Submitted:

26 March 2024

Posted:

27 March 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods of the Scoping Review

2.2. Recruitment of Scientific Board Members and Panelists

2.3. Conduction of the Delphi Survey

2.4. Data Analysis and Consensus Definition

3. Results

3.1. Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Medical Literature

3.2. Results of the Delphi Survey

3.2.1. Characteristics of the Survey Panelists

3.2.2. Delphi Survey Rounds

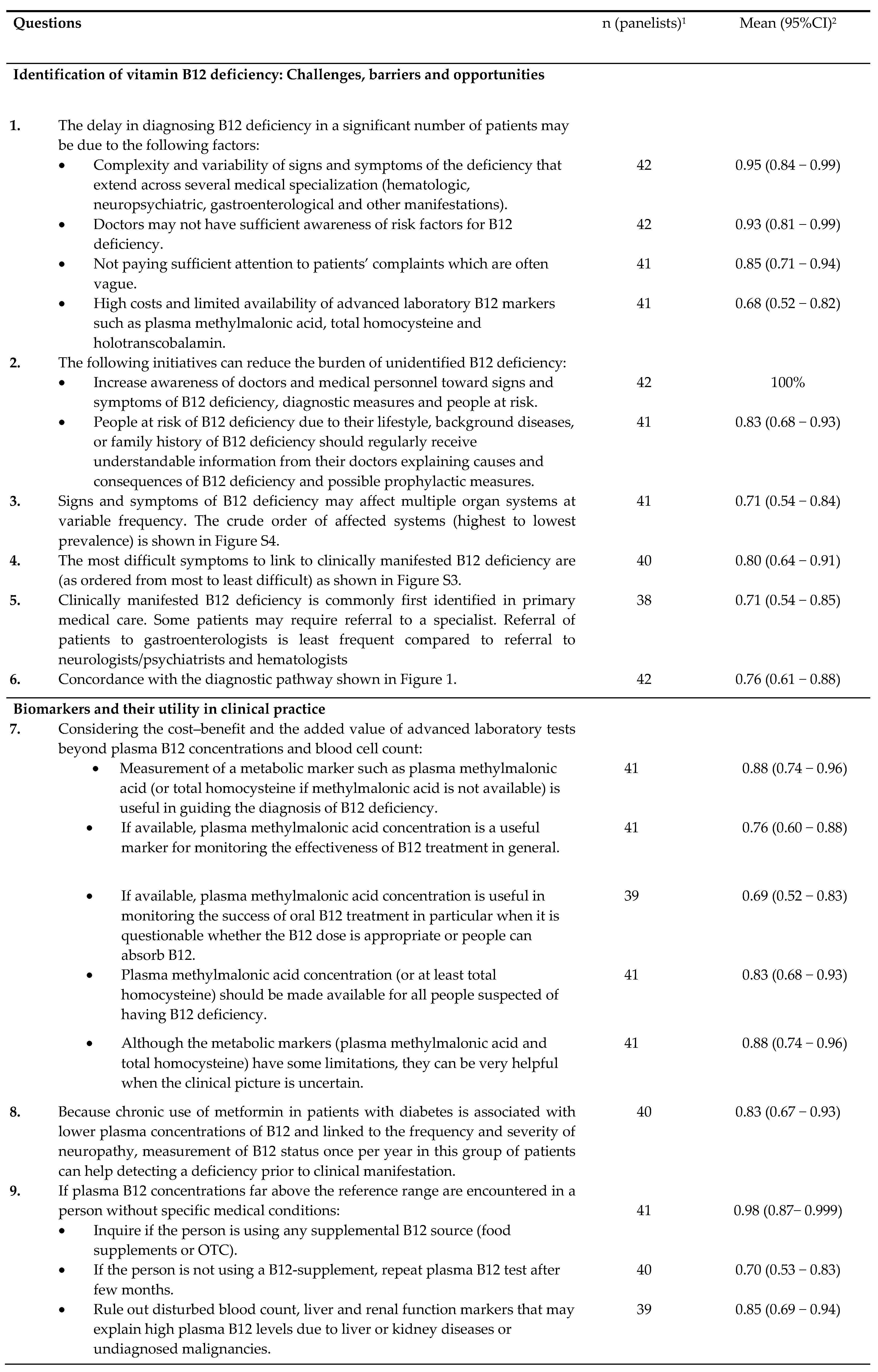

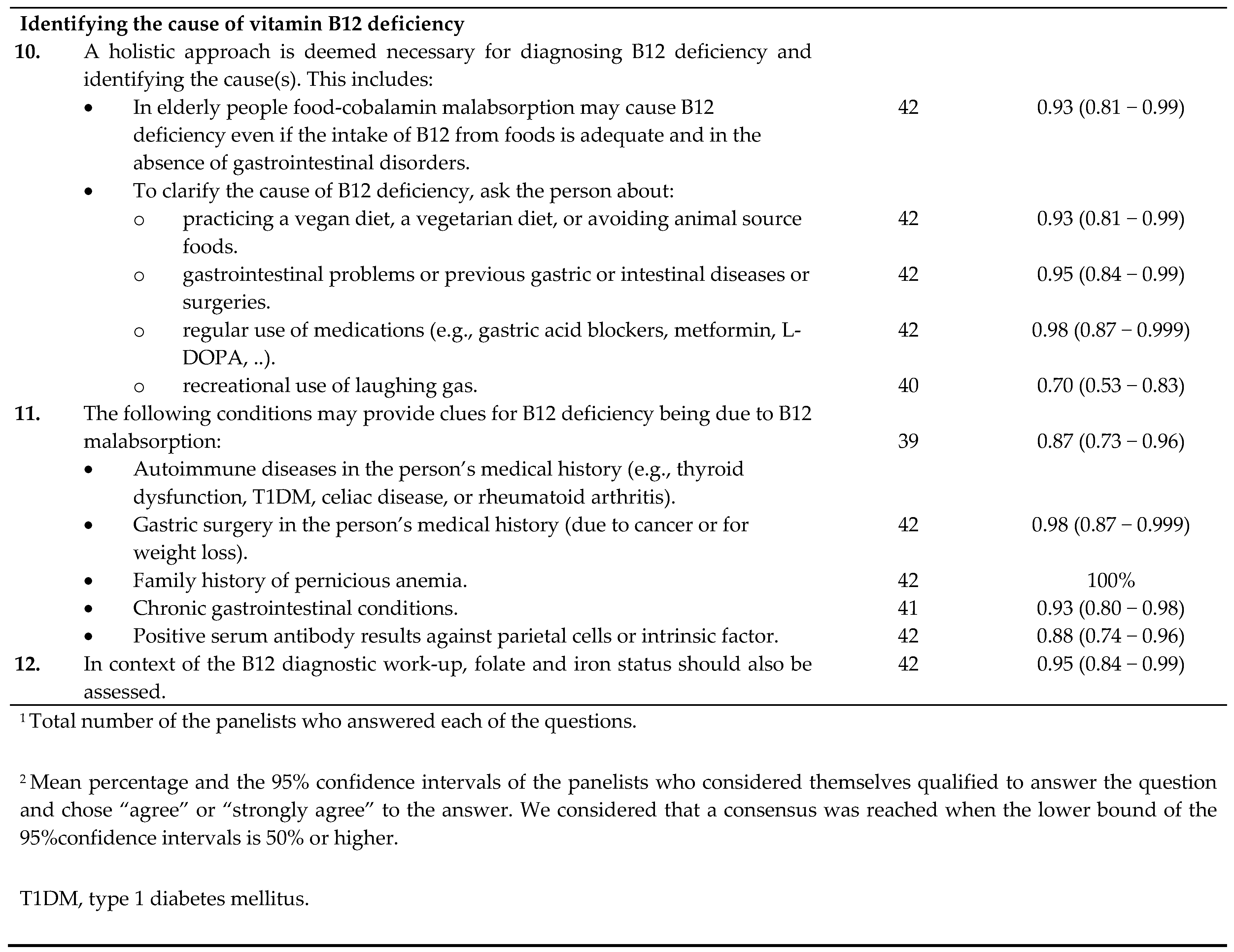

3.2.3. Consensus on the Clinical Practice of Diagnosing Vitamin B12 Deficiency

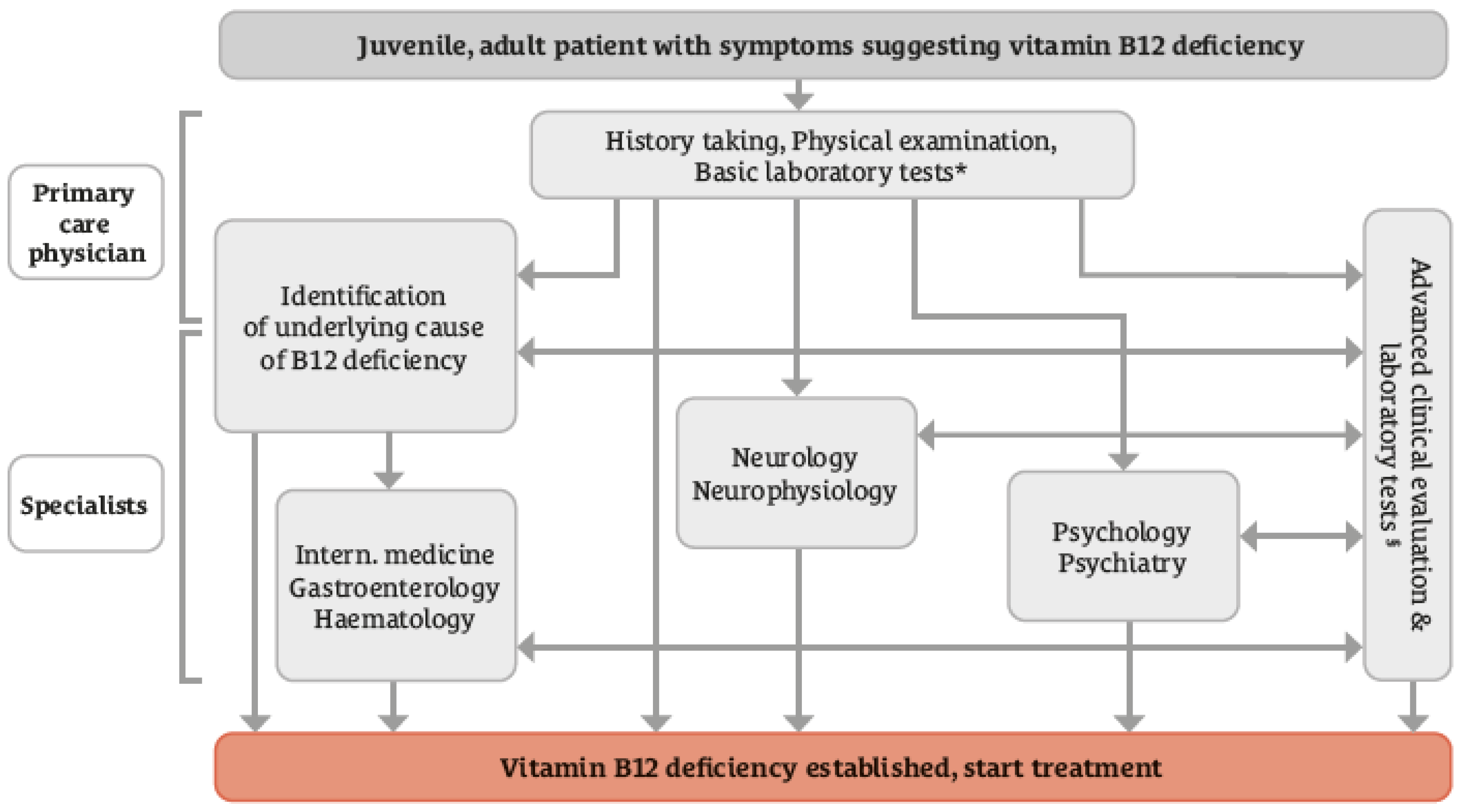

3.2.4. Consensus for Clinical Practices of Treatment, Prophylaxis, and Long-Term Management of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

4. Discussion

4.1. Delphi Consensus

4.2. Additional Points Raised in the Board Discussion

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

- Agata Sobczyńska-Malefora, Nutristasis Unit, Haemostasis & Thrombosis, St. Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK.

- Aleksandra Araszkiewicz, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland.

- Anne M Molloy, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

- Bruno Annibale, Department of Medical Surgical and Translational, Medicine Sapienza University, Rome, Italy.

- Christine A.F. von Arnim, Department of Geriatrics, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany.

- Christy C Tangney, PhD, FACN, CNS, Departments of Clinical Nutrition & Preventive Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, 600 S Paulina St, Room 716 ACC, Chicago, USA.

- David Smith, Department of Pharmacology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- Dinh Tung Do, Hanoi Saint Paul Hospital, Vietnam.

- Dongming Zheng, Department of Neurology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, China.

- Edith Lahner, Sapienza University of Rome, Department of Medical-surgical sciences and translational medicine, Italy.

- Gabriela Spulber, Clinical geriatrics, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

- Georgeta Daniela Georgescu, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

- Francesca Mangialasche, Karolinska Institutet, Center for Alzheimer Research, Sweden.

- Hendrika (H.J.M.) Smelt, Obesity Center, Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

- Janet B McGill, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid, Campus Box 8127, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

- J. David Spence, Professor Emeritus of Neurology & Clinical Pharmacology, Western University, and Director, Stroke Prevention & Atherosclerosis Research Centre, Robarts Research Institute, London, ON, Canada.

- John Killen, Macquarie Medical School Sydney, Australia.

- P Julian Owen, Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Addenbrooke’s, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, Cambridge, UK.

- Lisette CPGM de Groot, Wageningen University, The Netherlands.

- Michelle Murphy, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Spain.

- G Bhanuprakash Reddy, ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad-500007, India.

- Pradeepa Rajendra, Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, Chennai, India.

- Ralph Green, University of California, Davis Medical Center

- Sadanand Naik, K.E.M. Hospital, Pune, India.

- Tsvetalina Tankova, Medical University, Sofia, Bulgaria.

- William Huynh, Randwick Clinical Campus, UNSW Medicine and Health; FMH Translation Research Collective, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; and Prince of Wales Hospital, Southern Neurology, Kogarah NSW, , Sydney, Australia.

- Wolfgang N. Löscher, Department of Neurology, Medical University Innsbruck, Austria.

- Zyta Beata Wojszel, Department of Geriatrics, Medical University of Bialystok, Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Healton, E.B.; Savage, D.G.; Brust, J.C.M.; Garrett, T.J.; Lindenbaum, J. Neurologic Aspects of Cobalamin Deficiency. Medicine 1991, 70, 229–245, . [CrossRef]

- Divate, P.G.; Patanwala, R. Neurological manifestations of B(12) deficiency with emphasis on its aetiology. J Assoc Physicians India 2014, 62, 400–5.

- Kumar, S.; Vijayan, J.; Jacob, J.; Alexander, M.; Gnanamuthu, C.; Aaron, S. Clinical and laboratory features and response to treatment in patients presenting with vitamin B12 deficiency-related neurological syndromes. Neurol. India 2005, 53, 55, . [CrossRef]

- Lachner, C.; Martin, C.; John, D.; Nekkalapu, S.; Sasan, A.; Steinle, N.; Regenold, W.T. Older adult psychiatric inpatients with non-cognitive disorders should be screened for vitamin B12 deficiency. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2013, 18, 209–212, . [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Garg, R.K.; Gupta, P.K.; Roy, B.; Gupta, R.K. Prevalence of MR imaging abnormalities in vitamin B12 deficiency patients presenting with clinical features of subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 342, 162–166, . [CrossRef]

- Stabler, S.P.; Allen, R.H.; Savage, D.G.; Lindenbaum, J. Clinical spectrum and diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Blood 1990, 76, 871–81.

- Lindenbaum, J.; Healton, E.B.; Savage, D.G.; Brust, J.C.; Garrett, T.J.; Podell, E.R.; Margell, P.D.; Stabler, S.P.; Allen, R.H. Neuropsychiatric Disorders Caused by Cobalamin Deficiency in the Absence of Anemia or Macrocytosis. New Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 1720–1728, . [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, W.; Obeid, R. Utility and limitations of biochemical markers of vitamin B12 deficiency. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 231–237, . [CrossRef]

- Andrès, E.; Zulfiqar, A.-A.; Vogel, T. State of the art review: oral and nasal vitamin B12 therapy in the elderly. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2020 113, 5–15, . [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab OA, Abdelaziz A, Diab S, Khazragy A, Elboraay T, Fayad T et al. Efficacy of different routes of vitamin B12 supplementation for the treatment of patients with vitamin B12 deficiency: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ir J Med Sci 2024. [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.C.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Cannings-John, R.; McCaddon, A.; Hood, K.; Papaioannou, A.; Mcdowell, I.; Goringe, A. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Fam. Pr. 2006, 23, 279–285, . [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Li L, Qin LL, Song Y, Vidal-Alaball J, Liu TH. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;3:CD004655. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE. Vitamin B12 deficiency in over 16s: diagnosis and management (NG239), www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng239. Accessed on 6-3-2024.

- Beiderbeck, D.; Frevel, N.; von der Gracht, H.A.; Schmidt, S.L.; Schweitzer, V.M. Preparing, conducting, and analyzing Delphi surveys: Cross-disciplinary practices, new directions, and advancements. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101401, . [CrossRef]

- Stabler SP. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med 2013;368:149-60. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Su, Z.-Y.; Xu, S.-B.; Liu, C.-C. Subacute Combined Degeneration: A Retrospective Study of 68 Cases with Short-Term Follow-Up. Eur. Neurol. 2018, 79, 247–255, . [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, M.; Dong, A.; Wu, Y.; Han, N.; Deng, B.; Bi, X. A retrospective study of 23 cases with subacute combined degeneration. Int J Neurosci 2016;126:872-7. [CrossRef]

- Linazi, G.; Abudureyimu, S.M.; Zhang, J.M.; Wulamu, A.M.; Maimaitiaili, M.M.; Wang, B.; Bakeer, B.; Xi, Y. Clinical features of different stage subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. Medicine 2022, 101, e30420, . [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Cao, J.; Shang, K.; Su, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, C. Correlation between anemia and clinical severity in subacute combined degeneration patients. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 80, 11–15, . [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Xu S, Liu C. Is serum vitamin B12 decrease a necessity for the diagnosis of subacute combined degeneration?: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e19700.

- Franques, J.; Chiche, L.; De Paula, A.M.; Grapperon, A.M.; Attarian, S.; Pouget, J.; Mathis, S. Characteristics of patients with vitamin B12-responsive neuropathy: a case series with systematic repeated electrophysiological assessment. Neurol. Res. 2019, 41, 569–576, . [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, P.; Kulkarni, J.D.; A Pai, S. Vitamin B12 deficiency in India: mean corpuscular volume is an unreliable screening parameter. Natl Med J India. 2012, 25, 336–8.

- Sanz-Cuesta, T.; Escortell-Mayor, E.; Cura-Gonzalez, I.; Martin-Fernandez, J.; Riesgo-Fuertes, R.; Garrido-Elustondo, S.; Mariño-Suárez, J.E.; Álvarez-Villalba, M.; Gómez-Gascón, T.; González-García, I.; et al. Oral versus intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency in primary care: a pragmatic, randomised, non-inferiority clinical trial (OB12). BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033687, . [CrossRef]

- Soykan, I.; Yakut, M.; Keskin, O.; Bektaş, M. Clinical Profiles, Endoscopic and Laboratory Features and Associated Factors in Patients with Autoimmune Gastritis. Digestion 2012, 86, 20–26, . [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-I.; Hyung, W.J.; Song, K.J.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, C.-B.; Noh, S.H. Oral Vitamin B12 Replacement: An Effective Treatment for Vitamin B12 Deficiency After Total Gastrectomy in Gastric Cancer Patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 3711–3717, . [CrossRef]

- Saperstein, D.S.; Wolfe, G.I.; Gronseth, G.S.; Nations, S.P.; Herbelin, L.L.; Bryan, W.W.; Barohn, R.J. Challenges in the Identification of Cobalamin-Deficiency Polyneuropathy. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 1296–1301, . [CrossRef]

- Adali Y, Binnetoglu K. Evaluation of the response to vitamin B12 supplementation in patients with atrophy in sleeve gastrectomy materials. Cir Cir 2022;90:17-23.

- Rajabally YA, Martey J. Neuropathy in Parkinson disease: prevalence and determinants. Neurology 2011;77:1947-50.

- Siswanto O, Smeall K, Watson T, Donnelly-Vanderloo M, O'Connor C, Foley N et al. Examining the Association between Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Dementia in High-Risk Hospitalized Patients. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:1003-8. [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.-C.; Lo, C.-P.; Chen, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-F. Correlation of Tc-99 m ethyl cysteinate dimer single-photon emission computed tomography and clinical presentations in patients with low cobalamin status. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 1–11, . [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Garg, R.K.; Rai, Y.; Roy, B.; Pandey, C.M.; Malhotra, H.S.; Narayana, P.A. DTI Correlates of Cognition in Conventional MRI of Normal-Appearing Brain in Patients with Clinical Features of Subacute Combined Degeneration and Biochemically Proven Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 35, 872–877, . [CrossRef]

- Warendorf, J.K.; van Doormaal, P.T.; Vrancken, A.F.; Verhoeven-Duif, N.M.; van Eijk, R.P.; Berg, L.H.v.D.; Notermans, N.C. Clinical relevance of testing for metabolic vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with polyneuropathy. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 25, 2536–2546, . [CrossRef]

- Tangney CC, Aggarwal NT, Li H, Wilson RS, DeCarli C, Evans DA et al. Vitamin B12, cognition, and brain MRI measures: A cross-sectional examination. Neurology 2011;77:1276-82. [CrossRef]

- Tangney, C.C.; Tang, Y.; Evans, D.A.; Morris, M.C. Biochemical indicators of vitamin B 12 and folate insufficiency and cognitive decline. Neurology 2009, 72, 361–367, . [CrossRef]

- Leishear, K.; Boudreau, R.M.; Studenski, S.A.; Ferrucci, L.; Rosano, C.; de Rekeneire, N.; Houston, D.K.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Schwartz, A.V.; Vinik, A.I.; et al. Relationship Between Vitamin B12 and Sensory and Motor Peripheral Nerve Function in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1057–1063, . [CrossRef]

- Solomon, L.R. Vitamin B12-responsive neuropathies: A case series. Nutr. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 162–168, . [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Jain, A.; Rohatgi, A. An observational study of vitamin b12 levels and peripheral neuropathy profile in patients of diabetes mellitus on metformin therapy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2018, 12, 51–58, . [CrossRef]

- Kancherla, V.; Elliott, J.L.; Patel, B.B.; Holland, N.W.; Johnson, T.M.; Khakharia, A.; Phillips, L.S.; Oakley, G.P.; Vaughan, C.P. Long-term Metformin Therapy and Monitoring for Vitamin B12 Deficiency Among Older Veterans. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1061–1066, . [CrossRef]

- Kos, E.; Liszek, M.J.; Emanuele, M.A.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Camacho, P. Effect of Metformin Therapy on Vitamin D and Vitamin B12 Levels in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Pr. 2012, 18, 179–184, . [CrossRef]

- Jayashri, R.; Venkatesan, U.; Rohan, M.; Gokulakrishnan, K.; Rani, C.S.S.; Deepa, M.; Anjana, R.M.; Mohan, V.; Pradeepa, R. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in South Indians with different grades of glucose tolerance. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 1283–1293, . [CrossRef]

- Bherwani, S.; Ahirwar, A.K.; Saumya, A.; Sandhya, A.; Prajapat, B.; Patel, S.; Jibhkate, S.B.; Singh, R.; Ghotekar, L. The study of association of Vitamin B 12 deficiency in type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without diabetic nephropathy in North Indian Population. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2017, 11, S365–S368, . [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Yun, J.-S.; Ko, S.-H.; Lim, T.-S.; Ahn, Y.-B.; Park, Y.-M.; Ko, S.-H. Higher Prevalence of Metformin-Induced Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Sulfonylurea Combination Compared with Insulin Combination in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e109878, . [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Karmakar, D.; Jha, R. Association of B12 deficiency and clinical neuropathy with metformin use in type 2 diabetes patients. J. Postgrad. Med. 2013, 59, 253–257, . [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.; Darling, A.; Brown, J. Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 42, 316–327, . [CrossRef]

- de Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, Wulffele MG, van der Kolk J, Bets D et al. Long term treatment with metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c2181. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yu, H.; Wu, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Qin, X.; Wu, T.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Y. Metformin treatment and risk of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Beijing, China. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1082720, . [CrossRef]

- Aroda, V.R.; Edelstein, S.L.; Goldberg, R.B.; Knowler, W.C.; Marcovina, S.M.; Orchard, T.J.; Bray, G.A.; Schade, D.S.; Temprosa, M.G.; White, N.H.; et al. Long-term Metformin Use and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1754–1761, . [CrossRef]

- Miyan Z, Waris N. Association of vitamin B(12) deficiency in people with type 2 diabetes on metformin and without metformin: a multicenter study, Karachi, Pakistan. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020;8.

- Parry-Strong, A.; Langdana, F.; Haeusler, S.; Weatherall, M.; Krebs, J. Sublingual vitamin B12 compared to intramuscular injection in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin: a randomised trial. N Z Med J. 2016, 129, 67–75.

- Mirkazemi, C.; Peterson, G.M.; Tenni, P.C.; Jackson, S.L. Vitamin B12 deficiency in Australian residential aged care facilities. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2012, 16, 277–280, . [CrossRef]

- Soh, Y.; Won, C.W. Association between frailty and vitamin B12 in the older Korean population. Medicine 2020, 99, e22327, . [CrossRef]

- Couderc, A.-.-L.; Camalet, J.; Schneider, S.; Turpin, J.-.-M.; Bereder, I.; Boulahssass, R.; Gonfrier, S.; Bayer, P.; Guerin, O.; Brocker, P. Cobalamin deficiency in the elderly: Aetiology and management. A study of 125 patients in a geriatric hospital. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2015, 19, 234–239, . [CrossRef]

- Andrès, E.; Affenberger, S.; Vinzio, S.; Kurtz, J.-E.; Noel, E.; Kaltenbach, G.; Maloisel, F.; Schlienger, J.-L.; Blicklé, J.-F. Food-cobalamin malabsorption in elderly patients: Clinical manifestations and treatment. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 1154–1159, . [CrossRef]

- Bulut, E.A.; Soysal, P.; Aydin, A.E.; Dokuzlar, O.; Kocyigit, S.E.; Isik, A.T. Vitamin B12 deficiency might be related to sarcopenia in older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 95, 136–140, . [CrossRef]

- Juncà, J.; de Soria, P.L.; Granada, M.L.; Flores, A.; Márquez, E. Detection of early abnormalities in gastric function in first-degree relatives of patients with pernicious anemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2006, 77, 518–522, . [CrossRef]

- Misra, U.K.; Kalita, J. Comparison of clinical and electrodiagnostic features in B12 deficiency neurological syndromes with and without antiparietal cell antibodies. Heart 2007, 83, 124–127, . [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.W.; Muegge, B.D.; Tobin, G.S.; Litvin, M.; Sun, L.; Saenz, J.B.; Gyawali, C.P.; McGill, J.B. High-Risk Gastric Pathology and Prevalent Autoimmune Diseases in Patients with Pernicious Anemia. Endocr. Pr. 2017, 23, 1297–1303, . [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-T.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Kong, Y.; Sun, N.-N.; Dong, A.-Q. Correlation between serum vitamin B12 level and peripheral neuropathy in atrophic gastritis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 1343–1352, . [CrossRef]

- Miceli, E.; Lenti, M.V.; Padula, D.; Luinetti, O.; Vattiato, C.; Monti, C.M.; Di Stefano, M.; Corazza, G.R. Common Features of Patients With Autoimmune Atrophic Gastritis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 812–814, . [CrossRef]

- Ao M, Tsuji H, Shide K, Kosaka Y, Noda A, Inagaki N et al. High prevalence of vitamin B-12 insufficiency in patients with Crohn's disease. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2017;26:1076-81.

- Madanchi, M.; Fagagnini, S.; Fournier, N.; Biedermann, L.; Zeitz, J.; Battegay, E.; Zimmerli, L.; Vavricka, S.R.; Rogler, G.; Scharl, M.; et al. The Relevance of Vitamin and Iron Deficiency in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Patients of the Swiss IBD Cohort. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1768–1779, . [CrossRef]

- Yakut, M.; Üstün, Y.; Kabaçam, G.; Soykan, I. Serum vitamin B12 and folate status in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 21, 320–323, . [CrossRef]

- Schøsler, L.; Christensen, L.A.; Hvas, C.L. Symptoms and findings in adult-onset celiac disease in a historical Danish patient cohort. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 51, 288–294, . [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.; van Oijen, M.; Janssen, M.; van Asten, H.; Laheij, R.; Jansen, J. Vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Dig. Liver Dis. 2006, 38, 438–439, . [CrossRef]

- Schiavon CA, Bhatt DL, Ikeoka D, Santucci EV, Santos RN, Damiani LP et al. Three-Year Outcomes of Bariatric Surgery in Patients With Obesity and Hypertension : A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:685-93. [CrossRef]

- Schijns W, Schuurman LT, Melse-Boonstra A, van Laarhoven CJHM, Berends FJ, Aarts EO. Do specialized bariatric multivitamins lower deficiencies after RYGB? Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14:1005-12. [CrossRef]

- Vilarrasa, N.; Fabregat, A.; Toro, S.; Gordejuela, A.G.; Casajoana, A.; Montserrat, M.; Garrido, P.; López-Urdiales, R.; Virgili, N.; Planas-Vilaseca, A.; et al. Nutritional deficiencies and bone metabolism after endobarrier in obese type 2 patients with diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1447–1450, . [CrossRef]

- Bilici A, Sonkaya A, Ercan S, Ustaalioglu BB, Seker M, Aliustaoglu M et al. The changing of serum vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer: do they associate with clinicopathological factors? Tumour Biol 2015;36:823-8. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Kim HI, Hyung WJ, Song KJ, Lee JH, Kim YM et al. Vitamin B(12) deficiency after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an analysis of clinical patterns and risk factors. Ann Surg 2013;258:970-5. [CrossRef]

- Rozgony NR, Fang C, Kuczmarski MF, Bob H. Vitamin B(12) deficiency is linked with long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in institutionalized older adults: could a cyanocobalamin nasal spray be beneficial? J Nutr Elder 2010;29:87-99. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Hara, K.; Maezawa, Y.; Kazama, K.; Hashimoto, I.; Sawazaki, S.; Komori, K.; Tamagawa, H.; Tamagawa, A.; Kano, K.; et al. Clinical Course of Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Associated Risk Factors in Patients After Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2023, 43, 689–694, . [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ruiz, A.G.; Hernández-Rivera, G.; Herrera, M.F. Prevalence of Iron, Folate, and Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anemia After Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes. Surg. 2008, 18, 288–293, . [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Maezawa, Y.; Cho, H.; Saigusa, Y.; Tamura, J.; Tsuchida, K.; Komori, K.; Kano, K.; Segami, K.; Hara, K.; et al. Phase II Study of a Multi-center Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate Oral Vitamin B12 Treatment for Vitamin B12 Deficiency After Total Gastrectomy in Gastric Cancer Patients. Anticancer. Res. 2022, 42, 3963–3970, . [CrossRef]

- Mahawar, K.K.; Reid, A.; Graham, Y.; Callejas-Diaz, L.; Parmar, C.; Carr, W.R.; Jennings, N.; Singhal, R.; Small, P.K. Oral Vitamin B12 Supplementation After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: a Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 1916–1923, . [CrossRef]

- Smelt, H.J.M.; Pouwels, S.; Smulders, J.F. Different Supplementation Regimes to Treat Perioperative Vitamin B12 Deficiencies in Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2016, 27, 254–262, . [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Soriano, J.; Cruz, A.L.; Dasanu, C.A. Vitamin B12 deficiency in patients undergoing bariatric surgery: Preventive strategies and key recommendations. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2013, 9, 1013–1019, . [CrossRef]

- Engebretsen, K.V.; Blom-Høgestøl, I.K.; Hewitt, S.; Risstad, H.; Moum, B.; Kristinsson, J.A.; Mala, T. Anemia following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity; a 5-year follow-up study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 917–922, . [CrossRef]

- Antoine, D.; Li, Z.; Quilliot, D.; Sirveaux, M.-A.; Meyre, D.; Mangeon, A.; Brunaud, L.; Guéant, J.-L.; Guéant-Rodriguez, R.-M. Medium term post-bariatric surgery deficit of vitamin B12 is predicted by deficit at time of surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 40, 87–93, . [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.C.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Cannings-John, R.; McCaddon, A.; Hood, K.; Papaioannou, A.; Mcdowell, I.; Goringe, A. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Fam. Pr. 2006, 23, 279–285, . [CrossRef]

- Namikawa, T.; Maeda, M.; Yokota, K.; Iwabu, J.; Munekage, M.; Uemura, S.; Maeda, H.; Kitagawa, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Hanazaki, K. Enteral Vitamin B12 Supplementation Is Effective for Improving Anemia in Patients Who Underwent Total Gastrectomy. Oncology 2021, 99, 225–233, . [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Agarwal, R.; Chandra, S.; Misra, U.K. A study of neurobehavioral, clinical psychometric, and P3 changes in vitamin B12 deficiency neurological syndrome. Nutr. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 39–46, . [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudlou, P.; Varlamova, J.; Pandit, J. Patients with unexplained neurological symptoms and signs should be screened for vitamin B12 deficiency regardless of haemoglobin levels. Eye 2021, 36, 1124–1125, . [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Garg, R.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Malhotra, H.S.; Paliwal, V.K.; Rathore, R.K.S.; Verma, R.; Singh, M.K.; Rai, Y.; Pandey, C.M. Diffusion tensor tractography and neuropsychological assessment in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. Neuroradiology 2013, 56, 97–106, . [CrossRef]

- Reynolds E. Vitamin B12, folic acid, and the nervous system. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:949-60. [CrossRef]

- Puri, V.; Chaudhry, N.; Goel, S.; Gulati, P.; Nehru, R.; Chowdhury, D. Vitamin B12 deficiency: a clinical and electrophysiological profile. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 2005, 45, 273–84.

- Misra, U.K.; Kalita, J.; Das, A. Vitamin B12 deficiency neurological syndromes: a clinical, MRI and electrodiagnostic study. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2003, 43, 57–64.

- Bolaman, Z.; Kadikoylu, G.; Yukselen, V.; Yavasoglu, I.; Barutca, S.; Senturk, T. Oral versus intramuscular cobalamin treatment in megaloblastic anemia: A single-center, prospective, randomized, open-label study. Clin. Ther. 2003, 25, 3124–3134, . [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.-P.; Ren, C.-P.; Cheng, J.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, B.-B.; Fan, Y.-Z. Conventional MRI for diagnosis of subacute combined degeneration (SCD) of the spinal cord due to vitamin B-12 deficiency. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016, 25, 34–8, . [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Trivedi, R.; Garg, R.K.; Gupta, P.K.; Tyagi, R.; Gupta, R.K. Assessment of functional and structural damage in brain parenchyma in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency: A longitudinal perfusion and diffusion tensor imaging study. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 537–543, . [CrossRef]

- Yang W, Cai X, Wu H, Ji L. Associations between metformin use and vitamin B(12) levels, anemia, and neuropathy in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes 2019;11:729-43. [CrossRef]

- Ceravolo R, Cossu G, Bandettini di PM, Santoro L, Barone P, Zibetti M et al. Neuropathy and levodopa in Parkinson's disease: evidence from a multicenter study. Mov Disord 2013;28:1391-7. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Park, D.; Ko, P.-W.; Kang, K.; Lee, H.-W. Serum methylmalonic acid correlates with neuropathic pain in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1799–1804, . [CrossRef]

- Jhunjhnuwala, D.; Tanglay, O.; Briggs, N.E.; Yuen, M.T.Y.; Huynh, W. Prognostic indicators of subacute combined degeneration from B12 deficiency: A systematic review. PM&R 2022, 14, 504–514, . [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).