Submitted:

11 March 2024

Posted:

13 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

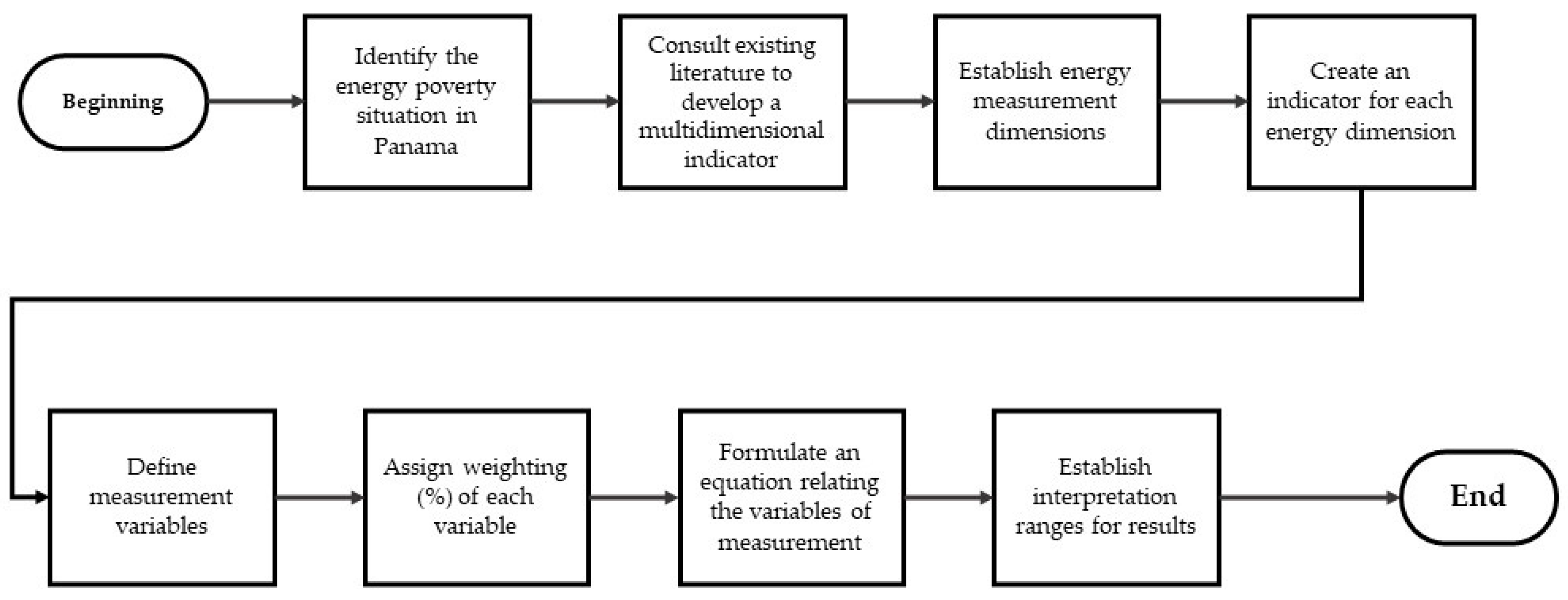

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Energy Needs

2.1.1. Lighting

2.1.2. Cooking

2.1.3. Food Refrigeration

2.1.4. Knowledge, Entertainment and Communication

2.1.5. Thermal Comfort (Forced Ventilation)

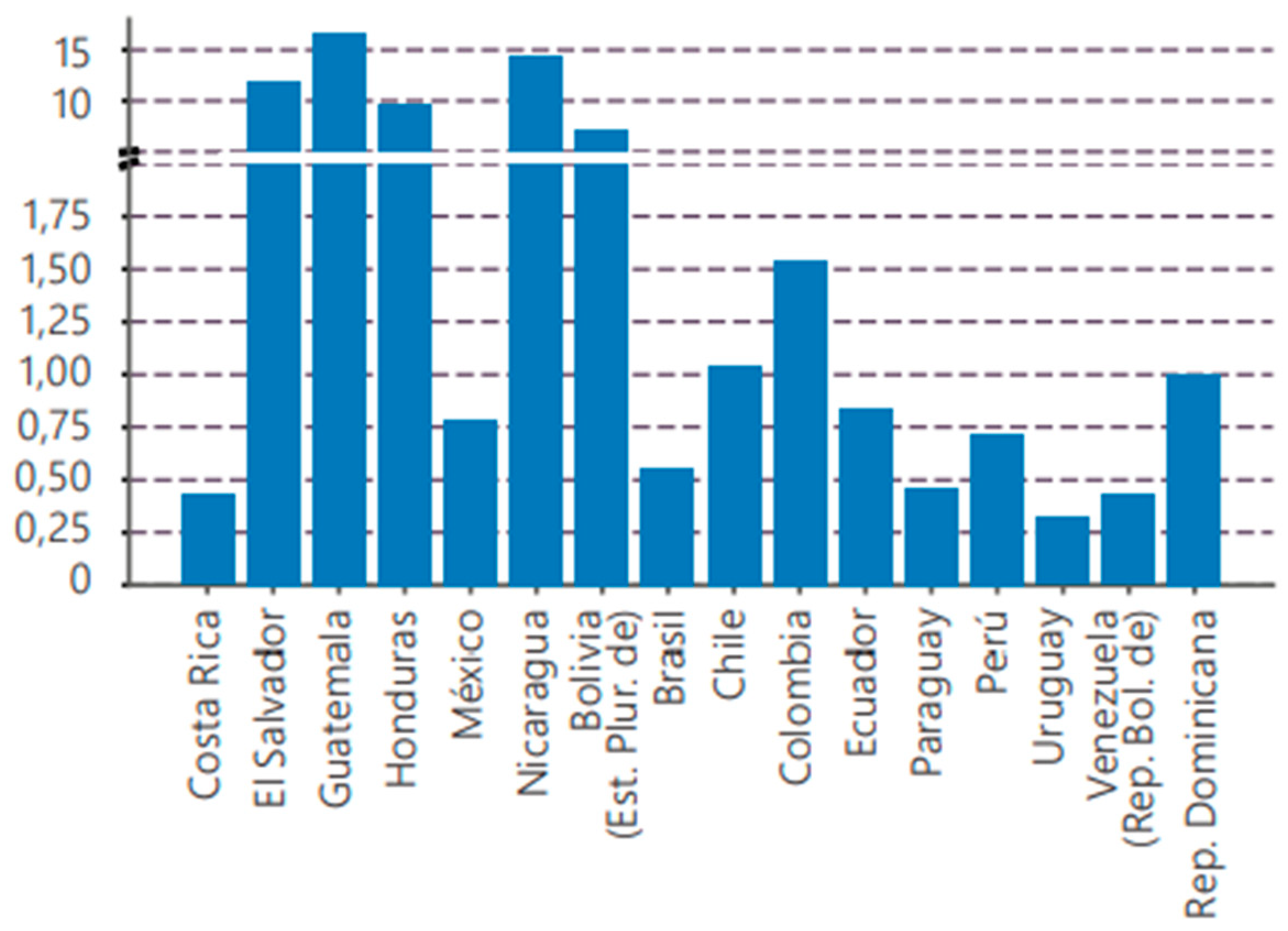

2.2. Causal Factors of EP in Panama and Indicators

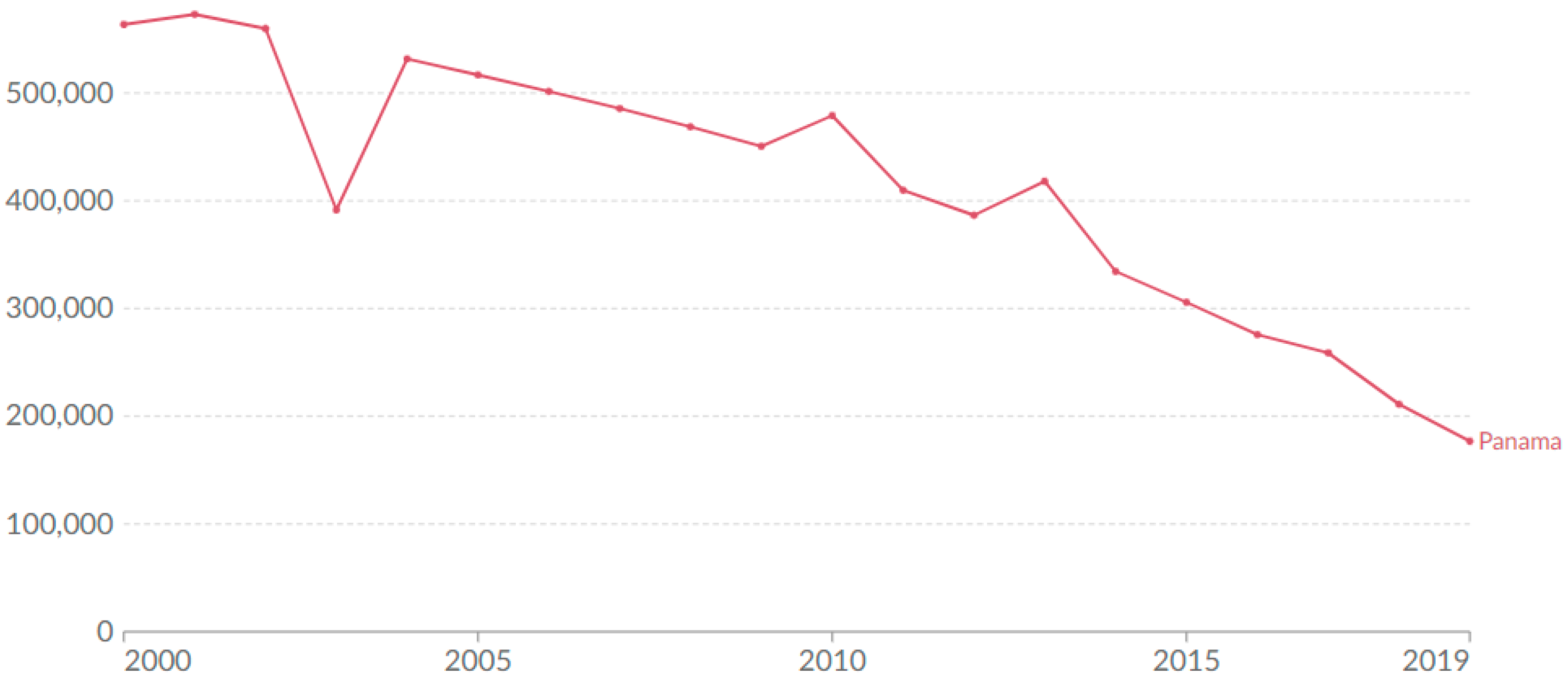

2.2.1. Inaccess to Energy Infrastructure

2.2.2. Low Household Income

2.2.3. High Energy Costs

2.2.4. Housing Quality and Energy Efficiency

2.2.5. Quality of Electric Power Service

2.3. Proposed Parameter for Measuring PE in Panama

2.3.1. One-Dimensional Indicators

2.3.2. Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index for Panama (MEPIP)

- Multidimensional Energy Poverty Indicator, United Kingdom.

- Household Energy Poverty Indicator, Mexico

- Multi Tier Framework Indicator, United Kingdom

- Three-Dimensional Energy Poverty Indicator, Chile

- 0: does not possess the economic good.

- 1: Possesses the economic good, but not the minimum acceptable quantity.

- 2: Possesses the economic good, but it is not in good condition or is polluting.

- 3: Possesses the economic good in reasonable quantities and good conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Definition of EP for Panama

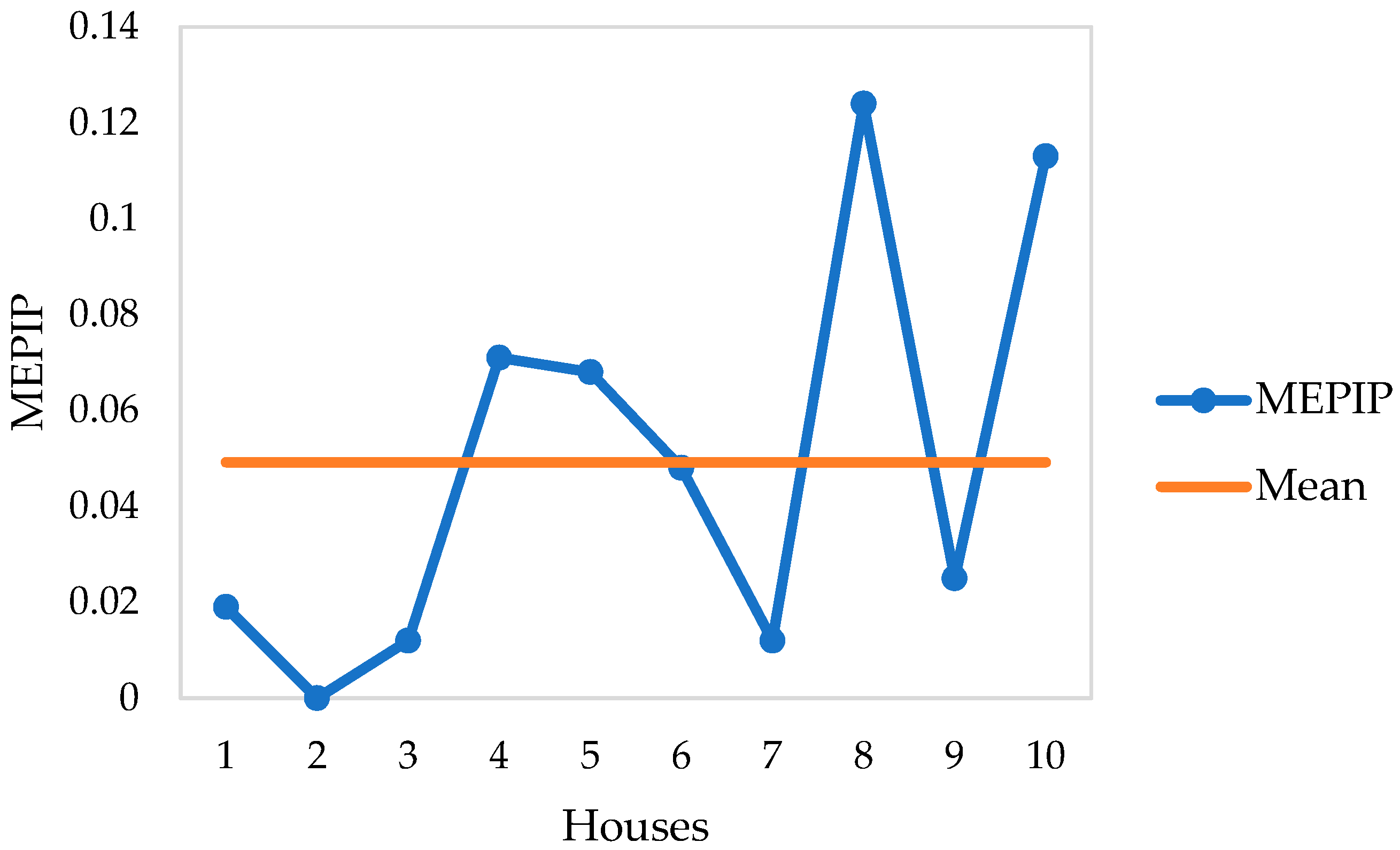

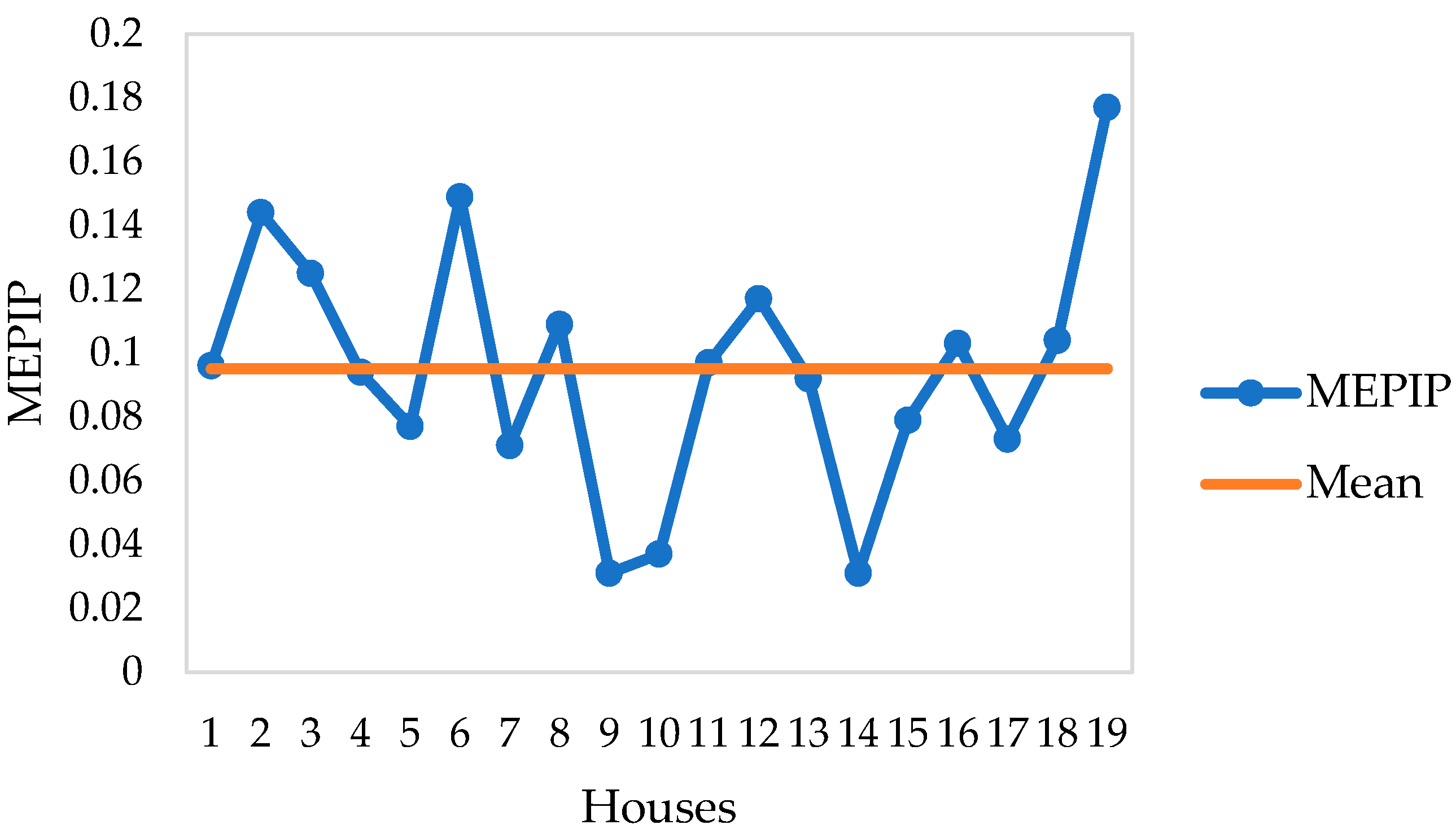

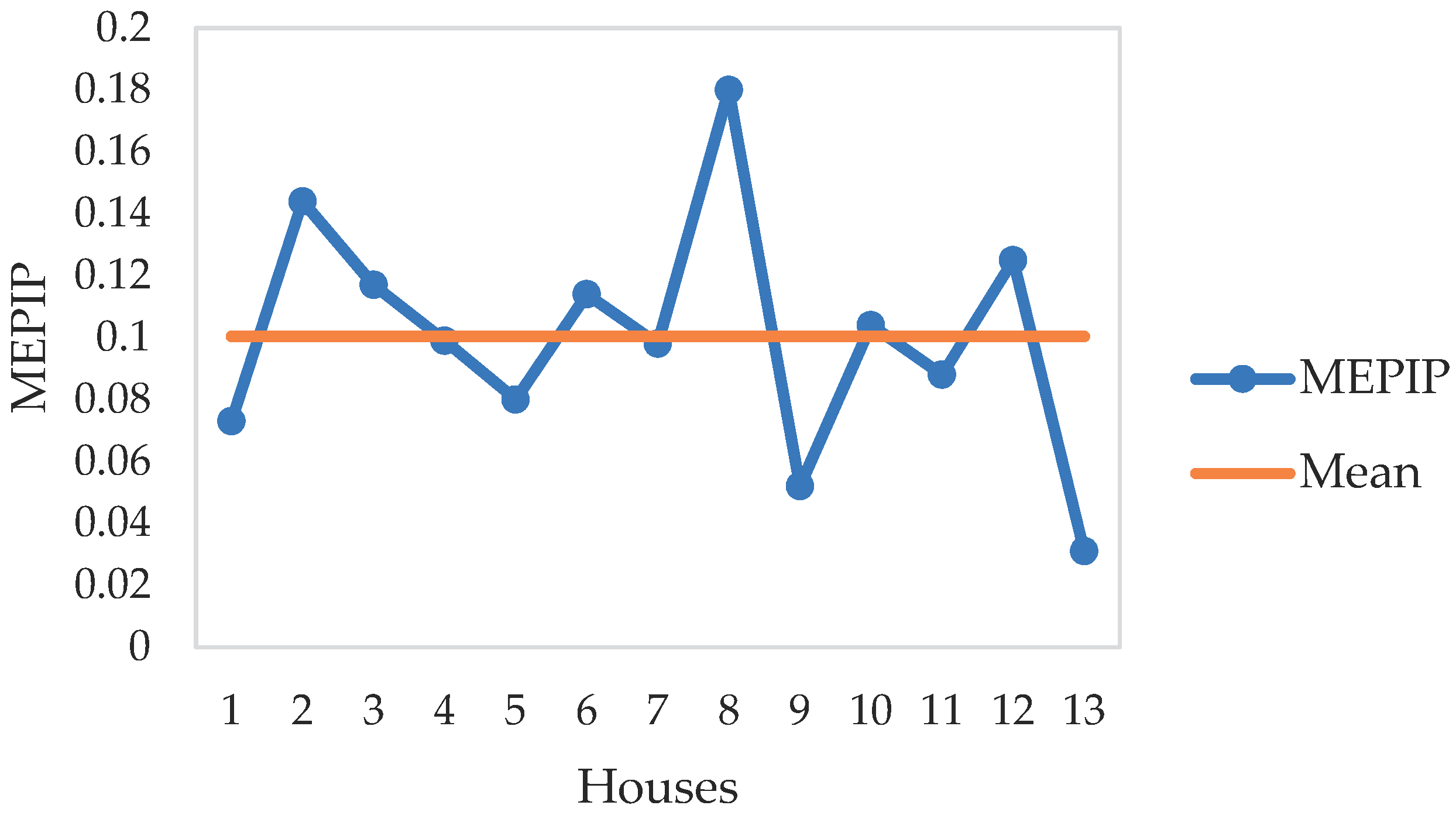

3.2. Application of MEPIP to Rural Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- R. Calvo, N. Álamos, M. Billi, A. Urquiza, and R. Contreras Lisperguer, “Desarrollo de indicadores de pobreza energética en América Latina y el Caribe 207 RECURSOS NATURALES Y DESARROLLO,” Santiago de Chile, 2021. [Online]. Available: www.cepal.org/apps.

- B. K. Sovacool et al., “What moves and works: Broadening the consideration of energy poverty,” Energy Policy, vol. 42, pp. 715–719, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tao and J. Chao, “A bibliometric and visualized analysis of research on green finance and energy in a global perspective,” Research in Globalization, vol. 7, p. 100156, 2023. [CrossRef]

- IEA, “SDG7: Data and Projections.” Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.iea.org/reports/sdg7-data-and-projections.

- D. Alemzero, T. Acheampong, and S. Huaping, “Prospects of wind energy deployment in Africa: Technical and economic analysis,” Renew Energy, vol. 179, pp. 652–666, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohsin, F. Taghizadeh-Hesary, and M. Shahbaz, “Nexus between financial development and energy poverty in Latin America,” Energy Policy, vol. 165, p. 112925, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Castaño Rosa, J. Solís Guzmán, and M. Marrero, “Midiendo la pobreza energética. Una revisión de indicadores,” Revista hábitat sustentable, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 9–21, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Day, G. Walker, and N. Simcock, “Conceptualising energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework,” Energy Policy, vol. 93, pp. 255–264, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Moniruzzaman and R. Day, “Gendered energy poverty and energy justice in rural Bangladesh,” Energy Policy, vol. 144, p. 111554, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Lin and Y. Wang, “Does energy poverty really exist in China? From the perspective of residential electricity consumption,” Energy Policy, vol. 143, p. 111557, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. García-Ochoa, “Pobreza energética en América Latina,” Santiago de Chile, Mar. 2014. Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/79cc961b-7908-4fce-a7dd-133d484c1be7/content.

- N. Marzolf and M. Ramírez, “Avanzando en la erradicación de la Pobreza Energética: Plataforma de indicadores a nivel residencial en Chile - Energía para el Futuro.” Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.iadb.org/energia/es/avanzando-en-la-erradicacion-de-la-pobreza-energetica-plataforma-de-indicadores-a-nivel-residencial-en-chile/.

- L. Contreras and R. Rubén - Salgado, “Informe regional sobre el ODS 7 de sostenibilidad energética en América Latina y el Caribe | CEPAL,” Dec. 2021. Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47674-informe-regional-ods-7-sostenibilidad-energetica-america-latina-caribe.

- SNE, Estrategia Nacional de Acceso Universal a la Energía. Panamá, 2022.

- J. Astudillo, M. T. Fernández, and C. Garcimartín, “La desigualdad de Panamá: Su carácter territorial y el papel de las inversiones públicas,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:199284128.

- M. Justo, “¿Cuáles son los 6 países más desiguales de América Latina?,” BBC News, Mar. 09, 2016. Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2016/03/160308_america_latina_economia_desigualdad_ab.

- X. Che, B. Zhu, and P. Wang, “Assessing global energy poverty: An integrated approach,” Energy Policy, vol. 149, p. 112099, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, and M. Roser, “Access to Energy,” Our World in Data. Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/energy-access.

- “Índice de Gini 2022 | Datosmacro.com,” Expansión. Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/demografia/indice-gini.

- Secretaría Nacional de Energía, Plan Energético Nacional 2015-2050, no. 6–348. Panamá: Gaceta Oficial Digital, 2016, p. 348. [Online]. Available: http://www.energia.gob.pa/plan-energetico-nacional/.

- K. Wang, Y.-X. Wang, K. Li, and Y.-M. Wei, “Energy poverty in China: An index based comprehensive evaluation,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 47, pp. 308–323, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. García-Ochoa and B. Graizbord, “Caracterización espacial de la pobreza energética en México. Un análisis a escala subnacional,” Economía, Sociedad y Desarrollo, vol. 16, no. 51, pp. 289–337, 2016, Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-84212016000200289.

- K. Kaygusuz, “Energy services and energy poverty for sustainable rural development,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 936–947, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Aiello and F. Lucantonio, “Energía para cocinar en América Latina y el Caribe: los desafíos de Paraguay - Energía para el Futuro,” Energía para el futuro - Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.iadb.org/energia/es/energia-para-cocinar-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe-desafios-de-paraguay/.

- F. Carvajal et al., “Más allá de la electricidad: Cómo la energía provee servicios en el hogar,” Jul. 2020. [Online]. Available: www.iadb.org/.

- V. Modi, M. Bazilian, and P. Nussbaumer, “Measuring energy poverty: Focusing on what matters,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 231–243, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Gargallo, “What is thermal comfort?” Accessed: Jan. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://sgarq.com/en/what-is-thermal-comfort/.

- Y. Vega, “Pobreza energética: Causas medición y posibles soluciones. Un estudio para Gipuzkoa,” Universidad del País Vasco, 2016.

- Secretaría Nacional de Energía, “‘Panamá el futuro que queremos.’” Panamá, p. 84, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.latinamerica.undp.org/content/rblac/es/home/library/poverty/-panama--el-futuro-que-queremos--plan-energetico-panama-2015-205.html.

- J. C. Schallenberg Rodríguez, Energías renovables y eficiencia energética. Instituto Tecnológico de Canarias, 2008.

- C. Amigo, R. Calvo, A. Cortés, and A. Urquiza, “Pobreza energética. El acceso desigual a energía de calidad como barrera para el desarrollo en Chile,” Nov. 2019.

- T. Horsley and J. Seymour, “Los siete tipos de problemas en el suministro eléctrico,” 2010. [Online]. Available: www.apc.com.

- S. A. Sy and L. Mokaddem, “Energy poverty in developing countries: A review of the concept and its measurements,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 89, p. 102562, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, “Manual para el diseño y la construcción de indicadores. Instrumentos principales para el monitoreo de programas sociales de México,” Mexico DF, 2013.

- M. Nardo, M. Saisana, S. Tarantola, A. Hoffmann, and E. Giovannini, “Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide,” Paris, 2008.

| Energy requirement dimension | Indicator | Measurement variable | Weighting (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lighting | Access to electricity | People have access to electricity. They have light bulbs in their homes | 20 |

| Cooking | Possession of cooking appliances | People have stoves in their homes | 12 |

| Access to modern fuels | Type of fuel used for cooking | 12 | |

| Food refrigeration | Possession of refrigerator | People have refrigerators at home | 12 |

| Thermal comfort | Possession of fan | People have fan at home | 7 |

| Knowledge, entertainment and communication | Entertainment media and knowledge | People have TV at home | 9.25 |

| People have PC or tablet with internet access | 9.25 | ||

| People have a radio at home | 9.25 | ||

| People have cellphones or they have telephone at home | 9.25 |

| Energy requirement dimension | Economic good | Satisfaction threshold (number of goods) | Economic good verification | Economic good level | Weighting obtained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lighting | Incandescent or fluorescent light bulb | Light bulbs ≥ 3 | |||

| Cooking | Gas or electric stove | Stove ≥ 1 | |||

| LPG tank | LPG ≥ 1 | ||||

| Food refrigeration | Refrigerador | Refrigerator ≥ 1 | |||

| Thermal comfort | Fan | Fan ≥ 1 | |||

| Knowledge, entertainment and communication | TV | TV ≥ 1 | |||

| PC or tablet with internet access | PC ≥ 1 | ||||

| Radio | Radio >=1 | ||||

| Cellphone or telephone | Cellphone or telephone ≥ 1 |

| Rango de Resultado | Interpretación |

|---|---|

| MEPIP = 0.20 | There is no EP in that household |

| 0.15 < MEPIP < 0.20 | Minimum EP, conditions must improve |

| 0.10 < MEPIP < 0.15 | Household is energy poor, conditions must improve |

| MEPIP < 0.10 | Extreme EP, urgent solution needed |

| Energy requirement dimension | Economic good | Satisfaction threshold (number of goods) | Economic good verification | Economic good level | Weighting obtained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lighting | Incandescent or fluorescent light bulb | Light bulbs ≥ 3 | 1 | 1 | 6.67 |

| Cooking | Gas or electric stove | Stove ≥ 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| LPG tank | LPG ≥ 1 | 1 | 3 | 12 | |

| Food refrigeration | Refrigerador | Refrigerator ≥ 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thermal comfort | Fan | Fan ≥ 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Knowledge, entertainment and communication | TV | TV ≥ 1 | 1 | 3 | 9.25 |

| PC or tablet with internet access | PC ≥ 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Radio | Radio >=1 | 1 | 3 | 9.25 | |

| Cellphone or telephone | Cellphone or telephone ≥ 1 | 1 | 3 | 9.25 |

| Communities | Max. value | Min. value | S | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guásimo | 0.1042 | 0.1737 | 0.0185 | 0.0360 | -0.1323 |

| Llano Grande Abajo | 0.0492 | 0.1243 | 0 | 0.0444 | -0.2221 |

| Los Aguilares | 0.09505 | 0.1768 | 0.0308 | 0.0387 | 0.0992 |

| La Tranquilla | 0.1004 | 0.17984 | 0.03084 | 0.0385 | 0.6942 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).