1. Introduction

Thunderstorms, which are also referred to as Cumulonimbus clouds (Cb), occur frequently during the summertime in many regions of the world. They are often accompanied by wind gusts, heavy precipitation, hail and turbulences. These weather events can lead to serious local floods, harvest failures and damages to infrastructure. Further, people all around the world are regularly killed by lightning strokes. In aircrafts passengers are well protected against lightning as a result of the phenomena known as Faraday cage. However, thunderstorms are usually associated with tubulences and those are one of the most common reasons for injuries in aviation. These examples illustrate that it is important to know the occurrence and expected severity of Cbs well in advance in order to protect infrastructure and human life.

Thunderstorm detection and monitoring is offered by operators of lightning detection networks, see [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, these services are commercial and do not use satellite information for the nowcasting of thunderstorms. Nowcasting is referenced here and throughout the manuscript as the temporal extrapolation of observations for 0-2 hours. In Europe one of the first entities who provided software for a satellite based thunderstorm nowcasting was the Nowcasting Application facility (NWC-SAF) [

7], but for the application at DWD this software was not suitable as discussed in detail in [

8]. As a result, the NowCastSat-Aviation (NCS-A) method was developed and implemented at Deutscher Wetterdienst as an operational 24/7 product at DWD’s High Performance Computer (HPC) with ecflow[

9].

NCS-A provides near real-time detection and predictions of convective cells across the global domain using geostationary satellites in combination with lightning data and information from numerical weather prediction. The satellites used for NCS-A are METEOSAT, the European METEOrological SATellite [

10], GOES, the US Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite [

11] and HIMAWARI [

12], which means sunflower in English. In 2023 the weather satellite GK2A [

13] operated by the Korean Meteorological Administration (KMA) was added. Lightning data from VAISALA [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] is used to highlight heavy convection and to reduce the false alarms and missed cells during the detection step, which would be incurred if only satellites were used. The GLD360 data covers the complete globe and is based on Broadband VLF Radio Reception [

14].

The NCS-A product is provided in 3 different severity levels. The light and moderate severity levels are defined mainly by the brightness temperatures derived from the SEVIRI water vapour channels. Light convection is defined for satellite pixels with a brightness temperature difference of the water vapour channels (

) larger then -1 and a convective KO index of less than 2. The later condition is used to reduce false alarms as not all cold clouds are thunderstorm clouds, see [

15] for details. The KO index is derived from the numerical weather prediction model ICON [

16]. For the moderate convection the clouds needs to be colder, in detail greater than 0.7 for the difference in the water water channels (

) and greater than 2 for the BT difference of the water vapour channel and the window channel (

). The latter condition can be used to identify overshooting tops , which are an indicator for strong updrafts associated with severe turbulences and hail [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The occurrence of lightning data is a prerequisite for the classification of the severe level. As a consequence, the severe level is usually surrounded by the light or moderate level. All lightning measurements occurring 15 minutes before the end of the latest satellite scan are taken into account. For the nowcasting two subsequent satellite images of the water vapour channel (ca 6.2

) from different geostationary satellites are used. These images are fed into the optical flow method TV-L1 [

21], which is provided as part of OpenCV [

22,

23]. The latest image is then extrapolated in time based on the estimated atmospheric flow. Forecasts are calculated every 15 minutes and cover lead times up to to 2 hours after the latest satellite scan with a temporal resolution of 15 minutes and a spatial resolution of 0.1 degree (ca 10 km). The nowcasting, including the processing of the satellite, lightning and NWP data, is performed with a software package developed at DWD referred to as Geotools. The Geotools package is written in python, using pytroll [

24] for reading of satellite data and georeferencing of the satellite data. More detailed information about NCS-A can be found in [

8]

Another global Cb nowcasting product is based on Convective Diagnosis Oceanic (CDO) algorithm. It is used to detect the area of thunderstorms that are most hazardous for aviation by a combination of geostationary satellite-based data and ground-based lightning data. A simple fuzzy logic approach is used to combine the information from different input fields. The CDO input fields are the cloud top height, the Global Convective Diagnosis [

25], the Overshooting Tops Detection algorithm [

17] and the EarthNetworks global, ground-based lightning detection network [

26]. On a regional scale radar data can be used for nowcasting as well, e.g NowCastMIX-Aviation (NCM-A) [

27].

Atmospheric Motion Vectors (AMVs) are typically used to predict the movement of cloud objects in satellite based physical nowcasting methods, whereby at least 2 subsequent satellite images are needed for their calculation. Different methods can be applied for the calculation of the AMVs, as discussed in more detail in [

28]. In modern applications AMVs are typically gained from optical flow methods. DWD has quite good experience with modern computer vision techniques, e.g. [

21,

29,

30]. They can be easily adapted to the different application fields as they provide a dense vector field based on a multi-scale approach. The parameters can be optimised for the respective application. Optical flow is used at DWD for the nowcasting of thunderstorms [

8], turbulence [

31], solar surface irradiance [

28] and precipitation/radar [

27,

32].

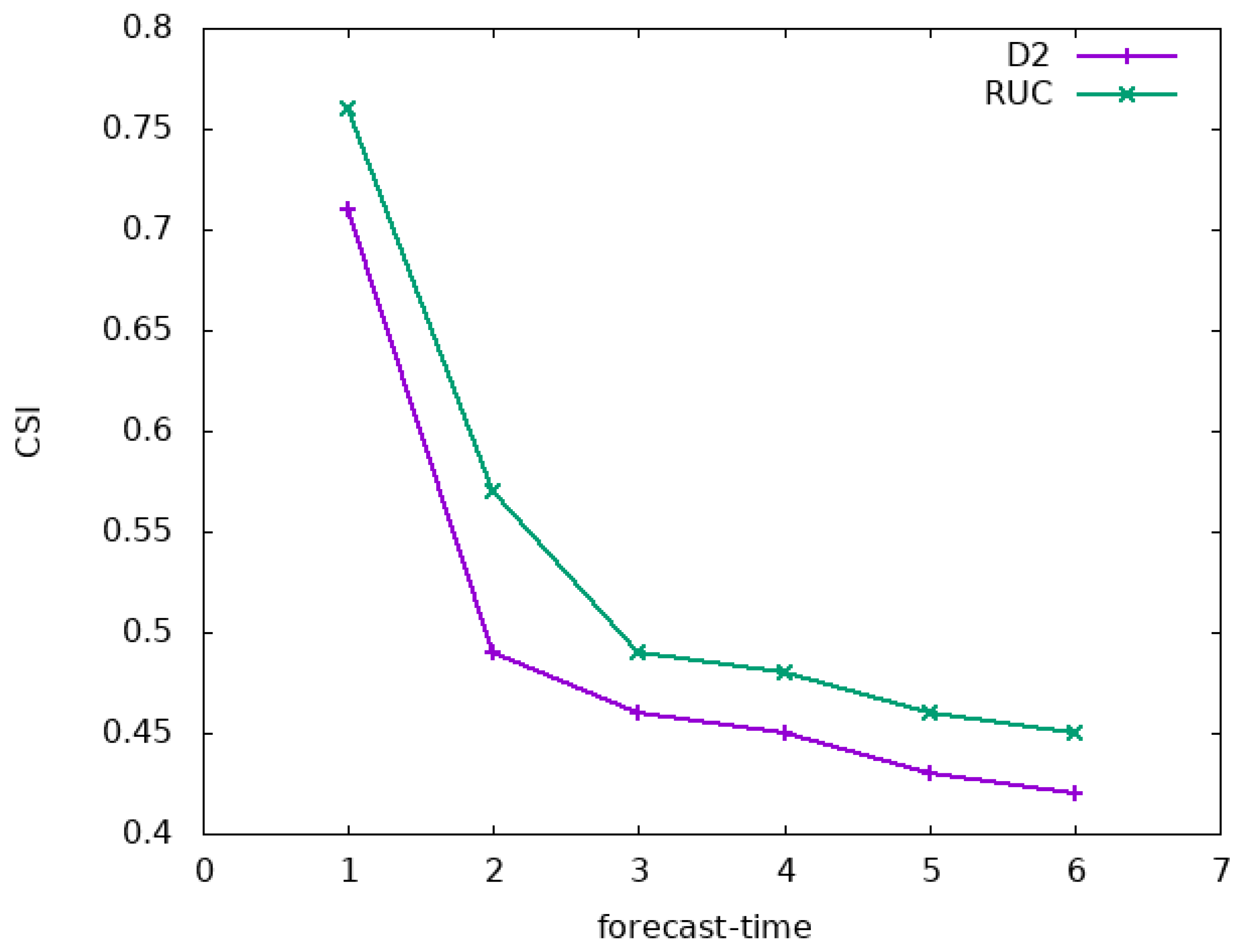

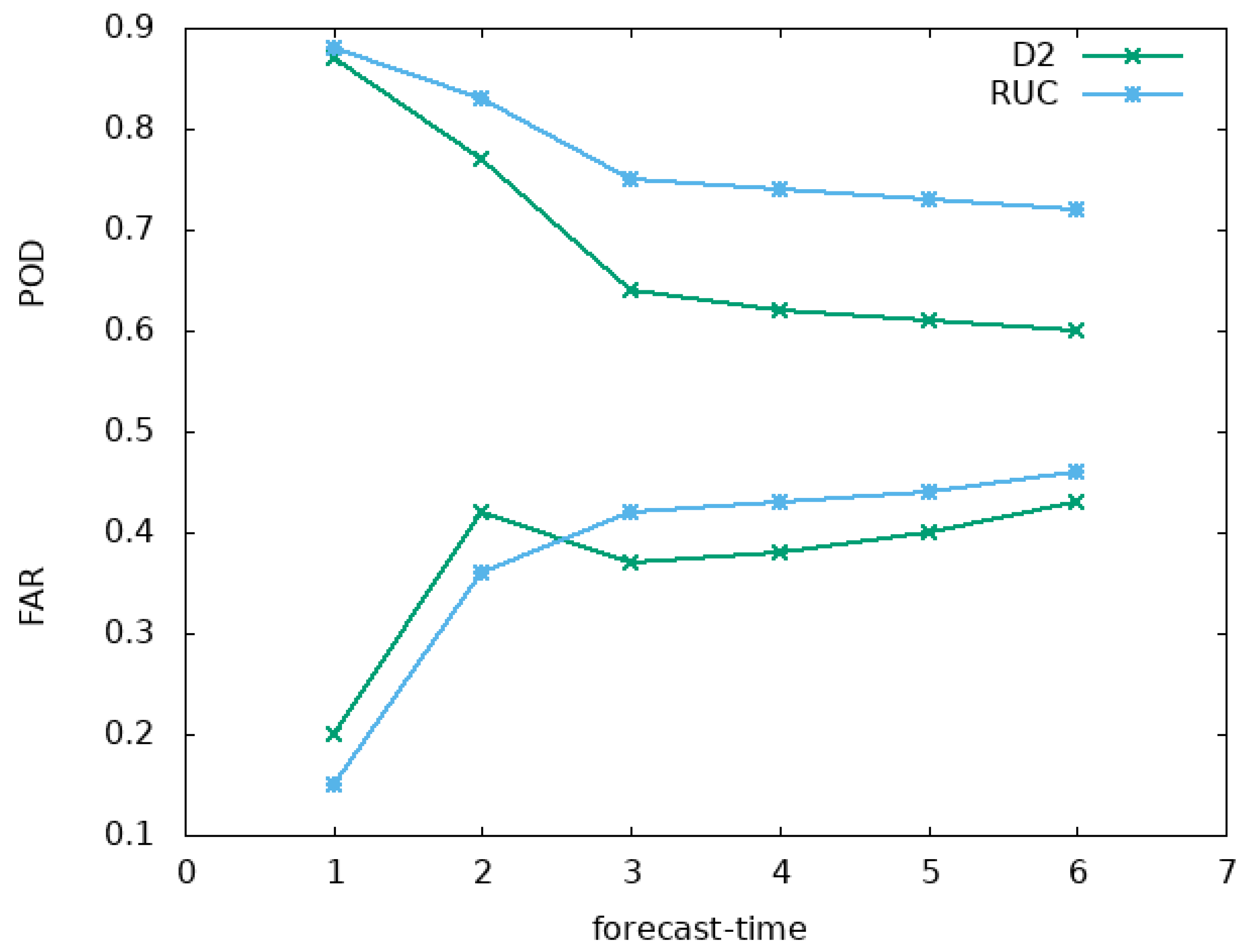

Yet, temporal extrapolation with AMVs only considers the movement of cells. Life cycle features, e.g. the dissipation or development cells, are not captured. However, a typical feature of convection is that the cells do not stay constant, but grow or dissipate. Hence, a central assumption of optical flow is violated, namely, that the intensity of the objects do not change. Thus, atmospheric motion vectors are not only limited by the fact that they are only describing the movement, but also by an increase of errors in the estimated advection in the presence of strong convection. Thus, the number of false alarms and missed cells increases considerably as the forecast time increases. The critical value of around 0.5 is usually reached for CSI after 90 minutes of prediction time and then drops off rapidly, regardless on the chosen optical flow method, see e.g. [

8,

33]. This limitation is an inherit feature and applies to all atmospheric motion vector methods as illustrated in

Figure 1 and motivated further developments to improve the accuracy and extend the forecast length. This includes adjustments of the nowcasting and the combination with numerical weather prediction.

Within this scope the manuscript provides an overview about recent developments concerning thunderstorm prediction at the DWD. In the first part (

Section 2.1) purely data driven thunderstorm nowcasting will be discussed with a subsection for cloud top height information, which is a typical companion for thunderstorm nowcasting. Afterwards in

Section 2.2 the analysis of the NWP ensembles is presented, which is used to prolong the data driven nowcasting to 0-6 hours. In order to combine the nowcasting and the NWP based forecasts a blending method is needed, which is described in

Section 2.3. The evaluation of the resulting 0-6 hour forecasts is discussed in the

Section 3. The paper closes with a discussion of the evaluation results and a conclusion, whereby also the strength and weakness of the physical approach is discussed in relation to data driven AI based nowcasting approaches, e.g. [

33].

2. Materials and Methods: 6-Hour Forecast of Severe Convection

The prediction of thunderstorms for the time range of 0-6 hours is done by a combination of the Lightning Potential Index (LPI) of the numerical weather prediction model ICON and the observational based nowcasting of thunderstorms. In the following the methods to generate the 0-6 hour forecasts are described in more detail. First, the nowcasting method is described, followed by a description of the analysis of the ensembles and the method for the blending.

2.1. The Nowcasting Method

In order to enable a good basis for the transition of the nowcasting to the analysis of the Lightning Potential Index (LPI) the NCS-A approach has been modified. This was also done to test further potential improvements of the method and the Julia programming language (

www.julialang.org, [

34]) which promises higher computing performance compared to python. This in turn is of great importance for big data applications. The python based NCS-A method needs almost 15 minutes in 10 km resolution (geostationary ring) and 8-12 after optimization, which is some kind of a show stopper for the use of the new capabilities provided by MTG/FCI [

35]. Below the main difference of the JuliaTSnow nowcasting method compared to NCS-A are discussed.

The nowcasting method JuliaTSnow was developed explicitly for thunderstorms. Thus, deep convection without the occurrence of lightning strokes are not covered by the method. As mentioned, the LPI is used as a proxy for thunderstorms on the model side. Thus, the basis for the detection of thunderstorms in the nowcasting part is based on lightning as well. This is a significant difference compared to NCS-A, where light and moderate convection can be classified without the occurrence of flashes.

Further, the optical flow method TV-L1 is replaced by Farnebäck, which works reasonable well for thunderstorms. Farnebäck is faster and more robust concerning static cells, but unfortunately also more sensitive to changes in intensities than TV-L1. Basically, two subsequent images of the brightness temperature differences of the water vapour channels are used [

15] (

) for the calculation of the optical flow. However, the optical flow method expects images within the range of 0-1, hence, the BT differences are normalized with a maximum value of 10 and a minimum of -4. The range is defined in order to focus on medium to optical thick clouds. This improves the quality of the AMVs, but increases also the computing speed.

Finally, the severity is defined in another manner. In both methods the severity depends on how cold the clouds are, beside others as a consequence of the relation between severity and brightness temperature, e.g. [

36]. NCS-A comes with 3 severity levels, but the JuliaTSnow provides continuous values from 0-1 for the severity of thunderstorms. The severity is defined as follows.

is the severity, are the normalized brightness temperature differences for the pixels at location i,j.

The JuliaTSNow approach provides TS nowcasting for Europe and Africa and needs only 2 minutes for the completion of the nowcast. The occurrence of at least one lightning event within a 10 minute interval and a search radius of 1 pixel is the precondition for the detection of a thunderstorm cell. JuliaTSnow is operated in two modes. First as a stand alone tool covering Europa, Africa and the surrounding oceans. In this mode the global GLD360 lightning data [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] is used. The respective TS nowcasting (0-90 minutes) is available on the DWD data server as a stand-alone product in 15 minute and 0.05 degree resolution in cf conform netcdf format [

37].

In the other mode only central Europe is covered and this mode is operated for the data fusion with ICON-D2 and ICON-RUC, see

Section 2.3. This region is well covered by the regional LINET data [

1,

38], which offers a higher density of lightning data. This is an advantage for blending with ICON. As a consequence of the combination with ICON the forecast horizon is extended to 0-6 hours in this mode. The respective data is not available on open data.

Information about the cloud top height of thunderstorms is an important information for many application, including thunderstorm nowcasting, thus a smart CTH approach is briefly described below.

2.1.1. Prediction by Visual Inspection - Cloud Top Height

The cloud top height is well suited for the visual analysis and nowcasting of thunderstorms and weather impacting clouds and offers in more generally the option of an early detection of developing convection. It is one of the most used satellite based products for the visual inspection of the development of thunderstorms at DWD.

Further, in many applications, in particular dealing with aviation, the severity information of the thunderstorms or severe convection is accompanied by cloud top height information. Also, NCS-A provides a cloud top height information for deep convection, whereby a NWP filter is applied for the light convection. However, the aviation customers asked for height information for all optical thick clouds without NWP filtering in order to get a global scan of weather active zones into the cockpit as well. For this reason a cloud map option has been added to NCS-A with the discrete distinction between low, medium and high clouds see

Figure 2.

Before a CTH can be calculated a cloud mask is needed. As the focus of the CTH product for aviation lies on optical thick clouds the Brightness Temperature Difference (BTD) of the water vapour channels with BTD threshold of about -8 to -10 can be used [

17,

39]. Optical thick clouds are opaque in the IR. Hence, in good approximation, the observed BT equals the temperature of the cloud top. For opaque clouds, the cloud top height can be defined as follows:

Here,

is the brightness temperature of the IR window channel (∼ 10.8

),

and

are the temperature and height of the tropopause from numerical weather prediction model ICON [

16] or likewise climatologies. LR is the Lapse Rate and is set to 8.0 [K/km] for NCS-A [

8,

15,

31].

For the aviation specific CTH product three height levels were defined from user requirements of NCS-A users, which are FL250(7.6km), FL325(9.9km) and FL400(12.2km). The following CTHs and BTD thresholds are used for the definition of the three levels. Cloud heights greater than FL400 should indicate areas where flying over the clouds is not advisable due to a possible stall (coffin corner)

While discrete height information is sufficient for the NCS-A product, continuous CTH products have established themselves in general weather forecasting. Further for the combined use of CTH with radar reflectivities a parallax corrected CTH product is of great benefit. This motivated the development of a stand-alone CTH product for Europe. As this product includes all clouds and not only optical thick clouds a different cloud mask is needed. The respective cloud mask results from the adaptation of the CALSAT method [

40] to the Infrared window channel (10.6). As a consequence the Cloud Top Height (CTH) is then calculated for cloudy pixels with equation

2. However, in this case

and

information comes from standard climatological profiles for the ease of it and to avoid model contamination. Thus, in contrast to other methods no information from Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) is needed Further, in contrast to NCS-A the lapse rate is assumed to be 6.5

in accordance with ICAO_93. The difference is motivated by the fact that NCS-A is only applied to deep convection whereas the CTH open data product covers all cloud types.

For semitransparent clouds a correction of the CTH is needed which can be done with a method referred to as water vapour H2O- intercept method [

31]. The CTH open data product [

41] is provided as cf-conform netcdf file in a regular grid, with a spatial resolution of 0.05x0.05 degrees and a temporal resolution of 15 minutes (10 minutes with MTG). The height is given in m. For the combined use with radar data, the CTH product is parallax corrected using a function from the Julia satellite library. This library is available on request. The basic geometric equation in this function are from Eumetsat.

2.2. Thunderstorm Forecast with LPI

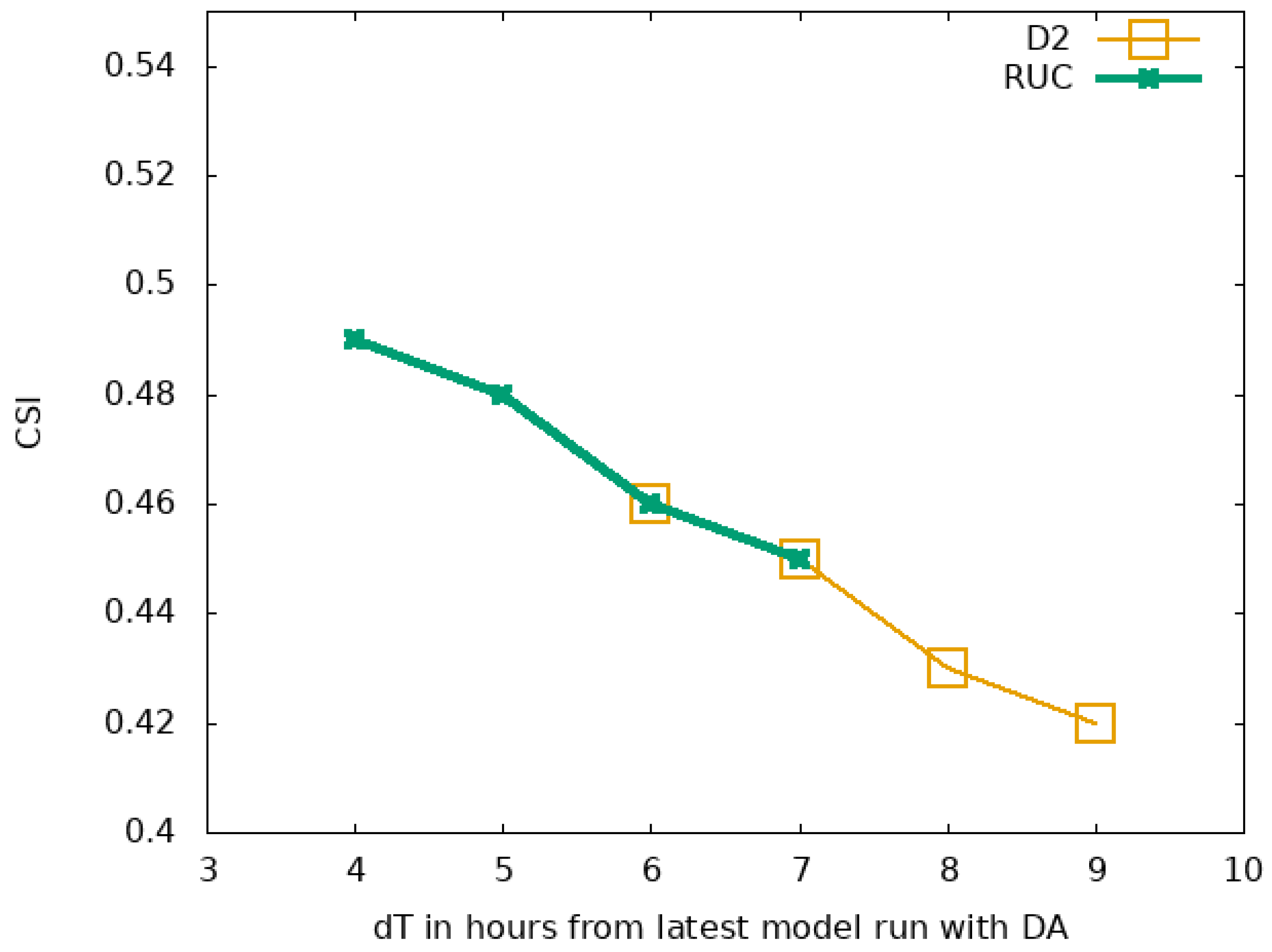

Numerical weather models (NWP) contain physics, which allows to simulate the life cycle of cells and with that the dissemination and development of cells. Hence, there might be a potential to improve and extend reliable thunderstorm prediction by blending data driven nowcasting with numerical weather prediction. Of course, due to the complex and partly chaotic thermodynamics the accurate simulation of the processes are quite difficult. A central key to improve the forecast quality is data assimilation, as this forces to model to the real atmospheric conditions. Within this scope one aim is the use of as many observational data as possible in order to define the initial state of the atmosphere for the data assimilation as good as possible. On average, the higher the uncertainty of the initial state the higher the uncertainty of the simulated weather. Also great progress has been done to improve the definition of the initial state, e.g. by the use of the data from new satellite generations, there is still a significant under-determination of the initial state. Further, also the model physics induces uncertainties in the forecasts. To account for these uncertainties weather services implemented the option of ensemble forecasts, which are also used in this study.

Thunderstorms are among the most chaotic phenomenons of weather. Based on the theory of Lorenz [

42] it is expected that an higher update cycle of data assimilation leads to a better accuracy in particular for short term forecasts. This will be further investigated and discussed in

Section 4 after presentation of the results.

In this study the regional NWP model ICON is used for the combined product. The ICOsahedral Nonhydrostatic D2 [

16,

43] is a nonhydrostatic model that enables improved forecasts of hazardous weather conditions with high-level moisture convection (super and multi-cell thunderstorms, squall lines, mesoscale convective complexes) due to improved physics in combination with its fine mesh size. The domain of ICON-D2 covers Germany and bordering countries with a spatial resolution of 2.2 km. For ICON-D2 data assimilation is applied every 3 hours, a complete model run needs approximately 2 hours.

ICON-D2 is the current operational model at DWD. It provides meteorological variables every hour for the routine weather forecasts and the DWD open data server. In parallel, numerical experiments were carried out with a Rapid Update Cycle (RUC) of ICON, in which the data assimilation is performed every hour and meteorological variables are provided every 15 minutes.

The processing time is 1 hour, so that forecast are available 1 hour after the start of the respective model run, e.g. at 13 UTC the forecasts from the 12 UTC run are available. This offers a timely availability of the forecast runs with the latest data assimilation step. In addition, a 2 moment micro-physical scheme has been implemented in RUC which improves the cloud physics [

44].

As a proxy for thunderstorms the maximum of the lightning potential index (

) during a given time step is used. The Lightning Potential Index (LPI) is a measure of the potential for lightning in thunderstorms. It is calculated from simulated updraft and micro-physical fields. It was developed to predict the potential of lightning occurrence in operational numerical weather models. The implementation in ICON-D2 and RUC follows the approach of [

45]. Further information of the implementation into ICON-D2 are given in [

44]. For ICON-D2

it is the maximum during the last hour and for ICON-RUC during the last 15 minutes.

ICON ensembles of D2 and RUC are analysed to define the occurrence and severity of thunderstorms before the blending is applied. The respective analysis is motivated by an approach of Axel Barleben, which is used for a NWP only product provided to MUAC for evaluation purposes. This product is referred to as iCONv from ICON-Convection and is based on operational ICON ensembles [

16]. In this product, meteorological variables relevant to convection, specifically lightning, precipitation, hail, reflectivity and wind gusts, are used to define the occurrence and severity of convection. The selection of the variables is motivated by the work of James et al. [

27]. The three convection levels are then defined by fuzzy logic. An example of the product is given in

Figure 4

However, this approach was modified for the blending with the JuliaTSnow nowcasting and only

is used, as this variable already combines meteorological properties that are relevant for thunderstorms. Following a brief description of the modified approach applied for the blending with the nowcasting. If one of 20 members is above a certain threshold, than it is assumed that a thunderstorm exist. The severity is then defined by the number of ensemble members above the threshold, e.g. 10 members out of 20 would lead to a severity of 0.5. This definition is based on the comparison for several cases with the nowcasting described in

Section 2.1 in order to adjust the severity levels of both worlds, NWP and observational based nowcasting.

As a consequence of the different micro-physics implemented in RUC, the input information for the calculation of the LPI differs as well. This motivated an different adjustments of the thresholds for the analysis to improve the comparability of the results. For RUC 2.5 is used and for D2 5 .

2.3. The Ensemble Post-Processing and the Blending

In a first step the ensembles of ICON-D2 and ICON-RUC are extracted from the data bank. The ensembles are then processed with the free software fieldextra [

46]. Fieldextra is used to estimate the thunderstorm severity as described in

Section 2.2 by statistical analysis of the ensemble members. Further it is used to convert the hexagonal original grid to regular latitude longitude gird and the grib format to netcdf.

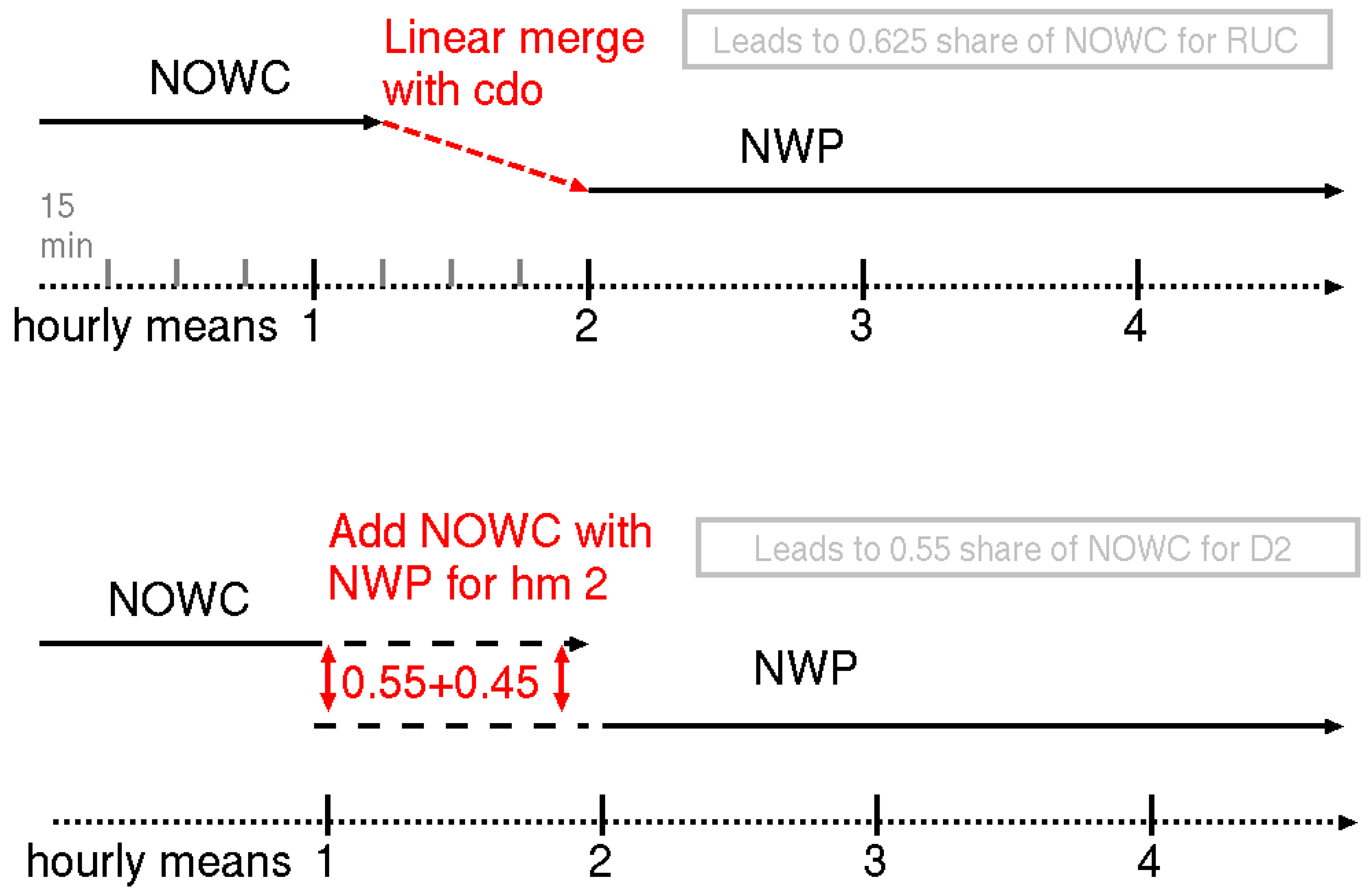

The closest available NWP-runs in terms of time were used for the blending with the nowcast. As an example, for the blending taking place at 13 UTC , the most readily available ICON-D2 run is that of 9 UTC, as the ICON-D2 takes 2 hours to calculate and new runs only start every 3 hours, so the 12 UTC run is not completed and no earlier run then that of 09 UTC is available. In contrast, the 12 UTC run of ICON-RUC is already available as a new run starts every hour and the calculation time is only 1 hour for RUC. For the 14 UTC prediction, the 12 UTC run of ICON-D2 is ready, hence the 12 UTC ICON-D2 run can be used. However, for RUC the 13 UTC is already ready and can be used. In the first step the blending of nowcasting and NWP was done as illustrated in

Figure 5. For D2 this was done based on hourly values. In this case hourly means of the nowcasting has been calculated beforehand. For RUC the 15 minute values were blended. However, in order to enable a comparison with D2 hourly values of the blended product were calculated after the blending. Because of the different time resolutions of RUC and D2 different blending methods were used, see

Figure 5 for further details. For both approaches the climate data operators were used [

47]

Please note that the blended product is calculated every hour for the complete forecast horizon of 6 hours.

4. Discussion

The results indicate that the higher CSI scores of ICON-RUC are mainly due to the higher update cycle of the data assimilation. This is supported by the theory of Lorentz [

42] and well established knowledge about chaos theory. Within this scope it is well known that the model errors increases rapidly at convection-permitting scales [

50]. This explains why the information from the observations gets rapidly lost. It is therefore obvious that a higher update cycle of the data assimilation and a more accurate definition of the initial state of the atmosphere are the main driver for improving NWP model-based 0-6h predictions. Inconcsistensies in the model physics could amplify these effects.

For these reasons a central question is: Wouldn’t it be better to carry out deep learning if the accuracy of the model system is determined by observations anyway and the NNP could devalue useful observations ? In other words, would it not be better let the network learn the physics from the observations. Indeed the results of deep learning provided in Brodehl et al. [

33] indicates that higher skill scores without any model physics can be achieved for short term forecastin than with state of the art NWP models. Also for other model parameters and medium term forecast it has been shown that artificial intelligence can beat NWP [

51,

52]. Of course, reanalysis data will continue to be very important, as reanalysis provides a consistent and rectified 4-D data cube for the training of AI. But, what is the future of numerical weather prediction ?

It is likely that numerical weather prediction in its current form will be replaced by data driven AI models, within the ongoing AI revolution [

53]. However, until then, it is important that data assimilation is improved. In addition to rapid updates of the assimilation, the description of the initial state as complete as possible is also extremely important. In case of thunderstorm forecasts the description of the initial state, and with that the ICON forecasts, could be improved by assimilation of lightning data, e.g. [

54].

However, the training of AI is not a trivial task and needs man and computing power. Further, regular retraining is needed. For this purpose an appropriate infrastructure, concerning both computer hardware and human resources are needed. The weather services are currently in a transition phase, as both the computer infrastructure and stuff are not optimally suited for AI. It is known from the social sciences that fundamental changes meet with resistance and that people have a tendency to cling to the old ways. On one hand, this constitutes a protection against hasty changes, but it can also slow down innovation and necessary changes. Applied to weather services, it could be that the NWP enthusiasts are sticking to numerical weather prediction for too long. Yet, the customers are likely not taking care about the method behind, but are interested in the quality of the products and services. Thus, it could be that many products and services of traditional weather services will become obsolete if they miss the train of the AI revolution [

53] .