Submitted:

22 March 2024

Posted:

25 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Isolation and Characterization of Marine Polysaccharides

2.3. Preparation of Topical Gels

2.4. Animals

2.5. Burn Wound Model and Study Design

2.6. Burn Wound Healing Assessment

2.6.1. Clinical Evaluation and Assessment of Wound Area, Skin Texture and Haemoglobin

2.6.2. Assessment of Biophysical Skin Parameters

2.6.3. Histopathological Analysis

2.6.4. Measurement of FT-IR Spectra

2.6.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Evaluation

3.2. Assessment of Burn Wound in Relation to the Recovery of the Damaged Area

3.3. Histopathological Evaluation

3.4. Assessment of Haemoglobin Levels and Skin Texture

3.5. Evaluation of Biophysical Parameters

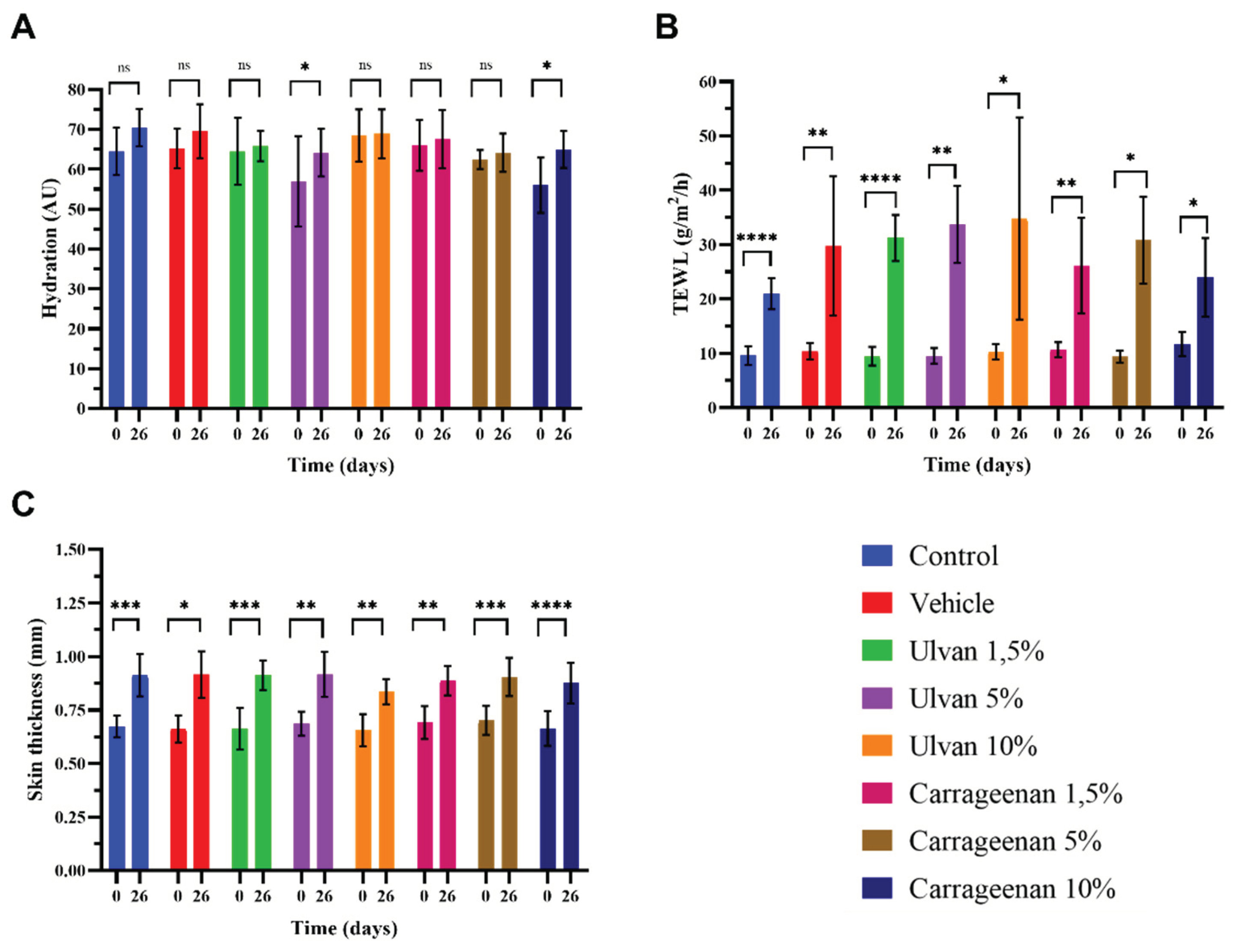

- Analysis showed that on day 26, the hydration of the mice skin treatedwith the 5% w/w ulvan and 10% w/w carrageenan gels was significantly higher compared to day 0, while in all other cases the hydration returned to normal (Figure 5A). TEWL didnot recover to normal with any of the treatments, which indicates that the skin barrier did not return to its normal structure (Figure 5B). Skin thickness was significantly increased in all cases, which is justified after the burn injury (Figure 5C).

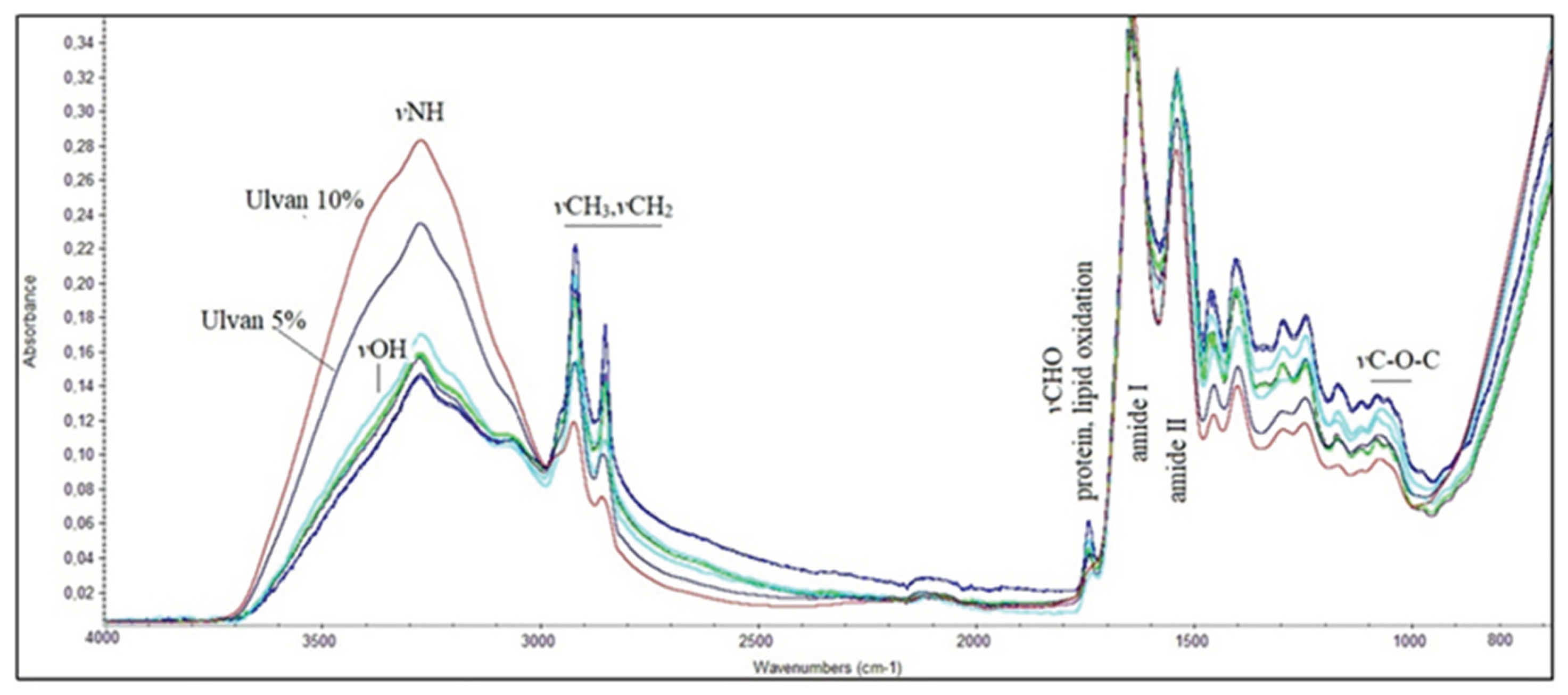

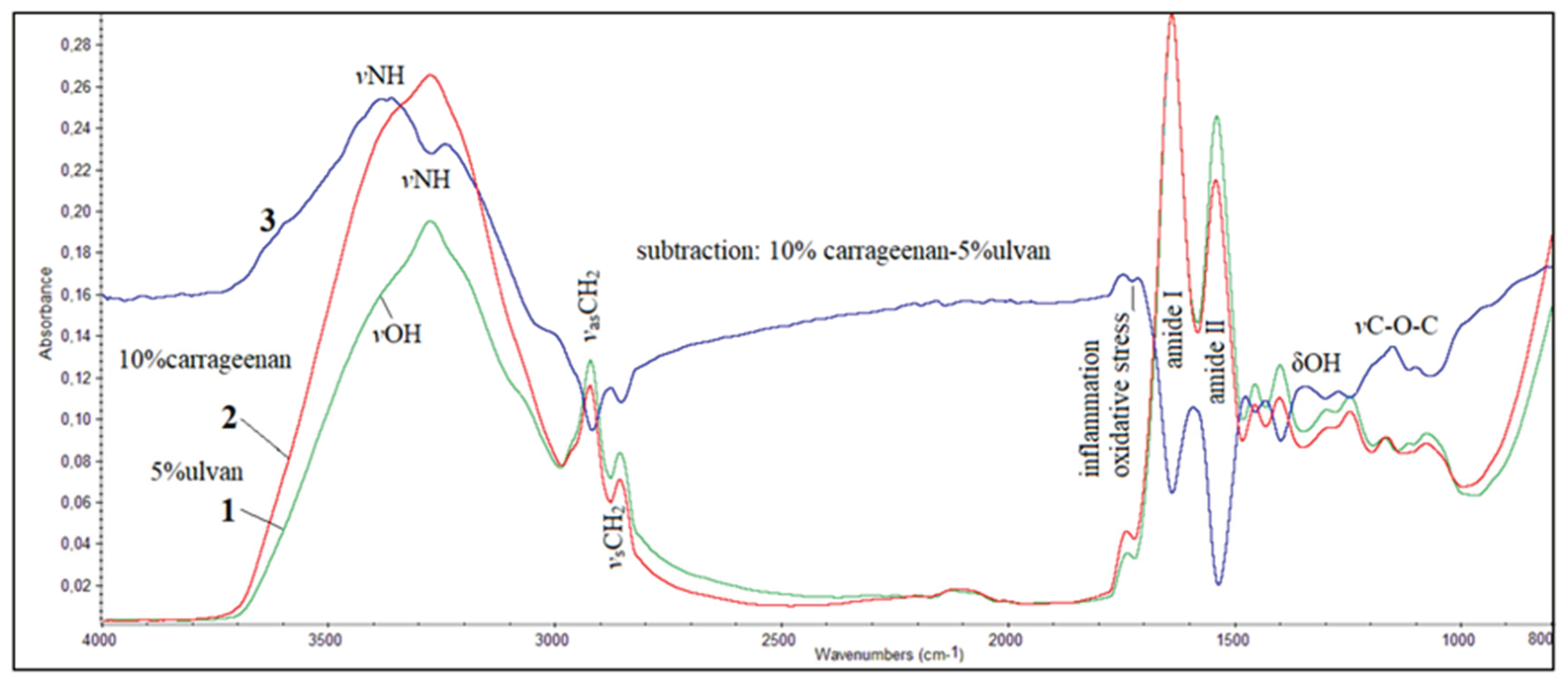

3.6. FT-IR Spectroscopic Analysis of Mice Skin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Burns. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Jeschke, M.G.; van Baar, M.E.; Choudhry, M.A.; Chung, K.K.; Gibran, N.S.; Logsetty, S. Burn injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Beekman, J.; Hew, J.; Jackson, S.; Issler-Fisher, A.C.; Parungao, R.; Lajevardi, S.S.; Li, Z.; Maitz, P.K.M. Burn injury: Challenges and advances in burn wound healing, infection, pain and scarring. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 123, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markiewicz-Gospodarek, A.; Kozioł, M.; Tobiasz, M.; Baj, J.; Radzikowska-Büchner, E.; Przekora, A. Burn wound healing: Clinical complications, medical care, treatment, and dressing types: The current state of knowledge for clinical practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warby, R.; Maani, C.V. Burn Classification. 2023. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539773/(Updated 2023 Sep 26).

- Abazari, M.; Ghaffari, A.; Rashidzadeh, H.; Badeleh, S.M.; Maleki, Y. A systematic review on classification, identification, and healing process of burn wound healing. Int. J. Low Extrem. Wounds. 2022, 21, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Le, H.; Chang, F. Functional hydrogel dressings for treatment of burn wounds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 788461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang,H. ; Lin,X.; Cao,X.; Wang,Y.; Wang,J.; Zhao, Y. Developing natural polymers for skin wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 33, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, L.; Wang, C.; Cheng, M.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Pan, P.; Che, J. Renewable marine polysaccharides for microenvironment-responsive wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neamtu, B.; Barbu, A.; Negrea, M.O.; Berghea-Neamțu, C.Ș.; Popescu, D.; Zăhan, M.; Mireșan, V. Carrageenan-based compounds as wound healing materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryukov, B.G.; Besednova, N.N.; Kuznetsova, T.A.; Zaporozhets, T.S.; Ermakova, S.P.; Zvyagintseva, T.N.; Chingizova, E.A.; Gazha, A.K.; Smolina, T.P. Sulfated polysaccharides from marine algae as a basis of modern biotechnologies for creating wound dressings: Current achievements and future prospects. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Jiao, H.; Sun, J.; Okoye, C.O.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J. Structure-activity relationships of bioactive polysaccharides extracted from macroalgae towards biomedical application: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 324, 121533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Quan, L.; Ao, Q. Characteristics of marine biomaterials and their applications in biomedicine. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, I.; Dheer, D.; Nagpal, M.; Kumar, P.; Venkatesh, D.N.; Puri, V.; Singh, I. A propitious role of marine sourced polysaccharides: Drug delivery and biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 308, 120448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliou, K.; Kikionis, S.; Ioannou, E.; Roussis, V. Marine biopolymers as bioactive functional ingredients of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitseva, O.O.; Sergushkina, M.I.; Khudyakov, A.N.; Polezhaeva, T.V.; Solomina, O.N. Seaweed sulfated polysaccharides and their medicinal properties. Algal Res. 2022, 68, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.-c.; Qin, W.; Lei, C.; Li, Q.-h.; Meng, M.; Fang, M.; Song, W.; Chen, J.-h.; Tay, F.; Niu, L.-n. Biomaterials from the sea: Future building blocks for biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4255–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Marine seaweed polysaccharides-based engineered cues for the modern biomedical sector. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S. Therapeutic importance of sulfated polysaccharides from seaweeds: updating the recent findings. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, D.; Garg, Y.; Mahmood, S.; Chopra, S.; Bhatia, A. Marine-derived polysaccharides and their therapeutic potential in wound healing application - A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 12731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidgell, J.T.; Magnusson, M.; de Nys, R.; Glasson, C.R.K. Ulvan: A systematic review of extraction, composition and function. Algal. Res. 2019, 39, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziveleka, L.-A.; Ioannou, E.; Roussis, V. Ulvan, a bioactive marine sulphated polysaccharide as a key constituent of hybrid biomaterials: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 218, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulastri, E.; Lesmana, R.; Zubair, S.; Elamin, K.M.; Wathoni, N.A. A comprehensive review on ulvan based hydrogel and its biomedical applications. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 69, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikionis, S.; Ioannou, E.; Aggelidou, E.; Tziveleka, L.-A.; Demiri, E.; Bakopoulou, A.; Zinelis, S.; Kritis, A.; Roussis, V. The Marine polysaccharide ulvan confers potent osteoinductive capacity to PCL-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziveleka, L.-A.; Sapalidis, A.; Kikionis, S.; Aggelidou, E.; Demiri, E.; Kritis, A.; Ioannou, E.; Roussis, V. Hybrid sponge-like scaffolds based on ulvan and gelatin: Design, characterization and evaluation of their potential use in bone tissue engineering. Materials 2020, 13, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Samal, S.K.; Bartoli, C.; Morelli, A.; Smet, P.F.; Dubruel, P.; Chiellini, F. Biofunctionalization of ulvan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 3211–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajaria, T.K.; Lakshmi, D.S.; Vasu, V.T.; Reddy, C.R.K. Fabrication of ulvan-based ionically cross-linked 3D-biocomposite: synthesis and characterization. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2022, 7, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruskiene, R.; Kavleiskaja, T.; Staneviciene, R.; Kikionis, S.; Ioannou, E.; Serviene, E.; Roussis, V.; Sereikaite, J. Nisin-loaded ulvan particles: Preparation and characterization. Foods 2021, 10, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, P.-A.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chang, J.-S.; Fu-Yin Hsu, F.-Y. Electrospun nanofiber composite mat based on ulvan for wound dressing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziveleka, L.-A.; Kikionis, S.; Karkatzoulis, L.; Bethanis, K.; Roussis, V.; Ioannou, E. Valorization of fish waste: Isolation and characterization of acid- and pepsin-soluble collagen from the scales of mediterranean fish and fabrication of collagen-based nanofibrous scaffolds. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toskas, G.; Hund, R.-D.; Laourine, E.; Cherif, C.; Smyrniotopoulos, V.; Roussis, V. Nanofibers based on polysaccharides from the green seaweed Ulva rigida. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yue, Z.; Winberg, P.C.; Lou, Y.-R.; Beirne, S.; Wallace, G.G. 3D bioprinting dermal-like structures using species-specific ulvan. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2424–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulastri, E.; Zubair, M.S.; Lesmana, R.; Mohammed, A.F.A.; Wathoni, N. Development and characterization of ulvan polysaccharides-based hydrogel films for potential wound dressing applications. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 4213–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toskas, G.; Heinemann, S.; Heinemann, C.; Cherif, C.; Hund, R.-D.; Roussis, V.; Hanke, T. Ulvan and ulvan/chitosan polyelectrolyte nanofibrous membranes as a potential substrate material for the cultivation of osteoblasts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.C.; Choi, H.; Kikionis, S.; Seo, J.; Youn, W.; Ioannou, E.; Han, S.Y.; Cho, H.; Roussis, V.; Choi, I.S. Fabrication and characterization of neurocompatible ulvan-based layer-by-layer films. Langmuir 2020, 36, 11610–11617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziveleka, L.-A.; Pippa, N.; Georgantea, P.; Ioannou, E.; Demetzos, C.; Roussis, V. Marine sulfated polysaccharides as versatile polyelectrolytes for the development of drug delivery nanoplatforms: Complexation of ulvan with lysozyme. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolean, I.; Coman, S.M.; Bucur, C.; Teodorescu, C.; Kikionis, S.; Ioannou, E.; Roussis, V.; Primo, A.; Garcia, H.; Parvulescu, V.I. Catalytic transformation of themarine polysaccharide ulvan into rare sugars, tartaric and succinic acids. Catal. Today 2022, 383, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.M.L.; Carvalho Júnior, A.R.; Vale de Macedo, G.H.R.; Chagas, V.L.; Silva, L.d.S.; Cutrim, B.d.S.; Santos, D.M.; Soares, B.L.L.; Zagmignan, A.; de Miranda, R.d.C.M.; et al. Polysaccharide-based formulations for healing of skin-related wound infections: Lessons from animal models and clinical trials. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayakumar, S.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. Biological activities of carrageenan from red algae: a mini review. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 10, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Esmkhani, M.; Zallaghi, M. Nezafat, Z.; Javanshir, S. Biomedical and environmental applications of carrageenan-based hydrogels: A review. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 1679–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A; Ahmed, S. Carrageenans: structure, properties and applications. InMarine Polysaccharides. Ahmed, S., Soundararajan, A., Eds.; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2018; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zia,K. M.;Tabasum,S.;Nasif,M.;Sultan,N.;Aslam,N.;Noreen,A.;Zuber M. A review on synthesis, properties and applications of natural polymer based carrageenan blends and composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, V.L.; Kawano, D.F.; da Silva Jr, D.B.; Carvalho, I. Carrageenans: Biological properties, chemical modifications and structural analysis–A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Ki, J.-S. Biological activity of algal derived carrageenan: A comprehensive review in light of human health and disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Quito, E.-M.; Ruiz-Caro, R.; Veiga, M.-D. Carrageenan: Drug delivery systems and other biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikionis, S.; Iliou, K.; Karra, A.G.; Polychronis, G.; Choinopoulos, I.; Iatrou, H.; Eliades, G.; Kitraki, E.; Tseti, I.; Zinelis, S.; et al. Development of bi- and tri-Layer nanofibrous membranes based on the sulfated polysaccharide carrageenan for periodontal tissue regeneration. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yegappan, R.; Selvaprithiviraj,V. ; Amirthalingam,S.; Jayakumar, R. Carrageenan based hydrogels for drug delivery, tissue engineering and wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, L.; Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Carrageenan-based functional hydrogel film reinforced with sulfur nanoparticles and grapefruit seed extract for wound healing application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 224, 115191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, T.; Sohail, M.; Minhas, M.U.; Ahmed Shah, S.; Jabeen, N.; Khan, S.; Hussain, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Kousar, M.; Rashid, H. Self-crosslinked chitosan/κ-carrageenan-based biomimetic membranes to combat diabetic burn wound infections. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 197, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditta, L.A.; Rao, E.; Provenzano, F.; Sánchez, J.L.; Santonocito, R.; Passantino, R.; Costa, M.A.; Sabatino, M.A.; Dispenza, C.; Giacomazza, D.; et al. Agarose/κ-carrageenan-based hydrogel film enriched with natural plant extracts for the treatment of cutaneous wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2818–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Mesquita, J.F. Population studies and carrageenan properties of Chondracanthus teedei var. (lusitanicus Gigartinaceae,Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2004, 16, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Diaz, F.; Aguilar-Rosas, R.; Aguilar-Rosas, L.E. Infrared analysis of eleven carrageenophytes from Baja California, Mexico. Hydrobiologia 1990, 204, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Amado, A.M.; Critchley, A.T.; van de Velde, F.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Identification of selected seaweed polysaccharides (phycocolloids) by vibrational spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR and FT-Raman). Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terezaki, A.; Kikionis, S.; Ioannou, E.; Sfiniadakis, I.; Tziveleka, L.-A.; Vitsos, A.; Roussis, V.; Rallis, M. Ulvan/gelatin-based nanofibrous patches as a promising treatment for burn wounds. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 74, 103535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanizaki, H.; Tanioka, M.; Yamashita, Y.; Hayashi, N. Quantitative evaluation of atrophic acne scars using 3D image analysis with reflected LED Light. Skin Res. Technol. 2020, 26, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastassopoulou, J.; Mamarelis, I.; Theophanides, T. Study of the development of carotid artery atherosclerosis upon oxidative stress using infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. OBM Geriatr. 2021, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassopoulou, J.; Kyriakidou, M.; Malesiou, E.; Rallis, M.; Theophanides, T. Infrared and raman spectroscopic studies of molecular disorders in skin cancer. In Vivo 2019, 33, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biranje, S.S.; Madiwale, P.V.; Patankar, K.C.; Chhabra, R.; Bangde, P.; Dandekar, P.; Adivarekar, R.V. Cytotoxicity and hemostatic activity of chitosan/carrageenan composite wound healing dressing for traumatic hemorrhage. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 239, 116106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, D.; Alcover, M.M.; Sessa, M.; Halbaut, L.; Guillén, C.; Boix-Montañés, A.; Fisa, R.; Calpena-Campmany, A.C.; Riera, C.; Sosa, L. Topical amphotericin B semisolid dosage form for cutaneous leishmaniasis: Physicochemical characterization, ex vivo skin permeation and biological activity. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mice classification | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Control | no treatment |

| Vehicle | Pure gel with the excipients (gel with PIL) |

| Ulvan 1.5% | 1.5% ulvan gel |

| Ulvan 5% | 5% ulvan gel |

| Ulvan 10% | 10% ulvan gel |

| Carrageenan 1.5% | 1.5% carrageenan gel |

| Carrageenan 5% | 5% carrageenan gel |

| Carrageenan 10% | 10% carrageenan gel |

| absence | mild | moderate | heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Oedema | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Hyperkeratosis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Wound thickness | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Ulceration | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Necrosis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Parakeratosis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Day 1–Day 15 | Day 15–Day 26 | |

|---|---|---|

| Control Vehicle Ulvan 1.5% Ulvan 5% Ulvan 10% Carrageenan 1.5% Carrageenan 5% Carrageenan 10% |

Y = -13.44*X + 274.8 | Y = -4.574*X + 112.1 |

| Y = -12.83*X + 286.8 | Y = -5.839*X + 140.6 | |

| Y = -13.76*X + 293.0 | Y = -5.841*X + 140.9 | |

| Y = -13.51*X + 281.8 | Y = -4.301*X + 101.5 | |

| Y = -12.06*X + 283.6 | Y = -6.215*X + 148.8 | |

| Y = -14.20*X + 288.3 | Y = -3.866*X + 92.23 | |

| Y = -12.23*X + 276.3 | Y = -5.588*X + 132.6 | |

| Y = -15.59*X + 271.6 | Y = -2.656*X + 62.78 |

| Treatment | Inf | Oed | HPKe | WTh | Ulce&Ne | PKe | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 12.0 |

| Vehicle | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.7 | 12.4 |

| Ulvan 1.5% | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 9.2 |

| Ulvan 5% | 1.7 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | 6.4 |

| Ulvan 10% | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | 8.7 |

| Carrageenan 1.5% | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | 10.0 |

| Carrageenan 5% | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 12.0 |

| Carrageenan 10% | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 4.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).