3.1. Reactor I – Placement of Electrolysis before the Activation Tank

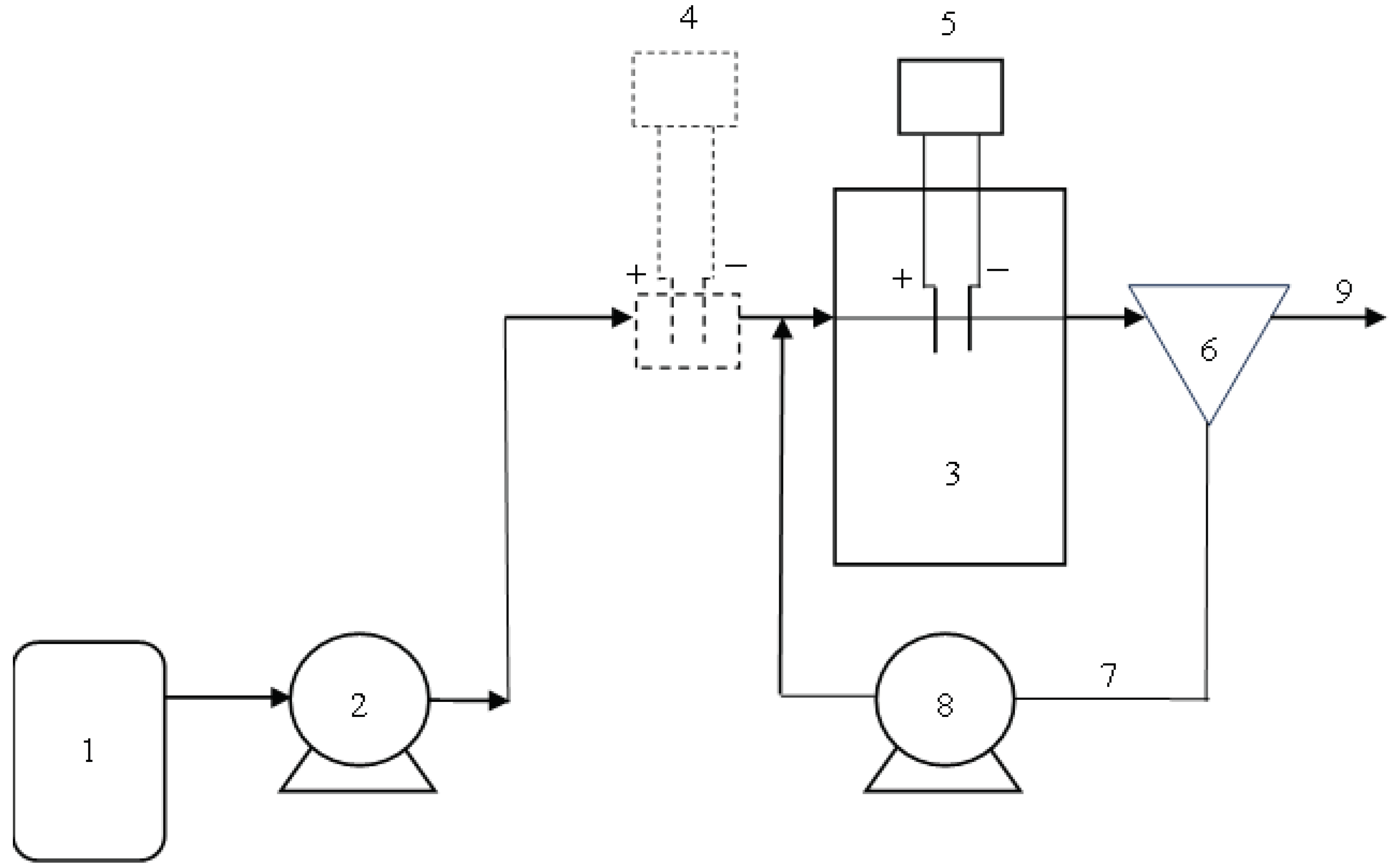

In this reactor, the influence of electrolysis placement before the activation tank was investigated. Iron electrodes were submerged into a 0.3-liter tank and spaced 5 cm apart. Electrolysis was activated twice a day for 15 minutes each time.

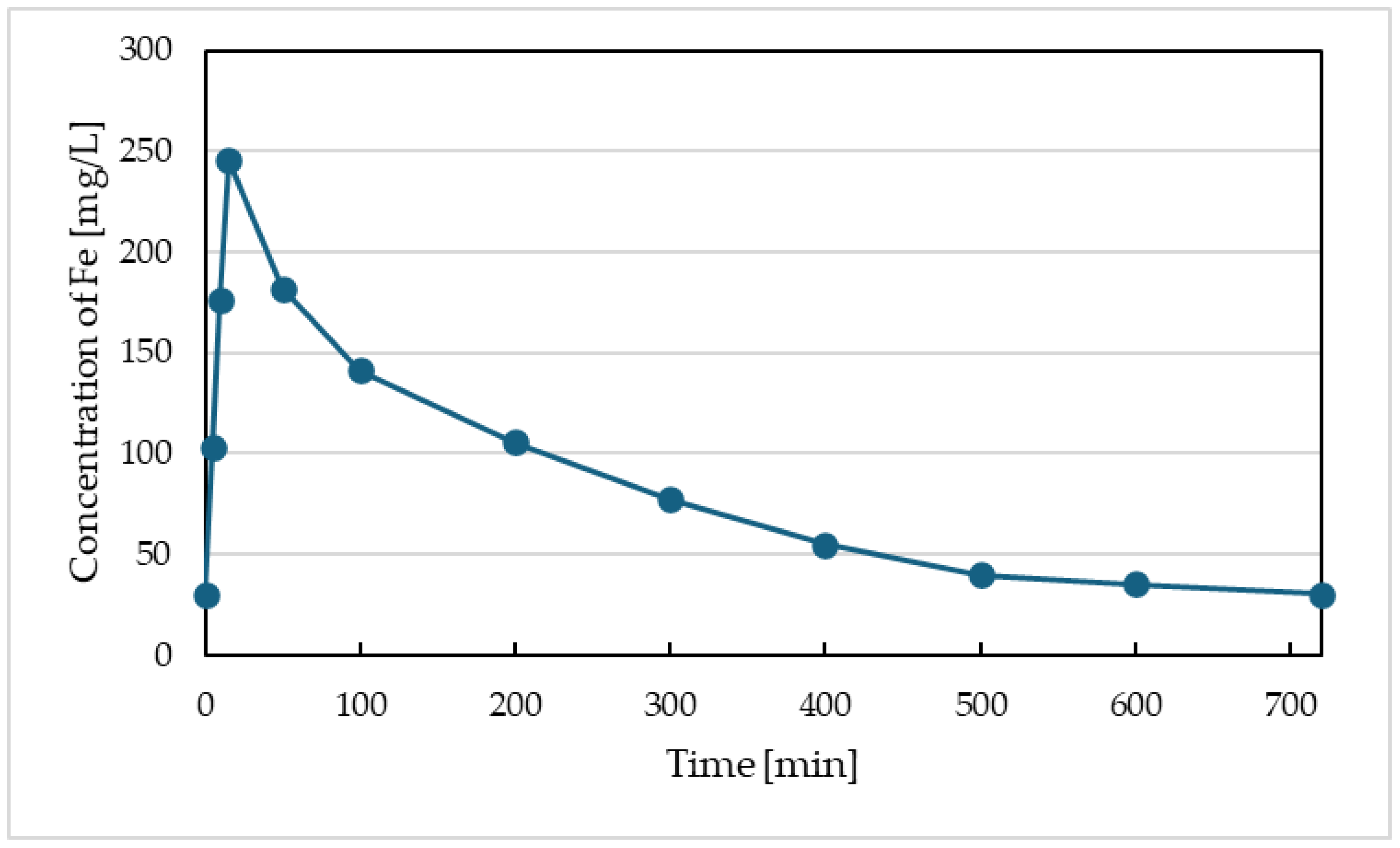

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of iron concentration in the container with electrolysis. This figure represents the dosing of iron into the activation tank. We can observe that this dosing is not steady, and after 15 minutes of iron concentration increase due to electrolysis, iron is gradually washed out by the flow of wastewater into the activation tank. The unevenness of iron concentration over the hydraulic retention time in activation was not reflected in the evolution of iron concentration at the effluent from the activation or from the sedimentation tank (see

Figure 3). We primarily monitored the impact of electrolysis on parameters such as COD and P-PO

4 at the effluent of the laboratory model, assuming that these parameters might be affected. Additionally, we focused on the influence on sludge sedimentation properties.

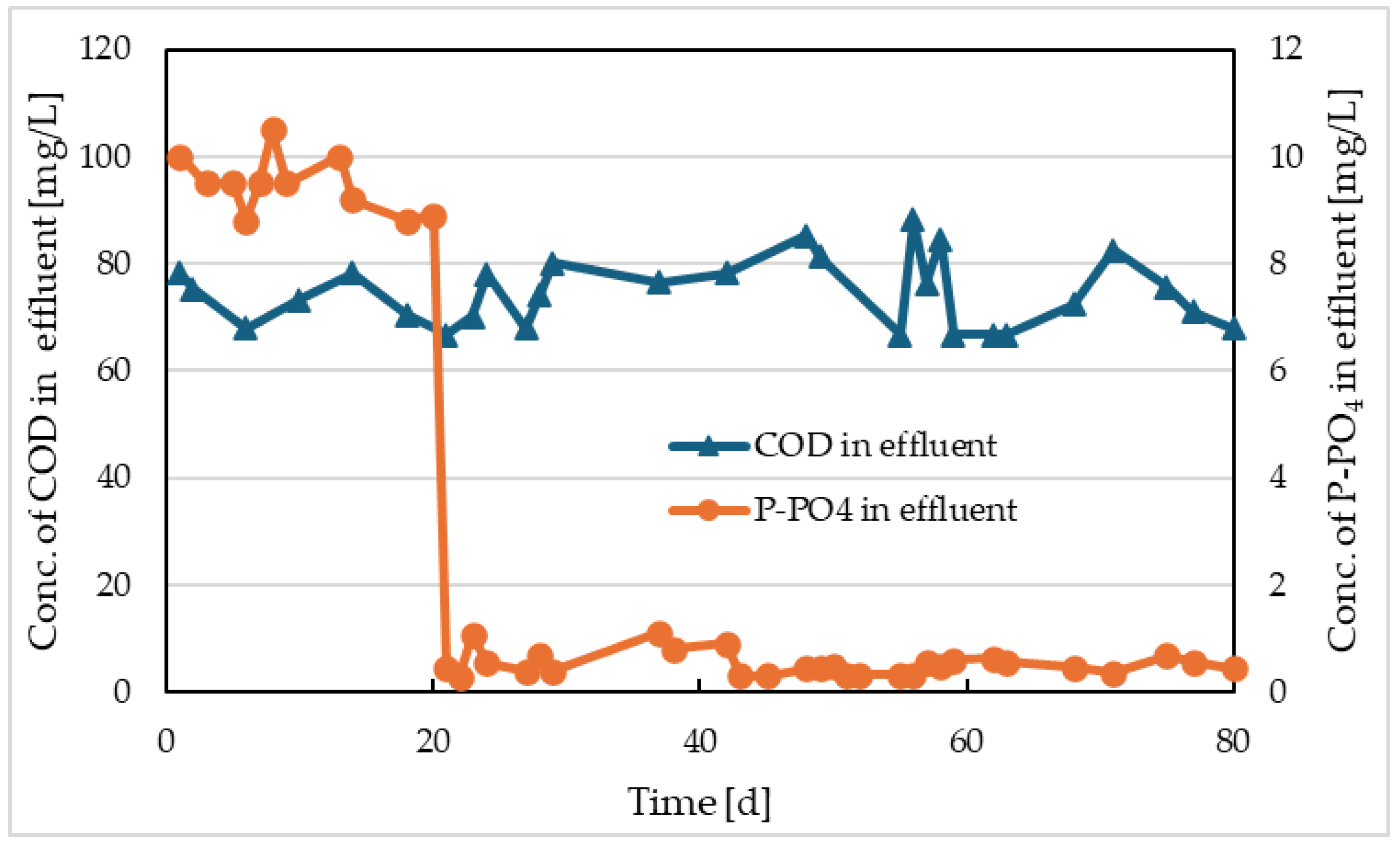

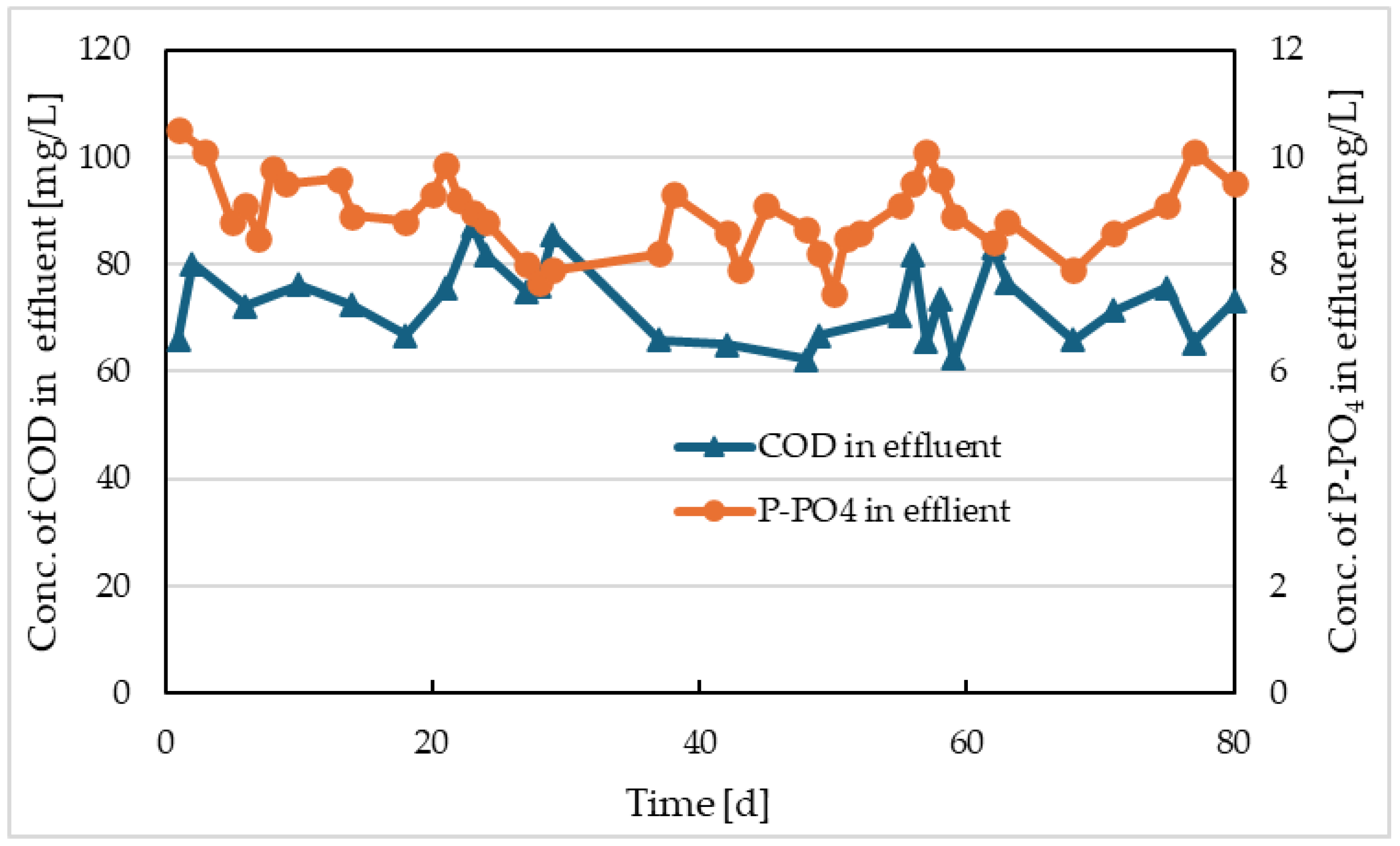

The values of COD at the outlet from Reactor I and the comparative model are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, respectively. The output concentrations of P-PO

4 are also depicted on the same figures. From the COD trends of both models, it is evident that separate electrolysis did not have a significant impact on the output values. This is mainly due to the fact that electrocoagulation has higher efficiencies of COD removal above 50% for wastewater with high concentrations of insoluble, especially colloidal particles, and high molecular weight organic substances [

15]. The synthetic wastewater we used contained only simple and easily degradable substances (glucose and sodium acetate), and therefore no contribution to COD removal efficiency was observed for the electrocoagulation process. Nevertheless, the average COD removal efficiency in Reactor I was 90.7%, and in the comparative model, it was 90.9%.

However, the concentrations of P-PO

4 were different. While the average concentration of P-PO

4 in the comparative model was 8.9 mg/L (

Figure 5), in the model with separate electrolysis, this concentration was 9.4 mg/L before the electrolysis was started, and immediately after the electrolysis was initiated, it dropped to values ranging from 0.3 to 1.07 mg/L with an average of 0.52 mg/L (

Figure 4). In the comparative model, the decrease in phosphate concentration from 15 mg/L to an average value of 8.9 mg/L was mainly due to assimilation into the newly formed activated sludge. In the model with electrolysis, more than 96.5% efficiency in removing P-PO

4 was due to both assimilation and precipitation of phosphates by iron released during electrolysis from the iron electrode. The average concentration of P-PO

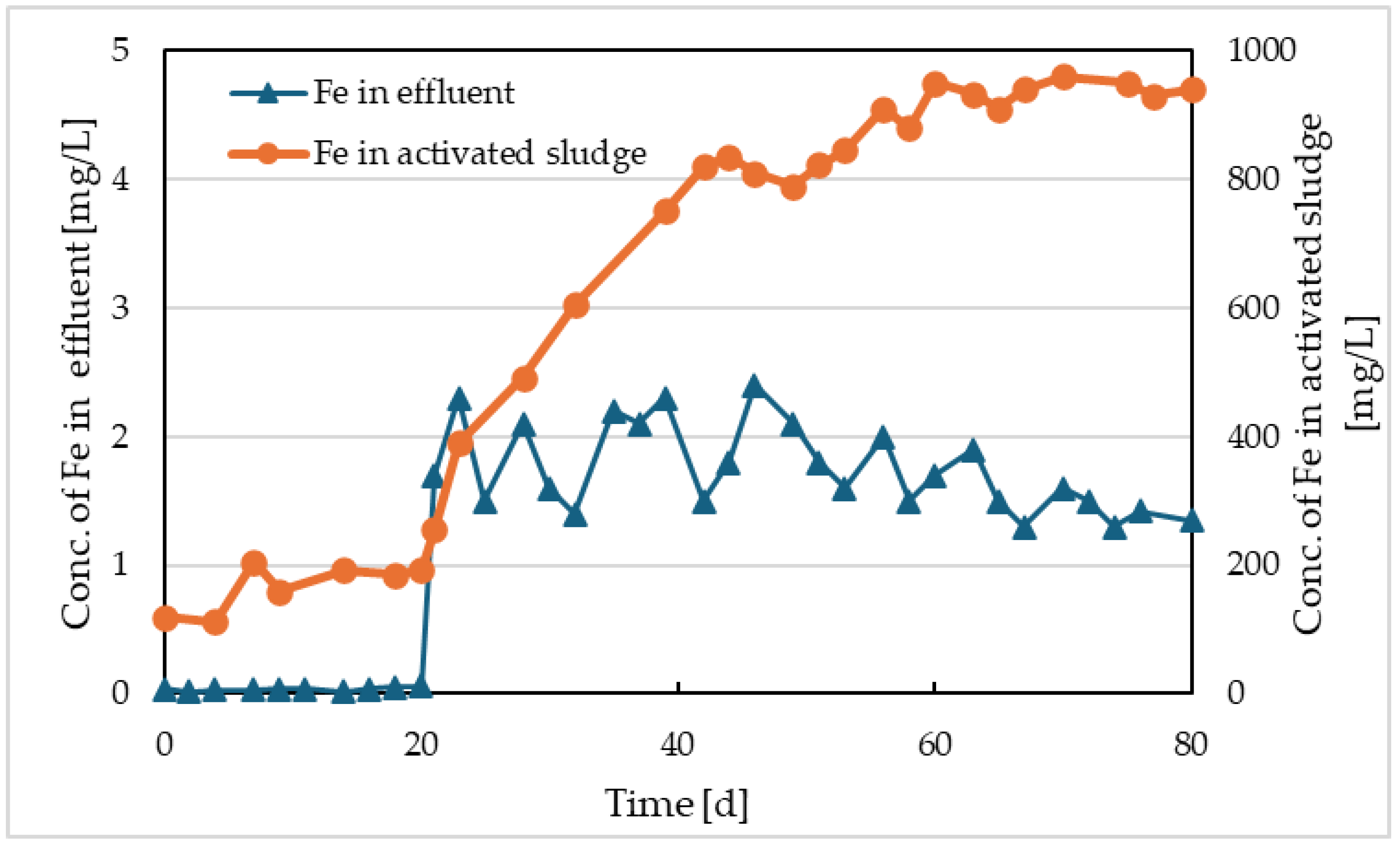

4 after the electrolysis was initiated was 0.52 mg/L. The concentrations of iron at the outlet from Reactor I and in its activated sludge are shown in

Figure 3. From this figure, it can be seen that most concentrations of phosphate were below 1 mg/L. However, this does not necessarily imply the optimal amount of released iron for phosphate precipitation. Iron, besides precipitating with phosphorus, also forms Fe(OH)

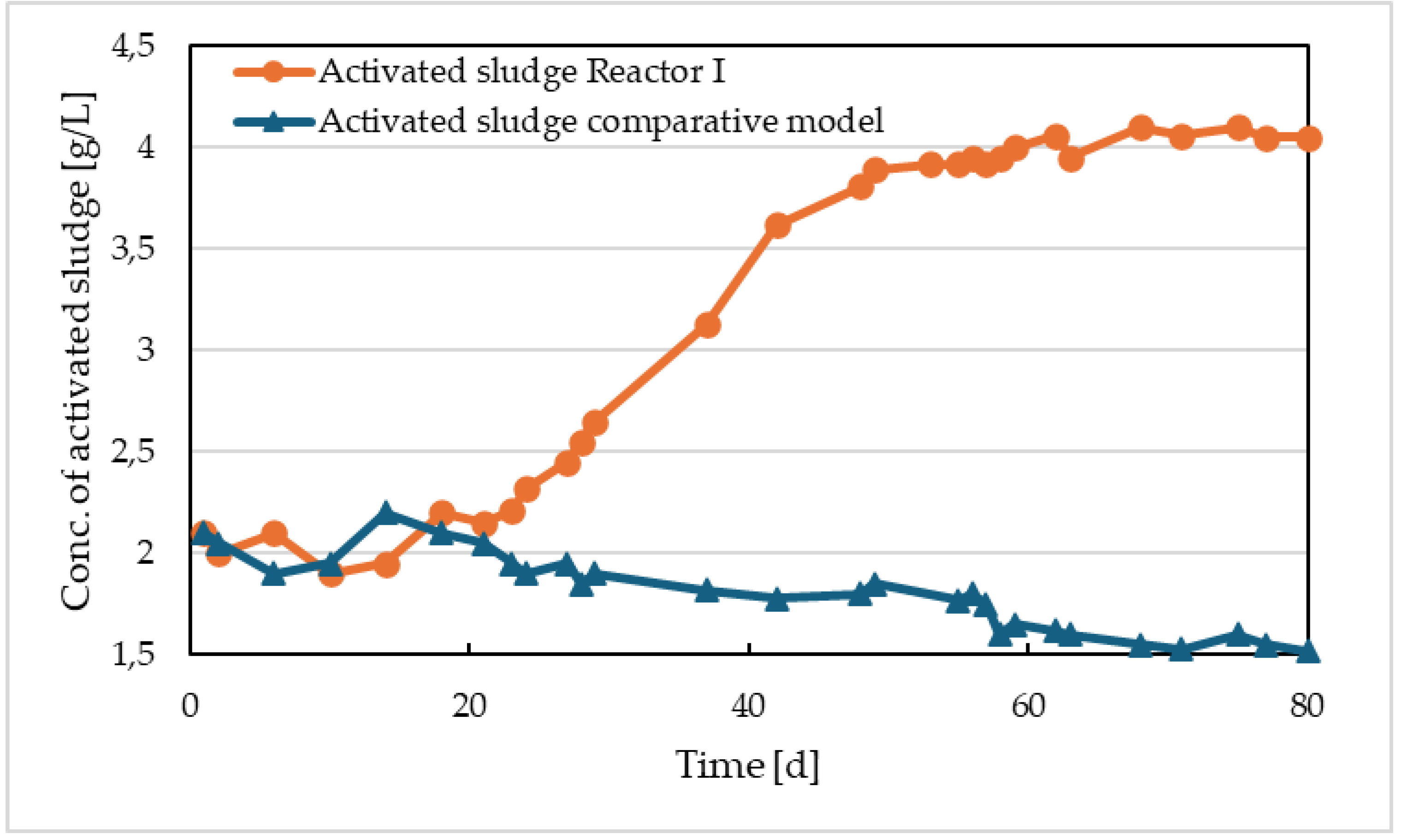

3 precipitates. These precipitates become part of the activated sludge. While in the comparative model, the initial concentration of activated sludge of 2.1 g/L slightly decreased, reaching 1.52 g/L by the end of operation, in Reactor I, it increased to a concentration of 4.05 g/L (

Figure 6). As seen in

Figure 3, the iron concentration in the sludge gradually increased, stabilizing at a value of approximately 930 mg/L in the last 20 days of operation. The volatile suspended solids (VSS) content in this sludge was 47%. This indicates the accumulation of chemical sludge in the activation tank. By removing the excess sludge with a sludge age of 15 days after approximately 60 days, an equilibrium was reached in the dissolution of iron by electrolysis, the formation of chemical sludge with iron content, the removal, and the discharge of iron at the outlet of the model. The proportion of activated sludge from the mixture with chemical sludge was 2.4 g, which means that besides the amount of chemical sludge, the amount of activated sludge also slightly increased. The development of the concentration of activated sludge in Reactor I and in the comparative model is shown in

Figure 6. Over the entire operating period of the model, approximately 7200 mg of Fe was dissolved, and 6.92 Ah was consumed. This value is derived from the theoretical mass-based electrochemical equivalent of 1041 mg/Ah Fe [

1]. This represents a total electricity consumption of 145.3 Wh at the applied voltage of 21 V.

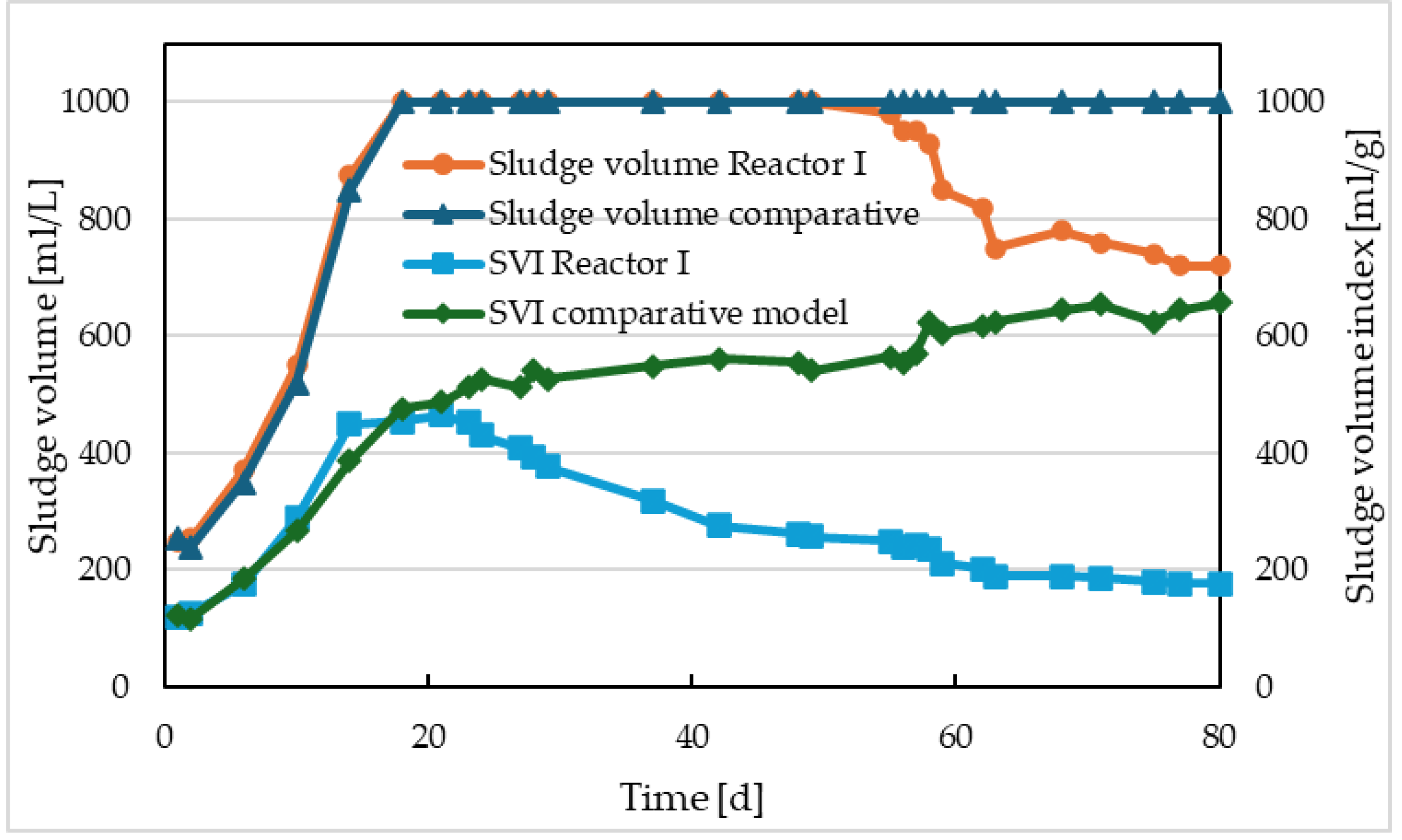

The inclusion of electrolysis before activation also had another effect on improving the sedimentation properties of the sludge (

Figure 7). The electrolysis, or the influx of dissolved iron into the activation, appeared almost immediately after the initiation of electrolysis, due to the rapid increase in the concentration of activated sludge, especially its inorganic fraction. However, this was reflected in the sludge volume index (SVI) values only after about 50 days of reactor operation, or 30 days after the start of electrolysis. It was only then that a phase interface between sludge and liquid began to form in the sedimentation cylinder. However, this was not due to the disappearance of filamentous microorganisms but rather due to the weighting effect of iron sludge.

The effect of iron on sludge activity was also assessed by measuring respiration rates - both endogenous and total (endogenous + exogenous). We conducted these measurements using the methodology outlined in reference [

14], employing a closed respirometric chamber. The results of these measurements are presented in

Table 2. From these values, it is evident that the presence of iron in the activation with pre-electrolysis had a positive effect on the activity of the activated sludge. However, due to the composition of the synthetic wastewater, which contained easily degradable components, this effect was not reflected in the effluent values of COD (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The positive impact of iron dosage on the activity of activated sludge is reported in various studies, such as references [

16,

17], where authors reported an increase in total respiration rates in the presence of iron by 40 - 50%. However, information in the scientific literature regarding the effect of iron on respiratory rates of activated sludge is contradictory. Some studies mention a negative effect of iron on the activation process due to a decrease in pH values during the formation of Fe(OH)

3 [

18,

19]. In reference [

19], authors not only mention a negative effect on respiratory rates but also on nitrification rates. Furthermore, the authors of reference [

20] did not observe any changes in exogenous rates before and after simultaneous dosing of FeCl

3. However, these findings are questionable because when using domestic wastewater, the measured exogenous respiration rate was only 6.3 mg/(g

VSS ·h) O

2.

3.2. Reactor II – Electrolysis with Iron Electrodes Directly in the Activation Tank

In reactor II, where electrolysis with iron electrodes directly in the activation tank was used, we assumed that not only the influence of dissolved iron but also the effect of electrical current on the activation process would be evident. We compared the results with a reactor without electrolysis, and in the reference reactor, we initiated dosing of Fe2(SO4)3 (Prefloc) at the same time as the electrolysis in reactor II - on the 20th day of operation.

Electrolysis in the activation was performed twice daily for 15 minutes each time, corresponding to the amount of iron required for chemical precipitation. The dose of Prefloc was administered twice daily at 0.35 mL each time, approximately equivalent to the amount of iron released during electrolysis.

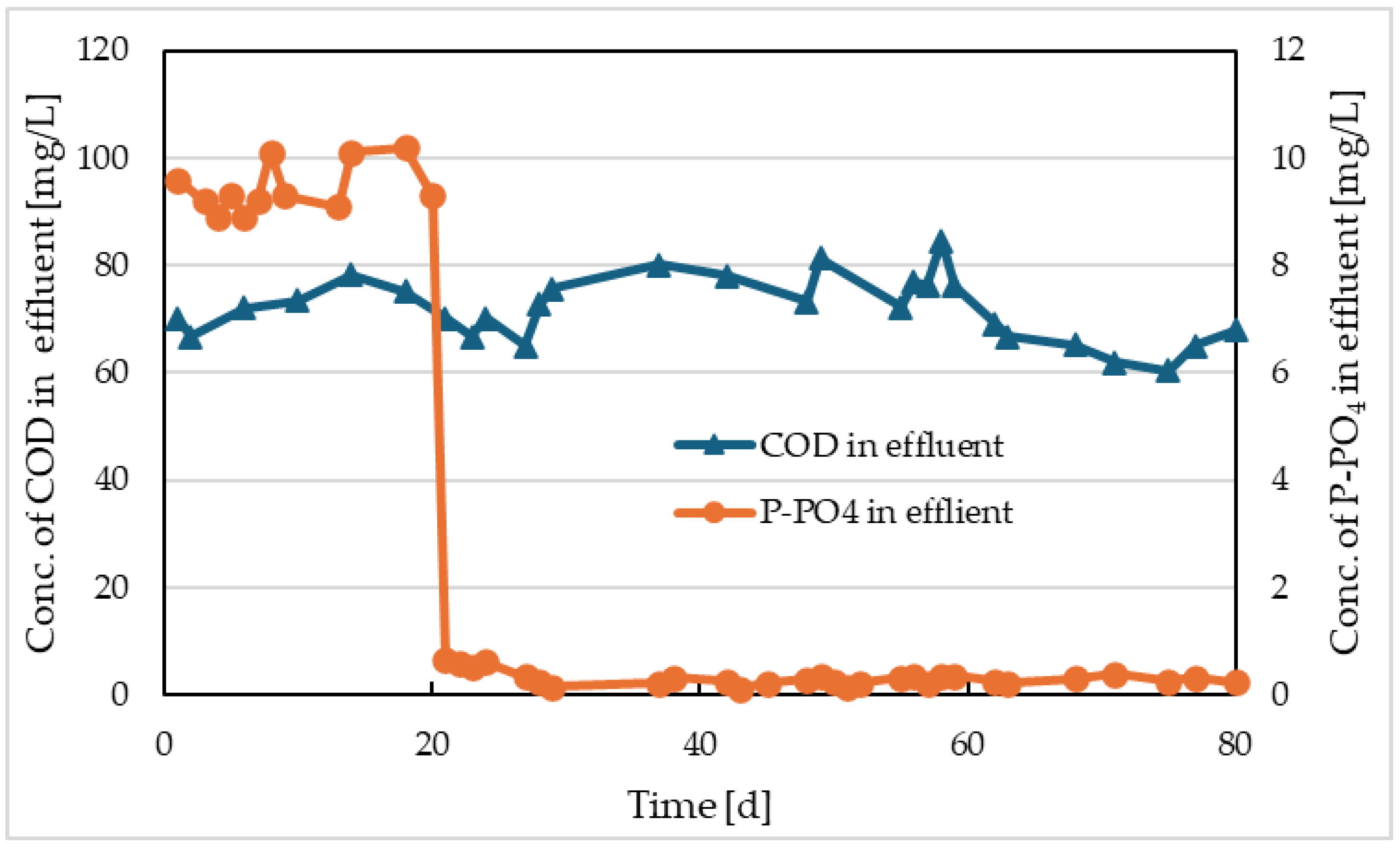

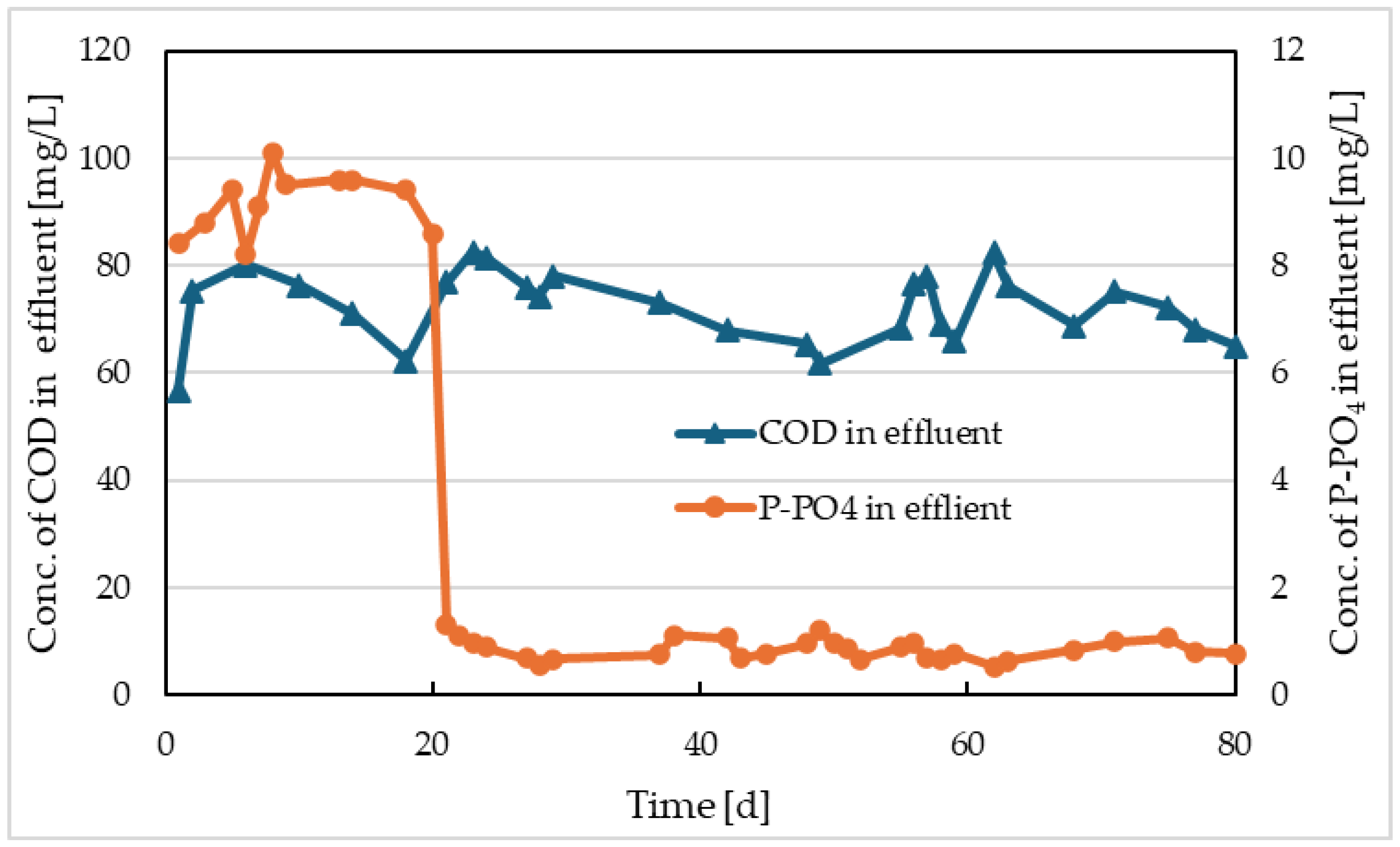

Courses of COD and P-PO

4 values in Reactor II and the comparative model are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. There were no significant differences in COD values in these activations, with the average outlet COD from both reactors being approximately 72 mg/L. Regarding phosphorus removal, improvement was observed in both reactors after the start of electrolysis or Prefloc dosing. In Reactor II, lower P-PO

4 concentrations were achieved in the range of 0.11-0.38 mg/L with an average of 0.27 mg/L, while in the reactor with Prefloc dosing, the range of values was 0.52-1.2 mg/L with an average of 0.87 mg/L.

The studies on the use of electrocoagulation report more effective phosphorus precipitation [

21,

22]. While in chemical phosphorus precipitation, high removal efficiencies and concentrations in the effluent below 0.5 mg/L P-PO

4 are achieved at high molar ratios of Fe/P - β ≥ 2, with electrocoagulation, this is also achieved at molar ratios well below β ≤ 1.5 [

21].

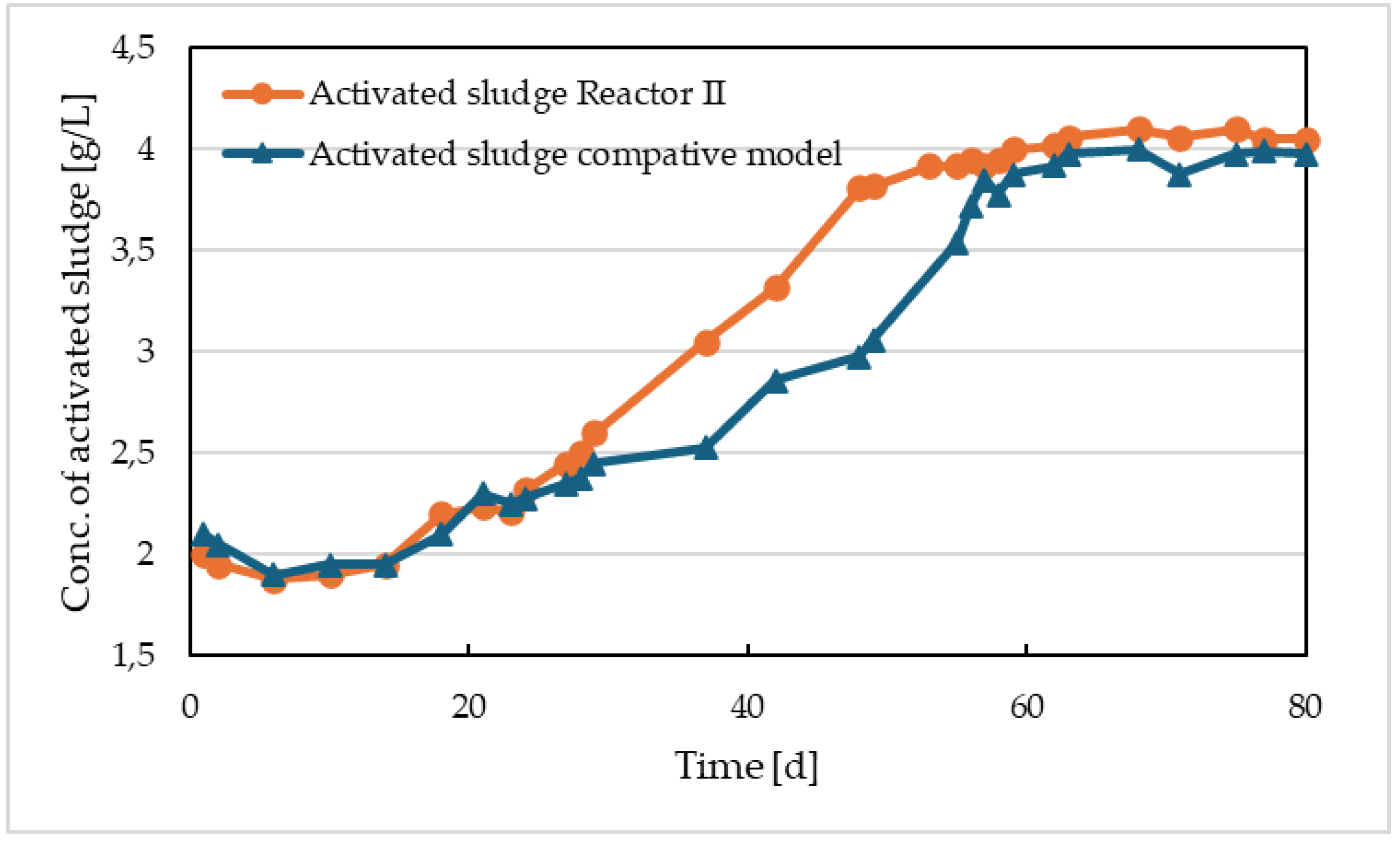

The concentration of activated sludge in Reactor II and in the comparative reactor with Prefloc dosing is shown in

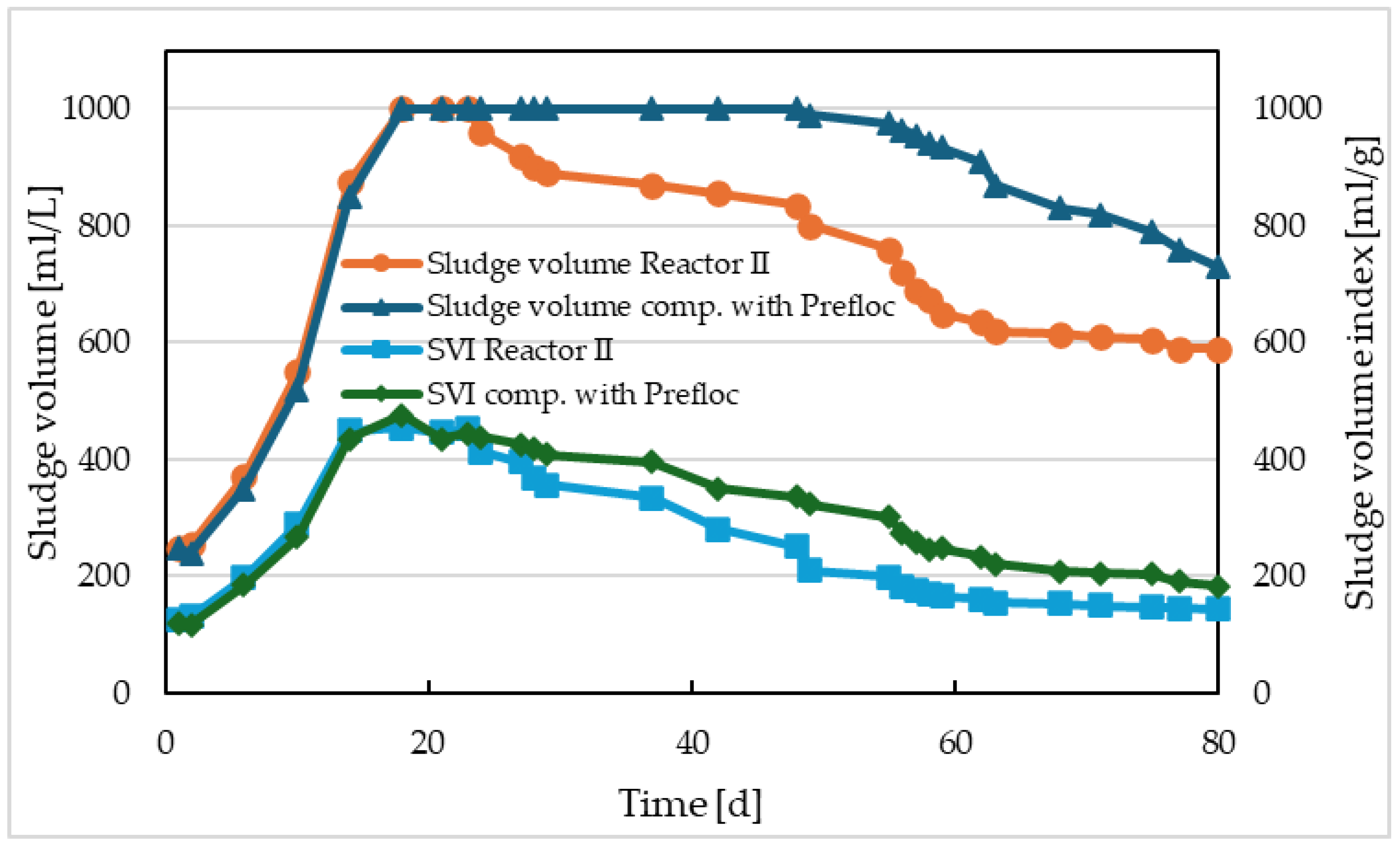

Figure 10. The dry solids content in both activations increased and reached nearly identical concentrations of approximately 4 g/L. In both cases, this was due to a slight increase in biological sludge, but mainly due to an increase in the concentration of chemical sludge. The loss by ignition in both sludges was approximately 48% at the end of the reactor monitoring period. The impact of electrocoagulation compared to precipitation is evident from the monitoring of sludge sedimentation properties – shown in

Figure 11. In the comparative model with Prefloc dosing, the volume of sludge after 30 min sedimentation and sludge volume index followed a similar pattern as in the system with pre-electrolysis – filamentous microorganisms continued to be part of the activated sludge, and the decrease in sediment volume and sludge volume index was caused by chemical sludge loading. In the case of Reactor II, the decrease in sediment volume and sludge volume index was also caused by changes in sludge morphology, gradual disappearance of filamentous microorganisms, and the formation of flocculent biomass.

Microscopic observations confirmed a gradual degradation of Sphaerotilus natans fibers and almost complete disappearance of this type of filamentous microorganism, accompanied by the formation of activated sludge flocs.

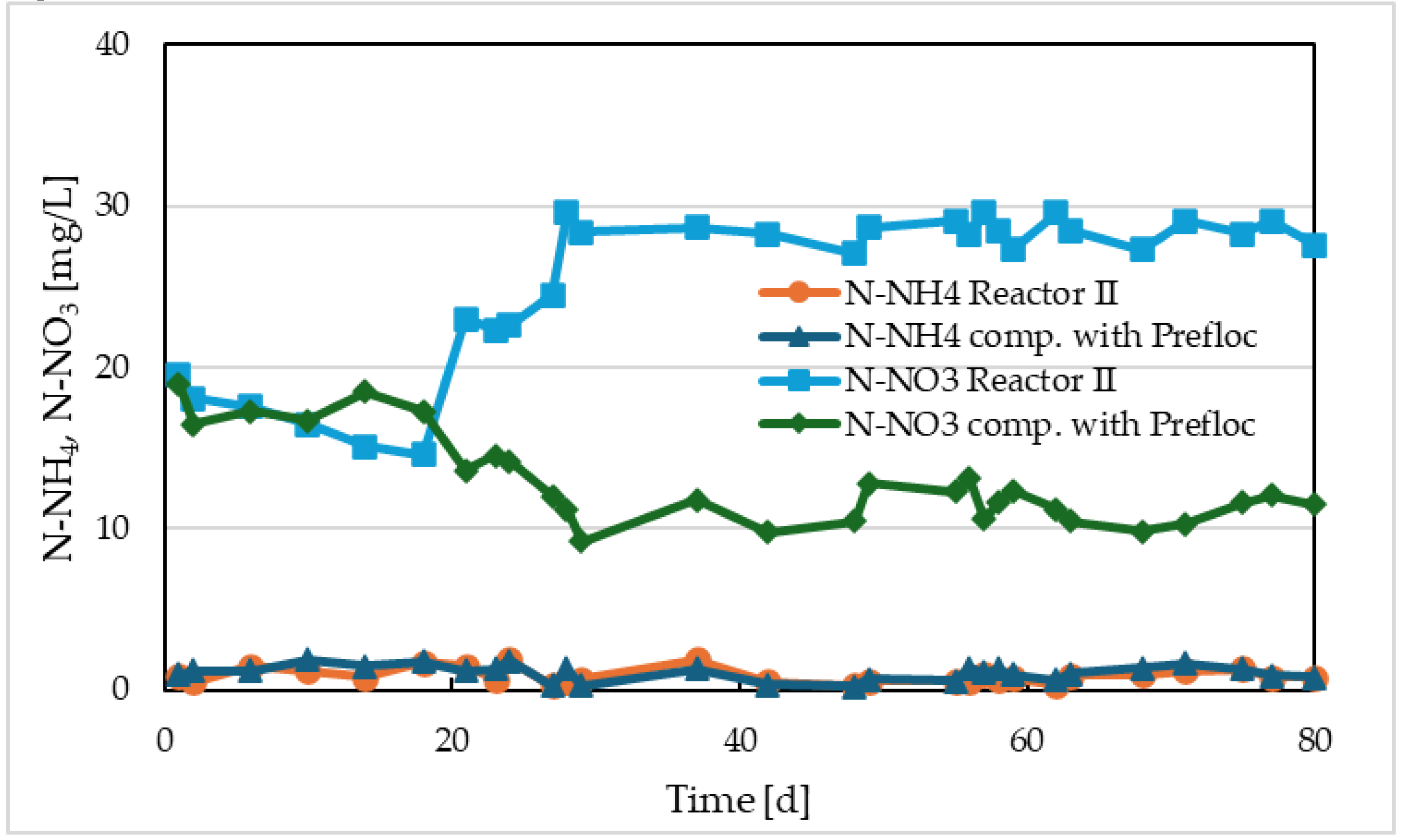

Even with this reactor configuration, we conducted measurements of activated sludge activity. From the respiration rates provided in

Table 2, it is evident that sludge respiration activity was stimulated when Prefloc was dosed, similar to the pre-electrolysis before activation. However, electrocoagulation within the activation, despite the released iron, had a negative impact on sludge activity. Although electrocoagulation in the activation improved sludge sedimentation properties and reduced phosphorus concentration at the outlet, it inhibited sludge activity. This could be due to the removal of filamentous microorganisms, which played a significant role in removing easily degradable substrate. It is possible that sludge activity would recover with a sufficient increase in the proportion of floc-forming microorganisms. We verified nitrification activity of activated sludge by measuring the concentration of N-NH

4 and N-NO

3 at the effluent of the models. These concentrations are shown in

Figure 12.

From the concentrations of N-NH

4 at the effluent, it is evident that the nitrification efficiency in both reactors was high, with average concentrations of ammonium nitrogen around 1 mg/L in both cases. Differences were observed in the concentrations of nitrate nitrogen at the output of the models. In the reactor with Prefloc dosing, the effluent concentration of N-NO

3 decreased from an average of 17.6 mg/L to an average of 11.7 mg/L after dosing began. Considering the input concentration of N-NH

4 of 40 mg/L, it can be said that, in addition to nitrification, partial simultaneous denitrification occurred at the anoxic core level of the sludge flocs. The presence of iron increased the rate of nitrate respiration. Stimulation of nitrate respiration is also reported by other authors [

17]. With an input concentration of phosphate phosphorus of 9 mg/L and a dose of Fe

2+, approximately 26% stimulation of nitrate respiration was observed, and with a dose of Fe

3+, approximately 108% stimulation was observed. The molar ratio of Fe/P was 1.5. In the case of Reactor II, the opposite was observed. Before the start of electrolysis, the average concentration of N-NO

3 was approximately 16.9 mg/L, and after the start of electrolysis, the average concentration of N-NO

3 increased to 27.5 mg/L. We can conclude that just as electrolysis negatively affected oxygen respiration rates, it also affected nitrate respiration.

The negative impact of electrolysis on activated sludge has also been utilized in studies where electrolytic decomposition was used for the production of volatile fatty acids [

10] or to reduce its quantity and improve dewatering properties [

11].

In the next study, we focused on examining the impact of electrolysis itself on the activation process, without the release of iron.

3.3. Reactor III: Electrolysis using Carbon Electrodes Directly in the Activation

During the operation of Reactor III, our focus was on comparing the activation model, which processed synthetic wastewater with carbon electrodes submerged. The wastewater used was the same as in the operation of Reactor I and Reactor II, and the parameters of electrolysis with carbon electrodes are provided in the experimental section. Due to the different shape of the electrodes, we had to select a criterion for comparing the electrolysis parameters. We chose electrical power consumption, or rather, the consumption of electrical energy, which was in the case of using iron electrodes 2.1-2.84 Wh/d. The electrolysis operated twice a day for 15 minutes each time. In the case of carbon electrodes, a voltage of 21 V was applied, and the current supplied was 82.5 mA. With a 15-minute duration of electrolysis, the energy consumption is 0.433 W. If we want energy consumption in the same range as with iron electrodes, we need approximately six times longer duration of electrolysis. This means the duration of electrolysis with carbon electrodes needs to be six times 15 minutes per day. The electrolysis started operation, as in all cases, on the 20th day of activation operation. The comparative activation was the same as in Reactor I. The values of COD and P-PO

4 concentrations at the outlet of the comparative model are shown in

Figure 5. The trends of these parameters for Reactor III were very similar to those in the comparative reactor. We can conclude that submerged carbon electrolysis had no impact on the outlet concentrations of COD and P-PO

4. We also monitored the concentrations of N-NH

4 and N-NO

3 at the effluent of the model with submerged electrolysis and in the comparative reactor. Ammonium nitrogen concentrations were low, with an average value at the outlet of both reactors around 1 mg/L, similar to

Figure 12. There were no differences between the models in the outlet concentrations of nitrate nitrogen, which ranged from 13-20 mg/L, as seen in

Figure 12 in the first 20 days of model operation. The only difference was in the volume of sedimented sludge after 30 minutes and in the sludge volume index shown in

Figure 13. The comparative sludge reached a sediment volume of 1000 ml even before the 20th day, and it maintained this volume throughout the operation due to the presence of filamentous microorganisms. The sludge from the activation with carbon electrodes reached approximately 1000 ml sediment volume until the 35th day of operation, about 15 days after the electrolysis was initiated. Then, it began to gradually decrease until reaching a volume of approximately 550 ml at the end of its operation. The activity of the sludge was also measured using respiratory rates - see

Table 2. Only the respiratory rates for Reactor III are provided in the table. The respiratory rates in the comparative model were the same as in the case of Reactor I. From these measurements, it is evident that electrolysis using carbon electrodes inserted into the activation had no effect on the respiratory activity of the sludge. The consistent trend in the concentration of N-NO

3 during the operation at the output of both reactors indicated that partial simultaneous denitrification occurs at the anoxic core level of the sludge flocs, and neither was the nitrate respiration of the sludge affected by electrolysis. This finding contradicts the result obtained with submerged electrolysis using iron electrodes in Reactor II. In that case, the respiratory rate was negatively affected, and after the electrolysis was switched on, the nitrate concentration at the outlet increased - see

Figure 12. This could be due to the fact that although the electrical power input to the electrodes was the same for Reactors II and III, the difference lay in the supplied current - it was 270 mA for the iron electrodes and 82.5 mA for the carbon electrodes.