1. Introduction

Sustainability as a hybrid concept has had a crucial place in public and political agendas, since well before the reports

Our Common Future in 1987 [

1] and

Agenda 21 in 1992 [

2]. As per the United Nations’ Brundtland report, sustainability involves “meet[ing] the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to satisfy their own needs” [

1]. UNESCO (2005) defines three sustainability dimensions – environmental, social, and economic. This focus reflects that education has considerable potential to facilitate changes in attitudes, values and behaviours from generation to generation to enable sustainability to become more embedded within society.

Sustainability is gradually becoming an important aspect at all levels of education. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) was promoted in the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development [UNDESD] (2005–2014) [

3], following the UNESCO Global Action Programme for ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) (2015–2019) [

4] and then the ‘ESD for 2030’ framework from 2020 to 2030 [

5]. Over the past two decades, there have been calls to integrate sustainability into the curriculum: “all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development” (target 4.7, [

5] (p. 21)). By providing such a common ground, curricula can harmonise and integrate economic, social and environmental pillars in the minds of those who will soon be making pivotal decisions in their daily lives.

As sustainability is defined as a field beyond disciplinary anchoring by some researchers (e.g. [

6]), various subjects faced by school students might contribute to these three pillars in the following way: Environment – natural resources, climate change, rural development, sustainable urbanisation, disaster prevention and mitigation; Society – human rights, gender equity, peace and human security, health, HIV/ AIDS, governance, cultural diversity and inter-cultural understanding; Economy – poverty reduction, corporate responsibility and the market economy [

7].

School education can act as a catalyst for change through the curriculum, student-centred teaching methods, future-oriented thinking, higher-order thinking skills, critical thinking, interdisciplinarity, and linking local and global issues. According to [

8], the current generation of school students is the first to have to deal with global socio-economic, political and demographic realities. This viewpoint ties our local, everyday actions to global events, necessitating the development of a global awareness to influence change from private to general and address global challenges in a sustainable way.

Education for sustainable development – at the school level and in further and higher education – is aimed at educating individuals in accordance with sustainable development principles such as knowledge, attitudes, value, and behaviour through programmes that address environmental, economic and social issues [

9]. The Rio+20 Conference reaffirmed that universal access to primary education and quality education at all levels are “essential condition for achieving sustainable development” [

9] (p. 59). However, these efforts do not as yet seem to have catalysed the necessary changes to meet today’s increasingly complex problems [

10,

11].

The role of school education has also been emphasised by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs as being critical for ensuring sustainable development and improving the capacity of people to address environmental and developmental issues. In addition to that, both formal and non-formal education, for both children and adults, play crucial roles in altering individuals' attitudes, enabling them to evaluate and tackle their sustainable development concerns. Furthermore, it is commonly accepted that school education is crucial for attaining environmental and ethical consciousness, values, attitudes, skills and conduct that align with sustainable development, as well as facilitating effective public participation in decision-making by helping to ensure that the next generation of adults are informed about relevant issues and able to discuss these issues with their fellow citizens. The standards include, to give just one example, that “each practitioner [likely refers to individuals who are actively involved in the field of education, particularly those who work directly with students in schools e.g. teachers, school administrators, educational psychologists, counselors] school and education leader should demonstrate learning for sustainability through their practice” [

12].

Climate change is one of the critical goals under the Sustainable Development Agenda. According to the data from the Office for National Statistics collected in September-October 2022: “Around three in four adults (74%) in Great Britain reported feeling (very or somewhat) worried about climate change”, the second biggest concern, behind the rising cost of living (79%) [

13]. However, the voices of children and young people are largely absent from climate change coverage [

14]. On that point, in highlighting one of the greatest public policy issues of our time, one that challenges countries across the world, in a Policy Paper published in 2023, the Secretary of State for Education in England explained that:

The challenge of climate change is formidable. For children and young people to meet it with determination, and not with despair, we must offer them not just truth, but also hope. Learners need to know the truth about climate change – through knowledge-rich education. They must also be given the hope that they can be agents of change, through hands-on activity and, as they progress, through guidance and programmes allowing them to pursue a green career pathway in their chosen field. [

15]

At present, inspection of the National Curriculum in England shows that such views are not reflected in it. It remains to be seen when the National Curriculum is next revised – as a date as yet unspecified – whether such views are embedded in official discourse.

In common with a number of other countries (e.g., Sweden, Japan, Singapore and Turkey), England has had, since 1989, a statutory National Curriculum, though an increasing proportion of schools are exempted from it (e.g., because they are independent – i.e., fee-paying – or because they are classified as ‘academies’). The National Curriculum in England delineates the programmes of study and attainment targets for each school subject across all four compulsory key stages (ages 5-7, 7-11, 11-14, 14-16). The National Curriculum for England stipulates that:

All schools should make provision for personal, social, health and economic education, drawing on good practice. Schools are also free to include other subjects or topics of their choice in planning and designing their own programme of education. [

16] (2.5)

An increasing proportion of schools (independent schools and those that are Academies or Free Schools) sit outside the formal requirements of the National Curriculum but a school’s curriculum in England is not entirely determined by the National Curriculum, even for those schools subject to the National Curriculum. From September 2012, all schools have been required to publish their school curriculum by subject and academic year online [

16] (2.4). That makes them more open to scrutiny, in this case, in relation to how they address sustainability.

Such scritiny is becoming increasingly important as, in the last two decades or so, sustainability science, as a transdisciplinary domain, has offered a rich environment for crafting alternative paradigms that are more effective for tackling intricate sustainability issues [

17]. This study looks at the impact of this sustainability science in school curricula mainly based on the investigation of the pillars of sustainability – environment, economy, society – through the lenses of science communication and transformation theory.

1.1. Transformation Theory

Transformation theory, also referred to as transformative learning theory, is a learning theory drawn from the field of education specifically and the social sciences more generally. It:

(...) deals with how individuals may be empowered to learn to free themselves from unexamined ways of thinking that impede effective judgment and action. It also envisions an ideal society composed of communities of educated learners engaged in a continuing collaborative inquiry to determine the truth or arrive at a tentative best judgment about alternative beliefs. Such a community is cemented by empathic solidarity, committed to the social and political practice of participatory democracy, informed through critical reflection and would collectively take reflective action, when necessary, to assure that social systems and local institutions, organizations and their practices are responsive to the human needs of those they service. [

18]

This vision for transformation refers to the role of school education, along with other forms of education, as a catalyst for change. In the field of school education, there is no doubt that the environmental crisis and other existential threats (e.g. those from the nuclear industry, pandemics and AI [

19]), require changes in the way many people live, think and act. Responding to this call – within the frame of reference of transformation theory – will require change in individual lives and through collective action that recognises unsustainability, strives for equitable societies, and creates sustainable conditions. This shift will not be easy, as discussed by [

20]: “This change is perhaps already in the air, however, faintly. But our tradition, education, current activities, and interests will make the transformation embattled and slow” (p. 195). At the same time, repeated and widespread adverse events, like those arising from pandemics, climate change and biodiversity loss, force many people to reconsider their lives, thoughts and actions. This kind of change can occur when transformative learning is effective; it involves shifting frames of reference through critical observations of both habits and perspectives [

18]. Our argument is that transformative learning, often seen as being applicable to adults and young adults, is also applicable to children of primary age and may be needed, given the current climate change, biodiversity and sustainability crisis.

1.2. Science Communication

Integrating a sustainability lens into science communication can be seen as one avenue to being transformative. Science communication can be defined as the skilful use of various tools, media, activities and dialogue to elicit one or more of the personal responses to science: awareness, enjoyment, interest, opinions and understanding [

21]. Since the 1990s, science communication has emerged as a multidisciplinary field connected to communication, education, the natural sciences, the social sciences and various other areas. It can be defined as the production, circulation and reliable utilisation of knowledge among scientists, society, policymakers, industry and other stakeholders [

22]. Over the last 30 years, science communication activities have encompassed a range of approaches [

22], from top-down, one-way/unidirectional models highlighting a deficit in knowledge and means to boost understanding to interactive public engagement and public participation models. However, in an age of misinformation, it is arguable how successfully institutional attempts at science communication handle the issues [

23] that capture the attention of various publics, e.g., COVID-19, climate change, the theory of evolution. It has been proposed that the objectives of science communication can be classified into at least six categories: securing the accountability and legitimacy of publicly funded science; enabling informed decisions by laypeople and policymakers in today's technologically driven societies; bolstering democracy by empowering citizens; offering access to the aesthetic aspects of science as a cultural element; serving promotional goals, such as those seen in ‘university PR’; and fulfilling an economic role by attracting individuals to scientific careers or preparing a market foundation for technological innovations [

24].

Via these definitions of science communication, one can see its relevance to the efforts of scientists highlighting the threats of anthropogenic climate change, which they have been attempting to do since at least 1957 [

25]. This extended timeline is not a source of pride, and if it requires such a prolonged effort to engage public attention in the next crucial environmental phase, we are likely to encounter significant challenges, such as Pacific Islands and many other coastal communities facing inundation from rising sea levels. For this reason, the efficacy of scientific communication can be questioned in terms of its functions in such circumstances as the climate crisis, vaccine rejection and the problem of access to clean water in a number of countries. Amidst such challenges, it is generally held that science communication is important for fostering informed public discourse, influencing policy decisions, and addressing global issues collaboratively.

Despite their differences, there is considerable similarity between conducting science communication successfully and implementing effective educational strategies in schools and other settings. Both disciplines, education and science communication, share a number of points: tailoring the message to the audience; building trust with the audience; initiating an interactive dialogue rather than a one-way monologue; and seeking in what one communicates or teaches to enhance awareness, enjoyment, understanding, the formation of valid opinions and interest.

From these two perspectives – transformation theory and science communication – we recognised an opportunity to examine the effectiveness of curriculum decisions and the adoption of a sustainability frame of reference across classroom teachers, headteachers and students. We attempt to address this issue to answer the following research questions through examination of actors and activities in two primary eco-schools in England:

What are primary teachers’ and fourth and fifth grade students’ knowledge and how do they perceive sustainability and climate change?

What kind of features do participant schools have with regard to the environmental, social, economic and educational dimensions of sustainable development oriented education?

From the participants’ perspectives, what are the challenges and opportunities of their schools by having an orientation toward sustainability?

What information sources do the teachers and fourth and fifth grade students use in learning about sustainability issues?

How is environmental and sustainability education enacted and experienced in primary eco-schools from the perspectives of classroom teachers, headteachers and fourth and fifth grade students?

Investigation of these questions, from the conceptual reference points just explained, reveals ongoing challenges, where integration of sustainability into the curriculum was limited and problematic.

3. Results

“So, there's something about, you're not necessarily doing it for yourself, but you're doing it for the greater good.” (HT1)

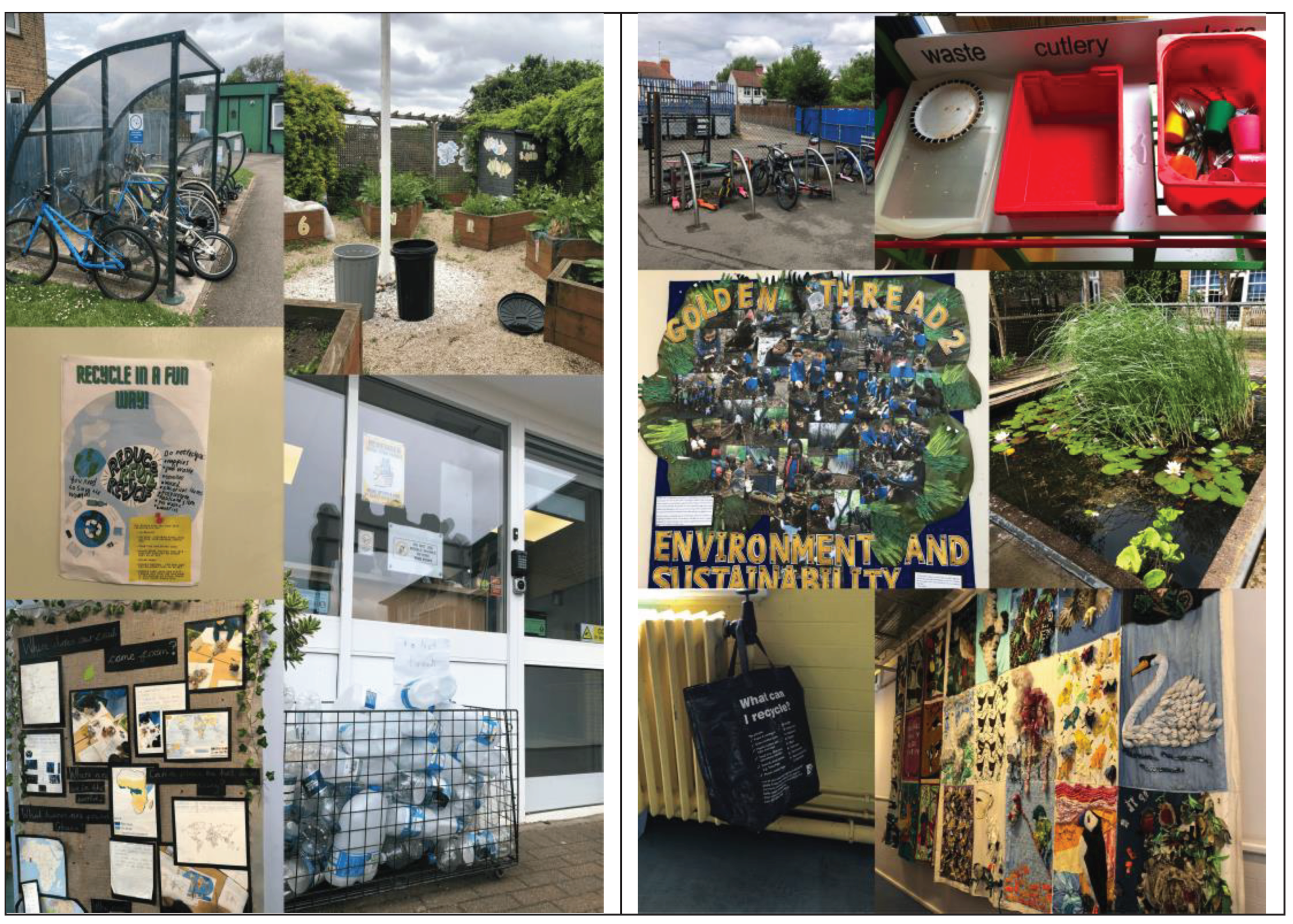

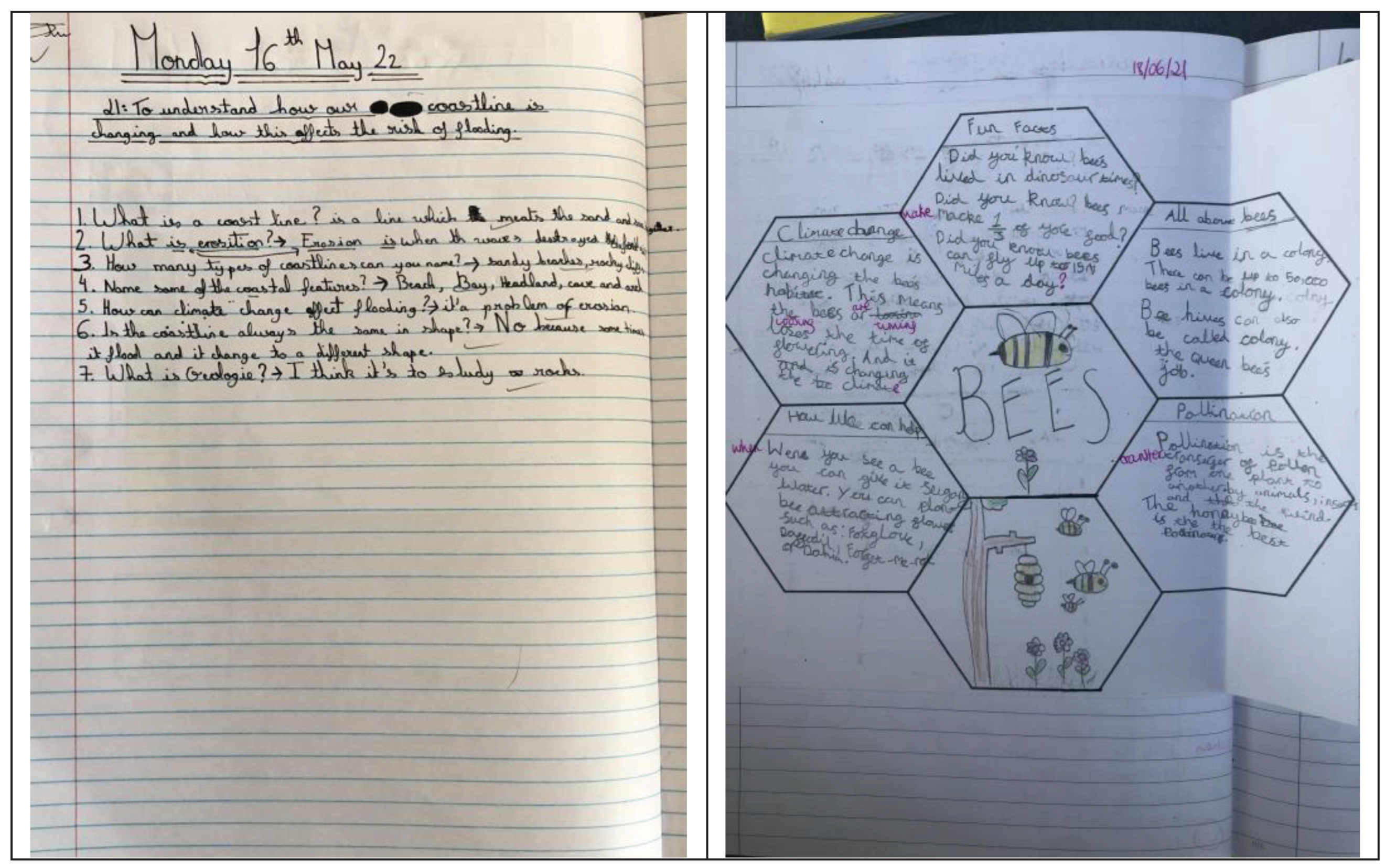

We organise our findings by our five research questions. The richest data came from the interviews, but we also use data from our observations, and the student exercise books (e.g.,

Figure 2). Of the four dimensions of sustainability, the most in evidence in each of the schools were the environmental (e.g. climate change, water scarcity) and economic (e.g. consumption, renewable energies) dimensions. When quotations are given, no attempt has been made to ‘tidy up’ the language used.

3.1. Teachers’ and Fourth and Fifth Grade Students’ Knowledge and their Perceptions of Sustainability and Climate Change

Most participants rated their personal understanding of sustainability as “reasonable” or “good”. Environmental problems like climate change and pollution were conceptualized to be the consequence of decisions and actions by humans:

(…) the issue is, is it’s the, the impact we’ve had, so the global warming side of things, because of our emissions and our actions. And over such a tiny period of time. (T5)

For the participants in this study, the most commonly cited environmental problems facing the world today were: pollution (HT1, T1, T3, S3-Yr4-Sch1, S4-Yr1-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch1); floods (S4-Yr5-Sch1); global warming (HT1, HT2, T1, T2, T3, S5-Yr5-Sch1); climate change (S3-Y4-Sch1, S3-Yr5-Sch1); energy (ET1, ST1); ozone layer (S3, S5-Yr5-Sch1); carbon footprint (ST1); consumerism (T2); deforestation (T1, S2-Yr4-Sch1, S6-Yr5-Sch2); overpopulation (T1); food waste (HT1, S3-Yr4-Sch1); and toxicity (HT2).

Both students and teachers invariably stated that students find sustainability to be important, while students reported that their teachers and parents also value environmental issues:

I think that it really matters. Some people do it [give importance to a sustainable life], but we need more people around the world doing it (S4, Yr5, Sch2)

We can watch David Attenborough. And then, my parents tell me about (S3, Yr4, Sch1)

(…) And what we've got is significant, and irreversible damage being done to people's way of living in terms of their ability to perceive themselves as individuals and countries to sustain themselves. So I think what is going to inevitably happen is that there will be a rush for resources. And those resources permit even more finite, what will probably happen is there'll be huge pressure on migration northwards towards more temperate environments. (HT2, Sch2)

For example, participants agreed that human activities affected the environment: “the way we affect the environment is like, is good and bad at the same time” (S5-Yr 4-Sch1). S2-Yr4-Sch2 gave an example of the negative impact of people on the environment – the use of vehicles, instead of increasing the use of bicycles or walking.

In a dramatic reflection on the urgency of environmental action, HT1 articulated a pressing concern regarding the current trajectory of human impact on the planet. Delving into the insights derived from Griscom’s book [

32], the participant emphasized the approaching threat, cautioning that humanity stands on the brink of real danger: “Before we’re in real danger, if you read according to Griscom book, that would be you know, and we, the fact is that we are still burning fossil fuels, we are trying to get across to electric cars. And we’ve done sorry, I’m quite I’m sort of a bit of like, we’ve done so much damage. And it’s about educating the children about how not to continue that and what can change”. This statement encapsulates the essence of a broader narrative emerging from participants within the study – highlighting the need to instil environmental awareness in children and foster a collective commitment to mitigating the detrimental effects of past actions.

For most of the participants, families, governments and big companies (HT1) were seen to have the biggest roles in sustainability. According to the Year 4 student group interview, governments could allocate more funds to support the public and schools to be able to plant more trees in their gardens (S5), should prevent people from cutting down trees (S2) and add extra zones [the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) is a zone in certain areas of London, where vehicles need to meet strict emissions standards to enter without incurring a daily charge] as the cars are using too much fuel (S4).

Emphasising the role of the government in a similar vein, HT2 advocated a shift in the curriculum, urging governments to prioritise essential aspects over outdated learning approaches:

I think governments need to give schools resources. I think governments need to give schools time. I think governments need to take the pressure off from all the accountabilities that schools have so that schools have the space and energy and resources to develop the things that are really important. (…) Governments have a responsibility, I think, to do that, instead of what I think is quite an archaic and old-fashioned view of learning.

The Year 5 students at School 1 felt that governments could take more initiative on sustainability issues. Their recommendations ranged from advocating the construction of wind turbines to supporting the production of environmentally friendly vehicles. In a parallel vein, the Year 4 students at School 2 demonstrated a proactive approach to environmental stewardship within their school community: “teachers can give them extra time to pick up rubbish” (S6). The students, in the School Club called ‘Star Squad’ [an example of an eco-group, discussed below], engaged in weekly gatherings where they not only discussed environmental concerns but also took tangible actions. For instance, they dedicated time to picking up litter and went to the school allotment, actively clearing weeds and removing what they saw as other impediments, so as to contribute positively to the environment. This juxtaposition of perspectives and initiatives highlights the diversity of approaches within different school cohorts, collectively emphasising the importance of both advocating for systemic change and fostering hands-on, grassroots efforts for a sustainable future.

However, it was seen to be difficult to influence parents (HT1): “Parents don’t like to be told and how they should do things. So, I think [it’s] requesting parents say not to use the car to drop their children off to school is would be very difficult. (…) Our influence on them is very limited”. On the other hand, for ST1: “I think some is better than none. But the thing is, you can launch these things. And I think if you if you infuse the children, if you encourage the children and work towards something, I think the families almost have to come along with it. Even if they don’t really want to. And if you put positive reasons to support their child in it, I think they would do it”.

The interviews showed that many participants take their own personal measures for a sustainable world. These measures include using their own plastic bags, recycling, growing plants in their gardens, using their own thermoses in cafes and avoiding the use of disposable plastic straws. The adoption of such practices, even if they might be seen as somewhat modest, underscores a commitment to sustainability at an individual level.

Within the realm of personal understandings of sustainability, the reflections of one participant shed light on the interconnectedness of ethical considerations and environmental awareness. As articulated by the speaker, the analogy of an elephant confined within the limited space of a zoo prompts contemplation on the ethical implications of human actions towards animals:

Like you can’t just have an elephant in a zoo. Because the elephant, there’s not enough space for a zoo. And you can’t have and then illegal to like, hurt like, so. Why is it so it’s illegal to kill someone if they’re human, but it’s not illegal to hunt animals? So, I think they should put like more laws to stop like hunting animals and stuff like that. (S3-Yr5-Sch2)

The student here questions the legality of hunting non-human animals in contrast to the stringent laws protecting human life, highlighting a perceived inconsistency in our societal values. The natural tendency for many young children to feel empathy for non-human animals could be harnessed when teaching about issues of sustainability that go beyond human considerations.

3.2. The Features of the Participant Schools with Regard to the Environmental, Social, Economic and Educational Dimensions of Sustainability

The distinct advantage of being designated as eco-schools appeared to play a pivotal role in shaping the sustainability initiatives of both schools. However, challenges in implementing efficient recycling practices surfaced, revealing the complexities associated with waste management within the school environment, as elucidated by HT1:

You know, proper efficient recycling, which, you know, I don’t think happens, I think it’s quite difficult when you’ve got a lot of people coming into the school. So, we’re trying to recycle, we’ve only got one recycling bin, but we’ve got five general wastes. So, when the recycling bin is full, you know, the recycling such that it’s tipped into the [waste]; the cleaners are really bad at recycling.

The struggles with recycling infrastructure and custodial practices highlighted the need for enhanced waste management strategies. In addressing environmental concerns, both schools actively promoted sustainable commuting through organised “scoot day[s]” (where students scooted to schools) and participated in national competitions, emphasising the commitment to reducing car usage. HT1 cited an ongoing challenge of sustaining these initiatives, underscoring the balance between belief in their importance and the practical difficulty of maintaining momentum. The integration of sustainable practices, such as growing food for the school’s kitchen, demonstrated a commitment to environmentally conscious choices, as voiced by HT1. However, the inherent challenge of sustaining these initiatives over time, as expressed by HT1, emphasized the need for continuous dedication: “I think the strength side that we believe in it, and we want to do things, I think the weakness is keeping it going”.

The collaborative approach to sustainability was evident in teachers’ emphasis on developing projects with families and in teachers’ focus on recycling practices at School 1. These initiatives showcased a commitment to engaging the broader community and addressing environmental concerns collectively. In essence, while the advantage of being eco-schools laid the groundwork, the challenges highlighted by participants underscored the ongoing dedication required to foster a lasting culture of sustainability within and beyond the school community.

3.3. Perceived Challenges and Opportunities in the Schools as a Consequence of their Focus on Sustainability

The findings from the discussions with key stakeholders shed light on both challenges and opportunities in implementing environmental education within the school setting [

33]. The identified weaknesses primarily revolve around time constraints, the perceived additional workload for teachers, and budget limitations affecting the school’s environmental impact. HT2 candidly acknowledged the struggle to allocate adequate time and space for environmental education, emphasising the need for a fundamental shift in how these initiatives are integrated into the daily operations of the school.

Financial constraints emerge as a significant hurdle, often leading School 2 to opt for the most cost-effective solutions: “We don’t have the money to spend on improving our environmental impact. Because we go for that we have to go for the cheapest or most cost-effective solutions and options.” (HT2). This compromise, while understandable, is recognised as potentially compromising the integrity of the school’s commitment to environmental stewardship. The desire for improvement is palpable, yet the practical challenges in allocating resources persist.

However, amidst these challenges, there are several promising opportunities that participants recognise can help propel both schools towards a more sustainable future. HT1 suggested the collection of rainwater, presenting a tangible step towards resource conservation. Additionally, the initiative to grow food on-site, incorporating it into the school’s kitchen, stands out as a more effective approach to fostering a deeper connection between students and nature, as stated by T2: “Growing your own food, and then that food is used to cook in the kitchen. And so, not only is that I mean, they still need to buy food, and but what the benefit of that would be, is children then see the direct relationship between planting, growing, cooking and eating.”. This initiative, if implemented, not only promotes sustainability but also cultivates a mindset where students understand the lifecycle of food from planting to consumption.

The challenges identified include concerns about recycling, alignment with the National Curriculum, and financial limitations. These challenges, when approached strategically, can become stepping stones for positive change. For instance, addressing recycling challenges can lead to improved waste management practices, contributing to a cleaner environment within the school premises. Comparably, the ‘walk to school’ programme at School 2, encouraging parents and children to commute sustainably, showcases a commendable effort to instil eco-conscious habits from an early age. As one teacher put it: “Like one thing they do reach the parents like so the walk to school thing is where we encourage like parents and children to walk to school and we track it we so there is that involvement.” (T2). This sort of measure can be seen as a proactive step towards integrating environmental education more effectively into the community and the curriculum.

3.4. Information Sources Used in Learning about Sustainability Issues

Participants in the study employed a diverse range of information sources to attempt to deepen their understanding of sustainability issues. Social media was seen as a dynamic platform, with HT1, T2 and S4 from School 1 highlighting its role in sharing and accessing information within a community context. For adults, communication with other adults served as an invaluable source, providing real-world insights and diverse perspectives (e.g. HT1, T2, T5). School education, both in terms of climate change curriculum and general sustainability-focused education, remained a cornerstone, according to participants such as HT1, S3-Yr4-Sch1, S3-Yr5-Sch2, and S3-Yr5-Sch1. Television, especially David Attenborough’s programmes, played a significant role, engaging HT1, HT2, S3-Yr4-Sch1 and S3-Yr5-Sch1. Participants like T2 drew on a mix of podcasts, books (including Griscom’s work) and newspapers to glean information, highlighting the importance of varied literary and auditory sources. YouTube was a visual medium for learning, attracting such participants as S3-Yr4-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch2 and S5-Yr5-Sch1. T5 actively used YouTube to upload videos on environmental issues. Parents, particularly those with journalistic backgrounds like HT2, significantly influenced other participants’ knowledge acquisition by talking with them (e.g., S4-Yr4-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch1, S3-Yr4-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch2, S3-Yr 5-Sch2 and S2-Yr 5-Sch2).

Interactions with friends played a notable role, as seen with participants S2-Yr 4-Sch1 and S2-Yr 5-Sch2, where informal discussions contributed to a collective understanding of environmental concerns. Books emerged as resources for acquiring in-depth knowledge, with participants S4-Yr4-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch1, S2-Yr 5-Sch2, and S3-Yr 5-Sch2 turning to them to delve into various aspects of sustainability. Eco-groups within schools, involving participants like S5-Yr5-Sch1, S2-Yr4-Sch2 and S6-Yr5-Sch1, provided a platform that interviewees suggested offered collaborative learning and hands-on experiences, fostering a sense of shared responsibility toward environmental stewardship. Newspapers, a traditional but still relevant source, played a role in helping participants such as S3-Yr5-Sch1 and HT2 to stay informed about current sustainability issues.

This tapestry of channels indicates the commitment of many of the participants to a deeper understanding of sustainability issues afforded though science communication.

3.5. How is Environmental and Sustainability Education Enacted and Experienced in Primary Eco-Schools

“And I think it’s possible to do that. It’s a combination of all those little bits, all those schools doing those little bits together that will help to add up to make some big impact.” (HT2)

The teacher and student perspectives on the integration of sustainability topics within educational programmes revealed important insights. Teachers generally expressed that sustainability issues should be embedded within the curriculum, even from Reception [the year before Year 1, so children are aged from four to five] (e.g., ET1). Participants generally agreed that geography and science are key subjects for integrating sustainability, although concerns about the depth and explicit coverage of the issue of sustainability persisted. Sustainability was also seen to fit into the Personal, Social, Health and Emotional (PSHE) curriculum. While the science curriculum was acknowledged as addressing sustainability, some participants, particularly T3, expressed concerns about its outdated nature and the need for it to change in the light of recent technological advancements:

(…) the science curriculum does talk about sustainability, but not as much as probably could. I think it is outdated. I think it needs to change now because you know, technology is changing. (T3)

I don’t think it is in the science curriculum. It should be. (…) it needs to be more in-depth in geography. (T4)

Teachers, including T4, highlighted the vague and insufficiently in-depth nature of the geography curriculum, emphasising the importance of explicit coverage on critical issues like climate change:

I feel like the geography curriculum is very, at the moment, quite vague. It is not very in-depth as it could be. They say like, I have bits and bobs here and there, but I don’t think it’s anything explicit. I think there should be a whole thing about climate change. (T4)

Students, according to T3, benefit from open-ended projects, fostering a deeper understanding of sustainability issues. Despite efforts in curriculum design to reflect community values and create responsible citizens, a gap was described in embodying sustainability ideals during curriculum delivery.

In the exploration of sustainability education within primary eco-schools’ curricula, the insights from HT2 provided a foundational perspective. HT2 emphasised the fundamental role of sustainability in the school’s vision, rooted in idealism and morality. HT2 articulated four elements – celebrating diversity, being upstanding and activists, living by the school’s values, and embracing environmental responsibility and sustainability – that were deemed crucial for enabling children’s future success. Sustainability was recognised as integral to the school’s purpose.

HT2 further illustrated the practical aspects of sustainability within the school, focusing on issues such as plastic in oceans and temperature change. The necessity of incorporating sustainability into the curriculum was highlighted, and HT2 acknowledged the challenges of implementing meaningful change, attributing these difficulties to financial constraints and the prioritisation of short-term outcomes. Despite these challenges, HT2 envisioned high-profile initiatives, such as creating a sensory garden and enhancing a local park’s environmental sustainability, as opportunities for positive impact:

I want the geography subject leader and science subject leader to really make sure we showcase those where we are doing our sustainability work. I want, so we’ve got two projects next year; one is here, which is the sensory garden, and one is down the road. There’s a small park called (…) . And they want to make that park a better environment, both from an environmental perspective, but also from a, yeah, to make it a more sustainable place. And so we’re going to be involved in those so I want to try to get the school involved in those things (…) because lots of our children will use that park I want us, our children, to be part of that. (…) I think we should get involved in because that’s our local space, that’s where we can have a positive environmental impact.

The commitment to showcasing sustainability efforts and involving students in meaningful projects can be seen to underscore a school-wide dedication to instilling environmental responsibility and sustainability in the school ethos.

When the teacher participants were asked, “In which educational programmes do you think sustainability topics can be more integrated?”, they mostly responded “geography” and “science”. However, the National Curriculum, which includes both geography and science, was criticised for having loose links to sustainability. Teachers, particularly T1, stressed the limitations imposed by the National Curriculum, citing a lack of adequate content on sustainability as a weakness. Environmental problems, notably climate change and pollution, were viewed by participants consequences of human decisions and actions, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive sustainability education from an early age.

The findings demonstrated a consensus among participants on the need for a more robust integration of sustainability topics in educational programmes, particularly within the National Curriculum. Teachers expressed a passion for meaningful sustainability lessons, emphasising the importance of nurturing children’s well-being in an interconnected world. However, challenges were seen to persist, including perceived inadequacies in the National Curriculum, indicating the necessity for policy changes and a more concerted effort to embed sustainability education into the core of primary education:

So, what can we do in education? I think first, it is like respecting the child. And I think education needs to slow down in order for that to happen. (T2)

I believe the problem starts with the National Curriculum. One of strengths about the sustainability in school is the passion and ability of teachers to teach meaningful lesson to the children by encouraging children to maintain or sustain their wellbeing first in an interconnected world. One of the weaknesses is that not enough content is included in the National Curriculum about the sustainability. (T1)

For HT1, the government sees sustainability as mainly schools’ responsibility:

I would say is that I feel the government’s answer to every problem is that schools should teach it. So, no matter what it is, so obesity, schools need to do with its money, sustainability, schools need to do (…) Every single problem in society, schools are told that they need to do with it (…) which is very overwhelming.

In contrast, HT2 referred to the crucial role of education as follows:

(…) they [students] are to be to celebrate the diversity and inclusivity of all people, races, genders, etc, to be upstanders and activists, to live by the school’s values, and to be environmentally responsible and sustainable, and live sustainably. Those are the four things that I think will enable our children to be successful in their futures. So, that sustainability part is fundamental to what I think this school is here for.

These problems can be seen to require different solutions. One of them was a revolutionary approach, as stated by HT2:

So, it needs people who are actual revolutionaries, I think, whether that be Extinction Rebellion, whether that be people protesting the British Grand Prix yesterday [3 July 2022], whether that be people like Greta Thunberg, but I actually think it’s going to be people that might now be considered on the fringe, and radical.

Both schools had eco-groups that included an eco-group leader and students from various years. An eco-committee was selected democratically from Years 3-6 at School 1 and Years 4-6 at School 2, which increased the confidence of those students who applied and were elected. Interviews with the eco-team leaders showed that a large number of students were involved in environmental research, which provided an opportunity for in-depth discussion within the eco-committees.

Teachers’ and students’ characteristics (experience, age, gender, field of study) did not seem to make significant differences to their responses. However, students from eco-teams were more knowledgeable and talked more about sustainability issues compared to their peers. Data gathered from interviews, observations and the class exercise books indicated that students seemed to have an enthusiasm and were aware of their responsibilities as ‘powerful agents of change’ with regard to sustainability and climate change issues. It was evident that students had learnt from their schools, families and the media about climate change.

In-class observations and interviews showed that both schools made connections with environmental issues in some curriculum areas, particularly geography, science and art. Overall, School 2 seemed to have a better dedication to environmental education with curriculum link evidence (e.g., a tree planting project) provided by the eco-team leader. As a final point, teachers in both schools expressed interest in expanding their knowledge as well as their students’ understandings of sustainability and climate change. In this context, teacher participants from both schools stated their interest in participating in in-service training programmes.

Discussion and Conclusion

The level of knowledge and meaningful discussions taking place among teachers, headteachers and the fourth and fifth graders in these schools on topics related to climate change and sustainability suggests how welcome these topics are to participants and the possible effectiveness of the teaching and engagement strategies. The proactive approach to education can be seen not only to enrich the learning environment but also equip students with what we perceived to be valuable insights into crucial global issues.

However, the results indicated that there is a tension between different understandings of sustainability. This tension often reflects the tension between maintaining existing socio-economic and political structures and embracing more transformative, holistic approaches to sustainability. Furthermore, an interdisciplinary approach to the topic can be understood to be one of the keys to successful, indeed transformational, learning, that is, treating it not as a separate subject to be taught on its own, such as ‘environmental education’ or only as part of the natural sciences, but rather as an integral part of every school subject’s curriculum and study plan.

Regarding school education, the following skills and characteristics of ESD learning methods outlined by [

34] were considered: student-centred teaching methods; future-oriented thinking; higher-order thinking skills; critical thinking; interdisciplinarity; and linking local and global issues. The Rio+20 Conference reaffirmed that universal access to primary education and quality education at all levels are “essential for achieving sustainable development.” (p.1). The key issue here is that the nature of sustainability issues seems to raise pedagogical issues in changing subject content and requires transformative approaches; this need can cause difficulties in schools that are subject to all sorts of practical constraints.

While challenges in time, National Curriculum requirements and budget constraints persist, the identified opportunities offer a roadmap for schools to enhance their environmental education initiatives. By strategically addressing challenges and capitalising on opportunities such as rainwater collection, sustainable food practices, travelling to and from school and community involvement, a school can pave the way for a more environmentally conscious and educationally enriching environment. The commitment to improvement, as voiced by HT2, provides a foundation for a sustainable and impactful educational journey.

The findings underscore a consensus among participants on the need for a more robust integration of sustainability topics in educational programmes, particularly within the National Curriculum. This would help provide more effective science communication and increase the likelihood of sustainability education resulting in transformative learning. Considering our observations and interview results, we have found gaps in the current sustainable education curricula in England. Specifically, a parallel result to [

35], teachers express a passion for meaningful sustainability lessons, emphasising the importance of nurturing children’s well-being in an interconnected world. However, they frequently lack the confidence, abilities, understanding and support to do so. In addition, teachers face some challenges including perceived inadequacies in the official curriculum, indicating the need for policy changes and a more concerted effort to embed sustainability education into the core of primary education.

Most of the teacher participants emphasised that the responsibility to deal with sustainability issues was the government’s but that the government did not seem to take communication of sustainability both in formal and informal ways seriously. In parallel with the argument in [

36], what is most needed is “concrete support that is close to teaching and the schools’ objectives” (p. 1). Such support is likely to be needed if more than a small proportion of schools are able to engage in teaching that enable effective transformation for students. Perhaps the most important manifestations of that support would be: (a) a requirement for sustainability to be embedded across the curriculum in primary schools, and not just in geography and science; (b) a lessening of other demands on teachers’ time; and (c) the provision of high-quality professional development for teachers, a point to which we return below.

Participants reported that they got their information about climate change and sustainability from a range of sources, including podcasts, books, newspapers and YouTube, underlining the varied media drawn on by the ‘learning community’ as a whole. The influence of parents on students’ knowledge acquisition is noteworthy, showcasing the more general impact of familial environments. Interactions with friends, informal discussions and eco-groups within schools all contribute to a collective understanding of environmental issues, emphasising the significance of social dynamics in knowledge exchange as also discussed by Illeris [

37]. According to community of practice theories of learning tend to suggest that learning does not have to reside in one individual. It can reside in the community, as a whole, likewise our data suggest that the community has a wide range of resources, but each individual does not (or not necessarily). Books (participants did not explicit the type of the book whether academic or non) remain resources for acquiring in-depth knowledge, with several participants turning to these to explore various facets of sustainability.

Eco-groups within schools emerged as a distinctive platform that makes a difference for collaborative learning and hands-on experiences, with evidence that they are fostering a sense of shared responsibility towards environmental stewardship. Those committee members would then be able to share their findings and views more widely with their classmates. These efforts are also important in terms of being consistent with the principles and processes of science communication.

Traditional sources like newspapers continue to play an important role for a number of our study’s participants, ensuring that they stay informed about current sustainability issues, though, of course, as with any source of ‘information’, newspapers have, at the very least, their own perspectives on sustainability and climate change issues (contrast, for example, the more eco-friendly [

38] with the more climate change sceptic [

39]). An optimistic interpretation is that the wide array of media used and accepted reflects the commitment of the community of participants to a well-rounded and extensive understanding of sustainability, which is consistent with recognition of the multifaceted nature of contemporary knowledge acquisition in this critical field.

This research is well-informed by, but also limited to, a study undertaken in two primary state eco-schools in London. The data for the study specifically concern the opinions of teachers, head teachers, eco-team leaders and fourth and fifth grade students, as well as observations made by the first author over a period of 14 weeks. Future research could complement this research by looking at primary schools that do not have a particular focus on sustainability and by looking at the situation in secondary (11-16 or 11-18 years) schools. It would also be valuable to gather data on the perceptions of parents and policy makers. These sorts of insights could confirm the extent to which key conclusions – e.g., about the challenges of sustaining sustainability activities – are widely experienced. That could highlight where policy changes or better resourcing should be committed.

Finally, this study indicates a need for high-quality teacher professional development courses on sustainability issues to be more widely available. If and when such courses are developed, there will be a need for them to be evaluated not only to determine their effectiveness, e.g., in fostering transformative learning, but so that future iterations of such courses can be improved.