1. Introduction

Santarém was one of the most important cities in late Medieval Portugal. This importance needs to be observed from many different perspectives. One of the most important was related to its cereal production capacity, which granted this urban centre the nickname of “Portugal’s barn”. Santarém could produce large quantities of cereal and its location less than 100 km from Lisbon and close to the Tagus River made it fundamental in the wider Portuguese urban strategy [

1,

2]. The centralization of cereal in communal barns only started to happen in the late 16th century [

3]. Until then cereals were kept underground in pits excavated into the bed rock. These can be found in many shapes but the most common were excavated shaped like a bag [

4], and some of them dating back to the Muslim occupation of the city (8th-12th centuries). Archaeological information obtained from many parts of the country reveals that these were located inside houses as much as on open fields. When these underground structures were out of use, independently of the reason behind it, they were filled with garbage either obtained from demolitions or just domestic refuse. Their abandonment occurred for many reasons but when some areas of the city were refurbished (construction of new roads or buildings) large areas of these storage pits were filled with domestic garbage. Although ceramics are the most abundant, all types of domestic refuse are frequently found inside.

The ceramics studied in this paper were found in some of these storage pits during an archaeological intervention made in Santarém in 2014 and they distinguish themselves from most other pottery objects due to their surfaces covered in glaze. These are what we can consider tableware. Their shapes correspond essentially to pitchers used to serve wine and can be dated (through information retrieved from archaeological stratigraphy and style) from the 13th and 14th centuries.

Although lead-glazed ceramics are common during the Muslim occupation and used in the majority of Santarém households [

5,

6,

7] and other places where Muslim communities were, these tend to disappear from the set of household ceramics in the following centuries. In 1147 the city of Santarém was conquered by Christian forces, together with many other towns in the Tagus Valley. Although political and military elites disappeared, the local population continued to live there, including potters. This continuity can be seen in their production with the continuation of the use of similar shapes and decorations. Local production of redwares is confirmed by the existence of kilns dated from the 12th and 13th centuries [

8,

9,

10]. However, this did not occur to glazed wares, which seem to disappear completely in the second half of the 12th century and first half of the 13th century. Nevertheless, these start to reappear in the archaeological context in the second half of the 13th century, although in small amounts.

The lack of published evidence of any kiln producing lead glazed wares in the Tagus region in the 13th and 14th centuries made us believe initially that all these vessels were imported from Northern Europe, an area with whom the Portuguese kingdom had commercial relations [

11]. These glazed vessels have been identified in many parts of the country but are seldom published [

12,

13,

14] and demonstrate a relation between Portugal and the Northern European markets.

Building upon the premise that these objects are imported, this paper will initially analyse a collection of such vessels unearthed in Santarém and juxtapose them with lead glaze ceramics confidently crafted in Northern European workshops. Upon noting substantial compositional disparities between the two sets of sherds under scrutiny, the proposal is to ascertain a plausible local or regional geological source for the clay deposits that provided the raw materials.

2. Archaeological Context

In 2014/2013 a large archaeological campaign was made in Santarém, taking advantage of the replacement of water and electricity infrastructures. Being a historical city it is legally mandatory that an archaeological survey is made. During the work developed both in Travessa das Capuchas - Largo António Monteiro, 22 abandoned underground storage pits were found. In Largo Pedro Alvares Cabral that number was 20. Not all of them were filled with domestic waste at the same time and that process occurred in the 13th and 14th centuries. In the Capuchas area, this certainly happened before 1415, when the Hospital dos Inocentes was built, and in Largo Pedro Alvares Cabral this action was most likely related to the construction of Igreja da Graça that started to be built in the 1380s [

15].

The commercial nature of the archaeological excavation did not allow an excavation of these underground structures, except for three cases that were only partially excavated. They presented different dimensions from the small just over 1 metre deep to the large almost 3 metres deep. Still, this allowed the recovery of hundreds of ceramic objects, most of them unglazed red earthenwares produced locally.

3. Geological Framework

The Santarém region is situated in Cenozoic formations, with ages ranging from ancient Miocene to modern Quaternary. Geomorphologically, the region is characterized by two Miocene-Pliocene plateaus with horizontally stratified layers and extensive lateral extent. These plateaus confine the Tagus River and its respective floodplains and river terraces. Detrital rocks, ranging from clayey sediments to large, rounded pebbles prevail, but locally there are lithotypes of carbonate composition or transitional nature. Various geological resources exist in the region, particularly some clayey or sandy formations with suitability for the ceramic industry, continuing in use until recent times [

16,

17].

Kaolinite-bearing formations are less common but can be found in the Pliocene complex at various points along the Lisbon to Santarém railway line. Primarily used for ceramics (whitish bodies), they have led to exploitation at the site called Fonte da Pipa, west of the Vale de Santarém railway station. Clays used to produce tiles and bricks (red bodies) are also present at various points in the region.

The provenance of ceramic raw materials and the ceramic technology employed was studied in a recent publication [

18], focused on the analysis of Islamic ceramics from the Alcáçova of Santarém. The authors collected samples from locations with historical records or of a more recent exploitation, as previously referenced for Miocene and Pliocene formations. In some cases, the authors conducted purification of the collected clays and sandy materials, providing detailed chemical and mineralogical characterization to establish the local or external origin of those Islamic ceramics. The composition of those materials is mainly quartz, illite/muscovite, and minor feldspars (K feldspars and plagioclase). Calcite and chlorite can be also present in some layers. Based on various indicators, these authors concluded that both local production and imported objects existed in the Alcáçova of Santarém. Given the highly sandy-silt (siliceous) composition prevalence, they conclude that all raw materials were treated before use. This information is, therefore, highly relevant to the present study, which seeks to investigate whether there is temporal continuity in ceramic production, based on local mineral resources and marked stylistic similarities, or if, conversely, medieval materials originate from European production centres.

4. The ceramic Sample Set – Selection Methodology

Figure 1 presents 20 sherds recovered from two underground cereal storage pits transformed into dumpsters excavated in Santarém and dated from the late medieval period (13th-14th century archaeological context). Only glazed ceramics were selected for the archaeometric analyses presented in this paper.

As

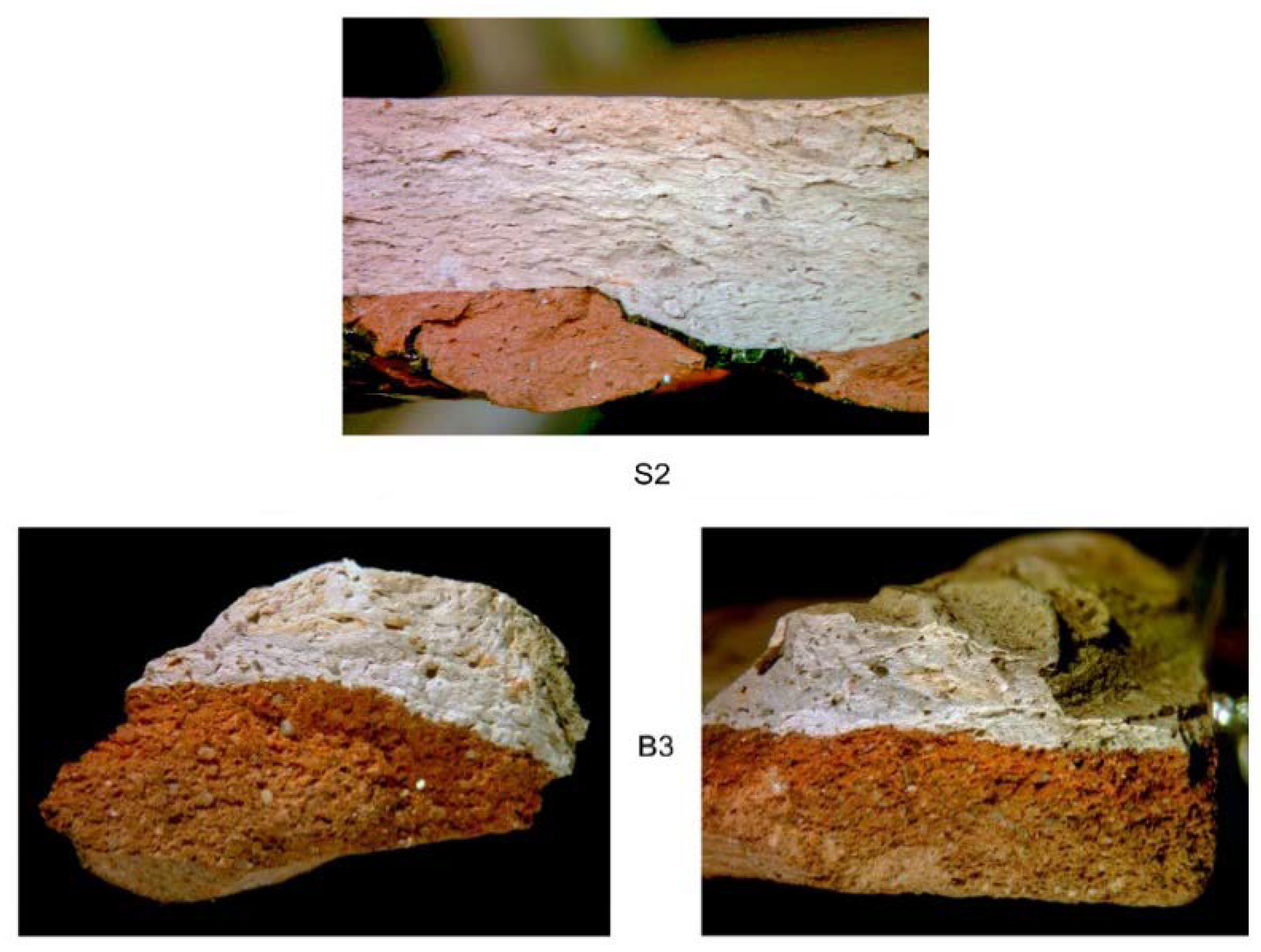

Figure 1 shows, green glazes are predominant, but some sherds exhibit amber or light brown glazes. In some cases, all sherd surfaces are glazed but there is no pigment in some areas, and the glaze simply covers the ceramic body. As it’s possible to observe through the sherd´s images, the samples can be considered quite heterogenous. Samples S1 and S2 are particularly interesting since they belonged to jugs decorated with green grapes in S1 sample and black ‘grapes’ in the case of S2. S1 exhibits a red ceramic body, while all the other Santarém samples exhibit a whitish paste. All sherds are small, not exceeding about 10 cm in the longest dimension. The exception is sherd S1 which is about 15 cm high and 10 cm large.

Previous compositional studies of pottery ceramic pastes and clay raw materials from the region of Lisbon enabled us to establish a limited number of clay sources and formulations being used in the Lisbon workshops, where most of the ceramic production in the country was located [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Pliocene ceramic pastes (highly siliceous) or Miocene ceramic pastes (with a high content of calcium carbonate) were detected [

23]. Potters settled preferentially in vicinity areas with clayey soils. We have to say however that there no evidence of kilns producing lead-glazed pottery in the 13th and 14th centuries in the Tagus Valley (where Santarém is located). The production of glazed ceramics existed in the Muslim period until the 12th century and it is again proven from the 15th century onwards [

24].

One should emphasize that in the Lisbon region, Miocene clays can be found in the North and South of the Tagus River, while Pliocene clays only exist on the South bank [

17,

21,

22,

23]. In the region of Santarém, Pliocene formations exhibit a more diversified composition, including predominantly illitic clayey facies, occasionally with calcretes (calcite bearing formations) [

18]. The only kaoliniferous formation referenced is the P1 level of kaolin sands [

16].

In other to clarify this issue many glazed (and some nonglazed) sherds from coeval European workshops were studied and a selection of 20 samples are presented in

Figure 2.

The suspicion that Santarém ceramics originated from different parts of Northern Europe is related to several factors: a) 13th and 14th century ceramic productions are not that well known and Portugal and lead glaze wares are proportionally rare in medieval collections; b) the majority of these ceramics correspond to shapes and glazes which are very similar to northern European productions; c) northern European glazed ceramics have been found in other archaeological contexts in Portugal and medieval lead-glazed ceramic production was never confirmed. When observing some of the lead-glazed ceramics found in Portugal, these objects are very similar to Saintonge, Bruges, and English productions. It is known that ceramics previously identified as Northern European ceramics in 15th century contexts were after all produced in Portugal [

25], however, during the 1400s lead glazed ceramics were produced in the country. The Santarém contexts are earlier and thus far no kiln before the 15th century is known to have produced any type of glazed ceramics.

The sherds analysed as comparative productions in this paper were obtained from different excavations in different parts of Northern Europe in sites possible to date from the 13th to the 15th century. The Saintonge Surrey-Hampshire, Kingston, and Cheam types were all found in unstratified contexts in the greater London area and were classified by pottery specialists. As for the remaining types these were obtained in Ardenne, Zomergem, and Bruges areas. They were found associated to kilns and pottery wasters thus are considered local productions [

26,

27]. The choice of these areas as comparative productions was based on two basic premises. First, this area had frequent commercial relations with Portugal in the 13th and 14th centuries [

11], and second, ceramics produced in this area are frequent finds in Portugal [

12,

13].

The Saintonge productions tend to present a light buff fabric glazed either green or dark yellow and are among the most widely distributed medieval glazed ceramics in Northern Europe [

28]. The red fabric objects are usually glazed in green and are believed to be produced in the Bruges area (or Netherlands) [

29,

30]. Finally, there are some objects that, by their characteristics, seem to have been produced in the Britain [

31].

Our archaeometric study of the glazed pottery found in the archaeological sites of medieval Santarém dated 13th to 14th century are in this context the first ones for such medieval glazed ceramics and becomes particularly interesting to know if they were locally produced or imported pottery.

5. Experimental Techniques under Use

Micro-Raman and Ground state diffuse reflectance absorption spectra spectroscopy (GSDR), stereo-microscopy (SM) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for glazes are non-invasive spectroscopies, while (XRF) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses of the ceramic bodies imply the use of ca. 10 to 15 mg of each sherd. This amount is negligible, and these two techniques can be considered as quasi-non-invasive methodologies.

Micro-Raman investigations were carried out employing a Renishaw InVia Confocal Raman equipment in a back scattering configuration, using a 532 nm laser excitation.

GSDR experiments were conducted employing a home-built diffuse reflectance set-up, using an ICCD as detector and a W-Hal lamp as the excitation source. Three standards: Spectralon white and grey disks, and barium sulphate powder were used to obtain the reflectance curves and from them the remission function was calculated.

For elemental composition information on the studied ceramic bodies and glazed surfaces, XRF analyses were performed using a Niton XL3T GOLDD spectrometer from Thermo Scientific.

To study the mineralogical and phase composition of the ceramic bodies of the sherds XRD analyses were conducted utilizing a Panalytical X’ PERT PRO diffractometer system equipped with a copper source.

In the stereo microscopy (SM) experiments tile section´s captions were observed using a Nikon SMZ645 stereomicroscope and representative images were acquired using a Moticam 10.0MP digital camera.

Further details regarding all these techniques were previous described in [

20,

21,

22].

6. Results and Discussion

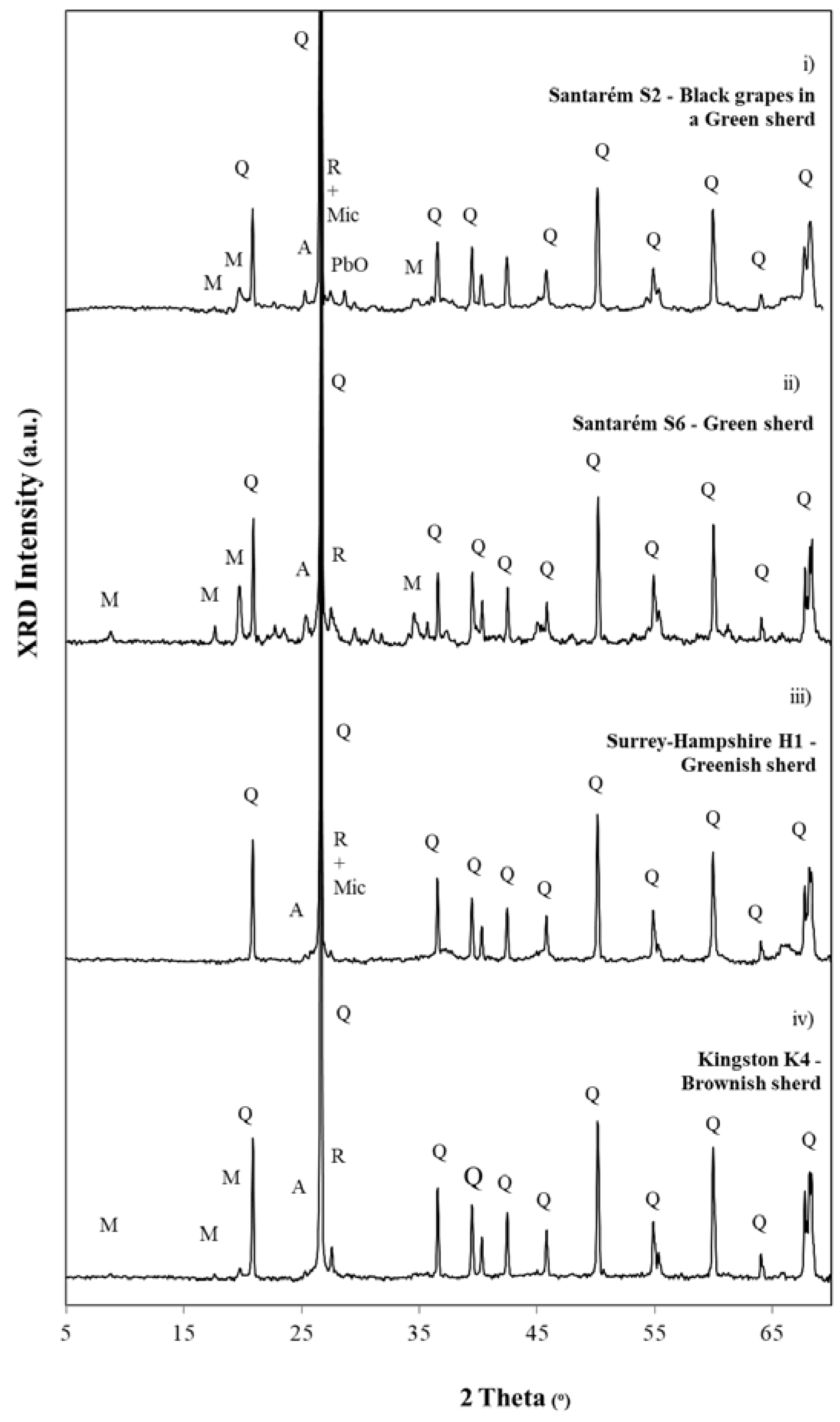

6.1. Micro-Raman Studies

Micro-Raman spectroscopy is an excellent technique to identify the pigments used to decorate the surface of the glazed ceramic and to characterize the glaze itself [

32]. All the white paste ceramics were made with highly siliceous clays, therefore

quartz was detected in many samples. In the white pastes, most samples exhibit

anatase (TiO

2) and

carbon black in the darker surfaces. As expected, the red pastes are rich in hematite, as will be further demonstrated.

As previously referred sherd S1 has dimensions of about 15 cm x 10 cm and belonged to a wine jar, common in medieval pottery. Both the body of the jar and the grapes are covered with a green glaze, and it interesting to point out that no specific copper signature (Cu

2+) was detected in the Raman spectrum of S1. The green colour of the lead-based glaze is certainly obtained with the use of a copper oxide, as XRF data presented later in this paper for glazes will show. However, no Raman signature was detected because Cu

2+ is dissolved in the matrix as pointed out in previous publications [

33,

34].

Sherd S2 probably was also from a wine jug, in this case decorated with black grapes. A large amount of

hematite (Fe

2O

3) and

magnetite (Fe

3O

4) were detected in that black decoration, as the micro Raman spectra of

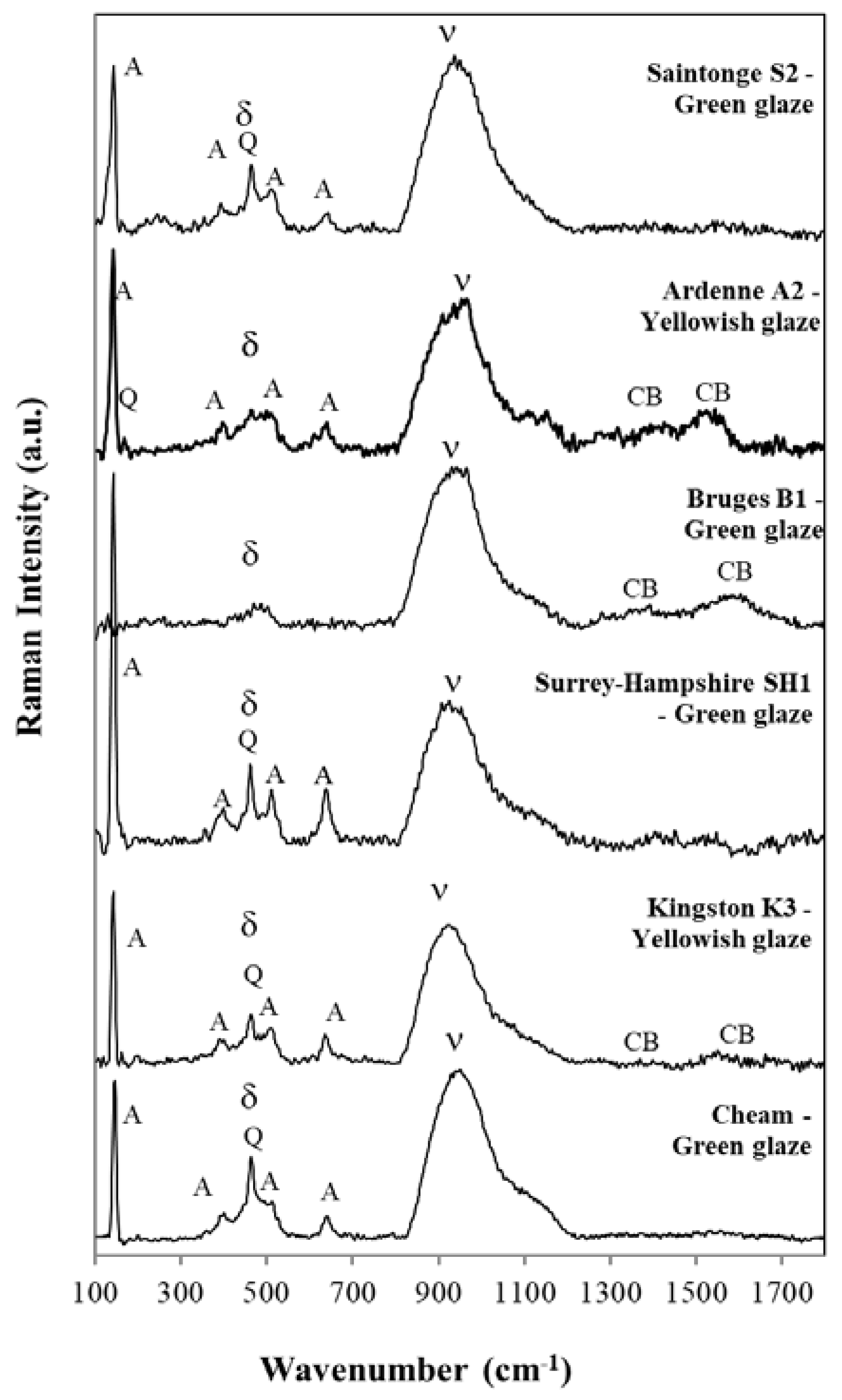

Figure 3(a) shows. The presence of a red paste beneath the substrate, covering the white paste, justifies the obtained results (see also Figure S1).

In samples S2 and S4 from Santarém a clear signature of anatase was detected, showing that this mineral is dispersed in the glaze layer that covers the surface of the pottery. Anatase and quartz were also detected in most Santarém Raman spectra of the ceramic bodies as

Figure 3(b) shows.

One should also mention that in all samples a remarkable absence of calcium carbonate, as shown

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The only exception was Santarém S6 white paste, although the amount of CaCO

3 (peaking at 1087 cm

-1) was certainly very low. The residual presence of calcite can be attributed to secondary calcite formed during burial, through impregnation or alteration of primary ceramic components, with the latter hypothesis being less likely, as will be shown subsequently using other methodologies.

The micro-Raman spectroscopy was also used to obtain information about the nature of the glaze, even establishing correlations with the firing temperature of the kiln. Quartz is a crystalline form of SiO

2 and in glassy structures part of the covalent bonds between the SiO

4 tetrahedra are destroyed. The ratio of the stretching (i.e., ~1000 cm

-1) and bending (~500 cm

-1) Raman envelopes can be correlated to the temperature of the kiln, the glaze composition and the different fluxing agents. Colomban introduced a quantification using a ratio of band areas I

p =A

500/A

1000, where I

p is the polymerization index [

32]. Santarém glass types are lead-rich glazes with I

p ~0.1 to 0.2, pointing to kiln firing temperatures below 700ºC.

The maximum wavenumber of the Si-O stretching bands (υ

max) for the Santarém glazes lies in the 935 to 960 cm

-1range, a value typical of lead rich glazes [

32].

Figure 3(b) shows the Raman spectra found for most ceramic bodies for the Santarém sherds. Large amounts of anatase, quartz and carbon black were detected.

A similar study was performed for the sherds of the European coeval production centers, and some significant cases are shown in

Figure 4.

A striking similarity is observed in the micro-Raman spectra of the glazes depicted in

Figure 3(a) and

Figure 4. Additionally, the Ip parameter exhibits slight variations, ranging from approximately 0.1 to 0.2. Consequently, discerning distinctive features indicative of different production centres proves challenging through this spectroscopic technique alone. No Raman spectra are presented for the ceramic bodies of the European sherds because the results are basically the same as those presented in

Figure 3 (b). To ascertain the origins of Santarém pottery conclusively, we will proceed by presenting results derived from alternative spectroscopic and visual methods or techniques.

6.2. GSDR Studies

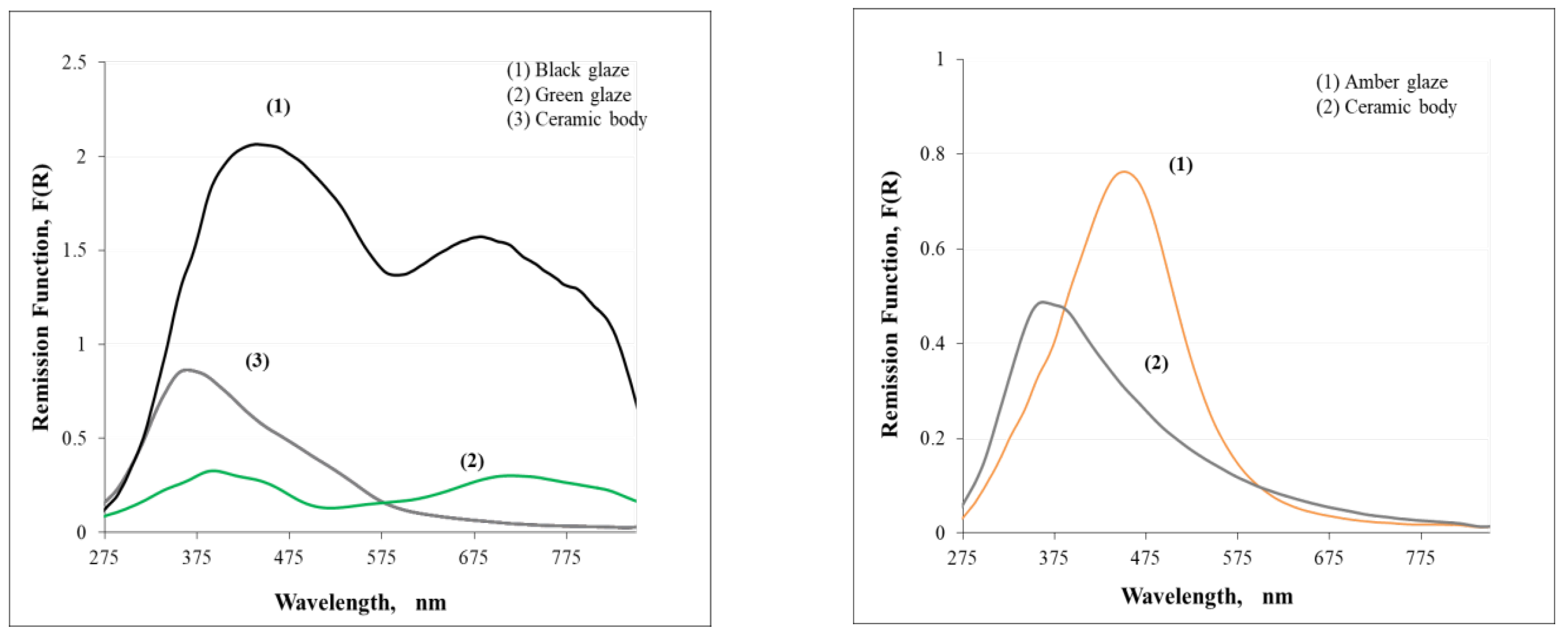

Ground state diffuse reflectance absorption spectra for all coloured sherds in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 are presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, where the Remission Function is the ordinate and the wavelength in nm is the abscissa.

Figure 5 (a) shows the absorption spectra of sample S2, the one with black grapes. The green glaze presents two maxima, one at about 380 nm and the other in the visible region, maximizing at ca. 700 nm. The absorption in the red region produces the observed green colour (the complementary colour of the red). The black grapes are characterized by a high value of the remission function both in the UV and Visible region of the spectrum. By contrast, the ceramic body absorbs primarily in the UV.

Figure 5 (b) refers to the amber colour of sample S3. An absorption band maximizing at about 470 nm is compatible with a charge-transfer transition from the ferric ion of the Fe(III)-SO

3 complex, as described in [

33,

34,

35].

The GSDR absorption spectra of

Figure 6 are like the ones presented in

Figure 5, in what regards the green and greenish glazes. The brown glaze of sherd Z1 is characterized by a broad absorption band, spreading from the UV to all visible region and maximizing at about 420 nm. K2 sherd exhibits yellow and green spots, and the absorption bands reflect the blue and red absorptions. Finally, the yellow glaze of sample St3 exhibit an absorption, in the blue region, at about 380 nm, while the creamy glaze of A2 sample absorbs in the UV and has a small broad band in the visible region.

Again, the similarity of the GSDR absorption spectra for the glazes presented for the Santarém and European sherds is remarkable and no clear differences in the production centres can be established using this spectroscopic technique.

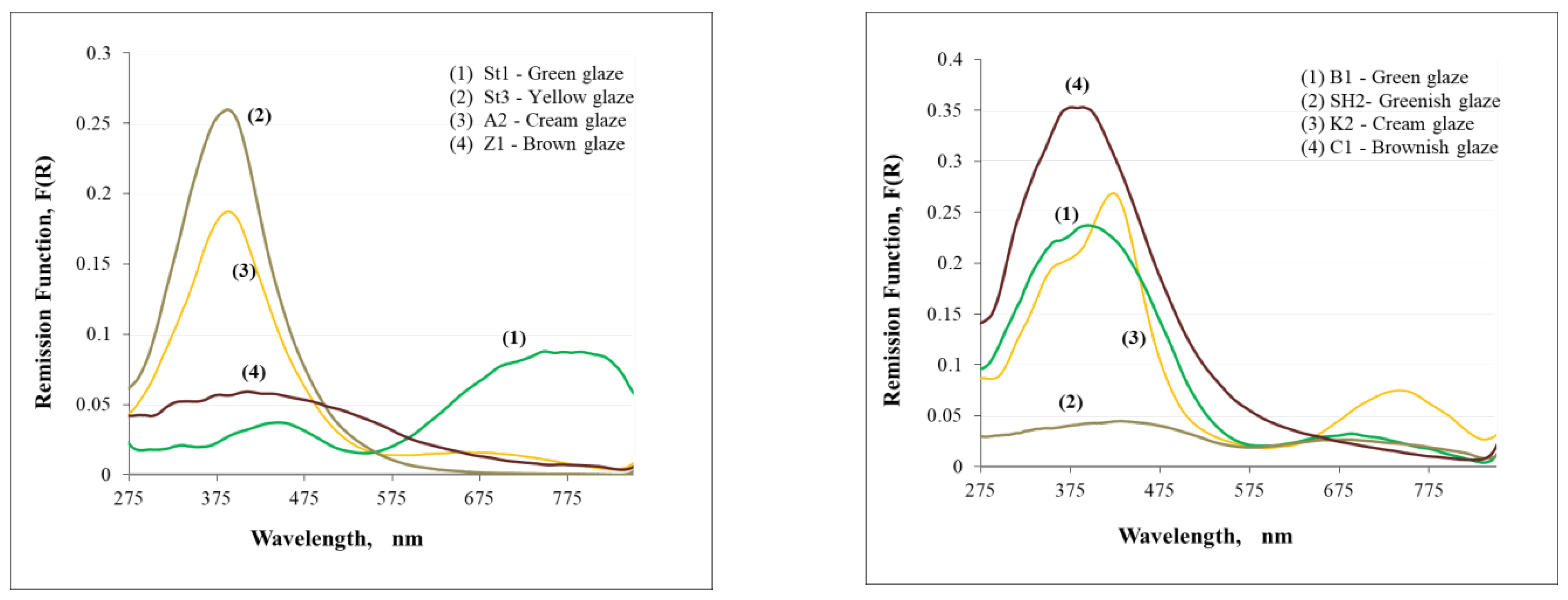

6.3. XRD Studies

The ceramic bodies retrieved from both the Santarém pits and European archaeological sites underwent comprehensive analysis using X-ray diffraction (XRD powder method). As illustrated in

Figure 7 (limited to whitish pastes), the striking resemblance between the two groups outweighs any noticeable distinctions. All pastes were crafted from siliceous raw materials, resulting in pronounced quartz (Q) signatures. Alongside amorphous/nanocrystalline phases, which XRD cannot fully characterize, a select number of minor minerals were identified, including muscovite, rutile, anatase, microcline, and plagioclase. Hematite was found only in the red pastes. Furthermore, the presence of muscovite or illite/muscovite thermal-derived phases was observed. This temperature-dependent phenomenon, primarily governed by dihydroxylation, is discernible in XRD pattern modifications, particularly evident in characteristic reflections at 2θ = 8.9 and 2θ = 19.8. These modifications facilitate the assessment of minimum kiln temperatures [

22].

(All diffractograms were normalized to the quartz peak at 2θ = 21.0 (constant intensity), to allow comparisons of the relative amounts of all the other minerals).

Table 1.

XRD main peaks used to identify the minerals in the diffractograms of all ceramic bodies.

Table 1.

XRD main peaks used to identify the minerals in the diffractograms of all ceramic bodies.

6.4. XRF studies

6.4.1. Ceramic Bodies

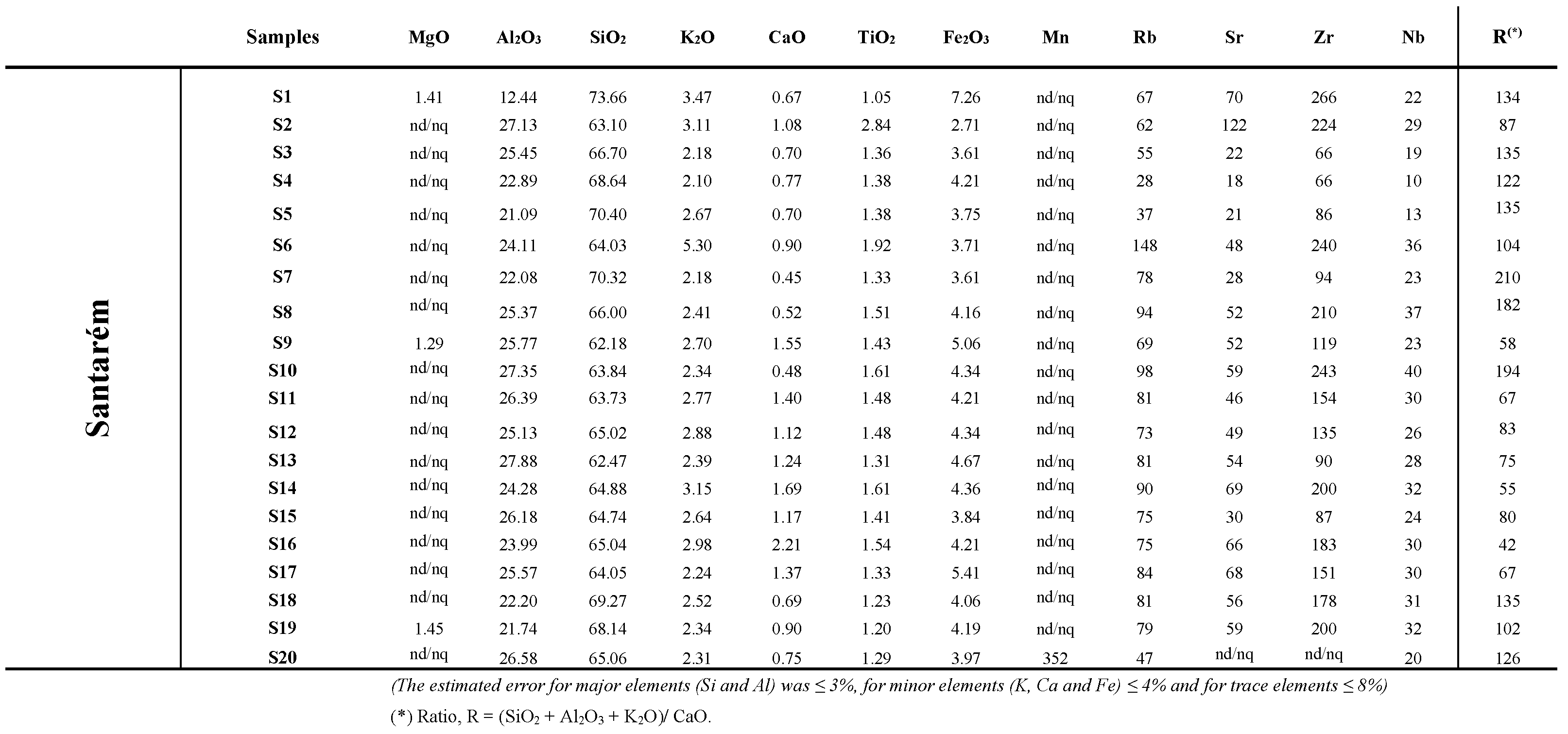

The XRF results achieved for the ceramic bodies of sherds from the Santarém archaeological site are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3 presents similar data for the European sherds.

The data included in

Table 3 and

Table 4 allow for establishing various types of ratios, commonly used for comparative analyses between materials. After an exploratory analysis of these data, it is found that one of the main ratios with discriminatory capacity among the samples under study is based on the concentration of the two main oxides, SiO

2 and Al

2O

3, to which K

2O, CaO, and Fe

2O

3 can be associated. The observed differences/trends will be directly correlated with the original formulation of the paste, where, alongside the clay components and quartz, occur the aforementioned accessory minerals. Thus,

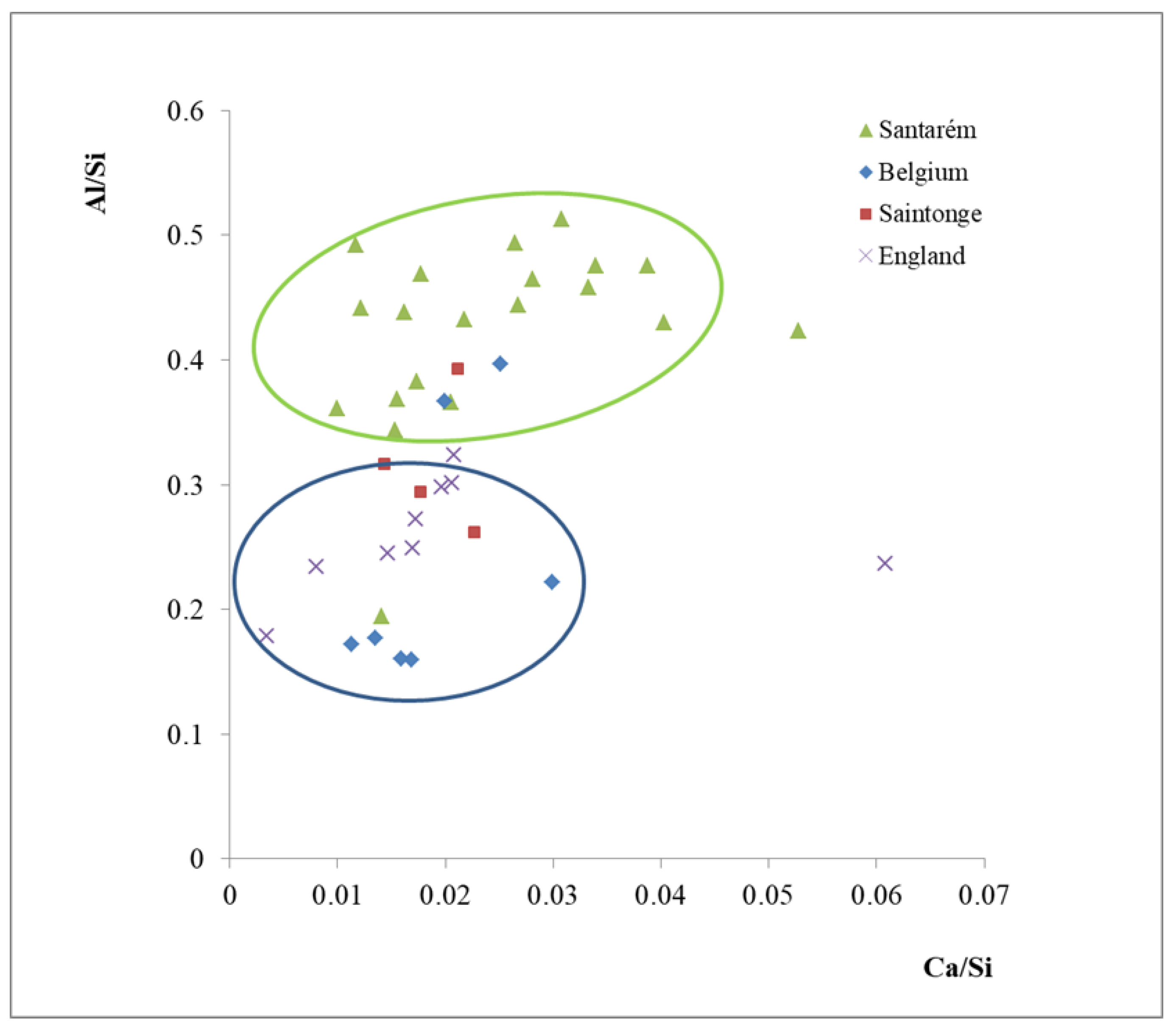

Figure 8 was selected, elaborated with the ratio Al/Si vs. Ca/Si, to describe chemically all the samples under study.

Scatterplot for Al/Si versus Ca/Si (% wt ratio) for all sherds (

Figure 8) reveals two distinct clusters, with the upper one corresponding to Santarém samples and the lower one to the European group. There are a few samples that slightly deviate from this general clustering. The Santarém sample S1, (red paste), is positioned in the group of the blue ellipse, the European one. Saintonge St1 and Ardenne A1 and A2 are included in the Santarém green ellipse. Santarém samples exhibit a distinctly higher aluminum content, while the majority of European ceramic bodies are more quartz-rich. The Ca/Si ratio shows little variability as, in general, CaO contents are very low, and according to the XRD-identified mineralogy, they can be correlated with the presence of Na-Ca plagioclase.

This finding represents the initial spectroscopic evidence definitively delineating between Santarém and European samples. All preceding findings from

Figure 8 gathered with the data of

Table 2 and

Table 3 reinforce the non-calcareous nature of the ceramic bodies, with calcium contents less than 5% wt CaO [

37,

38], aligning with the Pliocene-like origin of the clays used from the Lisbon region [

19].

Table 2 and

Table 3 present R values. R is defined by: R = (SiO

2 + Al

2O

3 + K

2O) / CaO and was used in previous papers of our group [

19,

20,

21,

22], to quantify the relative amounts of the structural components of the ceramic pastes, (SiO

2 + Al

2O

3 + K

2O), related to calcium fractions (CaO). As one could expect, all R values are characteristic of the Pliocene-like clays [

19], and no significant difference exists between Santarém and the European cases.

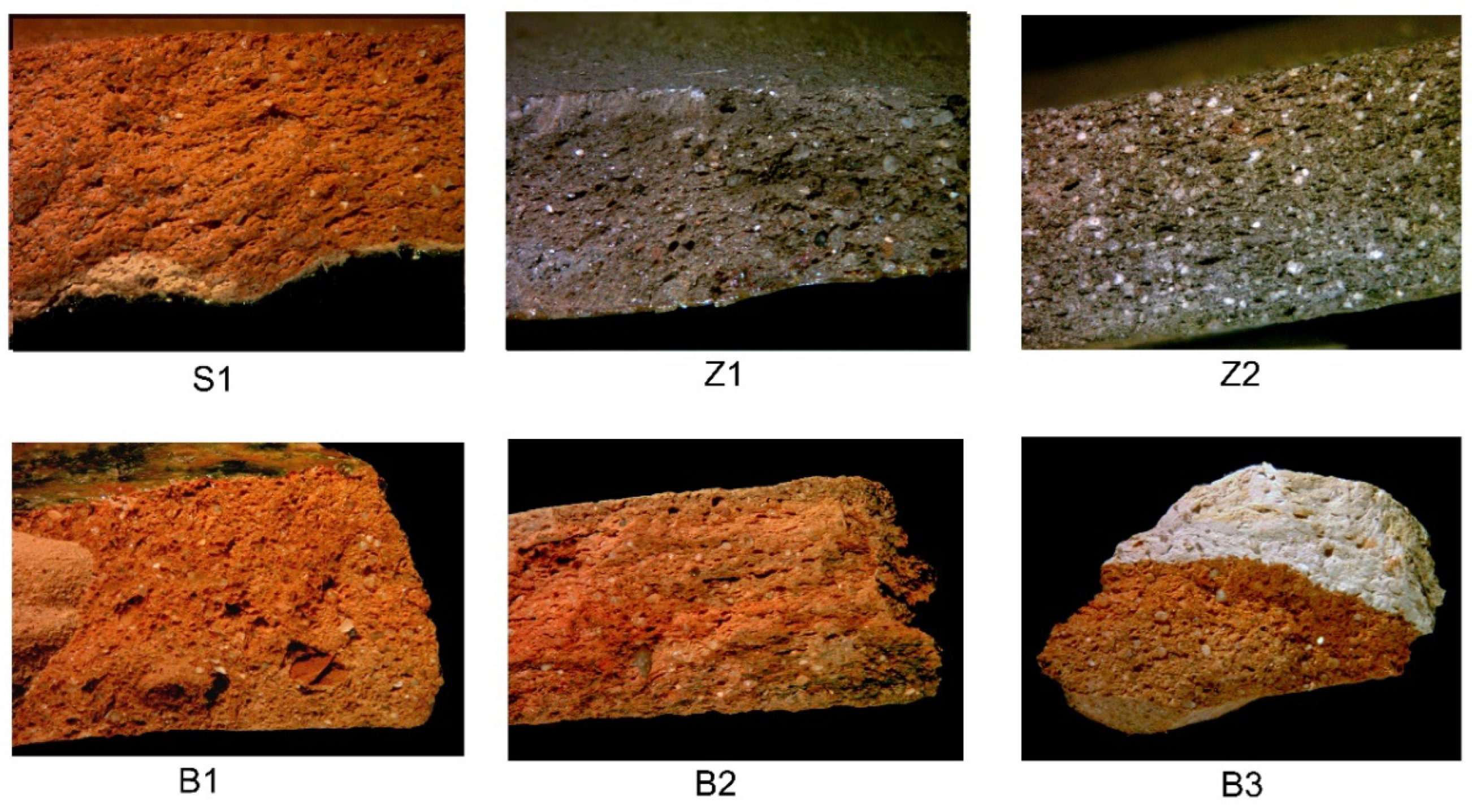

Figure 9 depicts samples S1 (red paste) from Santarém and Belgium (B1, B2, and B3 from Bruges - red pastes and Z1 and Z2 from Zomergem - grey-brown pastes). These pastes are represented in the lower section of

Figure 8, exhibiting notably low Al/Si and Ca/Si ratios. All of them demonstrate a higher iron content (7-9% wt.). This aspect clearly indicates that Belgian pastes have a markedly distinct formulation from the other light-coloured pastes from Santarém. The similarity in chemical composition between sample S1 and the other coloured paste samples suggests a common origin. This aspect will be further evaluated by also considering the data from the ceramics fabric.

6.4.2. Glazes

XRF results for glazes are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5. As mentioned before, all glazed sherds have a non-opacified (transparent) lead glazes [

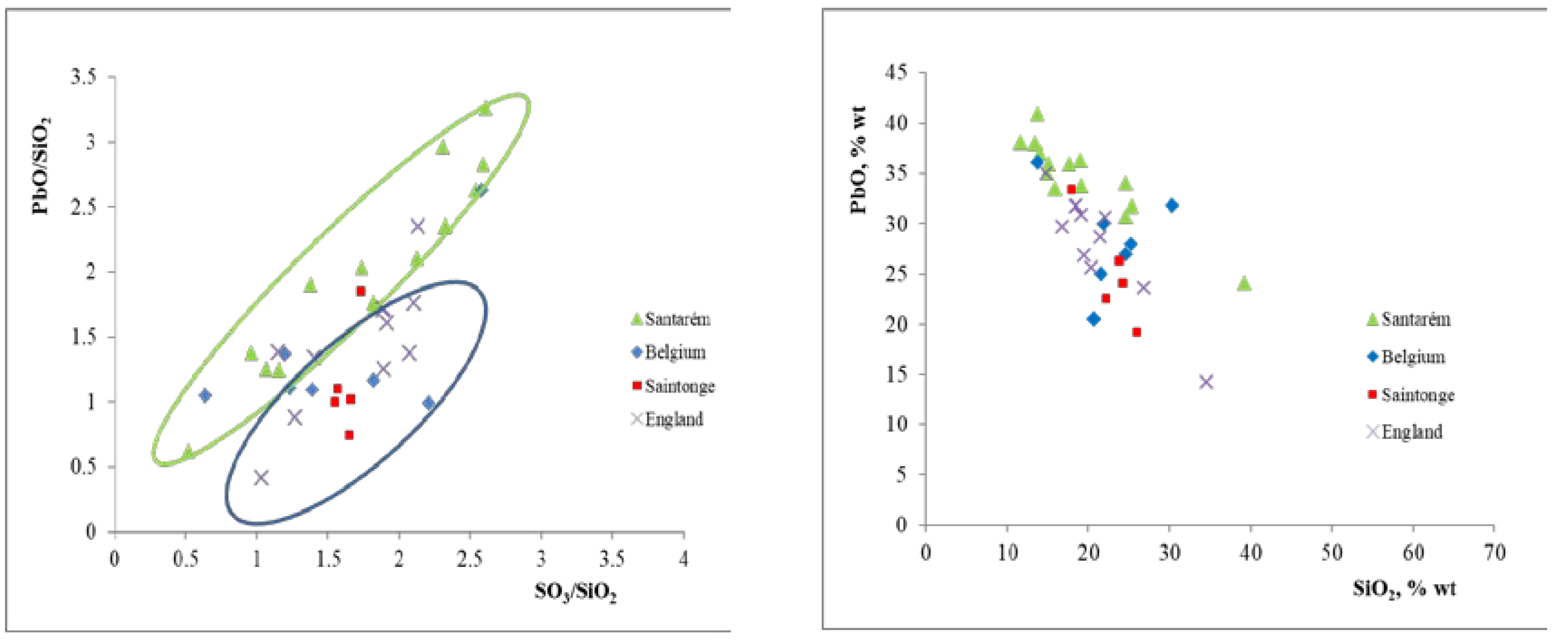

39], and, for most samples, the PbO content of the Santarém samples (~35 % wt.) is higher than the European one (below 30 % wt.), as the green ellipse of the biplot presented in

Figure 10 (a) indicates. The PbO/SiO

2 ratio is also different for the two groups, pointing to different technologies in the glaze manufacturing process.

Table 4.

Chemical composition of the glazed surfaces of Santarém sherds obtained by XRF, wt.% (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

Table 4.

Chemical composition of the glazed surfaces of Santarém sherds obtained by XRF, wt.% (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

| |

Samples |

Colours |

MgO |

Al2O3

|

SiO2

|

SO3

|

K2O |

CaO |

TiO2

|

MnO |

Fe2O3

|

NiO |

CuO |

ZnO |

As2O3

|

SnO2

|

PbO |

PbO/SiO2

|

| Santarém |

S1 |

Green |

nd/nq |

4.79 |

13.78 |

31.79 |

0.29 |

nd/nq |

0.19 |

0.19 |

0.77 |

0.03 |

2.56 |

0.34 |

4.32 |

0.10 |

40.84 |

3.0 |

| S2 |

Green |

nd/nq |

6.84 |

24.66 |

23.72 |

1.20 |

2.60 |

0.26 |

0.17 |

0.32 |

0.05 |

2.38 |

0.01 |

3.71 |

0.15 |

33.94 |

1.4 |

| Black (grape) |

nd/nq |

6.77 |

24.67 |

28.50 |

0.84 |

1.37 |

0.21 |

0.17 |

0.87 |

0.04 |

1.86 |

0.01 |

3.94 |

0.11 |

30.64 |

1.2 |

| S3 |

Amber |

nd/nq |

6.06 |

13.46 |

34.91 |

0.23 |

nd/nq |

0.03 |

0.18 |

2.86 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

4.24 |

nd/nq |

37.95 |

2.8 |

| Brown (scratch) |

nd/nq |

6.24 |

14.08 |

35.72 |

0.28 |

nd/nq |

nd/nq |

0.18 |

2.92 |

0.07 |

0.06 |

nd/nq |

3.45 |

nd/nq |

37.00 |

2.6 |

| S4 |

Amber |

nd/nq |

6.27 |

15.22 |

35.45 |

0.33 |

nd/nq |

nd/nq |

0.18 |

2.95 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

3.62 |

nd/nq |

35.89 |

2.4 |

| Brown (scratch) |

1.91 |

6.02 |

14.97 |

34.72 |

0.32 |

nd/nq |

0.02 |

0.19 |

2.90 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

3.85 |

nd/nq |

35.02 |

2.3 |

| S5 |

Green |

nd/nq |

7.07 |

25.37 |

27.15 |

0.92 |

1.19 |

0.05 |

0.17 |

0.42 |

0.05 |

2.15 |

0.02 |

3.78 |

nd/nq |

31.68 |

1.2 |

| S6 |

Green |

nd/nq |

3.49 |

11.68 |

30.47 |

0.17 |

6.97 |

nd/nq |

0.17 |

0.22 |

0.05 |

4.14 |

0.39 |

4.15 |

0.06 |

38.05 |

3.3 |

| S8 |

Green |

nd/nq |

6.08 |

19.16 |

34.94 |

0.50 |

nd/nq |

0.04 |

0.20 |

0.50 |

0.07 |

1.28 |

nd/nq |

3.55 |

nd/nq |

33.68 |

1.8 |

| S10 |

Green |

nd/nq |

6.94 |

19.08 |

26.39 |

0.76 |

4.8 |

0.05 |

0.18 |

0.69 |

0.06 |

1.23 |

0.01 |

3.49 |

0.02 |

36.26 |

1.9 |

| Brown |

1.72 |

6.42 |

17.68 |

30.77 |

0.47 |

nd/nq |

0.03 |

0.18 |

2.58 |

0.05 |

0.15 |

0.02 |

4.00 |

0.00 |

35.92 |

2.0 |

| S19 |

Green |

nd/nq |

6.08 |

39.26 |

20.41 |

0.93 |

3.57 |

0.05 |

0.16 |

0.53 |

0.06 |

1.93 |

0.01 |

2.91 |

0.03 |

24.08 |

0.6 |

The previous statement is confirmed by

Figure 10 (b) that shows the correlation between the flux, PbO, and the SiO

2 content, suggesting a linear relation between them. Indeed, the flux content is higher in the Santarém samples (the green triangles).

The brown and amber colours are obtained with the use of iron oxide, while the green coloured sherds are characterized by the presence of copper, as usual in ancient coloured glazed ceramics [

40,

41,

42].

6.5. Optical Microscopy (OM)

Given the limited variability in X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses of light-coloured ceramic pastes, suggesting similarities in the components of raw materials and firing conditions, a clear trend emerges regarding the proportion of these components. This trend becomes more evident when considering major oxides (SiO2 and Al2O3) as stated before. Despite previous evidence revealing a strong possibility of a different origin for the light clay samples from Santarém compared to European ones, a visual inspection of their manufacturing was carried out, using various parameters, to validate this assumption. Particular attention was given to European samples whose composition fell within the domain of the Santarém group or vice versa, as well as to the group of coloured ceramics, namely those made of red clay.

Figures S1 and S2 (Supplementary material) present cross-sections of Santarém samples S1 to S20 and all European samples. Tables S1 and S2 summarizes fabric pastes characteristics of all samples used in this study.

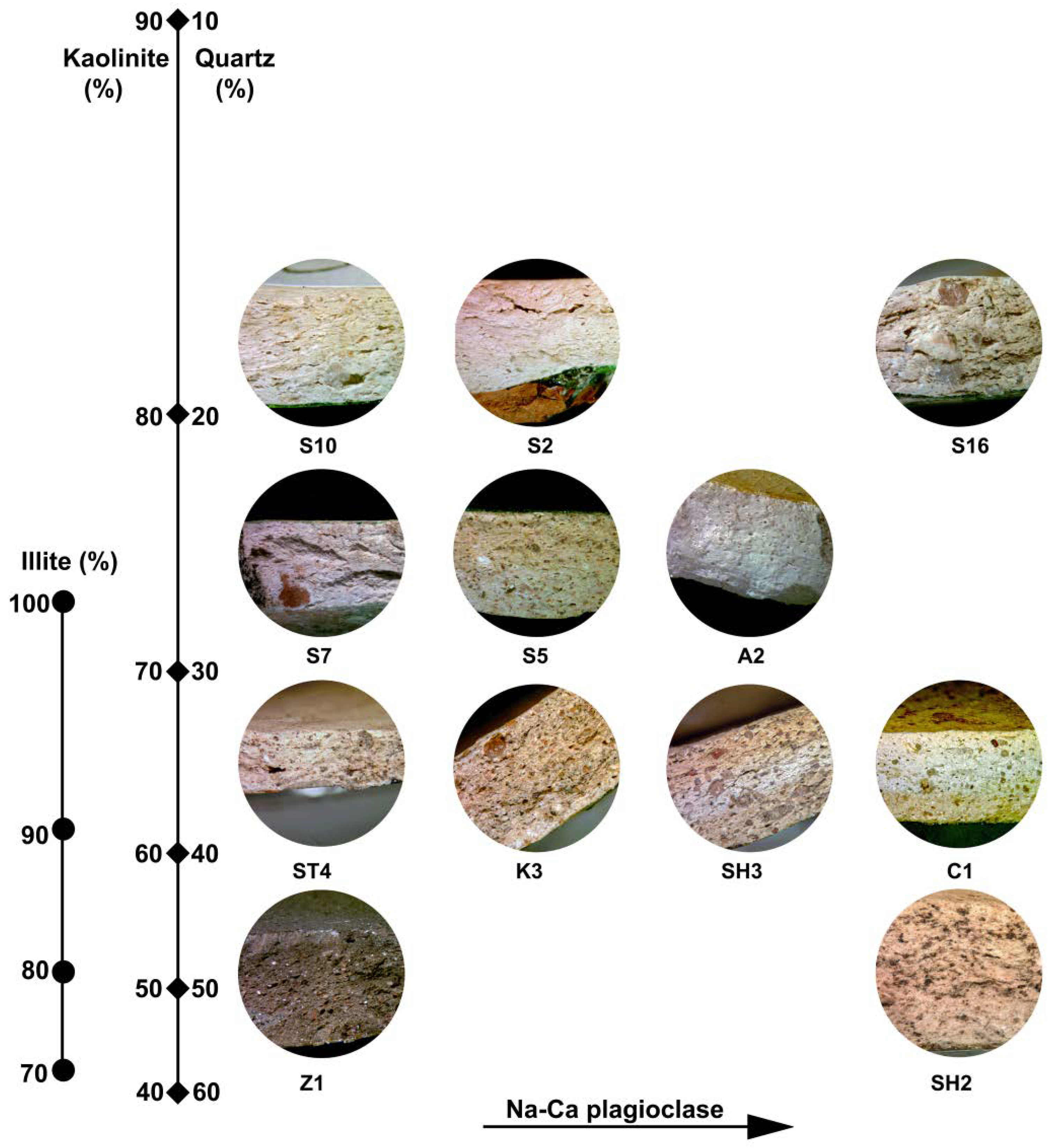

The combination of chemical data (

Table 2 and

Table 3) with the fabric analysis of the light sherds, including sample Z1, observed through stereomicroscopy, is represented in

Figure 11. Alongside the Al/Si and Ca/Si values that determined the positioning of the samples in the figure, two parallel vertical axes were placed, aiming to establish a correspondence between the ceramic and the raw material that originated it (clay-quartz mixture) for a given value of Al/Si. Given the aluminous and siliceous composition of the pastes, with a low content of K

2O, hypotheses of kaolinite-quartz and illite-quartz mixtures are considered based on their ideal chemical compositions. On the horizontal axis, we placed the slight trend of enrichment in CaO instead of the Ca/Si parameter, which, according to observations, is due to the presence of relic feldspar (Na-Ca plagioclase) in the ceramic paste (e.g., sample S16).

From top to bottom, the samples exhibit a decreasing Al2O3/SiO2 ratio (indicating they are more quartzose or siliceous), and from left to right, they show a slight enrichment in feldspar, possibly albite/oligoclase.

Visual analysis distinctly reveals that the manufacture of light-coloured pastes in Santarém is distinct from other foreign manufactures. Foreign light-coloured paste manufactures are also distinct from each other. Only the samples from SH exhibit two distinct manufactures (SH1, SH3, SH4 vs. SH2), revealing that they may have a different origin or formulation. The remaining samples show a notable origin homogeneity in both chemical composition and manufacture.

In the formulation of pastes found in Santarém, it is evident that there is control over the quantity of quartz in the paste formulation. The manufacture is globally dominated by an abundant plastic fraction, where the quartz temper is unimodal, tending to be fine, with occasional coarse grains. Some small compositional differences are observed in the content of muscovite and feldspar, still recognizable in XRD patterns and visual inspection. The overall composition suggests that the paste results from a source rich in kaolinite, where quartz is consistently present. Considering only quartz and kaolinite as paste constituents, the quartz content of Santarém light pastes varies between 15 and 30% of quartz, which is in good agreement with the visual analysis. The light color of the pastes and the actual content of quartz exclude the hypothesis of an illite-bearing source, as can be seen in

Figure 11.

The gathered information suggests that the origin of the ceramics found in Santarém are not of European import, as initially thought due to stylistic similarities. On the other hand, there are geological formations in the local area capable of providing ceramic raw materials, particularly a Pliocene or Pliocene-like formation rich in kaolinite (Pliocene sands P1 with approximately 30% kaolinite) [

16,

18].

Upon initial visual observation, the entirely red ceramics appear similar due to the abundance of quartz and similarity in manufacturing. However, there is a noticeable trend towards a greater predominance of fine and rounded quartz in the Bruges samples. Another evident aspect, observed in the two selected pastes with red and white components, is that, in the case of Santarém (S2), there is a very plastic and compact white paste, almost devoid of quartz, onto which another very plastic red paste was added, the grapes decoration. On the other hand, in Bruges, there is a coarser red paste in the interior and a more plastic and visibly porous white decorative layer.

Based on the comprehensive data collected, we can confidently assert that most identified Santarém ceramic fragments are likely of local origin. The production of light-coloured ceramics seems to have involved the utilization of clay from

Fonte da Pipa, specifically from the Pliocene formation P1 [

16], known for its kaolin-bearing sands. In the refinement process, the explored material underwent purification, with meticulous control over the temper proportion tailored to meet the specific requirements dictated by the intended function of each object. In contrast, the origins of the red ceramics appear more diverse, reflecting the multiple possibilities suggested by historical records. In this case, a more illite bearing local clay is expected [

18].

7. Conclusions

A multiple analytical approach using micro-Raman, ground state diffuse reflectance absorption and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopies, as well as the X-ray diffraction technique and stereomicroscopy allowed us to establish the mineralogical and elemental composition of the Santarém and European coeval sherds. Most techniques did not allow us a distinction between the two groups.

However, biplots of XRF data, both for ceramic bodies and glazes seems to indicate that the majority of the Santarém ceramics were most probably produced locally. This assumption is validated by the visual analysis of the paste’s fabric. Considering the results obtained, it seems possible to infer that the raw material could have been obtained from local or regional clay sources, particularly from the purification of kaolinitic siliceous sands of Pliocene type.

Late medieval imported ceramics from Northern Europe have already been identified in Porto and Lisbon. However, these were two of the most prominent cities in the kingdom of Portugal whose economy was largely based on their Atlantic ports. Santarém had no direct access to the sea and all trade was made by river navigation. This may have motivated the production of objects resembling North European ceramics. The hypothesis that some of these objects were produced locally opens very interesting paths of discussion in terms of cultural influence. As aforementioned several studies demonstrate that Muslim potters did not abandon the city and redwares continued to be made following the 8th-12th century tradition. However, the same did not happen with lead glaze wares. If made in Santarém these were made following the patterns and styles of northern European productions revealing a confluence of influences and styles that permits us to conclude that while daily used objects such as pots and pans were produced according to old traditions, glazed tableware production followed the most recent imported style.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to FCT, Portugal, for the funding of projects UID/NAN/50024/2019, UIDB/04028/2020 and M-ERA-MNT/0002/2015. The authors would like to thank Chris Jarret, Maxime Poulain for the non-Portuguese samples used in this paper.

References

- Viana, M. Alguns Preços de Cereais em Portugal (séculos XIII-XVI)”. Arquipélago. História. 2008, 12, 207-279.

- Beirante, M. Santarém quinhentista, Lisboa, Fundo de Fomento Cultural, 1981.

- Barata, F. Negócios e crédito: complexidade e flexibilidade das práticas creditícias (século XV), Análise Social, 1996, vol.XXI, 683-709.

- Rosa, S. Os silos medievais de Almada. Morfologia e dinâmicas de utilização, unpublished MA dissertation presented to NOVA University of Lisbon, 2019.

- Viegas, C.; Arruda, A. Cerâmicas islâmicas da Alcáçova de Santarém, Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, 1999, 2 (2),105-186.

- Silva, M. A Cerâmica Islâmica da Alcáçova de Santarém, das unidades estratigráficas 17, 18, 27, 28, 30, 37, 39, 41, 193, 195, 196, 197 e 210, unpublished MA dissertation, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, 2011.

- Casimiro, T.M.; Ferreira, A.F.; Silva, T.. Alfange: núcleo habitacional nos arrabaldes de Santarém em época islâmica. Arqueologia e História, 2017, 66-67, 85-96.

- Liberato, M. A cerâmica pintada a branco na Santarém Medieval: uma abordagem diacrónica séculos XI a XVI, unpublished MA dissertation, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, 2011.

- Liberato, M. A pintura a banco na Santarém Medieval. Séculos XI a XVI, in: Actas do X Congresso Internacional de Cerâmica no Mediterrâneo Ocidental, Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola, 2015, 777-791.

- Casimiro, T.M.; Boavida, C.; Silva, T.; Neves, D. Ceramics and cultural change in medieval (14th-15th century) Portugal. The case of post-Reconquista Santarém, 14724 - Medieval Ceramics 2018, 3, 21-35.

- Marques, A.O. Hansa e Portugal na Idade Média. Editorial Presença: Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P. D.; Melo, M. R.; Osório, M. I. P.; Silva, A. M.; Teixeira, R. J. Cerâmicas tardo-medievais e modernas de importação na cidade do Porto: primeira notícia. Olaria: Estudos Arqueológicos, Históricos e Etnológicos, 2004, 3, 89-96.

- Oliveira, F.; SIlva, R.; Bargão, A.; Ferreira, S. O comércio medieval de cerâmicas importadas em lisboa: o caso da rua das pedras negras n.os 21-28, in Arqueologia em Portugal / 2017 – Estado da Questão, Lisboa, 2017, 1523-1538.

- Fernandes, L.; Marques, A.; Torres, A. Ocupação baixo-medieval do teatro romano de Lisboa: a propósito de uma estrutura hidráulica, as cerâmicas vidradas e esmaltadas, Arqueologia Medieval, 2008, 8, 159- 183.

- Mendonça, I. Hospital dos Inocentes / Convento das Capuchas, 1996 http://www.monumentos.pt (accessed on February 2024).

- Zbyszewsky, G. Carta Geológica de Portugal, na escale 1/50000, notícia explicativa no Mapa 31-a – Santarém; Direcção Geral das Minas e Serviços Geológicos, Serviço Geológico de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1953.

- Lepierre, C. Estudo Chimico e Technologico sobre a Cerâmica Portuguesa Moderna. Imprensa Nacional: Lisboa, Portugal, 1899.

- Beltrame, M.; Sitzig, F.; Arruda, A.M.; Barrudas, P.; Barata, F.T.; Mirão, J. The Islamic Ceramic of the Santarém Alcáçova: raw materials, technology, and trade. Archaeometry 2021, 63, 1157–1177. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F.; Ferreira Machado, I..; Pereira, M.F.C.; Mangucci, C. Archaeometry of tiles produced in the region of Lisbon – 16th to 18th centuries. A comparison of Lisbon and Seville pastes for the cuerda seca and arista tiles. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2023, 49, 104041. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F.; Barros, L.; Ferreira Machado, I.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Casimiro, T.M. An archaeometric study of a Late Neolithic cup and coeval and Chalcolithic ceramic sherds found in the São Paulo Cave, Almada, Portugal. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2020, 51, 483-492. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F.; Barros, L.; Machado, I.; Gonzalez, A.; Pereira, M.; Casimiro, T. Spectroscopic characterization of amphorae from the 8th to the 7th c. BCE found at the Almaraz settlement in Almada, Portugal. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2018, 21, 166-174. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F.; Gonzalez, A., Pereira, M.F.C.; Santos, L.F., Casimiro, T.M.; Ferreira, D.P.; Conceição, D.S.; Ferreira Machado, I. Spectroscopy of 16th century Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware produced in the region of Lisbon. Ceram Intern. 2015, 41, 13433–13446. [CrossRef]

- Zbyszewski G. Carta Geológica dos Arredores de Lisboa na escala 1/50 000 – notícia explicativa da folha 4 – Lisboa. Serviço Geológico de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1963.

- Henriques, J.P.; Filipe, V; Casimiro, T.M.; Krus, A. By fire and clay. A late 15th century pottery workshop in Lisbon, Proceedings of the 12th International Congress on Medieval and Modern Pottery Ceramics, Athens, 2021, 41-52.

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F.; Varela Gomes, M.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Santos, L.F.; Ferreira Machado, I. A multi-technique study for the spectroscopic characterization of the ceramics from Santa Maria do Castelo church (Torres Novas, Portugal), Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2016, 6, 182-189, . [CrossRef]

- De Clercq W. ; De Groote K. ; Moens J. ; Mortier S. Zomergem. Bauwerwaan: sporen van 12de-eeuwse kleiwinning en pottenbakkersactiviteit. Monumentenzorg en Cultuurpatrimonium. Jaarverslag van de Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen 2000, 192-195.

- Vandewalle, Emiel Pottenbakkersafval van de Potterierei-Schipperskapel te Brugge. Bijdrage tot het stadsarcheologisch en regionaal aardewerkonderzoek, MA thesis, Ghent University 2020.

- Haggarty, G. A gazetteer and summary of French pottery imported into Scotland c. 1150 to c. 1650 a ceramic contribution to Scotland’s economic history Ceramic Resource Disc 3, Tayside and Fife Archaeological Society, 2006.

- Janssen H., Later medieval pottery production in the Netherlands, in Davey P.; Hodges, R. (eds.): Ceramics and Trade, Sheffield: Department of Prehistory and Archaeology of the University of Sheffield, 1983, 121-185.

- Verhaeghe, F. Medieval pottery production in coastal Flanders, in Davey P.; Hodges, R. (eds.): Ceramics and Trade, Sheffield: Department of Prehistory and Archaeology of the University of Sheffield, 1983, 63-94.

- Pearce, J. Post-medieval Pottery in London, 1500-1700, volume 1: Border Wares, Stationary Office: London, 1992.

- Colomban, Ph.; Tournie, A.; Bellot-Gurlet, L. Raman identification of glassy silicats used in ceramics, glass and jewellery: a tentative differentiation guide, J. Raman Spectrosc. 2006, 37, 841-852. [CrossRef]

- Prinsloo, L.C.; Colomban, Ph. A Raman spectroscopic study of the Mapungubwe oblates: glass trade beads excavated at an Iron Age archaeological site in South Africa. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2008, 39, 79-90. [CrossRef]

- Moncke, D.; Papageorgiou, M.; Winterstein-Beckmann, A.; Zacharias, N. Roman glasses coloures by dissolved transition metal ions: redox-reactionsw, optical spectroscopy and ligang field theory. J. Archaeological Science 2014, 46, 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Morsi, M.M.; El-serbiny, S.I.; Mohamed, K.M. Spectroscopic investigation of amber colour silicate glasses and factors affecting the amber related absorption bands. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2015, 145, 376–383. [CrossRef]

- Simsek, G.; Casadio, F.; Colomban, Ph.; Bellot-Gurlet, L.; Faber, K.T.; Zelleke, G.; Milande, V.; Moinet, E. On-site identification of early Böttger red stoneware made at Meissen using portable XRF: 1, body analysis. J. Am. Ceram. Soc 2014, 97, 2745-2754. [CrossRef]

- Tite, M. Ceramic production, provenance and use – a review. Archaeometry 2008, 50 (2), 216-231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2008.00391.x.

- Walton, M.; Tite, M.S. Production Technology of Roman Lead-Glazed Pottery and its Continuance into Late Antiquity. Archaeometry 2010, 52 (5), 733-759. [CrossRef]

- Tite, M.S.; Freestone, I.; Mason, R.; Molera, J.; Vendrell-Saz, M.; Wood, N. Lead Glazes in Antiquity – Methods of Production and Reasons for Use. Archaeometry 1998, 40 (2), 241-260. [CrossRef]

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F; Ferreira Machado, I; Gonzalez, A.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Casimiro, T.M. A new fifteenth-to-sixteenth-century pottery kiln on the Tagus basin, Portugal. Applied Physics A 2018, 124, 770. [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, G.E.; Acquafreda, P.; Masieri, M.; Quarta, G., Sabbatini, L.; Zambonin, P.G.; Tite, M.; Walton, M. Investigation on Roman Lead Glaze from Canosa: Results of Chemical Analyses. Archaeometry 2004, 46, 615-624. [CrossRef]

- Molera, J.; Ferreras, V.M.; Fusaro, A.; Esparraguera, J.M.G; Gaudenzia, M.; Pidaev, S.R.; Pradell, T. Islamic glazed wares from ancient Termez (southern Uzbekistan). Raw materials and techniques. J. Archaeological Science: Reports 2020, 29, 102169. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Glazed ceramic sherds collected from two storage pits, dated to the 13th-14th centuries, Santarém. S stands for Santarém.

Figure 1.

Glazed ceramic sherds collected from two storage pits, dated to the 13th-14th centuries, Santarém. S stands for Santarém.

Figure 2.

Glazed ceramic sherds collected from several European archaeological sites dated to the 13th-14th centuries. St - Saintonge, A - Ardenne, Z - Zomergem, B - Bruges, SH – Surrey-Hampshire, K – Kingston and C - Cheam.

Figure 2.

Glazed ceramic sherds collected from several European archaeological sites dated to the 13th-14th centuries. St - Saintonge, A - Ardenne, Z - Zomergem, B - Bruges, SH – Surrey-Hampshire, K – Kingston and C - Cheam.

Figure 3.

Micro-Raman spectra from the most significant glazed surfaces (a) and pastes (b) of the Santarém sherds. Quartz (Q), Anatase (A), Rutile (R), Hematite (H), Magnetite (M), Carbon Black (CB), Stretching (υ) and Bending (δ) of Raman envelopes.

Figure 3.

Micro-Raman spectra from the most significant glazed surfaces (a) and pastes (b) of the Santarém sherds. Quartz (Q), Anatase (A), Rutile (R), Hematite (H), Magnetite (M), Carbon Black (CB), Stretching (υ) and Bending (δ) of Raman envelopes.

Figure 4.

Micro-Raman spectra from the most significant glazed surfaces from the European sherds. Quartz (Q), Anatase (A), Rutile (R), Carbon Black (CB), Stretching (υ) and Bending (δ) of Raman envelopes.

Figure 4.

Micro-Raman spectra from the most significant glazed surfaces from the European sherds. Quartz (Q), Anatase (A), Rutile (R), Carbon Black (CB), Stretching (υ) and Bending (δ) of Raman envelopes.

Figure 5.

GSDR absorption spectra of S2 Santarém green and black glaze and ceramic body (a) and S3 Santarém amber glaze and ceramic body (b).

Figure 5.

GSDR absorption spectra of S2 Santarém green and black glaze and ceramic body (a) and S3 Santarém amber glaze and ceramic body (b).

Figure 6.

GSDR absorption spectra of European sherds: (a) St1-Saintonge green glaze; St3 - Saintonge yellow glaze; A2 - Ardenne cream glaze; Z1 - Zomergem brown glaze; (b) B1 - Bruges green glaze; SH2 - Surrey-Hampshire greenish glaze; K2 - Kingston cream glaze; C1 - Cheam Brownish glaze.

Figure 6.

GSDR absorption spectra of European sherds: (a) St1-Saintonge green glaze; St3 - Saintonge yellow glaze; A2 - Ardenne cream glaze; Z1 - Zomergem brown glaze; (b) B1 - Bruges green glaze; SH2 - Surrey-Hampshire greenish glaze; K2 - Kingston cream glaze; C1 - Cheam Brownish glaze.

Figure 7.

Representative XRD patterns for ceramic bodies of sherds from Santarém medieval archaeological site, all non-carbonaceous silicious type pastes. XRD peaks: Quartz (Q), Anatase (A), Rutile (R), Muscovite (M) and Microcline (Mic).

Figure 7.

Representative XRD patterns for ceramic bodies of sherds from Santarém medieval archaeological site, all non-carbonaceous silicious type pastes. XRD peaks: Quartz (Q), Anatase (A), Rutile (R), Muscovite (M) and Microcline (Mic).

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of Al/Si

versus Ca/Si count ratios for the studied ceramic. The contents of Al and Ca measured by XRF were normalized to the Si content [

36].

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of Al/Si

versus Ca/Si count ratios for the studied ceramic. The contents of Al and Ca measured by XRF were normalized to the Si content [

36].

Figure 9.

Selection of representative Santarém (S1, Santarém), and European red (Bruges- Belgium B1, B2, B3) and grey brown (Zomergem Z1, Z2)fabric pastes. Photos width 12 mm.

Figure 9.

Selection of representative Santarém (S1, Santarém), and European red (Bruges- Belgium B1, B2, B3) and grey brown (Zomergem Z1, Z2)fabric pastes. Photos width 12 mm.

Figure 10.

Scatterplot of PbO/SiO2 versus SO3/SiO2 (a), and PbO versus SiO2 for glazed surfaces of Santarém and European samples (b).

Figure 10.

Scatterplot of PbO/SiO2 versus SO3/SiO2 (a), and PbO versus SiO2 for glazed surfaces of Santarém and European samples (b).

Figure 11.

Selection of representative Santarém and European fabric pastes. From top to bottom quartz temper increases. From left to right, feldspar slightly increases (Na-Ca plagioclase).

Figure 11.

Selection of representative Santarém and European fabric pastes. From top to bottom quartz temper increases. From left to right, feldspar slightly increases (Na-Ca plagioclase).

Figure 12.

Selection of representative Santarém (S2 – Santarém) and European (B3 - Bruges- Belgium) red combined fabric pastes.

Figure 12.

Selection of representative Santarém (S2 – Santarém) and European (B3 - Bruges- Belgium) red combined fabric pastes.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the powdered pastes of the ceramic fragments collected in the Santarém medieval archaeological site, obtained by XRF. Data are presented as wt.% for major and minor constituents and ppm for trace elements. (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the powdered pastes of the ceramic fragments collected in the Santarém medieval archaeological site, obtained by XRF. Data are presented as wt.% for major and minor constituents and ppm for trace elements. (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the powdered ceramic bodies of European sherds, obtained by XRF. St, Saintonge; A, Ardenne; Z, Zomergem; B, Bruges; SH, Surrey- Hampshire; K, Kingston; C, Cheam. Data are presented as wt.% for major and minor constituents and ppm for trace elements. (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

Table 3.

Chemical composition of the powdered ceramic bodies of European sherds, obtained by XRF. St, Saintonge; A, Ardenne; Z, Zomergem; B, Bruges; SH, Surrey- Hampshire; K, Kingston; C, Cheam. Data are presented as wt.% for major and minor constituents and ppm for trace elements. (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

| |

|

Samples |

MgO |

Al2O3

|

SiO2

|

K2O |

CaO |

TiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

Mn |

Rb |

Sr |

Zr |

Nb |

R(*)

|

| Saintonge |

St1 |

nd/nq |

23.07 |

67.51 |

2.91 |

0.92 |

1.73 |

3.82 |

nd/nq |

64 |

63 |

170 |

21 |

101 |

| St2 |

nd/nq |

16.95 |

74.51 |

2.79 |

1.09 |

1.30 |

3.30 |

nd/nq |

43 |

203 |

210 |

18 |

86 |

| St3 |

nd/nq |

18.42 |

72.03 |

4.24 |

0.83 |

1.74 |

2.71 |

nd/nq |

46 |

55 |

149 |

20 |

115 |

| St4 |

nd/nq |

19.78 |

71.76 |

2.04 |

0.67 |

1.82 |

3.91 |

nd/nq |

40 |

38 |

168 |

19 |

141 |

| Ardenne and Zomergem |

A1 |

nd/nq |

22.22 |

69.61 |

1.12 |

0.90 |

2.69 |

3.42 |

nd/nq |

38 |

87 |

273 |

46 |

104 |

| A2 |

nd/nq |

23.53 |

68.14 |

1.24 |

1.10 |

2.67 |

3.28 |

nd/nq |

30 |

74 |

226 |

38 |

84 |

| Z1 |

1.55 |

11.27 |

73.21 |

3.37 |

0.64 |

1.08 |

8.83 |

nd/nq |

63 |

58 |

325 |

20 |

138 |

| Z2 |

1.20 |

11.09 |

74.22 |

3.16 |

0.54 |

1.05 |

8.70 |

nd/nq |

59 |

57 |

248 |

20 |

164 |

| Bruges |

B1 |

1.24 |

10.53 |

75.68 |

3.23 |

0.83 |

1.06 |

7.39 |

nd/nq |

59 |

64 |

243 |

20 |

108 |

| B2 |

1.54 |

13.46 |

69.70 |

4.23 |

1.34 |

1.25 |

8.42 |

nd/nq |

82 |

114 |

268 |

25 |

65 |

| B3 |

1.16 |

10.68 |

76.68 |

3.40 |

0.79 |

1.04 |

6.21 |

nd/nq |

50 |

60 |

221 |

16 |

115 |

Surrey

Hampshire

|

SH1 |

nd/nq |

19.90 |

70.51 |

3.41 |

0.95 |

1.35 |

3.84 |

nd/nq |

37 |

222 |

142 |

15 |

99 |

| SH2 |

nd/nq |

15.19 |

73.69 |

2.63 |

2.89 |

0.92 |

4.58 |

360 |

46 |

162 |

87 |

13 |

32 |

| SH3 |

1.14 |

18.66 |

71.11 |

3.00 |

0.95 |

1.22 |

3.85 |

nd/nq |

67 |

382 |

348 |

29 |

98 |

| SH4 |

1.28 |

15.98 |

73.63 |

2.87 |

0.80 |

1.09 |

4.27 |

nd/nq |

46 |

383 |

165 |

18 |

115 |

| Kingston |

K1 |

nd/nq |

12.45 |

80.03 |

2.00 |

0.18 |

0.88 |

4.43 |

nd/nq |

35 |

22 |

125 |

11 |

531 |

| K2 |

1.15 |

17.24 |

72.70 |

1.68 |

0.81 |

1.28 |

5.11 |

nd/nq |

33 |

39 |

126 |

20 |

113 |

| K3 |

1.17 |

15.93 |

74.62 |

2.35 |

0.71 |

1.05 |

4.14 |

nd/nq |

34 |

39 |

178 |

17 |

131 |

| K4 |

nd/nq |

15.62 |

76.53 |

2.26 |

0.40 |

1.01 |

4.14 |

nd/nq |

37 |

45 |

244 |

21 |

237 |

| Cheam |

C1 |

nd/nq |

18.67 |

71.99 |

2.53 |

0.91 |

1.40 |

4.48 |

nd/nq |

45 |

76 |

217 |

24 |

102 |

| |

|

|

(The estimated error for major elements (Si and Al) was ≤ 3%, for minor elements (K, Ca and Fe) ≤ 4% and for trace elements ≤ 8%) |

|

Table 5.

Chemical composition of the glazed surfaces of European sherds obtained by XRF, wt.% (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

Table 5.

Chemical composition of the glazed surfaces of European sherds obtained by XRF, wt.% (nd: not detected; nq: not quantified).

| |

Samples |

Colours |

MgO |

Al2O3

|

SiO2

|

SO3

|

K2O |

CaO |

TiO2

|

MnO |

Fe2O3

|

NiO |

CuO |

ZnO |

As2O3

|

SnO2

|

PbO |

PbO/SiO2

|

| Belgium |

B1 |

Green |

nd/nq |

7.03 |

21.56 |

39.20 |

0.26 |

nd/nq |

0.15 |

0.21 |

0.86 |

0.05 |

1.69 |

0.35 |

3.60 |

0.03 |

25.02 |

1.2 |

| B3 |

Yellow |

1.41 |

14.16 |

21.90 |

26.20 |

1.31 |

nd/nq |

0.07 |

0.17 |

0.88 |

0.06 |

nd/nq |

0.02 |

3.77 |

0.09 |

29.96 |

1.4 |

| A2 |

Creamy |

nd/nq |

7.36 |

20.72 |

45.81 |

0.12 |

nd/nq |

0.21 |

0.16 |

0.65 |

0.07 |

nd/nq |

1.38 |

3.03 |

nd/nq |

20.49 |

1.0 |

| Z1 |

Brown |

1.72 |

5.88 |

24.64 |

34.33 |

0.38 |

nd/nq |

0.13 |

0.15 |

2.19 |

0.06 |

nd/nq |

0.02 |

3.61 |

nd/nq |

26.88 |

1.1 |

| Saintonge |

St1 |

Green |

nd/nq |

5.08 |

23.87 |

37.46 |

0.19 |

nd/nq |

0.13 |

0.17 |

0.59 |

0.05 |

2.03 |

0.29 |

3.78 |

0.11 |

26.25 |

1.1 |

| St2 |

Green |

nd/nq |

7.36 |

18.04 |

31.28 |

0.55 |

1.35 |

0.13 |

0.23 |

1.02 |

0.05 |

2.19 |

0.50 |

3.91 |

0.07 |

33.32 |

1.8 |

| St3 |

Creamy |

nd/nq |

6.80 |

26.04 |

43.01 |

0.41 |

nd/nq |

0.15 |

0.14 |

0.57 |

0.05 |

0.34 |

0.01 |

3.29 |

nd/nq |

19.20 |

0.7 |

| Green |

nd/nq |

7.43 |

24.26 |

37.60 |

0.53 |

0.40 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.62 |

0.05 |

1.15 |

nd/nq |

3.59 |

nd/nq |

24.07 |

1.0 |

| St4 |

Green |

1.50 |

8.35 |

22.19 |

36.88 |

0.33 |

1.83 |

0.24 |

0.17 |

1.04 |

0.04 |

1.53 |

0.02 |

3.38 |

nd/nq |

22.50 |

1.0 |

| Surrey-Hampshire |

SH1 |

Green |

1.73 |

8.30 |

14.88 |

31.70 |

0.67 |

0.30 |

0.11 |

0.17 |

0.68 |

0.06 |

2.83 |

0.05 |

3.36 |

0.19 |

34.97 |

2.3 |

| SH2 |

Green |

nd/nq |

6.23 |

18.45 |

34.88 |

0.38 |

0.43 |

0.09 |

0.19 |

0.96 |

0.07 |

1.47 |

0.14 |

4.72 |

0.25 |

31.70 |

1.7 |

| SH3 |

Green |

1.57 |

10.63 |

22.17 |

25.52 |

1.01 |

1.45 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.74 |

0.06 |

2.36 |

0.01 |

3.57 |

0.03 |

30.55 |

1.4 |

| Kingston |

K1 |

Yellowish |

nd/nq |

7.03 |

19.23 |

36.86 |

0.31 |

nd/nq |

0.09 |

0.17 |

0.85 |

0.06 |

0.79 |

0.02 |

3.66 |

0.05 |

30.87 |

1.6 |

| K2 |

Green |

1.70 |

8.65 |

21.49 |

30.17 |

1.00 |

nd/nq |

0.12 |

0.16 |

0.87 |

0.06 |

3.50 |

0.48 |

3.03 |

0.12 |

28.66 |

1.3 |

| Yellowish |

1.80 |

7.57 |

26.89 |

34.17 |

0.87 |

nd/nq |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.97 |

0.04 |

0.51 |

0.08 |

3.14 |

0.02 |

23.61 |

0.9 |

| K3 |

Green |

1.87 |

7.35 |

16.84 |

35.46 |

0.30 |

nd/nq |

0.12 |

0.16 |

1.29 |

0.06 |

3.11 |

0.01 |

3.41 |

0.35 |

29.66 |

1.8 |

| Colourless |

nd/nq |

7.13 |

19.52 |

40.47 |

0.24 |

nd/nq |

0.11 |

0.16 |

0.96 |

0.06 |

0.54 |

0.01 |

3.66 |

0.27 |

26.82 |

1.4 |

| Cheam |

C1 |

Green |

nd/nq |

5.58 |

18.57 |

35.00 |

0.34 |

0.68 |

0.10 |

0.18 |

1.08 |

0.05 |

2.31 |

0.17 |

3.76 |

0.38 |

31.77 |

1.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).