1. Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) infection is a pandemic disaster. Up to 26% of infected patients require Intensive Care Unit (I.C.U.) treatment, out of whom 61% develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [

1,

2]. Once ARDS Covid-19 related (C-ARDS) with Hypoxemia has established, invasive therapy becomes indispensable [

3]. As such, inhaled Nitric Oxide (iNO) was tested as an alternative rescue solution for coronavirus disease [

4]. In 2004, during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) spread out, iNO was shown to improve the Ventilation/Perfusion (V/Q) ratio in infected patients [

5].

Nevertheless, a 2016 Cochrane Review does not recommend the routine use of iNO in patients with ARDS because its use could not improve the prognosis [

6]. Nowadays, the role of iNO in managing severe hypoxia due to COVID-19 infection is still a subject of debate. Despite lacking clinical data, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommends using iNO as a rescue therapy in patients with severe and persistent Hypoxemia [

3]. Indeed, not all patients are responders to iNO administration. The rates of response range between 25% and 65% across the studies [

7,

8]. Our research aimed to analyze the predictive value of response to iNO administration in patients with persistent severe hypoxia due to COVID-19 infection.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective, single-centre observational study conducted at Misericordia Hospital, representing the Covid-Hub of the whole province of Grosseto (250,000 inhabitants), Italy.

According to Berlin's definition [

9], ARDS was defined in all patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. In the case of Hypoxemia with Partial pressure of oxygen/Fraction of Inspired Oxygen ratio <150 mmHg (PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio), a multistep clinical approach (neuromuscular blockers and prone position) was performed, as recommended for ARDS management [

6]. If Hypoxemia with PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio < 150 mmHg persists, clinicians have considered administering iNO. For the survival analysis, we considered all the causes of death. We defined three death causes: Multiorgan Failure (M.O.F.) related to severe hypoxia; M.O.F. related to other reasons; Cardiac death when correlated with acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, or sudden death. The study included the analysis of consecutive critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection, as confirmed by severe acute respiratory syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV2) polymerase chain reaction on nasopharyngeal swab specimens, according to WHO guidance [

10], admitted to I.C.U. Inclusion criteria were: 1) adult age (≥18 years old); 2) severe Hypoxemia requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation; 3) persistent PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio <150 mmHg despite prone position (P.P.). The exclusion criteria were: 1) non-confirmed SARSCoV-2 infection; 2) L.V.E.F. <40% with or without moderate/severe mitral regurgitation on transthoracic echocardiographic assessment. Patients were divided into Group 1 = non-responders and Group 2 = responders. Demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical data were collected from anonymized electronic medical records at I.C.U. Admission, on the day (T0) immediately before each rescue therapy, was performed, 1 hour after the beginning (T1), and after discontinuation of treatment (T2). All clinical values, such as arterial blood gas and ventilation settings, were collected in the supine position over T0, T1, and T2. Between T0 and T1, the ventilatory setting and FiO

2 were not changed. A simplified method of calculating the mechanical power in Pressure Control proposed by Becher et al. and in Volume Control by Gattinoni et al. has been reported below [

11,

12]. Pulmonary involvement was assessed through the C.T. involvement score (CT-IS) based on the study model by Chung [

13]. The events were recorded during the entire duration of the I.C.U. Stay. In our centre, no patient withdrew from pharmacological or invasive treatments such as ventilation. Patients were sedated with propofol, remifentanil, and often midazolam if required, paralyzed with a continuous infusion of atracurium. They were ventilated in pressure or volume-controlled mode, aiming to maintain Plateau Pressure (Pplat) <28 cmH

2O, using a Tidal Volume (T.V.) of 4–8 mL/kg of predicted body weight. The decision to do any rescue therapy was related to the clinician’s evaluation and judgment. In our institution, iNO, such as rescue therapy, was considered when patients presented severe C-ARDS with PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio <150 mmHg for more than 6 hours with worsening clinical course and despite the prone position. Each pronation cycle was maintained for at least 16 hours. Responders to pronation were defined as patients whose PaO

2 increased by at least 10 mmHg or more after 30 minutes of the prone position and non-responders in whom the increase did not occur [

14,

15]. iNO administration was performed through the iNOmax DS

IR® delivery system supplied to our centre. Patients underwent multiple cycles of pronation. iNO administration details:

iNO was given after the failure of at least one pronation cycle.

iNO was continuously administrated during a supine than prone position.

iNO administration during the first hour was performed up to the maximum dose of 30 ppm for all patients to define their response.

Response to iNO was defined as a 20% increase in PaO2/FiO2 at T1 compared to T0 [

16].

iNO dosage was at the clinician's discretion and varied according to clinical needs.

Discontinuation of iNO administration was carried out gradually according to the weaning procedures in use at our centre [

17].

Continues variables were expressed in mean/standard deviation (S.D.) if normal distribution, or median [25–75 percentile] if non-normal distribution. The normal continuous variables were compared by T-test for two independent samples. Non-normally distributed variables were compared by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The comparison between variables in frequencies by Chi2. The normality of continuous variables was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (R.O.C.) curve was used to determine the accuracy of predictive values. Responders vs non-responders were stratified patient survival by Kaplan-Mayer (K.M.) Curve. Significance was calculated by the log-rank test. Hazzard ratio (H.R.) and Confidence Intervals (CI) for death were based on the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model (backward selection). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to identify responders’ predictors (backward selection). Multivariate models included the relevant clinical findings and the significant variables in the univariate analysis with p <0.01.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. R Cran for Windows 11 was used for all analyses.

Ethics approval: This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. All the procedures being performed were part of the routine clinical care. The study was conducted according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and authors are complying with the specific requirements of their institution and their countries.

The study was approved by Misericordia Hospital’s ethics committee, N: 23275-2022-11 on 21 November 2022.

3. Results

From Oct 1, 2020, to Oct 31, 2021, ninety-eight patients, who required Oro-tracheal Intubation (O.T.I.) for C-ARDS, were admitted to I.C.U. The mean age was 70.66 (11.4) years. The time from symptoms onset to I.C.U. Admission was 10.00 (5.5) days. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire population are shown in Table S1. Twenty-seven of them (28%) received iNO. Of these patients, twelve (44.4%) were responders, while fifteen (55.6%) were non-responders. All subjects underwent echocardiography before iNO administration, while H.R.T.C. was performed on 74% of patients (20/27). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups are shown in

Table 1. Therapy length was 6.27 (3.71) days in non-responders and 7.82 (4.55) in responders; the difference was not significant (p. 0.35). The time from symptoms onset to the beginning of iNO was similar in the two groups (p. 0.53)

: 6.33 (5.23) days in non-responders and 4.91 (6.13) in responders. The time from intubation to the beginning of iNO administration was also not significantly different between the two groups; 5.07 (4.75) days in non-responder

s vs 4.18 (5.86) in responders (p. 0.67). Changes in respiratory and inflammatory variables during the treatment between non-responders and responders were reported in Table S2. The univariate analysis showed that SOFA scores were positive predictors of iNO response, while previous P.N.X. and elevated D-Dimer values were negative predictors. The Multivariate Logistic Regression model, adjusted for clinically significant covariates and those that resulted significantly in univariate analysis, showed that a high SOFA score was the most important independent predictor of iNO response with a p. 0.04 (

Table 2). Finally,

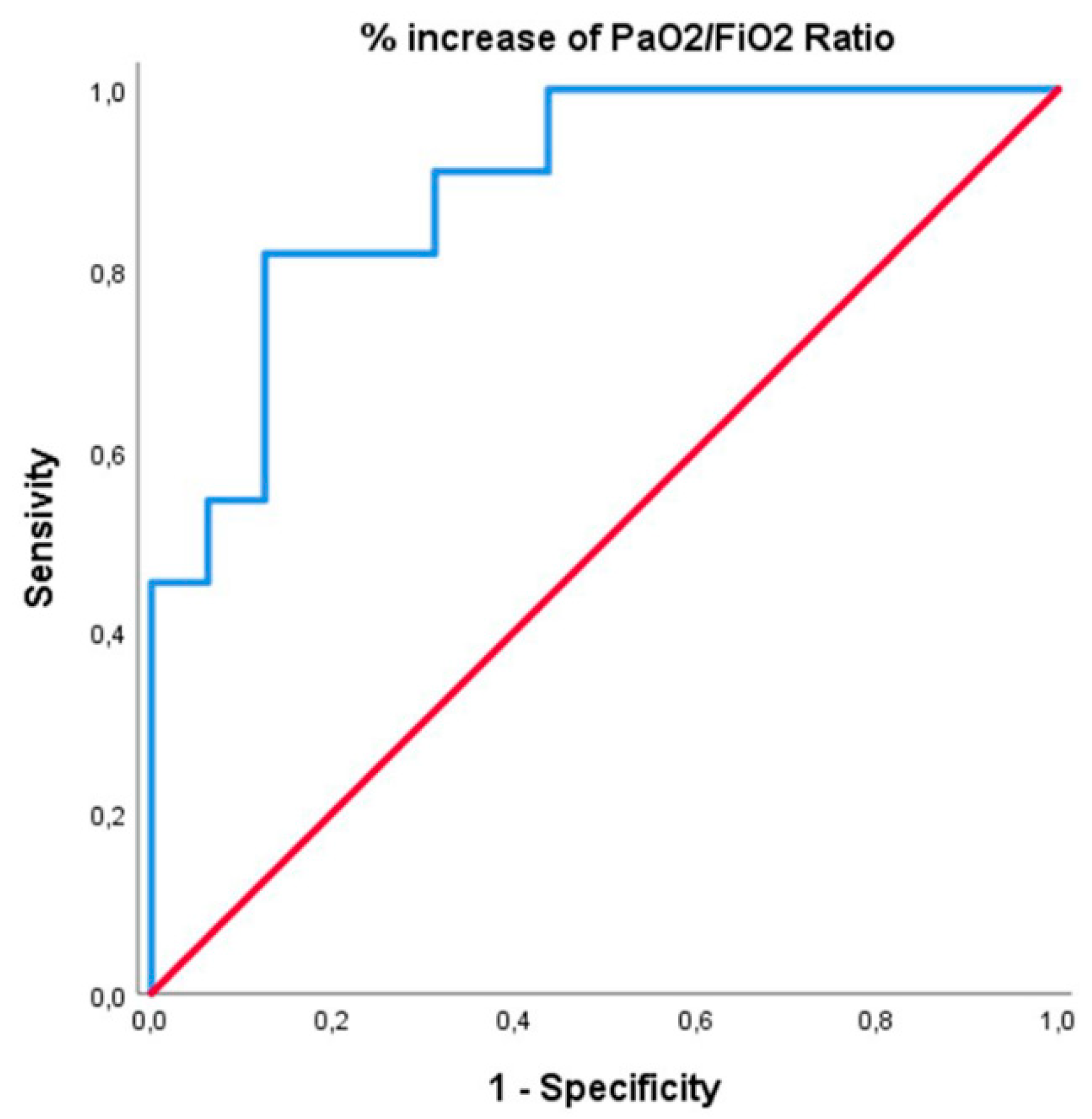

the R.O.C. curve analysis of prognostic factors of in-hospital survival for patients with C-ARDS was presented in

Figure 1. The Area Under Curve (A.U.C.) for a percentage value of PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio increase from baseline was 0.89, which confirmed that this factor has a higher predictive value for in-hospital survival. A 19% increase in PaO

2/FiO

2 can predict the death event with a sensitivity of 81.8% and a specificity of 81.2%. Thirty-seven (37.7%) out of the ninety-eight patients died during I.C.U. Stay. Seventeen (62.9%) of these deaths occurred to the twenty-seven patients to whom iNO was administered. Fourteen (87.6%) individuals died by M.O.F. due to severe hypoxia, one (6.2%) death was caused by M.O.F. non-Covid-19 related, and one (6.2%) was a cardiac death. Mortality was higher in group 1 vs group 2: 86.6% vs. 25.0%, respectively.

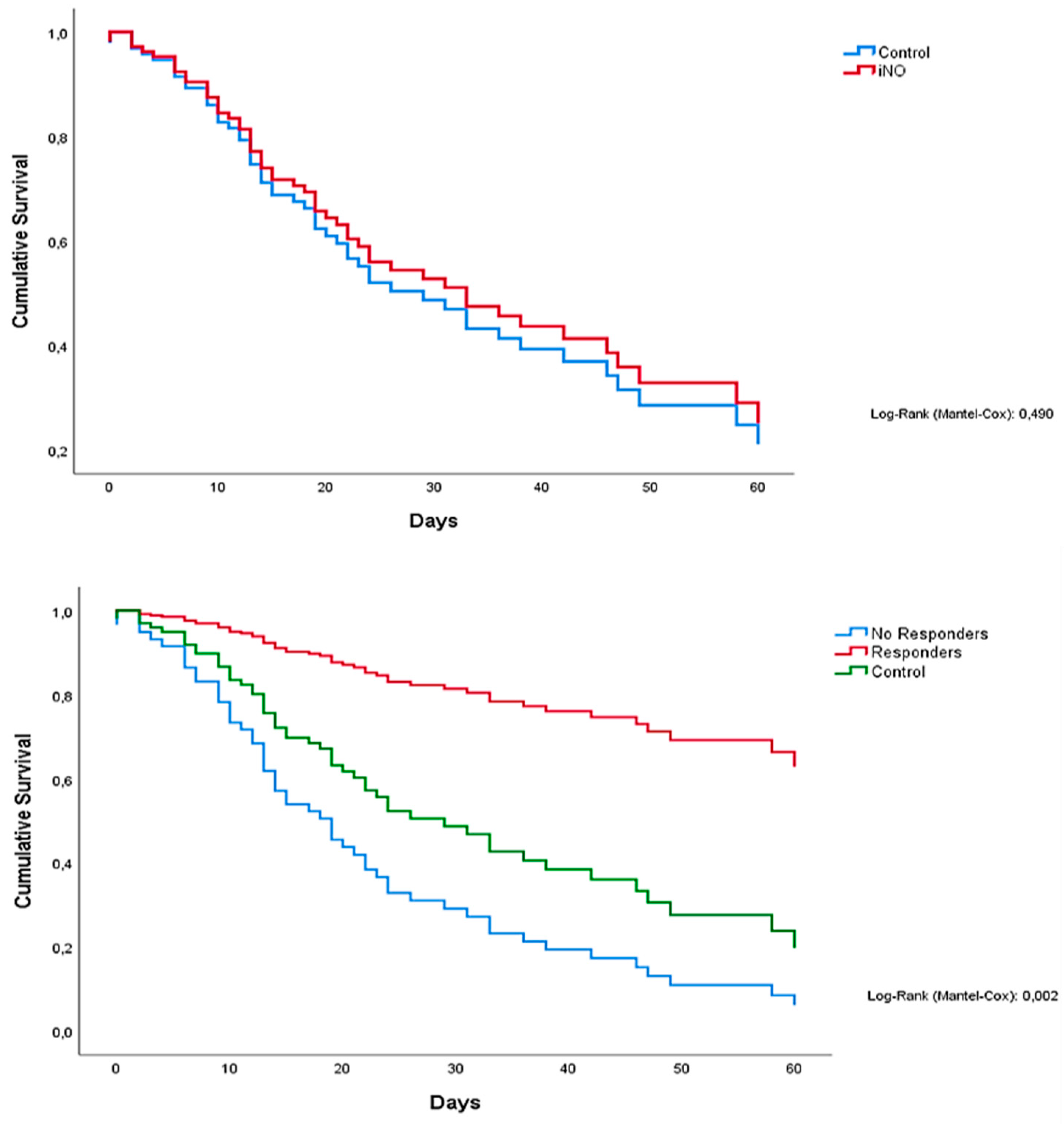

Figure 2 (above) depicts K.M. plots of all patients: those who were treated with iNO showed a similar survival compared with controls (not subjected to iNO), 31 days (95% CI 19.1 to 42.9) and 33 days (95% CI 16.6 to 49.4), respectively. In

Figure 3 (below), a K.M. plot visualizes patients' mortality stratified by groups (responders

, non-responders, and controls). Therefore, median survival time resulted higher in responders (>80 days) than in non-responders and controls: 20 (95% CI 11.9 to 28.0) and 33 days (95% CI 16.6 to 49.4), respectively. At the univariate analysis, age, iNO responders, O.T.I. to iNO time, Baricitimab, and D-dimer, were predictive values for mortality. Multivariate Proportional hazard Cox Regression model showed that the absence of response to iNO was the most important predictive value for mortality (p. 0.00). PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio (p. 0.03) and lack of P.N.X. (p. 0.02) were also predictive factors (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Proof of iNO efficacy in coronavirus disease dates back to 2004. However, several studies showed conflicting results. In a recent review, several single or multicenter studies had contrasting results regarding improvement in oxygenation and mortality [

18]. Some authors, like Ferrari [

19] and Abou Arab [

20], have not detected a significant change in the PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio in patients with severe Hypoxemia. While others

, like Chen and colleagues, have administered iNO in ARDS patients, recording an improvement in severe hypoxia and shortening the timing of ventilatory support compared to matched control patients [

4]. Recently Di Faenza et al demonstrated in non-ventilation patients that The use of high-dose inhaled nitric oxide resulted in an improvement of Pa

O2/Fi

O2 at 48 hours compared with usual care in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19 [

21].

Dessap et al report the benefits of iNO in improving arterial oxygenation in C-ARDS patients, improvement seems more relevant in the most severe cases, and in patients with ECMO criteria, an iNO-driven improvement in gas exchange was associated with better survival [

22].

iNO improves arterial oxygenation by alleviating the V/Q ratio. It usually resolves Hypoxemia by dilating the blood vessels of those lung regions open to ventilation (and iNO). In this way, it diverts the blood flow away from areas of alveolar consolidation, thus reducing the functional shunt [

5]. However, no one has ever given the weight that not all patients respond in the same way to the administration of nitric oxide, and it is known that some respond and others do not. Could this answer be used for prognostic purposes? In our opinion, it could, of course. Our study highlighted how the patient who responds to nitric oxide has much lower mortality. However, the pathophysiological reason is not known.

Almost all authors focused only on the anatomical component in explaining C-ARDS pathophysiology. Gattinoni and colleagues described two clinical-pathological phases in the context of COVID-19 pneumonia. Initially, isolated viral pneumonia (type L) presents with near-normal compliance, low V/Q ratio, and low lung recruitment capacity. Subsequently, COVID-19 pneumonia (type H) meets stringent ARDS criteria with low compliance [

23]. These authors have assumed that iNO therapy should ideally be initiated in the early transition between the two phases as there is an increase in shunt and, therefore, still the recruitment capacity [

24]. Other authors had hypothesized that in some patients with C-ARDS (especially those of "type L"), pulmonary shunt, resulting from diffuse alveolar damage, is not the only mechanism explaining Hypoxemia [

25]. Vascular and perfusion abnormalities such as pulmonary embolism appear higher in COVID-19 pneumonia than in classic ARDS [

26,

27,

28]. Perhaps this is due to a specific pulmonary procoagulant pattern [

29], which causes alveolar capillary microthrombi, as revealed by post-mortem studies [

30,

31]. Ackermann et al. reported intussusceptive angiogenesis, which explains pulmonary vascular endotheliosis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19 [

32]. These mechanisms concur with pulmonary vasoconstriction, a possible tool for V/Q mismatch and Hypoxemia during C-ARDS. These abnormalities represented the anatomical component. Beyond this, there could be a functional and reversible constituent, likely linked to endothelial dysfunction with consequent vasoconstriction at the level of the vascular bed, especially the alveolar, which involves a reduction in V/Q. This could be explained by the inflammatory cytokine storm induced by a viral infection [

33]. Therefore, the higher the cytokine load, the greater the functional share. However, the two components, anatomy and function, coexist and combine to varying degrees. Thus, different degrees of severity and probably variously responsive patterns to iNO are determined. The stimulation with iNO is less effective in the case of severe anatomic (irreversible) damage from dysfunction of the endothelium [

34] and more effective in the presence of a more significant share of the functional component (reversible). Moreover, inhaled nitric oxide can highlight the existence of this functional constituent, which is also reversible and variable from patient to patient. At this stage, when the functional element is sufficiently represented, there would be a more significant response to the administration of iNO. Which would allow the identification of these patients with a significant reversible share (responders) and a better prognosis. This component occurred at the microcirculation level and often had a mosaic distribution [

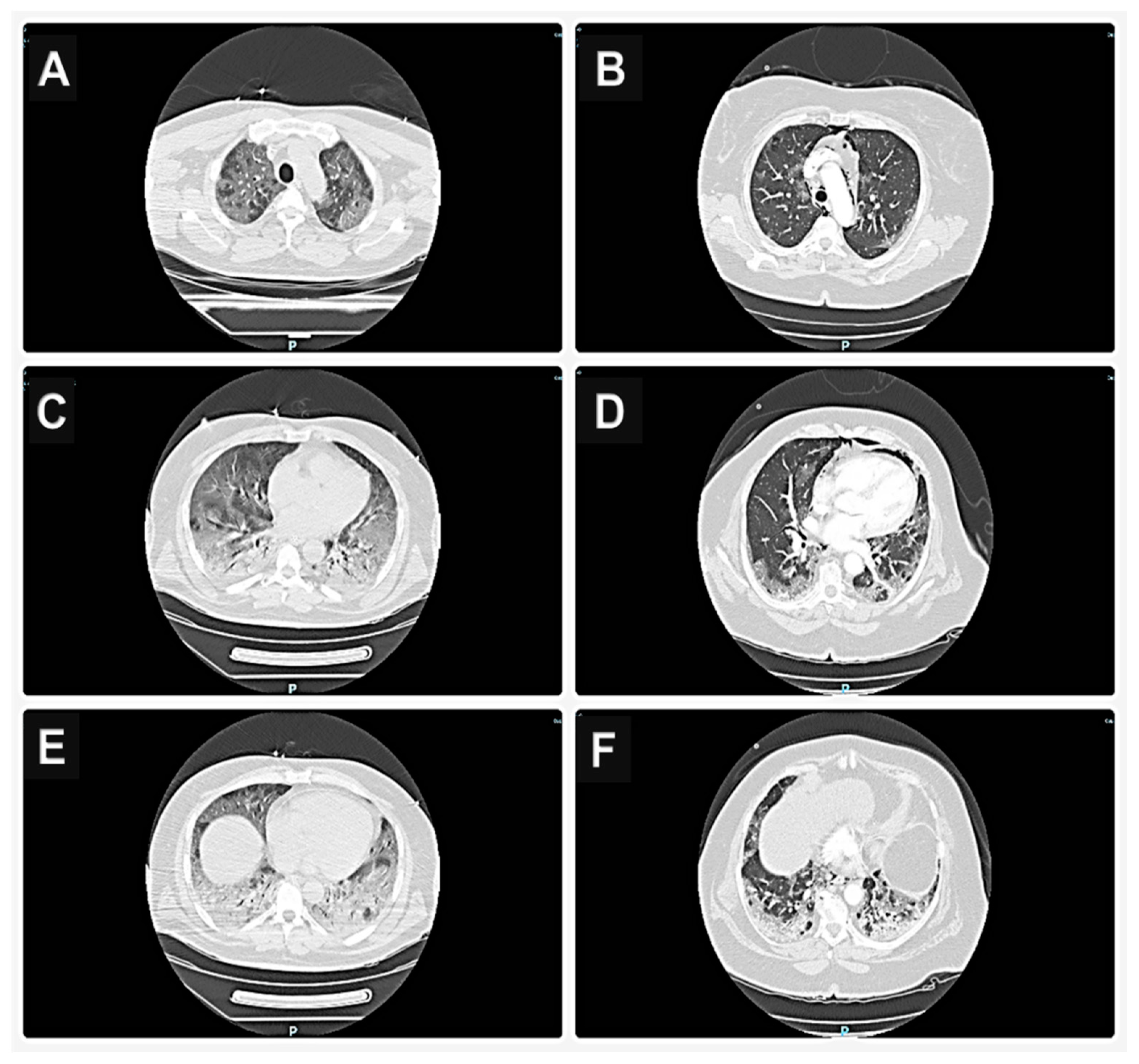

28] challenging to detect with instrumental methods such as C.T. We did not find any difference

s between the C.T. scans in the two groups.

Consequently, the functional component can be well represented even in severe C.T. scans or be scarce or absent in mild images. Therefore, the absence of response to iNO cannot be attributed to a greater extent of ground glass opacities in non-responders (

Figure 3). Therefore, our results have identified iNO therapy as able to recognize the presence of this functional and reversible component and consequently its importance as a relevant discriminant of the prognosis. Indeed, we found that mortality was higher in non-responders than in responders (86.6% vs 25.0%, respectively). Our results align with a previous study by Caplan and colleagues, who also found a reduction in mortality in subjects who responded to iNO [

35]. Unfortunately, not all patients respond to nitric oxide administration. In (the) literature, the percentage of responders varies from 25 to 65% [

7,

8]. In our population, 44% of patients (have) responded to iNO. The R.O.C. curves showed that a PaO

2 value of 19% has a predictive value with a sensitivity of 81.8% and a specificity of 81.2%, very close to our threshold value used a priori to distinguish responders from non-responder

s. Therefore, in patients with severe persistent Hypoxemia, such as in the idiopathic pulmonary hypertension guidelines [36], we propose using iNO to evaluate the reversibility of severe hypoxia to stratify the prognosis (iNO test).

Several limitations of this study need to be mentioned. Firstly, this was a single-centre study with a small number of patients. Secondly, it had a retrospective design. Thirdly, iNO was not integrated into a therapeutic algorithm, and its infusion was performed at different stages of I.C.U. Stay. Finally, it was impossible to perform lung scintigraphy to evaluate the V/Q mismatch for logistical reasons.

5. Conclusions

The administration of iNO has determined a temporary improvement of the V/Q ratio, especially in patients defined as responders to therapy. The percentage of patients who responded to treatment was about 44.4%, generally the subjects with the highest SOFA score. Those who did not respond to the iNO administration showed a higher mortality rate than those who did. The 19% increase in PaO2 was a positive predictor of mortality, and this could be used as a prognostic stratification test with an 81.8% sensitivity and 81.2% specificity. Therefore, we propose using iNO as a prognostic stratification test in C-ARDS patients with persistent severe hypoxia. Further studies must confirm our results and evaluate any clinical and therapeutic implications.

Authors' contributions

Pasquale Baratta: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Writing, review, and editing. Francesco De Sensi: conceptualization, writing, thinking, and editing. Alberto Cresti: supervision, validation, review, and editing. Federica Re: data curation, formal analysis. Genni Spargi: data curation, research, review. Ugo Limbruno: conceptualization, formal analysis, review, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research study was conducted retrospectively from data obtained for clinical purposes. All the procedures being performed were part of the routine clinical care. The study was conducted according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and authors are complying with the specific requirements of their institution and their countries. The study was approved by Misericordia Hospital’s ethics committee, N: 23275-2022-11 on 21 November 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for this study was not obtained as the patients were unconscious and consent was not possible to obtain. Furthermore, the administration of the drug was carried out based on clinical needs and not for study reasons. The patients are not recognizable in this study as the identifying data are unavailable and therefore it is not possible to request consent for publication

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

All the authors report they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 8 (2020) 475–481. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 323 (2020) 1061–1069. [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Yeming W, Xingwang L, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, Lancet 395 (2020) 497–506. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Liu P, Gao H, Sun B, Chao D, Wang F, et al. Inhalation of nitric oxide in treating severe acute respiratory syndrome: a rescue trial in Beijing. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:1531–5. [CrossRef]

- Karam O, Gebistorf F, Wetterslev J, Afshari A. The effect of inhaled nitric oxide in acute respiratory distress syndrome in children and adults: a Cochrane Systematic Review with trial sequential analysis. Anesthesia 2017; 72:106–17. [CrossRef]

- Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020 May;46(5):854-887. Epub 2020 Mar 28. [CrossRef]

- Tavazzi G, Marco P, Mongodi S, Dammassa V, Romito G, Mojoli F. Inhaled nitric oxide in patients admitted to intensive care unit with COVID-19 pneumonia. Crit Care 2020; 24: 508. [CrossRef]

- Garfield B, McFadyen C, Briar C, Bleakley C, Vlachou A et al. Potential for personalized application of inhaled nitric oxide in COVID-19 pneumonia. Br J Anaesth. 2021 Feb;126(2): e72-e75. Epub 2020 Nov 14. [CrossRef]

- Ranieri V, Rubenfeld G, Thompson B, Ferguson N, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. J.A.M.A. 2012; 307:2526–33. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Clinical care for severe acute respiratory infection: toolkit: COVID-19 adaptation, update 2022. [https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/352851]. 1066.

- Becher T, van der Staay M, Schädler D, Frerichs I, Weiler N. Calculation of mechanical power for pressure-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Sep;45(9):1321-1323. [CrossRef]

- Giosa L, Busana M, Pasticci I, Bonifazi M, Macrì MM, Romitti F et al. Mechanical power at a glance: a simple surrogate for volume-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019 Nov 27;7(1):61. [CrossRef]

- Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, Zhang N, Huang M, Zeng X, et al. Ct imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology 2020; 295: 202–7. [CrossRef]

- Flaatten H, Aardal S, Hevr Y O. Improved oxygenation using the prone position in patients with ARDS. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1998; 42: 329-334. [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni L, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, Taccone P, Mascheroni D, Labarta V et al; Prone-Supine Study Group. Effect of prone positioning on the survival of patients with acute respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 23;345(8):568-73. [CrossRef]

- Ichinose F, Roberts JD Jr, Zapol WM. Inhaled nitric oxide: a selective pulmonary vasodilator: current uses and therapeutic potential. Circulation. 2004; 109:3106–11. [CrossRef]

- Aly H, Sahni R, Wung JT. Weaning strategy with inhaled nitric oxide treatment in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997 Mar;76(2): F118-22. [CrossRef]

- Xiao S, Yuan Z, Huang Y. The Potential Role of Nitric Oxide as a Therapeutic Agent against SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023,24,17162. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari M, Santini A, Protti A, Andreis D, Iapichino G, Castellani G et al. Inhaled nitric oxide in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. J Crit Care 2020; 60: 159e60. [CrossRef]

- Abou-Arab O, Huette P, Debouvries F, Dupont H, Jounieaux V, Mahjoub Y. Inhaled nitric oxide for critically ill Covid-19 patients: a prospective study. Crit. Care (2020) 24:645. [CrossRef]

- Di Faenza R, Shetti NS, Gianni S, Parcha V, Giammatteo V, Fakhr BS, Tornberg D et al. High-Dose Inhaled Nitric Oxide in Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure Due to COVID-19: A Multicenter Phase II Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023 Dec 15;208(12):1293-1304. [CrossRef]

- Dessap AM, Papazian L, Schaller M, Nseir S, Megarbane B , Haudebourg L, Timsit JF. Inhaled nitric oxide in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by COVID-19: treatment modalities, clinical response, and outcomes. Annals of Intensive Care (2023) 13:57. [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L et al: COVID-19 pneumonia: Different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:1099–110. [CrossRef]

- Lotz C, Muellenbach R, Meybohm P, Haitham Mutlak, Philipp M. Lepper, Caroline-Barbara Rolfes et al. Effects of inhaled nitric oxide in COVID–19–induced ARDS – Is it worthwhile? Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020 27. [CrossRef]

- Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, Jacobson SD, Meyer BJ, Balough EM, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020; 395:1763–70. 28. [CrossRef]

- Lang M, Som A, Mendoza DP, Flores EJ, Reid N, Carey D, et al. Hypoxemia related to COVID-19: vascular and perfusion abnormalities on dual-energy C.T. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Lassalle F, et al. Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Circulation. 2020; 30. [CrossRef]

- Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Di Dedda U, Bayshnikova E, Dei Poli M, Resta M, et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2020 31. [CrossRef]

- Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 32. [CrossRef]

- Menter T, Haslbauer JD, Nienhold R, Savic S, Hopfer H, Deigendesch N, et al. Post-mortem examination of COVID-19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings of lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Copin MC, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Poissy J, Mathieu D, Lille C-I, Anatomopathology G. Time to consider the histologic pattern of lung injury to treat critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46(6):1124–6. [CrossRef]

- Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Xavier Delabranche et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med [Internet]. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Caplan M, Goutay J, Bignon A, Jaillette E, Favory R, Mathieu D et al; Lille Intensive Care COVID-19 Group. Almitrine Infusion in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Single-Center Observational Study. Crit Care Med. 2021 Feb 1;49(2): e191-e198. [CrossRef]

- Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (E.S.C.) and the European Respiratory Society (E.R.S.): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (A.E.P.C.), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (I.S.H.L.T.). Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:67–119. 10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).