Introduction

With the increasing globalisation and interconnectedness of the world, the demand for instructors who can teach Japanese as a foreign language (JFL) has grown significantly. According to the Japan Foundation’s “Survey Report on Japanese Language Education Abroad”, the number of Japanese language learners worldwide has grown approximately thirty times in the past forty years, reaching 3.79 million in 2021 (The Japan Foundation, 2023, p. 7).

Nevertheless, from 2019 to 2021 the total of JFL teachers decreased by 2,731 people worldwide. The same tendency has been observed in the number of learners, which fell by 57,060 people; also, the number of institutions has fallen by 389. Classes are overcrowded, and the number of learners per teacher averaged 50.9 people worldwide in the 2021 fiscal year (The Japan Foundation, 2023).

Furthermore, in today’s diverse classrooms, teachers face the challenge of catering to the needs of students with different learning styles and cultural backgrounds (Frutas, 2023). In the contemporary learning environment, foreign language teachers must have the necessary skills and tools to teach JFL in multilingual classrooms effectively.

This article aims to investigate the characteristics of JFL teachers across various educational stages in order to gain an insight into the staffing patterns of JFL institutions, which can help determine the potential impact on the quality of education provided to students. The resulting comprehensive profile of JFL teachers was based on their background information: e.g. country of origin, age, level of formal education, study of teaching methods in tertiary education, teaching experience and form of employment (part-time or full-time).

The article also seeks to analyse the current state and trends of multilingual education and the distribution of JFL multilingual classrooms across various regions and different educational stages (the initial stage of formal education, tertiary education and non-school education).

In this study, we collected and analysed the data from the international survey “Teaching the Japanese language in multilingual classrooms – the English medium instruction approach” conducted by the authors as a questionnaire among non-native Japanese teachers. Quantitative analysis methods were primarily used to achieve the aim of the current paper.

Literature Review

The Japan Foundation has conducted surveys regarding institutions involved in Japanese language education since 1974. The survey report gives basic information about institutions providing JFL education, learners, motivations for learning Japanese, the status of Japanese language education and teachers. One recently added item to the survey is the data on full-time or part-time employment as a factor that impacts the quality of Japanese language education (The Japan Foundation, 2023).

It is important to analyse current staffing patterns at JFL institutions in order to understand their needs better. This can be a helpful reference for recruitment or for forecasting JFL institution needs. The concept of teacher staffing includes different elements depending on the context in which it is used. In the narrowest sense, staffing means providing employees or assistants (Kim, 2003). Ohta (2020) stated the importance of increasing the diversity of Japanese language teachers, promoting JFL teaching as a possible career path to student communities and guiding students in their career development.

This article examines the issues of JFL teacher supply and placement, focusing on geographical distribution, the form of employment (in connection with teachers’ age and educational stage), work experience and the highest degree attained.

Mori et al. (2020a, 2020b) highlight that as educators, JFL teachers are responsible for creating environments where diverse students can communicate beyond their differences and learn from each other.

A learning environment is a comprehensive and natural concept encompassing both the learning process and the environment in which it occurs. This creates an ecosystem surrounding the learning activity and its outcomes (Education GPS, 2023).

The teaching and learning environment has become more multicultural than forty years ago when classrooms contained significantly fewer international students (Winch, 2016). As stated in a European Commission report entitled “Language Teaching and Learning in Multilingual Classrooms,” multilingual classrooms are becoming more commonplace in many EU countries because of increasing mobility. Practitioners believe that teaching approaches must be adapted in multilingual classrooms; teachers must be aware of this and have strategies and resources to manage (European Commission, 2015).

The difficulty caused by linguistic diversity is often considered a problem for teachers. It is a common issue that teachers need to be adequately prepared to meet that challenge. Nevertheless, diversity can also be considered to be a valuable asset for education and for the long-term development of society and the economy (UNESCO & UNICEF, 2020).

Some studies have emphasised the importance of proper pre-service and in-service training programmes for JFL teachers (Moritoki, 2018). Galant (2018) mentions the lack of well-prepared JFL teachers: “Simply being a Japanese native speaker or having a degree in Japanese does not make someone a good teacher of the Japanese language” (p. 14). He is concerned that while language difficulties, learner diversity and teaching problems are all addressed in most studies on JFL teaching, none of them genuinely question the ability of teachers to teach (Galant, 2018). Others demand teachers’ assistance because they are unprepared to support students’ multilingual development. To implement multilingually-oriented pedagogies, teachers must be equipped with the relevant knowledge and appropriate tools (Christison, Krulatz, & Sevinç, 2021). No matter how good a teacher’s pre-service education is, it cannot fully prepare them for all the challenges they will face in their career (Schleicher, 2011).

Multilingual educational settings are new working conditions that teachers need to adapt to. A multilingual classroom is one that comprises students from various cultural and native-language backgrounds (regardless of their level of proficiency) where there is no common mother tongue for teachers and all students.

The study of multilingualism and third language acquisition has greatly expanded in recent years. Multilingualism is a phenomenon that has been around for a while; however, the increasing diversity in language classrooms poses challenges for teachers in the contemporary learning environment.

Bruen & Kelly (2017) have studied the position of university language students whose mother tongue is other than the medium of instruction. They concluded that there was a need to be cognisant of increasing linguistic and cultural diversity and its impact on the language classroom. Alba de la Fuente & Lacroix (2015) studied the topic of multilingual learners and foreign language acquisition; they proposed that teachers adopt different strategies to take advantage of multilingual learners’ metalinguistic awareness.

This article attempts to address some of the issues mentioned above, focusing on the staffing patterns of JFL institutions and the spread of multilingual classrooms as a new reality for teachers’ working conditions.

Methodology

This article is an introductory part of a more extensive study conducted worldwide among Japanese language teachers (natives and non-natives) in countries where the first language of most of the population is not English. To achieve the aim of the study, a survey in the form of a questionnaire was conducted. Cover letters (in English and Japanese) with links to Google Forms (separately for native and non-native speakers) and an anonymity acknowledgement were sent to all JFL institutions in 122 countries (The Japan Foundation, 2021). The sample was selected using the convenience sampling method. Participants were chosen based on their willingness to participate in the study and their availability during the data collection period.

The survey was piloted in August 2023 and proved to be effective in gathering the data. The full-scale survey was conducted from September 2023 to January 2024. As a result, 274 teachers from fifty-seven countries and regions comprised the current study sample.

The questionnaire consisted of twenty-six open-ended and close-ended questions, of which nine have been exclusively used for this article. However, other questions (e.g. the respondents’ age and the type of educational institution) were employed in order to discern further relationships. The article looks at data from the first two parts of the survey dealing with “education and teaching experience” and the “teaching environment”, which included the teachers’ background information such as their country of origin and teaching, their age and level of formal education, whether these instructors had studied foreign language teaching methods, their form of employment, their working experience as teachers, their mother tongue, their place of work and whether their class were multilingual. Although the questionnaire contained closed and short open-ended questions, some of the latter were asked to verify the correctness of the former. For instance, in order to check the multilingual status of the class, we asked about the native language of the respondents and what native language(s) the students used in class. The collected data were primarily analysed using the quantitative method. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the demographic data, teaching experience and ratio of full-time and part-time teachers.

Research Results

Table 1 provides an overview of the geographical regions where Japanese language teachers replied to the questionnaire. The list of the countries and designated regions was provided in accordance with the Japan Foundation database (The Japan Foundation, 2021). Southeast Asia (n=62), South Asia (n=59), Eastern Europe (n=43), Western Europe (n=39), and East Asia (n=32) were well represented and dominated in number. In South Asia, the country most widely represented was India (n=35). The Middle East and North Africa were represented very little. This can be partially explained by the small number of JFL institutions in these regions and the low response rate. The Middle East accounts for 0.4%, and North Africa accounts for 0.2% of all JFL institutions worldwide (The Japan Foundation, 2023). Out of twelve regions implementing Japanese language education, North America and Oceania were excluded from the study. In the frame of our more extensive analysis of instructional languages, we excluded countries where English was the language of the majority. We should also note that due to our research strategy, we received replies only from those teachers who volunteered to fill in the questionnaire.

The number of part-time teachers has increased worldwide (Beaton & Gilbert, 2013). The pros of having part-time teachers include lower labour costs for educational institutions and more flexible schedules for teachers. Academic institutions can take advantage of a broader and more varied range of skilled individuals. Additionally, part-time teachers can bring unique perspectives and experiences to the classroom. However, disadvantages of relying heavily on part-time teachers include a lack of institutional knowledge and consistency, reduced benefits and job security for teachers, and a potentially lower quality of instruction if teachers are not adequately trained or supported. Additionally, part-time teachers may not have the same level of commitment or investment in the educational institution community (students and teaching staff) as full-time teachers.

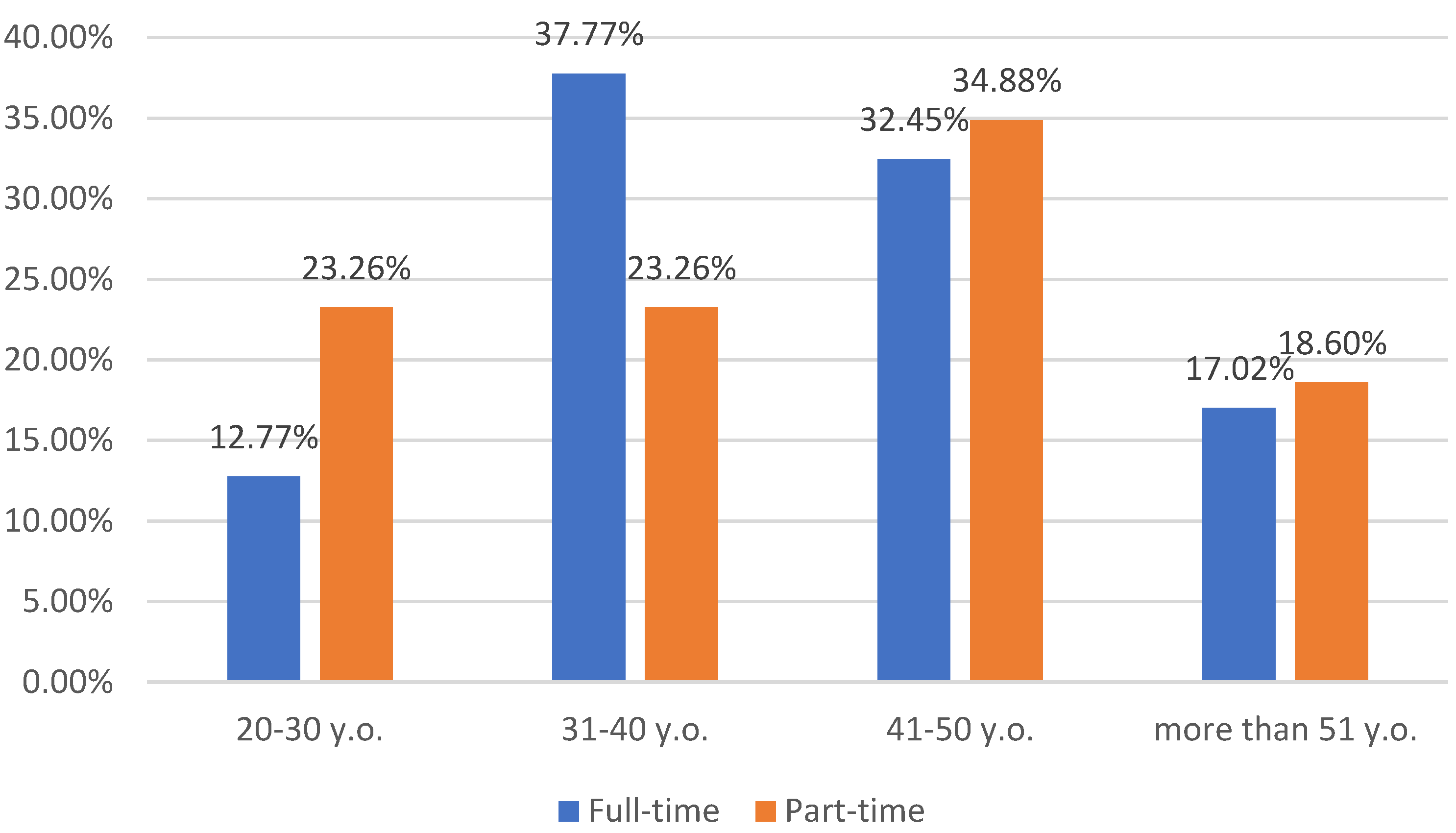

Figure 1 shows the proportion of full-time and part-time JFL teachers by age.

According to our results, 68.61% (n=188) of JFL teacher respondents were full-time and 31.39% (n=86) were part-time teachers. Having analysed the ratio by the age of these two groups separately, the results showed that most full-time teachers were 31–40 years old (37.77%, n=71), closely followed by the 41–50 age-range category (32.45%, n=61). Most part-time teachers were 41–50 years old (34.88%, n=30). The category of teachers who were 31–40 years old had the most significant disproportion in the ratio of full-time and part-time teachers, where the former prevailed over the latter by 14.51%. The category of respondents over 51 years old featured participants engaged on a full- or part-time basis approximately to the same degree.

The percentage distribution of full- and part-time teachers across educational stages was also important to our study because it provides insight into the current staffing patterns of Japanese language institutions and the potential impact on the quality of education offered. Understanding the proportion of full-time versus part-time teachers in different educational stages can help identify possible issues, such as overcrowded classes and a lack of resources, which may affect the quality of education. It can also help institutions plan and allocate resources to ensure there are enough qualified teachers to meet students’ needs.

To further investigate the distribution of JFL teachers across different institutions and educational stages, we identified the following groups: the initial stage of formal education (both primary and secondary schools), tertiary education (colleges, vocational schools and universities), and non-school education (e.g. private language schools, lifelong educational institutions and cultural clubs).

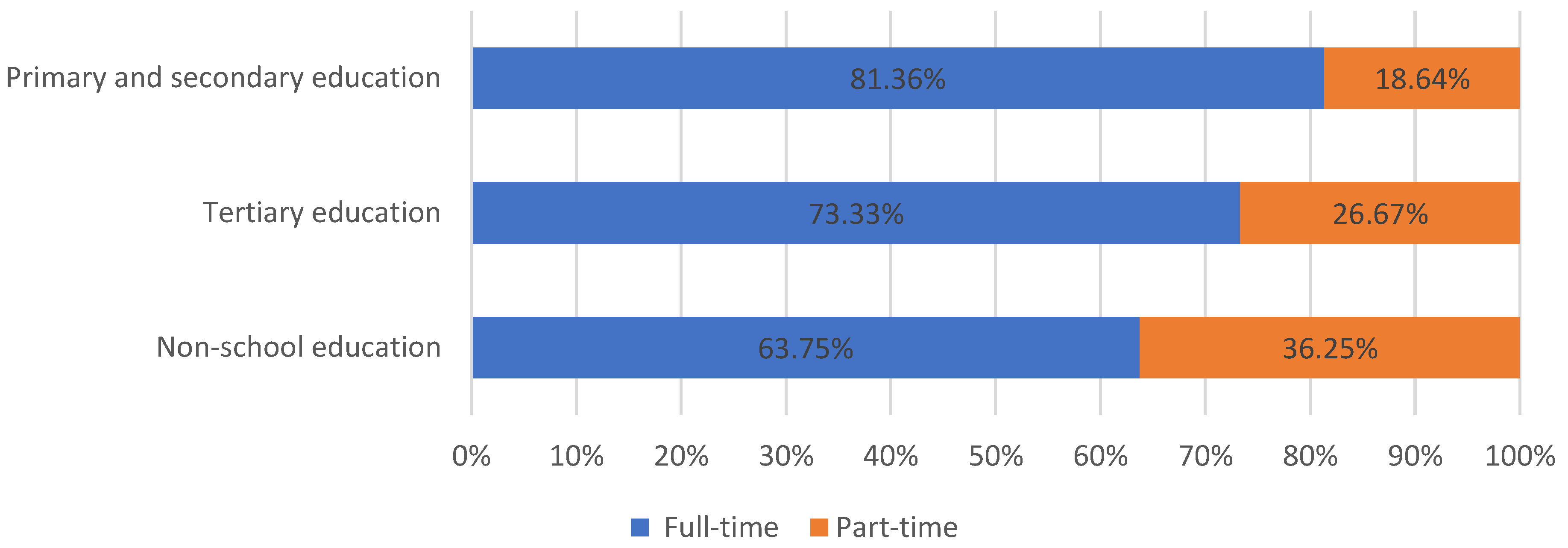

When asked about the institutions where instructors teach, the participants were free to present multiple answers. It was found that 16.42% (n=45) of teachers worked in several institutions (different educational stages). We looked at 229 unique answers to determine the ratio of full- and part-time teachers across different academic stages, as shown in

Figure 2.

On average, the most permanent contracts (81.36%, n=48) were given to JFL teachers working in the initial stage of formal education across fifty-seven countries. The second highest number of permanent contracts were issued to teachers in the tertiary education stage (73.33%, n=66). The lowest number of full-time teachers (63.75%, n=51) was in non-school education, with the highest number of part-time teachers constituting 36.25% (n=29). As a result, we can state that the full-time employment of JFL teachers prevailed through all the educational stages.

As the academic job market is changing, it is becoming increasingly frequent to come across job advertisements seeking candidates who can teach Japanese at all levels, ranging from beginner to advanced. Additionally, applicants are expected to teach culture courses about Japan. The ideal candidate should be able to contribute to the development of the programme, interact with the campus and community and pursue a progressive research agenda. Dowdle has commented on such high demands: “Such positions are beyond the training capacity of even the longest graduate program. Yet, these are the highly coveted positions sought after by an ever-growing number of freshly minted PhDs” (Dowdle, 2020, p. 384).

The percentage distribution of teachers by the highest degree attained across the educational stages is an essential aspect to consider when analysing the staffing patterns of JFL institutions. It provides insights into the qualifications and expertise of JFL teachers at different educational levels, affecting the quality of education provided to students.

Across all the educational stages, 44.53% of JFL instructors (n=122) held a master’s degree, followed by 38.32% with a bachelor’s degree (n=105) and 17.15% with a PhD (n=47). Expectedly, our results showed that tertiary education had the highest percentage of teachers with a doctorate degree (over three quarters) and the lowest percentage of teachers with a bachelor’s degree (less than one fifth) (

Table 2). Teachers with master’s degrees worked twice more at the tertiary educational stage than at the initial stage of formal education. There was no measurable difference in the percentages of primary/secondary teachers and those working in non-school education with bachelor’s degrees as their highest degree attained (39.56% and 42.86%, respectively).

A significant percentage of JFL teachers with a bachelor’s degree at the initial stage of formal education may indicate a need for more expertise in teaching methods specific to this stage. On the other hand, a high percentage of JFL teachers with doctoral degrees at the tertiary education level indicated a higher level of expertise in teaching advanced Japanese language skills to students.

When asked whether they studied “foreign languages teaching methods” or “linguodidactics” in a tertiary education establishment, 61.31% (n=168) of the respondents answered positively.

The influence of a teacher’s experience on students’ outcomes is a topic of intense discussion and research in education (Moritoki, 2018; Galant, 2018). While many factors – such as curriculum, resources, and student engagement – can impact student success, a teacher’s experience and expertise can significantly affect the quality of instruction and the overall learning environment. It is widely believed that more experienced teachers can better manage classrooms, design effective lessons and provide individualised student support.

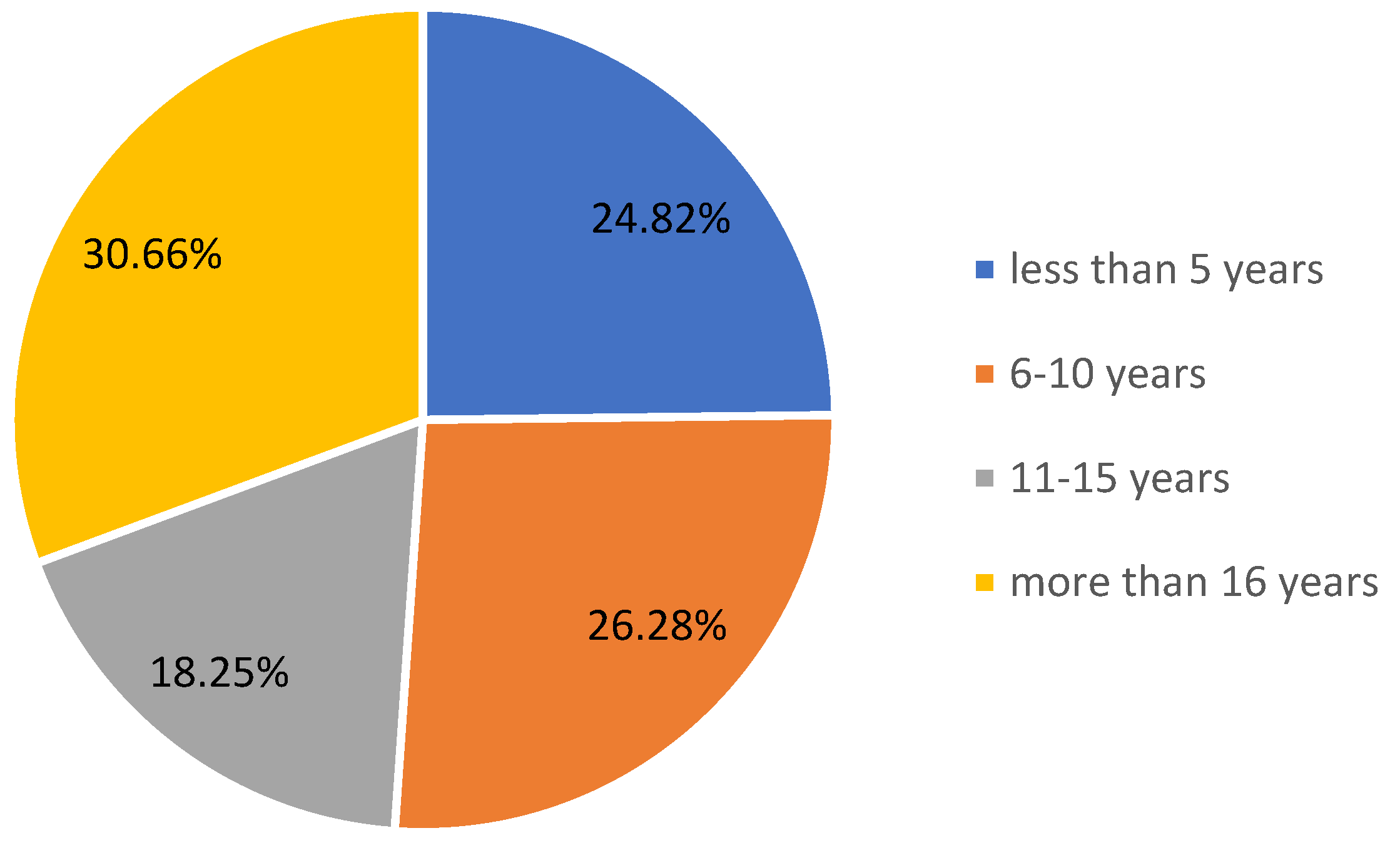

As for the experience in teaching among JFL teachers, we cannot state that there was a category that prevailed. The ratio of early career teachers (1–10 years) was almost equal to mid- and late-career teachers. The proportion of those relatively new to the profession was 51.09% (n=140). Experienced instructors working for over eleven years constituted 48.91% (n=134) of the teacher workforce; however, the ratio of mid-career teachers with 11–15 years of experience was the lowest (18.25%, n=50).

Figure 3.

The percentage distribution of teachers by teaching work experience (n=274).

Figure 3.

The percentage distribution of teachers by teaching work experience (n=274).

In recent years, diversity and inclusion have become a major focus of academic and professional institutions (Mori, 2020a). The proportion of multilingual JFL classrooms across different educational stages is important because it reflects the current trend of language learning and teaching in diverse educational contexts. Understanding the distribution of multilingual classrooms in various educational stages can help educators and policymakers develop appropriate teaching strategies and curricula to cater to the needs of multilingual learners.

Having analysed the responses to the questions about the country of origin and teaching, we can claim that teaching in a foreign country was a rare practice for JFL non-native speakers. Out of the total respondents (n=274), only six instructors moved abroad and taught Japanese there. This accounts for just 2.19% of all respondents.

The participants were asked if they taught in a classroom where multiple native languages were spoken. The results of our study showed that 40.51% of all the 274 teachers taught in multilingual classrooms.

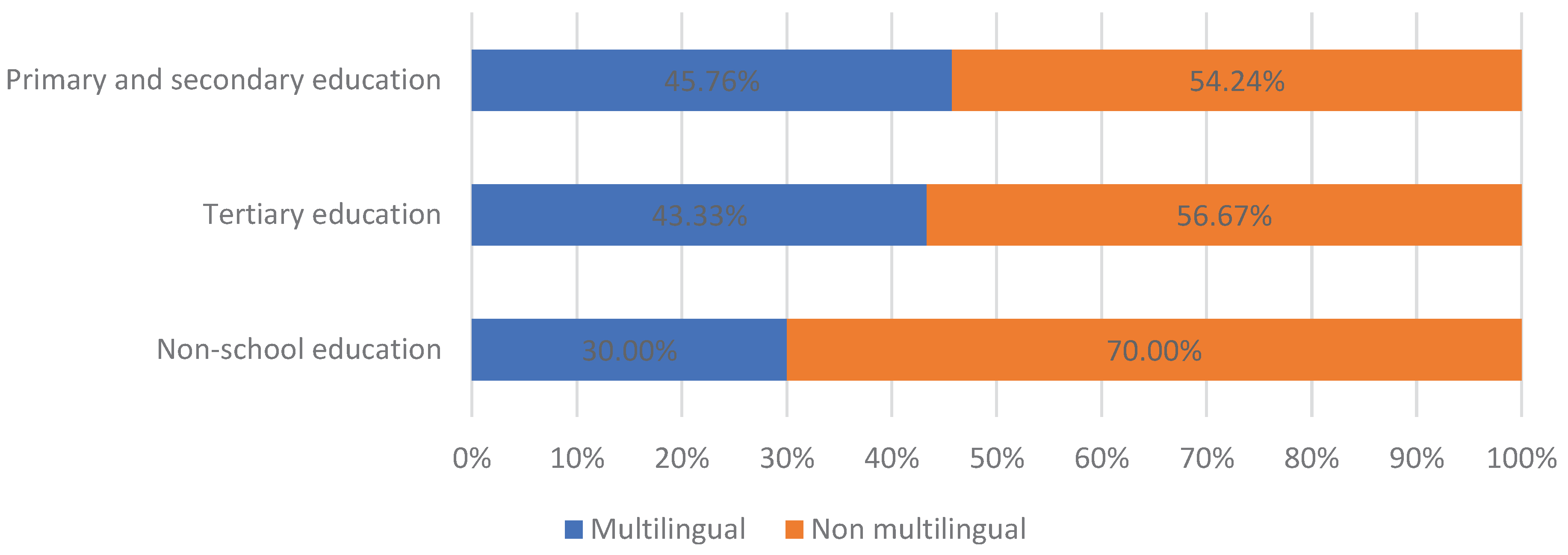

Figure 4 shows the proportion of multilingual JFL classrooms across educational stages, considering the teachers’ responses from those who indicated that they taught at one institution only (n=229). The ratio of multilingual classrooms was similar in the initial stage of formal education (45.76%, n=27) and tertiary education (43.33%, n=39). The number of multilingual classrooms in non-school education was the lowest (30.00%, n=24).

The geographic distribution of multilingual and non-multilingual JFL classrooms across regions is an important area to discuss. With the increasing mobility of people around the world, multilingual classrooms are becoming more common. Teaching foreign languages using the mother tongue becomes problematic in such a learning environment. This is especially the case with JFL due to its high contextuality; therefore, it is crucial to understand the current state and trends of multilingual education in JFL classrooms worldwide.

Table 3 shows the distribution of multilingual and non-multilingual JFL classrooms across different regions. Central and South America, along with East Asia, had the lowest number of multilingual classes and consequently the most significant number of students from the same cultural background. Most classrooms in South Asia were multilingual (59.32%). JFL classrooms in Southeast Asia, Western Europe and Eastern Europe had approximately the same ratio: 41.94%, 41.03% and 41.86% respectively. We could not draw a logical conclusion on Africa and the Middle East as they have few JFL institutions (The Japan Foundation, 2023), and the response rate from teachers in those regions was relatively low (n=11).

The spread of multilingual classrooms poses new demands on teachers. They must understand how to use bilingual and multilingual pedagogies across the curriculum to go beyond teaching language exclusively. They need to know how to make use of students’ language skills (UNESCO & UNICEF, 2020).

Discussion

This article aimed to gather data from the “Teaching the Japanese Language in Multilingual Classrooms – the English-medium Instruction Approach” survey, which was used to analyse the profile of Japanese language instructors and the spread of multilingual classrooms across different regions and educational stages. While conducting the study we encountered difficulties gathering data from some countries. This was the case with China, which was the top-ranked country regarding the number of JFL institutions (16.2%). When we sent our questionnaire to all the institutions there, we were notified of their inability to respond to the Google Forms via the link because of access restrictions. Although we compiled a separate questionnaire for China (Jotform) and tried to reach the Japanese teachers there again, very few of them replied; however, we received a significant number of responses from Mongolia and Taiwan, and consequently the East Asian region was well represented.

The pilot survey results showed that the teachers shared a different understanding of the meaning of multilingual classrooms. In the central survey, a short explanation of the notion was added and the relevant question was framed as follows: “Is your class multilingual? (there is no one common mother tongue for the teacher and all the students)”. Furthermore, to avoid a possible misunderstanding, there was an open-ended question if the respondent answered negatively: “What native language/languages are spoken in your class?” This helped us to find six answers where the class was multilingual even though the teacher had not stated it. In one German classroom, a teacher stated German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and other languages as students’ native languages. In France, Turkish and Chinese were stated as native languages besides French. Such classes were deemed to be multilingual; however, seven teachers stated that English was one of the two mother tongues spoken in class (in Bangladesh, France, Nepal, Norway, Portugal, and Venezuela). Due to the high possibility of misunderstanding the question, we did not consider these classrooms multilingual, and the original negative responses were not changed.

Our study has limitations as the sample may not precisely represent the JFL teachers’ population. This is why the generalised results in this article may only be further used to a certain extent.

Conclusions

This article presented the results of a survey conducted among Japanese language instructors from fifty-seven countries to determine their background information, such as age, level of education, teaching experience and form of employment. The survey’s primary results showed the proportion of multilingual classrooms among countries in different regions and educational stages as well as the distribution of Japanese language instructors.

The received data can be used to identify areas where further training and professional development may be required for JFL teachers. Overall, the percentage distribution of teachers by the highest degree attained across the educational stages is a crucial factor in understanding the staffing patterns of JFL institutions and ensuring the quality of education provided to students.

JFL classrooms pose a challenge to teachers because they tend to be overcrowded, and classrooms with JFL students from different cultural backgrounds have become the norm rather than the exception. It is essential to recognise that having a linguistically diverse classroom is a common issue that needs to be addressed. This study shed some light on the increasing presence of JFL multilingual classrooms. It was found that over 40% of all JFL classrooms were multilingual. Investigating the proportion of multilingual JFL classrooms across educational stages is crucial for improving the effectiveness and quality of JFL education in multilingual contexts.

JFL educational institutions require teachers who can respond to the challenges of a linguistically diverse learning environment. Newly qualified teachers might need to gain experience teaching Japanese in multilingual classrooms. Initial teacher training and in-service training should include intercultural skills, experience in multilingual classrooms and teaching students from varied backgrounds.

One implication for further research can be to discover what the best practice in multilingual classrooms might be. English as a medium of instruction has become a part of multilingual reality for both teachers and students (Linn & Radjabzade, 2020). The question arises whether Japanese should be taught solely in the target language, whether English should be used as a medium, or if a combination of Japanese, the native language and English is better.

Acknowledgements

The first author acknowledges the funding from the EU NextGenerationEU through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under project No. 09I03-03-V01-00071. We also acknowledge the support of the Japan Foundation’s Japanese Language Institutes in Urawa and Kansai. We wholeheartedly thank all the respondents for their willingness to participate in this international study.

References

- Alba de la Fuente, A., & Lacroix, H. (2015). Multilingual learners and foreign language acquisition: Insights into the effects of prior linguistic knowledge. Language Learning in Higher Education, 5(1), 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Beaton, F., & Gilbert, A. (2013). Developing Effective Part-time Teachers in Higher Education. Routledge.

- Bruen, J., & Kelly, N. (2017). Mother-tongue diversity in the foreign language classroom: Perspectives on the experiences of non-native speakers of English studying foreign languages in an English-medium university. Language Learning in Higher Education, 7(2), 353–369. [CrossRef]

- Christison, M., Krulatz, A., & Sevinç, Y. (2021). Supporting teachers of multilingual young learners: Multilingual approach to diversity in education (MADE). In: J. Rokita-Jaśkow, A. Wolanin (Ed.) Facing Diversity in Child Foreign Language Education. Second Language Learning and Teaching (271–289). Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Dowdle, B. C. (2020). The generalist’s dilemma: How accidental language teachers are at the center of Japanese pedagogy. Japanese Language and Literature, 54(2), 383–389. [CrossRef]

- Education GPS. (2023). Review education policies. OECD. Retrieved from: https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=41710&filter=all.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. (2015). Language Teaching and Learning in Multilingual Classrooms. Publications Office. Retrieved from: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/766802.

- Frutas, M. L. (2023). Breaking the mold: How pre-service teachers’ learning styles are revolutionizing teaching and learning. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 14(3). 667-678. Retrieved from: https://core.ac.uk/outputs/574722126. [CrossRef]

- Galan, C. (2018). Students, teachers, language, educational methods and new media: Where should we anchor Japanese language teaching? Some reflections from the field. Japanese Language Education in Europe, 22, 13–28. Retrieved from: https://eaje.eu/pdfdownload/pdfdownload.php?index=28-43&filename=kicho-galan.pdf&p=lisbon.

- Kim, Y. H. (2003). Staffing in school education. In: J.P. Keeves & R. Watanabe (Ed.) International Handbook of Educational Research in the Asia-Pacific Region. Springer International Handbooks of Education (959–971). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [CrossRef]

- Linn, A., & Radjabzade, S. (2020). English-Medium Instruction in Higher Education in the Countries of the South Caucasus. London: British Council.

- Mori, J., & Hasegawa, A. (2020a). Diversity, inclusion and professionalism in Japanese language education: introduction to the special section. Japanese Language and Literature, 54(2), 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Mori, J., Hasegawa, A., Park, J., & Suzuki, K. (2020b). On goals of language education and teacher diversity: beliefs and experiences of Japanese-language educators in North America. Japanese Language and Literature, 54(2), 267–304. [CrossRef]

- Moritoki, N. (2018). Learner motivation and teaching aims of Japanese language instruction in Slovenia, Acta Linguistica Asiatica, 8(1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Ohta, A. S. (2020). Increasing diversity of Japanese language teachers: approaches to teaching-related professional development for college students in North America. Japanese Language and Literature, 54(2), 399–414. [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A. (2011). Building a High-Quality Teaching Profession: Lessons from around the World. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264113046-en.

- The Japan Foundation. (2021). Survey 2021: Search Engine for Institutions Offering Japanese-Language Education. Retrieved from: https://www.japanese.jpf.go.jp/do/index.

- The Japan Foundation. (2023). Survey Report on Japanese-Language Education Abroad 2021. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation. Retrieved from: https://www.jpf.go.jp/e/project/japanese/survey/result/dl/survey2021/All_contents_r2.pdf.

- UNESCO, & UNICEF. (2020). Approaches to Language in Education for Migrants and Refugees in The Asia-Pacific Region. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373660.

- Winch, J. (2016). A case study of Japanese language teaching in a multicultural learning environment. IAFOR Journal of Language Learning, 2(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).