1. Introduction

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s 2011 Process Validation Guidance recommends continued process verification (CPV) during stage-3 process monitoring for drug manufacturers. In CPV, Shewhart control charts are employed as a statistical tool for monitoring process parameters and attributes (critical process parameters (CPPs), Key process parameter (KPPs), In-process controls (IPCs), and release specifications). In control charts, the calculated process average is utilized as the center line, and control limits are placed at distance k = ±3 short-term standard deviations (σ

R) away from the process average. The control chart, along with Nelson rules, serves as a tool for detecting out-of-control (OOC) data, defined as data that fall beyond the set control limits, and out-of-trend (OOT) data, defined as a group of data that forms a non-random pattern (shift in mean or increasing/decreasing pattern) [

1,

2,

3]. Although control charts are commonly applied across the industry to assess the statistical stability of a process, this approach introduces two types of risk: 1) false alarms, i.e., signals that are incorrectly identified as OOC or OOT when the data are actually belong to normal variability of the process itself, and 2) nuisance alarms, i.e., signals that are too small to have any impact on the process or lack sufficient statistical reliability [

4,

5]. In practice, small process variations and shifts are anticipated in many processes; therefore, control charts should detect moderate to large shifts that have more practical application rather than small or practically insignificant shift signals. Both high false alarm rates (FARs) and frequent nuisance alarms will reduce the reliability of control chart signals. Therefore, in this article, we provide a review on the current state of understanding on FARs associated with different Nelson rules, properties of data distributions (skewness and kurtosis) and their impact on control chart FAR, and methods for reducing FARs by optimizing the usage of Nelson rules and adjusting the value of k (the number of standard deviations from the mean) to accommodate variability and asymmetricity in data distribution.

2. Functional Modules of CPV

CPV program is driven by four functional models as identified in

Figure 1. CPV standard operating procedure (SOP): Drug manufactures define standard operating procedure for CPV as a guidance document that minimum should discuss 1) criteria for selection parameters to be monitored and trended 2) Frequency of cross functional team to perform data review meeting to monitor and analyze the trends of parameters and attributes, 3) Participants in the cross functional CPV data review meeting, 4) Discuss different statistical methods to assess the process capability and stability based on type of data distribution, 5) Method of controlled way of documenting the meeting minutes of CPV data review meeting, 6) Guidance on frequency of CPV report generation based on batch run rate, and 7) Guidance on reaction and response to signals from CPV data monitoring system.

CPV Plan: As per the recommendations in CPV SOP, CPV plan is generation for each drug substance intermediate stage, that list out all the parameters to be monitored and trended, type of data distribution and statistical method may be applied to assess the stability and capability.

CPV data review meeting: As recommended in the CPV SOP the parameters listed in CPV plans are charted and analyzed for signals of unexpected variation from historical performance as a cross functional team that includes a minimum participation from manufacturing, quality assurance (QA), manufacturing science and technology (MSAT) and quality control (QC). During the data review the identified statistical process control signals for OOT or OOC are disused on; 1. Magnitude of signal, 2. Statistical reliability of signal 3. Risk and severity on product quality or/and process performance, and decision on how to respond to the signal is warranted. If the signal is identified as nascence signal or not practically significant enough or not statistically significant enough, then no response or action is required. If the signal is identified to be real and has both practical and statistical strength but still not significant enough to impact product quality, then a technical evaluation may be warranted to understand the cause of variation, details of evaluation and results should be followed up in subsequent CPV meetings and findings should be documented in CPV meeting minutes. If the signal is identified to be real, has both practical and statistical significance, and the magnitude is significant enough to potentially impact the product quality, then an investigation under quality management system may be required.

CPV reports: CPV reports are generated either annually or semiannually or quarterly basis based on batch run rate. Here all parameters and attributes listed in CPV pans are monitored and trended along with summary stability and capability discussions along with all the CPV data review meeting minutes. Recommendations from the CPV reports on changes in the frequency of monitoring or retiring parameters from CPV monitoring may be implemented to CPV plans.

3. False Alarm Rate in Control Charts

In 1924, Walter Andrew Shewhart introduced the concept of data analysis using control charts, which was later adopted by the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industries when regulatory agencies requested that drug manufacturers to perform CPV [

6]. In control charts or XBar charts, the center line is placed at the average, and control limits are typically placed at k standard deviations from the average. Typically, k = 3 is utilized, for which there is a 0.135% probability that any data point belonging to a normally distributed population will fall outside ±3 standard deviations (σ). This approach gives an interval of expected future observations if the process does not change. If observations are within these limits, it can be assumed that the validated state is maintained; if observations are outside these limits, the mean and/or standard deviation has probably changed, potentially requiring attention. σ is often calculated as a short-term σ

R, which causes the limits to be more sensitive to drift, as shown in Equation (1).

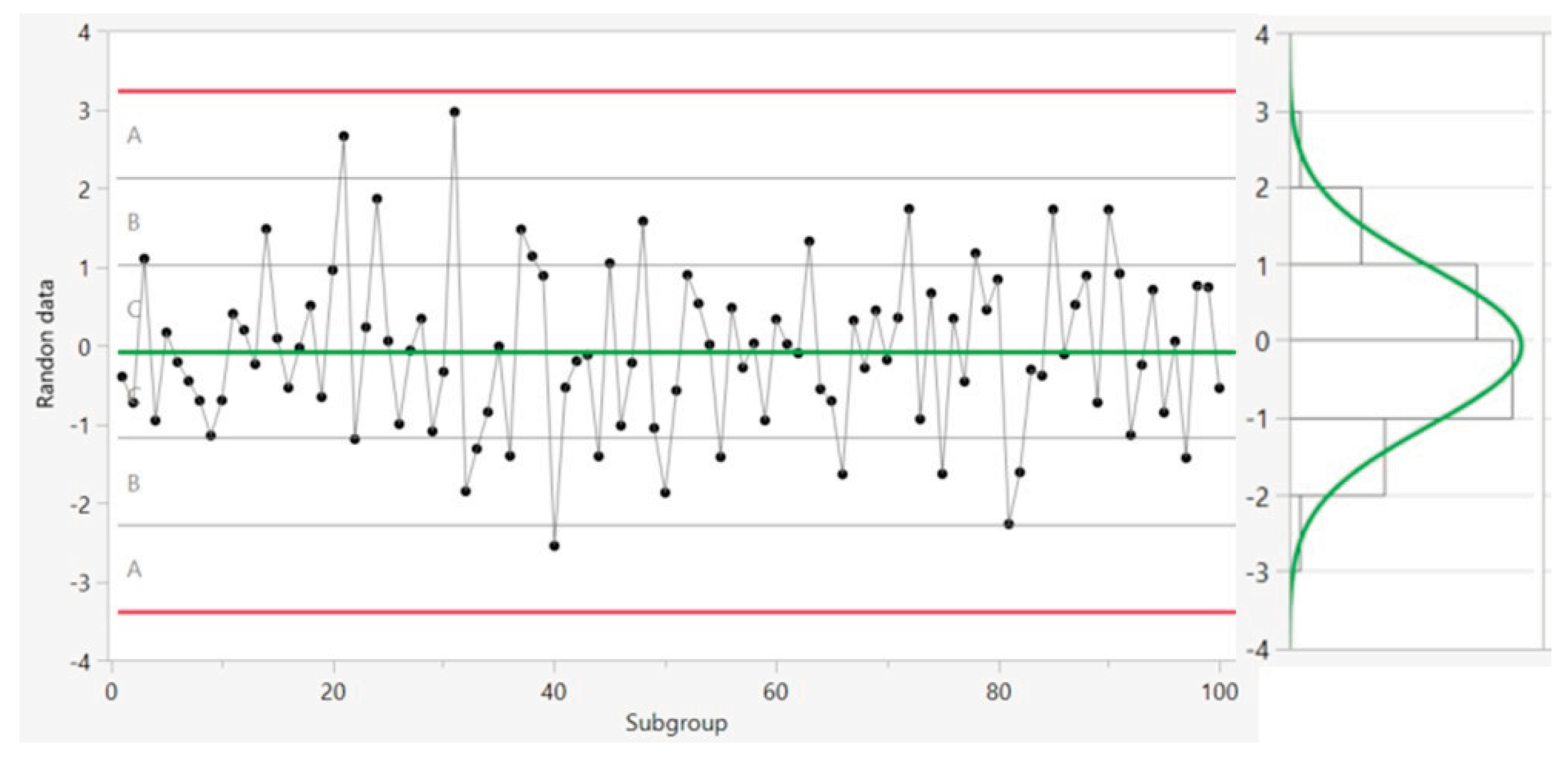

The control chart is divided into six zones based on distance from the center line as shown in

Figure 2. Each zone is one standard deviation (σ

R) wide. The 3-σ

R limits on both sides of the center line show the upper control limit and lower control limit. The 2-σ

R limits indicate the upper and lower warning limits, and the 1-σ

R limits on each side of the center line are the upper and lower one-sigma limits. Control charts, along with Nelson rules 1–8 (summarized in

Table 1), are used to monitor process control and process stability based on the location of data in different zones, the frequency of occurrence of any patterns, and the distance from the mean [

6]. To correctly apply the Nelson test rule signals in a control chart, it is imperative to understand the normal acceptable probability for a data point to fall within or outside of the control chart zones. For instance, for a hypothetical mean µ=0 and standard deviation σ=1, the probability that normally distributed data will fall between -3 SD and +3 SD is given by Equation (2).

Optimizing the Number of Nelson Test Rules Used in Control Chart

In statistical process control, the FAR or rate of type I errors, often identified by the symbol α, indicates the likelihood that data will be falsely identified as an abnormal signal when the data actually correspond to the normal variability of the process.

Table 1 summarizes the different Nelson rules and their purposes, along with probability of a false alarm for each Nelson rule [

7].

The FARs from all eight Nelson rules identified in

Table 1 sum up to 2.65%. Although it might be intriguing to use all eight Nelson test rules, Nelson (1984) suggested keeping the FAR below 1% [

6]. Nelson also stated that tests 5 and 6 should be included only when there is an economical desire to have an early warning, as these rules increase the FAR. Tests 7 and 8 are used to diagnose stratifications and to identify subgroups taken from two different means. Therefore, test rules 7 and 8 have application only when subgroups are used in the control chart. However, in the biopharmaceutical industry, testing is typically performed for a single sample taken from a batch; therefore, unless multiple samples are tested and averaged for the single value reported in the control chart, rules 7 and 8 do not add value for data monitoring and trending. Adhibhatta et al. (2017) showed that Nelson tests 1, 2, and 3 are adequate for monitoring OOC and OOT data, with a combined false alarm probability of 0.94 [

8]. Thus, in an effort to limit the FAR to < 1.0% and considering the practical application of test rules for biopharmaceuticals, it is recommended that only Nelson test rules 1–3 be utilized in a control chart for biopharmaceutical application.

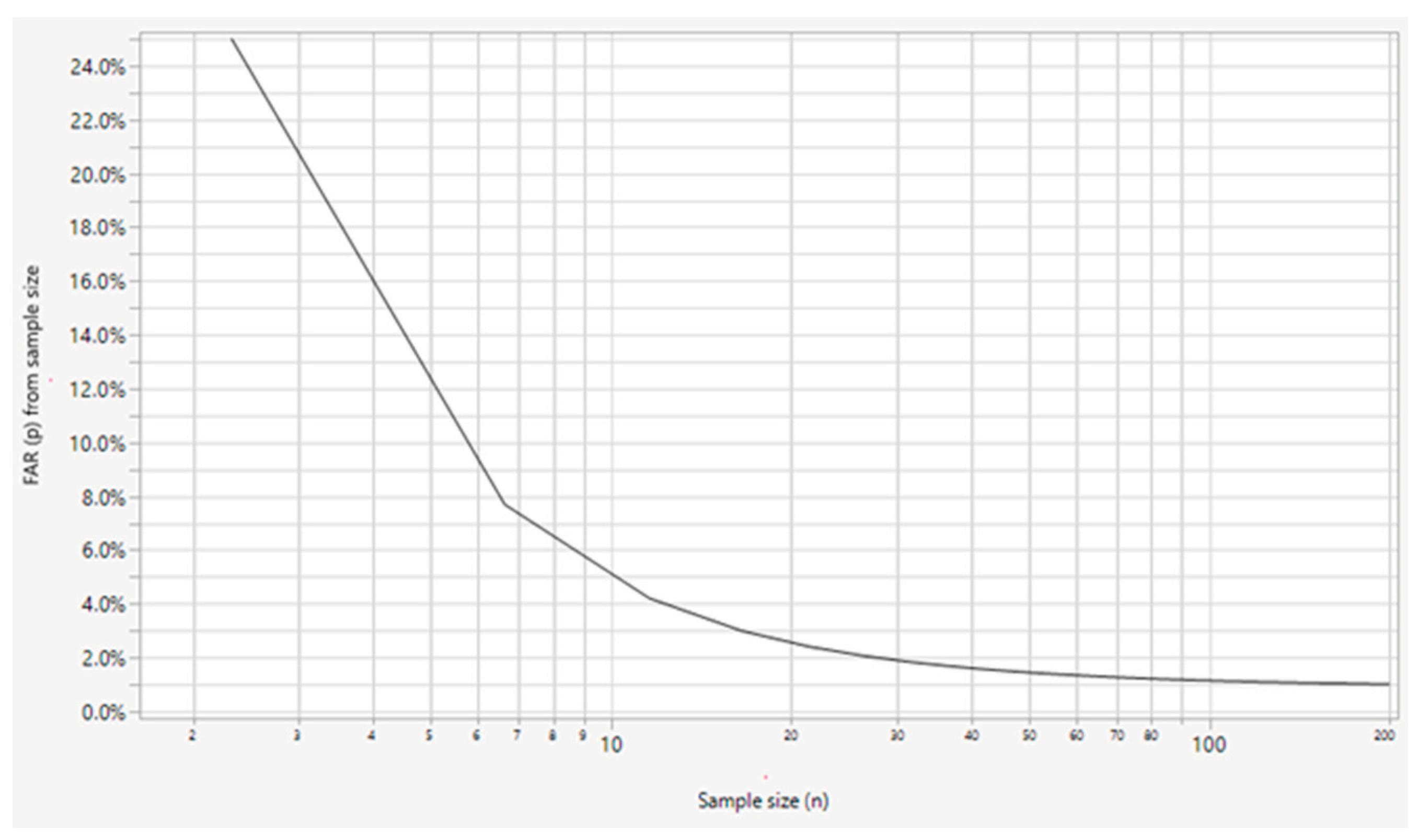

4. FAR in Out-of-Control Signal from Limited Sample Size

OOC data are detected via Nelson rule 1 when a single data point falls outside 3 SD from the mean, with the assumptions that the data are normally distributed, the underlying true population mean (µ) and population standard deviation (σ) are known, and there is no error due to sampling variability. However, for new products, based on the batch run rate, there is a high likelihood of having a very limited sample size during the first couple of years. For small sample sizes, the replacement of the population means with the sample mean (x̄) and of the population standard deviation with the sample standard deviation (SD) and the establishment of control limits will lead to an increased FAR [

9,

14]. The risk of an increased FAR due to a limited sample size in control limits has been calculated by Bischak et al. (2007) as a function of the number of standard deviations from the mean (k), the number of observations (n), and the size of the subgroup in each observation (m). As discussed above, biopharmaceutical companies typically perform testing on a single sample taken from a batch; therefore, two subsequent lots are used to calculate the short-term standard deviation, and hence, m is assumed to be 2. The FAR for a limited number of observations or sample size (n) is expressed in Equation (3). Here, (C

4) is an unbiased estimator of standard deviation. The uncertainty that arises from using the sample standard deviation (SD) instead of the underlying true population standard deviation is compensated for by using an unbiased standard deviation estimator (C

4) calculated as a function of subgroup size, as expressed in Equation (4) [

10,

13]. Here, Φ is the cumulative normal probability density function.

The probability of a false alarm caused by utilizing a limited sample size when setting the control limit at k = 3 (i.e., 3 standard deviations from the mean) is calculated by applying Equations (3) and (4), as shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that the reduction in FAR follows an exponential decay curve; we observe a sharp drop below 5% for a sample size of n = 10, followed by a plateau after approximately n = 30 and a further decrease below 1% at n = 100. Therefore, we recommend using a run chart when the sample size is ≤10, using the calculated control limits as tentative control limits for monitoring and updating control limits for sample sizes of 30–100, and using fixed long-term control limits when the sample size is ≥100. Another alternative solution for mitigating the uncertainty in the calculation of control limits for a small sample size (n < 30) is the use of prediction limits. Prediction limits account for the estimation uncertainty that arises from using the sample standard deviation (SD) by replacing the normal quantile with the t quantile at (n–1) degrees of freedom and also accommodates the uncertainty due to the sample mean by including the standard error of the mean, as expressed in Equation (5).

5. FAR in Out-of-Control Signal from Skewed and Heavy Tailed Distribution

The application of Nelson test rules in a control chart is based on a normality assumption. However, if the data are severely skewed or if the variance in the data is excessively broad with a heavy-tailed distribution, this can lead to an increase in the FAR. The asymmetry and tail length in data with reference to a normal distribution are measured as skewness (K

3) and kurtosis (K

4), respectively [

14].

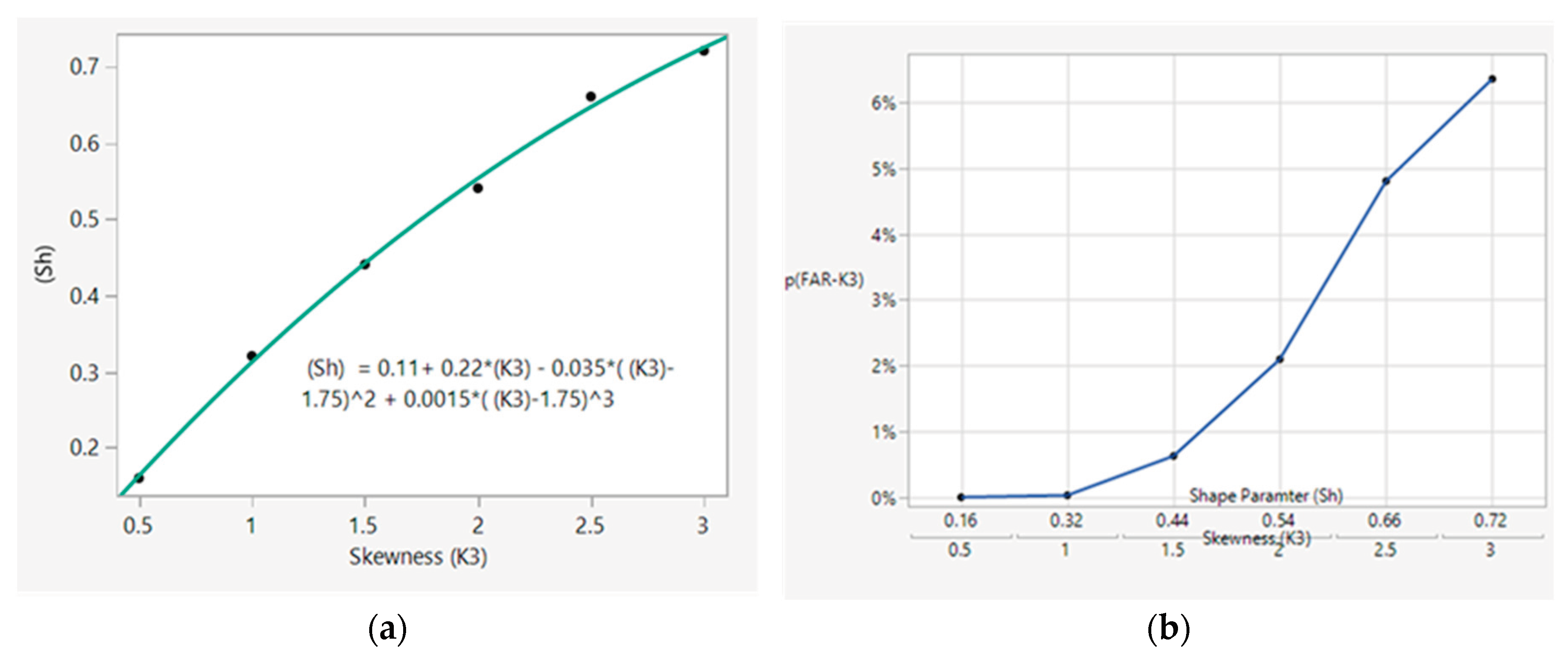

5.1. Modelling FAR from Asymmetric Data Distribution

Control charts are based on the assumption that a data distribution is symmetric on either side of the center average line. However, in practice, the data distribution may be off-centered or asymmetric. Skewness (K

3) is a measure of the degree of asymmetry observed in a data distribution. A distribution can have either right-skewed or left-skewed data or no skew at all. A right-skewed distribution is longer on the right side of its peak, and a left-skewed distribution is longer on the left side of its peak. Skewness in a distribution can be calculated from Equation (6) [

11]. A highly skewed distribution can lead to a high FAR in control chart signals. The probability distribution function of a skewed data spread can be modeled by a log-normal distribution [

12], which is delineated by two parameters, namely, the shape (Sh) or mean (µ) and the scale parameter (Sc) or standard deviation (σ). The FAR caused by skewness in a data distribution with control limits placed at ± 3 (σ

R) from the mean can be determined by knowing the relationship between the skewness value and shape parameter (Sh). A correlation expression between skewness and shape parameter (Sh) was developed from the data reported by Derya et al. (2012), as shown in

Figure 4A [

12]. Assuming a scale parameter of Sc = 0 with the shape parameter (Sh) calculated via the correlation shown in

Figure 4A, the FAR for various degrees of skewness can be calculated via Equation (7), as shown in

Figure 4B. Here, k is the number of standard deviations from the mean; for control limits placed at 3 SDs from the mean, k = 3.

Figure 4B shows that a skewness below 1.5 keeps the control limit signal at an acceptable FAR of <1.0%.

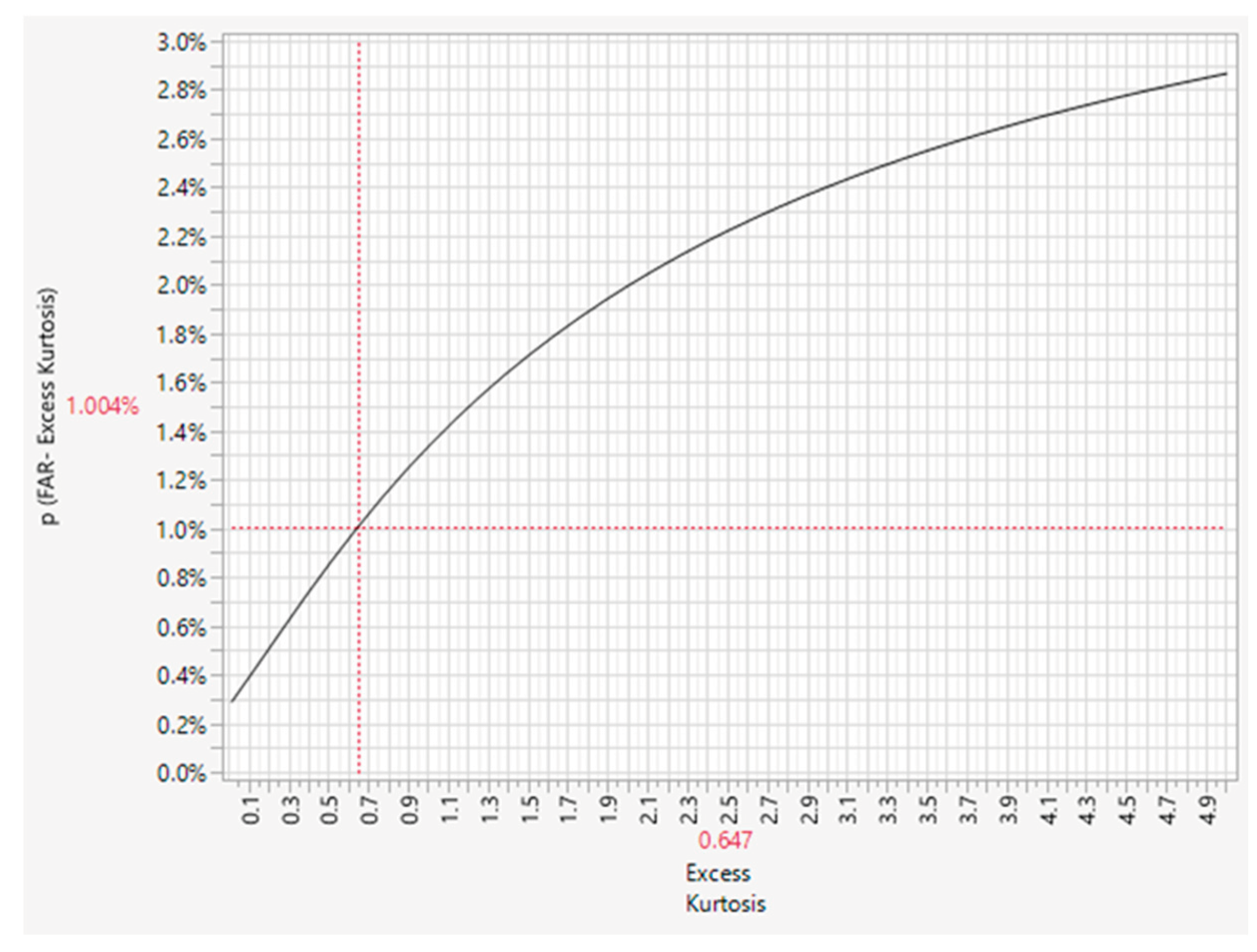

5.2. Modelling FAR from Heavy Tailed Distribution

Kurtosis is a measure of whether data are heavy-tailed or light-tailed relative to a normal distribution. Data distribution with high kurtosis tends to have heavy tails or outliers. In contrast, data distribution with low kurtosis tends to have light tails or a lack of outliers. A standard normal distribution has a kurtosis of zero. The kurtosis (K

4) can be calculated from Equation (8) [

11,

14]. A positive kurtosis indicates a "heavy-tailed" distribution. A t-distribution has fatter tails than a normal distribution. Therefore, a t-distribution can be used as a model to represent kurtosis, which will allow for a more realistic calculation of the FAR from excess kurtosis [

11]. The FAR caused by kurtosis can be modeled via a t-distribution, as expressed in (9) and as shown in

Figure 5, by knowing the relationship between kurtosis (K

4) and degrees of freedom (df) for the t-distribution. Here, k is the number of standard deviations from the mean; for control chart limits placed at 3 SDs from the mean, k = 3. df is the number of degrees of freedom for the t-distribution, and df

t.dist can be calculated from the kurtosis (K

4) in the data distribution, as expressed in Equation (10) [

15].

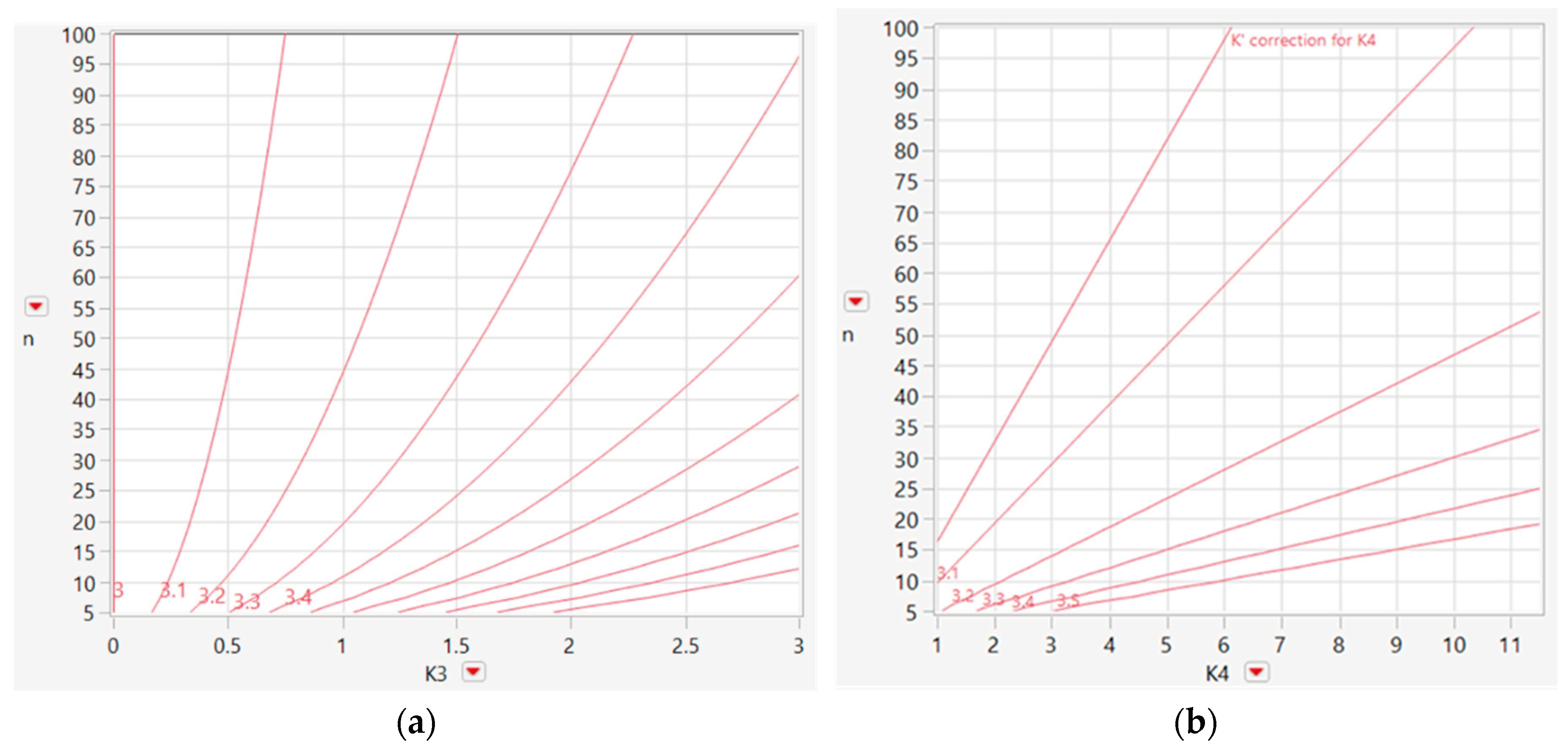

Adjustment to “k” to accommodate the skewness and heavy tail distribution

Braden et al. (2022) showed that the FAR for a severely skewed or heavy-tailed distribution can be reduced by replacing the control limits at k = 3 (σR) from the mean with limits based on adjusted k values (k’), as expressed in Equations (11) and (12), to accommodate skewness or heavy tails in the data distribution. Branden also stated that Equations (11) and (12) are valid only when the skewness or kurtosis of the distribution meets the criteria expressed in Equation (13) [

14]. The factor adjustment for skewness and kurtosis is shown in

Figure 6.

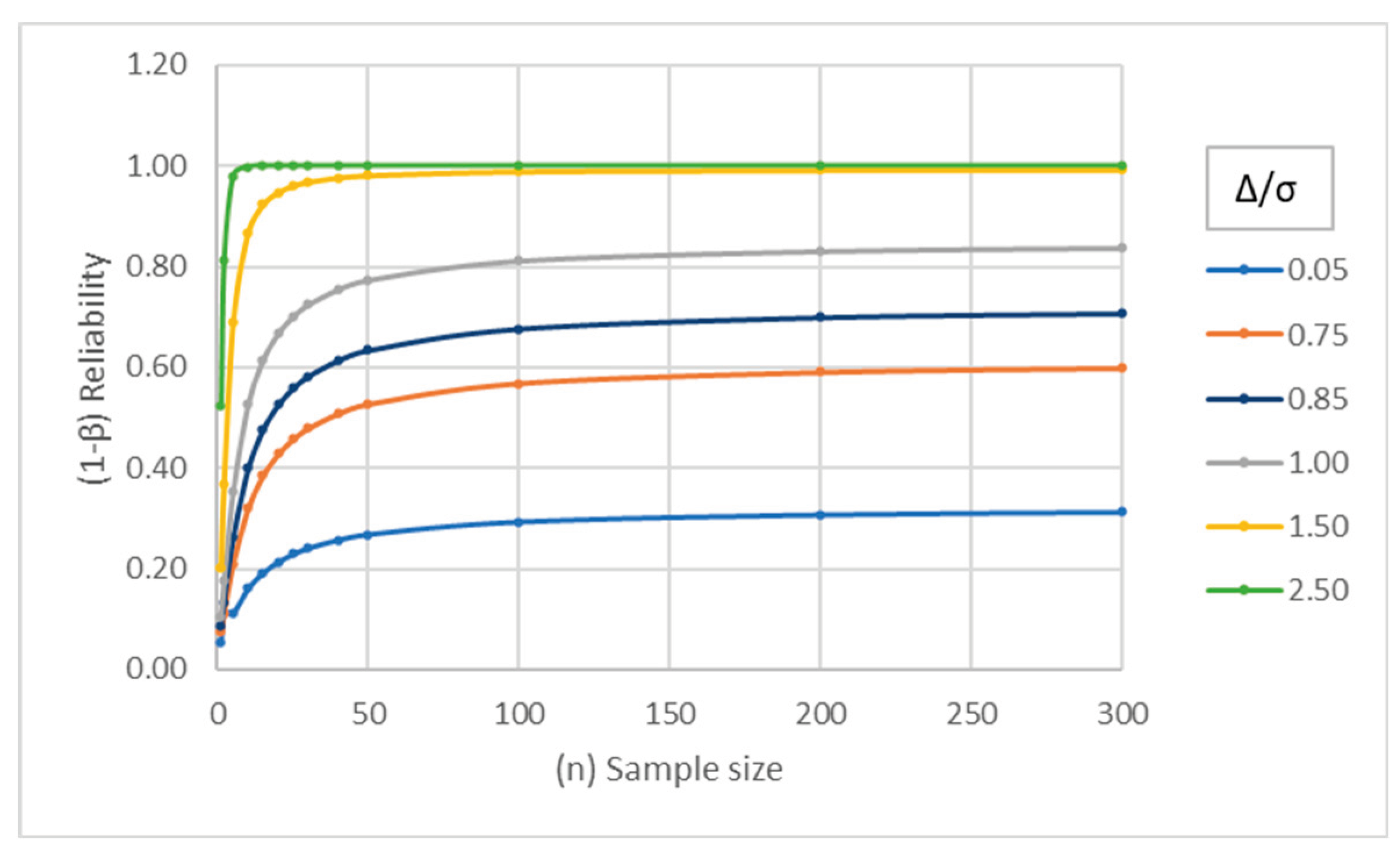

6. Nuisance Signal from Nelson Rule 2 and Its Reliability

Nelson rule 2 stating nine subsequent data points on side of the center line used to detect shift in the mean is attributed to nuisance signal as the magnitude of shift in the mean can be potentially insignificant. Therefore, when a signal is identified for Nelson rule 2, it is imperative that the strength of the signal be assessed against the magnitude of the shift. Wheeler (2017) classified Nelson test rule 2 signals as small shift when magnitude of signal is less than 1.5 standard deviation from mean (Δ/σ). An intermediate shift when signal is 1.5 ≥ (Δ/σ) ≥ 2.5, and as a large shift when the magnitude of signal (Δ/σ) > 2.5 [

16]. The reliability of the signal for the desired shift effect can be calculated from the type II error. In control charts, the (β) value or type II error indicates the probability of a true signal going undetected. The widely acceptable minimum probability for β is 0.20[

17], which indicates a reliability (1–β) of 100% – 20% = 80%. The relationship between sample size, type I error (α), type II error (β), and (Δ/σ) for the mean is expressed as a two-sided limit and one-sided limit, as shown in Equations (14) and (15) [

21].

Here, nT is the total sample size in the analysis, where nT = nhis + nsis. nhis is the number of historic samples, and nSis is the number of data points on one side of the center line showing a positive signal for Nelson test rule 2; therefore, nSis = 9. df = nsig + nhis – 2, which represents the degrees of freedom, and t(1-α, df) represents the inverse of the cumulative t-distribution at 1 – α and df.

Here, an acceptable value of the significance (α) value or type I error is often set at 0.05 [

18], indicating a 5% probability of falsely identifying a signal as positive when the data still corresponds to normal variability within the process. In this case, the statistical confidence (1 – α) is 100% – 5% = 95%.

The detectability/shift from the mean (Δ/σ) is the acceptable distance from the mean, expressed as a number of standard deviations. The FDA guidance document on “statistical review and evaluation” states that a (Δ/σ) value of 1.5 at 90% confidence (1 – α) is adequate to conclude equivalence between two groups [

19,

20].

Equations (14) and (15) for the sample size are rearranged to solve for the power of estimation, where t.dist is the cumulative distribution function for a one-sided or two-sided t-distribution, respectively. According to Cohen (1988), the generally accepted minimum power (1 – β) is 80% for a confidence (1 – α) of 95% [

17].

Figure 6 shows the reliability of a signal for Nelson rule 2 for different combinations of the shift from the mean (Δ/σ) and historic sample size. Assuming a historic data sample size of n

his = 30 (The number 30 is selected because t distribution approaches normal distribution at sample size of 30) and a sample size of n

sis = 9 on one side of the center line for the Nelson test rule-2 signal, the reliability is calculated via Equation (14) for different values of the shift from the mean (Δ/σ), as shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 7 demonstrates that if the observed shift in the mean is ≤1 SD, then the signal can be considered as a nuisance signal without sufficient reliability.

7. Conclusions

Challenges in CPV review sessions include assessing a control chart signal for reliability and deciding whether to initiate an investigation followed by action for a corrective or preventive action. However, control charts are susceptible to false alarms and nuisance alarms. Trusting incorrect signals from the control chart and initiating quality control actions can lead to a waste of resources and time. Therefore, it is imperative to understand false alarm probabilities in control charts in association with different Nelson test rules. In this article, we reviewed the current state of understanding on FARs inherent to control charts and the impact on FARs of data distributions that deviate from normal distribution assumptions. We also discussed methods for optimizing the use of control charts by selecting the Nelson test rules to be applied and correcting the number of sigma factors (k) used for calculating control limits to accommodate skewness and kurtosis in a data distribution to reduce the FAR and nuisance signals and to improve the reliability of data trending and monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.; methodology, N.M.; T.C.; validation, L.S.R., writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, T.C; L.SR; M.D.; supervision, M.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted at the AGC Biologics Boulder CO.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Process Validation: General Principles and Practices. 2011. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Process-Validation--General-Principles-and-Practices.pdf.

- PDA Technical Report No. 59 (TR 59) Utilization of Statistical Methods for Production Monitoring (single user digital version). Available online: https://www.pda.org/bookstore/product-detail/1842-tr-59-utilization-of-statistical-methods.

- Heigl, N.; Schmelzer, B.; Innerbichler, F.; Shivhare, M. Statistical Quality and Process Control in Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing - Practical Issues and Remedies. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology. 2021, pdajpst.2020.011676. [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.M.; Woodall, W.H.; Lowry, C.A. The Use (and Misuse) of False Alarm Probabilities in Control Chart Design. 1992, 155–168. [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; Philpot, J. W.; Clement, J. False Signal Rates for the Shewhart Control Chart with Supplementary Runs Tests. Journal of Quality Technology. 1991, 23(3), 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L. S. The Shewhart Control Chart—Tests for Special Causes. Journal of Quality Technology. 1984, 16(4), 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.; Bunder, M.; Gulati, C.; Onizawa, T. The Probability of an Out-of-Control Signal from Nelson’s Supplementary Zig-Zag Test. Journal of Statistical Theory and Practice 2010, 4(4), 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhibhatta, A.; DiMartino, M.; Falcon, R.; Haman, E.; Legg, K.; Payne, R.; Pipkins, K.R.; Zamamiri, A. Continued Process Verification (CPV) Signal Responses in Biopharma. ISPE. 2017. Available online: https://ispe.org/pharmaceutical-engineering/january-february-2017/continued-process-verification-cpv-signal.

- Bischak, D. P.; Trietsch, D. The Rate of False Signals in x̄ Control Charts with Estimated Limits. Journal of Quality Technology 2007, 39(1), 54–65. Available online: https://prism.ucalgary.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/dae8e651-1a93-4337-a3a1-1c2dbe3ae66c/content. [CrossRef]

- Trietsch, B.; Bischak, B. The Rate of False Signals for Control Charts with Limits Estimated from Small Samples. Journal of Quality Technology 2007, 39(1), 52–63. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2515703_The_Rate_of_False_Signals_for_Control_Charts_with_Limits_Estimated_from_Small_Samples.

- Groeneveld, R. A.; Meeden, G. Measuring Skewness and Kurtosis. The Statistician 1984, 33(4), 391–399. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2987742. [CrossRef]

- Derya, K.; Canan, H. Control Charts for Skewed Distributions: Weibull, Gamma, and Lognormal. Metodološki zvezki 2012, 9(2), 95–106. Available online: http://mrvar.fdv.uni-lj.si/pub/mz/mz9.1/karagoz.pdf.

- Munoz, J.; Moya Fernandez, P. J.; Alvarez, E.; Blanco-Encomienda, F. An Alternative Expression for the Constant C4[N] with Desirable Properties. Scientia Iranica. 2020, 0(0), 3388–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braden, P.; Matis, T. Cornish–Fisher-Based Control Charts Inclusive of Skewness and Kurtosis Measures for Monitoring the Mean of a Process. Symmetry. 2022, 14(6), 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, K. L.; Little, R. J. A.; Taylor, J. M. G. Robust Statistical Modeling Using The t Distribution. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1989, 84(408), 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D J.; Stauffer, R. When Should We Use Extra Detection Rules? Using process behavior charts effectively. Quality Digest. 2017, 322, 1–14. Available online: https://www.spcpress.com/pdf/DJW322.Oct.17.Using%20Extra%20Detection%20Rules.pdf.

- Muralidharan, N. Process Validation: Calculating the Necessary Number of Process Performance Qualification Runs. Bioprocess International. 2023, 21(5), 37–43. Available online: https://bioprocessintl.com/analytical/upstream-validation/process-validation-calculating-the-necessary-number-of-process-performance-qualification-runs/.

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Type I and Type II Errors in Statistical Decision. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 2015, 40(3), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durivage, M. How To Establish Sample Sizes for Process Validation Using Statistical Tolerance Intervals. Bioprocess Online 2016. Available online: https://www.bioprocessonline.com/doc/how-to-establish-sample-sizes-for-process-validation-using-statistical-tolerance-intervals-0001.

- Weng, Y.; Shen, M. Statistical Review and Evaluation. US Food and Drug Administration. 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/105013/download.

- NIST/SEMATECH. Engineering Statistics Handbook. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2012. 2012. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).