Submitted:

15 March 2024

Posted:

18 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

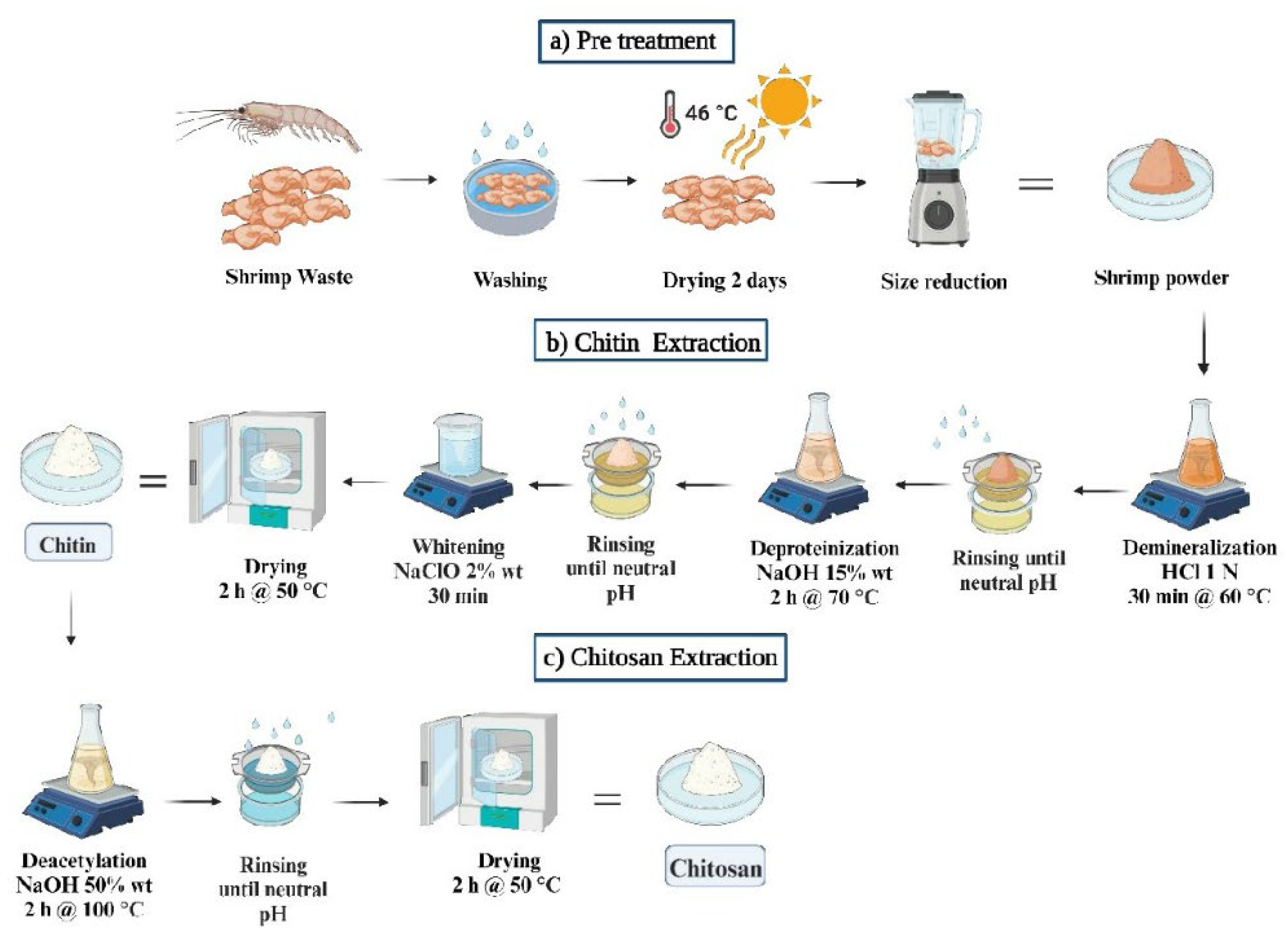

2.1. Obtaining and Processing Farfatepenaeus Californiensis Shells

2.2. Extraction of Chitin and Chitosan

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan

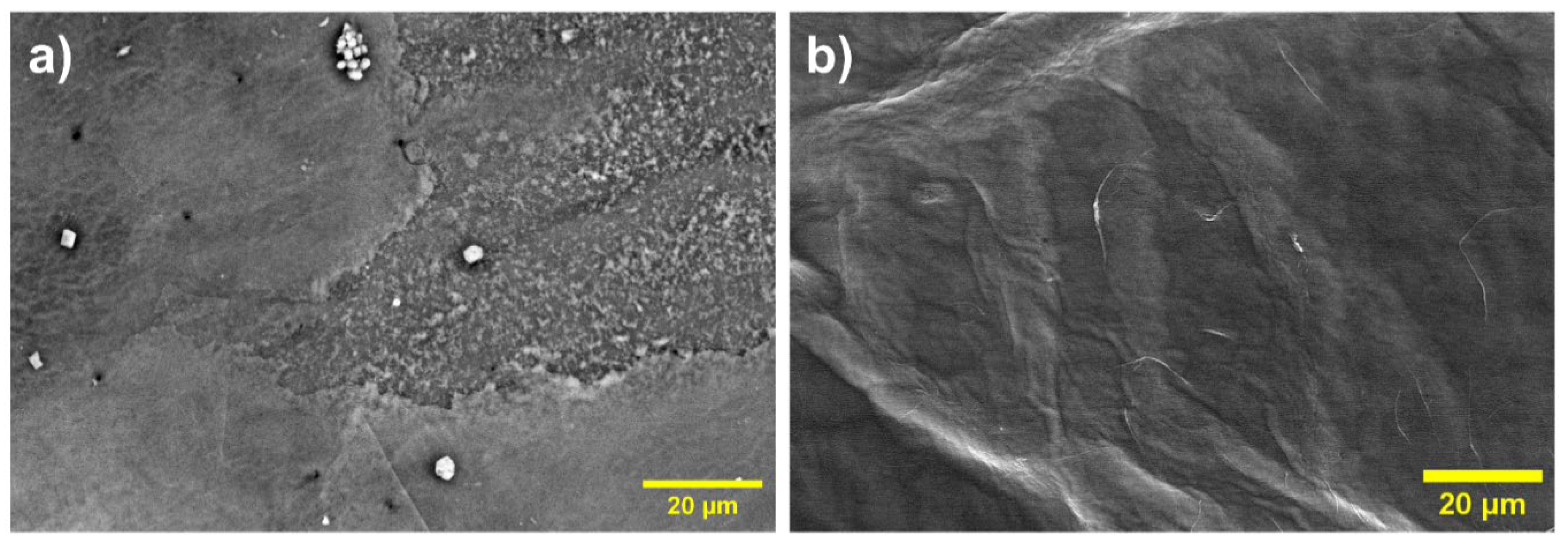

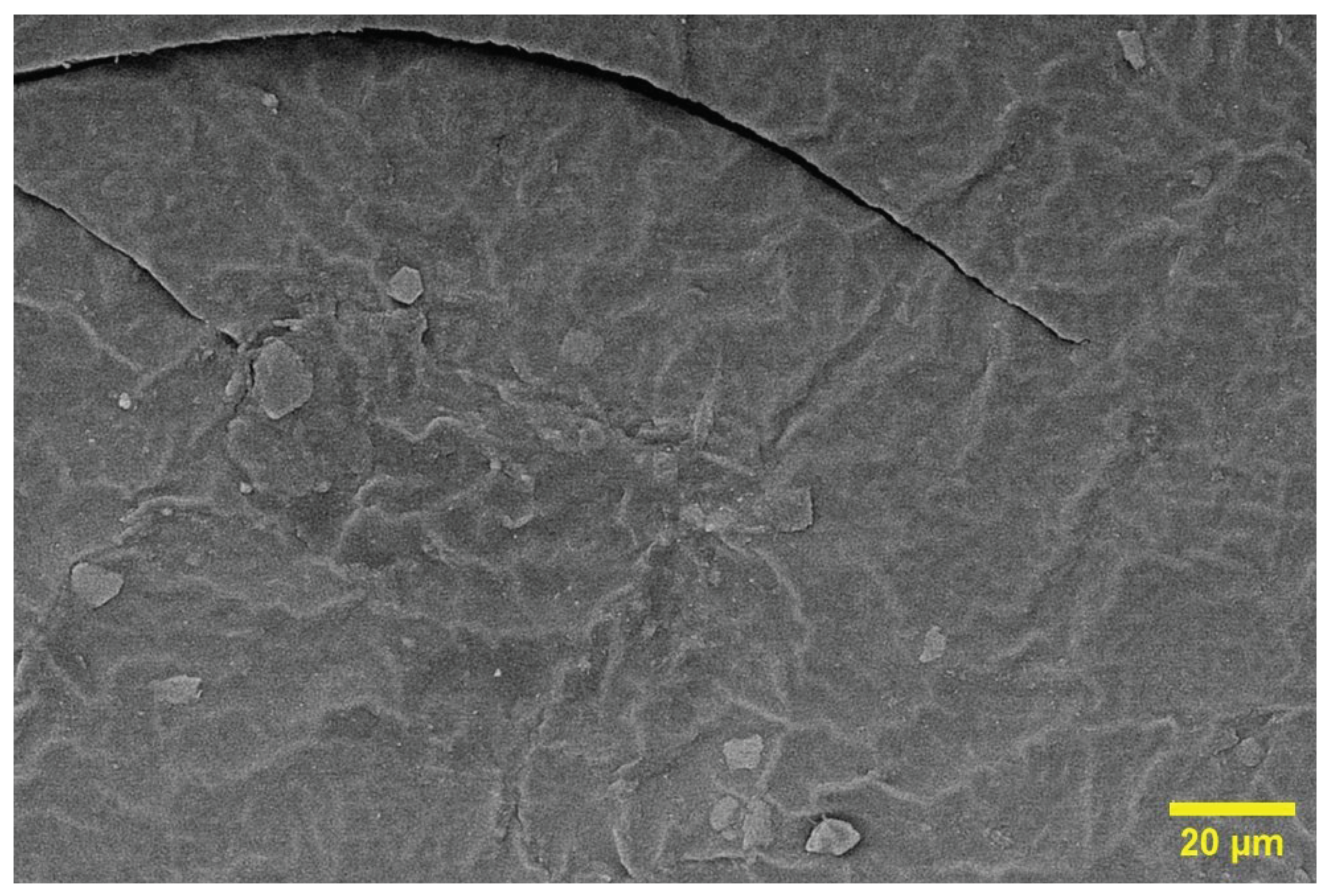

2.3.1. Morphological and Elemental Analysis

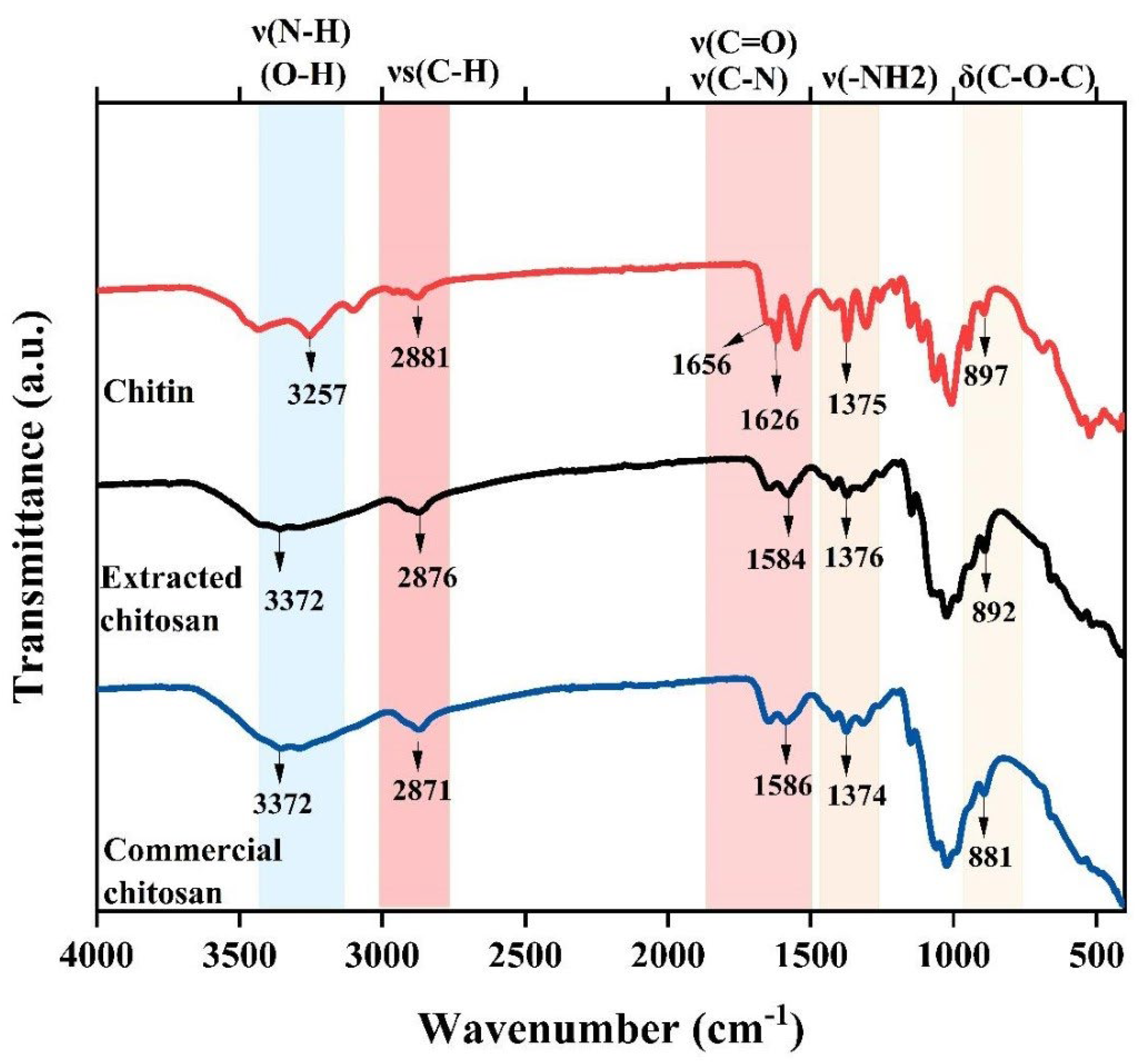

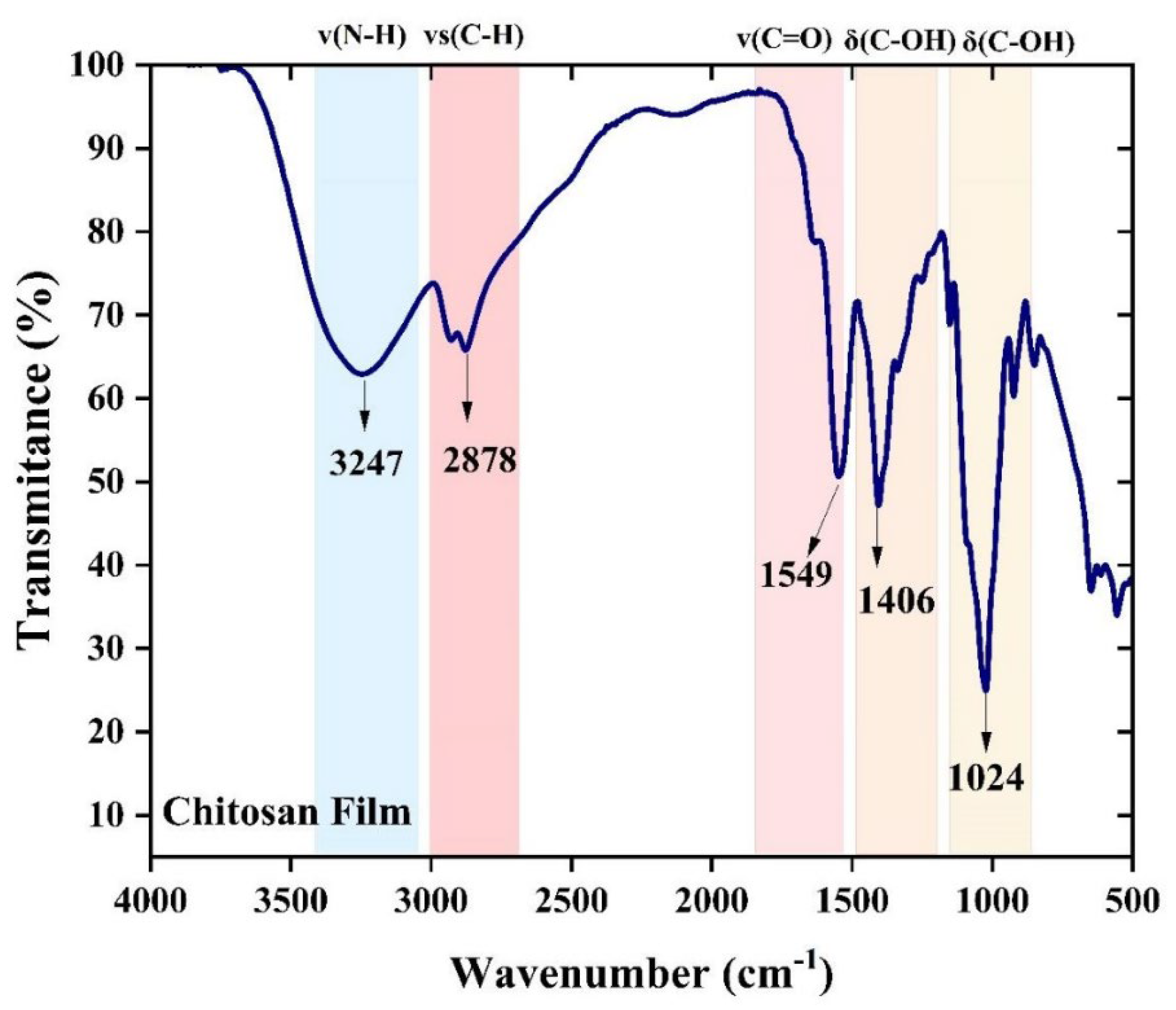

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.3. Ash Content

2.3.4. Total Yield

2.3.5. Deacetylation Degree

2.3.6. Degree of N-acetylation

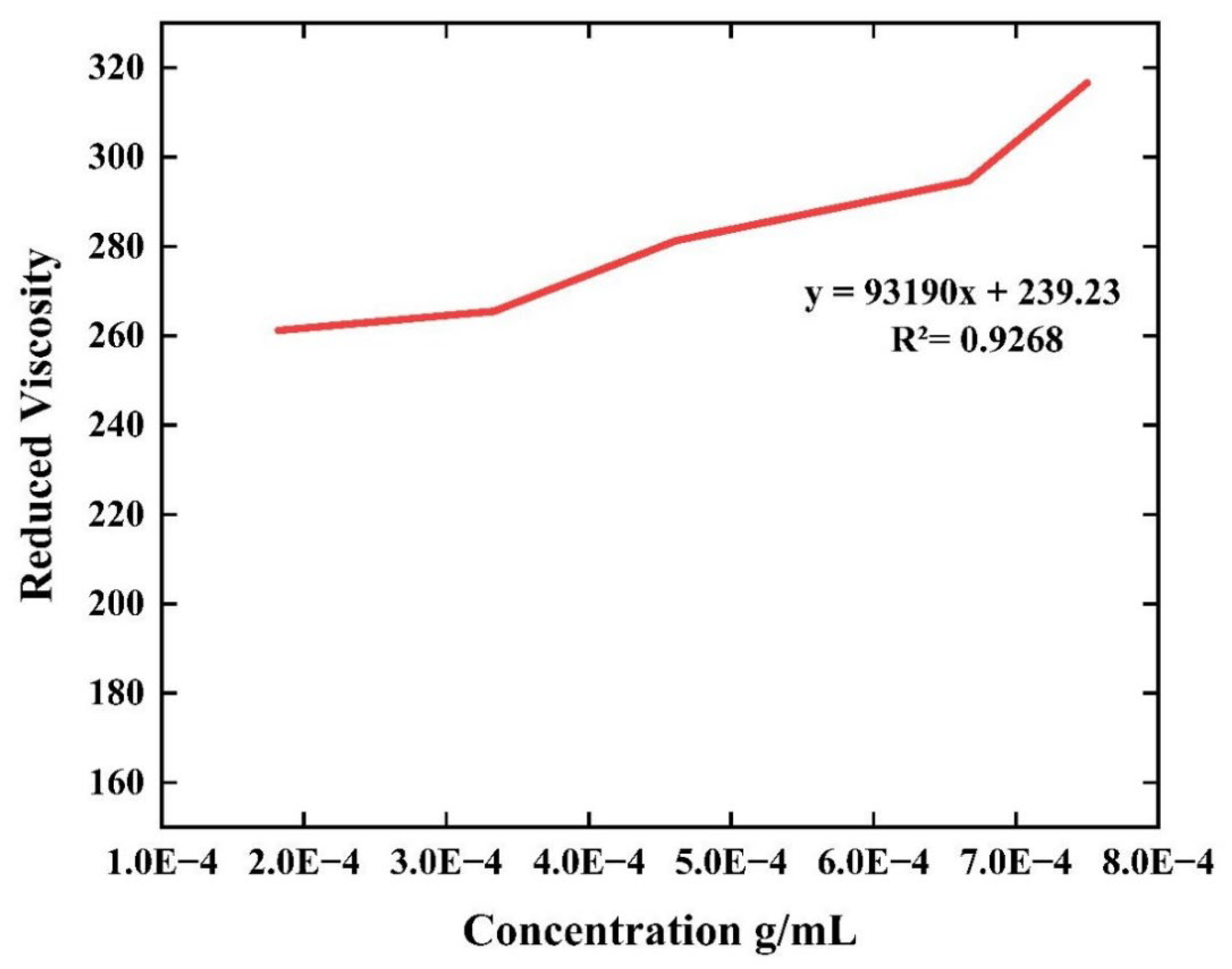

2.3.7. Molecular Weight of the Biopolymers

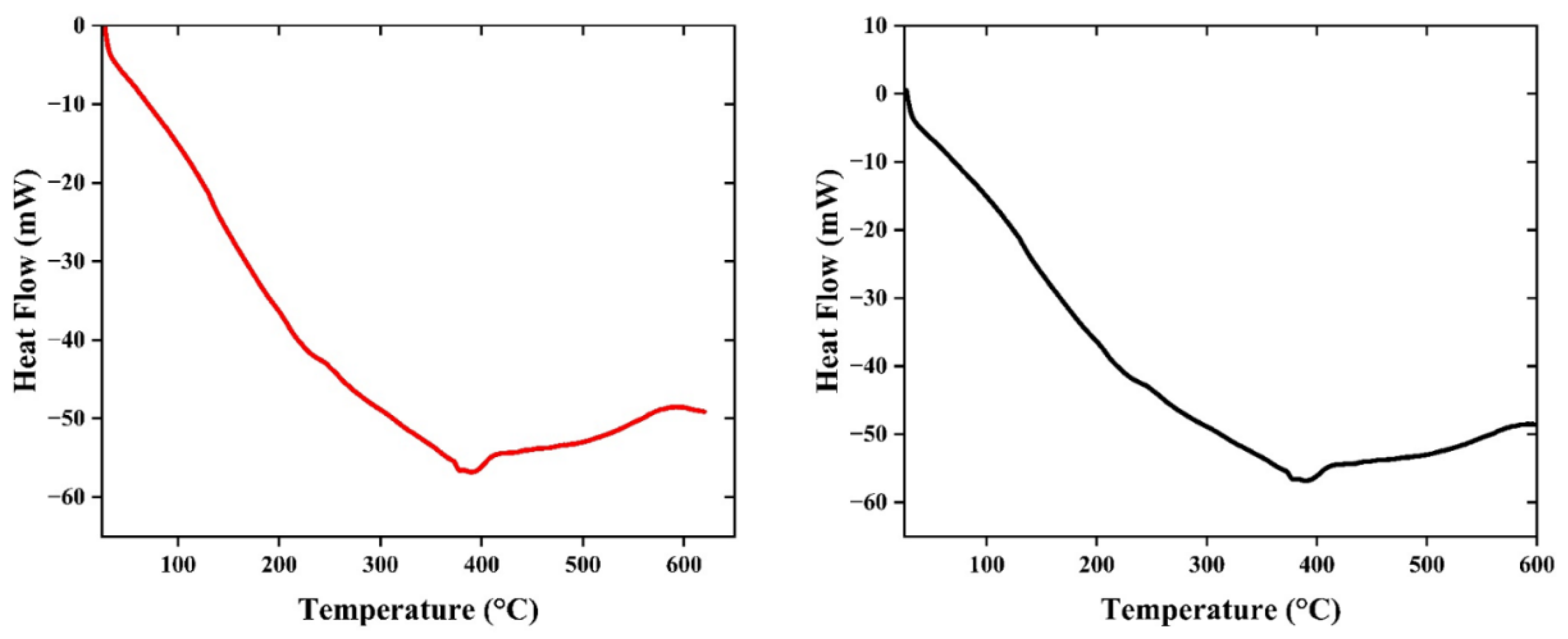

2.3.8. Thermal Analysis (DSC)

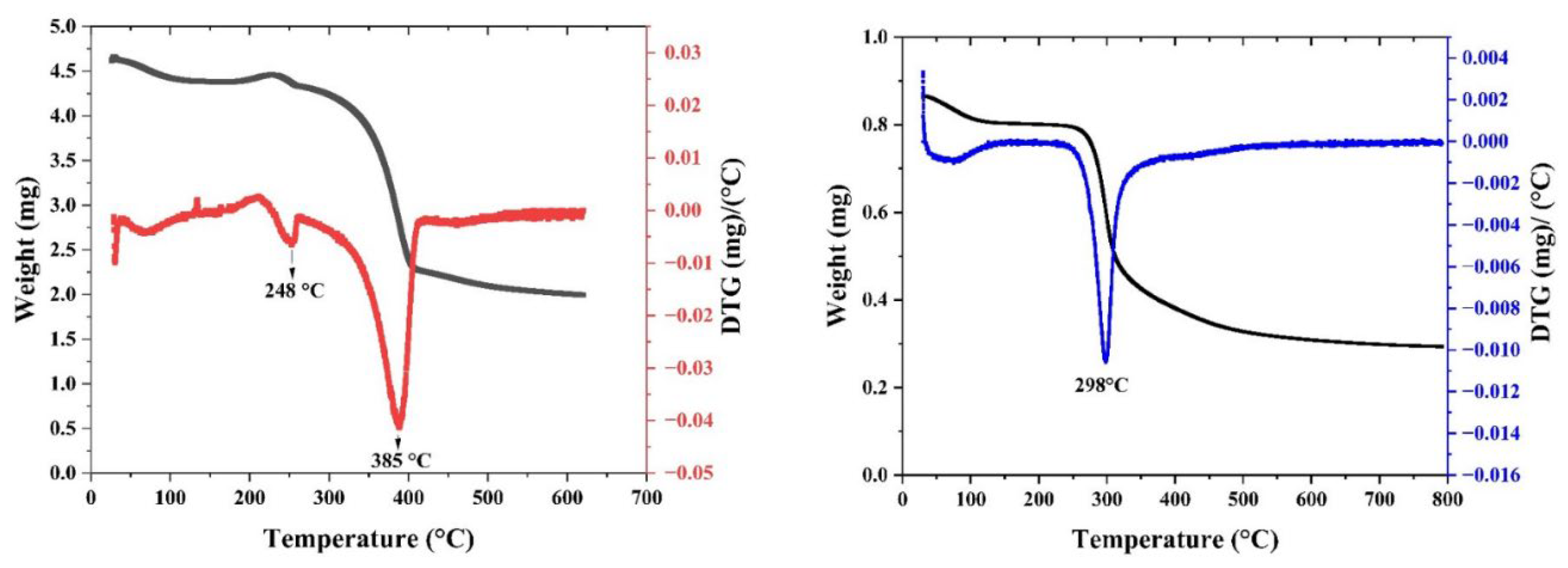

2.3.9. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

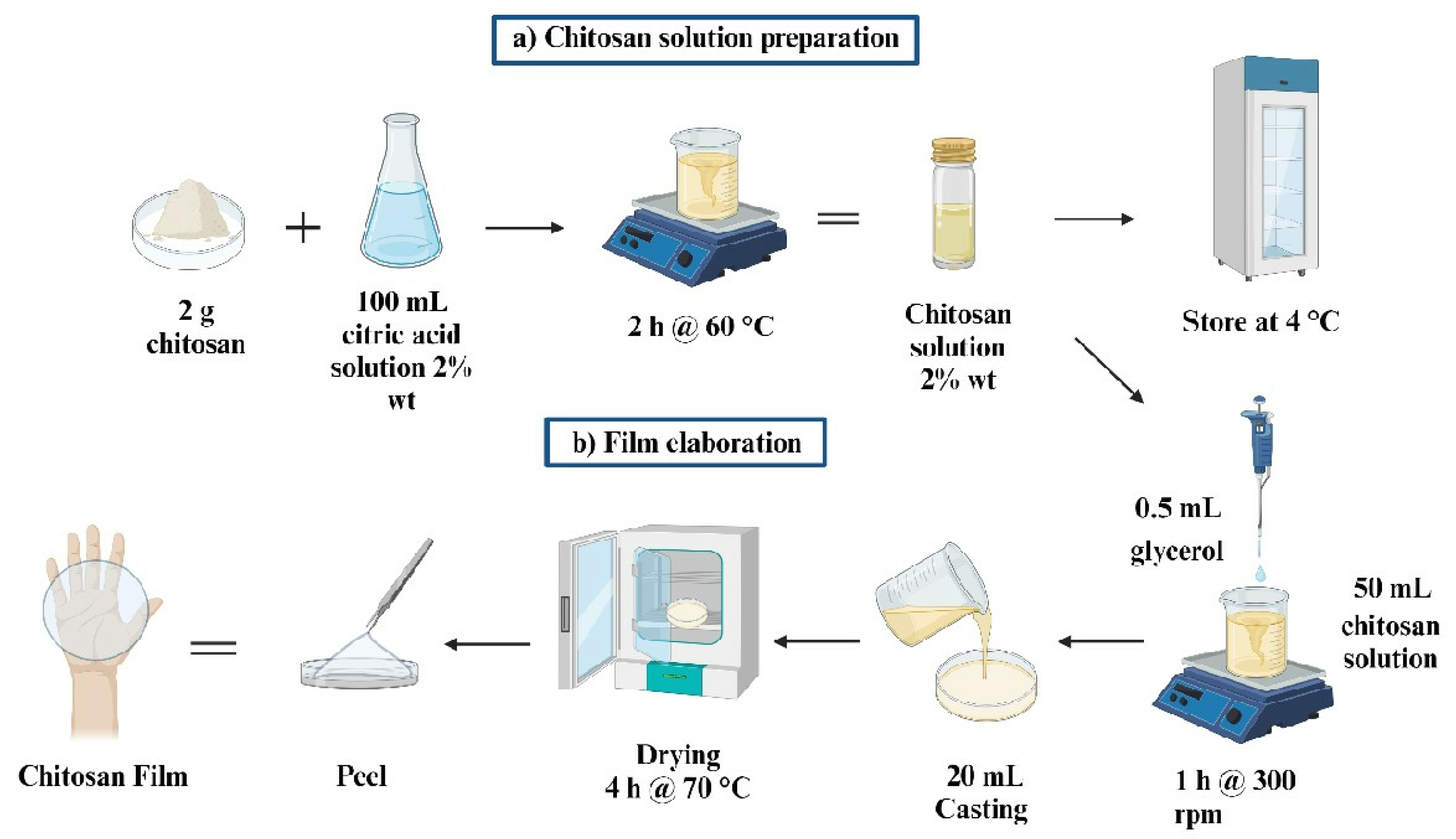

2.4. Preparation for Antibacterial Packaging

2.5. Active Packaging Characterization

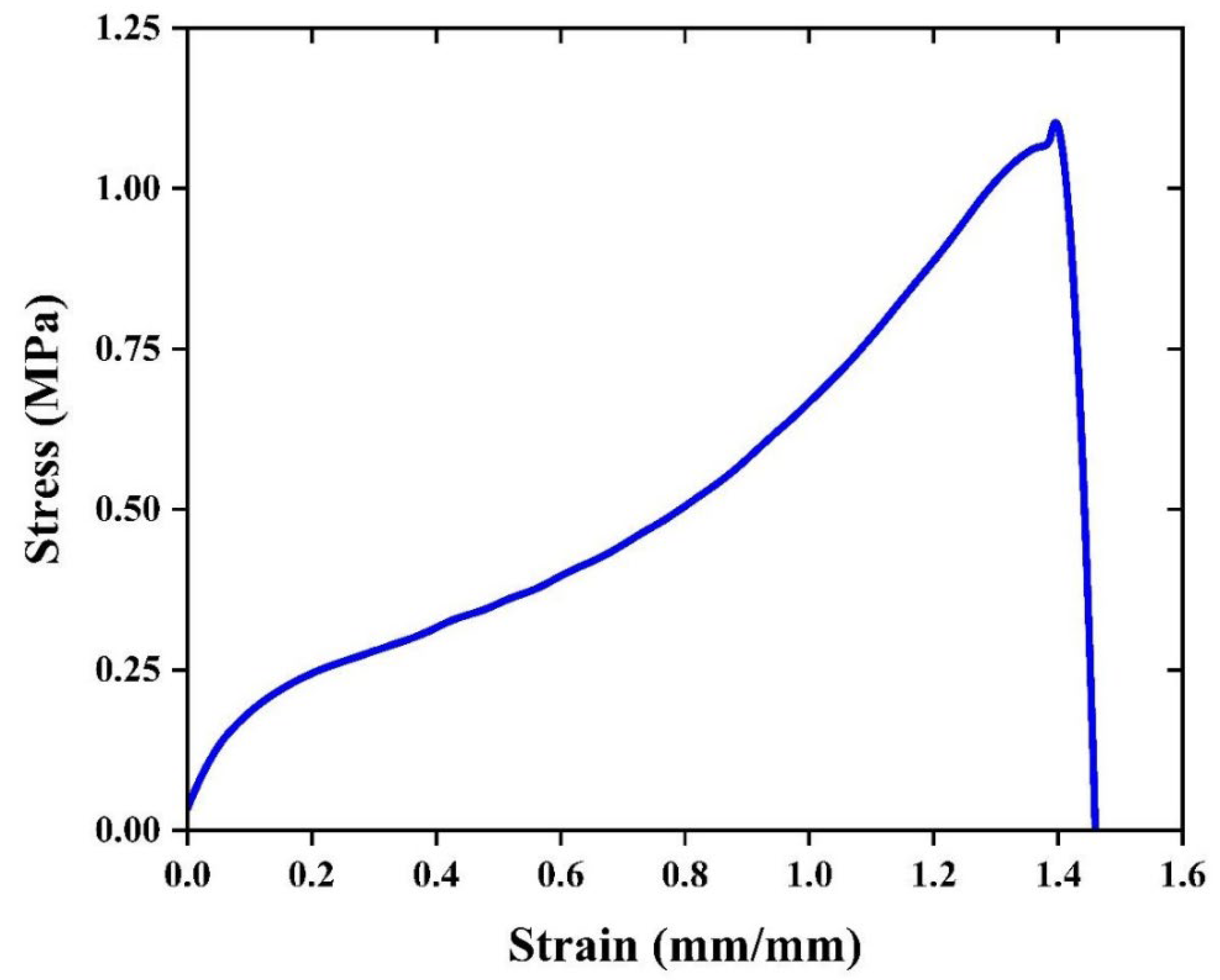

2.5.1. Mechanical Testing

2.5.2. Percentage of Moisture Content, Degree of Swelling and Solubility

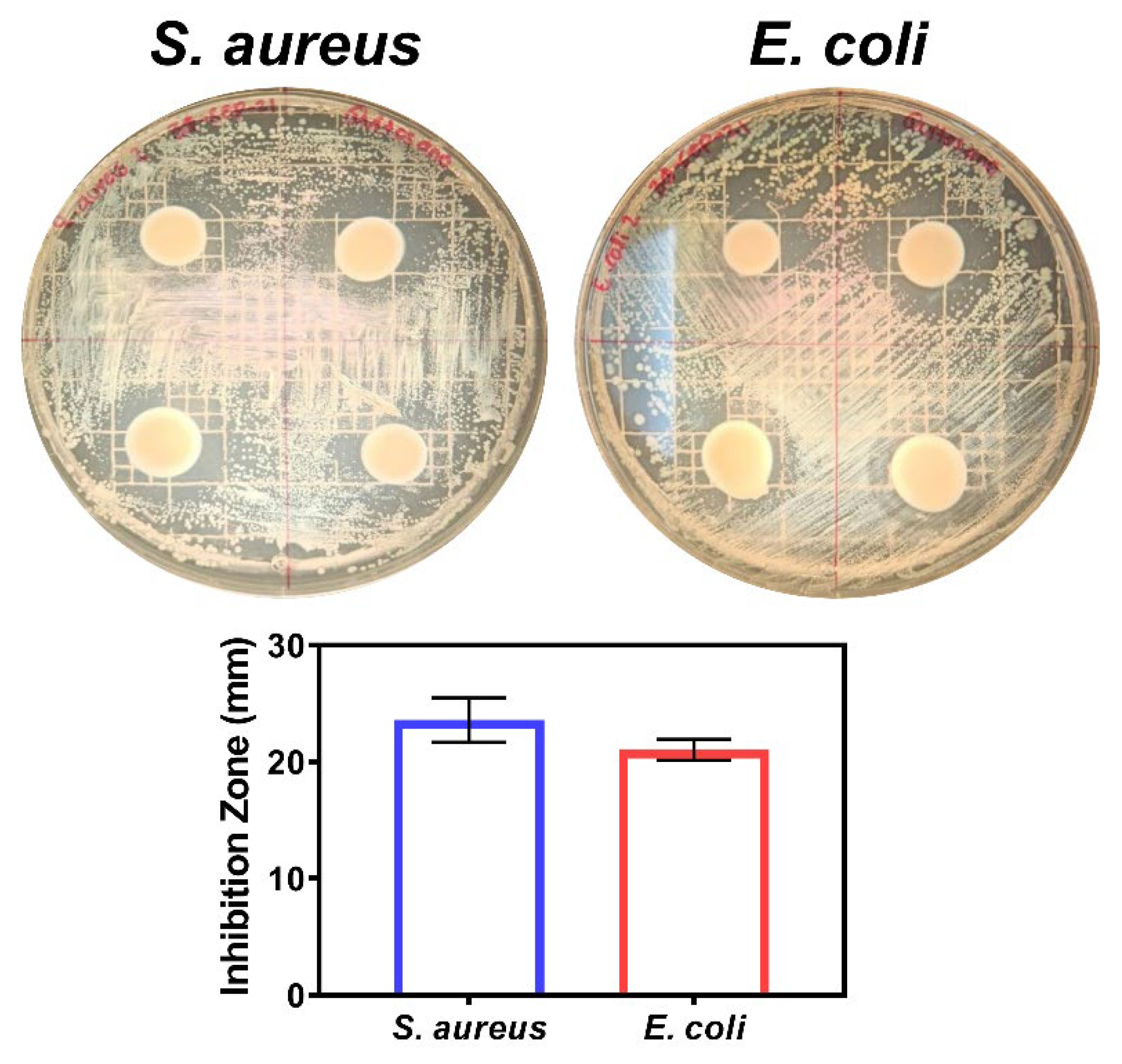

2.5.3. Antimicrobial Activity

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chitin and Chitosan Extraction

| Material | Intrinsic viscosity [η] (dL/g) |

Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Farfantepenaeus californiensis extracted chitosan | 239.23 | 1.26 x 105 |

| Commercial chitosan | 242.54 | 1.28 x 105 |

| Film | TS (Mpa) | EAB (%) | Young’s Modulus (Mpa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan Film | 1.10±0.32 | 186.31±90.33 | 1.565±0.45 |

3.2. Food Active Packaging

3.3. Chemical and Thermal Properties of the Film

4. Conclusions

- The extraction purity demonstrated that F. californiensis is a potential source for obtaining high-quality chitin and chitosan. Our method yields an ideal low molecular weight natural polymer for the packaging industry.

- The application of the extracted chitosan by the casting method proved to be an effective strategy for creating active packaging films, showing antibacterial action against common enteric infection agents.

- The mechanical properties of the film are not as efficient as synthetic polymeric films, but it can be increased adding other additives o making blends with other biopolymers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castelló, M. E., Anbinder, P. S., Amalvy, J. I., & Peruzzo, P. J. Production and characterization of chitosan and glycerol-chitosan films. MRS Advances, 2018; 3(61), 3601–3610. [CrossRef]

- Luo, A., Hu, B., Feng, J., Lv, J., & Xie, S. Preparation, and physicochemical and biological evaluation of chitosan- Arthrospira platensis polysaccharide active films for food packaging. Journal of Food Science, 2021; 86(3), 987–995. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K., Xiao, S., Li, W., Wang, W., Chen, H., Yang, F., & Qin, C. Chitosan-acorn starch-eugenol edible film: Physico-chemical, barrier, antimicrobial, antioxidant and structural properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019; 135, 344–352. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Qian, J., & Ding, F. Emerging Chitosan-Based Films for Food Packaging Applications. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2018; 66(2), 395–413. [CrossRef]

- Pakizeh, M., Moradi, A., & Ghassemi, T. (2021). Chemical extraction and modification of chitin and chitosan from shrimp shells. European Polymer Journal, 2021 ; 159, 110709. [CrossRef]

- Muzzarelli, R. A. A. Chitin. 1st ed.; Pergamon Press: United Kingdom. 1977; pp. 1-2.

- Ahmed, Shakeel, and Saiqa Ikram, eds. Chitosan: derivatives, composites and applications. John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

- Vidal, J. L., Jin, T., Lam, E., Kerton, F., & Moores, A. Blue is the new green: Valorization of crustacean waste. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 2022; 5, 100330. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Robinson, K.G. Martinez-Inzunza, A, Rochin-Wong, S. Rodríguez Córdova, R. J., Vasquez-Garcia, S. R., & Fernández-Quiroz. Physicochemical study of chitin and chitosan obtained from California brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus californiensis) exoskeleton. Biotecnia, 24(2), 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Figueroa, J. L. El cultivo de camarón en México, actualidades y perspectivas. Contactos. 2002. 43, 41-54 https://cesasin.mx/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Cam-Actualidades-en-el-cultivo-de-camaro%CC%81n.pdf.

- Lopez y Galvez, M. D., Zazueta-Solano, R., Guillen-Pompa M., Plan maestro de camaron de altamar del estado de sinaloa. 1st ed.; SAGARPA-CONAPESCA: Mexico, 2009; pp. 7.

- Ruiz-Luna, A., Meraz-Sánchez, R., & Madrid-Vera, J. Abundance distribution patterns of commercial shrimp off northwestern Mexico modeled with geographic information systems. Ciencias Marinas, 2010, 36(2). [CrossRef]

- INAPESCA. (n.d.). Diario Oficial de la Federacion, Carta Nacional Acuicola. Gobierno de Mexico. https://www.gob.mx/inapesca/acciones-y-programas/carta-nacional-acuicola.

- Darzi Arbabi, H., Motamedzadegan, A., Pirdashti, Mohsen, Shahrokhi, B., & Arzideh, S. M. Extraction and Physicochemical Characterization of Chitosan from Litopenaeus vannamei Shells. Iranian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering (IJCCE), 2022, Online First. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A., Singh, A., Aluko, R. E., & Benjakul, S. Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) shell chitosan and the conjugate with epigallocatechin gallate: Antioxidative and antimicrobial activities. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 2021 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q., Qiu, W., Feng, Y., Jin, Y., Deng, S., Tao, N., & Jin, Y. Proteases and microwave treatment on the quality of chitin and chitosan produced from white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). eFood, 2023, 4(2), e73. [CrossRef]

- Vilar Junior, J. C., Ribeaux, D. R., Alves Da Silva, C. A., & De Campos-Takaki, G. M. Physicochemical and Antibacterial Properties of Chitosan Extracted from Waste Shrimp Shells. International Journal of Microbiology, 2016, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, H., Kanayairam, V., & Ravichandran, R. Chitin and chitosan preparation from shrimp shells Penaeus monodon and its human ovarian cancer cell line, PA-1. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 107, 662–667. [CrossRef]

- Leo Edward, M., Dharanibalaji, K. C., Kumar, K. T., Chandrabose, A. R. S., Shanmugharaj, A. M., & Jaisankar, V. Preparation and characterisation of chitosan extracted from shrimp shell (Penaeus monodon) and chitosan-based blended solid polymer electrolyte for lithium-ion batteries. Polymer Bulletin, 2022, 79(1), 587–604. [CrossRef]

- Charoenvuttitham, P., Shi, J., & Mittal, G. S. Chitin Extraction from Black Tiger Shrimp (Penaeus monodon) Waste using Organic Acids. Separation Science and Technology, 2006, 41(6), 1135–1153. [CrossRef]

- Fatika, F. A. W., Anwar, M., Prasetyo, D. J., Rizal, W. A., Suryani, R., Yuliyanto, P., Hariyadi, S., Suwanto, A., Bahmid, N. A., Wahono, S. K., Sriherfyna, F. H., Poeloengasih, C. D., Purwono, B., Agustian, E., Maryana, R., & Hernawan, H. Facile fabrication of chitosan Schiff bases from giant tiger prawn shells (Penaeus monodon) via solvent-free mechanochemical grafting. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2023, 247, 125759. [CrossRef]

- Iber, B. T., Torsabo, D., Chik, C. E. N. C. E., Wahab, F., Abdullah, S. R. S., Hassan, H. A., & Kasan, N. A. The impact of re-ordering the conventional chemical steps on the production and characterization of natural chitosan from biowaste of Black Tiger Shrimp, Penaeus monodon. Journal of Sea Research, 2022, 190, 102306. [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, H., Licciardello, F., Fava, P., Siesler, H. W., & Pulvirenti, A. Recent advances on chitosan-based films for sustainable food packaging applications. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 2020,26, 100551. [CrossRef]

- Perera, K. Y., Jaiswal, A. K., & Jaiswal, S. Biopolymer-Based Sustainable Food Packaging Materials: Challenges, Solutions, and Applications. Foods, 2023, 12(12), 2422. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R., & Rhim, J.-W. Chitosan-based biodegradable functional films for food packaging applications. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2020, 62, 102346. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broek, L. A. M., Knoop, R. J. I., Kappen, F. H. J., & Boeriu, C. G. Chitosan films and blends for packaging material. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 116, 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Carvajal, K., Valdez-Salas, B., Beltrán-Partida, E., Salomón-Carlos, J., & Cheng, N. Chitosan, Gelatin, and Collagen Hydrogels for Bone Regeneration. Polymers, 2023, 15(13), 2762. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, R. M., Hrdina, R., Abdel-Mohsen, A. M., Fouda, M. M. G., Soliman, A. Y., Mohamed, F. K., Mohsin, K., & Pinto, T. D. Chitin and chitosan from Brazilian Atlantic Coast: Isolation, characterization and antibacterial activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2015, 80, 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Arrouze, F., Desbrieres, J., Rhazi, M., Essahli, M., & Tolaimate, A. Valorization of chitins extracted from North Morocco shrimps: Comparison of chitin reactivity and characteristics. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(30), 47804. [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Salas, B., Beltran-Partida, E., Cheng, N., Salvador-Carlos, J., Valdez-Salas, E. A., Curiel-Alvarez, M., & Ibarra-Wiley, R. Promotion of Surgical Masks Antimicrobial Activity by Disinfection and Impregnation with Disinfectant Silver Nanoparticles. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2021, Volume 16, 2689–2702. [CrossRef]

- AOAC Official Methods of analysis. 2000. USA: Maryland.

- Rasweefali, M. K., Sabu, S., Sunooj, K. V., Sasidharan, A., & Xavier, K. A. M. Consequences of chemical deacetylation on physicochemical, structural and functional characteristics of chitosan extracted from deep-sea mud shrimp. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications, 2021, 2, 100032. [CrossRef]

- Broussignac, P. A natural polymer not well known by the industry. Chem. Ind. Genie Chim., 1968, 1241–1247.

- Brugnerotto, J., Lizardi, J., Goycoolea, F. M., Argüelles-Monal, W., Desbrières, J., & Rinaudo, M. An infrared investigation in relation with chitin and chitosan characterization. Polymer, 2001 42(8), 3569–3580. [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.-T., Yang, J.-H., & Mau, J.-L. Physicochemical characterization of chitin and chitosan from crab shells. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2009, 75(1), 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Kasaai, M. R. Calculation of Mark–Houwink–Sakurada (MHS) equation viscometric constants for chitosan in any solvent–temperature system using experimental reported viscometric constants data. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2007, 68(3), 477–488. [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M., Milas, M., & Dung, P. L. Characterization of chitosan. Influence of ionic strength and degree of acetylation on chain expansion. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 1993, 15(5), 281–285. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D882-18 Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting (18). 2018. https://www.astm.org/d0882-18.html.

- Homez-Jara, A., Daza, L. D., Aguirre, D. M., Muñoz, J. A., Solanilla, J. F., & Váquiro, H. A. Characterization of chitosan edible films obtained with various polymer concentrations and drying temperatures. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 113, 1233–1240. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Partida, E., Valdez-Salas, B., Escamilla, A., Moreno-Ulloa, A., Burtseva, L., Valdez-Salas, E., Curiel Alvarez, M., & Nedev, N. (2015). The Promotion of Antibacterial Effects of Ti6Al4V Alloy Modified with TiO 2 Nanotubes Using a Superoxidized Solution. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2015, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Martinez, T., Valdez-Salas, B., Salvador-Carlos, J., Stoytcheva, M., Zlatev, R., & Beltrán-Partida, E. (2023). Improvement of the antibacterial and skin-protective performance of alcohol-based sanitizers using hydroglycolic phytocompounds. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 2023, 37(1), 2253927. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S. M., Krishnamoorthy, S., Paranthaman, R., Moses, J. A., & Anandharamakrishnan, C. A review on source-specific chemistry, functionality, and applications of chitin and chitosan. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications, 2021, 2, 100036. [CrossRef]

- Jollès, P., & Muzzarelli, R. A. A. Chitin and Chitinases, 1st ed.; Birkhäuser Verlag: Switerland, 1999; pp. 100.

- Hisham, F., Maziati Akmal, M. H., Ahmad, F., Ahmad, K., & Samat, N. Biopolymer chitosan: Potential sources, extraction methods, and emerging applications. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 2024, 15(2), 102424. [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, S., Mondal, S., Pal, K., Jana, A., Soren, J. P., Barman, P., Mondal, K. C., & Halder, S. K. Extraction of chitin from Litopenaeus vannamei shell and its subsequent characterization: An approach of waste valorization through microbial bioprocessing. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 2021, 44(9), 1943–1956. [CrossRef]

- Alishahi, A., Mirvaghefi, A., Tehrani, M. R., Farahmand, H., Shojaosadati, S. A., Dorkoosh, F. A., & Elsabee, M. Z. Enhancement and Characterization of Chitosan Extraction from the Wastes of Shrimp Packaging Plants. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 2011, 19(3), 776–783. [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, F., Balasundari, S., Gopalakannan, A., Rathnakumar, K., & Felix, S. Comparison of the Quality of Chitin and Chitosan from Shrimp, Crab and Squilla Waste. Current World Environment, 2017 12(3), 670–677. [CrossRef]

- Hosney, A., Ullah, S., & Barčauskaitė, K. A Review of the Chemical Extraction of Chitosan from Shrimp Wastes and Prediction of Factors Affecting Chitosan Yield by Using an Artificial Neural Network. Marine Drugs, 2022, 20(11), 675. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. P. Chitosan: Manufacture, properties, and usage. 1st ed.; Nova Science Publishers: USA, 2011.

- Santos, V. P., Marques, N. S. S., Maia, P. C. S. V., Lima, M. A. B. de, Franco, L. de O., & Campos-Takaki, G. M. de. Seafood Waste as Attractive Source of Chitin and Chitosan Production and Their Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21(12), E4290. [CrossRef]

- El Knidri, H., Belaabed, R., Addaou, A., Laajeb, A., & Lahsini, A. Extraction, chemical modification and characterization of chitin and chitosan. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 120, 1181–1189. [CrossRef]

- Younes, I., & Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan Preparation from Marine Sources. Structure, Properties and Applications. Marine Drugs, 2015, 13(3), 1133–1174. [CrossRef]

- Cira, L. A., Huerta, S., Hall, G. M., & Shirai, K. Pilot scale lactic acid fermentation of shrimp wastes for chitin recovery. Process Biochemistry, 2002, 37(12), 1359–1366. [CrossRef]

- Neves, A. C., Zanette, C., Grade, S. T., Schaffer, J. V., Alves, H. J., & Arantes, M. K. Optimization of lactic fermentation for extraction of chitin from freshwater shrimp waste. Acta Scientiarum. Technology, 2017, 39(2), 125. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Xie, W., Yu, J., Xin, R., Shi, Z., Song, L., & Yang, X. Extraction of Chitin from Shrimp Shell by Successive Two-Step Fermentation of Exiguobacterium profundum and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2021, 12, 677126. [CrossRef]

- Eddya, M., Tbib, B., & EL-Hami, K. A comparison of chitosan properties after extraction from shrimp shells by diluted and concentrated acids. Heliyon, 2020, 6(2), e03486. [CrossRef]

- Öğretmen, Ö. Y., Karsli, B., & Çağlak, E. Extraction and Physicochemical Characterization of Chitosan from Pink Shrimp (Parapenaeus longirostris) Shell Wastes. Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Borja-Urzola, A. D. C., García-Gómez, R. S., Flores, R., & Durán-Domínguez-de-Bazúa, M. D. C. Chitosan from shrimp residues with a saturated solution of calcium chloride in methanol and water. Carbohydrate Research, 2020, 497, 108116. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K., Muralisankar, T., Jayakumar, R., & Rajeevgandhi, C. A study on structural comparisons of α-chitin extracted from marine crustacean shell waste. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications, 2021, 2, 100037. [CrossRef]

- El-araby, A., El Ghadraoui, L., & Errachidi, F. Usage of biological chitosan against the contamination of post-harvest treatment of strawberries by Aspergillus niger. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2022, 6, 881434. [CrossRef]

- Lizardi-Mendoza, J., Argüelles Monal, W. M., & Goycoolea Valencia, F. M. Chemical Characteristics and Functional Properties of Chitosan. In Chitosan in the Preservation of Agricultural Commodities. Elsevier. 2016, (pp. 3–31). [CrossRef]

- Peter, S., Lyczko, N., Gopakumar, D., Maria, H. J., Nzihou, A., & Thomas, S. Chitin and Chitosan Based Composites for Energy and Environmental Applications: A Review. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2021, 12(9), 4777–4804. [CrossRef]

- Boudouaia, N., Bengharez, Z., & Jellali, S. Preparation and characterization of chitosan extracted from shrimp shells waste and chitosan film: Application for Eriochrome black T removal from aqueous solutions. Applied Water Science, 2019, (4), 91. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Ferreira, S., Castillo, O. S., Madera-Santana, J. T., Mendoza-García, D. A., Núñez-Colín, C. A., Grijalva-Verdugo, C., Villa-Lerma, A. G., Morales-Vargas, A. T., & Rodríguez-Núñez, J. R. Production and physicochemical characterization of chitosan for the harvesting of wild microalgae consortia. Biotechnology Reports, 2020, 28, e00554. [CrossRef]

- Tian, M., Tan, H., Li, H., & You, C. Molecular weight dependence of structure and properties of chitosan oligomers. RSC Advances, 2015, 5(85), 69445–69452. [CrossRef]

- Pavinatto, A., Pavinatto, F. J., Delezuk, J. A. D. M., Nobre, T. M., Souza, A. L., Campana-Filho, S. P., & Oliveira, O. N. Low molecular-weight chitosans are stronger biomembrane model perturbants. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2013, 104, 48–53. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T., Tang, P., & Li, G. Effects of chitosan molecular weight and deacetylation degree on the properties of collagen-chitosan composite films for food packaging. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2022, 139(41). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G. A. F. (1992). Chitin Chemistry. Macmillan Education UK. [CrossRef]

- Ioelovich, M. Nitrogenated Polysaccharides – Chitin and Chitosan, Characterization and Application ,1st ed.; Wiley, USA; 2017.

- Ben Seghir, B., & Benhamza, M. H. Preparation, optimization and characterization of chitosan polymer from shrimp shells. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 2017, 11(3), 1137–1147. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, H. N., Zia, K. M., Rehman, S., Ilyas, R., & Sultana, S. Utilization of Shellfish Industrial Waste for Isolation, Purification, and Characterizations of Chitin from Crustacean’s Sources in Pakistan. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 2021, 29(7), 2337–2348. [CrossRef]

- Muley, A. B., Chaudhari, S. A., Mulchandani, K. H., & Singhal, R. S. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from prawn shell waste and its conjugation with cutinase for enhanced thermo-stability. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 111, 1047–1058. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C., De Mello, J. M. M., Dalcanton, F., Macuvele, D. L. P., Padoin, N., Fiori, M. A., Soares, C., & Riella, H. G. Mechanical, Thermal and Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan-Based-Nanocomposite with Potential Applications for Food Packaging. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 2020, 28(4), 1216–1236. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M., Khadem, S., Cakmak, Y. S., Mujtaba, M., Ilk, S., Akyuz, L., Salaberria, A. M., Labidi, J., Abdulqadir, A. H., & Deligöz, E. Antioxidative and antimicrobial edible chitosan films blended with stem, leaf and seed extracts of Pistacia terebinthus for active food packaging. RSC Advances, 2018, 8(8), 3941–3950. [CrossRef]

- Sarbon, N. M., Sandanamsamy, S., Kamaruzaman, S. F. S., & Ahmad, F. Chitosan extracted from mud crab (Scylla olivicea) shells: Physicochemical and antioxidant properties. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2015, 52(7), 4266–4275. [CrossRef]

- Oyatogun, G. M., Esan, T. A., Akpan, E. I., Adeosun, S. O., Popoola, A. P. I., Imasogie, B. I., Soboyejo, W. O., Afonja, A. A., Ibitoye, S. A., Abere, V. D., Oyatogun, A. O., Oluwasegun, K. M., Akinwole, I. E., & Akinluwade, K. J. Chitin, chitosan, marine to market. In Handbook of Chitin and Chitosan, Elsevier, 2020, (pp. 335–376). [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Li, J., Tang, Q., Qiu, P., Gou, D., & Zhao, J. Chitosan-Based Materials: An Overview of Potential Applications in Food Packaging. Foods, 2022, 11(10), 1490. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K., & Bugusu, B. Food Packaging Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues. Journal of Food Science, 2007, 72(3), R39–R55. [CrossRef]

- Khouri, J., Penlidis, A., & Moresoli, C. Viscoelastic Properties of Crosslinked Chitosan Films. Processes, 2019, 7(3), 157. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. R., Escobar, A. P., Andris, M. N., Boardman, B. M., & Peters, G. M. Understanding the Molecular-Level Interactions of Glucosamine-Glycerol Assemblies: A Model System for Chitosan Plasticization. ACS Omega, 2021, 6(39), 25227–25234. [CrossRef]

- Escárcega-Galaz, A. A., Sánchez-Machado, D. I., López-Cervantes, J., Sanches-Silva, A., Madera-Santana, T. J., & Paseiro-Losada, P. Mechanical, structural and physical aspects of chitosan-based films as antimicrobial dressings. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 116, 472–481. [CrossRef]

- Leceta, I., Guerrero, P., Ibarburu, I., Dueñas, M. T., & De La Caba, K. Characterization and antimicrobial analysis of chitosan-based films. Journal of Food Engineering, 2013, 116(4), 889–899. [CrossRef]

- Pavinatto, A., De Almeida Mattos, A. V., Malpass, A. C. G., Okura, M. H., Balogh, D. T., & Sanfelice, R. C. Coating with chitosan-based edible films for mechanical/biological protection of strawberries. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 151, 1004–1011. [CrossRef]

- Basiak, E., Lenart, A., & Debeaufort, F. How Glycerol and Water Contents Affect the Structural and Functional Properties of Starch-Based Edible Films. Polymers, 2018, 10(4), 412. [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M., Morsi, R. E., Kerch, G., Elsabee, M. Z., Kaya, M., Labidi, J., & Khawar, K. M. Current advancements in chitosan-based film production for food technology; A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 121, 889–904. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Y., Marsh, K. S., & Rhim, J. W. Characteristics of Different Molecular Weight Chitosan Films Affected by the Type of Organic Solvents. Journal of Food Science, 67(1), 2002, 194–197. [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, M. A., Nikolaeva, A. L., Bobrova, N. V., Vorobiov, V. K., Smirnov, A. V., Lahderanta, E., & Sokolova, M. P. Self-healing films based on chitosan containing citric acid/choline chloride deep eutectic solvent. Polymer Testing, 2021, 97, 107156. [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, M., Hammami, A., Hajji, S., Jridi, M., Nasri, M., & Nasri, R. Chitin extraction from blue crab (Portunus segnis) and shrimp (Penaeus kerathurus) shells using digestive alkaline proteases from P. segnis viscera. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2017, 101, 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Yuan, Y., Duan, S., Li, C., Hu, B., Liu, A., Wu, D., Cui, H., Lin, L., He, J., & Wu, W. Preparation and characterization of chitosan films with three kinds of molecular weight for food packaging. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 155, 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P., & Vázquez, M.. Mechanical and barrier properties of chitosan combined with other components as food packaging film. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 2020, 18(2), 257–267. [CrossRef]

- Balbinot-Alfaro, E., Craveiro, D. V., Lima, K. O., Costa, H. L. G., Lopes, D. R., & Prentice, C. Intelligent Packaging with pH Indicator Potential. Food Engineering Reviews, 2019, 11(4), 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S., Mehrotra, G. K., & Dutta, P. K. Physicochemical and bioactivity of cross-linked chitosan–PVA film for food packaging applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2009, 45(4), 372–376. [CrossRef]

- Kou, S. (Gabriel), Peters, L. M., & Mucalo, M. R. Chitosan: A review of sources and preparation methods. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2021, 169, 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Goy, R. C., Morais, S. T. B., & Assis, O. B. G. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of chitosan and its quaternized derivative on E. coli and S. aureus growth. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 2016, 26(1), 122–127. [CrossRef]

- Rachtanapun, P., Klunklin, W., Jantrawut, P., Jantanasakulwong, K., Phimolsiripol, Y., Seesuriyachan, P., Leksawasdi, N., Chaiyaso, T., Ruksiriwanich, W., Phongthai, S., Sommano, S. R., Punyodom, W., Reungsang, A., & Ngo, T. M. P. Characterization of Chitosan Film Incorporated with Curcumin Extract. Polymers, 2021, 13(6), 963. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Qiao, C., Wang, X., Yao, J., & Xu, J. (2019). Structural characterization and properties of polyols plasticized chitosan films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 135, 240–245. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Xie, F., Tang, F., & McNally, T. Glycerol plasticisation of chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose composites: Role of interactions in determining structure and properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 163, 683–693. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I., & Siracusa, V. The Use of Thermal Techniques in the Characterization of Bio-Sourced Polymers. Materials, 2021, 14(7), 1686. [CrossRef]

- Maria V, D., Bernal, C., & Francois, N. J. Development of Biodegradable Films Based on Chitosan/Glycerol Blends Suitable for Biomedical Applications. Journal of Tissue Science & Engineering, 2016, 07(03). [CrossRef]

| Film | MC (%) | SP (%) | S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan Film | 21.74 | 8.27 | 64.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).