1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the etiological agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that caused the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2022 [

1,

2]. Mixed infections may play an important role in the development of SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with other viruses may increase the risk of disease severity and pose challenges to the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of COVID-19. It was shown that 3 to 21% of COVID-19 patients were also infected with other viral respiratory pathogens [

3]. Approximately 12–14% of these co-infections are associated with rhinoviruses and enteroviruses, which can cause self-limited cold-like illnesses, severe pneumonia in the elderly and immunocompromised patients, as well as viral meningitis or encephalitis [

4,

5]. The coincidence of the COVID-19 pandemic and seasonal rhinovirus/enterovirus outbreaks could put a large population at high risk of contracting these viruses simultaneously. The features of the infectious process, clinical manifestations, disease severity and prognosis in patients co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and rhinovirus/enterovirus remain implicit and non-obvious (from worsening of the clinical course and outcome to significant improvement in prognosis) [

6,

7,

8].

Small animal models are essential tools for studying viral pathogenesis, transmission, immunology and co-infection [

9,

10]. The golden Syrian hamster models were usually used for SARS-CoV-2 infections. In SARS-CoV-2 challenge experiments, inoculated hamsters showed progressive weight loss with lethargy, ruffled fur, hunchback posture, and rapid breathing; recovery took place by 14 days after virus inoculation [

9]. The virus replicates to a high titer in the upper and lower respiratory tracts, and the 50% infectious dose in Syrian hamsters is only five 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID

50) [

10]. SARS-CoV-2 isolates cause pathological lung lesions, including pulmonary edema and consolidation with evidence of interstitial pneumonia. The Syrian hamster model is also the commonly used EV-A71 animal model. Suckling Syrian hamsters (7-day-old) consistently developed signs of infection such as closure of eyes, hunchback posture, reduced mobility and paralysis, progressing to a moribund stage between 3 and 4 dpi [

11].

The aim of this study was to investigate the features of the viral infection by simulating co-infection, both

in vitro and

in vivo, with SARS-CoV-2 and nonpathogenic strain LEV8 (live enterovirus vaccine) of coxsackievirus A7 (CVA7) [

12] or enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) pathogenic for humans, which is associated with the hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) and viral encephalitis [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cell Cultures

In early 2020, the hCoV-19/Russia/StPetersburg-64304/2020 (GISAID, EPI_ISL_428868) SARS-СoV-2 strain was isolated from a patient suffering from COVID-19 using Vero E6 cells. The coxsackievirus A7 strain LEV-8 (GenBank, JQ041367) and enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) strain Rostov (GenBank, KJ400360) were procured from the SRC VB “Vector” (Russia). Vero E6 and HEK293A cells were procured from the SRC VB “Vector”, and cells were cultivated using DMEM (BioloT Ltd., Russia) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, USA), penicillin (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Viral stocks of SARS-СoV-2, LEV-8, and EV-A71 were stored at −70 °C before use.

2.2. Animals

Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) of both sexes aged six to seven weeks obtained from the Center for Genetic Resources of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, SB RAS, was used in the studies. The experimental animals were fed a standard diet and had ad libitum access to water according to the veterinary legislation and requirements for humane animal care and the use of laboratory animals (National Research Council, 2011). The animal experiments were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the SRC VB “Vector”.

2.3. In Vitro Co-Infection

The effects of

in vitro co-infection were evaluated for simultaneous and sequential infections with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71. Vero E6 cells were cultured in 24-well plates and inoculated in triplicate either with both SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 simultaneously (MOI 0.1 ТCID

50 for each virus) or solely with LEV-8 or EV-A71 and 1 day later, with SARS-CoV-2 as well as with SARS-CoV-2 and 1 day later with LEV-8 or EV-A71. Cells mono-infected with SARS-CoV-2, LEV-8 or EV-A71 and mock-infected cells were used as controls. To determine the viral infectious titers and viral loads, the cells were collected 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h post-infection (for LEV-8 or EV-A71 pre-infection, cells were collected 24 h and 48 h post-infection; for SARS-CoV-2, 48 h and 72 h post-infection). The viral titers for SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 in Vero E6 and HEK293A cells, respectively, were determined using a TCID

50 assay as estimated by microscopic evaluation and by measuring cell viability in the formazan-based MTT assay as described previously [

14,

15].

2.4. In Vivo Co-Infection

Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 was studied using Syrian hamsters. The animals were randomly assigned to multiple groups (n = 9 animals per group). The Syrian hamsters were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (10

5 ТCID

50); challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (10

5 ТCID

50) and LEV-8 (10

6 ТCID

50); other group of animals were intranasally challenged with LEV-8 (10

6 ТCID

50), and, on Day 3, they were challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (10

5 ТCID

50). Furthermore, the Syrian hamsters were simultaneously intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (10

5 ТCID

50) and EV-A71 (10

6 ТCID

50). Pre-infection with EV-A71/3-days/SARS-CoV-2 was similar to that performed using 10

6 ТCID

50 EV-A71. Intranasal inoculation was performed by anaesthetizing the hamsters with isoflurane (Isothesia; Henry Schein Animal Health) and then inoculating the nostrils with the viruses in 150 µL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The control animals received PBS. After challenge, the hamsters were followed up and weighed daily. On Day 4 and Day 7 post-infection (for the LEV-8/3-days/SARS-CoV-2 and EV-A71/3-days/SARS-CoV-2 groups, this took place on Day 4 and Day 7 after the challenge with SARS-CoV-2), the lungs were collected from three hamsters from each group. Animal euthanasia was carried out using an automated compact CO

2 system for humane output from the experiment of laboratory animals (Euthanizer, Moscow, Russia). The concentration of carbon dioxide (30% at the 1

st stage, 70% at the 2

nd stage) and the gas supply rate met the requirements of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2020. The lung tissues were homogenized and used to determine the infectious titers of the viruses and viral RNA loads. The SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 titers, expressed as the TCID

50, were determined by the cytopathic effect (CPE) assay in Vero E6 and HEK293A cells, respectively. The lung homogenates were analyzed for viral genome load by digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR). The SARS-CoV-2, LEV-8 and EV-A71 viral genome loads were determined using primers targeting the 1ab, 2C and 5′UTR sequence, respectively. On Day 7 post-infection, the lung tissues from three animals were fixed in formalin and used for the pathohistological study [

16]. The slides were stained using the standard hematoxylin–eosin staining procedure. Optical microscopy and microphotography were carried out using an Imager Z1 microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) equipped with a high-resolution HRc camera. The images were analyzed using the AxioVision Rel.4.8.2 software package (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany).

2.5. RNA Extraction and qPCR

The viral RNA loads for SARS-CoV-2, LEV-8 and EV-A71 were determined via quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT–PCR). Viral RNAs were extracted and purified with an AmpliPrime RIBO-prep Kit (Interlabservice, Russia) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified RNAs were used to reverse transcription by Reverta-L Kit (Interlabservice, Russia). For quantifying SARS-CoV-2, the Vector-PCRrv-2019-nCoV-RG reagent kits (SRC VB “Vector”, Russia) were used with primers targeting the SARS-CoV-2 1ab gene. Thermal cycling was performed in a RotorGene 6000 cycler (Bio-Rad, USA). Standard curves were generated via tenfold serial dilution of the Internal Positive Control Samples (IPCS) supplied with the respective PCR Kit (the SARS-CoV-2 reverse genetics plasmids encoding the 1ab gene) from 106 to 0.1 copies/reaction. The sample Ct values were obtained on two fluorescent channels, for viral cDNA and for IPCS. The viral cDNA Ct values were scaled relative to the IPCS Ct values.

Digital PCR (dPCR) was also used to determine the SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 viral genome loads using the primers targeting the

1ab and

VP1 genes, respectively [

17]. The reaction mixture contained ddPCRSupermix (x2) (Bio-Rad), primers (900 nM), a probe (250 nM), and cDNA. Each reaction mixture was converted into an oil-in-water emulsion using a QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad, USA). The resulting emulsion was transferred to a 96-well plate and incubated at 95 °C for 10 min to form microdroplets and then amplified in a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) for 40 cycles with the following parameters: 95 °C for 10 min, 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 45 s, and then 98 °C for 10 min. The plate was transferred to a QX200 drop reader (Bio-Rad, USA), and the readout data were analyzed using QuantaSoft software (V1.7.4, Bio-Rad, USA).

The coefficient of variation for qPCR was calculated using the following formula: CVp, % = Сt (standard deviation)/Ct (mean value) × 100% (for five standard samples). The linear range of the dPCR was determined by estimating the average cDNA copy number in a microdroplet [

17]. The Poisson’s test was used to assess the relative error.

In order to determine the chemokine and cytokine response, total RNA in the blood samples was extracted using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a TranscriptorFirst Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Switzerland). qRT-PCR using gene-specific primers [

11] was performed according to the previously described procedure [

11].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Basic statistical analyses, including calculations of the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of the mean Ct value, were performed using Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical data processing was conducted using the STATISTICA 12 statistical software (StatSoft Inc., USA).

Statistical evaluation of intergroup differences was performed using the Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

2.7. Biosafety

All the experiments involving any infectious viral materials were conducted in a Biosafety Level-3 Laboratory with all the applicable national certificates and permissions.

3. Results

3.1. Co-Infection SARS-CoV-2 and Enteroviruses in Vero E6 Cells

In vitro co-infection was simulated by simultaneous and sequential infections in Vero E6 cells. We found that infection with LEV-8 or EV-A71 did interfere with replication of SARS-CoV-2 during the simultaneous co-infection of Vero E6 cells (

Table 1A). Infected with SARS-CoV-2, LEV-8 or EV-A71 alone, cells displayed significantly higher levels of infectious viruses than those co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or with SARS-CoV-2 and EV-A71. It should be noted that with co-infection, the inhibitory effect is more pronounced against SARS-CoV-2.

With sequential infections of Vero E6 cells with LEV-8 or EV-A71 and after 1 day with SARS-CoV-2 (

Table 1B), titers of SARS-CoV-2 during co-infection 24 and 48 h after infection with SARS-CoV-2 were 3–4 lg lower than those in the case of control mono-infection with SARS-CoV-2. When conducting a reverse experiment (successive infection of VeroE6 cells with SARS-CoV-2 and after 1 day, with LEV-8 or EV-A71), pre-infection of SARS-CoV-2 cells was shown to statistically significantly reduce accumulation of infectious enteroviruses (

Table 1B). However, in contrast to the results for SARS-CoV-2 reported above, the difference in infectious titers of LEV-8 or EV-A71 in mono- and co-infected cells did not exceed 2 lg. The results of the dPCR for the viral genome loads correlated with the infectious activity determined directly.

Table 1.

Modeling the in vitro co-infection with LEV-8 or EV-71 and SARS-CoV-2 during simultaneous (A) and consecutive (B) infections in Vero E6 cells.

Table 1.

Modeling the in vitro co-infection with LEV-8 or EV-71 and SARS-CoV-2 during simultaneous (A) and consecutive (B) infections in Vero E6 cells.

| (A) |

| |

Mono-infection |

Co-infection |

| |

SARS-CoV-2 |

LEV-8 |

SARS-CoV-2 + LEV-8 |

Time

post-infection |

Viral titers, lgТCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load according to dPCR, lg genome copies/mL |

Viral

titers, lgTCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load according to dPCR, lg genome copies/mL |

Viral

titers,

SARS-CoV-2/LEV-8, lgTCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load according to dPCR,

SARS-CoV-2/LEV-8,

lg genome copies/mL |

| 24 h |

4.8±0.3 |

6.6±0.4 |

5.2±0.3 |

7.0±0.3 |

2.3±0.3/3.5±0.3 |

4.6±0.3/5.6±0.3 |

| 48 h |

6.9±0.4 |

8.4±0.3 |

7.3±0.4 |

8.6±0.4 |

3.8±0.4/5.8±0.3 |

5.5±0.3/7.3±0.3 |

| |

SARS-CoV-2 |

EV-A71 |

SARS-CoV-2 + EV-A71 |

| 24 h |

5.2±0.3 |

7.0±0.4 |

5.6±0.3 |

7.4±0.3 |

2.2±0.3/3.3±0.3 |

4.3±0.3/5.4±0.3 |

| 48 h |

7.3±0.4 |

8.5±0.3 |

7.5±0.4 |

9.0±0.4 |

3.5±0.4/5.4±0.3 |

5.3±0.3/7.1±0.3 |

| (B) |

Time

post-infection with SARS-CoV-2 |

Viral titers (SARS-СoV-2/LEV-8), lgТCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load according to dPCR (SARS-СoV-2/LEV-8) lg genome copies/mL |

Viral titers,

lgТCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load by dPCR, lg genome copies/mL |

| |

LEV-8 pre-infection -24h- SARS-CoV-2 |

Mock pre-infection -24h- SARS-CoV-2 |

| 24 h |

2.7±0.3/6.9±0.4 |

4.4±0.3/8.2±0.4 |

5.1±0.4 |

7.7±0.3 |

| 48 h |

3.2±0.3/7.3±0.4 |

4.8±0.4/9.1±0.3 |

7.2±0.4 |

9.3±0.4 |

| |

SARS-CoV-2 pre-infection -24h- LEV-8 |

Mock pre-infection -24h- LEV-8 |

| 48 h |

6.3±0.3/5.9±0.4 |

8.0±0.4/7.8±0.3 |

5.3±0.3 |

7.1±0.3 |

| 72 h |

5.0±0.4/5.6±0.4 |

6.9±0.3/7.4±0.4 |

7.5±0.4 |

9.2±0.3 |

Time

post-infection with SARS-CoV-2 |

Viral titers (SARS-СoV-2/EV-A71), lgТCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load according to dPCR (SARS-СoV-2/EV-A71) lg genome copies/mL |

Viral titers,

lgТCID50/mL |

Viral RNA load by dPCR, lg genome copies/mL |

| |

EV-A71 pre-infection -24h- SARS-CoV-2 |

Mock pre-infection -24h- SARS-CoV-2 |

| 24 h |

2.9±0.3/4.9±0.2 |

4.7±0.3/6.5±0.2 |

5.2±0.3 |

7.3±0.3 |

| 48 h |

3.1±0.3/6.5±0.4 |

5.0±0.4/8.2±0.3 |

7.1±0.4 |

8.7±0.4 |

| |

SARS-CoV-2 pre-infection -24h- EV-A71 |

Mock pre-infection -24h- EV-A71 |

| 48 h |

5.8±0.4/5.3±0.4 |

7.6±0.3/7.1±0.3 |

6.8±0.3 |

8.3±0.4 |

| 72 h |

4.7±0.3/5.1±0.3 |

7.0±0.3/7.2±0.4 |

6.5±0.4 |

8.0±0.3 |

3.2. Co-Infection with SARS-CoV-2 and Enteroviruses in Animals

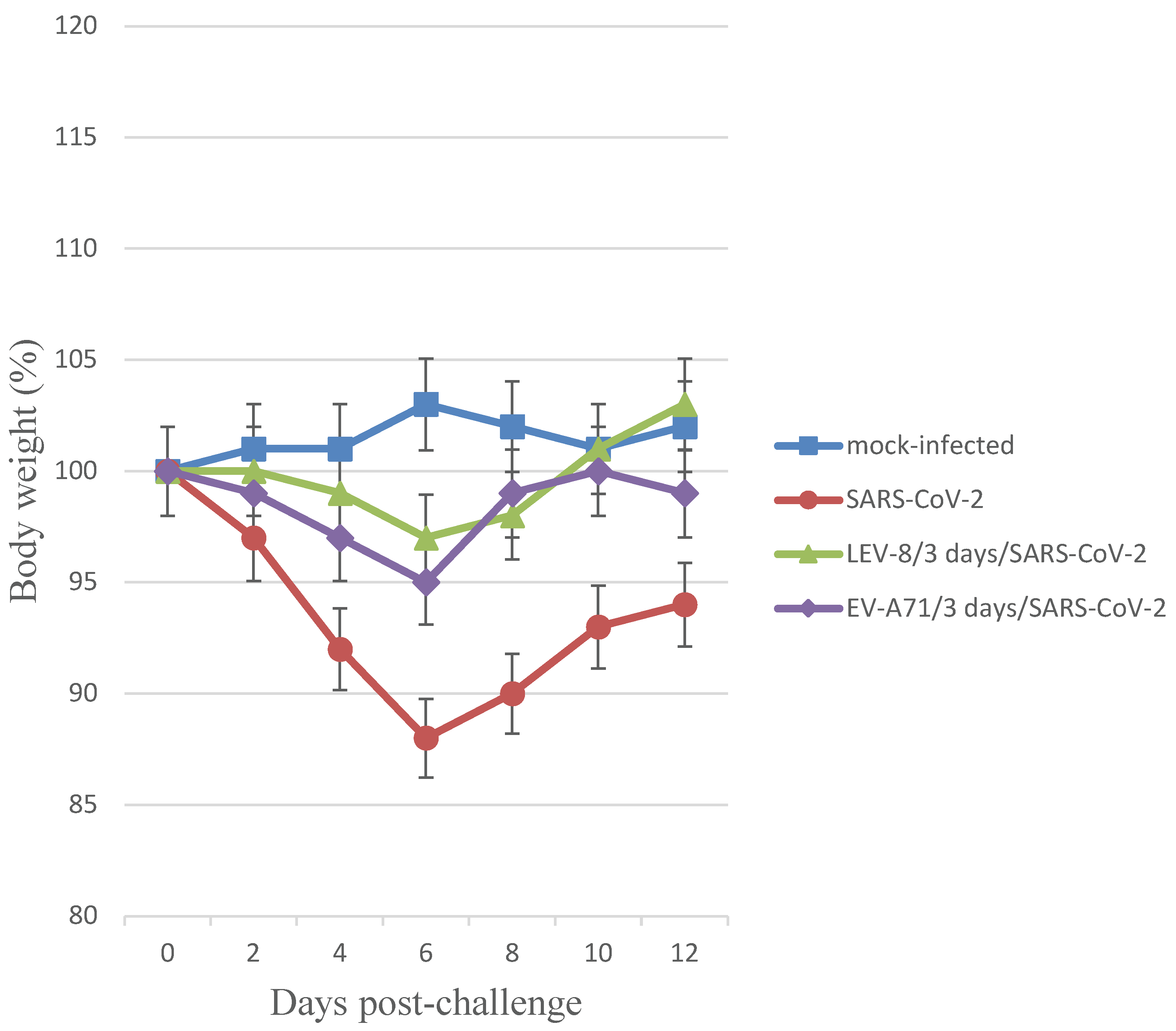

Co-infection of Syrian hamsters with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 and mono-infection with SARS-CoV-2 resulted in clinical signs such as lethargy, ruffled fur, hunchback posture, and rapid breathing. Subjectively, these manifestations were more pronounced in hamsters mono-infected with SARS-CoV-2. The clinical scores [

18] for LEV-8/3 days/SARS-CoV-2, EV-A71/3 days/SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 groups were 1.30±0.45, 1.47±0.57 and 2.95±0.80, respectively. Mono-infection of Syrian hamsters with LEV-8 or EV-A71 did not result in clinical signs. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 alone resulted in 12% weight reduction (

Figure 1). Reduction in average animal weight was significantly smaller in the LEV-8/3 days/SARS-CoV-2 and EV-A71/3 days/SARS-CoV-2 groups (3% and 5%, respectively). Animals intranasally mono-infected with LEV-8 or EV-A71 did not lose weight during the follow-up period (data not shown). These data demonstrate that co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 reduced the severity of clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

SARS-CoV-2 — on Day 0, the animals were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); LEV-8/3-days/SARS-CoV-2 — on Day 0, hamsters pre-infected (3 days earlier) with LEV-8 (106 ТCID50) were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); EV-A71/3-days/SARS-CoV-2 — on Day 0, hamsters pre-infected (3 days earlier) with EV-A71 (106 ТCID50) were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); mock-infected — on Day 0, hamsters were intranasally inoculated with PBS. n = 9 at 0 dpi to 4 dpi; n = 6 at 5 dpi to 6 dpi as 3 animals were sacrificed; n = 3 at 7 dpi to 12 dpi as 3 animals were sacrificed.

The values represent the means ± SDs of individual animals. Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons. *p < 0.05.

3.3. Replication of SARS-CoV-2 and Enteroviruses in the Lungs

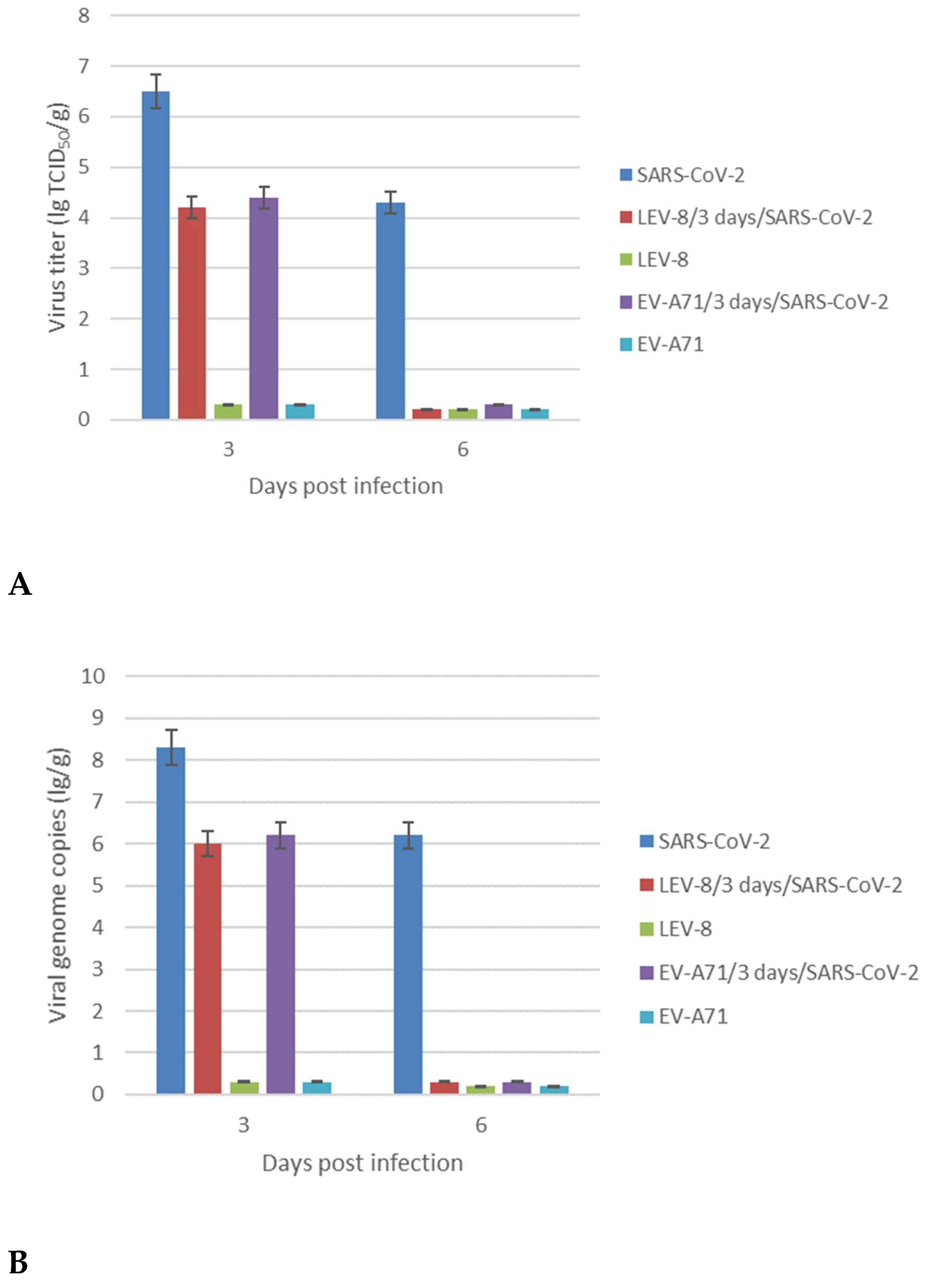

In order to elucidate whether co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 enhances or inhibits viral replication, lung tissues were homogenized to determine the infectious titers and viral RNA genome loads (

Figure 2). Animals infected with SARS-CoV-2 alone displayed significantly higher levels of infectious SARS-CoV-2 at 3 dpi in the lungs than hamsters co-infected with LEV-8 or EV-A71. Moreover, at 6 dpi, the infectious SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs of hamsters co-infected with enteroviruses was not detected, while high SARS-CoV-2 concentrations were identified in the lungs of hamster mono-infected with SARS-CoV-2 for this period. Importantly, LEV-8 and EV-A71 replication in mono-infected and co-infected hamster lungs did not detected. The viral genome loads for both SARS-CoV-2 and enteroviruses generally corresponded with the infectious viral titers (

Figure 2B). In general, similar results were obtained for the animals simultaneously infected with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 (

Figure S1).

(A) SARS-CoV-2, LEV-8 and EV-A71 viral infectious titers; (B) SARS-CoV-2, LEV-8 and EV-A71 viral genome loads.

SARS-CoV-2—on Day 0, the Syrian hamsters were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); LEV-8/3-days/SARS-CoV-2—on Day 0, the hamsters pre-infected (3 days earlier) with LEV-8 (106 ТCID50) were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); EV-A71/3-days/SARS-CoV-2 — on Day 0, the hamsters pre-infected (3 days earlier) with EV-A71 (106 ТCID50) were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); LEV-8 — on Day 0, the Syrian hamsters were intranasally challenged with LEV-8 (106 ТCID50); EV-A71 —on Day 0, the Syrian hamsters were intranasally challenged with EV-A71 (106 ТCID50). The lung homogenates on Days 3 and 6 were analyzed by the CPE assay in Vero E6 (SARS-CoV-2) and HEK293A (LEV-8 and EV-A71) cells, respectively, and for viral genome loads by dPCR. The SARS-CoV-2 and enterovirus genome loads were determined using primers targeting the 1ab and VP1 genes, respectively. The values represent the means ± SDs of three animals. Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons. *p < 0.05.

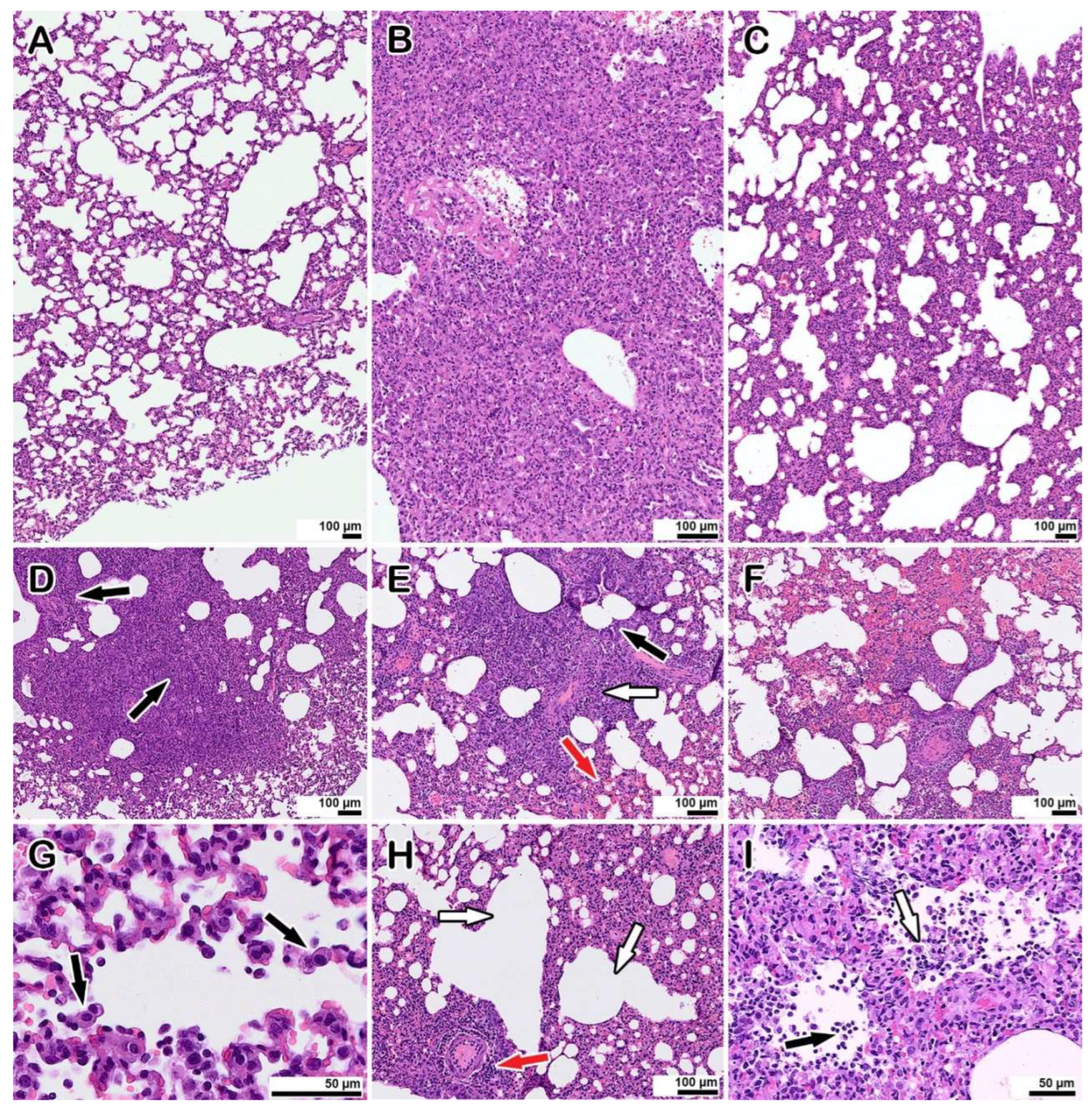

3.4. Morphological Examination of Co-Infected Animals

The morphological examination of the lungs of hamsters co-infected with LEV-8 as live enteroviral vaccine against human respiratory diseases and SARS-CoV-2 (Days 6 and 9 after LEV-8 and SARS-CoV-2 infection, respectively) revealed moderate pathological manifestations characteristic of viral pneumonia (

Figure 3 C, H, I); i.e., there were single small areas of edema of the interalveolar septa (no more than a few percent of the section area); there was a moderate decrease in airiness according to the distelectasis type (approximately 15–20% of the section area) in combination with increased blood flow in the interalveolar septa capillaries and moderate infiltration of inflammatory cells of a mixed composition (20–25% of the section area); the rest of the parenchyma exhibited essentially normal histological characteristics. In animals infected with SARS-CoV-2 alone (6 days after infection), the pathomorphological manifestations were significantly more pronounced, with signs of an acute phase of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) (

Figure 3 B, D-G); i.e., there was dense edema in 50–70% of the section area with pronounced polymorphic (mainly lymphocytic) inflammatory cell infiltration, and there were distinct manifestations of vasculitis and bronchiolitis, with the rest of the parenchymal space being in a state of emphysema. Pronounced signs of vasculitis and bronchiolitis, large foci of plasma, and hemorrhages (approximately 22–25% of the section area) were also detected. No pathological changes in the lungs of hamster mono-infected with LEV-8 were detected. Lung scoring parameters are presented in

Table S1. The findings indicate that co-infection with LEV-8 reduces severe pathological changes induced by SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs.

(A) mock-infected control animal, normal lung.

(B, C) representative images showing pathological changes in the lung tissue after infection: B—with SARS-CoV-2; C—with LEV-8 and SARS-CoV-2.

(D – G) typical pathological changes found in SARS-CoV-2 infected animals. D—an abrupt decline in the airiness of the pulmonary tissue, dense inflammatory cell infiltrates (arrows). E—the inflammatory reaction with manifestations of vasculitis (white arrow), bronchiolitis (black arrow) and hemorrhages (red arrow). F—large area of hemorrhage. G—desquamation of alveolocytes (arrows), leukocyte migration into the alveolar lumen.

(H, I) pathological changes in animals co-infected with LEV-8 and SARS-CoV-2. H—mild decrease in airiness accompanied by moderate manifestations of vasculitis (red arrow) and compensatory emphysema (white arrows). I—leukocytes (black arrow) in the alveoli; desquamation of alveolar epithelial cells (white arrow).

Staining with hematoxylin and eosin. All images were taken using a 40× lens. The scale bar is shown in the images.

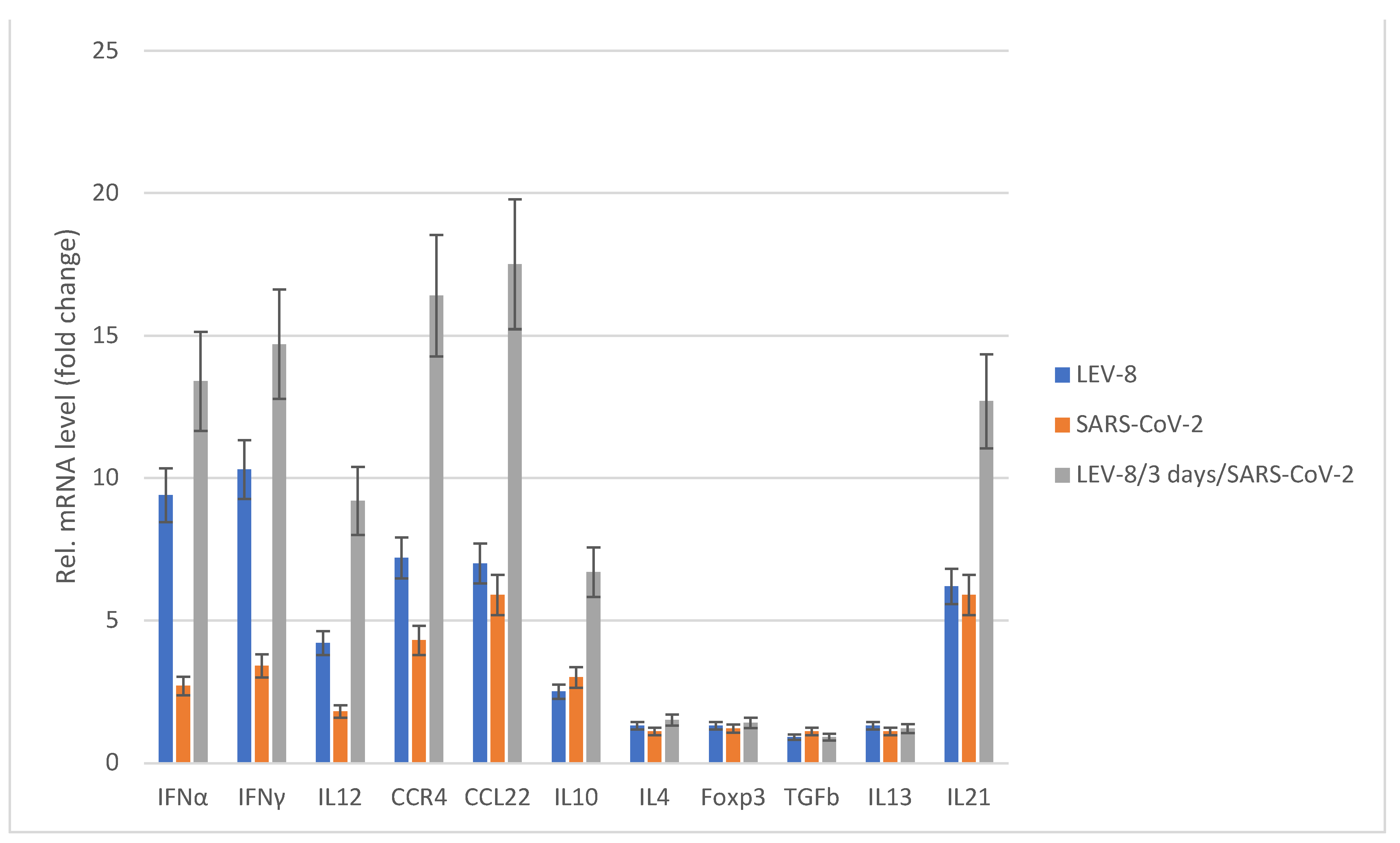

3.5. Chemokine/Cytokine Responses in Co-Infected Animals

Figure 4 shows the cytokine/chemokine profiles in the blood samples of hamsters mono- and co-infected with LEV-8 and SARS-CoV-2. LEV-8 and SARS-CoV-2 mono-infection resulted in increased mRNA levels of the genes involved in the interferon and cytokine pathways; this induction effect is more pronounced against LEV-8. An approximately tenfold increase in IFNα and IFNγ levels was detected after LEV-8 infection. The interferon type I and II mRNA levels were increased on Day 5 post-infection, implying that LEV-8 effectively triggered the innate immune response. When hamsters were infected with both LEV-8 and SARS-CoV-2, the mRNA levels of certain genes within these pathways were abundantly increased compared to the case of mono-infection with LEV-8 or SARS-CoV-2. These data demonstrating that pre-infection with LEV-8 significantly increased interferon and cytokine responses (IL12, CCR4, CCL22 and IL21) agree well with the findings that co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 reduced the replicating activity of SARS-CoV-2 in the lungs and the severity of clinical and pathomorphological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

SARS-CoV-2 — the hamsters were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50); LEV-8 — the Syrian hamsters were intranasally challenged with LEV-8 (106 ТCID50); LEV-8/3 days/SARS-CoV-2 – the hamsters pre-infected (3 days earlier) with LEV-8 (106 ТCID50) were intranasally challenged with SARS-CoV-2 (105 ТCID50). On Days 5 post-infection (for the LEV-8/3 days/SARS-CoV-2 group, this took place on Day 5 after the challenge with SARS-CoV-2), blood samples collected from hamsters were used to determine the chemokine/cytokine mRNA profile. The data are expressed as fold changes relative to the mock-infected group. All the mRNA levels were normalized to the β-actin level in the same hamster. The values represent the means ± SDs of three individual animals. Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons. *p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

SARS CoV-2 causes a broad range of clinical manifestations, from inapparent form or weak symptoms to grave or critical illness [

19]. In accordance with a number of studies, co-infection of SARS CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses can aggravate the state of illness and cause unfavorable outcomes compared to a single infection: longer duration, an increased rate of complications, a higher rate of intensive care unit (ICU) usage and mortality [

7,

20]. Nevertheless, other investigators found that the clinical short- and long-term outcomes for patients are more favorable in co-infected individuals [

8]. Therefore, research into co-infection with SARS CoV-2 and other viruses by simulating mixed infection both

in vitro and

in vivo is of great importance. Aside from viral interference, i.e., when one virus inhibits the replication of another co-infecting virus, co-infections with certain viruses may also induce an increase in viral replication, although co-infections sometimes have no effect on virus replication [

21].

In a previous study, enhanced SARS-CoV-2 replication was detected after preliminary infection of cell cultures and K18-hACE2 mice with influenza A virus (IAV) [

22]. A significant increase in the SARS-CoV-2 viral genome load was observed in the lungs of co-infected mice. The lung histological data also illustrate that IAV and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection induced more severe pathological changes in the lungs, with massive cell infiltration and obvious alveolar necrosis, compared to SARS-CoV-2 mono-infection [

22]. Earlier, our

in vivo study demonstrated that pre-infection with human adenovirus type 5 (HAdV-5) or IAV did not significantly decrease the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. However, hamsters co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and IAV or HAdV-5 displayed more pronounced lung damage and clinical manifestations than animals mono-infected with SARS-CoV-2, IAV or HAdV-5 did [

23].

The SARS-CoV-2 models and rhinovirus single or co-infections in nasal epithelia found that replication of the former virus was inhibited by primary but not secondary rhinovirus infection, which was modulated by interferon (IFN) induction [

24]. It was also shown that during concomitant infection of nasal epithelium, SARS-CoV-2 interferes with the kinetics of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) replication; however, SARS-CoV-2 replication is not influenced by RSV [

25]. These findings indicate the importance of considering the sequence of SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory virus co-infections. Furthermore, immunofluorescent staining of K18 mice lungs mono-infected with SARS-COV-2 had significantly more positive SARS-CoV-2 cells versus those co-infected with RSV group.

In this study, the features of the co-infectious with SARS-CoV-2 by simulating co-infection

in vitro and

in vivo using nonpathogenic strain LEV-8 of coxsackievirus A7 [

9] and non-rhinovirus respiratory enterovirus EV-A71, which associated with HFMD and viral encephalitis [

26] were investigated. When modeling the co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 with LEV-8 or EV-A71

in vitro, it was shown that SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71, with simultaneous and sequential infection, exert a competitive inhibitory. At the same time, it should be noted a more pronounced degree of competitive inhibition against SARS-CoV-2, rather than vice versa. This is probably due to viral interference when one virus inhibits the replication of another virus through resource competition, by induction of interferon, or via other mechanisms. Through experimental co-infections with LEV-8 or EV-A71 and SARS-CoV-2, we found that pre-infection with enteroviruses in hamsters caused a 100-fold reduction in the levels of SARS-CoV-2 virus titers in the respiratory tracts compared to those in animal mono-infected with SARS-CoV-2. Simulation of co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and enteroviruses showed that preliminary intranasal infection with enteroviruses led to a more rapid clearance of the hamster lower respiratory tract from the infectious SARS-CoV-2 virus. Along with this, it was shown that co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 reduced the severity of clinical manifestations of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. The absence of infectious enteroviruses in the lungs and clinical manifestations of EV-A71 infection in hamsters was due to the fact that we used adult animals as usually using models for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Morphological examination of co-infected animals indicates that co-infection with nonpathogenic coxsackievirus A7 LEV-8 strain reduces severe pathological changes in the lungs induced by SARS-CoV-2. A study of chemokine/cytokine responses demonstrated that LEV-8 efficiently triggered the innate immune response, which manifested itself as increased IFNα, IFNγ, IL12, CCR4, CCL22 and IL21 levels in animals. In co-infected hamsters, the genes within these pathways were abundantly increased compared to animal mono-infected with LEV-8 or SARS-CoV-2. These results demonstrate that there exists strong viral interference between the studied enteroviruses and SARS-CoV-2

in vitro and

in vivo.

LEV-8 belongs to the group of live enterovirus vaccines stimulating production of endogenous interferon of the host [

9]. Controlled trials of their epidemiological efficacy were carried out during three seasonal outbreaks of influenza and other associated acute respiratory infections (ARIs) in 16 regions of three republics in the former Soviet Union [

9,

27]. The surveillance covered approximately 320,000 people, two-thirds of whom have orally received live enteroviral interferon-inducing vaccine strains (LEV). No adverse reactions were observed following the administration of LEV. The enterovirus vaccines ensured protection against influenza and ARIs by reducing the incidence on average 3.2-fold compared to controls who did not receive LEV. Additionally, the post-infection administration of standard LEV at the beginning of outbreaks of influenza and ARIs had a therapeutic effect ameliorating the disease. It was also shown that live attenuated vaccines in general, and oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) in particular, can ensure protection against COVID-19 [

28]. The authors stated that this strategy may even have an advantage over specific vaccines if SARS-CoV-2 undergoes mutations that could lead to loss of vaccine efficacy. Moreover, COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization exhibited a significantly lower level of antibodies targeting rhinoviruses and enteroviruses compared to those who did not [

29,

30]. It was also observed in the same studies that COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization exhibited a higher seroprevalence rate for cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1).

5. Conclusion

The co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and nonpathogenic strain LEV8 of coxsackievirus A7 or enterovirus 71 pathogenic for humans was investigated using the in vitro and in vivo models. It was shown that co-infection SARS-CoV-2 and LEV-8 or EV-A71 have a significant competitive inhibitory effect on each other with a more pronounced degree for inhibition SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pre-infection with enteroviruses in Syrian hamsters inhibited the levels of SARS-CoV-2 infectious titers in the respiratory tracts and led to a more rapid clearance of the lower respiratory tract from the infectious SARS-CoV-2. Co-infection SARS-CoV-2 with LEV-8 or EV-A71 reduced the severity of clinical manifestations of the SARS-CoV-2 infection in the animal model. Additionally, the lung histological data illustrate that co-infection with nonpathogenic coxsackievirus A7 LEV-8 strain mitigated severe SARS-CoV-2 pathological changes in the lungs. A study of the chemokine/cytokine profile demonstrated that this enterovirus efficiently triggered the innate immune response, which can be associated with inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication during co-infection in the animal model. Therefore, the findings demonstrate that there exists significant viral interference between the studied enteroviruses and SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and in vivo.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author statements

V.A.S., V.A.T., E.V.P., V.B.L., and O.S.T. designed the experiments and analyzed the data; V.A.S., V.A.T., S.S.L., R.Y.L., E.P.V., E.V.P., O.S.T., and V.V.O. performed the experiments; A.P.A. managed the investigation and obtained funds; V.A.S. and V.B.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, in compliance with the protocols and recommendations for the proper use and care of laboratory animals (ECC Directive 86/609/EEC, Ministry of Health of Russian Federation Directive no. 708n/2010, and Ministry of Health of Russian Federation Directive no. 267/2003). The protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Federal Budgetary Research Institution State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” (protocol code: SRC VB ”Vector”/02-05; date of approval: May 15, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. P.M. Chumakov (Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences) for providing the LEV-8 CVA7 strain and excellent collaboration. This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (075-15-2019-1665).

Conflicts of Interest

No authors report any conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.; Tian, J.; Pei, Y.; Yuan, M.L.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Xu, L.; Holmes, E.; Zhang, Y.Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; Niu, P.; Zhan, F.; Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Xu, W.; Wu, G.; Gao, G.; Tan, W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Quinn, J.; Pinsky, B.; Shah, N.H.; Brown, I. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. J.A.M.A. 2020, 323, 2085–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansbury, L.; Lim, B.; Baskaran, V.; Lim, W. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, E.; Hoang, V.; Boschi, C.; Ninove, L.; Zandotti, C.; Boutin, A.; Bremond, V.; Dubourg, G.; Ranque, S.; Lagier, J.; Million, M.; Fournier, P.; Drancourt, M.; Gautret, P.; Colson, F. Incidence and outcome of coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 and rhinovirus. Viruses 2021, 13, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltezou, H.; Paranikolopoulou, A.; Vassiliu, S.; Theodoridou, K.; Nikolopolou, G.; Sipsas, N. COVID-19 and respiratory virus co-Infections: a systematic review of the literature. Viruses 2023, 15, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, E.; Hasegawa, K.; Lawrence, A.; Kline, J.; Camargo, C. Viral coinfection is associated with improved outcomes in emergency department patients with SARS-CoV-2. West J Emerg Med. 2021, 22, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Zhang, A.; Yuan, S.; Poon, V.; Chan, C.; Lee, A.; Chan, W.; Fan, Z.; Tsoi, H.; Wen, L.; Liang, R.; Cao, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, K.; Luo, C.; Cai, J.; Kok, K.; Chu, H.; Chan, K.; Sridhar, S.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; To, K.; Yuen, K. Simulation of the clinical and pathological manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a golden Syrian hamster model: implications for disease pathogenesis and transmissibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2428–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, M.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Hatta, M.; Loeber, S.; Halfmann, P.J.; Nakajima, N.; Watanabe, T.; Ujie, M.; Takahashi, M. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 16587–16595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyu, W.; Ong, K.; Won, K. A consistent orally-infected hamster model for enterovirus A71 encephalomyelitis demonstrates squamous lesions in the paws, skin and oral cavity reminiscent of Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease. PLoS One 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chumakov, M.P.; Voroshilova, M.K.; Antsupova, A.S.; Boiko, V.M.; Blinova, M.I.; Priimiagi, L.S.; Rodin, V.I.; Seibil, V.B.; Siniak, K.M.; Smorodintsev, A.A. Live enteroviral vaccines for the emergency nonspecific prevention of mass respiratory diseases during fall-winter epidemics of influenza and acute respiratory diseases. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol 1992, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T. Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease, Aseptic Meningitis, and Encephalitis Caused by Enterovirus. Brain and nerve 2018, 70, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svyatchenko, V.; Nikonov, S.; Mayorov, A.; Gelfond, M.; Loktev, V. Antiviral photodynamic therapy: Inactivation and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro using methylene blue and Radachlorin. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 33, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, K.; Spencer, J.; Dhar, D.; Sagartz, J.; Buller, R.; Painter, G.; Wold, W.S. Hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir, CMX001, prevents adenovirus induced mortality in a permissive, immunosuppressed animal model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7293–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryzhikov, A.B.; Ryzhikov, E.A.; Bogryantseva, M.P.; Danilenko, E.D.; Imatdinov, I.R.; Nechaeva, E.A.; Pyankov, O.; Pyankova, O.G.; Susloparov, I.; Taranov, O.; Gudymo, A.; Danilchenko, N.; Sleptsova, E.; Bodnev, S.; Onkhonova, G.; Petrov, V.; Moiseeva, A.; Torzhkova, P.; Pyankov, S.; Tregubchak, T.; Antonets, D.; Gavrilova, E.; Maksyutov, R. Immunogenicity and protectivity of the peptide vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Annals of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences 2021, 76, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.; Mason, D.J.; Foy, C.A.; Huggett, J.F. Evaluation of digital PCR for absolute RNA quantification. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, A.; Poon, V.K.; Chan, C.C.; Lee, A.C.; Fan, Z.; Li, C.; Liang, R.; Cao, J. Surgical mask partition reduces the risk of noncontact transmission in a Golden Syrian hamster model for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2139–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.A.; Safamanesh, S.; Ghasemzadeh-Moghaddam, H.; Ghafouri, M.; Azimian, A. High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus (H1N1) coinfection in dead patients in Northeastern Iran. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 93, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, J.; Tessier, E.; Zhao, H.; Guy, R.; Muller-Pebody, B.; Zambon, M.; Andrews, N.; Ramsay, M.; Lopez Bernal, J. Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza and the impact of coinfection on disease severity: A test negative design. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sharma, S.; Barua, S.; Tripathi, B.; Rouse, B. Virological and Immunological Outcomes of Coinfections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, J.; Liang, S.; Guo, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, L.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Niu, D.; Xiang, M.; Song, K.; Ye, J.; Zheng, W.; Tang, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, C.; Dai, M.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Yan, H.; Lan, K.; Xu, K. Coinfection with influenza A virus enhances SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Cell Res. 2021, 4, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svyatchenko, V.A.; Ternovoi, V.A.; Lutkovskiy, R.Y.; Protopopova, E.V.; Gudymo, A.S.; Danilchenko, N.V.; Susloparov, I.M.; Kolosova, N.P.; Ryzhikov, A.B.; Taranov, O.S.; Omigov, V.V.; Gavrilova, E.V.; Agafonov, A.P.; Maksyutov, R.A.; Loktev, V.B. Human Adenovirus and Influenza A Virus Exacerbate SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Animal Models. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essaidi-Laziosi, M.; Alvarez, C.; Puhach, O.; Sattonnet-Roche, P.; Torriani, G.; Tapparel, C.; Kaiser, L.; Eckerle, I. Sequential infections with rhinovirus and influenza modulate the replicative capacity of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2022, 11, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fage, C.; Henaut, M.; Carbonneau, J.; Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus but not respiratory syncytial virus interferes with SARS-CoV-2 replication during sequential infections in human nasal epithelial cells. Viruses 2022, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royston, L.; Tapparel, C. Rhinoviruses and respiratory enteroviruses: not as simple as ABC. Viruses 2016, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovesdi, I.; Sandig, V.; Slavin, S.; Renz, W.; Ranst, M.; Chumakov, P.; Bakacs, T. The clinically validated viral superinfection therapy (SIT) platform technology could cure early cases of COVID-19 disease. 2020, 2020020147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumakov, K.; Benn, C.S.; Aaby, P.; Kottilil, S.; Gallo, R. Can existing live vaccines prevent COVID-19? Science 2020, 368, 1187–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashir, J.; AlKattan, K.; Yaqinuddin, A. COVID-19: cross-immunity of viral epitopes may influence severity of infection and immune response. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrock, E.; Fujimura, E.; Kula, T.; Timms, R.; Lee, I.; Leng, Y.; Robinson, M.; Sie, B.; Li, M. Viral epitope profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals cross-reactivity and correlates of severity. Science 2020, 370, eabd4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).