Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Gut Microbiota

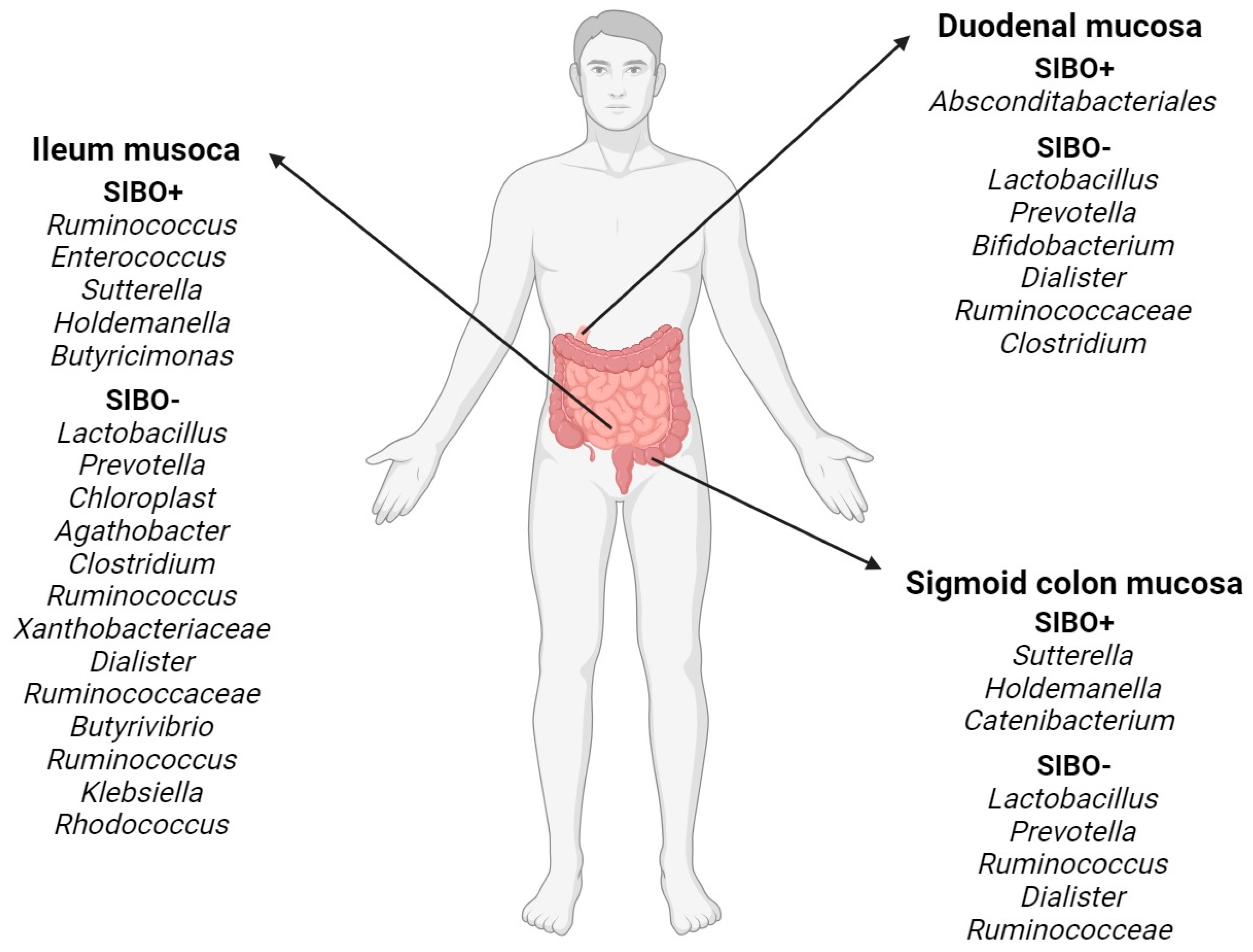

3. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Diagnostics

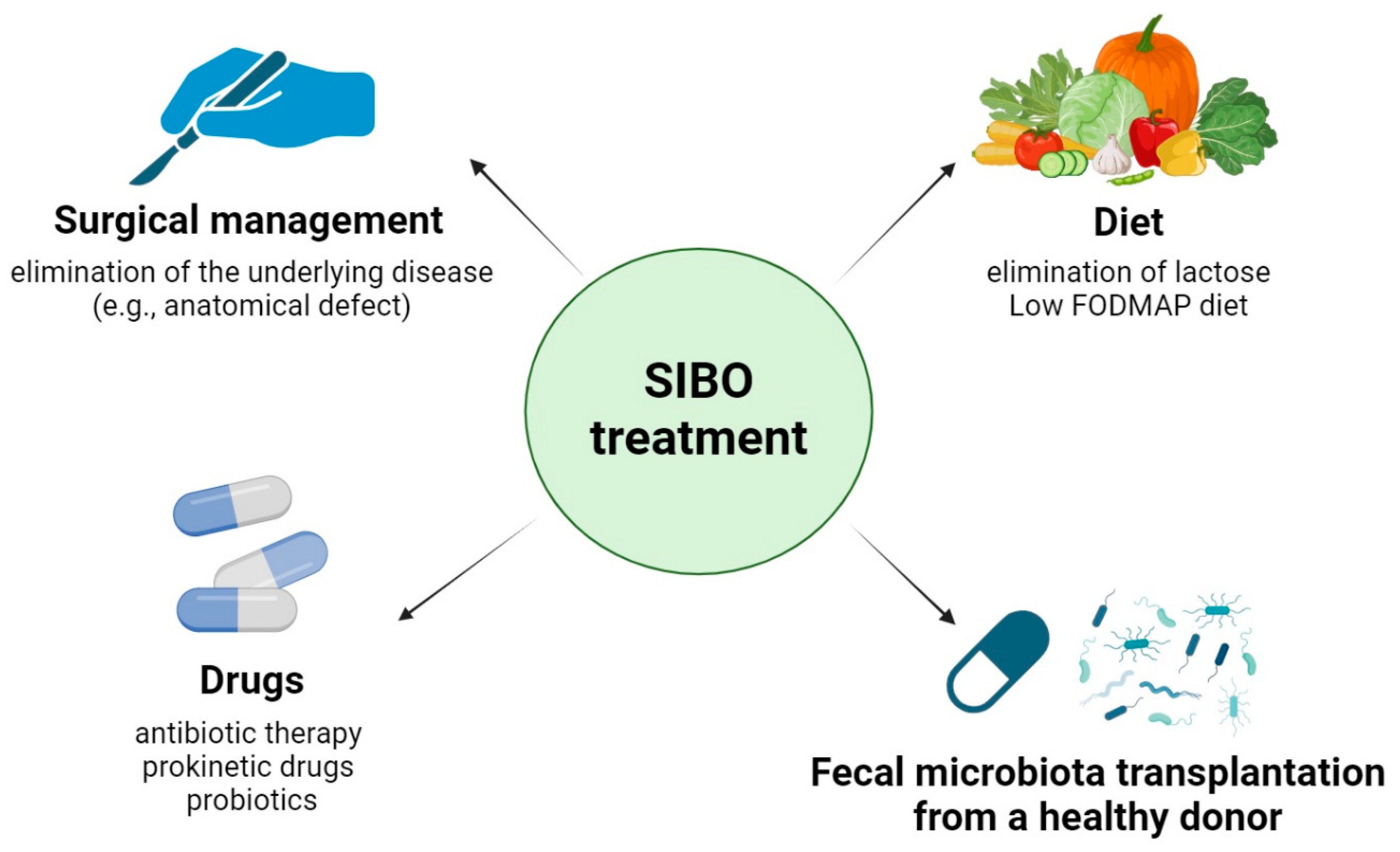

3.3. Treatment and Diet

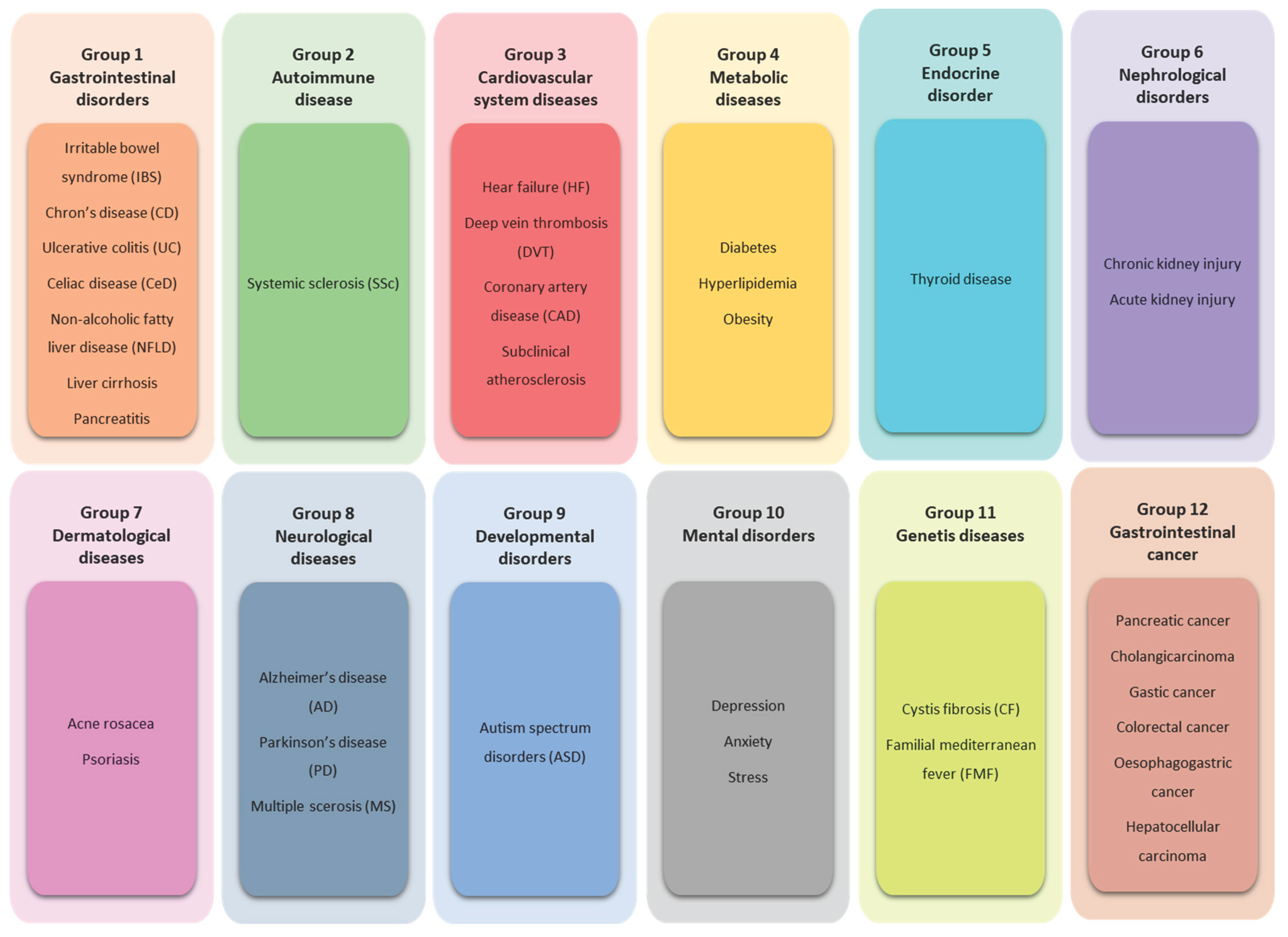

4. SIBO – Related Diseases

4.1. Group 1. Gastrointestinal Disorders

4.1.1. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

4.1.2. Crohn's Disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

4.1.3. Celiac Disease (CeD)

4.1.4. Non‒Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

4.1.5. Liver Cirrhosis

4.1.6. Pancreatitis

4.2. Group 2. Autoimmune Disease

Systemic Sclerosis (SSc)

4.3. Group 3. Cardiovascular System Diseases

4.3.1. Heart Failure (HF)

4.3.2. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

4.3.3. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

4.3.4. Subclinical Atherosclerosis

4.4. Group 4. Metabolic Diseases

4.4.1. Diabetes

4.4.2. Hyperlipidemia

4.4.3. Obesity

4.5. Group 5. Endocrine Disorder

Thyroid Disease

4.6. Group 6. Nephrological Disorders

4.6.1. Chronic Kidney Injury

4.6.2. Acute Kidney Injury

4.7. Group 7. Dermatological Diseases

4.7.1. Acne Rosacea

4.7.2. Psoriasis

4.8. Group 8. Neurological Diseases

4.8.1. Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

4.8.2. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

4.8.3. Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

4.9. Group 9. Developmental Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

4.10. Group 10. Mental Disorders

4.11. Group 11. Genetic Diseases

4.11.1. Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

4.11.2. Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF)

4.12. Group 12. Gastrointestinal Cancer

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnstone, C.; Hendry, C.; Farley, A.; McLafferty, E. The digestive system: part 1. Nurs Stand 2014, 28, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, E.M. Gut bacteria in health and disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013, 9, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hrncir, T. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Triggers, Consequences, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Options. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achufusi, T.G.O.; Sharma, A.; Zamora, E.A.; Manocha, D. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Methods. Cureus 2020, 12, e8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judkins, T.C.; Archer, D.L.; Kramer, D.C.; Solch, R.J. Probiotics, Nutrition, and the Small Intestine. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2020, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, N.; Lacy, B. Anatomy and Physiology of the Small Bowel. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2017, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Gordon, J.I. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science 2001, 292, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursell, L.K.; Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev 2012, 70 Suppl 1, S38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederberg, J.M., A. T. Ome Sweet 'Omics - A Genealogical Treasury of Words. The Scientist 2001, 15, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Backhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethlefsen, L.; Eckburg, P.B.; Bik, E.M.; Relman, D.A. Assembly of the human intestinal microbiota. Trends Ecol Evol 2006, 21, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Peterson, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell 2006, 124, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losurdo, G.; Salvatore D'Abramo, F.; Indellicati, G.; Lillo, C.; Ierardi, E.; Di Leo, A. The Influence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Digestive and Extra-Intestinal Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, M.; Shin, A.; Teagarden, S.; Xu, H.; Gupta, A.; Siwiec, R.; Nelson, D.; Wo, J.M. Risk Factors Associated With Upper Aerodigestive Tract or Coliform Bacterial Overgrowth of the Small Intestine in Symptomatic Patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 2020, 54, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Ma, J.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wan, J. Mucosa-Associated Microbial Profile Is Altered in Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 710940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, M.; Saad, R.J.; Long, M.D.; Rao, S.S.C. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Am J Gastroenterol 2020, 115, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbarrini, A.; Lauritano, E.C.; Gabrielli, M.; Scarpellini, E.; Lupascu, A.; Ojetti, V.; Gasbarrini, G. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: diagnosis and treatment. Dig Dis 2007, 25, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushyhead, D.; Quigley, E.M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2021, 50, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.D. Macrocytic anemia associated with intestinal strictures and anastomoses: report of two cases. Ann Intern Med 1954, 40, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, B.S.; Lin, H.C. Double-blind, placebo-controlled antibiotic treatment study of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in children with chronic abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011, 52, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boissieu, D.; Chaussain, M.; Badoual, J.; Raymond, J.; Dupont, C. Small-bowel bacterial overgrowth in children with chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, or both. J Pediatr 1996, 128, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korterink, J.J.; Benninga, M.A.; van Wering, H.M.; Deckers-Kocken, J.M. Glucose hydrogen breath test for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in children with abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015, 60, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniewicz-Luzenczyk, K.; Bik-Gawin, A.; Zeman, K.; Bak-Romaniszyn, L. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome in children. Prz Gastroenterol 2015, 10, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaie, A.; Buresi, M.; Lembo, A.; Lin, H.; McCallum, R.; Rao, S.; Schmulson, M.; Valdovinos, M.; Zakko, S.; Pimentel, M. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2017, 112, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, R.J.; Chey, W.D. Breath testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: maximizing test accuracy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 12, 1964–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.C.; Bhagatwala, J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2019, 10, e00078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, A.; Peng, B.; Soffer, E. Pattern of methane levels with lactulose breath testing; can we shorten the test duration? JGH Open 2021, 5, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukowicz, A.C.; Lacy, B.E.; Levine, G.M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comprehensive review. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2007, 3, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Adike, A.; DiBaise, J.K. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Nutritional Implications, Diagnosis, and Management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2018, 47, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderhoof, J.A.; Young, R.J.; Murray, N.; Kaufman, S.S. Treatment strategies for small bowel bacterial overgrowth in short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1998, 27, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, A.; Sessarego, M.; Greco, A.; Bazzica, M.; Filaci, G.; Setti, M.; Savarino, E.; Indiveri, F.; Savarino, V.; Ghio, M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients suffering from scleroderma: clinical effectiveness of its eradication. Am J Gastroenterol 2008, 103, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frissora, C.L.; Cash, B.D. Review article: the role of antibiotics vs. conventional pharmacotherapy in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007, 25, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, H.L.; DuPont, H.L. Rifaximin: a unique gastrointestinal-selective antibiotic for enteric diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010, 26, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatta, L.; Scarpignato, C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017, 45, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Lee, H.R.; Low, K.; Chatterjee, S.; Pimentel, M. Rifaximin versus other antibiotics in the primary treatment and retreatment of bacterial overgrowth in IBS. Dig Dis Sci 2008, 53, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabenstein, T.; Fromm, M.F.; Zolk, O. [Rifaximin--a non-resorbable antibiotic with many indications in gastroenterology]. Z Gastroenterol 2011, 49, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Strocchi, A.; Malservisi, S.; Veneto, G.; Ferrieri, A.; Corazza, G.R. Non-absorbable antibiotics for managing intestinal gas production and gas-related symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000, 14, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Li, N.; Wang, C.; Xing, H.; Chen, D.; Wei, Y. Clinical efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinic study. BMC Gastroenterol 2021, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickles, M.A.; Hasan, A.; Shakhbazova, A.; Wright, S.; Chambers, C.J.; Sivamani, R.K. Alternative Treatment Approaches to Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review. J Altern Complement Med 2021, 27, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalighi, A.R.; Khalighi, M.R.; Behdani, R.; Jamali, J.; Khosravi, A.; Kouhestani, S.; Radmanesh, H.; Esmaeelzadeh, S.; Khalighi, N. Evaluating the efficacy of probiotic on treatment in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)--a pilot study. Indian J Med Res 2014, 140, 604–608. [Google Scholar]

- Leventogiannis, K.; Gkolfakis, P.; Spithakis, G.; Tsatali, A.; Pistiki, A.; Sioulas, A.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Triantafyllou, K. Effect of a Preparation of Four Probiotics on Symptoms of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Association with Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2019, 11, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.; Rocha, R.; Cotrim, H.P. Diet and intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Is there evidence? World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 4713–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Irving, P.M.; Lomer, M.C.; Whelan, K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 11, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginnebaugh, B.; Chey, W.D.; Saad, R. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: How to Diagnose and Treat (and Then Treat Again). Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2020, 49, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakura, W.; Pimentel, M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome - An Update. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.D.; Shiner, M. Influence of gastric pH on gastric and jejunal flora. Gut 1967, 8, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltzman, J.R.; Kowdley, K.V.; Pedrosa, M.C.; Sepe, T.; Golner, B.; Perrone, G.; Russell, R.M. Bacterial overgrowth without clinical malabsorption in elderly hypochlorhydric subjects. Gastroenterology 1994, 106, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husebye, E.; Skar, V.; Hoverstad, T.; Melby, K. Fasting hypochlorhydria with gram positive gastric flora is highly prevalent in healthy old people. Gut 1992, 33, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iivonen, M.K.; Ahola, T.O.; Matikainen, M.J. Bacterial overgrowth, intestinal transit, and nutrition after total gastrectomy. Comparison of a jejunal pouch with Roux-en-Y reconstruction in a prospective random study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998, 33, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandi, G.; Biavati, B.; Calabrese, C.; Granata, M.; Nannetti, A.; Mattarelli, P.; Di Febo, G.; Saccoccio, G.; Biasco, G. Urease-positive bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori in human gastric juice and mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol 2006, 101, 1756–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, K.; Fukumura, M. Effect of H2-receptor antagonists on bile acid metabolism. J Investig Med 1995, 43, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.B.; Paik, C.N.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.M.; Jun, K.H.; Chung, W.C.; Lee, K.M.; Yang, J.M.; Choi, M.G. Positive Glucose Breath Tests in Patients with Hysterectomy, Gastrectomy, and Cholecystectomy. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouillot, T.; Rhyman, N.; Gauthier, C.; Paris, J.; Lang, A.S.; Lepers-Tassy, S.; Manfredi, S.; Lepage, C.; Leloup, C.; Jacquin-Piques, A.; et al. Study of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in a Cohort of Patients with Abdominal Symptoms Who Underwent Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 2020, 30, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onana Ndong, P.; Boutallaka, H.; Marine-Barjoan, E.; Ouizeman, D.; Mroue, R.; Anty, R.; Vanbiervliet, G.; Piche, T. Prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): Correlating H(2) or CH(4) production with severity of IBS. JGH Open 2023, 7, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Xiang, F.; Feng, J. Correlation between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome and the prognosis of treatment. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 3364–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.Q.; Sun, W.J.; Li, N.; Chen, Y.Q.; Wei, Y.L.; Chen, D.F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by increasing mainly Prevotella abundance. Scand J Gastroenterol 2019, 54, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.C. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA 2004, 292, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Chow, E.J.; Lin, H.C. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Wallace, D.; Hallegua, D.; Chow, E.; Kong, Y.; Park, S.; Lin, H.C. A link between irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia may be related to findings on lactulose breath testing. Ann Rheum Dis 2004, 63, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posserud, I.; Stotzer, P.O.; Bjornsson, E.S.; Abrahamsson, H.; Simren, M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2007, 56, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratten, J.R.; Spanier, J.; Jones, M.P. Lactulose breath testing does not discriminate patients with irritable bowel syndrome from healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol 2008, 103, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Kumar, S.; Mehrotra, M.; Lakshmi, C.; Misra, A. Frequency of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and chronic non-specific diarrhea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010, 16, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, S.; Rawat, A.K.; Reddy, R.S.; Puri, A.S. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in irritable bowel syndrome: frequency and predictors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 26 Suppl 3, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.H.; Zahedi, M.; Darvish Moghadam, S.; Shafieipour, S.; HayatBakhsh Abbasi, M. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: the first study in iran. Middle East J Dig Dis 2015, 7, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Parodi, A.; Dulbecco, P.; Savarino, E.; Giannini, E.G.; Bodini, G.; Corbo, M.; Isola, L.; De Conca, S.; Marabotto, E.; Savarino, V. Positive glucose breath testing is more prevalent in patients with IBS-like symptoms compared with controls of similar age and gender distribution. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009, 43, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Yadav, A.; Fatima, B.; Agrahari, A.P.; Misra, A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A case-control study. Indian J Gastroenterol 2022, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.; Tornblom, H.; Simren, M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth as a cause for irritable bowel syndrome: guilty or not guilty? Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017, 33, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Tao, H.; Li, L.; Xuan, J.; Wang, F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with clinical relapse in patients with quiescent Crohn's disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med 2022, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulygina, Y.O., M.; Skalinskaya, M.; Alikina, T.; Kabilov, M.; Lukinov, V.; Sitkin, S. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with Crohn’s disease is not only associated with a more severe disease, but is also marked by dramatic changes in the gut microbiome. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. [CrossRef]

- Bertges, E.R.; Chebli, J.M.F. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Crohn's Disease: A Retrospective Study at a Referral Center. Arq Gastroenterol 2020, 57, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzl, J.; Grohl, K.; Kafel, A.; Nagl, S.; Muzalyova, A.; Golder, S.K.; Ebigbo, A.; Messmann, H.; Schnoy, E. Impact of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Gastrointestinal Disorders-A Retrospective Analysis in a Tertiary Single Center and Review of the Literature. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Huo, X.; Wang, J. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and evaluation of intestinal barrier function in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Transl Res 2021, 13, 6605–6610. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, M.; Mathur, R.; Chang, C. Gas and the microbiome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2013, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mekelburg, S.; Tafesh, Z.; Coburn, E.; Weg, R.; Malik, N.; Webb, C.; Hammad, H.; Scherl, E.; Bosworth, B.P. Testing and Treating Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Reduces Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci 2018, 63, 2439–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Morrison, M.; Burger, D.; Martin, N.; Rich, J.; Jones, M.; Koloski, N.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J.; Holtmann, G.J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019, 49, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Fan, H.; Huo, X.; Dong, L.; Duan, Z. Relationship between Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Peripheral Blood ET, TLR2 and TLR4 in Ulcerative Colitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2020, 30, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, M.A.; Jiman-Fatani, A.A.; Saadah, O.I. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth among patients with celiac disease unresponsive to a gluten free diet. Turk J Gastroenterol 2020, 31, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Thite, P.; Hansen, T.; Kendall, B.J.; Sanders, D.S.; Morrison, M.; Jones, M.P.; Holtmann, G. Links between celiac disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 37, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prizont, R.; Hersh, T.; Floch, M.H. Jejunal bacterial flora in chronic small bowel disease. I. Celiac disease. II. Regional enteritis. Am J Clin Nutr 1970, 23, 1602–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Brandimarte, G.; Giorgetti, G. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in celiac patients with persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten withdrawal. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraquelli, M.; Bardella, M.T.; Peracchi, M.; Cesana, B.M.; Bianchi, P.A.; Conte, D. Gallbladder emptying and somatostatin and cholecystokinin plasma levels in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999, 94, 1866–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardella, M.T.; Fraquelli, M.; Peracchi, M.; Cesana, B.M.; Bianchi, P.A.; Conte, D. Gastric emptying and plasma neurotensin levels in untreated celiac patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000, 35, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Barton, S.H.; Rosenblatt, J.E.; Murray, J.A. Prevalence of small intestine bacterial overgrowth diagnosed by quantitative culture of intestinal aspirate in celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009, 43, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.S.; Minaya, M.T.; Cheng, J.; Connor, B.A.; Lewis, S.K.; Green, P.H. Double-blind randomized controlled trial of rifaximin for persistent symptoms in patients with celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci 2011, 56, 2939–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, R.P.G.; Winter, G. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and Celiac disease - coincidence or causation? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 14, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Goel, A.; Quigley, E.M.M. Gut microbiota abnormalities, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An emerging paradigm. Indian J Gastroenterol 2020, 39, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudan, A.; Kozlowska-Petriczko, K.; Wunsch, E.; Bodnarczuk, T.; Stachowska, E. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: What Do We Know in 2023? Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, M.; Grys, I.; Kukla, M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Exp Hepatol 2019, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, L.; Valenza, V.; La Torre, G.; Montalto, M.; Cammarota, G.; Ricci, R.; Masciana, R.; Forgione, A.; Gabrieli, M.L.; Perotti, G.; et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, A.; Fialho, A.; Thota, P.; McCullough, A.J.; Shen, B. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Is Associated with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2016, 25, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Mao, L.; Wang, L.; Quan, X.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Dai, F. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and orocecal transit time in patients of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 33, e535–e539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudan, A.; Jamiol-Milc, D.; Hawrylkowicz, V.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K.; Stachowska, E. The Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Liver Diseases: NAFLD, NASH, Fibrosis, Cirrhosis-A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolasevic, I.; Delija, B.; Mijic, A.; Stevanovic, T.; Skenderevic, N.; Sosa, I.; Krznaric-Zrnic, I.; Abram, M.; Krznaric, Z.; Domislovic, V.; et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosed by transient elastography and liver biopsy. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75, e13947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, L.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, Y. Association of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanov, Y.M.; Zavhorodnia, N.Y.; Yagmur, V.B.; Lukianenko, O.Y.; Zygalo, E.V. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with small intestine bacterial overgrowth in obese children. Wiad Lek 2019, 72, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshimoghaddam, F.; Alizadeh, M. Contribution of gut microbiota to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathways of mechanisms. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 44, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GuimarAes, V.M.; Santos, V.N.; Borges, P.S.A.; JLR, D.E.F.; Grillo, P.; Parise, E.R. Peripheral Blood Endotoxin Levels Are Not Associated with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease without Cirrhosis. Arq Gastroenterol 2020, 57, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkolfakis, P.; Tziatzios, G.; Leite, G.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Xirouchakis, E.; Panayiotides, I.G.; Karageorgos, A.; Millan, M.J.; Mathur, R.; Weitsman, S.; et al. Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdottir, S.A.; Sadik, R.; Shev, S.; Simren, M.; Sjovall, H.; Stotzer, P.O.; Abrahamsson, H.; Olsson, R.; Bjornsson, E.S. Small intestinal motility disturbances and bacterial overgrowth in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol 2003, 98, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesta, J.; Silva, M.; Thompson, L.; del Canto, E.; Defilippi, C. [Bacterial overgrowth in small intestine in patients with liver cirrhosis]. Rev Med Chil 1991, 119, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maslennikov, R.; Pavlov, C.; Ivashkin, V. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in cirrhosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol Int 2018, 12, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslennikov, R.; Ivashkin, V.; Efremova, I.; Poluektova, E.; Kudryavtseva, A.; Krasnov, G. Gut dysbiosis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth as independent forms of gut microbiota disorders in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2022, 28, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, G.; Jesudian, A.B. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients With Cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2019, 9, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Tian, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Pan, H.; Jiang, Z. Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhotic Patients and Risk of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 2469513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.B.; Paik, C.N.; Sung, H.J.; Chung, W.C.; Lee, K.M.; Yang, J.M.; Choi, M.G. Breath hydrogen and methane are associated with intestinal symptoms in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2015, 15, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signoretti, M.; Stigliano, S.; Valente, R.; Piciucchi, M.; Delle Fave, G.; Capurso, G. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014, 48 Suppl 1, S52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Chonchubhair, H.M.; Bashir, Y.; Dobson, M.; Ryan, B.M.; Duggan, S.N.; Conlon, K.C. The prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in non-surgical patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI). Pancreatology 2018, 18, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, H.M.; He, F.; Li, B.Y.; Li, X.C. Association between acute pancreatitis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth assessed by hydrogen breath test. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 8591–8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.B.; Paik, C.N.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.J. Association between increased breath hydrogen methane concentration and prevalence of glucose intolerance in acute pancreatitis. J Breath Res 2020, 14, 026006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kurdi, B.; Babar, S.; El Iskandarani, M.; Bataineh, A.; Lerch, M.M.; Young, M.; Singh, V.P. Factors That Affect Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Chronic Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2019, 10, e00072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.Q.; Cui, M.Y.; Jiang, Q.L.; Wang, J.J.; Fan, M.Y.; Lu, Y.Y. Characterization of Duodenal Microbiota in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis and Healthy Controls. Dig Dis Sci 2023, 68, 3341–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.A.; Baker, J.R.; Wamsteker, E.J.; Saad, R.; DiMagno, M.J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Is Common in Chronic Pancreatitis and Associates With Diabetes, Chronic Pancreatitis Severity, Low Zinc Levels, and Opiate Use. Am J Gastroenterol 2019, 114, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyger, G.; Baron, M. Gastrointestinal manifestations of scleroderma: recent progress in evaluation, pathogenesis, and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012, 14, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjogren, R.W. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum 1994, 37, 1265–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Tandon, P.; Gohel, T.; Corrigan, M.L.; Coughlin, K.L.; Shatnawei, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Kirby, D.F. Gastrointestinal Manifestations, Malnutrition, and Role of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition in Patients With Scleroderma. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015, 49, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Collinot, G.; Madrigal-Santillan, E.O.; Martinez-Bencomo, M.A.; Carranza-Muleiro, R.A.; Jara, L.J.; Vera-Lastra, O.; Montes-Cortes, D.H.; Medina, G.; Cruz-Dominguez, M.P. Effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii and Metronidazole for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Systemic Sclerosis. Dig Dis Sci 2020, 65, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrisroe, K.; Baron, M.; Frech, T.; Nikpour, M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2020, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadpanich, K.; Soison, P.; Chunlertrith, K.; Mairiang, P.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Sangchan, A.; Suttichaimongkol, T.; Foocharoen, C. Prevalence and associated factors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth among systemic sclerosis patients. Int J Rheum Dis 2019, 22, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.; De Palma, G.; Zou, H.; Bazzaz, A.H.Z.; Verdu, E.; Baker, B.; Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Khalidi, N.; Larche, M.J.; Beattie, K.A.; et al. Fecal microbiome differs between patients with systemic sclerosis with and without small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2021, 6, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Pakeerathan, V.; Jones, M.P.; Kashyap, P.C.; Virgo, K.; Fairlie, T.; Morrison, M.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Holtmann, G.J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Complicating Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2023, 29, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fynne, L.; Worsoe, J.; Gregersen, T.; Schlageter, V.; Laurberg, S.; Krogh, K. Gastrointestinal transit in patients with systemic sclerosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011, 46, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarino, E.; Mei, F.; Parodi, A.; Ghio, M.; Furnari, M.; Gentile, A.; Berdini, M.; Di Sario, A.; Bendia, E.; Bonazzi, P.; et al. Gastrointestinal motility disorder assessment in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013, 52, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellaard, F.; Sauerbruch, T.; Luderschmidt, C.H.; Leisner, B.; Paumgartner, G. Intestinal involvement in progressive systemic sclerosis detected by increased unconjugated serum bile acids. Gut 1987, 28, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Li, X.Q.; Jiang, Z. Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2021, 40, 3039–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.P.; Zhang, X. Gastrointestinal complications of systemic sclerosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 7062–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marie, I.; Leroi, A.M.; Menard, J.F.; Levesque, H.; Quillard, M.; Ducrotte, P. Fecal calprotectin in systemic sclerosis and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2015, 14, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polkowska-Pruszynska, B.; Gerkowicz, A.; Rawicz-Pruszynski, K.; Krasowska, D. The Role of Fecal Calprotectin in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, E.; Russo, E.; Amedei, A.; Bellando Randone, S. Fecal microbiome in systemic sclerosis, in search for the best candidate for microbiota-targeted therapy for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth control. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2022, 7, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebauer, J.; Volk, H.D.; Kemp, M.; Dominguez, M.; Schumann, R.R.; Rauchhaus, M.; Poole-Wilson, P.A.; Coats, A.J.; Anker, S.D. Endotoxin and immune activation in chronic heart failure: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 1999, 353, 1838–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandek, A.; Rauchhaus, M.; Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. The emerging role of the gut in chronic heart failure. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2008, 11, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. Inflammatory mediators in chronic heart failure: an overview. Heart 2004, 90, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qi, B.; Cui, X.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Li, F.; Shen, D.; Zhang, X.; et al. Association of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth With Heart Failure and Its Prediction for Short-Term Outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e015292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollar, A.; Marrachelli, V.G.; Nunez, E.; Monleon, D.; Bodi, V.; Sanchis, J.; Navarro, D.; Nunez, J. Bacterial metabolites trimethylamine N-oxide and butyrate as surrogates of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with a recent decompensated heart failure. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chu, M.; Wang, D.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J. Risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J Med Microbiol 2023, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Xie, N.C.; Xu, H.L.; Lian, Y.J. Association between small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth and deep vein thrombosis in patients with spinal cord injuries. J Thromb Haemost 2017, 15, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Ding, R.; Wu, F.; Wu, Z.; Liang, C. Excess Alcohol Consumption: A Potential Mechanism Behind the Association Between Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Coronary Artery Disease. Dig Dis Sci 2018, 63, 3516–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Wang, G.; Xian, R.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Cui, L. Association between Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Subclinical Atheromatous Plaques. J Clin Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Pompili, M.; Di Stasio, E.; Zocco, M.A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Flore, R. Subclinical atherosclerosis is linked to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth via vitamin K2-dependent mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojetti, V.; Pitocco, D.; Scarpellini, E.; Zaccardi, F.; Scaldaferri, F.; Gigante, G.; Gasbarrini, G.; Ghirlanda, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth and type 1 diabetes. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2009, 13, 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Bhansali, A.; Bhadada, S.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, J.; Singh, K. Orocecal transit time and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in type 2 diabetes patients from North India. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011, 13, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, X.Q. The prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 2022, 14, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Stratigou, T.; Tsagarakis, S. Microbiome and diabetes: Where are we now? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018, 146, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborska, K.E.; Cummings, B.P. Rethinking Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling for Type 2 Diabetes Treatment. Curr Diab Rep 2018, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Ban, Y.; Wang, B.; Hou, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; et al. Application of methane and hydrogen-based breath test in the study of gestational diabetes mellitus and intestinal microbes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2021, 176, 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.H.; Mu, B.; Pan, D.; Shi, Y.N.; Yuan, J.H.; Guan, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.Y.; Guo, L. Association between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and beta-cell function of type 2 diabetes. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060520937866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvit, K.B.; Kharchenko, N.V.; Kharchenko, V.V.; Chornenka, O.I.; Chornovus, R.I.; Dorofeeva, U.S.; Draganchuk, O.B.; Slaba, O.M. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in the pathogenesis of hyperlipidemia. Wiad Lek 2019, 72, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, G.K.; Mullin, G.E. The Gut Microbiome and Obesity. Curr Oncol Rep 2016, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ma, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, C.; Nie, Y. Insights into the role of gut microbiota in obesity: pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic perspectives. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocka, M.S., M. Bogdański, P. Rola mikroflory jelitowej w patogenezie i leczeniu otyłości oraz zespołu metabolicznego. Forum Zaburzeń Metabolicznych 2015, 6, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wijarnpreecha, K.; Werlang, M.E.; Watthanasuntorn, K.; Panjawatanan, P.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Gomez, V.; Lukens, F.J.; Ungprasert, P. Obesity and Risk of Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2020, 65, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, B.C.; Lee, D.; Miller, L.S.; Vegesna, A.; Yolken, R.; Severance, E.; Prandovszky, E.; Zheng, X.E.; Mullin, G.E. Obesity increases the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid, A.M.; Poniachik, J.; Quera, R.; Defilippi, C. Small intestinal clustered contractions and bacterial overgrowth: a frequent finding in obese patients. Dig Dis Sci 2011, 56, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierardi, E.; Losurdo, G.; Sorrentino, C.; Giorgio, F.; Rossi, G.; Marinaro, A.; Romagno, K.R.; Di Leo, A.; Principi, M. Macronutrient intakes in obese subjects with or without small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: an alimentary survey. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016, 51, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushref, M.A.; Srinivasan, S. Effect of high fat-diet and obesity on gastrointestinal motility. Ann Transl Med 2013, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.; Chen, J.D. Alterations of gastrointestinal motility in obesity. Obes Res 2004, 12, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciobanu, L.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in endocrine diseases. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2011, 121, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechmann, T.; Sperlbaum, A.; Schmiegel, W. Levothyroxine therapy and impaired clearance are the strongest contributors to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Results of a retrospective cohort study. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Li, X.; Ahmed, A.; Wu, D.; Liu, L.; Qiu, J.; Yan, Y.; Jin, M.; Xin, Y. Gut microbe analysis between hyperthyroid and healthy individuals. Curr Microbiol 2014, 69, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penhale, W.J.; Young, P.R. The influence of the normal microbial flora on the susceptibility of rats to experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Exp Immunol 1988, 72, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritano, E.C.; Bilotta, A.L.; Gabrielli, M.; Scarpellini, E.; Lupascu, A.; Laginestra, A.; Novi, M.; Sottili, S.; Serricchio, M.; Cammarota, G.; et al. Association between hypothyroidism and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 4180–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, P.; Chojnacki, J.; Kaczka, A.; Pawlowicz, M.; Rudnicki, C.; Chojnacki, C. [Thyroid dysfunction in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth]. Pol Merkur Lekarski 2018, 44, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Xu, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Hao, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Wu, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, M.; et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Subclinical Hypothyroidism of Pregnant Women. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 604070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rukavina Mikusic, N.L.; Kouyoumdzian, N.M.; Choi, M.R. Gut microbiota and chronic kidney disease: evidences and mechanisms that mediate a new communication in the gastrointestinal-renal axis. Pflugers Arch 2020, 472, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Dure-Smith, B.; Miller, R.; Mirahmadi, M.K. Pathology of gastrointestinal tract in chronic hemodialysis patients: an autopsy study of 78 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 1985, 80, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrios, C.; Beaumont, M.; Pallister, T.; Villar, J.; Goodrich, J.K.; Clark, A.; Pascual, J.; Ley, R.E.; Spector, T.D.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Gut-Microbiota-Metabolite Axis in Early Renal Function Decline. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0134311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strid, H.; Simren, M.; Stotzer, P.O.; Ringstrom, G.; Abrahamsson, H.; Bjornsson, E.S. Patients with chronic renal failure have abnormal small intestinal motility and a high prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Digestion 2003, 67, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nallu, A.; Sharma, S.; Ramezani, A.; Muralidharan, J.; Raj, D. Gut microbiome in chronic kidney disease: challenges and opportunities. Transl Res 2017, 179, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Hayashi, H.; Watanabe, M.; Ueda, K.; Yamato, H.; Yoshioka, T.; Motojima, M. Uremic toxins overload accelerates renal damage in a rat model of chronic renal failure. Nephron Exp Nephrol 2003, 95, e111–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thadhani, R.; Pascual, M.; Bonventre, J.V. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kim, C.J.; Go, Y.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, M.G.; Oh, S.W.; Cho, W.Y.; Im, S.H.; Jo, S.K. Intestinal microbiota control acute kidney injury severity by immune modulation. Kidney Int 2020, 98, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodpoor, F.; Rahbar Saadat, Y.; Barzegari, A.; Ardalan, M.; Zununi Vahed, S. The impact of gut microbiota on kidney function and pathogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 93, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdaleno-Tapial, J.; Lopez-Marti, C.; Garcia-Legaz-Martinez, M.; Martinez-Domenech, A.; Partarrieu-Mejias, F.; Casanova-Esquembre, A.; Lorca-Sprohnle, J.; Labrandero-Hoyos, C.; Penuelas-Leal, R.; Sierra-Talamantes, C.; et al. Contact Allergy in Patients with Rosacea. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2022, 113, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, H.; Paradiso, M.; Hennessy, K.; Seminario-Vidal, L. Rosacea and the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.Y.; Chi, C.C. Rosacea, Germs, and Bowels: A Review on Gastrointestinal Comorbidities and Gut-Skin Axis of Rosacea. Adv Ther 2021, 38, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, A.; Paolino, S.; Greco, A.; Drago, F.; Mansi, C.; Rebora, A.; Parodi, A.; Savarino, V. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: clinical effectiveness of its eradication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008, 6, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branisteanu, D.E.; Cojocaru, C.; Diaconu, R.; Porumb, E.A.; Alexa, A.I.; Nicolescu, A.C.; Brihan, I.; Bogdanici, C.M.; Branisteanu, G.; Dimitriu, A.; et al. Update on the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis (Review). Exp Ther Med 2022, 23, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Cordara, V.; Paudice, M.; Herzum, A.; Parodi, A. Oral psoriasis and SIBO: is there a link? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018, 32, e368–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Indemini, E.; Savarino, V.; Parodi, A. Psoriasis and small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Int J Dermatol 2018, 57, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, N.; Moneghini, L.; Varoni, E.M.; Lodi, G. Nodular migratory tongue lesions: Atypical geographic tongue or a new entity? Oral Dis 2023, 29, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; De Strooper, B.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chetelat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, J.A.; Potashkin, J.A. The Impact of Disease Comorbidities in Alzheimer's Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 631770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, J.; Wang, Y.T.; Mamun, K.; Tay, S.Y.; Doshi, K.; Hameed, S.; Ting, S.K. Assessment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2021, 30(3), 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, K.; Mulak, A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2022, 129, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, Z. Association of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Pathog 2021, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.L.; Liu, L.; Song, Z.X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.L.; Li, H.H. Prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Chinese patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2016, 123, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Bove, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Petracca, M.; Zocco, M.A.; Ragazzoni, E.; Barbaro, F.; Piano, C.; Fortuna, S.; Tortora, A.; et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2013, 28, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.H.; Mahadeva, S.; Thalha, A.M.; Gibson, P.R.; Kiew, C.K.; Yeat, C.M.; Ng, S.W.; Ang, S.P.; Chow, S.K.; Tan, C.T.; et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kessel, S.P.; El Aidy, S. Contributions of Gut Bacteria and Diet to Drug Pharmacokinetics in the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danau, A.; Dumitrescu, L.; Lefter, A.; Tulba, D.; Popescu, B.O. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth as Potential Therapeutic Target in Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Duan, Y.; Han, X.; Dong, H.; Geng, J. Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Multiple Sclerosis: a Case-Control Study from China. J Neuroimmunol 2016, 301, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, D.A.; Kern, J.K.; Geier, M.R. A Comparison of the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) for the Quantitative Evaluation of Autism. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil 2013, 6, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finegold, S.M.; Summanen, P.H.; Downes, J.; Corbett, K.; Komoriya, T. Detection of Clostridium perfringens toxin genes in the gut microbiota of autistic children. Anaerobe 2017, 45, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegold, S.M.; Dowd, S.E.; Gontcharova, V.; Liu, C.; Henley, K.E.; Wolcott, R.D.; Youn, E.; Summanen, P.H.; Granpeesheh, D.; Dixon, D.; et al. Pyrosequencing study of fecal microflora of autistic and control children. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yu, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.; Lu, N.; Liu, N. Hydrogen breath test to detect small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a prevalence case-control study in autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018, 27, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, G.; Su, S. Effect of Compound Lactic Acid Bacteria Capsules on the Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Patients with Depression and Diabetes: A Blinded Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 6721695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossewska, J.; Bierlit, K.; Trajkovski, V. Personality, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients with Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome. The Polish Preliminary Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojnacki, C.; Konrad, P.; Blonska, A.; Medrek-Socha, M.; Przybylowska-Sygut, K.; Chojnacki, J.; Poplawski, T. Altered Tryptophan Metabolism on the Kynurenine Pathway in Depressive Patients with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, C.; Poplawski, T.; Konrad, P.; Fila, M.; Blasiak, J.; Chojnacki, J. Antimicrobial treatment improves tryptophan metabolism and mood of patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2022, 19, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowska, A.; Wojtowicz, J.; Walkowiak, J. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth is frequent in cystic fibrosis: combined hydrogen and methane measurements are required for its detection. Acta Biochim Pol 2009, 56, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisle, R.C. Altered transit and bacterial overgrowth in the cystic fibrosis mouse small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007, 293, G104–G111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnari, M.; De Alessandri, A.; Cresta, F.; Haupt, M.; Bassi, M.; Calvi, A.; Haupt, R.; Bodini, G.; Ahmed, I.; Bagnasco, F.; et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in cystic fibrosis: a randomized case-controlled clinical trial with rifaximin. J Gastroenterol 2019, 54, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrecchia, E.; Sicignano, L.L.; La Regina, M.; Nucera, G.; Patisso, I.; Cerrito, L.; Montalto, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Manna, R. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Affects the Responsiveness to Colchicine in Familial Mediterranean Fever. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 2017, 7461426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Xu, L.; Tian, Z. Association between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and toll-like receptor 4 in patients with pancreatic carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Turk J Gastroenterol 2019, 30, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z. Effect of probiotics on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer. Turk J Gastroenterol 2016, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Prevalence and treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in postoperative patients with colorectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol 2016, 4, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savva, K.V.; Hage, L.; Belluomo, I.; Gummet, P.; Boshier, P.R.; Peters, C.J. Assessment of the Burden of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) in Patients After Oesophagogastric (OG) Cancer Resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2022, 26, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.X.; Ma, Y.J.; Chen, G.Y.; Gao, X.; Yang, L. [Relationship of TLR2 and TLR4 expressions on the surface of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to small intestinal bacteria overgrowth in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2019, 27, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).