1. Introduction

Shingles, known more formally as Herpes zoster, is a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the etiological agent responsible for the primary infection of chicken-pox. The lifetime risk of shingles is estimated to range between 10 to 20 percent. Shingles commonly presents as a painful, blistering rash that typically appears on one side of the body, often in a band-like pattern. This condition results from the reactivation of the var-icella-zoster virus, which lies dormant in nerve tissue after an initial chickenpox infection. Patients frequently report the onset of pain, itching, or tingling in the area before the rash becomes visible. As the rash develops, clusters of clear blisters form, filling with fluid and eventually crushing over. In addition to the rash, shingles can lead to other systemic symptoms, including fever, headache, and fatigue. Complications such as postherpetic neuralgia, a condition characterized by persistent pain in the area of the rash long after it has healed, can significantly impact the quality of life of affected individuals [

1,

2]. Shin-gles morbidity statistics show that approximately 1% of patients diagnosed with herpes zoster necessitated hospitalization [

3,

4]. Mortality associated with Shingles is exceedingly rare, reported at 0 to 0.47 per 100,000 individuals annually [

3]. The financial burden as-sociated with managing and treating herpes zoster in the United States is estimated to amount to

$1.1 billion annually [

5].

To reduce morbidity and mortality associated with Shingles, the Advisory Commit-tee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) advocates for the immunization of immunocompe-tent adults aged 50 years and older with the HZ/su vaccine, commercially known as Shin-grix [

6]. The Shingrix vaccine has demonstrated robust efficacy in the prevention of herpes zoster (shingles), especially among older adults who are at higher risk for the disease [

7]. Clinical trials have shown that Shingrix is over 90% effective at preventing shingles and its complications, including the severe and prolonged pain condition known as posther-petic neuralgia [

8]. This high level of efficacy is maintained for at least four years after vaccination, indicating a robust and durable immune response. The consistent perfor-mance of Shingrix in reducing the incidence and severity of herpes zoster underscores its critical role in public health vaccination strategies [

7].

The Shingrix vaccine has a proven favorable safety profile characterized by its high efficacy and manageable side effects. Clinical trials and ongoing surveillance report mild to moderate adverse reactions, predominantly localized pain, redness, swelling at the vac-cination site, and systemic symptoms, including myalgia, fatigue, and headache [

9]. Ad-verse reactions are commonly associated with a strong immunogenicity response, signi-fying the vaccine’s effective immunogenic activity; moreover, the reactions usually re-solve spontaneously within a few days [

9]. The consistency of these findings underscores the vaccine’s reliability and the balanced nature of its side effects, reinforcing its im-portance in preventive health measures against herpes zoster [

9].

Known but rare, more serious adverse events have been documented, such as Guil-lain-Barré Syndrome and other neurological conditions. Reports also show uveitis and sarcoidosis following vaccination [

10]. In eight clinical trials involving over 10,000 partic-ipants, 17% of those who received Shingrix experienced grade 3 reactions, severe enough to prevent normal activities [

9]. These serious adverse events have extremely low inci-dence, and the benefits of vaccination with Shingrix significantly outweigh the risks for most individuals. Ongoing monitoring continues to support the strong safety profile of the Shingrix vaccine, reinforcing its role as a critical intervention in preventing herpes zoster and its complications in eligible populations; however, some patients report long-term, ongoing, serious adverse events. Here, we detail some serious adverse events using a survey of patients reporting serious adverse events after Shingrix vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample Selection

This survey study on adverse events following immunization (AEFIs) with the Shingrix vaccine was conducted online using a retrospective and cross-sectional ap-proach. We developed the survey questionnaire after thoroughly examining herpes zos-ter data and surveillance information from the Centers for Disease Control and Preven-tion (CDC). An extensive literature review on the side effects of the Shingrix vaccine and group discussions were undertaken to refine the questionnaire. Ethical clearance was secured from the human ethical review committee of Rocky Vista University to execute this study (approval number: #2022-071). The finalized online questionnaire was dissem-inated through an active Facebook group of people who developed severe adverse events after the Shingrix vaccination.

2.2. Questionnaire on Adverse Events following Shingrix Immunization

The survey explored the adverse effects experienced by individuals following their Shingrix vaccination. Organized into multiple segments, the questionnaire covered vac-cination details, participants’ health conditions before and after the vaccine, adverse re-actions, and how participants managed any ensuing symptoms. The opening segment of the survey provided a brief introduction and requested participant consent—a prerequi-site for participation. The following section gathered basic demographic information, such as age, gender, place of residence, and level of education. Details specific to the vaccination process, like the vaccine’s brand, the manufacturing company, the dates of administration, and the doses received, were the focus of the next segment. A section explicitly tailored for female respondents addressed questions about pregnancy and breastfeeding. Subsequent inquiries aimed to compile a comprehensive health profile of the participants before receiving the vaccine, asking about their COVID-19 status, any preventive actions taken, allergies, chronic illnesses, treatments received, and their vac-cination history, primarily seeking ’yes’ or ’no’ answers. The sixth segment, outlined in a supplementary document titled "After Effects Following Vaccination," asked partici-pants about prior COVID-19 infections before receiving their first vaccine dose and any physical discomfort post-vaccination, requiring straightforward ’yes’ or ’no’ responses. For participants indicating they experienced discomfort, the final segment probed deeper into the specifics of their symptoms post-vaccination, including the types of symptoms, their duration, and how they were managed.

2.3. Study Period

The research was conducted from March 12, 2022, to March 4, 2024, spanning ap-proximately 105 weeks (about two years). This period was devoted to collecting re-sponses from individuals vaccinated against shingles. While the survey attracted 170 participants who had received one or both doses of the shingles vaccine, only 77 partici-pants fully completed the survey, providing comprehensive data for analysis. The 77 surveys completed were used in the analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from the questionnaire included nominal and ordinal types. Both cumulative and mean data were summarized for the analysis, with results ex-pressed as percentages (%).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Analysis

Our analysis focused on 77 respondents who completed the survey, shedding light on the administrative practices surrounding the Shingrix vaccine. The data reveals in-sightful patterns in the vaccination process, including administration locations, concur-rent vaccine administration, methods and sites of vaccine delivery, and specific conditions at the time of vaccination.

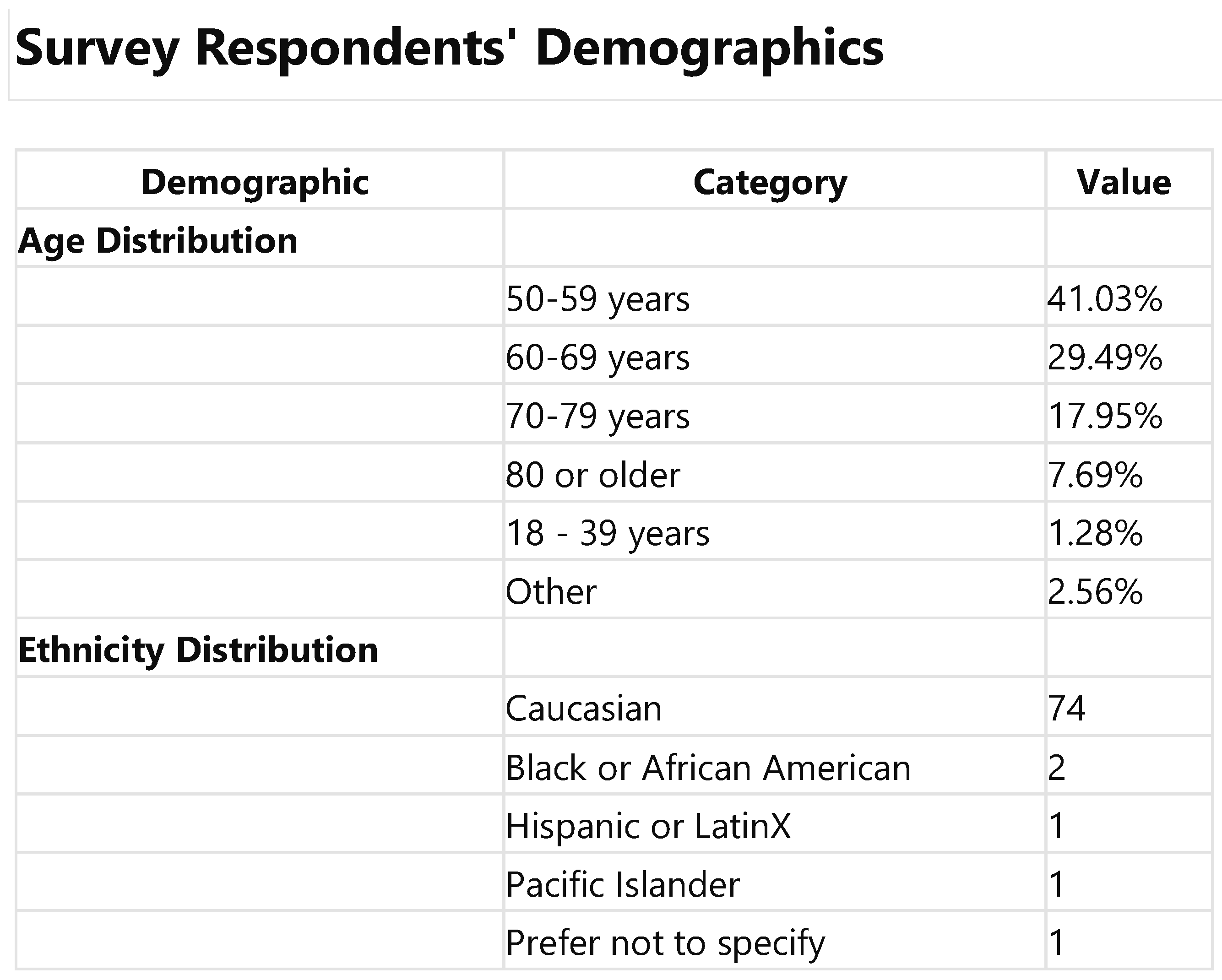

Upon reviewing the data for the 77 participants who fully completed the survey, it was observed that the demographic profile primarily encompasses middle-aged to senior ndividuals, with the most significant age groups being 50-59 years (41.0%) and 60-69 years (29.5%). As expected, given ACIP guidelines, this distribution underscores a pre-dominant representation of mature adults. Regarding ethnicity, the recalculated data mir-rored the initial analysis, showing a majority of respondents identifying as Caucasian (74 mentions), alongside a limited representation of other ethnicities, including Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx, Pacific Islander, American Indian, and other.

3.2. Health History Prior to the Shingles Vaccination

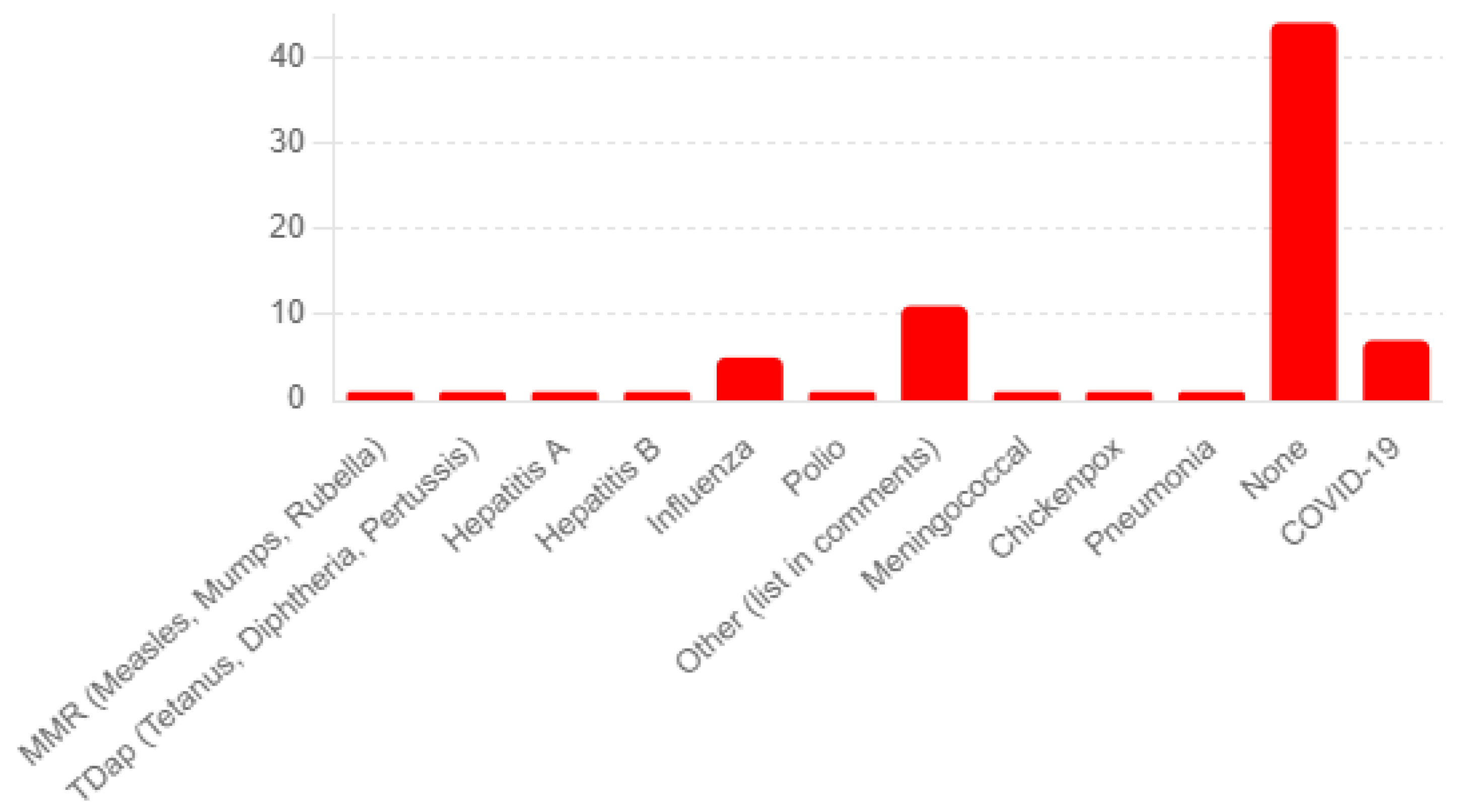

The survey’s patient medical history questions yield insightful data on the partici-pants’ health backgrounds. For Q20a, regarding the history of chickenpox or shingles, 68 participants reported no history of shingles, and eight reported having such a history. Known allergies were limited (Q26). Survey participants noted that adverse events to previous vaccines were limited, with 44 reporting none and 11 reporting minor, unspeci-fied reactions (see

Figure 1).

Most respondents (76.6%) reported no specific conditions at the time of vaccine ad-ministration, indicating a straightforward vaccination process for most individuals. Nev-ertheless, a small subset reported either severe allergic reactions to previous vaccines, other diseases or infections, or were undergoing treatment for a shingles outbreak. Alt-hough less common, these conditions highlight the importance of assessing patient his-tory and current health status in vaccine administration.

3.3. Shingrix Vaccine Administration

The majority of Shingrix vaccine doses were administered in pharmacies or stores (66.2%) and doctors’ offices (26.0%), with smaller distributions in public health clinics (2.6%), workplace clinics (1.3%), and other locations (2.6%). Most participants (75.3%) did not receive any other vaccines concurrently with Shingrix, while 10.4% did, indicating that co-administration is relatively uncommon. The preferred method of administration was injection (94.8%), with most vaccines given in the arm (94.8%). Intranasal delivery was rare (1.3%), as were other unspecified methods (1.3%).

3.4. Shingrix Vaccination Side-Effects and Their Severity

The survey reported various symptoms, with some participants experiencing multi-ple symptoms. Notable mentions include pain/tenderness (observed in several combina-tions with other symptoms), muscle pain/myalgia, fatigue, and headaches (Q61) (See

Figure 2). Many responses were categorized under "Other," indicating a diversity of adverse effects not explicitly listed in the survey options. The severity ratings revealed that many symptoms were rated as severe, preventing daily activity (Grade 3) across multiple symp-toms, including pain/tenderness, muscle pain/myalgia, fatigue, and headaches. A few "Po-tentially Life-Threatening" reactions (Grade 4) were noted. Overall, these results are con-sistent with clinical trial data.

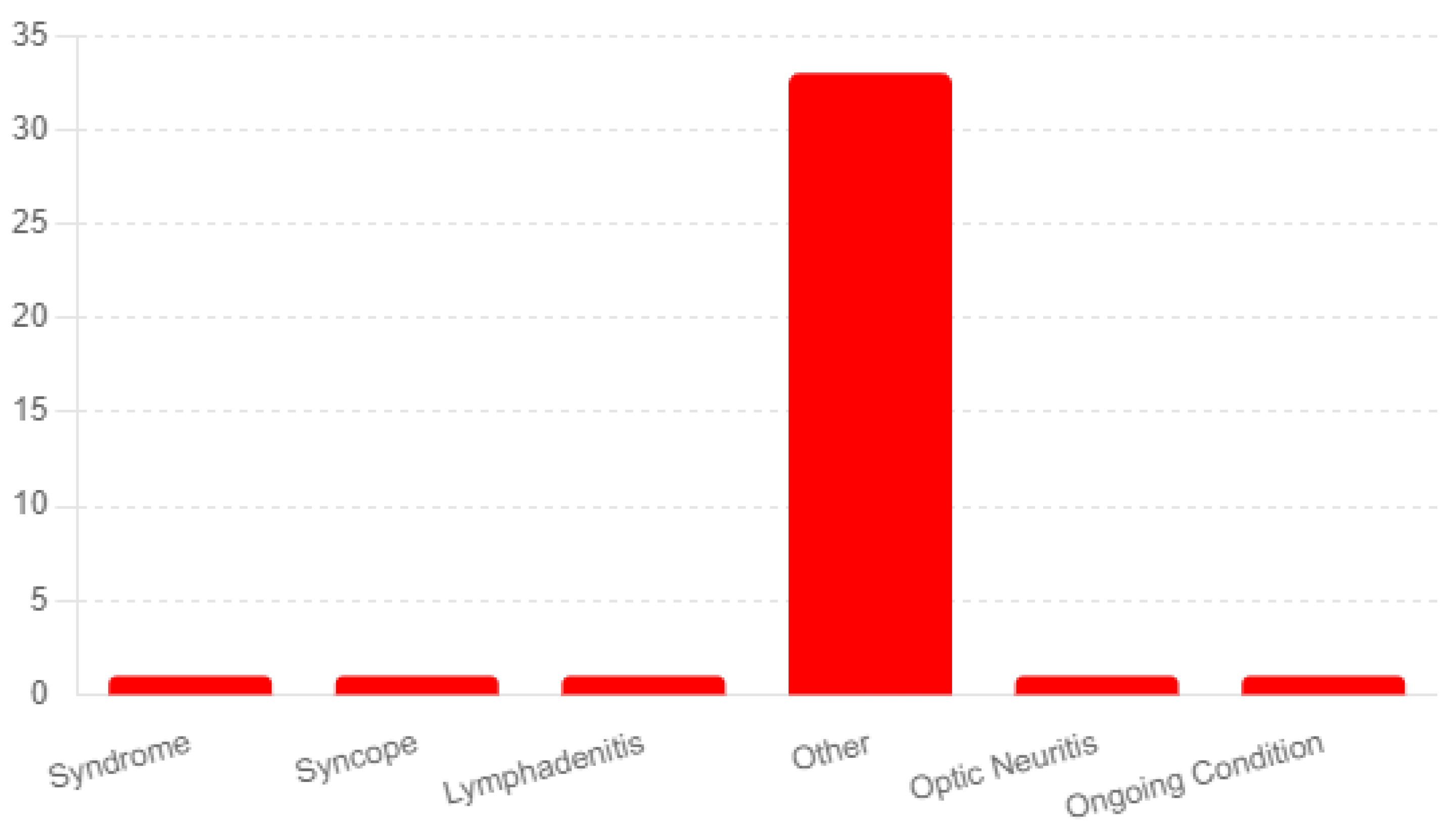

The analysis reported diagnoses of ongoing conditions following the administration of the Shingrix vaccine. The most frequently mentioned category was "Other," with 33 respondents indicating conditions not explicitly listed in the survey options. Here is a list-ing of the most prominent in the survey-

Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A concerning finding was three participants’ reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Guillain-Barré syndrome is a rare but known serious adverse event.

Neuropathy: Another long-term side effect of the vaccine reported by nine partici-pants was neuropathy. The duration of the side effects varied from months to years fol-lowing the vaccine.

Ongoing Angioedema, Rash, and Urticaria: Two respondents reported experiencing ongoing angioedema, rash, and urticaria, which involve swelling, redness, and hives, re-spectively. These skin-related reactions indicate potential allergic responses or sensitivi-ties triggered by the vaccine.

3.5. Long-term Shingrix Vaccination Side-Effects and Their Severity

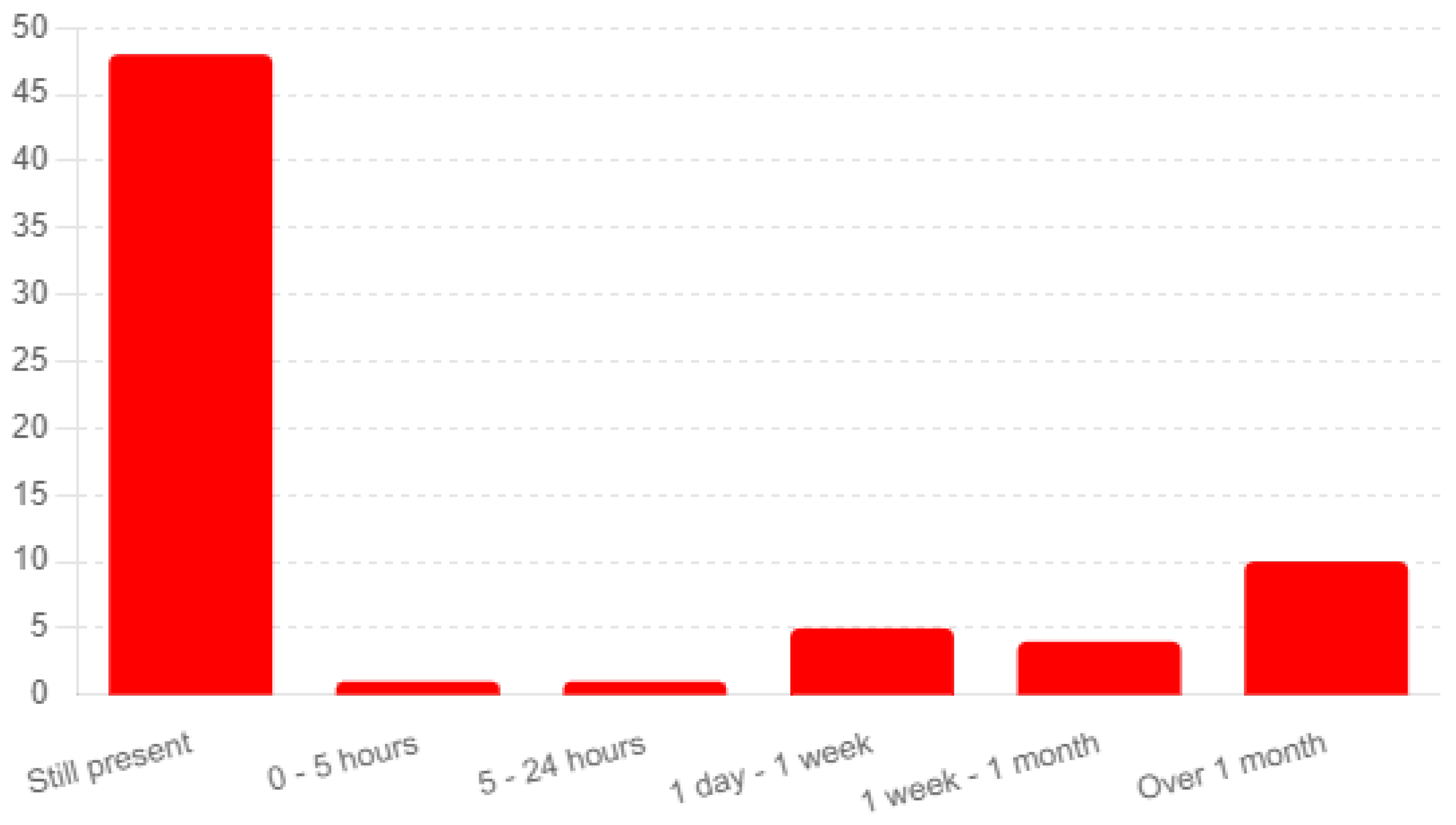

The analysis of responses from 77 completed surveys provides insights into the du-ration of symptoms experienced post-vaccination and their progression over time (Q66). A significant number of respondents (48) reported that their symptoms were still present at the time of the survey, indicating ongoing adverse effects (see

Figure 3). An additional 10 participants noted symptoms lasting over one month, underscoring the potential for prolonged discomfort following vaccination.

The survey participants were evenly split regarding the progression of their symp-toms, with 37 respondents indicating their symptoms had worsened over time and an-other 37 reporting no worsening (Q67). This division highlights varied experiences among vaccine recipients regarding the trajectory of their post-vaccination symptoms.

3.6. Treatment Effectiveness for Shingrix Vaccination Side-Effects

In analyzing the responses from 77 completed surveys regarding the Shingrix vac-cine, we focused on treatments prescribed for adverse events, participant adherence to these treatments, and their perceived effectiveness. A wide range of treatments was pre-scribed to respondents, as indicated by 68 unique entries, with four respondents explicitly stating "None" and 2 stating "N/A." Prescribed treatments varied significantly, from med-ication like Valacyclovir hydrochloride for nerve pain to non-pharmacological approaches like ultrasound of the arm and osteopathic treatments. This diversity underscores the per-sonalized nature of healthcare responses to vaccine-related adverse events. The majority of participants (51) reported adhering to the prescribed treatments, indicating a high level of compliance. However, 12 respondents reported not taking the prescribed treatment, and 2 took most of the prescription, reflecting varied adherence levels among partici-pants.

4. Discussion

In this survey study, we sought to assess the safety profile of the Shingrix vaccine, focusing on persistent adverse events following their vaccination. The findings under-score the importance of monitoring and researching the long-term effects of the Shingrix vaccine. The range of ongoing conditions reported, from neurological disorders like Guillain-Barré syndrome to dermatological reactions, calls for a comprehensive ap-proach to post-vaccination care and highlights the need for continued vigilance in vac-cine safety monitoring.

These findings elucidate the range of experiences related to the duration and pro-gression of symptoms post-Shingrix vaccination. The data reveals that a notable propor-tion of respondents faced symptoms that persisted or even worsened over time, indicat-ing the need for careful monitoring and potentially extended support for individuals experiencing adverse effects. The diversity in symptom duration and progression underscores the importance of personalized approaches to post-vaccination care and the need for further research into managing and mitigating these adverse events. The survey also underscores the poor treatment options for adverse events associated with Shingrix vaccination.

The analysis reveals the complex landscape of healthcare responses to adverse events following the Shingrix vaccination. While a wide array of treatments was pre-scribed, reflecting the varying needs and conditions of the respondents, adherence levels varied. The absence of direct data on treatment effectiveness points to an area requiring further inquiry to fully understand the impact of these healthcare interventions on vac-cine recipients’ recovery and well-being

Despite a thorough analysis to ensure accurate interpretations of the Shingrix vac-cine’s safety profile, our study faced several limitations. The online nature of our survey inherently limited the scope and depth of data collection, as we could not engage in di-rect interactions that might have offered richer insights. This methodological choice meant that our findings were primarily based on self-reported information, without the possibility of external validation by healthcare professionals.

Additionally, the structure of our study did not allow for long-term follow-up with participants regarding the per-sistence or evolution of side effects experienced post-vaccination. Such longitudinal data are essential for a more nuanced understanding of the vaccine’s safety profile over time, especially considering the potential for delayed adverse events.

This survey study provides valuable insights into the safety profile of the Shingrix vaccine, mainly through the lens of long-term, serious adverse events. The findings highlight a prevalence of mild to moderate adverse events, such as pain, muscle aches, fatigue, and headaches, consistent with existing literature on vaccine side effects. While most symptoms resolved quickly, the study also identified severe and persistent condi-tions in a small subset of participants, including Guillain-Barré syndrome, underscoring the necessity for ongoing post-vaccination monitoring. These results emphasize the im-portance of further research to understand the vaccine’s long-term safety and efficacy thoroughly. By offering a detailed overview of the reported side effects and their man-agement, this study aims to support informed decision-making about shingles vaccina-tion and alleviate public concerns, ultimately contributing to improved public health outcomes. This entails ongoing longitudinal studies and pharmacovigilance initiatives, essential for identifying and monitoring any potential long-term adverse effects associ-ated with Shingrix and other shingles vaccines. Such comprehensive evaluations will ensure that vaccination strategies are safe and effective in combating the risk of shingles on a global scale.

Author Contributions

BDB conceived the original idea., A.K. collected the survey data by using electronic and social media. M.J.W., J.M., H.E. constructed the questionnaire in Qualtrics. A.K., A.V., S.H., J.S. prepared the initial manuscript, did the statistical analysis, and arranged the reference sec-tion. A.K., M.J.W. critically reviewed the overall activities. BDB supervised the whole activity. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

institutionalreviewhe study was conducted in accordance with the Declara-tion of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of ROCKY VISTA UNIVERSITY (protocol code 2022-071 and approval date of 19 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study to conduct the research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all study participants for their thoughtful responses and patience throughout the survey. We also appreciate the authors of the articles and research we ref-erenced.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- CDC. Shingles Symptoms and Complications. Shingles (Herpes Zoster). Published May 14, 2024. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/signs-symptoms/index.html.

- Viruses | Free Full-Text | Herpes zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/14/2/192.

- Johnson RW, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Bijl M, et al. Herpes zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: a multidisciplinary perspective. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2015;3(4):109-120. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Chiappe S, Sarazin M, Turbelin C, et al. Herpes zoster: Burden of disease in France. Vaccine. 2010;28(50):7933-7938. [CrossRef]

- Yawn BP, Itzler RF, Wollan PC, Pellissier JM, Sy LS, Saddier P. Health Care Utilization and Cost Burden of Herpes Zoster in a Community Population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(9):787-794.

- Anderson, TC. Use of Recombinant Zoster Vaccine in Immunocompromised Adults Aged ⪰19 Years: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71. [CrossRef]

- Xia Y, Zhang X, Zhang L, Fu C. Efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of herpes zoster vaccine in the immunocompetent and im-munocompromised subjects: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:978203. [CrossRef]

- Maltz F, Fidler B. Shingrix: A New Herpes Zoster Vaccine. P T. 2019;44(7):406-433.

- Safety Information for Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Vaccines | Vaccine Safety | CDC. Published December 22, 2022. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/shingles-herpes-vaccine.html.

- Heydari-Kamjani M, Vante I, Uppal P, Demory Beckler M, Kesselman MM. Uveitis Sarcoidosis Presumably Initiated After Administration of Shingrix Vaccine. Cureus. 11(6):e4920. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).