Submitted:

26 June 2024

Posted:

27 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

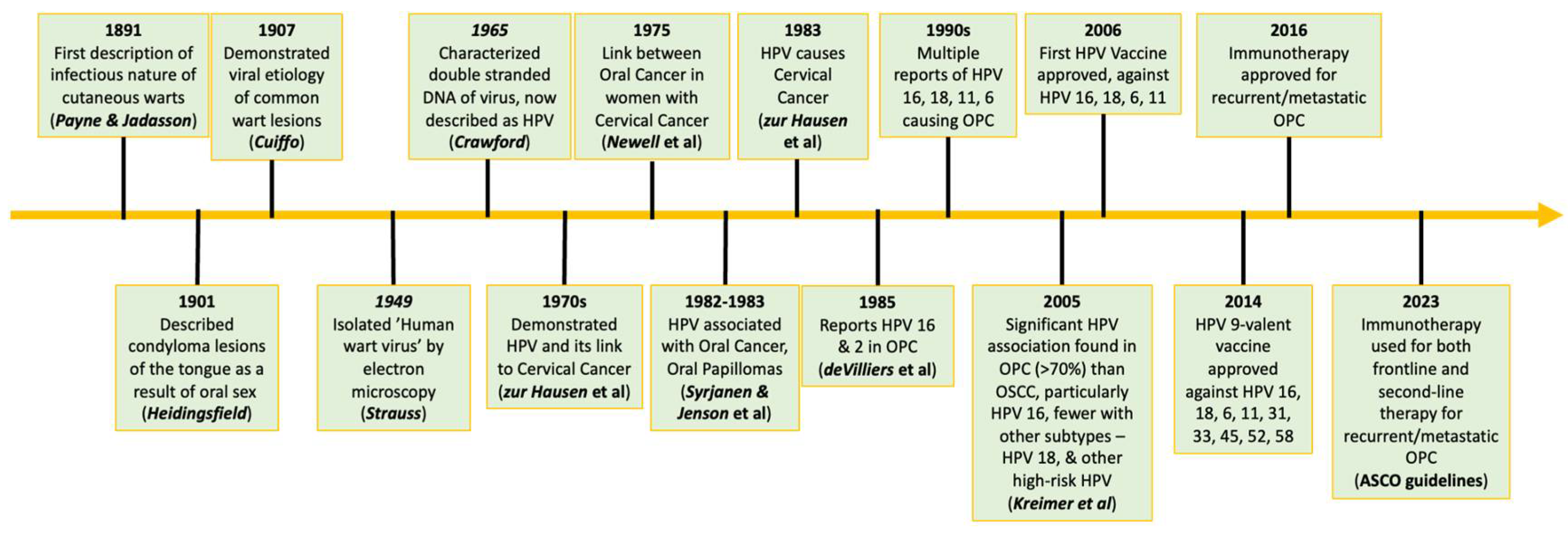

1. Background

1.1. Transmission of HPV

1.2. Epidemiology

2. HPV Structure

2.1. Host Cell Entry & Infection

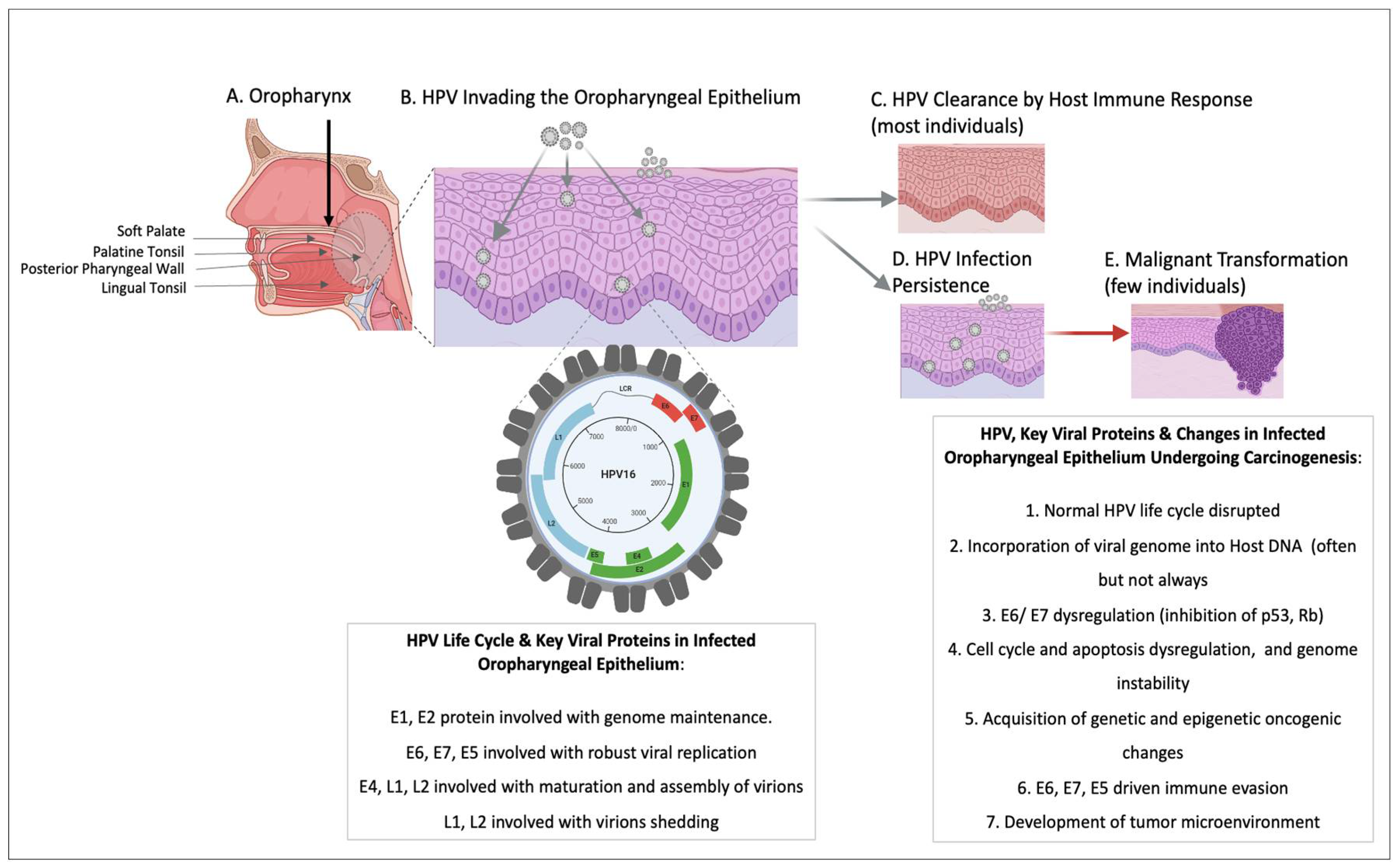

2.2. HPV & The Oropharynx

3. HPV & Molecular Features of Oncogenesis

4. HPV & Host Immune Response

5. Clinical Management

5.1. Standard Management of HPV

5.2. Management of OPC

6. Prevention

7. Diagnosis

7.1. Screening

8. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- HPV and Cancer - NCI Available online:. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Kreisel, K.M.; Spicknall, I.H.; Gargano, J.W.; Lewis, F.M.T.; Lewis, R.M.; Markowitz, L.E.; Roberts, H.; Johnson, A.S.; Song, R.; St. Cyr, S.B.; et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Among US Women and Men: Prevalence and Incidence Estimates, 2018. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bzhalava, D.; Eklund, C.; Dillner, J. International Standardization and Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types. Virology 2015, 476, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psyrri, A.; DiMaio, D. Human Papillomavirus in Cervical and Head-and-Neck Cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2008, 5, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global Burden of Cancer Attributable to Infections in 2018: A Worldwide Incidence Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrjänen, S.; Syrjänen, K. The History of Papillomavirus Research. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2008, 16 Suppl, S7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, M.J.; Shaw, E.W.; Bunting, H.; Melnick, J.L. “Crystalline” Virus-Like Particles from Skin Papillomas Characterized by Intranuclear Inclusion Bodies. Exp. Biol. Med. 1949, 72, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, L.V. A Study of Human Papilloma Virus DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1965, 13, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug, A.; Finch, J.T. Structure of Viruses of the Papilloma-Polyoma Type. J. Mol. Biol. 1965, 11, 403–IN44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dürst, M.; Gissmann, L.; Ikenberg, H.; Zur Hausen, H. A Papillomavirus DNA from a Cervical Carcinoma and Its Prevalence in Cancer Biopsy Samples from Different Geographic Regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1983, 80, 3812–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshart, M.; Gissmann, L.; Ikenberg, H.; Kleinheinz, A.; Scheurlen, W.; Zur Hausen, H. A New Type of Papillomavirus DNA, Its Presence in Genital Cancer Biopsies and in Cell Lines Derived from Cervical Cancer. EMBO J. 1984, 3, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, G.; Favre, M.; Croissant, O. Characterization of a New Type of Human Papillomavirus That Causes Skin Warts. J. Virol. 1977, 24, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gissmann, L.; Diehl, V.; Schultz-Coulon, H.J.; Zur Hausen, H. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of Human Papilloma Virus DNA Derived from a Laryngeal Papilloma. J. Virol. 1982, 44, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachow, K.R.; Ostrow, R.S.; Bender, M.; Watts, S.; Okagaki, T.; Pass, F.; Faras, A.J. Detection of Human Papillomavirus DNA in Anogenital Neoplasias. Nature 1982, 300, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjänen, K.J.; Pyrhönen, S.; Syrjänen, S.M.; Lamberg, M.A. Immunohistochemical Demonstration of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Antigens in Oral Squamous Cell Lesions. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1983, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löning, T.; Ikenberg, H.; Becker, J.; Gissmann, L.; Hoepfer, I.; Zur Hausen, H. Analysis of Oral Papillomas, Leukoplakias, and Invasive Carcinomas for Human Papillomavirus Type Related DNA. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1985, 84, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, E. -M.; Weidauer, H.; Otto, H.; Zur Hausen, H. Papillomavirus DNA in Human Tongue Carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 1985, 36, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurlen, W.; Stremlau, A.; Gissmann, L.; Höhn, D.; Zenner, H.; Hausen, H.Z. Rearranged HPV 16 Molecules in an Anal and in a Laryngeal Carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 1986, 38, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenberg, H.; Gissmann, L.; Gross, G.; Grussendorf-Conen, E.; Hausen, H.Z. Human Papillomavirus Type-16-related DNA in Genital Bowen’s Disease and in Bowenoid Papulosis. Int. J. Cancer 1983, 32, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Fenger, C.; van den Brule, A.J.; Sørensen, P.; Meijer, C.J.; Walboomers, J.M.; Adami, H.O.; Melbye, M.; Glimelius, B. Variants of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anal Canal and Perianal Skin and Their Relation to Human Papillomaviruses. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rubin, M.A.; Kleter, B.; Zhou, M.; Ayala, G.; Cubilla, A.L.; Quint, W.G.V.; Pirog, E.C. Detection and Typing of Human Papillomavirus DNA in Penile Carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 159, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, B.S.; Jensen, H.L.; Van Den Brule, A.J.C.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Frisch, M. Risk Factors for Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva and Vagina—Population-based Case–Control Study in Denmark. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 2827–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonawane, K.; Suk, R.; Chiao, E.Y.; Chhatwal, J.; Qiu, P.; Wilkin, T.; Nyitray, A.G.; Sikora, A.G.; Deshmukh, A.A. Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection: Differences in Prevalence Between Sexes and Concordance With Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection, NHANES 2011 to 2014. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petca, A.; Borislavschi, A.; Zvanca, M.; Petca, R.-C.; Sandru, F.; Dumitrascu, M. Non-Sexual HPV Transmission and Role of Vaccination for a Better Future (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among Gay and Bisexual Men | CDC Available online:. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/msmhealth/STD.htm (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Dahlstrom, K.R.; Burchell, A.N.; Ramanakumar, A.V.; Rodrigues, A.; Tellier, P.-P.; Hanley, J.; Coutlée, F.; Franco, E.L. Sexual Transmission of Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection among Men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2014, 23, 2959–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicka, M.; San Giorgi, M.R.M.; Dikkers, F.G. Transmission and Clearance of Human Papillomavirus Infection in the Oral Cavity and Its Role in Oropharyngeal Carcinoma – A Review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemminki, K.; Dong, C.; Frisch, M. Tonsillar and Other Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancers among Cervical Cancer Patients and Their Husbands: Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2000, 9, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Termine, N.; Giovannelli, L.; Matranga, D.; Caleca, M.P.; Bellavia, C.; Perino, A.; Campisi, G. Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women with Cervical HPV Infection: New Data from an Italian Cohort and a Metanalysis of the Literature. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.; Milici, J.; Alam, S.; Ferster, A.P.O.; Goldenberg, D.; Meyers, C.; Goyal, N. Assessing Nonsexual Transmission of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV): Do Our Current Cleaning Methods Work? J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 3956–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casalegno, J.; Le Bail Carval, K.; Eibach, D.; Valdeyron, M.-L.; Lamblin, G.; Jacquemoud, H.; Mellier, G.; Lina, B.; Gaucherand, P.; Mathevet, P.; et al. High Risk HPV Contamination of Endocavity Vaginal Ultrasound Probes: An Underestimated Route of Nosocomial Infection? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhry, C.; Gillison, M.L.; D’Souza, G. Tobacco Use and Oral HPV-16 Infection. JAMA 2014, 312, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G.R.; Krementz, E.T.; Roberts, J.D. Excess Occurrence of Cancer of the Oral Cavity, Lung, and Bladder Following Cancer of the Cervix. Cancer 1975, 36, 2155–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenson, A.B.; Lancaster, W.D.; Hartmann, D.P.; Shaffer, E.L. Frequency and Distribution of Papillomavirus Structural Antigens in Verrucae, Multiple Papillomas, and Condylomata of the Oral Cavity. Am. J. Pathol. 1982, 107, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Syrjänen, S.; Rautava, J.; Syrjänen, K. HPV in Head and Neck Cancer—30 Years of History. In HPV Infection in Head and Neck Cancer; Golusiński, W., Leemans, C.R., Dietz, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 3–25. ISBN 978-3-319-43580-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kreimer, A.R.; Clifford, G.M.; Boyle, P.; Franceschi, S. Human Papillomavirus Types in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas Worldwide: A Systematic Review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, G.; Kreimer, A.R.; Viscidi, R.; Pawlita, M.; Fakhry, C.; Koch, W.M.; Westra, W.H.; Gillison, M.L. Case–Control Study of Human Papillomavirus and Oropharyngeal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schache, A.G.; Powell, N.G.; Cuschieri, K.S.; Robinson, M.; Leary, S.; Mehanna, H.; Rapozo, D.; Long, A.; Cubie, H.; Junor, E.; et al. HPV-Related Oropharynx Cancer in the United Kingdom: An Evolution in the Understanding of Disease Etiology. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 6598–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leemans, C.R.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Brakenhoff, R.H. The Molecular Landscape of Head and Neck Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G�tz, C.; Bischof, C.; Wolff, K.-D.; Kolk, A. Detection of HPV Infection in Head and Neck Cancers: Promise and Pitfalls in the Last Ten Years: A Meta-Analysis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, M.E.; Chiocca, S. Human Papillomavirus as a Driver of Head and Neck Cancers. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, F.; Rettig, E.M.; Tsai, H.; El Asmar, M.; Fung, N.; Eisele, D.W.; Fakhry, C. The Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Oropharyngeal Cancer Is Increasing Regardless of Sex or Race, and the Influence of Sex and Race on Survival Is Modified by Human Papillomavirus Tumor Status. Cancer 2019, 125, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, M.; Grønhøj, C.; Jensen, D.H.; Carlander, A.F.; Agander, T.; Kiss, K.; Olsen, C.; Baandrup, L.; Nielsen, F.C.; Andersen, E.; et al. The Current Epidemic of HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: An 18-Year Danish Population-Based Study with 2,169 Patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 134, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mistro, A.; Frayle, H.; Menegaldo, A.; Favaretto, N.; Gori, S.; Nicolai, P.; Spinato, G.; Romeo, S.; Tirelli, G.; Da Mosto, M.C.; et al. Age-Independent Increasing Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus-Driven Oropharyngeal Carcinomas in North-East Italy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittekindt, C.; Wagner, S.; Bushnak, A.; Prigge, E.-S.; Von Knebel Doeberitz, M.; Würdemann, N.; Bernhardt, K.; Pons-Kühnemann, J.; Maulbecker-Armstrong, C.; Klussmann, J.P. Increasing Incidence Rates of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Germany and Significance of Disease Burden Attributed to Human Papillomavirus. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila. Pa.) 2019, 12, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeggblom, L.; Attoff, T.; Yu, J.; Holzhauser, S.; Vlastos, A.; Mirzae, L.; Ährlund-Richter, A.; Munck-Wikland, E.; Marklund, L.; Hammarstedt-Nordenvall, L.; et al. Changes in Incidence and Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Tonsillar and Base of Tongue Cancer during 2000-2016 in the Stockholm Region and Sweden. Head Neck 2019, 41, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.; Jones, O.S.; Breeze, C.E.; Gilson, R. Gender-Neutral HPV Vaccination in the UK, Rising Male Oropharyngeal Cancer Rates, and Lack of HPV Awareness. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathish, N.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y. Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Associated Oral Cancers and Treatment Strategies. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 29S–36S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Rowley, J.; Alemany, L.; Arbyn, M.; Giuliano, A.R.; Markowitz, L.E.; Broutet, N.; Taylor, M. Global and Regional Estimates of Genital Human Papillomavirus Prevalence among Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1345–e1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillison, M.L.; D’Souza, G.; Westra, W.; Sugar, E.; Xiao, W.; Begum, S.; Viscidi, R. Distinct Risk Factor Profiles for Human Papillomavirus Type 16–Positive and Human Papillomavirus Type 16–Negative Head and Neck Cancers. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, G.; Wentz, A.; Kluz, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sugar, E.; Youngfellow, R.M.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, W.; Gillison, M.L. Sex Differences in Risk Factors and Natural History of Oral Human Papillomavirus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 1893–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Massa, S.; Mazul, A.L.; Kallogjeri, D.; Yaeger, L.; Jackson, R.S.; Zevallos, J.; Pipkorn, P. The Association of Smoking and Outcomes in HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Epidemiology, Molecular Biology and Clinical Management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Amin, N.; Herberg, M.E.; Maroun, C.A.; Wang, H.; Guller, M.; Gourin, C.G.; Rooper, L.M.; Vosler, P.S.; Tan, M.; et al. Association of Tumor Site With the Prognosis and Immunogenomic Landscape of Human Papillomavirus–Related Head and Neck and Cervical Cancers. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2022, 148, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Mann, D.; Sinha, U.K.; Kokot, N.C. The Molecular Mechanisms of Increased Radiosensitivity of HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OPSCC): An Extensive Review. J. Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 2018, 47, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hong, A.M. The Human Papillomavirus Confers Radiosensitivity in Oropharyngeal Cancer Cells by Enhancing DNA Double Strand Break. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, P.Y.F.; Cecchini, M.J.; Barrett, J.W.; Shammas-Toma, M.; De Cecco, L.; Serafini, M.S.; Cavalieri, S.; Licitra, L.; Hoebers, F.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; et al. Immune-Based Classification of HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer with Implications for Biomarker-Driven Treatment de-Intensification. eBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, A.A. Human Papillomaviruses: Diversity, Infection and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonsson, A.; Karanfilovska, S.; Lindqvist, P.G.; Hansson, B.G. General Acquisition of Human Papillomavirus Infections of Skin Occurs in Early Infancy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mergner, T.; Pompeiano, O. Single Unit Firing Patterns in the Vestibular Nuclei Related to Saccadic Eye Movement in the Decerebrate Cat. Arch. Ital. Biol. 1978, 116, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luria, L.; Cardoza-Favarato, G. Human Papillomavirus. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Villiers, E.-M.; Fauquet, C.; Broker, T.R.; Bernard, H.-U.; Zur Hausen, H. Classification of Papillomaviruses. Virology 2004, 324, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PaVE Available online:. Available online: https://pave.niaid.nih.gov/#home (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Pereira, R.; Hitzeroth, I.I.; Rybicki, E.P. Insights into the Role and Function of L2, the Minor Capsid Protein of Papillomaviruses. Arch. Virol. 2009, 154, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.B.; Cheng, N.; Thompson, C.D.; Lowy, D.R.; Steven, A.C.; Schiller, J.T.; Trus, B.L. Arrangement of L2 within the Papillomavirus Capsid. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5190–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.; Calleja-Macias, I.E.; Dunn, S.T. Genome Variation of Human Papillomavirus Types: Phylogenetic and Medical Implications. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, H.-U.; Chan, S.-Y.; Manos, M.M.; Ong, C.-K.; Villa, L.L.; Delius, H.; Peyton, C.L.; Bauer, H.M.; Wheeler, C.M. Identification and Assessment Of Known And Novel Human Papillomaviruses by Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification, Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms, Nucleotide Sequence, and Phylogenetic Algorithms. J. Infect. Dis. 1994, 170, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorbar, J. The Papillomavirus Life Cycle. J. Clin. Virol. 2005, 32, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehrmann, F.; Laimins, L.A. Human Papillomaviruses: Targeting Differentiating Epithelial Cells for Malignant Transformation. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5201–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorbar, J. Molecular Biology of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cancer. Clin. Sci. 2006, 110, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combes, J.-D.; Dalstein, V.; Gheit, T.; Clifford, G.M.; Tommasino, M.; Clavel, C.; Lacau St Guily, J.; Franceschi, S. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Tonsil Brushings and Gargles in Cancer-Free Patients: The SPLIT Study. Oral Oncol. 2017, 66, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreimer, A.R.; Bhatia, R.K.; Messeguer, A.L.; González, P.; Herrero, R.; Giuliano, A.R. Oral Human Papillomavirus in Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2010, 37, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellsagué, X.; Alemany, L.; Quer, M.; Halec, G.; Quirós, B.; Tous, S.; Clavero, O.; Alòs, L.; Biegner, T.; Szafarowski, T.; et al. HPV Involvement in Head and Neck Cancers: Comprehensive Assessment of Biomarkers in 3680 Patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djv403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietbergen, M.M.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; Bloemena, E.; Witte, B.I.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Heideman, D.A.M.; Boon, D.; Koljenovic, S.; Baatenburg-de Jong, R.J.; Leemans, C.R. Human Papillomavirus Detection and Comorbidity: Critical Issues in Selection of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer for Treatment De-Escalation Trials. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2740–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, R.D.M.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Heideman, D.A.M.; Meijer, C.J.L.M. Clinical Implications of (Epi)Genetic Changes in HPV-Induced Cervical Precancerous Lesions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfs, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Laury, A.; Wang, X.; Nucci, M.R.; McLaughlin-Drubin, M.E.; Münger, K.; Feldman, S.; McKeon, F.D.; Xian, W.; et al. A Discrete Population of Squamocolumnar Junction Cells Implicated in the Pathogenesis of Cervical Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 10516–10521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, R.S.R.; Keegan, H.; White, C.; Tewari, P.; Toner, M.; Kennedy, S.; O’Regan, E.M.; Martin, C.M.; Timon, C.V.I.; O’Leary, J.J. Cytokeratin 7 in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Junctional Biomarker for Human Papillomavirus–Related Tumors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2017, 26, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Y.C.; Kannan, N.; Zhang, L.; Martinez, V.; Rosin, M.P.; Eaves, C.J. Characterization of Epithelial Progenitors in Normal Human Palatine Tonsils and Their HPV16 E6/E7-Induced Perturbation. Stem Cell Rep. 2015, 5, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjänen, S. Oral Manifestations of Human Papillomavirus Infections. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 126, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezal, M.; Sullivan Nasca, M.; Stoler, D.L.; Melendy, T.; Hyland, A.; Smaldino, P.J.; Rigual, N.R.; Loree, T.R. Chronic Periodontitis−Human Papillomavirus Synergy in Base of Tongue Cancers. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2009, 135, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G.; Surace, G.; De Stefano, R.; Laino, L.; D’Amico, C.; Fiorillo, M.T.; Meto, A.; Herford, A.S.; Arzukanyan, A.V.; et al. Human Papilloma Virus: Current Knowledge and Focus on Oral Health. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, F.J.; Romanos, M.A. E1 Protein of Human Papillomavirus Is a DNA Helicase/ATPase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 5817–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, I.J.; Clark, R.; Sun, S.; Androphy, E.J.; MacPherson, P.; Botchan, M.R. Targeting the E1 Replication Protein to the Papillomavirus Origin of Replication by Complex Formation with the E2 Transactivator. Science 1990, 250, 1694–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierry, F.; Yaniv, M. The BPV1-E2 Trans-Acting Protein Can Be Either an Activator or a Repressor of the HPV18 Regulatory Region. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 3391–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werness, B.A.; Levine, A.J.; Howley, P.M. Association of Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18 E6 Proteins with P53. Science 1990, 248, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffner, M.; Werness, B.A.; Huibregtse, J.M.; Levine, A.J.; Howley, P.M. The E6 Oncoprotein Encoded by Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18 Promotes the Degradation of P53. Cell 1990, 63, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, S.N.; Wazer, D.E.; Band, V. E7 Protein of Human Papilloma Virus-16 Induces Degradation of Retinoblastoma Protein through the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 4620–4624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flores, E.R.; Allen-Hoffmann, B.L.; Lee, D.; Lambert, P.F. The Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E7 Oncogene Is Required for the Productive Stage of the Viral Life Cycle. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6622–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin-Drubin, M.E.; Bromberg-White, J.L.; Meyers, C. The Role of the Human Papillomavirus Type 18 E7 Oncoprotein during the Complete Viral Life Cycle. Virology 2005, 338, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L.; Westra, W. Oropharyngeal Carcinoma with a Special Focus on HPV-Related Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2023, 18, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, L.; Neelsen, K.J.; Lukas, J. Replication Catastrophe: When a Checkpoint Fails Because of Exhaustion. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebner, C.M.; Laimins, L.A. Human Papillomaviruses: Basic Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Oncogenicity. Rev. Med. Virol. 2006, 16, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanier, K.; ould M’hamed ould Sidi, A.; Boulade-Ladame, C.; Rybin, V.; Chappelle, A.; Atkinson, A.; Kieffer, B.; Travé, G. Solution Structure Analysis of the HPV16 E6 Oncoprotein Reveals a Self-Association Mechanism Required for E6-Mediated Degradation of P53. Structure 2012, 20, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenellenbogen, R. Telomerase Induction in HPV Infection and Oncogenesis. Viruses 2017, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulet, G.; Horvath, C.; Broeck, D.V.; Sahebali, S.; Bogers, J. Human Papillomavirus: E6 and E7 Oncogenes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 2006–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.N.; Rothan, H.A.; Yusoff, M.S.M. The Association of Mammalian DREAM Complex and HPV16 E7 Proteins. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DiMaio, D.; Petti, L.M. The E5 Proteins. Virology 2013, 445, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, G.F.; Banks, L. The Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-6 and HPV-16 E5 Proteins Co-Operate with HPV-16 E7 in the Transformation of Primary Rodent Cells. J. Gen. Virol. 1995, 76, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, K.L.; Brockwell, N.K.; Parker, B.S. JAK-STAT Signaling: A Double-Edged Sword of Immune Regulation and Cancer Progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.L.; Macdonald, A. Autocrine STAT3 Activation in HPV Positive Cervical Cancer through a Virus-Driven Rac1—NFκB—IL-6 Signalling Axis. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröer, N.; Pahne, J.; Walch, B.; Wickenhauser, C.; Smola, S. Molecular Pathobiology of Human Cervical High-Grade Lesions: Paracrine STAT3 Activation in Tumor-Instructed Myeloid Cells Drives Local MMP-9 Expression. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Delgado, J.; Bulut, G.; Liu, X.; Cortés-Malagón, E.M.; Schlegel, R.; Flores-Maldonado, C.; Contreras, R.G.; Chung, S.-H.; Lambert, P.F.; Üren, A.; et al. The E6 Oncoprotein from HPV16 Enhances the Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Skin Epidermis In Vivo. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.C. High Frequency of Activating PIK3CA Mutations in Human Papillomavirus–Positive Oropharyngeal CancerPIK3CA in HPV+ Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2013, 139, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, V.W.Y.; Hedberg, M.L.; Li, H.; Vangara, B.S.; Pendleton, K.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Du, Y.; Gilbert, B.R.; et al. Frequent Mutation of the PI3K Pathway in Head and Neck Cancer Defines Predictive Biomarkers. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, G.J.; Kacew, A.; Chau, N.G.; Shivdasani, P.; Lorch, J.H.; Uppaluri, R.; Haddad, R.I.; MacConaill, L.E. Improved Outcomes in PI3K-Pathway-Altered Metastatic HPV Oropharyngeal Cancer. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e122799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.-S.; Kato, I.; Kim, H.-R.C. A Novel Function of HPV16-E6/E7 in Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 435, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, I.S.; Lavorato-Rocha, A.M.; De M Maia, B.; Stiepcich, M.M.A.; De Carvalho, F.M.; Baiocchi, G.; Soares, F.A.; Rocha, R.M. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition-like Events in Vulvar Cancer and Its Relation with HPV. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maufort, J.P.; Genther Williams, S.M.; Pitot, H.C.; Lambert, P.F. Human Papillomavirus 16 E5 Oncogene Contributes to Two Stages of Skin Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 6106–6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.L.; Coleman, D.T.; Kelly, K.C.; Carroll, J.L.; Woodby, B.; Songock, W.K.; Cardelli, J.A.; Bodily, J.M. Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E5-Mediated Upregulation of Met in Human Keratinocytes. Virology 2018, 519, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coursey, T.L.; McBride, A.A. Hitchhiking of Viral Genomes on Cellular Chromosomes. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbach, A.; Riemer, A.B. Immune Evasion Mechanisms of Human Papillomavirus: An Update. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.A. Epithelial Cell Responses to Infection with Human Papillomavirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Ramalho, A.C.; Marques, M.; Ribeiro, D. The Interplay between Antiviral Signalling and Carcinogenesis in Human Papillomavirus Infections. Cancers 2020, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.L. Harnessing Immunity for Therapy in Human Papillomavirus Driven Cancers. Tumour Virus Res. 2021, 11, 200212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, J.; Lowy, D. Explanations for the High Potency of HPV Prophylactic Vaccines. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4768–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiding, J.W.; Holland, S.M. Warts and All: Human Papillomavirus in Primary Immunodeficiencies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 1030–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Park, J.W.; Pitot, H.C.; Lambert, P.F. Loss of Dependence on Continued Expression of the Human Papillomavirus 16 E7 Oncogene in Cervical Cancers and Precancerous Lesions Arising in Fanconi Anemia Pathway-Deficient Mice. mBio 2016, 7, e00628–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M.S.; Ashrafi, G.H.; Campo, M.S. All 4 Di-leucine Motifs in the First Hydrophobic Domain of the E5 Oncoprotein of Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Are Essential for Surface MHC Class I Downregulation Activity and E5 Endomembrane Localization. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCarlo, C.A.; Rosa, B.; Jackson, R.; Niccoli, S.; Escott, N.G.; Zehbe, I. Toll-Like Receptor Transcriptome in the HPV-Positive Cervical Cancer Microenvironment. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, R.; Meyers, C.; Backendorf, C.; Ludigs, K.; Offringa, R.; Van Ommen, G.-J.B.; Melief, C.J.M.; Van Der Burg, S.H.; Boer, J.M. Human Papillomavirus Deregulates the Response of a Cellular Network Comprising of Chemotactic and Proinflammatory Genes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caberg, J.-H.; Hubert, P.; Herman, L.; Herfs, M.; Roncarati, P.; Boniver, J.; Delvenne, P. Increased Migration of Langerhans Cells in Response to HPV16 E6 and E7 Oncogene Silencing: Role of CCL20. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2009, 58, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudouin, R.; Hans, S.; Lisan, Q.; Morin, B.; Adimi, Y.; Martin, J.; Lechien, J.R.; Tartour, E.; Badoual, C. Prognostic Significance of the Microenvironment in Human Papillomavirus Oropharyngeal Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. The Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloura, V.; Izumchenko, E.; Zuo, Z.; Bao, R.; Korzinkin, M.; Ozerov, I.; Zhavoronkov, A.; Sidransky, D.; Bedi, A.; Hoque, M.O.; et al. Immune Profiles in Primary Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Oral Oncol. 2019, 96, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.; Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Desrichard, A.; Havel, J.J.; Dalin, M.G.; Riaz, N.; Lee, K.-W.; Ganly, I.; Hakimi, A.A.; Chan, T.A.; et al. The Head and Neck Cancer Immune Landscape and Its Immunotherapeutic Implications. JCI Insight 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welters, M.J.P.; Ma, W.; Santegoets, S.J.A.M.; Goedemans, R.; Ehsan, I.; Jordanova, E.S.; Van Ham, V.J.; Van Unen, V.; Koning, F.; Van Egmond, S.I.; et al. Intratumoral HPV16-Specific T Cells Constitute a Type I–Oriented Tumor Microenvironment to Improve Survival in HPV16-Driven Oropharyngeal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, A.; Pring, M.; Thomas, S.J.; Waylen, A.; Ness, A.R.; Dudding, T.; Pawlita, M.; Brenner, N.; Waterboer, T.; Schroeder, L. Survival Advantage in Patients with Human Papillomavirus-driven Oropharyngeal Cancer and Variation by Demographic Characteristics and Serologic Response: Findings from Head and Neck 5000. Cancer 2021, 127, 2442–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, A.; Parisatto, B.; Menegaldo, A.; Spinato, G.; Guido, M.; Del Mistro, A.; Bussani, R.; Zanconati, F.; Tofanelli, M.; Tirelli, G.; et al. The Immune Microenvironment of HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multiparametric Quantitative and Spatial Analysis Unveils a Rationale to Target Treatment-Naïve Tumors with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.E.W.; Soulières, D.; Le Tourneau, C.; Dinis, J.; Licitra, L.; Ahn, M.-J.; Soria, A.; Machiels, J.-P.; Mach, N.; Mehra, R.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Methotrexate, Docetaxel, or Cetuximab for Recurrent or Metastatic Head-and-Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. The Lancet 2019, 393, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiwert, T.Y.; Burtness, B.; Mehra, R.; Weiss, J.; Berger, R.; Eder, J.P.; Heath, K.; McClanahan, T.; Lunceford, J.; Gause, C.; et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-012): An Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 1b Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtness, B.; Harrington, K.J.; Greil, R.; Soulières, D.; Tahara, M.; De Castro, G.; Psyrri, A.; Basté, N.; Neupane, P.; Bratland, Å.; et al. Pembrolizumab Alone or with Chemotherapy versus Cetuximab with Chemotherapy for Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-048): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. The Lancet 2019, 394, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona Lorduy, M.; Harris Ricardo, J.; Hernández Arenas, Y.; Medina Carmona, W. Use of Trichloroacetic Acid for Management of Oral Lesions Caused by Human Papillomavirus. Gen. Dent. 2018, 66, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Flores, S.; Esquivel-Pedraza, L.; Hernández-Salazar, A.; Charli-Joseph, Y.; Saeb-Lima, M. Focal Epithelial Hyperplasia in Adult Patients With HIV Infection: Clearance With Topical Imiquimod. Skinmed 2016, 14, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.S.; Pajak, T.F.; Forastiere, A.A.; Jacobs, J.; Campbell, B.H.; Saxman, S.B.; Kish, J.A.; Kim, H.E.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rotman, M.; et al. Postoperative Concurrent Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for High-Risk Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goon, P.K.; Stanley, M.A.; Ebmeyer, J.; Steinsträsser, L.; Upile, T.; Jerjes, W.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Görner, M.; Sudhoff, H.H. HPV & Head and Neck Cancer: A Descriptive Update. Head Neck Oncol. 2009, 1, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, R.M.; Shimunov, D.; Weinstein, G.S.; Cannady, S.B.; Lukens, J.N.; Lin, A.; Swisher-McClure, S.; Bauml, J.M.; Aggarwal, C.; Cohen, R.B.; et al. Increased Rate of Recurrence and High Rate of Salvage in Patients with Human Papillomavirus–Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Adverse Features Treated with Primary Surgery without Recommended Adjuvant Therapy. Head Neck 2021, 43, 1128–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INTEGRATE (The UK ENT Trainee Research Network) Post-Treatment Head and Neck Cancer Care: National Audit and Analysis of Current Practice in the United Kingdom. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2021, 46, 284–294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvis, M.M.; Borges, G.A.; Oliveira, T.B.D.; Toledo, I.P.D.; Castilho, R.M.; Guerra, E.N.S.; Kowalski, L.P.; Squarize, C.H. Immunotherapy Improves Efficacy and Safety of Patients with HPV Positive and Negative Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 150, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Ismaila, N.; Bauman, J.E.; Dabney, R.; Gan, G.; Jordan, R.; Kaufman, M.; Kirtane, K.; McBride, S.M.; Old, M.O.; et al. Immunotherapy and Biomarker Testing in Recurrent and Metastatic Head and Neck Cancers: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1132–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiwert, T.Y.; Zuo, Z.; Keck, M.K.; Khattri, A.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Stricker, T.; Brown, C.; Pugh, T.J.; Stojanov, P.; Cho, J.; et al. Integrative and Comparative Genomic Analysis of HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Available online:. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Joura, E.A.; Giuliano, A.R.; Iversen, O.-E.; Bouchard, C.; Mao, C.; Mehlsen, J.; Moreira, E.D.; Ngan, Y.; Petersen, L.K.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; et al. A 9-Valent HPV Vaccine against Infection and Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research, C. for B.E. and Cervarix. FDA 2022. [Google Scholar]

- HPV Vaccination Recommendations | CDC Available online:. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Pinto, L.A.; Kemp, T.J.; Torres, B.N.; Isaacs-Soriano, K.; Ingles, D.; Abrahamsen, M.; Pan, Y.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Salmeron, J.; Giuliano, A.R. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Induces HPV-Specific Antibodies in the Oral Cavity: Results From the Mid-Adult Male Vaccine Trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1276–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, J.M.; Chang, M.; Resto, V.A.; Guo, F.; Berenson, A.B. Prevalence of Oral Human Papillomavirus by Vaccination Status among Young Adults (18–30 Years Old). Vaccine 2017, 35, 3446–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.H.; Kemp, T.J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Giuliano, A.R.; Pinto, L.A. Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 Specific Antibody Measurements in Saliva Collected in Oral Rinses and Merocel® Sponges. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2705–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKloe, J.; Urdang, Z.D.; Martinez Outschoorn, U.E.; Curry, J.M. Effects of HPV Vaccination on the Development of HPV-Related Cancers: A Retrospective Analysis of a United States-Based Cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 10507–10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, W.R.; Sood, A.J.; Nguyen, S.A.; Day, T.A. Initial Symptoms in Patients With HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Oropharyngeal Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2014, 140, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.B.; Ting, P.; Pai, A.; Russo, J.L.; Bakst, R.; Chai, R.L.; Teng, M.S.; Genden, E.M.; Miles, B.A. Initial Presentation of Human Papillomavirus-related Head and Neck Cancer: A Retrospective Review. The Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S. P16 Immunohistochemistry As a Standalone Test for Risk Stratification in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012, 6, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhry, C.; Ferris, R.L. P16 as a Prognostic Biomarker for Nonoropharyngeal Squamous Cell Cancers: Avatar or Mirage? JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.M.; Rubenstein, L.M.; Hoffman, H.; Haugen, T.H.; Turek, L.P. Human Papillomavirus, P16 and P53 Expression Associated with Survival of Head and Neck Cancer. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2010, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, K.L.; Thomas, K.; Jeong, D.; Stallworth, D.G.; Arrington, J.A. Multimodal Imaging of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Control 2017, 24, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryne, M.; Koppang, H.S.; Lilleng, R.; Kjærheim, Å. Malignancy Grading of the Deep Invasive Margins of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas Has High Prognostic Value. J. Pathol. 1992, 166, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreimer, A.R.; Shiels, M.S.; Fakhry, C.; Johansson, M.; Pawlita, M.; Brennan, P.; Hildesheim, A.; Waterboer, T. Screening for Human Papillomavirus-driven Oropharyngeal Cancer: Considerations for Feasibility and Strategies for Research. Cancer 2018, 124, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan Rajsri, K.; K. Durab, S.; A. Varghese, I.; Vigneswaran, N.; T. McDevitt, J.; Kerr, A.R. A Brief Review of Cytology in Dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 2024, 236, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, M.P.; Srinivasan Rajsri, K.; Ross Kerr, A.; Vigneswaran, N.; Redding, S.W.; Janal, M.; Kang, S.K.; Palomo, L.; Christodoulides, N.J.; Singh, M.; et al. A Cytomics-on-a-Chip Platform and Diagnostic Model Stratifies Risk for Oral Lichenoid Conditions. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2024, S221244032400155X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broglie, M.A.; Jochum, W.; Förbs, D.; Schönegg, R.; Stoeckli, S.J. Brush Cytology for the Detection of High-risk HPV Infection in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015, 123, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, P.; De La Oliva, J.; Alos, S.; Perez, F.; Vega, N.; Vilaseca, I.; Marti, C.; Ferrer, A.; Alos, L. Accuracy of Liquid-Based Brush Cytology and HPV Detection for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Oropharyngeal and Oral Cancer. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 2587–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benevolo, M.; Rollo, F.; Giuliani, M.; Pichi, B.; Latini, A.; Pellini, R.; Vescio, M.F.; Morrone, A.; Cristaudo, A.; Donà, M.G. Abnormal Cytology in Oropharyngeal Brushings and in Oral Rinses Is Not Associated with HPV Infection: The OHMAR Study. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020, 128, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingen, M.W. Brush-Based Cytology Screening in the Tonsils and Cervix: There Is a Difference! Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila. Pa.) 2011, 4, 1350–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).