Introduction

Autosomal polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is an inherited renal tubular disorder affecting 1 in 500-2.500 people worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Although cysts development occur early in life, even in utero in some cases [

5,

6], progressive renal function decline seems to be linked rather to the early hyperfiltration state of the kidney than the loss of kidney function [

7]. However, glomerular hyperfiltration is associated with kidney enlargement which in turn is a sign of progressive decline in renal function [

8].

Kidney enlargement is the cardinal sign of progressive cystic dilatation of the renal tubules with variable echogenicity. This structural change in the renal parenchyma lead to a wide spectrum of complications: arterial hypertension [

9], proteinuria [

10], cerebral aneurysms [

11], nephrolithiasis [

12], hematuria [

13], and urinary tract infections [

14]. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decline occurs later in life, in the fourth or fifth decade of life [

15], as a consequence of prolonged renal compensation [

16].

Renal abnormalities in young adults with ADPKD are present even in near-normal GFR with modestly enlarged kidneys, including a decreased effective renal plasma flow and increased filtration flow, and higher urinary albumin excretion [

17]. However prolonged hyperfiltration in children with ADPKD is associated with a faster decline in renal function [

7].

The cardinal sign of ADPKD is the incidental finding of renal cysts detected by ultrasound scans regardless of the child’s age. Nevertheless, genetic testing should be performed in patients at risk for ADPKD when a family history is present, and in patients with positive ultrasound testing. While the inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant, the penetrance is incomplete with varying phenotypes [

19]. The mutations occur in two genes, PKD1 (chromosome 16p13.3), and PKD2 (chromosome 4p21) which encodes the polycystin-1 (PC1) and polycystin-2 (PC2) respectively [

20]. PKD1 mutations account for up to 85% of the cases worldwide as compared to the 15-23.8% prevalence of PKD2 mutations [

21,

22].

Given the paucity of data regarding ADPKD epidemiology in children and associated renal alterations from childhood, we performed an observational retrospective study of children with ADPKD from west Romania. The main objective was to determine the rate of GFR decline between different age spectrums. The second objective was represented by the utility of personalized ultrasound kidney percentiles in assessing renal filtration rates in children with ADPKD. Also, we determined the degree of renal complications based on PKD genes mutations.

Material and Methods

Study Design

We conducted an observational retrospective cohort study of all patients admitted in a tertiary children’s hospital from west Romania. Data were retrieved from the Hospital’s Electronic System from 2014 until 2024.

Inclusion criteria were: the presence of unilateral or bilateral renal cysts in the renal ultrasound evaluation with at least one serum creatinine measurement during admission. Exclusion criteria were all patients with renal cysts with aetiology other than ADPKD, and patients with autosomal recessive PKD.

All patients were screened for renal cysts using 2D renal ultrasound performed by the same operator. Cysts size and number were recorded in each patient. All biological parameters were obtained during the first hospitalization and at follow-up visits in the same day the ultrasound was performed. Genetic testing and family history were noted during the first hospital admission. Follow-up was performed yearly using renal ultrasound, biological parameters and anthropometric measurements. The final cohort consisted of 16 patients with ADPKD, with 8 patients followed-up for at least one year.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Louis Turcanu” Emergency Hospital for Children, from Timisoara, Romania. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived.

Outcomes and Definitions

The primary outcome was to determine the rate of estimated GFR (eGFR) decline in children with ADPKD. The serum creatinine was measured using the Jaffe method. In order to determine the compensated Jaffe method corrected to total serum protein concentration we employed the following equation for all serum creatinine measurements, regardless of age [

23]:

The compensated Jaffe serum creatinine levels were employed in the quadratic formula to estimate the GFR (qGFR) in children from 1 to 16 years old as follows [

24]:

qGFR= 0.68 x (height/serum creatinine) – 0.0008 x (height/serum creatinine)2 + 0.48 x age – 21.53, in females And,

qGFR= 0.68 x (height/serum creatinine) – 0.0008 x (height/serum creatinine)2 + 0.48 x age – 25.68, in males.

Height was measured in cm, serum creatinine in mg/dl, and age in years. For comparison reasons we also employed the modified Schwartz formula in children 1 to 16 years old [

25]:

However, the modified Schwartz formula was developed for enzymatic determination of serum creatinine, thus we applied the following equation to the corrected serum creatinine levels in order to determine the equivalent serum creatinine from the enzymatic method [

23]:

In children under 1 year, the formula developed by Brion [

26] was used to determine the eGFR as follows:

For conversion from µmol/l to mg/dl a correction factor of 88.4 was performed.

Hyperfiltration was considered in children with higher eGFR than the ones reported in

Table 1 [

27,

28,

29].

The ultrasound was used to determine kidney length and parenchymal index, size and number of the renal cysts. The kidney percentiles were calculated for age, height, and body surface area [

30,

31].

Proteinuria, quantified by 24 hour urine collection, albuminuria (from spot urine) and hematuria were assessed as markers of kidney damage in children with ADPKD.

Variables of Interest

We noted gender, age, height, weight, family history and serum creatinine measurements in the same day the kidney ultrasound was performed. Yearly follow-up was obtained in half the patients. The eGFRs were compared to kidney size, cysts and affected genes.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means and standard deviation or medians and interquartile range for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical ones. The continuous variables were tested for normal distribution with Shapiro-Wilk test. The statistical test used for comparison between continuous variables with normal distribution was independent t-test or ANOVA and for the ones without normal distribution, Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis as appropriate. Categorical variables were evaluated with the Chi-square test. The correlation between specific continuous variables was evaluated using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using MedCalc

® Statistical Software version 22.021 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium;

https://www.medcalc.org; 2024).

Results

The cohort consisted of 16 children, with a predominance of female gender (75%) with a mean age of 9.09 years with standard deviation of 5.74. Patient’s characteristics were noted in

Table 2. All children were screened by renal ultrasound followed by genetic testing in 75%. PKD1 and PKD2 mutation were found in 37.5% of the cases. 25% were not tested for the genetic mutation, yet, half of them presented with a positive family history. Overall, 56.2% of the cohort had a positive family history of ADPKD. The youngest 2 patients (1 month and 6 months respectively) had renal cysts detected intrauterine, that underwent genetic testing in the first 6 months after birth with PKD2 gene identified. After excluding the aforementioned infants, the average children’s age at the time of the diagnosis was 10.35 ± 4.93 years.

Renal ultrasound detected 56.25% of the children with bilateral renal cysts with maximum cysts diameter of 0.75 cm (IQR 0.5-1.6 cm). The renal parenchyma index was 0.75 cm (IQR 0.7-0.83) with statistical differences among children with PKD1, PKD2, and the untested ones. The average kidney length was 10.27cm (IQR 9.2-11.27), with no differences between kidneys length. However, kidney length differed when compared to the gene mutation: children with PKD1 gene mutation had mean kidney length of 9.57cm (IQR 6.88-10.25), much lower when compared to those with PKD2 gene mutation whom had a mean length of 11.27 cm (IQR 10.95-11.62).

We analysed kidney size using percentiles for age, height and body surface area as seen in

Table 2. There were no statistical differences between the 3 percentiles. The mean percentile in children with ADPKD from our cohort was over 90%, regardless the percentile used.

The mean serum creatinine level at diagnosis was 40.06 ± 17.54 µmol/l. After performing the correction of the serum creatinine to protein concentration, the mean compensated serum creatinine was 39.67 ± 17.54 µmol/l. The enzymatic serum creatinine level of 40.83 ± 17.98 µmol/l was estimated using the compensated serum creatinine level after applying the correction for total serum proteins. There were no differences between the methods used to measure the serum creatinine levels as all children had normal serum protein levels. However, even though there were no statistical differences between eGFR and qGFR, qGFR tended to be lower, 111.95 ± 12.43 ml/min/1.73m

2 compared to Schwartz eGFR 126.28 ± 33.07ml/min/1.73m

2, p=0.14. In addition, the GFR values were similar in both identified genetic mutations, even in those whom were not tested (

Table 3).

Based on estimations in GFR according to Brion, Schwartz and quadratic formulas, the rates of glomerular hyperfiltration (GHF) were noted in both the initial presentation and in the 1-year follow-up (Supplemental

Table S1). On one hand, infants under 1 year old, did not reached the hyperfiltration state at the initial presentation, however, at the 1 year follow-up, the Schwartz formula classified both children with GHF as opposed to the quadratic formula where none reached the hyperfiltration thresholds. On the other hand, four out of the six children over 2 years were classified as having GHF rates (over 135ml/min/1.73m

2) as opposed to the quadratic formula, where none of the children reached the GHF thresholds. Interestingly, at the 1-year follow-up, there were still 4 out of 6 children with GHF when the Schwartz formula was applied and still no patient in the GHF state when quadratic formula was applied.

The most common complications were represented by urinary tract infections (50%), followed by nephrolithiasis and vesical-ureteral reflux in 12.5% of the cohort. Markers of kidney damage were also present at the time of the diagnosis, with microscopic haematuria being present in 31.25% of the children followed by proteinuria in 12.5% of the cases.

Another aspect that was taken under consideration was the presence of other genetic anomalies in children with ADPKD. Three patients with PKD2 gene mutation had another genetic disorder that overlapped ADPKD. Two sisters were with Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy and one girl with Wilms tumour whom underwent total right nephrectomy 3 years prior to the diagnosis of ADPKD.

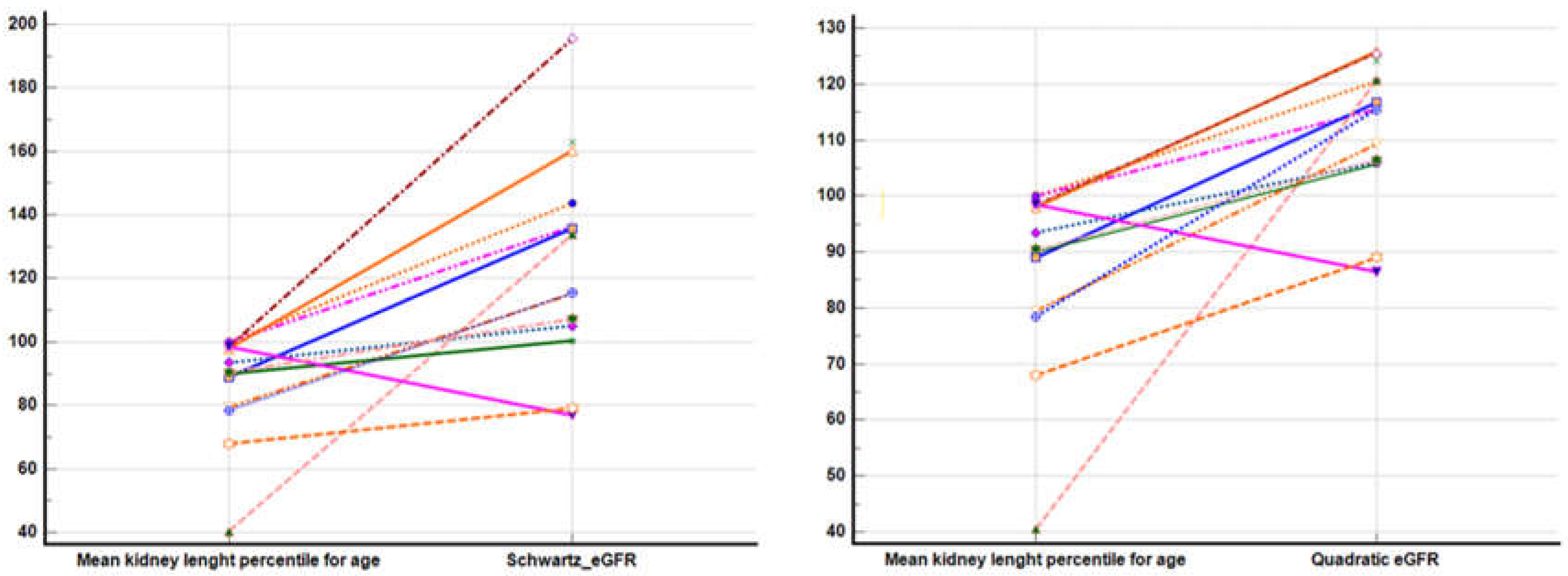

Follow-up was performed in half the patients. Unexpectedly, when we employed both GFR equations, the Schwartz formula tended to overestimate the GFR, with a marked increase in the estimation when compared to the quadratic formula. These results underline that even though kidney enlargement was present, the renal function seemed to be preserved when quadratic formula was applied (

Figure 1). These results were further analysed as delta differences between estimated GFRs. At the initial presentation and at follow-up, the mean GFR was overestimating the renal function when comparing the Schwartz formula to the quadratic one (137.55 versus 118.08ml/min/1.73m

2 at initial presentation and 145.05 versus 117.75ml/min/1.73m

2 at the 1-year follow-up). While Schwartz formula proved to increase over 1 year with a ΔeGFR=7.51±19.46ml/min/1.73m

2, the quadratic formula showed an annual decrease in eGFR of 0.32±5.78ml/min/1.73m

2 (p=0.019).

Discussions

With this study, we estimated the rates of glomerular filtration in children with ADPKD using adapted formulas for age, Brion and Schwartz equations respectively. In addition, we employed the quadratic formula in children over 1 year old for comparison reasons. Almost all children had enlarged kidneys at the time of the diagnosis, however kidneys size did not correlate with hyperfiltration states. Although there were no statistical differences between Schwartz and quadratic eGFR values, the Schwartz formula seems to falsely classify patients in a GHF state when compared to quadratic formula. Markers of kidney damage and complications occur early in childhood.

The age distribution was heterogeneous, from 1 month until 16 years old, with a predominance of the female gender similar to published data [

19]. The very early onset of ADPKD was similar to literature reports (12%) [

32]. The incidental finding of cysts during renal ultrasound, kidney size and positive family history led to the genetic testing of these patients. Due to the small size of the cohort, the identified mutations were equally distributed, even though the literature reports PKD1 gene mutations in over 85% of the ADPKD patients [

21,

22].

Overall, kidney enlargement was estimated using kidney length percentile adjusted for age, height, and body surface area. Even though, over 80% of the children had at the time of the diagnosis increased kidney size, evidenced by 90% percentile, PKD1 mutation seemed to associate lower kidney size and kidney length percentiles when compared to PKD2 mutations, but without reaching statistical significance. This is important, as these patients also had lower age, smaller renal cysts and reduced parenchymal index. It seems that PKD1 gene mutation is associated with worse renal outcomes [

21].

Although this is a small size study, the family history was positive in over 50% of the cases with a 75% genetic testing rate. Currently, the ADPKD guidelines in children under 18 years old recommend genetic testing to be deferred in asymptomatic at risk children without renal cysts on ultrasound [

18]. However, renal ultrasound cannot exclude ADPKD [

33], and it can only be used as a complementary tool in children at risk or with ADPKD. Albeit, family history proved to have a prognostic value in patients with ADPKD [

21], in families with a known genotype, genetic testing is most likely informative [

22]. However, in our cohort, all children had incidental renal cysts detected during ultrasound doubled by increased renal size when renal percentiles were calculated.

The incidental finding of ADPKD was linked to the recurrent UTI episodes that were investigated by renal ultrasound. Also, the three patients with another genetic disease were diagnosed after the incidental finding of the renal cysts on ultrasound. In addition, the presence of the PKD2 gene mutation in these patients could be an indicator of a milder disease course [

21].

The utility of serum creatinine in stable renal function has made this endogenous marker to be used worldwide as a marker of kidney function. The revised Schwartz formula is the most commonly used equation in children over 1 year old [

25]. However, previously published reports showed that in children with a GFR over 90ml/min/1.73m

2, the Schwartz formula loses its accuracy [

24,

34,

35]. In addition, creatinine-based formulas for estimating GFR are dependent of the accuracy of the serum creatinine measurement. The currently used Schwartz formula is applicable when serum creatinine is determined using the enzymatic method [

25]. This is why, we used the corrected compensated Jaffe serum creatinine to estimate the enzymatic serum creatinine that we used in GFR estimations in all children. Furthermore, we employed the quadratic eGFR in children over 1 year old, as this formula has been validated against inulin clearance in children with renal failure and also in children with normal or supra-normal GFR (including hyperfiltration) [

24].

Our results are contradictory, even though they failed to reach statistical significance. It seems that Schwartz formula overestimates the eGFR when compared to the quadratic formula. Even more, the quadratic formula proved that the loss of kidney function is evident after the 1-year follow-up as opposed to the Schwartz formula that tends to continue in a GHF state, reaching statistical significance even in a reduced size cohort like ours. Although the GHF thresholds derive from systematic reviews, the most recent review by Pottel from 2022 gathered the GHF threshold in children [

36]. The consensus GHF rates are categorized by age, reducing the bias in children under 2 years old. With this small sized study we draw attention on the false GHF state induced by the Schwartz formula. The serum creatinine levels did not increase over time, yet the children had a linear growth spur leading to overestimation of GFR when Schwartz formula was employed. The quadratic equation takes into account the age and the sex of the patients besides the height and serum creatinine level from the Schwartz formula [

24,

25].

Kidney enlargement was classically determined by the total kidney volume in both adults and children [

4,

16,

17]. The use of kidney percentiles combined with genotype can be a predictor for rapid progression in ADPKD as previously published by Chen [

37]. In our study, even though all children presented with kidney enlargement the GHF thresholds were reached only in children over 2 years old when Schwartz formula was used. Although renal length was over the 90% percentile, there was no correlation between renal length and eGFR, as it was previously showed [

8]. Interestingly, when Schwartz formula was used to estimate GFR, GHF was more frequently seen in patients with PKD1 gene mutation rather than PKD2, consistent in the 1-year follow-up. However these results should be interpreted cautiously, mostly due to the small size and also the overestimation of Schwartz eGFR when compared to qGFR, as we proved that Schwartz falsely classify children with ADPKD in GHF state.

The main limitation of our study is related to the small cohort size and the reduced follow-up. To our knowledge this is the first study from an East European country that evaluates the GFR dynamics in children with ADPKD. In addition, this is the first study that proves the importance of quadratic GFR as a tool for a more precise renal function evaluation.

In conclusion, the eGFR is more likely to be normal or near normal in children under 18 years old with ADPKD when quadratic GFR is used. Although, children with ADPKD have increased renal length, this is not associated to a hyperfiltration rate. In addition, quadratic eGFR showed that the glomerular filtration rate is linear or even decreasing as opposed to Schwartz that is most likely prone to overestimate eGFR. Future studies with larger cohorts are needed to implement the quadratic GFR formula in patients at risk for GHF.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.S. and F.C.; methodology, R.F.S. and F.C.; software, R.M.S.; validation, R.S and M.G.; formal analysis, F.C; investigation, R.M.S. and F.C.; resources, F.C.; data curation, R.S. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.C and M.G.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, R.F.S.; project administration, R.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC is covered by the “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the “Louis Turcanu” Children’s Emergency Hospital, Timisoara, Romania.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dalgaard, O.Z. Bilateral polycystic disease of the kidneys; a follow-up of two hundred and eighty-four patients and their families. . 1957, 328, 1–255. [Google Scholar]

- Willey, C.J.; Blais, J.D.; Hall, A.K.; Krasa, H.B.; Makin, A.J.; Czerwiec, F.S. Prevalence of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the European Union. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 32, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanktree, M.B.; Haghighi, A.; Guiard, E.; Iliuta, I.-A.; Song, X.; Harris, P.C.; Paterson, A.D.; Pei, Y. Prevalence Estimates of Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease by Population Sequencing. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2593–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solazzo, A.; Testa, F.; Giovanella, S.; Busutti, M.; Furci, L.; Carrera, P.; Ferrari, M.; Ligabue, G.; Mori, G.; Leonelli, M.; et al. The prevalence of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): A meta-analysis of European literature and prevalence evaluation in the Italian province of Modena suggest that ADPKD is a rare and underdiagnosed condition. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0190430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, D.H.; E Lee, M.; Manco-Johnson, M.L.; Weingast, G.R.; Sedman, A.B.; A Gabow, P. Diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in utero and in the young infant. J. Ultrasound Med. 1987, 6, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDermot, K.D.; Saggar-Malik, A.K.; Economides, D.L.; Jeffery, S. Prenatal diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (PKD1) presenting in utero and prognosis for very early onset disease. J. Med Genet. 1998, 35, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helal, I.; Reed, B.; McFann, K.; Yan, X.-D.; Fick-Brosnahan, G.M.; Cadnapaphornchai, M.; Schrier, R.W. Glomerular Hyperfiltration and Renal Progression in Children with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 2439–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.; Vivian, L.; Weiler, G.; Filler, G. Patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease hyperfiltrate early in their disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004, 43, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helal, I.; Reed, B.; McFann, K.; Yan, X.-D.; Fick-Brosnahan, G.M.; Cadnapaphornchai, M.; Schrier, R.W. Glomerular Hyperfiltration and Renal Progression in Children with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 2439–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.B.; Johnson, A.M.; A Gabow, P.; Schrier, R.W. Overt proteinuria and microalbuminuria in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1994, 5, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, S.; Nakajima, M.; Fukuda, K.; Nobayashi, M.; Sakaki, T.; Aoki, K.; Hirao, Y.; Yoshioka, A. A 4-year-old girl with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease complicated by a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2004, 163, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiura, J.A.A.L.; Neves, R.F.; Eloi, S.R.; Cintra, S.M.; Ajzen, S.A.; Heilberg, I.P. Evaluation of Nephrolithiasis in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, B.; Alzubaidi, M.; Velez, J.C.Q. Evaluation and Management of Gross Hematuria in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Point of Care Guide for Practicing Internists. Am. J. Med Sci. 2018, 356, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idrizi, A.; Barbullushi, M.; Koroshi, A.; Dibra, M.; Bolleku, E.; Bajrami, V.; Xhaferri, X.; Thereska, N. Urinary Tract Infections in polycystic Kidney Disease. Med Arch. 2011, 65, 213–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Higashihara, S. E. Higashihara, S. Horie, S. Muto; et al. Renal disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease Clin Exp Nephrol, 16 (2012), pp. 622-628.

- Grantham JJ, Chapman AB, Torres VE. Volume progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The major factor determining clinical outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:148–57.

- Meijer, E.; Rook, M.; Tent, H.; Navis, G.; van der Jagt, E.J.; de Jong, P.E.; Gansevoort, R.T. Early Renal Abnormalities in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, J.; Winyard, P.; Marlais, M.; Cuthell, O.; Harris, T.; Chong, J.; Sayer, J.; Gale, D.P.; Moore, L.; Turner, K.; et al. Clinical practice guideline monitoring children and young people with, or at risk of developing autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.R.; Moore, B.S.; Luo, J.Z.; Sartori, G.; Fang, B.; Jacobs, S.; Abdalla, Y.; Taher, M.; Carey, D.J.; Triffo, W.J.; et al. Exome Sequencing of a Clinical Population for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. JAMA 2022, 328, 2412–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadnapaphornchai, M.A. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2015, 27, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, M.; Cil, O.; Paterson, A.D.; Wang, K.; He, N.; Dicks, E.; Parfrey, P.; Pei, Y. Family History of Renal Disease Severity Predicts the Mutated Gene in ADPKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1833–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrézet, M.-P.; Gall, E.C.-L.; Chen, J.-M.; Redon, S.; Quéré, I.; Creff, J.; Bénech, C.; Maestri, S.; Le Meur, Y.; Férec, C. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: Comprehensive mutation analysis of PKD1 and PKD2 in 700 unrelated patients. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speeckaert, M.M.; Wuyts, B.; Stove, V.; Walle, J.V.; Delanghe, J.R. Compensating for the influence of total serum protein in the Schwartz formula. cclm 2012, 50, 1597–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, A.; Cachat, F.; Faouzi, M.; Bardy, D.; Mosig, D.; Meyrat, B.-J.; Girardin, E.; Chehade, H. Comparison of the glomerular filtration rate in children by the new revised Schwartz formula and a new generalized formula. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.J.; Tilde]Oz, A.M.; Schneider, M.F.; Mak, R.H.; Kaskel, F.; Warady, B.A.; Furth, S.L. New Equations to Estimate GFR in Children with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brion, L.P.; Fleischman, A.R.; McCarton, C.; Schwartz, G.J. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in low birth weight infants during the first year of life: Noninvasive assessment of body composition and growth. J. Pediatr. 1986, 109, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepsz A, Tondeur M, Ham H (2006) Revisiting normal 51Crethylenediaminetetraacetic acid clearance values in children. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 33:1477–1482.

- Cachat F, Combescure C, Cauderay M, Girardin E, Chehade H (2015) A systematic review of glomerular hyperfltration assessment and defnition in the medical literature. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10:382–389.

- Blake GM, Gardiner N, Gnanasegaran G, Sabina D (2005) Reference ranges for 51Cr-EDTA measurements of glomerular fltration rate in children. Nucl Med Commun 26:983–987.

- Obrycki. ; Sarnecki, J.; Lichosik, M.; Sopińska, M.; Placzyńska, M.; Stańczyk, M.; Mirecka, J.; Wasilewska, A.; Michalski, M.; Lewandowska, W.; et al. Kidney length normative values — new percentiles by age and body surface area in Central European children and adolescents. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 38, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrycki. ; Sarnecki, J.; Lichosik, M.; Sopińska, M.; Placzyńska, M.; Stańczyk, M.; Mirecka, J.; Wasilewska, A.; Michalski, M.; Lewandowska, W.; et al. Kidney length normative values in children aged 0–19 years — a multicenter study. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2021, 37, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.K.; Mutlubaş, F.; Soyaltin, E.; Alparslan, C.; Arya, M.; Alaygut, D.; Çamlar, S.A.; Berdeli, A.; Yavaşcan. Demographic and clinical characteristics of children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a single center experience. Turk. J. Med Sci. 2021, 51, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Gabow, P.; Kimberling, W.J.; Strain, J.D.; Manco-Johnson, M.L.; Johnson, A.M. Utility of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1997, 8, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchetta, J.; Cochat, P.; Rognant, N.; Ranchin, B.; Hadj-Aissa, A.; Dubourg, L. Which Creatinine and Cystatin C Equations Can Be Reliably Used in Children? Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottel, H.; Mottaghy, F.M.; Zaman, Z.; Martens, F. On the relationship between glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine in children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2009, 25, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottel, H.; Adebayo, O.C.; Nkoy, A.B.; Delanaye, P. Glomerular hyperfiltration: part 1 — defining the threshold — is the sky the limit? Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 38, 2523–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.W.C.; Chong, J.; Valluru, M.K.; Durkie, M.; Simms, R.J.; Harris, P.C.; Ong, A.C.M. Combining genotype with height-adjusted kidney length predicts rapid progression of ADPKD. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).