Submitted:

20 March 2024

Posted:

21 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

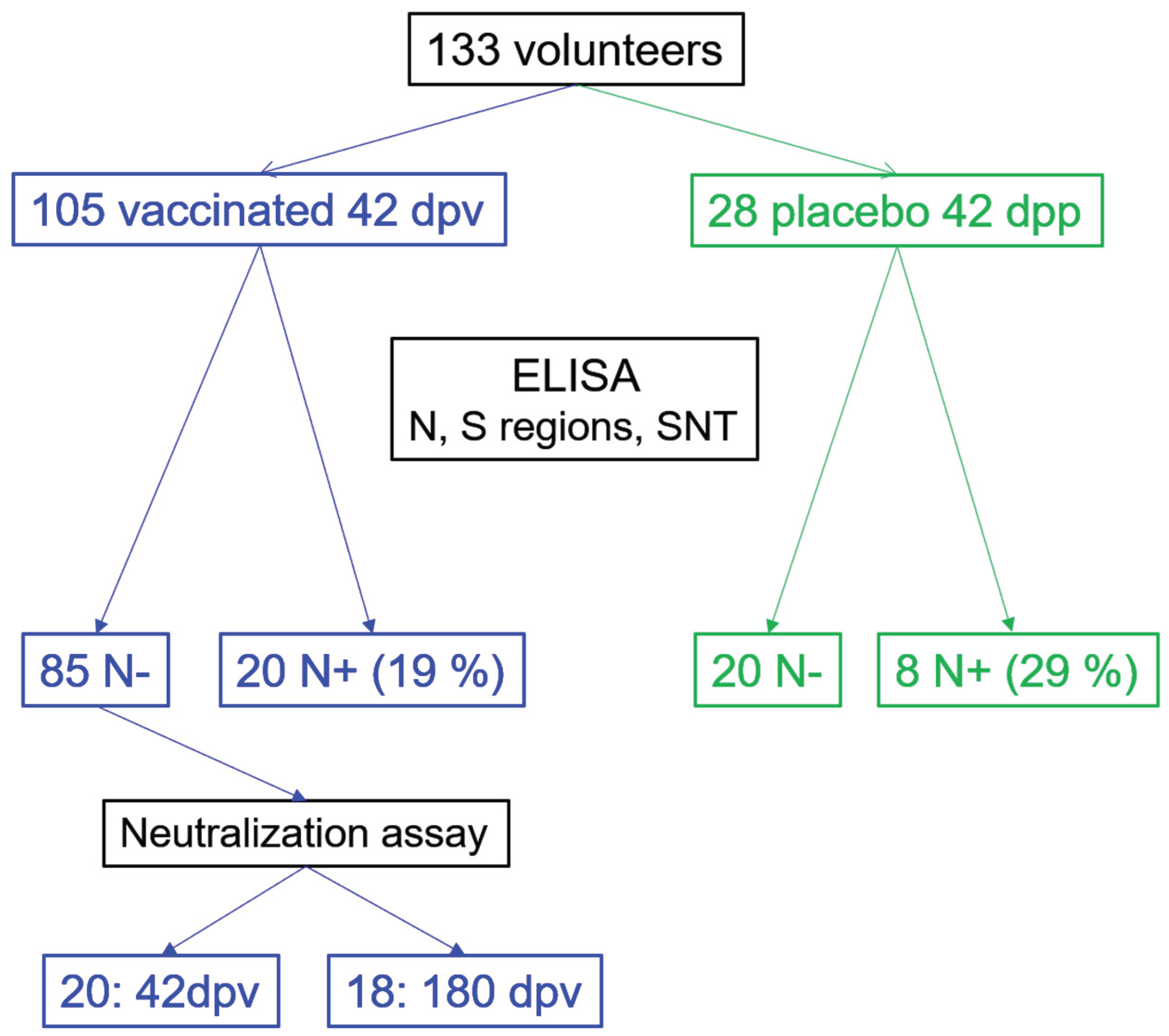

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Serum Recollection

2.2. Antigens

2.3. ELISA Reactivity

2.4. Surrogate Neutralization Test (SNT) Based on ACE2 Blocking Adsorption Immunoassay

2.5. Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

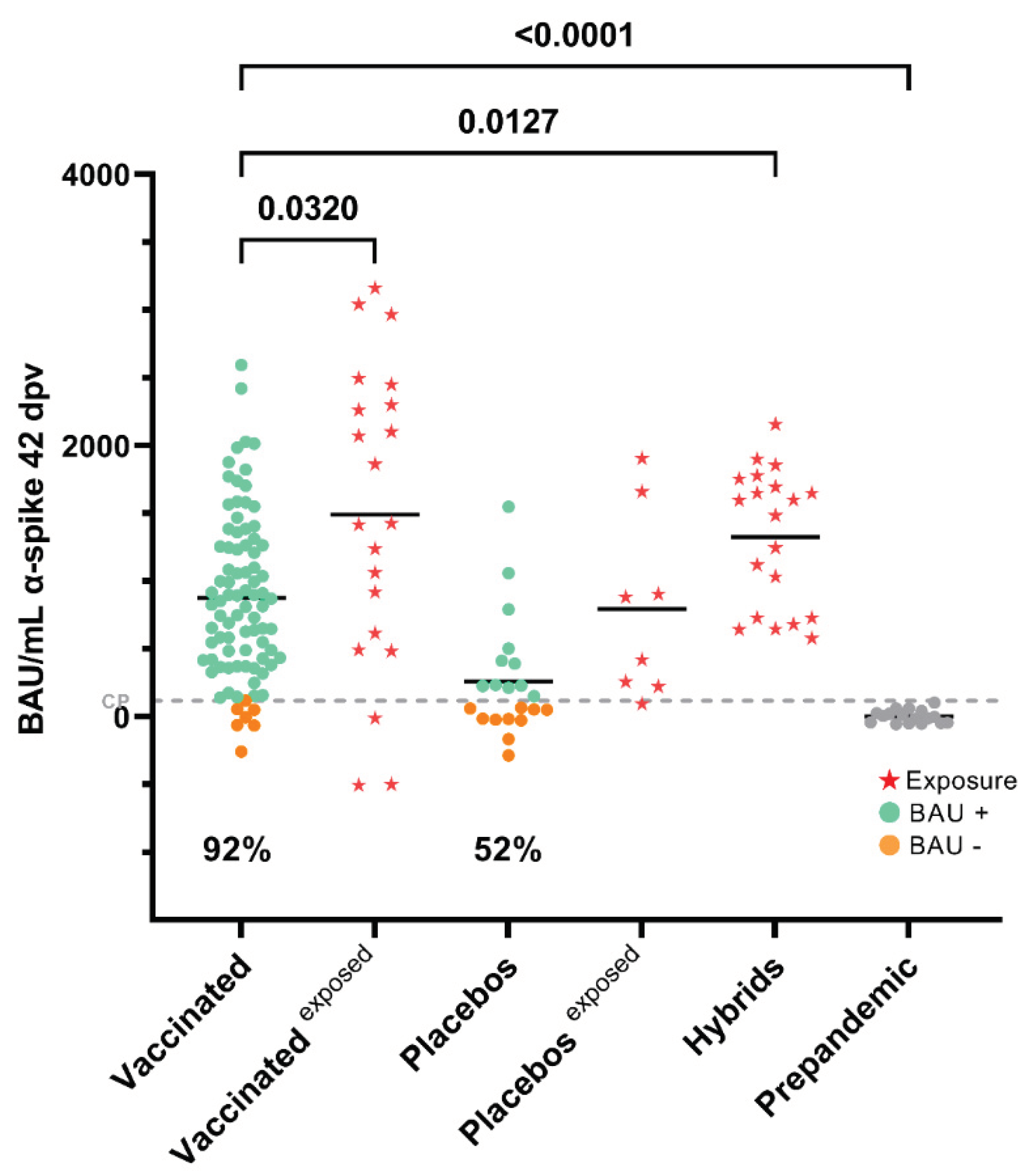

3.1. Seroconversion Rates in Non-Exposed Vaccinated Individuals in the Clinical Trial

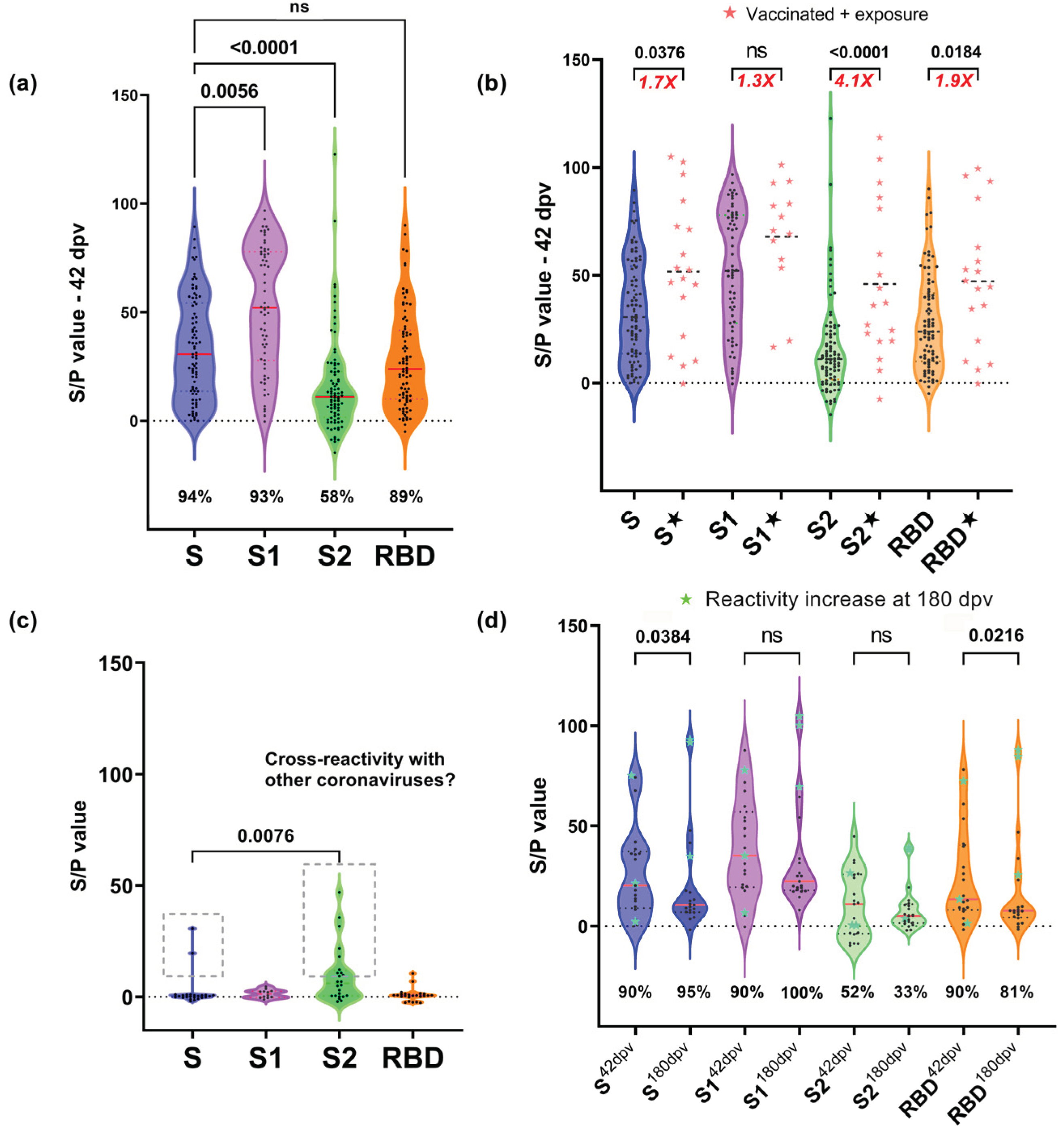

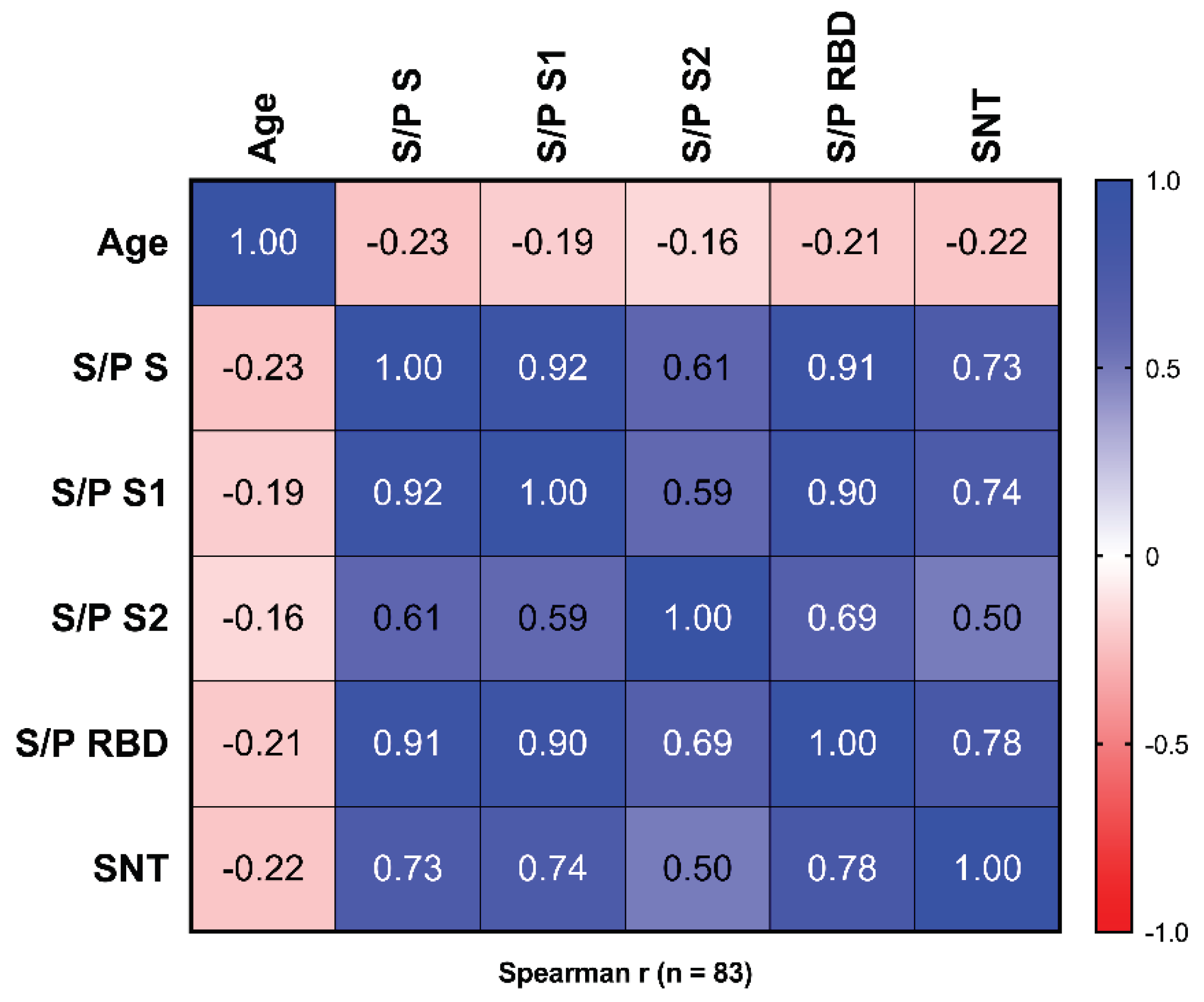

3.2. Reactivity to Different Regions of SARS-CoV-2 S

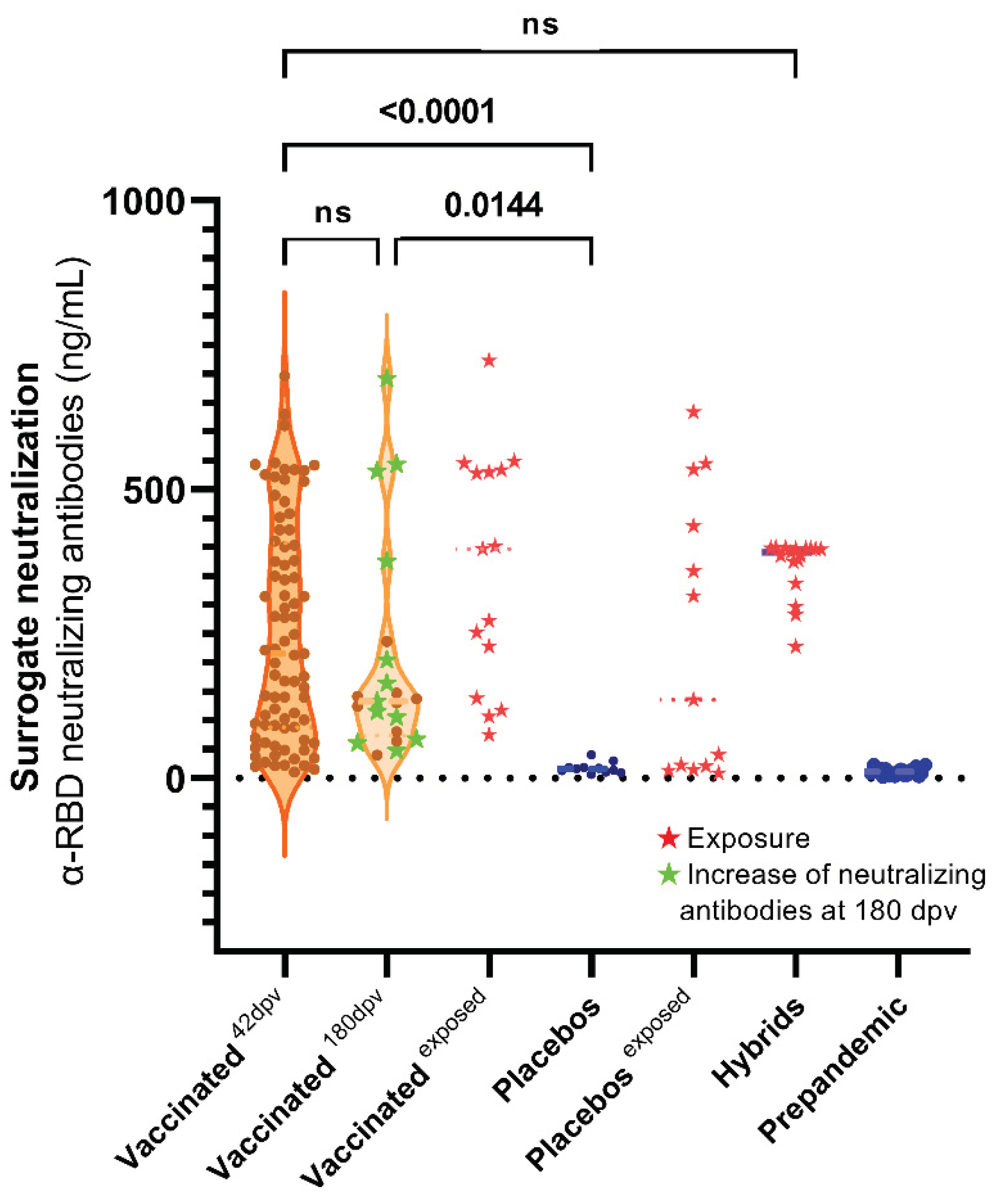

3.3. Surrogate Neutralization Test (SNT)

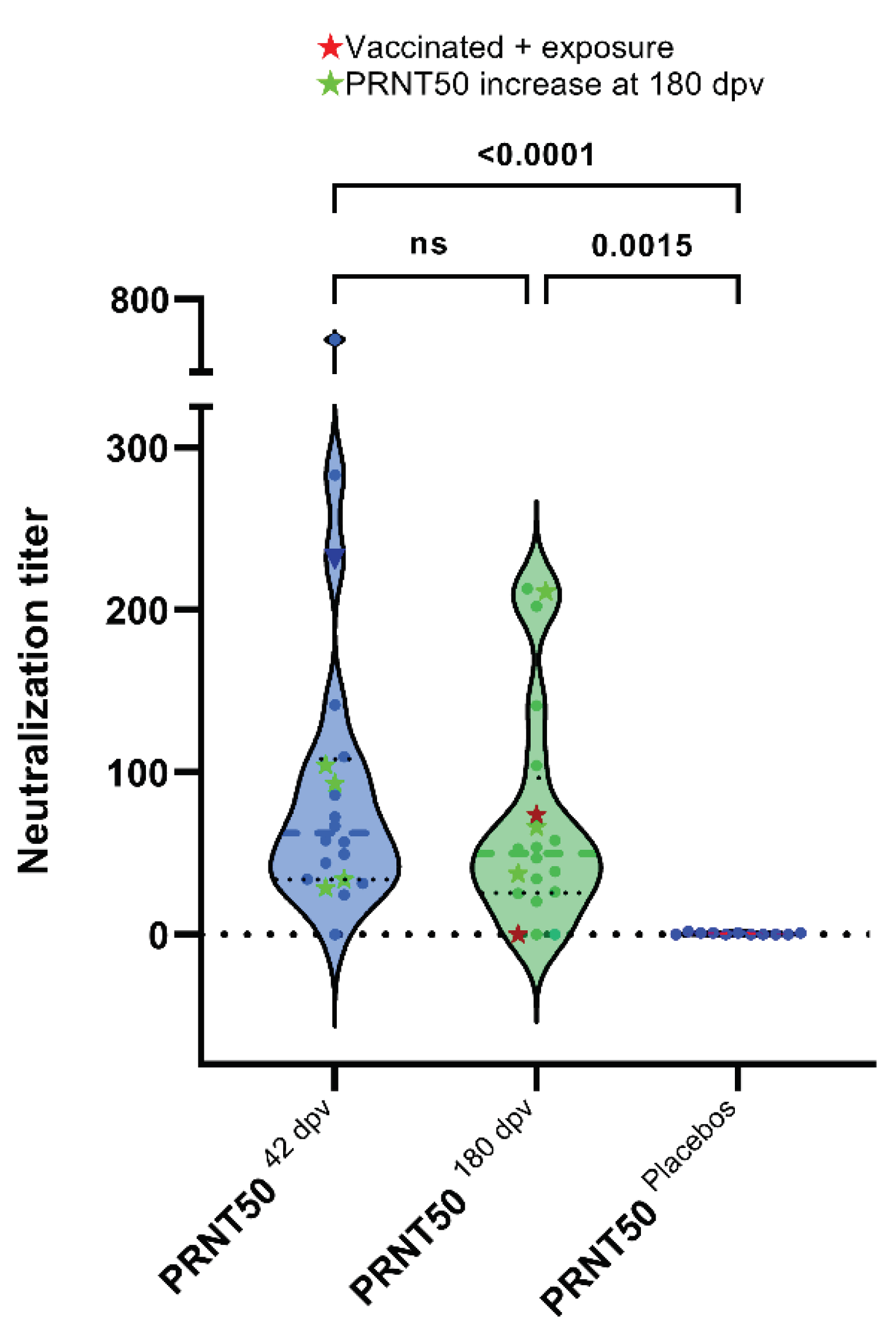

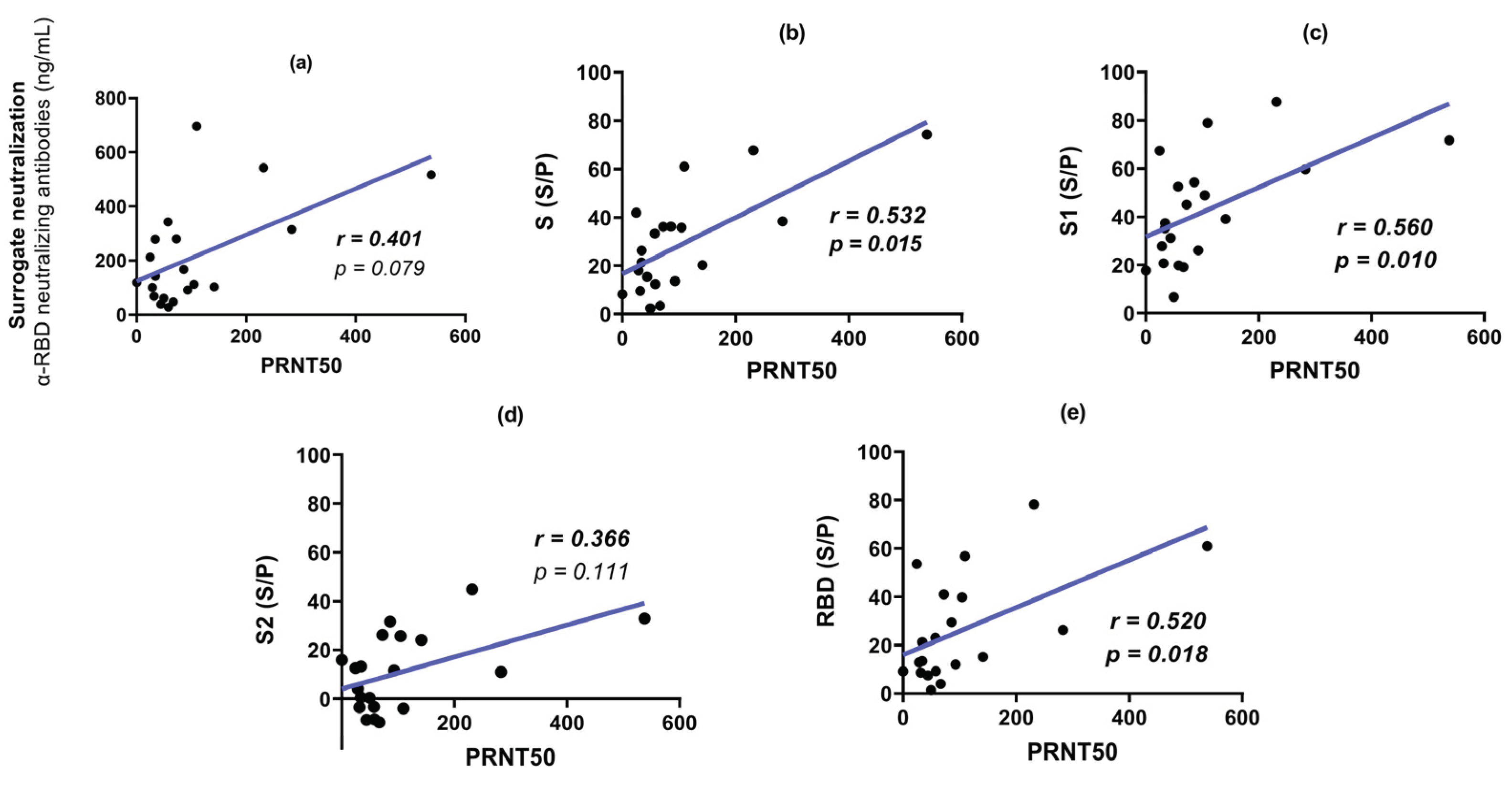

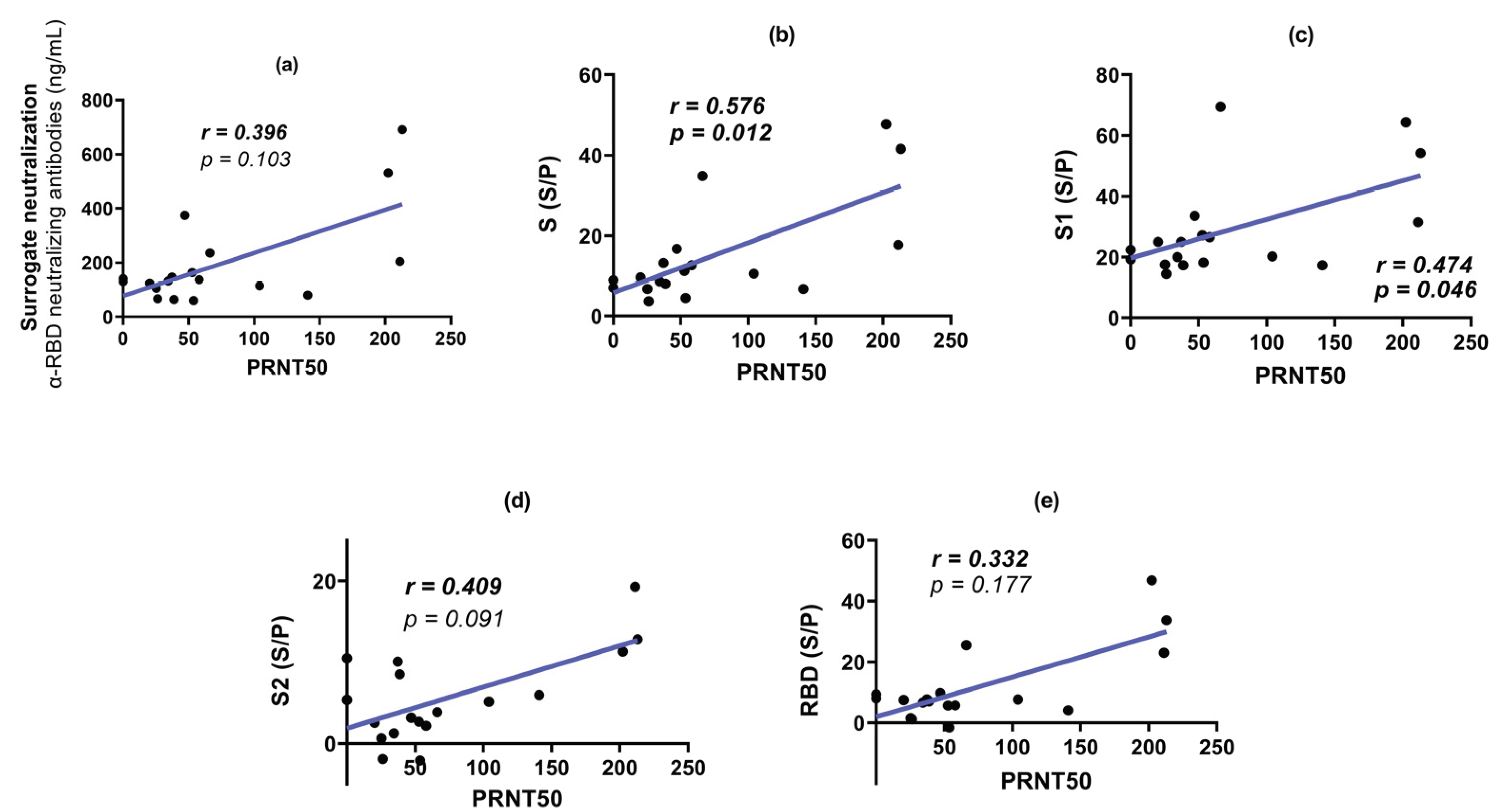

3.4. Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT50)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, R.M.; Sorensen, R.J.D.; Pigott, D.M.; Bisignano, C.; Carter, A.; Amlag, J.O.; Collins, J.K.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Allorant, A.; et al. Estimating Global, Regional, and National Daily and Cumulative Infections with SARS-CoV-2 through Nov 14, 2021: A Statistical Analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 2351–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global Impact of the First Year of COVID-19 Vaccination: A Mathematical Modelling Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V’kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus Biology and Replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Niu, S.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, G.; Qiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, K.Y.; et al. Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2. Cell 2020, 181, 894–904.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Niu, Y.; Lou, Y.; Wang, H. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Biosynthesis, Structure, Function, and Antigenicity: Implications for the Design of Spike-Based Vaccine Immunogens. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, A.K.; Pymm, P.; Esterbauer, R.; Dietrich, M.H.; Lee, W.S.; Drew, D.; Kelly, H.G.; Chan, L.J.; Mordant, F.L.; Black, K.A.; et al. Landscape of Human Antibody Recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain. Cell Rep 2021, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, P.; Mi, D.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Guo, R.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; et al. Characterization of Spike Glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on Virus Entry and Its Immune Cross-Reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, H.; Sterling, S.M.; Walsh, R.M.; Rawson, S.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Chen, B. Distinct Conformational States of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Science (1979) 2020, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Niu, P.; Qin, K.; Jia, W.; Huang, B.; Zhang, S.; Lan, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structural Definition of a Neutralization Epitope on the N-Terminal Domain of MERS-CoV Spike Glycoprotein. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; Mclellan, J.S. Cryo-EM Structure of the 2019-NCoV Spike in the Prefusion Conformation. Science (1979) 2019, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.; Canziani, G.A.; Carter, E.P.; Chaiken, I. The Case for S2: The Potential Benefits of the S2 Subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein as an Immunogen in Fighting the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claro, F.; Silva, D.; Pérez Bogado, J.A.; Rangel, H.R.; de Waard, J.H. Lasting SARS-CoV-2 Specific IgG Antibody Response in Health Care Workers from Venezuela, 6 Months after Vaccination with Sputnik V. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 122, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahla, R.E.; Tomas-Grau, R.H.; Cazorla, S.I.; Ploper, D.; Vera Pingitore, E.; López, M.A.; Aznar, P.; Alcorta, M.E.; Vélez, E.M. del M.; Stagnetto, A.; et al. Long-Term Analysis of Antibodies Elicited by SPUTNIK V: A Prospective Cohort Study in Tucumán, Argentina. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 2022, 6, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claro, F.; Silva, D.; Rodriguez, M.; Rangel, H.R.; de Waard, J.H. Immunoglobulin G Antibody Response to the Sputnik V Vaccine: Previous SARS-CoV-2 Seropositive Individuals May Need Just One Vaccine Dose. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 111, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Elslande, J.; Oyaert, M.; Lorent, N.; Vande Weygaerde, Y.; Van Pottelbergh, G.; Godderis, L.; Van Ranst, M.; André, E.; Padalko, E.; Lagrou, K.; et al. Lower Persistence of Anti-Nucleocapsid Compared to Anti-Spike Antibodies up to One Year after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspe, R.C.; Sulbaran, Y.; Loureiro, C.L.; Moros, Z.C.; Marulanda, E.; Bracho, F.; Ramirez, N.A.; Canonico, Y.; D’Angelo, P.; Rodriguez, L.; et al. Detection of the Omicron Variant of SARS-CoV-2 in International Travelers Returning to Venezuela. Travel Med Infect Dis 2022, 48, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Dolzhikova, I. V.; Shcheblyakov, D. V.; Tukhvatulin, A.I.; Zubkova, O. V.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Kovyrshina, A. V.; Lubenets, N.L.; Grousova, D.M.; Erokhova, A.S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of an RAd26 and RAd5 Vector-Based Heterologous Prime-Boost COVID-19 Vaccine: An Interim Analysis of a Randomised Controlled Phase 3 Trial in Russia. The Lancet 2021, 397, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, I.; Roy, P. Sputnik V COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate Appears Safe and Effective. The Lancet 2021, 397, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Dolzhikova, I. V.; Zubkova, O. V.; Tukhvatullin, A.I.; Shcheblyakov, D. V.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Grousova, D.M.; Erokhova, A.S.; Kovyrshina, A. V.; Botikov, A.G.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an RAd26 and RAd5 Vector-Based Heterologous Prime-Boost COVID-19 Vaccine in Two Formulations: Two Open, Non-Randomised Phase 1/2 Studies from Russia. The Lancet 2020, 396, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Dolzhikova, I. V.; Zubkova, O. V.; Tukhvatullin, A.I.; Shcheblyakov, D. V.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Grousova, D.M.; Erokhova, A.S.; Kovyrshina, A. V.; Botikov, A.G.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an RAd26 and RAd5 Vector-Based Heterologous Prime-Boost COVID-19 Vaccine in Two Formulations: Two Open, Non-Randomised Phase 1/2 Studies from Russia. The Lancet 2020, 396, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiolet, T.; Kherabi, Y.; MacDonald, C.J.; Ghosn, J.; Peiffer-Smadja, N. Comparing COVID-19 Vaccines for Their Characteristics, Efficacy and Effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and Variants of Concern: A Narrative Review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2022, 28, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimeglio, C.; Herin, F.; Martin-Blondel, G.; Miedougé, M.; Izopet, J. Antibody Titers and Protection against a SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Journal of Infection 2022, 84, 248–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, W.N.; Hou, Y.J.; Johnson, N. V.; Delidakis, G.; Kim, J.E.; Javanmardi, K.; Horton, A.P.; Bartzoka, F.; Paresi, C.J.; Tanno, Y.; et al. Prevalent, Protective, and Convergent IgG Recognition of SARS-CoV-2 Non-RBD Spike Epitopes. Science (1979) 2021, 372, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lai, D. yun; Zhang, H. nan; Jiang, H. wei; Tian, X.; Ma, M. liang; Qi, H.; Meng, Q. feng; Guo, S. juan; Wu, Y.; et al. Linear Epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Elicit Neutralizing Antibodies in COVID-19 Patients. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 1095–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccoli, L.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Czudnochowski, N.; Walls, A.C.; Beltramello, M.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Pinto, D.; Rosen, L.E.; Bowen, J.E.; et al. Mapping Neutralizing and Immunodominant Sites on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-Binding Domain by Structure-Guided High-Resolution Serology. Cell 2020, 183, 1024–1042.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Oton, J.; Qu, K.; Cortese, M.; Zila, V.; McKeane, L.; Nakane, T.; Zivanov, J.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Cerikan, B.; et al. Structures and Distributions of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Proteins on Intact Virions. Nature 2020, 588, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, F.X.; Stiasny, K. Distinguishing Features of Current COVID-19 Vaccines: Knowns and Unknowns of Antigen Presentation and Modes of Action. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, R.; Rutten, L.; van der Lubbe, J.E.M.; Bakkers, M.J.G.; Hardenberg, G.; Wegmann, F.; Zuijdgeest, D.; de Wilde, A.H.; Koornneef, A.; Verwilligen, A.; et al. Ad26 Vector-Based COVID-19 Vaccine Encoding a Prefusion-Stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike Immunogen Induces Potent Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.T.; Bieneman, A.P. The S1 Subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Activates Human Monocytes to Produce Cytokines Linked to COVID-19: Relevance to Galectin-3. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, L.; Gaieb, Z.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hjorth, C.K.; Dommer, A.C.; Harbison, A.M.; Fogarty, C.A.; Barros, E.P.; Taylor, B.C.; Mclellan, J.S.; et al. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent Sci 2020, 6, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, J.M.; Adams, L.J.; Fremont, D.H. Antibody-Mediated Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 Spike. In Advances in Immunology; Academic Press Inc., 2022; Vol. 154, pp. 1–69. ISBN 9780323989435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealy, R.E.; Hurwitz, J.L. Cross-Reactive Immune Responses toward the Common Cold Human Coronaviruses and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Mini-Review and a Murine Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, P. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and Other Human Coronaviruses. Nat Rev Immunol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballmann, R.; Hotop, S.K.; Bertoglio, F.; Steinke, S.; Heine, P.A.; Chaudhry, M.Z.; Jahn, D.; Pucker, B.; Baldanti, F.; Piralla, A.; et al. ORFeome Phage Display Reveals a Major Immunogenic Epitope on the S2 Subdomain of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lai, D. yun; Zhang, H. nan; Jiang, H. wei; Tian, X.; Ma, M. liang; Qi, H.; Meng, Q. feng; Guo, S. juan; Wu, Y.; et al. Linear Epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Elicit Neutralizing Antibodies in COVID-19 Patients. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 1095–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Hou, X.; Liang, T.; Wang, D.; Teng, F.; Dai, J.; Duan, H.; Guo, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Proteome Microarray for Mapping COVID-19 Antibody Interactions at Amino Acid Resolution. ACS Cent Sci 2020, 6, 2238–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lin, S.; Chen, Z.; Cao, Y.; He, B.; Lu, G. Targetable Elements in SARS-CoV-2 S2 Subunit for the Design of Pan-Coronavirus Fusion Inhibitors and Vaccines. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polvere, I.; Parrella, A.; Zerillo, L.; Voccola, S.; Cardinale, G.; D’Andrea, S.; Madera, J.R.; Stilo, R.; Vito, P.; Zotti, T. Humoral Immune Response Diversity to Different COVID-19 Vaccines: Implications for the “Green Pass” Policy. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar Kashkouli, A.; Jafari, M.; Yousefi, P. Effects of Gender on the Efficacy and Response to COVID-19 Vaccination; a Review Study on Current Knowledge. Journal of Renal Endocrinology 2022, 8, e25064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, V.; Vuković, V.; Patić, A.; Marković, M.; Ristić, M. Immunogenicity of BNT162b2, BBIBP-CorV, Gam-COVID-Vac and ChAdOx1 NCoV-19 Vaccines Six Months after the Second Dose: A Longitudinal Prospective Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, A.A.; Dutcher, E.G.; Robinson, J.; Lin, J.; Blackburn, E.; Hecht, F.M.; Mason, A.E.; Fromer, E.; Merino, B.; Frazier, R.; et al. Predictors of Long-Term Neutralizing Antibody Titers Following COVID-19 Vaccination by Three Vaccine Types: The BOOST Study. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-C.; Millar, J.; Groves, T.; Grinshtein, N.; Parsons, R.; Takenaka, S.; Wan, Y.; Bramson, J.L. The CD8+ T Cell Population Elicited by Recombinant Adenovirus Displays a Novel Partially Exhausted Phenotype Associated with Prolonged Antigen Presentation That Nonetheless Provides Long-Term Immunity. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 176, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsis, N.; Fitzgerald, J.C.; Reyes-Sandoval, A.; Harris-McCoy, K.C.; Hensley, S.E.; Zhou, D.; Lin, S.-W.; Bian, A.; Xiang, Z.Q.; Iparraguirre, A.; et al. Adenoviral Vectors Persist in Vivo and Maintain Activated CD8+ T Cells: Implications for Their Use as Vaccines. Blood 2007, 110, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, K.B.; Turner, J.S.; Miller, F.I.; Jiang, R.; Pybus, O.G.; Ellebedy, A.H.; Kleinstein, S.H. Human B Cell Lineages Associated with Germinal Centers Following Influenza Vaccination Are Measurably Evolving. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.S.; Zhou, J.Q.; Han, J.; Schmitz, A.J.; Rizk, A.A.; Alsoussi, W.B.; Lei, T.; Amor, M.; McIntire, K.M.; Meade, P.; et al. Human Germinal Centres Engage Memory and Naive B Cells after Influenza Vaccination. Nature 2020, 586, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.S.; O’Halloran, J.A.; Kalaidina, E.; Kim, W.; Schmitz, A.J.; Zhou, J.Q.; Lei, T.; Thapa, M.; Chen, R.E.; Case, J.B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccines Induce Persistent Human Germinal Centre Responses. Nature 2021, 596, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Zhou, J.Q.; Horvath, S.C.; Schmitz, A.J.; Sturtz, A.J.; Lei, T.; Liu, Z.; Kalaidina, E.; Thapa, M.; Alsoussi, W.B.; et al. Germinal Centre-Driven Maturation of B Cell Response to MRNA Vaccination. Nature 2022, 604, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, B.J.; Ellebedy, A.H. The Germinal Centre B Cell Response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Yan, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, P.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. A Neutralizing Human Antibody Binds to the N-Terminal Domain of the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science (1979) 2020, 369, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, M.T.; Mermelstein, A.G.; Miller, E.P.; Seth, P.C.; Stancofski, E.S.D.; Fera, D. Structural Analysis of Neutralizing Epitopes of the Sars-Cov-2 Spike to Guide Therapy and Vaccine Design Strategies. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).