Submitted:

07 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

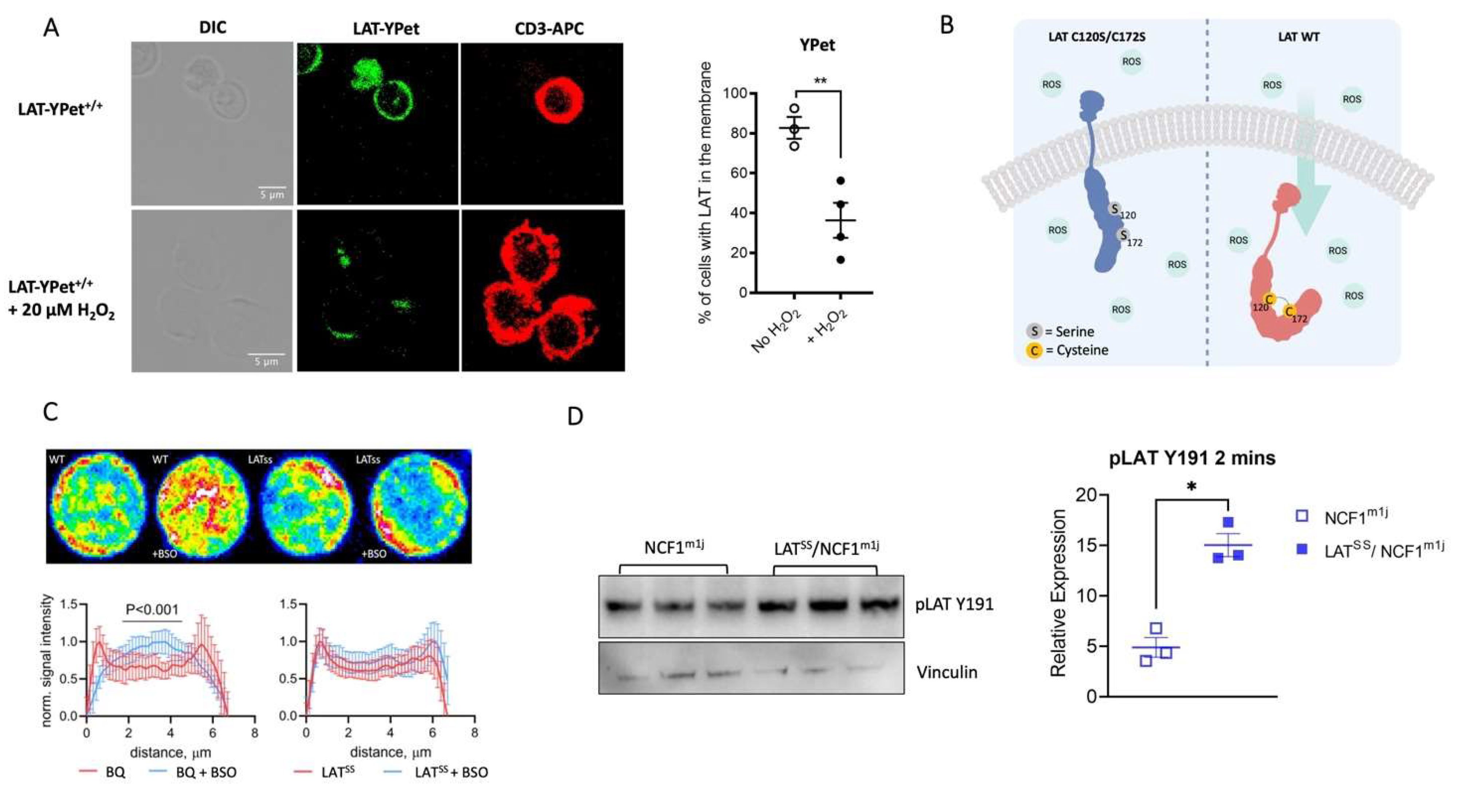

3.1. LAT phosphorylation is NOX2-dependent

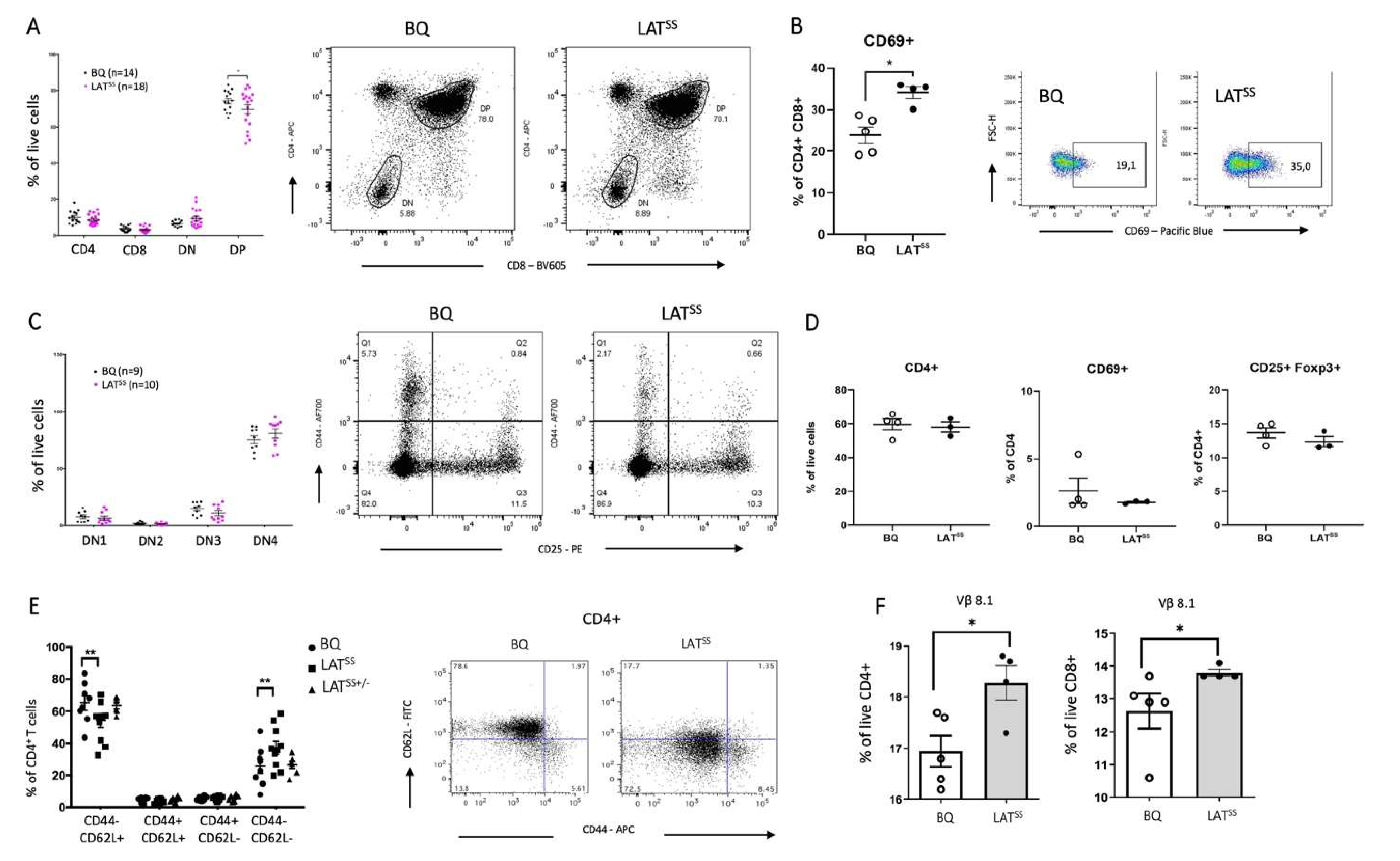

3.2. LATSS impacts thymic selection and peripheral T cells at steady state

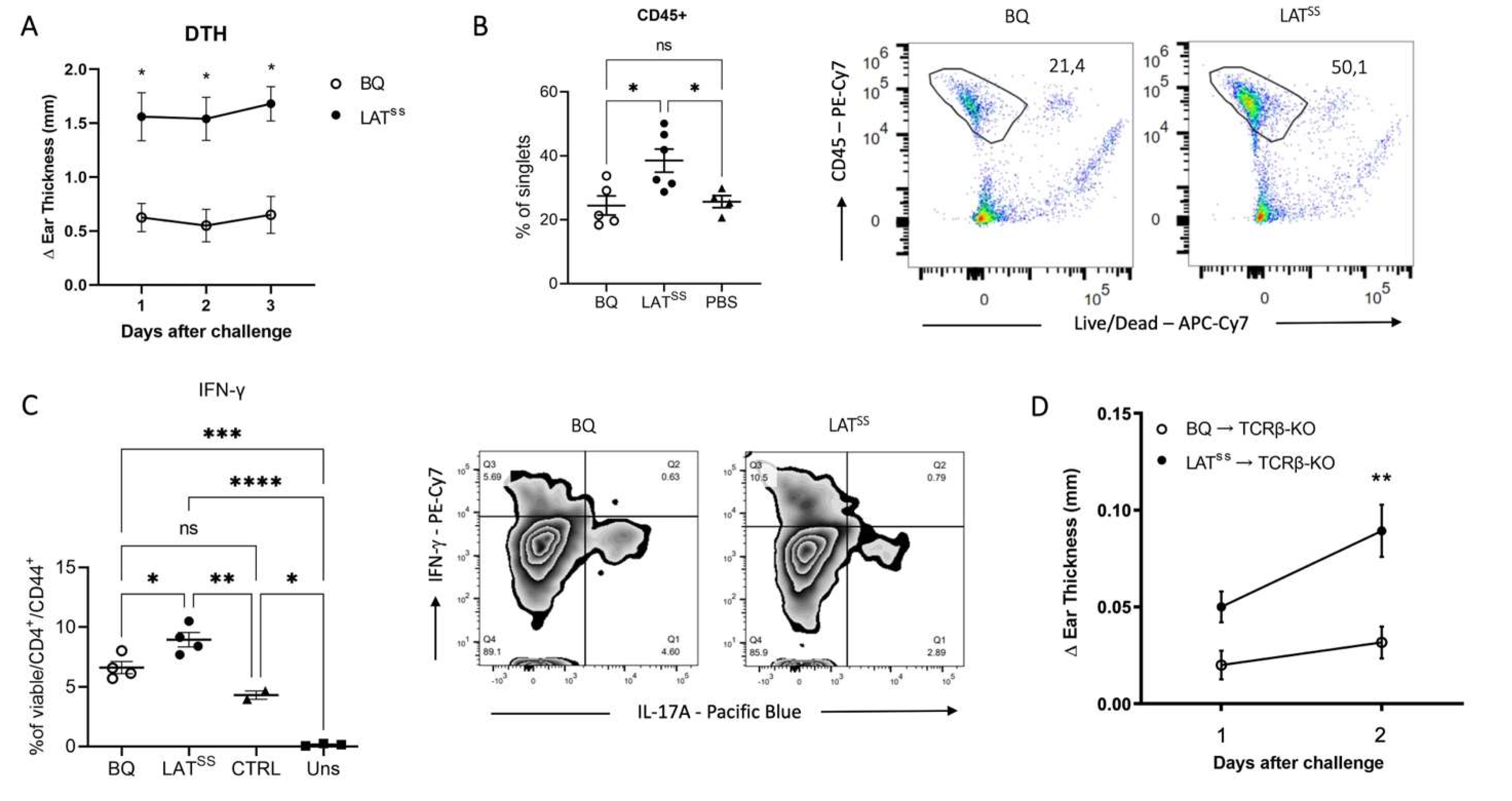

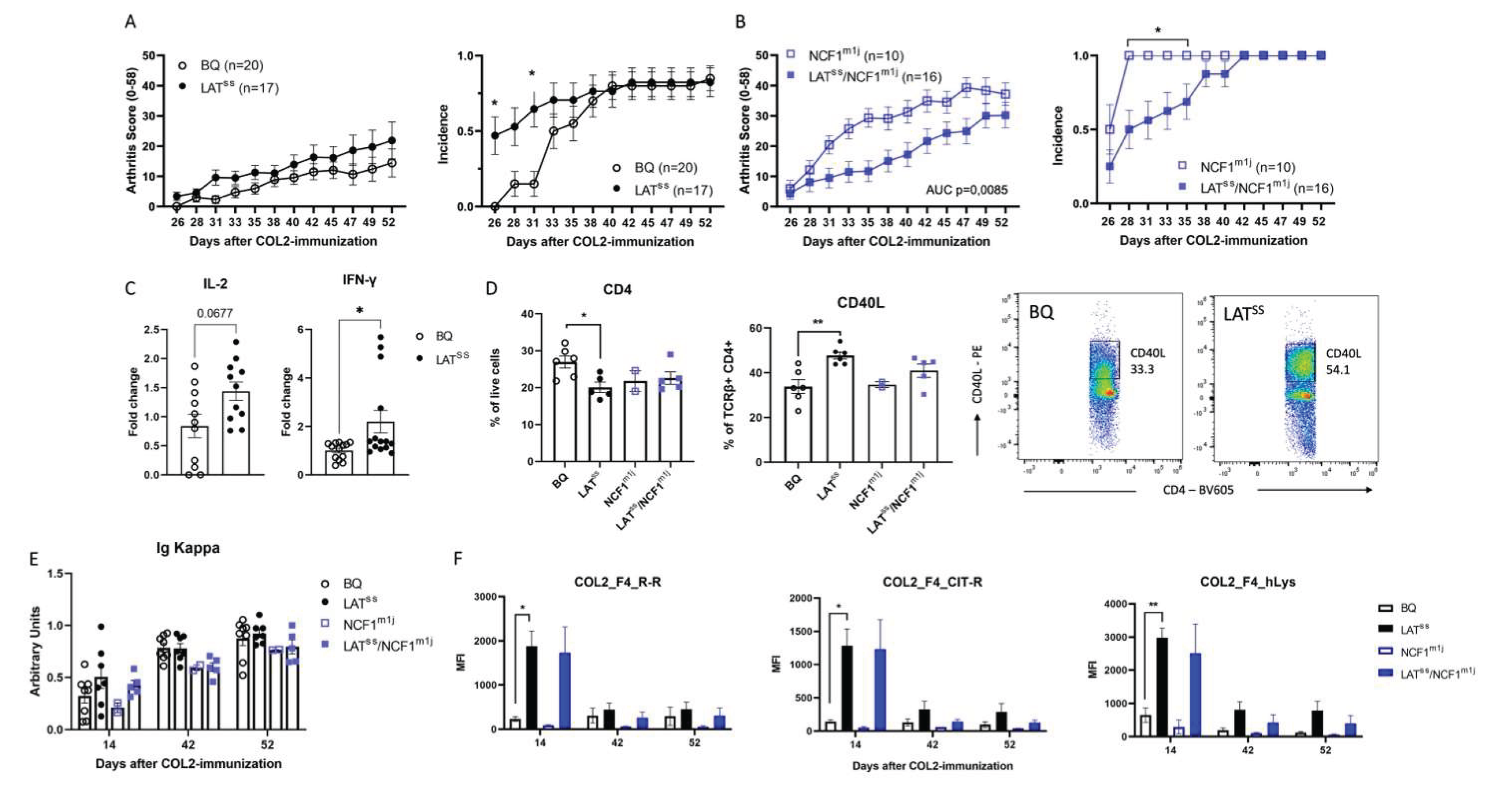

3.3. LATSS enhances T cell-dependent inflammation in DTH and CIA models

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- P. Olofsson, J. Holmberg, J. Tordsson, S. Lu, B. Åkerström, and R. Holmdahl, “Positional identification of Ncf1 as a gene that regulates arthritis severity in rats,” Nat Genet, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 25–32, Jan. 2003. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Olsson et al., “A single nucleotide polymorphism in the NCF1 gene leading to reduced oxidative burst is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 76, no. 9, pp. 1607–1613, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhao et al., “A missense variant in NCF1 is associated with susceptibility to multiple autoimmune diseases.,” Nat Genet, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 433–437, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J. Holmberg, B. T. Bäckström, J. Tordsson, and R. Holmdahl, “Enhanced autoimmunity, arthritis, and encephalomyelitis in mice with a reduced oxidative burst due to a mutation in the Ncf1 gene,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Olsson et al., “Copy number variation of the gene NCF1 is associated with rheumatoid arthritis.,” Antioxid Redox Signal, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 71–8, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Gelderman, M. Hultqvist, J. Holmberg, P. Olofsson, and R. Holmdahl, “T cell surface redox levels determine T cell reactivity and arthritis susceptibility.,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 103, no. 34, pp. 12831–6, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Gelderman et al., “Macrophages suppress T cell responses and arthritis development in mice by producing reactive oxygen species,” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 117, no. 10, pp. 3020–3028, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Chan, M. Iwashima, C. W. Turck, and A. Weiss, “ZAP-70: A 70 kd protein-tyrosine kinase that associates with the TCR ζ chain,” Cell, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 649–662, Nov. 1992. [CrossRef]

- S. Guy and D. A. A. Vignali, “Organization of proximal signal initiation at the TCR:CD3 complex,” Immunol Rev, vol. 232, no. 1, pp. 7–21, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang et al., “Essential Role of LAT in T Cell Development,” Immunity, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 323–332, Mar. 1999. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Sommers, R. K. Menon, A. Grinberg, W. Zhang, L. E. Samelson, and P. E. Love, “Knock-in Mutation of the Distal Four Tyrosines of Linker for Activation of T Cells Blocks Murine T Cell Development,” J Exp Med, vol. 194, no. 2, pp. 135–142, Jul. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Cruz et al., “LAT regulates γδ T cell homeostasis and differentiation,” Nat Immunol, vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 999–1008, Oct. 2003. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang et al., “Essential role of LAT in T cell development,” Immunity, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 323–332, 1999. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Sommers et al., “A LAT Mutation That Inhibits T Cell Development Yet Induces Lymphoproliferation,” Science (1979), vol. 296, no. 5575, pp. 2040–2043, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. Aguado et al., “Induction of T Helper Type 2 Immunity by a Point Mutation in the LAT Adaptor,” Science (1979), vol. 296, no. 5575, pp. 2036–2040, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Joachim et al., “Defective LAT signalosome pathology in mice mimics human IgG4-related disease at single-cell level,” Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 220, no. 11, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Balagopalan et al., “Enhanced T-cell signaling in cells bearing linker for activation of T-cell (LAT) molecules resistant to ubiquitylation,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 108, no. 7, pp. 2885–2890, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. Balagopalan et al., “Bypassing ubiquitination enables LAT recycling to the cell surface and enhanced signaling in T cells,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 2, p. e0229036, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Hundt, Y. Harada, L. De Giorgio, N. Tanimura, W. Zhang, and A. Altman, “Palmitoylation-Dependent Plasma Membrane Transport but Lipid Raft-Independent Signaling by Linker for Activation of T Cells,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 183, no. 3, pp. 1685–1694, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Reth, “Hydrogen peroxide as second messenger in lymphocyte activation,” Nature Immunology, vol. 3, no. 12. Nature Publishing Group, pp. 1129–1134, Dec. 01, 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. James et al., “Redox regulation of PTPN22 affects the severity of T-cell-dependent autoimmune inflammation,” Elife, vol. 11, May 2022. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- L. Simeoni and I. Bogeski, “Redox regulation of T-cell receptor signaling,” Biological Chemistry, vol. 396, no. 5. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, pp. 555–568, May 01, 2015. 01 May. [CrossRef]

- Pizzolla et al., “CD68-expressing cells can prime T cells and initiate autoimmune arthritis in the absence of reactive oxygen species,” Eur J Immunol, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 403–412, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Gringhuis, A. Leow, E. A. M. Papendrecht-van der Voort, P. H. J. Remans, F. C. Breedveld, and C. L. Verweij, “Displacement of Linker for Activation of T Cells from the Plasma Membrane Due to Redox Balance Alterations Results in Hyporesponsiveness of Synovial Fluid T Lymphocytes in Rheumatoid Arthritis,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 164, no. 4, pp. 2170–2179, Feb. 2000. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Gringhuis, E. A. M. Papendrecht-van der Voort, A. Leow, E. W. N. Levarht, F. C. Breedveld, and C. L. Verweij, “Effect of Redox Balance Alterations on Cellular Localization of LAT and Downstream T-Cell Receptor Signaling Pathways,” Mol Cell Biol, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 400–411, Jan. 2002. [CrossRef]

- R. Holmdahl, O. Sareila, L. M. Olsson, L. Bäckdahl, and K. Wing, “Ncf1 polymorphism reveals oxidative regulation of autoimmune chronic inflammation,” Immunol Rev, vol. 269, no. 1, pp. 228–247, 2016.

- Sareila, N. Jaakkola, P. Olofsson, T. Kelkka, and R. Holmdahl, “Identification of a region in p47phox/NCF1 crucial for phagocytic NADPH oxidase (NOX2) activation,” J Leukoc Biol, vol. 93, no. 3, pp. 427–435, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. J. T. Staal, M. T. Anderson, G. E. J. Staal0, L. A. Herzenberg, C. Gitler, and L. A. Herzenberg, “Redox regulation of signal transduction: Tyrosine phosphorylation and calcium influx (inflammatory cytoklnes/human immunodeficency virus infection),” 1994.

- T. S. P. Heng et al., “The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells,” Nat Immunol, vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 1091–1094, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. Chiocchia, M. Boissier, and C. Fournier, “Therapy against murine collagen-induced arthritis with T cell receptor V β -specific antibodies,” Eur J Immunol, vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 2899–2905, Dec. 1991. [CrossRef]

- C. Allen, “Delayed-type hypersensitivity models in mice,” Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1031, pp. 101–107, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Corthay et al., “Epitope glycosylation plays a critical role for T cell recognition of type II collagen in collagen-induced arthritis.,” Eur J Immunol, vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 2580–90, Aug. 1998.

- H. Burkhardt et al., “Epitope-specific recognition of type II collagen by rheumatoid arthritis antibodies is shared with recognition by antibodies that are arthritogenic in collagen-induced arthritis in the mouse,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 2339–2348, Sep. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu et al., “A subset of type-II collagen-binding antibodies prevents experimental arthritis by inhibiting FCGR3 signaling in neutrophils,” Nat Commun, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 5949, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, J. Tuncel, H. Yamada, S. Lu, P. Olofsson, and R. Holmdahl, “Pristane, a Non-Antigenic Adjuvant, Induces MHC Class II-Restricted, Arthritogenic T Cells in the Rat,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 176, no. 2, pp. 1172–1179, Jan. 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Yarosz and C. H. Chang, “Role of reactive oxygen species in regulating T cell-mediated immunity and disease,” Immune Network, vol. 18, no. 1. Korean Association of Immunologists, Feb. 01, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sena et al., “Mitochondria Are Required for Antigen-Specific T Cell Activation through Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling,” Immunity, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 225–236, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, M. Hultqvist, J. Holmberg, P. Olofsson, and R. Holmdahl, “T cell surface redox levels determine T cell reactivity and arthritis susceptibility,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 103, no. 34, pp. 12831–12836, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- J.-M. Carpier et al., “Rab6-dependent retrograde traffic of LAT controls immune synapse formation and T cell activation,” Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 215, no. 4, pp. 1245–1265, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Balagopalan et al., “c-Cbl-Mediated Regulation of LAT-Nucleated Signaling Complexes,” Mol Cell Biol, vol. 27, no. 24, pp. 8622–8636, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Necci, D. Piovesan, and S. C. E. Tosatto, “Critical assessment of protein intrinsic disorder prediction,” Nature Methods 2021 18:5, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 472–481, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Balagopalan, R. L. Kortum, N. P. Coussens, V. A. Barr, and L. E. Samelson, “The linker for activation of T Cells (LAT) signaling hub: From signaling complexes to microclusters,” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 290, no. 44. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Inc., pp. 26422–26429, Oct. 30, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Shen, M. Zhu, J. Lau, M. Chuck, and W. Zhang, “The Essential Role of LAT in Thymocyte Development during Transition from the Double-Positive to Single-Positive Stage,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 182, no. 9, pp. 5596–5604, May 2009. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- W. Paster et al., “GRB2-Mediated Recruitment of THEMIS to LAT Is Essential for Thymocyte Development,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 190, no. 7, pp. 3749–3756, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- JL et al., “Requirement for the leukocyte-specific adapter protein SLP-76 for normal T cell development,” Science, vol. 281, no. 5375, pp. 416–419, Jul. 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. C. van Oers, B. Lowin-Kropf, D. Finlay, K. Connolly, and A. Weiss, “αβ T Cell Development Is Abolished in Mice Lacking Both Lck and Fyn Protein Tyrosine Kinases,” Immunity, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 429–436, Nov. 1996. [CrossRef]

- E. H. Palacios and A. Weiss, “Function of the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, in T-cell development and activation,” Oncogene 2004 23:48, vol. 23, no. 48, pp. 7990–8000, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. P. P. Muyrers, G. Testa, and A. F. Stewart, “DNA cloning by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli,” Nat Biotechnol, vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1314–1317, Dec. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Bunting, K. E. Bernstein, J. M. Greer, M. R. Capecchi, and K. R. Thomas, “Targeting genes for self-excision in the germ line,” Genes Dev, vol. 13, no. 12, pp. 1524–1528, Jun. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, “The PDGFα receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites,” Development, vol. 124, no. 14, pp. 2691–2700, Jul. 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Pettitt et al., “Agouti C57BL/6N embryonic stem cells for mouse genetic resources,” Nat Methods, vol. 6, no. 7, pp. 493–495, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Bäcklund et al., “C57BL/6 mice need MHC class II Aq to develop collagen-induced arthritis dependent on autoreactive T cells,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 72, no. 7, pp. 1225–1232, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Mac-Daniel, M. R. L. Mac-Daniel, M. R. Buckwalter, P. Gueirard, and R. Ménard, “Myeloid cell isolation from mouse skin and draining lymph node following intradermal immunization with live attenuated Plasmodium sporozoites,” Journal of Visualized Experiments, vol. 2016, no. 111, p. 53796, 16. 20 May. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).