Submitted:

28 March 2024

Posted:

28 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

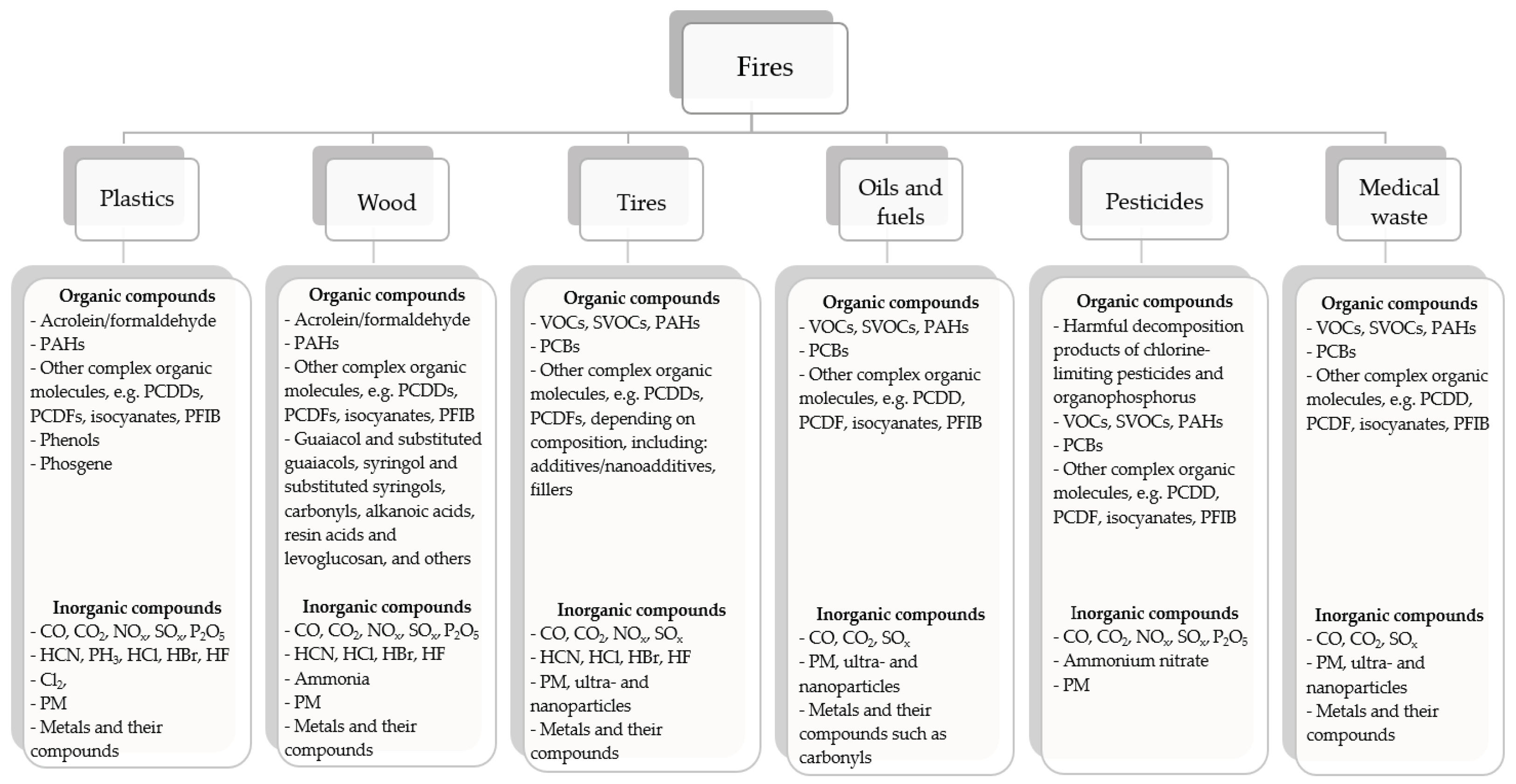

1. Introduction

- −

- type 1 - for outdoor operation, including operation in a forest fire environment, no puncture protection and finger protection, no protection against chemical hazards,

- −

- type 2 - for rescue and fire-fighting activities, puncture protection and finger protection, no protection against chemical hazards,

- −

- type 3 - for all types of activities, puncture protection, finger protection and protection against chemical agents.

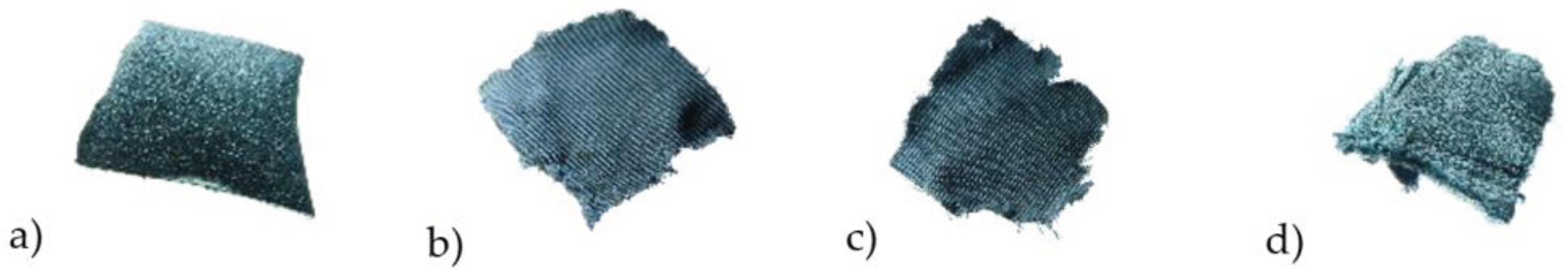

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Equipment

- Outer layer – 99 % aramid fiber and 1 % antistatic fiber

- Middle layer - aramid fibers (65 %) covered with a polyethylene film (35 %)

- Inner layer - two-layer lining; first viscose layer (50 %) second aramid layer (50 %).

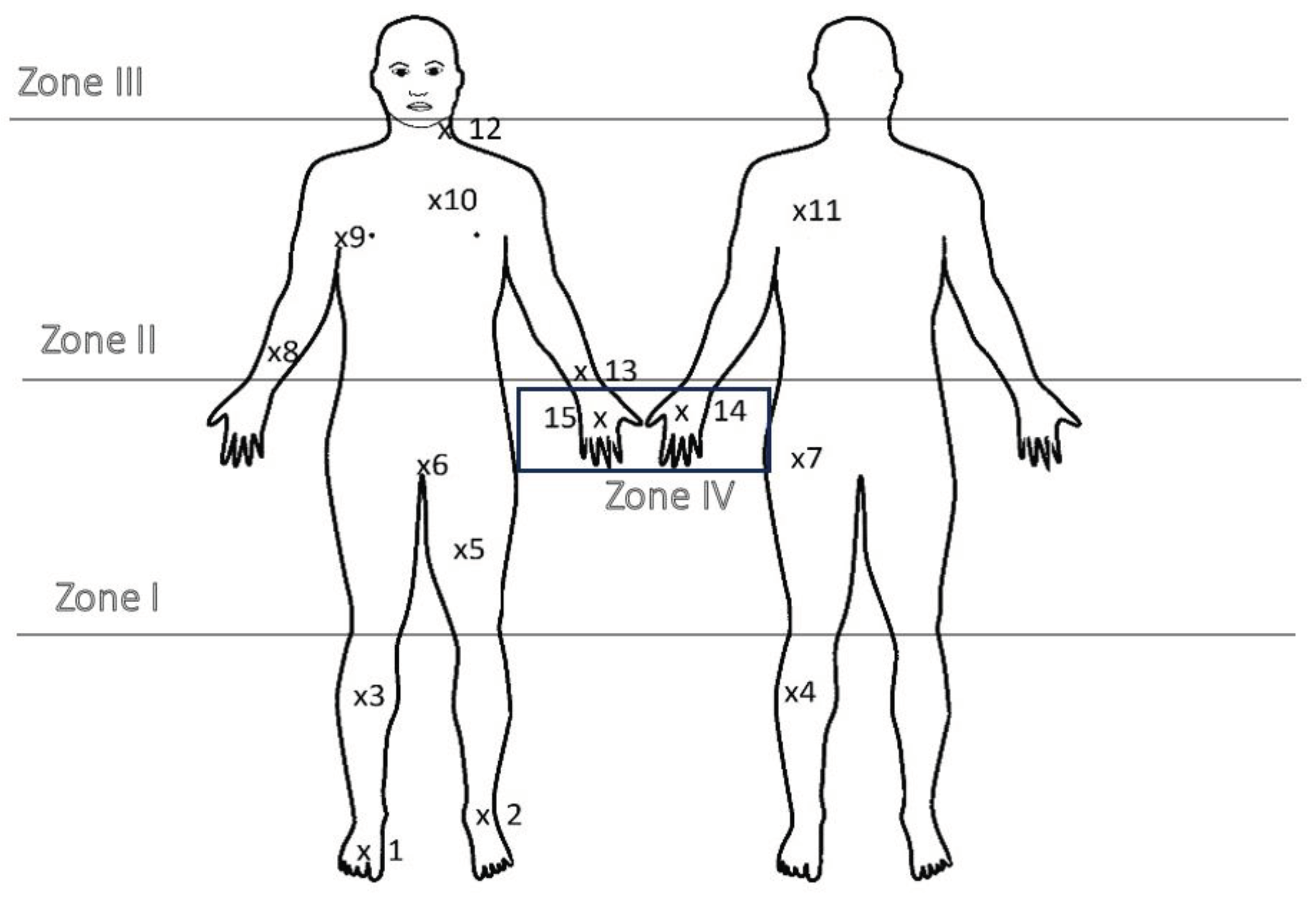

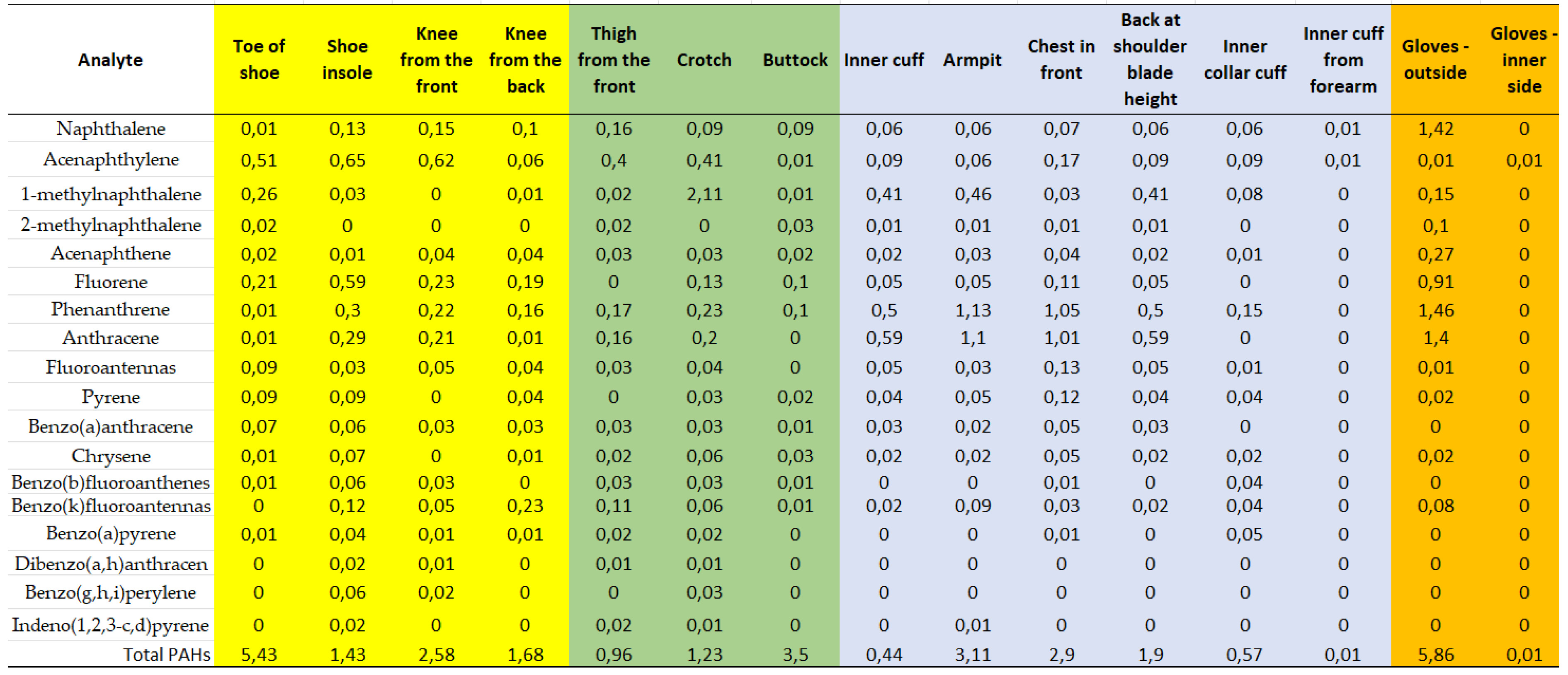

2.2. Sampling Methodology

- -

- zone I – shoes, i.e. from the ground to the knees,

- -

- zone II – trousers, i.e. from the knees to the waist,

- -

- zone III – sweatshirt, i.e. from the waist to the neck,

- -

- zone IV – gloves.

2.3. Preparation of the Standard Curve

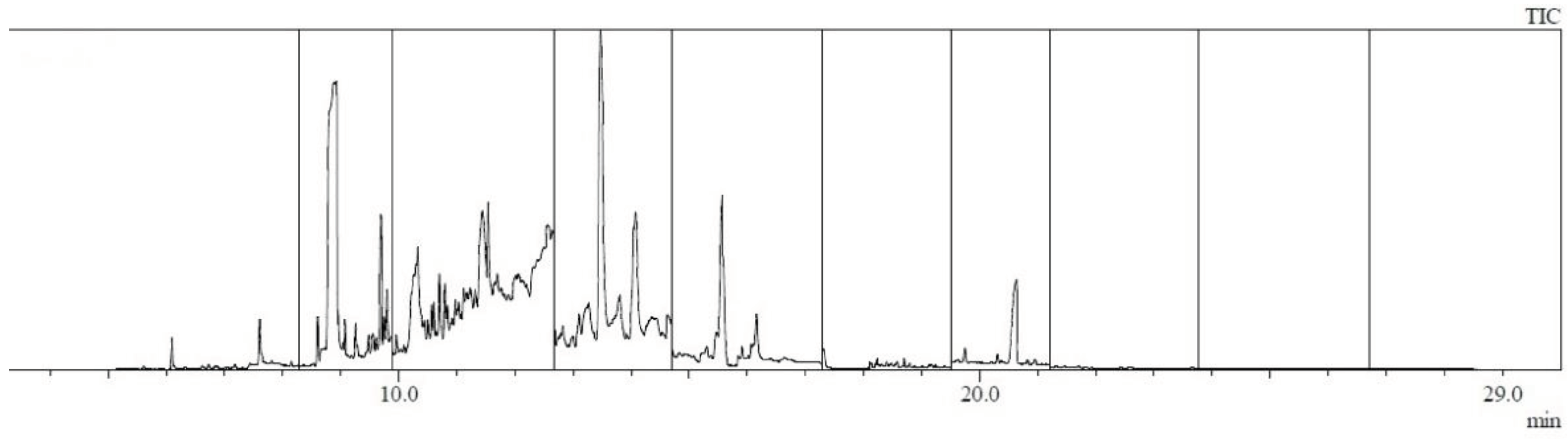

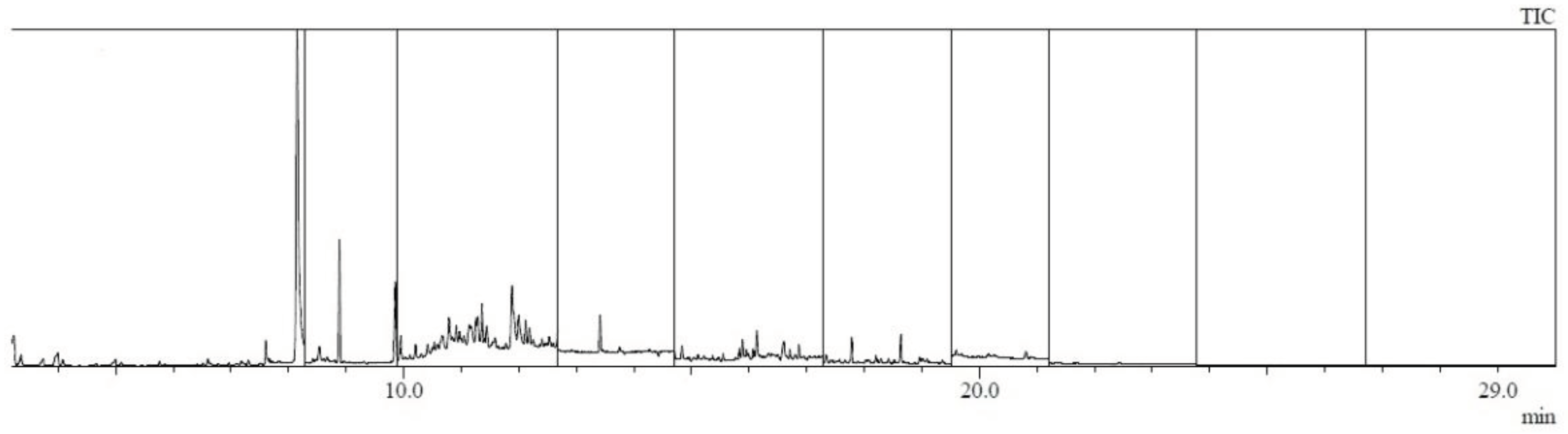

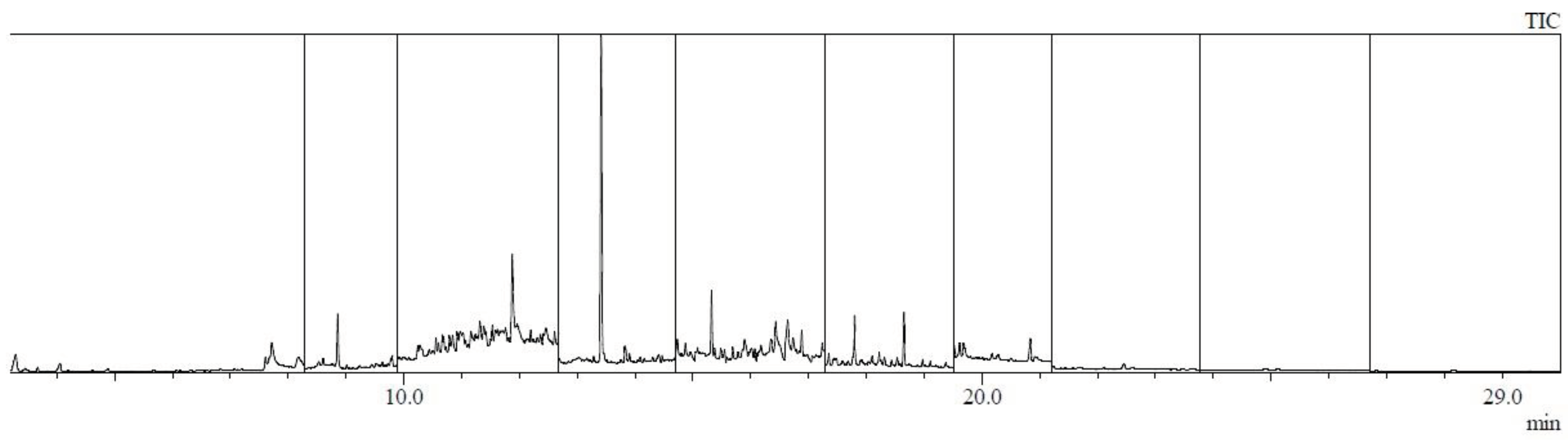

2.4. Chromatographic Analysis with Thermodesorption

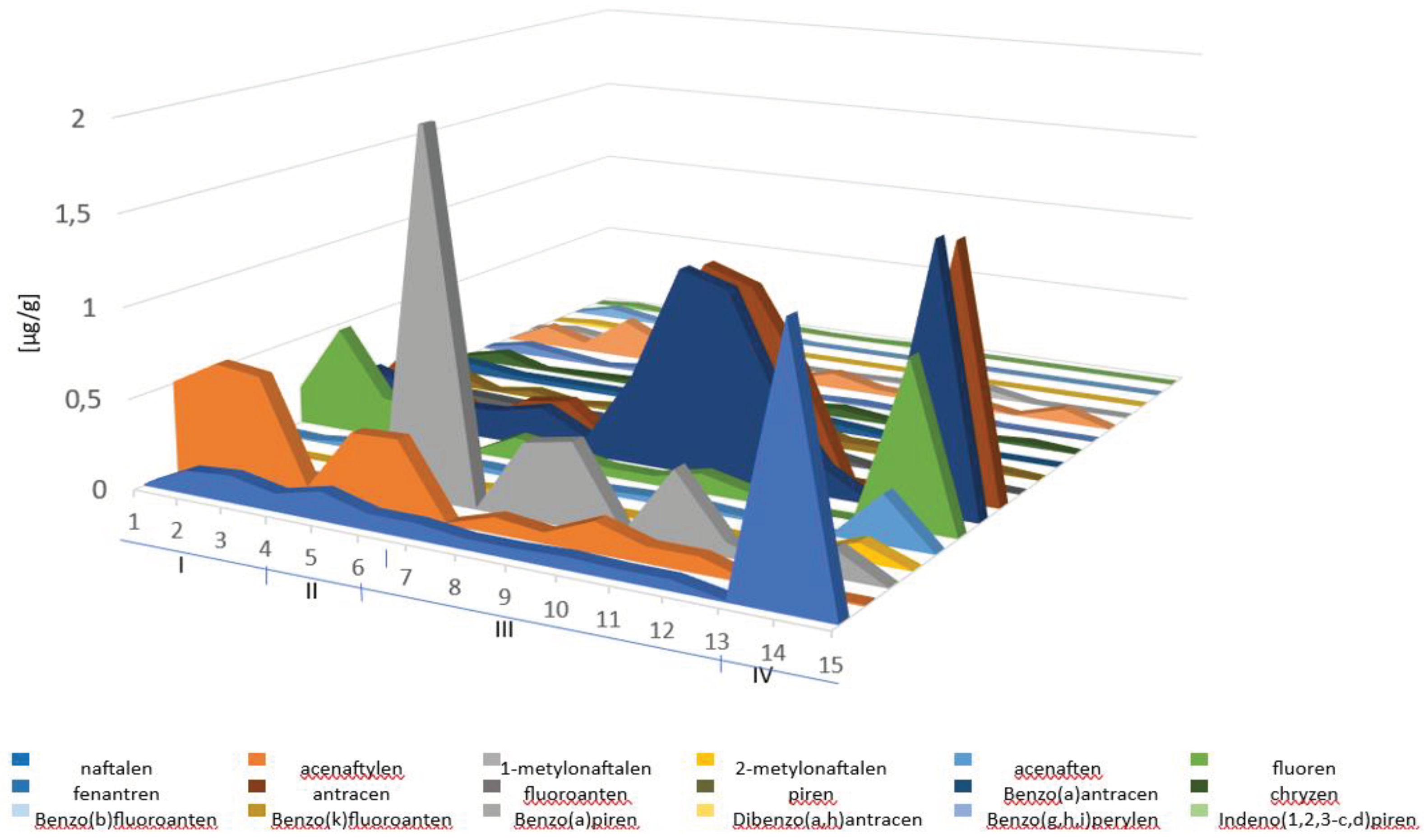

3. Results

4. Discussion

- -

- jacket and trousers – 99 % aramid fiber and 1 % antistatic fiber (outer layer), 65 % aramid fiber covered with a polyethylene film (35 %) (middle layer), two-layer lining, including the first viscose layer (50 %) and the second aramid layer (50 %) (internal layer),

- -

- shoes - rubber, cotton lining, steel toe,

- -

- firefighter's gloves - full-grain cowhide, protected with HIPORA polyurethane membrane, inner insert made of KEVLAR fibers.

5. Conclusions

- -

- shoes and gloves are the most contaminated, which is influenced by the type of materials from which these items of clothing are made and the zone of their use,

- -

- in the case of aramid fiber from which the jacket and trousers were made, the distribution of individual compounds is not equal throughout the material and is a consequence of the height of sampling,

- -

- the highest amounts of PAHs in the jacket and trousers were found in samples taken from the buttock and armpit, while the lowest were found in samples from the front thigh and inner cuff from the forearm, respectively,

- -

- both the type of material and the zone in which the clothing items are used are important for the total amount of PAHs and the presence and amount of individual compounds from the PAH group.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandal, S.; Camenzind, M.; Annaheim, S.; Rossi, R. M. Firefighters' protective clothing and equipment. In G. Song & F. Wang (Eds.), Firefighters' clothing and equipment: performance, protection, and comfort, CRC Press. 2019, pp. 31–59.

- EFFIS Statistics Portal: https://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/apps/effis.statistics/ (access: 13.02. 2024.

- Statistical data of the Headquarters of the State Fire Service, Poland, www.kgpsp.gov.pl (access:: 05.02. 2024.

- National Centers for Environmental Information. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/ (access: 22.02. 2024.

- Dickinson, G.N.; Miller, D.D.; Bajracharya, A.; Bruchard, W.; Durbin, T.A.; McGaryy J., K.P.; Moser E., P.; Nuñez, L.A.; Pukkila E., J.; Scott, P.S.; Sutton, P.J.; Johnston, N.A. C Health Risk Implications of Voltaile Organic Compounds in Wildfire Smoke During the 2019 FIREX-AQ Campaign and Beyond. GeoHealth, 2022; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefiled, J.C. A toxicological Rewiev of the Products of Combustion, Health Protection Agency. 2010. 9: ISBN, 8595. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, J. B.; Lerner, B. M.; Kuster, W. C.; Goldan, P. D.; Warneke, C.; Veres, P. R. , et al. Biomass burning emissions and potential air quality impacts of volatile organic compounds and other trace gases from fuels common in the US. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 13915–13938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huey, L. G.; Yokelson, R. J.; Selimovic, V.; Simpson, I. J.; Müller, M. , Jimenez, J.L.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Beuersdorf, A.J.; Blake, D.R.; Butterfield, Z.; Choi, Y.; Crounse J.D.; Day, D.A.; Diskin, G.S.; Dubey, M.K.; Fortnrt, E.; Hanisco, T.F.; Hu, W.; King, L.E; Kleinman L.; Meinardi, S.; Mikoviny, T.; Onasch, T.B.; Palm, B.B.; Peischl, J.; Pollack, I.B.; Ryerson T.B.; Sachse G.W.; Sedlacek, A.J.; Shilling, J.E.; Springston, S.; M.St. Clair, J.; Tanner, D.J.; Teng, A.P., Wennberg, P.O.; Wisthaler, A.; Wolfe, G.M. Airborne measurements of Western U.S. wildfire emissions: Comparison with prescribed burning and air quality implications. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 6108–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, J. J.; Kleeman, M. J.; Cass, G. R.; Simoneit, B. T. Measurement of Emissions from Air Pollution Sources. 3. C1-C29 Organic Compounds from Fireplace Combustion of Wood. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanski, S. P.; Hao, W. M.; & Baker, S.; & Baker, S. Chapter 4 Chemical Composition of Wildland Fire Emissions. Developments in Environmental Science 2008, 8, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Miller, D.; Scheuer, E.; Dibb, J.; Selimovic, V.; Yokelson, R.; Zarzana, K.J.; Brown, S.S.; Koss, A.R.; Warneke, C.; Hasstings, M. Isotopic characterization of nitrogen oxides (NOx), nitrous acid (HONO), and nitrate (pNO3-) from laboratory biomass burning during FIREX. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 6303–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D. A.; O’Neill, S. M.; Larkin, N. K.; Holder, A. L.; Peterson, D. L.; Halofsky, J. E.; Rappold, A. G. Wildfire and prescribed burning impacts on air quality in the United States. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 583–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, I. J.; Akagi, S. K.; Barletta, B.; Blake, N. J.; Choi, Y.; Diskin, G. S.; Fried, A.; Fuelberg, H. E.; Meinardi, S.; Rowland, F. S.; Vay, S. A.; Weinheimer, A. J.; Wennberg, P. O.; Wiebring, P.; Wisthaler, A; Yang, M. ; Yokelson, R. J.; Blake, D. R. Boreal forest fire emissions in fresh Canadian smoke plumes: C1-C10 volatile organic compounds (VOCs), CO2, CO, NO2, NO, HCN and CH3CN. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 6445–6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleknia, S.D.; Adams, M.A. Implications for Agriculture Impact of volatile organic compounds from wildfires on crop production and quality. In: Aspects of Applied Biology, 88. Effects of Climate Change on Plants: Implications for Agriculture, Published by the Association of Applied Biologists, The Warwick Enterprise Park, Wellesbourne, Warwick CV35 9EF, UK. 2008.

- Sekimoto, K.; Koss, A. R.; Gilman, J. B.; Selimovic, V.; Coggon, M. M.; Zarzana, K. J.; Yuan, B.; Lerner, B.M.; Brown, S.S.; Warneke, C.; Yokelson, R.J.; Roberts, J.M.; deGouw, J. High-and low-temperature pyrolysis profiles describe volatile organic compound emissions from western US wildfire fuels. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 9263–9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, G. R.; Aklilu, Y.; Landis, M. S.; Hsu, Y. M. Impacts of a large boreal wildfire on ground level atmospheric concentrations of PAHs, VOCs and ozone. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 178, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Samet, J. M.; Bromberg, P. A.; Tong, H. Cardiovascular health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Part Fibre Toxicol 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikerwal, A.; Akram, M.; Monaco, A. D.; Smith, K.; Sim, M. R.; Meyer, M.; Tonkin, A.M.; Abramson, M.J.; Dennekamp, M. Impact of Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Exposure During Wildfires on Cardiovascular Health Outcomes. JAHA 2015, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichenthal, S.; Kulka, R.; Lavigne, E.; vanRijswijk, D.; Brauer, M.; Villeneuve, P. J.; Stieb, D.; Joseph, L.; Burnett, R.T. Biomass Burning as a Source of Ambient Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Acute Myocardial Infarction. Epidem. 2017, 28, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. EPA. 2021. Integrated risk assessment system. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/iris (access: 13.02 2024).

- NCBI -National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2021. PubChem compound summary for CID 7500, ethylbenzene. Retrieved from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ethylbenzene (access: 13.02 2024).

- IPCS INCHEM http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc202.htm (access: 18.03 2024).

- Sogbanmu, T.O.; Nagy, E.; Phillips, D.H.; Arlt, V.M.; Otitoloju, A.A.; Bury, N.R. Lagos lagoon sediment organic extracts and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons induce embryotoxic, teratogenic and genotoxic effects in Danio rerio (zebrafish) embryos. Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2016, 23, 14489–14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.A. The genotoxicity of priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in complex mixtures. MRGTEM 2002, 515, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roguski, J.; Stegienko, K.; Kubis, D.; Błogowski, M. Comparsion of Requirements and Directions of Development of Methods for Testing Protective Clothing for Firefighting. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2016, 24, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolański, R.; Rabajczyk, A. Analysis of the Issue of Special Clothing in the Operation of Fire Protection Units. 2022, 60, 64–85. [CrossRef]

- Wolański, R.; Rabajczyk, A. Selected Aspects of Transformation of Textile Elements of Firemen's Personal Protection. 2023, 61, 86–101. [CrossRef]

- EN 469:2020. Protective clothing for firefighters – Performance requirements for protective clothing for firefighting. ICS 13.340.10. European Committee for Standardization, Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium.

- EN 469:2005. Protective clothing for firefighters – Performance requirements for protective clothing for firefighting. ICS 13.340.10. European Committee for Standardization, Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium.

- Krzemińska, S.; Szewczyńska, M. Analysis and Assessment of Hazards Caused by Chemicals Contaminating Selected Items of Firefighter Personal Protective Equipment-a Literature Review, SFT 2020, 56, 2. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J-Y. ; Yamamoto, Y.; Oe, R., Son, S-Y., Wakabayashi, H., Tochihara, Y. The European, Japanese and US protective helmet, gloves and boots for firefighters: thermoregulatory and psychological evaluations. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, R.; Houshyar, S.; Padhye, R. Recent trends and future scope in the protection and comfort of fire-fighters’ personal protective clothing. Fire Sci Rev 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15090:2012 Footwear for firefighters. ICS 13.340.50. European Committee for Standardization, Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium.

- Garner, J.; Wade, C.; Garten, R.; Chander, H.; Acevedo, E. The influence of firefighter boot type on balance. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2013, 43, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.I. Organic Preparation. Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, Warsaw, Poland. 2018, pp. 1523.

- Kirk, K.M.; Logan, M.B. Firefighting Instructors’ Exposures to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons During Live Fire Training Scenarios. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, A.A.; Dickens, K. E.; Salden, M.; Hewitt, F.E.; Watts, D.P.; Houldsworth, P.E.; Martin, F.L. Occupational Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Elevated Cancer Incidence in Firefighters. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzeminska, S.M.; Szewczyńska, M. Hazard of chemical substances contamination of protective clothing for firefighters – a survey on use and maintenance, OEM 2022, 2, 35. 2. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H. Ara Jahan S., Kabir E., Brown R.J.C. A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects. Environment International 2013, 60, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, S. Global atmospheric emission inventory of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) for 2004. Atmos Environ 2009, 43, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.S.; Brown, R.J.C. Correlations in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) concentrations in UK ambient air and implications for source apportionment. J Environ Monit 2012, 14, 2072–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possanzini, M.; Di Palo, V.; Gigliucci, P.; Tomasi Sciano, M.C. , Cecinato, A. Determination of phase-distributed PAH in Rome ambient air by denuder/GC-MS method. Atmos Environ 2004, 38, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzemińska, S.; Szewczyńska, M. Analysis and Assessment of Hazards Caused by Chemicals Contaminating Selected Items of Firefighter Personal Protective Equipment – a Literature Review, SFT 2020, 56, 92 – 109. 56. [CrossRef]

- Stec, A.; Wolffe, T.; Clinton, A. Minimising firefighters’ exposure to toxic fire effluents. Interim Best Practice Report, University of Central Lancashire, Fire Brigades Union (FBU), 2020. https://www.ctif.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/FBU%20UCLan%20Contaminants%20Interim%20Best%20Practice%20gb.pdf (access: 14.01. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fent, K.W.; Toennis, C.; Sammons, D.; Robertson, S.; Bertke, S.; Calafat, A.M.; Pleil, J.D.; Wallace, M.A.G.; Kerber, S.; Smith, D.L.; Horn, G.P. Firefighters’ and instructors’ absorption of PAHs and benzene during training exercises. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2019, 222, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, B.; Hu, S.; Xue, G.; Xia, J. Contamination and removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in multilayered assemblies of firefighting protective clothing. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, O.; Kursun Bahadir, S.; Kalaoglu, F. An analysis on the moisture and thermal protective performance of firefighter clothing based on different layer combinations and effect of washing on heat protection and vapour transfer performance. Adv Mat Sci Eng 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingli, X.; Shuhu, L.; Jianfen, G.; Haiyan, Z.; Jianqin, Z.; Haiyun, Z.; Danyong, W.; Yiwei, C. Properties of Aramid Fibers And Their Composites Based on Atomic/Molecular Scale Simulation Technology: A Review. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2478 2023, 042008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Wang, F. Firefighters’ clothing and equipment: performance, protection, and comfort. Taylor & Francis Group, CRC Press 2018, pp. 372. [CrossRef]

- Clawson, J.K. , Structure and defects in high-performance aramid fibers. Thesis. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/19530021.pdf (access: 15.03. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Denchev, Z.; Dencheva, N. Manufacturing and Properties of Aramid Reinforced Composites. In: Synthetic Polymer-Polymer Composites. Bhattacharyya D., Fakirov S. 2012. Chapter 8, pp. 251–280. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Kawai, H. Moisture Sorption Mechanism of Aromatic Polyamide Fibers: Diffusion of Moisture in Poly (p-phenylene Terephthalamide) Fibers 1. Textile Research Journal 1993, 63, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendal, A.; Almoaeen, R.A.; Rashad, M.; Husain, A.; Mouffouk, F.; Ahmad, Z. Aramid-wrapped CNT hybrid sol–gel sorbent for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 18077–18083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, K.; Chow, A. Extraction of phenols using polyurethane membrane. Talanta 1998, 46, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponangi, R.; Pintauro, P.N.; De Kee, D. Free volume analysis of organic vapor diffusion in polyurethane membranes. J Membr Sci 2000, 178, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=MR65188&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=773473180 (access: 11.02. 2024.

- The Risk Assessment Information System. https://rais.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/tools/TOX_search (access: 11.03. 2024.

- The International Association for Research and Testing in the Field of Textile and Leather Ecology https://www.oeko-tex.com/en/our-standards/oeko-tex-standard-100 (access: 11.02. 2024.

- https://www.oeko-tex.com/importedmedia/downloadfiles/STANDARD_100_by_OEKO-TEX_R__-Limit_Values_and_Individual_Substances_According_to_Appendices_4___5_en.pdf (access: 11.02. 2024.

- Regulation of the Minister of Family, Labor and Social Policy of June 12,, 2018 on the highest permissible concentrations and intensities of factors harmful to health in the work environment. Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland, Warsaw, July 3, 2018, item 1286 (Journal of Laws of June 12, 2018, item 1286, as amended) (in Polish).

- Blackie, S.P.; Fairbarn, M.S.; McElvaney, N.G.; Wilcox, P.G.; Morrison, N.J.; Pardy, R.L. Normal values and ranges for ventilation and breathing pattern at maximal exercise. Chest. 1991, 100, 136–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Table AC-1 PERISSIBLE EXPOSURE LIMITS FOR CHEMICAL CONTAMINANTS. https://www.dir.ca.gov/title8/5155table_ac1.html (access: 28.02. 2024.

| Analyte | Relative standard deviation RSD % |

Pearson correlation coefficient R |

|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | 3,05 | 0,9999 |

| Acenaphthylene | 7,75 | 0,9976 |

| 1-methylnaphthalene | 7,86 | 0,9999 |

| 2-methylnaphthalene | 2,15 | 0,9999 |

| Acenaphthene | 2,76 | 0,9998 |

| Fluorene | 3,66 | 0,9997 |

| Phenanthrene | 11,20 | 0,9996 |

| Anthracene | 4,66 | 0,9998 |

| Fluoroantennas | 5,85 | 0,9998 |

| Pyrene | 6,83 | 0,9997 |

| Benzo(a)anthracene | 9,67 | 0,9998 |

| Chrysene | 12,09 | 0,9996 |

| Benzo(b)fluoroanthenes | 11,76 | 0,9997 |

| Benzo(k)fluoroantennas | 7,61 | 0,9997 |

| Benzo(a)pyrene | 8,26 | 0,9996 |

| Dibenzo(a,h)anthracene | 10,82 | 0,9985 |

| Benzo(g,h,i)perylene | 23,50 | 0,9983 |

| Indeno(1,2,3-c,d)pyrene | 13,06 | 0,9965 |

| Thermodesorber operating parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Sample weight | 1-3 mg |

| Sample desorption temperature | 350 °C |

| Desorption time | 7 min |

| Carrier gas flow during tube desorption | 60 ml/min |

| Carrier gas flow during trap desorption | 1,0 ml/min |

| Trap temperature | - 20 °C |

| Trap desorption temperature | 350 °C |

| Desorption time | 3 min |

| Valve, transfer line and injection port temperatureMasa próbki | 300 °C |

| Working parameter | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Injection temperature | 300 °C |

| Splitless time | 1 min |

| Carrier gas | Helium 0,92 ml/min, constant flow, linear velocity 25,8 cm/s |

| Temperature | Isothermal program 60 °C for 1 min, then increase at a rate of 15 °C/min to 320 °C maintained for 12 min |

| Ion Source Temp. | 300 °C |

| Interface temp | 300 °C, |

| Detector voltage | 0,7 kV |

| Detector mode | SCAN 35-300 amu |

| Analyte | Average content in the sample [μg/g] |

Estimated content in whole clothes [μg] |

PEL [μg/m³] | Respirators Daily intake max [μg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naphthalene | 0,16 | 1155 | 100 | 4656 |

| Phenanthrene | 0,40 | 2797 | 8,88 | 413 |

| Anthracene | 0,37 | 2605 | 0,79 | 37 |

| Pyrene | 0,04 | 271 | 9,00 | 419 |

| Chrysene | 0,02 | 164 | 3,27 | 152 |

| Benzo(a)pyrene | 0,01 | 80 | 2,49 | 116 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).