1. Introduction

The second decade of the twenty-first century has seen important economic and social transformations to a large extent because of the international economic crisis that began in 2008. A crisis that altered the order of urban and social problems, making socioeconomic vulnerability a practically generalized, complex and chronic problem in Spain. The ‘inherited urban and socioeconomic structures’ accentuated the distance between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of the crisis [

1] (p. 2). This inequality hinders possibilities for more resilient dynamics, which in cur-rent post-pandemic scenarios becomes even more essential [

2]. The results would speak to the existence of a ‘negative spiral’ in which worse socioeconomic conditions lead to greater economic vulnerability and a concentration of elements that contribute to maintaining the situation of imbalance between the city’s districts.

In recent years we have witnessed a growing interest in building integrated perspectives of urban planning to combat situations of vulnerability and urban inequity [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Likewise, literature highlights the increasing role given to public space and urban green systems for the well-being of people, urban health, and social cohesion [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Yet, despite the growing importance of urban vulnerability, social exclusion, degradation of the natural and built environment in aca-demic and policy [

12,

13], and in the Spanish and Andalusian context [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The established relationship between the urban space and the capacity to reverse such situations of vulnerability is still unclear.

Integration between social sustainability and urban sustainability is one of the focuses of debate at the environmental international agenda [

20]. Different authors establish an approach to the conditions of the urban form that directly influence social sustainability [

21]. Working definitions and evaluation frameworks for assessing the social sustainability of urban areas have been proposed by academics. However, frameworks that provide a more thorough structure for study are required to link the qualitative and quantitative dimensions of social sustainability [

22]. Neighborhood scale as the smallest urban scale through which to study and solve social problems is indicated [

23], while access to facilities, living space and social interaction as key aspects for improvement of citizen perception of urban security and satisfaction is highlighted [

24].

From a theoretical perspective, this paper aims to understand the different networks sustained in urban space, mainly represented by public space and its relationship with the urban facilities fabric. This makes it necessary to reflect on the multidimensional nature of public space, and its ability to articulate future transformations of neighbor-hoods or areas of cities. The relationship between urban regeneration and social cohesion has been widely studied as one of the fundamental characteristics of social innovation [

25]. The fact of favoring the meeting of people, diverse actors, and institutions is necessary to lead to a social change beneficial to society [

26]. As a support for the characteristics of social improvements to develop (networking, social relations, collaboration, and social cohesion), public space is therefore key in urban regeneration contexts. This requires making the spatial network visible and defining its shaping characteristics, while also pursuing the definition and visibility of its social and environmental systems or networks, and the evaluation of its potential in urban regeneration policies.

Consequently, we hypothesize that it is in urban physical structure where both social factors that make up collective spaces and their environmental factors are most clearly manifest. Thus, beginning with an in-depth analysis of public space, we evaluate social and environmental factors together with subsequent planning of actions would facilitate the regeneration of both the social and environmental fabrics.

Following this hypothesis, the guiding research questions are de-fined as follows: (i) How to produce a vulnerability analysis of a do-main that has pre-existing spatial conditions? (ii) What role can public space and the urban network assume that would make it function systemically in urban regeneration? (iii) How does the interaction take place between the ‘spatial offer’ of the observed city and the intervention strategies that combat its social and environmental vulnerability?

The article begins with the contextualization of the regeneration strategies that can serve as a reference framework for the case study. Secondly, the paper analyses the role that public space and urban green infrastructure can play in social cohesion, under the hypothesis that equal access to resources and services directly affects the reversal of urban vulnerability situations. The characterization of the Barrios Altos of Jaén is addressed through two approaches: (1) a methodological proposal for the analysis of vulnerability factors; and (2) an urban and cartographic analysis of public space in a broad sense, as a potential offer for the configuration of operational urban networks.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section, the situation of vulnerability of the case study is exposed and the foundations are laid for each of the networks (urban, social, and environmental). We consider (1) ‘public space nodes’ as places of social interaction for the strengthening of self-esteem and the emergence of participatory initiatives and policies, (2) the extension of favorable conditions of the peri-urban environment annexed to the whole area through a discontinuous but linked environmental classroom, and (3) the urban recovery and the promotion of a greater number of diverse functions. The paper ends with an analysis of the results and several conclusions for this case, and for the application of this methodology in general, through the integration of networks based on the cohesive and multidimensional value of the pre-existing public space.

2. Literature Review

The concept of vulnerability can be defined as a state of high exposure to certain risks and uncertainties in combination with a reduced ability to protect or defend oneself against those risks and uncertainties and cope with their negative consequences. Vulnerability exists at all levels and dimensions of society and forms an integral part of the human condition, affecting both individuals and society as a whole [

12]. Understood in this way, vulnerability is the prelude to social exclusion, poverty and the breeding ground for the decline of residential urban areas, combining spatial dimension and social structure, linked bidirectionally [

7,

27]. European studies of the early 1990s on the return of urban poverty explore it as a multidimensional phenomenon, not just an economic one [

28]. This lack of welfare is defined by an intersection of a lack of access to the state, the market, and solidarity/community/family, in a process heavily dependent on urban space and local neighborhoods [

29,

30].

Unequal endowment and quality of public space in different areas of the city is one of the testimonies of existing social and spatial segregation processes and an added vulnerability factor, which contributes to the perpetuation of underprivileged neighborhoods. According to Alguacil et al., `the vulnerability of a territory combines objective factors and subjective factors; on the one hand, it is constituted by conditions of social disadvantage, and, on the other hand, it is a psychosocial environment that affects perceptions that citizens have of the territory in which they live’ [

17] (p. 79). For this reason, vulnerability must be understood as contextual and linked to a specific territory.

The concentration of poverty in at-risk or vulnerable neighbor-hoods of cities is one of the main problems of the European Union to-day. Much evidence indicates this, such as the ‘Seventh Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion in the EU’, which places the risk of poverty or social exclusion in the cities of countries that joined the Union before 2004 at levels higher than those prior to the crisis [

31].

2.1. Urban Regeneration Strategies in the Context of Research

Instruments like The URBAN Community Initiative [

13] allowed different states to develop urban regeneration strategies in ‘neighbor-hoods in crisis’ up to 2006. Furthermore, in the Spanish context, URBAN contributed to incorporating concepts that at the end of the 20th century had not yet been widely introduced into the practice of urban regeneration. Among them, we would highlight the ‘integrated approach’: (1) collaboration between institutions and different levels of government; (2) involving the population and local actors through participatory processes; and (3) urban regeneration based on sustainable urban development [

16].

Strategies had to act from an integrated perspective at all dimensions of degradation (social, economic, environmental, governance...), and ensure actions-initiated changes that would overcome periods of decline and the approach of traditional urban policies that are merely spatial or sectoral. It was intended to consolidate new dynamics of urban sustainability assuming a heterogeneous and complex urban reality [

3,

4].

The main objective of urban regeneration is to increase the well-being of residents by proposing not only improvements to the physical space, but also through achieving social cohesion and identification with environment and economic as well as social and cultural development [

32]. When regeneration strategies in central areas have consisted of mere physical and ‘urban transformation’, this has given rise to gentrification processes, disregarding the pre-existing population and seeking standards that provoked drastic transformations of the social fabric. The economic transformation and investments in historic centers have often come before social policy, entrepreneurship and training in the productivity of residents. In turn, this has led to the abandonment of daily life in these areas and their outsourcing.

On the contrary, urban regeneration strategies must increase the local capacities of the pre-existing population to ensure true ‘resistance’ that has been shown many times as an alternative to deterioration and gentrification coupled with top-down ‘urban renewal’ projects [

33].

In this sense, it is worth mentioning two examples of Rehabilitation Plans for historic neighborhoods that have tackled the problem collectively, emphasizing neighborhood retrofitting and the improvement of public space structure and conditions: the Special Plan for Safeguarding Moraria, Lisbon [

34] (

Figure 1) and the Rive Gauche Rehabilitation Project, Molenbeek, Brussels [

35]. In both cases, the intro-duction of new collective facilities was a central objective to improve the living conditions of the resident population and their permanence, while pursuing the integration of the new population. The economic revitalization was tackled through the diversification of functions and the protection of traditional uses, promoting new activities housed in newly built buildings. In both plans, the prolonged time of the implementation process allowed for the adjustment between physical trans-formations and their assimilation by the population, also allowing the evaluation of the effects of each phase.

Urban policies that demonstrate the need for territorial governance criteria as a working method, which implies, for its design and execution, establishing collaboration and coordination mechanisms with other levels of government and with the civil society [

5].

2.2. Urban Cohesion and Urban Open Space: Dimensions of Public Space for a More Cohesive City

In the EUROsociAL Program, social cohesion is associated with a model based on social justice, the primacy of the rule of law and solidarity [

37]. In other words, the European concept of cohesion is based on social rights and equal access to resources and basic services [

38]. Likewise, policies in favor of social cohesion would tend to enhance the economic possibilities of the population through employment and im-prove their levels of integration and social bonding. Considering, moreover, the issues raised by Maloutas and Pantelidou (2004) on the ambiguity of the concept of social cohesion and the variable impact of cohesion promotion in different socioeconomic situations. We would speak, in this sense, of social cohesion as a reinforcement of social capital and urban resilience in the area:

The rationale for policies promoting cohesion is linked to the form of local social interaction that should be improved through increased engagement in formal and informal networks on a mutuality and solidarity basis, leading to the formation and/or the reinforcement of a social capital without which the feasibility of collective improvement strategies (practically perceived as local regeneration) would be reduced [

38] (p. 451).

In the spatial framework of cities, this combination of opportunities and challenges requires the integration of strategies that achieve a friendly environment, sustainable transportation, reducing air pollution and increasing biodiversity, greater proximity to green spaces, more productive and connected neighborhoods, etc. [

31] (p. xv-xvi). In this sense, urban ecosystems and green infrastructure fulfill an important social function in improving the integration of socially vulnerable groups [

8,

9]. The role of spaces linked to an increase in biodiversity and the provision of multiple ecosystem services is essential to create a greater sense of community and help combat social exclusion and isolation [

31], and to improve the integration of ethnic minorities, especially among younger groups [

39,

40].

The main capital for strengthening urban ecosystems and green infrastructures is free urban space, mainly the public space. That is why it is necessary to understand its current situation and its increasingly diverse dimensions in order to achieve such regenerative capacities.

Furthermore, the incorporation of biodiversity concept into urban planning has modified priorities and placed urban open space at the center. Recent perceptions emphasizing the infrastructure approach also represent a more socio-economic perspective, offering the potential to address the economic value system of spatial development [

41] (p. 7). As noted by Meerow & Newell, it is these multiple benefits and resulting synergies that allow the green infrastructure approach to provide an “opportunity to enhance social-ecological resilience and equity” [

42]. Proof of this is its consideration as an interconnected component that guides sustainable urban development integrated into The New Urban Agenda [

43], and the central role given to public space for social and economic development [

11]. In this same line, a multidimensional relationship can be established between the concepts of the disciplines focused on planning and the objectives that contribute to the increase of biodiversity in cities [

44] (

Table 1).

Understanding the ecosystem function of urban open space and, mainly, the components of potential green infrastructure must entail a search for connectivity for integration into networks. In fact, in the definition and understanding of the term green infrastructure, great importance is given to the high quality of these elements and their membership as an essential part of an interconnected network [

41,

45]. This network structure is precisely what gives systemic capacity to the diverse set of initially isolated territorial spaces and resources [

40]. We would be talking about a very broad catalog of elements that would encompass practically all the unbuilt space, the biophysical matrix of free spaces, which must be seen as a single interconnected system.

In favor of social cohesion and, according to Mandeli [

10] (p. 3), the appropriation of public space and the fulfillment of its function as a social articulator of the network that they make can be achieved through the integration of different actions and urban design criteria. These criteria would respond to a threefold spatial, institutional and sociocultural dimension that is key in the sustainable development between cities and their environment, contemplating issues related to planning, management, functionality, and the sociocultural. In the Spanish planning context, there are good examples of reinterpretation of pre-existing public space to create a social articulator that strengthens cultural identities. In the Special Plan for the Historic Center of Toledo (1998), the ‘Mediterranean patio’ becomes the catalyst for the revitalization of daily life, as the lungs of the city and for the location of new viewpoints [

46]. The studies for

La ciutat vella de Barcelona [

47] identify a set of urban sequences that link meaningful public spaces, which would make it possible to reinforce neighborhood identity, and make the spatial and commercial values of Ciutat Vella visible

3. Materials and Methods

Research focuses on historical capillary fabrics, the keys to revitalize its urban space, the lack of identity and true functionality of an annexed forest park, in direct connection with a first-level heritage element. To this end, we address the conditions and capacities analysis of public space for the formulation of urban regeneration strategies, understood as a multi-relational system: network system and set of elements that constitute a physical environment of collective expression and social and cultural diversity [

48], and of a multidimensional nature [

10]. Networks are presented as one of the hallmarks of urban re-generation that works on the social innovation of an urban fabric [

25], as networking can build shared interests, reciprocal support and mutual benefit with each partner contributing according to their respective resources, strengths, and areas of expertise [

49]. Public spaces, from this integrated vision, incorporate their social and cultural value into the general context of the area, conforming themselves as nodes of the system prepared to be able to be incorporated into the network of scenarios of daily life in the city [

50].

In order to carry out this spatial and thematic reformulation, it is necessary to identify a public space structure that has the capacity to provide urban and social cohesion. We know of the close relationship between the social and urban problems of vulnerable neighborhoods and the loss and deterioration of their public space from the studies carried out in American cities by Massey and Denton [

51] in which the process of social segregation of ethnic minorities in obsolete urban are-as generates a circle of social, economic and spatial degradation [

52] (p. 45). This line of study, focused on diverse issues such as the role of race, but also on segregation patterns [

53] or the relevance of ‘ghettos’ [

54], argued that `segregated individuals tend to live in worse social conditions because they possess fewer connections with other social groups´ [

30]. This lack of connectivity or membership in broader social networks leads to less access to services and opportunities.

For this reason, in an inverse relationship, the public space, and social, network project has the capacity to activate urban regeneration dynamics by promoting community cohesion, economic activity and citizen security [

14], for which it is necessary to identify key network places that articulate the urban functions and symbolic representation of the community. They would be what Ruben Kaztman [

55] referred to as ‘structures of opportunity,’ or what Musterd et al. [

29] called ‘sources of welfare;’ networks that can assist individuals transcend geographical obstacles and social spaces, giving them access to larger social circles [

30] (p. 1069). Later, such networks will be studied using a carto-graphic analysis of spatial/urban resources. The latter implies considering the geographical and urban specificity of said network, a sense of territoriality of the public space network that grounds it to local context and responds to the four systems defined by Lang [

56]: terrestrial, ani-mal, social and cultural. Thus, the relationship between the observable and methodology is considered inseparable, between the spatial re-sources and their potential to shape the collective structure of future urban-ecological regeneration [

57].

This leads, in a first approximation, to the need to know the social reality through an analysis of urban vulnerability of Jaén´s neighbor-hoods, as well as the ‘spatial offer’ of the area, through a cartographic analysis. The second approximation grants a relevant role to research through the project [

58], for the identification of such a spatial network and for the assignment of roles to the different spaces of opportunity within the framework of the urban regeneration strategy.

3.1. Case Study: The Altos Neighborhoods of Jaén´s Historic Center

This part of the city is defined by abrupt topography, on which the historic neighborhoods that constitute the southern limit of the city are built, located on the old national highway or

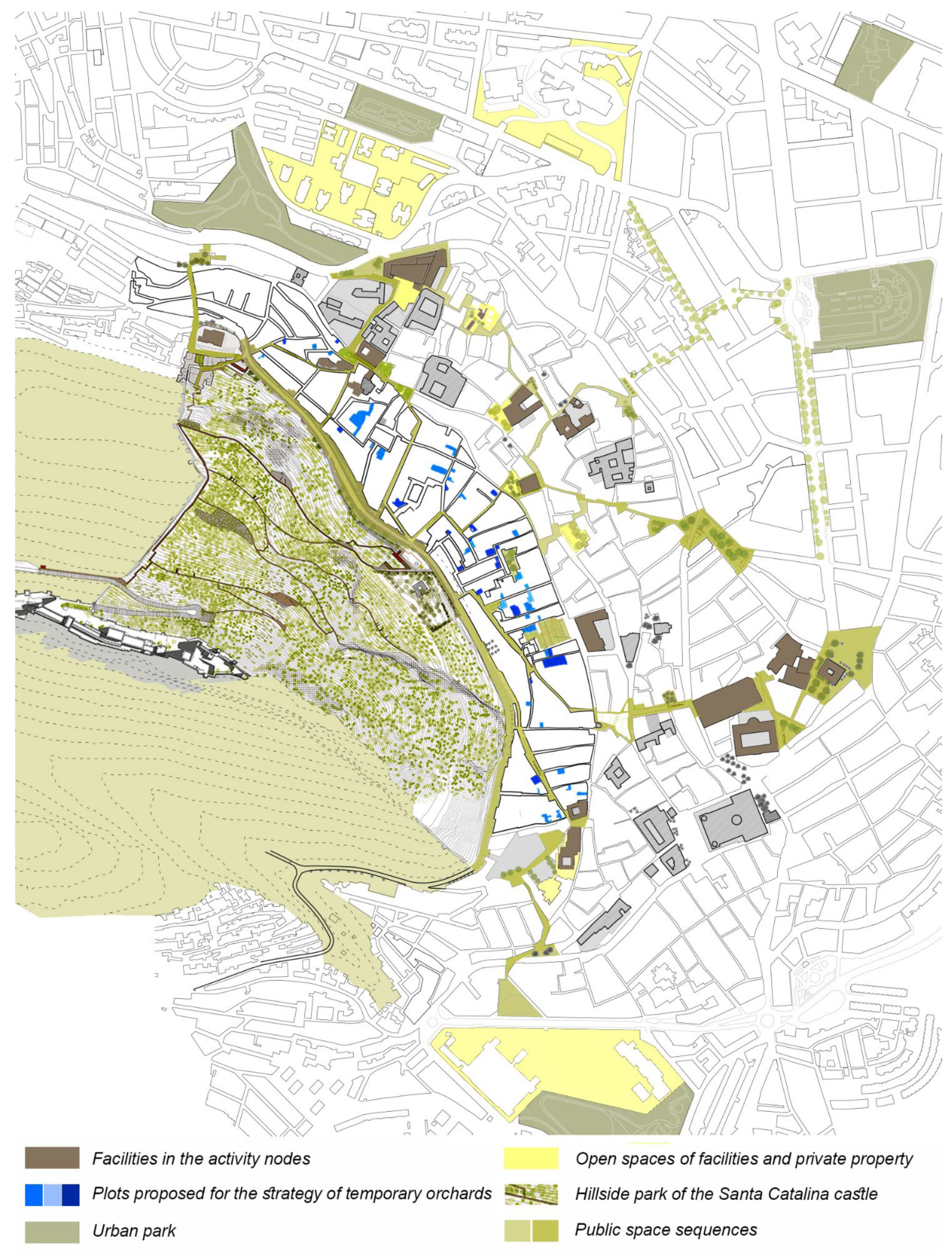

Paseo de Circunvalación, which crosses the slope from east to west and provides access to the castle (

Figure 2).

A strong topography and fringe condition added to the lack of di-versified activities and unemployment of the population has resulted in the marginalization of the San Juan and San Bartolomé neighbor-hoods with respect to the rest of the historic city [

59], together with a process of physical degradation, depopulation and the appearance of a large number of plots and building walls in poor condition. Indeed, the ‘Atlas of household income distribution’ carried out by the National Employment Institute highlights the income gap between the poorest neighborhoods (San Juan, La Magdalena, San Bartolomé and La Judería) compared to the richest neighborhoods in the new urban expansions, reaching a €50,000 difference in family income [

60]. This has caused an emergency situation that requires ideas to reverse the trend: protect the social fabric, revitalize, enrich, and value the urban and architectural fabric.

Actions have been carried out through the URBAN 2006 community initiative and through the Regional Urban Initiative (2007-2013) financed with the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), in-tending to develop innovative strategies for urban regeneration [

16]. They did not have the expected dynamizing effect inciting the citizens themselves promote measures with a greater dose of reality and collective value of their public spaces. One example is the reAviva Jaén movement, which has carried out projects such as #verdEA or #Plaza-Cambil, or the #PROYECTOrEAcciona project. These projects tried to transform the growing number of abandoned lots in the historic com-plex of Jaén into public spaces born, according to the project, ‘of citizen participation, self-management, institutional-neighborhood co-responsibility, creativity, respect, imagination and social innovation’ [

61].

Beyond these initiatives, a true sustained and integrated strategy is necessary to update the city´s central urban fabric. This could only be developed within an urban planning framework which Jaén has fallen behind on, still having an Urban Plan from 1996.

3.2. Multidimensional Approach to Urban Vulnerability

In the city of Jaén, neighborhoods such as San Vicente Paúl or Magdalena-San Juan are classified as ‘disadvantaged areas’ by Egea et al. [

15]. That is, areas that present a series of weaknesses in sociodemographic structure and/or in environmental qualities, a complex situation resulting from a lack of resources that prevents enjoying a quality of life equal to other areas of the city [

62]. On the other hand, the

Urban Vulnerability Observatory [

63] includes in its Catalog of Vulnerable Neighborhoods of Spain 2011, the Vulnerable Statistical Area

San Juan, including the neighborhoods of La Merced, Centro, San Bartolomé, San Juan, Judería, San Miguel and La Magdalena (

Figure 3) that constitute the object of study. The

Urban Vulnerability Observatory is a long-term project of the Ministry of Development, which accommodates different studies related to Urban Vulnerability, in development of the provisions of the Land and Urban Rehabilitation Law [

64]. The levels of net income per person shown in

Figure 4 (data from 2018), show the sustained situation of precariousness, unequal even with respect to other neighborhoods in the historic center.

The list of factors used addresses the multidimensional condition of urban vulnerability, endorsed by numerous studies since the beginning of this century that define it as a difficult and disadvantage situation in an urban area because of all kinds of barriers (economic, social, environmental, and also, cultural) [

12]; a situation that is, in addition, a contextual inequality in the city, preventing integration and participation of members of social groups of that urban environment [

12] (p. 12).

As is the case with social sustainability or, to a certain extent, social cohesion, which could be considered the flip side of urban vulnerability, qualitative and quantitative dimensions are interlinked and interconnected [

22]: ‘A socially sustainable environment has a dialectical character […] physical qualities and standards are positively perceived, highly valued and interactively utilized by the residents through sustaining and endurable social practices, […] a place where substantial social qualities are sustained, highly valued and vividly exercised within an urban setting of high physical quality’[

22] (p. 4). Specifically, this research specifically connects with previous studies in the Spanish context that groups vulnerability factors into blocks [

6,

15,

17,

18,

19,

38], and which are the basis of the Urban Vulnerability Observatory [

63]. This allows, for a majority of determining factors, access to the data collected by the observatory which is progressively updated, being the data available and depending on the factors used, those corresponding to the 2001, 2011 or 2018 census sections.

The dimensions at the base of urban vulnerability are socioeconomic and sociodemographic, which group the main indicators. However, other factors are also considered that would reduce the ability to overcome, individually and/or collectively, emergency or risk situations, that would hinder social integration or increase social vulnerability, factors that incorporate dimensions related to institutional, environmental, and urban conditions of the neighborhoods considered [

15,

18,

19,

31,

38].

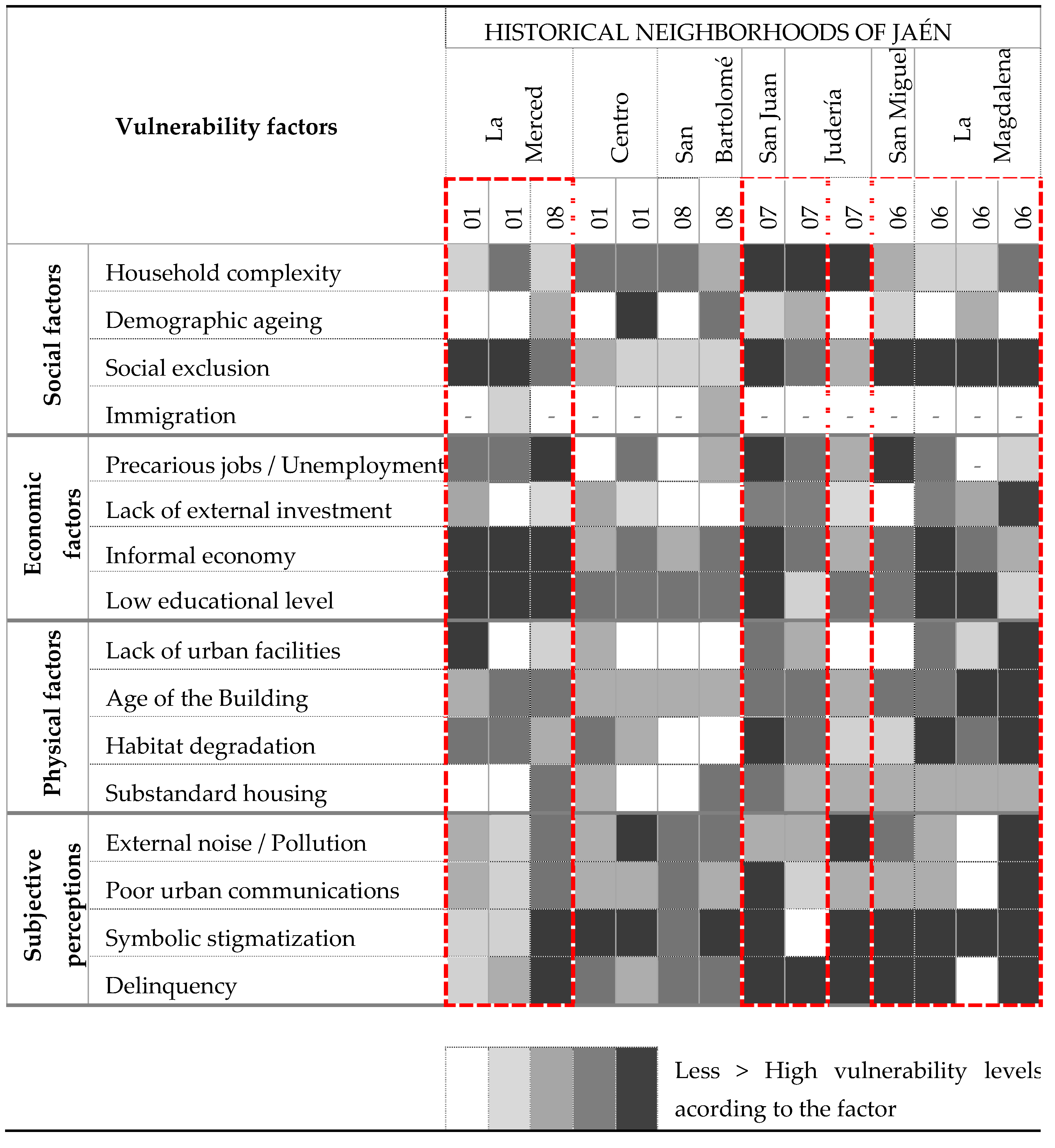

Treatment of the vulnerability of this area is carried out through a methodological proposal that follows three criteria: (1) the need to establish dimensional blocks that group the factors into ‘thematic’ vulnerabilities; (2) the integrated vision of these dimensional blocks and the understanding of the interrelation of some factors with others; and (3) the simultaneous consideration between dimensions of vulnerability and potentialities that anticipate desirable regeneration policies. For this, four dimensional blocks are presented: I. Economic factors, II. Social factors, III. Physical factors and IV. Subjective perception (See

Figure 5).

Table 2 describes the vulnerability factors that make up each block, the component indicators, as well as the various sources of data and/or documents used, or proprietary methodologies developed.

The interdependence between social and economic vulnerability is a consensus in the revised theoretical framework, even though the resolution of its social problems cannot be deduced from the mere eco-nomic growth of an area [

12]. The proposed methodological diagram seeks to obtain a wide perspective of vulnerability that responds to the interdependence of factors between blocks. It is a kind of ‘circle or spiral of dependency’ in which situations of social, labor and income disadvantage, together with environmental and citizen perception, combine and reinforce each other [

17,

18].

For each of the ‘thematic vulnerabilities’ some ‘hybrid factors’ have been proposed, resulting from interdependencies with the other dimensional blocks, fulfilling two objectives: (1) sector completion, and (2) an increase interrelation between blocks that make up the multidimensional analysis, being the first step for the consideration of spatial quality and its effects on the analyzed disadvantage situations. These factors apply to all blocks: (I) social exclusion; (II) the lack of foreign in-vestment and the submerged economy; (III) the lack of urban facilities and habitat degradation; and (IV) symbolic stigmatization (

Figure 5).

3.3. Cartographic Approach to the Programmatic Potential of Urban Space

The research is based on a broad and comprehensive conception of vulnerability that is linked to definitions of risk that involves both territories and social groups, thus recognizing an identification between space and social structure [

17]. Also from the economic sciences, the contemporary city is understood as ‘organization spaces’, ‘network spaces’ or, even, ‘constellation of places linked with different functions’ [

32,

65,

66], where urban economy and territorial context intersect directly. In this two-way relationship, the material with which urbanism can specifically work is public space, taking advantage of its capacity to accommodate various uses and its adaptability over time [

67]. Even more so in historical fabrics, the main challenge for the future of public space will be to establish a correct balance of its spatial, social, and functional dimensions, in relation to its emerging dynamics -positive and negative-, achieving the necessary coexistence and diversity [

68,

69]. It would be about emphasizing those values, qualities or specificities that urban design possesses and about documenting its profound base in a reticulated social and cultural landscape.

Faced with fragmentation, isolation, and inequalities the methodological proposal builds continuities or a complex system of ‘micro-histories’ [

70]. This transforms the city with new ecological links, of movement, of centralities, cultural, landscape and crossroads. The existing city is studied as a multiscale and broadly encompassing point of departure, and yet attentive to local voices and responsive to change [

71]. It would be about exploring the potential that urban forms contain to solve problems, reformulating pre-existing spaces and their relationships in search of a certain ‘rhizomic assemblage’, that ‘mixes the concept of the narrative path of the individual with the networked or shared information of the group’ [

71] (p. 78-153).

The cartographic approach carried out is supported by field work, documentary analysis and photo interpretation, in connection with different dimensions on urban vulnerability described previously. Through this inquiry, the objective of revealing the networked urban form is pursued, using the ‘information embedded’ in it [

72] (p. 460). The (re)interpretation of urban reality and cartographic inquiry make it possible to detect and propose free space networks with operational capacity; recombined space that is ‘in search of a program’, that is, focused on the experience of territorial transformations as a part of networks of themes revolving around different spaces and social groups [

73]. Paying more attention to the processes than to the urban forms, ‘re-signifying’ the cartography will suppose: 1) the observation and comparison of the different times of the studied area; 2) the de-composition of the elements of the plane according to their functional links; and 3) the directed juxtaposition of elements and their orientation, considering their interaction.

4. Results. Definition of Multidimensional Field Networks

This Three thematic networks are first identified -social network, environmental network and urban or functional network-. When operating over the same territory and with the same urban facts, the networks are observed superimposed, studying contrasts and interrelations. There are places in the area studied which, when the actions of the three net-works are added, are recognizable as urban nodes, in line with the two directions of work within the urban context that Grahame Shane pro-posed in his ‘recombinant urbanism: the ‘deconstruction of the city section’ and the open, multivalent, layered systems with distributed nodes he finds in landscape urbanism today’ [

74] (p. 77). These nodes are places that incorporate the collective and the narrative into network logic, ‘central nodes of activity’ claimed by Alexander et al. [

75] (p. 164-167), places of reference with prior symbolic value that are reinforced with the multiple strategy of regeneration.

A multidimensional analysis has been carried out (

Figure 6), identifying urban structures, identity features, main lines of communication with the rest of the city, facility locations classified according to types and places with significant views of the territory. After the first diagnostic phase, the existing urban centers, places active and social con-centration of concentration, and notable axes of the urban fabric in these neighborhoods are also identified based on their functionality (

Figure 6, b and c). Connectivity with the center of Jaén is studied by identifying the intermodal and public transport stops, as well as the articulation between private vehicle parking lots and pedestrian routes (

Figure 6d,e).

4.1. Social Network

The situation of the central high-rise neighborhoods of Jaén is analyzed according to social, residential, urban and economic aspects, starting from the vulnerability factors that have been defined by various studies [

15,

17,

18,

19,

59,

76,

77] and from the data collected in the Urban Vulnerability Observatory (Catalog of Vulnerable Neighborhoods), and, particularly, in the Atlas of Urban Vulnerability 2001-2011 [

59] (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

Vulnerability in these areas is always multidimensional, based on four basic axes [

17]: sociodemographic vulnerability, socioeconomic vulnerability, residential vulnerability, and subjective vulnerability. Vulnerability conditions are analyzed according to the proposed methodological diagram, referencing the main and own sources cited (

Table 3), which includes the public survey developed for these same neighborhoods and the cartographic approximation elaborated.

With the data obtained, it is observed that in the area there are circumstances of vulnerability such as social exclusion, low levels of employment and education, which leads to a very high level of informal economic support, environmental degradation and scarcity of services and urban endowments, resulting in an important symbolic stigmatization of the population.

Based on the results of the vulnerability study, the necessary to identify a ‘social network’ that would make it possible to balance urban dynamics and help urban legibility becomes clear. The network enables involvement between the players, which could lead to new social, eco-nomic, financial, cultural, and political arrangements through a pro-cess built in a collaborative way and disseminated through knowledge sharing [

25]. This network, supported by the recognition of qualities of the urban fabric -safe, multifunctional, and flexible-, and in a series of capacities -generation of a feeling of belonging, of conformation of social capital [

78], etc.-, is instrumental to combat vulnerability through the constant revitalization of the environment.

Sociability requires the existence of a supporting social space together with the physiological provision of comfort [

56], a sense of ownership and social justice in space [

79]. In the central context of Jaén, one of the main objectives would be to strengthen the self-esteem of the social fabric, since it must support the remaining dynamics to be implemented: the generation of participatory dynamics, the promotion of initiatives of the population premises and actions of the administration that improve the inhabited landscape.

The articulator of this strategy is, without a doubt, the public space. Understood in a broad sense, a good part of urban identity and the capacity for social interaction depends on it. In this case, its degradation and the lack of green spaces and facilities, is observed as one of the main features of the historic neighborhoods of Jaén (

Table 2). The sum of the public and private spheres –the public and what we would call its environment- would constitute the ‘social space of the sphere’, in the sociological sense [

80,

81,

82]. In the Barrios Altos, this social space is made up of both the main plazas and the stepped housing access and shared spaces and potential pedestrian streets (

Figure 9), and for it to function as a network it must integrate the diversity of types of places, mix and promote diverse relationships, social engagement and appropriation of space.

4.2. Environmental Network

The representation of the environmental structure is twofold: registration of the urban-ecological elements and consideration of a logic for future projection of the identified systems. A cartographic identification of open spaces with a capacity for ecosystem function and citizen use is carried out. For this, existing internal free spaces and of contiguous areas are selected: plazas, parks, wooded spaces inside public or private property, as well as the Santa Catalina Castle Forest Park. Empty lots inserted in the urban fabric are also considered due to their potential for temporary use and the urban axes or itineraries that articulate the points and areas, ‘spots’ of the environmental structure [

83]. A deficit of neighborhood green space is observed, with the quota of m2 per inhabitant well below the average of the nucleus, and difficult access to nearby green spaces.

Improvement of ecological connectivity is based on the fabric´s potential to form a network of recreational or landscaped green spaces connected through itineraries and/or sequences of public space, which also represent a functional alternative to commuting in a private vehicle [

40] (

Figure 10).

The environmental network seeks to improve integration of vulnerable neighborhoods in their urban and geographical environment, forming a larger scale ecosystem mesh that links the different areas beyond specific socioeconomic circumstances, rethinking the city as an artificial ecology, a deeper ecology that questions the broader issues of natural and urban environments while encompassing structure, function, and change [

84]. The environmental network would thus qualify, once again, the tissues deficient in green space, identifying opportunities within its own features, typologies of spaces that assume the environmental role.

One of the main challenges is to eliminate the urban edge condition, which deepens the stigmatization of these neighborhoods. We propose to adapt the hillside of the Castle as a public space, forming part of the network of green spaces in the city. Other important actions of the environmental network are: (1) to provide urban centrality to the ring road -access to the Barrios Altos at its upper level-, transforming the road into a ‘long square’ with more public seating areas and citizen representation; and (2) create a ‘collective spaces’ system that could constitute a kind of disseminated Environmental Classroom, using the unused lots and spaces in the plot as new green spaces.

4.3. Urban Network

Current physical conditions manifest habitat degradation problems (

Table 2), both in the area’s central public space (

Plaza Santiago), and in buildings in neighborhoods with heritage value (

La Magdalena and Judería). There is also a deficit of basic equipment inside the area and in nearby positions, the result of the difficulties of the neighbor-hood to insert them and the obsolescence of an historic urban fabric. Physical degradation is closely related to symbolic stigmatization and increased social vulnerability, so it is essential to improve conditions and reinforce the identification of spaces for social interaction to en-hance the social capital of these neighborhoods.

Therefore, we pursue a readjustment of hierarchies in the urban space that allows the construction of an order of urban centralities, multiplying the functional possibilities of the city corners. The idea is to make the city a true articulated and interdependent space that facilitates the interaction of people and activities. In degraded areas, requalification strategies are necessary, but it is most important to re-signify the urban form to make it legible: identify a central structure that recognizes the axes and nodes of collective function and readjusts existing areas, what Gouverneur [

85] calls ‘informal supports’.

In the case study, buildings dedicated to collective activity, the city-scale facilities are identified; main axes of commercial activity are also located, obtaining the distribution of collective functions (

Figure 11).

The complementarity of the mobility system is studied by locating urban bus stops and car parks. To form the network structure, ‘street sequences’ are formulated that connect these activities and the modal transport interchange points, completing the network with new spaces for collective activity that reinforce the existing centralities; new sources are generated that extend the reach of the network and increase the connectivity of the interior of the neighborhoods with the rest of Jaén.

5. Discussion

In the studies carried out, both systemic and particular conclusions are deduced that, when identified in broken down solutions, detect common objectives and lines of argument that reveal overlapping facets of the public space network: attributes derived from the relationships between activity and urban form, the geography and culture of the place, capacities to produce new meanings and uses over a period of time, and the dynamism of places to adapt and transform [

86].

Some consequences of applying superimposed relationships at different scales and themes are: 1) the construction of a continuous public space, which links a diverse range of spaces; 2) attention to the contour of the space, and also by extension of its urban environment (more strategic urbanism and less based on design); and 3) the integration of different urban systems and functions in the urban space project (commercial and residential uses, collective functions, etc.).

Once the problems have been identified and the cartographic methodology that reveals the opportunities of the network project has been developed, an interpretation is made based on the policies and measures necessary to articulate the regeneration dynamics of the vulnerable areas studied, all with the aim of improving the physical and social capacities of the neighborhoods (

Table 4). The proposed planning mechanisms, appropriate to the socioeconomic structure of the area, would implement the network strategy. For this, each measure is defined according to its objectives and according to ‘where to intervene’, ‘how to intervene’ and ‘when’ in order of priority (low, medium or high).

6. Conclusions

Urban Links for a More Dynamic and Cohesive Future

The methodology used is what Dematteis would call a ‘new and changing geography of urban territorialities’ [

87] (p. 54), formed by a triple network: social, environmental and urban, capable of understanding the current situation and plan in the sustained socioeconomic crisis, which is a fact in the Andalusian context and specifically in inland cities such as Jaén if we take into account the trend in socioeconomic indicators in recent years [

88]. Its configuration allows the improvement of the space, the environment and the social landscape from citizen participation and interaction, with the collaboration of both public and private economic sectors.

The close link between the configuration of collective spaces and the social behavior of its users leads to a reticular vision of the structure of common places –everyone’s space-, as a materialization of the socioeconomic networks themselves. It is committed to a project that is connected and multiscale in conception [

10], with the aim of improving functionality, diversity, and intensity with respect to the traditional perception of historical areas. As well as networks, social relations, collaboration, and social cohesion are important for urban regeneration because the social relationship is related to the actors and partners involved in projects and initiatives [

25]. However, the formulation and configuration of networks and the consideration of their multidimensionality are essential starting points.

To configure the social space network, central nodes or corners are established equally in the territory, strengthening the existing ones, or creating new ones that generate renewed links to reinterpret the urban structure [

73]. These ‘nodes’ of the urban system must be articulated within the main structure, reflecting on, and defining measures that ensure accessibility, diversity and flexibility while strengthen proximity networks that contribute to improving urban and social cohesion [

38]. As Maloutas and Pantelidou also pointed out, the idea today would still be ‘how to exploit the potential for change towards a more egalitarian future, within the limits of the existing socio-political system, involving civil society as much as possible in the process’ [

89] (p. 451).

On the other hand, the usefulness of gathering large amounts of information on the state, form and pre-existing processes is highlighted, systematizing it in the exposed networks, as a source of knowledge to find a repertoire of simple solutions, broken down into minor necessary actions, combined, but at the same time independent of each other. The production of an urbanism that delves into multi-scale and multi-temporal relationships, manages to set a series of priorities and locate ‘key demands’ for the present moment and space.

As Montgomery establishes, what is important would be to develop not only an understanding of cultural neighborhoods, but also resilience strategies, and put them into practice as a paradigm of urban regeneration. The prospective cartographies of future thematic networks are supposed to be used as an argumentative instrument as well as a methodological one: the park itineraries, integrated environmental classroom, collective fabrics network, among others. On one hand, the multidimensional networks will help to integrate social, economic, architectural and/or patrimonial. On the other hand, going beyond the production of specific urban designs, they will foster the consolidation of open systems that lead to the establishment of new positive relationships to reinforce social cohesion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.R-N. and B.B-R.; methodology, J.L.R-N. and B.B-R.; software, B.B-R.; validation, J.L.R-N.; formal analysis, J.L.R-N. and B.B-R.; investigation, J.L.R-N. and B.B-R.; resources, J.L.R-N. and B.B-R.; data curation, J.L.R-N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.R-N. and B.B-R.; writing—review and editing, J.L.R-N.; visualization, J.L.R-N.; supervision, J.L.R-N.; project administration, J.L.R-N.; funding acquisition, B.B-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in its final period of 2023-2024 by the research project “EQUISOCIAL. Evaluation of the factors of integration and social cohesion of urban facilities. Urban design criteria”, UGR.22-10, funded in turn by the Consejería de Fomento, Articulación del Territorio y Vivienda (Junta de Andalucía), and developed in the Department of Urban Planning of the School of Architecture of the University of Granada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Official College of Architects of Jaén and the Urban Planning Manager, Manuel Rodrguez, for their support in holding the urban planning competition for the revitalization of the Historic Center of Jaén, obtaining the first prize, which gave rise to the line of research that culminates in this text. We would also like to thank our research team, who contributed at various stages of the work: M. Mar Cuevas, Ana Alfaro, Carolina Curiel, A. David Gallego, and J. Antonio Catena. We would also like to thank the many people who have helped facilitate this research project, including students from workshops held at the University of Granada and many residents from the city’s various Barrios Altos, for their kindness, interaction with us, and points of view that have nourished the case study’s social approach.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prada-Trigo, J. Espacios vulnerables, crisis y ‘post-crisis económica’: trayectoria y persistencia a escala intraurbana. Scripta Nova. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, J.; Dionisio, M.R. Flexible spaces as a ‘third way’ forward for planning urban shared spaces. Cities. 2017, 70, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, C. Polítiques integrades de desenvolupament urbà sostenible per a la governança urbana: algunes lliçons tretes de les experiències europees. In Urbanisme i barris en dificultats. El cas de la Mina [Urban planning and neighborhoods in difficulty. The case of the Mine], Sodupe, M.; Ed.; Fundació Carles Pi i Sunyer d’Estudis Autonòmics i Locals: Barcelona, 2004. Ed.; Fundació Carles Pi i Sunyer d’Estudis Autonòmics i Locals: Barcelona.

- Gutiérrez, A. La iniciativa comunitaria Urban como ejemplo de intervención integral en barrios periféricos con dificultades. Una lectura a partir del caso de Clichy-Sous-Bois/Montfermeil (Île-de-France). Ciudades. 2010, 13, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, E.; Merinero, R. Desarrollo urbano integral: orientaciones metodológicas para el diseño de políticas públicas en barrios. Ciudad y Territorio. Estudios Territoriales (CyTET). 2012, 44.173, 445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Matesanz, Á.; Hernández, A. Evolución de los parámetros del enfoque integrado en las políticas de regeneración urbana en los barrios vulnerables en España. Gestión y Análisis de Políticas Públicas. Nueva Época. 2018, 20, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, J. Espacio público y espacio político. La ciudad como el lugar para las estrategias de participación. Polis 2008, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Hamilton, V.; Montarzino, A.; Rothnie, H.; Travlou, P.; Alves, S. Greenspace and quality of life: a critical literature review. Greenspace Scotland Stirling. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Research. Benefits of green infrastructure. Report to Defra and CLG. Forest Research, Farnham. 2010. Available online: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/publications/benefits-of-green-infrastructure (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Mandeli, K. Public space and the challenge of urban transformation in cities of emerging economies: Jeddah case study. Cities. 2019, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Elmlund, P.; Farrell, K. Implementing the new urban agenda: The central role of public space. Urban Des Int. 2019, 24.1, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Report on the World Social Situation 2003. Social Vulnerability - Sources and Challenges. Department of Economic and Social Affairs: United Nations, Nueva York, 2003. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/rwss/docs/2003/fullreport.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- European Commission. Partnership with the Cities. The URBAN Community Initiative; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bruquetas, M.; Moreno, F.J.; Walliser, A. La regeneración de barrios desfavorecidos. Laboratorio de Alternativas: Madrid, 2005.

- Egea, C.; Nieto, J.A.; Dominguez, J.; González, R. Vulnerabilidad del tejido social de los barrios desfavorecidos en Andalucía. Análisis y potencialidades. Centro de estudios Andaluces: Sevilla, 2008.

- De Gregorio, S. El desarrollo de las iniciativas comunitarias URBAN y URBAN II en las periferias degradadas de las ciudades españolas. Una contribución a la práctica de la regeneración urbana en España. Ciudades. 2010, 13, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, J.; Camacho, J.; Hernández, A. La vulnerabilidad urbana en España. Identificación y evolución de los barrios vulnerables. Empiria. Revista de metodología de ciencias sociales. 2013, 27, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temes, R. Valoración de la vulnerabilidad en las áreas residenciales de Madrid. EURE. 2014, 40.119, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.; Diez, A.; Matesanz, Á.; Córdoba, R.; Rodríguez, I.; Sánchez-Toscano, G.; Álvarez del Valle, L.; Informe sobre otros Observatorios de la Vulnerabilidad Urbana y su vinculación con las políticas urbanas de regeneración de barrios en Europa y España. Monografía (Informe Técnico). MTMAU and Instituto Juan de Herrera: Madrid, 2020. Available online: http://oa.upm.es/66041/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Jenks, M.; Burton, E.; Williams, K. (Eds.) The compact city: a sustainable urban form? Routledge: London and New York, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C.; Watkins, D. Social Sustainability and Urban Form: Evidence from Five British Cities. Environment and Planning A. 2009, 41, 2125–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R.; Keivani, R.; Brownill, S.; Butina Watson, G. Promoting Social Sustainability of Urban Neighbourhoods: The Case of Bethnal Green, London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2022, 46, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieian, M.; Mirzakhalili, M. Evaluation of social sustainability in urban neighborhoods of Karaj city. International Journal of Architectural Engineering and Urban Planning. 2014, 24, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, S. Neighbourhood Density and Social Sustainability in Cities of Developing Countries. Sustainable Development. 2011, 19.3, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, Y.D.S.; Prim, M.A.; Dandolini, G.A. Urban regeneration in the light of social innovation: A systematic integrative literature review. Land Use Policy. 2022, 113, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.A.; Santos Delgado, A.; Costa, L.A.; de Aguiar, R.R. S.; Dandolini, G.A.; Souza, J.A. Inovação social: uma gênese a partir da visão sistêmica e teoria da ação comunicativa de Habermas. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Integration of Design, Engineering and Management for innovation, 2015.

- Borja, J. La ciudad conquistada. Alianza Editorial: Madrid, 2003.

- Mingione, E. Urban poverty and the underclass. Blackwell: New York, NY, 1996.

- Musterd, S.; Murie, A.; Kesteloot, C. Neighbourhoods of poverty: urban social exclusion and integration in Europe. Palgrave: London, 2006.

- Marques, E. Urban Poverty, Segregation and Social Networks in São Paulo and Salvador, Brazil. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2015, 39, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, L. 7th Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/cohesion-report/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Castells, M. El futuro del estado del bienestar en la sociedad informacional. In Buen gobierno y política social [Good governance and social policy], Giner, S.; Sarasa, S., Ed.; Editorial Ariel: Barcelona, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Casgrain, A.; Janoschka, M. Gentrificación y resistencia en las ciudades latinoamericanas: El ejemplo de Santiago de Chile. Andamios. 2013, 10.22, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca Cladera, J. Rehabilitación urbana. Análisis comparado de algunos países de la Unión Europea (Alemania, Bélgica, Dinamarca, Francia, Italia y Portugal). Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Environment: Madrid, 1995.

- Segado-Vázquez, F.; Espinosa-Muñoz, V. La ciudad herida. Siete ejemplos paradigmáticos de rehabilitación urbana en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. EURE 2015, 41.123, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Assis, C.; Reabilitação Urbana da Mouraria. F|C Arquitectura Paisagista. 2012. Available online: http://www.fc-ap.com/trabalhos/reabilitacao-urbana-da-mouraria (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Zamora, I. (coord.). La cohesión social en América Latina. Programa EUROsociAL: Madrid, 2015, Colección Estudios No 9.

- Pascual, A.; Lozano, E.D.; Muñoz, J.M.; Parras, L.; Rodríguez, J.; Gómez, M.T.; Cortés, V.; Copete, S. Indicadores para la medición de la Cohesión social en Europa. Aplicación al caso de Andalucía. Centro de Estudios Andaluces: Sevilla, 2012.

- Ravenscroft, N.; Markwell, S. Ethnicity and the integration and exclusion of young people through urban park recreation provision. Managing Leisure. 2000, 5.3, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feria, J.M.; Santiago, J.; Iglesias, R.; Andújar, A.; Hurtado, C.; Gómez, F.; Gutiérrez, J. Ciudades inteligentes y sostenibles. Infraestructura verde y hábitats urbanos integrados. Centro de Estudios Andaluces: Sevilla, 2020.

- Seiwert, A.; Rößler, S. Understanding the term green infrastructure: origins, rationales, semantic content and purposes as well as its relevance for application in spatial planning. Land Use Policy. 2020, 97, 104785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Spatial planning for multifunctional green infrastructure: growing resilience in Detroit. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2017, 159, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda. Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, Habitat III Secretariat. United Nations, Quito, 2017. Available online: https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Parris, K.M.; Amati, M.; Bekessy, S.A.; Dagenais, D.; Fryd, O.; Hahs, A.K.; Hes, D.; Imberger, S.J.; Livesley, S.J.; Marshall, A.J.; Rhodes, J.R.; Threlfall, C.G.; Tingley, R.; Van der Ree, R.; Walsh, C.J.; Wilkerson, M.L.; Williams, N.S.G. The seven lamps of planning for biodiversity in the city. Cities. 2018, 83, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guidance on a strategic framework for further supporting the deployment of EU-level green and blue infrastructure. Commission Staff Working Document. 2022. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/green-infrastructure_en, /: Working Document. 2022. Available online: https.

- Busquets, J. Nuevas infraestructuras como forma de rehabilitación urbana. Cuadernos Unimetanos. 2008, 13, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Busquets, J. La Ciutat vella de Barcelona: un passat amb future. Ajuntament de Barcelona and Laboratori d’Urbanisme de Barcelona, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya: Barcelona, 2003.

- Borja, J.; Muxi, Z. El espacio público: ciudad y ciudadanía. Diputación de Barcelona and Electa: Barcelona, 2003.

- Carter, A.; Roberts, P. Strategy and partnership in urban regeneration. Urban Regeneration. Sage: Londres, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Public places urban spaces. The dimensions of urban design. Burlington: Elsevier Science, 2010.

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1994.

- Borja, J.; Castells, M. La ciudad multicultural. In Laberintos urbanos en América Latina; Jiménez, D., Ed.; Ediciones Abya-Yala: Quito, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, J.R. The Persistence of Segregation in the 21st Century Metropolis. City & Community. 2013, 12, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, R.; Haynes, B. (Eds.) The ghetto: contemporary global issues and controversies; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaztman, R. La dimensión espacial en las políticas de la superación de la pobreza urbana. Cepal: Santiago de Chile, 1999.

- Lang, J. Urban Design: The American experience. Van Nostrand Reinold: New York, 1994.

- Hernández, A. Calidad de vida y medio ambiente urbano: indicadores locales de sostenibilidad y calidad de vida urbana. Revista INVI. 2009, 24.65, 79–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H. Del plan al proyecto y hacia la perspectiva. In Los territorios del urbanista. 10 años (1994-2004), Font, A.; Corominas, M., Sabaté, J., Eds.; Fundació Politècnica de Catalunya: Barcelona, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Development. Indicadores Básicos de Vulnerabilidad Urbana. Análisis urbanístico de Barrios Vulnerables en España. Arquitectura, Vivienda y Suelo, Ministerio de Fomento and Instituto Juan de Herrera: Madrid, 2016. Available online: https://www.mitma.gob.es/recursos_mfom/comodin/recursos/160227_indicadores_basicos_vulnerabilidad_urbana.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Atlas de la distribución de la renta familiar. Ministerio de Economía, Comercio y Empresa: Madrid, 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177088&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976608 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Peláez, L.; Toro, M. #PROYECTOrEAcciona, #rEAvivaJaén Transformaciones efímeras de espacios públicos a través de la participación ciudadana. 2014. Available online: https://reavivajaen.wordpress.com/proyectoreacciona/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Arias, F. La desigualdad urbana en España. Ministerio de Fomento: Madrid, 2000. Available online: http://habitat.aq.upm.es/due/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda. Visor del Catálogo de Barrios Vulnerables, Observatorio de la Vulnerabilidad Urbana. MTMUA, General Directorate of Housing and Land: Madrid, 2022. Available online: https://www.mitma.gob.es/arquitectura-vivienda-y-suelo/urbanismo-y-politica-de-suelo/observatorio-de-la-vulnerabilidad-urbana.

- Ministry of Development. Royal Legislative Decree 7/2015, of October 30 [which approves the revised text of the Law on Land and Urban Rehabilitation]. Ministerio de Fomento: Madrid, 2015. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rdlg/2015/10/30/7 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Harvey, D. The urban experience; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Cities: Reimagining the Urban. Polity: Cambridge, 2002.

- Borja, J. Ciudadanía y espacio público. In Ciutat real, ciutat ideal. Significat i funció a l’espai urbà modern. (Urbanitats nº 7). Centro de Cultura Contemporánea: Barcelona, 1998.

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Reframing urban overtourism through the Smart-City Lens. Cities. 2020, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Navarro, J.L.; Bravo-Rodríguez, B.; Curiel-Sanz, C. Vinculaciones diacrónicas. Resignificando el patrimonio arquitectónico para la regeneración urbana de la Granada central. i2 Investigación e Innovación en Arquitectura y Territorio, 2022; 10.1, 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B.; Viganò, P. La ville poreuse: un projet pour le Grand Paris et la métropole de l’après-Kyoto. MétisPresses: Ginebra, 2011.

- Shane, D.G. Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual modeling in architecture, urban design, and City Theory. Wiley-Academy: Chischester, 2005.

- Bateson, G. Steps to an ecology of mind, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1972.

- Secchi, B. Un programma di ricerca. Casabella. 1983, 497, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, L. Review of Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual Modeling in Architecture, Urban Design, and City Theory, by D. G. Shane. AA Files. 2005, 52, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Angel, S. A pattern language: towns, buildings, construction. Oxford University Press: New York, 1997.

- Subirats, J.; Gomà, R.; Brugué, J. Análisis de los factores de exclusión social. Fundación BBVA, Institut d’Estudis Autonomics and Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, 2005, Working Paper, No. 4.

- Pérez, J. Acceso a la educación y factores de vulnerabilidad en las personas con discapacidad. Voces de la educación 2020, 5.10, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Seixas, J. La ciudad en la encrucijada: repensar la ciudad y su política. Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, 2014.

- Askarizad, R.; Safari, H. The influence of social interactions on the behavioral patterns of the people in urban spaces (case study: The pedestrian zone of Rasht Municipality Square, Iran). Cities. 2020, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. Sociología, 1. Estudios sobre las formas de socialización. Alianza Editorial: Madrid, 1986.

- Salcedo, J. Del concepto de espacio social. Teorema: Revista internacional de filosofía 1977, 7.3-4, 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Capital cultural, escuela y espacio social. Siglo XXI: México, 2008.

- Forman, R.T.T.; Godron, M. Landscape Ecology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: New York, 1986.

- Allen, S. Urbanisms in Plural. In Practice: Architecture Technique + Representation, S. Allen (Ed.). Second edition, Routledge, London, 2008: 49.

- Gouverneur, D. Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements Shaping the Self-Constructed City. Routledge: New York, 2015.

- Montgomery, J. The new wealth of cities. City dynamics and the fifth wave. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

- Dematteis, G. En la encrucijada de la territorialidad urbana. Bitácora Urbano Territorial 2006, 10.1, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Social Security. Informe del Mercado de Trabajo de Jaén. Servicio Público de Empleo Estatal (ed.): Madrid, 2022. Available online: https://www.sepe.es/SiteSepe/contenidos/que_es_el_sepe/publicaciones/pdf/pdf_mercado_trabajo/2023/IMT-Provincial/23-IMT--Jaen-2023--Datos2022-.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Maloutas, T.; Pantelidou Malouta, M. The glass menagerie of urban governance and social cohesion: concepts and stakes/concepts as stakes. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2004, 28, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).