Submitted:

18 March 2024

Posted:

19 March 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

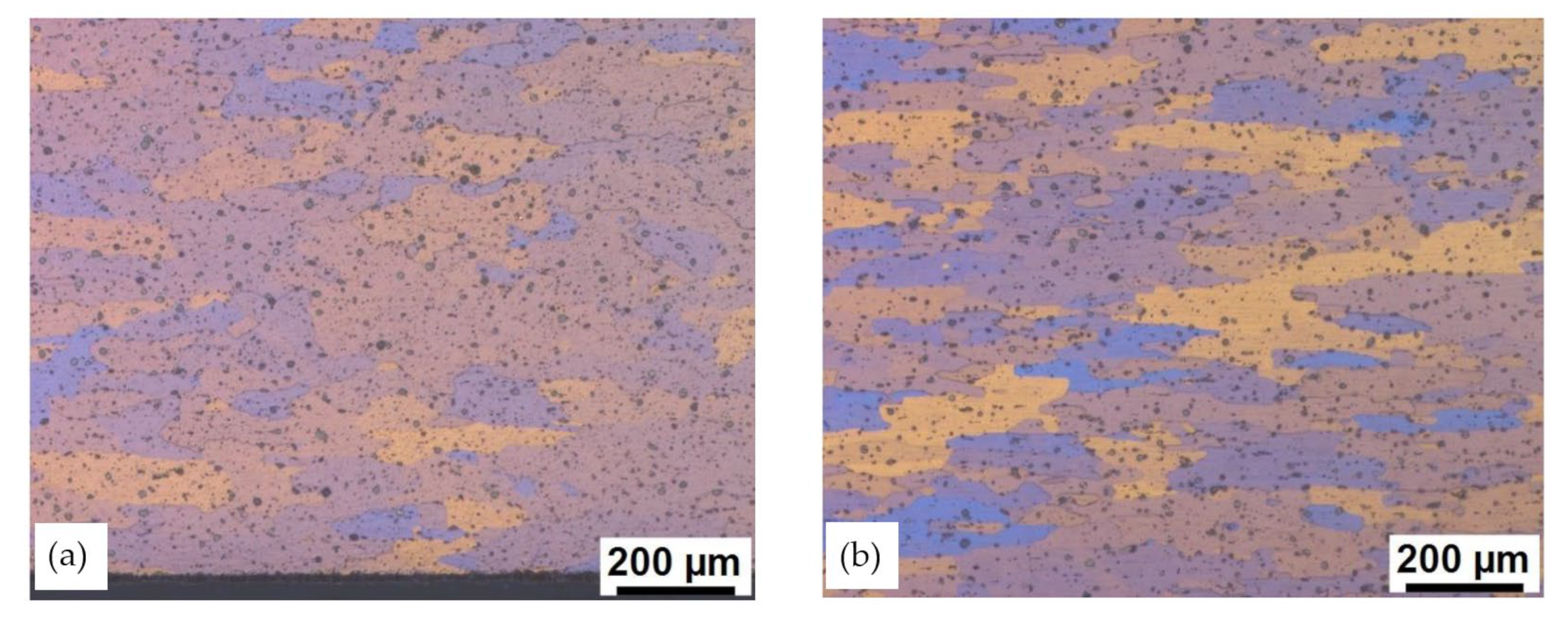

2.1. Description of AA6082

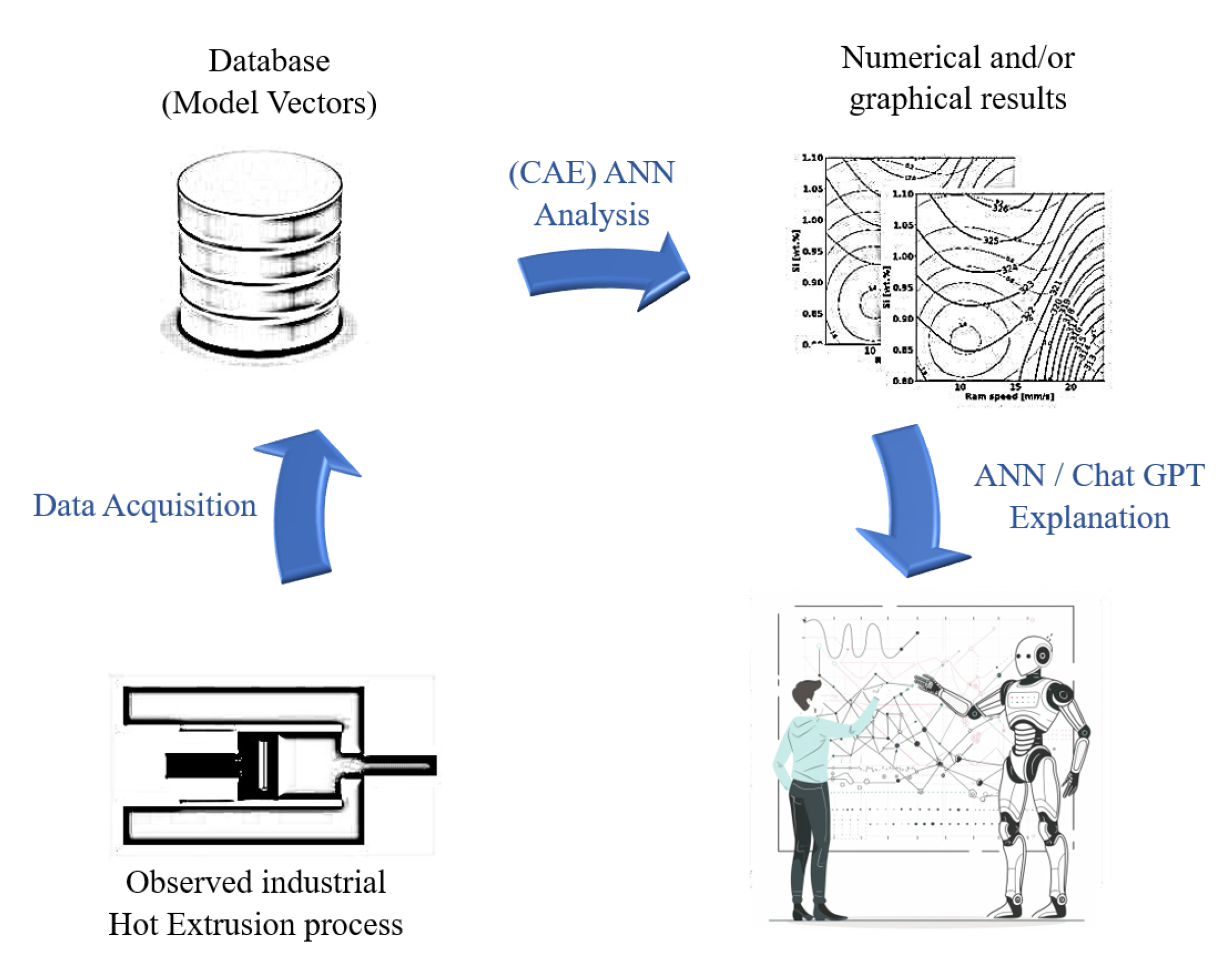

2.2. CAE Artificial Neural Network

- Local standard error (also, standard deviation) of the prediction is calculated by the formulae [32]:

- Estimation of reliability of the predicted mean value based on data density is calculated by the formulae [1]:

2.3. General Framework for the Automatic Explanation of the Obtained Results by the (CAE) ANN

3. Results

3.1. Rules for Explaining the Results

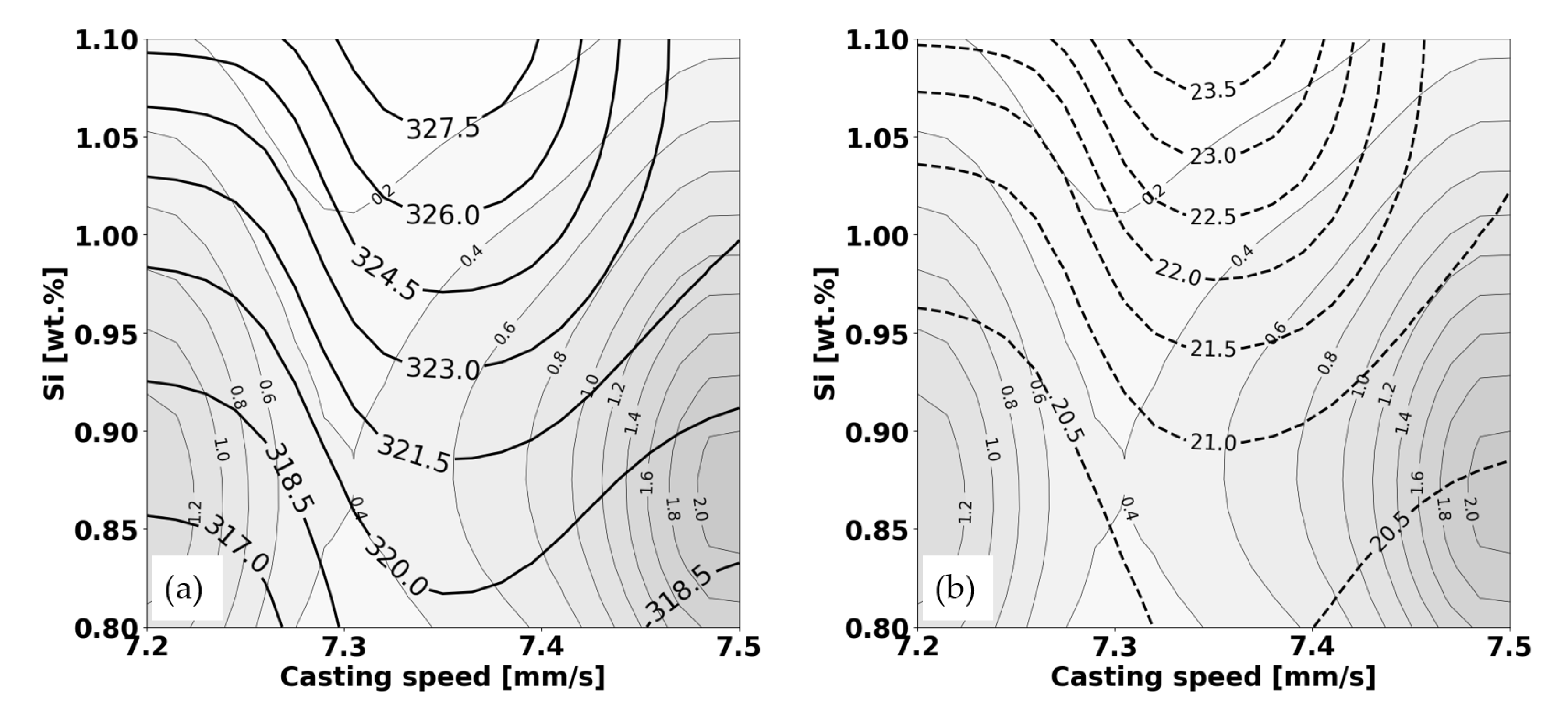

3.2. Illustration of Explanations for Various Instances of Graphical Displays of Results for Hot Extrusion of AA 6082

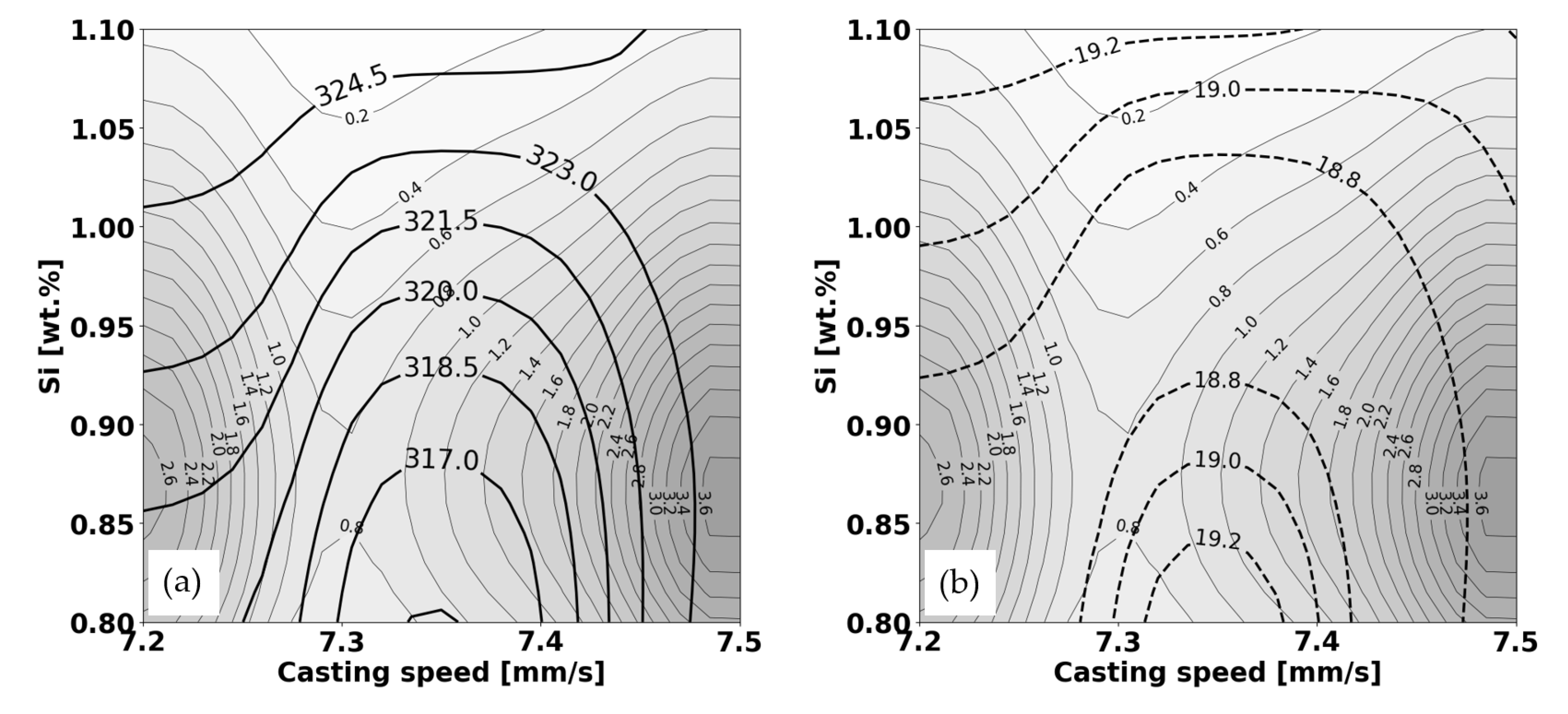

- Elongation: The predicted elongation at this point is approximately 11.95. This is the expected outcome of the elongation test given these specific conditions of casting speed and Si content.

- Standard Deviation: The standard deviation associated with this prediction is not directly quoted, but it can be inferred from the provided text files that it would likely be a value close to the nearby standard deviation values. A lower standard deviation would indicate that the predicted elongation value of 11.95 is more reliable.

- Data Density: The data density at this point is 0.80 This value indicates the number of data points or the amount of information from the experiments or simulations that contributed to the prediction at this specific point. A higher data density usually means that the prediction is based on more information and could be considered more reliable.

- Increasing Casting Speed (Si constant at 0.9 wt.%): At a constant silicon content of 0.9 wt.%, as the casting speed increases from 7.4 mm/s to the right, the solid lines representing elongation curve upwards. This means that elongation increases with casting speed in that range. Therefore, if you increase the casting speed while maintaining the Si content at 0.9 wt.%, the prediction for elongation will be higher.

- Increasing Si Content (Casting Speed constant at 7.4 mm/s): When the casting speed is held constant at 7.4 mm/s, and we look at increasing Si content vertically on the graph, the solid isolines for elongation dip downward as we move up, which indicates that elongation decreases as the Si content increases at this casting speed.

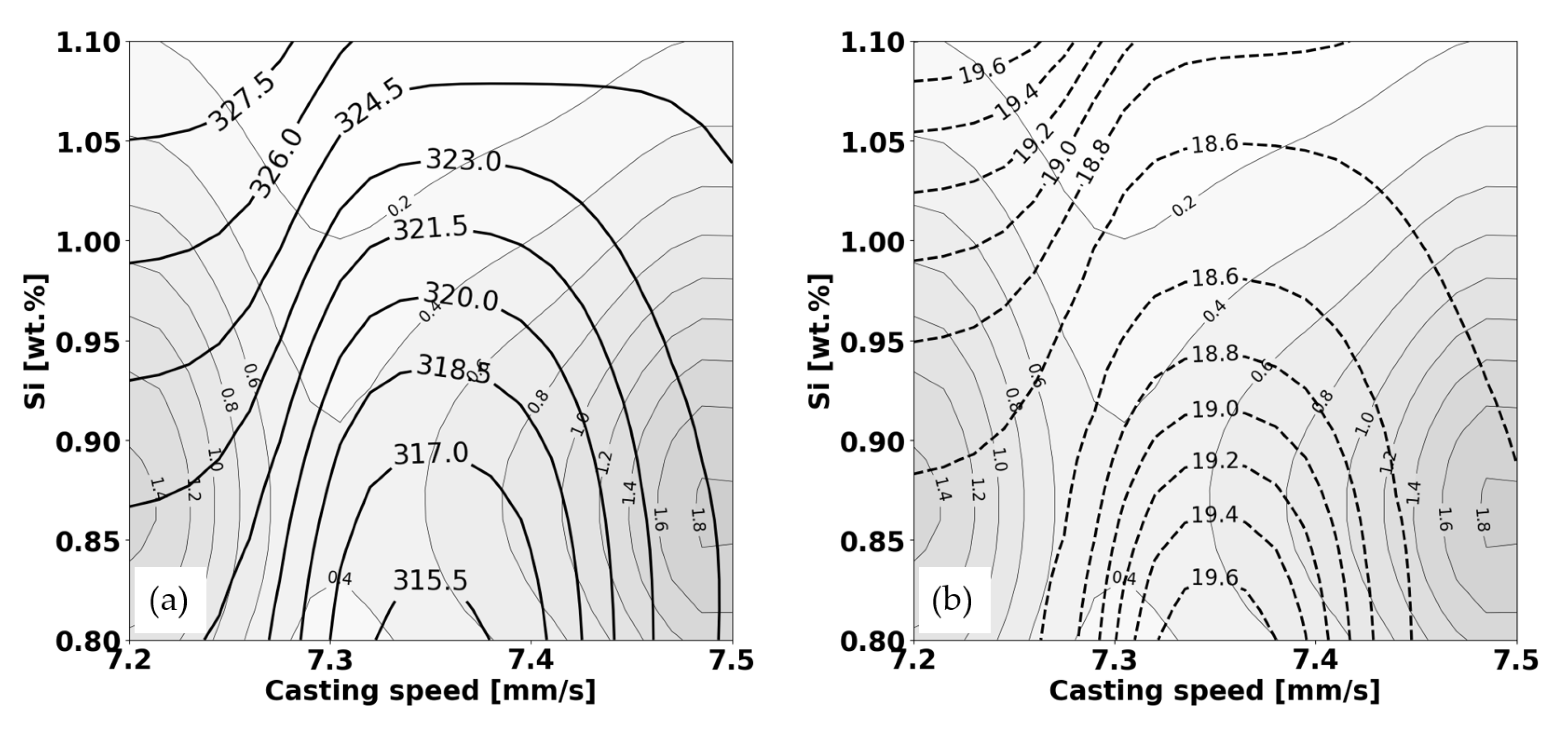

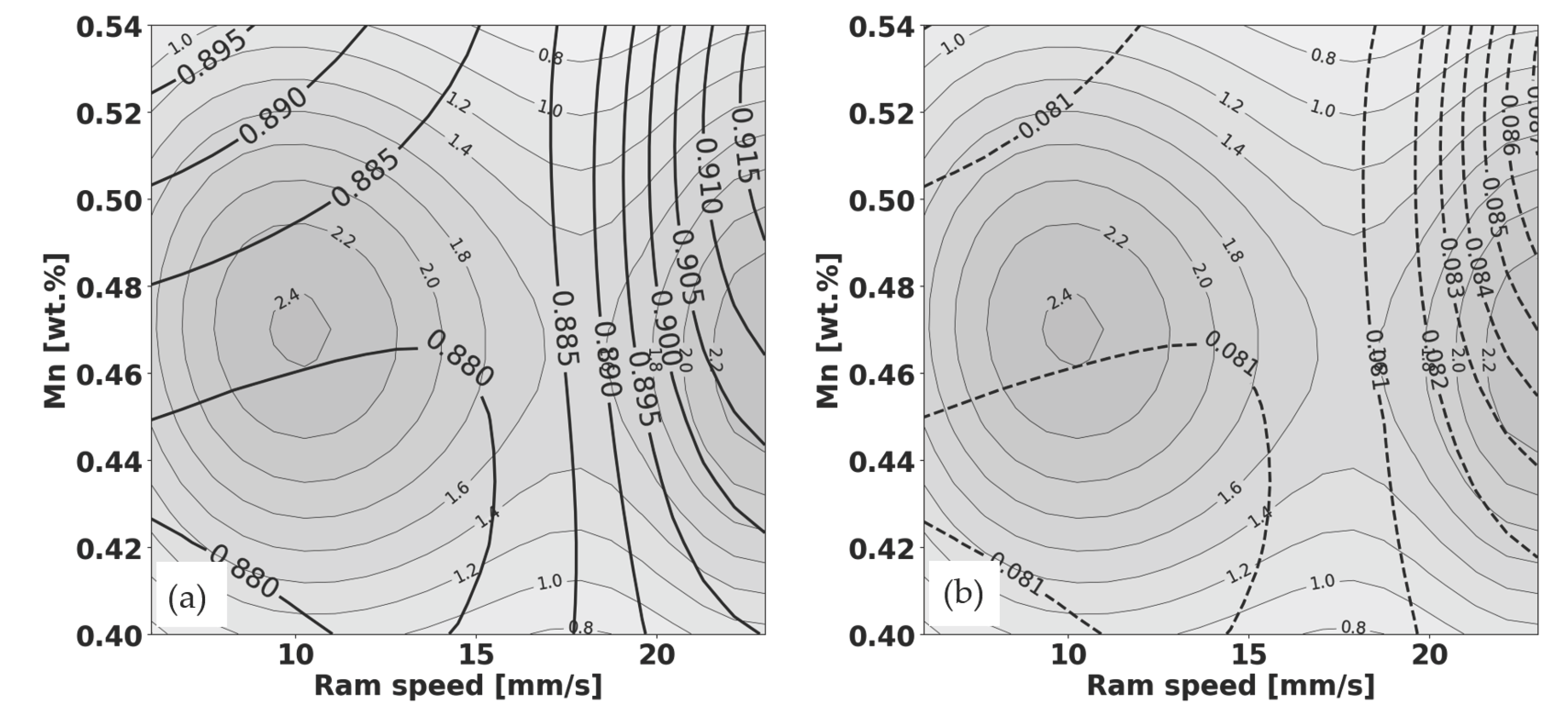

- High yield strength (higher values on the graph),

- Lower standard deviation (indicating consistency in the data),

- Acceptable levels of elongation (based on the previous elongation graph), and

- High data density (darker areas on the graphs).

4. Discussion

- A tiny fraction of knowledge from the existing global knowledge repository (for example, comments on likely microstructural level causes for predicted results) has already been included in the explanation, as ChatGPT has information from many publicly available scientific and other sources. The authors argue that in order to provide a more objective interpretation of the (CAE) ANN predictions, a language that is otherwise “less beautiful” and stricter, specialized interpretation software with fewer linguistic masks will need to be developed.

- The incorporation of all available knowledge is intended, with deliberate gathering, verification, and then integration of specific knowledge from the field under consideration. Such an example would be, e.g., supplementing the automatic explanation with complex chemical reactions and/or mechanical microstructural phenomena as seen through the eyes of a human expert with many years of experience and knowledge, as explicitly stated in Section 2.1 when explaining the effect of important phenomena during hot extrusion of AA 6082.

- An explanation tailored to various needs and knowledge levels should be possible with the development of an application, or specific parts of an application, in connection with ChatGPT (or other large language models). These applications will likely be closed and intended for a specific public (engineers, researchers, students) at different quality levels. Because the explanation’s language will be more objective, there will be a far lower possibility of automatic (machine) explanations being misunderstood. Additionally, if needed, this will guarantee the confidentiality of certain knowledge, which is a business secret.

5. Conclusions

- A general concept is proposed to explain the observed phenomena in metallic materials. The proposed framework aims to mimic the traditional scientific approach, which is based on mathematical representations of the considered physical phenomena.

- The proposed framework is applied to the example of hot extrusion of AA 6082, where CAE is used as an artificial neural network to model the phenomenon and predict its key parameters.

- ChatGPT as one of the publicly accessible tools of large language models is used to explain/interpret the CAE ANN predicted results according to the proposed framework.

- The obtained results are discussed, and some recommendations for improving the proposed framework are made.

- The basic idea is to enable researchers and practicing engineers to better understand the considered physical phenomena and results, provided by empirical models made with ANNs.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The values wmin = 0.15 and wmax = 0.25 were used in the analyzes in this article. |

References

- Peruš, I.; Kugler, G.; Malej, S.; Terčelj, M. Contour Maps for Simultaneous Increase in Yield Strength and Elongation of Hot Extruded Aluminum Alloy 6082. Metals 2022, 12, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Sha, W. Modelling the correlation between processing parameters and properties of maraging steels using artificial neural network. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2004, 29, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terčelj, M.; Fazarinc, M.; Kugler, G.; Peruš, I. Influence of the chemical composition and process parameters on the mechanical properties of an extruded aluminium alloy for highly loaded structural parts. Constr Build Mater. 2013, 44, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, C.; Garcia, M.-C.; Caballero, F.G.; Garcıa de Andres, C. Neural network analysis of the influence of processing on strength and ductility of automotive low carbon sheet steels. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2006, 38, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Večko, P.-T.; Peruš, I.; Kugler, G.; Terčelj, M. Towards improved reliability of the analysis of factors influencing the properties on steel in industrial practice. ISIJ International 2009, 49(3), 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Huang, J.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Wei, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Lai, Z.; Qu, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. Explanatory Machine Learning Accelerates the Design of Graphene-Reinforced Aluminium Matrix Composites with Superior Performance. Metals 2023, 13, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberreiter, M.; Fladischer, S.; Stoschka, M.; Leitner, M. A Probabilistic Fatigue Strength Assessment in AlSi-Cast Material by a Layer-Based Approach. Metals 2022, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Najm, S.M.; Oleksik, V.; Vasilca, D.; Paniti, I.; Szpunar, M. Recent Developments and Future Challenges in Incremental Sheet Forming of Aluminium and Aluminium Alloy Sheets. Metals 2022, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiciak-Pikuła, M.; Felusiak-Czyryca, A.; Twardowski, P. Tool Wear Prediction Based on Artificial Neural Network during Aluminum Matrix Composite Milling. Sensors 2020, 20, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Z. A Modified Back Propagation Artificial Neural Network Model Based on Genetic Algorithm to Predict the Flow Behavior of 5754 Aluminum Alloy. Materials 2018, 11, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Younis, H.B.; Mansoor, M.; Moosavi, S.K.R.; Khan, N.M.; Akhtar, N. Training Deep Neural Networks with Novel Metaheuristic Algorithms for Fatigue Crack Growth Prediction in Aluminum Aircraft Alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharath, B.N.; Venkatesh, C.V.; Afzal, A.; Aslfattahi, N.; Aabid, A.; Baig, M.; Saleh, B. Multi Ceramic Particles Inclusion in the Aluminium Matrix and Wear Characterization through Experimental and Response Surface-Artificial Neural Networks. Materials 2021, 14, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merayo, D.; Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M. Prediction of Mechanical Properties by Artificial Neural Networks to Characterize the Plastic Behavior of Aluminum Alloys. Materials 2020, 13, 5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Najm, S.M.; Ibrahim, O.M.; Kowalik, M. Analysis of the Frictional Performance of AW-5251 Aluminium Alloy Sheets Using the Random Forest Machine Learning Algorithm and Multilayer Perceptron. Materials 2023, 16, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosarac, A.; Mladjenovic, C.; Zeljkovic, M.; Tabakovic, S.; Knezev, M. Neural-Network-Based Approaches for Optimization of Machining Parameters Using Small Dataset. Materials 2022, 15, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stręk, A.M.; Dudzik, M.; Machniewicz, T. Specifications for Modelling of the Phenomenon of Compression of Closed-Cell Aluminium Foams with Neural Networks. Materials 2022, 15, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Martinez, M.; Alfaro-Ponce, M.; Muñoz-Ibañez, C. Design of an Aluminum Alloy Using a Neural Network-Based Model. Metals 2022, 12, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Kubit, A.; Dzierwa, A.; Krasowski, B.; Jurczak, W. Surface Finish Analysis in Single Point Incremental Sheet Forming of Rib-Stiffened 2024-T3 and 7075-T6 Alclad Aluminium Alloy Panels. Materials 2021, 14, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, W.; Bhandari, K.S.; Jung, D.W.; Chen, X. Flow Behavior of AA5005 Alloy at High Temperature and Low Strain Rate Based on Arrhenius-Type Equation and Back Propagation Artificial Neural Network (BP-ANN) Model. Materials 2022, 15, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, S.M.; Paniti, I.; Trzepieciński, T.; Nama, S.A.; Viharos, Z.J.; Jacso, A. Parametric Effects of Single Point Incremental Forming on Hardness of AA1100 Aluminium Alloy Sheets. Materials 2021, 14, 7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, S.; Kodandappa, R.; Ansari, K.; Kuruniyan, M.S.; Afzal, A.; Kaladgi, A.R.; Aslfattahi, N.; Saleel, C.A.; Gowda, A.C.; Bindiganavile Anand, P. Influence of Heat Treatment and Reinforcements on Tensile Characteristics of Aluminium AA 5083/Silicon Carbide/Fly Ash Composites. Materials 2021, 14, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Miao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Xie, Y. Prediction of Mechanical Properties and Optimization of Friction Stir Welded 2195 Aluminum Alloy Based on BP Neural Network. Metals 2023, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Liu, G. Inverse Identification of Residual Stress Distribution in Aluminium Alloy Components Based on Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabec, I. ; Sachse,W. Synergetics of Measurement, Prediction and Control; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peruš, I.; Poljansek, K.; Fajfar, P. Flexural deformation capacity of rectangular RC columns determined by the CAE method.

- Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn.2006, 35(12), 1453–1470. 12.

- Specht, D.F. A general regression neural network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1991, 2, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (version 3.5) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat.

- Mrówka, N.G.; Sieniawski, J.; Wierzbińska, M. Intermetallic phase particles in 6082 aluminium alloy. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2007, 28, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.L.; Kang, S.B.; Kim, H.W. The complex microstructures in as-cast Al-Mg-Si alloy. Mater. Lett. 1999, 41, 167–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrówka, N.G.; Sieniawski, J. Influence of heat treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 6005 and 6082 aluminium alloys. J. Mater. Proc. Technol. 2005, 163, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrówka, N.G.; Sieniawski, J. Effect of heat treatment on tensile and fracture toughness properties of 6082 alloy. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2009, 32, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Peruš, I.; Fajfar, P. Ground-motion prediction by a non-parametric approach. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 39, 1395–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, L.; Taly, A. The explanation game: Explaining machine learning models using shapley values. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction: 4th IFIP TC 5, TC 12, WG 8.4, WG 8.9, WG 12.9 International Cross-Domain Conference, CD-MAKE 2020, Dublin, Ireland, 25–28, May 2020. [Proceedings 4 (pp. 17-38). Springer International Publishing].

- Qayyum, F.; Khan, M.A.; Kim, D.-H.; Ko, H.; Ryu, G.-A. Explainable AI for Material Property Prediction Based on Energy Cloud: A Shapley-Driven Approach. Materials 2023, 16, 7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Jena, R.; Talukdar, D.; Mohanty, M.; Sahu, B.K.; Raul, A.K.; Abdul Maulud, K.N. A New Method to Evaluate Gold Mineralisation-Potential Mapping Using Deep Learning and an Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Reich, C. A Systematic Literature Review on Artificial Intelligence and Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Visual Quality Assurance in Manufacturing. Electronics 2023, 12, 4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).