1. Introduction

Mediterranean diet and of olive oil intake have been related in several studies with longevity and reduced risk of morbidity and mortality [

1]. Along with some other characteristics of the Mediterranean diet, olive oil is used as the main source of fat in Portugal and other Southern European countries. The main advantages of consuming olive oil were traditionally attributed to its high content in monounsaturated fatty acids [

2,

3]. However, it is now well established that these effects must also be ascribed to the presence of phenolic compounds with different biologic activities, that are probably interconnected, like antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial. For some activities of specific olive oil phenolic compounds, the evidence is already strong enough to enable the legal use of health claims [

4,

5,

6]. Moreover, some authors recommend that the inclusion of a label with the health claim based on olive oil polyphenols content would be useful to effectively signal both the “highest quality” and the “healthiest” extra virgin olive oils [

7]. The phenolic composition of virgin olive oil (VOO) can also give important information on its quality because phenols have important impact on organoleptic evaluation, since they are responsible for positive sensory attributes of bitterness and pungency [

8,

9,

10]

The fulfill of the health claim, that can only be declared if the “olive oil contains more than 5 mg of hydroxytyrosol and its derivatives per 20 g of oil”, is dependent on the characteristics of the extracted fruits. In fact, the presence of these specific phenolic compounds in contents that meet the requirements of the health claim is strongly dependent on olive cultivar, ripening, agronomic practices and geographical location, post-harvest, olive oil extraction and storage [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

However, fruit damage from pests and diseases can have a huge negative impact on olive oil quality, especially in sensory characteristics and acidity [

18,

19]. Olive fly

Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) (Diptera: Tephritidae), shows cultivar oviposition preference and is the cause of severe economic damages every year. This is the main pest attacking the fruits in olive orchards, as well as the most devastating insect pest in the Mediterranean region [

20,

21,

22]. The loss of quality caused by olive fruit fly is associated with the presence of fungi in the galleries made by the larvae. Anthracnose caused by

Colletotrichum spp. is the most damaging olive fruit disease in many countries, including Portugal [

23,

24]. In Portugal,

C. acutatum is restricted to the Algarve region (south), whereas

C. nymphaeae,

C. simmondsii, and

C. godetiae were prevalent in other olive-growing regions [

23]. These pathogens cause rot and drop of mature fruits, chlorosis and necrosis of leaves, and dieback of twigs and branches [

25]. Olive anthracnose epidemics are promoted by the autumn rainfall, high inoculum density, fruit ripeness, and depend on the susceptibility of host cultivars [

26]. Oil extracted from olives affected by

Colletotrichum spp. have off-flavors associated with musty defect and high acidity [

19,

24,

27]. Moreover, other compounds like phenols are also affected by the presence of anthracnose in the fruits [

19,

24,

28].

Olive anthracnose disease and olive fly, in a climate change context with increased unpredictability, namely concerning the occurrence of periods of high humidity and mild temperatures, are a concern for the sustainable management of olive cultivation, harvesting, and processing for producing high-quality EVOO [

19]. So, from the point of view of phenolic compounds, the assessment of the fulfilment of the health claim is an important research issue. The aim of the present work is to study the effect of anthracnose disease together with olive fly attack, naturally occurring in olive orchards of the two most important cultivars for olive oil extraction in Portugal (‘Galega Vulgar’ and ‘Cobrançosa’), on the quality and phenolic compounds related with the health claim, of the VOO obtained, during three harvest years.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Olive Characterization

Portuguese olive fruits (

Olea europaea ssp.

europaea var.

europaea) of ‘Cobrançosa’ and ‘Galega Vulgar’ used in this study were produced in a rainfed olive orchard, without the use of pesticides, in Beira Baixa Region (39º 49’ N, 7º 27’W). The climate of this region is classified as Csa (Mediterranean hot summer climates) according to Köppen climate classification.

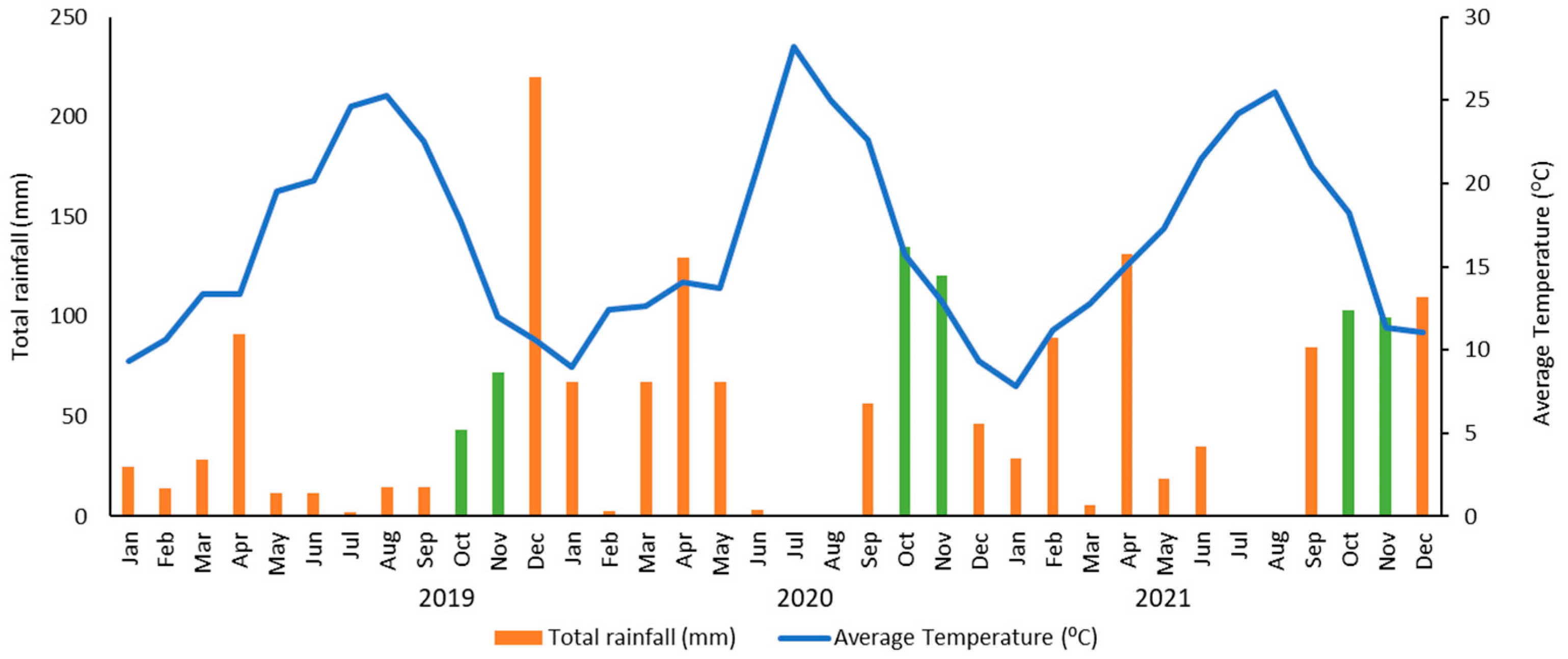

Figure 1 shows the total rainfall and average temperature in each month during the three years of study in this region.

Olive fruits were picked from the first fortnight of October to the second fortnight of November (4 harvest times), in 2019, 2020 and 2021. Their ripening indices (RI) were determined following the guidelines of International Olive Council (IOC) [

29]. The percentage of fruits infected by

Colletotrichum spp. and with olive fly (

Bactrocera oleae) was evaluated. The incidence percentages of olive fly resulted from the visual observation of the number of fruits with the presence of the pest (bite, egg, pupa larva and exit hole) in a sample of one hundred fruits. For anthracnose, fruits were considered affected by

Colletotrichum spp. when typical symptoms of the disease appeared like round and ocher or brown lesions, with profuse production of orange masses of conidia or fruit rot. Observations were carried out in duplicate, on a total of two hundred fruits for each sample.

2.2. Olive Oil Extraction

In the same day of harvesting and based on previous optimized conditions [

30] olive oils were extracted in a laboratory oil extraction system(Abencor analyser; MC2 Ingenieria y Sistemas S.L., Seville, Spain), using a hammer mill equipped with a 4 mm sieve at 3000 rpm, a malaxator (27-30 °C, 30 min) and a centrifuge (3500 rpm, 1 min). After centrifugation, the olive oil was separated by settling in a graduated cylinder. Water traces in the oil were removed with anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered through a cellulose filter, and stored in amber glass bottles at 4 °C.

2.3. Chemical and Sensory Characterization of Olive Oil

Chemical quality criteria, considered by the European Union: acidity value (FFA %), peroxide value (PV), UV specific absorbances (K

232 and K

270), were evaluated for each VOO sample, as well as the major fatty acids (C16:0, C18:0, C18:1 and C18:2) by NIR spectroscopy using a spectrometer (MPA Bruker, Germany), equipped with the calibration model B-Olive oil (Bruker). For the values that were not in conformity with the category of EVOO, a verification was done by official methods (Comission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/2104 of 29 July 2022). Samples of olive oils were also sensory evaluated by a panel test from the Laboratório de Estudos Técnicos, ISA, Portugal, recognized by the IOC. Chlorophyll pigments (PC) were evaluated following the IUPAC method proposed by Pokorný et al. (1995) [

31].Total phenols (TPH) were extracted by liquid microextraction and were evaluated by VIS spectroscopy (JASCO 7800, Tokyo, Japan) as previously described [

19]. For the quantification of hydroxytyrosol (HYT) and tyrosol (TYR) and their derivatives present in the olive oil samples, the hydromethanolic extracts prepared to quantify total phenols were used. Because a fraction of phenolic compounds is linked to other molecules, it is necessary to perform an acid hydrolysis of the phenolic extracts of olive oil for their full quantification[

32,

33]. For the hydrolysis process, the method of Nenadis et al. (2018) [

34] was followed: 2 mL tubes with lids (triplicate), containing 0.5 mL of phenolic extract and 0.5 mL of sulfuric acid (1M), were shaken in a vortex (Labinco L46) for 15 seconds, placed in a thermostatic bath at 80°C for 2 hours and then cooled in an ice bath. The analysis of the phenolic compounds HYT and TYR and their derivatives was carried out according to Reboredo-Rodriguez et al. (2016)[

35], on an Agilent chromatograph, series 1100 (Agilent Technologies Instrument), coupled with a C18 Phenomenex Kinetex column (100 x 3 mm, 2.6 μm) and diode array detector (DAD) (Agilent 1100). Gradient elution was performed with an eluent of water/formic acid (99.5:0.5; v/v) as mobile phase A and acetonitrile as mobile phase B. Total run time was 13 minutes (more 5 minutes post-run). The gradient elution conditions were as follows: 0 min, 95% A; 3 min, 80% A; 4 min, 60% A; 5 min, 55% A; 9 min, 40% A; 10 min, 0% A; 12 min, 95% A; and 13 min, 95% A. The value for the health claim corresponds to the sum of the amounts of HYT and TYR present in mg/20 g VOO. The phenolic profile of the olive oils extracted from fruits with different anthracnose disease was also evaluated by the IOC method as previously described [

36].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data obtained on fruit damage, chemical and sensory characterization of olive oil samples were treated using the software StatisticaTM, version 7, from Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA. ANOVA was performed on the results concerning HYT, TYR and health claim values (in each year for 4 harvest moments). A post hoc Tukey test was used (p ≤ 0.05). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the global dataset considering chemical and sensory results for all VOO samples obtained from Galega Vulgar or Cobrançosa fruits presenting different levels of biological damage and different ripening stages, along the three harvest years. PCA is a pattern-recognition technique that will allow to represent the original multidimensional dataset in a space with smaller dimension and, therefore, helping to characterize the samples and evaluate the presence of eventual groups, as well as identify the most important variables on sample characterization[

37]. Since the health claim value corresponds to the content of HYT and TYR in 20 g of olive oil, the parameter “Heath Claim” was used as supplementary variable in PCA, while HYT and TYR were retained as active variables. Moreover, the ripening index (RI) was also used as supplementary variable. These supplementary variables are not used to build principal components but will help to interpret the variability of the data. Therefore, each VOO sample will be characterized by 18 variables: anthracnose attack, fly attack of the fruits, 4 chemical quality parameters, 4 main fatty acids, 4 sensory attributes, chlorophyll pigments (CP), total phenol content (TPH), HYT and TYR contents.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Quality Criteria of the Oils

Quality criteria (acidity, peroxide value and UV absorbances in combination with organoleptic assessment) are the main parameters that define olive oils categories.

Table 1 shows that only Galega oils obtained in 2020 and 2021, in the last harvest time (RI of 6.4 and 5.1, respectively), that were extracted from fruits with high incidence of anthracnose (91 %) and olive fly attack (69 and 72%, respectively), presented higher acidity (1.52 and 2.12%), and consequently are not in accordance with the category of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO; ≤0.8 % FFA) or virgin olive oil (VOO; ≤ 2.0 % FFA). Therefore, the Galega olive oil sample presenting 2.12 % acidity belongs to the category of “lampante VOO” (L) and cannot be consumed without being refined. Moreover, these two samples presented the sensory defect “musty”, confirming their low quality. All the samples showed peroxide values (PV: 3-10 meqO

2/kg) and UV absorbance values (K

232: 1.38-1.76.; K

270: 0.07-0.18), lower than the maximum values allowed for edible VOO, indicating that VOO oxidation did not occur in large extent in Galega oils. Therefore, the effect of anthracnose and olive fly attack is mainly related with the increase in acidity resulting from oil hydrolysis and with the appearance of musty defect.

Table 2 shows the RI and the incidence of damaged Cobrançosa fruits by anthracnose and olive fly and respective quality criteria of the extracted oils. All Cobrançosa oils presented low acidity (≤ 0.45 %) and oxidation parameters (PV, K

232 and K

270) below the maximum values allowed for EVOO. Moreover, no sensory defects were detected, even when the oils were extracted from ripen fruits, attacked by anthracnose and olive fly.Therefore, all Cobrançosa samples belong to the category of EVOO. The olive fly attack in Cobrançosa olives is represented mainly by bites, and in the case of Galega fruits is the presence of egg, pupa larva and exit hole that represents the main damages. The different susceptibility of Galega and Cobrançosa to pests and diseases has already been explained by cuticle thickness, perimeter and area of epidermal cells [

38], but chemical composition of the fruits, like phenols or waxes are also relevant [

39,

40].

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the composition of both Galega and Cobrançosa olive oils extracted along the three harvests, concerning main fatty acids (palimitic, stearic, oleic and linoleic acids), total content of phenolic compounds (TPH) and chlorophyll pigments (CP). Concerning fatty acid composition, Cobrançosa VOO are richer in linoleic acid (C18:2), which varied from 7.3 to 10.4 % (average = 8.8 %), than Galega VOO (average = 5.2 %; min = 4.7 %; max = 6.4%). Conversely, Galega oils present higher content of oleic acid (C18:1), varying from 75.0 to 77.3 % (average = 75.9%), than Cobrançosa oils, with values ranging from 70.0 to 73.1 % and an average of 71.7%. The results are in accordance with other studies that showed that fruit fly infection and antrachnose disease did not cause an essential change in the fatty acid composition of olive oil [

39]. However an increase in linoleic acid (C18:2), especially in Cobrançosa oils is observed, as already been reported in laboratory trials with olive oils extracted from olives in contact with the disease for several days[

19]. In general, Cobrançosa oils are richer in phenolic compounds (average = 803.3 mg GAE/kg oil) than Galega oils (average = 415.7 mg GAE/kg oil). A decrease in TPH is observed along maturation and with the damage of fruits, mainly for Galega oils, since Galega cultivar is more suceptible to antrachnose disease than Cobrançosa. The same trend is observed for the green pigments (CP). In 2021, greener VOO were obtained for Cobrançosa oils as olives were in a lower RI than in the other years. The lower contents for both cultivars in this year may be explained by meteoriological conditions (as september shows higher rainfall) (

Figure 1).

3.2. Health Claims vs. Olive Damage by Olive Fly and Anthracnose Disease

Most of the identified phenolic compounds in olive oil belong to five different classes: phenolic acids (especially derivatives of benzoic and cinnamic acids), flavonoids (luteolin and apigenin), lignans (pinoresinol and acetoxypinoresinol), phenolic alcohols (hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol) and secoiridoids (derivatives aglycones of oleuropein and ligstroside)[

17]. The group of secoiridoids, as conjugated forms of hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol, has been widely studied due to their healthy properties and represents the phenolic family with the highest concentration in olive oil [

10,

41]. The phenolic fraction of olive oil depends on several parameters related to the quality of the fruits. In fact, cultivar and ripening stage, when considering sound fruits, are the main decisive factors affecting the contents of phenolic compounds in VOOs. In addition, according to Gómez-Caravaca et al., no clear correlation seems to exist between the percentages of fly attack and phenolic content [

42]. Moreover, verbascoside, tyrosol and hydroxytyrosol were the compounds that were most adversely affected by

B. oleae infestation, but the fly attack was significantly correlated with the weight of the fruits, but not with the phenolic compounds [

43]. In fact, anthracnose disease causing more fruit damage than olive fly, and producing lipases that hydrolyze the acylglycerols releasing free fatty acids, can promote more differences in olive oil characteristics than olive fly, as observed in laboratory context studies [

19]. However, when dealing with fruits collected in natural environments, under uncontrolled pest and disease attack, usually clear correlations are very difficult do find, because there are several uncontrolled factors acting in the characteristics of the olives and consequently in olive oil. Harvest time and consequently the maturation of olives are crucial for the presence of phenolic compounds in olives and olive oils [

44,

45]. In the case of early ripening susceptible cultivars to anthracnose disease, the destruction of the fruits will be more severe, the contact with mummified fruits will be longer and a change of the phenolic profile is expected.

During the three harvests, the evolution of the phenolic compounds responsible for the olive oil's health claim (hydroxytyrosol + tyrosol) was evaluated, as well as that of the total phenolic compounds (

Table 3 and

Table 4) in Galega and Cobrançosa olive oils under study.

Table 5 shows the results of the evaluated parameters, as well as the value for the health claim. In the three years, the maximum and minimum levels of hydroxytyrosol in Cobrançosa olive oils were, respectively, 281.9 and 126.8 mg kg

-1, while those of tyrosol were 251.0 and 132.9 mg kg

-1. Comparatively, in Galega olive oils, the hydroxytyrosol, varied between 2.76 and 189.71 mg kg

-1 and from 11.6 to 114.9 mg kg

-1 for tyrosol, respectively.

The results do not show a clear correlation between the percentage of antrachnose incidence and phenolic compounds of olive oils (

Table 1 and

Table 2). However, the concentration of HYT+TYR (Health Claim) is greater than 5 mg/20 g, for all Cobrançosa olive oils, throughout ripening, in the three harvests and regardless of anthracnose and olive fly incidence (

Table 5). On the contrary, in the 2020 and 2021 harvest years, none of the samples of Galega olive oil fulfilled the health claim, even at the beginning of ripening and at low disease incidence levels. In the 2019 harvest year, only Galega olive oils in the first harvest time (at the beginning of ripening RI = 3.1) comply with the health claim requirement (

Table 5). This can be also observed with olive oils extracted from olives infected with antrachnose but asymptomatic fruits [

46].

3.3. Phenolic Profile of Olive Oils with Different Incidence of Anthracnose Disease

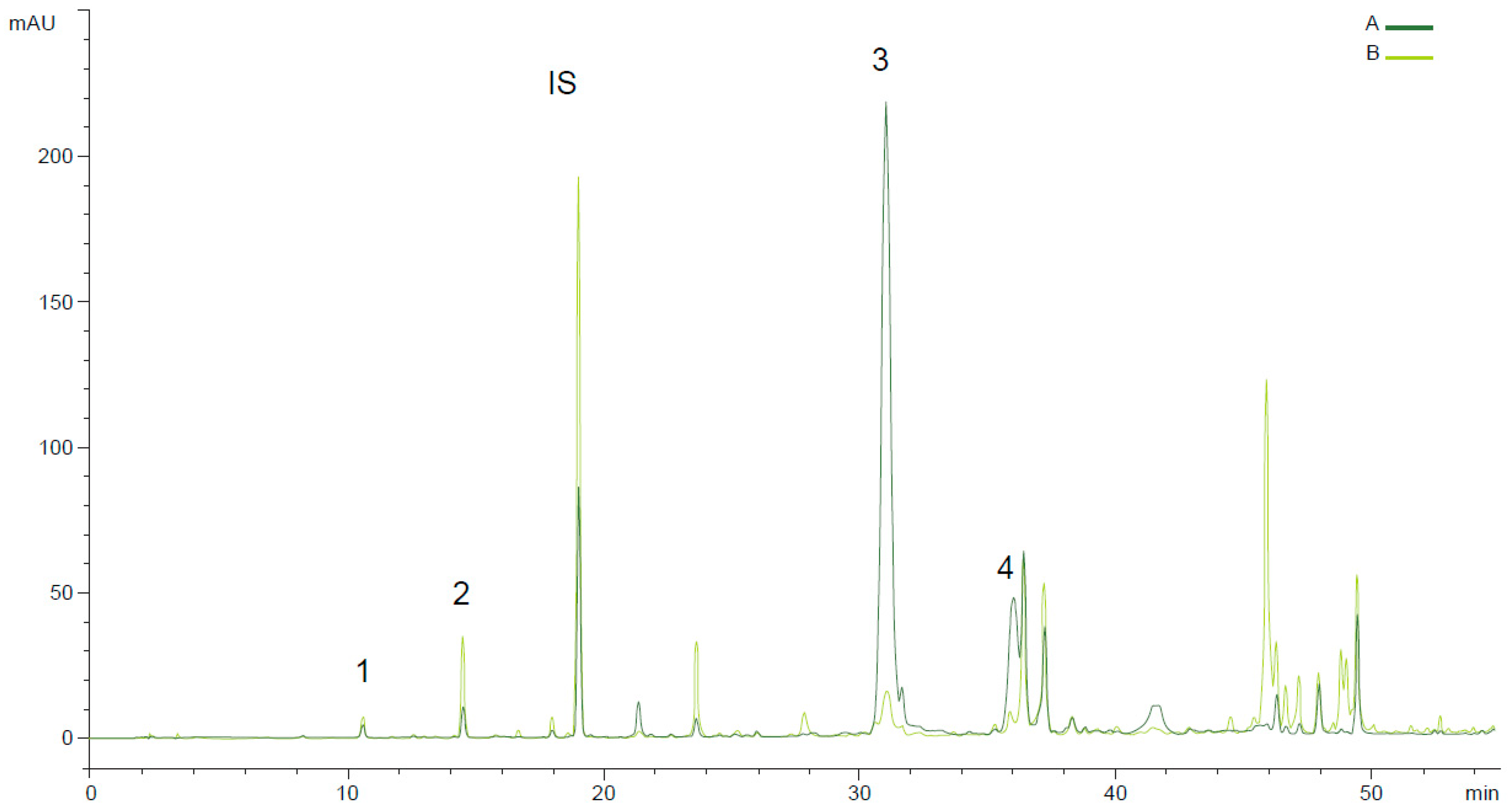

Regarding the main compounds mentioned in the literature, oleacein (HTY-EDA or 3,4- DHPEA-EDA) is the main phenolic compound present in virgin olive oil.

Figure 1 shows the effect of anthracnose disease in the phenolic profile of Galega oils in two ripening moments in 2020 harvest. The ripening stage is critical for the presence of several phenolic compounds. Previous results on phenolic profile of VOO extracted from fruits, performed by Peres et al (2016) [

44,

45], with the same cultivars, showed a decrease in total phenolic content (TPH) after RI=2-3 , when healthy fruits are used in the extraction process, but representing less than 30% decrease. However, this decrease is particularly important in the presence of pests and diseases. In the present study, decarboxymethyloleuropein (oleacein) almost disappeared when anthracnose disease was present in 91% of the fruits, corresponding to a disease severity based on the affected surface of the fruits between 3 and 5 (3: 50–75%, 4: 100%, 5:mummified fruit) [

28]. This secoiridoid decreased 99 %, from 242.54 to 2.5 mg kg

-1 in the 2020 harvest for Galega oils (

Figure 2).

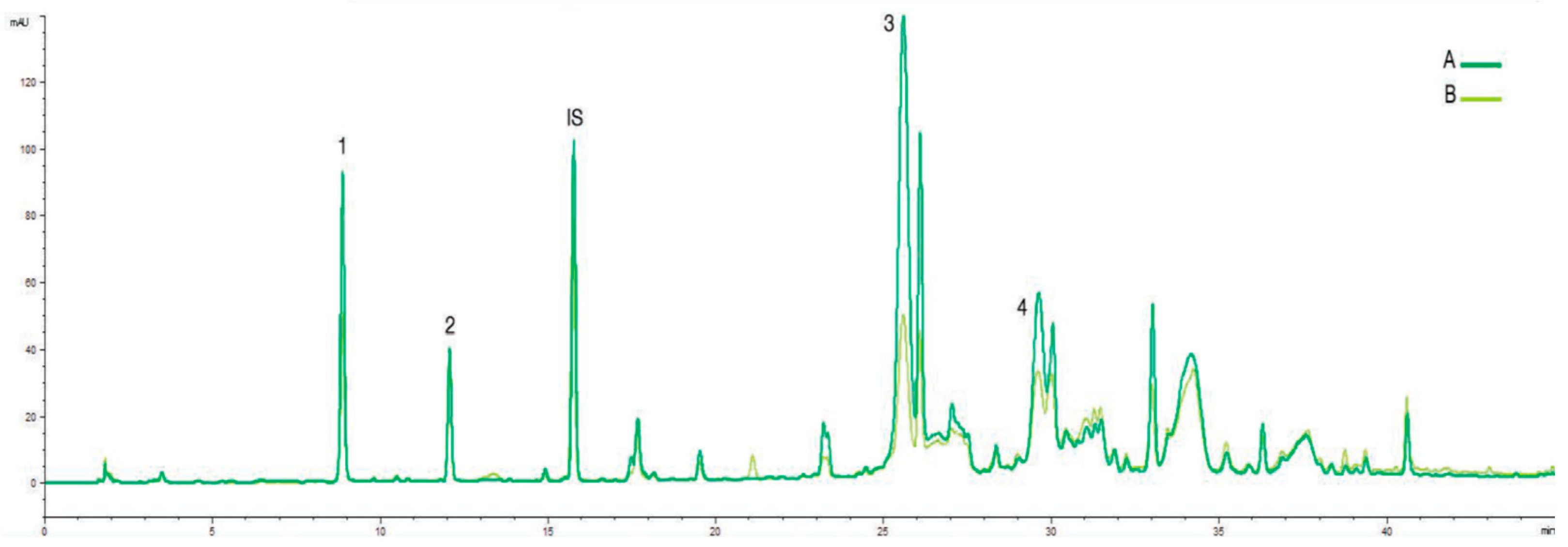

The damage of Cobrançosa fruits was not followed for the same ripening index of the fruits as in Galega since this last cultivar is early ripening. However, for Cobrançosa olive oils obtained at two ripening index (2 and 4), the effect of the presence of olive fly and antrachnose was much smaller than for Galega cultivar. A smaller decrease in the main cromatographic peaks was observed but the main phenolic compounds did not disappear (

Figure 3).

Although olive fly was already present at the beginning of ripening (RI = 2-3), when the first fruits were collected, the phenolic profiles are very similar to those of the olive oils from healthy fruits [

44]. In fact, Notario et al., (2022) [

47] did not found any difference between infested with

Bactrocera olea and non-infested fruits in the content of 3,4- DHPEA-EDA of the oils for Picual and Hojiblanca cultivars.

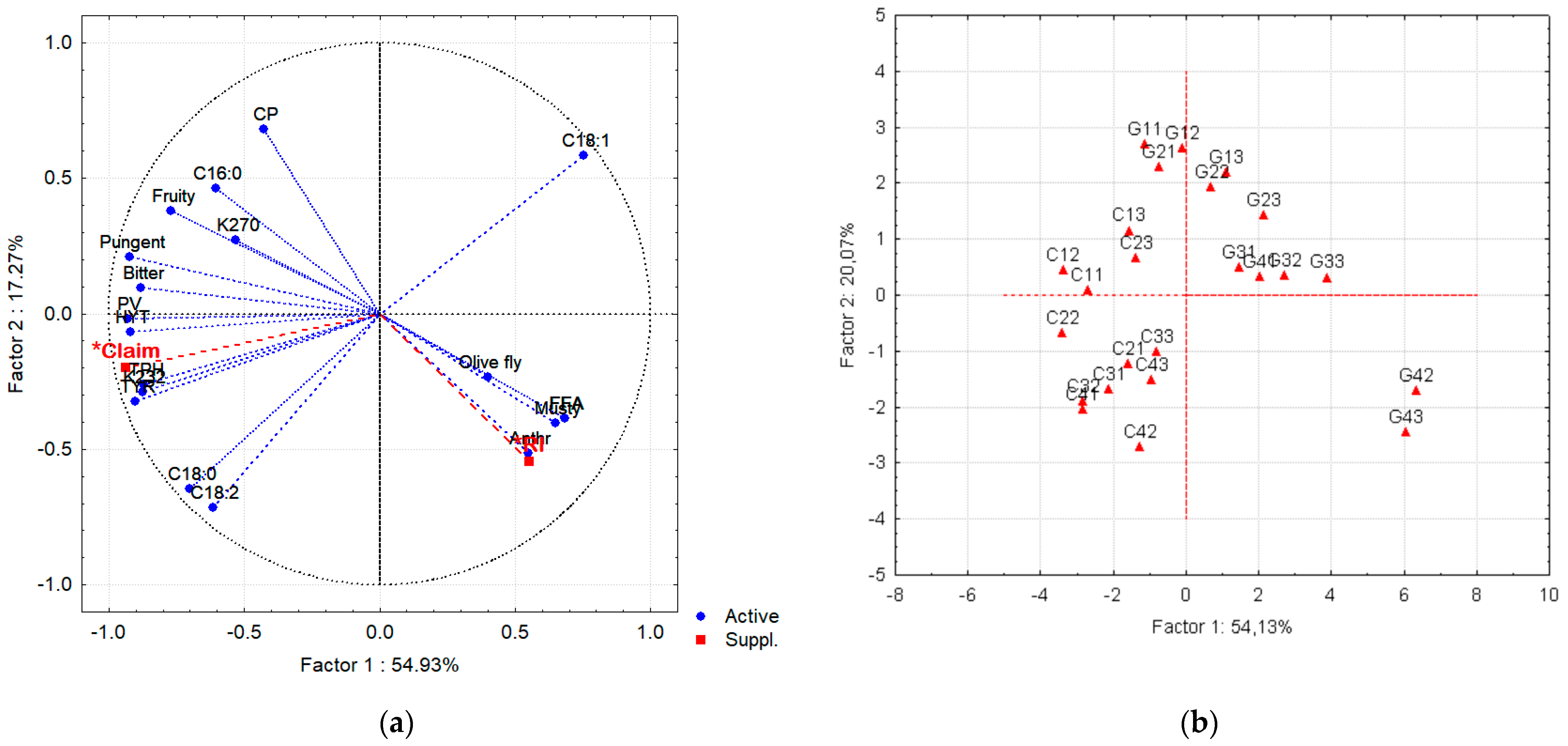

3.1. Multivariate Characterization of the Olive Oils

To assess the effect of both anthracnose and olive fly attack on the quality of the VOO, a PCA was performed on the global data, i.e. on a matrix with 24 samples (lines) defined by 18 active variables and two supplementary variables, namely the health claim (Claim) and the ripening index (RI). By PCA, it was possible to reduce the original 18-dimension space to a plane defined by the first two principal components (Factor 1 and Factor 2 of

Figure 4). These first two factors have eigenvalues of 9.89 and 3.11, corresponding to a variance of 54.9 and 13.0 %, respectively. Therefore, the plane defined by factors 1 and 2 explains 72.2% of the variance and, therefore, of the information explained by the original dataset in an 18-dimension hyperspace.

Figure 4a shows that the first principal component (Factor 1) is highly correlated with the positive sensory attributes of VOO mainly bitterness and pungency, and with total phenolic compounds (TPH) and the contents of TYR and HYT. As expected, the health claim is highly correlated with TPH, TYR and HYT. Therefore, Factor1 can be identified as the Health Claim axis, since the parameters related with this claim are highly correlated with this axis, increasing along its negative side. Along this axis, towards the negative sense, the plotted samples present increasing quality and health claim value (

Figure 4b). Cobrançosa VOO samples have always higher Health claim value, are more pungent and bitter and present higher TPH contents, than the Galega VOO from fruits harvested in the same dates (

Figure 4b).

Figure 4a shows that the anthracnose attack is highly correlated with the acidity increase (FFA) and the negative sensory attribute musty in VOO. The olive fly attack is also related with these defects. This confirms that fly attack facilitates the infection of the fruits by

Colletotrichum spp. Moreover, the ripening index (RI), considered as illustrative variable, shows to be highly correlated with anthracnose attack, confirming that ripen fruits are rather prone to this fungal disease, which will be responsible for the bad quality of their oil. In fact, the lowest quality VOO are the samples G42 and G43 of Galega Vulgar, harvested in 2020 and 2021, by the end of November (t4), as observed in

Figure 4b. G42 and G43 samples were extracted from fruits with high incidence of anthracnose (91 %) and olive fly attack (69 and 72%, respectively), resulting in VOO with higher acidity (1.52 and 2.12%), and musty sensory defect. The content of phenolic compounds considerably decreased to 87.05 and 137.9 mg GAE/kg VOO, corresponding to 13 and 39% of the level in VOO extracted from the fruits at early ripening stage (early October). Consequently, these samples have very low values for the health claim: 0.29 and 0.42 mg/20 g VOO.

Figure 4b suggests a separation of Cobrançosa and Galega Vulgar VOO into two groups, according to the cultivar. Along the second axis (Factor 2 or Principal Component 2), the content of chlorophyll pigments (CP) and oleic acid (C18:1) increase in the positive sense (

Figure 4a). Galega VOO are, in general, richer in green pigments and oleic acid than Cobrançosa VOO (

Figure 4b). However, a decrease in CP is observed for both cultivars along ripening. The reddish coloration intensity that is usually correlated to the proportion of symptomatic fruit with anthracnose [

46] was only observed in G43 sample.

From PCA, it is possible to conclude that the attack of the fruits by Colletotrichum spp and/or olive fly has a more severe effect on the quality of Galega Vulgar VOO than on Cobrançosa VOO. PCA also confirms that the early harvest is an adequate strategy to avoid high levels of anthracnose and fly attack, preserving the quality of VOO, for both cultivars, but mandatory for Galega olives, specially under changing climate.

4. Conclusions

The presence of the health claim on the labeling of EVOO can represent an instrument for differentiating and valuing olive oils, running as an indicator of ‘high quality olive oil’. To achieve this, the olive oil must have a minimum value of 5 mg of hydroxytyrosol and its derivatives per 20 g of olive oil.

The main interest of this study, in what concerns the marketing of extra virgin olive oils, is to validate the eligibility for the health claim in Galega and Cobrançosa olive oils.

The present study shows that some of the VOO extracted from the highly susceptible cultivar to anthracnose Galega do not meet the requirements of the health claim. Conversely, Cobrançosa oils, even when extracted from fruits with high percentages of olive fly and anthracnose, still fulfill the health claim, because this cultivar presents very high contents of phenols and the damage of the fruits is less severe than for Galega olives. However, the presence of pests and fungal diseases may compromise the use of Cobrançosa oils in award-winning olive oil blends, mainly due to the decrease in the intensity of the pungent and bitter positive attributes.

The importance of early ripening in the presence of phenolic compounds in olive oils is again shown in the present study. However, the early harvesting time may not be sufficient for Galega oils to fulfill the health claim and new strategies in olive growing should be found to control pests and diseases. Moreover, if the disease is present in the fruits, it is mandatory to perform the extraction of olive oils as soon as possible, according to good practices recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P. and S.F.D.; methodology, F.P., C.G.; software, S.F.D.; validation, F.P. and S.F.D.; formal analysis, C.G., C.V., F.P.; investigation, F.P., C.G.; resources, F.P.; data curation, F.P., C.G., C.V. and S.F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P., S.F.D., C.G.; writing—review and editing, F.P. and S.F.D.; visualization, F.P. and S.F.D.; supervision, F.P. and S.F.D.; project administration, F.P.; funding acquisition, F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/04129/2020 of LEAF-Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food, Research Unit, and the research project PTDC/ASP-PLA/28547/2017.

Data Availability Statement

data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Trichopoulou, A.; Dilis, V. Olive oil and longevity. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2007, 51, 1275-1278. [CrossRef]

- La Lastra, C.; Barranco, M.D.; Motilva, V.; Herrerias, J.M. Mediterrranean Diet and Health Biological Importance of Olive Oil Current Pharmaceutical Design 2001, 7, 933-950.

- Roche, H.M.; Gibney, M.J.; Kafatos, A.; Zampelas, A.; Williams, C.M. Beneficial properties of olive oil. Food Research International 2000, 33, 227-231.

- Martín-Peláez, S.; Covas, M.I.; Fitó, M.; Kušar, A.; Pravst, I. Health effects of olive oil polyphenols: Recent advances and possibilities for the use of health claims. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2013, 57, 760-771. [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Brenes, M.; García, P.; Garrido, A. Hydroxytyrosol 4-β-d-Glucoside, an Important Phenolic Compound in Olive Fruits and Derived Products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2002, 50, 3835-3839. [CrossRef]

- Wani, T.A.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A.; Baba, W.N.; Rahmanian, N.; Akhter, R.; Wani, I.A.; Ahmad, M. Olive oil and its principal bioactive compound: Hydroxytyrosol – A review of the recent literature. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2018, 77, 77-90. [CrossRef]

- Roselli, L.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Corbo, F.; De Gennaro, B. Are health claims a useful tool to segment the category of extra-virgin olive oil? Threats and opportunities for the Italian olive oil supply chain. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2017, 68, 176-181. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M.P.; Jimenez, A.; Sanchez-Villasclaras, S.; Uceda, M.; Beltran, G. Modulation of bitterness and pungency in virgin olive oil from unripe “Picual” fruits. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2015, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Andrewes, P.; Busch, J.L.H.C.; Joode, T.; Groenewegen, A.; Alexandre, H. Sensory Properties of Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols: Identification of Deacetoxy-ligstroside Aglycon as a Key Contributor to Pungency. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003, 51, 1415-1420.

- Bendini, A.; Cerretani, L.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Caravaca, A.M.G.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Lercker, G. Phenolic Molecules in Virgin Olive Oils: a Survey of Their Sensory Properties, Health Effects, Antioxidant Activity and Analytical Methods. An Overview of the Last Decade. Molecules 2007, 12, 1679-1719.

- Aparicio, R.; Ferreiro, L.; Alonso, V. Effect of climate on the chemical composition of virgin olive oil. Analytica Chimica Acta 1994, 292, 235-241. [CrossRef]

- Guerfel, M.; Ouni, Y.; Taamalli, A.; Boujnah, D.; Stefanoudaki, E.; Zarrouk, M. Effect of location on virgin olive oils of the two main Tunisian olive cultivars. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2009, 111, 926-932. [CrossRef]

- Tura, D.; Failla, O.; Bassi, D.; Pedò, S.; Serraiocco, A. Environmental and seasonal influence on virgin olive (Olea europaea L.) oil volatiles in northern Italy. Scientia Horticulturae 2009, 122, 385-392.

- Artajo, L.S.; Romero, M.P.; Motilva, M.J. Transfer of phenolic compounds during olive oil extraction in relation to ripening stage of the fruit. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2006, 86, 518-527. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, G.; Aguilera, M.P.; Rio, C.; Sanchez, S.; Martinez, L. Influence of fruit ripening process on the natural antioxidant content of Hojiblanca virgin olive oils. Food Chemistry 2005, 89, 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Brkić Bubola, K.; Koprivnjak, O.; Sladonja, B.; Škevin, D.; Belobrajić, I. Chemical and sensorial changes of Croatian monovarietal olive oils during ripening. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2012, 114, 1400-1408. [CrossRef]

- Servili, M.; Montedoro, G. Contribution of phenolic compounds to virgin olive oil quality. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2002, 104, 602-613. [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.; Luz, J.P.; Fragoso, P.; Gouveia, C.; Vitorino, C.; Amaro, C.; Henriques, L.; Coutinho, J.; Pintado, C.M.; Peres, C.; et al. Integrated Production and Quality of Galega Olive Oil. IOBC Bulletin 2010, 145-149.

- Peres, F.; Talhinhas, P.; Afonso, H.; Alegre, H.; Oliveira, H.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Olive Oils from Fruits Infected with Different Anthracnose Pathogens Show Sensory Defects Earlier Than Chemical Degradation. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1041.

- Koprivnjak, O.; Dminić, I.; Kosić, U.; Majetić, V.; Godena, S.; Valenčič, V. Dynamics of oil quality parameters changes related to olive fruit fly attack. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2010, 112, 1033-1040. [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, R.; Casal, S.; Baptista, P.; Pereira, J.A. A review of Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) impact in olive products: From the tree to the table. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2015, 44, 226-242. [CrossRef]

- Rojnić, I.D.; Bažok, R.; Barčić, J.I. Reduction of olive fruit fly damage by early harvesting and impact on oil quality parameters. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2015, 117, 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Talhinhas, P.; Loureiro, A.; Oliveira, H. Olive anthracnose: a yield- and oil quality-degrading disease caused by several species of Colletotrichum that differ in virulence, host preference and geographical distribution. Molecular Plant Pathology 2018, 19, 1797-1807. [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, G.; Moral, J.; Strano, M.C.; Caruso, P.; Sciara, M.; Bella, P.; Sorrentino, G.; Di Silvestro, S. Characterization of Colletotrichum strains associated with olive anthracnose in Sicily. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 2022, 61, 139-151.

- Cacciola, S.O.; Faedda, R.; Sinatra, F.; Agosteo, G.E.; Schena, L.; Frisullo, S.; Magnano di San Lio, G. Olive anthracnose. Journal of Plant Pathology 2012, 94, 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Moral, J.; Jurado-Bello, J.; Sánchez, M.I.; de Oliveira, R.; Trapero, A. Effect of Temperature, Wetness Duration, and Planting Density on Olive Anthracnose Caused by Colletotrichum spp. Phytopathology® 2012, 102, 974-981. [CrossRef]

- Moral, J.; Xaviér, C.; Roca, L.F.; Romero, J.; Moreda, W.; Trapero, A. Olive Anthracnose and its effect on oil quality. Grasas y Aceites 2014, 65, e028. [CrossRef]

- Leoni, C.; Bruzzone, J.; Villamil, J.J.; Martínez, C.; Montelongo, M.J.; Bentancur, O.; Conde-Innamorato, P. Percentage of anthracnose (Colletotrichum acutatum s.s.) acceptable in olives for the production of extra virgin olive oil. Crop Protection 2018, 108, 47-53. [CrossRef]

- IOC. Guide for the determination of the characteristics of oil-olives. COI/OH/Doc. Nº.1. 2011.

- Peres, F.; Martins, L.L.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Laboratory-scale optimization of olive oil extraction: Simultaneous addition of enzymes and microtalc improves the yield. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2014, 116, 1054-1062. [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, J.; Kalinová, L.; Dysseler, P. Determination of Chlorophyll pigments in Crude Vegetable Oils Pure Appl. Chem. 1995, 67, 1781-1787.

- Mastralexi, A.; Nenadis, N.; Tsimidou, M.Z. Addressing Analytical Requirements To Support Health Claims on “Olive Oil Polyphenols” (EC Regulation 432/2012). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62, 2459-2461. [CrossRef]

- Tsimidou, M.Z.; Sotiroglou, M.; Mastralexi, A.; Nenadis, N.; García-González, D.L.; Gallina Toschi, T. In House Validated UHPLC Protocol for the Determination of the Total Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol Content in Virgin Olive Oil Fit for the Purpose of the Health Claim Introduced by the EC Regulation 432/2012 for “Olive Oil Polyphenols”. Molecules 2019, 24, 1044.

- Nenadis, N.; Mastralexi, A.; Tsimidou, M.Z.; Vichi, S.; Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Donarski, J.; Bailey-Horne, V.; Butinar, B.; Miklavčič, M.; García González, D.-L.; et al. Toward a Harmonized and Standardized Protocol for the Determination of Total Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol Content in Virgin Olive Oil (VOO). Extraction Solvent. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2018, 120, 1800099. [CrossRef]

- Reboredo-Rodríguez, P.; Valli, E.; Bendini, A.; Di Lecce, G.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Gallina Toschi, T. A widely used spectrophotometric assay to quantify olive oil biophenols according to the health claim (EU Reg. 432/2012). European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2016, 118, 1593-1599. [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.; Marques, M.P.; Mourato, M.; Martins, L.L.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Ultrasound Assisted Coextraction of Cornicabra Olives and Thyme to Obtain Flavored Olive Oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 6898.

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis, Second Edition. ed.; Springer-Verlag,: New York Inc, 2002.

- Gomes, S.; Bacelar, E.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Carvalho, T.; Guedes-Pinto, H. Infection process of olive fruits by Colletotrichum acutatum and the protective role of the cuticle and epidermis. Journal of Agricultural Science 2012, 4, 101.

- Abacıgil, T.Ö.; Kıralan, M.; Ramadan, M.F. Quality parameters of olive oils at different ripening periods as affected by olive fruit fly infestation and olive anthracnose. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali 2023, 34, 595-603. [CrossRef]

- Rebora, M.; Salerno, G.; Piersanti, S.; Gorb, E.; Gorb, S. Role of Fruit Epicuticular Waxes in Preventing Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae) Attachment in Different Cultivars of Olea europaea. Insects 2020, 11, 189.

- López-Huertas, E.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Olive oil varieties and ripening stages containing the antioxidants hydroxytyrosol and derivatives in compliance with EFSA health claim. Food Chemistry 2021, 342, 128291. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Cerretani, L.; Bendini, A.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Del Carlo, M.; Compagnone, D.; Cichelli, A. Effects of Fly Attack (Bactrocera oleae) on the Phenolic Profile and Selected Chemical Parameters of Olive Oil. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008, 56, 4577-4583. [CrossRef]

- Medjkouh, L.; Tamendjari, A.; Alves, R.C.; Laribi, R.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Phenolic profiles of eight olive cultivars from Algeria: effect of Bactrocera oleae attack. Food & Function 2018, 9, 890-897. [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.; Martins, L.L.; Mourato, M.; Vitorino, C.; Antunes, P.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Phenolic compounds of ‘Galega Vulgar’ and ‘Cobrançosa’ olive oils along early ripening stages. Food Chemistry 2016, 211, 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.; Martins, L.L.; Mourato, M.; Vitorino, C.; Ferreira-Dias, S. Bioactive compounds of Portuguese virgin olive oils discriminate cultivar and ripening stage. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 2016, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Santa-Bárbara, A.E.; Moral, J.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Roca, L.F.; Trapero, A. Effect of latent and symptomatic infections by Colletotrichum godetiae on oil quality. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2022, 163, 545-556. [CrossRef]

- Notario, A.; Sánchez, R.; Luaces, P.; Sanz, C.; Pérez, A.G. The Infestation of Olive Fruits by Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) Modifies the Expression of Key Genes in the Biosynthesis of Volatile and Phenolic Compounds and Alters the Composition of Virgin Olive Oil. Molecules 2022, 27, 1650.

Figure 1.

Monthly total rainfall (bars) and average temperature (solid line) in 2019, 2020 and 2021 in Beira Baixa Region (39º 49’ N, 7º 27’W), Portugal. The months where samples were collected correspond to the green bars.

Figure 1.

Monthly total rainfall (bars) and average temperature (solid line) in 2019, 2020 and 2021 in Beira Baixa Region (39º 49’ N, 7º 27’W), Portugal. The months where samples were collected correspond to the green bars.

Figure 2.

Phenolic profile (RP-HPLC-UV 280 nm) of Galega olive oil obtained with olives in two ripening moments and with different anthracnose disease (A) RI = 3 and anthracnose = 5%; (B) RI = 6 and anthracnose - 91%. 1- HYT, 2-TYR, IS - Internal standard (syringic acid), 3- oleacein, 4- oleocanthal.

Figure 2.

Phenolic profile (RP-HPLC-UV 280 nm) of Galega olive oil obtained with olives in two ripening moments and with different anthracnose disease (A) RI = 3 and anthracnose = 5%; (B) RI = 6 and anthracnose - 91%. 1- HYT, 2-TYR, IS - Internal standard (syringic acid), 3- oleacein, 4- oleocanthal.

Figure 3.

Phenolic profile (RP-HPLC-UV 280 nm) of Cobrançosa olive oil obtained with olives in two ripening moments and with different anthracnose disease severity (A)RI = 2 and anthracnose -30%; (B) RI = 4 and anthracnose = 64%. 1- HYT, 2-TYR, IS - Internal standard (syringic acid), 3- oleacein, 4- oleocanthal.

Figure 3.

Phenolic profile (RP-HPLC-UV 280 nm) of Cobrançosa olive oil obtained with olives in two ripening moments and with different anthracnose disease severity (A)RI = 2 and anthracnose -30%; (B) RI = 4 and anthracnose = 64%. 1- HYT, 2-TYR, IS - Internal standard (syringic acid), 3- oleacein, 4- oleocanthal.

Figure 4.

Plot of (a) the loadings of the original variables and (b) of the samples on the plane defined by principal component 1(Factor 1) and 2 (Factor 2) (C: Cobrançosa VOO samples; G: Galega VOO samples; the subscripts of the samples, ty, correspond to the harvest time (t= 1,…,4) and year (y = 1, ..3; where 1= 2019; 2 =2020; 3 = 2021); the abbreviations of the variables are the same used in Tables 1 to 5). Health claim (Claim) and RI are suplementary variables.

Figure 4.

Plot of (a) the loadings of the original variables and (b) of the samples on the plane defined by principal component 1(Factor 1) and 2 (Factor 2) (C: Cobrançosa VOO samples; G: Galega VOO samples; the subscripts of the samples, ty, correspond to the harvest time (t= 1,…,4) and year (y = 1, ..3; where 1= 2019; 2 =2020; 3 = 2021); the abbreviations of the variables are the same used in Tables 1 to 5). Health claim (Claim) and RI are suplementary variables.

Table 1.

Quality criteria: Acidity (FFA), peroxide value (PV), UV absorbances (K270, K232), and sensory attributes for Galega oils extracted from olives with different damages by olive fly (Fly, %) and anthracnose (Anthr., %) disease and ripening index (RI). Mean values; Olive oil category: EVOO – extra virgin olive oil; VOO – virgin olive oil; L – lampante oil.

Table 1.

Quality criteria: Acidity (FFA), peroxide value (PV), UV absorbances (K270, K232), and sensory attributes for Galega oils extracted from olives with different damages by olive fly (Fly, %) and anthracnose (Anthr., %) disease and ripening index (RI). Mean values; Olive oil category: EVOO – extra virgin olive oil; VOO – virgin olive oil; L – lampante oil.

| Year |

Anthr. (%) |

Fly (%) |

RI |

FFA (%) |

PV

meqO2 kg-1

|

K232

|

K270

|

Bitter |

Pungent |

Musty |

Category |

| 2019 |

9 |

47 |

3.1 |

0.38 |

8.60 |

1.65 |

0.17 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 5 |

57 |

3.1 |

0.37 |

9.92 |

1.76 |

0.13 |

7.3 |

7.8 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 51 |

82 |

4.1 |

0.50 |

7.44 |

1.57 |

0.13 |

4.9 |

4.6 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 70 |

35 |

5.8 |

0.64 |

6.53 |

1.50 |

0.12 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 2020 |

3 |

44 |

1.8 |

0.34 |

9.95 |

1.69 |

0.18 |

9.1 |

8.9 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 5 |

16 |

2.9 |

0.23 |

8.61 |

1.58 |

0.12 |

7.3 |

5.2 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 25 |

42 |

4.8 |

0.23 |

4.30 |

1.50 |

0.10 |

4.6 |

2.8 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 91 |

69 |

6.4 |

1.52 |

3.18 |

1.46 |

0.10 |

0 |

0 |

1.2 |

VOO |

| 2021 |

0 |

15 |

2.1 |

0.32 |

9.02 |

1.71 |

0.13 |

2.8 |

4.3 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 0 |

41 |

3.5 |

0.33 |

6.50 |

1.53 |

0.11 |

2.2 |

3.7 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 3 |

59 |

3.8 |

0.42 |

4.23 |

1.38 |

0.07 |

0 |

0.6 |

0 |

EVOO |

| 91 |

72 |

5.1 |

2.12 |

4.33 |

1.56 |

0.13 |

0 |

0 |

1.9 |

L |

Table 2.

Quality criteria: acidity, peroxide value (PV), UV absorbances (K270, K232) and sensory attributes for Cobrançosa oils extracted from olives with different damages by olive fly (Fly, %) and anthracnose (Anthr., %) disease and ripening index (RI). Olive oil category: EVOO – extra virgin olive oil; VOO – virgin olive oil; L – lampante oil.

Table 2.

Quality criteria: acidity, peroxide value (PV), UV absorbances (K270, K232) and sensory attributes for Cobrançosa oils extracted from olives with different damages by olive fly (Fly, %) and anthracnose (Anthr., %) disease and ripening index (RI). Olive oil category: EVOO – extra virgin olive oil; VOO – virgin olive oil; L – lampante oil.

| Year |

Anthr. (%) |

Fly % |

RI |

FFA (%) |

PV

meqO2 kg-1

|

K232

|

K270

|

Bitter |

Pungent |

Category |

| 2019 |

0 |

36 |

1.6 |

0.26 |

15.23 |

2.05 |

0.19 |

8.1 |

7.9 |

EVOO |

| 30 |

83 |

3.8 |

0.30 |

11.63 |

1.97 |

0.16 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

EVOO |

| 44 |

63 |

3.5 |

0.45 |

10.93 |

1.85 |

0.14 |

6.8 |

6.0 |

EVOO |

| 64 |

36 |

5.2 |

0.42 |

11.43 |

1.86 |

0.12 |

8.7 |

6.2 |

EVOO |

| 2020 |

6 |

29 |

2.4 |

0.34 |

15.51 |

1.96 |

0.19 |

9.4 |

9.8 |

EVOO |

| 4 |

14 |

3.4 |

0.28 |

13.06 |

2.02 |

0.17 |

9,1 |

9.5 |

EVOO |

| 4 |

26 |

3.9 |

0.28 |

11.20 |

1.93 |

0.10 |

8.1 |

7.3 |

EVOO |

| 12 |

40 |

4.7 |

0.22 |

7.73 |

1.78 |

0.09 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

EVOO |

| 2021 |

0 |

27 |

1.0 |

0.32 |

12.55 |

1.87 |

0.18 |

6.1 |

7.2 |

EVOO |

| 0 |

46 |

1.9 |

0.34 |

11.21 |

1.77 |

0.15 |

5.7 |

7.1 |

EVOO |

| 24 |

73 |

2.7 |

0.34 |

10.91 |

1.73 |

0.14 |

5.6 |

6.5 |

EVOO |

| 9 |

28 |

3.8 |

0.39 |

10.13 |

1.71 |

0.10 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

EVOO |

Table 3.

Galega olive oil composition: main fatty acids, total phenols (TPC) and chlorophyl pigments (CP) for the harvest times reported in

Table 1.

Table 3.

Galega olive oil composition: main fatty acids, total phenols (TPC) and chlorophyl pigments (CP) for the harvest times reported in

Table 1.

| Year |

C16:0 (%) |

C18:0 (%) |

C18:2 (%) |

C18:1 (%) |

TPC

mg GAE/kg |

CP

mg/kg |

| 2019 |

15.76 |

2.52 |

4.94 |

74.98 |

626.41 |

65.49 |

| 15.33 |

2.67 |

4.96 |

75.04 |

504.82 |

50.60 |

| 14.52 |

2.59 |

5.22 |

75.29 |

458.49 |

28.44 |

| 14.04 |

2.39 |

4.95 |

76.54 |

468.29 |

1.72 |

| 2020 |

13.95 |

2.22 |

4.90 |

76.49 |

681.43 |

61.24 |

| 14.25 |

2.42 |

4.76 |

75.90 |

539.03 |

34.43 |

| 13.33 |

2.44 |

5.32 |

76.16 |

337.09 |

4.96 |

| 12.60 |

2.53 |

4.70 |

77.28 |

87.05 |

5.37 |

| 2021 |

14.35 |

2.30 |

5.42 |

75.18 |

352.22 |

64.88 |

| 14.08 |

2.22 |

5.54 |

75.60 |

274.85 |

30.58 |

| 13.58 |

2.30 |

5.55 |

75.75 |

210.15 |

8.55 |

| 13.27 |

2.42 |

6.43 |

75.17 |

137.90 |

2.50 |

Table 4.

Cobrançosa olive oil composition: main fatty acids, total phenols (TPC) and chlorophyl pigments (CP) for the harvest times reported in

Table 2.

Table 4.

Cobrançosa olive oil composition: main fatty acids, total phenols (TPC) and chlorophyl pigments (CP) for the harvest times reported in

Table 2.

| Year |

C16:0 (%) |

C18:0 (%) |

C18:2 (%) |

C18:1 (%) |

TPC

mg GAE/kg |

CP

mg/kg |

| 2019 |

14.78 |

3.12 |

7.71 |

72.42 |

762.33 |

28.39 |

| 14.28 |

3.13 |

8.82 |

71.48 |

718.72 |

21.21 |

| 14.66 |

3.11 |

9.03 |

71.57 |

1019.05 |

16.29 |

| 14.25 |

3.09 |

8.88 |

71.81 |

1233.62 |

3.57 |

| 2020 |

14.81 |

3.09 |

7.25 |

72.33 |

1081.71 |

60.95 |

| 14.32 |

3.20 |

9.78 |

70.25 |

904.14 |

49.65 |

| 14.08 |

3.39 |

10.39 |

69.96 |

911.16 |

7.82 |

| 13.66 |

3.56 |

10.26 |

70.15 |

710.95 |

1.19 |

| 2021 |

13.95 |

2.89 |

7.29 |

72.93 |

501.17 |

79.94 |

| 13.89 |

2.91 |

7.99 |

73.05 |

526.18 |

71.65 |

| 13.61 |

2.96 |

8.80 |

72.64 |

607.72 |

33.39 |

| 13.60 |

3.10 |

9.39 |

71.38 |

662.80 |

16.32 |

Table 5.

Anthracnose and fly attack of fruits and respective values of total hydroxytyrosol (HYT) and tyrosol (TYR) and Health Claim values for Cobrançosa and Galega oils obtained in the three harvest years and along maturation, corresponding to the samples reported in

Table 2. In each column, different letters indicate that the results are significantly different at a p≤ 0.05 (Tukey test), in each year.

Table 5.

Anthracnose and fly attack of fruits and respective values of total hydroxytyrosol (HYT) and tyrosol (TYR) and Health Claim values for Cobrançosa and Galega oils obtained in the three harvest years and along maturation, corresponding to the samples reported in

Table 2. In each column, different letters indicate that the results are significantly different at a p≤ 0.05 (Tukey test), in each year.

| Cobrançosa virgin olive oils |

Galega virgin olive oils |

| Year |

HYT

(mg/kg) |

TYR

(mg/kg) |

Health claim (mg/20g) |

HYT

(mg/kg) |

TYR

(mg/kg) |

Health claim (mg/20g) |

| 2019 |

199.92±14.58b

|

228.09±4.21 b

|

8.56±0.13 b

|

189.71±1.09a

|

114.94±5.98a

|

6.09±0.14a

|

| 126.87±3.39c

|

199.91±1.61 c

|

6.54±0.04 c

|

146.57±10.03b

|

107.02±9.87a

|

5.07±0.03b

|

| 223.43±5.46b

|

224.90±1.27 b

|

8.97±0.11 b

|

120.29±1.19c

|

85.94±1.09b

|

4.12±0.05c

|

| 281.93±9.91a

|

251.04±1.84 a

|

10.66±0.20 a

|

109.21±3.27d

|

69.23±0.13c

|

3.6±0.08d

|

| 2020 |

261.66±35.13a

|

207.52±3.51 a

|

9.38±0.77 a

|

143.79±12.02a

|

60.36±4.70a

|

4.08±0.16 a |

| 216.06±5.04b

|

201.29±26.93 a

|

8.35±0.63 b

|

108.41±8.71b

|

65.61±5.03a

|

3.48±0.27 b |

| 213.85±5.67b

|

169.39±5.42 b

|

7.66±0.11 b

|

56.39±4.66c

|

40.62±2.31b

|

1.94±0.14 c |

| 138.08±2.00 c

|

132.93±4.05 c

|

5.42±0.07 c

|

2.76±0.97d

|

11.57±2.62c

|

0.29±0.09 d |

| 2021 |

201.17±2.25a

|

162.52±0.86 a

|

7.27±0.06a

|

125.12±3.03a

|

80.52±0.73a

|

4.1±0.45 a

|

| 196.54±11.71a

|

161.07±0.89 a

|

7.15±0.25a

|

109.20±0.53b

|

56.36±0.31b

|

3.31±0.02 a |

| 195.98±8.94a

|

165.94±1.45 a

|

7.24±0.15a

|

41.20±0.17c

|

30.82±2.11c

|

1.44±0.04 a |

| 209.08±0.10a

|

146.96±0.56 b

|

7.12±0.01a

|

3.51±0.98 d

|

17.34±0.24d

|

0.42±0.02 a |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).