Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Proximal Renal Tubule

3. Executors of Phosphate Reabsorption: Renal Phosphate Transporters and NHERF1 (Na+/H+ Exchange Regulatory Cofactor 1)

3.1. The Renal Phosphate Transporters

3.1.1. NaPi-2a

NaPi-2a Partitioning Into Lipid Rafts.

3.1.2. NaPi-2c

3.1.3. PiT-2

3.2. NHERF1-the Systems Manager

3.2.1. NHERF1

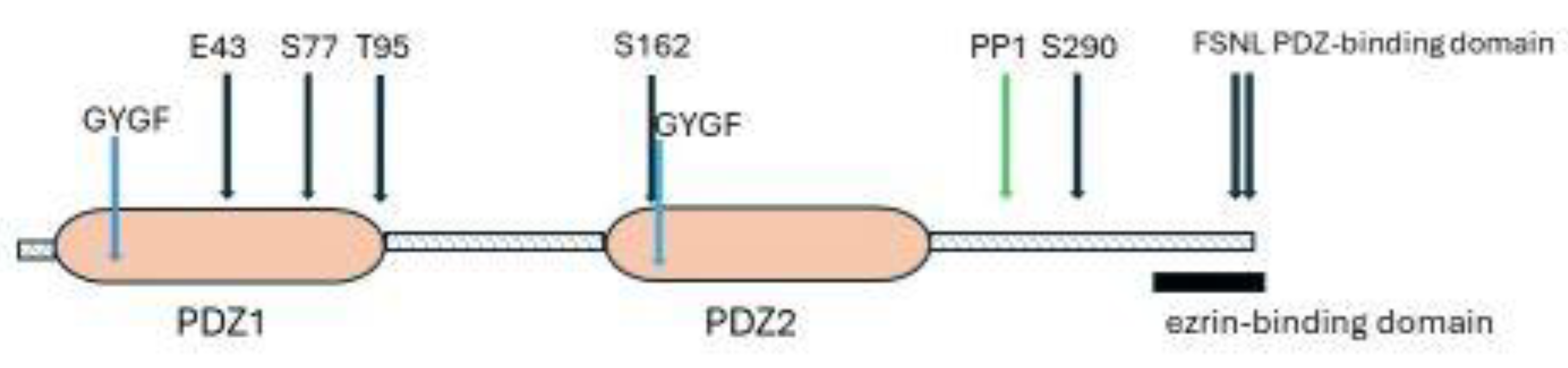

Structure

3.3. Hormonal Regulation of Phosphate Transport by NaPt-2a

4. Regulation of NaPi-2a by Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and Parathyroid Hormone -Related Protein PTHrP

4.1. PTH

4.2. PTHrP

4.3. The PTH/PTHrP Receptor (PTH1R)

4.3.1. Structure

4.3.2. PTH/PTHrP Binding

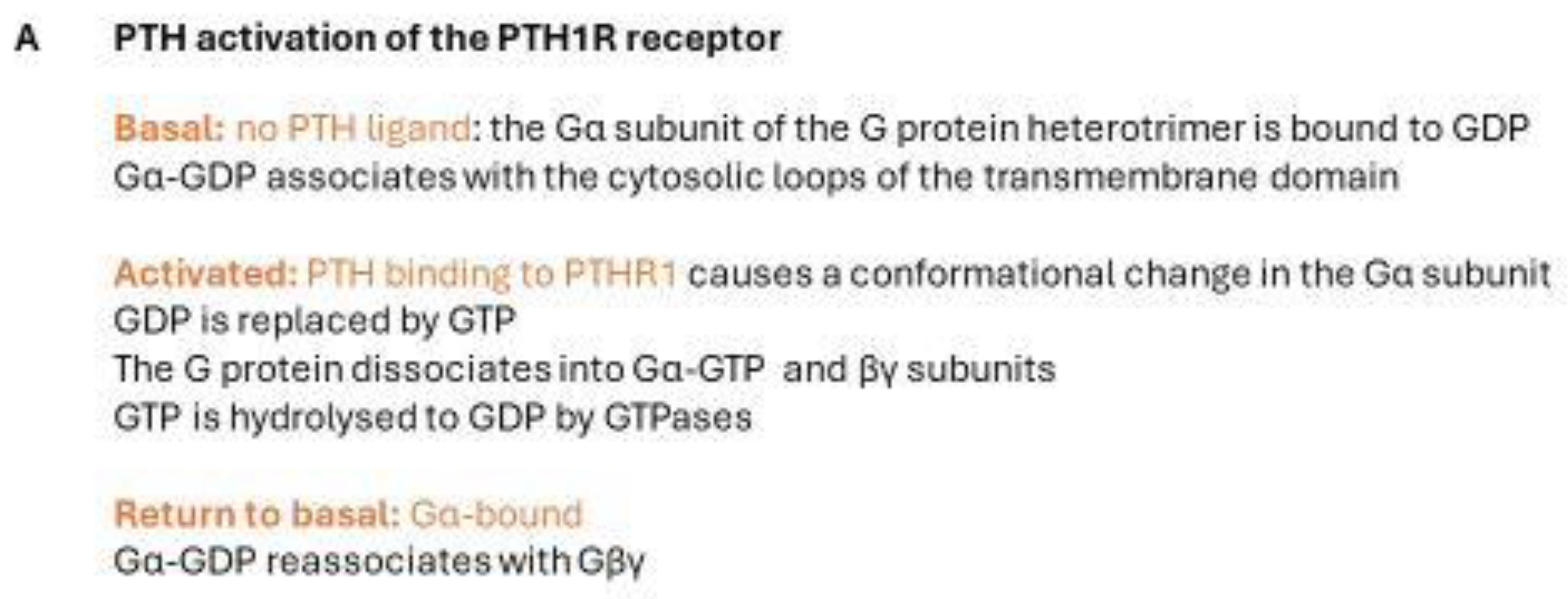

4.3.3. Signalling Pathways and Signalling Bias

4.3.4. Termination of Signalling

RGS14 (Regulator of G Protein Signalling 14)

Receptor-Activity-Modifying Proteins (RAMPs).

4.3.5. Endosomal Signalling

4.3.6. Inherited Defects of PTH/PTHrP Receptor Signalling

4.4. Epac1 (Exchange Protein Directly Activated by cAMP 1)

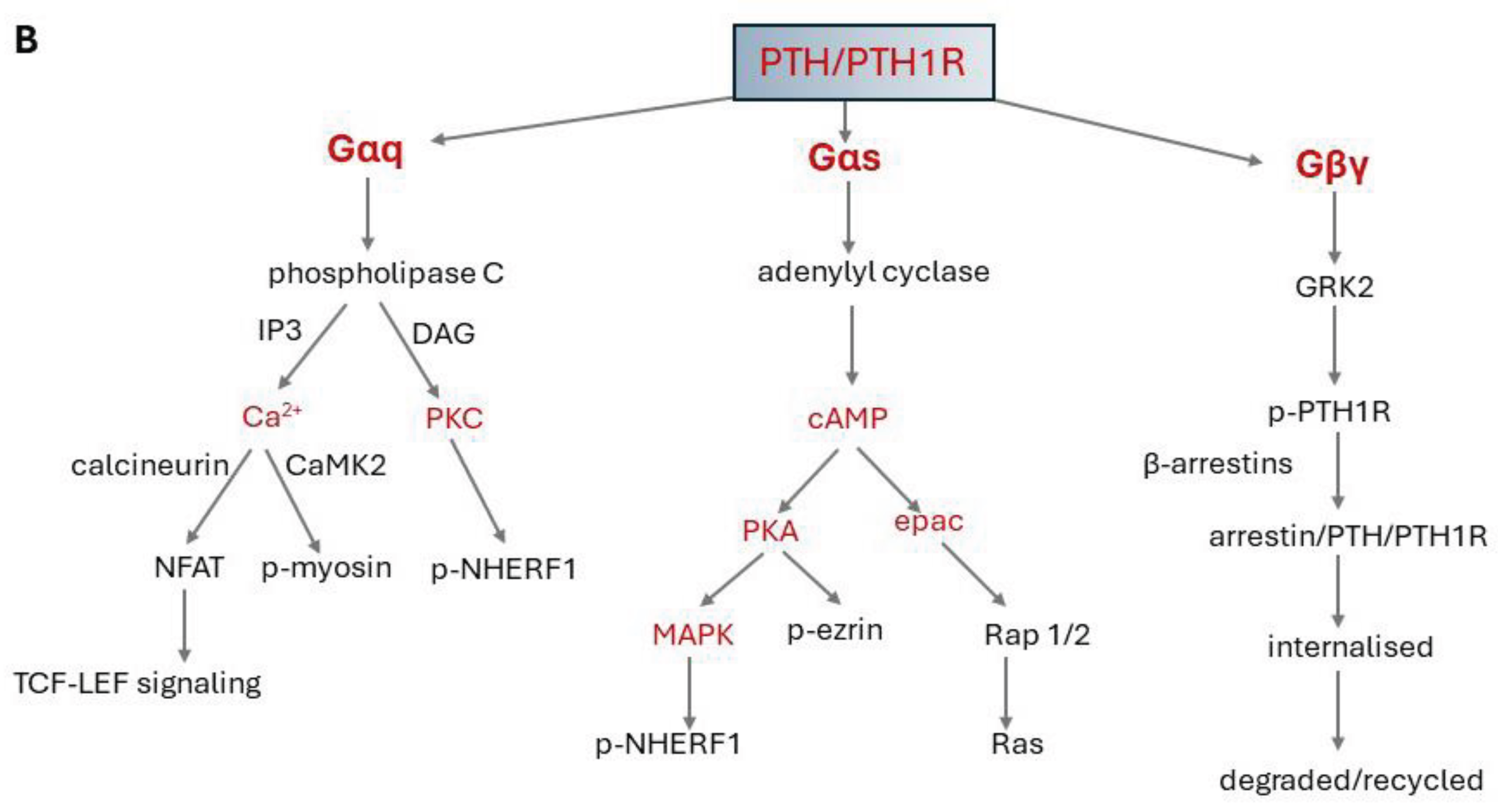

4.4.1. Structure

4.4.2. Actions of Epac1 in the Proximal Tubules

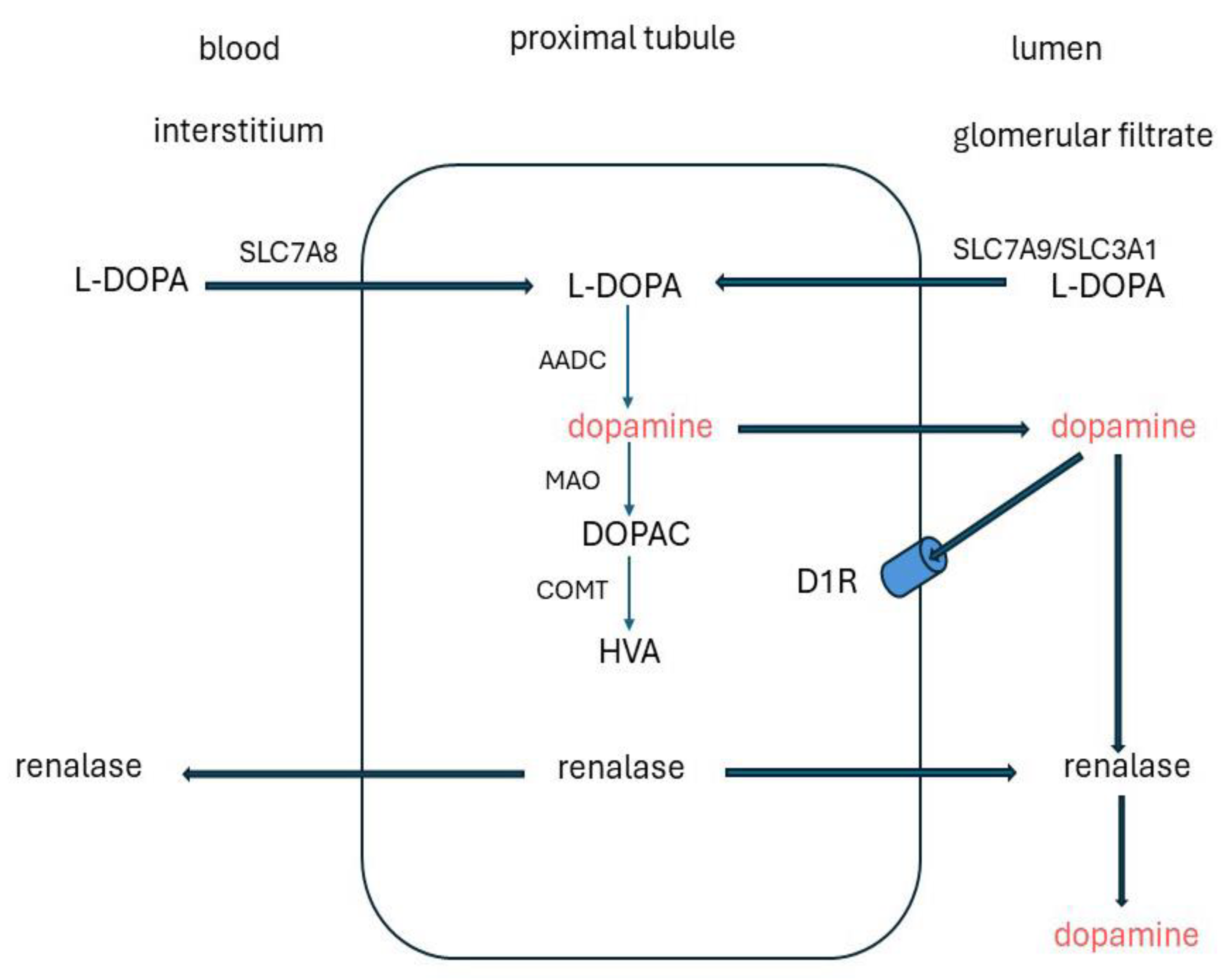

5. Dopamine

5.1. Sources and Degradation

5.2. Dopamine Receptors and Signalling.

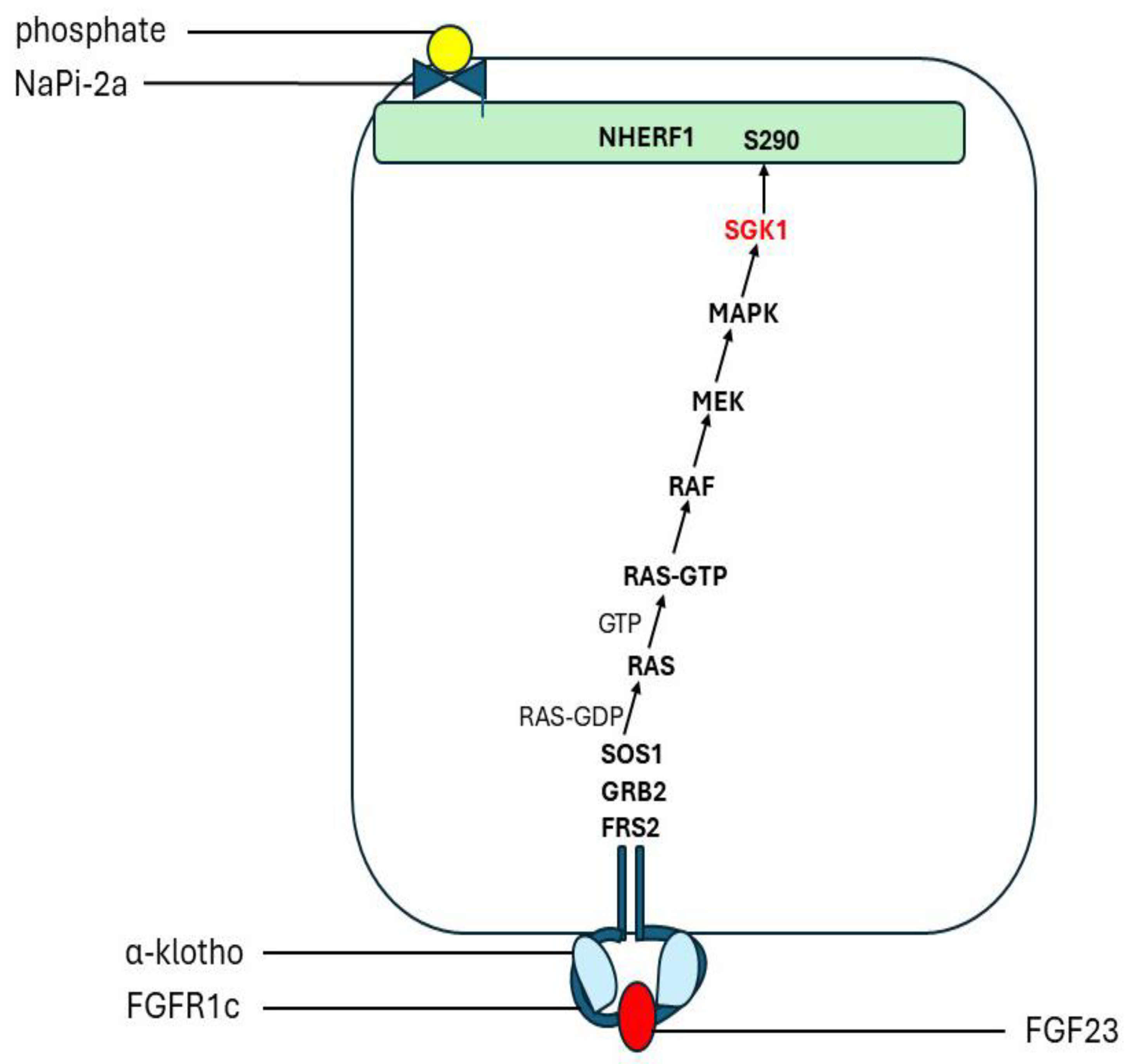

6. FGF23 and FGFR1C/KLOTHO Receptor

6.1. Physiological Factors Increasing/Decreasing FGF23 Production

6.2. Structure

6.3. Renal Receptors and α-klotho

6.3.1. α-Klotho

6.4. Signal Transduction and Signalling

7. Mechanisms of Hormonal Regulation of Phosphate Transport by NaPt-2a

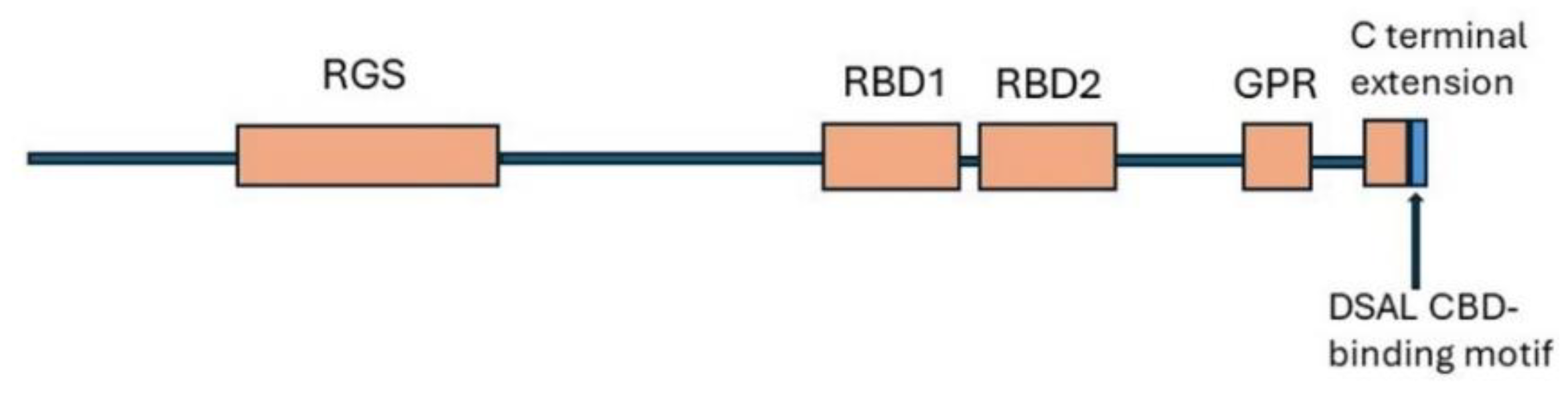

8. Regulator of G protein Signalling 14 (RGS14)

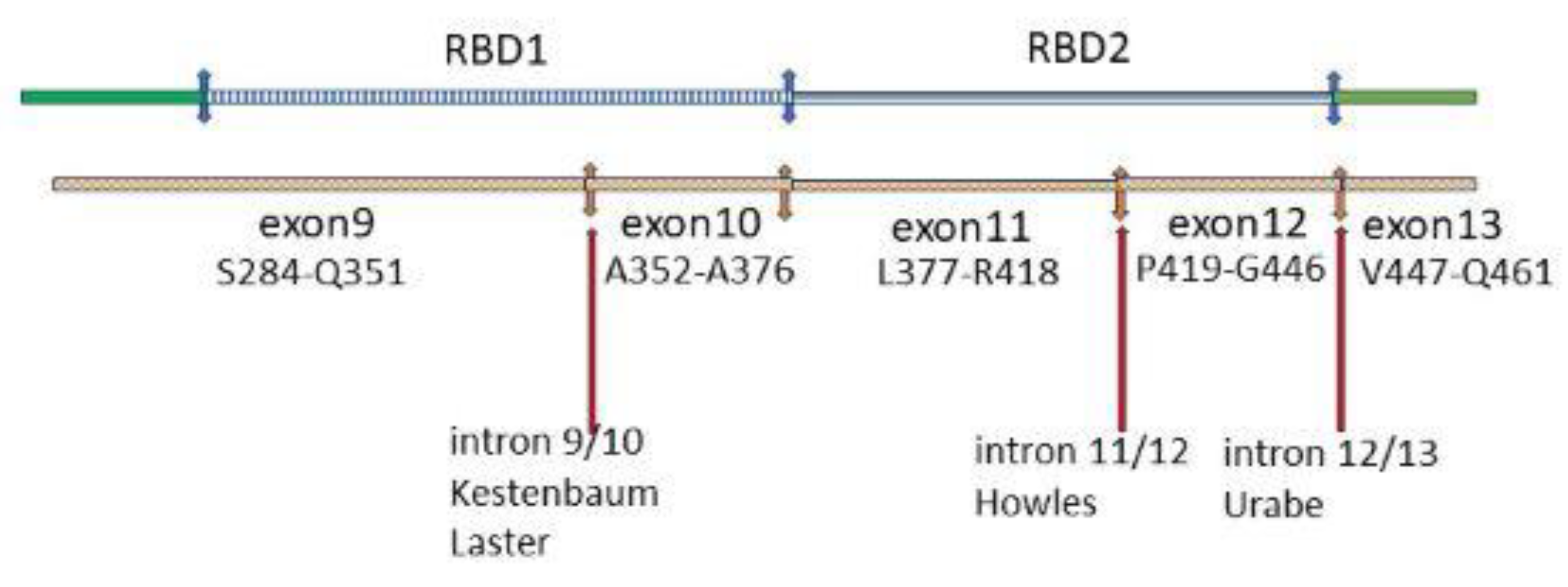

8.1. Structure

8.2. RGS14 Inhibition of PTH Regulation of NaPi-2a

8.3. RGS14 Polymorphisms in GWAS Studies

9. Growth Hormone and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1)

10. Dietary Phosphate

10.1. Acute Changes in Dietary Phosphate

10.1.1. Low Phosphate Intake:

10.1.2. High Phosphate Intake:

10.2. Chronic Changes in Dietary Phosphate

10.3. High Dietary Phosphate and Renal Dopamine Excretion

11. Tumour-Induced Osteomalacia (TIO)

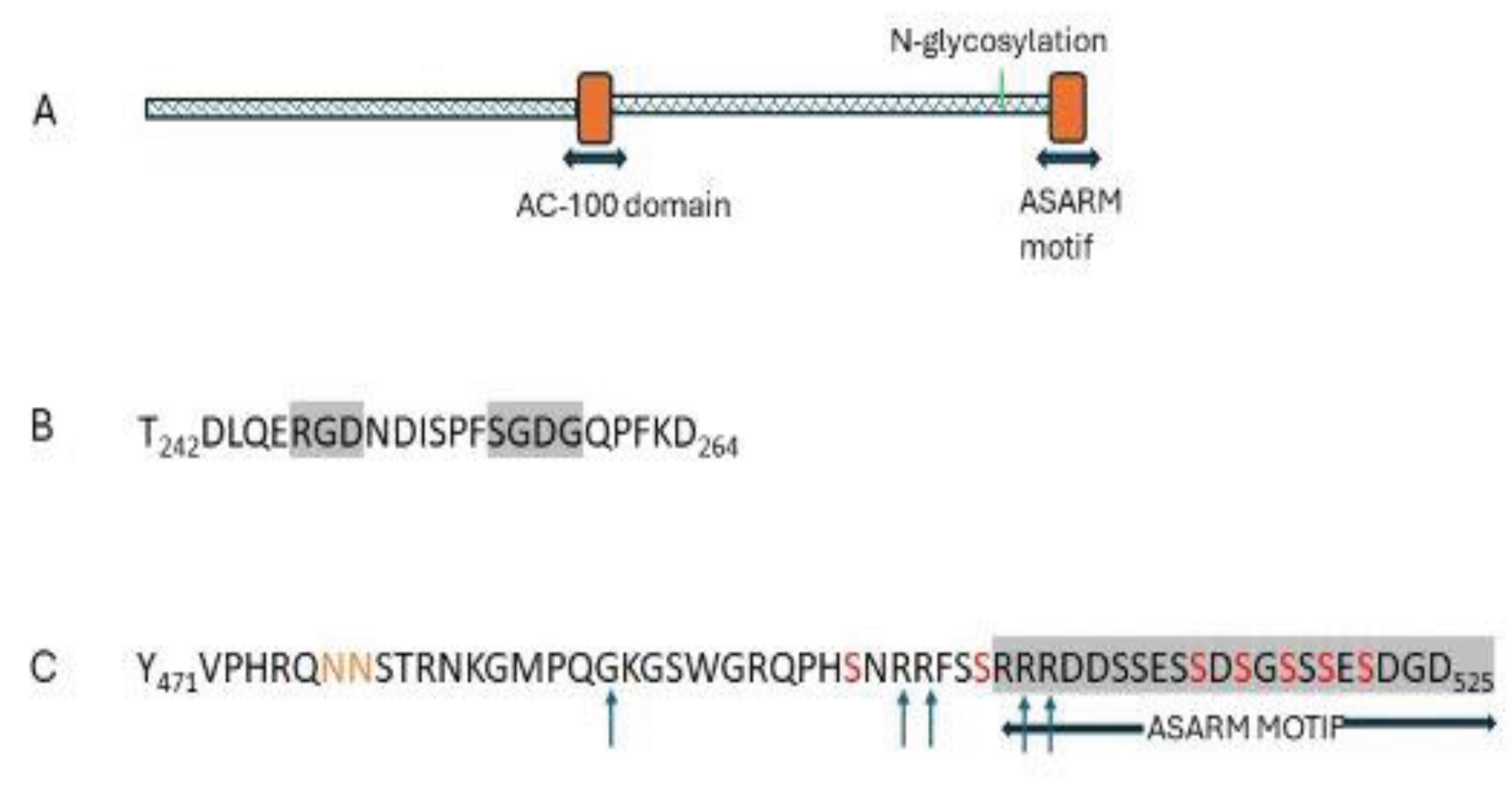

11.1. MEPE

11.1.1. Mechanism Causing Hyper-Phosphaturia

11.2. sFRP4 Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 4 (sFRP4)

11.3. Fibroblast Growth Factor 7 (FGF7)

12. Clinical Applications of the Expanding Knowledge of Phosphate Transport

13. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

- Whether interaction of full length PTH the PTH1R receptor and G-signalling are the same as for PTH1-34 fragment.

- (2)

- Clearer definition of the signalling pathway via cAMP and PKA to NHERF1. It appears speculative at present.

- (3)

- Clearer definition of the signalling pathway of IGFR which increases renal phosphate absorption.

- (4)

- The form of PTH which normally activates proximal tubule apical PTH1R. Activation by filtered intact PTH or N-terminal PTH fragments seems an imprecise regulatory mechanism for such a finely controlled reabsorption system. How far is locally produced PTHrP involved?

- (5)

- The function of PTHrP in the proximal tubules post-natally.

- (6)

- How PTH signalling at the apical and basolateral membranes in the proximal tubule are co-ordinated

- (7)

- The location of NHERF1 at the BBM? Logically it should be in the (long) cilia close to apically-sited NaPi-2a, but findings conflict.

- (8)

- The roles of RAMPS in PTH/PTH1R signalling.

- (9)

- The function of the internal PDZ-binding motif of NaPi-2a.

- (10)

- Whether RGS14 has roles in regulating phosphate transport through inactivation of PTH/PTH1R signalling, and/or in humans through blocking NaPi-2a inactivation by PTH.

- (11)

- Whether Epac is stimulated in parallel with PKA by PTH/PTH1R. If it is, do PKA and Epac operate an activation/inhibitory partnership to regulate PTH activity?

- (12)

- The dysfunctional protein activity which is being highlighted in GWAS studies of calcium stone formers.

- (13)

- Whether MEPE has a physiological role in the kidneys.

- (14)

- The on-going research into the molecular mechanisms of renal phosphate absorption is revealing an amazingly intricate system which has evolved over millions of years. The emerging findings are providing greater insight into failures of the process, and indicating new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Knochel JP. Hypophosphatemia and phosphorus deficiency. In The Kidney, 4TH ed.; Brenner BM, Rector FC, Jr., Eds.; W.B. Saunders Company, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.: West Philadelphia, United States of America, 1991; Volume 1 Chapter 21, pp. 888-915.

- Fukumoto S. Phosphate metabolism and vitamin D. Bonekey Rep. 2014 Feb 5;3:497. [CrossRef]

- Antoniucci DM, Yamashita T, Portale AA. Dietary phosphorus regulates serum fibroblast growth factor-23 concentrations in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Aug;91(8):3144-9. [CrossRef]

- Berndt T, Kumar R. Phosphatonins and the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:341-59. [CrossRef]

- Gaasbeek A, Meinders AE. Hypophosphatemia: an update on its etiology and treatment. Am J Med. 2005 Oct;118(10):1094- 101. [CrossRef]

- Marks J, Debnam ES, Unwin RJ. Phosphate homeostasis and the renal-gastrointestinal axis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010 Aug;299(2):F285-96. [CrossRef]

- King AJ, Siegel M, He Y, Nie B, Wang J, Koo-McCoy S, Minassian NA, Jafri Q, Pan D, Kohler J, et al. Inhibition of sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3 in the gastrointestinal tract by tenapanor reduces paracellular phosphate permeability. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Aug 29;10(456):eaam6474. [CrossRef]

- Walker V. Phosphaturia in kidney stone formers: Still an enigma. Adv Clin Chem. 2019;90:133-96. [CrossRef]

- Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Kronenberg HM. Hormones and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. In Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 14th ed.; Melmed S, Koenig R, Rosen CJ, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; Chapter 29, pp. 1196-1255.

- Curthoys NP, Moe OW. Proximal tubule function and response to acidosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Sep 5;9(9):1627-38. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Xiao K, Paredes JM, Mamonova T, Sneddon WB, Liu H, Wang D, Li S, McGarvey JC, Uehling D, et al. Parathyroid hormone initiates dynamic NHERF1 phosphorylation cycling and conformational changes that regulate NPT2A-dependent phosphate transport. J Biol Chem. 2019 Mar 22;294(12):4546-71. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Gratton E, Forster IC, Hernando N, Wagner CA, Biber J, Sorribas V, Murer H. Mechanisms of phosphate transport. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019 Aug;15(8):482-500. [CrossRef]

- Wagner CA. The basics of phosphate metabolism -Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2023 Sep 2: gfad188. doi: 0.1093/ndt/gfad188.

- Silverman M, Turner RJ (1979). The Renal Proximal Tubule. In: Manson, L.A. (eds) Biomembranes. Biomembranes, vol 10. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Wagner CA, Rubio-Aliaga I, Biber J, Hernando N. Genetic diseases of renal phosphate handling. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014 Sep;29 Suppl 4:iv45-54. [CrossRef]

- Wagner CA, Rubio-Aliaga I, Hernando N. Renal phosphate handling and inherited disorders of phosphate reabsorption: an update. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019 Apr;34(4):549-59. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh Naderi AS, Reilly RF. Hereditary disorders of renal phosphate wasting. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010 Nov;6(11):657-65. [CrossRef]

- Prié D, Friedlander G. Genetic disorders of renal phosphate transport. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 24;362(25):2399-409. [CrossRef]

- Gohil A, Imel EA. FGF23 and Associated Disorders of Phosphate Wasting. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2019 Sep;17(1):17-34. [CrossRef]

- Sayer JA. Progress in Understanding the Genetics of Calcium-Containing Nephrolithiasis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Mar;28(3):748-59. [CrossRef]

- Walker V, Stansbridge EM, Griffin DG. Demography and biochemistry of 2800 patients from a renal stones clinic. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013 Mar;50(Pt 2):127-39. [CrossRef]

- Prié D, Ravery V, Boccon-Gibod L, Friedlander G. Frequency of renal phosphate leak among patients with calcium nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2001 Jul;60(1):272-6. [CrossRef]

- Vilardaga JP, Clark LJ, White AD, Sutkeviciute I, Lee JY, Bahar I. Molecular Mechanisms of PTH/PTHrP Class B GPCR Signaling and Pharmacological Implications. Endocr Rev. 2023 May 8;44(3):474-91. [CrossRef]

- Murer H, Biber J, Forster IC, Werner A. Phosphate transport: from microperfusion to molecular cloning. Pflugers Arch. 2019 Jan;471(1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Wagner CA. Coming out of the PiTs-novel strategies for controlling intestinal phosphate absorption in patients with CKD . Kidney Int 2020; 98 :273–5. [CrossRef]

- Wagner CA. Pharmacology of mammalian Na + -dependent transporters of inorganic phosphate. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2023;. [CrossRef]

- Montanari A, Pirini MG, Lotrecchiano L, Di Prinzio L, Zavatta G. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors with or without Phosphate Metabolism Derangements. Curr Oncol. 2023 Aug 8;30(8):7478-88. [CrossRef]

- Rowe PS, McCarthy EM, Yu AL, Stubbs JR. Correction of vascular calcification and hyperphosphatemia in CKD Rats treated with ASARM peptide. Kidney360. 2022 Aug 30;3(10):1683-98. [CrossRef]

- Goetz R, Nakada Y, Hu MC, Kurosu H, Wang L, Nakatani T, Shi M, Eliseenkova AV, Razzaque MS, Moe OW, et al. Isolated C- terminal tail of FGF23 alleviates hypophosphatemia by inhibiting FGF23-FGFR-Klotho complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 5;107(1):407-12. [CrossRef]

- Doshi SM, Wish JB. Past, present, and future of phosphate management. Kidney Int Rep 2022; 7: 688–98. [CrossRef]

- Verbueken D, Moe OW. Strategies to lower fibroblast growth factor 23 bioactivity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022 Sep 22;37(10):1800-07. [CrossRef]

- Marques JVO, Moreira CA, Borba VZC. New treatments for rare bone diseases: hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Nov 11;66(5):658-65. [CrossRef]

- Zhang MY, Ranch D, Pereira RC, Armbrecht HJ, Portale AA, Perwad F. Chronic inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling improves disordered bone and mineral metabolism in hypophosphatemic (Hyp) mice. Endocrinology. 2012 Apr;153(4):1806-16. [CrossRef]

- Biber J, Hernando N, Forster I, Murer H. Regulation of phosphate transport in proximal tubules. Pflugers Arch. 2009 May;458(1):39-52. [CrossRef]

- Tisher CC, Madsen KM. Anatomy of the kidney. In The Kidney, 4TH ed.; Brenner BM, Rector FC, Jr., Eds.; W.B. Saunders Company, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.: West Philadelphia, United States of America, 1991; Volume 1 Chapter 1, pp. 3-75 (proximal tubule pp. 22-35).

- McDonough AA. Motoring down the microvilli. Focus on "PTH-induced internalization of apical membrane NaPi2a: role of actin and myosin VI". Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009 Dec;297(6):C1331-2. [CrossRef]

- Blaine J, Okamura K, Giral H, Breusegem S, Caldas Y, Millard A, Barry N, Levi M. PTH-induced internalization of apical membrane NaPi2a: role of actin and myosin VI. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009 Dec;297(6):C1339-46. [CrossRef]

- Schuh CD, Polesel M, Platonova E, Haenni D, Gassama A, Tokonami N, Ghazi S, Bugarski M, Devuyst O, Ziegler U, et al. Combined Structural and Functional Imaging of the Kidney Reveals Major Axial Differences in Proximal Tubule Endocytosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Nov;29(11):2696-2712. [CrossRef]

- Maddox DA, Gennari FJ. The early proximal tubule: a high-capacity delivery-responsive reabsorptive site. Am J Physiol. 1987 Apr;252(4 Pt 2):F573-84. [CrossRef]

- DuBose TD Jr, Pucacco LR, Lucci MS, Carter NW. Micropuncture determination of pH, PCO2, and total CO2 concentration in accessible structures of the rat renal cortex. J Clin Invest. 1979 Aug;64(2):476-82. [CrossRef]

- Lee JW, Chou CL, Knepper MA. Deep sequencing in microdissected renal tubules identifies nephron segment-specific transcriptomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 Nov;26(11):2669-77. [CrossRef]

- Hato T, Winfree S, Day R, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA, Yoder MC, Wiggins RC, Zheng Y, Dunn KW, Dagher PC. Two-Photon Intravital Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of the Kidney Reveals Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Signatures. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Aug;28(8):2420-30. [CrossRef]

- Custer M, Lötscher M, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. Expression of Na-P(i) cotransport in rat kidney: localization by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry. Am J Physiol. 1994 May;266(5 Pt 2):F767-74. [CrossRef]

- Virkki LV, Biber J, Murer H, Forster IC. Phosphate transporters: a tale of two solute carrier families. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007 Sep;293(3):F643-54. [CrossRef]

- Forster IC, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H. Phosphate transport kinetics and structure-function relationships of SLC34 and SLC20 proteins. Curr Top Membr. 2012;70:313-56. [CrossRef]

- Biber J, Hernando N, Forster I. Phosphate transporters and their function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:535-50. [CrossRef]

- Lederer E. Renal phosphate transporters. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014 Sep;23(5):502-6. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter TO. Primary Disorders of Phosphate Metabolism. [Updated 2022 Jun 8]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279172/.

- Moser SO, Haykir B, Küng CJ, Bettoni C, Hernando N, Wagner CA. Expression of phosphate and calcium transporters and their regulators in parotid glands of mice. Pflugers Arch. 2023 Feb;475(2):203-16. [CrossRef]

- Villa-Bellosta R, Ravera S, Sorribas V, Stange G, Levi M, Murer H, Biber J, Forster IC. The Na+-Pi cotransporter PiT-2 (SLC20A2) is expressed in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubules and regulated by dietary Pi. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009 Apr;296(4):F691-9. [CrossRef]

- Magagnin S, Werner A, Markovich D, Sorribas V, Stange G, Biber J, Murer H. Expression cloning of human and rat renal cortex Na/Pi cotransport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Jul 1;90(13):5979-83. [CrossRef]

- Forster IC. The molecular mechanism of SLC34 proteins: insights from two decades of transport assays and structure-function studies. Pflugers Arch. 2019 Jan;471(1):15-42. [CrossRef]

- Fenollar-Ferrer C, Patti M, Knöpfel T, Werner A, Forster IC, Forrest LR. Structural fold and binding sites of the human Na⁺- phosphate cotransporter NaPi-II. Biophys J. 2014 Mar 18;106(6):1268-79. [CrossRef]

- de La Horra C, Hernando N, Forster I, Biber J, Murer H. Amino acids involved in sodium interaction of murine type II Na(+)-P(i) cotransporters expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2001 Mar 1;531(Pt 2):383-91. [CrossRef]

- Murer H. Functional domains in the renal type IIa Na/P(i)-cotransporter. Kidney Int. 2002 Aug;62(2):375-82. [CrossRef]

- Shenolikar S, Voltz JW, Cunningham R, Weinman EJ. Regulation of ion transport by the NHERF family of PDZ proteins. Physiology (Bethesda). 2004 Dec;19:362-9. [CrossRef]

- Forster I, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H. The voltage dependence of a cloned mammalian renal type II Na+/Pi cotransporter (NaPi-2). J Gen Physiol. 1998 Jul;112(1):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Busch A, Waldegger S, Herzer T, Biber J, Markovich D, Hayes G, Murer H, Lang F. Electrophysiological analysis of Na+/Pi cotransport mediated by a transporter cloned from rat kidney and expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Aug 16;91(17):8205-8. [CrossRef]

- Werner A, Patti M, Hany S Zinad HS, Fearn A, Laude A, Forster I. Molecular determinants of transport function in zebrafish Slc34a Na-phosphate transporters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016 Dec;311(6):R1213-22. [CrossRef]

- Patti M, Fenollar-Ferrer C, Werner A, Forrest LR, Forster IC. Cation interactions and membrane potential induce conformational changes in NaPi-IIb. Biophys J. 2016 Sep 6;111(5):973-88. [CrossRef]

- Inoue M, Digman MA, Cheng M, Breusegem SY, Halaihel N, Sorribas V, Mantulin WW, Gratton E, Barry NP, Levi M. Partitioning of NaPi cotransporter in cholesterol-, sphingomyelin-, and glycosphingolipid-enriched membrane domains modulates NaPi protein diffusion, clustering, and activity. J Biol Chem. 2004 Nov 19;279(47):49160-71. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Baird BM, Wilson PV. Cholesterol modulates rat renal brush border membrane phosphate transport. J Clin Invest. 1990 Jan;85(1):231-7. [CrossRef]

- Alcalde AI, Sarasa M, Raldúa D, Aramayona J, Morales R, Biber J, Murer H, Levi M, Sorribas V. Role of thyroid hormone in regulation of renal phosphate transport in young and aged rats. Endocrinology. 1999 Apr;140(4):1544-51. [CrossRef]

- Sorribas V, Lötscher M, Loffing J, Biber J, Kaissling B, Murer H, Levi M. Cellular mechanisms of the age-related decrease in renal phosphate reabsorption. Kidney Int. 1996 Sep;50(3):855-63. [CrossRef]

- Breusegem SY, Takahashi H, Giral-Arnal H, Wang X, Jiang T, Verlander JW, Wilson P, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Sutherland E, Caldas Y, eta al. Differential regulation of the renal sodium-phosphate cotransporters NaPi-IIa, NaPi-IIc, and PiT-2 in dietary potassium deficiency. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009 Aug;297(2):F350-61. [CrossRef]

- Zajicek HK, Wang H, Puttaparthi K, Halaihel N, Markovich D, Shayman J, Béliveau R, Wilson P, Rogers T, Levi M. Glycosphingolipids modulate renal phosphate transport in potassium deficiency. Kidney Int. 2001 Aug;60(2):694-704. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Shenolikar S, Blanpied TA. Dynamics of PTH-induced disassembly of Npt2a/NHERF-1 complexes in living OK cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011 Jan;300(1):F231-5. [CrossRef]

- Segawa H, Kaneko I, Takahashi A, Kuwahata M, Ito M, Ohkido I, Tatsumi S, Miyamoto K (2002) Growth-related renal type II Na/Pi cotransporter. J Biol Chem 277:19665–72 . [CrossRef]

- Ohkido I, Segawa, Hiroko & Yanagida, R & Nakamura, M & Miyamoto, K. (2003). Cloning, gene structure and dietary regulation of the type-IIc Na/Pi cotransporter in the mouse kidney. Pflügers Archiv: European journal of physiology. 446. 106-15. 10.1007/s00424-003-1010-6.

- Beck L, Karaplis AC, Amizuka N, Hewson AS, Ozawa H, Tenenhouse HS. Targeted inactivation of Npt2 in mice leads to severe renal phosphate wasting, hypercalciuria, and skeletal abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Apr 28;95(9):5372-7. [CrossRef]

- Segawa H, Onitsuka A, Furutani J, Kaneko I, Aranami F, Matsumoto N, Tomoe Y, Kuwahata M, Ito M, Matsumoto M, Li M, Amizuka N, Miyamoto K. Npt2a and Npt2c in mice play distinct and synergistic roles in inorganic phosphate metabolism and skeletal development. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009 Sep;297(3):F671-8. [CrossRef]

- Jaureguiberry G, Carpenter TO, Forman S, Jüppner H, Bergwitz C. A novel missense mutation in SLC34A3 that causes hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria in humans identifies threonine 137 as an important determinant of sodium-phosphate cotransport in NaPi-IIc. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008 Aug;295(2):F371-9. doi: 0.1152/ajprenal.00090.2008.

- Gordon RJ, Li D, Doyle D, Zaritsky J, Levine MA. Digenic heterozygous mutations in SLC34A3 and SLC34A1 cause dominant hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Jul 1;105(7):2392–400. [CrossRef]

- Forster IC, Hernando N, Biber J, Murer H Phosphate transporters of the SLC20 and SLC34 families. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2013; 34(2-3): 386-95. [CrossRef]

- Nowik M, Picard N, Stange G, Capuano P, Tenenhouse HS, Biber J, Murer H, Wagner CA. Renal phosphaturia during metabolic acidosis revisited: molecular mechanisms for decreased renal phosphate reabsorption Pflugers Arch. 2008 Nov;457(2):539-49. [CrossRef]

- Giral H, Lanzano L, Caldas Y, Blaine J, Verlander JW, Lei T, Gratton E, Levi M. Role of PDZ domain containing 1 (PDZK1) in apical membrane expression of renal Na-coupled phosphate (Na/Pi) transporters. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 15032–42. [CrossRef]

- Segawa H, Kaneko I, Shiozaki Y, Ito M, Tatsumi S, Miyamoto K-i. Molecular control of growth-related sodium-phosphate co- transporter (SLC34A3). Current Molecular Biology Reports 2019; 5: 26-33. 10.1007/s40610-019-0112-7.

- Segawa H, Yamanaka S, Ito M, Kuwahata M, Shono M, Yamamoto T, Miyamoto K. Internalization of renal type IIc Na-Pi cotransporter in response to a high-phosphate diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005 Mar;288(3):F587-96. [CrossRef]

- Hori M, Shimizu Y, Fukumoto S. Minireview: fibroblast growth factor 23 in phosphate homeostasis and bone metabolism. Endocrinology. 2011 Jan;152(1):4-10. [CrossRef]

- Tomoe Y, Segawa H, Shiozawa K, Kaneko I, Tominaga R, Hanabusa E, Aranami F, Furutani J, Kuwahara S, Tatsumi S, et al. Phosphaturic action of fibroblast growth factor 23 in Npt2 null mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010 Jun;298(6):F1341-50. [CrossRef]

- Fujii T, Shiozaki Y, Segawa H, Nishiguchi S, Hanazaki A, Noguchi M, Kirino R, Sasaki S, Tanifuji K, Koike M,et al. Analysis of opossum kidney NaPi-IIc sodium-dependent phosphate transporter to understand Pi handling in human kidney. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2019 Mar;23(3):313-24. [CrossRef]

- Bergwitz C, Miyamoto KI. Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapy. Pflugers Arch. 2019 Jan;471(1):149-63. [CrossRef]

- Picard N, Capuano P, Stange G, Mihailova M, Kaissling B, Murer H, Biber J, Wagner CA. Acute parathyroid hormone differentially regulates renal brush border membrane phosphate cotransporters. Pflugers Arch. 2010 Aug;460(3):677-87. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Shenolikar S. CAMP-mediated inhibition of the renal brush border membrane Na+-H+ exchanger requires a dissociable phosphoprotein cofactor. J Clin Invest. 1993 Oct;92(4):1781-6. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Shenolikar S. The Na-H exchanger regulatory factor. Exp Nephrol 1997 5(6):449-52. PMID: 9438172.

- Reczek D, Berryman M, Bretscher A. Identification of EBP50: A PDZ-containing phosphoprotein that associates with members of the ezrin-radixin-moesin family. J Cell Biol. 1997 Oct 6;139(1):169-79. [CrossRef]

- Ardura JA, Friedman PA. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor function by Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factors. Pharmacol Rev. 2011 Dec;63(4):882-900. [CrossRef]

- Hernando N, Gisler SM, Pribanic S, Déliot N, Capuano P, Wagner CA, Moe OW, Biber J, Murer H. NaPi-IIa and interacting partners. J Physiol. 2005 Aug 15;567(Pt 1):21-6. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya S, Stanley CB, Heller WT, Friedman PA, Bu Z. Dynamic structure of the full-length scaffolding protein NHERF1 influences signaling complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2019 Jul 19;294(29):11297-310. [CrossRef]

- Hernando N, Wagner CA, Gisler SM, Biber J, Murer H. Hernando N, Wagner CA, Gisler SM, Biber J, Murer H. PDZ proteins and proximal ion transport. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004 Sep;13(5):569-74. [CrossRef]

- He J, Bellini M, Inuzuka H, Xu J, Xiong Y, Yang X, Castleberry AM, Hall RA. Proteomic analysis of beta1-adrenergic receptor interactions with PDZ scaffold proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006 Feb 3;281(5):2820-7. [CrossRef]

- Hall RA, Premont RT, Chow CW, Blitzer JT, Pitcher JA, Claing A, Stoffel RH, Barak LS, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ, et al. The beta2-adrenergic receptor interacts with the Na+/H+-exchanger regulatory factor to control Na+/H+ exchange. Nature. 1998 Apr 9;392(6676):626-30. [CrossRef]

- Mamonova T, Friedman PA. Noncanonical Sequences Involving NHERF1 Interaction with NPT2A Govern Hormone-Regulated Phosphate Transport: Binding Outside the Box. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jan 22;22(3):1087. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Lederer ED. NHERF-1 and the regulation of renal phosphate reabsoption: a tale of three hormones. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012 Aug 1;303(3):F321-7. [CrossRef]

- Vistrup-Parry M, Sneddon WB, Bach S, Strømgaard K, Friedman PA, Mamonova T. Multisite NHERF1 phosphorylation controls GRK6A regulation of hormone-sensitive phosphate transport. J Biol Chem. 2021 Jan-Jun;296:100473. [CrossRef]

- Karim Z, Gérard B, Bakouh N, Alili R, Leroy C, Beck L, Silve C, Planelles G, Urena-Torres P, Grandchamp B, et al. NHERF1 mutations and responsiveness of renal parathyroid hormone. N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 11;359(11):1128-35. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Callaway DJ, Bu Z. Ezrin induces long-range interdomain allostery in the scaffolding protein NHERF1. J Mol Biol. 2009 Sep 11;392(1):166-80. [CrossRef]

- Farago B, Li J, Cornilescu G, Callaway DJ, Bu Z. Activation of nanoscale allosteric protein domain motion revealed by neutron spin echo spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2010 Nov 17;99(10):3473-82. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Zhang Y, Biswas R, Bloch RJ, Shenolikar S. Cooperativity between the phosphorylation of Thr95 and Ser77 of NHERF-1 in the hormonal regulation of renal phosphate transport. J Biol Chem. 2010 Aug 13;285(33):25134-8. [CrossRef]

- Martin A, David V, Quarles LD. Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol Rev. 2012 Jan;92(1):131-55. [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, Thompson JR. The regulation of parathyroid hormone secretion and synthesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 Feb;22(2):216-24. [CrossRef]

- Naveh-Many T, A Sela-Brown, J Silver, Protein-RNA interactions in the regulation of PTH gene expression by calcium and phosphate. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1999; 14 : 811–13. [CrossRef]

- Almaden Y, Canalejo A, Hernandez A, Ballesteros E, Garcia-Navarro S, Torres A, Rodriguez M. Direct effect of phosphorus on PTH secretion from whole rat parathyroid glands in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1996 Jul;11(7):970-6. [CrossRef]

- Taketani Y, Segawa H, Chikamori M, Morita K, Tanaka K, Kido S, Yamamoto H, Iemori Y, Tatsumi S, Tsugawa N, et al. Regulation of type II renal Na+-dependent inorganic phosphate transporters by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Identification of a vitamin D-responsive element in the human NAPi-3 gene. J Biol Chem. 1998 Jun 5;273(23):14575-81. [CrossRef]

- Silver J, Naveh-Many T. FGF23 and the parathyroid. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;728:92-9. [CrossRef]

- Naveh-Many T, Silver J. The Pas de Trois of Vitamin D, FGF23, and PTH. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Feb;28(2):393-5. [CrossRef]

- Chanakul A, Zhang MY, Louw A, Armbrecht HJ, Miller WL, Portale AA, Perwad F. FGF-23 regulates CYP27B1 transcription in the kidney and in extra-renal tissues. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 3;8(9):e72816. [CrossRef]

- Maeda S, Sutliff RL, Qian J, Lorenz JN, Wang J, Tang H, Nakayama T, Weber C, Witte D, Strauch AR, et al. Targeted overexpression of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) to vascular smooth muscle in transgenic mice lowers blood pressure and alters vascular contractility. Endocrinology. 1999 Apr;140(4):1815-25. [CrossRef]

- Strewler GJ. The physiology of parathyroid hormone-related protein. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 20;342(3):177-85. [CrossRef]

- Pioszak AA, Parker NR, Gardella TJ, Xu HE. Structural basis for parathyroid hormone-related protein binding to the.

- parathyroid hormone receptor and design of conformation-selective peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009 Oct 9;284(41):28382-91. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenmann J, Schöppe J, Klenk C, Plückthun A. New views into class B GPCRs from the crystal structure of PTH1R. FEBS J. 2019 Dec;286(24):4852-60. [CrossRef]

- Zhai X, Mao C, Shen Q, Zang S, Shen DD, Zhang H, Chen Z, Wang G, Zhang C, Zhang Y,et al. Molecular insights into the distinct signaling duration for the peptide-induced PTH1R activation. Nat Commun. 2022 Oct 21;13(1):6276. [CrossRef]

- Alexander RT, Dimke H. Effects of parathyroid hormone on renal tubular calcium and phosphate handling. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2023 May;238(1):e13959. doi: 10.1111/apha.13959.Traebert M, Völkl H, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. Luminal and contraluminal action of 1-34 and 3-34 PTH peptides on renal type IIa Na-P(i) cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000 May;278(5):F792-8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F792.

- Weinman EJ, Lederer ED. PTH-mediated inhibition of the renal transport of phosphate. Exp Cell Res. 2012 May 15;318(9):1027-32. [CrossRef]

- Klenk C, Hommers L, Lohse MJ. Proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular domain affects signaling of parathyroid hormone 1 receptor. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Feb 22;13:839351. [CrossRef]

- Cary BP, Zhang X, Cao J, Johnson RM, Piper SJ, Gerrard EJ, Wootten D, Sexton PM. New Insights into the Structure and Function of Class B1 GPCRs. Endocr Rev. 2023 May 8;44(3):492-517. [CrossRef]

- Lee SM, Jeong Y, Simms J, Warner ML, Poyner DR, Chung KY, Pioszak AA. Calcitonin Receptor N-Glycosylation Enhances Peptide Hormone Affinity by Controlling Receptor Dynamics. J Mol Biol. 2020 Mar 27;432(7):1996-2014. [CrossRef]

- Bisello A, Greenberg Z, Behar V, Rosenblatt M, Suva LJ, Chorev M. Role of glycosylation in expression and function of the human parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor. Biochemistry. 1996 Dec 10;35(49):15890-5. [CrossRef]

- Harmar AJ. Family-B G-protein-coupled receptors. Genome Biol. 2001;2(12):REVIEWS3013. [CrossRef]

- Gardella TJ, Luck MD, Fan MH, Lee C. Transmembrane residues of the parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor that specifically affect binding and signaling by agonist ligands. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(22):12820–25. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh SP, Vilardarga JP, Baranski TJ, Lichtarge O, Iiri T, Meng EC, Nissenson RA, Bourne HR. Similar structures and shared switch mechanisms of the beta2-adrenoceptor and the parathyroid hormone receptor. Zn(II) bridges between helices III and VI block activation. J Biol Chem. 1999 Jun 11;274(24):17033-41. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Leiro R, Scheres SH. Unravelling biological macromolecules with cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 2016 Sep 15;537(7620):339-46. [CrossRef]

- Nemec K, Schihada H, Kleinau G, Zabel U, Grushevskyi EO, Scheerer P, Lohse MJ, Maiellaro I. Functional modulation of PTH1R activation and signaling by RAMP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Aug 9;119(32):e2122037119. [CrossRef]

- Vilardaga JP, Bünemann M, Krasel C, Castro M, Lohse MJ. Measurement of the millisecond activation switch of G protein- coupled receptors in living cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2003 Jul;21(7):807-12. [CrossRef]

- Castro M, Nikolaev VO, Palm D, Lohse MJ, Vilardaga JP. Turn-on switch in parathyroid hormone receptor by a two-step parathyroid hormone binding mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Nov 1;102(44):16084-9. [CrossRef]

- Syme CA, Friedman PA, Bisello A. Parathyroid hormone receptor trafficking contributes to the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases but is not required for regulation of cAMP signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005 Mar 25;280(12):11281-8. [CrossRef]

- Gesty-Palmer D, Chen M, Reiter E, Ahn S, Nelson CD, Wang S, Eckhardt AE, Cowan CL, Spurney RF, Luttrell LM, et al. Distinct beta-arrestin- and G protein-dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor-stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006 Apr 21;281(16):10856-64. [CrossRef]

- Vilardaga JP, Romero G, Feinstein TN, Wehbi VL. Kinetics and dynamics in the G protein-coupled receptor signaling cascade. Methods Enzymol. 2013; 522, 337–63. [CrossRef]

- Wootten D, Miller LJ, Koole C, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM. Allostery and Biased Agonism at Class B G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Chem Rev. 2017 Jan 11;117(1):111-38. [CrossRef]

- Yuan L, Barbash S, Kongsamut S, Eishingdrelo A, Sakmar TP, Eishingdrelo H. 14-3-3 signal adaptor and scaffold proteins mediate GPCR trafficking. Sci Rep. 2019 Aug 1;9(1):11156. [CrossRef]

- Dicker F, Quitterer U, Winstel R, Honold K, Lohse MJ. Phosphorylation-independent inhibition of parathyroid hormone receptor signaling by G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 May 11;96(10):5476-81. [CrossRef]

- Ferrandon S, Feinstein TN, Castro M, Wang B, Bouley R, Potts JT, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP. Sustained cyclic AMP production by parathyroid hormone receptor endocytosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2009 Oct;5(10):734-42. [CrossRef]

- Maeda A, Okazaki M, Baron DM, Dean T, Khatri A, Mahon M, Segawa H, Abou-Samra AB, Jüppner H, Bloch KD, et al. Critical role of parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor-1 phosphorylation in regulating acute responses to PTH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Apr 9;110(15):5864-9. [CrossRef]

- Cheloha RW, Gellman SH, Vilardaga JP, Gardella TJ. PTH receptor-1 signalling-mechanistic insights and therapeutic prospects. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015 Dec;11(12):712-24. [CrossRef]

- Swinney DC. Biochemical mechanisms of drug action: what does it take for success? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004 Sep;3(9):801-8. [CrossRef]

- Lee M, Partridge NC. Parathyroid hormone signaling in bone and kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009 Jul;18(4):298- 302. [CrossRef]

- Copeland RA, Pompliano DL, Meek TD. Drug-target residence time and its implications for lead optimization. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006 Sep;5(9):730-9. [CrossRef]

- Tawfeek HA, Abou-Samra AB. Negative regulation of parathyroid hormone (PTH)-activated phospholipase C by PTH/PTH- related peptide receptor phosphorylation and protein kinase A. Endocrinology. 2008 Aug;149(8):4016-23. [CrossRef]

- Wehbi VL, Stevenson HP, Feinstein TN, Calero G, Romero G, Vilardaga JP. Noncanonical GPCR signaling arising from a PTH receptor-arrestin-Gβγ complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jan 22;110(4):1530-5. [CrossRef]

- Feinstein TN, Wehbi VL, Ardura JA, Wheeler DS, Ferrandon S, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP. Retromer terminates the generation of cAMP by internalized PTH receptors. Nat Chem Biol. 2011 May;7(5):278-84. [CrossRef]

- Jean-Alphonse FG, Wehbi VL, Chen J, Noda M, Taboas JM, Xiao K, Vilardaga JP. β2-adrenergic receptor control of endosomal PTH receptor signaling via Gβγ. Nat Chem Biol. 2017 Mar;13(3):259-61. [CrossRef]

- White AD, Jean-Alphonse FG, Fang F, Peña KA, Liu S, König GM, Inoue A, Aslanoglou D, Gellman SH, Kostenis E, Xiao K, Vilardaga JP. Gq/11-dependent regulation of endosomal cAMP generation by parathyroid hormone class B GPCR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7455-60. [CrossRef]

- Gidon A, Al-Bataineh MM, Jean-Alphonse FG, Stevenson HP, Watanabe T, Louet C, Khatri A, Calero G, Pastor-Soler NM, Gardella TJ, et al. Endosomal GPCR signaling turned off by negative feedback actions of PKA and v-ATPase. Nat Chem Biol. 2014 Sep;10(9):707-9. [CrossRef]

- Noda H, Okazaki M, Joyashiki E, Tamura T, Kawabe Y, Khatri A, Jueppner H, Potts JT Jr, Gardella TJ, Shimizu M. Optimization of PTH/PTHrP Hybrid Peptides to Derive a Long-Acting PTH Analog (LA-PTH). JBMR Plus. 2020 May 30;4(7):e10367. [CrossRef]

- Cheng X, Ji Z, Tsalkova T, Mei F. Epac and PKA: a tale of two intracellular cAMP receptors. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2008 Jul;40(7):651-62. [CrossRef]

- Bouvet M, Blondeau J-P, Lezoualc’h F. The Epac1 protein: pharmacological modulators, cardiac signalosome and pathophysiology. Cells 2019, 8: 1543. [CrossRef]

- de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide- exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998 Dec 3;396(6710):474-7. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki H, Springett GM, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, Housman DE, Graybiel AM. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate Rap1. Science. 1998 Dec 18;282(5397):2275-9. [CrossRef]

- Tomilin VN, Pochynyuk O. A peek into Epac physiology in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2019 327; F1094-97. [CrossRef]

- Honegger KJ, Capuano P, Winter C, Bacic D, Stange G, Wagner CA, Biber J, Murer H, Hernando N. Regulation of sodium- proton exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) by PKA and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Jan 17;103(3):803-8. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Konings IB, Zhao J, Price LS, de Heer E, Deen PM. Renal expression of exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) 1 and 2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F525–33, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Lee K. Epac: new emerging cAMP-binding protein. BMB Rep. 2021 Mar;54(3):149-56. [CrossRef]

- de Rooij J, Rehmann H, van Triest M, Cool RH, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Mechanism of regulation of the Epac family of cAMP- dependent RapGEFs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20829–36. [CrossRef]

- Frische EW, Zwartkruis FJ. Rap1, a mercenary among the Ras-like GTPases. Dev Biol. 2010; 340: 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Cherezova A, Tomilin V, Buncha V, Zaika O, Ortiz PA, Mei F, Cheng X, Mamenko M, Pochynyuk O. Urinary concentrating defect in mice lacking Epac1 or Epac2. FASEB J 33: 2156–70, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Friedman PA, Sneddon WB, Mamonova T, Montanez-Miranda C, Ramineni S, Harbin NH, Squires KE, Gefter JV, Magyar CE, Emlet DR, et al. RGS14 regulates PTH- and FGF23-sensitive NPT2A-mediated renal phosphate uptake via binding to the NHERF1 scaffolding protein. J Biol Chem. 2022 May;298(5):101836. [CrossRef]

- Turan S, Bastepe M. The GNAS complex locus and human diseases associated with loss-of-function mutations or epimutations within this imprinted gene. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;80(4):229-41. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Davaatseren M, Lee S. Rare PTH Gene Mutations Causing Parathyroid Disorders: A Review. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2020 Mar;35(1):64-70. [CrossRef]

- Lemos MC, Thakker RV. GNAS mutations in Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1a and related disorders. Hum Mutat. 2015 Jan;36(1):11-9. [CrossRef]

- Yu S, Yu D, Lee E, Eckhaus M, Lee R, Corria Z, Accili D, Westphal H, Weinstein LS. Variable and tissue-specific hormone resistance in heterotrimeric Gs protein alpha-subunit (Gsalpha) knockout mice is due to tissue-specific imprinting of the gsalpha gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Jul 21;95(15):8715-20. [CrossRef]

- Bastepe M, Raas-Rothschild A, Silver J, Weissman I, Wientroub S, Jüppner H, Gillis D. A form of Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia with limited metabolic and skeletal abnormalities is caused by a novel activating parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jul;89(7):3595-600. [CrossRef]

- Schipani E, Kruse K, Jüppner H. A constitutively active mutant PTH-PTHrP receptor in Jansen-type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. Science. 1995 Apr 7;268(5207):98-100. [CrossRef]

- Savoldi G, Izzi C, Signorelli M, Bondioni MP, Romani C, Lanzi G, Moratto D, Verdoni L, Pinotti M, Prefumo F, et al. Prenatal presentation and postnatal evolution of a patient with Jansen metaphyseal dysplasia with a novel missense mutation in PTH1R. Am J Med Genet A. 2013 Oct;161A(10):2614-9. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson DB, Thakker RV. A donor splice site mutation in the parathyroid hormone gene is associated with autosomal recessive hypoparathyroidism. Nat Genet. 1992 May;1(2):149-52. [CrossRef]

- Chase LR, Melson GL, Aurbach GD. Pseudohypoparathyroidism: defective excretion of 3’,5’-AMP in response to parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1969 Oct;48(10):1832-44. [CrossRef]

- Albright F, Burnett CH, Smith PH, Parson W. Pseudohypoparathyroidism – An example of ‘Seabright-Bantam syndrome’ Endocrinology. 1942; 30: 922–32.

- Ines Armando, Van Anthony M. Villar, and Pedro A. Jose. Dopamine and Renal Function and Blood Pressure Regulation Comp Physiol. 2011 July; 1(3): 1075–117. [CrossRef]

- Jose PA, Soares-da-Silva P, Eisner GM, Felder RA. Dopamine and G protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 in the kidney: role in blood pressure regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Dec;1802(12):1259-67. [CrossRef]

- Harris RC, Zhang MZ. Dopamine, the kidney, and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012 Apr;14(2):138-43. [CrossRef]

- Adam WR, Adams BA. Production and excretion of dopamine by the isolated perfused rat kidney. Ren Physiol. 1985;8(3):150-8. [CrossRef]

- Baines AD. Effects of salt intake and renal denervation on catecholamine catabolism and excretion. Kidney Int. 1982 Feb;21(2):316-22. [CrossRef]

- Berndt TJ, Khraibi AA, Thothathri V, Dousa TP, Tyce GM, Knox FG. Effect of increased dietary phosphate intake on dopamine excretion in the presence and absence of the renal nerves. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1994; 20(3): 158-62.

- Stephenson RK, Sole MJ, Baines AD. Neural and extraneural catecholamine production by rat kidneys. Am J Physiol 1982; 242: F261–6. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZQ, Siragy HM, Felder RA, Carey RM. Intrarenal dopamine production and distribution in the rat. Physiological control of sodium excretion. Hypertension 1997 ;29(1 Pt 2):228-34. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki H, Nakane H, Kawamura M, Yoshizawa M, Takeshita E, Saruta T. Excretion and metabolism of dopa and dopamine by isolated perfused rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1984; 247(3 Pt 1): E285-90. [CrossRef]

- Wolfovitz E, Grossman E, Folio CJ, Keiser HR, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Derivation of urinary dopamine from plasma dihydroxyphenylalanine in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 1993; 84(5): 549-57. [CrossRef]

- Zimlichman R, Levinson PD, Kelly G, Stull R, Keiser HR, Goldstein DS. Derivation of urinary dopamine from plasma dopa. Clin Sci (Lond). 1988 Nov;75(5):515-20. [CrossRef]

- Eldrup E, Hetland ML, Christensen NJ. Increase in plasma 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) appearance rate after inhibition of DOPA decarboxylase in humans. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994 Mar;24(3):205-11. [CrossRef]

- Grossman E, Hoffman A, Armando I, Abassi Z, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Sympathoadrenal contribution to plasma dopa (3,4- dihydroxyphenylalanine) in rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992; 83: 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Soares-Da-Silva P, Serrão MP, Vieira-Coelho MA. Apical and basolateral uptake and intracellular fate of dopamine precursor L-dopa in LLC-PK1 cells. Am J Physiol 1998; 274(2): F243-51. [CrossRef]

- Gomes P, Soares-da-Silva P. Na+-independent transporters, LAT-2 and b0,+, exchange L-DOPA with neutral and basic amino acids in two clonal renal cell lines. J Membr Biol 2002; 186(2): 63-80. [CrossRef]

- de Toledo FG, Beers KW, Berndt TJ, Thompson MA, Tyce GM, Knox FG, Dousa TP. Opposite paracrine effects of 5-HT and dopamine on Na(+)-Pi cotransport in opossum kidney cells. Kidney Int. 1997 Jul;52(1):152-6. [CrossRef]

- Wassenberg T, Monnens LA, Geurtz BP, Wevers RA, Verbeek MM, Willemsen MA. The paradox of hyperdopaminuria in aromatic L-amino Acid deficiency explained. JIMD Rep. 2012;4:39-45. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes MH, Pestana M, Soares-da-Silva P. Deamination of newly-formed dopamine in rat renal tissues. Br J Pharmacol. 1991 Mar;102(3):778-82. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães JT, Soares-da-Silva P. The activity of MAO A and B in rat renal cells and tubules. Life Sci. 1998;62(8):727-37. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Li G, Wang P, Velazquez H, Yao X, Li Y, Wu Y, Peixoto A, Crowley S, Desir GV. Renalase is a novel, soluble monoamine oxidase that regulates cardiac function and blood pressure. J Clin Invest. 2005 May;115(5):1275-80. [CrossRef]

- Isaac J, Berndt TJ, Chinnow SL, Tyce GM, Dousa TP, Knox FG. Dopamine enhances the phosphaturic response to parathyroid hormone in phosphate-deprived rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992 Mar;2(9):1423-9. [CrossRef]

- Berndt TJ, MacDonald A, Walikonis R, Chinnow S, Dousa TP, Tyce GM, Knox FG. Excretion of catecholamines and metabolites in response to increased dietary phosphate intake. J Lab Clin Med. 1993 Jul;122(1):80-4.

- Weinman EJ, Biswas R, Steplock D, Wang P, Lau YS, Desir GV, Shenolikar S. Increased renal dopamine and acute renal adaptation to a high-phosphate diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011 May;300(5):F1123-9. [CrossRef]

- Sizova D, Velazquez H, Sampaio-Maia B, Quelhas-Santos J, Pestana M, Desir GV. Renalase regulates renal dopamine and phosphate metabolism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013 Sep 15;305(6):F839-44. [CrossRef]

- Quelhas-Santos J, Serrão MP, Soares-Silva I, Fernandes-Cerqueira C, Simões-Silva L, Pinho MJ, Remião F, Sampaio-Maia B, Desir GV, Pestana M. Renalase regulates peripheral and central dopaminergic activities. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015 Jan 15;308(2):F84-91. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell DP, Botkin SJ, Ramos SI, Sibley DR, Ariano MA, Felder RA, Carey RM. Localization of dopamine D1A receptor protein in rat kidneys. Am J Physiol. 1995 Jun;268(6 Pt 2):F1185-97. [CrossRef]

- Felder CC, McKelvey AM, Gitler MS, Eisner GM, Jose PA. Dopamine receptor subtypes in renal brush border and basolateral membranes. Kidney Int. 1989 Aug;36(2):183-93. [CrossRef]

- Jackson A, Iwasiow RM, Chaar ZY, Nantel MF, Tiberi M. Homologous regulation of the heptahelical D1A receptor responsiveness: specific cytoplasmic tail regions mediate dopamine-induced phosphorylation, desensitization and endocytosis. J Neurochem. 2002 Aug;82(3):683-97. [CrossRef]

- Kim OJ, Gardner BR, Williams DB, Marinec PS, Cabrera DM, Peters JD, Mak CC, Kim KM, Sibley DR. The role of phosphorylation in D1 dopamine receptor desensitization: Evidence for a novel mechanism of arrestin association. J Biol Chem 279: 7999–8010, 2004. 10.1074/jbc.M308281200.

- Tsao P, Cao T, von Zastrow M. Role of endocytosis in mediating downregulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Feb;22(2):91-6. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Biswas R, Steplock D, Douglass TS, Cunningham R, Shenolikar S. Sodium-hydrogen exchanger regulatory factor 1 (NHERF-1)transduces signals that mediate dopamine inhibition of sodium-phosphate co-transport in mouse kidney. J Biol Chem2010; 285: 13454–60. [CrossRef]

- Jose PA, Eisner GM, Felder RA. Renal dopamine and sodium homeostasis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2000 Apr;2(2):174-83. [CrossRef]

- Holmes A, Lachowicz JE, Sibley DR. Phenotypic analysis of dopamine receptor knockout mice; recent insights into the functional specificity of dopamine receptor subtypes. Neuropharmacology. 2004 Dec;47(8):1117-34. [CrossRef]

- Shultz PJ, Sedor JR, Abboud HE. Dopaminergic stimulation of cAMP accumulation in cultured rat mesangial cells. Am J Physiol. 1987 Aug;253(2 Pt 2):H358-64. [CrossRef]

- Kimura K, White BH, Sidhu A. Coupling of human D-1 dopamine receptors to different guanine nucleotide binding proteins. Evidence that D-1 dopamine receptors can couple to both Gs and G(o). J Biol Chem. 1995 Jun 16;270(24):14672-8. [CrossRef]

- Felder CC, Jose PA, Axelrod J. The dopamine-1 agonist, SKF 82526, stimulates phospholipase-C activity independent of adenylate cyclase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989 Jan;248(1):171-5.

- Jin LQ, Wang HY, Friedman E. Stimulated D(1) dopamine receptors couple to multiple Galpha proteins in different brain regions. J Neurochem. 2001 Sep;78(5):981-90. [CrossRef]

- Vyas SJ, Eichberg J, Lokhandwala MF. Characterization of receptors involved in dopamine-induced activation of phospholipase-C in rat renal cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992 Jan;260(1):134-9.

- Armando I, Villar VA, Jose PA. Dopamine and renal function and blood pressure regulation. Compr Physiol. 2011 Jul;1(3):1075-117. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, Takeda S, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 May 22;98(11):6500-5. [CrossRef]

- White KE, Larsson TE, Econs MJ. The roles of specific genes implicated as circulating factors involved in normal and disordered phosphate homeostasis: frizzled related protein-4, matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein, and fibroblast growth factor 23. Endocr Rev. 2006 May;27(3):221-41. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Muto T, Urakawa I, Yoneya T, Yamazaki Y, Okawa K, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Mutant FGF-23 responsible for autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is resistant to proteolytic cleavage and causes hypophosphatemia in vivo. Endocrinology. 2002 Aug;143(8):3179-82. [CrossRef]

- Agoro R, Ni P, Noonan ML, White KE. Osteocytic FGF23 and Its Kidney Function. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020 Aug 28;11:592. [CrossRef]

- Thomas SM, Li Q, Faul C. Fibroblast growth factor 23, klotho and heparin. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2023 Jul 1;32(4):313-23. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Nakahara K, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Mar;19(3):429-35. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Tomizuka K, Yamashita T. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004 Feb;113(4):561-8. [CrossRef]

- Sitara D, Razzaque MS, Hesse M, Yoganathan S, Taguchi T, Erben RG, Jüppner H, Lanske B. Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypophosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol. 2004 Nov;23(7):421-32. [CrossRef]

- Holbrook L, Brady R. McCune-Albright Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan- [Updated 2023 Jul 10].Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537092/.

- Leet AI, Collins MT. Current approach to fibrous dysplasia of bone and McCune-Albright syndrome. J Child Orthop. 2007 Mar;1(1):3-17. [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita Y, Hori M, Taguchi M, Fukumoto S. Functional analysis of mutant FAM20C in Raine syndrome with FGF23-related hypophosphatemia. Bone. 2014 Oct;67:145-51. [CrossRef]

- Palma-Lara I, Pérez-Ramírez M, García Alonso-Themann P, Espinosa-García AM, Godinez-Aguilar R, Bonilla-Delgado J, López- Ornelas A, Victoria-Acosta G, Olguín-García MG, Moreno J, et al. FAM20C Overview: classic and novel targets, pathogenic variants and Raine Syndrome phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 27;22(15):8039. [CrossRef]

- Saito H, Maeda A, Ohtomo S, Hirata M, Kusano K, Kato S, Ogata E, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Fukushima N. Circulating FGF-23 is regulated by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phosphorus in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jan 28;280(4):2543-9. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Sabbagh Y, Davis SI, Demay MB, White KE. Genetic dissection of phosphate- and vitamin D-mediated regulation of circulating Fgf23 concentrations. Bone. 2005 Jun;36(6):971-7. [CrossRef]

- Perwad F, Azam N, Zhang MY, Yamashita T, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology. 2005 Dec;146(12):5358-64. [CrossRef]

- Courbebaisse M, Lanske B. Biology of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23: From Physiology to Pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 May 1;8(5):a031260. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji K, Maeda T, Kawane T, Matsunuma A, Horiuchi N. Leptin stimulates fibroblast growth factor 23 expression in bone and suppresses renal 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis in leptin-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Aug;25(8):1711-23. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Quarles LD. How fibroblast growth factor 23 works. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Jun;18(6):1637-47. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari SL, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. Fibroblast growth factor-23 relationship to dietary phosphate and renal phosphate handling in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Mar;90(3):1519-24. [CrossRef]

- Tenenhouse HS, Gauthier C, Chau H, St-Arnaud R. 1alpha-Hydroxylase gene ablation and Pi supplementation inhibit renal calcification in mice homozygous for the disrupted Npt2a gene. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004 Apr;286(4):F675-81. [CrossRef]

- Knab VM, Corbin B, Andrukhova O, Hum JM, Ni P, Rabadi S, Maeda A, White KE, Erben RG, Jüppner H, et al. Acute parathyroid hormone injection increases C-terminal but not intact fibroblast growth factor 23 levels. Endocrinology. 2017 May 1;158(5):1130-39. [CrossRef]

- Meir T, Durlacher K, Pan Z, Amir G, Richards WG, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. Parathyroid hormone activates the orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1 to induce FGF23 transcription. Kidney Int. 2014 Dec;86(6):1106-15. [CrossRef]

- White KE, Carn G, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Benet-Pages A, Strom TM, Econs MJ. Autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) mutations stabilize FGF-23. Kidney Int. 2001 Dec;60(6):2079-86. [CrossRef]

- Ho BB, Bergwitz C. FGF23 signalling and physiology. J Mol Endocrinol. 2021 Feb;66(2):R23-R32. [CrossRef]

- Tagliabracci VS, Engel JL, Wiley SE, Xiao J, Gonzalez DJ, Nidumanda Appaiah H, Koller A, Nizet V, White KE, Dixon JE. Dynamic regulation of FGF23 by Fam20C phosphorylation, GalNAc-T3 glycosylation, and furin proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Apr 15;111(15):5520-5. [CrossRef]

- Edmonston D, Wolf M. FGF23 at the crossroads of phosphate, iron economy and erythropoiesis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020 Jan;16(1):7-19. [CrossRef]

- Kato K, Jeanneau C, Tarp MA, Benet-Pagès A, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bennett EP, Mandel U, Strom TM, Clausen H. Polypeptide GalNAc-transferase T3 and familial tumoral calcinosis. Secretion of fibroblast growth factor 23 requires O-glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 2006 Jul 7;281(27):18370-7. [CrossRef]

- Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Pastor J, Nakatani T, Lanske B, Razzaque MS, Rosenblatt KP, Baum MG, Kuro-o M, et al. Klotho: a novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB J. 2010 Sep;24(9):3438-50. [CrossRef]

- Gattineni J, Alphonse P, Zhang Q, Mathews N, Bates CM, Baum M. Regulation of renal phosphate transport by FGF23 is mediated by FGFR1 and FGFR4. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014 Feb 1;306(3):F351-8. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Liu Y, Goetz R, Fu L, Jayaraman S, Hu MC, Moe OW, Liang G, Li X, Mohammadi M. α-Klotho is a non-enzymatic molecular scaffold for FGF23 hormone signalling. Nature. 2018 Jan 25;553(7689):461-6. [CrossRef]

- Xu D, Esko JD. Demystifying heparan sulfate-protein interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:129-57. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal A, Ni P, Agoro R, White KE, DiMarchi RD. Identification of a second Klotho interaction site in the C terminus of FGF23. Cell Rep. 2021 Jan 26;34(4):108665. [CrossRef]

- Andrukhova O, Zeitz U, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Lanske B, Erben RG. FGF23 acts directly on renal proximal tubules to induce phosphaturia through activation of the ERK1/2-SGK1 signaling pathway. Bone. 2012 Sep;51(3):621-8. [CrossRef]

- Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Addo T, Cho HJ, Barker SL, Ravikumar P, Gillings N, Bian A, Sidhu SS, et al. Renal production, uptake, and handling of circulating αKlotho. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Jan;27(1):79-90. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Yang J, Li L, Huang J, King G, Quarles LD. Conditional Deletion of Fgfr1 in the Proximal and distal tubule identifies distinct roles in phosphate and calcium transport. PLoS One. 2016 Feb 3;11(2):e0147845. [CrossRef]

- Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015 May-Jun;4(3):215- 66. [CrossRef]

- Déliot N, Hernando N, Horst-Liu Z, Gisler SM, Capuano P, Wagner CA, Bacic D, O’Brien S, Biber J, Murer H. Parathyroid hormone treatment induces dissociation of type IIa Na+-P(i) cotransporter-Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 complexes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005 Jul;289(1):C159-67. [CrossRef]

- Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006 Dec 7;444(7120):770-4. [CrossRef]

- Ide N, Olauson H, Sato T, Densmore MJ, Wang H, Hanai JI, Larsson TE, Lanske B. In vivo evidence for a limited role of proximal tubular Klotho in renal phosphate handling. Kidney Int. 2016 Aug;90(2):348-62. [CrossRef]

- Grabner A, Amaral AP, Schramm K, Singh S, Sloan A, Yanucil C, Li J, Shehadeh LA, Hare JM, David V, et al. Activation of Cardiac Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 Causes Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 2015 Dec 1;22(6):1020-32. [CrossRef]

- Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002 Apr;109 Suppl:S67-79. [CrossRef]

- Farrow EG, Davis SI, Summers LJ, White KE. Initial FGF23-mediated signaling occurs in the distal convoluted tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 May;20(5):955-60. [CrossRef]

- Zhang MY, Ranch D, Pereira RC, Armbrecht HJ, Portale AA, Perwad F. Chronic inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling improves disordered bone and mineral metabolism in hypophosphatemic (Hyp) mice. Endocrinology. 2012 Apr;153(4):1806-16. [CrossRef]

- Ranch D, Zhang MY, Portale AA, Perwad F. Fibroblast growth factor 23 regulates renal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and phosphate metabolism via the MAP kinase signaling pathway in Hyp mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2011 Aug;26(8):1883-90. [CrossRef]

- Murer H, Lötscher M, Kaissling B, Levi M, Kempson SA, Biber J. Renal brush border membrane Na/Pi-cotransport: molecular aspects in PTH-dependent and dietary regulation. Kidney Int. 1996 Jun;49(6):1769-73. [CrossRef]

- Murer H, Hernando N, Forster I, Biber J. Proximal tubular phosphate reabsorption: molecular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2000 Oct;80(4):1373-409. [CrossRef]

- Keusch I, Traebert M, Lötscher M, Kaissling B, Murer H, Biber J. Parathyroid hormone and dietary phosphate provoke a lysosomal routing of the proximal tubular Na/Pi-cotransporter type II. Kidney Int. 1998 Oct;54(4):1224-1232. [CrossRef]

- Lötscher M, Scarpetta Y, Levi M, Halaihel N, Wang H, Zajicek HK, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. Rapid downregulation of rat renal Na/P(i) cotransporter in response to parathyroid hormone involves microtubule rearrangement. J Clin Invest. 1999 Aug;104(4):483-94. [CrossRef]

- Tumbarello DA, Kendrick-Jones J, Buss F. Myosin VI and its cargo adaptors - linking endocytosis and autophagy. J Cell Sci. 2013 Jun 15;126(Pt 12):2561-70. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham R, E X, Steplock D, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ. Defective PTH regulation of sodium-dependent phosphate transport in NHERF-1-/- renal proximal tubule cells and wild-type cells adapted to low-phosphate media. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005 Oct;289(4):F933-8. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham R, Biswas R, Brazie M, Steplock D, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ. Signaling pathways utilized by PTH and dopamine to inhibit phosphate transport in mouse renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009 Feb;296(2):F355-61. [CrossRef]

- Lederer ED, Sohi SS, McLeish KR. Dopamine regulates phosphate uptake by opossum kidney cells through multiple counter- regulatory receptors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998 Jun;9(6):975-85. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Shenolikar S, Biswas R. Fibroblast growth factor-23-mediated inhibition of renal phosphate transport in mice requires sodium-hydrogen exchanger regulatory factor-1 (NHERF-1) and synergizes with parathyroid hormone. J Biol Chem. 2011 Oct 28;286(43):37216-21. [CrossRef]

- Shenolikar S, Voltz JW, Minkoff CM, Wade JB, Weinman EJ. Targeted disruption of the mouse NHERF-1 gene promotes internalization of proximal tubule sodium-phosphate cotransporter type IIa and renal phosphate wasting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Aug 20;99(17):11470-5. [CrossRef]

- Voltz JW, Brush M, Sikes S, Steplock D, Weinman EJ, Shenolikar S. Phosphorylation of PDZ1 domain attenuates NHERF-1 binding to cellular targets. J Biol Chem. 2007 Nov 16;282(46):33879-87. [CrossRef]

- Mahon MJ, Donowitz M, Yun CC, Segre GV. Na(+)/H(+ ) exchanger regulatory factor 2 directs parathyroid hormone 1 receptor signalling. Nature. 2002 Jun 20;417(6891):858-61. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler D, Garrido JL, Bisello A, Kim YK, Friedman PA, Romero G. Regulation of parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor dynamics, traffic, and signaling by the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 in rat osteosarcoma ROS 17/2.8 cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008 May;22(5):1163-70. [CrossRef]

- Lee HJ, Zheng JJ. PDZ domains and their binding partners: structure, specificity, and modification. Cell Commun Signal. 2010 May 28;8:8. [CrossRef]

- Dicks M, Kock G, Kohl B, Zhong X, Pütz S, Heumann R, Erdmann KS, Stoll R. The binding affinity of PTPN13’s tandem PDZ2/3 domain is allosterically modulated. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2019 Jul 8;20(1):23. [CrossRef]

- Walker V, Vuister GW. Biochemistry and pathophysiology of the Transient Potential Receptor Vanilloid 6 (TRPV6) calcium channel. Adv Clin Chem. 2023;113:43-100. [CrossRef]

- Sneddon WB, Ruiz GW, Gallo LI, Xiao K, Zhang Q, Rbaibi Y, Weisz OA, Apodaca GL, Friedman PA. Convergent Signaling Pathways Regulate Parathyroid Hormone and Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 Action on NPT2A-mediated Phosphate Transport. J Biol Chem. 2016 Sep 2;291(36):18632-42. [CrossRef]

- Mahon MJ, Segre GV. Stimulation by parathyroid hormone of a NHERF-1-assembled complex consisting of the parathyroid hormone I receptor, phospholipase Cbeta, and actin increases intracellular calcium in opossum kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2004 May 28;279(22):23550-8. [CrossRef]

- Mamonova T, Zhang Q, Chandra M, Collins BM, Sarfo E, Bu Z, Xiao K, Bisello A, Friedman PA. Origins of PDZ Binding Specificity. A Computational and Experimental Study Using NHERF1 and the Parathyroid Hormone Receptor. Biochemistry. 2017 May 23;56(20):2584-93. [CrossRef]

- Mamonova T, Kurnikova M, Friedman PA. Structural basis for NHERF1 PDZ domain binding. Biochemistry. 2012 Apr 10;51(14):3110-20. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal A, Braslavsky D, Lu JT, Kleppe S, Clément F, Cassinelli H, Liu DS, Liern JM, Vallejo G, Bergadá I, Gibbs RA, Campeau PM, Lee BH. Exome sequencing identifies a novel homozygous mutation in the phosphate transporter SLC34A1 in hypophosphatemia and nephrocalcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Nov;99(11):E2451-6. [CrossRef]

- Kang SJ, Lee R, Kim HS. Infantile hypercalcemia with novel compound heterozygous mutation in SLC34A1 encoding renal sodium-phosphate cotransporter 2a: a case report. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Mar;24(1):64-67. [CrossRef]

- Oddsson A, Sulem P, Helgason H, Edvardsson VO, Thorleifsson G, Sveinbjörnsson G, Haraldsdottir E, Eyjolfsson GI, Sigurdardottir O, Olafsson I, Masson G, Holm H, Gudbjartsson DF, Thorsteinsdottir U, Indridason OS, Palsson R, Stefansson K. Common and rare variants associated with kidney stones and biochemical traits. Nat Commun. 2015 Aug 14;6:7975. [CrossRef]

- Howles SA, Wiberg A, Goldsworthy M, Bayliss AL, Gluck AK, Ng M, Grout E, Tanikawa C, Kamatani Y, Terao C, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Matsuda K, Thakker RV, Turney BW, Furniss D. Genetic variants of calcium and vitamin D metabolism in kidney stone disease. Nat Commun. 2019 Nov 15;10(1):5175. [CrossRef]

- Urabe Y, Tanikawa C, Takahashi A, Okada Y, Morizono T, Tsunoda T, Kamatani N, Kohri K, Chayama K, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Matsuda K. A genome-wide association study of nephrolithiasis in the Japanese population identifies novel susceptible Loci at 5q35.3, 7p14.3, and 13q14.1. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002541. [CrossRef]

- Chen WC, Chou WH, Chu HW, Huang CC, Liu X, Chang WP, Chou YH, Chang WC. The rs1256328 (ALPL) and rs12654812 (RGS14) Polymorphisms are Associated with Susceptibility to Calcium Nephrolithiasis in a Taiwanese population. Sci Rep. 2019 Nov 21;9(1):17296. [CrossRef]

- Tanikawa C, Kamatani Y, Terao C, Usami M, Takahashi A, Momozawa Y, Suzuki K, Ogishima S, Shimizu A, Satoh M, Matsuo K, Mikami H, Naito M, Wakai K, Yamaji T, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Tsugane S, Kohri K, Yu ASL, Yasui T, Murakami Y, Kubo M, Matsuda K. Novel Risk Loci Identified in a Genome-Wide Association Study of Urolithiasis in a Japanese Population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 May;30(5):855-64. [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum B, Glazer NL, Köttgen A, Felix JF, Hwang SJ, Liu Y, Lohman K, Kritchevsky SB, Hausman DB, Petersen AK, et al. Common genetic variants associate with serum phosphorus concentration. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Jul;21(7):1223-32. [CrossRef]

- Laster ML, Rowan B, Chen HC, Schwantes-An TH, Sheng X, Friedman PA, Ikizler TA, Sinshiemer JS, Ix JH, Susztak K, et al. Genetic Variants Associated With Mineral Metabolism Traits in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Aug 18;107(9):e3866-e3876. [CrossRef]

- Alqinyah M, Hooks SB. Regulating the regulators: Epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-translational regulation of RGS proteins. Cell Signal. 2018 Jan;42:77-87. [CrossRef]

- Willard FS, Willard MD, Kimple AJ, Soundararajan M, Oestreich EA, Li X, Sowa NA, Kimple RJ, Doyle DA, Der CJ, Zylka MJ, Snider WD, Siderovski DP. Regulator of G-protein signaling 14 (RGS14) is a selective H-Ras effector. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4884. [CrossRef]

- Kimple RJ, De Vries L, Tronchère H, Behe CI, Morris RA, Gist Farquhar M, Siderovski DP. RGS12 and RGS14 GoLoco motifs are G alpha(i) interaction sites with guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor Activity. J Biol Chem. 2001 Aug 3;276(31):29275-81. [CrossRef]

- Siderovski DP, Harden TK. The RGS Protein Superfamily. In Handbook of Cell Signaling, Bradshaw R.A., Dennis E.A., Eds.;Academic Press (Elsevier Inc): Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2003, Volume 2, pp. 631-8 . [CrossRef]

- Sjögren B. The evolution of regulators of G protein signalling proteins as drug targets - 20 years in the making: IUPHAR Review 21. Br J Pharmacol. 2017 Mar;174(6):427-37. [CrossRef]

- Brown NE, Goswami D, Branch MR, Ramineni S, Ortlund EA, Griffin PR, Hepler JR. Integration of G protein α (Gα) signaling by the regulator of G protein signaling 14 (RGS14). J Biol Chem. 2015 Apr 3;290(14):9037-49. [CrossRef]

- Worcester EM, Coe FL. Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 2;363(10):954-63. [CrossRef]

- Adeli K, Higgins V, Nieuwesteeg M, Raizman JE, Chen Y, Wong SL, Blais D. Biochemical marker reference values across pediatric, adult, and geriatric ages: establishment of robust pediatric and adult reference intervals on the basis of the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Clin Chem. 2015 Aug;61(8):1049-62. [CrossRef]

- Saggese G, Baroncelli GI, Bertelloni S, Cinquanta L, Di Nero G. Effects of long-term treatment with growth hormone on bone and mineral metabolism in children with growth hormone deficiency. J Pediatr. 1993 Jan;122(1):37-45. [CrossRef]

- Boot AM, Engels MA, Boerma GJ, Krenning EP, De Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Changes in bone mineral density, body composition, and lipid metabolism during growth hormone (GH) treatment in children with GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Aug;82(8):2423-8. [CrossRef]

- Haffner D, Grund A, Leifheit-Nestler M. Renal effects of growth hormone in health and in kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021 Aug;36(8):2511-30. [CrossRef]

- Quigley R, Baum M. Effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I on rabbit proximal convoluted tubule transport. J Clin Invest. 1991 Aug;88(2):368-74. [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg R, Ding H, Wanner C. Hirschberg R, Ding H, Wanner C. Effects of insulin-like growth factor I on phosphate transport in cultured proximal tubule cells. J Lab Clin Med. 1995 Nov;126(5):428-34.

- Jehle AW, Forgo J, Biber J, Lederer E, Krapf R, Murer H. IGF-I and vanadate stimulate Na/Pi-cotransport in OK cells by increasing type II Na/Pi-cotransporter protein stability. Pflugers Arch. 1998 Dec;437(1):149-54. [CrossRef]

- Palmer G, Bonjour JP, Caverzasio J. Stimulation of inorganic phosphate transport by insulin-like growth factor I and vanadate in opossum kidney cells is mediated by distinct protein tyrosine phosphorylation processes. Endocrinology. 1996 Nov;137(11):4699-705. [CrossRef]

- Marks J, Debnam ES, Unwin RJ. The role of the gastrointestinal tract in phosphate homeostasis in health and chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013 Jul;22(4):481-7. [CrossRef]

- Capuano P, Bacic D, Roos M, Gisler SM, Stange G, Biber J, Kaissling B, Weinman EJ, Shenolikar S, Wagner CA, Murer H. Defective coupling of apical PTH receptors to phospholipase C prevents internalization of the Na+-phosphate cotransporter NaPi- IIa in Nherf1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007 Feb;292(2):C927-34. [CrossRef]

- Murer H, Forster I, Biber J. The sodium phosphate cotransporter family SLC34. Pflugers Arch. 2004 Feb;447(5):763-7. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Lötscher M, Sorribas V, Custer M, Arar M, Kaissling B, Murer H, Biber J. Cellular mechanisms of acute and chronic adaptation of rat renal P(i) transporter to alterations in dietary P(i). Am J Physiol. 1994 Nov;267(5 Pt 2):F900-8. [CrossRef]

- Weinman EJ, Boddeti A, Cunningham R, Akom M, Wang F, Wang Y, Liu J, Steplock D, Shenolikar S, Wade JB. NHERF-1 is required for renal adaptation to a low-phosphate diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003 Dec;285(6):F1225-32. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham R, Steplock D, Wang F, Huang H, E X, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ. Defective parathyroid hormone regulation of NHE3 activity and phosphate adaptation in cultured NHERF-1-/- renal proximal tubule cells. J Biol Chem. 2004 Sep 3;279(36):37815-21. [CrossRef]

- Villa-Bellosta R, Sorribas V. Compensatory regulation of the sodium/phosphate cotransporters NaPi-IIc (SCL34A3) and Pit-2 (SLC20A2) during Pi deprivation and acidosis. Pflugers Arch. 2010 Feb;459(3):499-508. [CrossRef]

- Capuano P, Bacic D, Stange G, Hernando N, Kaissling B, Pal R, Kocher O, Biber J, Wagner CA, Murer H. Expression and regulation of the renal Na/phosphate cotransporter NaPi-IIa in a mouse model deficient for the PDZ protein PDZK1. Pflugers Arch. 2005 Jan;449(4):392-402. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi F, Morita K, Katai K, Segawa H, Fujioka A, Kouda T, Tatsumi S, Nii T, Taketani Y, Haga H, Hisano S, Fukui Y, Miyamoto KI, Takeda E. Effects of dietary Pi on the renal Na+-dependent Pi transporter NaPi-2 in thyroparathyroidectomized rats. Biochem J. 1998 Jul 1;333 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1):175-81. [CrossRef]

- Thomas L, Bettoni C, Knöpfel T, Hernando N, Biber J, Wagner CA. Acute Adaption to Oral or Intravenous Phosphate Requires Parathyroid Hormone. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Mar;28(3):903-14. [CrossRef]

- Scanni R, vonRotz M, Jehle S, Hulter HN, Krapf R. The human response to acute enteral and parenteral phosphate loads. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Dec;25(12):2730-9. [CrossRef]

- Kritmetapak K, Kumar R. Phosphate as a Signaling Molecule. Calcif Tissue Int. 2021 Jan;108(1):16-31. [CrossRef]

- Kido S, Miyamoto K, Mizobuchi H, Taketani Y, Ohkido I, Ogawa N, Kaneko Y, Harashima S, Takeda E. Identification of regulatory sequences and binding proteins in the type II sodium/phosphate cotransporter NPT2 gene responsive to dietary phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1999 Oct 1;274(40):28256-63. [CrossRef]

- Beck L, Tenenhouse HS, Meyer RA, Meyer MH, Biber J, Murer H. Renal expression of Na+-phosphate cotransporter mRNA and protein: effect of the Gy mutation and low phosphate diet. Pflugers Arch. 1996 Apr;431(6):936-41. [CrossRef]

- Hoag HM, Martel J, Gauthier C, Tenenhouse HS. Effects of Npt2 gene ablation and low-phosphate diet on renal Na(+)/phosphate cotransport and cotransporter gene expression. J Clin Invest. 1999 Sep;104(6):679-86. [CrossRef]

- Kilav R, Silver J, Biber J, Murer H, Naveh-Many T. Coordinate regulation of rat renal parathyroid hormone receptor mRNA and Na-Pi cotransporter mRNA and protein. Am J Physiol. 1995 Jun;268(6 Pt 2):F1017-22. [CrossRef]

- Conrads KA, Yi M, Simpson KA, Lucas DA, Camalier CE, Yu LR, Veenstra TD, Stephens RM, Conrads TP, Beck GR Jr. A combined proteome and microarray investigation of inorganic phosphate-induced pre-osteoblast cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005 Sep;4(9):1284-96. [CrossRef]

- Julien M, Magne D, Masson M, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Chassande O, Cario-Toumaniantz C, Cherel Y, Weiss P, Guicheux J. Phosphate stimulates matrix Gla protein expression in chondrocytes through the extracellular signal regulated kinase signaling pathway. Endocrinology. 2007 Feb;148(2):530-7. [CrossRef]

- Nishino J, Yamazaki M, Kawai M, Tachikawa K, Yamamoto K, Miyagawa K, Kogo M, Ozono K, Michigami T. Extracellular Phosphate Induces the Expression of Dentin Matrix Protein 1 Through the FGF Receptor in Osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2017 May;118(5):1151-63. [CrossRef]

- Camalier CE, Yi M, Yu LR, Hood BL, Conrads KA, Lee YJ, Lin Y, Garneys LM, Bouloux GF, Young MR, Veenstra TD, Stephens RM, Colburn NH, Conrads TP, Beck GR Jr. An integrated understanding of the physiological response to elevated extracellular phosphate. J Cell Physiol. 2013 Jul;228(7):1536-50. [CrossRef]

- Bansal N, Hsu CY, Whooley M, Berg AH, Ix JH. Relationship of urine dopamine with phosphorus homeostasis in humans: the heart and soul study. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(6):483-90. [CrossRef]

- Boland JM, Tebben PJ, Folpe AL. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors: what an endocrinologist should know. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018 Oct;41(10):1173-84. [CrossRef]

- Minisola S, Fukumoto S, Xia W, Corsi A, Colangelo L, Scillitani A, Pepe J, Cipriani C, Thakker RV. Tumor-induced Osteomalacia: A Comprehensive Review. Endocr Rev. 2023 Mar 4;44(2):323-53. [CrossRef]

- Folpe AL. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors: A review and update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019 Jul;36(4):260-8. [CrossRef]

- Rowe PS, de Zoysa PA, Dong R, Wang HR, White KE, Econs MJ, Oudet CL. MEPE, a new gene expressed in bone marrow and tumors causing osteomalacia. Genomics. 2000 Jul 1;67(1):54-68. [CrossRef]

- Imanishi Y, Hashimoto J, Ando W, Kobayashi K, Ueda T, Nagata Y, Miyauchi A, Koyano HM, Kaji H, Saito T, Oba K, Komatsu Y, Morioka T, Mori K, Miki T, Inaba M. Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein is expressed in causative tumors of oncogenic osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012 Jan;30(1):93-9. [CrossRef]

- Imel EA, Peacock M, Pitukcheewanont P, Heller HJ, Ward LM, Shulman D, Kassem M, Rackoff P, Zimering M, Dalkin A, Drobny E, Colussi G, Shaker JL, Hoogendoorn EH, Hui SL, Econs MJ. Sensitivity of fibroblast growth factor 23 measurements in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2055–61. [CrossRef]

- Lee JC, Jeng YM, Su SY, Wu CT, Tsai KS, Lee CH, et al.. Identification of a novel FN1-FGFR1 genetic fusion as a frequent event in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour. J Pathol (2015) 235:539–45. [CrossRef]

- Berndt T, Craig TA, Bowe AE, Vassiliadis J, Reczek D, Finnegan R,et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 is a potent tumor- derived phosphaturic agent. J Clin Invest. 2003 Sep;112(5):785-94. [CrossRef]

- Lee JC, Su SY, Changou CA, Yang RS, Tsai KS, Collins MT, et al.. Characterization of FN1-FGFR1 and novel FN1-FGF1 fusion genes in a large series of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors. Mod Pathol (2016) 29:1335–46. [CrossRef]

- Sakai T, Okuno Y, Murakami N, Shimoyama Y, Imagama S, Nishida Y. Case report: Novel NIPBL-BEND2 fusion gene identified in osteoblastoma-like phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the fibula. Front Oncol. 2023 Jan 5;12:956472. [CrossRef]

- Rowe PS, Kumagai Y, Gutierrez G et al. MEPE has the properties of an osteoblastic phosphatonin and minhibin. Bone 2004; 34: 303-19.

- Schrauwen I, Valgaeren H, Tomas-Roca L, Sommen M, Altunoglu U, Wesdorp M, Beyens M, Fransen E, Nasir A, Vandeweyer G, et al. Variants affecting diverse domains of MEPE are associated with two distinct bone disorders, a craniofacial bone defect and otosclerosis. Genet Med. 2019 May;21(5):1199-208. [CrossRef]

- Sprowson AP, McCaskie AW, Birch MA. ASARM-truncated MEPE and AC-100 enhance osteogenesis by promoting osteoprogenitor adhesion. J Orthop Res. 2008 Sep;26(9):1256-62. [CrossRef]

- Rowe PS. The wrickkened pathways of FGF23, MEPE and PHEX. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004 Sep 1;15(5):264-81. [CrossRef]

- Rowe PS. Regulation of bone-renal mineral and energy metabolism: the PHEX, FGF23, DMP1, MEPE ASARM pathway. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2012;22(1):61-86. [CrossRef]

- Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Renal expression of SIBLING proteins and their partner matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Kidney Int. 2005 Jul;68(1):155-66. [CrossRef]

- Ogbureke KU, Koli K, Saxena G. Matrix Metalloproteinase 20 Co-expression With Dentin Sialophosphoprotein in Human and Monkey Kidneys. J Histochem Cytochem. 2016 Oct;64(10):623-36. [CrossRef]

- David V, Martin A, Hedge AM, Rowe PS. Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) is a new bone renal hormone and vascularization modulator. Endocrinology. 2009 Sep;150(9):4012-23. [CrossRef]

- Dobbie H, Unwin RJ, Faria NJ, Shirley DG. Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein causes phosphaturia in rats by inhibiting tubular phosphate reabsorption. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008 Feb;23(2):730-3. [CrossRef]

- Shirley DG, Faria NJ, Unwin RJ, Dobbie H. Direct micropuncture evidence that matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein inhibits proximal tubular phosphate reabsorption. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 Oct;25(10):3191-5. [CrossRef]

- Gowen LC, Petersen DN, Mansolf AL, Qi H, Stock JL, Tkalcevic GT, Simmons HA, Crawford DT, Chidsey-Frink KL, Ke HZ, et al. Targeted disruption of the osteoblast/osteocyte factor 45 gene (OF45) results in increased bone formation and bone mass. J Biol Chem. 2003 Jan 17;278(3):1998-2007. [CrossRef]

- Zelenchuk LV, Hedge AM, Rowe PS. Age dependent regulation of bone-mass and renal function by the MEPE ASARM-motif. Bone. 2015 Oct;79:131-42. [CrossRef]

- Marks J, Churchill LJ, Debnam ES, Unwin RJ. Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein inhibits phosphate transport. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Dec;19(12):2313-20. [CrossRef]

- David V, Martin A, Hedge AM, Drezner MK, Rowe PS. ASARM peptides: PHEX-dependent and -independent regulation of serum phosphate. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011 Mar;300(3):F783-91. [CrossRef]

- Beauvais DM, Ell BJ, McWhorter AR, Rapraeger AC. Syndecan-1 regulates alphavbeta3 and alphavbeta5 integrin activation during angiogenesis and is blocked by synstatin, a novel peptide inhibitor. J Exp Med. 2009 Mar 16;206(3):691-705. [CrossRef]

- Tenenhouse HS, Lee J, Harvey N, Potier M, Jette M, Beliveau R. Normal molecular size of the Na(+)-phosphate cotransporter and normal Na(+)-dependent binding of phosphonoformic acid in renal brush border membranes of X-linked Hyp mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Aug 16;170(3):1288-93. [CrossRef]

- Berndt TJ, Bielesz B, Craig TA, Tebben PJ, Bacic D, Wagner CA, O’Brien S, Schiavi S, Biber J, Murer H, et al. Secreted frizzled- related protein-4 reduces sodium-phosphate co-transporter abundance and activity in proximal tubule cells. Pflugers Arch. 2006 Jan;451(4):579-87. [CrossRef]

- Habra MA, Jimenez C, Huang SC, Cote GJ, Murphy WA Jr, Gagel RF, Hoff AO. Expression analysis of fibroblast growth factor- 23, matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein, secreted frizzled-related protein-4, and fibroblast growth factor-7: identification of fibroblast growth factor-23 and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein as major factors involved in tumor-induced osteomalacia. Endocr Pract. 2008 Dec;14(9):1108-14. [CrossRef]