Submitted:

28 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Tackling energy poverty and worst-performing buildings.

- -

- Redevelopment of public buildings.

- -

- Decarburization of heating and cooling.

2. State-of-the-Art

- -

- Building replacement, a radical operation involving the demolition of the existing built-up area and new construction; it is the extreme ratio, to be applied when there are no physical and social prerequisites and requirements such that an artifact can be reused over time. This option is often considered suitable for the suburbs [8], where, for some, it seems that the “principle of erasure and rapid replacement should prevail rather than that of durability, that is, of the city building on itself over time, on its footprints and morphological traces” (Valente, 2014) [9]. Building replacement poses the problem of disposing of those non-de-constructible structures that produce waste, as well as the erasure of the intangible heritage of architectural design experience, often never completed, and the identity heritage that has been formed over time.

- -

- Construction on the built, an operation that results in layering and overlaying on the existing built; the image of the Theatre of Marcellus in Rome or the Roman theater in Lecce and so many other historic buildings testify to how historically the practice of building on the built has always been used, how it belongs to the history of architecture and the history of cities, even those that would seem to have stabilized over time at a given historical epoch. Some of Herzog&de Meuron’s projects, including the aforementioned Hamburg Philharmonic, are indicative. “Regarding the city in which degraded and abandoned areas are multiplying, an awareness of working is maturing that brings back to the center of the practice of architectural and urban design the theme of building on the built, and which is accompanied by an extended critical attention to the notion of heritage (not only from the side of protection practices) and the common good” (Valente 2014) [10].

- -

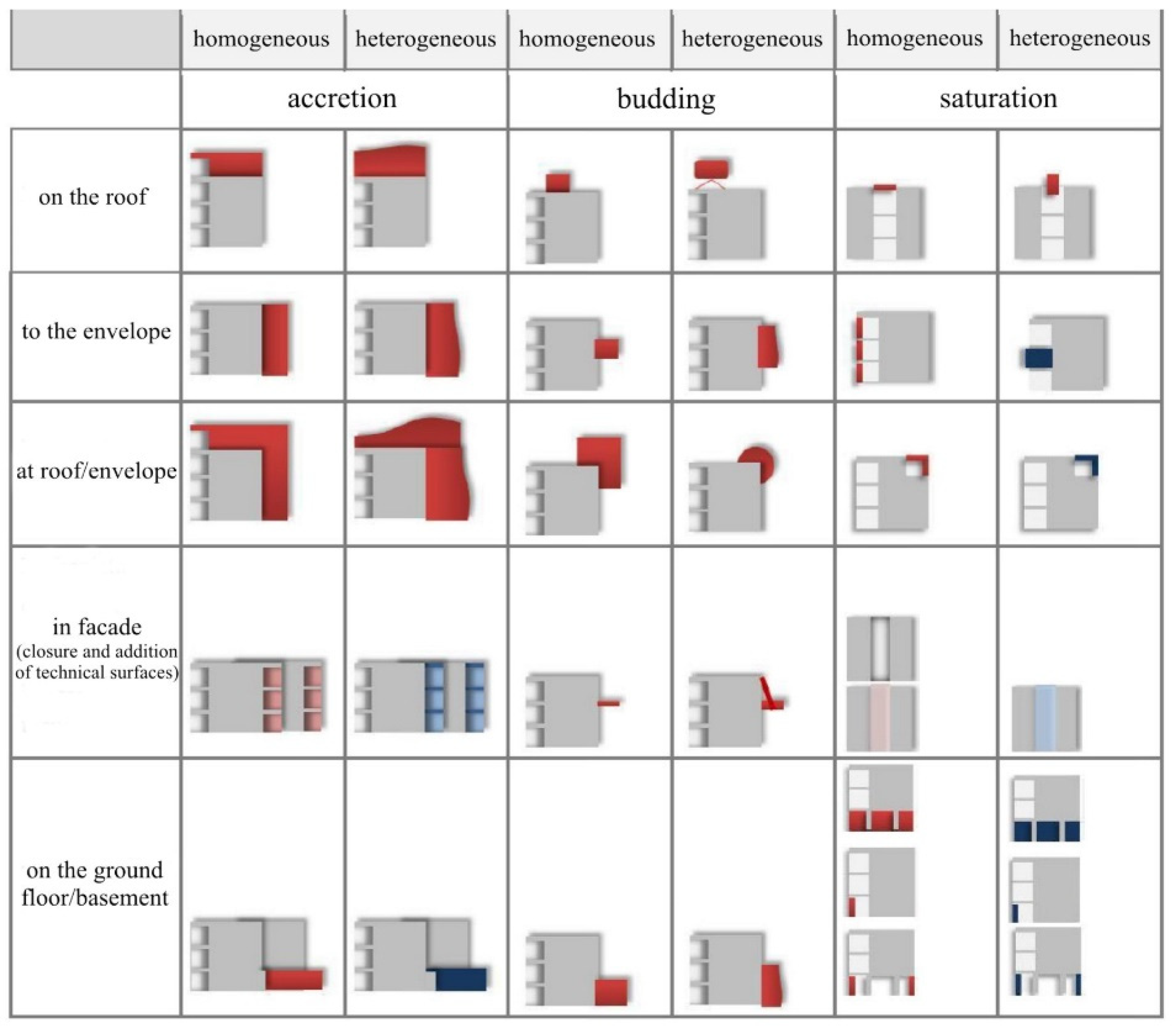

- Transformation, more or less profound, an operation that produces results of different intensities in which volumetric addition and subtraction play a fundamental role, practiced according to different criteria, intensities and dimensions (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The need for the built environment to be alive is evidenced by a huge built heritage that over the centuries has undergone profound transformations on a morphological, typological and functional level: traditional architectures and buildings have welcomed changes of all kinds, contributing to their preservation over time, even taking on sometimes completely different connotations. By this process, they have enabled the transmission of the building artefact, which, if no longer used due to inability to perform certain functions or inadequate with respect to contemporary needs in terms of energy, technology, function and morphology, would have decayed or become an archaeological find. “The present condition of the urban building stock, especially in Europe, at a time of impending economic crisis of which no reasonable conclusion is in sight, has made transformation one of the few feasible programs by which an attempt is made to combat the waste that played a decisive part in triggering the crisis, waste of energy, time, and resources of all kinds due to the unnecessary movement of men and goods and the unlimited production of waste, the difficult accessibility of urban services, and the distance between residences and places of work [... ] Architecture is continuously transformed by those who design and build it; but it is also true that, considering it as an expression of the society and culture of a given time, it must be admitted that it seems, in its continuous modification, something similar to a living organism that undergoes continuous metamorphoses, especially if one accepts of this last word the biological meaning that usually refers to relevant and conspicuous transformations, as it happens for example in reptiles or worms that become butterflies” (Portoghesi 2012) [11]. There are interventions that contemplate re-functionalization, understood as an intervention designed to give a new destination compatible with the context. The example of the residential transformation of the gasometers in Vienna, as described in an article, is given in this regard: “The most important redevelopment intervention, which still represents one of the finest examples of rehabilitation, took place in Vienna in the 1990s, and the dynamism of the project suggests that there may be further developments in the coming years. Built in 1896 in the Viennese district of Simmering, a central area of the Austrian capital, the “Gasometres” (name declined in the plural because the plant-the largest in Europe-was made up of four structures) was decommissioned in 1984. Declared a national monument, the gasometer was used in various ways and by various entities for ten years until the city of Vienna decided in 1995 to hold an international design competition to restore the four monuments. A rather ‘open’ call for new ideas, with the only restriction on the intended use: residential, with attached services. And, it goes without saying, the preservation of the original external structure, except for the possibility of creating small openings in the wall face such, however, as not to compromise the original decorations. For gasometers A, B and C are chosen respectively: a renowned designer such as Jean Nouvel (whose ‘touch’ is evident in the creation of a covered plaza with a translucent roof that, through a play of refractions, synthesizes the old-new combination) and two Austrian firms, Coop Himmelbau (creator of the addition of three volumes to the existing facade) and Manfred Wedhorn, which adopted the more “green” approach, adding terraces and interior gardens. The design of Gasometer D, on the other hand, is awarded to architect Wilhelm Holzbauer, winner of a specific open competition for ideas.” [12]. Other cases, on the other hand, shown below through images, represent interventions in the transformation of buildings and contexts that originally arose with a residential destination that, during redevelopment, retained the same destination. It is precisely on these types of interventions that the research dwells, with the aim of examining how, around the residential functional constant, morphological variables can be grafted according to criteria of eco-sustainability and functional, spatial and aesthetic-formal quality.

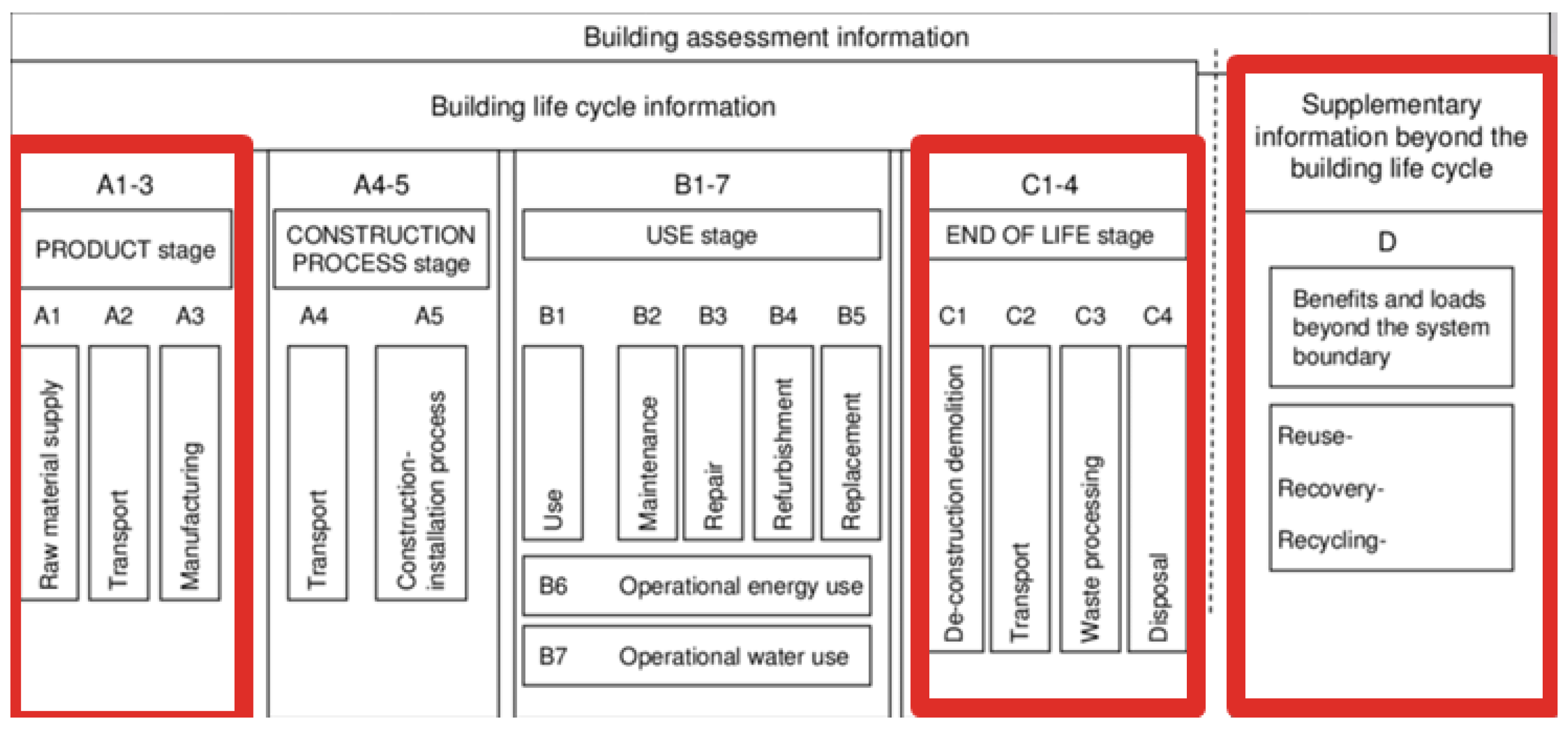

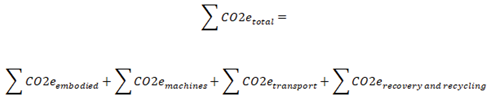

3. Tools and Methods

- -

- Module ‘A’ is mainly inherent to the choice of materials; the database used for this phase (from cradle to gate) is the University of Bath’s Inventory Carbon&Energy (ICE) [14]. In the case of composite products, reference was made to the EPD (Environmental Product Declaration) inventory.

- -

- Module ‘C’ includes deconstruction of the building and transportation of materials to disposal or recovery/recycling sites. Emissions reported in the data sheets of demolition equipment, and their time of use, were used to calculate the EC.

- -

- Module ‘D’ includes impacts/benefits associated with demolition, transportation, and waste disposal/treatment. Potential positive impacts however can be obtained from reuse and recycling after end of life.

3.1. Concept Design

- -

- replacement involves the replacement of functional elements or parts with others of superior performance or new performance, not guaranteed by the original elements;

- -

- integration concerns the addition of building elements to existing parts such as sub-systems or building components, parts that are not removed but remain in situ and are, possibly, subject to maintenance and restoration, with the purpose of increasing existing performance or adding new performance;

- -

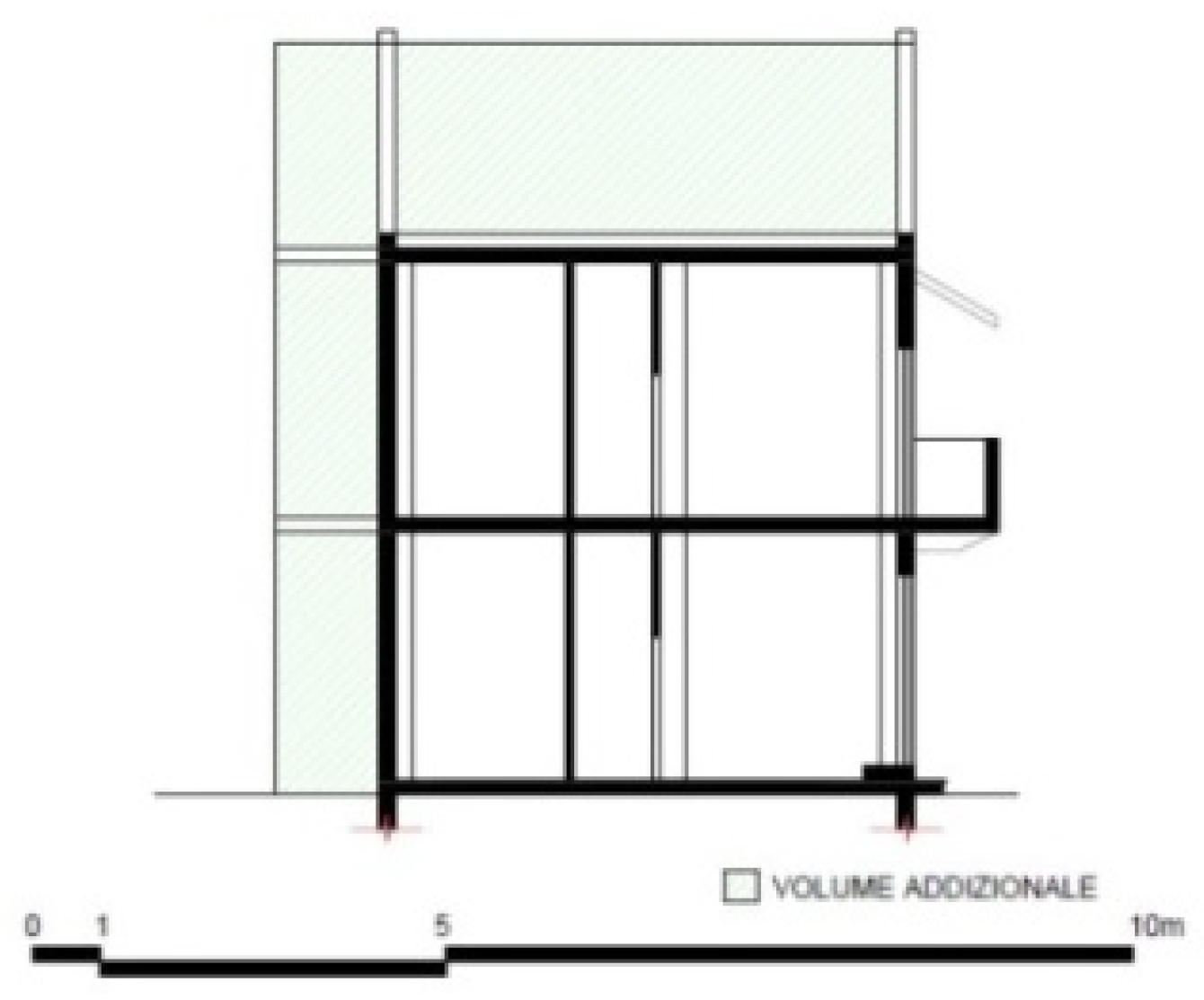

- addition concerns the action aimed at adding technical elements, parts of buildings or entire volumes to the building, as an extension of the original building (Figure 5);

- -

- final subtraction concerns the action aimed at eliminating technical elements, factory parts or entire volumes, in order to achieve new or higher performance, due to the new configuration of the building.

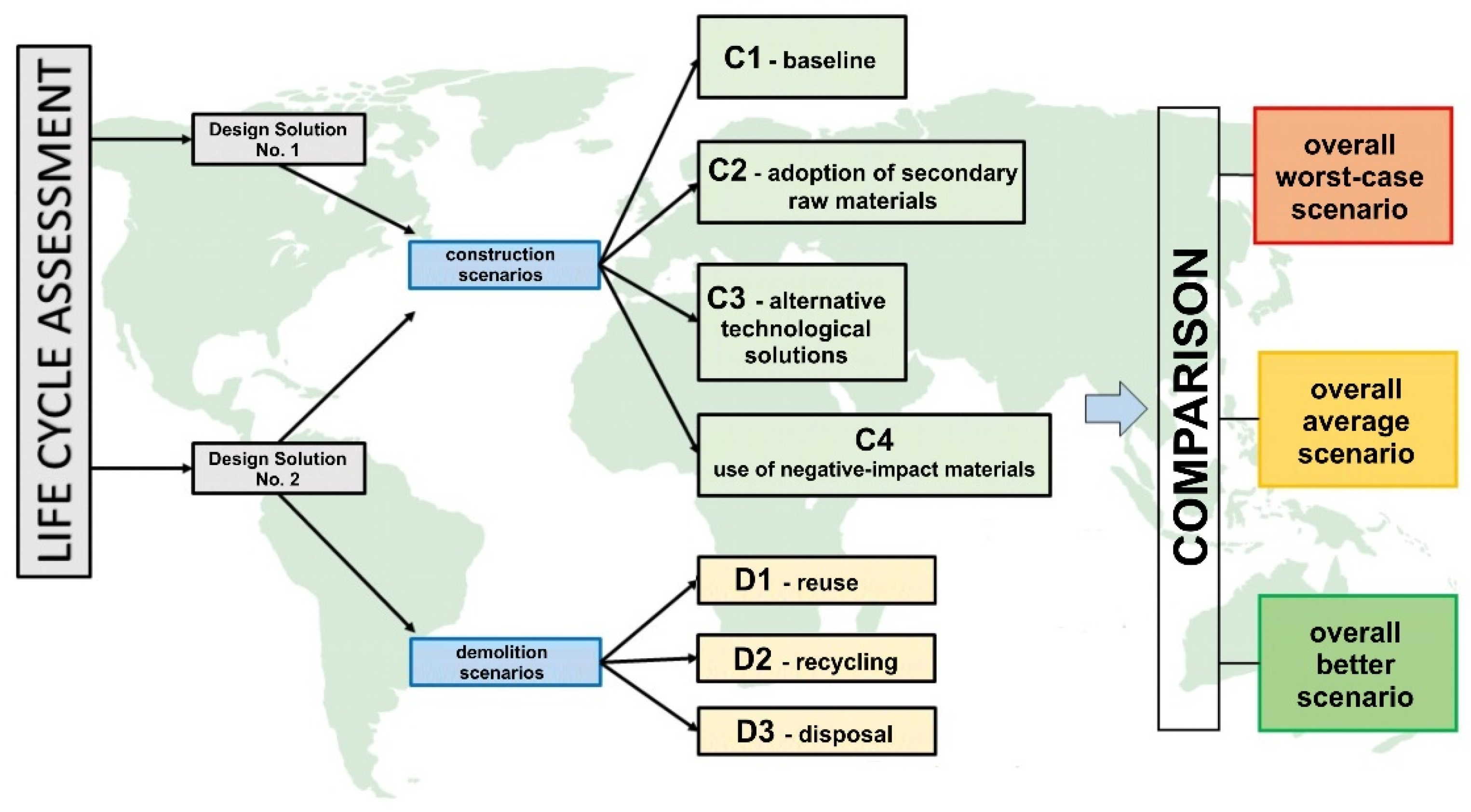

3.2. Construction Scenarios

3.3. Demolition Scenarios

Scenario D1—Reuse

Scenario D2—Recycling

Scenario D3—Disposal

3.4. Methodological Approach

|

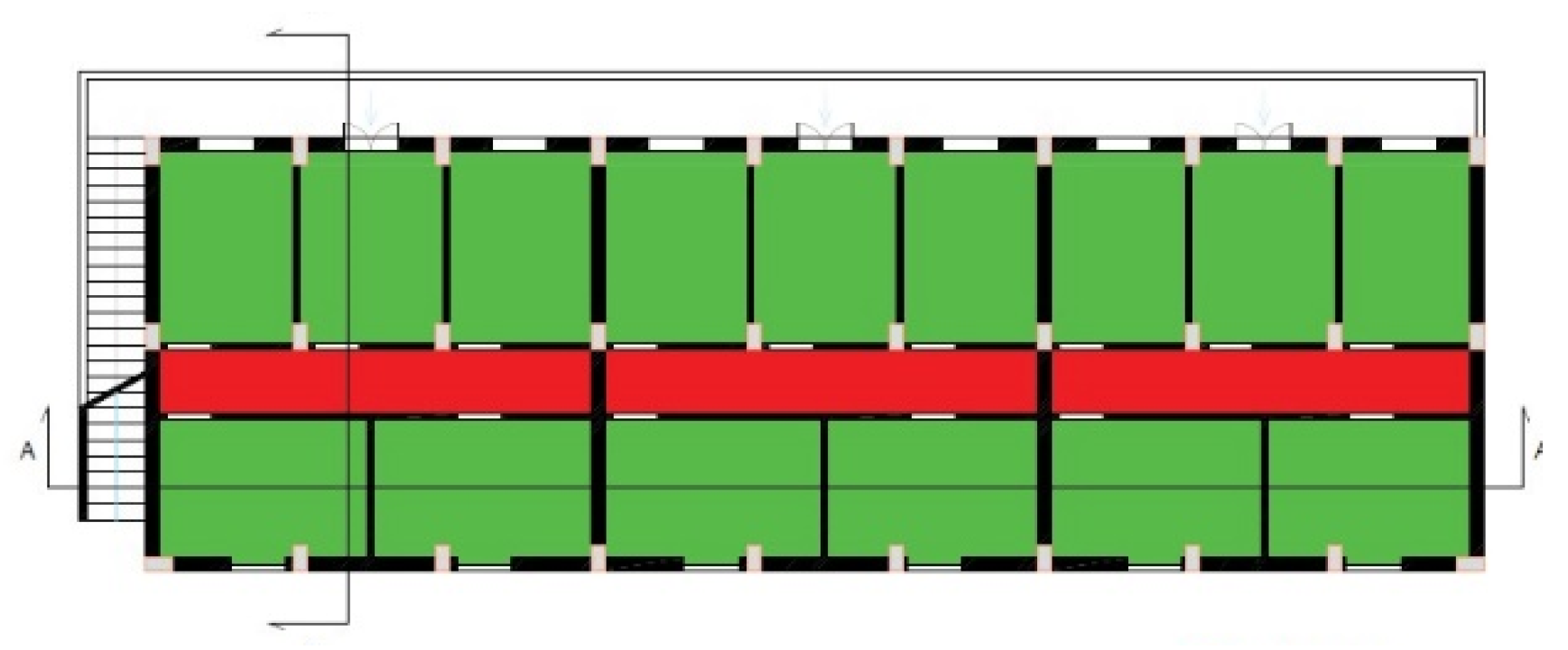

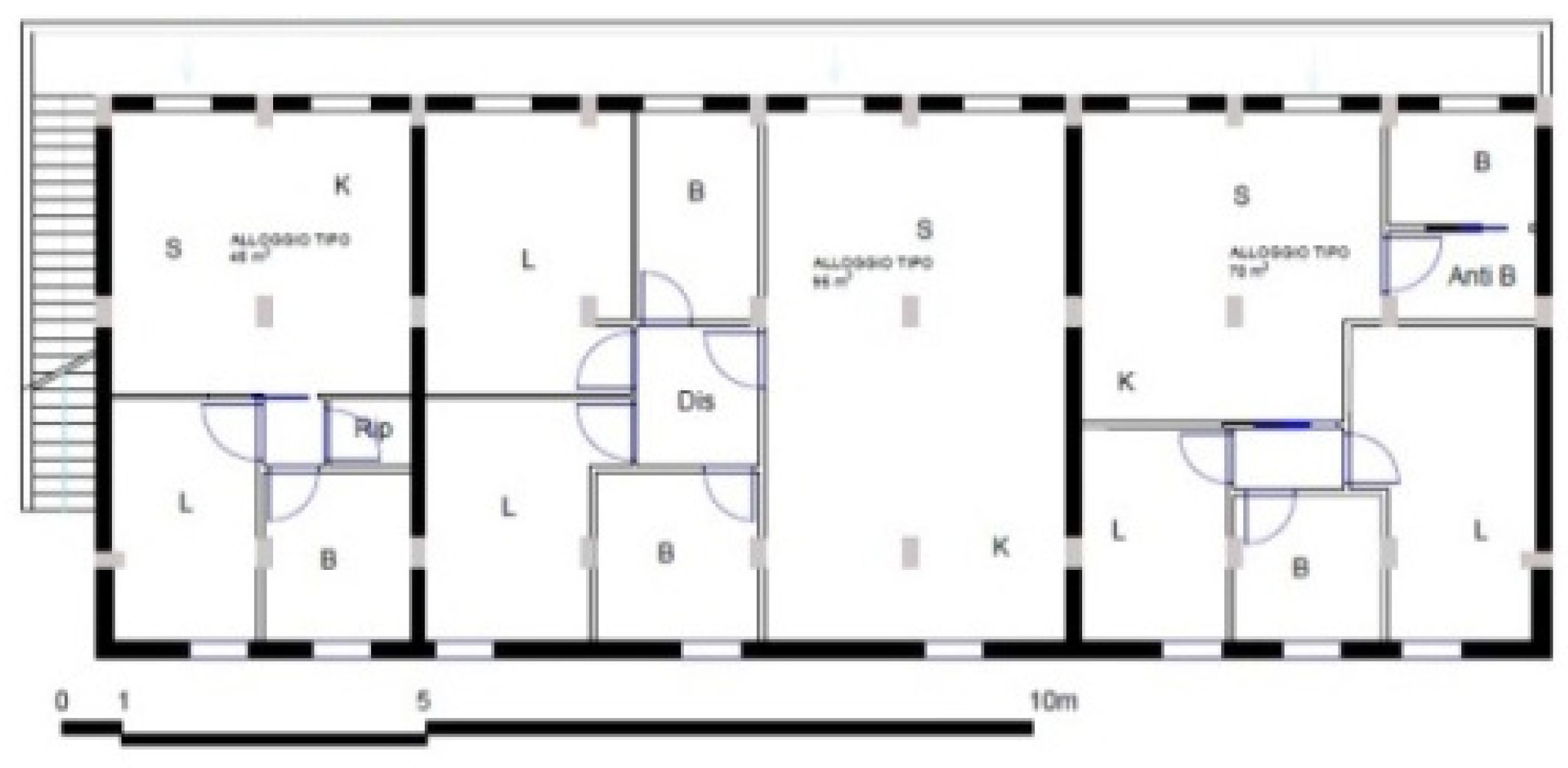

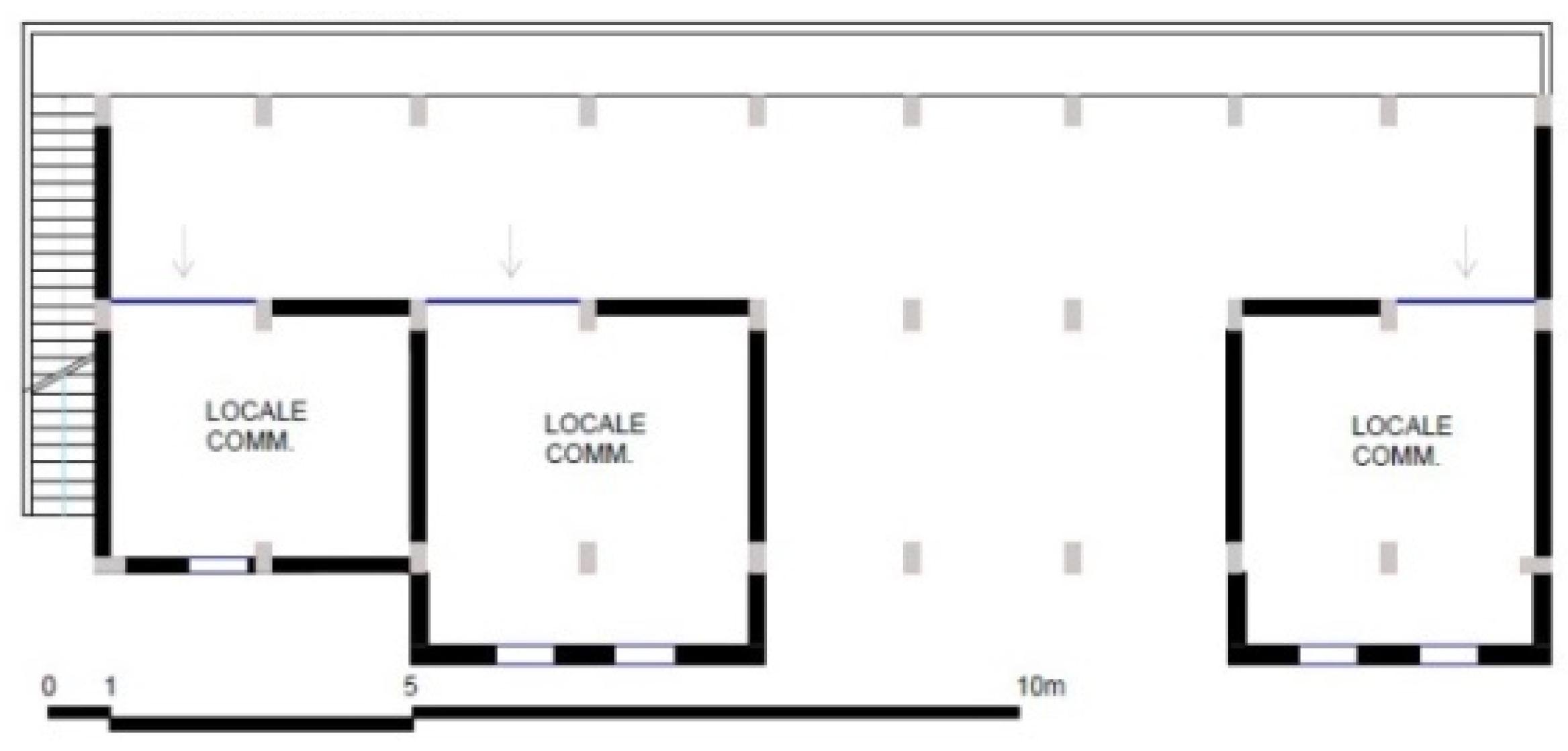

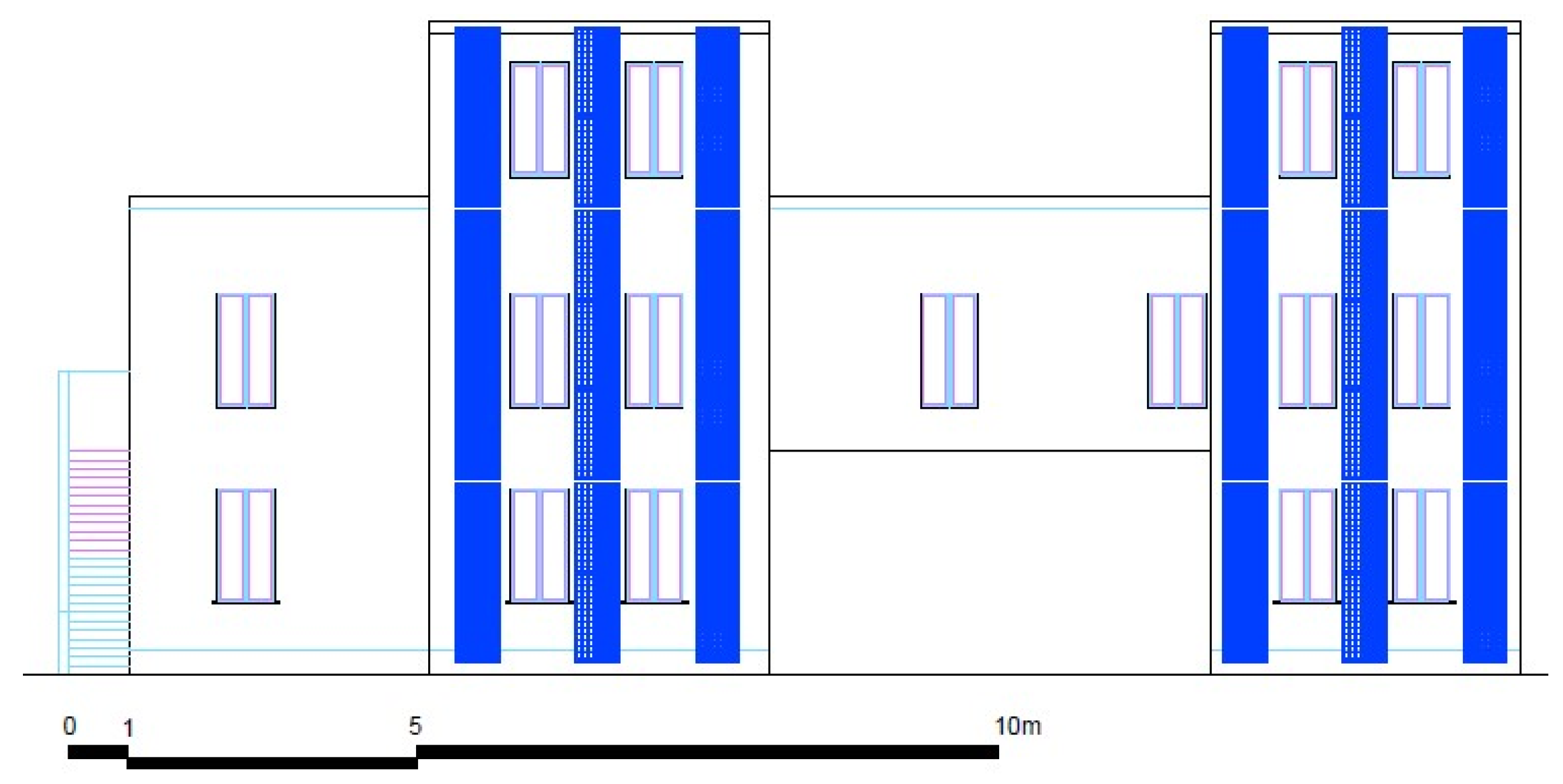

4. Case Study: Refurbishment and Restyling of a Social Housing Complex in Southern Italy

4.1. Description of the Case Study

4.2. Design Hypotheses

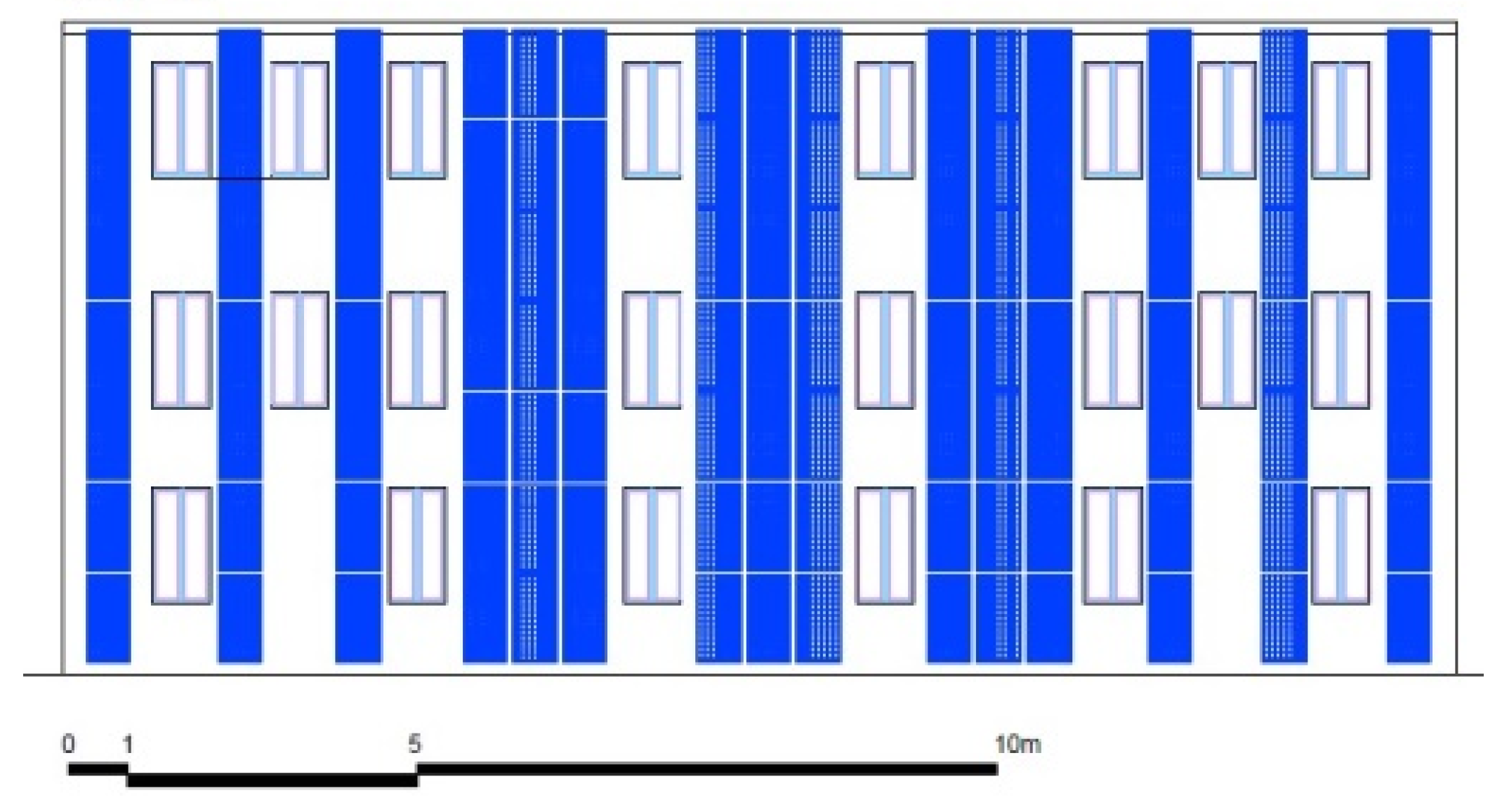

4.3. Design Solution No. 1: Construction

- -

- The addition structure on the south front is steel, consisting of HEB180 columns, edge beams with IPE330 profiles, interior beams with IPE220 profiles, and IPE120 secondary beams. IPE 330 profiles were retained for the central part.

- -

- The external envelope, which forms the facade on the additional body, consists of photovoltaic panels on the elevation, alternating with appropriate openings. A 15cm-thick rock wool insulation layer is provided, incorporated within the HEB180 load-bearing metal profile, a 10cm air gap with modular breaks of 100x50mm steel box profiles such that a 12.5cm-thick fiber cement slab can be attached, followed by an exterior finishing layer. To the latter are doweled 50x50mm supports essential for fixing the photovoltaic panels on the facade.

- -

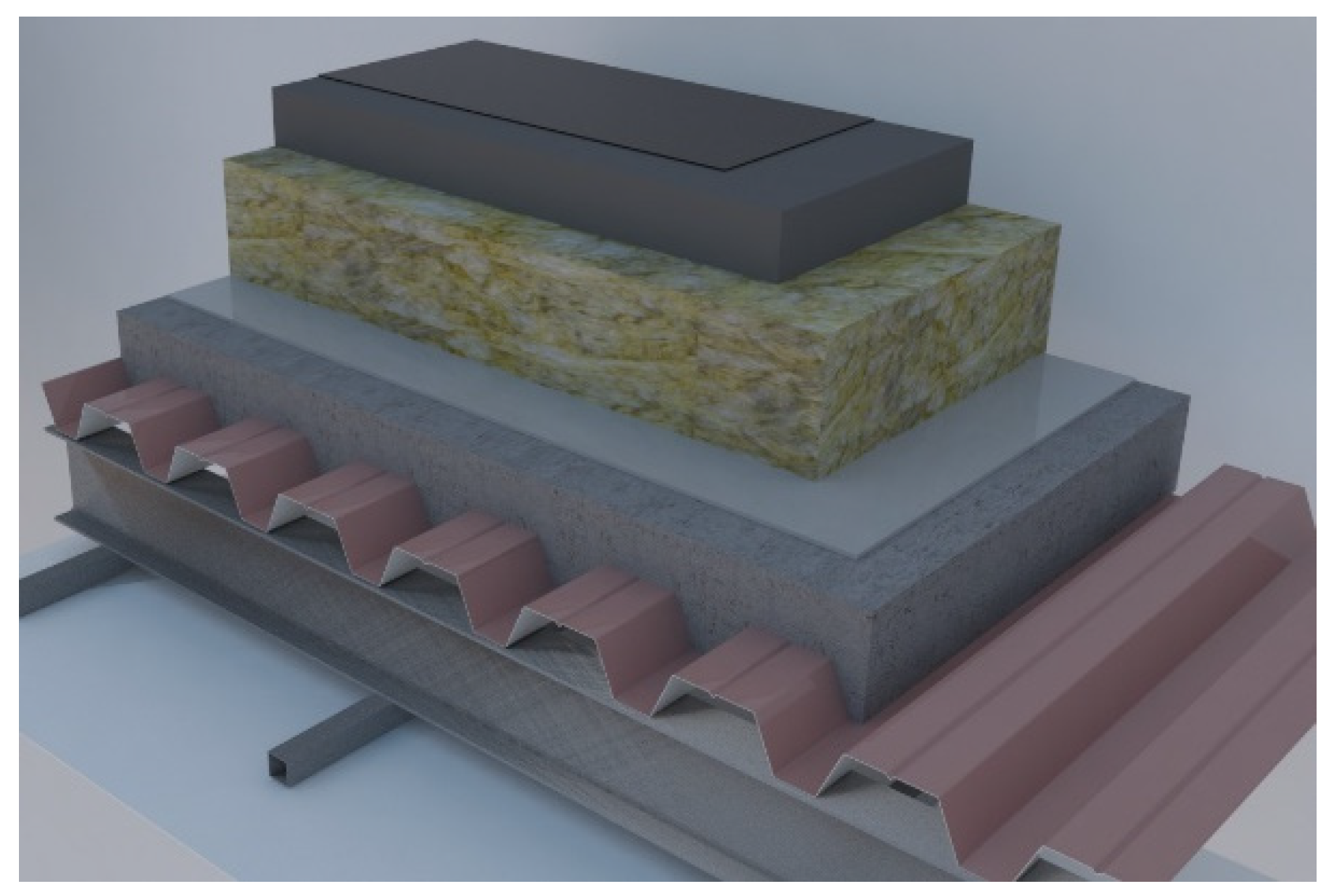

- The intermediate slab has steel structure IPE 330 and IPE 220, secondary profiles IPE220, is structured, proceeding towards each other in the slab stratigraphy, by 1.5mm thick corrugated metal sheet, structural screed with 12.5cm electro welded mesh, 10cm rock wool insulation layer, 5cm bedding screed and 1.5cm terracotta flooring. At the soffit, a lightweight metal structure for gypsum-fiber panelling ceiling.

- -

- The roofing has dry stratigraphy, with steel structure, IPE330 and IPE220 profiles, IPE220 secondary profiles, on which 1.5mm corrugated metal sheet rests, followed by screed with 12.5cm electro welded mesh, a 0.5mm PVC waterproofing sheet, a 16cm rock wool layer, EPS layer, and finally to close a 3mm waterproofing sheathing. As a finish on the soffit there is a light metal structure for false ceiling in gypsum-fiber panelling (Figure 13).

4.4. Design Solution No. 2: Demolition + Construction

5. Application to Case Study

5.1. Design Solution No. 1

5.1.1. Scenario C1—Starting Situation (Baseline)

5.1.2. Scenario C2—Adoption of Secondary Raw Materials

5.1.3. Scenario C3—Alternative Technological Solutions

- -

- Replacement of insulation material with one with low CO2e emissions; rock wool is replaced with a wood fiber panel.

- -

- Replacement of inter-floor floor construction technology; the present stratigraphy (floor with a “wet” system) is replaced with a “dry” technology (Figure 17).

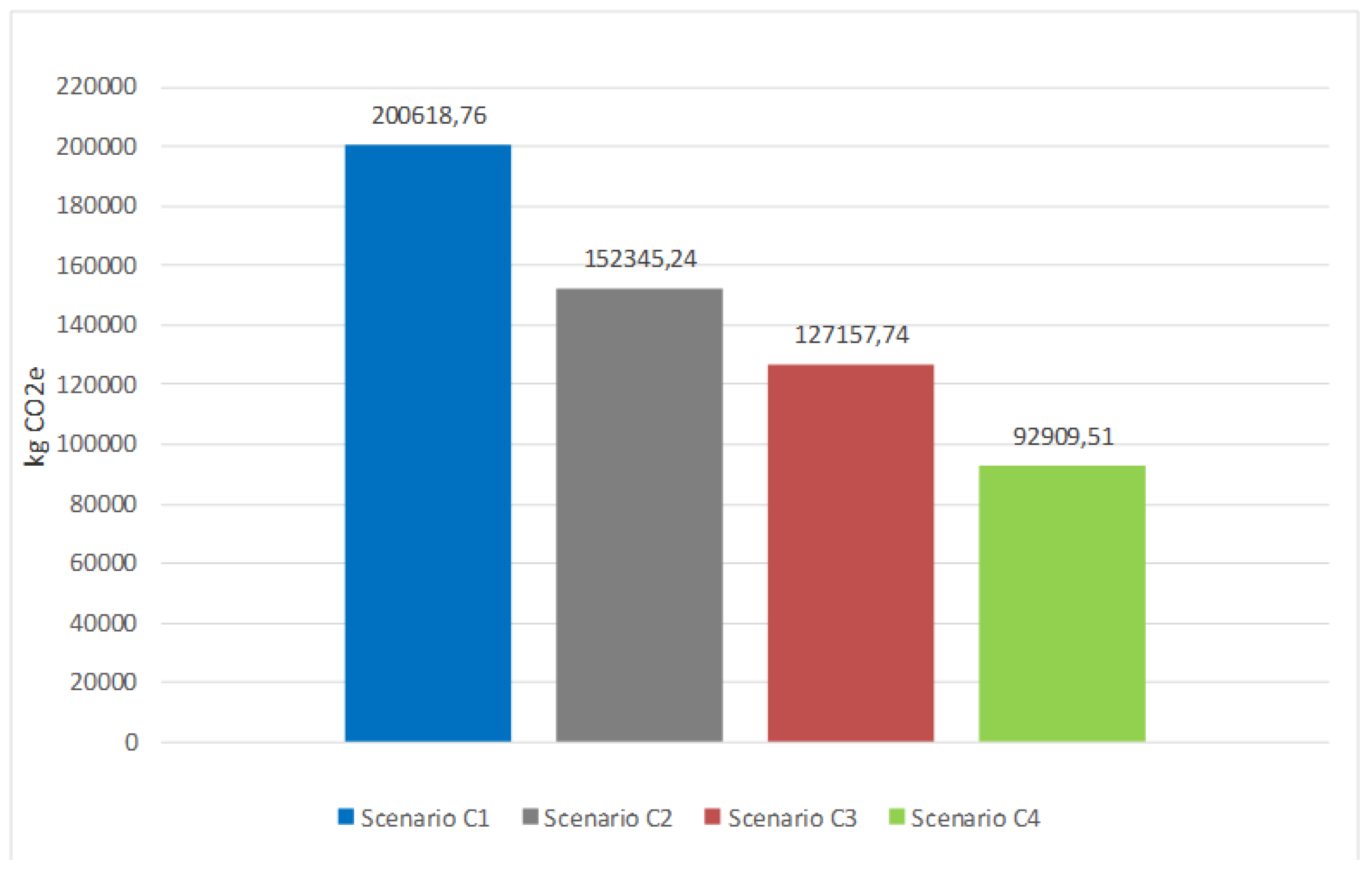

5.2. Design Solution No. 2

5.2.1. Demolition

5.2.2. Scenario D1—Reuse

5.2.3. Scenario D2—Recycling

5.2.4. Scenario D3—Disposal

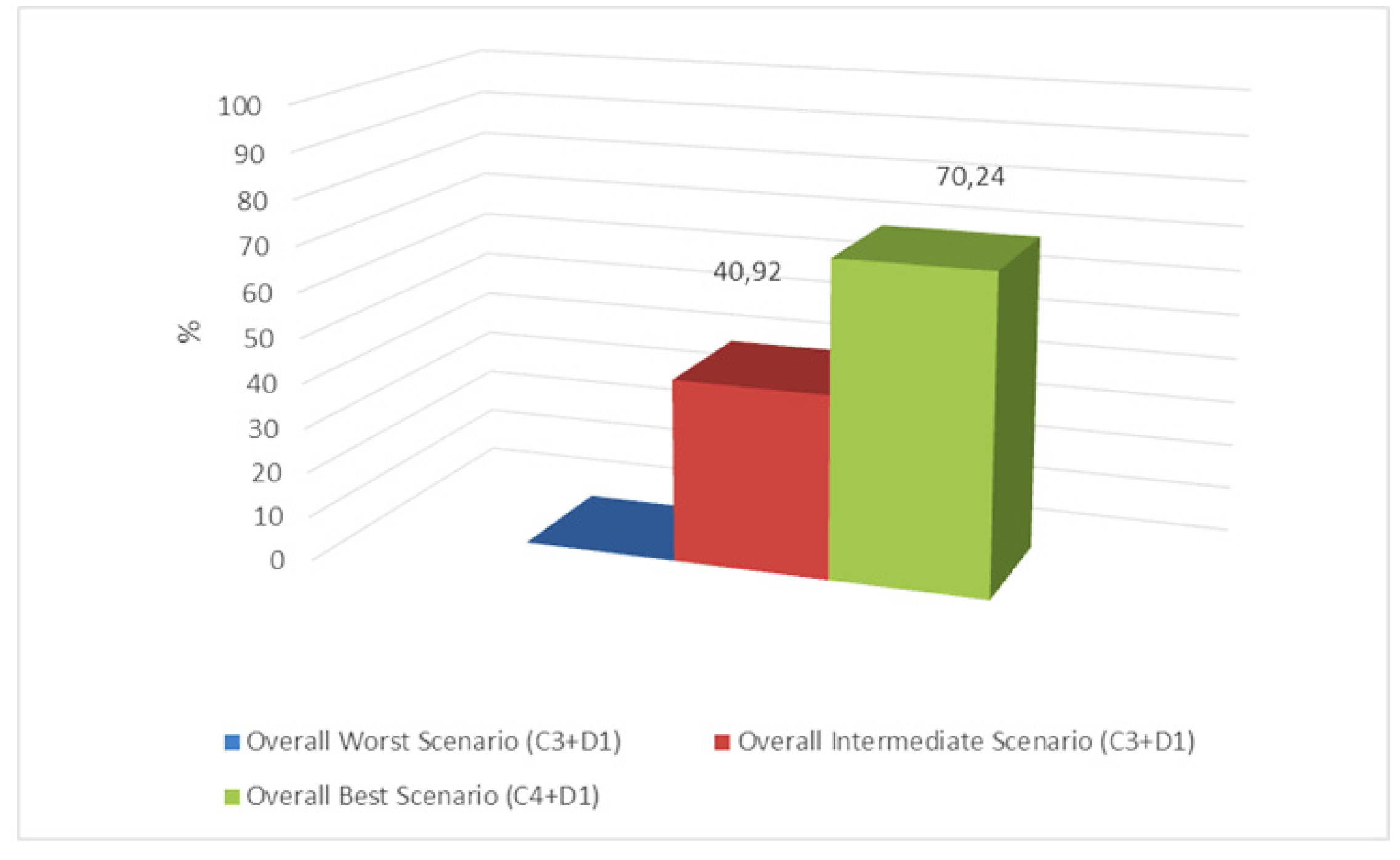

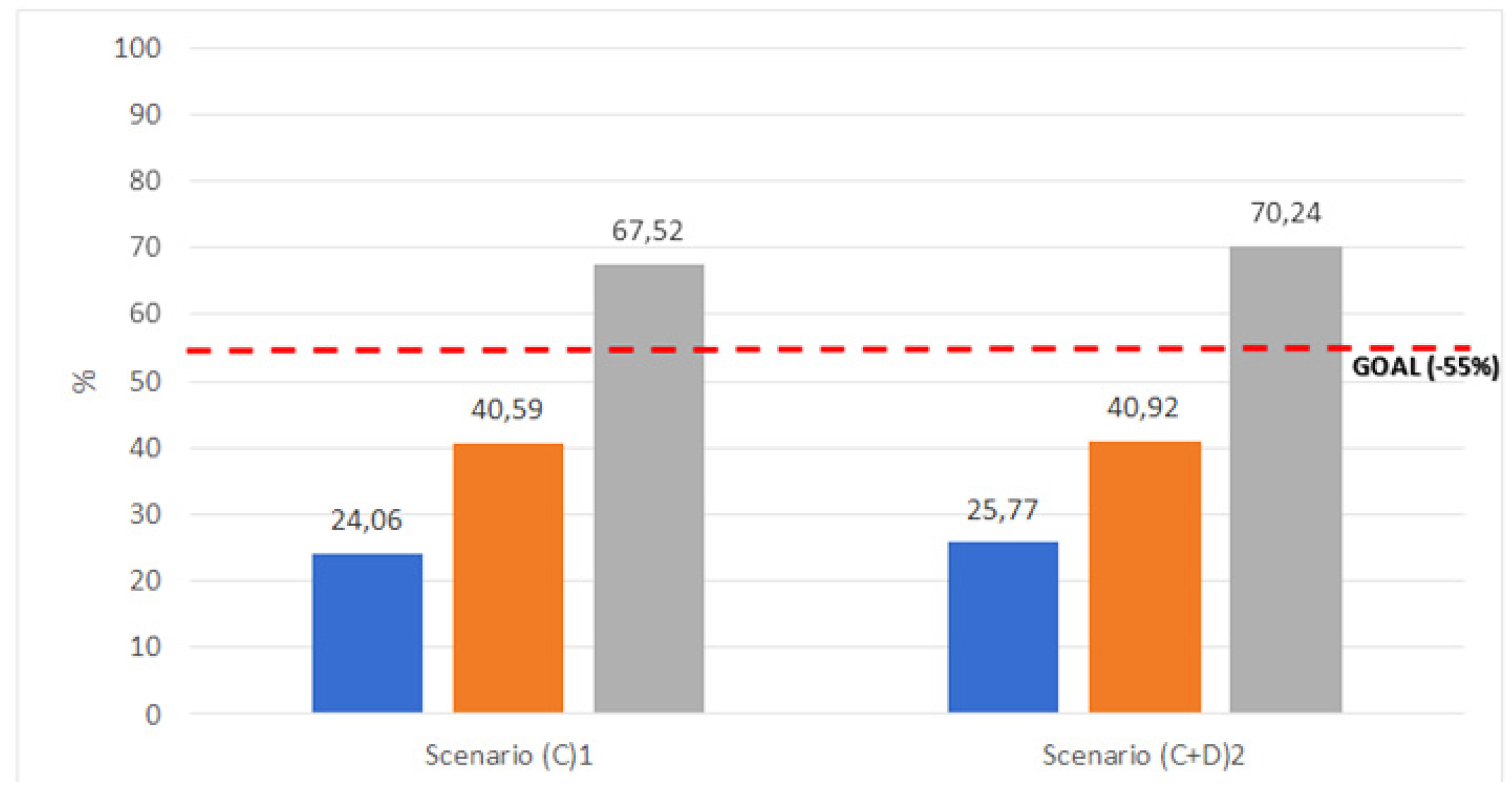

6. Results and Discussions

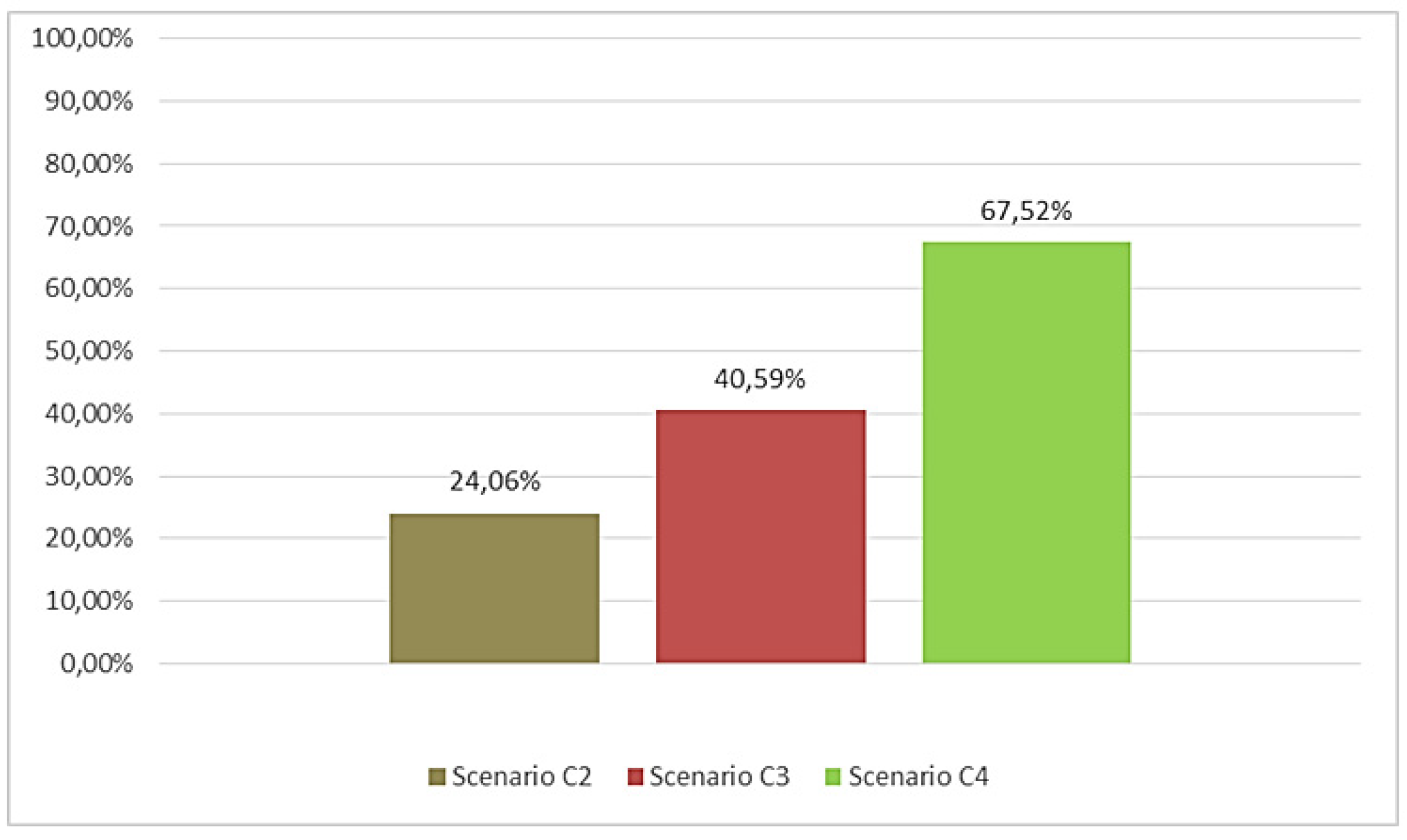

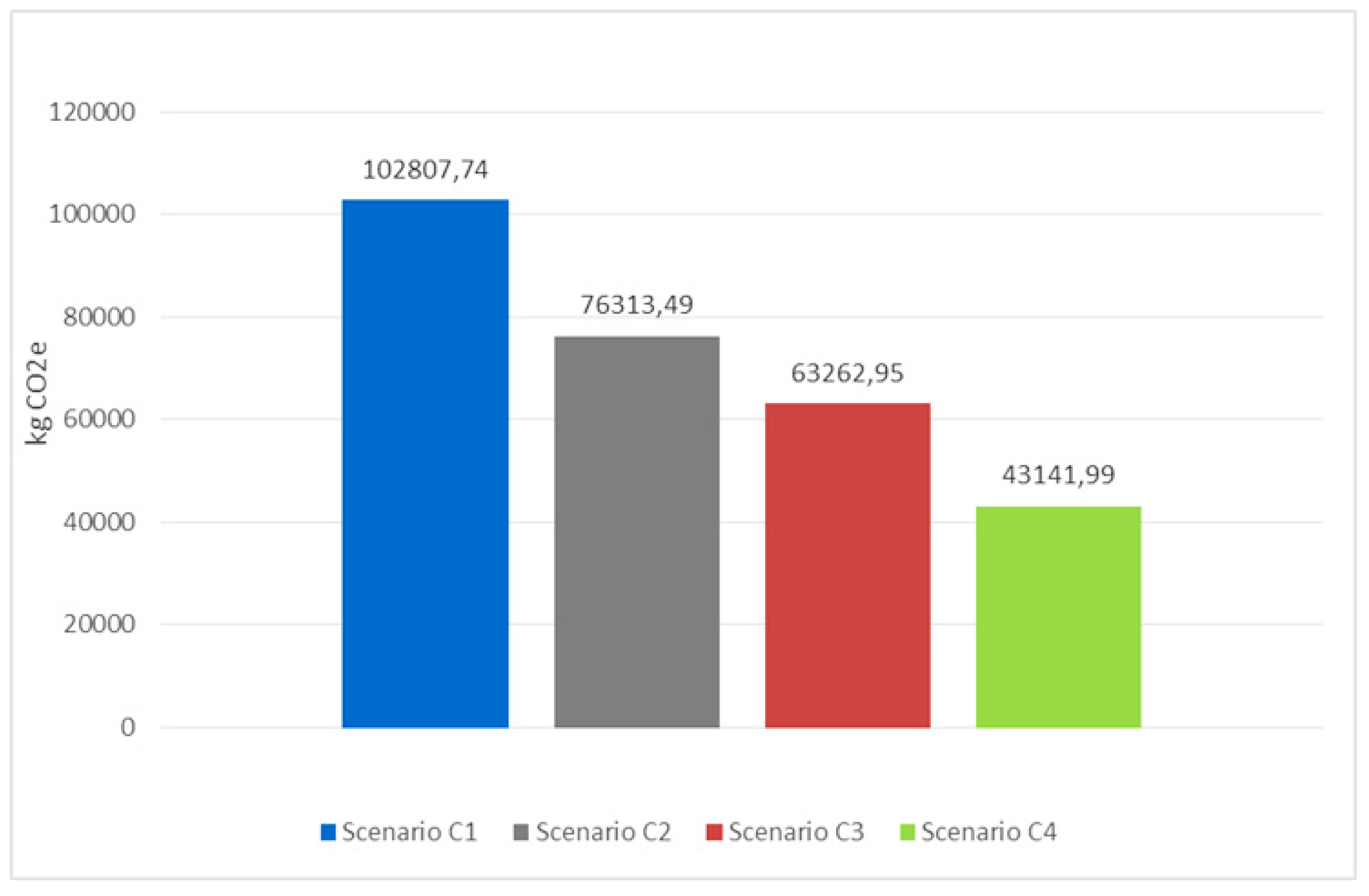

6.1. Results of Design Solution No.1

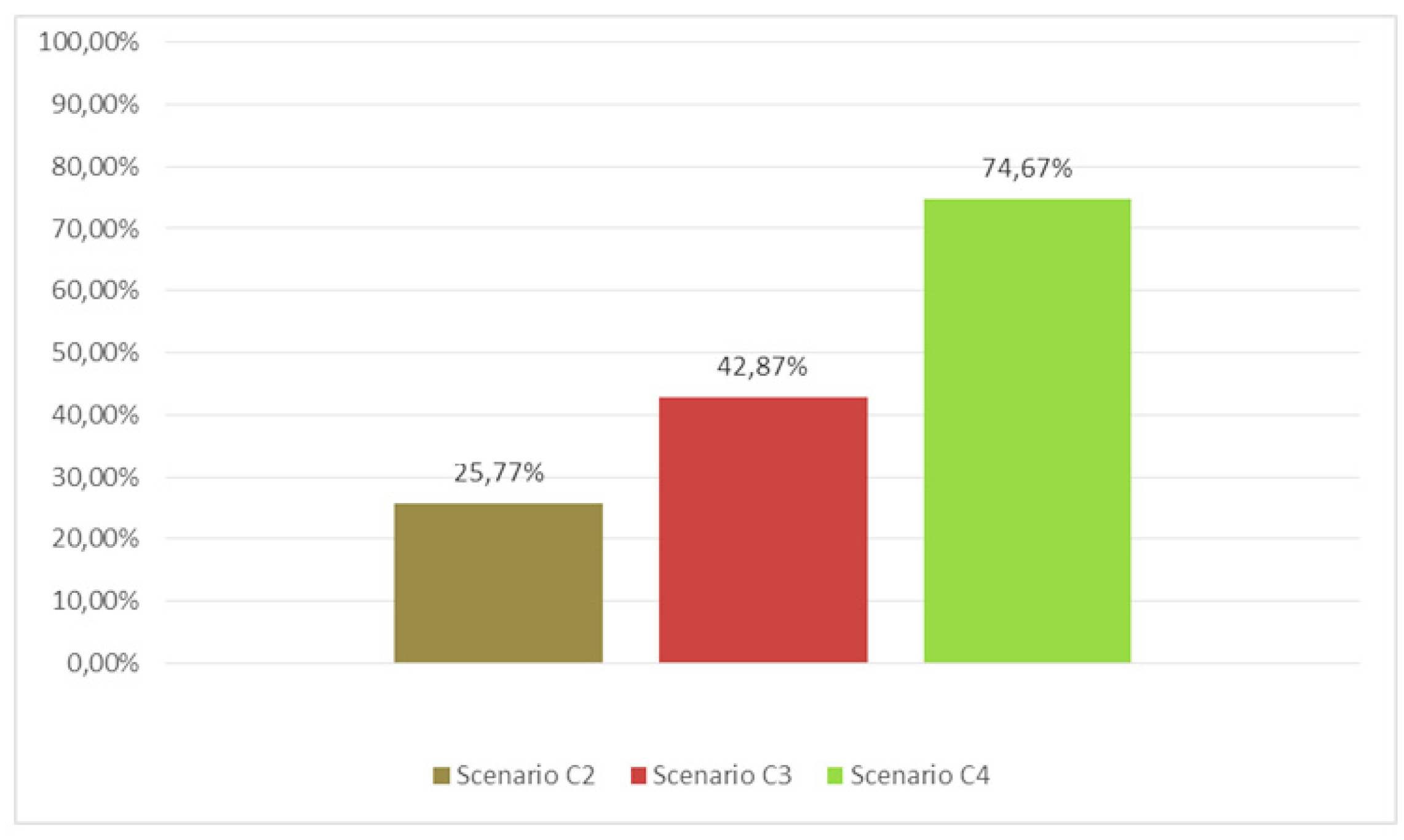

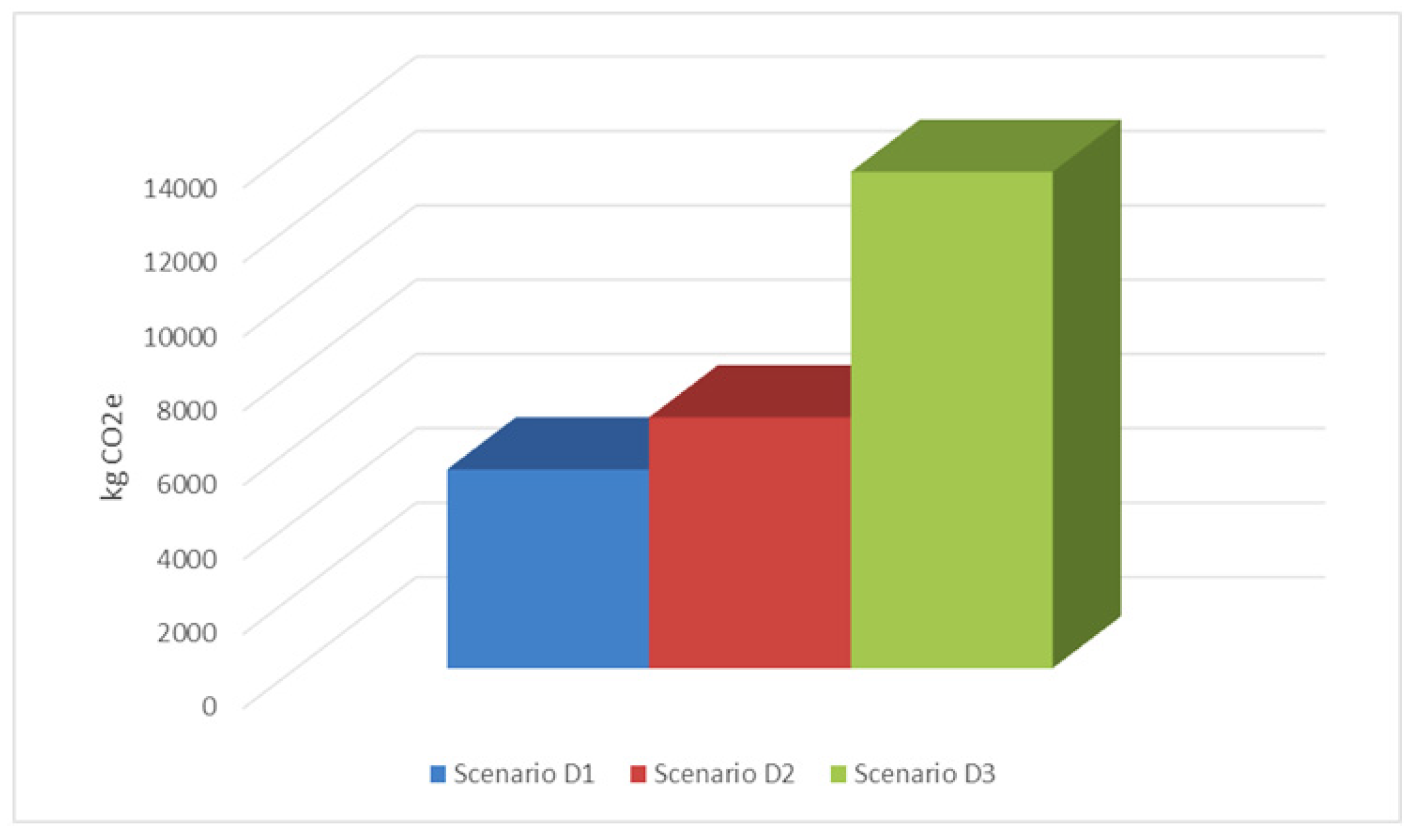

6.2. Results of Design Solution No.2

7. Conclusions

References

- Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2023_231_R_0001&qid=1695186598766.

- Alessi, A. Riguadagnare lo Spazio, in Materialegno 4, Lo Spazio Ritrovato, Milano, 2011.

- Daglio, L. Nuovo Suolo: Riuso e Recupero Delle Superfici in Quota Degli Edifici in, “Costruire nel Costruito. Architettura a Volume Zero”, collana Architettura e Città. Argomenti di Architettura, Milano, 2012. Available online: https://re.public.polimi.it/handle/11311/692634#.WE7i-rLhCR0.

- Reale, L. Densità, Città, Residenza. Tecniche di Densificazione e Strategie Anti-Sprawl. Gangemi Editore, Roma, 2008.

- Ferrante, A.; Cattani, E.; Bartolini, N.; Semprini, G. La Riqualificazione Energetica e Architettonica del Patrimonio Edilizio Recente, in Ricerche e Progetti per il Territorio, la Città e L’architettura, no. 5 Dicembre, 2012.

- Spagnolo, R. La Rigenerazione Urbana Come Problema di Ri-Composizione Architettonica, in Marta Calzolaretti, Domizia Mandolesi (a cura di), Rigenerare Tor Bella Monaca, Macerata, 2014; p. 83.

- Calzolaretti, M. Perché Tor Bella Monaca. Il Programma di Ricerca, in Marta Calzolaretti, Domizia Mandolesi (a cura di), Rigenerare Tor Bella Monaca, Macerata, 2014; p. 17.

- Sicignano, E. La Demolizione Quale Esorcismo del Male Sociale: Il Caso delle Vele di Scampia a Napoli, in Rita Maria Borboni, Città&Criminalità, Pesaro, 2005; pp. 233–241.

- Valente, I. Consolidare e Ri-Misurare i Margini Urbani: Una Ricerca Progettuale per Tor Bella Monaca, in Marta Calzolaretti, Domizia Mandolesi (a cura di), Rigenerare Tor Bella Monaca, Macerata, 2014; p. 86.

- Valente, I. Consolidare e Ri-Misurare i Margini Urbani: Una Ricerca Progettuale per Tor Bella Monaca, in Marta Calzolaretti, Domizia Mandolesi (a cura di), Rigenerare Tor Bella Monaca, Macerata, 2010; p. 88.

- Portoghesi, P. In Materia n.44-45, Milano, 2012; pp. 35–39.

- Wien, Gasometer D, Wilhelm Holzbauer, Blick aus Einer Dachwohnung. 2001. Available online: https://www.alamy.com/wien-gasometer-d-wilhelm-holzbauer-2001-blick-aus-einer-dachwohnung-image221171876.html.

- Caruso, M.C.; Menna, C.; Asprone, D.; Prota, A. Methodology for Life-Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Building Structures. ACI Struct. J. 2017, 114, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embodied Carbon—The ICE Database. Available online: https://circularecology.com/embodied-carbon-footprint-database.html.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).