1. Introduction

When considering sustainable urban policies, it is essential to understand urban transformation from multiple perspectives, including social, political, economic, and environmental perspectives, and to forecast the future [

1]. Due to their relevance to this subject, there have been many published discussions on compact city policies, especially in developed countries that are members of the OECD, and the pros and cons of such policies have been questioned [

2]. The compact city policy has been proposed as a solution to land resource conservation, global warming countermeasures, energy problems, and financial crises, with the three goals of increasing urban density, connecting public transportation, and providing access to public services. In addition, urban policies will be further required to respond to social issues such as population decline, aging population, and smaller households in developed countries.

However, looking at Japan's compact city policies, it is difficult to say whether they have been successful in consolidating cities [

3]. This is partly due to the fragmentation of land ownership, which has resulted in a patchy low-density pattern and the designation of a wide range of central urban areas. This situation tends to be viewed as unique to Japan, but similar phenomena are beginning to be reported in Europe, the U.S., and other developed countries [

4]. Therefore, it would be meaningful for sustainable urban policies in developed countries to adhere to the guidelines that Japan's compact city policy has followed (Annotation A1 in

Appendix A). This paper will begin with an overview of the decline and peri-urbanization of city centers from the period of population expansion to the period of population decline and then introduce the trends in Japan's compact city policies in response to these conditions. This paper is not a discussion of compact city policies but rather a discussion of how compact cities should be defined in the first place by considering the intensification of land use, especially for housing, to be classified as a compact city.

When considering Japan's compact city policies, it is necessary to consider urban sprawl and the decline of central city areas as integral parts of these policies.

The background of urban sprawl is the development of motorization. In Japan, the spread of automobiles, especially in rural areas, has led to a situation where "one car per resident" is close to "one car per person," which, in turn, has led to the development of suburban areas with well-developed road networks. The development of motorization encouraged the construction of housing along existing roads in the peri-urban area without public infrastructure, such as electricity, water, sewerage, and roads, leading to inefficient public services [

5]. In addition, urban sprawl was brought about by the expansion of large-scale commercial facilities along main roads, utilizing former farmland and factory sites. Although the Large-Scale Retail Stores Law at the time allowed for adjustments in the opening of large-scale commercial facilities, the Large-Scale Retail Stores Law was deemed a barrier to entry for Japan in the 1990 Japan–U.S. Structural Impediments Agreement, and in 1991, the operation of the law was greatly relaxed, accelerating the location of large-scale commercial facilities in peri-urban areas. The deregulation of large-scale commercial facilities has led to the decline of the commercial function of central city areas as well as the peri-urbanization of residential areas [

6].

Therefore, it was decided that a comprehensive response to urban sprawl and the decline of central city areas must not be limited to adjustments in the opening of large commercial facilities but must also include other town functions in accordance with local conditions. As a result, between 1998 and 2000, the following measures were enacted: the revised City Planning Law, which allows flexible land use regulations for the proper placement of various town functions, including large-scale commercial facilities; the Large-Scale Retail Stores Location Law, which provides new regulations for large-scale commercial facilities, including measuring their impact on the living environment (the previous Large-Scale Retail Stores Law was abolished), such as shopping districts, etc. The Three Laws of Town Planning were enacted to support activities to revitalize shopping malls and restore the liveliness of central city areas. However, even with these laws, the sprawl of suburban areas could not be halted (Annotation A2 in

Appendix A).

The Three Laws of Town Planning were revised in 2006. The revision to the Three Laws of Town Planning involved strengthening regulations on the localization of large-scale commercial facilities in peri-urban areas and required local governments to formulate new, more effective Master Plans for Revitalization of Central City Areas. Effective measures were required to both prevent urban sprawl and the doughnutization of central city areas, and the hurdles for policy introduction became higher. For this reason, the pace of the approval of Master Plans for Revitalization of Central City Areas under the revised Three Laws of Town Planning was very slow, with only two policies first approved in February 2007: Aomori City, which is very often regarded as a representative example of a compact city policy, and Toyama City.

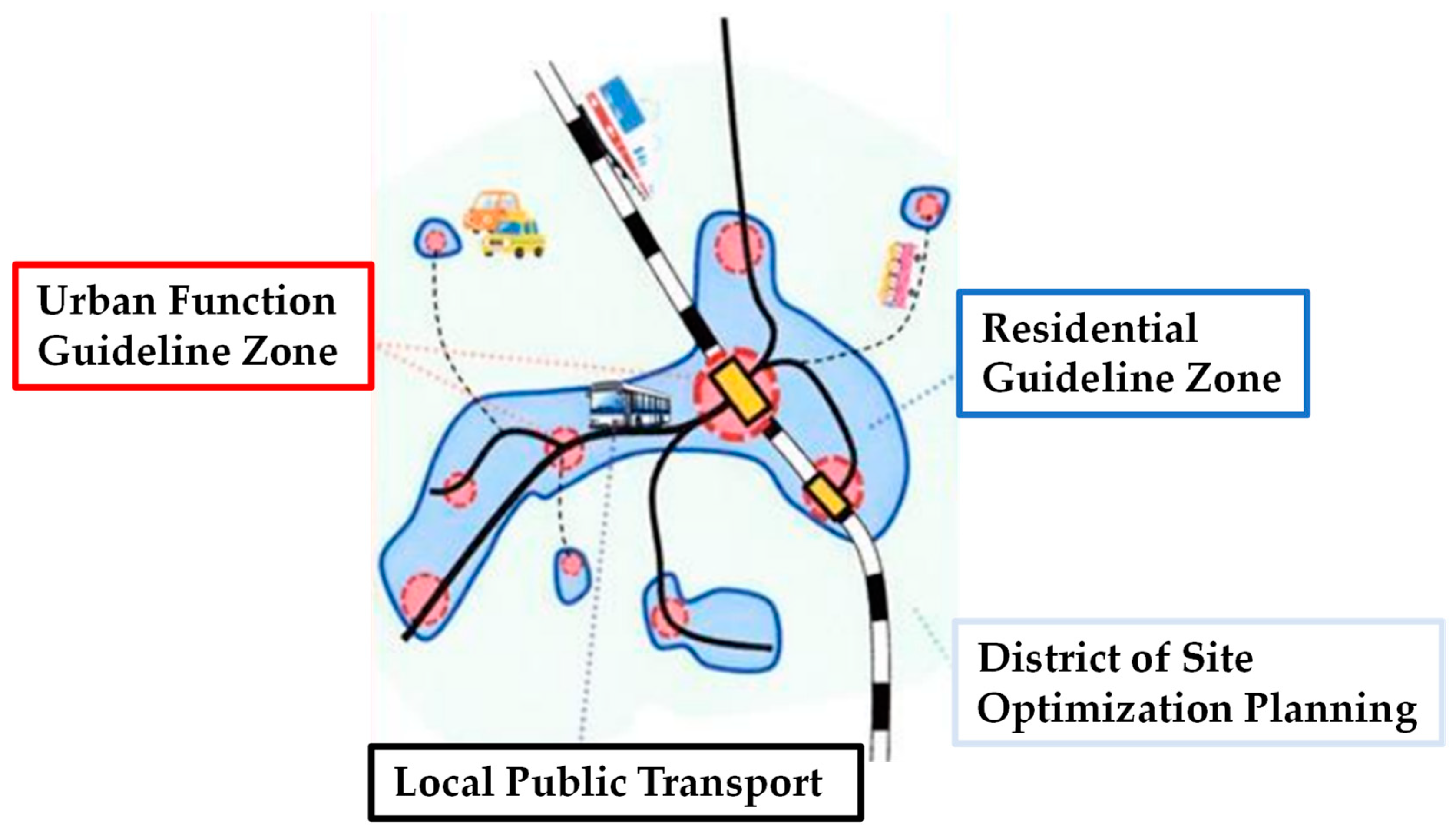

Furthermore, in 2014, the Special Measures for Urban Revitalization policy was revised, creating the Site Optimization Plan. Furthermore, in 2014, the Law on Special Measures for Urban Revitalization was amended to create the Location Adequacy Planning System. The term compact plus network was introduced for the first time in this location optimization planning system.

The term compact city has been used to refer to the concentration of various functions in one central city area within a municipality, as seen in Aomori City, while the compact plus network refers to an urban function guiding zone that is positioned like a conventional central city area. In the compact plus network, in addition to the urban function guiding zone, which is positioned like the conventional central city area, a residential guiding zone is established, and residents in the residential guiding zone are expected to have access to the urban function guiding zone via public transportation. In other words, the compact plus network is a policy that aims to create a compact city by integrating the city into multiple locations and linking them with public transportation (

Figure 1).

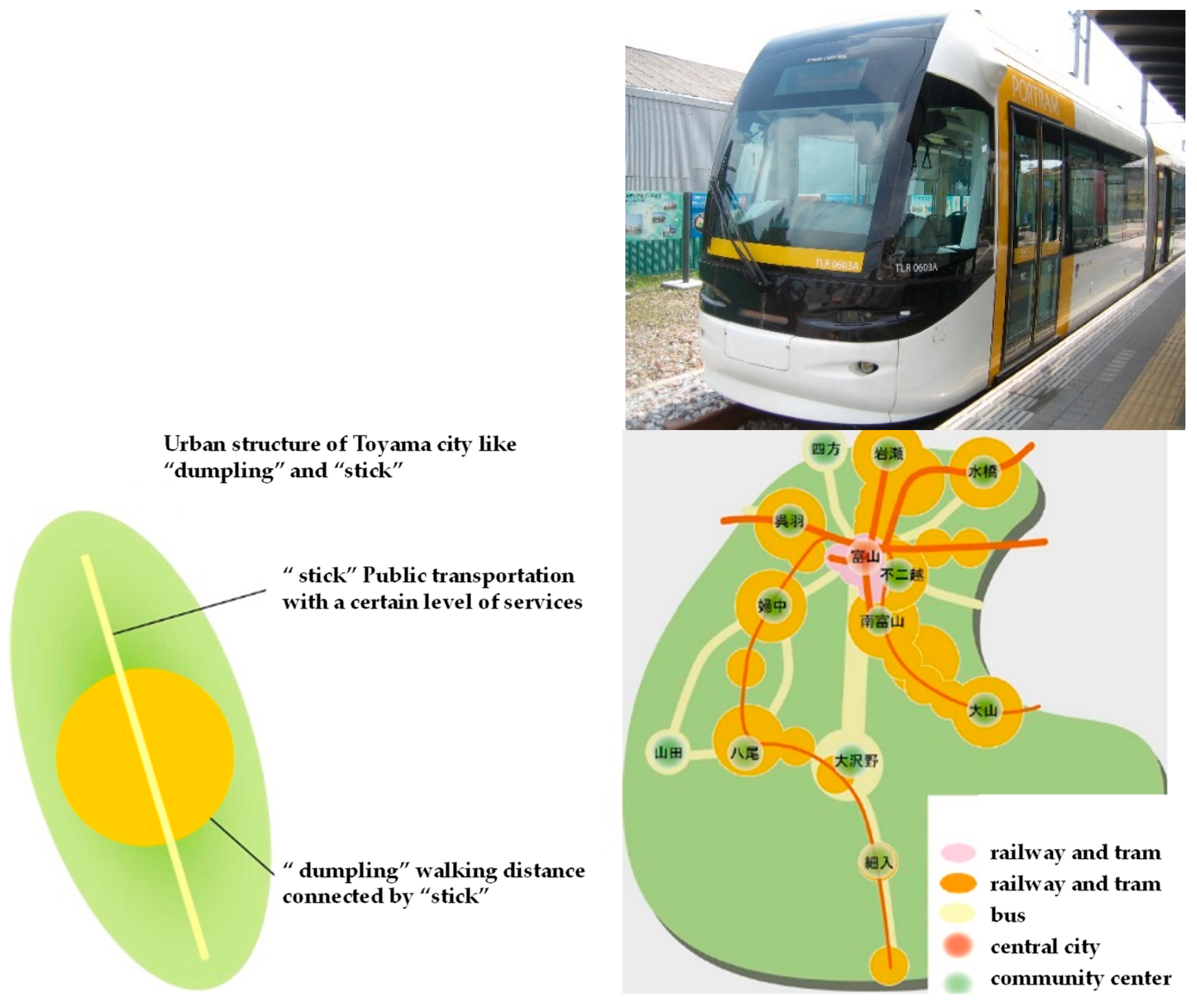

This idea can be seen in Toyama City, which, along with Aomori City, is considered a representative example of a compact city. For example, according to Toyama City's Master Plan for Revitalization of Central City Areas (2007), the concept for creating a compact city is to develop regional lifestyle centers along railway tracks, bus routes, and other arterial public transportation lines, where the functions and population necessary for daily life, such as commerce, medical services, and administrative services, are concentrated. The city of Toyama is considered to be a compact city. The concept of Toyama City's compact city is expressed in the unique expression of "dumplings" (residential areas, etc.) and “sticks” (public transportation) and can be considered a pioneering policy of the current compact plus network (

Figure 2).

The advantages of this compact plus network concept include the fact that it is less likely to be criticized as a cut-off of the peri-urban since some peri-urban residents have difficulty moving to the central city for economic reasons and that it is easier to cooperate with suburban municipalities that are in the same economic zone and linked by public transportation. In Japan, there have been long-standing attempts to create compact cities. While there have been long-standing attempts to create compact cities in Japan, the results of these attempts have been less visible, and the compact plus network is one of the moves toward a realistic solution. In addition, the reality that induction has not progressed as far as expected despite the economic incentives provided by Toyama City to relocate residential areas to the city center and around public transportation facilities, such as LRT, which can be seen as a limitation of Japan’s compact city policy [

7].

Thus, it can be seen that Japan's compact city policies were an effort to respond to the peri-urbanization and decline of central city areas caused by motorization during the period of population expansion. As mentioned earlier, these efforts were not always successful. One of the reasons for this is the unplanned and unregulated construction of housing during the period of population expansion and the failure to guide people to the station area and to guide housing to the central city area as expected. The occurrence of vacant houses in a period of declining population is causing the city to become densely populated, and at the same time, they are becoming more apparent in patches. In contrast, the mismatch between housing supply and demand encourages new local housing construction. This raises concerns about inefficient public infrastructure development and the supply of public services in the future (

Figure 3).

There have been many accumulated studies on vacant houses in Japan, as detailed in Masuda and Akiyama (2020) [

10]. In previous studies, demographic trends (population growth rate, population density, population migration, aging rate, etc.), economic trends (land prices, market retention period, distance from railroads, etc.), and building conditions (age, floor space, excess construction starts, etc.) were often used to estimate the actual condition and future prospects of vacant houses [

11]. This study focuses on household trends and building conditions among demographic variables for the following reasons: Housing supply and demand during periods of economic growth are mainly driven by supply-side economic principles due to a shortage of housing stock. In contrast, housing supply and demand during periods of population decline are likely to be largely driven by demand-side economic principles, as the housing supply is already sufficient. In particular, changes in household trends are likely to be a major factor affecting both the supply and demand for housing and the regeneration and utilization of vacant housing [

12].

This paper outlines the current situation and describes how changes in family structure and the trend toward smaller households, including single households, affect housing trends. In particular, we focused on single-family detached houses, which are thought to cause a mismatch between housing demand and household size, and proposed the concept of a compact city by discussing countermeasures for the future occurrence of vacant houses (Annotation A3 in

Appendix A).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

In this paper, analysis is conducted from the perspective of prefectures and municipalities, which are the administrative units used to examine urban planning in Japan. First, in looking at the whole country by prefecture, we selected two cities located in metropolitan areas and their peri-urban areas, which were selected by Ohashi and Phelps (2020) [

13] for the Tokyo metropolitan area urban center and peri-urban area, using socio-demographic, economic, and political and administrative (fiscal) indicators to determine urban center (Urban Territory), suburban area (Suburban Territory), and urban suburbs (Periphery). The study categorizes urban centers and suburbs into Inner Suburban Territory, Outer Suburban Territory, and Peri-urban Territory based on socio-demographic, economic, and political/administrative (fiscal) indicators. In this paper, case studies were conducted in the inner city and its suburbs. Specifically, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, located in the center of the Tokyo metropolitan area, and Wakayama City, Wakayama Prefecture, located in the peri-urban of Osaka Prefecture in the Osaka metropolitan area, were the subjects of this study.

Taishido, located in Setagaya Ward, is a town where many workers in central Tokyo work. Such a town is called a “bed town” in Japan. It is conveniently located within 15 km of Tokyo Station, a 30-minute train ride away. Setagaya Ward is known for its postwar districts that were rezoned in stages, but Taishido was excluded from the rezoning process and was positioned as a densely wooded urban area. The large number of vacant houses based in this densely wooded urban area will likely become long-term vacant in the future. Although the compact city policy is not currently being promoted, the compact city concept will need to be further examined in the future.

In contrast, the central city area of Wakayama City is the prefectural capital of Wakayama Prefecture and a key transportation hub. Within a 70 km radius of Osaka Station and an hour and a half train ride away, the city is recognized as a commuter hub for the Osaka metropolitan area. The central area of Wakayama City is an area that was rezoned in response to postwar earthquake reconstruction and urbanization during the period of rapid economic growth. It is an area where the compact city policy has been applied by the national government, and as part of this policy, measures are being taken to address vacant houses.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

To see the relationship between populations, households, and housing by prefecture, we used the National Census, which is conducted every five years by the Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, to determine changes in populations and households by prefecture over the past 25 years. We also used data from the Ministry’s “Housing and Land Survey” and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s “Building Statistics Survey” to show trends in the number of vacant houses and new housing construction. Furthermore, using these data sets, we looked at the correlation between the increase in the number of single households and housing trends as references.

In order to contrast the relationship between households and housing between urban centers and their suburbs, we focused on the increase in the number of single households by age group at two survey sites in the Tokyo metropolitan area and Wakayama Prefecture and used the “National Census” to identify trends in household types. Similarly, the number of vacant houses and newly developed houses were collected from the “Housing and Land Survey” and the “Construction Survey”. Using these data as a reference, we examined the factors behind housing trends based on changes in household composition.

In order to understand the spatial characteristics of housing trends, the target sites were narrowed down to two locations, Taishido, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, and the central city area of Wakayama City, and the locations of vacant houses that may occur in the future and newly developed houses were shown on a map. The “ZMap TOWN 2 2022 Shape Ver., Tokyo and Wakayama Prefecture Data Set”, updated annually by Zenrin Co., was used to select the housing types. In addition, the “Tokyo and Wakayama Prefecture, Human Flows Dataset”, operated by the Human Flows Project, was used to identify the residence locations of middle-aged and older single households, and cross-analysis was conducted using GIS (Annotation A4 in

Appendix A).

3. Results

3.1. Population and Household Trends in Japan

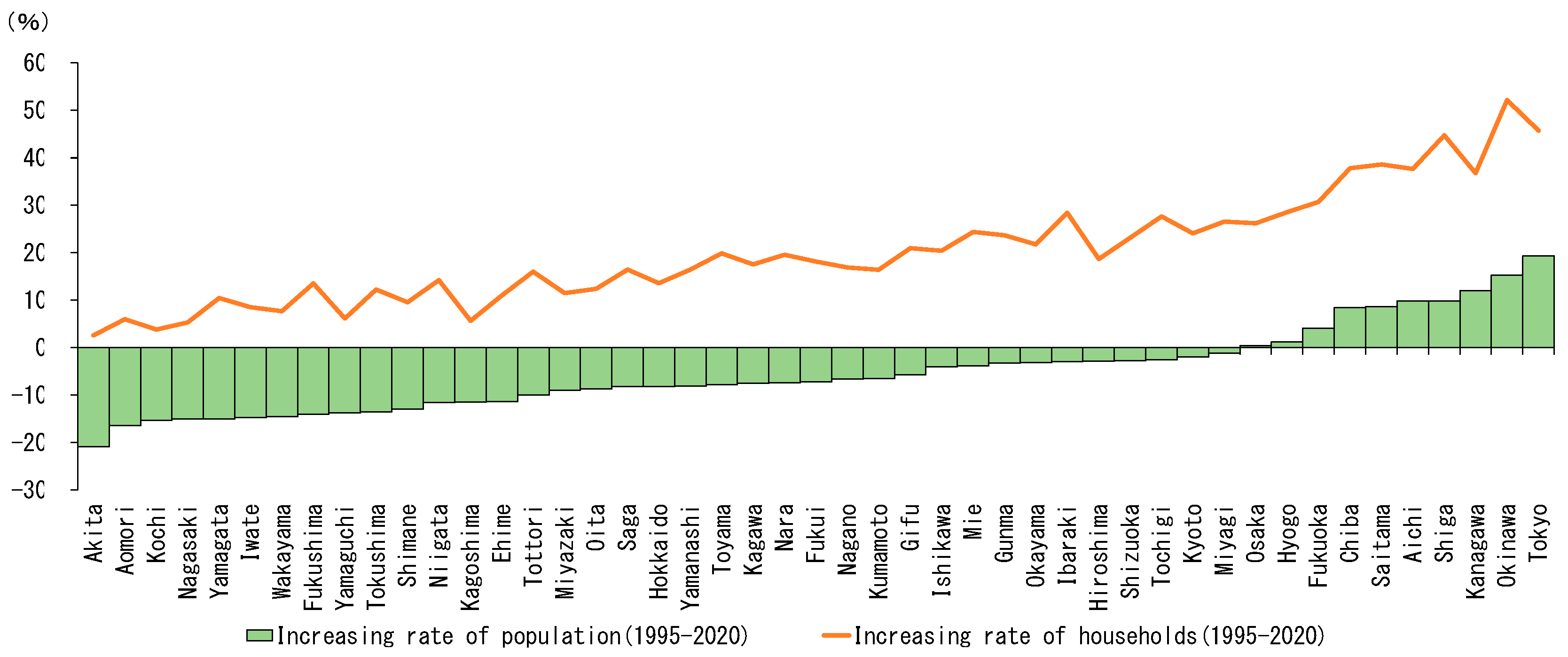

Figure 4 shows changes in population and households by prefecture. The population decreased in all prefectures except for the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba Prefectures) and Aichi, Shiga, Osaka, Hyogo, Fukuoka, and Okinawa Prefectures. In contrast, the number of households has increased in all prefectures, reflecting the increase in the number of single households and other factors that have led to smaller households. This paper focuses on Tokyo, which has the highest population growth rate by prefecture and the second highest household growth rate after Okinawa Prefecture, and Wakayama Prefecture, which is located in the “bed town” of the Osaka Metropolitan area and has the seventh highest population decline rate by prefecture, while the number of households has slightly increased.

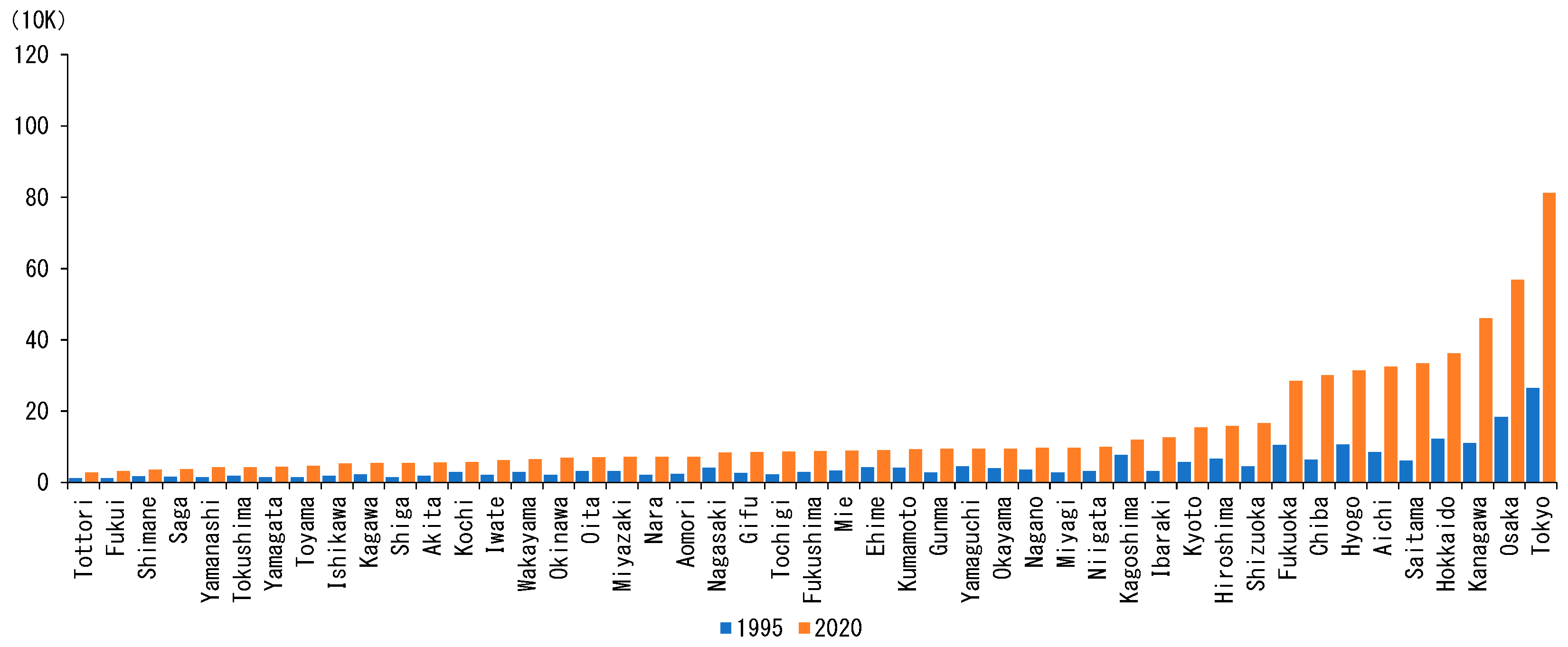

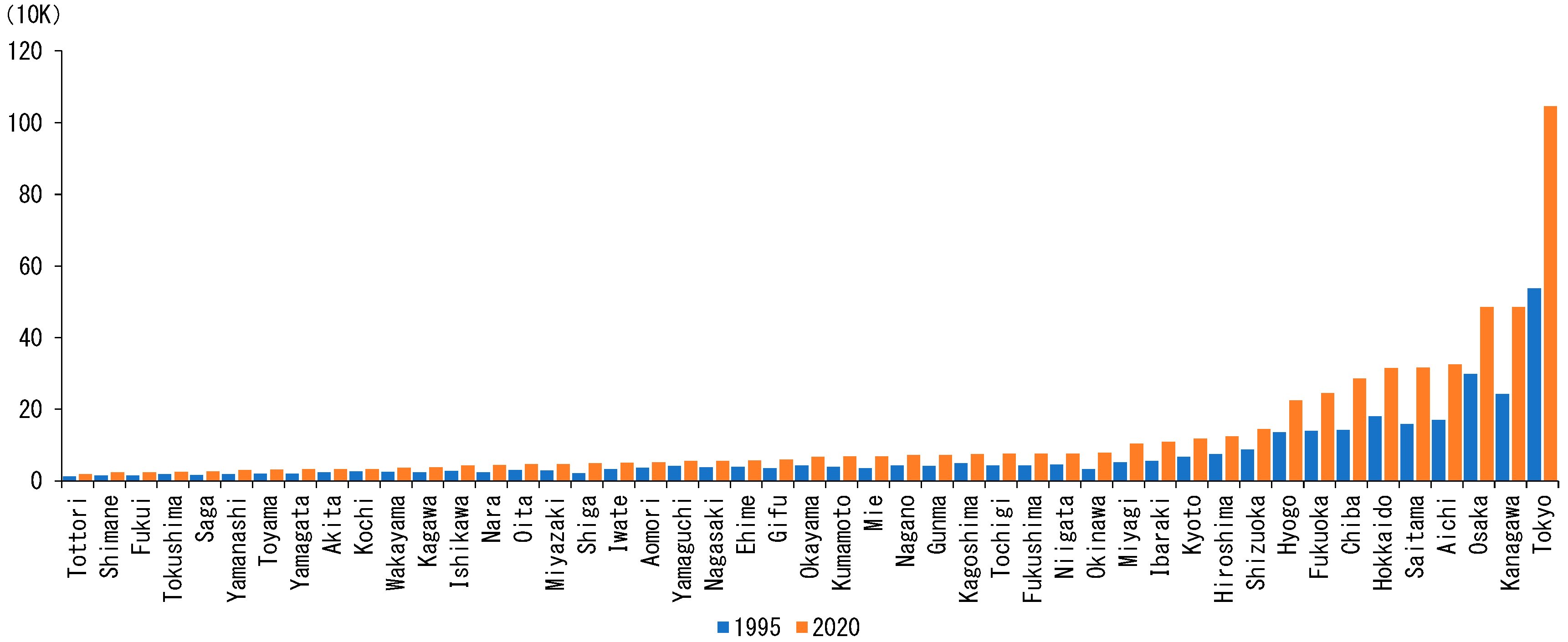

Figure 5 shows the number of single households (aged above 65) ("elderly single households" in the following) by prefecture in 1995-2020. The number of elderly single households is increasing in all prefectures, especially in the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba Prefectures) and Osaka, Aichi, and Fukuoka Prefectures, as well as in Hokkaido. Figure

6 shows that the number of single households (aged 40-64) ("middle-aged single households" in the following) in 1995-2020 also increased in all prefectures, with particularly large increases in the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba prefectures), in Osaka and Aichi Prefectures, and also in Hokkaido and Okinawa.

3.2. Trends for Vacant House Occurrences

Figure 7 shows the relationship between the number of elderly single households and the number of vacant houses (Annotation A5 in

Appendix A) that are unlikely to be used in the future.

Tokyo has had a large increase in the number of elderly single households, and the increase in the number of vacant houses is less than that in other prefectures. This indicates that Tokyo is an area where vacant houses are likely to be marketed again. In contrast, Wakayama Prefecture is positioned as a municipality with a small increase in the number of elderly single households and a large increase in the number of vacant houses. In contrast, Wakayama Prefecture is positioned as a municipality with a small increase in the number of elderly single households and a large increase in the number of vacant houses. In contrast to Tokyo, once a house becomes vacant, it is difficult to reuse it as a rental or sale property due to significant deterioration and a mismatch in housing demand [

15].

3.3. Trends for New House Development

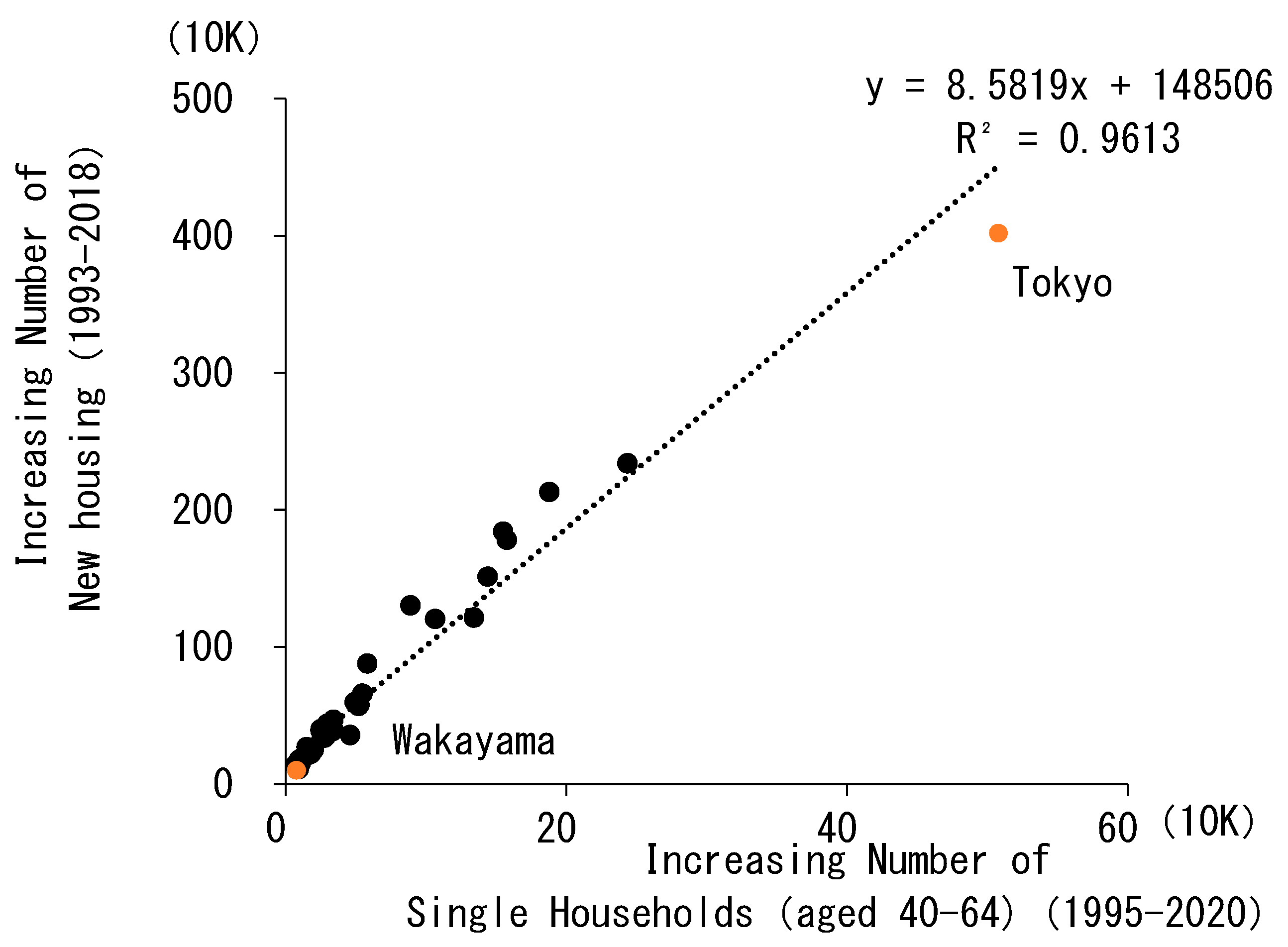

Figure 8 shows the relationship between the number of middle-aged single households and the number of new housing units built.

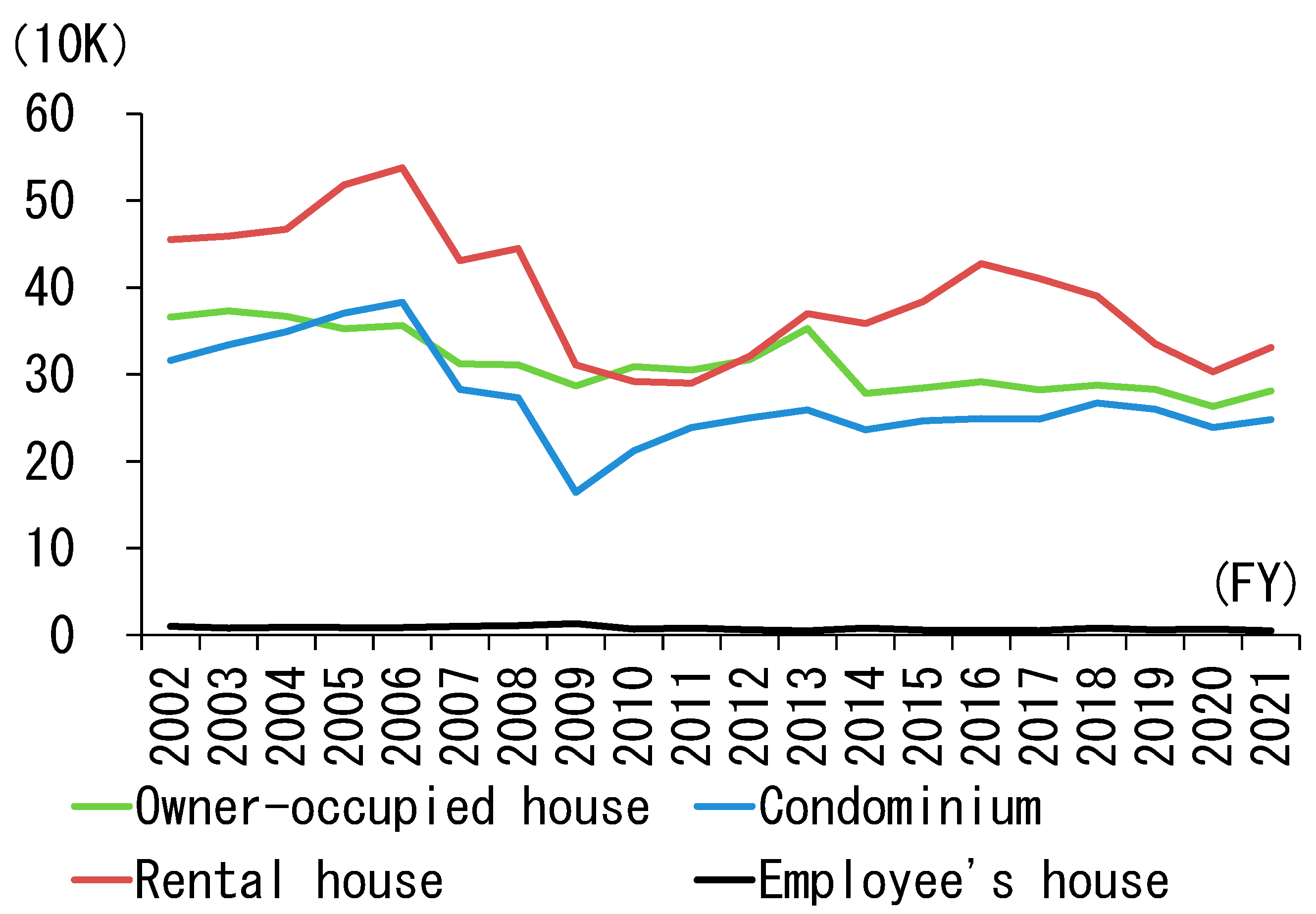

Figure 9 shows that the number of houses for rent remained the highest in most years from FY2002 to FY2021, followed by owner-occupied houses and condominiums.

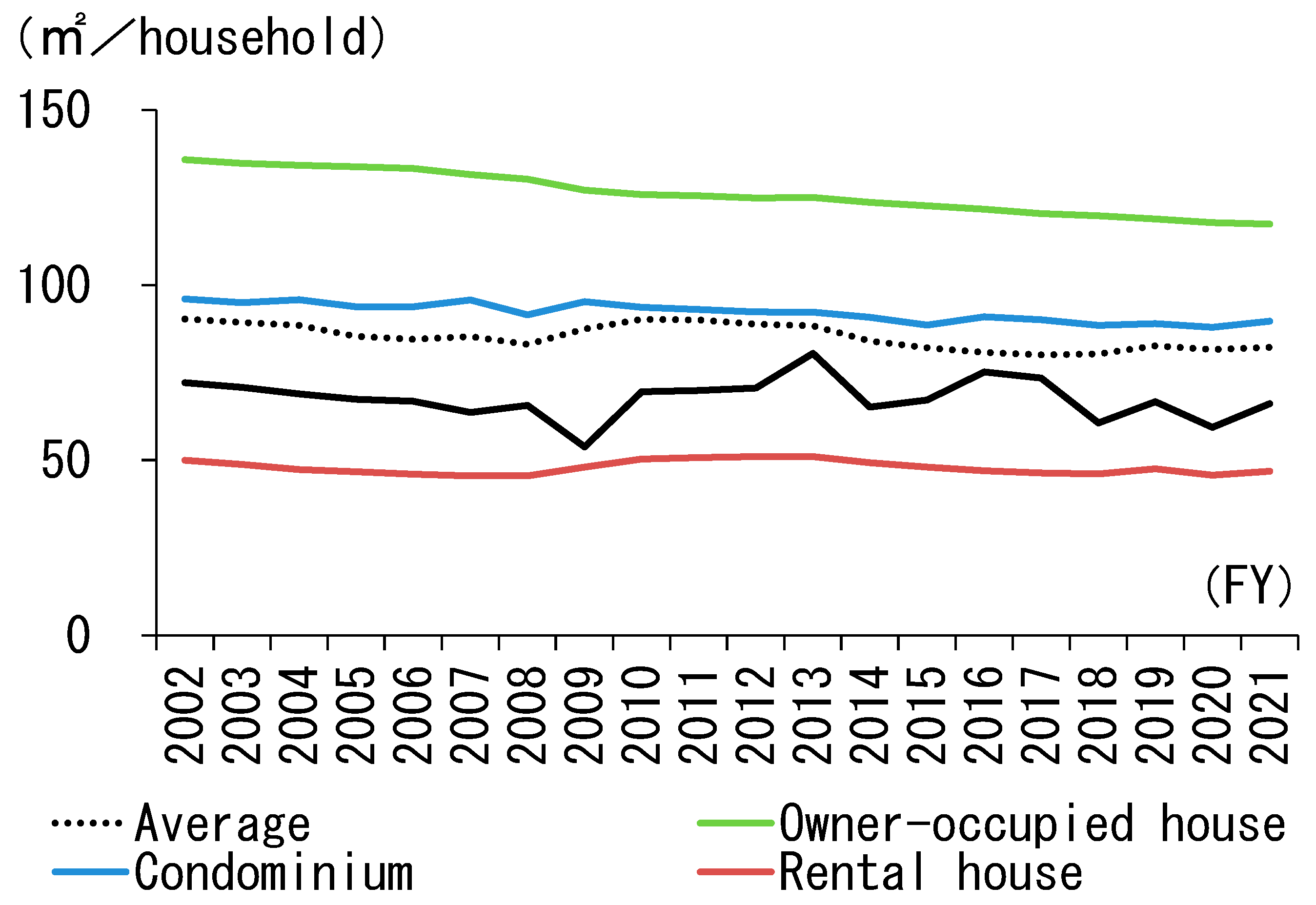

Figure 10 shows the trend of the total floor space per house by type of ownership. The floor space of rental houses remained at around 50 m

2, suggesting that these houses were newly built for small households, such as single households and couple households. In contrast, owner-occupied houses and condominiums are around 100 m

2-140 m

2, respectively, indicating that they are mainly for households that are raising children. According to the "Housing for Single Households" survey conducted by the Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, rental houses (housing complexes) account for about 60% of all housing ownership by single households until their 50s, and it is said that they prefer compact housing with a total floor space of about 45 m

2 [

6] for their dwellings. This can be seen as promoting a certain degree of new housing construction by middle-aged single households.

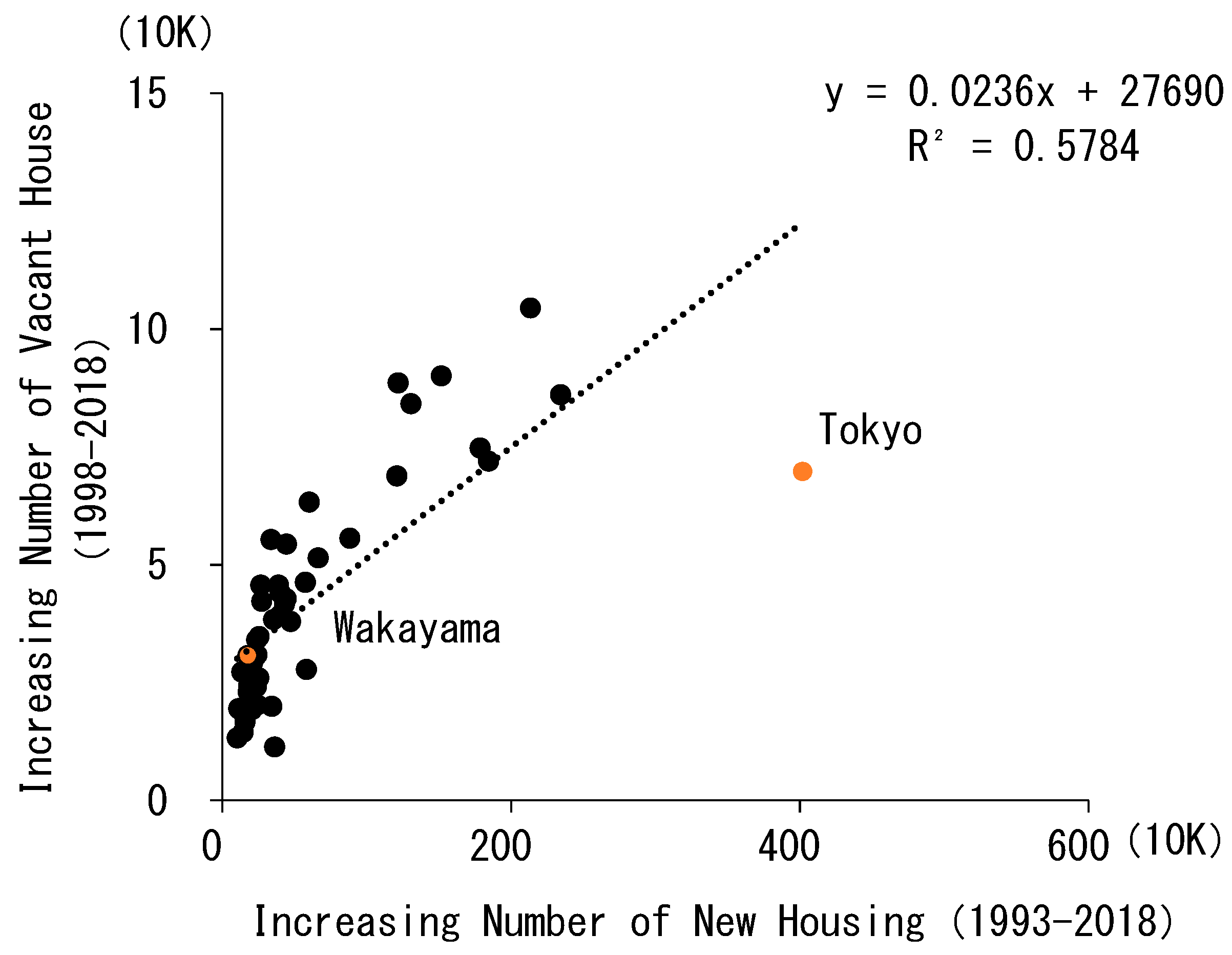

3.4. Relationship between Emergence of Vacant House and Newly Development

Figure 11 shows that despite the occurrence of vacant houses in all prefectures, new construction is progressing, and the higher the increase in new housing units, the higher the increase in vacant houses. This indicates that the utilization of vacant houses does not increase as the number of new houses increases. There has been a large increase in the number of new housing units, a small increase in the number of vacant houses in Tokyo, a small increase in the number of new housing units, and a large increase in the number of vacant houses in Wakayama Prefecture. In addition, while there is a certain correlation between the number of new housing units and the number of vacant houses, the relationship is weak when viewed on a national basis. It can be inferred that some areas are experiencing an increase in new housing regardless of the increase in the number of vacant

Houses due to regional characteristics such as inter-city competition for population acquisition.

4. Case study (Tokyo and Wakayama)

4.1. Household Trends by Family Type

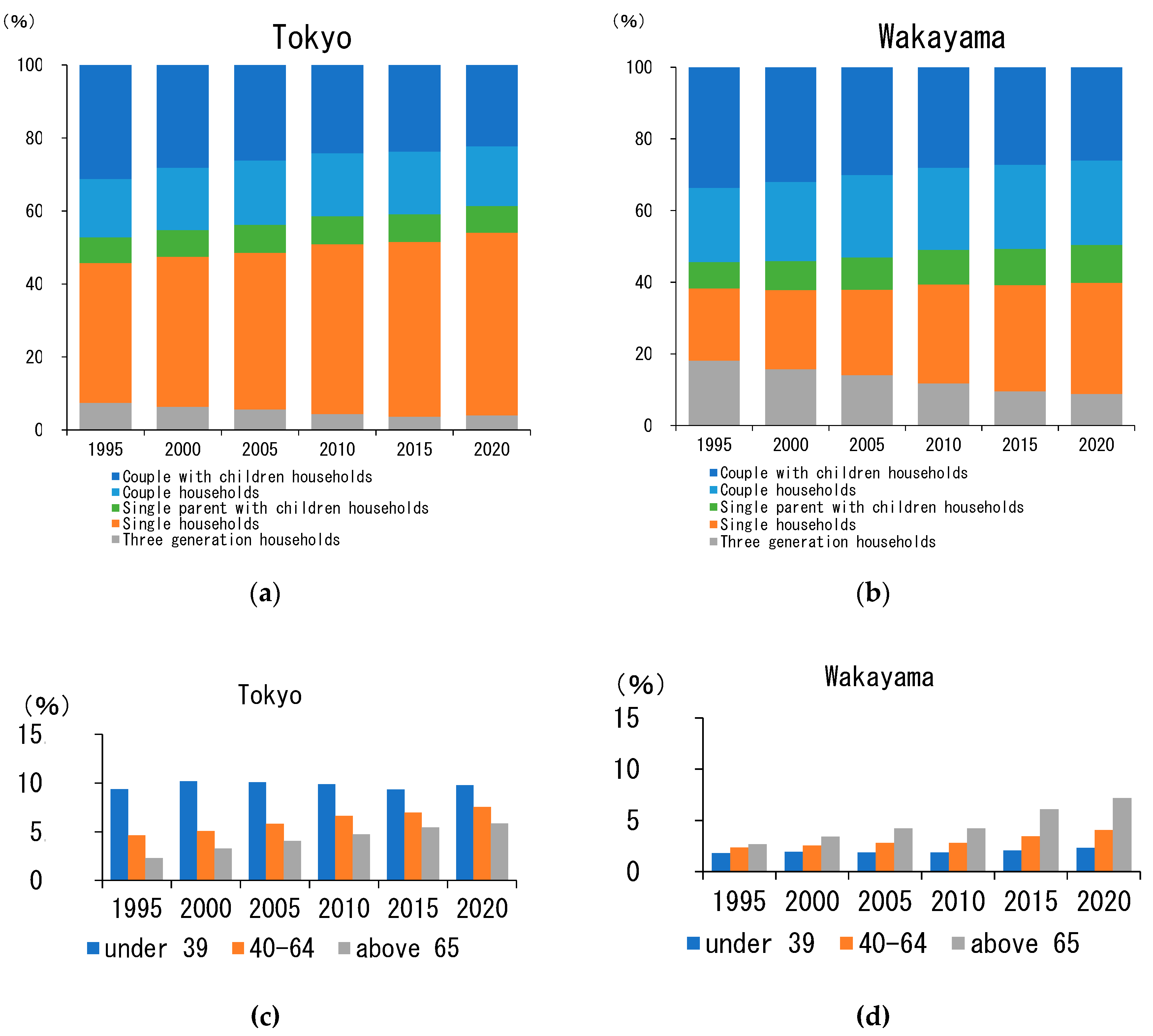

Figure 12(a)(b) shows the percentage of households by family type in Tokyo and Wakayama Prefecture. In both Tokyo and Wakayama Prefecture, three-generation households and households consisting of a couple and children have decreased, while single households, couple households, and households consisting of a single parent and children have increased.

Figure 12(c)(d) shows the increase in single households by age of the head of the household. In Tokyo, single households (aged under 39) (“young-aged single households” in the following) are the most numerous. In Tokyo, young-aged single households are the most numerous, with a constant increase or decrease. In Wakayama Prefecture, in contrast, elderly single households are the most numerous, and their number is increasing significantly.

While Tokyo and Wakayama Prefecture share a similar increase in the number of single households, the progression of single households is somewhat different. Tokyo has always had a higher percentage of single households than other prefectures because many single households are formed as a result of higher education and employment. However, with the declining birthrate and aging population, as well as the trend toward late marriage and nonmarriage, the number of young single households has reached its peak, and the number of middle-aged and elderly single households is increasing (Annotation A6 in

Appendix A).

In contrast, in Wakayama Prefecture, the proportion of couples with children households used to be higher; however, in 2015, the number of single households exceeded that of couples with children. Thus, the shift to single households is lagging behind compared to Tokyo.

4.2. Trends and Measures for Vacant Houses and Newly Constructed Housing

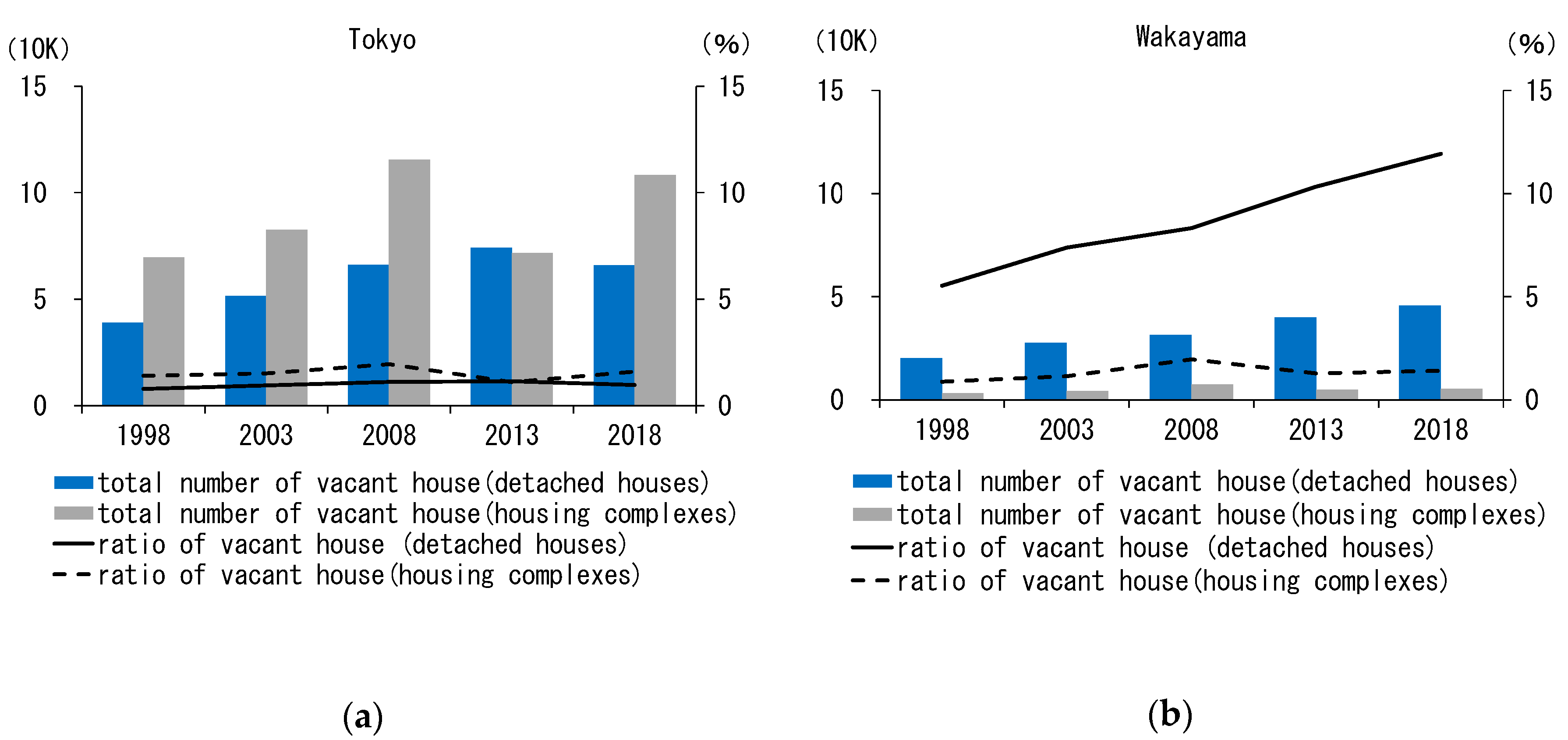

This difference in the percentage of households by family type is expected to create differences in the occurrence of vacant houses and the measures taken to deal with them. As seen in

Figure 13, the number of vacant houses in Tokyo has remained high for both detached housing and housing complexes.

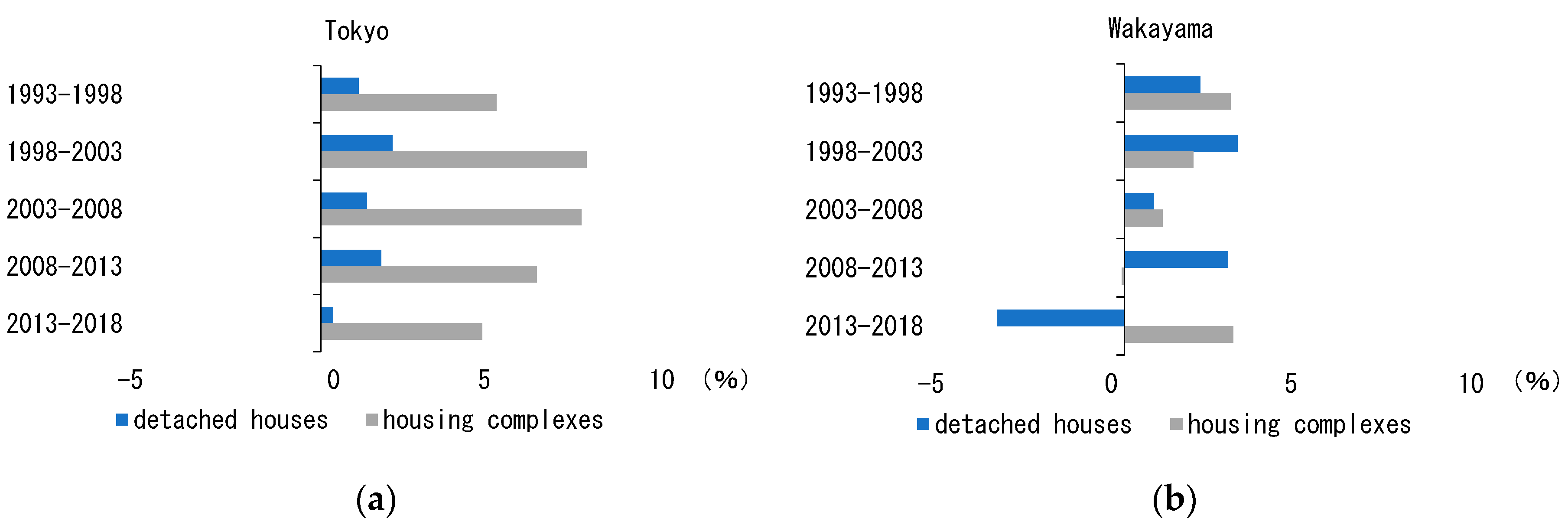

Figure 14 shows the rate of increase in the number of new housing units. In Tokyo, the housing growth rate for housing complexes is high and has been gradually decreasing since 1998. Comparing the two, it can be seen that while the number of vacant houses in housing complexes continues to increase without being utilized, new housing complexes are being built. In Tokyo, the housing stock for single households appears to be sufficient, as the city has for many years mainly supplied housing complexes for younger households (Annotation A7 in

Appendix A). However, the mismatch between the housing needs of middle-aged and older single-family households and the need for shared housing for a comfortable lifestyle has tended to lead to an increase in the number of new housing units (Annotation A8 in

Appendix A).

In Wakayama Prefecture, detached houses, which are designed for households consisting of couples with children, do not fit well with the needs of smaller households that do not have children to begin with and are more likely to be vacant at the time of inheritance. Although there were many periods when detached houses outnumbered housing complexes in terms of housing growth in Wakayama Prefecture, in the most recent period, 2013-2018, the rates were significantly negative for detached houses and positive for housing complexes. Despite the high rate of vacant houses, new construction is progressing because the housing stock in the area, where many houses have originally been built for three-generation households and for households consisting of a couple with children, has diverged from the needs of middle-aged single households and is not available on the secondary market. Moreover, condominiums are being developed in areas with little existing housing stock, such as in Wakayama Station, Japan Railway, and in Wakayama City Station, Nankai Railway.

5. Population, Households and Housing Trends (Setagaya Ward (Taishido) and Wakayama City (Central City))

In looking at the relationship between the occurrence of vacant houses and new housing construction at the district level, we will examine the future development potential of the compact city policies. In the following, we take Setagaya Ward (Taishido) and Wakayama City (central city area), which have the largest number of vacant houses in the metropolitan area, and for a regional city, as case studies, and provide an overview of the future forecast of vacant houses and new housing construction trends based on where middle-aged and elderly single households are located.

5.1. Case Study of Setagaya Ward (Taishido)

Figure 15 shows the outline drawing in Setagaya Ward (Taishido). The ward is a “bed town” of Tokyo, a “densely wooden district”, with an area of 1 km

2. The district has good access to transportation, with the Tokyu Denentoshi Line and the Tokyu Setagaya Line serving the area and National Highway 246 running parallel to it. The area is mainly residential but also has a thriving commercial district, with the Taishido Central Shopping Street and the complex facility called “Carrot Tower” in the station front. Showa Women's University is located in the southern part of the district, and there are many student living centers and residences.

Figure 16 shows that in Setagaya Ward (Taishido), both housing complexes and detached houses are dispersed and distributed in this district. As seen in the deteriorating municipal housing in Taishido 4-chome, this phenomenon will become more pronounced in apartment buildings. In addition, as this area is a densely wooded urban area, there are many narrow streets, and dilapidated single-family houses can be seen along the streets.

Figure 17 shows the location of housing complexes occupied by middle-aged single households in the district, and it can be seen that they are distributed in the Sangenjaya area. In the “Redevelopment Promotion District” (Taishido 4th block) of the station front, housing complexes for singles have been constructed by private developers since 2000. In addition, the “road widening project” by the Tokyo Metropolitan Housing Supply Corporation has resulted in the construction of a new housing complex for singles (Taishido 3

rd block). In contrast, new detached houses for singles, specifically terrace houses, are also being built along Chazawa Street.

Thus, in the same area, where land prices are relatively high, it is assumed that there is a relatively high demand for housing. However, single-family homes built during the period of rapid economic growth have a short useful life of 30 years and are reaching the point of renewal, and demand for aging single-family homes is low [

19]. In addition, the longer apartment buildings remain vacant, the more older buildings deteriorate and rents decline. This has been demonstrated to be especially true for apartment buildings with larger floor plans and those that are further away from the nearest station [

20]. For this reason, administrative measures to prevent long-term vacancy are important.

For example, when promoting housing near railroad stations, administrative support is required to purchase or rent (mainly single-family) houses from elderly people whose children have become independent and whose homes are larger than the number of household members, and to renovate these homes into houses for households with children who desire larger homes. Without such policies, houses (mostly single-family homes owned by the elderly) would become vacant and unutilized, leading to "city sponging," which is the spread of uninhabitable space in the city, a situation that would be at odds with the concept of a compact city. Relatively large single-family houses, mainly for nuclear families, could be divided into smaller parcels and converted into housing for middle-aged single households, but in this case, it would be necessary to develop housing represented by terrace houses that do not promote excessive subdivision of the land. In contrast, a certain amount of new housing for middle-aged single households is likely to be needed due to the shortage of the housing stock. Housing for middle-aged single households should be built and guided by the construction of apartment complexes, taking into account the high use and intensification of the area near the railroad.

5.2. Wakayama city (Central city) case study

Figure 18 summarizes the current status of Wakayama City (central city area). Wakayama City is a core city with major administrative functions as the prefectural capital, but it is also a bedroom community located within 60 km of Osaka. The central area of Wakayama City extends from east to west between Nankai Wakayama-shi Station and JR Wakayama Station and from north to south between Wakayama Castle and Honmachi, including Burakuri-cho. The area is also characterized by a well-developed underground shopping center in front of the station.

The area has a decentralized urban structure, with Wakayama Castle and City Hall in the south and Burakuri-cho, the largest shopping district in the prefecture, in the north. This urban structure is similar in many respects to that of other regional cities that are the prefectural capitals.

Figure 19 shows the distribution of apartment buildings and single-family houses occupied by elderly single households in Wakayama City (central city area). Single-family houses are also distributed in old urban areas, such as the Burakuri-cho shopping street in the central city center, as well as aging apartment buildings owned by the Urban Renaissance Agency located around Wakayama City Station on the Nankai Railway line. In these neighborhoods, these houses will inevitably become vacant within the next 20 years unless measures are taken to sell or renovate aging single-family houses for rental purposes.

Figure 20 shows apartment houses occupied by middle-aged single households in the district distributed along Keyaki Boulevard, a trunk road leading from JR Wakayama Station. They are intricate housing complexes built by a private developer as part of an urban redevelopment project at the west exit of the station and are designed for elderly people, single adults, and households raising children. In contrast, single-family homes occupied by middle-aged single households are mostly distributed in the old urban area in front of Wakayama City Station on the Nankai Railway, and it can be inferred that many of these homes were inherited from parents and are occupied solely by their children. Although there is a possibility that the number of such detached houses will increase in the future, there is a high possibility that they will be abandoned due to mismatches in the age and layout of the building. Thus, middle-aged single-family households are also a factor in the occurrence of vacant detached houses and the construction of new apartment buildings in the area.

It is desirable to take measures before single-family homes owned by middle-aged and single-family households are abandoned and to provide them to households raising children. In order to provide these units to households raising children, a certain degree of renovation is required, and if the units are to be rented, restoration to their original condition is obligatory in principle. In response to this, it would be effective to create a system that allows tenants to make modifications to suit their lifestyles in exchange for bearing the cost of the modifications or to lower the rent of these properties [

21].

In this case, it may be possible to create a system in which the property is offered as a rental property and the tenant bears the cost of renovation or to create a housing cycle in which the tenant can be offered a discount for the renovation after the contract period ends. In addition, since the number of households is expected to decline, the active removal of some of these units may be necessary (Annotation A9 in

Appendix A).

In contrast, the introduction of new apartment complexes for middle-aged single households should be considered in the central city area as well as in front of train stations, and the enhancement of common spaces, including open spaces in the neighborhood, the creation of communities through neighborhood associations and local governments, tax incentives for housing purchases, and the availability of mortgage loans will be important points for creating attractive housing for these households [

22]. The availability of tax incentives and housing loans for home purchases are important points. Through these measures, the idea of consolidating housing in multiple locations centered on public facilities such as railroads, central city areas, and prefectural government offices and connecting them by public transportation will be essential in the future.

6. Discussion

This paper examined the state of compact cities in Japan. Focusing on changes in family formation and smaller household size, in addition to a declining and aging population, this paper outlines the occurrence of vacant houses and new housing construction trends. The results showed that in all prefectures, the number of households, especially single households, increased due to the downsizing of households. It was inferred that the increase in the number of elderly single households generates vacant houses, while middle-aged single households are one factor that promotes the construction of new housing.

In the central Tokyo metropolitan area, the smaller size of households, especially middle-aged single households, promoted the construction of new apartment buildings. Despite the existence of housing stock originally intended for single households, the housing demand of middle-aged single households does not match the housing demand of middle-aged single households, probably due to the large number of student rental housing units and qualitative issues (Annotation A10 in

Appendix A). It was inferred that the supply of such new housing for middle-aged single households would delay the elimination of vacant housing and lead to stagnation in the housing cycle.

Similarly, in Wakayama Prefecture, located in the suburbs of the Osaka area, the increase in the number of middle-aged single households tended to promote the construction of new apartment buildings. Wakayama Prefecture has always had a large number of detached houses for other households (three generations living together) and households consisting of a couple and their children. This tends to increase the number of newly built apartment buildings, which do not match the housing needs of middle-aged single households. Therefore, without some administrative measures, it was expected that the reuse of the housing stock would not progress and the number of vacant houses would continue to increase.

Internationally, the trend of smaller households in Japan is similar to that in Scandinavia and higher than anywhere else in the world [

23]. The reason for this is said to be Japan’s rapidly aging population, and it is likely that these household trends are changing the balance of housing supply and demand. In addition, as indicated in this paper, the number of middle-aged single households has been increasing remarkably in recent years due to the trend toward nonmarriage, and it will be necessary to keep a close eye on their trends in the future. In the U.S., although the number of single-person households has increased less than in Japan, the percentage of homebuyers has risen to 10% for single men and 21% for single women, with the two together accounting for about one-third of the home sales market [

24]. In the Paris metropolitan area, households with a large number of members per household tend to live in the peri-urban area in search of relatively spacious housing, while smaller households tend to live in densely populated urban centers [

25]. This indicates that it is essential for Japan to shift its housing policy to accommodate the trend toward smaller households in the future. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in large cities, but based on the results of this paper, it is expected that the number of single households will increase significantly in the peri-urban area as well.

In both Setagaya-ku (Taishido) and Wakayama City (central city area), we found that middle-aged and elderly single households are distributed evenly throughout the district. This fact can be expected to lead to a large number of vacant houses within 20 years in the future, conflicting with the construction of new housing. Concerning housing policies that respond to smaller household sizes in both districts, we would like to examine next how compact cities should be in large cities and suburbs.

Setagaya ward (Taishido) still has a relatively high housing demand due to its location in the central Tokyo metropolitan area; however, many of the wooden detached houses built during the high economic growth period have become unusable and are in need of renewal. The demand for aging wooden detached houses is low and supportive measures may be necessary to prevent them from becoming vacant. For example, buying a detached house owned by elderly single households and renting them out at a discount to households with children or students as share-houses could promote the housing cycle. It would also be necessary to direct the construction of residences for elderly single households to the nearby station area.

It is also essential to supply new high-quality rental condominiums to accommodate the growing number of middle-aged single households. In doing so, priority could be given to the construction and advanced use of complex housing for small households such as single households in conjunction with the redevelopment of the area in front of the station. In addition, the concept of serviced senior housing or collective housing (Annotation 11,

Appendix A) as a new type of housing for single households has potential. Based on the above, a compact city will become more realistic by consolidating residential areas around train stations.

In contrast, in areas such as Wakayama city (central city), located in the peri-urban Osaka metropolitan area where many detached houses have been built for households with children, there is a high possibility that these homes will become vacant due to the age of the buildings and the mismatch in the size and floor plans desired by those looking for smaller households. Therefore, it will be essential to accumulate skills and knowledge and create a plan to renovate detached houses owned by elderly single households for households with children. In addition, in areas where the population is expected to decline, the active removal of vacant houses in disadvantaged areas should also be taken into consideration.

In contrast, a certain amount of new construction of high-quality housing is necessary to accommodate the increase in the number of middle-aged single households. In addition, future housing construction should be designed to allow for conversion to other uses to accommodate future reductions in the number of households and changes in industry. In this area, which has developed around the railroad, shopping district, and government office buildings, it is not realistic to direct residential areas to be constructed in the vicinity of the railroad. Rather, it is important to consolidate residential areas in multiple locations and connect them by public transportation.

7. Conclusion

From an international perspective, Japan's urban contraction is said to be characterized by rapid population decline and aging. As a result, national policies appear to be focused on correcting population disparities among regions and on compact city policies to accommodate the aging of the population. This study proposes the future of compact cities from the perspective of household downsizing and housing policy. In addition to population decline and aging, it is essential for compact cities to pay attention to the downsizing and diversification of households against the backdrop of changes in family formation, and it will become even more important to consider housing policy from a demographic, sociological approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and Y.O.; methodology, M.M. and Y.O.; software, M.M.; validation, Y.O. and K.I.; resources, M.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., writing—review and editing, Y.O. and K.I.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, Y.O. and K.I.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, K.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Joint Research Program No.1275 at CSIS, UTokyo (ZMap TOWN 2 2022 Shape Ver., Data set of Tokyo and Wakayama prefecture; People Flow Project, People Flow Data set of Tokyo and Wakayama prefecture).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Annotation A1. The OECD defines the population density of urban sites at three density levels: high density (more than 5,000/km2), medium density (more than 2,500 and less than 4,900), and low density (less than 2,500/km2). Of these, Setagaya Ward and Wakayama City, which are the focus of this report, fall into the high-density and low-density categories, respectively. The results of this report may serve as a reference for cities with similar density levels in other developed countries.

Annotation A2. Aomori City is an example of a city that has failed to halt the sprawl of its suburbs and the decline of its central city. Aomori City is known for being the first city in Japan to write the term "compact city" in its urban planning master plan (1999). The city did not make much progress in revitalizing its central city area because it was unable to stop large commercial facilities from moving into the suburbs against the backdrop of further motorization, land prices in the suburbs being lower than in the city center even after the collapse of the economic bubble (1986-1991), and the continued creation of large vacant lots due to the decline of agriculture.

Annotation A3. Japan's three major metropolitan areas are the Tokyo metropolitan area, the Osaka metropolitan area, and the Nagoya metropolitan area. For the purposes of this paper, the Tokyo metropolitan area is defined as Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama prefectures; the Osaka metropolitan area as Osaka, Hyogo, Kyoto, and Nara prefectures; and the Nagoya metropolitan area as Aichi, Gifu, and Mie prefectures.

Annotation A4. This database, operated by the Center for Spatial Information Science at the University of Tokyo, uses statistical data released as open data, aggregate results of existing person-trip survey data, building data, and other data to create a synthetic population that simulates people's typical daily activities. It should be noted that this is not the location data of real people. The pseudo-population data were estimated from information such as household composition, age, gender, employment status, and the addresses of individuals based on demographic data from the census and assigned to Zenrin's building data.

Annotation A5. In this paper, vacant houses are defined as housing where the occupying household has been absent for a long period of time due to relocation, hospitalization, etc., or housing that is scheduled to be demolished for rebuilding, etc. (In other words, this research identify vacant houses are other than secondary vacant houses (vacation homes) and vacant houses for rent or sale.)

Annotation A6. The Research Institute of the Special Ward Mayors' Association (2020): Analysis of Subregional Population and Households in Special Wards and Current Status and Issues of Mature Singles estimates that mature singles in special ward areas will be 35-49 years old (6.0%), 50-64 years old (3.9%) and 65 years old or older (5.2%) in 2020, and 35-49 years old (7.0%) in 2035. (0.0%), 50-64 (6.0%), and 65 and older (6.7%) in 2035.

Annotation A7. A minimum living area level (the area of housing essential as the basis for a healthy and cultured residential life, based on the number of household members) is 25 m2 or higher for housing complexes.

Annotation A8. Housing complexes of 40m2 or higher (urban type) to 55m2 or higher (general type), which is the induced living area level (the area of housing considered necessary to accommodate diverse lifestyles as a precondition for realizing affluent residential life, depending on the number of household members).

Annotation A9. The Act on Partial Revision of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Promotion of Measures against Vacant Houses, etc., (2023) promoted the removal of specified vacant houses and made it possible for the mayor of a municipality to give guidance and recommendations. In addition, the special exception for residential property tax (reduced to 1/6, etc.) was lifted for unmanaged vacant houses that received a recommendation.

Annotation A10. In Setagaya ward, about 10% of the housing units are below the minimum occupancy level and about 40% are above the minimum occupancy level and below the induced occupancy level as of 2018, with 1K housing for students accounting for half of the housing units.

Annotation A11. Collective houses are communal residences originating in Scandinavia, where people live together while maintaining individual autonomy. It has communal spaces such as a kitchen, dining room, kids' space, and vegetable garden and incorporates common meals two to three times a week, proposing a multi-generational, multi-family type of residence.

References

- Torrens, J.; Westman, L.; Wolfram, M.; Broto, V.; Barnes, J.; Egermann, M.; Ehnert, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Fratini, C.; Hakansson, I.; Holscher, K.; Huang, P.; Raven, R.; Sattlegger, A.; Schmidt-Thome, K.; Smeds, E.; Vogel, N.; Wangel, J.; and Wirth, T.; Advancing urban transitions and transformations research, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 2021, Volume 41, 102-105. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment, OECD Green Growth Studies, 2021, OECD Publishing.

- Buhnik, S.: From Shrinking Cities to Toshi no Shukusho: Identifying Patterns of Urban Shrinkage in the Osaka Metropolitan Area, Berkeley Planning Journal, 2010, Volume 23, No 1, 132-155.

- Yabuki, K.; Utilization of Vacant Residential Lots in Flint, USA, Journal of housing, 2017, Volume 66, No 9, 40-48. (in Japanese).

- Sorensen, A.; Land readjustment and metropolitan growth: an examination of suburban land development and urban sprawl in the Tokyo metropolitan area, Progress in Planning, 2000, Volume 53, 217-330. [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.; Retail planning in Japan: Implications for city centres, Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, Henry Stewart Publications, 2017, Volume 10, No 4, 357-368.

- Balaban, O.; and Puppim, de Oliveira.; Finding sustainable mobility solutions for shrinking cities: the case of Toyama and Kanazawa, Journal of Place Management and Development, 2021, Volume 15, No 1, 20-39.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan.; Significance and Role of the Site Optimization Plan, Implementation of Compact plus Network City, Available online: < https://www.mlit.go.jp/en/toshi/city_plan/compactcity_network2.html > (accessed on 15th February, 2024) (in Japanese).

- Toyama City.,; The Site Optimization Plan, Available online: < https://www.city.toyama.lg.jp/shisei/seisaku/1010738/1011468/1006115.html> (accessed on 16th February, 2024) (in Japanese).

- Masuda, M.; and Akiyama, H.; Recent trends in vacant house research in Japan, Journal of Geographical Space, 2010, Volume 13, No 1, 1-26. (in Japanese).

- Kubo, T.; and Yui, Y.; The Rise in Vacant Housing in Post-growth Japan, Housing Market, Urban Policy, and Revitalizing Aging Cities, Springer, Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences, 2020, 175pp.

- Van, H.; Ha, T.; Asada, T.; and Arimura, M.; Vacancy Dwellings Spatial Distribution-The Determinants and Policy Implications in the City of Sapporo, Japan, Journal of Sustainability, 2022, Volume 14, 12427. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, H.; and Phelps, N.; Diversity in decline: The changing suburban fortunes of Tokyo Metropolis, Cities, 2020, Volume 103, 102693. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan.; National census. (in Japanese).

- Nishiyama, H. A Problem of Vacant Housing in Local Cities: Utsunomiya City, Tochigi Prefecture Case Study, Springer, 2020, 123-146.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan.; Housing and Land Survey. (in Japanese).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan.; Survey of construction starts, 2023 (in Japanese).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan.; Report of Statistics on Building Construction. Time-series data. (in Japanese).

- Perez, J.; Fusco, G.; and Sadahirio, Y.; Population and Morphological Change: A Study of Building Type Replacements in the Osaka-Kobe City-Region in Japan, Geographical Analysis, 2024, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Baba, H.; and Shimizu, C.; The impact of apartment vacancies on nearby housing rents over multiple time periods: application of smart meter data, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 2022, Volume 16, No 7, 27-41. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, H.; Resolution of Vacant Housing Through Social Business: Kominka Renovation Business by Nakagawa Jyuken Corp, Springer, 2022, 149-160. [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; and Mashita, M.; Why the Rise in Urban Housing Vacancies Occurred and Matters in Japan, Springer, 2020, 3-22.

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.; Table7-32, Number and Percentage of General Households by Type of Household in Major Countries: Latest Year, 2023 Available online: <https://www.ipss.go.jp/syoushika/tohkei/Popular/Popular2023RE.asp?chap=7> (accessed on 5th February, 2024) (in Japanese).

- Klinenberg, E.; Going Solo, The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone, Penguin Books, 2012.

- Fouchier, V. “Urban sprawl, density and mobility in case of Paris Region”, French National Territorial Planning Agency, Paris, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).