3.2. Effect of Production Method and Temperature on PL Biochars’ pH

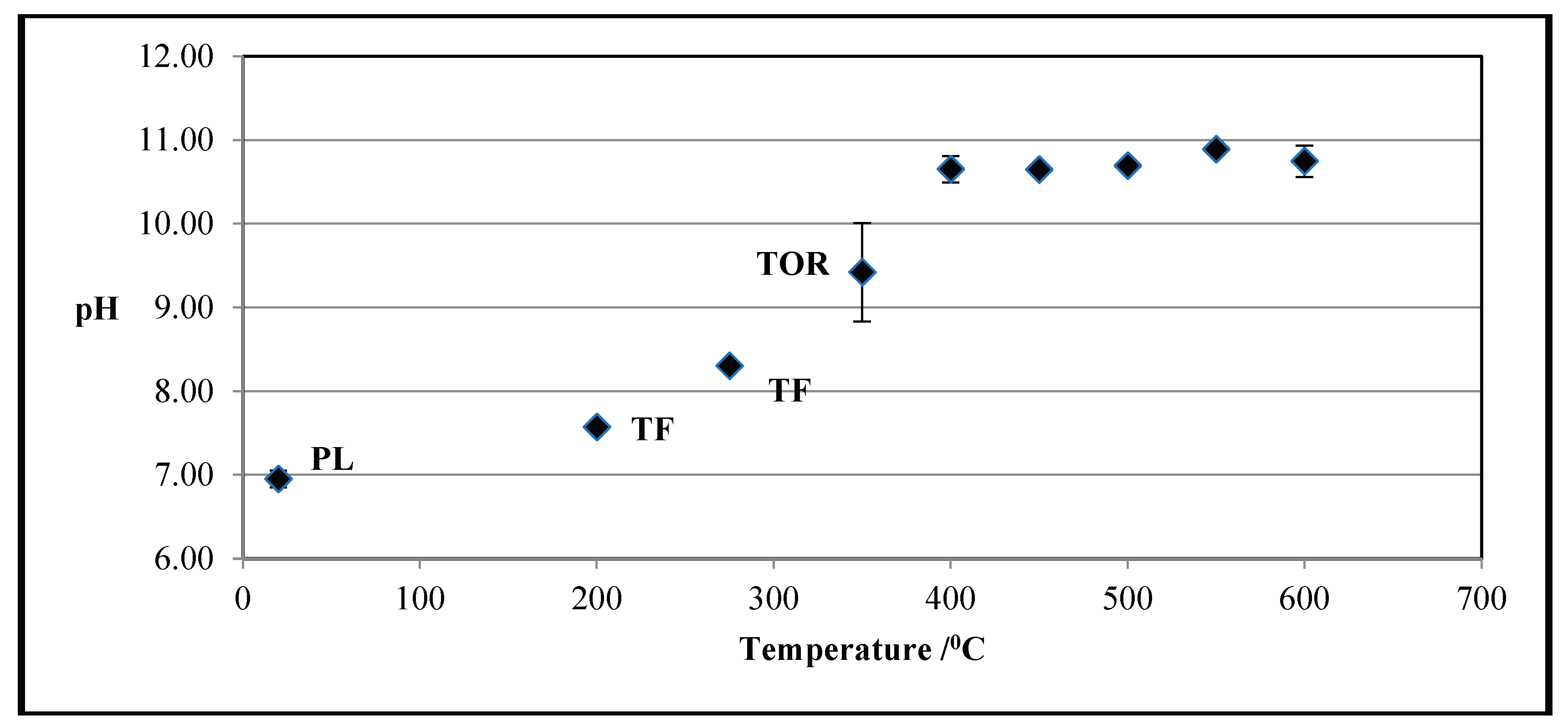

Figure 1 above shows the influence of temperature on biochar’s pH in the case of tube furnace and torrefied samples, merged together to give changes over a greater temperature range, as compared with the poultry litter’s pH. Poultry litter is neutral, but as temperature increases, so does pH, levelling out at about 10.7 from 400°C onwards, demonstrating that the most of acidic groups were lost during the pyrolysis process and as all the volatile matters were leached from the pyrolytic structure, the pH became constant. Other studies have found similar pH values of 9.5 at 300°C to 11.5 at 600°C (Song and Guo, 2012). Gaskin et al. (2008) reported that biochars generated from PL, peanut hulls, and pine chips through 400°C pyrolysis had pH 10.1, 10.5, and 7.6, respectively. Higher pH at the higher pyrolysis temperatures is expected because of the increased relative concentration of non-pyrolyzed inorganic elements in the feedstocks and the formation of hydroxides and basic surface oxides (Cao and Harris, 2010). It is reported that inorganic carbonates were the major alkaline components of the biochar generated at high temperature, and that organic anions contributed to the alkalinity of biochar generated at low temperature (Uchimiya et al., 2011).

There is a consensus in literature that pH increases with pyrolysis temperature, but the magnitude of this increment depends on the raw material characteristics (Cely et al., 2015).

Hydrothermal carbonisation produces also a liquor (process water) along with the solid biochar samples. Therefore, the pH of the HTC samples was measured for both, as a function of temperature and residence time. Although the HTC was run at increasing temperatures, from 80°C to 237°C, there was insufficient solid formed at temperatures higher than 120°C to do the pH tests. Therefore, there are only results for two temperatures, i.e., 80°C and 120°C, respectively. For each temperature, the residence time to run the HTC varied from 5 – 120 minutes. The pH of the solid samples was 3.8 at 80°C and 5.6 at 120°C, respectively.

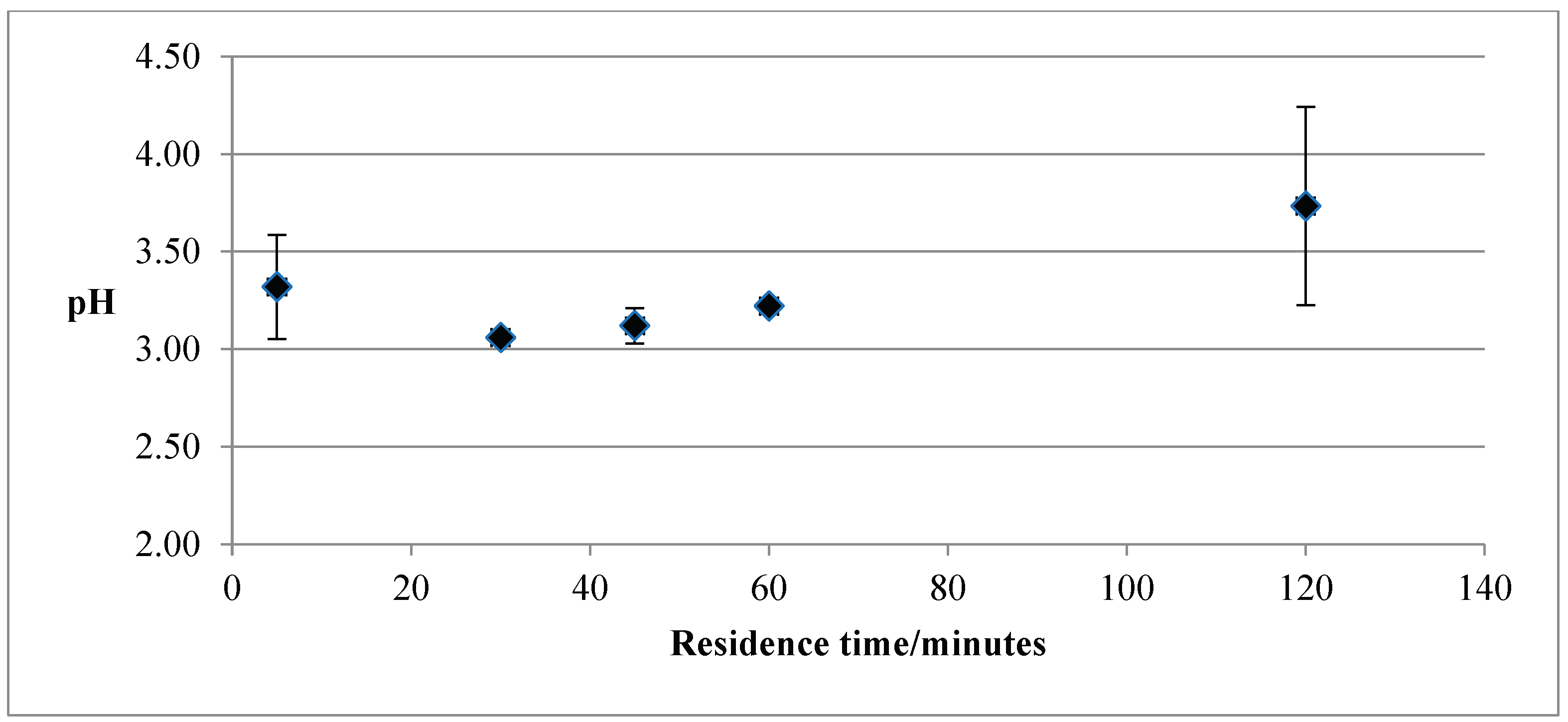

Figure 2 shows the pH variation of the liquor as a function of the residence time for the HTC temperature of 120°C. The primary determinants of the pH of the HTC liquor are the raw material, PL in this case, and the liquid added, which was citric acid. Therefore, as expected, the pH was acidic, varying slightly with the residence time. This is another expected result, as the pH of the liquor was measured when the system was cooled down, therefore, the actual residence time was much longer than the HTC’s running time.

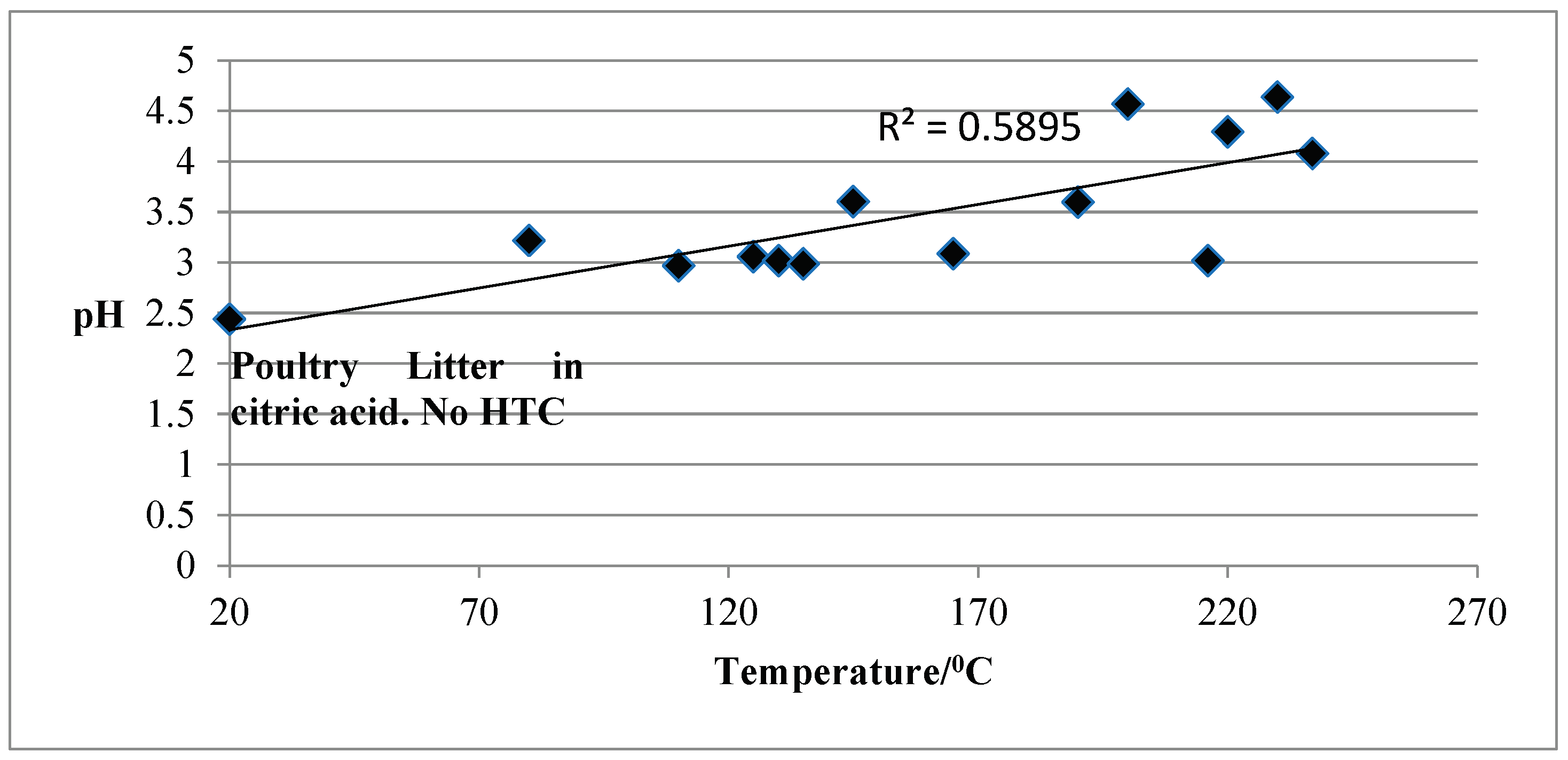

Figure 3 shows the pH of the process’ water as a function of temperature. For all temperatures, the pH of the liquor was acidic, with values from 2.97, at lower temperatures, to 4.57 at higher temperatures. Poultry litter’s pH in the HTC medium (citric acid) at 20°C was 2.44.

Acidic pH was observed for the process water samples even when the HTC was performed in pure water. The pH of the spent liquor from hydrothermal carbonization of PL, at the PL to water ratio of 1:5, 225°C and 15 min residence time, was 5.5 and unchanged by recirculation (Catalkopru et al., 2017). This finding supports the approach of using the spent liquor as a HTC medium for fresh HTC treatments, although, at one point in time, the process water should be disposed of, which will be a challenge due to the acidic nature.

However, the initial pH of the HTC medium is important as it impacts on the yields and properties of the hydrochar (HC). It has been found that undertaking HTC in the presence of acids (CH3COOH, H2SO4) significantly affects the yields and properties of HC. The C content and HHV of the HC increased with decreasing initial pH. In the presence of H2SO4, the hydrochar yield increased while the ash content was significantly reduced. The lowest ash content and the highest hydrochar yield were measured in the HC produced from the suspension with an initial pH of 2 using H2SO4.

The acidic pH is due to the formation of organic acids that dissolve in the process water.

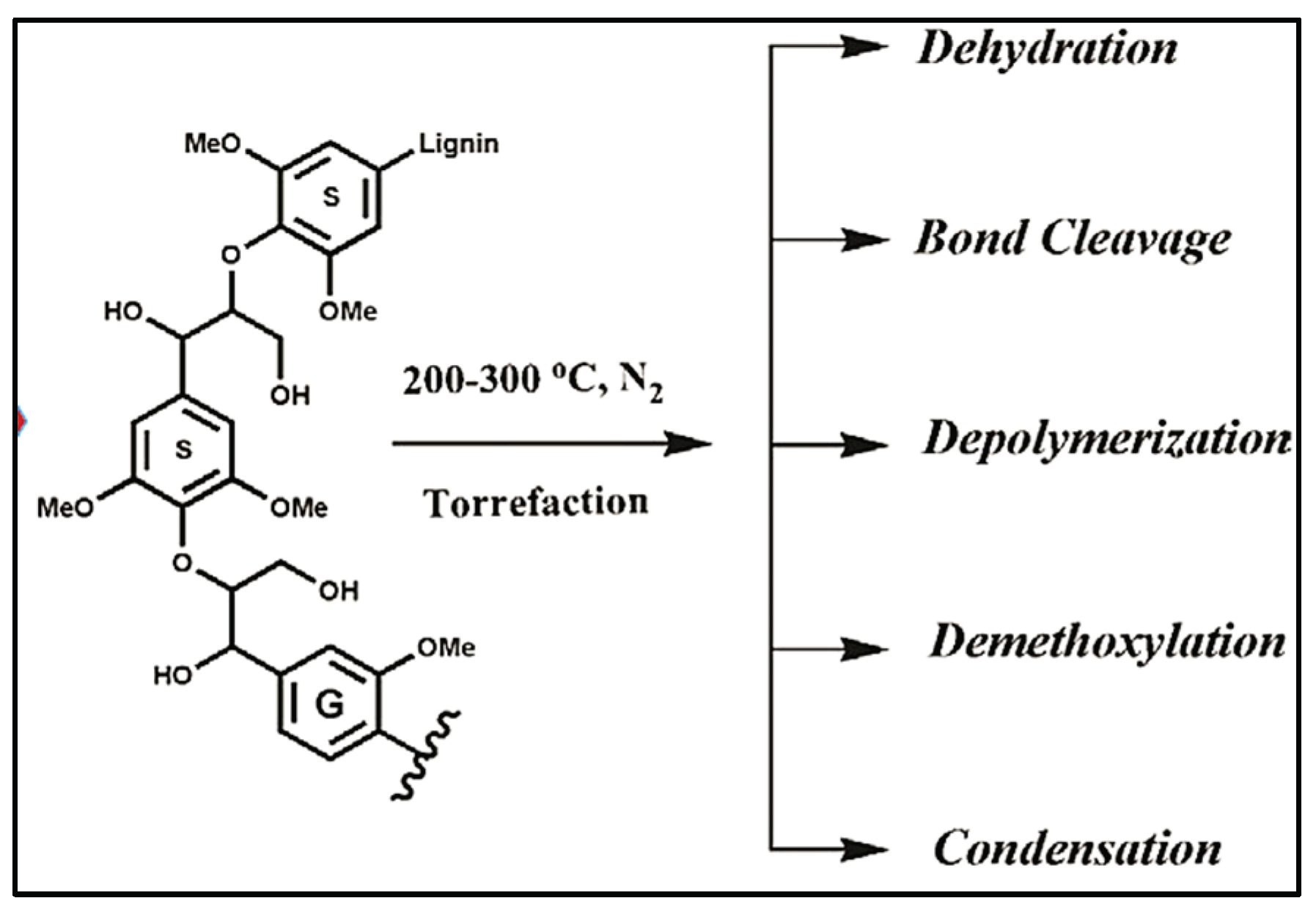

As it is well-known, HTC is an exothermic process that lowers both the oxygen and hydrogen content of the feed (described by the molecular O/C and H/C ratio) by five main reaction mechanisms which include hydrolysis, dehydration, decarboxylation, polymerization and aromatization (Funke and Ziegler, 2010; Hoekman et al., 2011).

Although the catalytic effect of the acidic pH on hydrolysis and dehydration of biomass is acknowledged, the effects of acidic conditions on other reaction mechanisms, such as decarboxylation and condensation polymerization, is largely unknown. It has been reported, however, that weakly acidic conditions improve the overall rate of reaction of hydrothermal carbonization (Titirici et al., 2007).

It is important that the pH of different biochars to be accurately determined because changes of pH have great impacts on many soil processes, such as nitrogen mineralization, mineral precipitation, ion exchange, and greenhouse gas emissions (Zhang et al., 2018).

3.3. Effect of Production Method and Temperature on Samples’ Morphology, Composition, and Structure

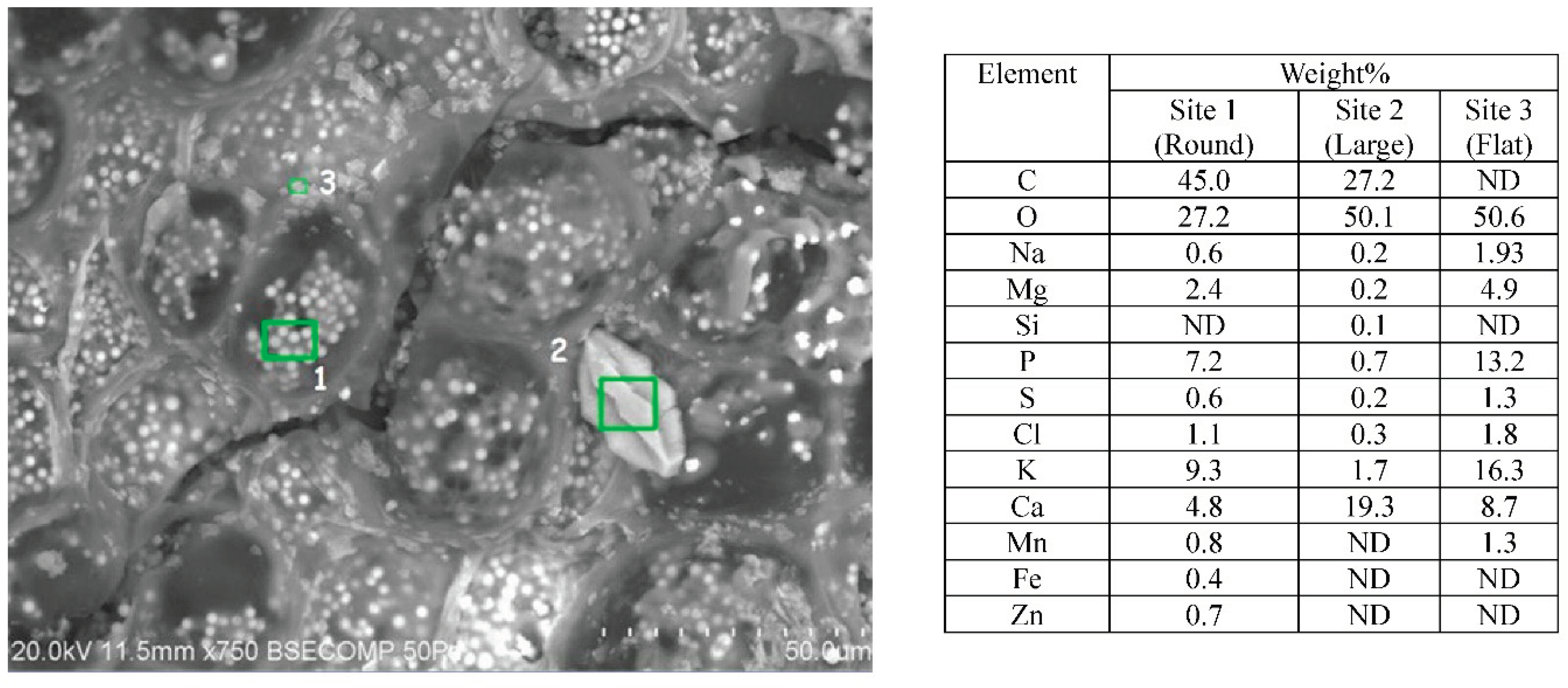

SEM-EDX measurements were performed over most of the samples (

Table 2). The SEM micrographs showed the presence of different structures, some crystalline ones, coating the biochar particles or grown on the surface of a complex 3D lattice, some amorphous ones, while the morphology of the char samples was mainly a macroporous one. The composition of the different surface structures was determined, and the identification of their type and provenience was done based on the EDX results alone or by comparing them with those obtained on barley, feathers, or wheat straws. An attempt was made to determine the pores size and their distribution.

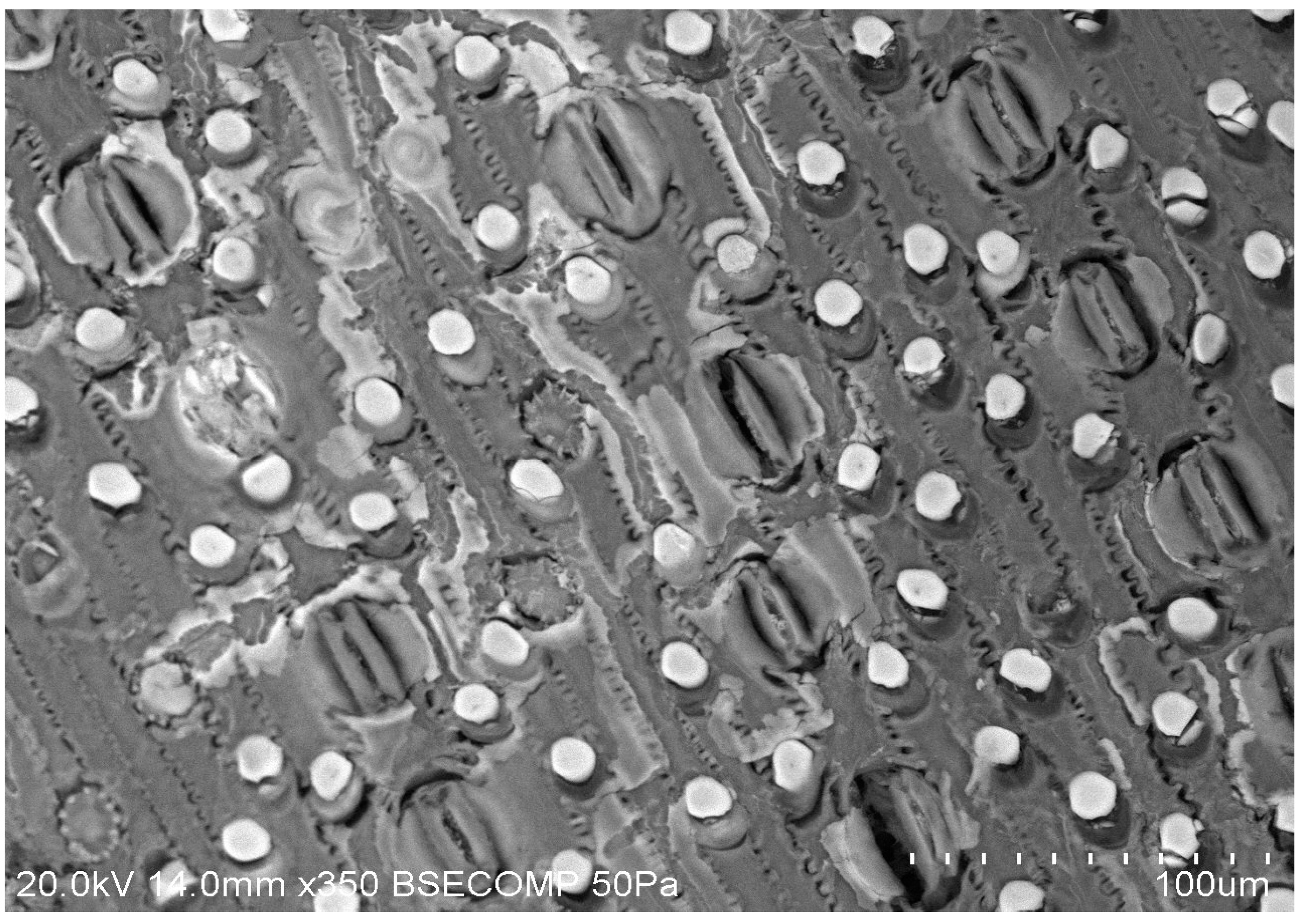

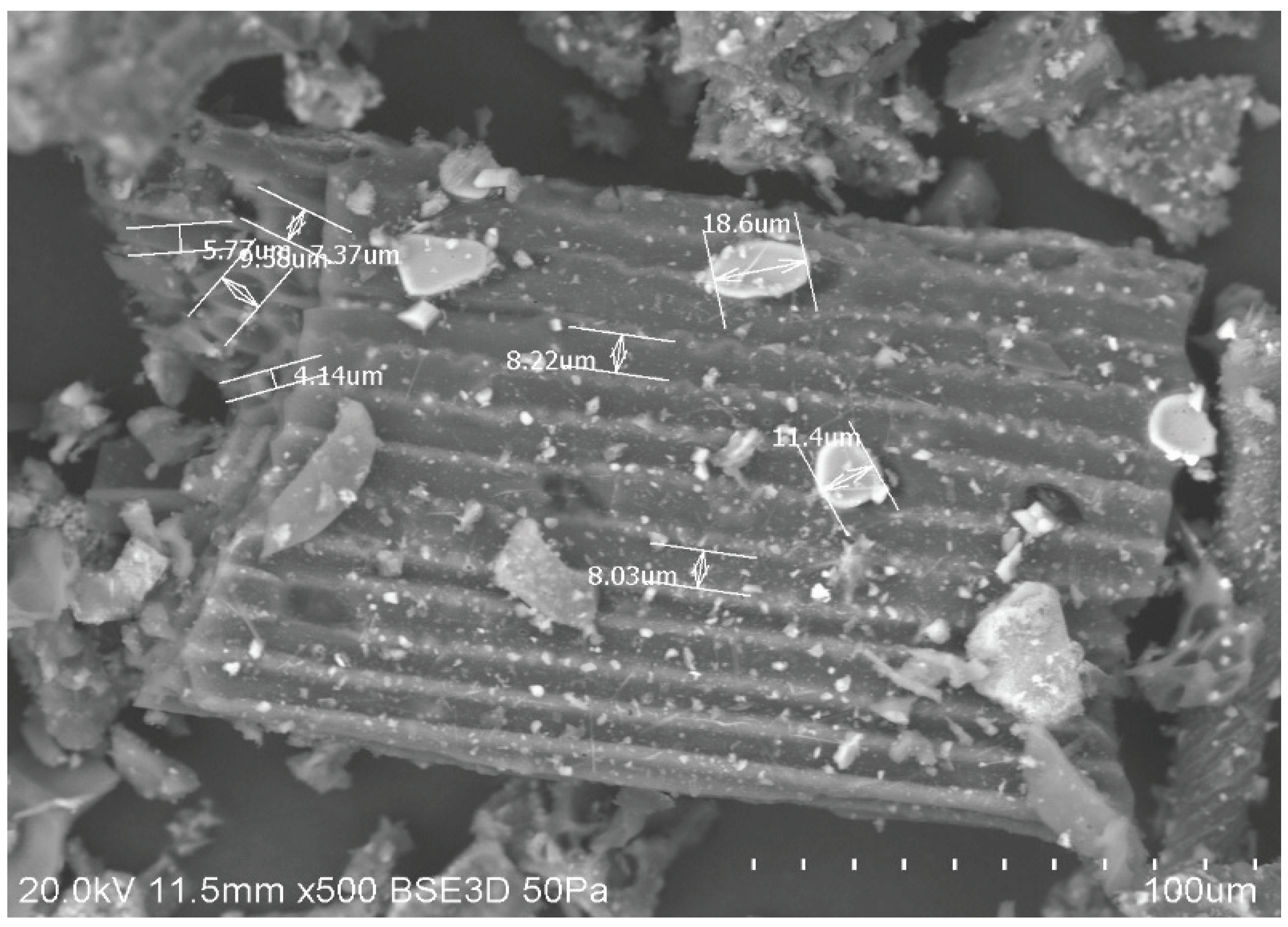

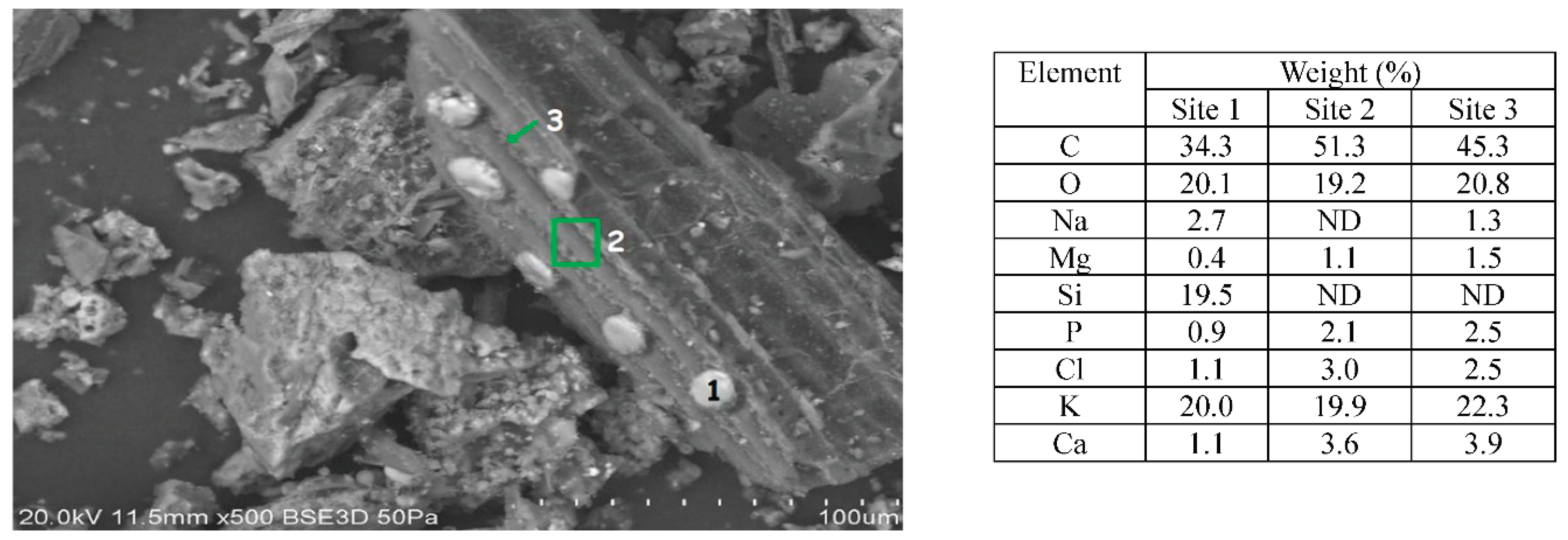

As shown in

Figure 4, two more obvious structures are present in the mixture of the HTC chars, one white and round and the other one which looks like a grass epidermis, showing stomata and phytoliths. The elemental analysis proved that the round structures are siliceous and about 10-20 µm in size. These siliceous structures were found in many of the chars and appear to be loosely attached to the surface (see

Figure 5.).

In order to identify the provenience of these siliceous structures, EDX measurements were performed on them and on the background material, and the results were compared with those obtained on siliceous structures in wheat and barley. The stems did not show the siliceous structures, but the leaves did, showing that these structures are not caused by torrefaction. Elemental composition in wheat and barley is just C, O, and Si. However, these non-torrefied structures contain more oxygen which would be expected as combustion reduces oxygen content. The other elements on the char samples may be material deposited on the surface during torrefaction (

Figure 6,

Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 6 shows the results obtained on the TOR 600 sample, while

Figures S1 and S2 present the SEM-EDX results obtained on the oven dried wheat straw and barley leaves, respectively.

As shown in

Figure S1, the wheat sample presents siliceous structures and stomata. Barley (see

Figure S2) has similar structures, although the elemental composition is more varied containing K, Cl and Na. Stomata are also visible.

The size of the siliceous structures was measured for torrefied samples as well and compared with the size of the siliceous structures in PL, wheat, and barley. The average size decreases as temperature increases, i.e., for TOR 400 is 20.4µm, while for TOR 500 the value is 15µm. The size of the siliceous structures in PL is, in average, 15.6 µm, for wheat is 17.6µm, while for barley is 13.6µm, respectively. The size comparison and appearance suggest that the siliceous structures are probably wheat. However, the sample is too small to be certain – it is possible that both are present.

What is more, SEM images of PL (

Figure 7) reveal the presence of other siliceous structures which do not look like those found in either oven dried wheat straw or barley leaves.

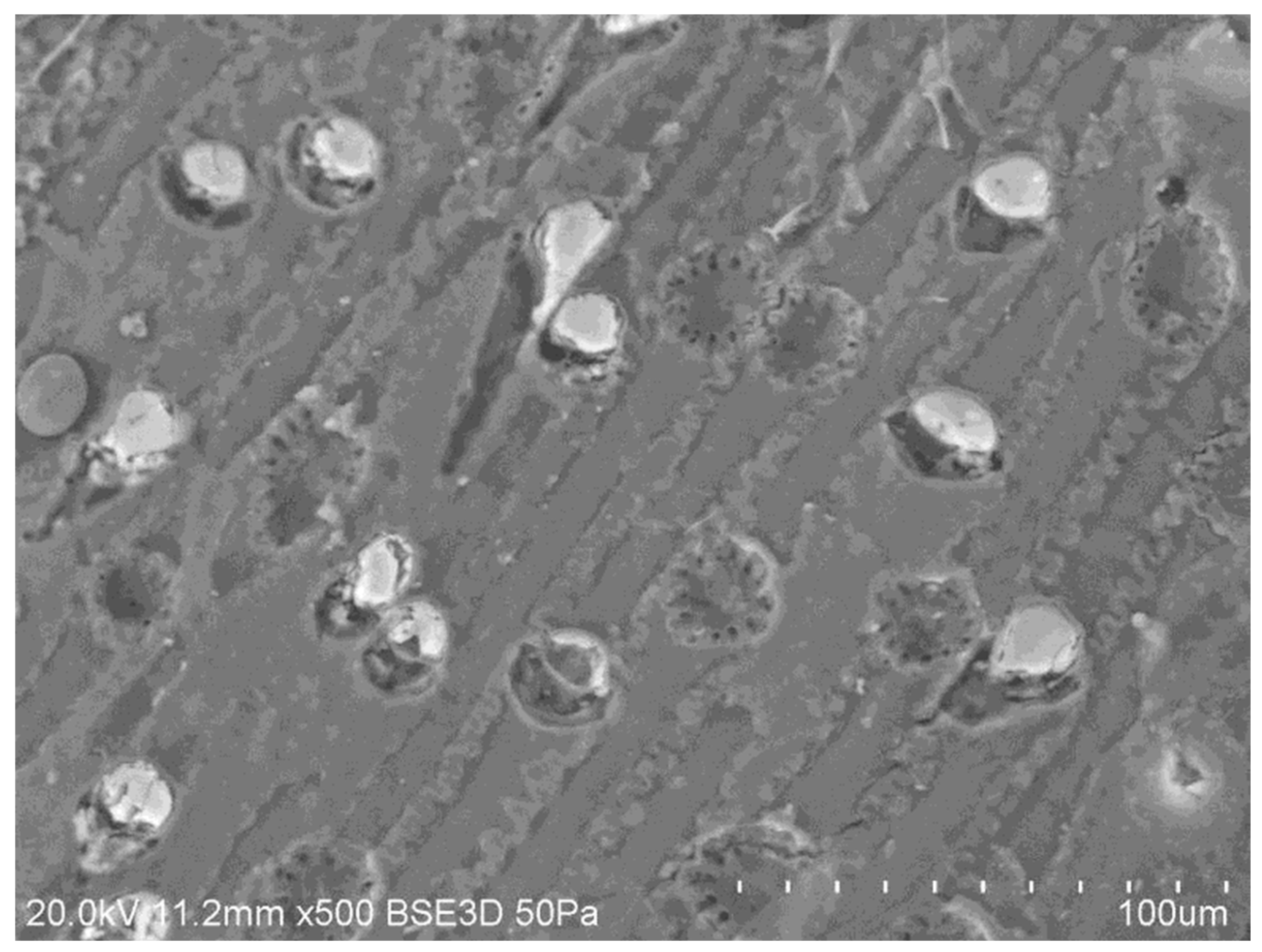

For PL, the structures seem to be in hollows. Also visible are what appear as wiggly lines between cells. These are probably phytoliths and can be seen in greater detail on the barley leaf (

Figure S3). They are about 124 µm in length and are composed mainly of silicon. Phytoliths are used in archaeology to identify species as they are resistant to decay, so could be used to identify the plant material a char is derived from (Jenkins, 2009). Phytoliths are primarily silica and can be a problem if feedstock is used as a fuel (Cennatek, 2011).

These phytolith structures remained and were visible in ash samples – not surprising as they are separated from plant material by ashing (Jenkins, 2009) (see

Figure 8).

There were other amorphous structures found in torrefied material that looked like feathers (see

Figure S4) and had a similar chemical composition. To test their provenience, feathers and torrefied feathers were analysed.

As can be seen, the actual feather structure is a main rib with side branches emerging, similar to the structure shown in TF135. These branches appear to be strap-like and narrow as they get further from the main rib. Torrefaction causes feathers to lose most of its fine structure. The size is also similar. Elemental analysis also suggests that this is a feather (results not shown). The C and O percentages are similar for the actual feathers and the structures in TF135. Feathers are made of the protein keratin, which has high levels of S, as seen in the elemental analysis. The TF135 feather has a low S value, but this could be a result of natural variation. Another problem is the difference between the feather heated to 450°C and that heated to 105°C (oven dried). Heating seems to cause a loss of Na and Ca; however, the difference may be because feather was not of the same type, it was taken from a local bird rather than from the PL.

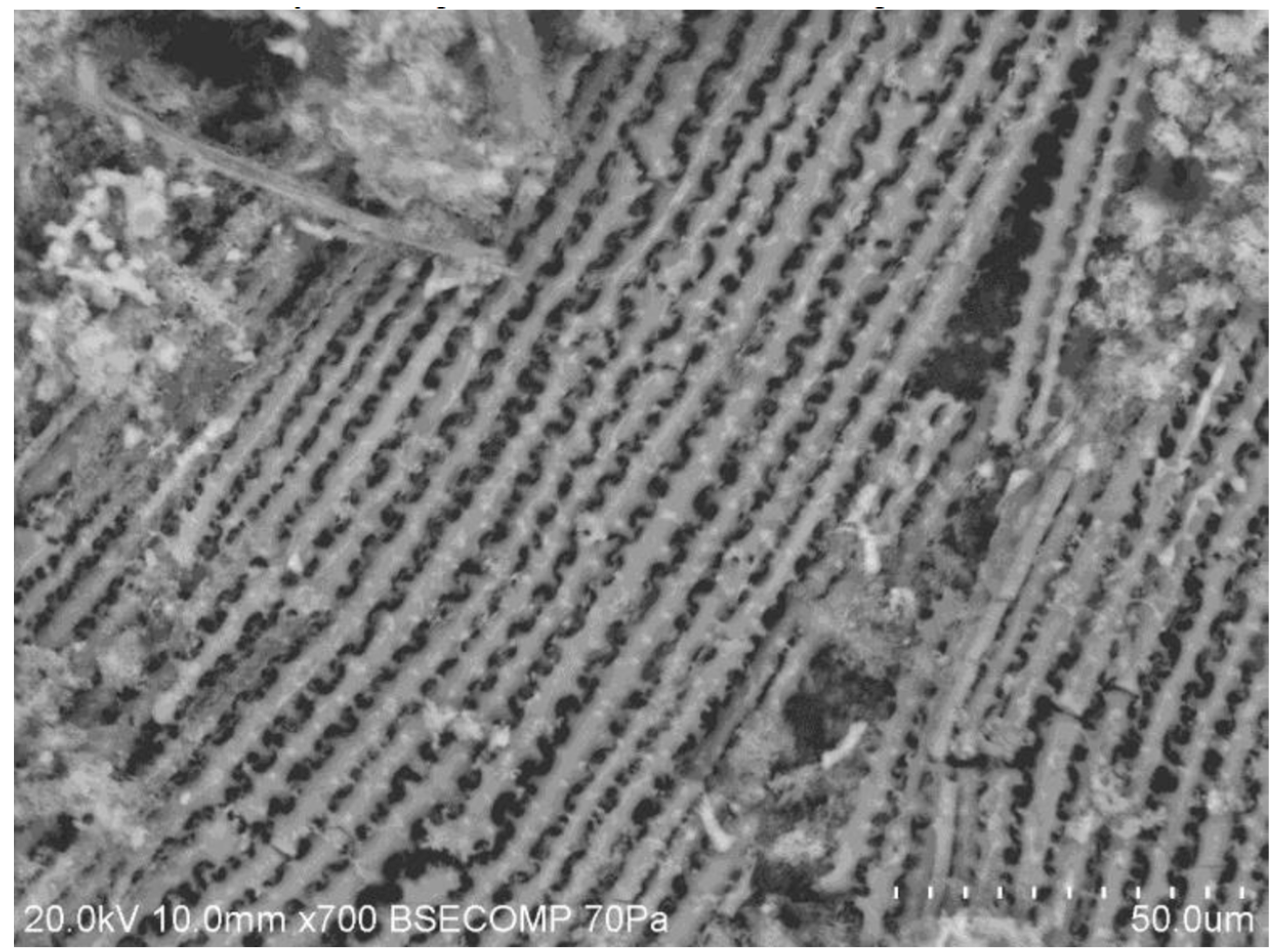

As for the hydrothermal carbonisation samples, some more and different amorphous structures were shown (see

Figure 9). Many fine white structures, 700nm – 2µm long, are visible. These could be cellulose fibrils as literature suggests that HTC treatment breaks down hemicellulose, which causes individual cellulose fibres to separate. Debris from the cell wall is then deposited on the surface of the hydrochars (Kristensen

et al., 2008). However, microfibrils are 28nm in diameter so these fibres are too large – they may be aggregations of microfibrils.

Structures like roots were also observed. Diameter of these structures is about 20µm for larger ones, going down to 2µm for finer branches. These are about the correct size and similar structure to roots.

Many structures appear crystalline with very regular shapes and distinct angles. These structures, which are found on the surface, seem primarily inorganic and may, therefore, be very important when PL is used as a soil amendment.

The crystalline structures found on the TOR 350, TOR 450 and TOR 550 sample, respectively, along with those found on the TF 350 and TF 275 samples were studied in detail. Results are as follows.

Figure 10 presents the SEM images of the crystalline structures observed on the complex 3D network of the TOR 350 char sample along with their composition. These crystals are about 2µm on one face and appear cuboid. The elemental analysis shows high amounts of K and Cl, so these crystals could be potassium chloride.

In order to support this statement, pure KCl crystals were characterised by SEM/EDX (

Figure S5). The K:Cl ratio is 1.1 for the pure KCl crystal, very close (+/- 1%) to the published value (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2019), while for the TOR 350 char sample, this ratio is 1.4. Therefore, even all the Cl is in the form of KCl, that still leaves some K and, with high amounts of carbon and oxygen present, also suggests a possible presence of potassium carbonate, K

2CO

3, which is deliquescent. KCl crystals are also hydroscopic.

Crystalline structures are found in other samples as well, in some cases in very large quantities as for the TOR 450 char sample. There are two types of crystalline structures observed, some bright white ones and some grey ones, with very similar composition, but with far lower Cl and higher Ca percentage, respectively, for the grey ones. The K:Cl ratio for the bright white ones is 1.5, which supports the assumption that they are most probably KCl crystals. These crystals are about 2µm on one face and appear cuboid (see

Figure 11).

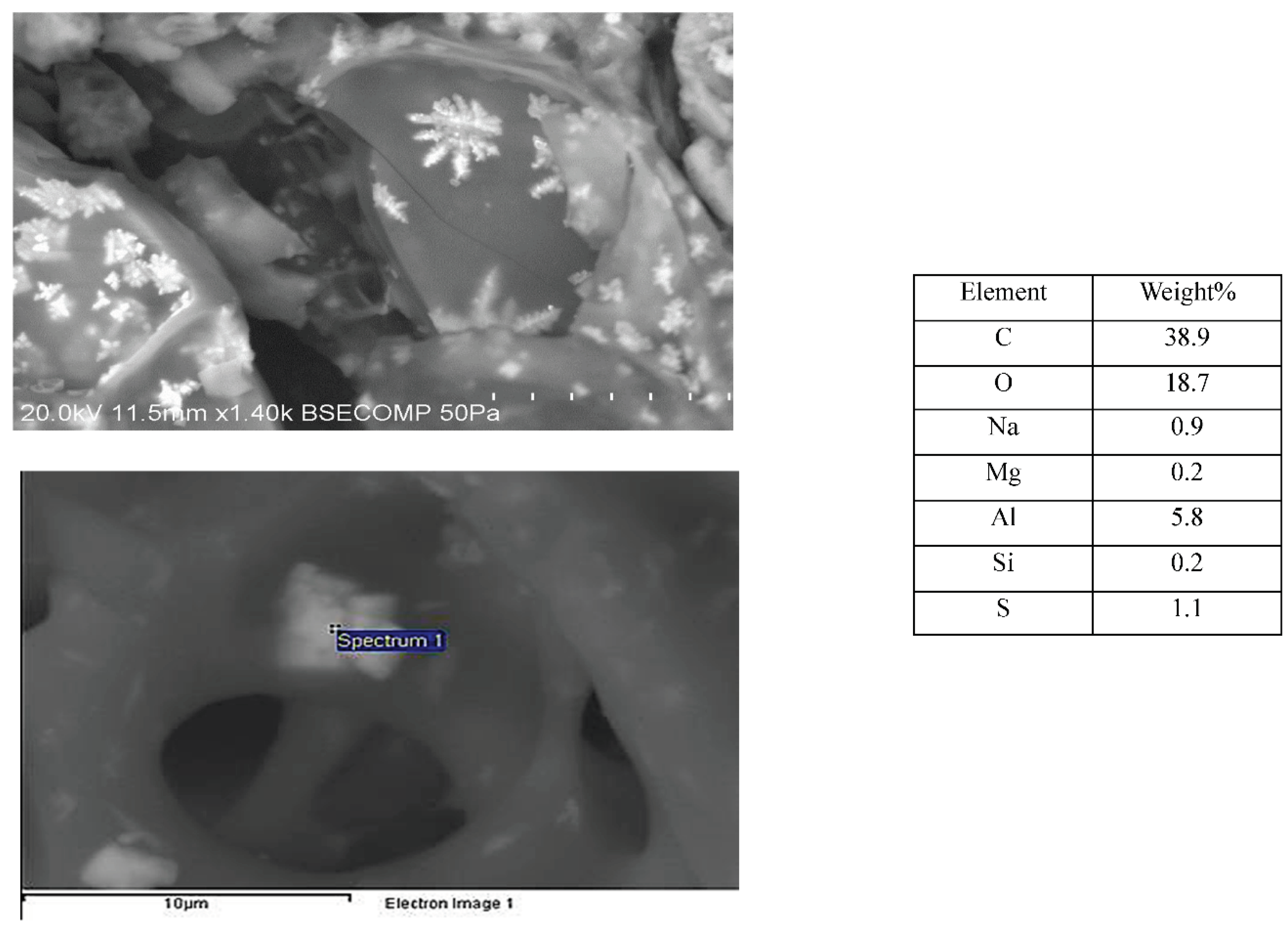

The SEM/EDX results on the TOR 550 sample are presented in

Figure 12. The crystalline structure measured has a high percentage of P, K and Mg, confirmed as pyrocoproite (K

2MgO

7P

2) ((Prakongkep et al., 2013)) via XRD. Also, although it has a very high concentration of K but only little Cl it means that K is present in forms other than KCl.

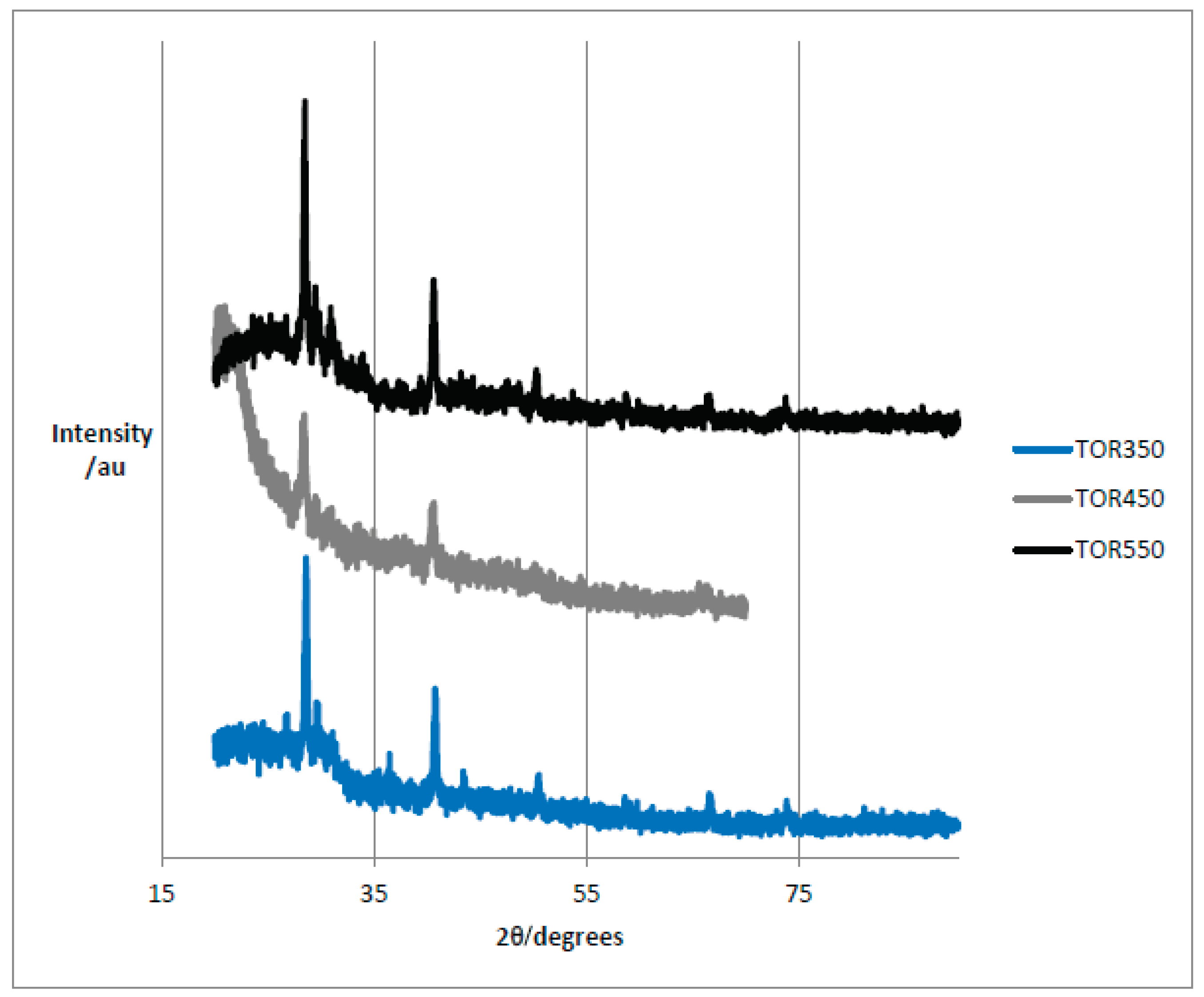

Wide-angle XRD measurements were performed in order to identify the nature of all crystals present on the torrefied samples.

Figure 13 shows the diffractograms for the three torrefaction samples, namely TOR 350, TOR 450 and TOR 550, respectively.

The samples are broadly similar except TOR 450 has a high intensity peak at 2θ of 21º. It is difficult to explain why this peak is only present in TOR 450, although this sample was analysed at a later date and used the modified method with adhesive tape. However, there are several other peaks which are at the same positions for all chars - these are considered more reliable and will be analysed below.

TOR 350 and TOR 550 (low and high production temperature) show a similar general shape and peaks, although the intensity of the peaks seems higher for the higher temperature. Generally, higher intensity and a narrower peak indicate a larger crystal size. The crystal size can be calculated using the Scherrer equation. For TOR 450 the peak at about 2θ = 21º could be an amorphous silica peak, as seen in rice husk char at 2θ = 22.5º. TOR 350 shows a more obvious broad peak at 22.5º, suggesting more silica at lower temperatures. Amorphous carbon also shows a peak in this area (Prakongkep et al., 2013, Treacy and Higgins, 2007).

Table 3 presents the peak’s identification for the three torrefaction samples. The conclusion from the XRD measurements is that sylvite is present in all samples; calcite and quartz are also present. There are some diffraction peaks in TOR 550 which are difficult to identify. The complex mixture of minerals that might be present causes problems with identification. In rice husk char for example, as well as sylvite and calcite, a number of complex potassium minerals were present: archerite (KH

2PO

4), chlorocalcite (KCaCl

3), kalicinite (KHCO

3), pyrocoproite (K

2MgO

7P

2), struvite (KMgPO

4.6H

2O) (Prakongkep et al., 2013). All of these are possibly present given the elemental composition found by EDX but may be present in only small quantities and be undetectable.

Another XRD study of chicken manure identified calcite, hydroxyapatite, struvite, dolomite, quartz and magnesium phosphate (Joseph et al., 2008). This study found calcite and quartz - again the others may be present in low quantities in the studied PL, but the fact that sylvite is not present is surprising. This implies that the sylvite possibly originates from the plant material, which is not present in manure. This is supported by another study which found sylvite in a 300°C biochar from straw (Brassica campestris). In this case the higher temperature biochars had no sylvite but did show calcite and dolomite (Yuan et al., 2011).

The size of the sylvite crystallites was determined by using Scherrer equation. For 2θ around 28º, the size of the sylvite crystal was 28.5 at 350°C, 21.4 at 450°C, and 21.4 at 550°C, respectively. As for 2θ around 40, the size of the sylvite crystal was 24.6 at 350°C, 22.1 at 450°C, and 22.1 at 550°C, respectively. There is no obvious trend for crystal size with temperature, with all values being similar for a given peak.

One problem with XRD is that it is best suited to analysis of homogenous material rather than these heterogeneous chars. It has a detection limit of 2% for components in mixtures, so substances present in low concentrations may not be detected (Dutrow and Clark, 2013).

A variety of crystalline structures were observed as well on the surface of the biochar samples prepared in the tube furnace.

Figure 14 presents the SEM micrograph along with EDX composition for the TF 275 sample, while

Figure 15 shows SEM/EDX results on the TF 350 biochar sample.

The large crystal observed on the TF 275 sample is probably calcium carbonate (calcite), whilst the flat crystal is possibly some type of phosphate. The round crystal could be potassium carbonate (K2CO3) or possibly pyrocoproite (K2MgP2O7) which was found to be present in the XRD results (not shown).

The crystalline structure shown on the TF 350 sample is most probably aluminosilicate.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first time that the crystalline structures on the surface of the poultry litter biochar were identified, and their composition determined.

Some of the feedstock nutrients, namely P, K, Ca and Mg, were concentrated on the surface and their content increases with increasing the pyrolysis temperature. It is important to know the type and composition of the crystalline structures on the surface of the biochars as these crystals are the first to be released into the soil, to cycle nutrients back into agricultural fields. As a measure of the direct nutrient value of biochars, it is not the total content but, rather, the availability of the nutrient that is an important consideration.

Hydrochar samples showed no crystals on the surface as they, presumably, dissolved in the process water.

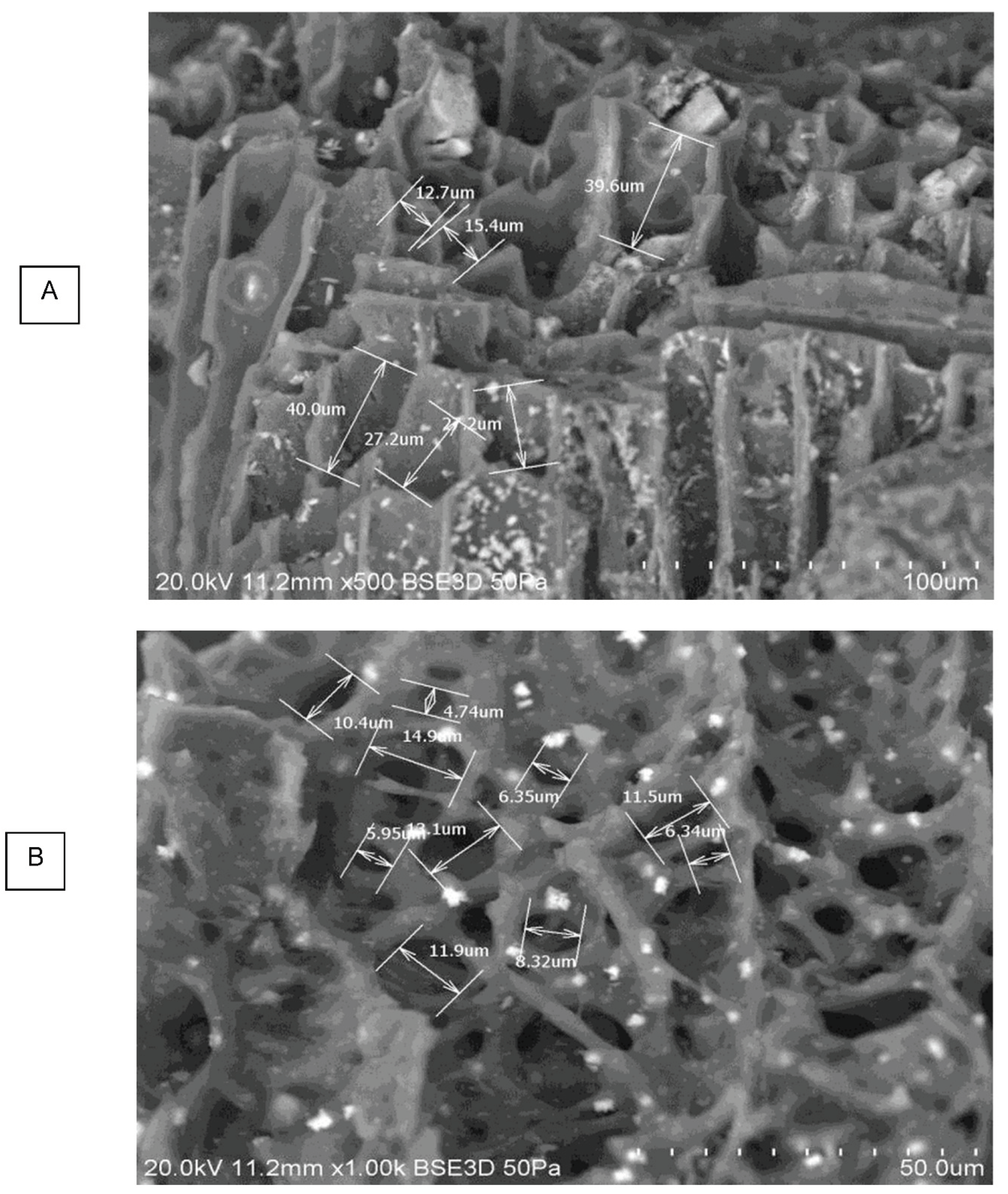

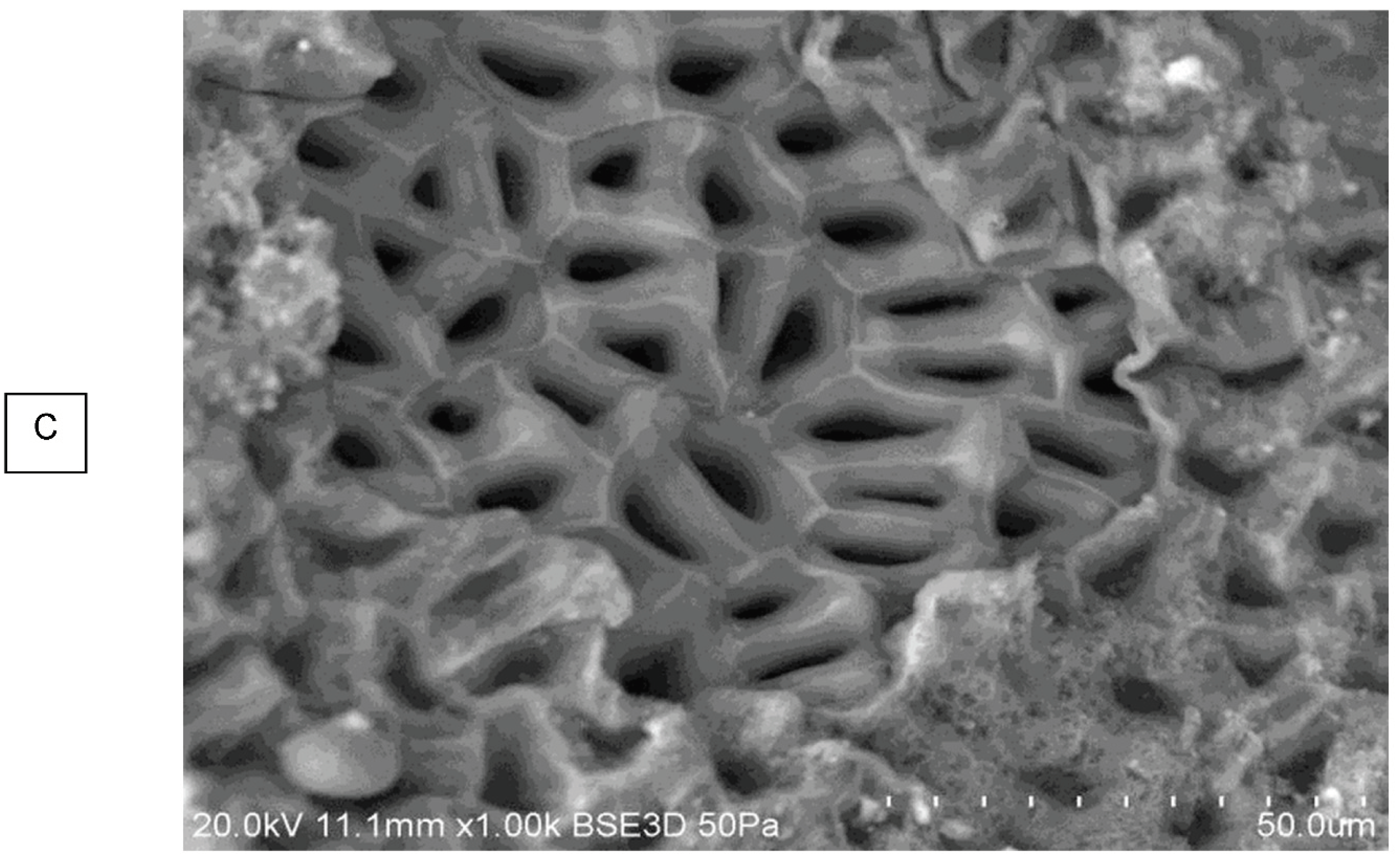

SEM/EDX technique was also employed to visualise the porous structure and to determine the pore size and the elemental composition of the biochar samples, and to assess their changes with the biochar production conditions. As seen in

Figure 16 and

Figures S6–S10), distinct morphologies of increasing porous structure are present.

The represented microscopic honeycomb like structures, typical of fibrous plant materials, are present in the PL biochar from the wood shavings used as bedding material. These microstructures evolve in shape and complexity as the torrefaction temperature is increased. The TOR 600 sample, for example, shows a very regular pore structure, but still has a wide range of pore size, from 4.2µm to 12.3µm (

Figure 10 A).

Along with the external macroporosity between the biochar’s particles and the residual macroporosity based on plant cellular structure shown in SEM images, a pyrogenic nanoporosity develops within the solid biochar volume and increases with production temperature but constitutes only a small portion of total porosity, even in higher production temperature biochars (Gray et al., 2014). What is more, the pyrogenic nano-pores are formed because of chemical changes at higher pyrolysis temperature, higher than 600°C, which was the maximum torrefaction temperature used to prepare the samples in this study.

Due to this reason, our study focused mainly on the macroporosity of the biochar samples, which is a key parameter influencing their water uptake.

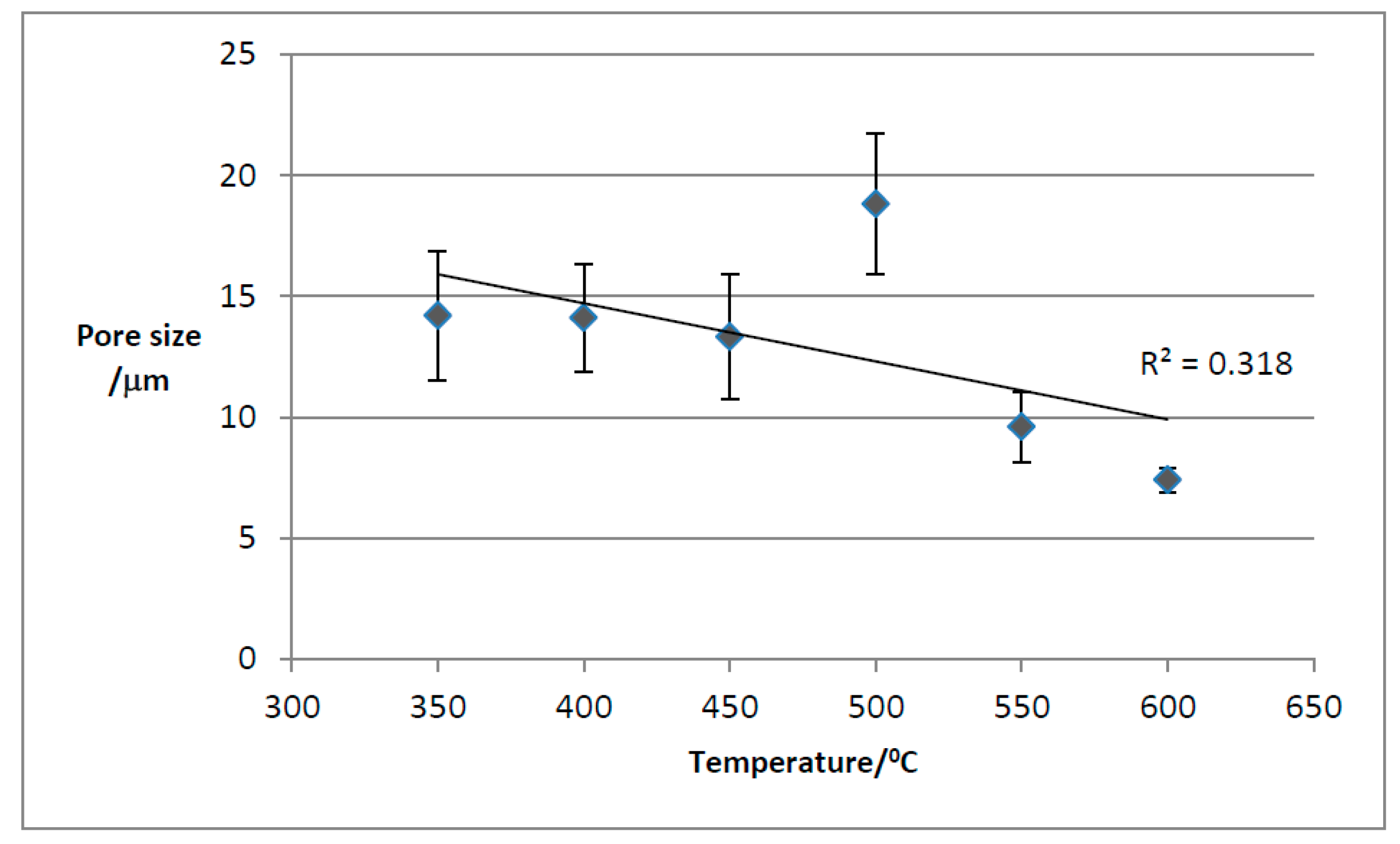

Using the SEM software, the pore size was directly measured.

Figure 17 presents the variation of the mean pore size with temperature.

Mean pore size decreases with torrefaction temperature as expected but TOR 500 seems anomalous. In fact, there are many problems with this method of measuring pore size. It is often difficult to decide where the maximum diameter is, as this involves subjective judgement. Also, some pores are seen in oblique view so that the measurement is larger. Most studies which find a decrease in pore size with temperature are considering single feedstock (Gray et al., 2014). One of the main features of poultry litter is its heterogeneous nature. Pore size is linked to the cell size of the feedstock - here there are many different plant species present, including grasses and wood shavings as well as inorganic material. The SEM images and EDX composition of such an inorganic structure on TOR 350 are presented in

Figure 18. Its elemental analysis shows very little carbon suggesting its inorganic nature. It looks mineral and contains both calcium and potassium at high levels with magnesium and sodium also present.

The heterogeneity of the PL means that not all SEM measurements are from the same material, thus the observed variation of morphology. However, there are some advantages of the SEM direct measurement of the pore size method. The pores are seen, so the wide variation in size, in even a single site, can be seen and measured.

In a heterogeneous feedstock like PL it potentially allows the contributions of different materials to pore size to be identified. It is also possible to see how the pores are formed from cell walls. Perhaps a more representative measurement of pore size would use only one type of pore, such as what will be called a “true honeycomb”, as seen for TOR 600 (

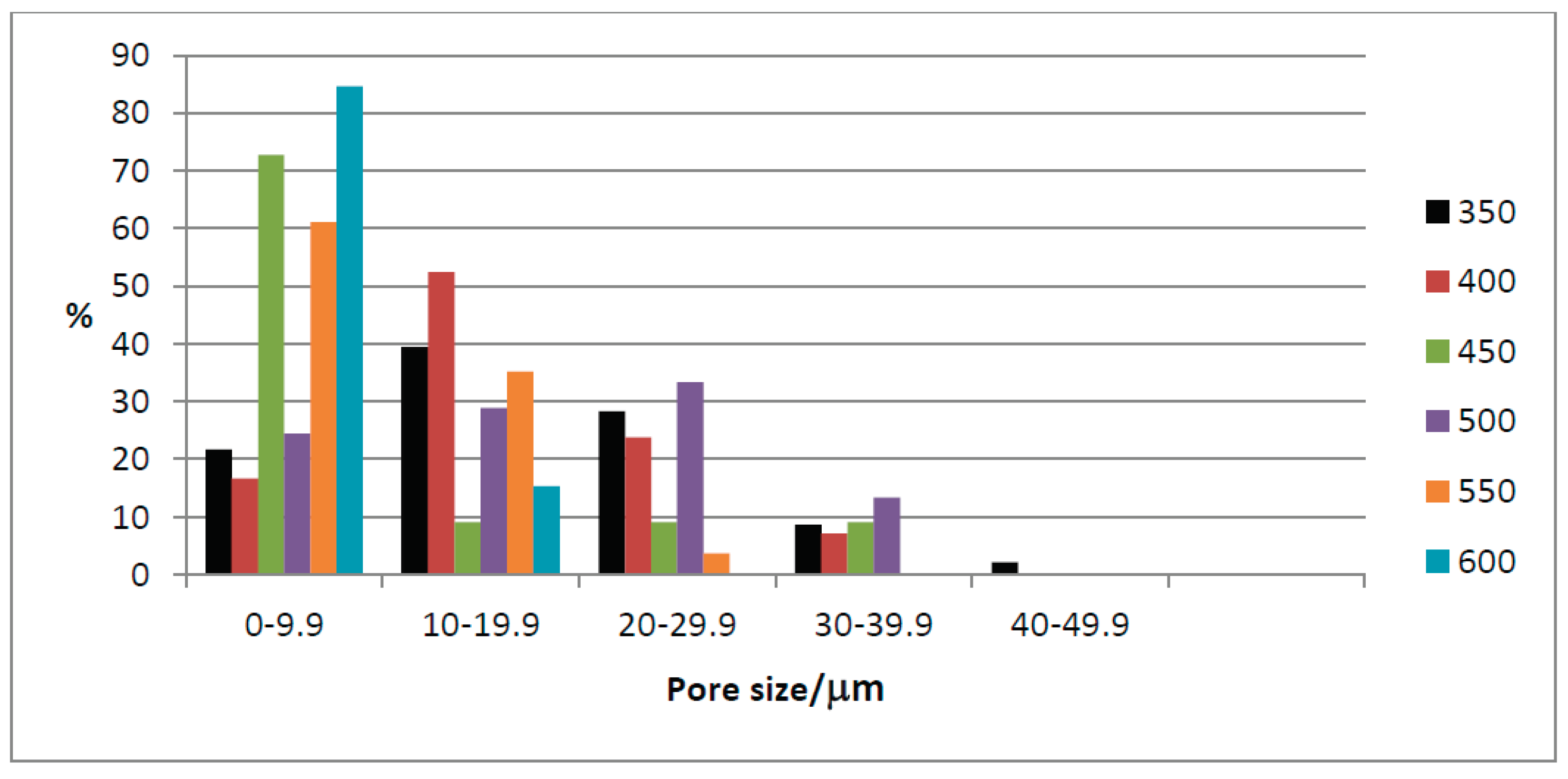

Figure S10B). The outer layer of plant material has been lost, exposing the cellular structure. The SEM pore size distribution measurement results are presented in

Figure 19.

TOR 350 has the widest range of pore’s sizes and the most frequent size is between 10 - 19.9µm. TOR 600 has a small range, and the most frequent size is 0 - 9.9µm. TOR 500 seems anomalous with a peak frequency at 20 - 29µm.

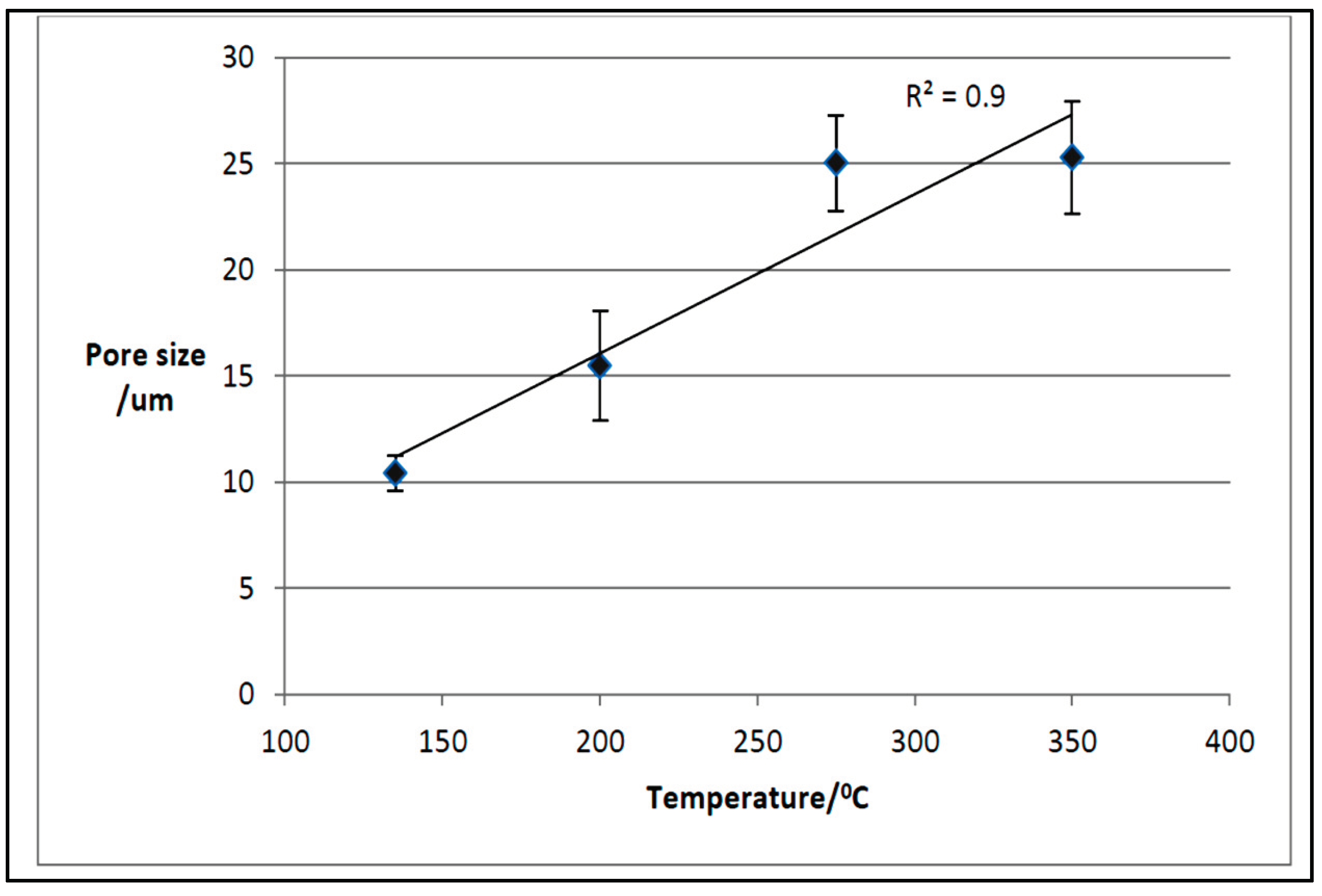

As for the TF biochar samples, SEM measurements showed that the mean pore size is increasing with temperature (see

Figure 20), which was an expected result as well. Since the poultry litter feedstock was a mixture of wood, barley, wheat straws, feathers, chicken excreta, and spilled feed etc., the microscopy images of TF samples show, as for the TOR samples, the presence of different types of biochar particles of varying size and morphology, which led to external pores, i.e., those pores between the biochar particles, of different sizes. The residual macroporosity is formed by the evolution of volatiles from the solid during thermal degradation of the poultry litter. Knowing that the corresponding temperatures for maximum decomposition of hemicellulose and cellulose are 300°C and 355°C, respectively, while lignin decomposition begins at about 280°C with a maximum rate occurring between 350 and 450°C and the completion of the reaction at 450 and 500°C, the increase in the pore size with temperature for the TF sample is most probably due to the volatilisation of hemicellulose and cellulose within the temperature range used in the tube furnace.

As the temperature of the conversion of poultry litter to biochar increases to produce the TOR samples, the pore size decreases since almost all the volatile compounds were lost at temperatures around 350°C.

There is a slight difference between the mean pore size for TF 350 and TOR 350, 25µm compared to 14µm. It might be due to the different amount of poultry litter used to obtain the two samples: two grams were used for the TF samples production, while for the TOR samples, 1kg of poultry litter was used, with the heat transfer for carbonisation being faster for surface samples (TF) than that for the bulk samples (TOR).

Figures S11–S14 show the SEM images and pore size measurements of the TF samples. There is still a wide range of pore sizes in each temperature as in TOR samples. For TF 135, the residual macropores are not very wide, some of them not completely open, so the surface area and volume, respectively, of the pores is low (

Figure S11). As the conversion temperature is increased at 200°C, pores with different sizes and appearance (far more open), similar to those observed for the TOR samples, are detected along with pores more likely as those on the TF 135 sample (

Figure S12).

At higher temperatures, i.e., 275 and 350°C, respectively, pores are now similar to those found in TOR samples.

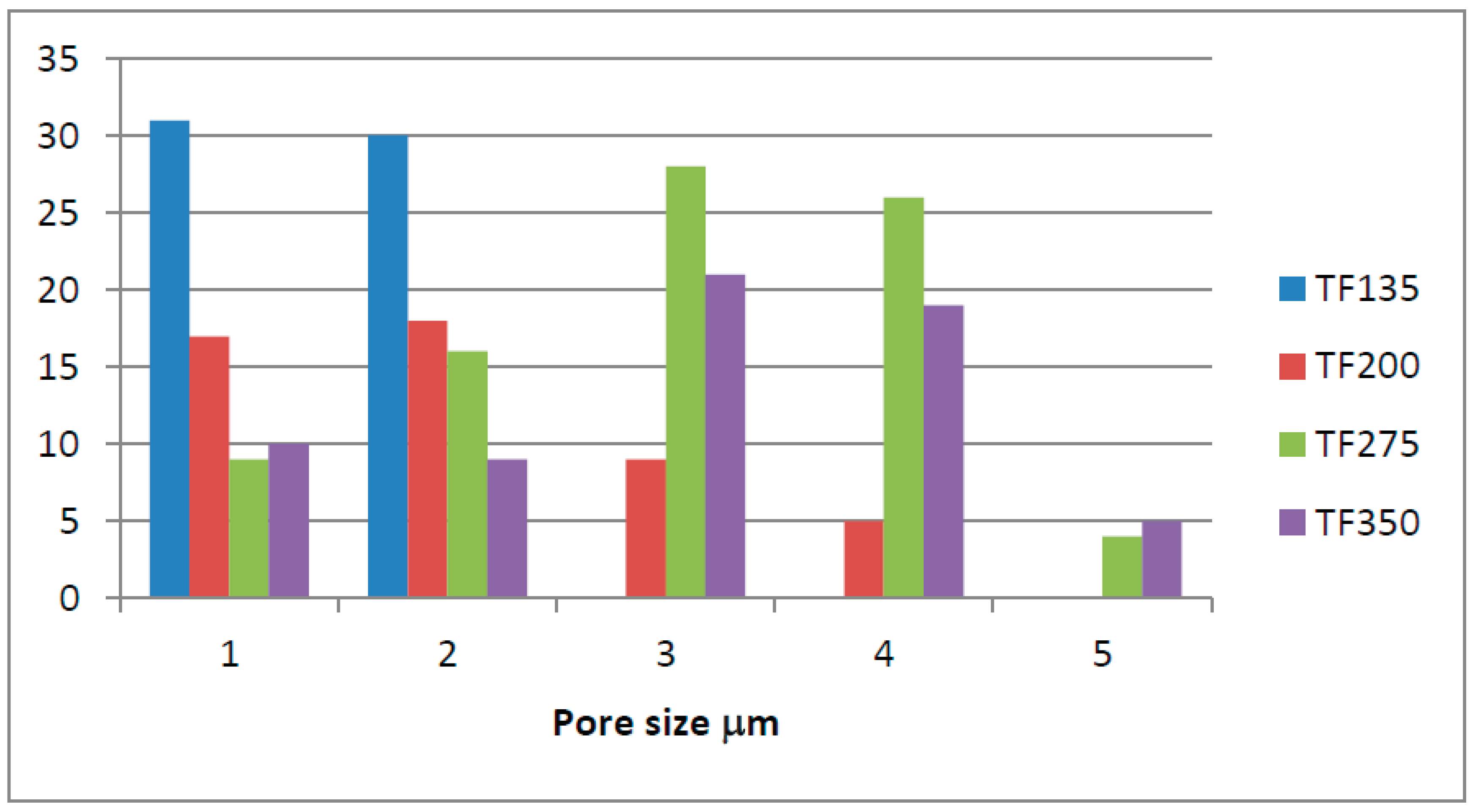

Figure 21 shows the frequency distribution of the pore size with temperature for the tube furnace biochar samples. There is a smaller range of pore sizes at lower temperatures, with most pores in the smaller size range for TF 135 and TF 200.

SEM images were taken for the HTC samples as well.

Figures S15-S18 show the morphology and size pores measurements of the carbonised samples. As seen in

Figure S15, for the HTC 80 sample, despite quite low temperature, there is a large amount of honeycomb morphology with many pores in the process of formation.

True honeycomb morphology, but with no cavity in the centre, was observed for the HTC 95 sample (see

Figure S16).

For the HTC 120 sample (

Figure S17), the honeycomb has a different structure to previous samples; these are arguably not true pores, or they are pores in the process of forming. The pores may be formed from a different plant material. It is also possible that the differences in pore morphology in HTC samples are due to the different decomposition of polymers in HTC, where hydrolysis is the most important mechanism (Libra

et al., 2011). The difference could also be due to pressure although this is a low-pressure sample (2bar).

If they are pores in the process of formation, a higher carbonisation temperature should be beneficial. Therefore, an extra HTC biochar sample was prepared at 221°C, HTC 221.

Figure S18 shows the SEM micrograph and pore size measurements for this sample. The microscopic pore morphology seems to be improved but there still are closed cavities. Similar observations were made over PL hydrochars obtained at temperatures of 150 and 175ºC, respectively; SEM micrographs showed incomplete decomposition and a corrugated surface with holes (Ghanim et al., 2016).

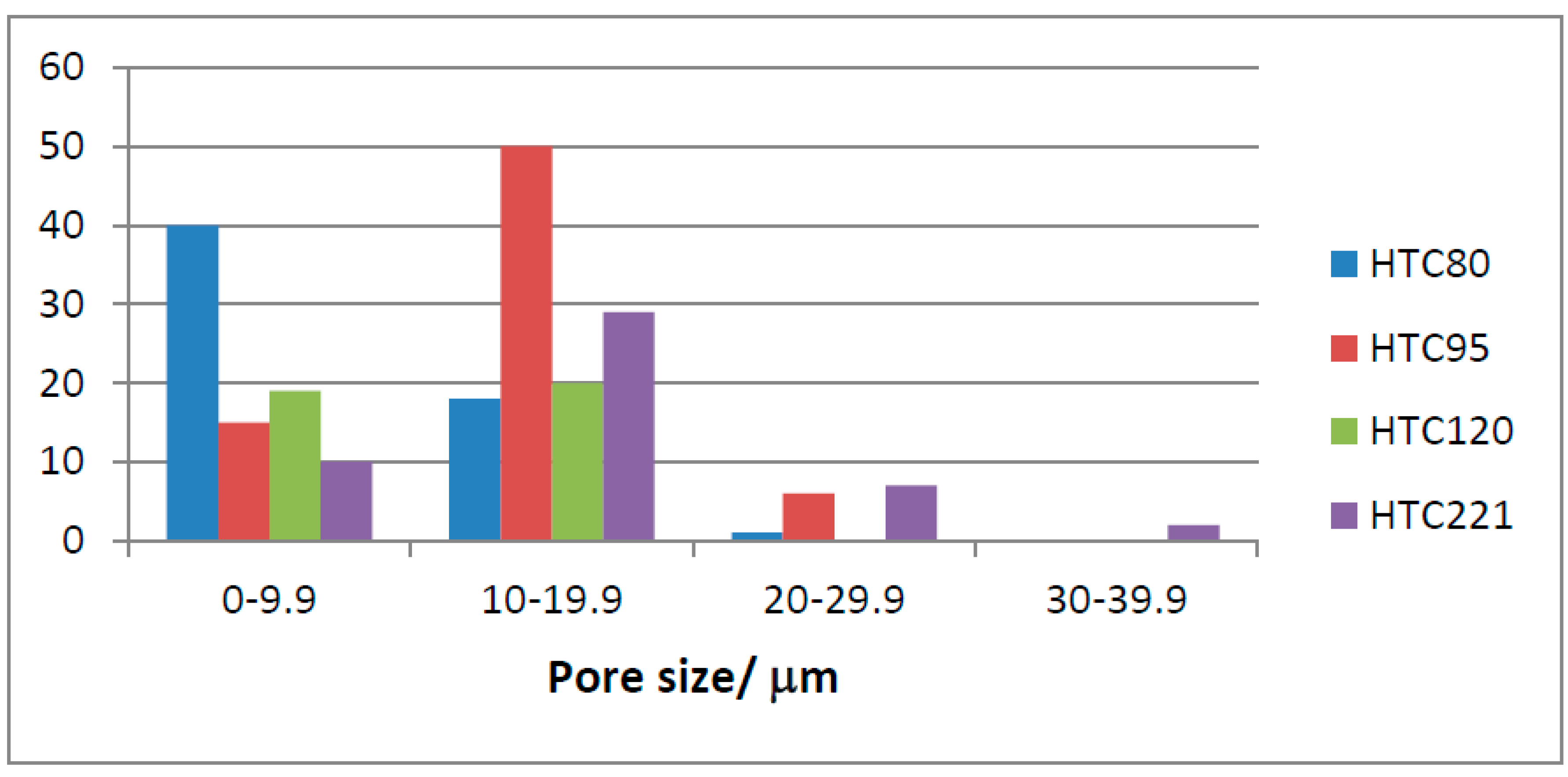

As expected, the mean pore size of the HTC samples (slightly) increases with temperature, from 10µm at 80°C to 15µm at 221°C.

Figure 22 presents the frequency distribution for the HTC samples’ pore size against temperature showing a lower range than for the torrefied material with very few pores 20µm or above. However, HTC 221 has the highest number of large pores. HTC 80 and HTC 95 are quite similar, but HTC 120 appears different. This could simply be sample variation; however, HTC 120 was prepared at a lower pressure of about 2bar, as opposed to up to 20bar for other points. This might suggest that pressure is an important factor in pore size.

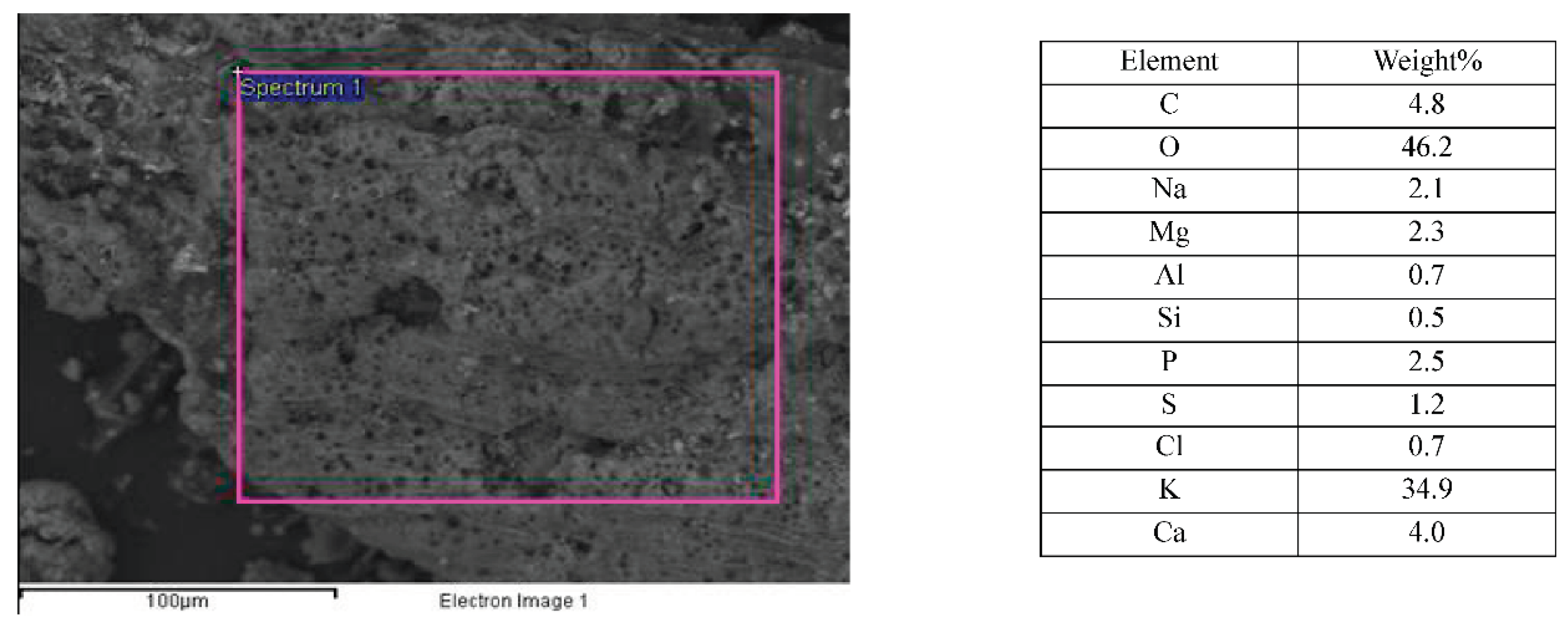

The elemental composition of the poultry litter biochars is another key parameter in their application as soil amendments. As mentioned above, PL biochars are heterogeneous materials, with complex structure and morphology. Therefore, a heterogeneous composition is expected as well. First, SEM/EDX measurements were used to assess the elemental composition at surface and subsurface level (about 1micron depth) of the different biochar’s samples prepared in this study.

Figure S12 shows the SEM images and EDX results of the TF 200 sample, as an example for the heterogeneous nature of the PL biochar’s samples.

The elemental composition of the torrefied samples was measured twice in a six- month time interval. EDX results show significant difference in composition from the fresh biochars to the aged ones (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

This difference is less obvious for low temperature chars. Thus, results for TOR 350 are quite similar. However, at higher temperatures there are big differences. In TOR 600 carbon has dropped from 70% to 47% whilst oxygen has gone up from 22% to 28%. The most likely explanation is that the stored chars have taken up water, so oxygen increases. This alters all the percentages, but is most obvious for the largest element, carbon. This explanation is supported by the hydrophobicity experiments which showed that the low temperature biochars take up little water compared to the high temperature ones.

The mean EDX composition of the TF samples is given in

Table 6.

As for the HTC biochar samples, the EDX measurements, shown in

Table 7, reveal that carbon decreases slightly and oxygen increases slightly above 80°C, but there is little change after this temperature. All other elements are present at lower levels and seem to increase slightly with temperature from 80°C but after this stay relatively constant. This is because the chars lose water and hence weight so the solid material is present at a lower level thus elements appear to increase. All minor elements are below 1% apart from Ca and so cannot be considered reliable. The tolerance of the system according to Oxford instruments is 0.1% but below 1% the peaks should be checked manually, which was not done. The higher levels of Ca may mean that Ca present on the surface is not water soluble. K shows an increase, but it is not significant and is very small compared to torrefied chars. This is presumably because the K is present as a soluble salt and dissolves into the surrounding HTC liquor.

The bulk composition of the biochar samples prepared in this study was measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), with the purpose to assess the presence of potentially toxic elements (heavy metals) such as Cu, Pb and As. Both methods were considered as the concentration of the heavy metals in the biochar samples determined by AAS was very low and, as such, ICP-MS was then used, as its sensitivity is better. What is more, using the two techniques allows an accuracy check to see if the two give similar values as the same total digestion was used for both. Comparative results for two TOR samples, TOR 350 and TOR 600, respectively, are shown in

Table 9.

Table 8.

AAS and ICP-MS results for TOR 350 and TOR 600 biochar samples.

Table 8.

AAS and ICP-MS results for TOR 350 and TOR 600 biochar samples.

| Element |

TOR 350 |

TOR 600 |

| AAS (ppm) |

ICP-MS (ppm) |

AAS (ppm) |

ICP-MS (ppm) |

| Fe |

1.11 |

ND |

3.41 |

0.17 |

| Ni |

0.14 |

ND |

0.05 |

0.00 |

| Cu |

0.40 |

0.16 |

0.48 |

0.09 |

| Pb |

ND |

ND |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Cd |

ND |

ND |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Zn |

1.09 |

0.79 |

1.22 |

0.31 |

| Cr |

ND |

ND |

0.00 |

0.00 |

The values are the same order of magnitude, but not identical. Iron is probably more accurate using AAS, but the other values in AAS are below the lowest standards. The calibration curves are not necessarily linear between the lowest standard and zero, so machine readings are estimates and may not be reliable. However, calibration curves were produced for lower standards and do show a linear relationship between zero and the lowest AAS standard for most metals. With such low values and only one reading it is impossible to determine if temperature has any effect on the concentration of these heavy metals. Another study found that Cd was below detection as it was found in this study and the trend was the same with Zn present at the highest level, followed by Cu - other values were higher possibly because a different digestion method was used. This study also showed a concentration effect in the char with double the values in the char compared to the PL (Farrell et al., 2013).

Taking into consideration the above findings, ICP-MS was used to characterise all other samples (see

Table 9 for the results).

Concentration levels in the low temperature chars are not much different to those in PL. However, at higher temperatures, levels of magnesium, manganese and aluminium increase. This is presumably a simple concentration effect. Standards were taken through the whole method to give an indication of both method and machine error. Errors are due to dilutions, variable loss of water during reflux, and metals taken up from anti-bumping granules, nitric acid and glassware. This gave a total error of about -1% for Cu, -7% for Zn and Ni, -10% for Cd and -35% for Fe. Levels of most metals are low and are very close to detection limits so values may not be accurate. As expected, there is good agreement between the 350°C results for the TF and those for TOR. The highest values were for Ca, Mg, Na and K, but these are all very susceptible to environmental contamination and the blank is high for all four. However, K shows a very different trend. The other three elements increase and then level off, presumably this is an artefact caused by the fact that the char weighs less so the percentage for a given weight is higher. K drops sharply, which may be important and therefore will be checked using a flame photometer; Zn, Al, Mn and Cu, though present at lower concentrations, show the same trend as K.

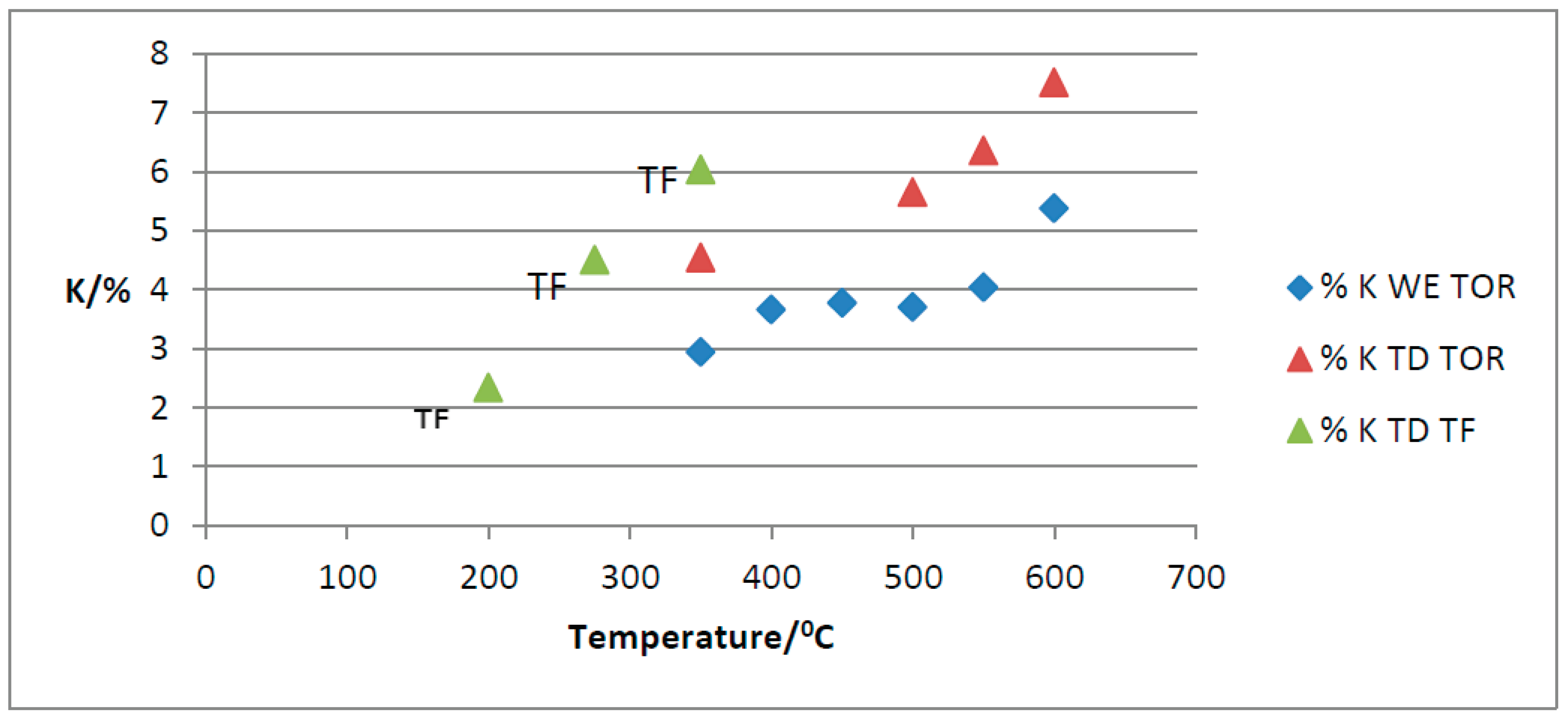

As KCl crystals have been found on the surface of the char it is important to know K levels, therefore the flame photometer was used on both water-extracted and total digestion samples.

The results are presented in

Figure 23. As can be seen, over 60% of the total K in the TOR samples is water extractable (WE). This is important in terms of plant nutrients as water extractable K is available to plants, but it may also be leached before it can be used. Soluble K may also affect germination as it is mainly on the biochar surface. This was tested using a KCl solution in the germination test. Other studies have found lower levels of water extractable K of about 46% at 300°C going up to 49% at 600°C (Song and Guo, 2012). A similar trend was observed, with WE % staying fairly constant until 550°C when it increases, whilst in this study the increase was observed above 550°C. TF and TOR biochars show an increase in both water extractable and total K with increased production temperature. The TF 350 value is slightly higher than the TOR 350 value.

The HTC material has little K presumably because soluble K has been extracted into the HTC liquor. Flame photometry measurements showed a maximum of 1% K (TD) for the HTC 120, while for the PL, the value was 2.3% or 22.9mg g-1. This value is lower than the published data of 41.8mg g-1 for raw PL (Song and Guo, 2012). Another study measured between 5.65% and 7.59% total K in PL; again, the value measured in this study is lower (Agblevor et al., 2010), as the source of PL is different.

3.4. Effect of production method and temperature on samples’ thermal stability

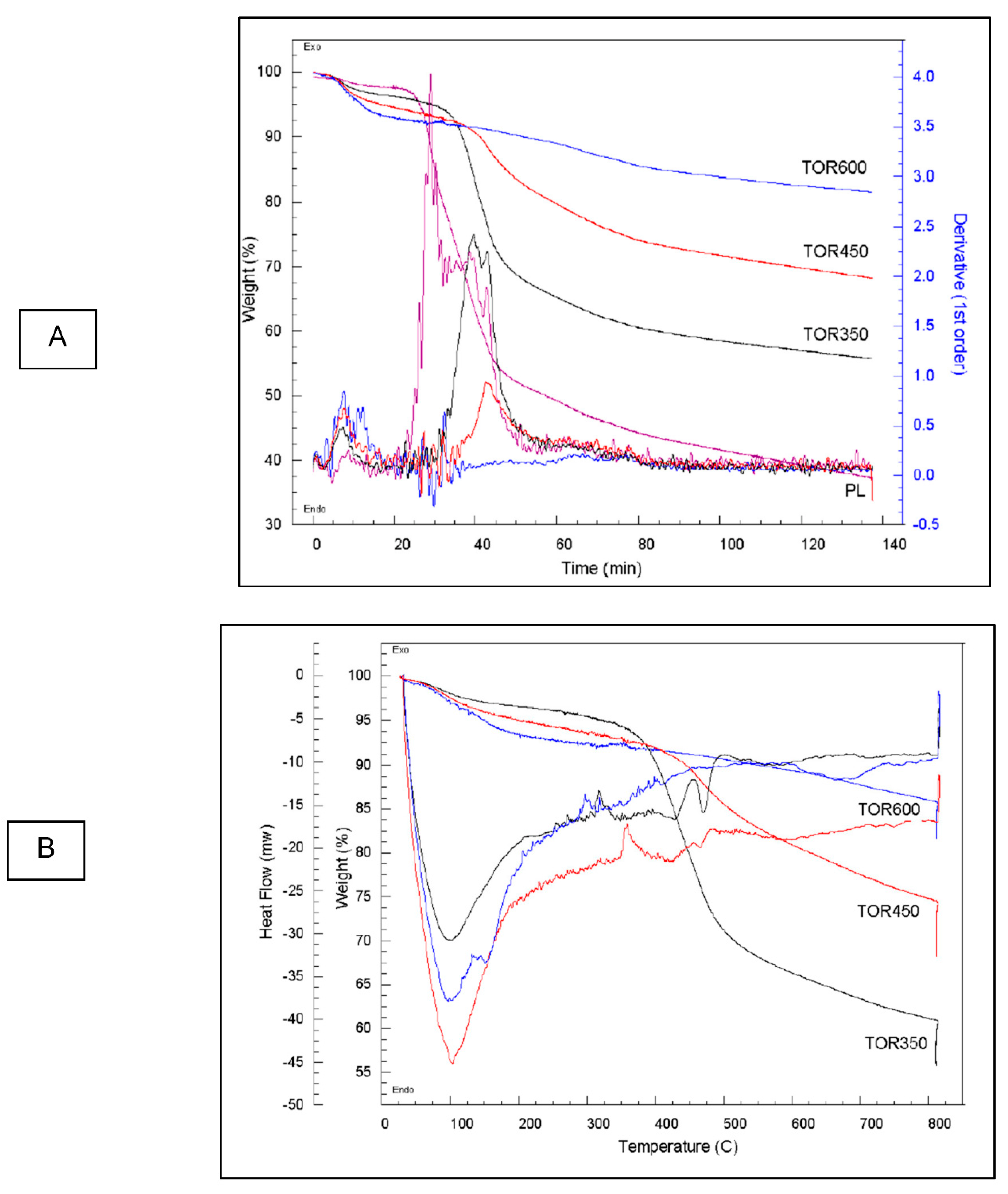

As it is well-known, the conversion of poultry litter, a nutrient-rich organic residue, into biochars is an alternative to stabilize its carbon through conversion to aromatic and recalcitrant forms, because the ability of biochar to retain carbon in relatively stable forms is considered as one of its most important properties, either for carbon sequestration or soil conditioner use. However, despite the widespread expectation of high biochar stability in the environment, a considerable portion of its carbon content is labile, and it can be decomposed under its usage conditions (da Silva Carneiro et al., 2018). The evaluation of the biochars’ carbon stability was done by TGA analysis under inert (Ar) environment at 800°C.

Figure 24 shows the TGA curves for PL and three of the TOR samples, i.e., 350, 450 and 600, respectively. There is a slight loss of weight at a consistent rate for all chars up to 150°C due to water loss. Although the chars and PL have previously been heated, so should be dry, they have been stored for 6 months so will have taken up water. It is noticeable that TOR 600 loses the most weight of the chars in this initial phase, presumably because higher temperature chars have a larger surface area and are less hydrophobic so take up more water whilst stored. The second weight loss of volatile substances (organic carbon) occurs at different temperatures for the different samples. It starts at about 280°C for PL, 370°C for TOR 350, 430°C for TOR 450 – all fitting well with the fact that these chars have already lost volatiles up to their torrefaction temperature. There is no steep drop for TOR 600, just a smooth curve, showing it has already lost most volatiles. TOR 350 loses the most weight of the TORS as would be expected as it has not lost as many volatiles due to torrefaction. The last section is the further weight loss during the 60 minutes residence time. The final weight value would be expected to be residual ash.

As for the first derivatives of thermograms, the first small peak at 100°C is due to water loss (Kim et al., 2012). Then the derivative shows a major exothermic reaction starting at 300°C for TOR 350 and a lower peak at 430°C for TOR 450. TOR 600 does not show this peak indicating that this component has already been lost during torrefaction. The PL peak starts at about 210°C and it is higher than the TOR 350 peak. The peak for TOR 350 may be a double peak, with the second peak coinciding with the exothermic heat flow peak at 450°C. The peaks are caused by the thermal degradation of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin. The 300°C peak is hemicellulose, 350°C peak is cellulose and lignin peaks at 450°C (Kim et al., 2012). Chen and Kuo, (2011) studied the thermal degradation of pure hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin, xylose and glucose. They found that torrefaction of hemicellulose at 230°C gave an exothermic peak. Hemicellulose contains oxygen having a general formula of (C5H8O4)n - this oxygen is used in thermal degradation. At temperatures below about 230°C some hemicellulose in the chars will have been broken down during the torrefaction process; at higher temperatures, above 310°C, the hemicellulose is totally broken down. For cellulose total breakdown occurs at 361°C. Lignin pyrolysis is an exothermic reaction and occurs at about 400°C. The peak in PL starting at 210°C is hemicellulose. In TOR 350 hemicellulose will have broken down so this peak is not seen, but cellulose and lignin have not broken down. Consequently, when the char is reheated in TGA, the weight loss is due to the decomposition of cellulose and lignin. For TOR 450 all components should have been lost and further weight loss should be due to inorganic components, such as carbonates. However, there is a larger drop in TOR 450 at a higher rate than for TOR 600, suggesting that not all organic components have been lost. This suggests that the components left in the different temperature chars are different. Their properties as fuels will therefore be different as shown by the decrease in calorific value (CV) with increased production temperature. Xylan is a component of hemicellulose and it shows a decrease in weight prior to 100°C so it may be that the drop-in weight previously attributed to water might be due to xylan. However, this would not fit with TOR 600 losing the most weight as it will have least xylan since the pyrolysis temperature for xylan is 300°C, so should not be present in the TOR 600.

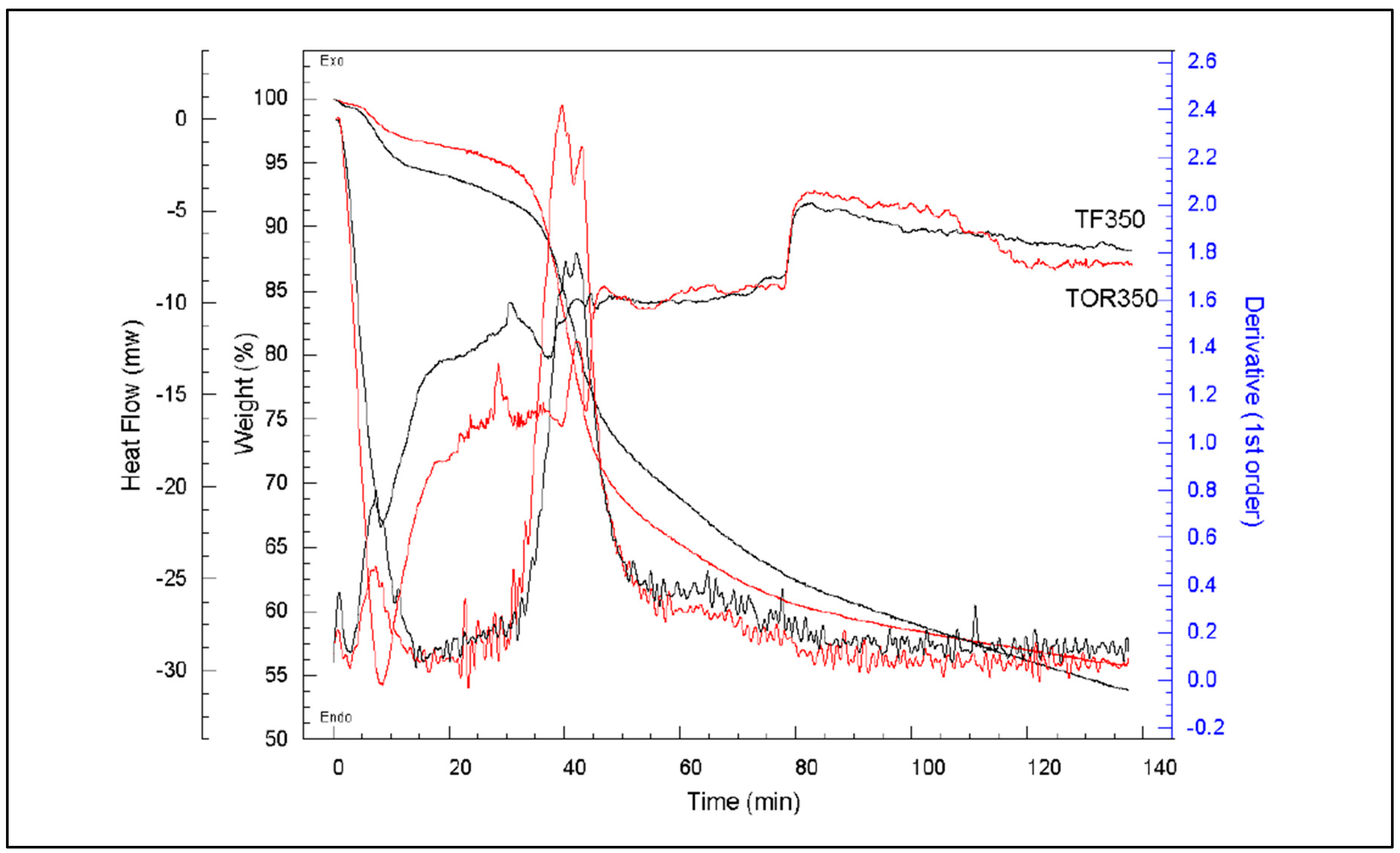

The same decomposition behaviour was observed for the TF samples.

Figure 25 presents the TGA curves for TOR 350 in comparison with TF 350. As can be seen, TF 350 results agree well with those obtained for the TOR 350; this would be expected as they are produced at the same temperature. Heat flows and derivatives are very similar however, TOR 350 shows a higher peak which starts slightly earlier. Also, TF loses more weight at above 100°C and then drops more gradually so, by the end of the process, the weight loss is very similar.

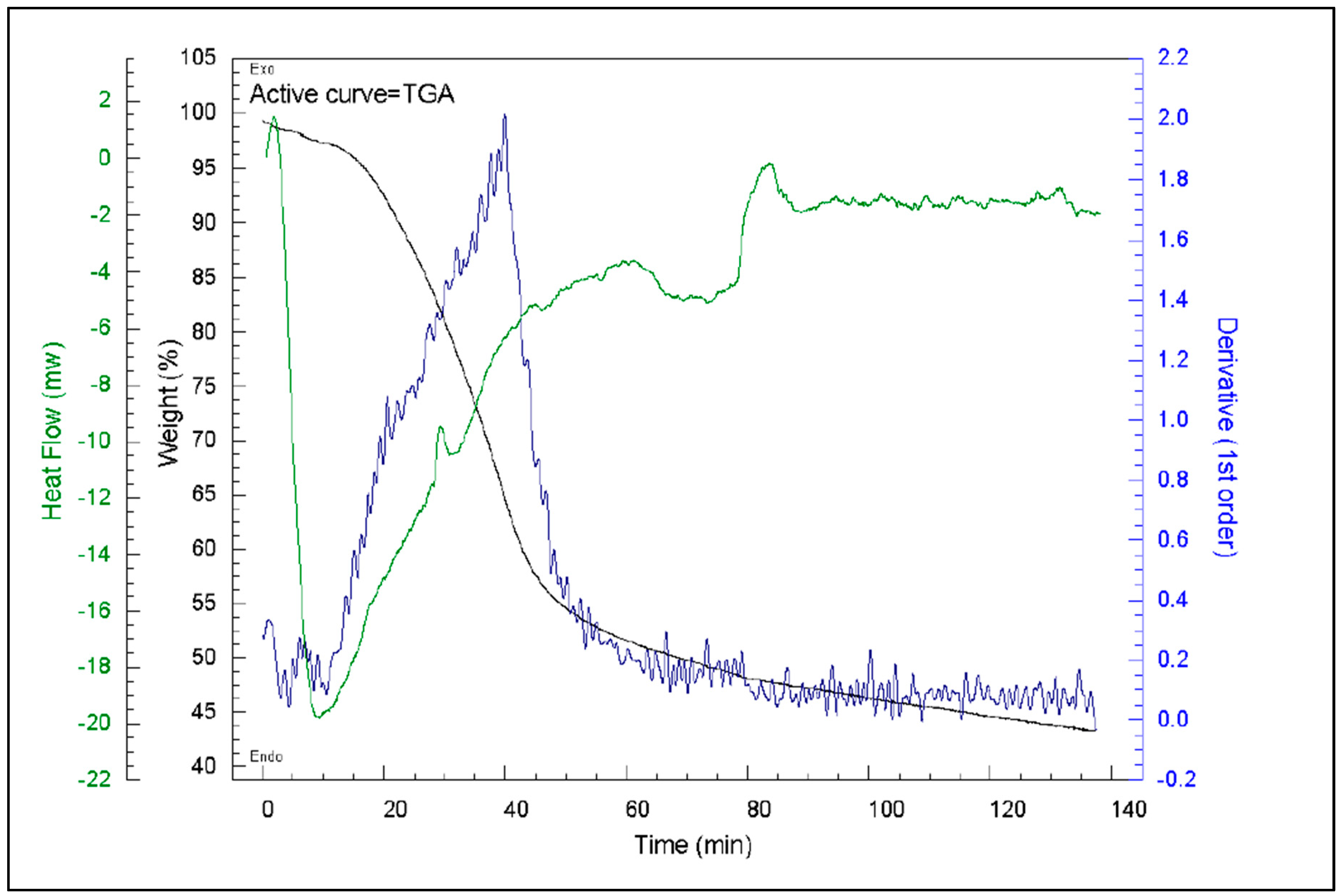

HTC biochar samples showed a different behaviour although the feedstock decomposition is dominated by reaction mechanisms similar to those in dry pyrolysis, which include hydrolysis, dehydration, decarboxylation, aromatization and recondensation (Libra et al., 2011). However, the hydrothermal degradation of biomass is initiated by hydrolysis, which exhibits a lower activation energy than most of the pyrolytic decomposition reactions.

As seen in

Figure 26, the weight loss seems to be more gradual than for the torrefied samples, with less of a distinct step change. The very broad derivative peak explains why there is not such an obvious step change.

Therefore, the principle biomass components are less stable under hydrothermal conditions, which leads to lower decomposition temperatures. Hemicellulose decomposes between 180 and 200°C, most of the lignins between 180 and 220°C, and cellulose above approximately 220°C. So, the bulk of the polymer left will be cellulose (Libra et al., 2011). The 400°C peak is presumably lignin that has not yet decomposed, but the broad peak up to 300°C is cellulose. There is less hemicellulose present.

It is possible to attach a MS to a TGA device to see what gases are evolved at the different temperatures (Florin et al., 2009). The results for PL suggest that the main gas lost at 375°C is water, so dehydration reactions are occurring, whilst the second peak at 450°C coincides with CO2, higher hydrocarbons (C2H2+, C2H3+) and aldehydes. This gives more information about the reactions occurring and the gases being lost during torrefaction.

The weight loss for the TOR, TF and HTC samples measured in this study is presented in

Table 10.

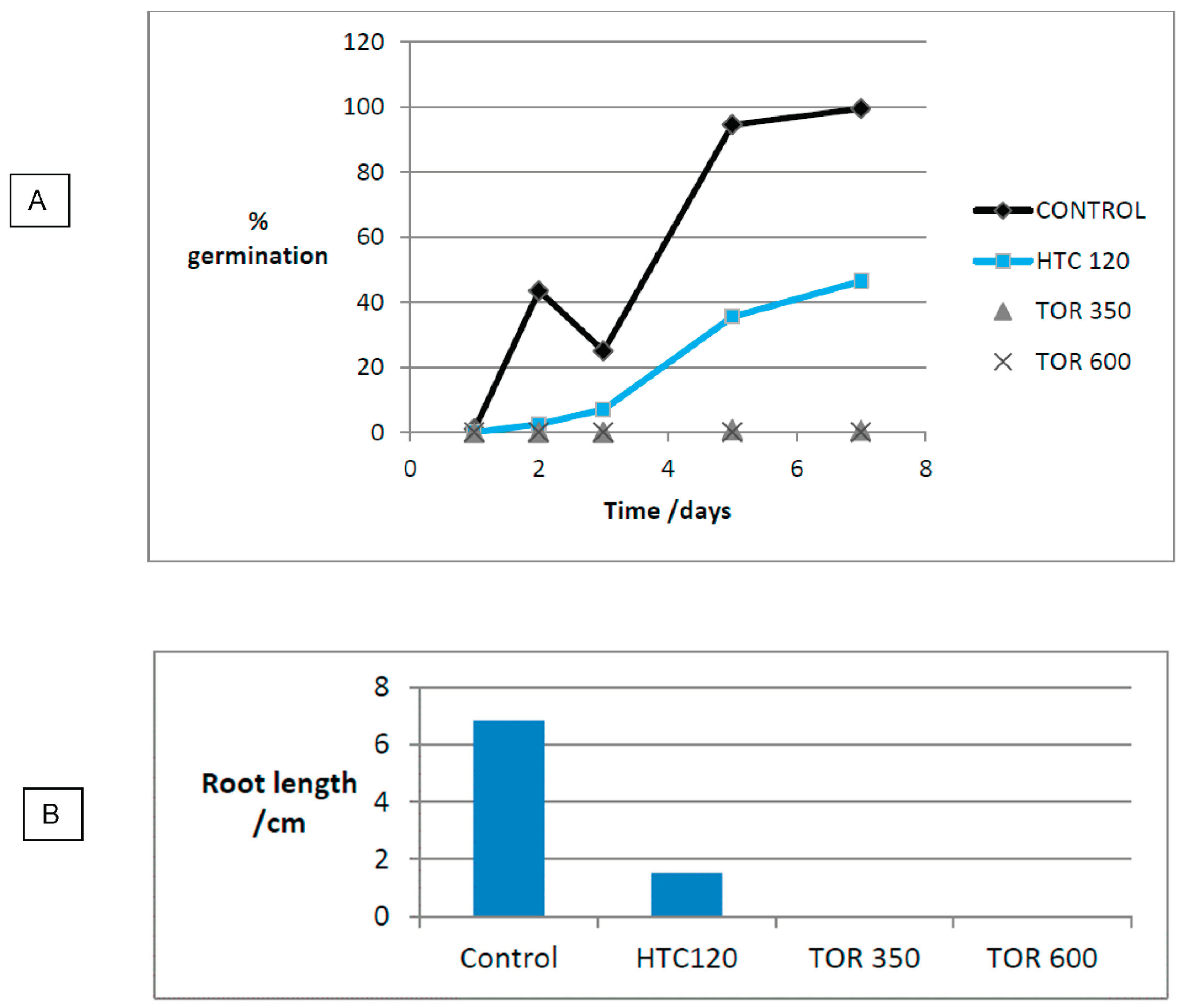

3.6. Effect of Production Method and Temperature on Germination

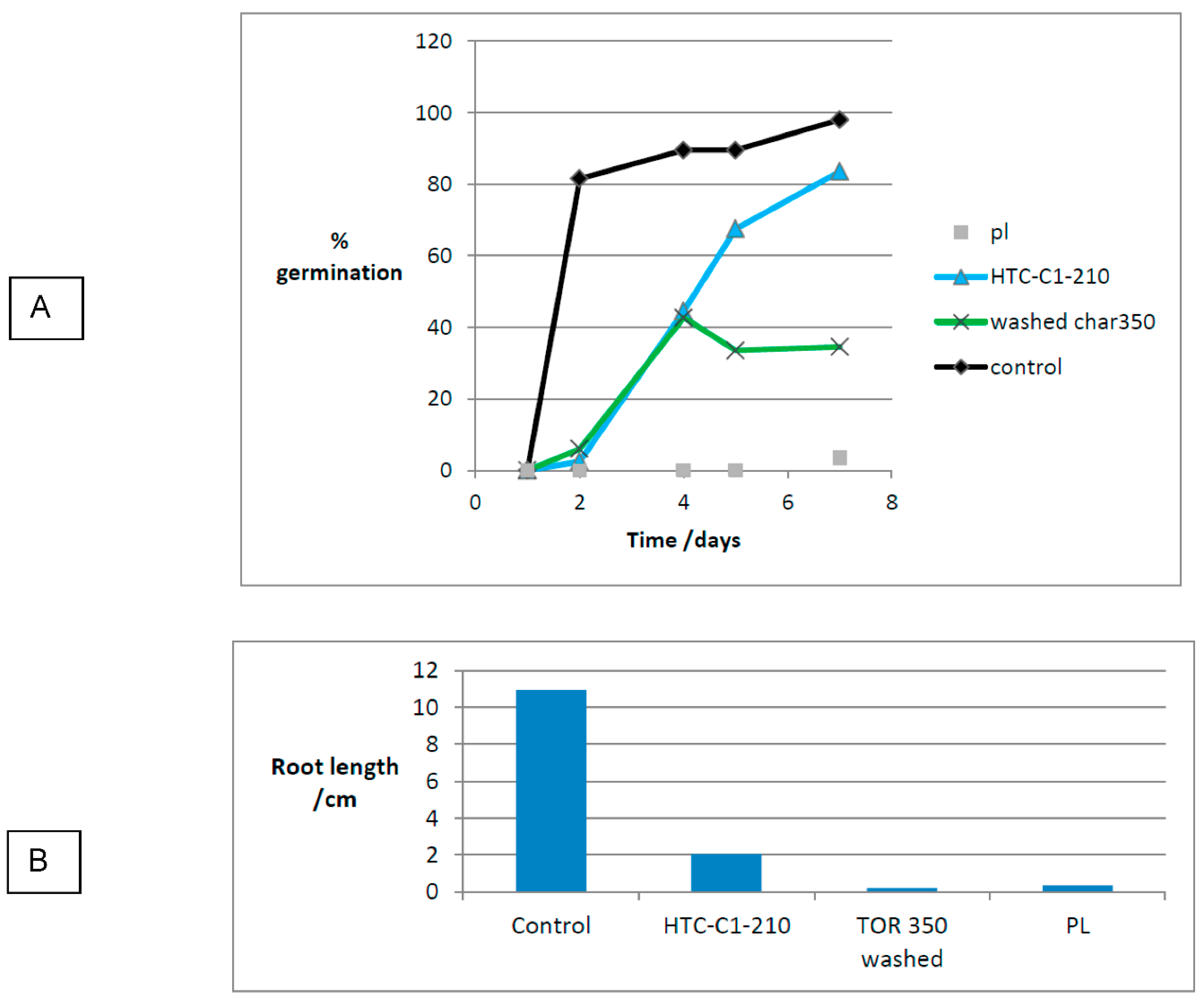

Germination was tested in two separate experiments. The data cannot be amalgamated as these experiments were not carried out in controlled environmental conditions. Consequently, germination must be compared to the relevant control (

Figure 28 and

Figure 29).

For the first experiment, as seen in

Figure 28.A, TOR 600 biochar sample showed no germination and TOR 350 showed only minimal germination. HTC 120 showed germination although germination started later and gave a lower value than the control at 7 days. The anomalous reading on day 3 for the control was due to the plate drying out on a very hot day. 2ml DI water were added to all plates immediately and then 1ml of water was added each time they were measured. Observation suggested that although germination occurred in the HTC 120 root growth was severely inhibited and roots seemed more twisted than the control. Possibly the roots could not grip the substrate. Consequently, at day 7 as well as measuring total germination root length was also measured (

Figure 28.B). There was considerable mould/fungal growth on HTC 120 which started on day 4.

The ANOVA for this experiment is extremely significant with a P value of 8.9 x 10-19. This does not detail which results are significantly different, although obviously the two chars are significantly different to the control. However, a t-test was performed to show which results were significantly different to the control. This is important to test whether differences between the hydrochar and the control are significant.

For the second experiment the following solid substrates were used: PL, HTC-C1-210 and washed TOR 350 char against the control.

Figure 29 presents the germination results. It was good germination for the HTC-C1-210 sample (84%) and washed TOR 350 sample gave some germination (34%). There was little germination in PL and the few seeds that germinated were not observed until day 7, showing a major delay in germination. Root growth was low in HTC-C1-210 and severely inhibited in TOR 350 washed and PL. Mould growth on PL started on day 4 and by day 7 the plate was almost completely covered. Germination was variable in PL with one plate showing 28% and another zero. The variation did not seem to correlate with mould growth. There is still a significant difference in the ANOVA for this experiment with

P < 0.05 (P =1.24 x 10

-6). Again, a t-test was performed to show whether the difference between PL, HTC and control were significant.

The Student’s t-test shows all results are significantly different to the control at P <0.05.

All the germination results can be compared using a germination index (GI) as shown in

Table 11.

The literature suggests that biochars do not inhibit germination, but that hydrochars do inhibit germination (Busch et al., 2013). These results appear to contradict this, with germination occurring in hydrochars but not in biochars. However, the high germination index in HTC 120 can be explained by the fact that it was a low temperature hydrochar that had been washed. This washing should remove soluble substances and some toxic oils from the surface allowing germination. Initial seed germination is mainly dependent on water availability for imbibition and the hydrochar showed good water retention, allowing good germination. However, after initial germination, substrate toxicity is demonstrated as reduced root growth showing toxic substances still remain, even after washing. If there is no toxicity the roots should be white and show root hairs just behind the growing tip. Root growth should be fairly straight with a consistent diameter, reducing towards the root tip.

Germination in the TOR samples was almost completely inhibited. As stated earlier, this can be due to lack of water for imbibition by the seeds. As water was physically present, a lack of water for imbibition could be due to two factors. Firstly, the lower temperature chars are very hydrophobic and when water was added it formed discrete bubbles on the surface meaning the water did not disperse, consequently only some seeds had access to water (see

Figure 27).

However, hydrophobicity is more pronounced in low temperatures chars, whereas the high temperature TOR 600 showed poorer germination; indicating toxic compounds might be more important.

Secondly, physiological drought can occur i.e., water is present, but the concentration of soluble salts is so high that osmosis cannot occur into the seeds to allow germination. If it was simple lack of water that produced the lack of germination, then transfer of the seeds from the char to filter paper should allow germination. This did happen for TOR 350 where 21% germination occurred on transfer to filter paper, although germination had started on the char before transfer occurred. Full germination did eventually occur for those seeds where germination had already started.

Figure 30 shows cotyledon emergence, but the stunting of the root is clearly visible. The brown coloration on the root is also visible as is the lack of growth. The control shows the difficulty in measuring root growth as the root blends into the stem with no obvious discontinuity. This makes the actual measured values for root length estimates. If the testa is still attached this indicates the line between root and shoot. Also, there is often a colour difference from white to green at the junction. It is thought that the total lack of germination is due to toxic salts and physiological drought.

To test whether soluble salts were important in causing germination inhibition a sample of char was washed as for pH determination to provide a washed char and a washing extract. If the hypothesis is correct the washed char should allow germination, whilst the extract should inhibit germination. In experiment 2 the washed TOR 350 char did allow germination at 35% (

Figure 31). However, mean root length is still negligible indicating a two- stage germination/growth inhibition. Washing removes the first inhibition but not the second which could be due to bio-oils and tars deposited on the char. It is also still possible that it is hydrophobicity which causes the initial inhibition as the washed char was very wet. To investigate further the char should be dried after washing and then used in a germination experiment; however, this adds another variable as it means more volatiles will be lost. Some experiments have tried to separate volatiles and direct contact effects on germination inhibition (Buss and Mašek, 2014). This would have been an interesting experiment to perform as volatiles are definitely present on the TOR samples as evidenced by smell. A further experiment was performed where seeds were placed on biochars that had equilibrated with a moist atmosphere in the hydrophobicity experiment. No germination occurred, probably due to insufficient water. However, as they were kept in a sealed box, volatiles could also be implicated.

In order to explain the germination results observed during the experiment 1, it was assumed that soluble salts, such as KCl, could be inhibiting germination. EDX showed about 10% of K present on the surface of chars, probably as KCl. So, a 10% solution of KCl was used in an extra experiment along with a TOR 350 wash extract. What is more, literature suggested that the hydrochar liquors are more toxic than the solids, so two liquor samples were tested, HTC 87 and HTC 250, respectively.

The KCl completely inhibited germination either through physiological drought or due to toxicity which supported the hypothesis.

The total lack of germination in the high temperature HTC extract and low GI for the low temperature liquor also supported the toxicity of HTC extracts. This liquor toxicity could be due to a number of factors. The liquor is acid (pH for HTC 87 is 3.27 while for HTC 250 is 4.57) which may be a problem because pH affects germination. Acidity also increases the solubility of many metals which can also cause germination inhibition, although levels of heavy metals (as shown by AAS) were generally low. There is also a complex mix of organics including phenols and PAH in HTC liquor.

TOR 350 and HTC 87 extracts show good germination at almost the same rate as the control although root growth is decreased in both with HTC 87 showing almost no root growth. Roots were so short they were difficult to measure. KCl and HTC 250 show no germination. The KCl seeds were washed and placed in deionised water after failing to germinate, but still did not germinate, suggesting toxicity as well as osmotic effects.

As stated above, the TOR 350 extract had no effect on germination suggesting that soluble salts do not inhibit germination. However, the extract was far more dilute (1:40) than concentration would be on the seeds. A second germination was performed at 1:20; this also had no effect on germination. It would be useful to perform a concentration sequence using higher concentrations.

In summary, biochars totally inhibit germination whilst hydrochars slightly inhibit germination. However, after germination hydrochars inhibit root growth. Washing of both biochars and hydrochars reduces germination inhibition, but root inhibition remains. It is suggested that the initial germination inhibition in biochars is due to the presence of soluble salts such as KCl. Root inhibition is probably due to insoluble organic compounds deposited on the char surface. Surprisingly PL also showed almost total germination inhibition. The fact that PL is used successfully as a fertiliser suggests that lower concentrations do not adversely affect plant growth; possibly the chars could be used as soil amendments if used in low concentrations.