Submitted:

06 March 2024

Posted:

07 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vivo Toxicity of Antibiotic Compounds

2.2. In Vivo Challenge and Antibiotic Therapy

Results

2.3. Microbiological Findings

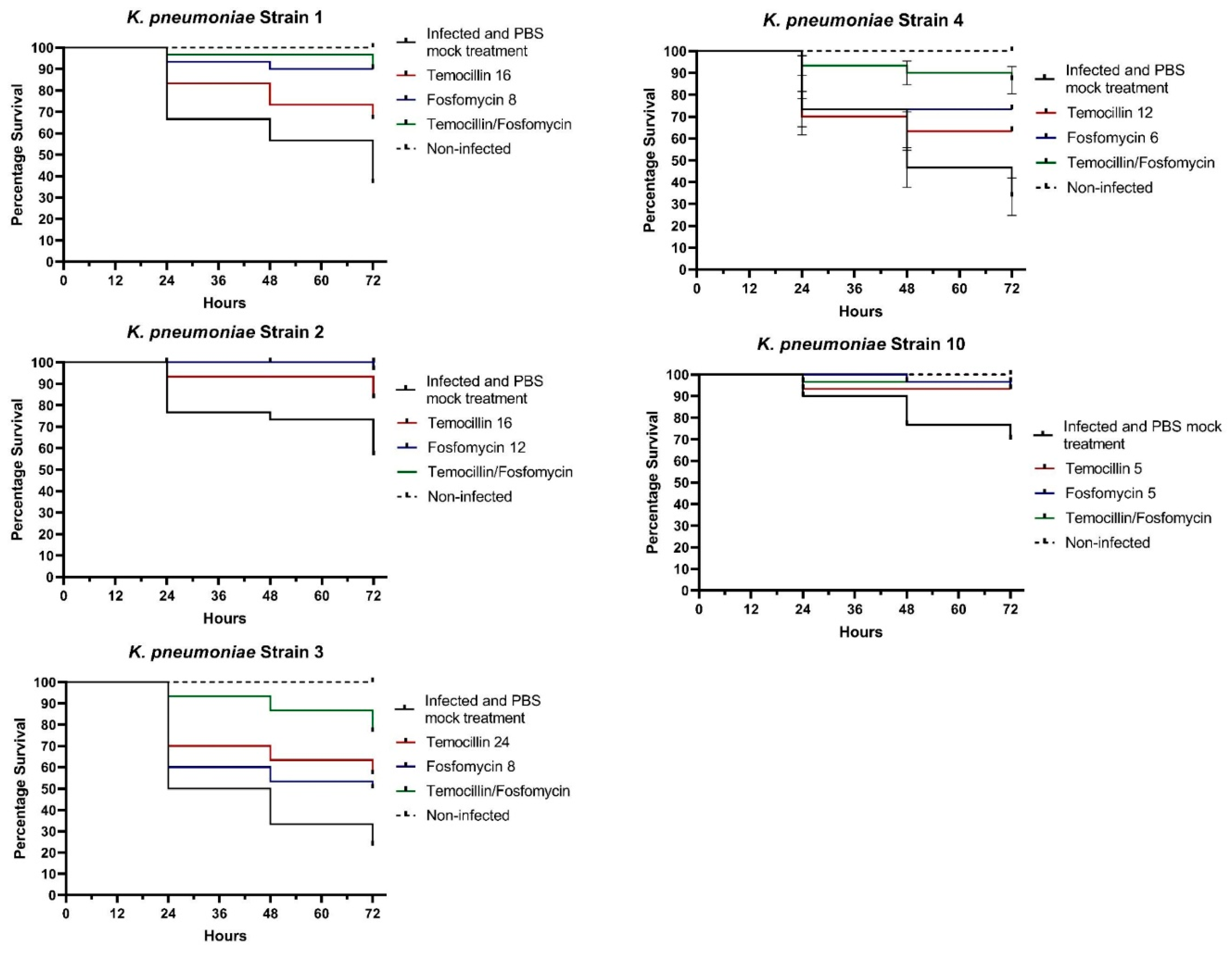

2.4. In Vivo Findings

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tumbarello, M.; Viale, P.; Viscoli, C.; Trecarichi, E.M.; Tumietto, F.; Marchese, A.; Spanu, T.; Ambretti, S.; Ginocchio, F.; Cristini, F.; et al. Predictors of Mortality in Bloodstream Infections Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. Pneumoniae: Importance of Combination Therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable Deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years Caused by Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A Population-Level Modelling Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G.; Carbonara, S.; Marino, A.; Di Caprio, G.; Carretta, A.; Mularoni, A.; Mariani, M.F.; Maraolo, A.E.; Scotto, R.; et al. Mortality Attributable to Bloodstream Infections Caused by Different Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli: Results From a Nationwide Study in Italy (ALARICO Network). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Bassetti, M.; Tiseo, G.; Giordano, C.; Nencini, E.; Russo, A.; Graziano, E.; Tagliaferri, E.; Leonildi, A.; Barnini, S.; et al. Time to Appropriate Antibiotic Therapy Is a Predictor of Outcome in Patients with Bloodstream Infection Caused by KPC-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, S.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Maraolo, A.E.; Viaggi, V.; Luzzati, R.; Bassetti, M.; Luzzaro, F.; Principe, L. Resistance to Ceftazidime/avibactam in Infections and Colonisations by KPC-Producing Enterobacterales: A Systematic Review of Observational Clinical Studies. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 25, 268–281.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Carrara, E.; Retamar, P.; Tängdén, T.; Bitterman, R.; Bonomo, R.A.; de Waele, J.; Daikos, G.L.; Akova, M.; Harbarth, S.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Guidelines for the Treatment of Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli (endorsed by European Society of Intensive Care Medicine). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupia, T.; De Benedetto, I.; Stroffolini, G.; Di Bella, S.; Mornese Pinna, S.; Zerbato, V.; Rizzello, B.; Bosio, R.; Shbaklo, N.; Corcione, S.; et al. Temocillin: Applications in Antimicrobial Stewardship as a Potential Carbapenem-Sparing Antibiotic. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temocillin Versus a Carbapenem as Initial Intravenous Treatment for ESBL Related Urinary Tract Infections (www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed 2nd march 2024).

- Marín-Candón, A.; Rosso-Fernández, C.M.; Bustos de Godoy, N.; López-Cerero, L.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, B.; López-Cortés, L.E.; Barrera Pulido, L.; Borreguero Borreguero, I.; León, M.J.; Merino, V.; et al. Temocillin versus Meropenem for the Targeted Treatment of Bacteraemia due to Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant (ASTARTÉ): Protocol for a Randomised, Pragmatic Trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonello, R.M.; Principe, L.; Maraolo, A.E.; Viaggi, V.; Pol, R.; Fabbiani, M.; Montagnani, F.; Lovecchio, A.; Luzzati, R.; Di Bella, S. Fosfomycin as Partner Drug for Systemic Infection Management. A Systematic Review of Its Synergistic Properties from In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carryn, S.; Couwenbergh, N.; Tulkens, P.M. Long-Term Stability of Temocillin in Elastomeric Pumps for Outpatient Antibiotic Therapy in Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2045–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, A.; Palermiti, A.; Mula, J.; Cusato, J.; Maiese, D.; Simiele, M.; De Nicolò, A.; D’Avolio, A. Stability Study of Fosfomycin in Elastomeric Pumps at 4 °C and 34 °C: Technical Bases for a Continuous Infusion Use for Outpatient Parenteral Antibiotic Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, R.M.; Di Bella, S.; Maraolo, A.E.; Luzzati, R. Fosfomycin in Continuous or Prolonged Infusion for Systemic Bacterial Infections: A Systematic Review of Its Dosing Regimen Proposal from in Vitro, in Vivo and Clinical Studies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumbarello, M.; Raffaelli, F.; Giannella, M.; Mantengoli, E.; Mularoni, A.; Venditti, M.; De Rosa, F.G.; Sarmati, L.; Bassetti, M.; Brindicci, G.; et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam Use for Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. Pneumoniae Infections: A Retrospective Observational Multicenter Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berleur, M.; Guérin, F.; Massias, L.; Chau, F.; Poujade, J.; Cattoir, V.; Fantin, B.; de Lastours, V. Activity of Fosfomycin Alone or Combined with Temocillin in Vitro and in a Murine Model of Peritonitis due to KPC-3- or OXA-48-Producing Escherichia Coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 3074–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suich, J.; Mawer, D.; van der Woude, M.; Wearmouth, D.; Burns, P.; Smeets, T.; Barlow, G. Evaluation of Activity of Fosfomycin, and Synergy in Combination, in Gram-Negative Bloodstream Infection Isolates in a UK Teaching Hospital. J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretto, E.; Brovarone, F.; Gaibani, P.; Russello, G.; Farina, C. Multicentric evaluation of the reliability and reproducibility of synergy testing using the MIC strip test – synergy applications system (MTS-SAS™). ECCMID 2016. Poster 0802.

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 14.0, 2024. http://www.eucast.org.

- Lagatolla, C.; Mehat, J.W.; La Ragione, R.M.; Luzzati, R.; Di Bella, S. In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Oritavancin and Fosfomycin Synergism against Vancomycin-Resistant. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, R.M.; Di Bella, S.; Betts, J.; La Ragione, R.; Bressan, R.; Principe, L.; Morabito, S.; Gigliucci, F.; Tozzoli, R.; Busetti, M.; et al. Zidovudine in Synergistic Combination with Fosfomycin: An in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation against Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiatti, T.B.; Cayô, R.; Santos, F.F.; Bessa-Neto, F.O.; Brandão Silva, R.G.; Veiga, R.; de Nazaré Miranda Bahia, M.; Guerra, L.M.G.D.; Pignatari, A.C.C.; de Oliveira Souza, C.; Brasiliense, D.M.; Gales, A.C.; Guarani Network. Genomic Analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 Strain Coproducing KPC-2 and CTX-M-14 Isolated from Poultry in the Brazilian Amazon Region. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022, 11, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonardi, S.; Cabassi, C.S.; Fiaccadori, E.; Cavirani, S.; Parisi, A.; Bacci, C.; Lamperti, L.; Rega, M.; Conter, M.; Marra, F.; Crippa, C.; Gambi, L.; Spadini, C.; Iannarelli, M.; Paladini, C.; Filippin, N.; Pasquali, F. Detection of carbapenemase- and ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from bovine bulk milk and comparison with clinical human isolates in Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 387, 110049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibani, P.; Giani, T.; Bovo, F.; Lombardo, D.; Amadesi, S.; Lazzarotto, T.; Coppi, M.; Rossolini, G.M.; Ambretti, S. Resistance to Ceftazidime/Avibactam, Meropenem/Vaborbactam and Imipenem/Relebactam in Gram-Negative MDR Bacilli: Molecular Mechanisms and Susceptibility Testing. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022, 11, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Shen, S.; Chen, J.; Tian, Z.; Shi, Q.; Han, R.; Guo, Y.; Hu, F. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase variants: the new threat to global public health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e0000823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pilato, V.; Principe, L.; Andriani, L.; Aiezza, N.; Coppi, M.; Ricci, S.; Giani, T.; Luzzaro, F.; Rossolini, G.M. Deciphering Variable Resistance to Novel Carbapenem-Based β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations in a Multi-Clonal Outbreak Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Resistant to Ceftazidime/avibactam. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 537.e1–e537.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, S.C.J.; Rybak, M.J. Meropenem and Vaborbactam: Stepping up the Battle against Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriales. Pharmacotherapy 2018, 38, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomovskaya, O.; Sun, D.; Rubio-Aparicio, D.; Nelson, K.; Tsivkovski, R.; Griffith, D.C.; Dudley, M.N. Vaborbactam: Spectrum of β-lactamase inhibition and impact of resistance mechanisms on activity in Enterobacteriales. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01443-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titov, I.; Wunderink, R.G.; Roquilly, A.; Gonzalez, D.R.; David-Wang, A.; Boucher, H.W.; Kaye, K.S.; Losada, M.C.; Du, J.; Tipping, R.; et al. A Randomized, Double-blind, Multicenter Trial Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam Versus Piperacillin/Tazobactam in Adults with Hospital-acquired or Ventilator-associated Bacterial Pneumonia (RESTOREIMI 2 Study). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, e4539–e4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, F.; Amadesi, S.; Palombo, M.; Lazzarotto, T.; Ambretti, S.; Gaibani, P. Clonal Dissemination of Resistant to Cefiderocol, Ceftazidime/avibactam, Meropenem/vaborbactam and Imipenem/relebactam Co-Producing KPC and OXA-181 Carbapenemase. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinzona, G.; Merla, C.; Corbella, M.; Iskandar, E.N.; Seminari, E.; Di Matteo, A.; Gaiarsa, S.; Petazzoni, G.; Sassera, D.; Baldanti, F.; et al. Concomitant Resistance to Cefiderocol and Ceftazidime/Avibactam in Two Carbapenemase-Producing Isolates from Two Lung Transplant Patients. Microb. Drug Resist. 2024, 30, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Curtolo, A.; Volpicelli, L.; Cogliati, D.F.; De Angelis, M.; Cairoli, S.; Dell’Utri, D.; Goffredo, B.M.; Raponi, G.; Venditti, M. Synergistic Meropenem/Vaborbactam Plus Fosfomycin Treatment of KPC Producing K. Pneumoniae Septic Thrombosis Unresponsive to Ceftazidime/Avibactam: From the Bench to the Bedside. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boattini, M.; Bianco, G.; Iannaccone, M.; Bondi, A.; Cavallo, R.; Costa, C. Looking beyond Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance in KPC-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: In Vitro Activity of the Novel Meropenem-Vaborbactam in Combination with the Old Fosfomycin. J. Chemother. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombo, M.; Bovo, F.; Amadesi, S.; Gaibani, P. Synergistic Activity of Cefiderocol in Combination with Piperacillin-Tazobactam, Fosfomycin, Ampicillin-Sulbactam, Imipenem-Relebactam and Ceftazidime-Avibactam against Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| # | MIC FOS | MIC TEM | MIC FOS/TEM | MIC TEM/FOS | FICI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 0,25 | SYNERGISM |

| 2 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 3 | 8 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,62 | ADDITIVE |

| 4 | 6 | 12 | 1,5 | 2 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 5 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 6 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 7 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 8 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 0,27 | SYNERGISM |

| 9 | 12 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 10 | 4 | 6 | 0,75 | 1,5 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 11 | 6 | 12 | 1,5 | 2 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 12 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 8 | 0,52 | ADDITIVE |

| 13 | 12 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 14 | 4 | 8 | 0,75 | 2 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 15 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 16 | 24 | 32 | 18 | 16 | 1,25 | INDIFFERENT |

| 17 | 16 | 32 | 4 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 18 | 16 | 24 | 4 | 6 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 19 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 20 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 21 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 0,25 | SYNERGISM |

| 22 | 12 | 16 | 1,5 | 3 | 0,31 | SYNERGISM |

| 23 | 4 | 6 | 0,5 | 1,5 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 24 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 1,5 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 25 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 26 | 32 | 48 | 6 | 12 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 27 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 28 | 8 | 16 | 1,5 | 4 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 29 | 12 | 24 | 2 | 6 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 30 | 24 | 32 | 6 | 8 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 31 | 16 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 32 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 33 | 4 | 6 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,29 | SYNERGISM |

| 34 | 6 | 8 | 0,75 | 2 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 35 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 36 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 37 | 24 | 48 | 6 | 12 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 38 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 6 | 0,62 | ADDITIVE |

| 39 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 0,27 | SYNERGISM |

| 40 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1,5 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 41 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 42 | 8 | 16 | 0,75 | 3 | 0,28 | SYNERGISM |

| 43 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 0,20 | SYNERGISM |

| 44 | 8 | 12 | 0,75 | 3 | 0,34 | SYNERGISM |

| 45 | 4 | 8 | 0,38 | 1 | 0,22 | SYNERGISM |

| 46 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 47 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 48 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 6 | 0,62 | ADDITIVE |

| 49 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 1,5 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 50 | 4 | 6 | 0,5 | 2 | 0,45 | SYNERGISM |

| 51 | 24 | 32 | 6 | 12 | 0,62 | ADDITIVE |

| 52 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 53 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 54 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 55 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 56 | 6 | 8 | 0,75 | 2 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 57 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 58 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 0,25 | SYNERGISM |

| 59 | 4 | 6 | 0,75 | 1,5 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 60 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 61 | 12 | 16 | 1,5 | 4 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 62 | 32 | 48 | 6 | 12 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 63 | 24 | 48 | 12 | 24 | 1 | ADDITIVE |

| 64 | 16 | 24 | 6 | 12 | 0,87 | ADDITIVE |

| 65 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 66 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 67 | 4 | 8 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,25 | SYNERGISM |

| 68 | 8 | 16 | 0,75 | 2 | 0,21 | SYNERGISM |

| 69 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 70 | 6 | 12 | 1,5 | 2 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 71 | 8 | 16 | 1,5 | 2 | 0,31 | SYNERGISM |

| 72 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 0,29 | SYNERGISM |

| 73 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 74 | 12 | 16 | 1,5 | 2 | 0,25 | SYNERGISM |

| 75 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 0,31 | SYNERGISM |

| 76 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 3 | 0,27 | SYNERGISM |

| 77 | 32 | 48 | 8 | 12 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 78 | 16 | 24 | 4 | 6 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 79 | 12 | 24 | 2 | 4 | 0,33 | SYNERGISM |

| 80 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 81 | 12 | 16 | 1,5 | 4 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 82 | 16 | 24 | 2 | 6 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 83 | 12 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 0,33 | SYNERGISM |

| 84 | 16 | 24 | 2 | 6 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 85 | 8 | 12 | 0,75 | 2 | 0,26 | SYNERGISM |

| 86 | 12 | 24 | 1,5 | 4 | 0,29 | SYNERGISM |

| 87 | 16 | 48 | 3 | 8 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

| 88 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 89 | 24 | 32 | 8 | 12 | 0,70 | ADDITIVE |

| 90 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 91 | 12 | 24 | 2 | 6 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 92 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 93 | 8 | 12 | 0,75 | 2 | 0,26 | SYNERGISM |

| 94 | 12 | 16 | 1,5 | 4 | 0,37 | SYNERGISM |

| 95 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 0,5 | SYNERGISM |

| 96 | 8 | 12 | 1,5 | 3 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 97 | 4 | 12 | 0,5 | 1,5 | 0,25 | SYNERGISM |

| 98 | 16 | 32 | 4 | 6 | 0,43 | SYNERGISM |

| 99 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 0,41 | SYNERGISM |

| 100 | 16 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 0,35 | SYNERGISM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).