Campos, J.; Peixe, L.; Antunes, P. From farm to fork: Colistin voluntary withdrawal in Portuguese farms reflected in decreasing occurrence of mcr-1-carrying Enterobacteriaceae from chicken meat. Environ Microbiol 2021, 23, 7563–7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, M.; Nozawa, Y.; Fukuda, A.; Sato, T.; Yamada, M.; Makita, K.; Tamura, Y. Decreased colistin resistance and mcr-1 prevalence in pig-derived Escherichia coli in Japan after banning colistin as a feed additive. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2021, 24, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Hu, F.; Liu, D.; Lu, J.; Guo, Y.; Xia, X.; et al. Changes in colistin resistance and mcr-1 abundance in Escherichia coli of animal and human origins following the ban of colistin-positive additives in China: an epidemiological comparative study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020, 20, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, C.; Das, T.; Islam, M.S.; Hasib, F.M.Y.; Singha, S.; Dutta, A.; Barua, H.; Islam, M.Z. Colistin Resistance in Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Retail Broiler Meat in Bangladesh. Microb Drug Resist 2023, 29, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Urmi, U.L.; Rana, M.; Sultana, F.; Jahan, N.; Hossain, B.; Iqbal, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Mosaddek, A.S.M.; Nahar, S. High abundance of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in chicken gut-bacteria in Bangladesh. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 17292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.B.; Alam, M.N.; Hasan, M.; Hossain, S.M.B.; Debnath, M.; Begum, R.; Samad, M.A.; Hoque, S.F.; Chowdhury, M.S.R.; Rahman, M.M.; et al. Molecular Detection of Colistin Resistance mcr-1 Gene in Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Chicken. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonia, S.J.; Uddin, K.H.; Shamsuzzaman, S.M. Prevalence of Colistin Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Bangladesh and Molecular Characterization of Colistin Resistance Genes among Them by Polymerase Chain Reaction and Sequencing. Mymensingh Med J 2022, 31, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Ara, B.; Urmi, U.L.; Haque, T.A.; Nahar, S.; Rumnaz, A.; Ali, T.; Alam, M.S.; Mosaddek, A.S.M.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Haque, M.; et al. Detection of mobile colistin-resistance gene variants (mcr-1 and mcr-2) in urinary tract pathogens in Bangladesh: the last resort of infectious disease management colistin efficacy is under threat. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2021, 14, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, A.; Islam, M.Z.; Barua, H.; Rana, E.A.; Jalal, M.S.; Dhar, P.K.; Das, A.; Das, T.; Sarma, S.M.; Biswas, S.K.; et al. Acquisition of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Gene mcr-1 in Escherichia coli of Livestock Origin in Bangladesh. Microb Drug Resist 2020, 26, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawser, Z.; Shamsuzzaman, S.M. Association of Virulence with Antimicrobial Resistance among Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Hospital Settings in Bangladesh. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2022, 12, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousham, E.K.; Nahar, P.; Uddin, M.R.; Islam, M.A.; Nizame, F.A.; Khisa, N.; Akter, S.M.S.; Munim, M.S.; Rahman, M.; Unicomb, L. Gender and urban-rural influences on antibiotic purchasing and prescription use in retail drug shops: a one health study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unicomb, L.E.; Nizame, F.A.; Uddin, M.R.; Nahar, P.; Lucas, P.J.; Khisa, N.; Akter, S.M.S.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, M.; Rousham, E.K. Motivating antibiotic stewardship in Bangladesh: identifying audiences and target behaviours using the behaviour change wheel. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orubu, E.S.F.; Samad, M.A.; Rahman, M.T.; Zaman, M.H.; Wirtz, V.J. Mapping the Antimicrobial Supply Chain in Bangladesh: A Scoping-Review-Based Ecological Assessment Approach. Glob Health Sci Pract 2021, 9, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Akhtar, Z.; Hassan, M.Z.; Chowdhury, S.; Rashid, M.M.; Aleem, M.A.; Ghosh, P.K.; Mah-E-Muneer, S.; Parveen, S.; Ahmmed, M.K.; et al. Pattern of Antibiotic Dispensing at Pharmacies According to the WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) Classification in Bangladesh. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobbe, D.R.; Bassetti, M.; De Rosa, F.G.; Del Bono, V.; Grossi, P.A.; Menichetti, F.; Pea, F.; Rossolini, G.M.; Tumbarello, M.; Viale, P. Ceftolozane/tazobactam: place in therapy. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 2018, 16, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogue, J.M.; Bonomo, R.A.; Kaye, K.S. Ceftazidime/avibactam, meropenem/vaborbactam, or both? Clinical and formulary considerations. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019, 68, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, D.; Lok, J.J.; Earley, M.; Cober, E.; Richter, S.S.; Perez, F.; Salata, R.A.; Kalayjian, R.C.; Watkins, R.R.; Doi, Y. Colistin versus ceftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 66, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-H.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Shen, Y.-B.; Yang, J.; Walsh, T.R.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J. Plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance genes: mcr. Trends in Microbiology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuadraksa, T.; Wichit, S.; Songtawee, N.; Tantimavanich, S.; Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya, C.; Yainoy, S. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-3.5 gene in Citrobacter amalonaticus and Citrobacter sedlakii isolated from healthy individual in Thailand. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2023, 12, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelendova, M.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Sismova, P.; Medvecky, M.; Pomorska, K.; Palkovicova, J.; Nesporova, K.; Jakubu, V.; Jamborova, I.; Zemlickova, H. Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance among human clinical Enterobacterales isolates: National surveillance in the Czech Republic. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1147846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; van Dorp, L.; Shaw, L.P.; Bradley, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Rieux, A.; et al. The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Nature communications 2018, 9, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogry, F.A.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Sultan, I.; Haq, Q.M. Current update on intrinsic and acquired colistin resistance mechanisms in bacteria. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwiek, K.; Woźniak-Biel, A.; Karwańska, M.; Siedlecka, M.; Lammens, C.; Rebelo, A.R.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Kuczkowski, M.; Chmielewska-Władyka, M.; Wieliczko, A. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of mcr-1-positive multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST93, ST117, ST156, ST10, and ST744 isolated from poultry in Poland. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2021, 52, 1597–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.; Spadar, A.; Phelan, J.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Lito, L.; Pinto, M.; Gonçalves, L.; Campino, S.; Clark, T.G.; Duarte, A. A phylogenomic approach for the analysis of colistin resistance-associated genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae, its mutational diversity and implications for phenotypic resistance. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2022, 59, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Zakaria, Z.; Hassan, L.; Faiz, N.M.; Ahmad, N.I. The occurrence and molecular detection of mcr-1 and mcr-5 genes in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from poultry and poultry meats in Malaysia. Frontiers in microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelo, A.; MH, C.L.; Bortolaia, V.; Kjeldgaard, J.; Hendriksen, R. PCR for plasmid-mediated colistin resistance genes, mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4, mcr-5 and variants (multiplex), on DTU National Food Institute. 2018.

- Johura, F.-T.; Tasnim, J.; Barman, I.; Biswas, S.R.; Jubyda, F.T.; Sultana, M.; George, C.M.; Camilli, A.; Seed, K.D.; Ahmed, N. Colistin-resistant Escherichia coli carrying mcr-1 in food, water, hand rinse, and healthy human gut in Bangladesh. Gut pathogens 2020, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdomo, A.; Webb, H.E.; Bugarel, M.; Friedman, C.R.; Francois Watkins, L.K.; Loneragan, G.H.; Calle, A. First Known Report of mcr-Harboring Enterobacteriaceae in the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Yin, W.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Walsh, T.R. Epidemiology of mobile colistin resistance genes mcr-1 to mcr-9. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2020, 75, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemlem, M.; Aklilu, E.; Mohamed, M.; Kamaruzzaman, N.F.; Zakaria, Z.; Harun, A.; Devan, S.S.; Kamaruzaman, I.N.A.; Reduan, M.F.H.; Saravanan, M. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of colistin-resistant Escherichia Coli with mcr-4, mcr-5, mcr-6, and mcr-9 genes from broiler chicken and farm environment. BMC microbiology 2023, 23, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansarli, G.S.; Andreatos, N.; Pliakos, E.E.; Mylonakis, E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of antibiotic treatment duration for bacteremia due to Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019, 63, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Yusuf, M.A.; Siddiqui, U.R.; Debnath, A.C.; Shil, R.C. Frequency and distribution of multidrug resistance enterobacteriaceae isolated from hospital and community acquired urinary tract infection patient attended at a tertiary level care hospital in Dhaka city. 2023.

- Villafuerte, D.; Aliberti, S.; Soni, N.J.; Faverio, P.; Marcos, P.J.; Wunderink, R.G.; Rodriguez, A.; Sibila, O.; Sanz, F.; Martin-Loeches, I. Prevalence and risk factors for Enterobacteriaceae in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology 2020, 25, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Byeon, E.J.; Park, J.J.; Lee, J.; Seo, Y.B. Antibiotic resistance patterns of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from patients with healthcare-associated infections. Infection & Chemotherapy 2021, 53, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, G.-B.; Doi, Y.; Shen, J.; Walsh, T.R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, X. MCR-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak in China. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2017, 17, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Johnson, A.P. Transferable resistance to colistin: a new but old threat. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2016, 71, 2066–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Yang, H.; Qiu, S.; Song, H. Plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in a multidrug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolate from an infant with acute diarrhea in China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 103, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, S.M.; Raihana, S.; Ali, N.B.; Iqbal, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, A.N.S.; Karim, F.; Karim, M.A.; Hassan, A.; Jackson, B.; et al. Bangladesh: a success case in combating childhood diarrhoea. J Glob Health 2019, 9, 020803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, N.; Nobel, N.U.; Sakib, N.; Liza, S.M.; Khan, S.T.; Billah, B.; Parvez, A.K.; Haque, A.; Talukder, A.A.; Dey, S.K. Molecular and Epidemiologic Analysis of Diarrheal Pathogens in Children With Acute Gastroenteritis in Bangladesh During 2014–2019. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2020, 39, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Nuzhat, S.; Fahim, S.M.; Palit, P.; Flannery, R.L.; Kyle, D.J.; Mahfuz, M.; Islam, M.M.; Sarker, S.A.; Ahmed, T. Antibiotic exposure among young infants suffering from diarrhoea in Bangladesh. J Paediatr Child Health 2021, 57, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedher, M.B.; Baron, S.A.; Riziki, T.; Ruimy, R.; Raoult, D.; Diene, S.M.; Rolain, J.-M. Massive analysis of 64,628 bacterial genomes to decipher water reservoir and origin of mobile colistin resistance genes: is there another role for these enzymes? Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghapour, Z.; Gholizadeh, P.; Ganbarov, K.; Bialvaei, A.Z.; Mahmood, S.S.; Tanomand, A.; Yousefi, M.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Yousefi, B.; Kafil, H.S. Molecular mechanisms related to colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Infection and drug resistance 2019, 12, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.-x.; Huang, Y.-l.; Ma, J.-h.; Zhou, H.-w.; Fang, Y.; Cai, J.-c.; Hu, Y.-y.; Zhang, R. Detection of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates from an infant with diarrhea in China. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2016, 60, 5099–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Luo, J.; Xiao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X. Prevalence of colistin-resistant mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli isolated from children patients with diarrhoea in Shanghai, 2016–2021. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2023, 34, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monira, S.; Shabnam, S.A.; Ali, S.; Sadique, A.; Johura, F.-T.; Rahman, K.Z.; Alam, N.H.; Watanabe, H.; Alam, M. Multi-drug resistant pathogenic bacteria in the gut of young children in Bangladesh. Gut pathogens 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalej, S.M.; Meziou, M.R.; Rhimi, F.M.; Hammami, A. Comparison of disc diffusion, Etest and agar dilution for susceptibility testing of colistin against Enterobacteriaceae. Lett Appl Microbiol 2011, 53, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Shiraishi, T.; Hiyama, Y.; Honda, H.; Shinagawa, M.; Usui, M.; Kuronuma, K.; Masumori, N.; Takahashi, S.; Tamura, Y. Contribution of novel amino acid alterations in pmrA or pmrB to Colistin resistance in mcr-negative Escherichia coli clinical isolates, including major multidrug-resistant lineages O25b: H4-ST131-H 30Rx and Non-x. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2018, 62, e00864–00818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Bontron, S.; Villegas, M.-V.; Ozdamar, M.; Türkoglu, S.; Nordmann, P. The mgrB gene as a key target for acquired resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2015, 70, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannatelli, A.; Giani, T.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Di Pilato, V.; Arena, F.; Conte, V.; Tryfinopoulou, K.; Vatopoulos, A.; Rossolini, G.M. MgrB inactivation is a common mechanism of colistin resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of clinical origin. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2014, 58, 5696–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowiak, M.; Baumann, B.; Fischer, J.; Thomas, K.; Deneke, C.; Hammerl, J.A.; Szabo, I.; Malorny, B. Development of a novel mcr-6 to mcr-9 multiplex PCR and assessment of mcr-1 to mcr-9 occurrence in colistin-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates from environment, feed, animals and food (2011–2018) in Germany. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.H.; AL-Kadmy, I.; Taha, B.M.; Hussein, J.D. Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: a comprehensive review. Molecular Biology Reports 2021, 48, 2897–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formosa, C.; Herold, M.; Vidaillac, C.; Duval, R.; Dague, E. Unravelling of a mechanism of resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae using atomic force microscopy. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2015, 70, 2261–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogry, F.A.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Sultan, I.; Haq, Q.M.R. Current update on intrinsic and acquired colistin resistance mechanisms in bacteria. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 677720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, M.; Vargas, M.; Regueiro, V.; Llompart, C.; Albert, í.S.; Bengoechea, J.A. Capsule polysaccharide mediates bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun, 2004; 72, 7107–7114. [Google Scholar]

- Bengoechea, J.A.; Skurnik, M. Temperature-regulated efflux pump/potassium antiporter system mediates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides in Yersinia. Molecular microbiology 2000, 37, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puja, H.; Bolard, A.; Noguès, A.; Plésiat, P.; Jeannot, K. The efflux pump MexXY/OprM contributes to the tolerance and acquired resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to colistin. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2020, 64, e02033–02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NationRL, L. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009, 22, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarman, A.F.; Long, S.E.; Robertson, S.E.; Nasrin, S.; Alam, N.H.; McGregor, A.J.; Levine, A.C. Sex and gender differences in acute pediatric diarrhea: a secondary analysis of the Dhaka study. Journal of epidemiology and global health 2018, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, W.; Jameel, A.Y.; Amidy, K.S.K. Microorganisms and viruses causing diarrhea in infants and primary school children and their relation with age and sex in Zakho city, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. 2015.

- Gupta, N.; Limbago, B.M.; Patel, J.B.; Kallen, A.J. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiology and prevention. Clinical infectious diseases 2011, 53, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.Z.; Hollingshead, C.M.; Kendall, B. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Hansen, G.T. Continuous Evolution: Perspective on the Epidemiology of Carbapenemase Resistance Among Enterobacterales and Other Gram-Negative Bacteria. Infect Dis Ther 2021, 10, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kasiakou, S.K.; Saravolatz, L.D. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clinical infectious diseases 2005, 40, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.; Sharma, D.; Singh, A.; Sunita, K. Colistin Resistance and Management of Drug Resistant Infections. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022, 2022, 4315030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Walsh, T.R. A colistin crisis in India. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godman, B.; Egwuenu, A.; Haque, M.; Malande, O.O.; Schellack, N.; Kumar, S.; Saleem, Z.; Sneddon, J.; Hoxha, I.; Islam, S.; et al. Strategies to Improve Antimicrobial Utilization with a Special Focus on Developing Countries. Life (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, T.A.; Urmi, U.L.; Islam, A.B.M.M.K.; Ara, B.; Nahar, S.; Mosaddek, A.S.M.; Lugova, H.; Kumar, S.; Jahan, D.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Haque, M.; Islam, S.; Godman, B. Detection of qnr genes and gyrA mutation to quinolone phenotypic resistance of UTI pathogens in Bangladesh and the implications. Appl Pharm Sci, 2022; 12, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Shanta, A.S.; Islam, N.; Asad, M.A.; Akter, K.; Habib, M.B.; Hossain, M.J.; Nahar, S.; Godman, B.; Islam, S. Resistance and Co-resistance of Metallo-Beta-Lactamase Genes in Diarrheal and Urinary Tract Pathogens in Bangladesh. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Godman, B. Potential strategies to improve antimicrobial utilisation in hospitals in Bangladesh building on experiences across developing countries. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science 2021, 20, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, M.G.D.; Anwar, M.M.U.; Sumon, S.A.; Hassan, M.Z.; Mohona, T.M.; Rahman, A.; Abdullah, S.; Islam, M.S.; Kaydos-Daniels, S.C.; Styczynski, A.R. Rationale and guidance for strengthening infection prevention and control measures and antimicrobial stewardship programs in Bangladesh: a study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, C.L.; Islam, S.; Saha, A.; Arjumand, M.; Alam, N.H.; Faruque, A.; Salam, M.; Shin, J.; Hecht, D.; Weintraub, A. Association of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis infection with inflammatory diarrhea. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008, 47, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. What is middle class about the middle classes around the world? Journal of economic perspectives 2008, 22, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuma, T.; Nakamura, M.; Totake, H.; Fukunaga, Y. Microbial contamination of enteral feeding formulas and diarrhea. Nutrition 2000, 16, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djim-Adjim-Ngana, K.; Oumar, L.A.; Mbiakop, B.W.; Njifon, H.L.M.; Crucitti, T.; Nchiwan, E.N.; Yanou, N.N.; Deweerdt, L. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacterial urinary infections and associated risk factors in small children of Garoua, Northern Cameroon. Pan African Medical Journal 2020, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Zee, A.; Roorda, L.; Bosman, G.; Ossewaarde, J.M. Molecular diagnosis of urinary tract infections by semi-quantitative detection of uropathogens in a routine clinical hospital setting. PloS one 2016, 11, e0150755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satlin, M.J.; Lewis, J.S.; Weinstein, M.P.; Patel, J.; Humphries, R.M.; Kahlmeter, G.; Giske, C.G.; Turnidge, J. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Position Statements on Polymyxin B and Colistin Clinical Breakpoints. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020, 71, e523–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M100, C. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2018, 28th Volume.

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nature protocols 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.; Mathur, P.; Das, A.; Kapil, A.; Gupta, B.; Bhoi, S.; Farooque, K.; Sharma, V.; Misra, M.C. Evaluation of susceptibility testing methods for polymyxin. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 2010, 14, e596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.; Giske, C.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clinical microbiology and infection 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.R.; Bortolaia, V.; Kjeldgaard, J.S.; Pedersen, S.K.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Hansen, I.M.; Guerra, B.; Malorny, B.; Borowiak, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; et al. Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance determinants, mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 for surveillance purposes. Euro Surveill 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacteria typeb | Number of isolates carrying mcr genes | Percentage of mcr-positive isolates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Escherichia spp.c | 20 | 120 | 14.3 |

| Shigella flexneri | 5 | 8 | 38.5 |

| Citrobacter spp.d | 5 | 15 | 25.0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 | 16 | 11.1 |

| Enterobacter hormaechei | 2 | 8 | 20.0 |

| Pseudomonas parafulva | 1 | 2 | 33.3 |

| Aeromonas caviae. | 0 | 3 | - |

| Acinetobacter spp | 0 | 2 | - |

| Bacillus cereus | 0 | 1 | - |

| Bacterium endosymbiont | 0 | 1 | - |

| Morganella morganii | 0 | 3 | - |

| Serratia marcescens | 0 | 1 | - |

| Stenotrophomonas maltoph | 0 | 7 | - |

| Vibrio neocaledonicus | 0 | 1 | - |

| Cronobacter sakazakii | 0 | 1 | - |

| Enterococcus faecium | 0 | 1 | - |

| Total | 35 | 190 | |

| Presence of mcr gene varients | Phenotypic susceptibility | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sensitive | resistance | |||

| mcr-1 | Positive (7) | 1 | 6 | .001 |

| Negative (218) | 155 | 63 | ||

| mcr-2 | Positive (17) | 3 | 14 | .000 |

| Negative (208) | 153 | 55 | ||

| mcr-3 | Positive (13) | 0 | 13 | .000 |

| Negative (212) | 156 | 56 | ||

| combined | Positive (35) | 3 | 32 | .000 |

| Negative (190) | 152 | 38 | ||

|

mcr-possitive isolate ID |

Identified bacteriaa |

Identified mcr gene varient | Phenotypic colistin susceptibility by MIC (µg/mL)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBD009 | Shigella flexneri | mcr-3 | 256 |

| PBD014 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | mcr-2 | 128 |

| PBD018 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 8 |

| PBD021 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 128 |

| PBD022 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 32 |

| PBD027 | Citrobacter portucalensis | mcr-2 | .5 |

| PBD028 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 256 |

| PBD033C2 | Pseudomonas parafulva | mcr-1 | 128 |

| PBD35 | Citrobacter portucalensis | mcr-2 | 8 |

| PBD35C1 | Citrobacter freundii | mcr-2 | 128 |

| PBD35C2 | Citrobacter freundii | mcr-2 | 1 |

| PBD039 | Escherichia fergusonii | mcr-2 | 256 |

| PBD040 | Citrobacter europaeus | mcr-2 | 64 |

| PBD043 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | mcr-2 | 16 |

| PBD058 | Escherichia coli | mcr-2, mcr-3 | 8 |

| PBD062 | Escherichia fergusonii | mcr-2 | 32 |

| PBD072 | Escheril chia fergusonii | mcr-2 | 64 |

| PBD077 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | 8 |

| PBD077C1 | Shigella flexneri | mcr-1 | 32 |

| PBD077C2 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1,mcr-2 | 128 |

| PBD080C2 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | 2 |

| PBD081C3 | Escherichia coli | mcr-2 | 32 |

| PBD081C4 | Enterobacter hormaechei | mcr-3 | 128 |

| PBD081C1 | Escherichia coli | mcr-2 | 32 |

| PBD082 | Shigella flexneri | mcr-1 | 128 |

| PBD083C1 | Shigella flexneri | mcr-3 | 32 |

| PBD083C2 | Escherichia coli | mcr-2 | 64 |

| PBD084C1 | Enterobacter hormaechei | mcr-2 | 128 |

| PBD84C2 | Escherichia coli | mcr-2 | 4 |

| PBD090 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 64 |

| PBD096 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 8 |

| PBD107 | Escherichia coli | mcr-1 | 8 |

| PBD114 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 8 |

| PBD116 | Escherichia coli | mcr-3 | 64 |

| PBD117 | Shigella flexneri | mcr-3 | 64 |

| List of antibiotics tested (n = 17, from eight drug-classes) | Phenotypic susceptibilities of mcr-positive diarrheal isolates | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug class | Antibiotic name | PBD009 | PBD014 | PBD018 | PBD021 | PBD022 | PBD027 | PBD028 | PBD033C2 | PBD035 | PBD035C1 | PBD035C2 | PBD039 | PBD040 | PBD043 | PBD058 | PBD062 | PBD072 | PBD077 |

| β-lactam with β-lactamase inhibitor | Amoxi-clava | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | S | R | I | R | I | S | S | S |

| Cephalosporins | Cefuroxime-G2 | R | R | R | R | I | I | I | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S |

| Cefixime-G3 | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | |

| Cefepime-G4 | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | I | I | I | R | I | R | I | R | R | S | |

| Carbapenems | Imipenem | R | R | I | R | R | I | I | R | I | R | S | I | I | R | S | I | R | S |

| Meropenem | R | R | S | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | I | S | S | S | S | R | S | |

| Quinolone and fluoroquinolones | Nalidixic acid | I | S | R | I | I | I | I | R | I | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R |

| Ciprofloxacin | R | S | R | S | S | S | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | S | I | R | I | R | |

| Levofloxacin | R | S | R | S | S | S | I | R | S | I | S | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | |

| Lomefloxacin | S | S | R | S | I | S | R | R | I | R | R | R | S | I | R | R | R | R | |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin | S | S | I | S | R | S | I | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | R | R | R |

| Amikacin | R | S | I | S | S | S | R | S | S | I | I | R | I | R | S | I | I | I | |

| Netilmicin | S | S | I | I | S | S | R | S | S | S | I | I | R | S | R | S | R | I | |

| Tobramycin | S | S | S | S | R | S | R | I | S | S | S | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | |

| Polymyxins | Colistin | R | S | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R |

| Nitrofuran | Nitrofurantoin | I | R | I | R | R | I | R | R | S | I | S | S | I | R | I | R | I | I |

| Trimethoprim | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | S | S | R | S | R | I | S | R | S | R | R | S | S | S | R | R | R | R |

| MDR statuse | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Demography | Number (%) of different mcr-gene variants | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

mcr-1 positive (n = 7) |

mcr-1 negative (n = 218) |

|||

| Gender | Male | 5 (3.8) | 125 (96.2) | 0.702* |

| Female | 2 (2.1) | 94 (97.9) | ||

| Age group (years) | <1 | 4 (4.6) | 83 (95.4) | 0.707* |

| 1-5 | 3 (3.3) | 88 (96.7) | ||

| 6-10 | 0 | 12 (100) | ||

| 11-15 | 0 | 5 (100) | ||

| >15 | 0 | 30 (100) | ||

|

mcr-2 positive (n = 17) |

mcr-2 negative (n = 208) |

|||

| Gender | Male | 8 (6.2) | 122 (93.8) | 0.445* |

| Female | 9 (9.5) | 87 (90.5) | ||

| Age group (years) | <1 | 8 (9.2) | 79 (90.8) | 0.480* |

| 1-5 | 4 (4.4) | 87 (95.6) | ||

| 6-10 | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | ||

| 11-15 | 0 | 5 (100) | ||

| >15 | 4 (13.3) | 26 (86.7) | ||

|

mcr-3 positive (n = 13) |

mcr-3 negative (n = 212) |

|||

| Gender | Male | 7 (5.4) | 123 (94.6) | 0.779* |

| Female | 6 (6.3) | 89 (93.7) | ||

| Age group (years) | <1 | 5 (5.7) | 82 (94.3) | 0.781* |

| 1-5 | 4 (4.4) | 87 (87) | ||

| 6-10 | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | ||

| 11-15 | 0 | 5 (100) | ||

| >15 | 3 (10.0) | 27 (90.0) | ||

|

mcr-1 to mcr-3 positive (n = 35) |

mcr-1 to mcr-3 negative (n = 190) |

|||

| Gender | Male | 19 (14.6) | 111 (85.4) | 0.711* |

| Female | 16 (16.8) | 79 (83.2) | ||

| Age group (years) | <1 | 15 (17.2) | 72 (82.8) | 0.503* |

| 1-5 | 11 (12.1) | 80 (87.9) | ||

| 6-10 | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | ||

| 11-15 | 0 | 5 (100) | ||

| >15 | 7 (23.3) | 23 (76.7) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).