1. Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common in men over 50 years of age. They pose a significant burden of disease and impact on quality of life (QoL) (1, 2). In males, LUTS are commonly caused by benign prostatic obstruction (BPO). BPO is a result of unregulated proliferation of prostatic tissue - this histological diagnosis is known as benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). The continue proliferation leads to benign prostate enlargement (BPE), ultimately the enlargement can cause obstruction at the bladder outlet (2).

Transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) has been the gold standard for the surgical management of BPH. However, there has been a steady decline in this procedure globally, due to the introduction of laser prostatectomy for resection in larger prostates (3, 4). Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) is an example of a laser prostatectomy, in 2017 it accounted for 5.9% of all BPH procedures in Australia (5) and according to the recent medicare statistics report it accounts for roughly 9.2% of all BPH procedures in 2022 (see

table S1) (6). Like other laser prostatectomy procedures, it is considered to be less invasive compared to TURP, since 2009, Australia has been trending towards minimally invasive options when treating BPH (7).

Current EUA and AUA guidelines consider HoLEP as a size independent treatment option for BPH, and it can be offered as an alternative to TURP for patients with moderate to severe LUTS; often HoLEP is offered for larger prostates (>80ml) (2). HoLEP is comparable to TURP in terms of mid to long term efficacy (especially for small to mid-sized prostate), it also shares similar peri-operative outcomes and complication rates at 2 and 3 year follows up (2, 8, 9). Furthermore, HoLEP is associated with reduced bleeding risk, shorter hospital stays, reduced reoperation rate, and can be offered to patients who remains on anti-platelet medications (5, 7, 9).

Access to online health information has become a vital part in a patient’s decision making in their health management. Evidence suggests there is an increasing number of patients using online information as a tool for further education. Patients who access online health information are generally found to be from a higher socioeconomical background. While the amount of usage or access to online information is inversely related to their age (10). There have been several other studies that have assessed quality of online health information related to various urological topics such as andrology, urological cancers, and robotic surgery (11-13). The aim of this study is to assess the quality and readability of online information related to the HoLEP procedure in men with BPH. There are no previous studies that looked at the quality of online information regarding HoLEP specifically. However, the study from Chen et al., 2014 was able to utilize the heath on the net (HON) tool to evaluate online health information on various BPH procedures (14). Unfortunately, the HON tool service has been discontinued, hence, it has not been selected as a quality assessment tool in this study.

2. Methods

Webpage selection:

A Google search was conducted for the term “Holmium laser surgery” and “enlarged prostate” on the 8th of July 2023. Google Chrome Version 114.0.5735.198 was used and to limit any results from being affected by tracking cookies, all previous cookie history was deleted. The first 150 webpage results that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria were assessed further. The inclusion criteria: (i) English webpages only, (ii) webpages included information on HoLEP. The exclusion criteria: (i) promoted advertisements, (ii) webpages that are paywall, and (iii) webpages that are presented as scientific literature such as journal articles or books. Each webpage was scored by two independent reviewers using quality and readability measures. If there was a discrepancy in score then a third reviewer would decide on the final score.

Quality measures:

To assess each webpage, three recognized quality assessment tools were used: (i) DISCERN (ii) QUEST, and (iii) the Journal of the American Medical association (JAMA) criteria. The DISCERN is a validated questionnaire to assess consumer health information without specialist knowledge, it focuses on areas such as reliability, currency, balance, source and quality of information. There are 16 questions and each are assessed against a 5-point Likert-type scale with a score range from 16-80 (15). The QUEST tool focuses on areas such as authorship, attribution, conflict of interest, currency, complementarity, and tone. The format includes six questions that are weighted and assessed against a Likert-type scales, with a score range from 0-28 (16). JAMA benchmark is used to assess whether health information is both authentic and reliable, its focuses on authorship, attribution, disclosure, and currency; with a score range from 0-4 (17).

Readability measures:

To assess the readability of each webpage, four validated measures were used: (i) Fleisch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKG), (ii) the Gunning-Fog Index (GFI), (iii) Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), and (iv) Flesch Reading ease score (FRE). The online readability score calculator Readable was used to calculate the four readability scores for each webpage, this was achieved by copying the body text from each page into the score text function of the online score calculator.

FKG helps identify the level of education needed to understand the text, the higher the score the higher the education needed (based on the USA grade level of education system). The FKG ranges from 0-18. FRE is similar to FKG, as they are derived from a similar formula; FRE ranges from 0-100. GFI closely resembles FKG, however, it focuses on complex word. The higher GFI score is, the greater the education level is need to understand the text; the score ranges from 0-20. SMOG index is a tool used to measure comprehension, its measure the number of years of education an average person needs to understand the text (18).

In summary, these scores are equivalent to the school grade level of comprehension. For general public, a text should aim for score equivalent to USA school grade level 8, e.g., FKG 8, FRE 70-80, GFI 8, and a SMOG below 10 (18, 19).

Statistical analysis:

JASP 0.17.3 (intel) statistical software was used. Descriptive data are reported as median and interquartile range. Kendall tau correlation was used to assess correlation between quality and readability measures. Non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare the effects of rank and sponsorship on quality assessment scores, and significant difference identified was then assessed with post hoc Games-Howell test. A linear regression model was conducted, using rank and sponsorship to predict quality assessment scores; confounds or covariates were excluded in step by step approach to identify for significant regression coefficients.

3. Results

In total 150 webpages were examined, 107 webpages were included as part of the data analysis, and in total 43 webpages were excluded. The most common targeted audience is patients (98%), and the remaining for health professionals. The most common sponsorship for these webpages originated from urologist’s private practice website – with a total of 40 (37%) webpages. Other sources included hospital – 28 (26%), health organization – 15 (14%), university – 10 (9%), non-profit organization – 9 (8%), media/news – 3 (2.8%), others – 2 (1.8%).

For the purpose of rank allocation, the first 50 pages were considered top ranked webpages, subsequently the following 50 pages, and last 50 page were considered middle and bottom ranked webpages respectively. Of the 107 webpages – 46 were top rank, 31 were middle rank, and 30 were bottom rank.

Descriptive Statistics

Top rank webpages scored higher in quality measures compared to bottom rank (

Table 1). DISCERN score: median subsection 1 score 22 IQR (19-25), median subsection 2 score 18 IQR (14-21), and median subsection 3 score 2 IQR (1-2). Readability score: The GFI median score 12.8 IQR (11.8-14), the FKG median score 10.7 IQR (9.6-11.7), the SMOG median score 12.8 IQR (12.1-13.7). The FRE median score 44.9 IQR (40.1-51.2).

Correlations

All three quality assessments correlated positively to each other, see

Table 2. DISCERN subsection scores also correlated positively to each other. All readability scores correlated to each other positively, except for FRE which was a negative correlation, see

Table 3.

Kruskal-Wallis (KW) Test

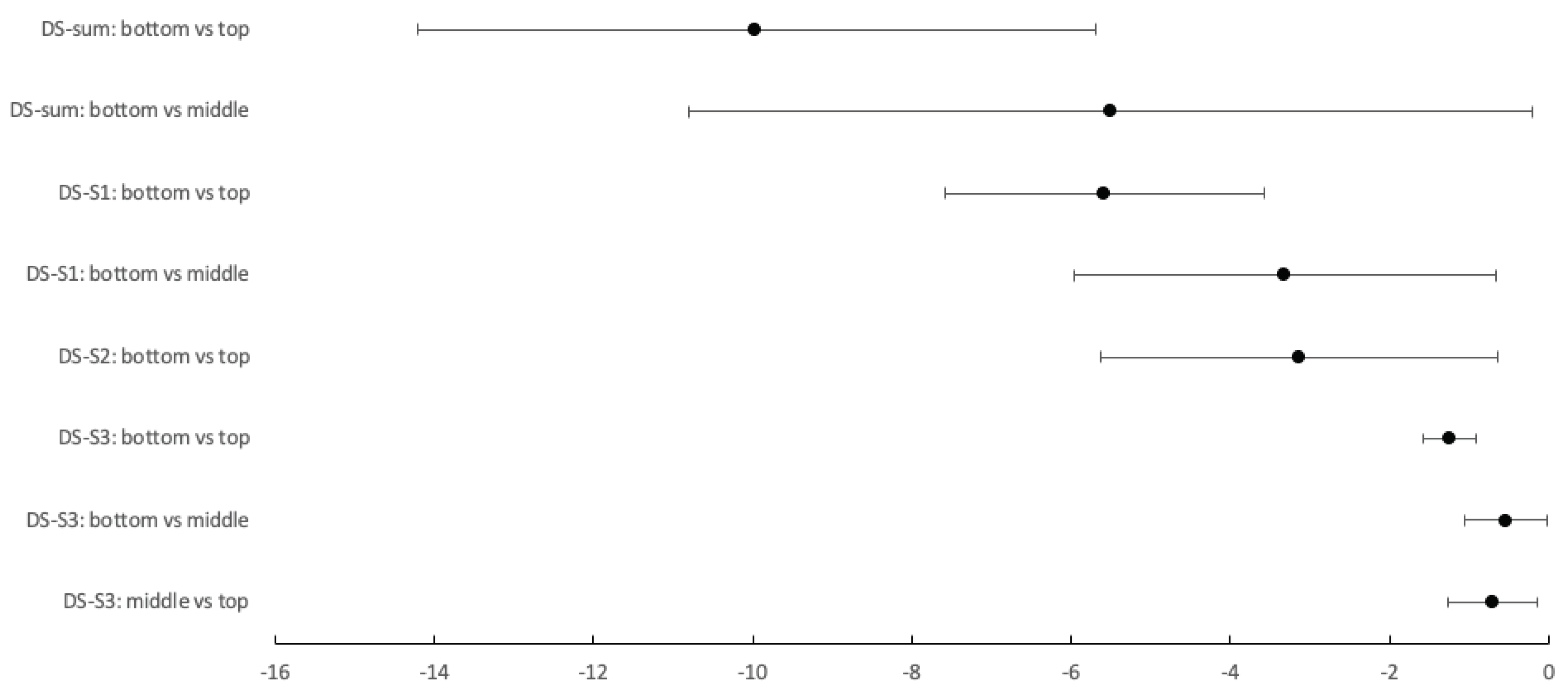

Only DISCERN showed significant difference on KW test, and this was also true for all subsection scores. Neither JAMA or QUEST showed any difference. With the post hoc Games-Howell (GH) test, the significant differences were between bottom and top rank webpages, mean difference= -9.968 (-14.2 to -5.7), p<0.00; between bottom and middle rank webpages, mean difference= -5.5 (-10.8 to -0.21) p<0.04. GH test also identified significant differences within the subsection scores, this can be seen in

Figure 1 and

S2 data.

With subgroup analysis on sponsorship, there are no significant differences identified with both DISCERN and QUEST scores. However, with JAMA there was a significant difference on KW df=6, p=0.005, post hoc GH test showed significant difference between health organization and urologist, mean difference= 1.042 (0.006-2.077), p=0.048.

Regression Analysis

Linear regression analysis identified that top and middle ranked webpages were significant predictors with DISCERN score. In the model the R2= 0.215, adjusted R2= 0.151, F = 3.349, p=0.002. Top rank search was a stronger predictor, β=10.515 (95% Cl 6.29-14.73) p<0.001, compared to middle rank, β= 5.823 (95% CI 1.29-10.35) p=0.012.

However, in comparison to DISCERN score, a higher ranked webpage was a weaker predictor for both QUEST and JAMA score based on regression model. In the QUEST regression model, R2= 0.176, adjusted R2=0.109, F=2.61, p=0.012, where β=2.481 (95% CI 0.4-4.56) p=0.02.

In the JAMA regression model, R2=0.231, adjusted R2=0.168, F=3.681 p<0.001, where β= 0.476 (95% CI 0.01-0.944) p=0.046. Notably, in this regression model we also identified sponsorship – urologist was a weak negative predictor for JAMA score, where β = -1.018 (95% CI -1.72 to -0.312), p=0.005. This latter finding was surprising.

With respective to readability, there were no significance identified on regression analysis.

4. Discussion

An increasing number of patients are now relying on online resources to access and gather healthcare information for their medical needs. However, the overall quality of online health information is known to be poor (20, 21). It has become more concerning with an increasing trend towards inaccurate or misinformation found online (22, 23). Yet, the internet remains a vital tool in patient’s healthcare decision making process (10). There is only a handful of studies that have investigated the quality and readability of online health information regarding the surgical management of BPH (14, 24). This is the first study to assess both the quality and readability of online health information of BPH management, with a specific focus on HoLEP. Consistent with the existing literature, the overall quality of online content related to urological treatment is considered poor (14, 24). None of the three quality measures used in our study scored >60% in total score.

In this study, the rank of the webpage is a significant positive predictor to the quality of health information. Linear regression analysis demonstrates higher rank webpages are more likely to score higher on all three quality assessment tools. Though on the KW test, ranking only had influence on DISCERN, both total and subsection scores. This is relevant to consumers, as literature suggest that patients search habits/strategies often spent majority of their time in the top ranked internet searches (25).

DISCERN is the suggested assessment tool in health literature, mainly because the questionnaire focuses on the reliability and details of the treatment (21, 26). In comparison, JAMA and QUEST tools, focuses on authorship and attribution (16, 17). This study highlights that many webpages lack scientific literature or reliable authorship to support their claims, however, literature has shown that consumers do not spend a great deal of time in identifying the attribution or reference of the webpage (25). This can be alarming because health information can be deemed of high quality, yet, the claims are not necessarily evidence-based practice.

The type of sponsorship has no influence on the quality of information. However, on linear regression analysis, sponsorship from a urologist was a weak negative predictor to JAMA score. This was a surprising finding, but this can be explained by the fact that the majority of the webpage’s lack good attribution & authorship, and urologist as a category for sponsorship is the most common group.

The overall readability is moderate-difficult, a minimum reading level of grade 11 is needed. This finding is consistent with previous studies, where online information is written at a level that is above the average reader (27–29). There is no specific reading level for Australia, as identified from our previous study (27). Though in USA this reading level will far exceed the recommended reading level expected from patient education material, where the recommended level is four to six (30).

There are limitations to this study that should be addressed and allows for future directions. Firstly, this study only focused on the quality of webpages, in English and based on written information available online. There were webpages that included videos and illustrations that were not assessed in this study. Secondly, although 150 webpages were included in this study, only 107 webpages (71%) were analyzed. A larger sample size would potentially provide a more thorough examination and an even distribution among top to bottom ranked webpages. Thirdly, the search term used was “enlarged prostate”, which was arbitrarily chosen as the selected layman search term. There is the possibility that using other relevant search terms such as “BPH” or “prostate hypertrophy” could have yielded a different set of webpages. Lastly, the google search could have been limited by geographic location, as the initial search was conducted under an Australian IP address. The google search may have favored or prioritized for webpages within the Australian server. For future studies, it would be worthwhile to conduct a study that used IP addresses of different geographic locations, to conduct searches with different search terms, and also to consider quality assessment of non-written information as well.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that online health information related to HoLEP and BPH is considered poor. Many webpages lack good evidence of authorship & attribution. Sponsorship does not appear to have an influence on the quality of information. The overall readability can be considered moderate-difficult, such that a minimum reading level of grade 11 is needed to comprehend online health information. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the higher ranking of a webpage is a positive predictor for quality assessment tools such as DISCERN/QUEST/JAMA. Investment in improving the quality and readability of online health information is paramount as there is an increasing reliance on access to online information in the patient’s informed decision-making process.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Acknowledgments

There are no acknowledgements.

References

- Martin, S.A.; Haren, M.T.; Marshall, V.R.; Lange, K.; Wittert, G.A. Prevalence and factors associated with uncomplicated storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms in community-dwelling Australian men. World J Urol. 2011, 29, 179–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, et al. EAU guidelines on the treatment and follow-up of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 2013;64(1):118-40. [CrossRef]

- Peyronnet, B.; Cornu, J.N.; Rouprêt, M.; Bruyere, F.; Misrai, V. Trends in the Use of the GreenLight Laser in the Surgical Management of Benign Prostatic Obstruction in France Over the Past 10 Years. Eur Urol. 2015, 67, 1193–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster HE, Dahm P, Kohler TS, Lerner LB, Parsons JK, Wilt TJ, et al. Surgical Management of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Attributed to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: AUA Guideline Amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202(3):592-8. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.M.; Bariol, S. National trends in surgical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in Australia. ANZ J Surg. 2019, 89, 345–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Services Australia AGDoH. Medicare Item reports, MBS item statistics reports 2023 [updated 23 August 2023; cited 2023 9 September]. Available from: http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp.

- Morton A, Williams M, Perera M, Teloken PE, Donato P, Ranasinghe S, et al. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia in the 21st century: temporal trends in Australian population-based data. BJU Int. 2020;126 Suppl 1:18-26. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Hak, A.J.; Choi, W.S.; Paick, S.H.; Kim, H.G.; Park, H. Comparison of Long-term Effect and Complications Between Holmium Laser Enucleation and Transurethral Resection of Prostate: Nations-Wide Health Insurance Study. Urology. 2021, 154, 300–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Feng, Z.; Peng, Y.; Liang, H. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Efficacy and Safety Following Holmium Laser Enucleation of Prostate and Transurethral Resection of Prostate for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Urology. 2019, 131, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Harrison, C.; Britt, H.; Henderson, J. Patient use of the internet for health information. Aust Fam Physician. 2014, 43, 875–7. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, J.; Wei, J.; Chiang, G.; Nzenza, T.C.; Bolton, D.; Lawrentschuk, N. Men’s health on the web: an analysis of current resources. World J Urol. 2019, 37, 1043–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, S.; Lawrentschuk, N. Consumerism and its impact on robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1874–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.T.S.; Abouassaly, R.; Lawrentschuk, N. Quality of Health Information on the Internet for Prostate Cancer. Adv Urol. 2018, 2018, 6705152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.C.; Manecksha, R.P.; Abouassaly, R.; Bolton, D.M.; Reich, O.; Lawrentschuk, N. A multilingual evaluation of current health information on the Internet for the treatments of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Int. 2014, 2, 161–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(2):105-11. [CrossRef]

- Robillard, J.M.; Jun, J.H.; Lai, J.A.; Feng, T.L. The QUEST for quality online health information: validation of a short quantitative tool. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberg, W.M.; Lundberg, G.D.; Musacchio, R.A. Assessing, Controlling, and Assuring the Quality of Medical Information on the Internet: Caveant Lector et Viewor—Let the Reader and Viewer Beware. JAMA. 1997, 277, 1244–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badarudeen, S.; Sabharwal, S. Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010, 468, 2572–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Readable, A.F. Measure the Readability of Text—Text Analysis Tools— Unique readability tools to improve your writing! New York.2020 [Available from: https://readable.com/.

- Eysenbach, G.; Powell, J.; Kuss, O.; Sa, E.R. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: a systematic review. Jama. 2002, 287, 2691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraz L, Morrow AS, Ponce OJ, Beuschel B, Farah MH, Katabi A, et al. Can Patients Trust Online Health Information? A Meta-narrative Systematic Review Addressing the Quality of Health Information on the Internet. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1884-91. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; McKee, M.; Torbica, A.; Stuckler, D. Systematic Literature Review on the Spread of Health-related Misinformation on Social Media. Soc Sci Med. 2019, 240, 112552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020, 41, 433–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhadana D, Nguyen DD, Raizenne B, Vangala SK, Sadri I, Chughtai B, et al. Assessing the Accuracy, Quality, and Readability of Information Related to the Surgical Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J Endourol. 2022;36(4):528-34. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach G, Köhler C. How do consumers search for and appraise health information on the world wide web? Qualitative study using focus groups, usability tests, and in-depth interviews. Bmj. 2002;324(7337):573-7. [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, S.; Charnock, D.; Gann, B. Helping patients access high quality health information. Bmj. 1999, 319, 764–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattenden, T.A.; Raleigh, R.A.; Pattenden, E.R.; Thangasamy, I.A. Quality and readability of online patient information on treatment for erectile dysfunction. BJUI Compass. 2021, 2, 412–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruthi, A.; Nielsen, M.E.; Raynor, M.C.; Woods, M.E.; Wallen, E.M.; Smith, A.B. Readability of American online patient education materials in urologic oncology: a need for simple communication. Urology. 2015, 85, 351–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, N.; Haglund, B.J. Readability of online health information: implications for health literacy. Inform Health Soc Care. 2011, 36, 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaco, M.; Svider, P.F.; Agarwal, N.; Eloy, J.A.; Jackson, I.M. Readability assessment of online urology patient education materials. J Urol. 2013, 189, 1048–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).