Submitted:

26 February 2024

Posted:

06 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

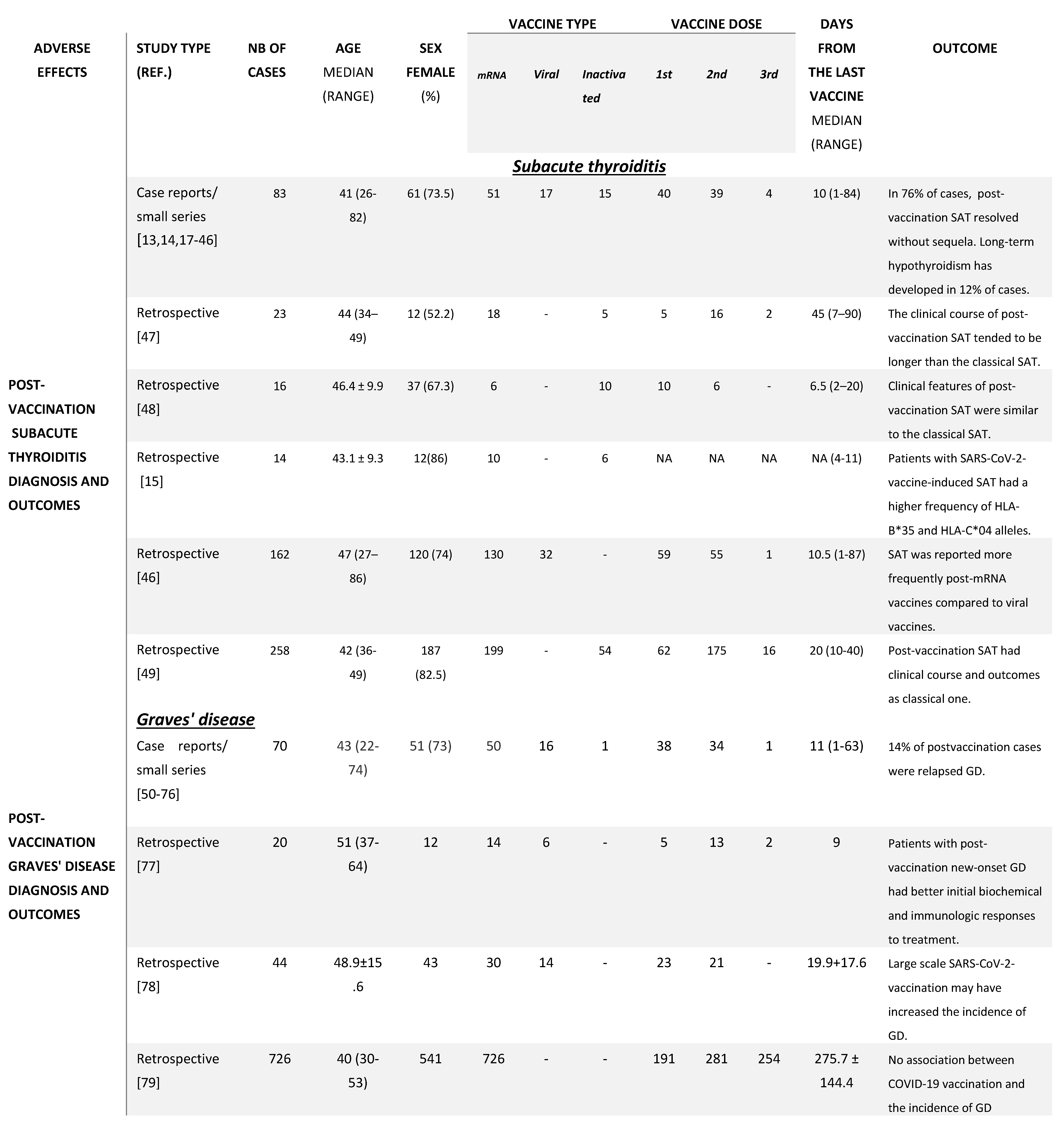

3. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Thyroid Dysfunction

4. Pituitary Gland and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine

5. Adrenal Glands and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine

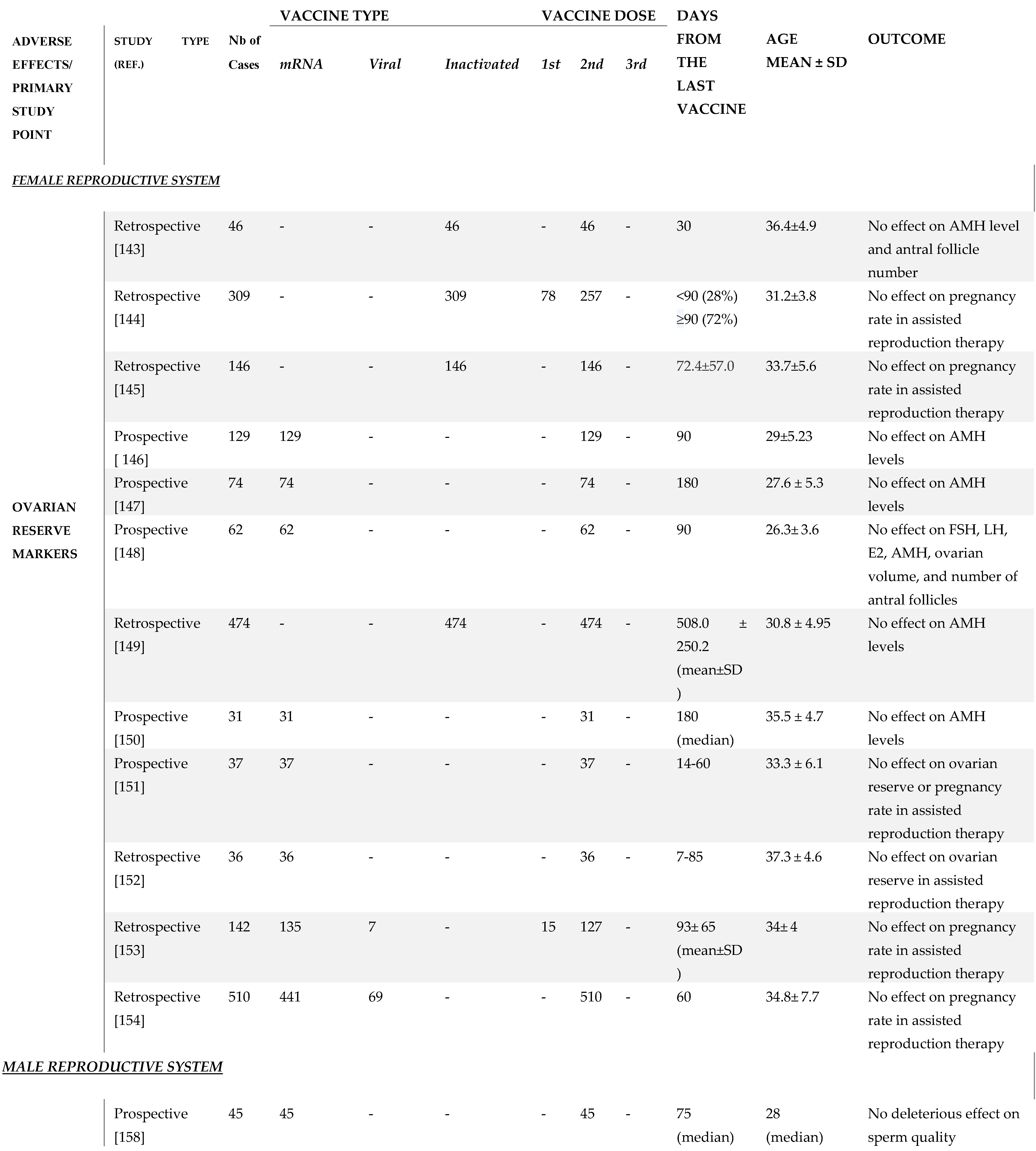

6. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Female Reproductive System

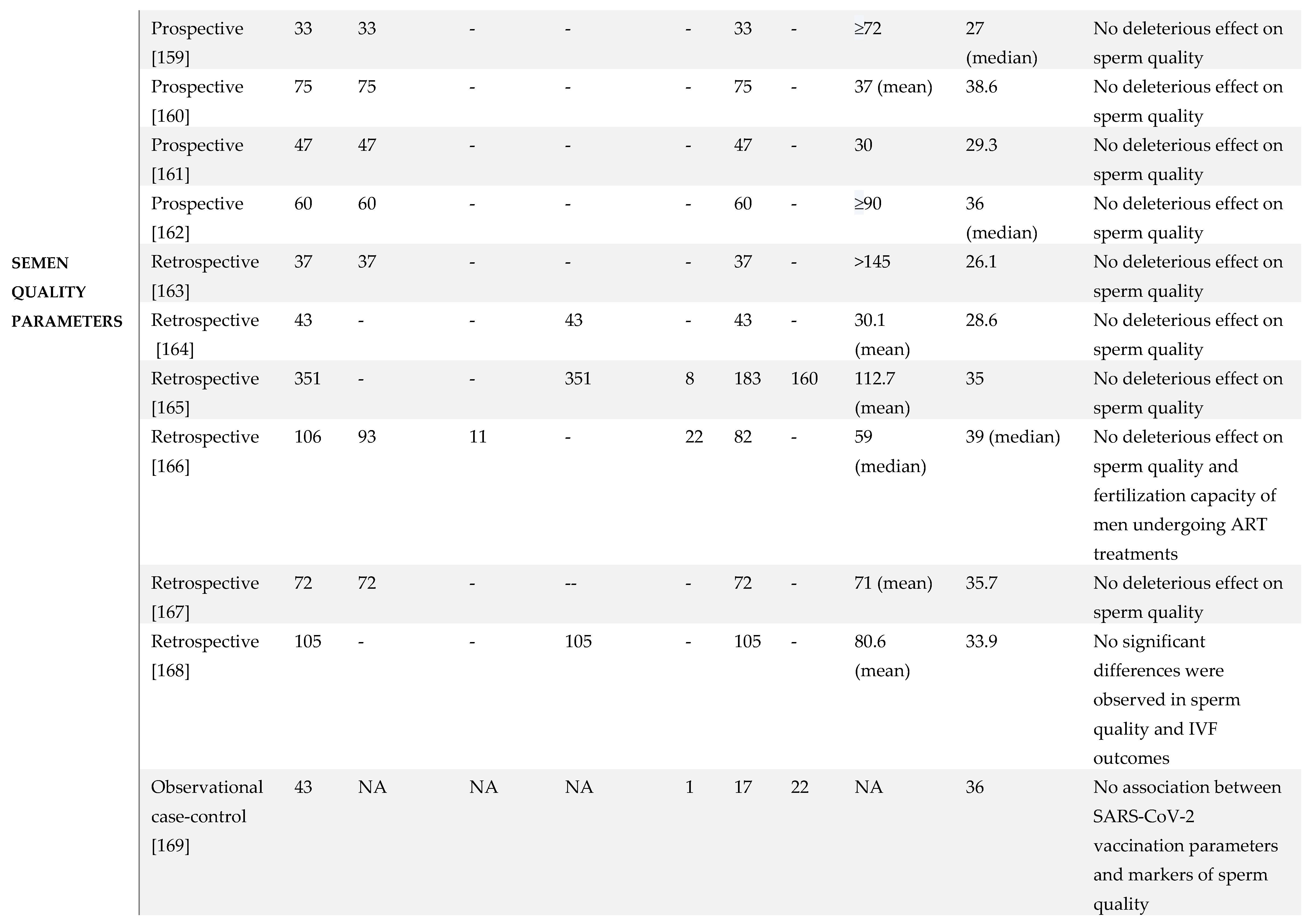

7. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Male Reproductive System

8. Diabetes Mellitus and COVID-19 Vaccine

8.1. Diabetes Mellitus and mRNA Vaccination

8.2. GAD Positivity in Type 1 Diabetes.

8.3. Could COVID-19 Vaccine Elicit GAD Antibody Formation?

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at: http://covid19.who.int.

- Kudlay D, Svistunov A. COVID-19 Vaccines: An Overview of Different Platforms. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9(2):72. Published 2022 February 12. [CrossRef]

- Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1017-1032. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Wu X. Influence of COVID-19 vaccines on endocrine system. Endocrine. 2022;78(2):241-246. [CrossRef]

- Ishay A, Shacham EC. Central diabetes insipidus: a late sequela of BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine?. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023;23(1):47. Published 2023 February 22. [CrossRef]

- Asghar N, Mumtaz H, Syed AA, et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines; a systematic review. Immunol Med. 2022;45(4):225-237. [CrossRef]

- Dhamanti I, Suwantika AA, Adlia A, Yamani LN, Yakub F. Adverse Reactions of COVID-19 Vaccines: A Scoping Review of Observational Studies. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:609-618. Published 2023 February 20. [CrossRef]

- Olivieri B, Betterle C, Zanoni G. Vaccinations and autoimmune diseases. Vaccines. 2021 Jul 22;9(8):815.

- Jena A, Mishra S, Deepak P, Kumar-M P, Sharma A, Patel YI, Kennedy NA, Kim AH, Sharma V, Sebastian S. Response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in immune mediated inflammatory diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmunity reviews. 2022 Jan 1;21(1):102927.

- Pezzaioli LC, Gatta E, Bambini F, et al. Endocrine system after 2 years of COVID-19 vaccines: A narrative review of the literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1027047. Published 2022 Nov 10. [CrossRef]

- Vojdani A, Vojdani E, Kharrazian D. Reaction of human monoclonal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 proteins with tissue antigens: implications for autoimmune diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021 Jan 19;11:3679.

- Iremli BG, Sendur SN, -Onliitlirk U. Three Cases of Subacute Thyroiditis Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: Postvaccination ASIA Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(9):2600-5.

- Jafarzadeh A, Nemati M, Jafarzadeh S, Nozari P, Mortazavi SMJ. Thyroid dysfunction following vaccination with COVID-19 vaccines: a basic review of the preliminary evidence. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022 Oct;45(10):1835-1863. Epub 2022 Mar 26. [CrossRef]

- Stasiak M, Lewiński A. New aspects in the pathogenesis and management of subacute thyroiditis. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 2021 Dec;22(4):1027-39.

- Şendur SN, Özmen F, Oğuz SH, İremli BG, Malkan Ü., Gürlek A, et al. Association of human leukocyte antigen genotypes with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis. Thyroid (2022) 32 (6):640–7. [CrossRef]

- Ie K, Ishizuka K, Sakai T, Motohashi I, Asai S, Okuse C. Subacute thyroiditis developing within 2 days of vaccination against COVID-19 with BNT162b2 mRNA. European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine. 2023;10(1).

- Tomic AZ, Zafirovic SS, Gluvic ZM, et al. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination: Case presentation. Antiviral Therapy. 2023;28(5).

- Franquemont S, Galvez J. Subacute Thyroiditis After mRNA vaccine for Covid-19. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:A956-A7.

- Pujol A, Gomez LA, Gallegos C, Nicolau J, Sanchis P, Gonzalez-Freire M, et al. Thyroid as a target of adjuvant autoimmunity/inflammatory syndrome due to mRNA-based SARS-CoV2 vaccination: from Graves' disease to silent thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(4):875-82.

- Saygili ES, Karakilic E. Subacute thyroiditis after inactive SARS-Co V-2 vaccine. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(10). 2021.

- Sahin Tekin M, Sayhsoy S, Yorulmaz G. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination in a 67-year-old male patient: a case report. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(11):4090-2.

- Bornemann C, Woyk K, Bouter C. Case Report: Two Cases of Subacute Thyroiditis Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:737142.

- Plaza-Enriquez L, Khatiwada P, Sanchez-Valenzuela M, Sikha A. A Case Report of Subacute Thyroiditis following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2021;2021:8952048.

- Siolos A, Gartzonika K, Tigas S. Thyroiditis following vaccination against COVID-19: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Metabol Open. 2021;12:100136.

- Schimmel J, Alba EL, Chen A, Russell M, Srinath R. Thyroiditis and Thyrotoxicosis After the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine. Thyroid. 2021;31(9):1440.

- Oyibo, SO. Subacute Thyroiditis After Receiving the Adenovirus-Vectored Vaccine for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Cureus. 2021;13(6):e16045.

- Ratnayake GM, Dworakowska D, Grossman AB. Can COVID-19 immunization cause subacute thyroiditis? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2021.

- Chatzi S, Karampela A, Spiliopoulou C, Boutzios G. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a report of two sisters and summary of the literature. Hormones (Athens). 2022;21(1):177-9.

- Jeeyavudeen MS, Patrick AW, Gibb FW, Dover AR. COVID-19 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis: an unusual suspect for de Quervain's thyroiditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(11).

- Kyriacou A, Ioakim S, Syed AA. COVID-19 vaccination and a severe pain in the neck. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;94:95-6.

- Soltanpoor P, Norouzi G. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(10):e04812.

- Lee KA, Kim YJ, Jin HY. Thyrotoxicosis after COVID-19 vaccination: seven case reports and a literature review. Endocrine. 2021;74(3):470-2.

- Khan F, Brassill MJ. Subacute thyroiditis post-Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccination for COVID-19. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2021;2021.

- Leber HM, Sant'Ana L, Konichi da Silva NR, Raio MC, Mazzeo TJMM, Endo CM, et al. Acute Thyroiditis and Bilateral Optic Neuritis following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination with CoronaVac: A Case Report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(6):1200-6.

- Sozen M, Topaloglu 0, etinarslan B, Selek A, Cantlirk Z, Gezer E, et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine may trigger subacute thyroiditis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):5120-5.

- Pandya M, Thota G, Wang X, Luo H. Thyroiditis after Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) mRNA Vaccine: A Case Series. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2021.

- Sigstad E, Grnholt KK, Westerheim 0. Subacute thyroiditis after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2021;141(2021-14).

- Gonzalez Lopez J, Martin Nifio I, Arana Molina C. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: report of two clinical cases. Med Clin (Bare). 2021.

- Rebollar, A.F. [SUBACUTE THYROIDITIS AFTER ANTI SARS-COV-2 (Ad5-nCoV) VACCINE]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ippolito S, Gallo D, Rossini A, Patera B, Lanzo N, Fazzino GFM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis: insights from a systematic review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022.

- Yorulmaz G, Sahin Tekin M. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022.

- Patel KR, Cunnane ME, Deschler DG. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43(1):103211.

- Pla Peris B, Merchante Alfaro A, Maravall Royo FJ, Abellan Galiana P, Perez Naranjo S, Gonzalez Boillos M. Thyrotoxicosis following SARS-COV-2 vaccination: a case series and discussion. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(5): 1071-7.

- Bostan H, Unsal IO, Kizilgul M, Gul U, Sencar ME, Ucan B, et al. Two cases of subacute thyroiditis after different types of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2022;66(1):97-103.

- Jhon M, Lee SH, Oh TH, Kang HC. Subacute Thyroiditis After Receiving the mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine (Modema): The First Case Report and Literature Review in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(6):e39.

- Garcı́a M, Albizua-Madariaga I, Lertxundi U, Aguirre C. Subacute thyroiditis and COVID-19 vaccines: a case/non-case study. Endocrine (2022) 77:480–5.

- Topaloğlu, Ö. , Tekin S, Topaloğlu SN, Bayraktaroglu T. Differences in clinical aspects between subacute thyroiditis associated with COVID-19 vaccines and classical subacute thyroiditis. Horm Metab Res (2022) 54(6):380–8.

- Bostan H, Kayihan S, Calapkulu M, Hepsen S, Gul U, Ozturk Unsal I, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic features and clinical course of COVID-19 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis. Hormones (Athens) (2022) 21:447–55.

- Batman A, Yazıcı D, Dikbaş O, Ağbaht K, Saygılı ES, Demirci I, Bursa N, Ayas G, Anıl C, Cesur M, Korkmaz FN. Subacute THYROiditis Related to SARS-CoV-2 VAccine and Covid-19 (THYROVAC Study): A Multicenter Nationwide Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2023 Apr 25:dgad235.

- Zettinig G, Krebs M. Two further cases of Graves' disease following SARS-Cov-2 vaccination. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(1):227-8.

- Vera-Lastra 0, Ordinola Navarro A, Cruz Domiguez MP, Medina G, Sanchez Valadez TI, Jara LJ. Two Cases of Graves' Disease Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: An Autoimmune/Inflammatory Syndrome Induced by Adjuvants. Thyroid. 2021;31(9):1436-9.

- Lui DTW, Lee KK, Lee CH, Lee ACH, Hung IFN, Tan KCB. Development of Graves' Disease After SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:778964.

- Weintraub MA, Ameer B, Sinha Gregory N. Graves Disease Following the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: Case Series. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:23247096211063356.

- Sriphrapradang C, Shantavasinkul PC. Graves' disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Endocrine. 2021;74(3):473-4.

- Pierman G, Delgrange E, Jonas C. Recurrence of Graves' Disease (a Thl-type Cytokine Disease) Following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Administration: A Simple Coincidence? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8(9):002807.

- , Ferrari SM, Antonelli A, Fallahi P. A case of Graves' disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Autoimmun. 2021;125:102738.

- Goblirsch TJ, Paulson AE, Tashko G, Mekonnen AJ. Graves' disease following administration of second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(12).

- Sriphrapradang, C. Aggravation of hyperthyroidism after heterologous prime-boost immunization with inactivated and adenovirus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in a patient with Graves' disease. Endocrine. 2021;74(2):226-7.

- Rubinstein TJ. Thyroid Eye Disease Following COVlD-19 Vaccine in a Patient With a History Graves' Disease: A Case Report. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37(6):e221-e3.

- di Filippo L, Castellino L, Giustina A. Occurrence and response to treatment of Graves' disease after COVID vaccination in two male patients. Endocrine. 2022;75(1):19-21.

- Taieb A, Sawsen N, Asma BA, Ghada S, Hamza E, Yosra H, et al. A rare case of grave's disease after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: is it an adjuvant effect? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(7):2627-30.

- Chee YJ, Liew H, Hoi WH, Lee Y, Lim B, Chin HX, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination and Graves' Disease: a report of 12 cases and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022.

- Patrizio A, Ferrari SM, Antonelli A, Fallahi P. Worsening of Graves' ophthalmopathy after SARS- CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Autoimmun Rev. 2022:103096.

- Park KS, Fung SE, Ting M, Ozzello DJ, Yoon JS, Liu CY, et al. Thyroid eye disease reactivation associated with COVID-19 vaccination. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2022;12(1):93-6.

- Hamouche W, El Soufi Y, Alzaraq S, Okafor BV, Zhang F, Paras C. A case report of new onset graves' disease induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccine? J Clin Transl Endocrinol Case Rep. 2022;23:100104.

- Bostan H, Ucan B, Kizilgul M, Calapkulu M, Hepsen S, Gul U, et al. Relapsed and newly diagnosed Graves' disease due to immunization against COVID-19: A case series and review of the literature. J Autoimmun. 2022;128:102809.

- Singh G, Howland T. Graves' Disease Following COVID-19 Vaccination. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e24418.

- Chua MWJ. Graves' disease after COVID-19 vaccination. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51(2): 127-8.

- Manta R, Martin C, Muls V, Poppe KG. New-onset Graves' disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a case report. Eur Thyroid J. 2022;11(4).

- Sakai M, Takao K, Kato T, Ito K, Kubota S, Hirose T, et al. Graves' Disease after Administration of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine in a Type 1 Diabetes Patient. Intern Med. 2022;61(10): 1561-5.

- Cuenca D, Aguilar-Soto M, Mercado M. A Case of Graves' Disease Following Vaccination with the Oxford-AstraZeneca SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2022;9(4):003275.

- Ruggeri RM, Giovanellla L, Campenni A. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may trigger thyroid autoimmunity: real-life experience and review of the literature. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022.

- Takedani K, Notsu M, Ishiai N, Asami Y, Uchida K, Kanasaki K. Graves' disease after exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2023 Jun 15;23(1):132.

- Nakamura F, Awaya T, Ohira M, Enomoto Y, Moroi M, Nakamura M. Graves' Disease after mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination, with the Presence of Autoimmune Antibodies Even One Year Later. Vaccines. 2023 May 3;11(5):934.

- Yan BC, Luo RR. Thyrotoxicosis in patients with a history of Graves' disease after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (adenovirus vector vaccine): Two case reports. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2023 Feb 2;11(5):1122.

- Yasuda, S., Suzuki, S., Yanagisawa, S. et al. HLA typing of patients who developed subacute thyroiditis and Graves' disease after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a case report. BMC Endocr Disord 23, 54 (2023).

- di Filippo L, Castellino L, Allora A, Frara S, Lanzi R, Perticone F, Valsecchi F, Vassallo A, Giubbini R, Rosen CJ, Giustina A. Distinct Clinical Features of Post-COVID-19 Vaccination Early-onset Graves’ Disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2023 Jan 1;108(1):107-13.

- Barajas Galindo DE, Ramos Bachiller B, González Roza L, García Ruiz de Morales JM, Sánchez Lasheras F, González Arnáiz E, Ariadel Cobo D, Ballesteros Pomar MD, Rodríguez IC. Increased incidence of Graves' disease during the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. Clinical Endocrinology. 2023 May;98(5):730-7.

- Gorshtein A, Turjeman A, Duskin-Bitan H, Leibovici L, Robenshtok E. Graves' disease following COVID-19 vaccination: a population-based, matched case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023 Oct 10:dgad582. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37815523. [CrossRef]

- Wong CH, Leung EKH, Tang LCK, et al. Effect of inactivated and mRNA COVID-19 vaccination on thyroid function among patients treated for hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023, 108(5): e76-e88.

- Peng K, Li X, Yang D, Chan SC, Zhou J, Wan EY, Chui CS, Lai FT, Wong CK, Chan EW, Leung WK. Risk of autoimmune diseases following COVID-19 and the potential protective effect from vaccination: a population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023 Sep 1;63.

- Wong CK, Lui DT, Xiong X, Chui CS, Lai FT, Li X, Wan EY, Cheung CL, Lee CH, Woo YC, Au IC. Risk of thyroid dysfunction associated with mRNA and inactivated COVID-19 vaccines: a population-based study of 2.3 million vaccine recipients. BMC medicine. 2022 Oct 14;20(1):339.

- Abeillon-du Payrat J, Grunenwald S, Gall E, Ladsous M, Raingeard I, Caron P. Graves' orbitopathy post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: report on six patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46(3):617-627. [CrossRef]

- Im Teoh JH, Mustafa N, Wahab N. New-onset Thyroid Eye Disease after COVID-19 Vaccination in a Radioactive Iodine-Treated Graves' Disease Patient: A Case Report and Literature Review. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2023;38(1):125-130. Epub 2023 Feb 8. PMID: 37252417; PMCID: PMC10213383. [CrossRef]

- Aliberti L, Gagliardi I, Rizzo R, et al. Pituitary apoplexy and COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and literature review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1035482. Published 2022 Nov 17. [CrossRef]

- Roncati L, Manenti A. Pituitary apoplexy following adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccination. Brain Hemorrhages. 2023;4(1):27-29. [CrossRef]

- Zainordin NA, Hatta SFWM, Ab Mumin N, Shah FZM, Ghani RA. Pituitary apoplexy after COVID-19 vaccination: A case report. J Clin Transl Endocrinol Case Rep. 2022;25:100123. [CrossRef]

- Jaggi S, Jabbour S. Abstract #1001394: A Rare Endocrine Complication of the COVID-19 Vaccine, Endocrine Practice 2021; 27(6): S116-7.

- Ishay A, Shacham EC. Central diabetes insipidus: a late sequela of BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine?. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023;23(1):47. Published 2023 Feb 22. [CrossRef]

- Piñar-Gutiérrez A, Remón-Ruiz P, Soto-Moreno A. Case report: Pituitary apoplexy after COVID-19 vaccination. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2022;158(10):498-499. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A., Karavitaki, N. and Wass, J.A.H. (2010), Prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a community-based, cross-sectional study in Banbury (Oxfordshire, UK). Clinical Endocrinology, 72: 377-382. [CrossRef]

- Briet C, Salenave S, Bonneville JF, Laws ER, Chanson P. Pituitary Apoplexy. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(6):622-645. [CrossRef]

- Bujawansa, S., Thondam, S.K., Steele, C., Cuthbertson, D.J., Gilkes, C.E., Noonan, C., Bleaney, C.W., MacFarlane, I.A., Javadpour, M. and Daousi, C. (2014), Presentation, management and outcomes in acute pituitary apoplexy: a large single-centre experience from the United Kingdom. Clin Endocrinol, 80: 419-424. [CrossRef]

- Taieb A, Mounira EE. Pilot Findings on SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-Induced Pituitary Diseases: A Mini Review from Diagnosis to Pathophysiology. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(12):2004. Published 2022 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Taieb A, Asma BA, Mounira EE. Evidences that SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-Induced apoplexy may not be solely due to ASIA or VITT syndrome', Commentary on Pituitary apoplexy and COVID-19 vaccination: A case report and literature review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Jan 25;14:1111581. PMID: 36761192; PMCID: PMC9907727. [CrossRef]

- Prete A, Salvatori R. Hypophysitis. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; October 15, 2021.

- Bouça B, Roldão M, Bogalho P, Cerqueira L, Silva-Nunes J. Central Diabetes Insipidus Following Immunization With BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine: A Case Report. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:889074. Published 2022 May 4. [CrossRef]

- Ach T, Kammoun F, Fekih HE, et al. Central diabetes insipidus revealing a hypophysitis induced by SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Therapie. 2023;78(4):453-455. [CrossRef]

- Partenope C, Pedranzini Q, Petri A, Rabbone I, Prodam F, Bellone S. AVP deficiency (central diabetes insipidus) following immunization with anti-COVID-19 BNT162b2 Comirnaty vaccine in adolescents: A case report. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1166953. Published 2023 Apr 18. [CrossRef]

- Matsuo T, Okubo K, Mifune H, Imao T. Bilateral Optic Neuritis and Hypophysitis With Diabetes Insipidus 1 Month After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine: Case Report and Literature Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2023;11:23247096231186046. [CrossRef]

- Murvelashvili N, Tessnow A. A Case of Hypophysitis Following Immunization With the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9:23247096211043386. [CrossRef]

- Ankireddypalli AR, Chow LS, Radulescu A, Kawakami Y, Araki T. A Case of Hypophysitis Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;8(5):204-209. [CrossRef]

- Morita S, Tsuji T, Kishimoto S, et al. Isolated ACTH deficiency following immunization with the BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a case report. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22(1):185. Published 2022 Jul 19. [CrossRef]

- Lindner G, Ryser B. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis after vaccination against COVID-19: case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1000. Published 2021 Sep 25. [CrossRef]

- Jara LJ, Vera-Lastra O, Mahroum N, Pineda C, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune post-COVID vaccine syndromes: does the spectrum of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome expand?. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(5):1603-1609. [CrossRef]

- Liang Z, Zhu H, Wang X, et al. Adjuvants for Coronavirus Vaccines. Front Immunol. 2020;11:589833. Published 2020 Nov 6. [CrossRef]

- Cosentino M, Marino F. The spike hypothesis in vaccine-induced adverse effects: questions and answers. Trends Mol Med. 2022 Oct;28(10):797-799. Epub 2022 Sep 12. PMID: 36114089; PMCID: PMC9494717. [CrossRef]

- Boschi C, Scheim DE, Bancod A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Induces Hemagglutination: Implications for COVID-19 Morbidities and Therapeutics and for Vaccine Adverse Effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):15480. Published 2022 Dec 7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, Guruparan T, Siddiqi S, et al. A case of adrenal infarction in a patient with COVID 19 infection. BJR Case Rep. 2020;6(3):20200075. Published 2020 Jun 4. [CrossRef]

- Leyendecker P, Ritter S, Riou M, et al. Acute adrenal infarction as an incidental CT finding and a potential prognosis factor in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective cohort analysis on 219 patients. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(2):895-900. [CrossRef]

- Frankel M, Feldman I, Levine M, et al. Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patient: A Case Report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(12):dgaa487. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Troncoso J, Zapatero Larrauri M, Montero Vega MD, et al. Case Report: COVID-19 with Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1156-1157. [CrossRef]

- Arlt W; Society for Endocrinology Clinical Committee. SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY ENDOCRINE EMERGENCY GUIDANCE: Emergency management of acute adrenal insufficiency (adrenal crisis) in adult patients. Endocr Connect. 2016;5(5):G1-G3. [CrossRef]

- Dineen R, Thompson CJ, Sherlock M. Adrenal crisis: prevention and management in adult patients. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2019;10:2042018819848218. Published 2019 Jun 13. [CrossRef]

- Maguire D, McLaren DS, Rasool I, Shah PM, Lynch J, Murray RD. ChAdOx1 SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A putative precipitant of adrenal crises. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2023;99(5):470-473. [CrossRef]

- ADSHG. Coronavirus vaccines and adrenal insufficiency. Bristol: Addison's Disease Self-Help Group. 2021. https://www.addisonsdisease.org.uk/coronavirus-vaccines.

- Katznelson L, Gadelha M. Glucocorticoid use in patients with adrenal insufficiency following administration of the COVID-19 vaccine: a pituitary society statement. Pituitary. 2021;24(2):143-145. [CrossRef]

- Pilli T, Dalmiglio C, Dalmazio G, et al. No need of glucocorticoid dose adjustment in patients with adrenal insufficiency before COVID-19 vaccine. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(1):K7-K11. Published 2022 Jun 1. [CrossRef]

- Haji N Jr, Ali S, Wahashi EA, Khalid M, Ramamurthi K. Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 Vaccination Triggering Pheochromocytoma Multisystem Crisis. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18196. Published 2021 Sep 22. [CrossRef]

- Markovic N, Faizan A, Boradia C, Nambi S. Adrenal Crisis Secondary to COVID-19 Vaccination in a Patient With Hypopituitarism. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;8(4):171-173. [CrossRef]

- Taylor P, Allen L, Shrikrishnapalasuriyar N, Stechman M, Rees A. Vaccine-induced thrombosis and thrombocytopenia with bilateral adrenal haemorrhage. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2022;97(1):26-27.

- Varona JF, García-Isidro M, Moeinvaziri M, Ramos-López M, Fernández- Domínguez M. Primary adrenal insufficiency associated with Oxford-AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT). Eur J Intern Med. 2021;91:90-92.

- Tews HC, Driendl SM, Kandulski M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia with venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and adrenal haemorrhage: a case report with literature review. Vaccines. 2022;10(4):595.

- Blauenfeldt RA, Kristensen SR, Ernstsen SL, Kristensen CCH, Simonsen CZ, Hvas AM. Thrombocytopenia with acute ischemic stroke and bleeding in a patient newly vaccinated with an adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccine. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 Jul;19(7):1771-1775. Epub 2021 May 5. PMID: 33877737; PMCID: PMC8250306. [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino V, Caranci F, Negro A, et al. A Rare Case of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Temporally Associated to the COVID-19 Vaccine Administration. J Pers Med. 2021;11(4):285. Published 2021 Apr 8. [CrossRef]

- Al Rawahi B, BaTaher H, Jaffer Z, Al-Balushi A, Al-Mazrouqi A, Al-Balushi N. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia following AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCOV19) vaccine-A case report. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(6):e12578. Published 2021 Aug 24. [CrossRef]

- Graf A, Armeni E, Dickinson L, et al. Adrenal haemorrhage and infarction in the setting of vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis after SARS-CoV-2 (Oxford–AstraZeneca) vaccination. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2022;2022:21-0144.

- Efthymiadis A, Khan D, Pavord S, Pal A. A case of ChAdOx1 vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis syndrome leading to bilateral adrenal haemorrhage and adrenal insufficiency. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. Published online June 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tha T, Martini I, Stefan E, Redla S. Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage with renal infarction after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 AstraZeneca vaccination. BJR Case Rep. 2022;8(2):20210139. Published 2022 Jan 10. [CrossRef]

- Douxfils J, Vayne C, Pouplard C, et al. Fatal exacerbation of ChadOx1-nCoV-19-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia syndrome after initial successful therapy with intravenous immunoglobulins - a rational for monitoring immunoglobulin G levels. Haematologica. 2021;106(12):3249-3252. Published 2021 Dec 1. [CrossRef]

- Boyle LD, Morganstein DL, Mitra I, Nogueira EF A rare case of multiple thrombi and left adrenal haemorrhage following COVID-19 vaccination. Endocr Abstr. 2021;74(NCC4).

- Ahmad S, Zaman N, Almajali K, Muhammadi A, Baburaj R, Akavarapu S. A novel case of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage and acute adrenal insufficiency due to VITT (vaccine induced thrombosis and thrombocytopenia) syndrome. Endocr Abstr. 2021;74(OC2).

- Elhassan YS, Iqbal F, Arlt W, et al. COVID-19-related adrenal hemorrhage: Multicentre UK experience and systematic review of the literature. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2023;98(6):766-778. [CrossRef]

- Elalamy I, Gerotziafas G, Alamowitch S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine and Thrombosis: An Expert Consensus on Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(8):982-991. [CrossRef]

- Marchandot B, Curtiaud A, Trimaille A, Sattler L, Grunebaum L, Morel O. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia: current evidence, potential mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions. Eur Heart J Open. 2021;1(2):oeab014. Published 2021 Aug 2. [CrossRef]

- Harville, EW. Invited Commentary: Vaccines and Fertility—Why Worry? American Journal of Epidemiology. 2023 Feb;192(2):154-7.

- Mobaraki A, Stetter C, Kunselman AR, Estes SJ. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Women Who Desire Future Fertility/Pregnancy. J Gynecol Clin Obstet Reprod Med. 2023;1(2):48-65.

- Morris RS. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein seropositivity from vaccination or infection does not cause sterility. F S Rep. 2021 Sep;2(3):253-255. Epub 2021 Jun 2. PMID: 34095871; PMCID: PMC8169568. [CrossRef]

- Coulam CB, Roussev RG. Increasing circulating T-cell activation markers are linked to subsequent implantation failure after transfer of in vitro fertilized embryos. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2003 Oct;50(4):340-5.

- Moolhuijsen LM, Visser JA. Anti-Müllerian hormone and ovarian reserve: update on assessing ovarian function. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020 Nov;105(11):3361-73.

- Dellino M, Lamanna B, Vinciguerra M, Tafuri S, Stefanizzi P, Malvasi A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and adverse effects in gynecology and obstetrics: the first italian retrospective study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022:19.

- Kolatorova L, Adamcova K, Vitku J, Horackova L, Simkova M, Hornova M, et al.COVID-19, vaccination, and female fertility in the Czech Republic. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:10909.

- Senkaya AR, Çil Z, Keskin ¨O, Günes¸ ME, ¨Oztekin DC. CoronaVac vaccine does not affect ovarian reserve. Ginekol Pol 2023;94:298–302.

- Xu Z, Wu Y, Lin Y, Cao M, Liang Z, Li L, et al. Effect of inactivated COVID-19 vaccination on intrauterine insemination cycle success: a retrospective cohort study. Frontiers. Public Health 2022:10.

- Huang J, Xia L, Lin J, Liu B, Zhao Y, Xin C, et al. No effect of inactivated SARS-CoV- 2 vaccination on in vitro fertilization outcomes: a propensity score-matched study. J Inflamm Res 2022:839–49.

- Mohr-Sasson A, Haas J, Abuhasira S, Sivan M, Doitch Amdurski H, Dadon T, et al. The effect of Covid-19 mRNA vaccine on serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Hum Reprod 2022;37:534–41.

- Yildiz E, Timur B, Guney G, Timur H. Does the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine damage the ovarian reserve? Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 May 19;102(20):e33824.

- Kumbasar S, Salman S, Çakmak GN, Gencer FK, Sicakyüz LS, Kumbasar AN. Effect of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine on ovarian reserve of women of reproductive age. Ginekologia Polska. 2023 Oct 18.

- Huang J, Guan T, Tian L, Xia L, Xu D, Wu X, Huang L, Chen M, Fang Z, Xiong C, Nie L. Impact of inactivated COVID-19 vaccination on female ovarian reserve: a propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14.

- Horowitz E, Mizrachi Y, Herman HG, Marcuschamer EO, Shalev A, Farhi J, et al. The effect of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination on AMH concentrations in infertile women. Reprod Biomed Online 2022;45:779–84.

- Odeh-Natour R, Shapira M, Estrada D, Freimann S, Tal Y, Atzmon Y, et al. Does mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the follicular fluid impact follicle and oocyte performance in IVF treatments? Am J Reprod Immunol 2022;87:e13530.

- Orvieto R, Noach-Hirsh M, Segev-Zahav A, Haas J, Nahum R, Aizer A. Does mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine influence patients' performance during IVF-ET cycle? Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2021;19:69.

- Jacobs E, Summers K, Sparks A, Mejia R. Fresh embryo transfer cycle characteristics and outcomes following in vitro fertilization via intracytoplasmic sperm injection among patients with and without COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e228625 -e.

- Requena A, Vergara V, Gonz´alez-Ravina C, Ruiz ME, Cruz M. The type of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine does not affect ovarian function in assisted reproduction cycle. Fertil Steril 2023;119:618–23.

- Yland JJ, Wesselink AK, Regan AK, Hatch EE, Rothman KJ, Savitz DA, Wang TR, Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Eisenberg ML, Wise LA. A prospective cohort study of preconception COVID-19 vaccination and miscarriage. Human Reproduction. 2023 Oct 20:dead211.

- Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Buck Louis GM, Toppari J, Andersson AM, Eisenberg ML, Jensen TK, Jørgensen N, Swan SH, Sapra KJ, Ziebe S. Male reproductive disorders and fertility trends: influences of environment and genetic susceptibility. Physiological reviews. 2016 Jan;96(1):55-97.

- Lewis SE. Is sperm evaluation useful in predicting human fertility? Reproduction. 2007;134:31–40.

- Gonzalez DC, Nassau DE, Khodamoradi K, Ibrahim E, Blachman-Braun R, Ory J, et al. Sperm parameters before and after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA (2021) 326(3):273–4. [CrossRef]

- Barda S, Laskov I, Grisaru D, Lehavi O, Kleiman S, Wenkert A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 vaccine on sperm quality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2022) 158:116–20. [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz D, Haas J, Lebovitz O, Raviv G, Orvieto R, Aizer A. Does mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine detrimentally affect male fertility, as reflected by semen analysis? Reprod BioMed Online (2022) 44(1):145–9. [CrossRef]

- Olana S, Mazzilli R, Salerno G, Zamponi V, Tarsitano MG, Simmaco M, et al. 4BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and semen: What do we know? Andrology (2022) 10:1023–9. [CrossRef]

- Abd ZH, Muter SA, Saeed RAM, Ammar O. Effects of covid-19 vaccination on different semen parameters. Basic Clin Androl (2022) 32(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Gat I, Kedem A, Dviri M, Umanski A, Levi M, Hourvitz A, et al. Covid-19 vaccination BNT162b2 temporarily impairs semen concentration and total motile count among semen donors. Andrology (2022) 10:1016–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H, Wang X, Zhang F, Zhu Y, Du MR, Tao ZW, et al. Evaluation of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine on semen parameters in reproductive-age males: a retrospective cohort study. Asian J Androl (2022) 24:441–4. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Li X, Li Z, Zhu Y, Wei Z, He J, Cheng H, Yang A, Chen F. Effects of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccination on male fertility: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Medical Virology. 2023 Jan;95(1):e28329.

- Reschini M, Pagliardini L, Boeri L, Piazzini F, Bandini V, Fornelli G, et al. COVID-19 vaccination does not affect reproductive health parameters in men. Front Public Health (2022) 10:839967. [CrossRef]

- Safrai M, Herzberg S, Imbar T, Reubinoff B, Dior U, Ben-Meir A. The BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine does not impair sperm parameters. Reprod BioMed Online (2022) 44(4):685–8. [CrossRef]

- Xia W, Zhao J, Hu Y, Fang L, Wu S. Investigate the effect of COVID-19 inactivated vaccine on sperm parameters and embryo quality in vitro fertilization. Andrologia (2022) 54(6):e14483. [CrossRef]

- Chillon TS, Demircan K, Weiss G, Minich WB, Schenk M, Schomburg L. Detection of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 after vaccination in seminal plasma and their association to sperm parameters. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2023 May 1;130:161-5.

- Hulme KD, Gallo LA, Short KR. Influenza Virus and Glycemic Variability in Diabetes: A Killer Combination?. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:861. Published 2017 May 22. [CrossRef]

- Akamine CM, El Sahly HM. Messenger ribonucleic acid vaccines for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 - a review. Transl Res. 2022 Apr;242:1-19. Epub 2021 Dec 23. PMID: 34954088; PMCID: PMC8695521. [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R., Sardu, C., D’Onofrio, N. et al. Glycaemic control is associated with SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated patients with type 2 diabetes. Nat Commun 13, 2318 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Cieślewicz A, Dudek M, Krela-Kaźmierczak I, Jabłecka A, Lesiak M, Korzeniowska K. Pancreatic Injury after COVID-19 Vaccine-A Case Report. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(6):576. Published 2021 Jun 1. [CrossRef]

- Boskabadi SJ, Ala S, Heydari F, Ebrahimi M, Jamnani AN. Acute pancreatitis following COVID-19 vaccine: A case report and brief literature review. Heliyon. 2023 Jan;9(1):e12914. Epub 2023 Jan 14. PMID: 36685416; PMCID: PMC9840226. [CrossRef]

- Cacdac R, Jamali A, Jamali R, Nemovi K, Vosoughi K, Bayraktutar Z. Acute pancreatitis as an adverse effect of COVID-19 vaccination. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221131169. Published 2022 Oct 24. [CrossRef]

- Guo M, Liu X, Chen X, Li Q. Insights into new-onset autoimmune diseases after COVID-19 vaccination. Autoimmun Rev. 2023;22(7):103340. [CrossRef]

- Aida K, Nishida Y, Tanaka S, et al. RIG-I- and MDA5-initiated innate immunity linked with adaptive immunity accelerates beta-cell death in fulminant type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60(3):884-889. [CrossRef]

- Yin X, Riva L, Pu Y, et al. MDA5 Governs the Innate Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 in Lung Epithelial Cells. Cell Rep. 2021;34(2):108628. [CrossRef]

- He YF, Ouyang J, Hu XD, Wu N, Jiang ZG, Bian N, Wang J. Correlation between COVID-19 vaccination and diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. World J Diabetes 2023; 14(6): 892-918.

- Bleve, E., Venditti, V., Lenzi, A. et al. COVID-19 vaccine and autoimmune diabetes in adults: report of two cases. J Endocrinol Invest 45, 1269–1270 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Moon H, Suh S, Park MK. Adult-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Development Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(2):e12. Published 2023 Jan 9. [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan Bİ, Ünlütürk U, Cesur M. Type 1 diabetes mellitus following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Endocrine. 2022;78(1):42-46. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai K, Narita D, Saito N, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus following COVID-19 RNA-based vaccine. J Diabetes Investig. 2022;13(7):1290-1292. [CrossRef]

- Yano M, Morioka T, Natsuki Y, Sasaki K, Kakutani Y, Ochi A, Yamazaki Y, Shoji T, Emoto M. New-onset Type 1 Diabetes after COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. Intern Med 2022; 61: 1197-1200 [PMID: 35135929]. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki K, Morioka T, Okada N, Natsuki Y, Kakutani Y, Ochi A, Yamazaki Y, Shoji T, Ohmura T, Emoto M. New-onset fulminant type 1 diabetes after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: A case report. J Diabetes Investig 2022; 13: 1286-1289 [PMID: 35167186]. [CrossRef]

- Kshetree B, Lee J, Acharya S. COVID-19 Vaccine-Induced Rapid Progression of Prediabetes to Ketosis-Prone Diabetes Mellitus in an Elderly Male. Cureus 2022; 14: e28830 [PMID: 36225440]. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki H, Itoh A, Watanabe Y, et al. Newly developed type 1 diabetes after coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination: A case report. J Diabetes Investig. 2022;13(6):1105-1108. [CrossRef]

- Sato T, Kodama S, Kaneko K, Imai J, Katagiri H. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Nivolumab after Second SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 2022; 28: 1518-1520 [PMID: 35468049]. [CrossRef]

- Ohuchi K, Amagai R, Tamabuchi E, Kambayashi Y, Fujimura T. Fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus triggered by coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in an advanced melanoma patient given adjuvant nivolumab therapy. J Dermatol 2022; 49: e167-e168 [PMID: 35014070]. [CrossRef]

- Patrizio A, Ferrari SM, Antonelli A, Fallahi P. A case of Graves' disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Autoimmun. 2021;125:102738. [CrossRef]

- Graus, F., Saiz, A. & Dalmau, J. GAD antibodies in neurological disorders — insights and challenges. Nat Rev Neurol 16, 353–365 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Fiorina P. GABAergic system in β-cells: from autoimmunity target to regeneration tool. Diabetes. 2013 Nov;62(11):3674-6. PMID: 24158998; PMCID: PMC3806604. [CrossRef]

- Tohid Hassaan, Anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody positive neurological syndromes Neurosciences 2016; Vol. 21 (3): 215-222. [CrossRef]

- Tridgell DM, Spiekerman C, Wang RS, Greenbaum CJ. Interaction of onset and duration of diabetes on the percent of GAD and IA-2 antibody-positive subjects in the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium database. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):988-993. [CrossRef]

- Ramos EL, Dayan CM, Chatenoud L, et al. Teplizumab and β-Cell Function in Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(23):2151-2161. [CrossRef]

- Doering TA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Paley MA, Ziegler CG, Wherry EJ. Network analysis reveals centrally connected genes and pathways involved in CD8+ T cell exhaustion versus memory. Immunity. 2012; 37:1130–1144. [PubMed: 23159438].

- McKinney EF, Lee JC, Jayne DRW, Lyons PA, Smith KGC. T-cell exhaustion, co-stimulation and clinical outcome in autoimmunity and infection. Nature. 2015; 523:612–616. [PubMed: 26123020].

- Long SA, Thorpe J, DeBerg HA, et al. Partial exhaustion of CD8 T cells and clinical response to teplizumab in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Sci Immunol. 2016;1(5):eaai7793. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Gebo KA, Abraham AG, et al. Dynamics of inflammatory responses after SARS-CoV-2 infection by vaccination status in the USA: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4(9):e692-e703. [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski SR, Søgaard OS, Tolstrup M, et al. Inflammation and Platelet Activation After COVID-19 Vaccines - Possible Mechanisms Behind Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:779453. Published 2021 Nov 23. [CrossRef]

- Deniz Ç, Altunan B, Ünal A. Anti-GAD Encephalitis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Report. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2023;60(3):283-287. Published 2023 Aug 3. [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi M, Toyoda M, Zhang J, et al. Nivolumab-induced fulminant type 1 diabetes with precipitous fall in C-peptide level. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(3):748-749. [CrossRef]

- Akturk HK, Kahramangil D, Sarwal A, Hoffecker L, Murad MH, Michels AW. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced Type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2019;36(9):1075-1081. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Morgan A, Shah S, Ebeling PR. Rapid-onset diabetic ketoacidosis secondary to nivolumab therapy. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2018;2018:18-0021. Published 2018 Apr 27. [CrossRef]

- Lo Preiato V, Salvagni S, Ricci C, Ardizzoni A, Pagotto U, Pelusi C. Diabetes mellitus induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: type 1 diabetes variant or new clinical entity? Review of the literature. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(2):337-349. [CrossRef]

- Gauci, ML., Laly, P., Vidal-Trecan, T. et al. Autoimmune diabetes induced by PD-1 inhibitor—retrospective analysis and pathogenesis: a case report and literature review. Cancer Immunol Immunother 66, 1399–1410 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Stamatouli AM, Quandt Z, Perdigoto AL, Clark PL, Kluger H,Weiss SA, et al. Collateral Damage: Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Induced With Checkpoint Inhibitors. Diabetes (2018) 67(8):1471–80. [CrossRef]

- Godwin JL, Jaggi S, Sirisena I, Sharda P, Rao AD, Mehra R, et al. Nivolumab-Induced Autoimmune Diabetes Mellitus Presenting as Diabetic Ketoacidosis in a Patient With Metastatic Lung Cancer. J Immunother Cancer (2017) 5(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Lowe JR, Perry DJ, Salama AKS, Mathews CE, Moss LG, Hanks BA. Genetic Risk Analysis of a Patient With Fulminant Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Secondary to Combination Ipilimumab and Nivolumab Immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer (2016) 4(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wu L, Tsang VHM, Sasson SC, et al. Unravelling Checkpoint Inhibitor Associated Autoimmune Diabetes: From Bench to Bedside. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:764138. Published 2021 Nov 5. [CrossRef]

- Cohen Tervaert JW, Martinez-Lavin M, Jara LJ, et al. Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) in 2023. Autoimmun Rev. 2023;22(5):103287. [CrossRef]

- Watad A, Bragazzi NL, McGonagle D, et al. Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) demonstrates distinct autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease associations according to the adjuvant subtype: Insights from an analysis of 500 cases. Clin Immunol. 2019;203:1-8. [CrossRef]

- 213. Vera-Lastra O, Medina G, Cruz-Dominguez Mdel P, Jara LJ, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (Shoenfeld's syndrome): clinical and immunological spectrum. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9(4):361-373. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Xu Z, Wang P, Li XM, Shuai ZW, Ye DQ, et al. New-onset autoimmune phenomena post-COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology 2022;165(4):386–401. [Epub 2022 Jan 7]. [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi NL, Hejly A, Watad A, Adawi M, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y. ASIA syndrome and endocrine autoimmune disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(1):101412. [CrossRef]

- Di Fusco M, Lin J, Vaghela S, Lingohr-Smith M, Nguyen JL, Scassellati Sforzolini T, Judy J, Cane A, Moran MM. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness among immunocompromised populations: a targeted literature review of real-world studies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022 Apr;21(4):435-451. Epub 2022 Feb 3. PMID: 35112973; PMCID: PMC8862165. [CrossRef]

- Mirza SA, Sheikh AAE, Barbera M, et al. COVID-19 and the Endocrine System: A Review of the Current Information and Misinformation. Infect Dis Rep. 2022;14(2):184-197. Published 2022 Mar 11. [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis KK, Giannos P, Stathi D, Kechagias KS. Graves' disease following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review of the reported cases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:938001.

- Zaçe D, La Gatta E, Petrella L, Di Pietro ML. The impact of COVID-19 vaccines on fertility-A systematic review and metanalysis. Vaccine. 2022 Sep 12.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).