1. Introduction

The development of sustainable types of materials is one of the most common trends in materials technology of polymer composites. The are few aspects of the sustainability problems for polymer composites. The first issue is connected with petroleum-based nature of most of the thermoplastic and thermoset polymers. Second problem concerns the negative environmental impact of the synthesis and preparation methods for polymer-based materials. The last issue regards to the problem of polymer waste management. The listed problems are related to the polymer processing industry in general; however, for engineering composite the listed issues should be more exposed to discussion. Unlike the packaging production industry, where plastics processing have been focused on reducing the negative impact on the environment for many years, the serial production of polymer composites is on the very beginning of the process to be converted to more sustainable. An example of the problems discussed are materials produced by injection molding. Materials of this type are used in many areas of the economy, such as machine construction, electrical engineering, transport or electronics. However, there are still no systemic solutions to many problematic aspects of the use of this type of materials.

Previous research adopts several concepts that can be implemented in industrial practice and will allow for the reduction of the negative environmental effects of the production of technical composites. The most popular pro-environmental strategies, already widely used in many companies, are the management of post-production waste or post-consumer polymers. Research in this area is carried out in almost every variety of thermoplastic polymers. The advantages of this concept include the ability to quickly implement new material solutions, simple optimization of material properties, and economic benefits for manufacturers. However, material recycling has certain limitations related to the availability of good quality polymer materials and the inability to meet selected quality standards in the food or medical industries.

Currently, plastics producers and processors are paying attention not only to the need to recycle polymer composites but also to the creation of materials with a lower rate of use of petrochemical semi-finished products. Materials of this type include numerous varieties of composites based on biobased polyamides synthesized from vegetable oils or thermoplastic polyesters synthesized from substrates that are the product of fermentation of natural polysaccharides.

The development of techniques for producing polymer composites, apart from numerous examples of research on polymer synthesis, currently also focuses on the possibility of developing new types of polymer fillers. In this field, very positive results are obtained for materials of secondary origin, such as carbon and glass fibers recovered in the chemical and thermal decomposition processes of the polymer matrix [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In addition to the possibility of recycling synthetic fibrous materials, great interest has been observed for many years in the area of natural fiber-based materials processing. Natural fibers that constitute a potentially effective and competitive type of reinforcement include materials based on linen(flax), hemp, bamboo, or cotton; in selected applications, they can be used in the automotive and construction industries. However, in practical large-volume applications, materials in the powder form are more commonly used. Wood fibers, saw dust and cellulose particles, are the most popular examples of such additives. They are often a by-product resulting from the processing of wood or other types of lignocellulosic materials, like leaves, shells, or husk. Unlike long fibers, wood-based fillers can be processed without additional processing, similar to other plastic additives such as mineral fillers or concentrates in the form of granules.

The research work that is the subject of this study presents the method of preparing materials based on polyoxymethylene and its blends with PLA and natural fillers. The presented concept for developing composite materials is a combination of two operational strategies. The first is the concept of replacing synthetic varieties of polymer fillers with lignocellulosic materials, while the second is the process of mixing petrochemical POM with partially biobased PLA. The works discussed are an extension of previously conducted research on the modification of POM/PLA mixture systems. In the current case, the research work was divided into two stages, where first, composite materials based on unmodified POM were prepared. Composite additives in the form of wood flour, cellulose and ground grain husk were introduced in amounts ranging from 10%, 20% and 30% to allow for a general assessment of the mechanical characteristics of the prepared materials. In the second stage of work, the polymer matrix was modified. Three types of POM modifications were prepared: a POM/PLA blend, POM/PLA with the addition of an elastomer, and a POM/PLA/elastomer blend prepared in the reactive extrusion process. In the case of the materials discussed, one of the aspects of the work was to obtain good thermomechanical properties, therefore some of the materials were additionally thermally treated, which was aimed at increasing the level of crystallinity of the matrix and increasing thermal resistance. For the developed materials, one of the aspects of the work was to obtain good thermomechanical properties, therefore some of the materials were additionally thermally treated (annealed), which was aimed at increasing the level of crystallinity of the matrix and increasing thermal resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The polyoxymethylene POM resin type used for the study was Tarnoform 300 from Azoty SA, MFR = 9 g/10 min (2.16 kg/190 °C). The poly(lactic acid) PLA type was Ingeo 3251D (NatureWorks), MFR = 35 g/10min (2.16 kg/190 °C). The elastomeric compound, referred as EBA, was ethylene-butyl acrylate-glycidyl methacrylate copolymer E/BA/GMA, supplied by Du Pont under trade name of Elvaloy PTW. Chain extender (CE) styrene-acrylic oligomer was used as the reactive extrusion compatibilization agent, grade Joncryl 4368C (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany). Four types of natural fillers were used for the composite preparation. Conifer tree-based wood flour (WF), Lignocell C120, particle size of 70-150 μm. The cellulose flour (CF) Arbocel FD 600/30. The detailed description of the woof and cellulose flour was already described in our previous paper [

6]. The buckwheat husk particles (BH), supplied from the Sante company, was melt sieved and divided into two types, where coarse particles had a size above 0.8 mm, and fine particles below that size, the characterization of the milled BH particles was already discussed in the literature [

7,

8,

9].

2.1. Sample Preparation

The materials compounding was conducted using twin-screw extrusion method, we use Zamak EH16.2D type machine equipped with 16 mm diameter screws. The process was conducted at the temperature of 200°C, and screw speed of 80 rpm. Before processing the natural fillers were dried for 12 hours at 90 °C. Pellets were dried separately for 6 hours, POM resin at 90°C, while PLA resin at 60°C. All materials were initially dry-blended, and placed inside the machine hopper. The melt blended materials were cooled down using water bath, and pelletized. Before next processing the pellets were dried again at 80°C for 6 hours.

Samples were prepared by injection molding method, where Engel ES 80/20 HLS hydraulic press was used. Samples were molded at 210 °C, where the mold temperature was 40 °C. Part of the samples were treated by annealing procedure, where we use the cabined oven, the temperature was set to 120 °C, the time of annealing was 3 hours.

2.1. Charakcterization

The mechanical properties of the prepared materials were characterized using universal testing machine, model Zwick/Roell Z010. The tensile tests were conducted according to ISO 527 standard. The impact resistance measurements were conducted using notched Izod method, according to ISO 180 standard.

Thermomechanical properties were evaluated using dynamic mechanical analysis method (DMTA), we used Anton Paar MCR301 apparatus equipped with torsion clamp system. The test were conducted from 25 °C to 150 °C, with the heating rate of 2 °C/min. The strain amplitude was set to 0.01 %, while the frequency was 1 Hz. The additional HDT (heat deflection temperature) test were conducted using HDT/Vicat RV300C machine, where the measurements were performed according to ISO 75 standard.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Mechanical Performance Evaluation – Static Tensile Tests, Charpy Impact Resistance

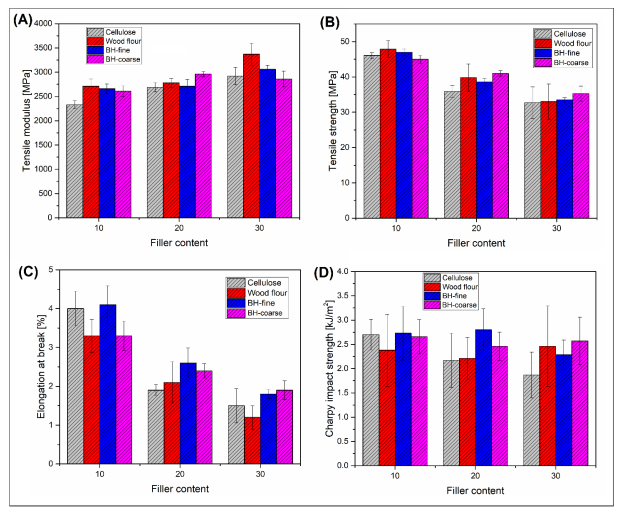

The properties of the manufactured composites are presented separately for POM-based composites (see

Figure 1) and modified POM-PLA blend materials (

Figure 2). The results of the initial investigation for POM composites are presenting the mechanical characteristic for materials with addition of 10%, 20% and 30% of different types of natural fillers. The results for POM/PLA blends are reflecting the properties of the unreinforced blends and 20% wood flour (WF) composites.

The combination of high crystalline POM resin and natural fillers results in visible stiffness improvement. The observed changes are significantly lower than the reinforcing efficiency of glass or carbon fibers [

10,

11,

12], while the highest value of the tensile modulus was close to 3400 MPa, comparing to 2100 MPa for unmodified POM. Interestingly, the differences between the individual varieties of used fillers are small, despite large differences between the particles morphology. The fibrous nature of the cellulose and wood flour particles should result in a more effective reinforcement effect, but the examples presented will not confirm this theory. The analysis of the tensile strength values is confirming the lack of favorable changes for composites. The strength for all of the prepared composites is visibly lower than for reference POM samples (58 MPa). The results recorder for samples with 30% filler loading are close to 35 MPa, which means that the reduction reached around 40 %. It is clear that this kind of behavior must be consider as important drawback. Similarly to the changes observed for the tensile modulus, the differences for individual types of fillers are very slight, more evident are the changes cause by the filler content.

The results of the elongation at break and Charpy impact strength confirmed that the presence of natural filler is leading to ductility deterioration. The strain at break for pure POM was close to 23 %, while even the 10% content of the filler particles was reducing this value to around 4 %. When the filler content was increased the elongation was even lower, while for POM/30%filler specimens the recorder elongation was below 2%. Interestingly, for impact strength result the downward trend was not revealed, apart from the obvious difference between the results for unmodified POM (6.5 kJ/m2) and the composite samples. The Charpy impact strength ranged from 1.5 kJ/m2 to 3.0 kJ/m2, which result were already reported for composites prepared from the selected POM resin type [

13,

14]. Summarizing the results mechanical properties characterization for initial part of the research it is worth to note that none of the used type of filler did not reveal the visible advantage. The expected favorable properties of fibrous fillers, cellulose and wood flour, were not confirmed by the results. The second stage of research was conducted using the 20% wood flour. Considering the price and availability of this type of materials, seems to be the most optimal solution.

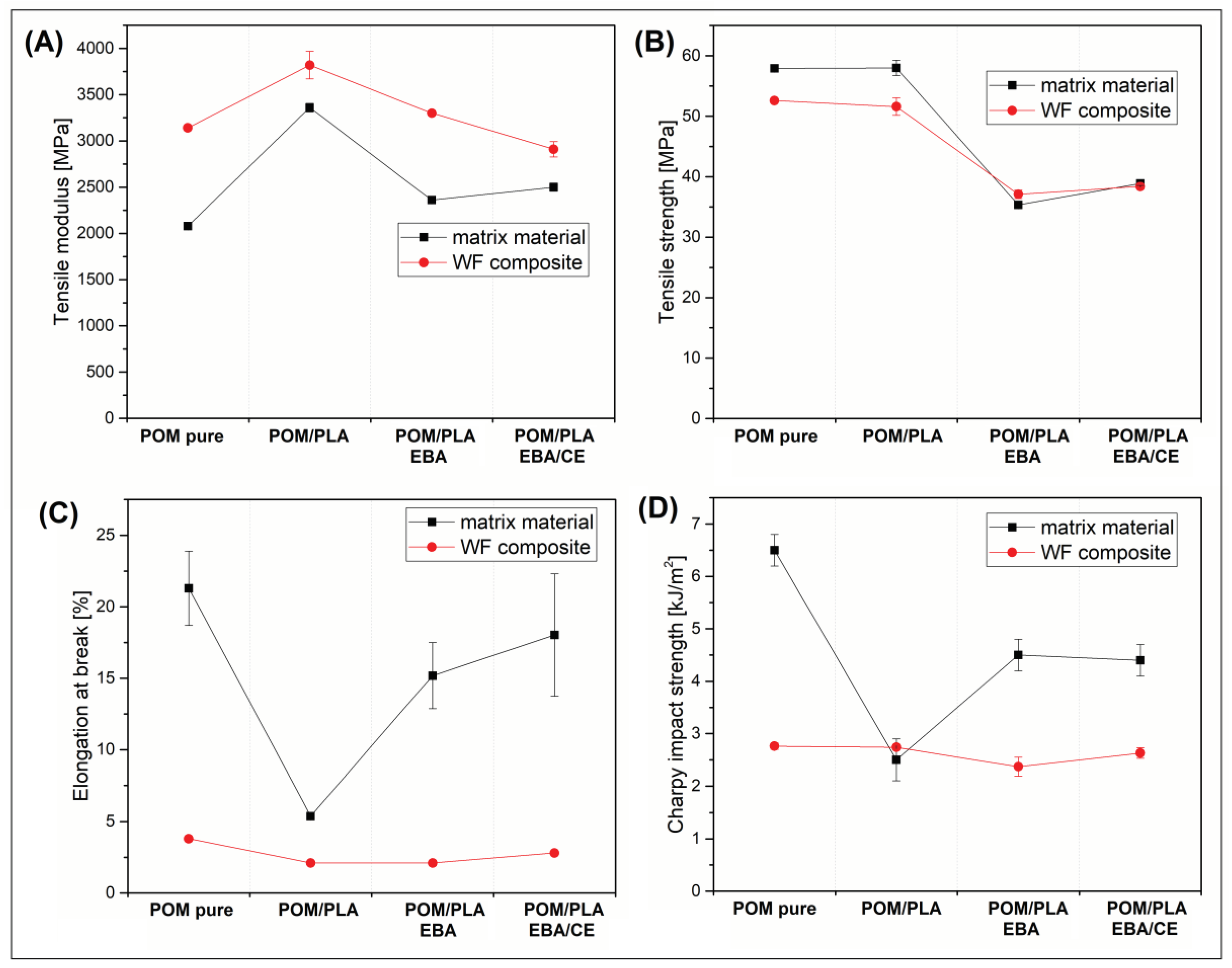

For the main part of the study the prepared blends were compared to the pure POM materials. The results collected in the

Figure 2. are showing the mechanical characteristic changes after the introduction of PLA and modified to the reference POM. The plots are showing the results for unfilled blends and WF-reinforced materials. For the tensile modulus the it is clear that the addition of PLA component is leading to visible stiffness improvement, which was observed for both POM/PLA blend and POM/PLA-WF20 composite. As expected, for EBA-modified samples the tensile modulus was reduced, which is typical behavior for elastomer toughened materials, especially for dedicated copolymers like E/BA/GMA compound [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Similarly to stiffness the tensile strength results for toughened samples are visibly reduced. Interestingly, for EBA-modified specimens the tensile strength values for unloaded and WF-reinforced samples are very similar. In contrast, for pure POM and POM/PLA materials the is a visible difference in tensile strength values, where the results for WF-reinforced samples are slightly lower for unloaded blends. Since the main reason for addition of E/BA/GMA compound and CE reactive compound was the compatibilization and toughening of the POM/PLA blend system, the most important results of the modification are reflected by elongation at break and impact strength results [

19,

20,

21]. The maximum strain of 5% for POM/PLA blends was significantly reduced comparing to the reference POM (22 %). The main reason for that is the lack of ductility for PLA component, since the elongation for pure PLA reached only 4%. As confirmed by our previous study and the other research reports [

22,

23,

24,

25], the miscibility of the POM/PLA blends is relatively high, which suggest the partial self-compatibilization of this polymer system.

Figure 2.

The results of static tensile tests and Charpy impact resistance measurements for POM/PLA blends: (A) tensile modulus; (B) tensile strength; (C) elongation at break; (D) Charpy impact strength. Plots are reflecting the results for unmodified and wood flour (WF) reinforced samples.

Figure 2.

The results of static tensile tests and Charpy impact resistance measurements for POM/PLA blends: (A) tensile modulus; (B) tensile strength; (C) elongation at break; (D) Charpy impact strength. Plots are reflecting the results for unmodified and wood flour (WF) reinforced samples.

Unfortunately, for the described blend system, good miscibility does not translate into the possibility of obtaining optimized mechanical properties, therefore the improvement in elongation value occurs only after the elastomeric phase introduction. The addition of the EBA component was leading to large improvement in toughness since the elongation at break for POM/PLA/EBA and POM/PLA/EBA/CE sample strongly increased, reaching at least 15%. The trends observed for the stain values are simultaneously reflected for impact strength. Taking into account the results for the POM/PLA blends themselves, the visible effectiveness for the used modifications was revealed. However, in the case of conducted research, the key aspect is the use of the addition of natural fillers. In this context, elongation at break and impact strength indicate that the type of used matrix is not decisive since both results indicate a very high brittleness of composites with the addition of wood flour. The recorded strain at break results for WF-modified materials are below 4%, lower that the results of unmodified POM/PLA blend. The same conclusion refers to the impact test results where for all composite materials the results ranged from 2.5 kJ/m2 to 3 kJ/m2. Such results clearly indicate that in the case of the tested composites based on the POM/PLA system, it is not advisable to use them in applications where impact strength will be a key operational parameter. Taking into account that filled materials have increased stiffness and strength comparable to unreinforced mixtures, the use of this type of systems still seems reasonable. Considering, that the most important reason for using a PLA-based matrix in the discussed research was the bioderived nature of this polymer, the obtained results are confirming that the POM/PLA system can be used as effective matrix for natural fibers.

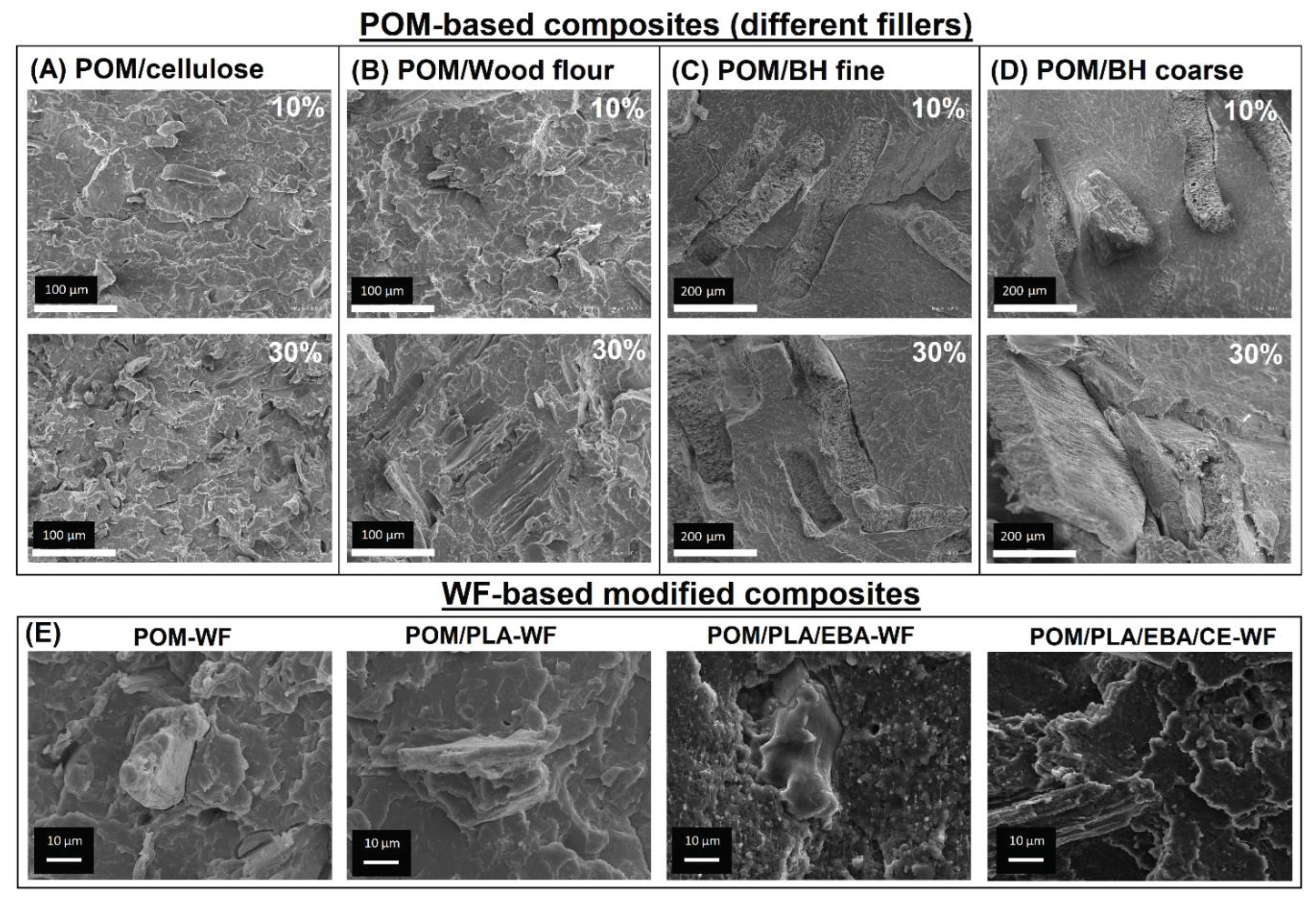

3.2. Structure Evaluation – Scanning Electron Microscopy Observations

Structure of the obtained composites was characterized using scanning electron microscopy method, where the investigated surface was obtained from the impact fractured samples. The structure appearance of the POM-based composite is reveled in the

Figure 3A–D. The presented pictures are presenting the general view for different types of fillers, and the loading content of 10% and 30%. The POM/PLA-based composites are presented in the

Figure 3E, the modified samples are presented with higher magnification in order to reveal the WF-filler matrix interphase.

The differences in the structure appearance for fibrous cellulose and wood fibers are negligible. For both types of fillers the 10% loaded samples have similar irregular surface of the fracture, the appearance of the fibers is manifester by the presence of relatively randomly distributed short fibers. The pull-out mechanism typical for the synthetic fibers, like carbon or glass fibers, cannot be observed. Due to the relatively low length-to-width ratio of cellulose and wood filler, the used natural fibers behave in a manner similar to mineral particles with spherical morphology. This is even more visible for materials with 30% filler content, where the structure takes on a more chaotic appearance. Interestingly, the fibers do not agglomerate and are usually evenly distributed in the matrix. The structure of materials with the addition of BH particles has a different character. The size of the filler particles is visibly larger, since the size of the coarse particles can reach around 1.4 mm, which was the size of the sieve during the preparation procedure. The surface of the matrix component in more smooth which partly confirmed the presence of more brittle behavior, the distance between the BH particles is much bigger than for wood or cellulose fibers. Interestingly, there is no visible difference between the materials with 10 % and 30% of the BH filler, which is mainly due to the size of the filler particles themselves, since they occupy a significant volume of the observed section of the sample. Summarizing, the microstructure analysis it is worth to emphasize that the fibrous reinforcement seems to be more favorable in the context of structure homogeneity. It is worth adding that the large particle size of the BH filler has a significant negative impact here, because in previously carried out works it was possible to obtain a more homogeneous composite structure [

7,

26].

The modification of the matrix blend by using PLA component was performed in order to increase the sustainability of the composite system. However, the previously reported results are suggesting some additional features like self-compatibility of the blend after EBA addition [

22]. That phenomenon was already confirmed for many other types of thermoplastic blends, since the addition of polyester component is leading to the formation of copolymers, especially when the reactive component of the modifier is forming the chemical bond with the PLA hydroxyl end groups [

16,

27,

28]. Interestingly, for the prepared blends the self-compatibilization of the unmodified POM-PLA blend was confirmed, since the matrix structure was characterized by smooth surface and lack of visible phase separation. That kind of behavior was already describe in our previous research, while for the presented study we focused on the evaluation of the WF filler/matrix interactions. It seems that the direct comparison of the POM-WF and POM/PL-WF composites revealed the difference in filler surface wettability. For the POM-based samples the boundary region was cracked forming visible gap at the interface. For POM/PLA blends the interface region was bonded to the surface of the fiber particle, which suggest stronger interface adhesion for the POM/PLA blend system. Similar results, revealing favorable interface adhesion were observed for POM/PLA/EBA-WF and POM/PLA/EBA/CE-WF samples; however for toughened samples the additional structural changes were connected with the presence of the elastomeric phase. For both types of composites the E/BA/GMA phase inclusion were visible, additionally the surface of the fractured surface was covered with visible fibrous structures. The observed fibers were formed during the plastic deformation of the toughened structure, which is a typical behavior when surface fracture was obtained in standard temperature conditions.

3.3. Thermomechanical Properties – Dynamic Mechnical Thermal Analysis (DMTA), Head Deflection Temperature (HDT)

The thermomechanical properties of the developed materials were investigated using dynamic mechanical thermal analysis method (DMTA) and heat deflection temperature tests (HDT). The DMTA method allows to investigate the changes in materials stiffness (modulus), while the HDT test results are widely accepted by the industrial users as the valuable measurement for thermal resistance changes. The results of both types of measurements are collected in the

Figure 4. Since the most important differences in HDT tests, were observed for the PLA-modified materials, the presented results are focused on the evaluation of the thermomechanical properties for POM/PLA-based blends and composites. The initial study conducted for the POM-based composites revealed only some minor differences between the composites modified with the use wood flour, cellulose and BH particles. The HDT results ranged from 121°C to 132 °C, with no clear trends caused by the amount or type of filler.

The results of the DMTA analysis for unfilled POM/PLA blends (see

Figure 4) are revealing visible difference in material stiffness. The unmodified POM resin is characterized by a constant decrease in stiffness over temperature; however, taking into account the differences between the temperature at the beginning of the measurement around 25°C and the end of 150°C, the dynamics of these changes is very small. In contract, for pure PLA the rapid drop of the storage modulus values is observed at 60 °C. The observed behavior is revealing the typical difference between the thermal resistance of highly crystalline and amorphous polymers. Interestingly, for untoughened POM/PLA blend the initial modulus was very close to the values represented by pure PLA, while for EBA-modified blends the room temperature values were closer to the stiffness of pure POM.

Figure 4.

The results of the DMTA analysis (storage modulus and tan δ): (A) for unmodified samples; (B) for WF-modified materials. (C) The results of the head deflection temperature (HDT) measurements.

Figure 4.

The results of the DMTA analysis (storage modulus and tan δ): (A) for unmodified samples; (B) for WF-modified materials. (C) The results of the head deflection temperature (HDT) measurements.

For all of the POM/PLA type blends the initial stiffness values starts to decrease as the temperature increases. The plots comparison is revealing that the modulus drop was less rapid than for pure PLA; however the visible stiffness reduction was observed at 40°C. The faster softening of the POM/PLA blends is confirmed when analysis the tan δ plots, where the peak of the curve was recorded around 63 °C, comparing to 70 °C for pure PLA. In contrast to the sharp PLA peak the shape of the plots for POM/PLA-based blends is broader, which suggests that the glass transition for this type of materials is more gradual. Nevertheless, the position of the peak on the curve confirms at least partial miscibility of the POM/PLA system. The DMTA results obtained for the WF-reinforced samples (see

Figure 4B) are collected for molded materials and annealed specimens. It is quite clear that the plot appearance for molded samples was very similar to the unreinforced samples. The only noticeable difference was visible increase in the storage modulus values, especially at the initial temperature range of the test. More visible differences are recorded for annealed materials since the difference in crystallinity is strongly influencing the thermomechanical performance. The storage modulus values observed close to the room temperature are almost similar for molded and annealed samples; however the main differences are revealed in the glass transition region. In contract to reference POM/PLA materials, the change in stiffness in the glass transition area does not differ from the intensity change in other areas of the plots. For untoughened POM/PLA blend the storage modulus values are only slightly lower than for pure POM. The tan δ plots are revealing large reduction of the T

g peak area, since the increasing crystallinity of the PLA phase is leading to reduction in amorphous phase mobility. Nevertheless, the position of these peaks has not changed in relation to the reference samples, which confirms that the heating(annealing) procedure mainly affects the content of the crystalline phase, and not the phase transitions occurrence.

The DMTA analysis allows for a better understanding of HDT measurement results (

Figure 4C). The comparison was prepared for unfilled blends and WF-reinforced composites, where for both types of materials the results are reflecting the properties before and after the annealing procedure. The HDT values for molded blends ranged from 50 °C to 55°C, which is very close to the results reported for pure PLA (HDT ≈54°C). Interestingly, the HDT for pure POM resin was 91 °C, while the annealing procedure resulted in an increase to 105 °C. This confirms that even for highly crystalline materials such as POM or polyamides, it is possible to further improve the properties by thermal processes. For POM/PLA blends the annealing was also increasing the HDT results, where the best results for unmodified POM/PLA samples reached 77°C. However, still the observed increase was relatively small and still the HDT results are far below the thermal resistance for pure POM. After the introduction of WF filler all of the results obtained for unreinforced samples were significantly increased. For example, the HDT results for POM/WF reached 126 °C, which is 35 °C higher than the results for unmodified POM. For POM/PLA-based composites the HDT values are also increased by minimum of 25 °C. The additional annealing treatment was even more effective that the WF addition, especially for POM/PLA-based composites. Again, the highest HDT of 138 °C was recorded for POM/WF samples; however, even for toughened POM/PLA composites, the results are close to 125 °C, which is an increase of over 45 °C compared to untreated WF composites.

4. Discussion

Taking into account the previous publications covering the use of natural fillers as an additive for POM [

12,

29,

30,

31], it is worth noting that the main emphasis in the previous research was on obtaining the highest possible reinforcement factor, while the main advantages of using POM as a technical polymer, i.e., its high thermal resistance, were often omitted. Preliminary tests conducted for unmodified POM showed that in the case of fillers in milled and powdered form, the effectiveness of reinforcement is very insignificant for unmodified POM, which is visible by a relatively small increase in stiffness and a decrease in strength. This is relatively typical behavior because due to the small shape factor of the particles of this type. The length-to-diameter ratio is very low, which negatively affects the mechanics of the material deformation process. It is clear that for POM/PLA blends some further research regarding the utilization of traditional glass/carbon reinforcement might reveal higher effectiveness for synthetic materials [

32,

33,

34]. However, the sustainability factors of the resulting composite will be less favorable, especially for carbon fiber usage [

35].

The second stage of the conducted research involved the modification of POM with the addition of PLA. The concept of using PLA as a component of a blend with engineering polymers is always associated with the risk of reducing the thermal resistance of the resulting material [

27,

36,

37,

38,

39]; in particular, the second component of the system is a high-crystalline polymer such as PP , PE, PA, or PBT [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The results confirm this for the obtained materials because the thermomechanical properties of unmodified POM/PLA blends are very similar to pure PLA. Therefore, in the discussed research, we decided to use an important feature of PLA and polyester, i.e. the ability to cold crystallize. The annealing procedure turned out to be very effective even for materials without the addition of wood flour.

5. Conclusions

The results of the study revealed that the utilization of natural fibers during the processing of POM/PLA blends can improve the thermal resistance of the obtained composites; however, other materials characteristics are less favorable. Unlike previous research reports, where POM resin was used as the matrix material for different types of natural fillers, the study revealed that the reinforcing efficiency of cellulose or wood fibers is relatively small; however, when considering the thermomechanical properties, the 20% WF addition was strongly improving the heat deflection (HDT) results. For the most complex systems based on a POM/PLA blend with the addition of EBA impact modifier, it was possible to obtain elongation and impact resistance values close to those of pure POM.

When summarizing the results of the work carried out, it should be emphasized that the research conducted was of a multifaceted nature. The primary goal of trying to produce a polymer material with functional properties similar to commercially available WPC materials has been achieved. An additional aspect related to obtaining increased thermomechanical properties was achieved by heat treatment of materials. However, an equally important value for the discussed research is related to the indication of the potential for materials of this type. Where the results indicated the possibility of using the potential of both main components of the POM and PLA mixture to obtain a material with a very wide possible range of modifications and potential properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.; methodology, J.A. and A.S..; software, J.A. and A.S.; validation, J.A. and A.S.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, J.A. and A.S; data curation, J.A. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and J.A.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and J.A..; visualization, A.S. and J.A.; supervision, J.A.; project administration, J.A.; funding acquisition, J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland as part of the statutory subsidy for the Poznan University of Technology, project No. 0613/SBAD/4888.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tao, Y.; Hadigheh, S.A.; Wei, Y. Recycling of Glass Fibre Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) Composite Wastes in Concrete: A Critical Review and Cost Benefit Analysis. Structures 2023, 53, 1540–1556. [CrossRef]

- Kennerley, J.R.; Kelly, R.M.; Fenwick, N.J.; Pickering, S.J.; Rudd, C.D. The Characterisation and Reuse of Glass Fibres Recycled from Scrap Composites by the Action of a Fluidised Bed Process. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 1998, 29, 839–845. [CrossRef]

- Rahimizadeh, A.; Kalman, J.; Fayazbakhsh, K.; Lessard, L. Recycling of Fiberglass Wind Turbine Blades into Reinforced Filaments for Use in Additive Manufacturing. Compos B Eng 2019, 175, 107101. [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, E.; Kashi, S.; Varley, R.; Wang, X. Recent Progress in Recycling Carbon Fibre Reinforced Composites and Dry Carbon Fibre Wastes. Resour Conserv Recycl 2021, 166, 105340. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Injection-Moulded Biocomposites from Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Recycled Carbon Fibre: Evaluation of Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2014, 27, 1286–1300. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, J.; Tutak, N.; Szostak, M. Polypropylene Composites Obtained from Self-Reinforced Hybrid Fiber System. J Appl Polym Sci 2016, 133. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, J.; Barczewski, M.; Szostak, M. Injection Molding of Highly Filled Polypropylene-Based Biocomposites. Buckwheat Husk and Wood Flour Filler: A Comparison of Agricultural and Wood Industry Waste Utilization. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1881. [CrossRef]

- Zemnukhova, L.A.; Shkorina, E.D.; Fedorishcheva, G.A. Composition of Inorganic Components of Buckwheat Husk and Straw. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 2005, 78, 324–328. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, J.; Krawczak, A.; Wesoły, K.; Szostak, M. Rotational Molding of Biocomposites with Addition of Buckwheat Husk Filler. Structure-Property Correlation Assessment for Materials Based on Polyethylene (PE) and Poly(Lactic Acid) PLA. Compos B Eng 2020, 202. [CrossRef]

- Kuciel, S.; Bazan, P.; Liber-Kneć, A.; Gadek-Moszczak, A. Physico-Mechanical Properties of the Poly(Oxymethylene) Composites Reinforced with Glass Fibers under Dynamical Loading. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kufel, A.; Para, S.; Kuciel, S. Basalt/Glass Fiber Polypropylene Hybrid Composites: Mechanical Properties at Different Temperatures and under Cyclic Loading and Micromechanical Modelling. Materials 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kneissl, L.M.; Gonçalves, G.; Joffe, R.; Kalin, M.; Emami, N. Mechanical Properties and Tribological Performance of Polyoxymethylene/Short Cellulose Fiber Composites. Polym Test 2023, 128, 108234. [CrossRef]

- Król-Morkisz, K.; Karaś, E.; Majka, T.M.; Pielichowski, K.; Pielichowska, K. Thermal Stabilization of Polyoxymethylene by PEG-Functionalized Hydroxyapatite: Examining the Effects of Reduced Formaldehyde Release and Enhanced Bioactivity. Advances in Polymer Technology 2019, 2019, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, J.; Gapiński, B.; Islam, A.; Szostak, M. The Influence of the Hybridization Process on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Polyoxymethylene (POM) Composites with the Use of a Novel Sustainable Reinforcing System Based on Biocarbon and Basalt Fiber (BC/BF). Materials 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Slezák, E.; Ronkay, F.; Bocz, K. Development of an Engineering Material with Increased Impact Strength and Heat Resistance from Recycled PET. J Polym Environ 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.P.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Tuning the Compatibility to Achieve Toughened Biobased Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(Butylene Terephthalate) Blends. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 27709–27724. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shan, P.; Tong, C.; Yan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hao, C. Influence of Reactive Blending Temperature on Impact Toughness and Phase Morphologies of PLA Ternary Blend System Containing Magnesium Ionomer. J Appl Polym Sci 2019, 136, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yuryev, Y.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. A New Approach to Supertough Poly(Lactic Acid): A High Temperature Reactive Blending. Macromol Mater Eng 2016, 301, 1443–1453. [CrossRef]

- Kfoury, G.; Raquez, J.-M.; Hassouna, F.; Odent, J.; Toniazzo, V.; Ruch, D.; Dubois, P. Recent Advances in High Performance Poly(Lactide): From “Green” Plasticization to Super-Tough Materials via (Reactive) Compounding. Front Chem 2013, 1, 1–46. [CrossRef]

- Pluta, M.; Piorkowska, E. Tough and Transparent Blends of Polylactide with Block Copolymers of Ethylene Glycol and Propylene Glycol. Polym Test 2015, 41, 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Nagarajan, V.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Supertoughened Renewable PLA Reactive Multiphase Blends System: Phase Morphology and Performance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2014, 6, 12436–12448. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, J.; Skórczewska, K.; Klozinski, A. Improving the Toughness and Thermal Resistance of Polyoxymethylene/Poly(Lactic Acid) Blends: Evaluation of Structure-Properties Correlation for Reactive Processing. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Xing, C.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y. Miscibility and Double Glass Transition Temperature Depression of Poly(L-Lactic Acid) (PLLA)/Poly(Oxymethylene) (POM) Blends. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 5806–5814. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Qiu, J.; Wu, T.; Shi, X.; Li, Y. Banded Spherulite Templated Three-Dimensional Interpenetrated Nanoporous Materials. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 43351–43356. [CrossRef]

- Mathurosemontri, S.; Thumsorn, S.; Hiroyuki, H. Tensile Properties Modification of Ductile Polyoxymethylene/ Poly (Lactic Acid) Blend by Annealing Technique. Proceedings of ANTEC, Indianapolis 2016, 1222–1227.

- Andrzejewski, J.; Grad, K.; Wiśniewski, W.; Szulc, J. The Use of Agricultural Waste in the Modification of Poly(Lactic Acid)-Based Composites Intended for 3d Printing Applications. the Use of Toughened Blend Systems to Improve Mechanical Properties. Journal of Composites Science 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Yuryev, Y.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Novel Super-Toughened Bio-Based Blend from Polycarbonate and Poly(Lactic Acid) for Durable Applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 105094–105104. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Uribe, A.; Snowdon, M.R.; Abdelwahab, M.A.; Codou, A.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Impact of Renewable Carbon on the Properties of Composites Made by Using Three Types of Polymers Having Different Polarity. J Appl Polym Sci 2021, 138, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yasumlee, N.; Wacharawichanant, S. Morphology and Properties of Polyoxymethylene/Polypropylene/ Microcrystalline Cellulose Composites. Key Eng Mater 2017, 751 KEM, 264–269. [CrossRef]

- Espinach, F.X.; Granda, L.A.; Tarrés, Q.; Duran, J.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Mutjé, P. Mechanical and Micromechanical Tensile Strength of Eucalyptus Bleached Fibers Reinforced Polyoxymethylene Composites. Compos B Eng 2017, 116, 333–339. [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Mamun, A.A.; Feldmann, M. Polyoxymethylene Composites with Natural and Cellulose Fibres: Toughness and Heat Deflection Temperature. Compos Sci Technol 2012, 72, 1870–1874. [CrossRef]

- Mathurosemontri, S.; Uawongsuwan, P.; Nagai, S.; Hamada, H. The Effect of Processing Parameter on Mechanical Properties of Short Glass Fiber Reinforced Polyoxymethylene Composite by Direct Fiber Feeding Injection Molding Process. Energy Procedia 2016, 89, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, D. Development of Sustainable Polyoxymethylene-Based Composites with Recycled Carbon Fibre: Mechanical Enhancement, Morphology, and Crystallization Kinetics. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2014, 33, 294–309. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, X. The Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Nitric Acid-Treated Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyoxymethylene Composites. J Appl Polym Sci 2015, 132, n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Heil, J.P. Study and Analysis of Carbon Fiber Recycling. North Carolina State University 2011, Master Thesis.

- Yuryev, Y.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Novel Biocomposites from Biobased PC/PLA Blend Matrix System for Durable Applications. Compos B Eng 2017, 130, 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Codou, A.; Anstey, A.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Novel Compatibilized Nylon-Based Ternary Blends with Polypropylene and Poly(Lactic Acid): Morphology Evolution and Rheological Behaviour. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 15709–15724. [CrossRef]

- Anstey, A.; Codou, A.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Novel Compatibilized Nylon-Based Ternary Blends with Polypropylene and Poly(Lactic Acid): Fractionated Crystallization Phenomena and Mechanical Performance. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2845–2854. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Ogunsona, E.O.; Anstey, A.; Torres Galvez, S.E.; Codou, A.; Jubinville, D.F. Biocarbon and Nylon Based Hybrid Carbonaceous Biocomposites and Methods of Making Those and Using Thereof 25/01/2018, US 2018/0022921 A1.

- Mamun, A.A.; Heim, H.-P.; Beg, D.H.; Kim, T.S.; Ahmad, S.H. PLA and PP Composites with Enzyme Modified Oil Palm Fibre: A Comparative Study. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2013, 53, 160–167. [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, J.P.; Luyt, A.S.; Tábi, T.; Kovács, J. Comparison of Injection Moulded, Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composites with PP and PLA as Matrices. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2012, 25, 927–948. [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Franciszczak, P.; Meljon, A. High Performance Hybrid PP and PLA Biocomposites Reinforced with Short Man-Made Cellulose Fibres and Softwood Flour. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2015, 74, 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Peltola, H.; Pääkkönen, E.; Jetsu, P.; Heinemann, S. Wood Based PLA and PP Composites: Effect of Fibre Type and Matrix Polymer on Fibre Morphology, Dispersion and Composite Properties. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2014, 61, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Gu, Q. Synthesis and Characterization of Triblock Copolymer PLA-b-PBT-b-PLA and Its Effect on the Crystallization of PLA. RSC Adv 2013, 3, 18464. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).