1. Introduction

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a biological process that enables epithelial cells to acquire mesenchymal properties, such as increased motility, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis[

1,

2,

3]. EMT is a key process in embryonic development, tissue repair, and organogenesis, but it can also be hijacked by cancer cells to promote tumor progression and metastasis[

4,

5,

6]. The EMT process involves the downregulation of epithelial markers, such as E-cadherin[

7,

8], and the upregulation of mesenchymal markers, such as vimentin and N-cadherin[

9,

10]. The loss of cell adhesion and the acquisition of migratory and invasive properties are characteristic of the mesenchymal phenotype.

EMT is a complex process that is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and transcription factors. Various growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular matrix components can activate EMT signaling pathways by binding to specific receptors on the cell surface and converge signaling pathways on a set of transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and ZEB1/2, that regulate epithelial related genes expression[

11,

12,

13,

14]. At the same time, these transcription factors might induce the expression of mesenchymal genes, leading to the acquisition of mesenchymal properties. In addition to the transcriptional regulation of EMT, post-transcriptional mechanisms, such as alternative splicing, microRNA regulation[

15], and protein degradation, have also been shown to play important roles in EMT regulation[

16].

EMT is also involved in the maintenance of cancer stem cells (CSCs), a subpopulation of cancer cells that hold stem-like properties and are believed to be responsible for tumor initiation, progression, and recurrence[

17]. CSCs have been shown to have higher levels of EMT markers, such as Snail and vimentin, and increased drug resistance compared to non-CSCs. The presence of CSCs in tumors has become an important target for cancer treatment, as they may be responsible for drug resistance and disease relapse[

4,

18,

19].

Moreover, recent studies have expanded our understanding of the interplay between EMT and the tumor microenvironment. This dynamic environment comprises a diverse of cell types, including cancer-associated fibroblasts, immune cells, and endothelial cells, alongside extracellular matrix components and soluble factors[

20,

21]. Interactions between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment trigger signaling pathways that orchestrate EMT. These signaling cascades not only influence the phenotypic transformation of cancer cells but also play a pivotal role in the broader context of tumor development.

The contribution of EMT to tumor progression and metastasis has rendered it an attractive target for cancer therapy. Several strategies aimed at inhibiting or reversing EMT have been explored as potential therapeutic approaches. Small molecule inhibitors targeting EMT-associated signaling pathways, including TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, and Hedgehog, have shown promise in preclinical studies[

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The inhibitors have demonstrated in moderating EMT and impeding tumor progression. However, these inhibitors have yet to be clinically approved due to their limited efficacy and potential toxicity. The balance between effectively inhibiting EMT and maintaining normal cellular function shows a substantial obstacle in the clinical development of these inhibitors.

Natural compounds targeting EMT properties have also been identified as potential therapeutic agents. For example, curcumin, a polyphenol isolated from turmeric, has been shown to inhibit EMT and promote MET (mesenchymal-epithelial transition) in various cancer cell lines. Other natural compounds, such as resveratrol, sulforaphane, and genistein, have also been reported to inhibit EMT and promote MET in cancer cells[

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

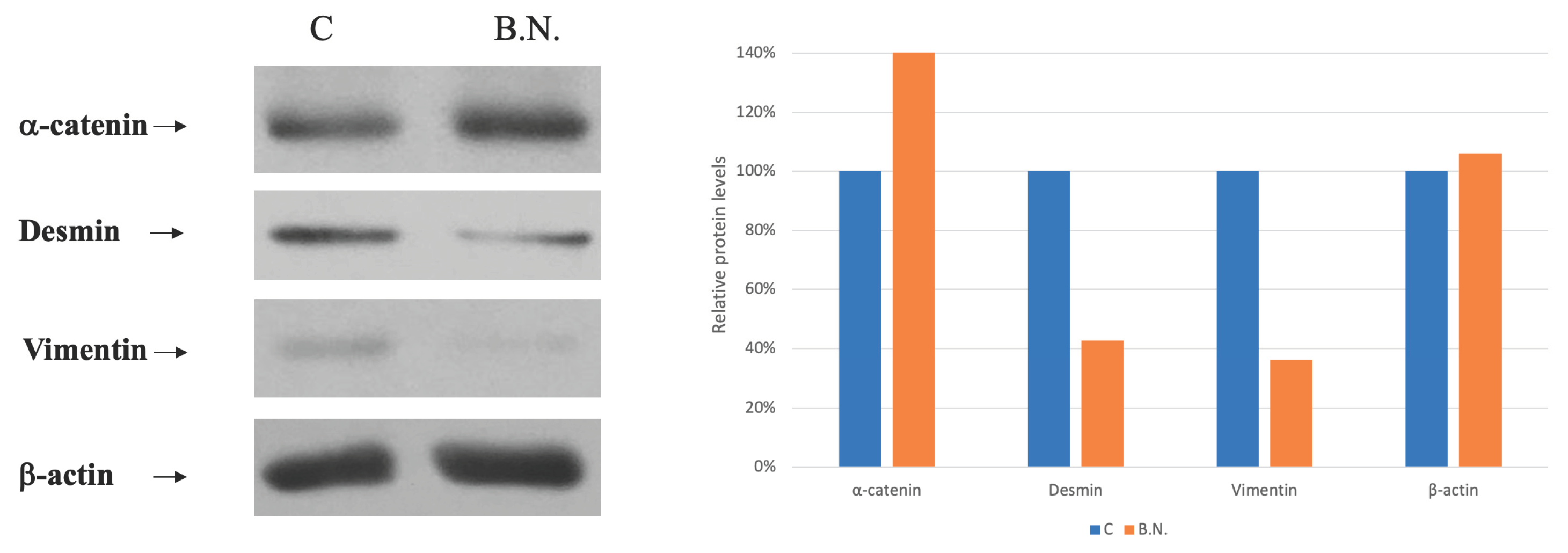

In recent years, the therapeutic potential of natural compounds derived from medicinal plants has garnered significant attention in cancer research. One such compound is Boehmeria Nivea Extract (BNE-RRC), also known as BNE-101, which is derived from the root extract of Boehmeria nivea, a plant traditionally used in Chinese medicine. Our previous studies have demonstrated the multifaceted anti-cancer properties of BNE-RRC. Specifically, BNE-RRC has been shown to inhibit cancer cell growth, exert anti-inflammatory effects, prevent drug resistance in cancer cells, and suppress the expression of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), a key protein involved in the unfolded protein response and associated with cancer progression and chemoresistance. The anti-cancer effects of BNE-RRC are attributed to its ability to target multiple signaling pathways involved in cancer development and progression. For instance, BNE-RRC has been found to downregulate the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), a pro-inflammatory enzyme that is often upregulated in cancer and contributes to tumor growth and metastasis. Additionally, BNE-RRC can modulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which plays a critical role in cancer cell proliferation and survival. By inhibiting the Akt signaling pathway, BNE-RRC induces apoptosis in cancer cells, further contributing to its anti-cancer activity. In this study, we focused on test the effect of BNE-RRC on reverse epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), with the purpose of regaining chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity, such as Doxorubicin, in tumor cell lines. We found that BNE-RRC could suppress the expression of EMT markers, such as Vimentin and Desmin, and increase the expression of MET marker, α-catenin. Thus, we suggest that BNE-RRC could play a role in inhibiting EMT and triggering MET, ultimately leading to reverse EMT and the increase of chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity. These findings suggest that BNE-RRC may be a promising therapeutic agent for the treatment of cancer, as it not only inhibits tumor growth but also enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy.

3. Discussion

Plants and botanicals provides an enornous source of natural compounds that have potential therapeutic applications. One such compound is BNE-RRC, a root extract from Boehmeria nivea, which has been discovered to inhibit cancer cell growth. Previous studies have shown that BNE-RRC treated cancer cells result in the inhibition of various proteins associated with cancer development and survival. In addition, BNE-RRC has been found to reverse epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer cells, which is known to play a important role in tumor progression and metastasis. EMT is a cellular phenomenon whereby epithelial cells lost their characteristic morphology and acquire mesenchymal properties, leading to increased cell motility, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis. EMT is a complex process is regulated through the activation of EMT-inducing transcription factors (EMT-TFs), including zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factors such as SNAIL, ZEB1, SLUG and the basic helix-loop-helix factors TWIST1 and TWIST2[

35,

36,

37]. The expression of these EMT-TFs is tightly regulated by various signaling pathways, non-coding RNAs, and extracellular mediators[

38,

39,

40]. EMT is classified into three types based on the biological context in which it occurs. Type I EMT is involved in embryonic development, type II EMT is observed during tissue regeneration and wound healing, and type III EMT occurs during carcinoma progression. In cancer, EMT is associated with the acquisition of stem cell-like properties, increased resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and the ability to form distant metastases[

41,

42,

43]. Several studies have shown that blocking EMT or reversing EMT to induce mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) can enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy in cancer[

41,

44,

45]. MET is a cellular process that is the opposite of EMT, where mesenchymal cells transit back to their epithelial phenotype, resulting in increased cell-cell adhesion, decreased cell motility, and increased sensitivity to apoptosis.

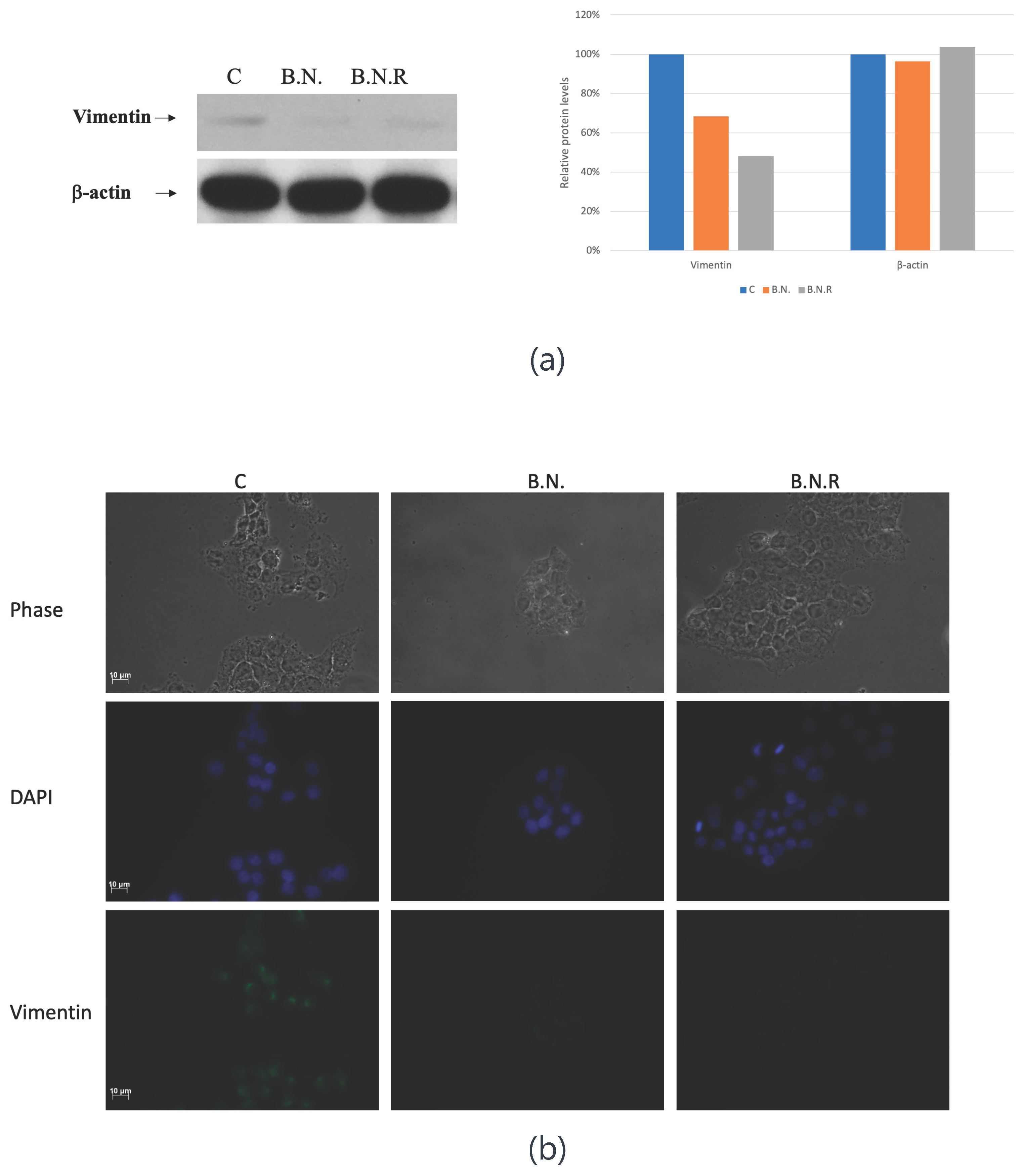

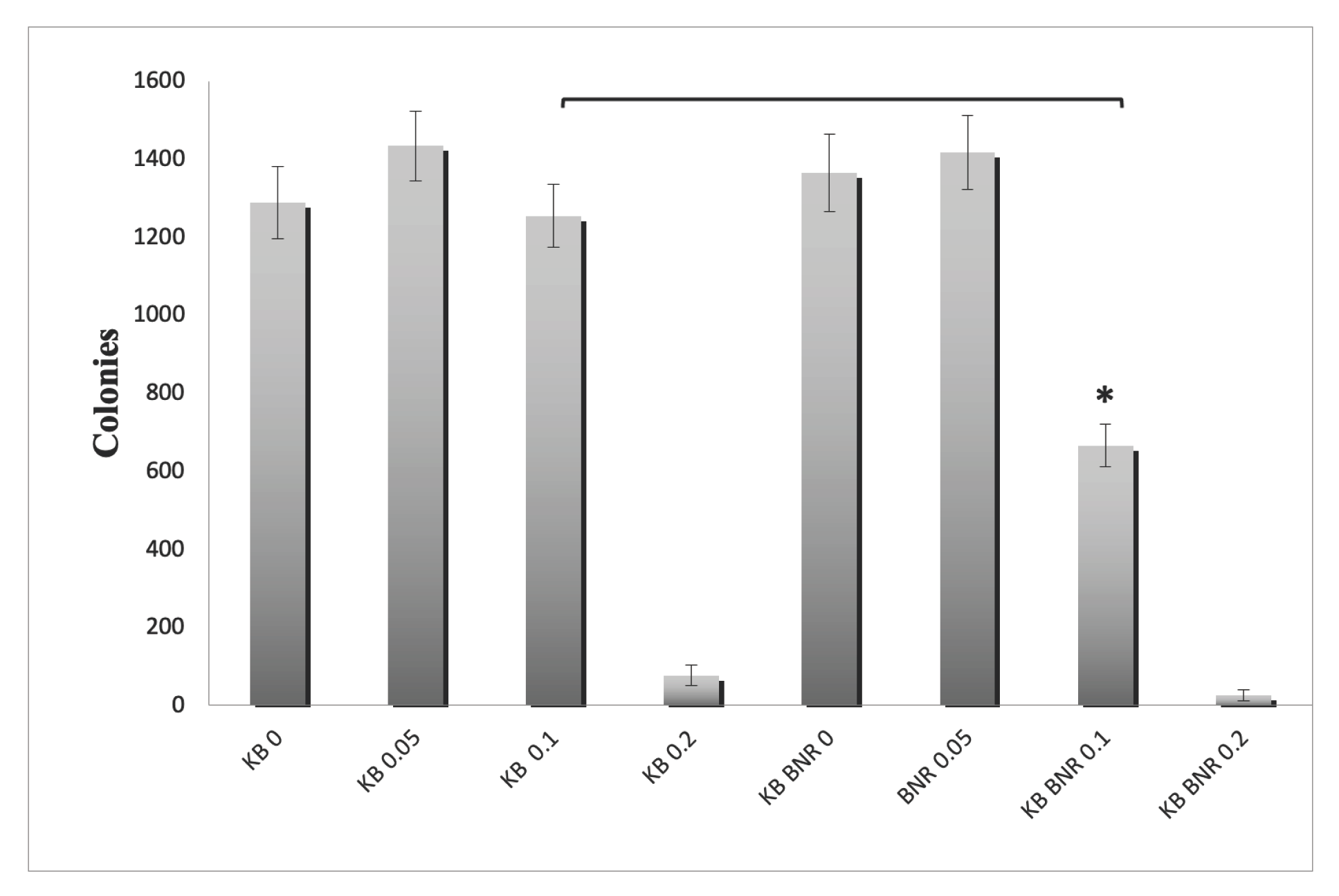

A previous study showed that BNE-RRC inhibits cancer cell growth through various mechanisms, including the suppression of inflammatory proteins, COX2, the regulation of cancer development regulation protein, β-catenin, the inhibition of cancer cell survival protein, AKT, the downregulation of anti-apoptotic protein GRP78, and the reduction of invasion-associated protein MMP9[

46]. In addition to its anti-cancer properties, BNE-RRC could reverse EMT in cancer cells by suppressing of mesenchymal markers, such as Desmin and Vimentin, and increase the expression of the MET marker α-catenin. This reversal enhances the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy, particularly to doxorubicin. In the study also showed that prolonged treatment with BNE-RRC to cancer cells maintained the MET characteristics of treated cells for over four weeks leading to the gain of chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity. The study suggests that converting EMT to MET contributes to the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs treatment in cancer. The study presented here demonstrates the potential of BNE-RRC as a promising therapeutic candidate for cancer treatment. Its capability to inhibit cancer cell growth and reverse EMT, leading to an epithelial phenotype in cancer cells, highlights significance as reversal of EMT contribute to increased sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs, which is a crucial aspect in the treatment of cancer.

Further research is needed to unravel the mechanism by which BNE-RRC triggers the morphological transition and the impact of this transition on cancer cells. Nevertheless, the promising results of this study suggest that BNE-RRC has significant potential as a therapeutic candidate for cancer treatment. In addition, the results of this study may have stronger implications for the development of cancer therapies through targeting EMT. EMT plays a significant role in cancer progression, metastasis, and the development of therapeutic resistance. By understanding the mechanisms regulating this program and developing therapies that can reverse it could be able to enhance cancer treatment and reduce the burden on patients. Overall, the study presented here provides important insights into the potential of BNE-RRC as a therapeutic candidate for cancer treatment. By targeting the EMT program and inducing the reverse EMT, BNE-RRC has the potential to improve cancer treatment outcomes. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms of action of BNE-RRC and to develop more effective and targeted therapies for cancer treatment.

The plants kindom is an abundant source of numerous nature compounds for human heaith research. In this study, we employed BNE-RRC to effectively inhibite cancer cell growth by regulating key proteins associated with cancer development, growth, and survival, such as COX2, AKT, GRP78, and MMP9. Additionally, we observed a reversal of EMT to an epithelial phenotype in cancer cells. EMT has significant consequences for clinical oncology, as it ehhances tumor cell resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. It plays an important role in tumor progression and metastasis, making this process a target for cancer therapy. Upon the development toward the EMT, the expression of cellular markers such as E-cadherin and α-catenin expression are suppressed while the expression of mesenchymal markers, including N-cadherin, Vimentin, and Desmin, are induced [

7,

8,

47,

48]. Blockage of EMT or reversal of EMT can restore the sensitivity of tumor cells to several therapeutic regimens. This study found that BNE-RRC suppress the expression of mesenchymal markers, such as Vimentin and Desmin, and increase the expression of the MET marker α-catenin, thereby reversing EMT. EMT programs are classified into three types based on the biological context: type I EMT is involved in embryonic development, type II EMT is observed during tissue regeneration and wound healing, and type III EMT occurs during carcinoma progression. EMT programs can operate in normal tissues and neoplastic growths, depending on which EMT-TFs are expressed. EMT-TFs, such as SNAIL, ZEB1, SLUG, TWIST1, and TWIST2[

15,

23,

37,

49]. These EMT-TFs are tightly regulated via oncogenic signaling, non-coding RNAs, and extracellular moleculars. It remains to be established whether BNE-RRC treatment regulates the expression of these key EMT-TFs, controlling both EMT and the reverse process of MET.

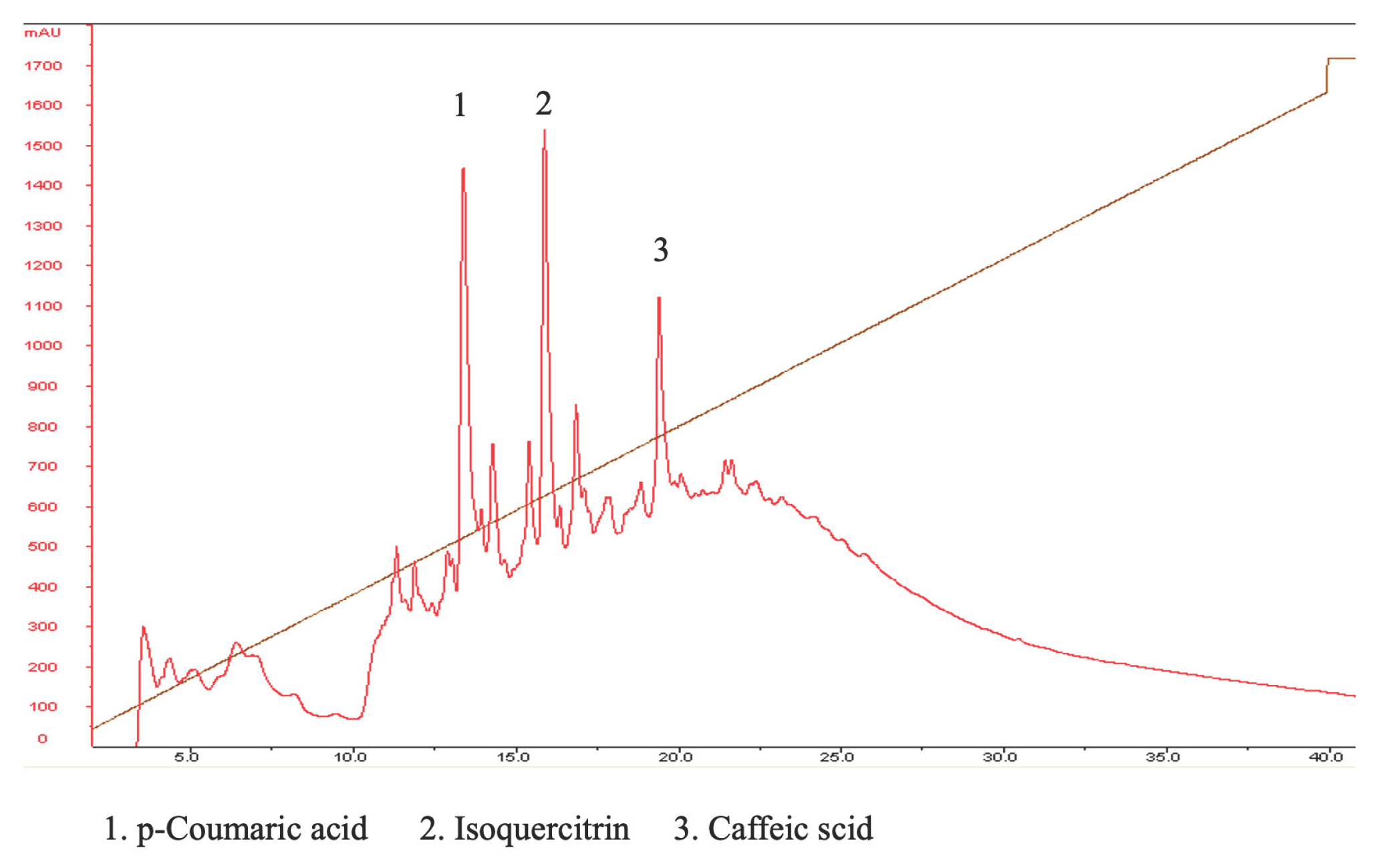

In this study, we investigated the composition of BNE-RRC using HPLC and identified several compounds, including p-coumaric acid, isoquercitrin, and caffeic acid. Although the anti-cancer effects of BNE-RRC might have mixture of compounds, the individual these compounds to the observed effects need further investigation. P-coumaric acid, a phenolic acid found in BNE-RRC, has been reported to exhibit anti-cancer properties in various studies. For instance, it has been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation in cancer. Our ongoing research aims to compare the anti-cancer effects of p-coumaric acid with those of BNE-RRC to elucidate its role in the extract's overall activity. Isoquercitrin, a flavonoid also present in BNE-RRC, has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities. Caffeic acid, another phenolic compound identified in BNE-RRC, has been a subject of debate regarding its anti-cancer effects. While some studies suggest that caffeic acid may exhibit anti-cancer activity, others argue that its effects may be context-dependent and vary across different types of cancer cells. The HPLC analysis of BNE-RRC compounds provides valuable insights into the potential bioactive components contributing to its anti-cancer effects. Further studies are needed to elucidate the individual roles of these compounds and their synergistic interactions within the extract.

Our findings provide valuable insight into sustained effects of BNE-RRC treatment, which can reverse EMT and maintain the MET phenotype for over four weeks, contributing to an increased sensityt ton chemotherapeutic drug. The EMT program is known for generating neoplastic stem cells and elevating therapeutic resistance, where BNE-RRC reverses this program and providing a potyentia; avenue for cancer therapy. The convertion of EMT to MET by BNE-RRC appears to establish a counterregulatory mechanism against cancer development and metastasis, this transition contributes to the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer patients. BNE-RRC suppresses typical mesenchymal markers, such as Desmin and Vimentin, suggesting a unique role of BNE-RRC in regulating MET. Our results suggest that BNE-RRC induces the morphological changes in tumors, reducing the mesenchymal stage and increasing their susceptibility to various treatments, including chemotherapies. However, the precise mechanism by which BNE-RRC triggers this transition requires further investigation in future studies.4. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

The cell line of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, KB CRL-3596 (ATCC CCL-17), was maintained at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2. The cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (supplied by Invitrogen Corporation, N.Y., U.S.A) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin, each at 25 U/mL).

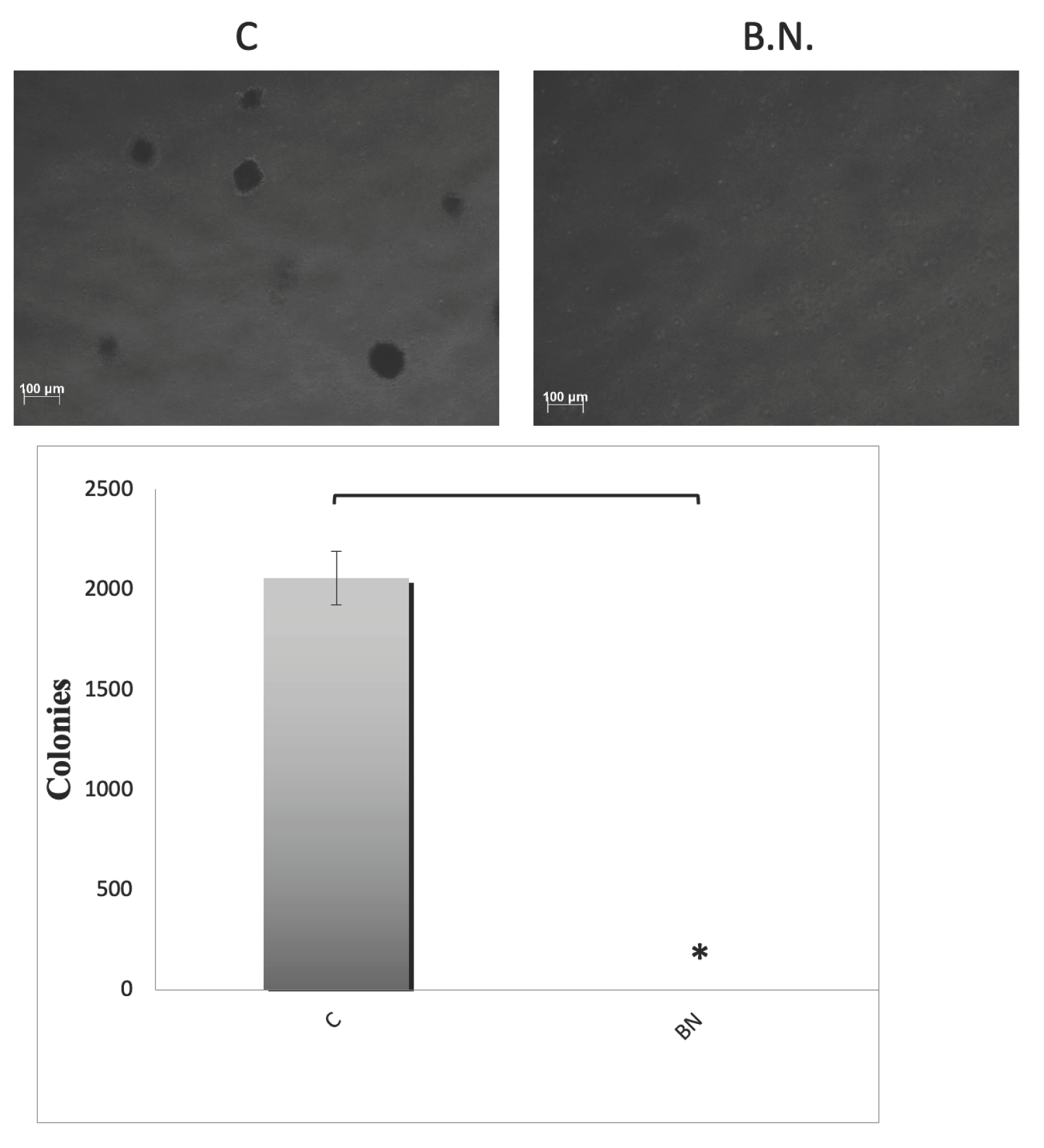

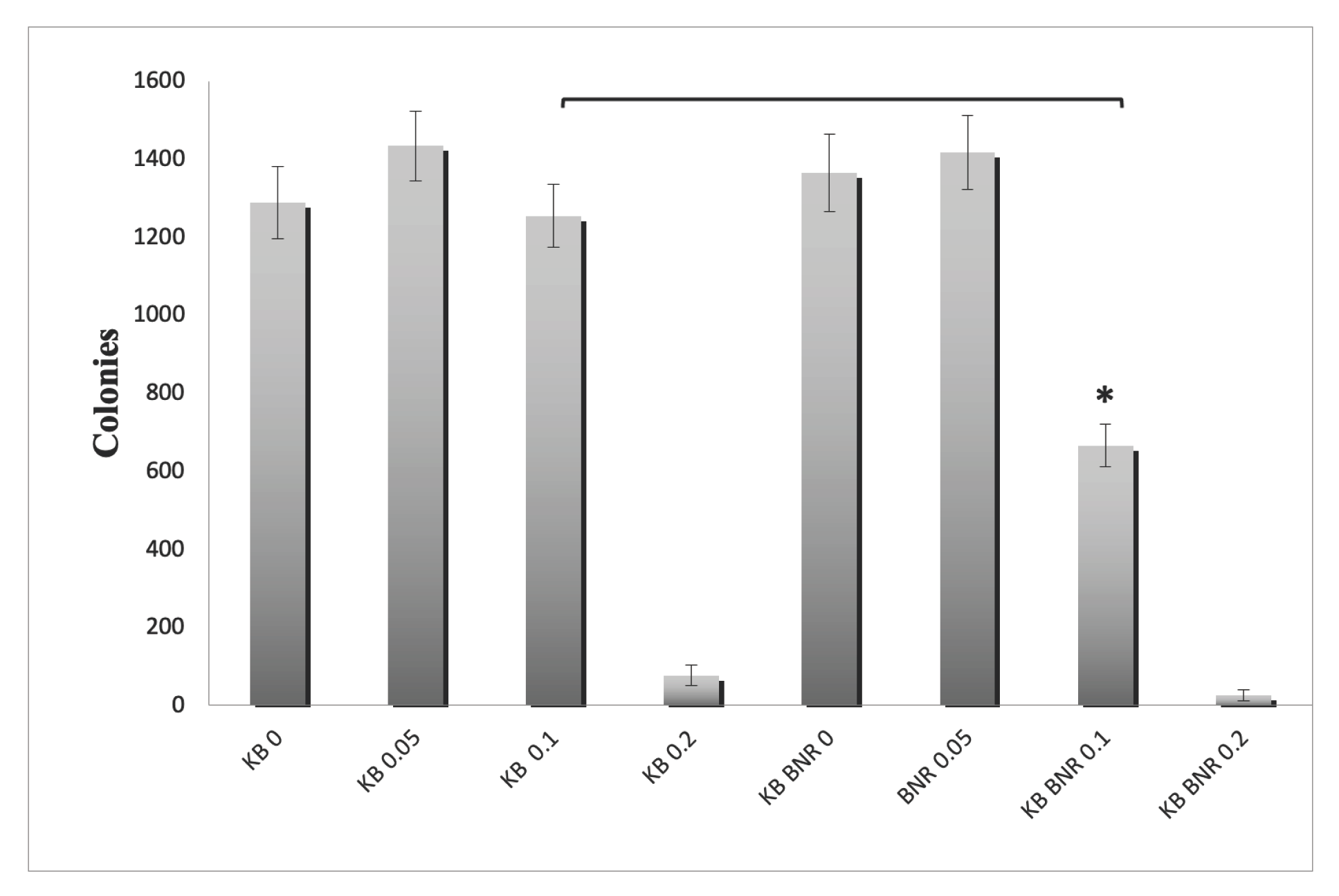

4.2. Soft Agar Assay

The cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.3% Agar Noble (BD, Difco, MD, USA) and then seeded onto a base layer comprising 0.5% Agar Noble. The assay was conducted in 6-well plates, seeding approximately 2,500 to 10,000 cells per well, with each condition replicated three times. After 2 weeks of incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the colonies were stained with Iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT) solution, photographed, and manually counted. The quantification of colonies was performed using an inverted light microscope at a magnification of 40×. The results are presented as the average number of colonies ± standard error (SE) calculated from six fields across three independent wells.

4.3. Western Blot Analysis

Lysates of the cells were prepared using IP buffer containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM NaF, protease inhibitors, and 1 mM sodium vanadate. Immunoblotting was conducted with the specified antibodies. For harvesting, cells were lysed in a buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 2 mM EDTA, supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, 10 ng/ml leupeptin, 50 mM NaF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The total proteins were then resolved on SDS-PAGE and the specific protein bands were detected using an ECL chemiluminescent detection system (Amersham).

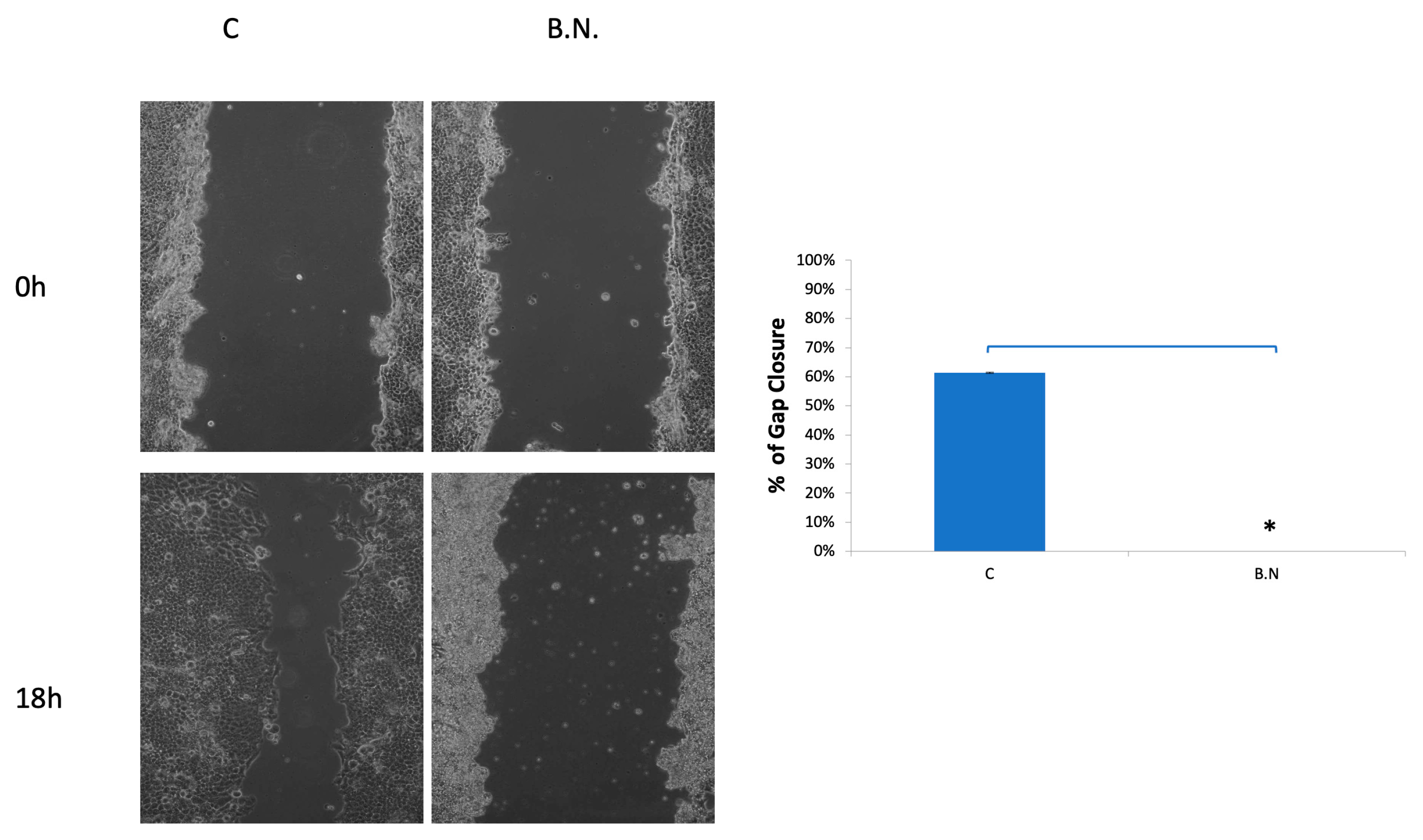

4.4. Wound Healing Assay

KB cells were plated on 10-cm dishes and grown until they reached confluency. A scratch was then made across the cell monolayer using the tip of a 200-µl pipette. The cells were subsequently incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Images of the scratch wound were captured at 18 hours post-scratch using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope.

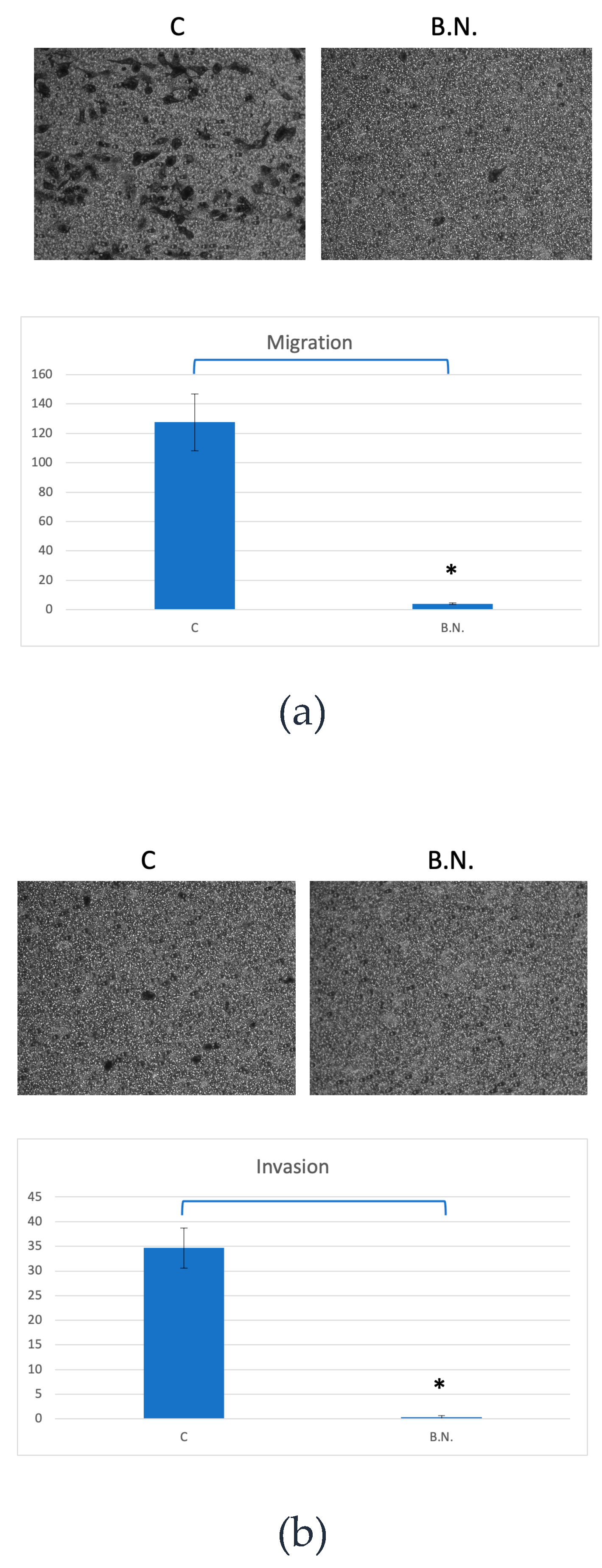

4.5. Cell Migration Assay

A Boyden chamber migration assay was conducted by adding DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS to the lower compartment of the chamber. The chamber was equipped with polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate membranes featuring 8-µm pores (Neuro Probes, Inc.). To the upper compartment, 1,500 cells per well were seeded in serum-free DMEM. The assembly was then incubated for 24 hours at 37°C, facilitating the cells' migration through the membrane to the lower compartment. Following incubation, the membranes were stained with Giemsa stain, and the migrated cells in the lower chamber were quantified using a counting grid inserted into the eyepiece of a phase contrast microscope.

4.6. Telomerase Activity Assay

Telomerase activity was assessed using the TRAPEZE® Gel-Based Telomerase Detection Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell extracts were prepared following the kit's instructions. Briefly, KB cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1X CHAPS Lysis Buffer, and the protein concentration was determined. Tissue samples were homogenized in 1X CHAPS Lysis Buffer. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. For the telomerase activity assay, aliquots of the supernatant were quick-frozen on dry ice and stored at -85°C to -75°C. The extracts were aliquoted into small volumes to prevent frequent freeze-thaw cycles. Each assay was performed with 2 µL of cell extract, corresponding to 0.5 µg of total protein for cell extracts and 10-500 ng/µL for tissue extracts. Telomerase activity was evaluated by incubating the samples at 85°C for 10 minutes to inactivate telomerase, followed by PCR amplification.

4.7. HPLC Conditions

The analysis was performed on a Amersham HPLC system equipped with a reverse-phase INNO C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). The volume injected was 100 μl, utilizing a DAD-WR detector for the analyses. The column's temperature was consistently maintained at 25°C, and the flow rate was adjusted to 1 ml/min. Detection occurred at a wavelength of 240 nm, employing a gradient elution technique with a binary mobile phase. The composition of the mobile phase included (A) 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water and (B) 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in 80% acetonitrile (ACN). The gradient program commenced with 95% A, holding for 0 minutes, then linearly transitioned to 100% B across 40 minutes. Afterward, the system was returned to 0% B within 5 minutes and maintained for 60 minutes before reverting to the initial condition of 95% A. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of Oral Cancer growth by BNE-RRC in soft agar culture assay. The effects of BNE-RRC on the proliferation of oral cancer cells (KB) in an anchorage-independent growth condition are shown. The cells were treated with BNE-RRC, and their growth was examined after 14 days of culture, followed by staining with INT. BNE-RRC at a concentration of 2mg/ml significantly reduced the number and size of colonies compared to the control group. In this figure, "C" denotes the control group, and "B.N." refers to the group treated with BNE-RRC. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for colony formation was 0.0010 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and BNE-RRC treated groups. These experiments were performed six times; representative data are shown.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of Oral Cancer growth by BNE-RRC in soft agar culture assay. The effects of BNE-RRC on the proliferation of oral cancer cells (KB) in an anchorage-independent growth condition are shown. The cells were treated with BNE-RRC, and their growth was examined after 14 days of culture, followed by staining with INT. BNE-RRC at a concentration of 2mg/ml significantly reduced the number and size of colonies compared to the control group. In this figure, "C" denotes the control group, and "B.N." refers to the group treated with BNE-RRC. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for colony formation was 0.0010 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and BNE-RRC treated groups. These experiments were performed six times; representative data are shown.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of ˙ and Invasion Capacity in Cancer Cells by BNE-RRC. The evaluation of cancer cell migration and invasion capacity under treatment with BNE-RRC through the Boyden chamber membrane assay is shown. The treatment of BNE-RRC significantly suppressed the migration (a) and invasion (b) ability in KB cells. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for migration was 0.0030 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and BNE-RRC treated groups. For invasion, the p-value was 0.0010 (*), also indicating a significant difference. These results demonstrate that BNE-RRC effectively inhibits both migration and invasion capacities of KB cells. These experiments were performed three times; representative data are shown.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of ˙ and Invasion Capacity in Cancer Cells by BNE-RRC. The evaluation of cancer cell migration and invasion capacity under treatment with BNE-RRC through the Boyden chamber membrane assay is shown. The treatment of BNE-RRC significantly suppressed the migration (a) and invasion (b) ability in KB cells. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for migration was 0.0030 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and BNE-RRC treated groups. For invasion, the p-value was 0.0010 (*), also indicating a significant difference. These results demonstrate that BNE-RRC effectively inhibits both migration and invasion capacities of KB cells. These experiments were performed three times; representative data are shown.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of cancer cell migration by BNE-RRC. The wound healing assay was employed to evaluate the effect of BNE-RRC on cell migration. Confluent cancer cells were scraped with a sterile plastic pipette with or without BNE-RRC treatment. In the left panel, representative photos show the wound healing progress after 18 hours for control cells and cells treated with BNE-RRC (B.N.). The right panel presents the percentage of gap closure; control cells achieved 61% gap closure, whereas B.N. treated cells exhibited no gap closure after 18 hours of treatment. This data was calculated from 10 fields for each condition. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for gap closure was 0.0010 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and BNE-RRC treated groups. These experiments were performed four times; representative data are shown.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of cancer cell migration by BNE-RRC. The wound healing assay was employed to evaluate the effect of BNE-RRC on cell migration. Confluent cancer cells were scraped with a sterile plastic pipette with or without BNE-RRC treatment. In the left panel, representative photos show the wound healing progress after 18 hours for control cells and cells treated with BNE-RRC (B.N.). The right panel presents the percentage of gap closure; control cells achieved 61% gap closure, whereas B.N. treated cells exhibited no gap closure after 18 hours of treatment. This data was calculated from 10 fields for each condition. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for gap closure was 0.0010 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and BNE-RRC treated groups. These experiments were performed four times; representative data are shown.

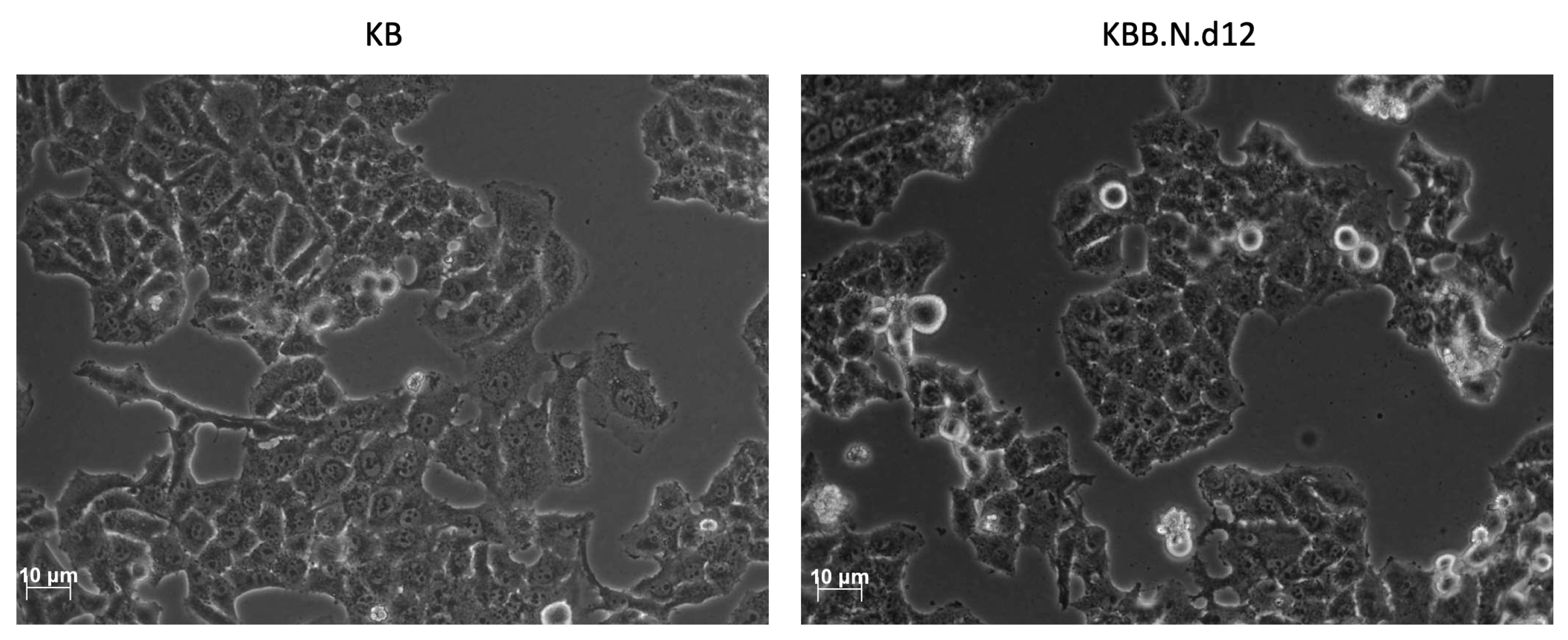

Figure 4.

Induction of Morphological changes in KB cells by BNE-RRC. The effect of BNE-RRC on cell morphology was evaluated through phase-contrast microscopy. Untreated control KB cells (left panel) exhibited a mesenchymal-like morphology with non-uniform cell shapes. In contrast, KB cells treated with BNE-RRC for 12 days (right panel) acquired a more rigid and uniform epithelial-like morphology.

Figure 4.

Induction of Morphological changes in KB cells by BNE-RRC. The effect of BNE-RRC on cell morphology was evaluated through phase-contrast microscopy. Untreated control KB cells (left panel) exhibited a mesenchymal-like morphology with non-uniform cell shapes. In contrast, KB cells treated with BNE-RRC for 12 days (right panel) acquired a more rigid and uniform epithelial-like morphology.

Figure 5.

Induction of MET in cancer cells by BNE-RRC. KB cells were treated with BNE-RRC, and western blot analysis was performed to detect the expression of key proteins involved in the EMT/MET process. BNE-RRC treated cancer cells exhibited epithelial morphology, suggesting a reversal from EMT to MET. The expression of the epithelial protein α-catenin was significantly induced in BNE-RRC treated cancer cells, while the expression of mesenchymal markers Desmin and Vimentin was down-regulated. The relative protein expression levels are shown in the right panel. These results suggest that BNE-RRC has the potential to reverse EMT and induce MET in cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Induction of MET in cancer cells by BNE-RRC. KB cells were treated with BNE-RRC, and western blot analysis was performed to detect the expression of key proteins involved in the EMT/MET process. BNE-RRC treated cancer cells exhibited epithelial morphology, suggesting a reversal from EMT to MET. The expression of the epithelial protein α-catenin was significantly induced in BNE-RRC treated cancer cells, while the expression of mesenchymal markers Desmin and Vimentin was down-regulated. The relative protein expression levels are shown in the right panel. These results suggest that BNE-RRC has the potential to reverse EMT and induce MET in cancer cells.

Figure 6.

Effects of BNE-RRC Treatment on Epithelial Phenotype in Cancer Cells. (a) Western blot analysis showing reduced expression of the mesenchymal marker Vimentin in KB cells treated with BNE-RRC for 14 days (B.N.) compared to untreated cells. After removal of BNE-RRC treatment, cancer cells maintained low levels of Vimentin expression for an additional 4 weeks (B.N.R.), indicating a lasting effect of BNE-RRC treatment on inducing epithelial morphology. The relative protein expression levels are shown in the right panel. (b) Immunofluorescence analysis of cancer cells treated with BNE-RRC for 14 days (B.N.) and then cultured for an additional 4 weeks without BNE-RRC treatment (B.N.R.). The BNE-RRC treated cells exhibit low levels of Vimentin.

Figure 6.

Effects of BNE-RRC Treatment on Epithelial Phenotype in Cancer Cells. (a) Western blot analysis showing reduced expression of the mesenchymal marker Vimentin in KB cells treated with BNE-RRC for 14 days (B.N.) compared to untreated cells. After removal of BNE-RRC treatment, cancer cells maintained low levels of Vimentin expression for an additional 4 weeks (B.N.R.), indicating a lasting effect of BNE-RRC treatment on inducing epithelial morphology. The relative protein expression levels are shown in the right panel. (b) Immunofluorescence analysis of cancer cells treated with BNE-RRC for 14 days (B.N.) and then cultured for an additional 4 weeks without BNE-RRC treatment (B.N.R.). The BNE-RRC treated cells exhibit low levels of Vimentin.

Figure 7.

BNE-RRC Treatment Induces Reversion to an Epithelial-Like State in KB Cells, Enhancing Doxorubicin Sensitivity. The graph shows the number of colonies formed by KB cells and KB B.N.R cells (treated with BNE-RRC) in the presence of 0.1 µM doxorubicin. Control KB cells formed an average of 1288.553 colonies, while treatment with 0.1 µM doxorubicin resulted in a slight reduction to 1254.4 colonies, indicating minimal sensitivity to the drug. In contrast, KB B.N.R cells exhibited a significant decrease in colony formation from 1365.333 colonies in the control group to 665.6 colonies upon treatment with 0.1 µM doxorubicin, demonstrating enhanced sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for KB cells and KB B.N.R cells in the presence of 0.1 µM doxorubicin was 0.0050 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and KBB.N.R. treated groups This reversion to an epithelial-like state renders the KB B.N.R cells more susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin, in comparison to the parental KB cells. The data suggest that combining BNE-RRC treatment with a chemotherapeutic drug could potentially overcome therapeutic resistance. These experiments were performed four times; representative data are shown.

Figure 7.

BNE-RRC Treatment Induces Reversion to an Epithelial-Like State in KB Cells, Enhancing Doxorubicin Sensitivity. The graph shows the number of colonies formed by KB cells and KB B.N.R cells (treated with BNE-RRC) in the presence of 0.1 µM doxorubicin. Control KB cells formed an average of 1288.553 colonies, while treatment with 0.1 µM doxorubicin resulted in a slight reduction to 1254.4 colonies, indicating minimal sensitivity to the drug. In contrast, KB B.N.R cells exhibited a significant decrease in colony formation from 1365.333 colonies in the control group to 665.6 colonies upon treatment with 0.1 µM doxorubicin, demonstrating enhanced sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic agent. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t-test. The p-value for KB cells and KB B.N.R cells in the presence of 0.1 µM doxorubicin was 0.0050 (*), indicating a significant difference between the control and KBB.N.R. treated groups This reversion to an epithelial-like state renders the KB B.N.R cells more susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin, in comparison to the parental KB cells. The data suggest that combining BNE-RRC treatment with a chemotherapeutic drug could potentially overcome therapeutic resistance. These experiments were performed four times; representative data are shown.

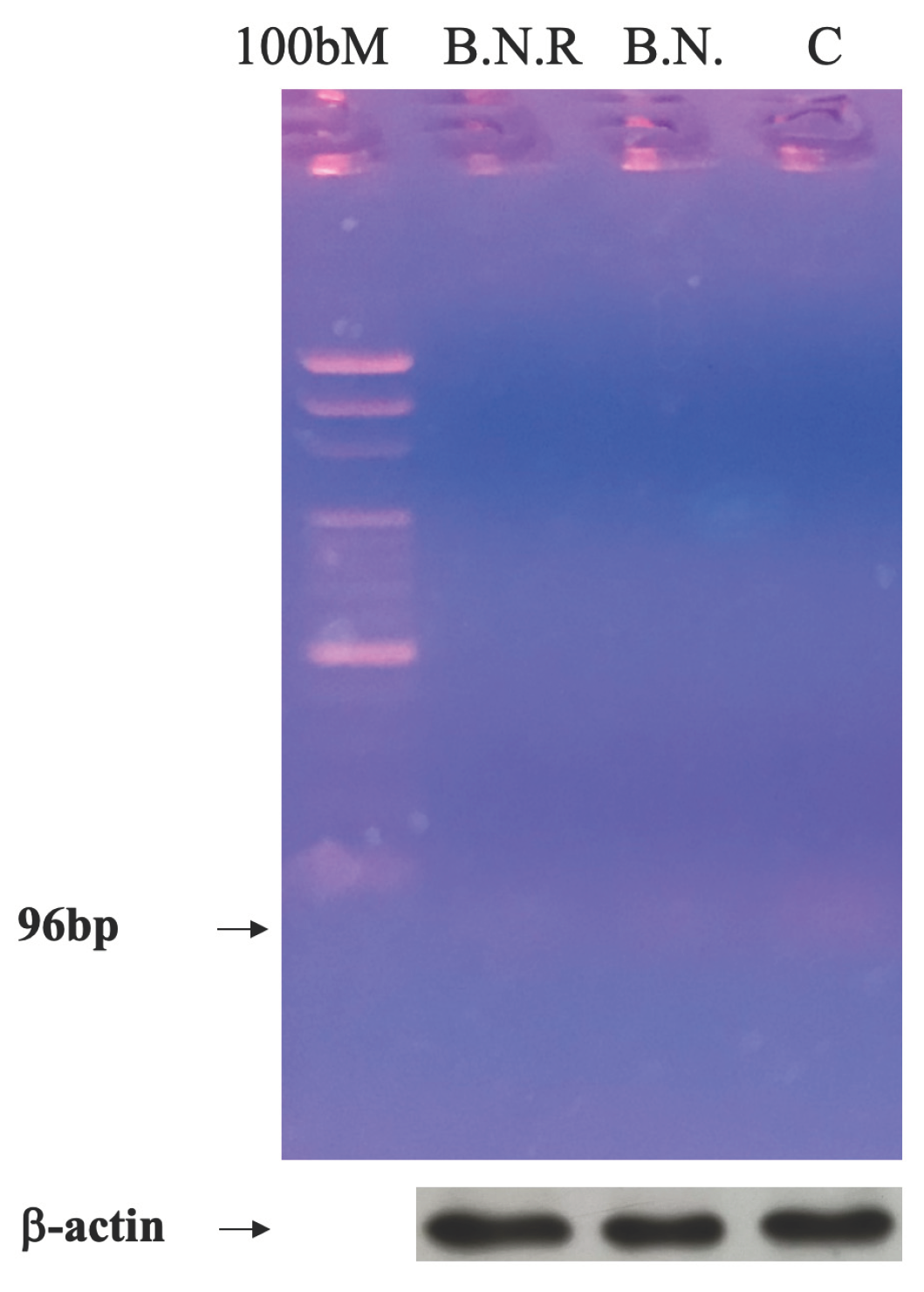

Figure 8.

Long-Term Suppression of Telomerase Activity by BNE-RRC Treatment. Cancer cells underwent a 14-day treatment with BNE-RRC in monolayer culture. Subsequently, the cells were cultured without BNE-RRC to investigate the enduring impact of the treatment on telomerase activity. The results indicate that BNE-RRC treatment significantly suppresses telomerase activity in cancer cells, and this suppression persists even after an extended period of culture without the presence of BNE-RRC. To ensure equal protein loading and to serve as a reaction control for the telomerase activity assay, Western blot analysis was conducted. β-actin was used as a loading control (lower panel). These experiments were performed four times; representative data are shown.

Figure 8.

Long-Term Suppression of Telomerase Activity by BNE-RRC Treatment. Cancer cells underwent a 14-day treatment with BNE-RRC in monolayer culture. Subsequently, the cells were cultured without BNE-RRC to investigate the enduring impact of the treatment on telomerase activity. The results indicate that BNE-RRC treatment significantly suppresses telomerase activity in cancer cells, and this suppression persists even after an extended period of culture without the presence of BNE-RRC. To ensure equal protein loading and to serve as a reaction control for the telomerase activity assay, Western blot analysis was conducted. β-actin was used as a loading control (lower panel). These experiments were performed four times; representative data are shown.

Figure 9.

HPLC Chromatographic Analysis of BNE-RRC Compounds. HPLC analysis to identify and separate key compounds present in Boehmeria Nivea Extract (BNE-RRC). The analysis separated p-coumaric acid (1), isoquercitrin (2), and caffeic acid (3), with retention times of 12.1, 17.4, and 19.1 minutes, respectively. These experiments were performed three times; representative data are shown.

Figure 9.

HPLC Chromatographic Analysis of BNE-RRC Compounds. HPLC analysis to identify and separate key compounds present in Boehmeria Nivea Extract (BNE-RRC). The analysis separated p-coumaric acid (1), isoquercitrin (2), and caffeic acid (3), with retention times of 12.1, 17.4, and 19.1 minutes, respectively. These experiments were performed three times; representative data are shown.